Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

5 Tips for Building and Managing Research Teams

As one moves up higher on the academic ladder, it is inevitable that their responsibilities keep changing shape. At some point, every researcher grows from being a timid graduate student fumbling around in the lab to learning how to manage a research team of their own at an academic institution or at a research organization. The excitement of this new role might be accompanied with some anxiety regarding the challenges that one might face while figuring out how to build a research team and forming an effective research team structure. Team work in research is essential and any issue in the team reflects in the work. So, if you have ever wondered how to lead a research team and you are looking for avenues that can improve your managerial skills, this article can help you get started.

1. Identify the right people for your research team

When you think about the question how to build a research team, the first step is to choose the right people for the team. As an efficient team leader/manager, one of the primary responsibilities is building a research team and establishing a research team structure that can help you achieve the goals envisioned by your lab or institute. The first step toward this is identifying people that can not only perform delegated tasks effectively, but can also adapt smoothly to the culture of your institute. If you are leading a heterogeneous research team of technicians, interns, graduate students, and postdocs, it is important to consider their individual calibre and time availability while assigning specific roles. The question of how to manage a research team will become simpler to answer once you have gauged your teammates’ capabilities.

2. Utilize the strengths of individual research team members

Managing research teams goes beyond just ‘managing’. The key to becoming a good team manager is developing a thorough understanding of the core characteristics of individual members of the research team. Building one-on-one relationships with team members can help you understand them better and help them achieve their most optimal performance. Some individuals perform well under pressure and stringent deadlines, while others perform better at their own pace. Similarly, some members thrive in a competitive environment, while others in the research team prefer a collaborative environment. The more extroverted members of your research team might be better at handling people-oriented tasks, while introverted ones work better in solitude. Identifying each individual member’s core strengths will help you delegate tasks more efficiently and build a better research team structure, which will in turn lead to better performance and research team work.

3. Invest in mentoring and skill-building within your research team

The best tip for how to lead a research team is to prioritize your team’s growth. A good manager thrives the most when he/she engages in mentoring and capacity building of the research team. Motivating team members to pursue skill building, will help in building and managing a research team that is robust and confident. Investing time in understanding their individual long-term goals and providing them with useful guidance from time-to-time can help develop trust with each team member. As a result, you get a strong research team structure too since each member’s core strengths are further refined. It is also essential for a research team manager to establish a team culture that facilitates good research practices and fosters an attitude of integrity.

4. Keep the communication channels open with your research team

Lack of availability of the manager can directly translate to poor performance of the research team. To learn how to manage a research team, it is important to first consider whether your team is heterogeneous in nature – the younger and more inexperienced members will require your continued guidance and support. It is necessary to be open to feedback on how you can support the team better. This will help build the team’s trust and confidence in you. Hosting frequent lab meetings, albeit of short durations, to discuss urgent and pertinent issues can be one way to ensure that the communication channels remain active. Encouraging open communication can also be extremely helpful in identifying signs of conflict among team members and address the situation effectively.

5. Foster a collaborative attitude and celebrate the small wins

Appreciate the time, energy, and effort dedicated by each research team member, regardless of the outcome of their work. In academia, each failed experiment can be used to enhance the individual learning curve, and allowing research team members to grow through their mistakes will help in boosting their self-confidence. Academicians invariably end up harboring a competitive spirit, since the system is designed to reward individual performances more than collective research team work. This can have deleterious effects on individual well-being as well as projects involving multiple people. Fostering a collaborative attitude, organizing team-building activities, and creating a safe and inclusive environment for researchers from all backgrounds and with diverse viewpoints will help in the improved well-being of your research team.

Do you know the best thing about having a research team? Work on your plate gets divided. And that’s why, developing an empathetic attitude toward your team members is extremely essential. It is wise to acknowledge the fact that you have a limited control over their performance and can only motivate them to a certain extent. Thus, it is necessary to develop an adaptable mind that can readily accept modifications in the previously envisioned goals and strategies to ensure effective team work in research teams.

Additional reading:

- Five ‘power skills’ for becoming a team leader. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00178-2.

- How to lead a research team | Careers | Chemistry World. https://www.chemistryworld.com/careers/how-to-lead-a-research-team/4011327.article.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

Research Paper Appendix: Format and Examples

Skip to content. | Skip to navigation

Personal tools

- Log in/Register Register

https://www.vitae.ac.uk/doing-research/leadership-development-for-principal-investigators-pis/building-and-managing-a-research-team/building-and-managing-a-research-team

This page has been reproduced from the Vitae website (www.vitae.ac.uk). Vitae is dedicated to realising the potential of researchers through transforming their professional and career development.

- Vitae members' area

Building and managing a research team

Building your team, what is a research team.

What constitutes a research team in one department or institution might be described elsewhere as a research group, research centre, research unit or research institute. Regardless of the terminology used, the key characteristic of a research team is that it comprises a group of people working together in a committed way towards a common research goal.

Research team diversity

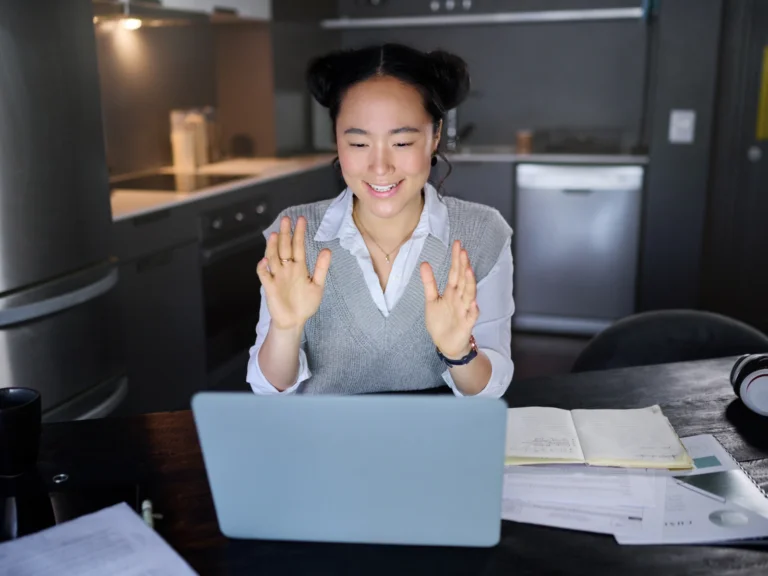

There are many different configurations of research teams in academia and boundaries can be 'fuzzy'. They may comprise co-investigators, fractional or pooled staff, technical and clerical staff and postgraduate research students. There may also be inter- and intra-institutional dimensions and increasingly international ones; some team members' contributions may well be largely virtual, via email, phone or videoconference.

Also, team members may have different disciplinary backgrounds, different motivations and aspirations, and different cultural backgrounds. Over time, team members' roles may change from being core (fully dedicated to the research goal) to peripheral (committed to this research goal, but also working in one or more other teams), and vice-versa.

Assessing the balance and composition of your team.

Ideally, the balance and composition of the team in terms of skills, expertise and other contributions will be appropriate to achieve the team's objectives, i.e. for the research goal the team is working towards. The research team leader needs to be confident that team members have, or can develop, the necessary skills and knowledge for the research in hand, and you will make recruitment decisions on that basis.

There is also another perspective on the effective team which it is good to consider. In addition to knowledge, experience and skills individuals have different behavioural traits or characteristics they bring to the way they carry out their work and these can be aligned to particular roles in the team: some are very good at seeing a big picture, others very good at detailed work. Some are very oriented towards action - good at just getting things done; others are natural communicators and networkers. The need for these different roles will emerge at different times and it is worth considering the composition of your team to ensure you have a balance of strengths.

To find out more about specific team roles and the research by Meredith Belbin on which they are based, see the section further down this page.

Managing your team

Your responsibilities as a manager of the group.

These are the responsibilities identified in Adair's action-centred leadership model :

- establish, agree and communicate standards of performance and behaviour

- establish style, culture, approach of the group - soft skill elements

- monitor and maintain discipline, ethics, integrity and focus on objectives

- anticipate and resolve group conflict, struggles or disagreements

- assess and change as necessary the balance and composition of the group

- develop team-working, cooperation, morale and team-spirit

- develop the collective maturity and capability of the group - progressively increase group freedom and authority

- encourage the team towards objectives and aims - motivate the group and provide a collective sense of purpose

- identify, develop and agree team- and project-leadership roles within group

- enable, facilitate and ensure effective internal and external group communications

- identify and meet group training needs

- give feedback to the group on overall progress; consult with, and seek feedback and input from the group.

| Looking at the list of responsibilities above, which are the areas where you feel confident in your abilities? Which are the areas where you feel less confident, or might benefit from some support or development? Most people will lack confidence in some areas of their people management skills. Look at the section on for ideas and advice, talk to a more experienced colleague or ask your head of department to arrange some mentoring. |

Team roles and development

A research team consists of people working together in a committed way towards a common research goal. Teams, like individuals and organisations mature and develop and have a fairly clearly defined growth cycle. Bruce Tuckman's 1965 four-stage model explains this cycle. It may be helpful to reflect on your team's current stage of development in order to identify relevant approaches to leadership and management. In addition to understanding the development of your team over time, having an understanding of the preferred ‘team roles', the characteristics and expected social behaviour, of individual team members, including the team leader, will help ensure that the team performs effectively together. Using team role or individual profiling tools can offer insights into building and maintaining an effective team, but team role analysis is most useful if all members evaluate their own and others' preferred roles, whichever tools are chosen.

There are a number of team role and individual profile tools available and your institution's staff development department or equivalent may have registered practitioners in one or more of these who can help you and your team understand your preferred team roles or working styles.

In the 1970s, Meredith Belbin and colleagues at the Henley Management College identified nine team roles, based on long-term psychometric tests and studies of business teams. Belbin defined team roles as "a tendency to behave, contribute and interrelate with others in a particular way". The resulting role definitions fall into three categories, each with strengths and allowable weaknesses, and have been used widely in practice for team development in the intervening decades. Further research by Belbin has led to the addition of a tenth ‘Specialist' role in recent years. Watch this short introduction to the work of Belbin , or read about the team roles.

| Read through Belbin's team role definitions - what functions might each of Belbin's team roles play in a research team context? Are there any other team roles in a research context? Are there any of Belbin's roles that play little part in a research team? | |

| Think about your own research team: compare each member's strengths and weaknesses (including yourself).

|

Bookmark & Share

Manage My Research Team

Categories:

- Award Management

- Regulatory Compliance

There are many ways to go about building a research team—some more effective than others. If you are charged with or are interested in building a research team, there are several considerations to keep in mind:

Bring together members with diverse backgrounds and experiences to promote mutual learning.

Make sure each person understands his or her roles, responsibilities, and contributions to the team’s goals.

As a leader, establish expectations for working together; as a participant, understand your contribution to the end goal.

Recognize that discussing team goals openly and honestly will be a dynamic process and will evolve over time.

Be prepared for disagreements and even conflicts, especially in the early stages of team formation.

Agree on processes for sharing data, establishing and sharing credit, and managing authorship immediately and over the course of the project.

Regularly consider new scientific perspectives and ideas related to the research.

Source: Collaboration and Team Science: A Field Guide

The Field Guide discusses:

Team Science

Preparing Yourself for Team Science

Building a Research Team

Fostering Trust

Developing a Shared Vision

Communicating About Science

Sharing Recognition and Credit

Handling Conflict

Strengthening Team Dynamics

Navigating and Leveraging Networks and Systems

Created: 11.27.2020

Updated: 04.12.2021

Cultivating an Effective Research Team Through Application of Team Science Principles

Shirley L.T. Helm, MS, CCRP Senior Administrator for Network Capacity & Workforce Strategies

C. Kenneth & Dianne Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research

Virginia Commonwealth University

Abstract: The practice of team science allows clinical research professionals to draw from theory-driven principles to build an effective and efficient research team. Inherent in these principles are recognizing team member differences and welcoming diversity in an effort to integrate knowledge to solve complex problems. This article describes the basics of team science and how it can be applied to creating a highly-productive research team across the study continuum, including research administrators, budget developers, investigators, and research coordinators. The development of mutual trust, a shared vision, and open communication are crucial elements of a successful research team and research project. A case study illustrates the team science approach.

Introduction

Each research team is a community that requires trust, understanding, listening, and engagement. Stokols, Hall, Taylor, Moser, & Syme said that:

“There are many types of research teams, each one as dynamic as its team members. Research teams may comprise investigators from the same or different fields. Research teams also vary by size, organizational complexity, and geographic scope, ranging from as few as two individuals working together to a vast network of interdependent researchers across many institutions. Research teams have diverse goals spanning scientific discovery, training, clinical translation, public health, and health policy.” 1 1 Stokols D, Hall KL, Taylor BK, Moser RP. The science of team science: overview of the field and introduction to the supplement. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S77-89. Accessed 8/10/20.

Team science arose from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, which fund the work of researchers attempting to solve some of the most complex problems that require a multi-disciplinary approach, such as childhood obesity. 2 Team science is bringing in elements from various disciplines to solve these major problems. 3, 4 This article covers the intersection of team science with effective operationalizing of research teams and how teaming principles can be applied to the functioning of research teams.

Salas and colleagues state that, “a team consists of two or more individuals, who have specific roles, perform interdependent tasks, are adaptable, and share a common goal. . . team members must possess individual and team Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes ….” 5 Great teams have a plan for how people act and work together. There are three elements that must be aligned to ensure success: the individual, the team, and the task. Individuals have their own goals. These goals must align, and not compete with, goals of other individuals and team goals. Task goals are the nuts and bolts of clinical research. Like individuals, the team has an identity. It is necessary to provide feedback both as a team and as individuals.

In a typical clinical research team, the clinical investigator is at the center surrounded by the clinical research coordinators. The coordinator is the person who makes the team function. Other members of the typical clinical research team are:

· Research participant/family

· Financial/administrative staff

· Regulatory body (institutional review board)

· Study staff

· Ancillary services such as radiology or pathology

· Sponsor/monitor.

The Teaming Principles

Bruce Tuckman developed the teaming principles in 1965 and revised them in 1977 (Table 1). 6 Using the teaming principles is not a linear process. These principles start with establishing the team. The team leader does not have to establish the team. Any team member can use teaming principles to provide a framework and structure and systematically determine what the project needs. Storming is establishing roles and responsibilities, communications, and processes. The storming phase, when everybody has been brought together and is on board with the same goal, is a honeymoon period.

Norming is the heavy lifting of the team’s work. This involves working together effectively and efficiently. Team members must develop trust and comfort with each other. Performing focuses on working together efficiently, and satisfaction for team members and the research participants and their families.

Tuckman added adjourning or transforming to the teaming principles in 1977. The team might end or start working on a new project (study) with a new shared goal. Adjourning or transforming involves determining which processes can be transferred from one research study to another research study.

While the teaming principles seem intuitive and like common sense, people are not raised to be fully cooperative. Using the teaming principles provides framework and structure and takes the emotion out of teamwork. The teaming principles empower team members and provide the structure that is necessary for teams, which are constantly evolving and changing.

The shared goal at the center of the teaming principles provides a sense of purpose. This provides commitment, responsibility, and accountability, along with a clear understanding of roles, responsibilities, competencies, expectations, and contributions. In Dare to lead: Brave work. Tough conversations. Whole hearts, Brené Brown coined the phrase, “clear is kind, unclear is unkind.” 7 It is extremely important to define roles and ensure that each team member knows what the other team members are doing. This prevents duplication of effort and ensures that tasks do not fall through the cracks.

How to Use Teaming Principles

Table 2 briefly describes each of the five teaming principles. Forming begins with gathering the team members and involves determining who is needed on the team to ensure success. Each team member must be valued. The team may vary depending upon the study, project, and timelines. During the research study, team members may enter and exit from the team. Forming the team may mean working across boundaries with people and departments that team members do not know. It is also necessary to establish the required competencies and knowledge, skills, and attitudes of team members, and to recognize and celebrate differences. The team must have a shared goal and vision.

Storming the team involves establishing roles, responsibilities, and tasks. This includes determining who has the required competencies to perform tasks such as completing pre-screening logs or consenting research participants. Also, storming involves defining processes, including communication pathways and expectations. Simply sending an email is not an effective way to communicate. Team members need to know whether an email is providing information or requires a response. Expectations for responding to emails should be described and agreed upon by all team members. Emails might be color coded to show whether an email is informational or requires a response. If clinical research sites utilize a clinical trial management system, the process for updating it must be determined and clearly communicated.

Norming is how team members work together. The shared goal is re-visited often under norming. Team members are mutually dependent upon each other and must meet their commitments and established deadlines.

Trust lies at the heart of the team. Building trust takes work and does not come naturally. It is helpful to understand that there are several types of trust. Identity-based trust is based on personal understanding and is usually seen in relationships between partners, spouses, siblings, or best friends. This type of trust does not usually occur in the workplace.

Workplace trust resides in calculus-based trust and competence-based trust. Calculus-based trust is about keeping commitments, meeting deadlines, and meeting expectations. There are some people who can be counted upon to always do what they are supposed to do. These people have earned calculus-based trust. Competence-based trust is confidence in another person’s skills or competencies.

Swift trust is immediate and necessary during extreme situations where there is not time to develop deeper connections with individuals. It relies on personal experiences, stereotypes, and biases. Some people are naturally more trusting than other people.

The teaming principle of performing involves satisfaction in progressing toward the goal and being proactive in preventing issues from arising. There will always be issues; however, the most effective teams learn from issues and have processes for resolving them. This makes a team efficient. Performing also includes revisiting the shared goal, embracing diversity and differences, and continually improving knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

Adjourning/transforming is the completion of tasks and identification of lessons learned. Team members need to circle back and determine what worked well and can be applied to the next study. Celebrating successes and acknowledging the contributions of all team members are also an aspect of adjourning/transforming. When the author was managing a core laboratory, she performed tests for an oncology investigator’s study. Months later, the investigator gave her a thank-you card for her contribution to the study that was unexpected but greatly appreciated.

Strengthening the Team

Without a framework and structure, team dysfunction is likely. In The five dysfunctions of a team: A leadership fable , Lencioni presented team dysfunction as a pyramid. 8 Absence of trust is at the bottom of the pyramid. Absence of trust results in questioning everything people do and results in team members unwilling to share or to ask for help. Without asking for help, mistakes will be made.

Absence of trust leads to a fear of conflict and an inability to resolve issues or improve efficiencies. Fear of conflict leads to lack of commitment. Doubt prevails, team members lack confidence, and the goal is diminished. Team dysfunction leads to avoidance of accountability. Follow-through is poor and mediocrity is accepted, breeding resentment among team members.

At the top of the team dysfunction pyramid is inattention to results, which leads to loss of team members and future research studies. There are some teams where people are constantly moving in and out. This is

a symptom of team dysfunction. Loss of respect and reputation of the team, department, and individual team members is another consequence of inattention to results.

Table 3 highlights ways to strengthen the team. Recognizing the strengths of each team member starts with self-awareness. For example, the author had to understand her communication and learning style and how this is similar to and different than that of other team members. The VIA Institute of Character offers a free assessment that could be a fun activity for research teams.

There is no one road to self-awareness; however, each team member must recognize that other team members do not necessarily share their understanding or perceptions. There are many options and possibilities for how others may understand or perceive an experience, none of which are right or wrong. Each team member should appreciate that different understanding and perceptions of experiences do not have to threaten their identity or relationships.

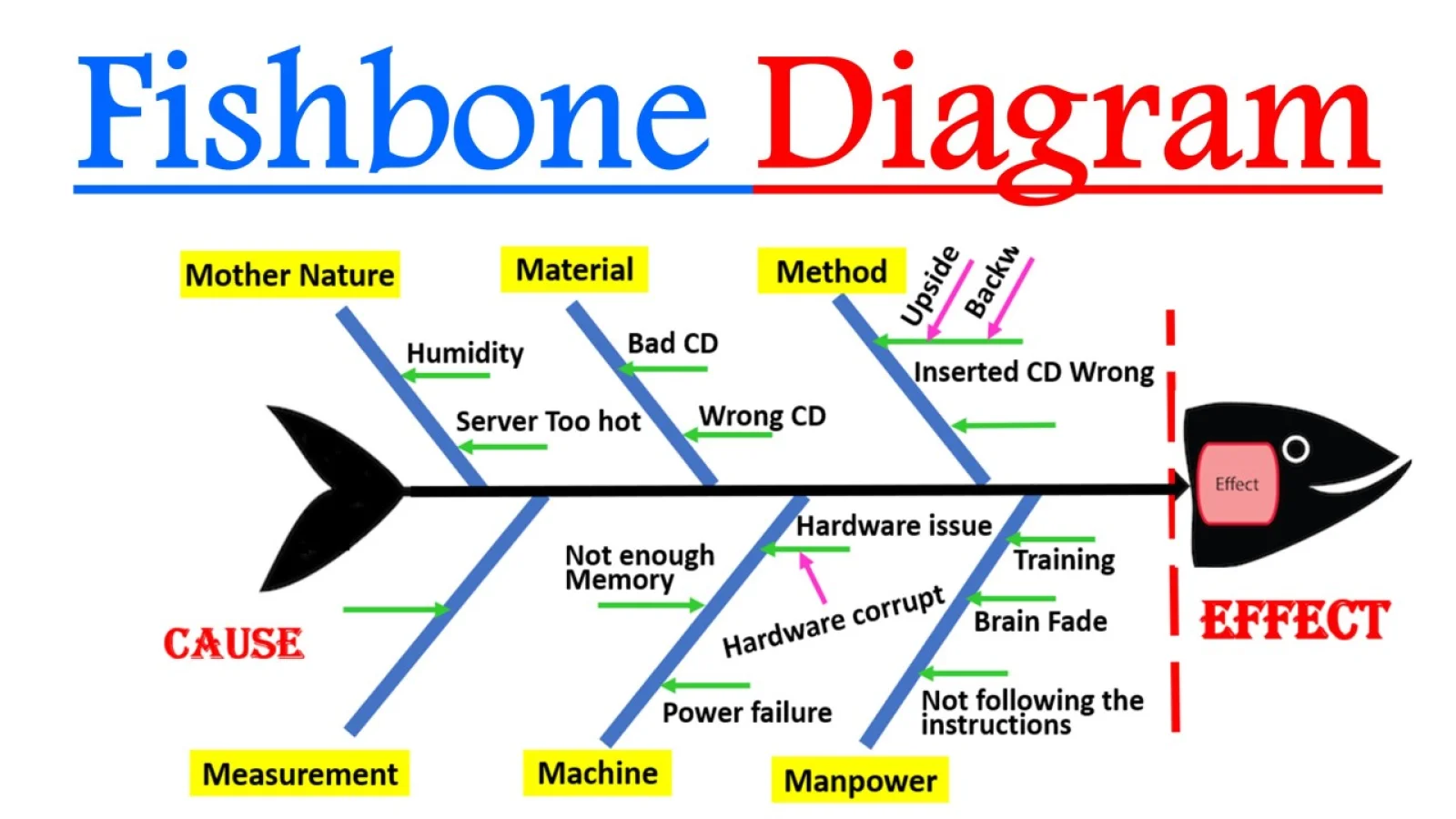

One quick way to show this is through ambiguous images, in which people see entirely different things in the same image. Once they are aware that there are different ways of seeing the same thing, they can appreciate other perspectives. As Pablo Picasso said, “There is only one way to see things, until someone shows us how to look at them with different eyes.” Strengthening the team requires embracing demographic, educational, and personality diversity.

Open and honest communication should be encouraged. Team members should give and receive constructive feedback. This is a learned skill that is often difficult. However, tools are available for assessing communication and listening styles. Many institutions and human resource departments utilize the Crucial Conversations program by VitalSmarts, LC. One member of the team can participate in Crucial Conversations and bring the knowledge back to the team. Communication must include managing conflict and an awareness of cultural differences.

Opportunities for education and training to acquire new knowledge, skills, and attitudes/competencies should be provided. Education may be transportable across teams or may be study specific. Team members should be cross-trained, which may be accomplished through several methods. Positional clarification is where one person is told what another person is doing, which is primarily for information transfer. Positional modeling is receiving the information but also shadowing the other person while they perform the task/skill. Positional rotation is performing another person’s job. This is best for back-up positions, which are necessary for research teams.

Team success is facilitated by recognizing individual successes and commitment to shared goals. Recognizing individual successes reflects team success. For example, if a team member becomes a certified clinical research professional, this is a success for both the individual and the team. Also, the team must have a shared understanding of the goal or purpose. This shared goal must be linked to the individual goal of each team member.

Teamwork needs constant attention and annual evaluations, and team meetings are not sufficient. It is extremely important to regularly check in with people. Team members can check in with other team members simply to ask how things are going. Misunderstandings should be dealt with immediately. Clear direction, accountability, and rewards are necessary.

The author has a bell on her desk that team members ring when they have a success. This sounds cheesy, however, it is fun and team members really enjoy it. For example, when the author finished her slides for the SOCRA annual conference on time, she rang the bell. Her team members asked what happened, and they had a mini celebration. This small item helps to build and strengthen a team with small successes leading to larger successes.

Case Study Using the Teaming Principles

The following case study illustrates the application of the teaming principles to a team involving four major players. Olivia is a clinician with three clinic days and teaching duties who is a sought-after speaker for international conferences. In addition, Olivia is the clinical investigator for four clinical research studies: two studies are active, one is in long-term follow up, and one is in closeout. The studies are a blend of industry sponsored and investigator initiated. Olivia is also a co-clinical investigator on two additional studies and relies heavily upon Ansh for coordination of all studies and management of two research assistants.

Ansh is the lead research coordinator with seven years of experience in critical care research. Ansh is very detail-oriented and takes pride in error-free case report forms, coordinates with external monitors, and manages two research assistants as well as the day-to-day operations of Olivia’s research studies.

Bernita is a research assistant with six months of work experience in obtaining informed consents, scheduling study visits, and coordinating with ancillary services. Bernita is responsible for contacting participants for scheduled visits and providing participant payments. Bernita is developing coordinating skills, seeks out training and educational opportunities, and is a real people person.

Delroy is the regulatory affairs specialist for the Critical Care Department, which consists of eight clinicians (not all of whom are engaged in research). Studies include one multi-site clinical trial for which the clinical research site is the coordinating site, and one faculty-held Investigational New Drug/Investigational Device Exemption study. The department’s studies are a mixture of federal- and industry-funded studies. Delroy has been with the department for five years in this capacity. However, Delroy’s coworker recently and unexpectedly took family and medical leave, leaving Delroy to manage all regulatory issues for the department. Also, the department chair recently made growing the department’s industry-sponsored study portfolio a priority.

Olivia has received an invitation to be added as a clinical research site for a highly sought-after ongoing Phase II, multisite, industry-sponsored study comparing two asthma medications in an adult outpatient setting. The study uses a central institutional review board (IRB) and has competitive enrollment. It will require the following ancillary services: investigational pharmacy, radiology, and outpatient asthma clinic nursing. For the purposes of this case study, all contracts have been negotiated and all of the regulatory documents are available (e.g., FDA Form 1572, informed consent template, and the current protocol). The institution utilizes a clinical trial management system.

Oliva shares the study information and study enrollment goals with Ansh with the charge of getting this study activated and enrolling within 40 days. What are the potential barriers that might affect this outcome? One potential barrier to the study activation timeline is Delroy’s heavy workload. To ensure that the timeline is met, Ansh might contact Delroy and explain the situation, asking what Ansh can do to help facilitate study start-up to ensure that the timeline is met. Ansh should be clear in determining what Delroy needs for study activation, the deadlines for each item, and assist in facilitation of communicating to other members of the study activation team (e.g., ancillary services, IRB) what is needed. Priorities include the regulatory work and staff training. Barriers include managing the regulatory issues on time. This might be a good opportunity to connect with Bernita for providing Delroy some assistance, as Bernita is knowledgeable and eager to acquire additional skills and training. The shared goal of starting the study on time should be shared with all team members in order to meet the 40 day study activation and enrollment goal.

Nuggets for Success as a Team Member or Leader

Members of a research team must know the other team members and available resources. They need to know who is needed for a particular study. This will change during studies and across studies. Roles and responsibilities among the broader team should be identified.

Table 4 outlines nuggets of success as a team member or leader, starting with using the framework of the teaming principles. Next, the team member or leader should build and create networks for knowledge and access. A knowledge network enables team members to know who to contact to provide an answer to specific questions. Each team member is a knowledge network for someone else. Also, each team member should find a person who they admire to serve as a mentor, even informally.

Team members should take advantage of available training. LinkedIn has many free training programs, and the institution’s human resources department also offers training. Meeting times should be scheduled to set aside time for reflection. Team members should check in often with the team as a whole and individual team members, set realistic boundaries, and establish priorities. Team members should avoid making assumptions, and instead, communicate clearly and often. Other keys to team success are to be respectful and present, participate, and practice humanity.

This work was supported by CTSA award No. UL1TR002649 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Overview of the Teaming Principles

- Establish team (top-down and bottom-up)

- Establish roles and responsibilities, communications, and processes

- Working together effectively and efficiently

- Individuals develop trust and comfort

- Work together efficiently

- Focus on a shared vision

- Resolves issues

- Natural end:dissolution

- New project (study) with a new shared goal

Description of the Teaming Principles

- Team members may vary depending upon the study, project, and timelines

- Work across boundaries

- Appropriate competencies and knowledge, skills, and attitudes

- Recognize and celebrate differences

- Shared goal and vision

- Determining who has the competencies for specific study tasks

- Communication pathways and expectation

- Completing clinical trial management systems updates

- Revisit the shared goal often

- Requires mutual dependence

- Identity-based: personal understanding

- Calculus-based: keep commitments, meet deadlines, meet expectations

- Competence-based: confidence in skills, competencies of another

- Satisfaction in progressing toward goal

- Proactive in preventing issues from arising

- Revisit the shared goal

- Embrace diversity and differences

- Continuous improvement in knowledge, skills, and attitudes

- Completion of tasks

- Identify lessons learned

- Celebrate success and acknowledge the contributions of all

- Self-awareness and assessments

- Demographic

- Educational

- Personality

- Give and receive constructive feedback

- Acquire new knowledge, skills, and attitudes/competencies

- Cross-train

- Recognize individual success, which reflects team success

- Commit to shared goals

Nuggets of Success as a Team Member of Leader

- Use the teaming principles as a framework

- Build and create networks for knowledge and access

- Find a mentor

- Take advantage of training

- Schedule meeting times for reflection

- Check in with the team and team members

- Set boundaries and priorities

- Never make assumptions

- Be respectful and present

- Participate

- Practice humanity

1 Stokols D, Hall KL, Taylor BK, Moser RP. The science of team science: overview of the field and introduction to the supplement. Am J Prev Med. 2008 Aug;35(2 Suppl):S77-89. Accessed 8/10/20.

2 Bennett LM, Gadlin H, Marchand C. Team Collaboration Field Guide. Publication No. 18-7660, 2nd ed., National Institutes of Health; 2018. Accessed 8/10/20.

3 National Research Council. Enhancing the Effectiveness of Team Science. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. Accessed 8/10/20.

4 Teambuilding 1: How to build effective teams in healthcare. Nursing Times. Accessed 8/10/20.

5 Salas E, Dickinson TL, Converse SA. Toward an Understanding of Team Performance and Training. In: Swezey R W, Salas E, editors. Teams: Their Training and Performance. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1992. pp. 3–29.

6 Tuckman, BW, Jensen MA. Stages of small-group development revisited. Group and Organization Studies, 2. 1977: 419-427.

7 Brown B. Dare to lead: Brave work. Tough conversations. Whole hearts. New York: Random House, 2018.

8 Lencioni P. The five dysfunctions of a team: A leadership fable. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass: 2002.

One thought on “Cultivating an Effective Research Team Through Application of Team Science Principles”

Hey there! I just finished reading your article on cultivating an effective research team through the application of team science principles, and I couldn’t help but drop a comment. First off, kudos to you for sharing such valuable insights. Your article was not only informative but also highly engaging, making it a pleasure to read.

I particularly resonated with your emphasis on the importance of clear communication and collaboration within research teams. It’s incredible how these seemingly simple principles can make such a significant difference in the success of a research project. Your practical tips on fostering trust and encouraging diversity of thought were spot-on. I’ve had my fair share of experiences in research teams, and I can attest that when everyone is on the same page and feels heard, the results are remarkable. Your article has given me a fresh perspective on how to approach team dynamics in my future research endeavors, and I’ll definitely be sharing these insights with my colleagues. Thanks again for sharing your wisdom! Looking forward to more of your articles in the future.

Keep up the fantastic work, and please continue to share your expertise. Your writing style is not only informative but also very relatable, making complex topics like team science principles easy to grasp. I’ll be eagerly awaiting your next piece. Until then, wishing you all the best in your research and writing endeavors! 😊📚

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

33RD ANNUAL CONFERENCE

ACHIEVING EXCELLENCE IN CLINICAL RESEARCH :

FORGING STRATEGIC COLLABORATIONS

September 27 to 29

COUNTDOWN TO ANNUAL CONFERENCE

Join us for expert-led sessions, interactive workshops, a peer-driven poster program, an engaging exhibit program and unparalleled networking opportunities!

It looks like your browser is incompatible with our website.

If you are currently using IE 11 or earlier, we recommend you update to the new Microsoft Edge or visit our site on another supported browser.

OUR SYSTEMATIC REVIEW ENGINE IS COMING OCTOBER 13 th For Confident Regulatory Decision Making Join the Waitlist

- For Corporate

- For Individual

- For Academic

- Article Galaxy Browser Extension

- Reference Management

- Technology Landscape

- Clinical Trial Landscape

- Article Galaxy Widget

- Applied BioMath

- Boehringer Ingelheim

- Product Information

- Research and Reports

- Press Releases

- Release Notes

- Knowledge Base

- ROI Calculator

- Research Solutions

The Article Galaxy Blog

- BioTech/Pharma

Four Effective Strategies to Empower Your Research Team

Efficiently managing and tracking scientific content and sources can be a real challenge for researchers, especially when working together on projects.

As teams grow and projects become more complex and intricate, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed trying to keep everything organized and maintain a centralized literature repository. This is why finding effective solutions and strategies for managing sources is so important in research.

As researchers contend with these obstacles, tools like Article Galaxy References emerge as transformative solutions that effectively address collaboration pain points throughout the research process. Beyond benefitting individual researchers, References fosters teamwork and productivity by centralizing sources and streamlining workflows to facilitates seamless collaboration among teams, propelling innovative power.

Below, we delve into four effective strategies that research leaders can employ to enhance research outcomes and enhance team experiences. These insights provide practical solutions to elevate the quality of your research and drive progress in your projects.

1. Leverage advanced collaborative tools to improve communication and team workflows.

Collaboration lies at the heart of successful research teams, enabling the blending of diverse skills, knowledge, and perspectives. When researchers from different backgrounds and with varying skill sets come together, it creates an environment poised for true innovation and creativity.

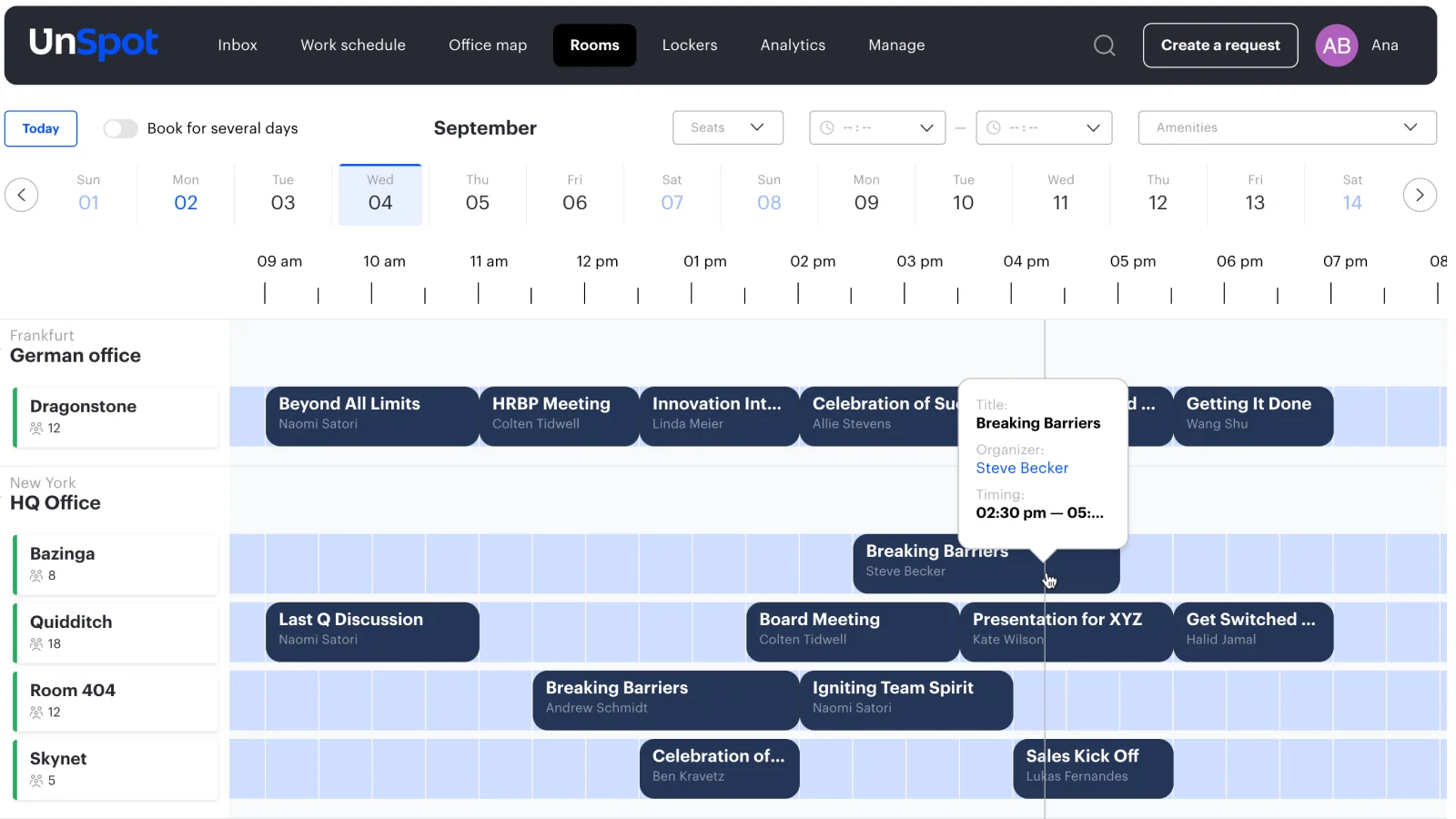

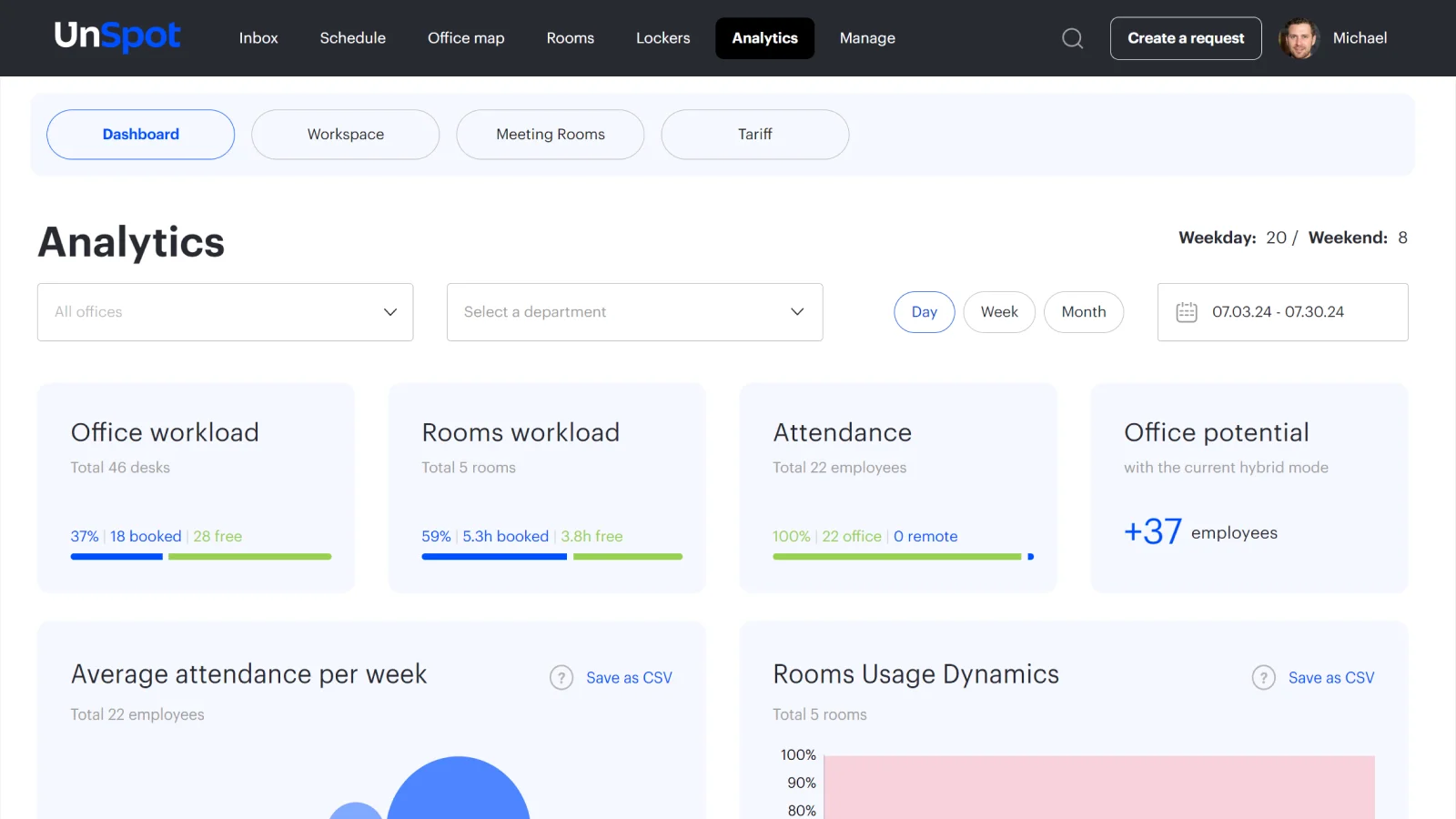

Integrating tools and platforms designed to facilitate team collaboration into research workflows addresses key challenges in research management and teamwork.

For example, References’ unlimited folder structures allow researchers to organize large quantities of data and documents in a way that mirrors the complexity of their projects, making it easier to locate specific materials quickly. This organization, paired with the ability to share folders and set access levels, streamlines the collaboration process, allowing team members to easily contribute to and review shared materials.

Optimize collaboration and productivity across your organization with the ability to create, manage, and share folders with User Groups.

Furthermore, the integration of personal and shared spaces, along with the capability to annotate PDFs, fosters a more cohesive workflow, encouraging real-time feedback and discussion. Export functionalities and real-time updates also ensure that all collaborators are working with the most current data and findings, reducing administrative overhead and enhancing the efficiency of collaborative research efforts.

2. Foster a culture of trust and accountability among team members with meticulous citation and knowledge management.

At the core of research lies a fundamental principle: the preservation of source integrity. By carefully managing and safeguarding the integrity of sources, teams can confidently build on previous findings, encourage innovation, and avoid misinformation. This fosters a culture rooted in trust and accountability, establishing a strong foundation for scholarly communication. These practices empower researchers to critically engage with existing literature and contribute new knowledge with credibility and reliability.

Tools like Article Galaxy References offer improved approaches to streamlined citation management. Effective management facilitates access to relevant literature and resources, enabling team members to work more efficiently, while also allowing for the accurate reference of the original concepts and findings in published scientific literature.

Auto-magically bulk update metadata from the selected folder, saving time and headaches, especially when exporting and sharing citation information.

By maintaining a well-organized repository of sources, teams can easily retrieve and reference materials, contributing to a more coherent and cohesive research effort.

Global search capabilities allows for efficient retrieval of documents and the inclusion of collaborative folders facilitates easy access to shared materials.

These robust citation practices, facilitated through software solutions, are foundational to the academic discourse, enabling researchers to build upon the work of their peers, challenge existing theories, and propose new insights. In essence, proper citation and literature management are essential for maintaining the integrity, efficacy, and progressive nature of collaborative research endeavors.

3. Create a standardized yet flexible system that’s tailored to your organization.

It's no great secret that organization enables individuals and teams to operate more efficiently, make better use of their time, and achieve their goals with less effort and stress. But sometimes putting this organization into practice is easier said than done. Management solutions equip researchers with the infrastructure and functionality necessary to develop a unified collaborative research approach that aligns with organizational goals and objectives.

For instance, custom fields offer an additional layer of organization within References. Admins have the option to set up global custom fields, ensuring consistency in organizational citation styles across all articles. Alternatively, team members can create custom fields at the folder level for more specific categorization. The intuitive interface enables easy modification of field names and options, streamlining customization without unnecessary complications and freeing up time for other tasks.

With the augmented functionality of our PDF Annotations Viewer, users can now view and select Custom Fields created for Personal or Shared Folders and Global Custom Fields deployed by Admins directly in the PDF reading environment.

References also offers Microsoft Outlook and Word Add-Ins, allowing researchers to effortlessly insert citations and bibliographies, switching between a wide array of citation styles, ensuring all team members have access to the entire collection, and transforming team collaboration with this straightforward integration into daily communications.

Save time citing and writing in Microsoft Word with our Company PDF Library integration which streamlines citation in reports and articles throughout your organization.

Striking a balance between standardization and flexibility fosters seamless collaboration among team members, ensuring consistent quality and accuracy, while also adapting to the evolving needs of teams in a fast-paced, information-rich environment. This ultimately bolsters the integrity and impact of research findings across the board.

4. Grant your team with peace of mind by ensuring they know who is working with specific materials and that their work is secure.

Team members need to be able to collaborate with confidence, assured that their data is protected and that they are accessing the most up-to-date versions of materials.

The recent enhancements in alerting features for Shared and Company Shared Folders represent a significant stride in collaborative efficiency for research teams. Now, team members can receive email notifications about new additions, keeping them updated on the latest resources and findings without constant manual checking. Whether opting for daily or weekly summaries, these notifications align with the team's workflow, ensuring everyone has the most current information for discussions and decisions. Visual indicators and the "Date Added" column further streamline tracking updates and integrating new data into ongoing projects. Together, these tools create a more connected, productive, and organized research environment, allowing teams to advance their projects with unprecedented speed and cohesion.

We've introduced new alerting capabilities for recently added items in Shared Folders and Company Shared Folders.

Moreover, all organizational structures and citation entries within References are securely stored in the cloud, ensuring accessibility across various devices and platforms. This seamless accessibility empowers teams to efficiently manage their research workflow from any location and on any device. While facilitating organizational collaboration, this approach also upholds data security by restricting the sharing of folders and content with users outside the organization. This safeguards the confidentiality of sensitive research materials within the organizational framework.

Maximize Your Team's Potential with Article Galaxy References

Article Galaxy References offers comprehensive solutions that empower research teams to seamlessly manage and access relevant materials, customize their workflow, and streamline collaboration. By simplifying these processes, it enables researchers to focus more on their work, ultimately leading to increased productivity and advancements in knowledge and discovery.

To explore these innovative solutions and strategies further, we invite you to join us for our upcoming webinar or schedule a live demo . Our team is ready to guide you through each new feature, addressing any questions you may have along the way.

Related Blogs

An easy way to keep up with covid-19 resea....

In our previous post, we shared a number of efforts Research Solutions has implemented to help our customers (and the broader research community) during the coronavirus crisis—including the release...

How to Turn Your Team into A Collaborative...

Executing complex initiatives such as pharmaceutical breakthroughs or advancements in medical device technology requires a breadth of knowledge that is accessible, organized, and shared across large,...

Our new logo, from Reprints Desk to Resear...

As of November 2019, Reprints Desk, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Research Solutions, Inc. will begin to transition into Research Solutions. Research Solutions will act as the parent company for...

Ready to See Article Galaxy in Action?

Schedule a call with one of our advisors. We will get you started with a FREE 14-day trial, with no obligation.

REQUEST MORE INFORMATION

Schedule a call with a knowledgeable Research Solutions advisor. We'll get you started with a FREE 14-day trial, with no obligation.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Advice for running a successful research team

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Midwifery and Indigenous Health, Charles Sturt University, Bathurst, NSW, Australia.

- PMID: 26563930

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.23.2.36.s8

Aim: To explore what is meant by a 'research team' and offer practical suggestions for supporting an effective and productive, collaborative research team.

Background: Collaborative research has become one of the main objectives of most higher education institutions and running effective research teams is central to achieving this aim. However, there is limited guidance in the literature about how to run or steer a research team.

Data sources: Search engines/databases used: CINAHL, Nursing and Allied Health Source, Primo search, Google search and Health Collection to access research articles and publications to support this topic. Literature search was extended to the end of 2014.

Review methods: Publications were reviewed for relevance to the topic via standard literature search.

Discussion: Research teams vary in size and composition, however they all require effective collaboration if they are to establish successful and flexible working relationships and produce useful and trustworthy research outputs. This article offers guidance for establishing and managing successful collaborative research relationships, building trust and a positive research team culture, clarifying team member roles, setting the teams' research agenda and managing the teams' functions so that team members feel able to contribute fully to the research goals and build a culture of support and apply 'emotional intelligence' throughout the process of building and running a successful research team.

Conclusion: Collaboration is a central component of establishing successful research teams and enabling productive research outputs. This article offers guidance for research teams to help them to function more effectively and allow all members to contribute fully to each team's goals.

Implications for practice/research: Research teams that have established trust and a positive team culture will result in more efficient working relationships and potentially greater productivity. The advice offered reinforces the value of having research teams with diverse members from different disciplines, philosophical roots and backgrounds. Each of these members should be able to contribute skills and expertise so that the parts of the team are able to develop 'synergy' and result in more productive, positive and rewarding research experiences, as well as more effective research.

Keywords: Collaborative research; group collaboration; nursing research; research processes; research team; team management teamwork.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Understanding the distinct experience of rural interprofessional collaboration in developing palliative care programs. Gaudet A, Kelley ML, Williams AM. Gaudet A, et al. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(2):2711. Epub 2014 May 14. Rural Remote Health. 2014. PMID: 24825066

- How has the impact of 'care pathway technologies' on service integration in stroke care been measured and what is the strength of the evidence to support their effectiveness in this respect? Allen D, Rixson L. Allen D, et al. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2008 Mar;6(1):78-110. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2007.00098.x. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2008. PMID: 21631815

- Learning about teams by participating in teams. Magrane D, Khan O, Pigeon Y, Leadley J, Grigsby RK. Magrane D, et al. Acad Med. 2010 Aug;85(8):1303-11. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e5c07a. Acad Med. 2010. PMID: 20671456

- Does Synergy Exist in Nursing? A Concept Analysis. Witges KA, Scanlan JM. Witges KA, et al. Nurs Forum. 2015 Jul-Sep;50(3):189-95. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12109. Epub 2014 Aug 17. Nurs Forum. 2015. PMID: 25130592 Review.

- Applying research to practice. Practical guidelines for occupational health nurses. Salazar MK. Salazar MK. AAOHN J. 2002 Nov;50(11):520-5; quiz 526-7. AAOHN J. 2002. PMID: 12465209 Review.

- Practicalities of implementing burden of disease research in Africa: lessons from a population survey component of our multi-partner FOCAL research project. Desta BN, Gobena T, Macuamule C, Fayemi OE, Ayolabi CI, Mmbaga BT, Thomas KM, Dodd W, Pires SM, Majowicz SE, Hald T. Desta BN, et al. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2022 Jun 7;19(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s12982-022-00113-y. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2022. PMID: 35672710 Free PMC article.

- Lessons Learned from an Academic, Interdisciplinary, Multi-Campus, Research Collaboration. Nguyen E, Xu X, Robinson R. Nguyen E, et al. Innov Pharm. 2020 Apr 30;11(2):10.24926/iip.v11i2.3202. doi: 10.24926/iip.v11i2.3202. eCollection 2020. Innov Pharm. 2020. PMID: 34007604 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4-2 Working Collaboratively: Building a Research Team

Yusuf Yilmaz and Sandra Monteiro

Collaboration is critical to conducting good research and designing good education or innovations. In any discipline, it is a rare situation where an individual has all the knowledge, skills and perspectives required to identify a good idea and develop it to completion and dissemination (1,2). An individual cannot manage all tasks in an efficient or short amount of time.

Critically, health professions education is a rich, multidisciplinary environment that requires collaboration across diverse professions, epistemologies and identities. A scientist may not be able to appreciate the nuances of clinical practice if they do not collaborate to understand the key issues. A clinician educator may not have the capacity to translate all aspects of education science without the support of a researcher. Simply put, we all have gaps in our ability to understand the unique education challenges that we are interested in exploring and can rely on various kinds of experts to supplement our knowledge.

This form of collaboration can create a richer, more complete understanding, but can also be more efficient as experts are much faster than novices at handling tasks within their scope.

Key Points of the Chapter

By the end of this chapter the learner should be able to:

- Describe the importance of teamwork for research

- Identify the priorities when setting up a new research team

- Recognize the challenges for collaboration with novel research teams or team members

Samir decided to talk to his supervisor about the challenge he perceived regarding getting such a diverse team to successfully coordinate their schedules and write together. She suggested that he apply his expert organizational skills to create the writing plan, but then involve the others on the team to complete some of the tasks. She also suggested that he take advantage of available online applications, like Google Docs and Microsoft Teams to create shared space for idea generation, without the need for synchronous meetings.

Deeper Dive into this Concept

Organization and clarity are key to the collaborative writing process. Whether you are writing collaboratively to produce an academic manuscript, or to design new learning objectives and activities for a new curriculum, there are some key principles that can help keep you on track.

First, it helps to identify a leader – not everyone can steer a ship all at the same time – so pick a captain who will be responsible for keeping everyone on task. It is also the leader’s responsibility to make sure there is a shared model of the goal, that everyone on the team understands how they can contribute to the goal and that everyone agrees on the key timeline and checkpoints. Although it can be a challenge managing multiple busy schedules, attempt to start with one synchronous group meeting to create a shared model of the goal. Online applications like Doodle (3) polls or When2meet (4) can be useful in achieving this goal. Also consider holding the meeting online in Zoom (5) or Microsoft Teams (6) as this will allow you to easily record the meeting discussion, which can be transcribed for future review by the group or individuals who could not attend.

Second, be clear on roles and authorship. Review the ICMJE authorship criteria so everyone understands the standards for authorship (7). For academic manuscripts, it is conventional to list all contributors’ names in the order of their level of contribution. The key author positions that are often important for those who write in academic medicine are: first author (the team leader), second (the second-in-command), and senior (the supervisor and/or mentor of the first author and/or the person responsible for a broader program of research). It helps to be clear on these positions at the start of a project, although circumstances may require flexibility over time. The first author is most likely to create the first draft or outline. Ideally, the first author is also the team leader, however this may not be the case for every team. Sometimes, the person elected to manage timelines and expectations is someone in the middle or the senior author.

Third, explain the writing process to everyone on the team and assign roles accordingly. It may seem like common sense, but all writing starts with the first and worst draft. The team members take turns editing it to a better version. Ideally, one person is responsible for the final edit in a consistent voice and style. Moreover, supplementary roles that may be required are a content expert – perhaps someone leading the field who can offer consultation. This person may already be on the team, or can be invited at a later stage of writing to consult. Because this consultant would not meet authorship criteria ( see ICMJE criteria ), they can be mentioned in the acknowledgments.

Fourth, collaborative writing can be highly efficient with the support of various online applications. A common application is Google Docs (8) which allows multiple team members to log in simultaneously, or asynchronously, to edit a single document. It is worth your time to learn how to track edits using the version history and make suggestions (i.e., tracking changes style of annotated suggestions). Google Docs also allow using third party citation managers. Zotero is one free and open source tool that fully integrates with Google Docs and provides citation management in a document (9). The table (4.2.1) below, taken from Yilmaz et al. identifies several online resources that can be used in an asynchronous fashion to facilitate collaborative writing, without having to schedule group meetings to write together (10).

| Whiteboard for brainstorming | Google Jamboard Google Docs Google Slides Mural MiroZoom “Whiteboard” feature | Use the sticky note technique to share and to organize thoughts. Sticky notes can facilitate organizing themes and components to discuss with team members. “Brain dumping” on each sticky note allows free flow of thoughts; the team can subsequently eliminate those they decide to exclude. | Convert sticky notes to an outline to build a manuscript’s story. Each sticky note should contain a single idea to allow for easy organization. Colour coding sticky notes can facilitate organization. For instance, green can signify positive, yellow can signify neutral and red can signify contradictory ideas and opinions. Alternatively, colour codes can correspond to different authors, representing assignments or ideas. Create grids or columns to organize sticky notes. |

| File sharing & organization | Google Drive Dropbox OneDrive MS Teams | A project may have multiple files. Storing documents and versions on the cloud allows team members to access them ubiquitously and instantly without sending through email or any other way. This prevents losing files from emails or a computer’s local drive. The cloud providers have extensions to synchronize the files with the computer’s local drive which allows local work and synchronizes the files cloud automatically. Creating and hosting figures and tables in separate documents when they cannot be integrated with a writing canvas. Additionally, dataset, analysis results and other project-related documents can be synchronized throughout the team members | Maintain appropriate privacy and security settings for datasets and sensitive non-anonymized content through password-protection where applicable and use of the appropriate platform. Ensure IRB approval for storage practices. In some instances, the use of your institution’s designated cloud storage platform may be required to meet data security and privacy standards. (e.g., ). Utilize version history for retrieval of deleted content. Although Google docs allow for simultaneous editing of the same file version by multiple collaborators, other cloud storage platforms that save files as MS Word documents can generate multiple copies when collaborators edit them simultaneously. Multiple exports may disrupt version control and require authors to manually merge different versions. Let your collaborators know when you actively work on the file. Some platforms allow authors to “lock” a file when actively editing it. Save files with version suffix (e.g., “name of the file _ V2.docx”) and append your initials to the file name that you let others that you reviewed and/or edited the file (e.g., “name of the file _ V2_YY_TC.docx”). |

| The writing canvas | Google Docs, Dropbox Paper, Microsoft Word Office 365 | Online documents that support synchronous writing on the same document with team members. Perform simultaneous edits and writing. When utilizing a mode that tracks changes, perform regular ‘change acceptances’ to make the document easier to follow. First or last author may lead on integrating changes and suggestions with the document. Version history and version naming provides quick access to the snapshots of the document’s status at a given moment. This also provides a record of changes made by specific team members. | Enable document change notifications. This will motivate and inform other team members that a team member is working on the document. This feature will “nudge” other team members to write. Commenting on the document by highlighting specific text enables further discussion. Team leaders or specific authors mentioned in the comment can “resolve” comments once they address them. Create a general template with specific article headlines and use when starting a new project (e.g. ) Use headline styling to create a table of contents; this allows for efficient navigation to specific sections of a manuscript using the navigation pane. |

| Asynchronous Communication | Slack MS Teams Text Message | Asynchronous communications facilitate project completion, particularly for individuals operating in different time zones and on different schedules. Although most asynchronous communication has traditionally occurred via email, chat-based platforms allow for more natural “conversation” and enhanced organization and storage of project files and discussion in a central location. | Ask, share and help the progress via asynchronous communication Tag specific co-authors for whom you have specific questions in order to generate an alert/notification to them. Continued engagement and idea creation foster virtual communities of practice. |

| Synchronous communication | Zoom WebEx Google MeetSkype | Allows for an initial brainstorming session during which to create a shared mental model with regard to project goals, outline, target journal, authorship order, timeline, roles and responsibilities. Synchronous check-ins allow authors to maintain accountability, identify and address barriers to project completion, and clarify points of confusion among the team. | Conduct synchronous meetings at the beginning, middle, and end. Use synchronous communication for sensitive and/or nuanced conversations such as “the academic prenup”: the potentially uncomfortable conversation about authorship order and expectations for the first, second and last authors. Discuss goals and timelines early and check in often. Dissect out the “pieces” of the paper into manageable, discrete tasks, and delineate each step in a timeline. |

| Reference management | Zotero Paperpile Mendeley Cite Endnote | A few citation managers work with an online writing canvas for easy citation on online documents. While there are common formats for citation styles (e.g., AMA, APA, Vancouver), some journals require specific formats which one cannot incorporate into the citation managers easily. In this case, finding the right style using Citation Style Language (CSL: ) makes the citation experience seamlessly easy. Using the visual designer, you can find the most similar format to your needs and even you can further add custom edits. | Use group features of citation managers to edit bibliographic information of publications. If your team is less tech-savvy, assign a citation management role to one team member. This way will not need group features for citation. Zotero allows from Google Docs to Microsoft Word conversion without losing the citations already cited within the manuscript. Use comment bubbles for citation information and put DOI, bibliographic information or the URL of the article to make it easier to cite later when you cannot work with the citation manager at that time which also makes writing quicker. |

| Meeting scheduling software | Doodle When2meet | Coordinate times for synchronous meetings among groups of authors with varying schedules | Specify the time zone of the meeting times when working with others in varying geographic locations. Be mindful of work-life balance; recognize team members may wish to avoid early morning, evening or weekend meeting times unless absolutely necessary. Provide several options and allow participants adequate lead time before the first meeting option to enter their availability. Provide a deadline for poll completion and send reminders to complete the poll as necessary. For smaller groups, deciding the next meeting time in real-time at the end of a synchronous meeting may represent a more efficient approach than utilizing meeting software. |

| Calendar management software | Gmail Outlook | Schedule synchronous meetings. Add deadline reminders to the team members by inviting multiple calendar invitations. | Send calendar invitations with embedded links to video-conferencing software and relevant cloud-based documents to officially reserve them on team members’ calendars. |

Key Takeaways

In summary, when approaching a collaborative activity, whether research design, curriculum design or innovation, always be clear about individual and group expectations.

- Sharing – Create shared accessible material that helps everyone track progress and understand their role.

- Be Explicit – Identify key tasks and connect them explicitly with individuals and deadlines.

- Structure – Ensure that there is a transparent structure to your project. Whether you are building a research team or writing a paper, it is vital to spend time and effort making sure everyone on the team understands the goals, deadlines and their role within the team.

- Support – Encourage psychological safety within your team so that when team members encounter barriers or challenges they can ask for help. Establish checkpoints to make sure everyone can celebrate their progress or can ask for help with their tasks

- Flexibility – Be prepared to change the plan when necessary. As clear as the plan is at the beginning, there is always a chance that new data will lead you to reconsider your original goals or research questions.

- Walker DHT, Davis PR, Stevenson A. Coping with uncertainty and ambiguity through team collaboration in infrastructure projects. Int J Proj Manag. 2017;35(2):180-190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.11.001

- Bennett LM, Gadlin H. Collaboration and Team Science: From Theory to Practice. J Investig Med. 2012;60(5):768-775. doi:10.2310/JIM.0b013e318250871d

- Doodle. Doodle: Explore features for the world’s favorite scheduling tool. Accessed November 18, 2021. https://doodle.com/en/features/

- When2meet. When2meet. Accessed November 18, 2021. https://www.when2meet.com/

- Zoom. Video Conferencing, Web Conferencing, Webinars, Screen Sharing. Zoom Video. Accessed March 31, 2020. https://zoom.us/

- Video Conferencing, Meetings, Calling | Microsoft Teams. Accessed November 18, 2021. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-teams/group-chat-software

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. ICMJE | Recommendations | Defining the Role of Authors and Contributors. Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html

- Google Docs: Free Online Document Editor | Google Workspace. Accessed November 18, 2021. https://www.google.ca/docs/about/

- Zotero | Your personal research assistant. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.zotero.org/

- Yilmaz Y, Gottlieb M, Calderone Haas MR, Thoma B, Chan TM. Remote Collaborative Writing A Guide to Writing within a Virtual Community of Practice. Manuscript submitted.

Other suggested resources

1. MacPFD Google Docs Template for Academic Writing

The above hyperlink leads you to a template that you can use to kickstart your team’s writing. It has the ICMJE criteria listed as well as a grid for scaffolding your initial co-authorship discussions as well.

2. MacPFD Scholarly Secrets – Collaborative Writing – Part 1: Overview of Google docs & Zotero (38 mins)

2. MacPFD Scholarly Secrets – Collaborative Writing – Part 2: The Benefits of Collaborative Writing & Tips (35 mins)

3. MacPFD Scholarly Secrets – Collaborative Writing – Part 3: Timelines, Coordination & Outlines (15 mins)

About the authors

name: Yusuf Yilmaz

institution: McMaster University / Ege University

website: https://yilmazyusuf.com

Yusuf Yilmaz is a postdoctoral fellow ithin the Office of Continuing Professional Development and the McMaster Education Research, Innovation, and Theory (MERIT) program, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University. He is a researcher-lecturer in the Department of Medical Education at Ege University, Izmir, Turkey.

name: Sandra Monteiro

institution: McMaster University

Sandra Monteiro is an Associate Professor within the Department of Medicine, Division of Education and Innovation, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University. She holds a joint appointment within the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact , Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University.

4-2 Working Collaboratively: Building a Research Team Copyright © 2022 by Yusuf Yilmaz and Sandra Monteiro is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Open access

- Published: 14 January 2020

How to grow a successful – and happy – research team

- Kylie Ball ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2893-8415 1 &

- David Crawford 1

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity volume 17 , Article number: 4 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

3 Citations

253 Altmetric

Metrics details

Changing academic landscapes, including the increasing focus on performance rankings and metrics, are impacting universities globally, contributing to high-pressure environments and anxious academic staff. However, evidence and experience shows that fostering a high performing academic team need not be incompatible with staff happiness and wellbeing.

The changing academic landscape

Global academic rankings have become a key indicator of the success of universities. Ranking systems are used by universities to mark improvement over time and in comparison to other institutions, and as evidence of progress when requesting government funding. They are also used by consumers to evaluate higher education opportunities [ 9 ]. This intensified focus has led to pressure on universities to improve their performance and position in rankings tables [ 3 ].

Reputation and research citations account for the majority of the rankings. Advice on improving rankings has hence focused on strategies such as hiring research ‘stars’ and increasing research volume; that is, on strategies for growing research. Relatively little attention has focused on growing researchers. For example, a Times Higher Education list of 20 tips for improving rankings included “no pain no gain” (in making tenure decisions) as one tip, yet featured only two fleeting references to strategies focused on nurturing academics [ 4 ].