Motiva Business Law

5-Star Rating

(813) 214-8555

Tampa, Florida

(630) 517-5529

Oak Brook, Illinois

Assignment and assumption agreement

What is an assignment and assumption agreement?

An assignment and assumption agreement is a contract that allows one of the parties to transfer their contractual rights and duties to another party.

An assignment of contract is used after a previous agreement has been signed and one of the parties wants to pass on its obligations to a third party that wasn\’t originally part of the contract.

The parties involved in an assignment of contract are:

Uses of assignment agreements

Asset purchase transactions.

During mergers and acquisitions , the parties typically enter into additional agreements that are accessory to the purchase contract to evidence the transfer of assets. Among these ancillary documents is the assignment and assumption agreement, which may be required to make the Asset Purchase Agreement (APA) effective.

In the context of a business transaction, the assignment and assumption agreement is a shorter agreement than the APA. A buyer will use the assignment contract to evidence the ownership of the assigned assets, while the seller uses it to prove that it is the buyer who now has assumed all the rights and obligations related to the assigned asset.

In asset acquisitions, it is common to have several assignment agreements that are used to authenticate the property of different assets, such as patents, trademarks, or copyrights.

Opting out of a contract

If the party of a contract is no longer able to fulfill its obligations or wants to cede its rights to someone else, assignment agreements can come into place. Only if the terms of the original contract allow it, the assignor can transfer its property rights and obligations or debt to someone else.

An example could be a contractor who needs help to complete a job and assigns tasks and entitlements to a subcontractor.

Startup Assignment Agreements

Assignment contracts are typically used by newly formed businesses that rely on software, trademarks, or other sort of intellectual property. Since technology startups expect financing from outside investors, a technology attorney will usually recommend the use of assignment agreements as a means of ensuring third parties, such as shareholders, can profit from using their IP and make it easier to find funding for their businesses.

Conditions for an assignment contract to be valid

To be able to hand over the contractual obligations, the following criteria need to be met:

It’s essential to notice that, although assigning a contract will transfer the rights and duties to the receiving party, the assignor will not be released from any obligations that arose before the assignment. Before entering a contract assignment, ensure a contract review lawyer advises you it is safe to proceed, how to do it, and if you will be still liable for specific terms in the contract.

An assignment will not be enforced if:

Elements of an Assignment Agreement

Details on the existing agreement: Provides identification data on the existing contract, such as its date of execution and purpose.

Additionally, the assignment contract will contain provisions related to indemnification and governing law.

In M&A, when in need to prove the ownership of specific assets, or if you are facing difficulties in fulfilling your contractual obligations, an assignment and assumption agreement will demonstrate you are the right owner and keep your business’s credibility intact.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Ignite Success with an Effective Assignment and Assumption Agreement: A Comprehensive Guide

LegalGPS : July 29, 2024 at 9:05 AM

Running a successful business is all about staying on top of your game—and that includes being able to navigate legally complex situations with ease. One concept that often comes up in the world of contracts is the assignment and assumption agreement. If you're a business owner who needs a quick yet comprehensive rundown of what an assignment and assumption agreement is and how to create one, you've come to the right place.

Assignment and Assumption Agreement Template

Legal GPS templates are drafted by top startup attorneys and fully customizable.

In this guide, we'll walk you through the ins and outs of assignment and assumption agreements, and even provide you with a step-by-step explanation of how to put one together. So grab your favorite cup of coffee and let's get started!

Being able to efficiently manage and transfer contractual rights and obligations is crucial for businesses of all sizes. Whether you're selling a portion of your company or entering into a new partnership, having a solid assignment and assumption agreement in place can save you time, resources, and potential legal headaches down the line.

That being said, it's important to ensure that your assignment and assumption agreement is accurate, comprehensive, and tailored to suit your specific needs. And that's where this guide comes in. We'll help you understand the role of assignment and assumption agreements in your business and give you the tools you need to create one with confidence.

What is an Assignment and Assumption Agreement?

Before we dive into the nitty-gritty of creating an assignment and assumption agreement, it's important to understand what it is and why it's important for your business. In simple terms, an assignment and assumption agreement is a legal document that transfers the rights and obligations of one party (the "assignor") in an existing contract to another party (the "assignee"). Essentially, it allows one party to step out of a contract and another party to step in, taking over the original party's rights and responsibilities.

An assignment and assumption agreement typically serves a few key purposes, including:

Transferring ownership or control of assets

Refinancing debt or other financial arrangements

Splitting or consolidating business entities

A well-crafted agreement not only helps ensure a smooth transition but also protects all parties involved from potential misunderstandings and disputes.

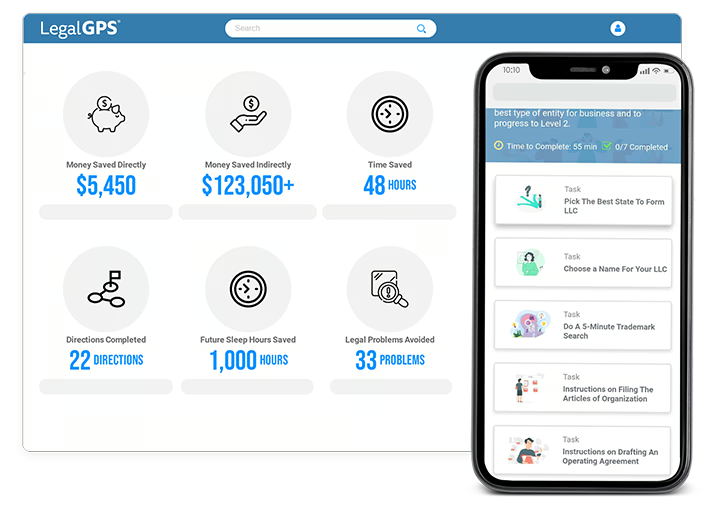

Legal GPS Subscription

Protect your business with our complete legal subscription service, designed by top startup attorneys.

- ✅ Complete Legal Toolkit

- ✅ 100+ Editable Contracts

- ✅ Affordable Legal Guidance

- ✅ Custom Legal Status Report

The Importance of an Accurate Assignment and Assumption Agreement

Now that you have an idea of what an assignment and assumption agreement entails, let's talk about why it's so important to get it right. Without a solid agreement in place, both the assignor and the assignee can face a whole host of problems, from miscommunications to legal disputes.

For one, an unclear or vague agreement can leave both parties open to misinterpretation and misunderstanding, which can result in disputes down the line. This is especially true when considerable assets or financial interests are at stake—having an accurate agreement in place helps protect both parties from future legal battles.

Moreover, without an agreement that specifically assigns rights and obligations to the assignee, the original parties to the contract may still be bound by its terms. This can give rise to unwanted legal complications and may even defeat the purpose of entering into the assignment and assumption agreement in the first place.

In short, a well-written assignment and assumption agreement protects both parties and helps prevent future misunderstandings and disputes.

How to Write an Assignment and Assumption Agreement: Step-by-Step Guide

Now that we've covered why having an accurate assignment and assumption agreement is so crucial, let's walk through how to write one. Keep in mind that every contract is unique, so your agreement should be tailored to your specific situation.

Step 1: Identifying Parties and their Roles

The first step in creating an assignment and assumption agreement is to clearly identify the parties involved and their respective roles. This typically includes the assignor, assignee, and the original counterparty to the contract (the "obligor"). Be sure to include the legal names and contact information for each party, including any business entities, individuals, or other parties that may be involved.

Moreover, all parties should be represented by a lawyer who is licensed to practice law in the state where the property is located.

Step 2: Describing the Original Contract

The next step is to describe the original contract being assigned and assumed, also known as the "underlying contract." This should include a brief description of the terms and conditions of the underlying contract, as well as the date on which it was executed. You may also want to include a reference to the specific section(s) of the underlying contract that permit assignment, if applicable.

For example, if the underlying contract is a lease agreement, you may want to point out that the lease allows for assignment.

Step 3: Detailing the Assignment and Assumption

Now, it's time to get into the heart of the agreement—the actual assignment and assumption. In this section, you'll need to outline the specific rights and obligations being transferred from the assignor to the assignee, including any limitations or conditions related to the transfer.

You should also identify the effective date of the assignment and assumption, which may be the date on which the agreement is executed, or a later date specified by the parties. In some cases, you may also need to consider any rights or obligations that will remain with the assignor after the assignment and assumption take effect.

Step 4: Consent of the Obligor

In some cases, the assignment and assumption of a contract may require the consent of the obligor. If this is the case, you should include a section in your agreement describing the obligor's consent, including any conditions or limitations on the consent, if applicable.

This is important because if the obligor does not consent or if there are conditions on the consent, it may prevent your assignment and assumption from taking effect.

Step 5: Governing Law and Jurisdiction

It's crucial to establish which laws will govern your assignment and assumption agreement, in case any disputes arise later on. Include a section specifying the state or country whose laws will apply to the agreement, as well as the jurisdiction where any legal disputes will be resolved.

However, make sure the law you choose is not one that would be considered unfair to either party. For example, if one of your companies is based in a state that has laws favorable to creditors and the other company is based in a state with more favorable laws for debtors, it may be best to choose another state as your governing law.

Step 6: Signatures

Finally, the last step in creating an assignment and assumption agreement is to have all parties sign and date the document. This is typically done at the end of the agreement, after all terms and conditions have been outlined. Be sure to include lines for the signatures of the assignor, assignee, and the obligor (if their consent is required), as well as a space for each party to print their name and title, if applicable.

Get Your Assignment and Assumption Agreement Template with a Legal GPS Subscription

Pros and Cons of Using an Assignment and Assumption Agreement Template

When it comes to creating an assignment and assumption agreement, you might be considering using a contract template. While templates definitely have their advantages, such as saving time and ensuring that you cover all of the necessary legal bases, there are also some potential downsides to be aware of.

One major advantage of using a template is that it can save you time by providing a well-structured starting point for your agreement. Templates also generally include the essential sections and clauses that most agreements need, helping to ensure that your agreement is legally compliant and thorough.

The main disadvantage of using a generic template is that it may not be tailored precisely to your specific needs. This can result in an agreement that doesn't fully address the nuances of your situation or provide adequate protection for all parties involved. If you're unsure about whether a template is appropriate for your situation, you should consider consulting a legal professional or purchasing a customizable contract template that can be adapted to your specific circumstances.

The Benefits of Choosing Our Contract Template

There's no doubt that a well-designed contract template can be a game-changer when it comes to drafting assignment and assumption agreements. And that's where our expertly crafted template comes into play. Here's what sets our template apart:

Designed by legal professionals with years of experience

Simplified language for easier understanding

Customizable to suit your specific needs and requirements

By choosing our contract template, you can feel confident knowing that you're getting a legally compliant and strategically sound agreement that's tailored to your situation. So why wait? Purchase our expertly designed assignment and assumption agreement template and ensure your business's success today!

In the world of business, contracts play a crucial role in protecting your assets and interests. And when it comes to assignment and assumption agreements, accuracy and clarity are key. We hope this comprehensive guide has given you the tools and understanding you need to confidently create your own assignment and assumption agreements.

Ready to make your life easier? Grab our expertly designed assignment and assumption agreement template today and streamline your business operations with confidence!

Get Legal GPS's Assignment and Assumption Agreement Template Now

Understanding Assumption Agreements: A Simple Guide

Have you ever heard of the term "assumption agreement" and wondered what it meant? You're not alone. To understand assumption agreements, we need to...

Secure Your Company's IP with a Confidentiality and Intellectual Property Assignment Agreement: The Essential Guide

As an entrepreneur, one of your most valuable assets is your company's intellectual property (IP). From trade secrets and customer lists to patented...

Demystifying Assignment of Lease: Your Go-To Guide

When you’re talking about property leasing, it’s important to understand that there are a lot of terms and concepts that you may have never heard...

What is an Assignment and Assumption Agreement: Everything You Need to Know

An assignment and assumption agreement is an agreement for transferring contractual duties and rights. 3 min read updated on January 01, 2024

“What is an assignment and assumption agreement?” is a question that you may find yourself asking if you intend to end your involvement in contract by letting another person step into your shoes. An assignment and assumption agreement is an agreement for transferring contractual duties and rights. It is a separate agreement from the one being transferred. The original contract may contain certain terms and conditions regarding assignments and assumptions, so it is important for the parties involved to review the contract carefully before proceeding with the transfer.

What Is an Assignment and Assumption Agreement?

Also referred to as an assignment and assumption, an assignment and assumption agreement is an agreement that is established when one party of a contract wishes to transfer his or her contractual obligations and rights to another party. The party who is transferring his or her rights is called the assignor, while the one receiving them is known as the assignee.

In some situations, an assignor will not be completely released from liability even after he or she has assigned the contract. The parties should look closely at the specific language in the contract to determine the restrictions and terms that apply to assignments and assumptions. An agreement for an assignment and assumption is a document that is separate from the contract it transfers.

Reasons for Creating an Assignment and Assumption Agreement

After two parties enter into a contract , a change in business climate, one party's equity, or other factors may make it necessary to assign the contract. If both parties agree to the assignment and sign the necessary documents to transfer existing duties and interests, an agreement may be assigned to and assumed by another party.

A business may lose its foothold in the marketplace or one of contracting parties may fail to perform its contractual obligations due to changing local laws. Instead of leaving parties bound to an irrelevant or dated agreement , an assignment makes it possible for struggling or incapable parties to be replaced with parties that are more capable of responding to the requirements and goals of the contract. The process of assignment itself enables the parties to continue a dialogue, which can help develop and solidify a successful business relationship.

A Guide to Creating an Assignment and Assumption Agreement

Sometimes, a contract may have specific rules regarding what type of assignment is permitted, who can receive the assignment, and how the assignment should be processed. It is essential that you read the original contract to ensure that all contracting parties have met all the requirements for assignments and assumptions. Each party should be given enough time to review both the initial agreement and the assignment. This will help prevent the situation where one party claims that he or she does not understand the terms and their effect on the agreement or his or her rights and duties.

In addition, you and the other party should carefully review the assignment to make sure that it includes all relevant deal points. Avoid assuming that both parties have agreed to certain terms or expectations even if they are not clearly stated in the document. It is better to over-include than under-include terms in the agreement. Since the terms of the initial agreement are still effective, both parties should continue to fulfill their contractual obligations until the assignment is signed and completed.

Three copies of the assignment and assumption agreement must be signed: two for the initial contracting parties and one for the assignee. Your copy of the signed assignment agreement should be kept with the original agreement. Once the assignment is created and signed, it will become part of the initial contract and should be treated as such. Depending on the terms of the agreement , you may want to have the assignment witnessed or notarized. By doing so, you can avoid the situation where someone challenges the validity of a signature.

What to Include in an Assignment and Assumption Agreement

An assignment and assumption agreement can be written in many different ways. In many instances, such an agreement includes the following:

- Names of assignor and assignee

- Whereas clause stating that both assignor and assignee have agreed to the assignment

- Statement of assignment

- Statement of assumption

- Effective date of assignment

- Statement about future transfers and assignments to permitted successors

- Declaration that the agreement can be executed in counterparts

- Statement confirming the presence of witnesses

- Signatures of the assignor and assignee

If you need help drafting an assignment and assumption agreement, you can post your legal need on UpCounsel's marketplace. UpCounsel accepts only the top 5 percent of lawyers to its site. Lawyers on UpCounsel come from law schools such as Harvard Law and Yale Law and average 14 years of legal experience, including work with or on behalf of companies like Google, Menlo Ventures, and Airbnb.

Hire the top business lawyers and save up to 60% on legal fees

Content Approved by UpCounsel

- Assignment Law

- Legal Assignment

- Assignment of Rights Example

- Assignment Contract Law

- Assignment of Rights and Obligations Under a Contract

- What Is the Definition of Assigns

- Assignment Legal Definition

- Assignment Of Contracts

- Assignment of Contract Rights

- Consent to Assignment

Book Legal Services Online

ASSIGNMENT AND ASSUMPTION AGREEMENTS

The Assignment and Assumption Agreement

An assignment and assumption agreement is used after a contract is signed, in order to transfer one of the contracting party’s rights and obligations to a third party who was not originally a party to the contract. The party making the assignment is called the assignor, while the third party accepting the assignment is known as the assignee.

In order for an assignment and assumption agreement to be valid, the following criteria need to be met:

The initial contract must provide for the possibility of assignment by one of the initial contracting parties. The assignor must agree to assign their rights and duties under the contract to the assignee. The assignee must agree to accept, or “assume,” those contractual rights and duties. The other party to the initial contract must consent to the transfer of rights and obligations to the assignee. A standard assignment and assumption contract is often a good starting point if you need to enter into an assignment and assumption agreement. However, for more complex situations, such as an assignment and amendment agreement in which several of the initial contract terms will be modified, or where only some, but not all, rights and duties will be assigned, it’s a good idea to retain the services of an attorney who can help you draft an agreement that will meet all your needs.

The Basics of Assignment and Assumption

When you’re ready to enter into an assignment and assumption agreement, it’s a good idea to have a firm grasp of the basics of assignment:

First, carefully read and understand the assignment and assumption provision in the initial contract. Contracts vary widely in their language on this topic, and each contract will have specific criteria that must be met in order for a valid assignment of rights to take place.

All parties to the agreement should carefully review the document to make sure they each know what they’re agreeing to, and to help ensure that all important terms and conditions have been addressed in the agreement. Until the agreement is signed by all the parties involved, the assignor will still be obligated for all responsibilities stated in the initial contract. If you are the assignor, you need to ensure that you continue with business as usual until the assignment and assumption agreement has been properly executed.

Filling in the Assignment and Assumption Agreement

Unless you’re dealing with a complex assignment situation, working with a template often is a good way to begin drafting an assignment and assumption agreement that will meet your needs. Generally speaking, your agreement should include the following information:

Identification of the existing agreement, including details such as the date it was signed and the parties involved, and the parties’ rights to assign under this initial agreement

The effective date of the assignment and assumption agreement

Identification of the party making the assignment (the assignor), and a statement of their desire to assign their rights under the initial contract

Identification of the third party accepting the assignment (the assignee), and a statement of their acceptance of the assignment

Identification of the other initial party to the contract, and a statement of their consent to the assignment and assumption agreement

A section stating that the initial contract is continued; meaning, that, other than the change to the parties involved, all terms and conditions in the original contract stay the same

In addition to these sections that are specific to an assignment and assumption agreement, your contract should also include standard contract language, such as clauses about indemnification, future amendments, and governing law.

Sometimes circumstances change, and as a business owner you may find yourself needing to assign your rights and duties under a contract to another party. A properly drafted assignment and assumption agreement can help you make the transfer smoothly while, at the same time, preserving the cordiality of your initial business relationship under the original contract.

AFFIDAVIT OF SURVIVORSHIP affidavit of title BUYERS commercial real estate COMMON LAW MARRIAGE contract for deed DEATH AND REAL ESTATE Deed estate planning estate planning real estate trends FSBO future of commercial real estate Future of real estate home buying Home seller home selling inheritance KC real estate LANDLORD Landlords land use midwest real estate PROBATE Property Management real estate closing real estate contracts real estate deeds Real estate deed work real estate ethics real estate finance Real estate financing real estate investing real estate lawyer real estate management real estate market real estate markets real estate planning real estate transactions real estate trends seller financing SELLERS SURVIVORSHIP AFFIDAVIT TENANTS IN COMMON TRANSFER ON DEATH DEED wholesale real estate

- RATE LOCKED HOME OWNERS AND LACK OF HOUSING INVENTORY FOR SALE

- SOLAR PANELS AND HOMES ASSOCIATIONS IN MISSOURI

- Quit Claim Deed Kansas City

- What is mirror wrap real estate?

- JACKSON COUNTY MISSOURI TAX SALES

- capital gains tax

- contract for deed

- Estate Planning

- For Sale by Owner

- Home Buying

- Home Selling

- Mirror Wrap Real Estate

- Missouri Easement Law

- Quick Claim Deed

- Quit Claim Deed

- Quit Claim Deeds Kansas

- QuitClaim Deeds

- Quitclaim Deeds Kansas

- Real Estate Brokers

- real estate finance, FSBO, real estate markets, home buyers, home sellers

- Real Estate Markets

- Register Quickclaim Deeds

- seller lied on disclosure missouri

- Tax-Related Issues

- Title Issues

- who pays property tax

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| 8 | 10 | 11 | ||||

| 12 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 24 | 25 | ||

| 26 | 27 | 29 | 30 | |||

People also asked "How to register a deed online in Kansas or Missouri?"

- Kansas quit claim deed

- Quit claim deed kansas

- Quit claim deed Missouri

- Quitclaim deed Missouri

- Quit claim deed loopholes

- Missouri beneficiary deed problems

- Correction deed

- Quit claim deed

- Missouri on death deed

- A potential danger involved in a contract for deed is that

- Kansas quit claim deed form

- Kansas transfer on death deed form

- Quit claim deed form Kansas

- Quit claim deed divorce

- Transfer on death deed Kansas

- Kansas quitclaim deed

- Missouri beneficiary deed

- Contract for deed Kansas

- Life estate deed Kansas

- Quick claim deed Kansas

- Deed transfer lawyer

- Life estate deed

- Quitclaim deed defintion

- Missouri life estate deed

- Kansas quick claim deed

- Missouri quitclaim deed

- Beneficiary deed form Missouri

- Missouri transfer on death deed form

- Closing documents

- Land trust documents

Partnership

Sole proprietorship, limited partnership, compare businesses, employee rights, osha regulations, labor hours, personal & family, child custody & support, guardianship, incarceration, civil and misdemeanors, legal separation, real estate law, tax, licenses & permits, business licenses, wills & trusts, power of attorney, last will & testament, living trust, living will.

- Share Tweet Email Print

COMPARE BUSINESSES

The definition of assignment & assumption agreement.

By Rebecca K. McDowell, J.D.

October 19, 2019

Reviewed by Michelle Seidel, B.Sc., LL.B., MBA

Learn About Our Review Process

Our Review Process

We write helpful content to answer your questions from our expert network. We perform original research, solicit expert feedback, and review new content to ensure it meets our quality pledge: helpful content – Trusted, Vetted, Expert-Reviewed and Edited. Our content experts ensure our topics are complete and clearly demonstrate a depth of knowledge beyond the rote. We are incredibly worried about the state of general information available on the internet and strongly believe our mission is to give voice to unsung experts leading their respective fields. Our commitment is to provide clear, original, and accurate information in accessible formats. We have reviewed our content for bias and company-wide, we routinely meet with national experts to educate ourselves on better ways to deliver accessible content. For 15 years our company has published content with clear steps to accomplish the how, with high quality sourcing to answer the why, and with original formats to make the internet a helpful place. Read more about our editorial standards .

- Land Contract Law in Florida

Assignments and assumptions are part of contract law and refer to the transfer of someone's duties and benefits in a contract to another. Assignments and assumptions are common with respect to contracts for loans or leases. A lender or lessor may assign its rights to another lender or lessor, and a borrower or lessee may find someone to assume the loan or lease and make the payments.

The Elements of a Contract

A contract is legally formed when two or more parties enter into an agreement with certain elements, which include:

- An offer. For instance, in a mortgage transaction, the lender offers to loan money to the borrower.

- Acceptance of the offer. The mortgage borrower agrees to borrow the money.

- Consideration. Consideration in a contractual relationship means the things the two parties give to each other in exchange for entering the contract. A mortgage lender loans money to the borrower, and in exchange, the borrower agrees to repay the money and give the lender a lien on the house. The loan, the repayment with interest and the mortgage lien are consideration for the contract.

- Mutuality. The parties must have come together and agreed upon the terms of the contract Read More: How Does a Contract Work?

Burdens and Benefits of a Contract

The contract sets forth what the parties are required to do during the contractual relationship. With a mortgage, the lender is required to loan the money and apply the payments correctly in accordance with the agreement, and then release the lien when the loan is paid. The borrower is required to pay the loan back with interest, pay the property taxes and make sure the property has insurance.

These contractual obligations create both burdens and benefits on both sides. The lender has the burden of making the loan and applying the payments correctly, but it has the benefit of receiving interest on the loan. The borrower has the burdens of making payments and insuring the property but has the benefit of owning the home.

Assigning a Contract

An assignment occurs when one party to a contract transfers, or assigns, its rights and obligations under the contract to another party. This happens frequently with mortgage loans, as lenders sell loans to other lenders. The lender will enter into an assignment agreement and assign the note and the mortgage to another party. The borrower then must make the payments to the assignee. The assignee's right and obligations under an assignment are the same as the assignor's rights and obligations and cannot be changed without a new contract.

Assuming a Contract

An assumption is the other side of the coin, in a sense. Assumptions are common with respect to leases and mortgages and typically occur when the borrower or lessee wants to transfer the property to someone else without paying off the loan or lease. Assumption means someone is taking over the side of the contract that requires payment.

If the contract allows it, another person can agree to assume the original party's obligations under the contract – the obligations to make monthly payments, etc. – in exchange for taking over the ownership or the lease.

Not every contract can be assumed. The language of the contract will state whether the borrower or lessee is allowed to transfer the property or lease by assumption.

Assignment and Assumption Agreements

Assignments and assumptions are both conducted by written agreement. Sometimes an assignment and an assumption will occur in the same transaction, and one agreement will cover both; the parties are assigning the benefits and assuming the burdens.

Assignments and assumptions are both transfers of contractual benefits and burdens from one party to another. They differ from each other based on the original position of the transferring party and the duties and benefits being transferred.

- Bankrate: Assumable Mortgage: Take Over Seller's Loan

- The Law Dictionary: What is Assumption?

- Nolo: What Is an Assignment of Contract?

- U.S. Legal: Elements of a Contract

Rebecca K. McDowell is a creditors' rights attorney with a special focus on bankruptcy and insolvency. She has a B.A. in English from Albion College and a J.D. from Wayne State University Law School. She has written legal articles for Nolo and the Bankruptcy Site.

Related Articles

- The Definition of a Leasehold Deed of Trust

- What Is a Deed of Trust With Assignment of Rents?

- What is an Assignment of Trust Deed?

Assumption Agreement: Definition & Sample

Jump to section, what is an assumption agreement.

An assumption agreement, sometimes called an assignment and assumption agreement, is a legal document that allows one party to transfer rights and/or obligations to another party. It allows one party to "assume" the rights and responsibilities of the other party. This agreement is often used in real estate transactions and mortgage lending.

A seller may include an assumption agreement in order to provide legal protection by transferring obligations to a buyer. If a buyer then decides to default on a mortgage or otherwise go against the contract, the original seller would not be held liable.

Assumption Agreement Sample

Reference : Security Exchange Commission - Edgar Database, EX-10 8 exhibit107.htm ASSUMPTION AGREEMENT , Viewed October 13, 2021, View Source on SEC .

Who Helps With Assumption Agreements?

Lawyers with backgrounds working on assumption agreements work with clients to help. Do you need help with an assumption agreement?

Post a project in ContractsCounsel's marketplace to get free bids from lawyers to draft, review, or negotiate assumption agreements. All lawyers are vetted by our team and peer reviewed by our customers for you to explore before hiring.

ContractsCounsel is not a law firm, and this post should not be considered and does not contain legal advice. To ensure the information and advice in this post are correct, sufficient, and appropriate for your situation, please consult a licensed attorney. Also, using or accessing ContractsCounsel's site does not create an attorney-client relationship between you and ContractsCounsel.

Meet some of our Assumption Agreement Lawyers

With 20 years of transactional law experience, I have represented corporate giants like AT&T and T-Mobile, as well as mid-size and small businesses across a wide spectrum of legal needs, including business purchase agreements, entity formation, employment matters, commercial and residential real estate transactions, partnership agreements, online business terms and policy drafting, and business and corporate compliance. Recognizing the complexities of the legal landscape, I am dedicated to providing accessible and transparent legal services by offering a flat fee structure, making high-quality legal representation available to all. My extensive knowledge and commitment to client success establishes me as a trusted advisor for businesses of all sizes.

Business-minded, analytical and detail-oriented attorney with broad experience in real estate and corporate law, with an emphasis on retail leasing, sales and acquisitions and real estate finance. Extensive experience in drafting complex commercial contracts, including purchase and sale contracts for businesses in a wide variety of industries. Also experienced in corporate formation and governance, mergers and acquisitions, employment and franchise law. Admitted to practice in Colorado since 2001, Bar No. 33427.

Attorney Garrett Mayleben's practice is focused on representing small businesses and the working people that make them profitable. He represents companies in structuring and negotiating merger, acquisition, and real estate transactions; guides emerging companies through the startup phase; and consults with business owners on corporate governance matters. Garrett also practices in employment law, copyright and trademark law, and civil litigation. Though industry agnostic, Garrett has particular experience representing medical, dental, veterinary, and chiropractic practices in various business transactions, transitions, and the structuring of related management service organizations (MSOs).

I was born in Charlotte, NC and primarily raised in Dalton, GA. I graduated from Dalton High School in 1981 where I was in the band and the French club. I also participated in Junior Achievement and was a member of Tri-Hi-Y. New York granted my first license as an attorney in 1990. I then worked as a partner in the firm of Broda and Burnett for almost 10 years and as a solo practitioner for about 2 years. I worked as a general practitioner (primarily doing divorces, child abuse cases, custody matters and other family law matters, bankruptcy, real estate closings, contracts, taxes, etc.) and as a Law Guardian (attorney who represents children). I obtained my license in Tennessee in December 2002 and began working as an associate at Blackburn & McCune from February of 2003 until May of 2005. At Blackburn & McCune I provided telephone legal counsel to Prepaid Legal Services (now known as Legal Shield) members, wrote letters for members, reviewed contracts, attended hearings on traffic ticket matters and represented members with regard to IRS matters. In May of 2005, I went to work for North American Satellite Corporation where I served as Corporate Counsel. I handled a number of taxation issues, reviewed and wrote contracts, counseled the CEO and Board of Directors on avoiding legal problems and resolving disputes, and represented employees on a variety of matters, and also assisted the company for a period of time as its Director of Accounting. In 2010, I volunteered as a law clerk for Judge Robert Adams in Dalton, Georgia until I obtained my license to practice law in Georgia in November, 2010. In Georgia, I have handled a variety of family law matters, drafted wills, advanced health care directives, power of attorney documents, reviewed and drafted contracts, and conducted real estate closings. Currently, I accept cases in the areas of adoption, child support, custody, divorce, legitimation and other family law matters. In addition, I handle name change petitions and draft wills.

Michigan and USPTO licensed attorney with over 20 years of experience on counseling clients in the fields of intellectual property, transactional law, technology involvement, negotiations, and business litigation.

Attorney with over 10+ years' experience and have closed over $1 Billion in real estate, telecommunications, & business transactions

I am an attorney with over 13 years experience licensed in both Illinois and Indiana. I spent the early part of my career as a civil litigation attorney. Eventually, I moved into an in-house role, specifically as general counsel, to help companies avoid the pains of litigation. In doing so, I gained significant experience in executive leadership, corporate governance, risk management and cybersecurity/privacy. I bring this wealth of experience to my client engagements to not only resolve the immediate issue, but help implement lasting improvements in practices to avoid similar problems going forward.

Find the best lawyer for your project

Quick, user friendly and one of the better ways I've come across to get ahold of lawyers willing to take new clients.

How It Works

Post Your Project

Get Free Bids to Compare

Hire Your Lawyer

Business lawyers by top cities

- Austin Business Lawyers

- Boston Business Lawyers

- Chicago Business Lawyers

- Dallas Business Lawyers

- Denver Business Lawyers

- Houston Business Lawyers

- Los Angeles Business Lawyers

- New York Business Lawyers

- Phoenix Business Lawyers

- San Diego Business Lawyers

- Tampa Business Lawyers

Assumption Agreement lawyers by city

- Austin Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- Boston Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- Chicago Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- Dallas Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- Denver Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- Houston Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- Los Angeles Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- New York Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- Phoenix Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- San Diego Assumption Agreement Lawyers

- Tampa Assumption Agreement Lawyers

Contracts Counsel was incredibly helpful and easy to use. I submitted a project for a lawyer's help within a day I had received over 6 proposals from qualified lawyers. I submitted a bid that works best for my business and we went forward with the project.

I never knew how difficult it was to obtain representation or a lawyer, and ContractsCounsel was EXACTLY the type of service I was hoping for when I was in a pinch. Working with their service was efficient, effective and made me feel in control. Thank you so much and should I ever need attorney services down the road, I'll certainly be a repeat customer.

I got 5 bids within 24h of posting my project. I choose the person who provided the most detailed and relevant intro letter, highlighting their experience relevant to my project. I am very satisfied with the outcome and quality of the two agreements that were produced, they actually far exceed my expectations.

Want to speak to someone?

Get in touch below and we will schedule a time to connect!

Find lawyers and attorneys by city

Assignment and Assumption Agreement | Practical Law

Assignment and Assumption Agreement

Practical law standard document 0-381-9984 (approx. 10 pages).

| Maintained • USA (National/Federal) |

Understanding the Basics of Assignment and Assumption Agreements

Try our Legal AI - it's free while in beta 🚀

Genie's Legal AI can draft , risk-review and negotiate 1000s of legal documents

Note: Links to our free templates are at the bottom of this long guide. Also note: This is not legal advice

Introduction

Understanding the importance of assignment and assumption agreements is essential for any business transaction. These agreements are legal documents which outline the transfer of ownership, rights, and obligations from one party to another in order to protect both parties from liabilities and disputes. Moreover, they help streamline the transition of ownership by providing a clear agreement between all involved.

At Genie AI, we understand that navigating these agreements can be difficult without legal expertise - but it doesn’t have to be! Our team provides free assignment and assumption agreement templates so that anyone can draft high-quality legal documents without paying hefty lawyer fees.

These agreements are crucial in corporate mergers, asset sales, and other business transactions as they protect both assignee and assignor from potential future disputes or disagreements. Furthermore, it helps everyone involved in the process come to an agreement about the transfer of assets or liabilities.

It’s also important for businesses to ensure that all records, documents, and information is properly transferred when assigning contracts - something which assignment and assumption agreements make simpler. Not only does this avoid any potential issues in the future but ultimately makes for a smoother transition when dealing with such matters.

In short, assignment and assumption agreements provide an invaluable service when it comes to safeguarding both parties involved in a business transaction while also simplifying their processes along the way. To learn more about how our team at Genie AI can help you on your way towards drafting these essential documents - read on below for our step-by-step guidance or visit us today to access our template library!

Definitions

Assignor: The party transferring the rights and liabilities. Assignee: The party receiving the rights and liabilities. Asset Assignment and Assumption Agreement: An agreement used when one party transfers all or part of their ownership of a particular asset to another party. Liability Assignment and Assumption Agreement: An agreement used when one party transfers all or part of their liability to another party. Contract Assignment and Assumption Agreement: An agreement used when one party transfers all or part of their contractual obligations to another party. Lease Assignment and Assumption Agreement: An agreement used when one party transfers all or part of their responsibilities under a lease to another party. Representations and Warranties: Promises made by the Assignor and Assignee in order to ensure they understand the risks associated with the transfer and are comfortable taking on the rights and liabilities. Indemnification: A clause outlining the terms under which the Assignor and Assignee are liable for any losses or damages due to the transfer. Choice of Law: A clause specifying which jurisdiction’s laws will govern the agreement. Severability: A clause outlining how the agreement will be enforced if any part of it is deemed unenforceable. Governing Law: A clause specifying which court will have jurisdiction over any disputes that arise out of the agreement. Notices: A clause outlining how notices between the parties will be delivered.

Definition of Assignment and Assumption Agreement

Overview of the different types of assignment and assumption agreements, asset assignment and assumption agreement, liability assignment and assumption agreement, contract assignment and assumption agreement, lease assignment and assumption agreement, the purpose of an assignment and assumption agreement, the process of negotiating an assignment and assumption agreement, identifying the parties involved, discussing the terms, drafting the agreement, final review and signing, key terms and clauses commonly found in assignment and assumption agreements, assignor & assignee, liabilities and obligations, representations and warranties, indemnification, choice of law, severability, governing law, potential issues that may arise when negotiating an assignment and assumption agreement, scope of liabilities, representations & warranties, dispute resolution, contractual limitations, practical considerations when drafting an assignment and assumption agreement, identifying contingent liabilities, understanding applicable laws, drafting clear & concise language, complying with any regulatory requirements, potential benefits of using an assignment and assumption agreement, risk reduction, asset protection, cost savings, potential pitfalls of using an assignment and assumption agreement, unforeseen risks, negotiating difficulties, regulatory non-compliance, conclusion and next steps, finalizing the agreement, implementing the agreement, documenting the outcome, get started.

- Understand the legal definition of an Assignment and Assumption Agreement: an agreement between two parties, which transfers one party’s rights, duties and obligations under a contract to another party

- Learn who can enter into an Assignment and Assumption Agreement: the parties to the original contract, or their successors

- Know what rights and obligations are transferred under an Assignment and Assumption Agreement: all rights, duties, and obligations that have been agreed upon in the original contract

- Be aware of the consequences of assigning and assuming obligations: the assignee is responsible for performing all duties and obligations of the contract, just as if they had originally entered into the contract.

- When you can check off this step: You will know you have a good understanding of the definition of an Assignment and Assumption Agreement when you can explain it in your own words and are aware of the rights and obligations transferred and the consequences of assigning and assuming obligations.

- Understand the three common types of assignment and assumption agreements: asset assignment and assumption agreement, contractual assignment and assumption agreement, and debt assignment and assumption agreement

- Learn the key features of each type, including the type of asset or obligation being assigned and assumed

- Determine the purpose of the agreement and the advantages of each type of agreement

- Check off this step when you feel confident that you understand the purpose and differences between the three types of assignment and assumption agreements.

- Research and understand the definitions of an asset assignment and assumption agreement

- Learn the different types of assets that can be assigned and assumed in an agreement

- Understand the purpose of an asset assignment and assumption agreement

- Research and review the legal elements of an asset assignment and assumption agreement, such as the parties involved, the assignor and assignee, the description of the assets to be assigned and assumed, the consideration for the assignment and assumption, the representations and warranties of both parties, the indemnification and other relevant provisions

- Draft an asset assignment and assumption agreement with the help of a qualified attorney

- When you are satisfied with the asset assignment and assumption agreement that you have drafted, execute the agreement according to the applicable law and have it notarized

- Check this off your list and move on to the next step, which is understanding liability assignment and assumption agreements.

- Research applicable state and federal laws to ensure the agreement is in compliance

- Draft a liability assignment and assumption agreement that assigns all liabilities of the transferor to the transferee

- Identify all liabilities to be assigned, including any and all warranty liabilities, product liabilities, and medical liabilities

- Include all necessary clauses that provide for the transfer of the liabilities, and state that the transferor will not be liable for any liabilities after the date of the agreement

- Get the agreement approved by the assigning and assuming parties

- Sign and date the agreement in the presence of a witness

- Once all parties have signed the agreement, you can check this off your list and move on to the next step of drafting the Contract Assignment and Assumption Agreement.

- Understand the difference between an assignment and an assumption agreement. An assignment agreement transfers the rights and obligations of the original contract from one party to another, while an assumption agreement transfers only the obligations of the original contract to the new party.

- Familiarize yourself with the language of the assignment and assumption agreement. The agreement should clearly state the terms of the assignment, the obligations assumed by the new party, and the liabilities being transferred.

- Draft the assignment and assumption agreement. Make sure to include all relevant details, such as the parties involved, the original contract being transferred, the new obligations assumed by the new party, and any other important information.

- Review the agreement with a legal professional. It is important to have a lawyer or other legal professional review the agreement to make sure it meets all legal requirements.

- Sign the agreement. Once both parties have signed the agreement, it is officially binding and the obligations of the original contract are now transferred to the new party.

You will know when you can check this off your list and move on to the next step when you have completed all steps in this section, including drafting, reviewing, and signing the agreement.

- Understand the basics of a lease assignment and assumption agreement

- Have an understanding of the parties involved in the agreement

- Know what is included in the agreement such as the particular lease, the transferor, the transferee, a consideration amount, date of assignment, and other related documents

- Have an understanding of the legal implications of the agreement as far as warranties, liabilities, and other related obligations

- Understand the process of executing the agreement and any other related steps required

- Be aware of any local or state laws that may affect the agreement

Once you have a thorough understanding of the lease assignment and assumption agreement, you can check off this step and move on to the next step in the guide: The Purpose of an Assignment and Assumption Agreement.

- Understand the purpose of an assignment and assumption agreement, which is to transfer rights and obligations from one party to another

- Learn the different types of assignment and assumption agreements, such as lease assignment and assumption agreements, purchase and sale agreements, and contracts

- Identify the parties involved in the agreement, what rights and obligations are being transferred, and how the agreement will be executed

- Once you understand the purpose of an assignment and assumption agreement, you can move on to the next step in the guide

- Research and determine the terms of the agreement that are appropriate for your situation

- Identify any potential legal issues that could arise from the assignment and assumption agreement

- Draft the agreement that outlines the terms, conditions, consideration, and liabilities

- Both parties must review and approve the agreement in its entirety

- Make sure the agreement is signed by both parties and that each party has a copy of the agreement

- When both parties have agreed upon and signed the agreement, the assignment and assumption agreement is officially enforceable

- You can check this step off your list and move onto the next step once the agreement is signed and all parties have a copy.

- Identify all parties involved in the agreement, including the assignor, the assignee, and any other third parties

- Be sure to document all of the parties in the agreement and provide contact information for each

- Get contact information for all parties involved, including names, addresses, and phone numbers

- Verify that all parties involved are of legal age and able to enter into a binding agreement

- Make sure that all parties understand their roles and obligations in the agreement

When you can check this off your list: When all parties have been identified, contact information has been provided, and all parties understand and accept their roles and obligations in the agreement.

- Learn the key terms used in assignment and assumption agreements, such as “assignor” and “assignee.”

- Understand the scope of the agreement and the rights and obligations of each party.

- Consider any potential restrictions that might be in place.

- Identify any laws or regulations that affect the agreement.

You can check this step off your list and move on to the next step when you have a basic understanding of the terms used in the agreement, and the scope of the agreement and the rights and obligations of each party.

- Determine the parties involved in the assignment and assumption agreement and obtain contact information for each.

- Draft the agreement and include all the agreed upon terms and conditions.

- Review the agreement with all parties to ensure the terms and conditions are accurately reflected.

- Revise the agreement as needed to reflect any changes or amendments.

- Once all parties have agreed to the agreement and all revisions have been made, the agreement is ready to be signed.

- Carefully review the agreement to ensure that all the details and clauses are accurately reflected

- Make sure all parties to the agreement have signed the document

- Have all parties to the agreement keep a signed copy of the document for their records

- Once all parties have signed the document, you can check this off your list and move on to the next step.

- Familiarize yourself with the language and terminology used in assignment and assumption agreements.

- Understand the components of the agreement, such as the assignor, assignee, consideration, and liabilities.

- Become familiar with the common clauses found in assignment and assumption agreements, such as the warranty clause, assignment clause, and liability clause.

- Review the agreement for accuracy and ensure that all of the terms and conditions are clear.

- Once you have a full understanding of the key terms and clauses in the agreement, you can move on to the next step in the process.

- Determine who is the assignor and who is the assignee - the assignor is the one who is transferring their rights and obligations to the assignee

- Know the difference between the assignor and assignee - the assignor is the party transferring the rights and obligations, and the assignee is the party receiving them

- Understand the implications of the assignment and assumption agreement - the assignor is no longer responsible for the rights and obligations they are transferring to the assignee

- Make sure that the assignor and assignee are both aware of their respective roles and responsibilities - this will ensure that the agreement is legally binding

Once you have determined who the assignor and assignee are, know the differences between them, understand the implications of the agreement, and make sure both parties are aware of their roles and responsibilities, you can move on to the next step.

- Identify and list out all of the liabilities and obligations that are being assigned in the agreement

- Ensure that all liabilities and obligations of the assignor that are to be assumed by the assignee are included in the agreement

- Specify the date on which the liabilities and obligations are to be assumed by the assignee in the agreement

- Make sure that the assignee is aware of and accepts the liabilities and obligations that are being assigned

- Confirm that the assignor is not liable for any of the liabilities and obligations that are being assigned to the assignee

- Make sure to include a clause in the agreement that states that the assignor will not be liable for any of the liabilities and obligations that are being assigned to the assignee

When you can check this off your list and move on to the next step:

- When the assignor and assignee have agreed on all of the liabilities and obligations that are being assigned in the agreement

- When the assignor has agreed to not be liable for any of the liabilities and obligations that are being assigned to the assignee

- When the agreement has been reviewed and approved by both the assignor and assignee

- Ensure that all statements made by the assignor and the assignee are accurate and current

- Identify all representations and warranties made by the assignor to the assignee

- Make sure that any representations and warranties made by the assignor are clear and enforceable

- Verify that any representations and warranties made by the assignee are accurate and up-to-date

- Determine the remedies for breach of any representations and warranties

You can check this off your list and move on to the next step when you have identified all representations and warranties, verified that they are accurate and up-to-date, and determined the remedies for breach.

- Assignor should agree to indemnify Assignee from any and all claims, losses and damages that arise from breach of representations and warranties

- Assignor should agree to pay Assignee’s legal fees and other costs associated with defending against any claim

- Assignee should agree to indemnify Assignor from any and all claims, losses, and damages that arise from the Assignee’s actions after the transfer of the subject matter

- Once these indemnification terms are set, you can check this step off your list and move on to the next step.

- Determine the state law that will govern the agreement. Generally, the state law that will be applicable is the state in which the agreement is executed.

- The state law that you choose should be clear and explicit. Consider consulting a lawyer or legal advisor if you are unsure of the applicable state law.

- Make sure to include the state law that has been agreed upon in the agreement.

- Check off this step when the applicable state law has been determined and included in the agreement.

- Read your agreement carefully to ensure that the severability clause is properly drafted

- The severability clause should state that if any portion of the agreement is found to be invalid or unenforceable, the remaining provisions will remain in full force and effect

- Familiarize yourself with the definitions of severability, enforceability, and invalidity

- Make sure that the agreement includes a severability clause that is tailored to the particular agreement

- Once you are confident that the severability clause is properly drafted, you can check this step off your list and move on to the next step.

- Research governing laws in the jurisdiction where the agreement will be signed and enforced

- Determine the laws that will govern the agreement and include them in the governing law clause

- This clause should include the state, country, or other jurisdiction

- Once you have determined the governing laws and included them in the clause, you can check this off your list and move on to the next step.

- Ensure that the agreement includes a provision specifying a proper notice address for each party

- Check that the notice provision includes the name and address of the recipient, the method of service (e.g., mail, e-mail, or fax), and the time period for responding

- Review the agreement to make sure that it includes a provision specifying the manner in which the parties will provide notice to each other

- Confirm that notice is defined correctly, as this is important for determining the time period for responding

- Once all of these points have been verified, you can check this off your list and move on to the next step.

- Review the agreement to make sure that the assignment language is drafted correctly and is broad enough to encompass all of the rights and obligations being assigned

- Ensure that the parties are not trying to assign any rights or obligations that are not legally assignable

- Make sure that the agreement is clear regarding the liabilities of the parties, as they will be assumed by the assignee

- Confirm that the assumptions being made by the assignee are clearly laid out in the agreement

- Ensure that the agreement is not assigning any rights or obligations that may be subject to the consent of a third party

- When all potential issues have been addressed, the agreement can be signed by both parties.

- Understand that an Assignment and Assumption Agreement (A&A) will transfer some of the liabilities from one party to another in a business transaction

- Identify which liabilities are to be transferred in the A&A

- Clarify which liabilities will remain with the original party

- Establish a timeline for the transfer of liabilities

- Decide which party is responsible for liabilities that occur after the transfer

- Make sure that the liabilities are accurately defined and described in the A&A

You will know that you can check this step off your list and move on to the next step when all liabilities have been properly identified, defined and described in the A&A, and all parties have agreed to the timeline for the transfer of liabilities.

- Understand the basics of Representations & Warranties and what they mean in the context of assignment and assumption agreements

- Learn what should be included in Representations & Warranties and the consequences of not making accurate representations

- Research different types of Representations & Warranties, such as those related to title, capacity, authority, and performance

- Check that all Representations & Warranties included in the agreement are accurate and up-to-date

- Once all Representations & Warranties have been reviewed and confirmed to be accurate, you can check this step off your list and move on to the next step of the guide.

- Understand that disputes under an Assignment and Assumption Agreement are generally handled by the parties involved

- Understand the purpose of an arbitration clause in the agreement, which is to resolve disputes quickly, fairly, and affordably

- Determine if the agreement should include a mediation clause, which is less formal than arbitration and may be more suitable for some disputes

- Consider whether the agreement should include a choice of law clause, which will determine the governing law of the agreement

- Know that the agreement should specify the venue for any potential dispute resolution proceedings

- Understand that the parties may need to provide notice to the other party before initiating a dispute resolution procedure

- When you have a full understanding of how disputes will be handled under the Assignment and Assumption Agreement, you can check this step off your list and move on to the next step.

- Understand the importance of the contractual limitations outlined in the agreement

- Make sure all parties involved in the agreement have agreed to the contractual limitations

- Know that contractual limitations are meant to protect the parties involved in the agreement

- Be aware that contractual limitations may include time limits, scope of duties, and other stipulations

- When all parties involved have agreed to the contractual limitations, you have completed this step and can move on to the next step.

- Familiarize yourself with the applicable laws in the jurisdiction in which the assignment and assumption agreement will be executed

- Make sure to include language in the agreement that will address any issues that may arise due to a conflict of laws

- Ensure that the agreement properly identifies and describes the rights, obligations, and interests that are being assigned and assumed

- Identify any contingencies that could affect the transfer of rights and obligations, and include language that addresses such contingencies

- Consider adding any additional provisions that may be necessary to ensure the successful completion of the transaction

You can check this off your list and move on to the next step when you have addressed any issues that may arise due to a conflict of laws, properly identified and described the rights, obligations and interests that are being assigned and assumed, identified any contingencies that could affect the transfer of rights and obligations, and considered adding any additional provisions that may be necessary to ensure the successful completion of the transaction.

- Identify all contingent liabilities that must be assumed by the assignee, including any pending or potential claims and obligations

- Make sure the assignee is aware of, and willing to assume, the contingent liabilities

- Include language in the assignment and assumption agreement that outlines the assignee’s assumption of any contingent liabilities

- Check that the provisions in the agreement precisely identify the liabilities assumed by the assignee

- When all contingent liabilities have been identified and included in the agreement, you can move on to the next step of understanding applicable laws.

- Research applicable laws related to assignment and assumption agreements in your jurisdiction

- Understand the legal language and key elements of an assignment and assumption agreement

- Understand the process for filing and registering an assignment and assumption agreement

- Know what documents and information may be required to complete the registration process

- Understand the timeline for completion of the registration process

- Once you have a good understanding of the applicable laws and the process for registration, you can move on to the next step of identifying any contingent liabilities.

- Research the applicable law, and use language that is consistent with the requirements

- Draft a clear and concise agreement that covers all relevant topics

- Ensure that the language used is precise and unambiguous

- Define any legal terms used in the agreement

- Make sure that the agreement is in writing and all parties have signed it

- Review the agreement and make sure it is legally compliant

- When all of the above steps are completed, you can move on to the next step in the guide.

- Research applicable laws and regulations that may apply to the assignment and assumption agreement

- Obtain any necessary licenses or permits, such as a real estate license

- Ensure that all parties understand the regulations that apply to the agreement

- Determine if any state or federal laws need to be adhered to

- When all applicable laws and regulations have been taken into account and complied with, you can move on to the next step.

- Understand the potential advantages of using an Assignment and Assumption Agreement, including:

- Transferring existing contractual obligations and liabilities from one party to another

- Ensuring continuity in contractual agreements between parties

- Avoiding the need for a new contract

- When you have a solid understanding of the potential benefits of using an Assignment and Assumption Agreement, you can check off this step and move on to the next one, which is Risk Reduction.

- Identify the potential risks that are associated with an assignment and assumption agreement

- Analyze how the assignment and assumption agreement may reduce those risks

- Understand the legalities that would protect both parties in the agreement

- Be aware of the potential regulatory requirements that may apply

- When you have thoroughly assessed the risks and understand how an assignment and assumption agreement can protect both parties, you are ready to move on to the next step.

- Understand the definition of an assignment and an assumption agreement

- Learn the differences between the two agreements

- Familiarize yourself with the processes and procedures of an assignment and assumption agreement

- Understand the legal implications of an assignment and an assumption agreement

- Familiarize yourself with the potential benefits of an assignment and assumption agreement

- Understand how an assignment and assumption agreement can be used to protect assets

You’ll know you can check this off your list and move on to the next step when you have a good grasp of the processes and procedures associated with an assignment and assumption agreement, the legal implications of such an agreement, and the potential benefits of using one.

- Understand the different costs associated with the transfer of assets, such as attorney’s fees, recording fees, and transfer taxes

- Consider the potential cost savings of using an assignment and assumption agreement as opposed to other methods of transferring assets

- Determine the effect of the transfer on the financial statements of both parties

- Review the agreement to ensure all costs are accounted for

When you have a thorough understanding of the cost savings to be made and have reviewed the agreement to ensure all costs are accounted for, you can move on to the next step.

- Be aware of the potential conflicts of interest between the assignor and assignee when an Assignment and Assumption Agreement is used

- Consider applicable laws, regulations and contractual restrictions when determining if an Assignment and Assumption Agreement is the best option

- Understand that if an Assignment and Assumption Agreement is used, both the assignor and assignee will remain liable for any existing obligations

- Be aware that the assignee may not have the same rights as the assignor under the agreement and may not have direct access to the original contract

- Understand that the assignee may be liable for any damages or losses caused by the assignor’s breach of the agreement

You’ll know when you can check this off your list and move on to the next step when you have a good understanding of the potential pitfalls and responsibilities associated with using an Assignment and Assumption Agreement.

- Understand that when assuming liabilities, there are certain risks that may be unforeseen and difficult to calculate

- Be aware that the assignor of the agreement can still be held liable if any unanticipated risks arise

- Carefully review the agreement to ensure that the assignor and the assignee are both protected from unforeseen risks

- Discuss any potential risks with legal counsel to ensure that all parties understand the potential risks

- Have all parties sign the agreement to ensure that everyone is aware of the risks and agrees to them

- When all parties have signed, the agreement can be considered complete and all parties can move forward with the transfer of liabilities

- Understand the differences between the two parties and their respective interests

- Identify the areas where both parties can agree on specific terms and conditions

- Determine which party will be liable for any breaches of the agreement

- Negotiate a fair deal that both parties can agree to

- Consider any legal, financial, and tax implications for both parties

- Once negotiations are complete, have the parties sign the agreement

- Make sure that both parties understand the terms and conditions of the agreement

- Verify that both parties are in agreement and that all negotiations are complete

- Check that all the required legal documents are present and in order

- Check that all parties involved are aware of their respective responsibilities

You’ll know when you can check this off your list and move on to the next step when all parties have agreed to the terms and conditions of the agreement, all required legal documents have been provided and in order, and all parties have signed the agreement.

- Research the laws and regulations that apply to the transaction, including state and local statutes, to assess potential risks

- Check for any filing requirements or permits that need to be obtained

- Identify any restrictions that could occur due to the parties involved

- Document any potential regulatory non-compliance issues

- When all potential risks have been identified and documented, you can move on to the next step.

- Review the terms and conditions of the agreement, as well as any applicable regulations, to ensure that all parties have a clear understanding of the agreement as a whole.

- Seek legal counsel if there are any questions or concerns about the agreement.

- Finalize the agreement by signing and exchanging documents.

- After the agreement has been finalized, it will be legally binding and enforceable.

- Make sure all parties are aware of their responsibilities and obligations under the agreement.

- Monitor the agreement to ensure that all parties are complying with the terms and conditions of the agreement.

- Check off this step when the agreement has been finalized and all parties have signed and exchanged documents.

- Review the agreement carefully and make sure all parties have signed off

- Make sure all parties have received a copy of the agreement

- Ensure that all parties have received the agreed-upon consideration

- File the original agreement with all relevant documents with the appropriate government agency or court

- You will know that you have finished this step when all parties have signed the agreement, all parties have received a copy, and the original agreement has been filed with the appropriate government agency or court.

- Execute the agreement, making sure both parties have signed it and that all parties involved have read, understood, and accepted the terms and conditions of the agreement.

- Make sure that the agreement has been filed with the appropriate state or federal agency, if required.

- Start the process of transferring assets and obligations from the assignor to the assignee, as outlined in the agreement.

- Make sure that all parties have the necessary information to complete the assignment and assumption. This may include but is not limited to: legal documents, financial documents, contracts, and other pertinent information.

- Ensure that all parties have received the necessary payment for the assignment and assumption.

- Check that all parties have complied with the terms and conditions of the agreement.

- You can check this off your list once you have completed all the steps necessary for the successful implementation of the agreement.