Conducting and Writing Literature Reviews

Cite this chapter.

- Lorrie Blair 2

Part of the book series: Teaching Writing ((WRIT))

8644 Accesses

To contribute new knowledge to a field of study, students must first establish a comprehensive understanding of existing knowledge. For Holbrook, Bourke, Fairbairn, and Lovat (2007), “The use and application of the literature is at the heart of scholarship—of belonging to the academy” (p. 346). It is the foundation on which the entire thesis rests. However, many students, despite having written many course papers, have no idea of how to write the literature review or even where to start.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Concordia University, Canada

Lorrie Blair

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Sense Publishers

About this chapter

Blair, L. (2016). Conducting and Writing Literature Reviews. In: Writing a Graduate Thesis or Dissertation. Teaching Writing. SensePublishers, Rotterdam. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-426-8_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-426-8_4

Publisher Name : SensePublishers, Rotterdam

Online ISBN : 978-94-6300-426-8

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Importance of Literature Review

research proposal as a problem to investigate, it usually has to be fairly narrow and focused, and because of this it can be difficult to appreciate how one's research subject is connected to other related areas. Therefore, the overall purpose of a literature review is to demonstrate this, and to help the reader to understand how your study fits into a broader context. This paper seeks to examine this topic of literature review, its significance and role in research proposal and report. It will start by explaining in detail what literature is; by citation of different scholars and its constituent components, such as the theoretical framework. Thereafter, it will look at the importance of literature review and its role in research proposals and reports. Finally, a conclusion will be written based on this topic. A Literature Review is a critical review of existing knowledge on areas such as theories, critiques, methodologies, research findings, assessment and evaluations on a particular topic. A literature review involves a critical evaluation identifying similarities and differences between existing literatures and the work being undertaken. It reviews what have already been done in the context of a topic. Therefore, on the basis of the existing knowledge, people can build up innovative idea and concept for further research purpose (Cooper, 1998). In doing empirical literature review is reading reports of other relevant studies conducted by different researchers. In doing so, a researcher gets knowledge and experiences that were established by other researchers when conducting their studies. While Conceptual framework is a set of coherent ideas or concepts organised in a manner that makes them easy to communicate to others. It represents less formal structure and used for specific concepts and propositions derived from empirical observation and intuition (ibid). According Aveyard, H. (2010) Theoretical framework is a theoretical perspective. It can be simply a theory, but can also be more general a basic approach to understanding something. Typically, a theoretical framework consists of concepts, together with their definitions, and existing framework must demonstrate an understanding of theories, and existing framework demonstrate an understanding of theories and concepts that are relevant to the topic of your research proposal and that will relate it to the broader fields of knowledge in the class you are taking.

Related Papers

Journal of African Interdisciplinary Studies

Ronald Mensah

This article critically discusses, the relationship between conceptual framework and theoretical framework drawing on their differences and similarities. The article has made it very clear that whereas the theoretical framework is drawn from the existing theoretical literature that you review about your research topic, a conceptual framework is a much broader concept that encompasses practically all aspects of your research. The latter refers to the entire conceptualisation of your research project. It is the big picture, or vision, comprising the totality of research. Methodologically, the paper used systematic and experiential literature review to draw supporting scholarly literature by authorities in the field and made inferences, sound reasonings and logical deductions from these authorities. The primary aim of this paper is to help researchers and students to understand the convergence and the divergence of theoretical and conceptual frameworks in order to appropriately be applied in research and academic writing discourses. Understanding the conceptual framework affects research in many ways. For instance, it assists the researcher in identifying and constructing his/her worldview on the phenomenon to be investigated. Also, it is the simplest way through which a researcher presents his/her asserted remedies to the milieu he/she has created. In addition, this accentuates the reasons why a research topic is worth studying, the assumptions of a researcher, the scholars he/she agrees with and disagrees with and how he/she conceptually grounds his/her approach. Paying attention, to the theoretical framework and its impact on research, it can be mentioned that theoretical framework provides a structure for what to look for in the data, for how you think of how what you see in the data fits together, and helps you to discuss your findings more clearly, in light of what existing theories say. It helps the researcher to make connections between the abstract and concrete elements observed in the data. In conclusion, both theoretical framework and conceptual framework are good variables which are used to inform a study to arrive at logical findings and conclusions. It is therefore recommended by researchers that; a good theoretical framework should be capable of informing the concepts in a research work.

Abey Dubale

Martin Otundo Richard

ABSTRACT A number of researchers either in scientific, social or academic researchers have found it difficult to differentiate between the theoretical and conceptual framework and their importance. This is a simple overview of the basic differences and some similarities between the theoretical and conceptual framework that is aimed at helping the learners and other researchers get a fast grasp of what can help them use the two effectively in their studies. A summary has been provided at the last part of the document that can aid one get the required information in his or her research.

Tonette S Rocco , Maria Plakhotnik

Abstract This essay starts with a discussion of the literature review, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework as components of a manuscript. This discussion includes similarities and distinctions among these components and their relation to other sections of a manuscript such as the problem statement, discussion, and implications. The essay concludes with an overview of the literature review, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework as separate types of manuscripts.

Ewnetu Tamene

The impetus of this paper is the irreplaceable role yet confusing use of the term " conceptual framework " in research literature. Even though, there is a consensus among scholars of various field of study that conceptual framework is essential element of research endeavors, yet it is used interchangeably with theoretical framework, that create confusion. As a PhD student on the pre-proposal work, this makes me more anxious. Then my intent is to explore its conceptual meaning and purposes by bringing together similar meanings from different scholars with a view to shed some light on its understanding and its use in research. Hence, in attempting to address this, the following key terms; Concept, conceptual framework research design and theoretical framework are defined briefly as to help decipher the conceptual ties among them and illuminate the conceptual meaning and purpose of conceptual framework. The schematic representation of conceptual framework is developed based on the conceptual meaning provided by scholars. In doing this it is attempted to show conceptual meaning of conceptual framework in relation to research design, paradigms and philosophical assumptions that delineate it from theoretical framework. Conceptual framework serves essential role in inductive research design, while theoretical framework serves similar role in deductive research design.

This is an opinion piece on the subject of whether or not 'theoretical' and 'conceptual' frameworks are conceptual synonyms, or they refer to different constructs. Although, generally, a lot of liter ature uses these two terms interchangeably – suggesting that they are conceptually equivalent, the researcher argues that these are two different constructs – both by definition and as actualised during the research process. Thus, in this paper, the researcher starts by developing his argument by examining the role of theory in research, and then draws a distinction between areas of research that typically follow deductive versus inductive approaches, with regard to both the review of literature and data collection. The researcher then subsequently argues that whereas a deductive approach to literature review typically makes use of theories and theoretical frameworks, the induct ive approach tends to lead to the development of a conceptual framework – which may take the form of a (conceptua l) model. Examples depicting this distinction are advanced.

Nauka i društvo

Darko M Marković

Conceptual framework is the foundation of scientific research, and it is formed from previous knowledge about the researched phenomenon. It is an integral part of theoretical framework, made with the aim to include key terms, presented within the bibliography, and create a suitable platform to develop the research correctly. More often with students preparing their final papers, and not so rarely with established researchers, the problem arises when it comes to conceptualizing research. A common unknown is how to divide conceptual from theoretical framework, and what conceptual framework of scientific research actually is. The aim of this paper is to clarify conceptualization of scientific research, and, by clarifying it, to point out the significance of differentiation between conceptual and theoretical framework, going on to give basic guidelines on how to form one, and therefore ease the understanding of it and application in scientific research.

Aliya Ahmed

Elock E Shikalepo

Conducting educational research involves various stages, with an interdependence and inter-relationship which can be both iterative and progressive in nature. One of these stages is the review of literature sources related to the focus of the research. Reviewing related literature involves tracing, examining, critiquing, evaluating and eventually recommending various forms of contents to the intents of the research based on the content’s typicality, relevance, correctness and appropriateness to what the research intends to achieve. The main variables as stated in the title of the research, the research questions, the research objectives and the hypotheses, dictates the literature sources to review. Reviewing literature focuses on the existing related topics that bear relevance to the title of the research and through which reviewing, appropriate theories can be picked up as the review of related topics and phrases goes on. As soon as the related topics are reviewed and main points noted, the reviewing process proceeds to review the theories underpinning the study. Some of these theories would have been established while reviewing the related topics and can now gain momentum, while other theories can now be generated considering the title, research questions, research objectives and findings of the topics reviewed and discussed earlier. Reviewing related topics generates main points of arguments, solutions, gaps and propositions. Similarly, reviewing theories does produce the same set of corresponding or contrasting agreements, gaps and propositions. Despite reviewing different sources of literature, it is the same research at hand, with same objectives and same methodological layout. Hence, a need to shape a strategic, literature direction for the research by consolidating the key findings of the different sources reviewed, in view of the intents of the research. The process of consolidating the multiplicity of key literature findings relevant to the research into a whole single unit, with one standpoint revealing the strategic literature direction for the research, is called constructing a conceptual framework. The end product of this construction is the conceptual framework, which is the informed and consolidated results presented narratively or schematically, revealing the strategic position of the study in relation to what exists in literature.

pinky adona

Many students, both in the undergraduate and graduate levels, have difficulty discriminating the theoretical from the conceptual framework. This requires a good understanding of both frameworks in order to conduct a good investigation. This article explains the two concepts in easily understandable language. Read on to find out. Many graduating college students and even graduate students have difficulty coming up with the conceptual framework and the theoretical framework of their thesis, a required section in thesis writing that serves as the students' map on their first venture into research. The conceptual framework is almost always confused with the theoretical framework of the study. What is the difference between the conceptual and the theoretical framework? A conceptual framework is the researcher's idea on how the research problem will have to be explored. This is founded on the theoretical framework, which lies on a much broader scale of resolution. The theoretical framework dwells on time tested theories that embody the findings of numerous investigations on how phenomena occur. The theoretical framework provides a general representation of relationships between things in a given phenomenon. The conceptual framework, on the other hand, embodies the specific direction by which the research will have to be undertaken. Statistically speaking, the conceptual framework describes the relationship between specific variables identified in the study. It also outlines the input, process and output of the whole investigation. The conceptual framework is also called the research paradigm. Examples of the Theoretical and the Conceptual Framework The difference between theoretical framework and conceptual framework can be further clarified by the following examples on both concepts: Theoretical Framework: Stimulus elicits response. Conceptual Framework: New teaching method improves students' academic performance. Notice in the illustrative example that the theoretical framework basically differs from the conceptual framework in terms of scope. The theoretical framework describes a broader relationship between things. When stimulus is applied, response is expected. The conceptual framework is much more specific in defining this relationship. The conceptual framework specifies the variables that will have to be explored in the investigation. In this example, the variable " teaching method " represents stimulus while

RELATED PAPERS

Molecular Immunology

Alan Ezekowitz

Journal of Excipients and Food Chemicals

Adenike Okunlola

Journal of Clinical Investigation

osborne almeida

Eleanor Newbigin

Midwest Studies in Philosophy

John Wallace

mahnaz rabiei

Environmental Science & Technology

Louis McDonald

Hien Thuy Tran

Isaias Soares

Horizontes Antropológicos

Ricardo M O Campos

2008 IEEE Silicon Nanoelectronics Workshop

Hiroshi Inokawa

EPL (Europhysics Letters)

Federico Paolucci

Fourth Annual IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PERCOMW'06)

Daniel Díaz

Giorgio Costa

Revista Principia - Divulgação Científica e Tecnológica do IFPB

Marco Cavaco

Physical Review B

Luigi Paolasini

IMF Working Papers

Maarten De Zeeuw

Kevin William

Journal of Physics: Conference Series

Ignatios Antoniadis

Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Società italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale

fausto chiesa

IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering

olatokunbo ofuyatan

Ege Tıp Dergisi

International Journal of Law in Context

Lynette J Chua

Vol. 17 No. 3 (2024): Asia Social Issues: May - June

Asia Social Issues

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Grad Med Educ

- v.8(3); 2016 Jul

The Literature Review: A Foundation for High-Quality Medical Education Research

a These are subscription resources. Researchers should check with their librarian to determine their access rights.

Despite a surge in published scholarship in medical education 1 and rapid growth in journals that publish educational research, manuscript acceptance rates continue to fall. 2 Failure to conduct a thorough, accurate, and up-to-date literature review identifying an important problem and placing the study in context is consistently identified as one of the top reasons for rejection. 3 , 4 The purpose of this editorial is to provide a road map and practical recommendations for planning a literature review. By understanding the goals of a literature review and following a few basic processes, authors can enhance both the quality of their educational research and the likelihood of publication in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education ( JGME ) and in other journals.

The Literature Review Defined

In medical education, no organization has articulated a formal definition of a literature review for a research paper; thus, a literature review can take a number of forms. Depending on the type of article, target journal, and specific topic, these forms will vary in methodology, rigor, and depth. Several organizations have published guidelines for conducting an intensive literature search intended for formal systematic reviews, both broadly (eg, PRISMA) 5 and within medical education, 6 and there are excellent commentaries to guide authors of systematic reviews. 7 , 8

- A literature review forms the basis for high-quality medical education research and helps maximize relevance, originality, generalizability, and impact.

- A literature review provides context, informs methodology, maximizes innovation, avoids duplicative research, and ensures that professional standards are met.

- Literature reviews take time, are iterative, and should continue throughout the research process.

- Researchers should maximize the use of human resources (librarians, colleagues), search tools (databases/search engines), and existing literature (related articles).

- Keeping organized is critical.

Such work is outside the scope of this article, which focuses on literature reviews to inform reports of original medical education research. We define such a literature review as a synthetic review and summary of what is known and unknown regarding the topic of a scholarly body of work, including the current work's place within the existing knowledge . While this type of literature review may not require the intensive search processes mandated by systematic reviews, it merits a thoughtful and rigorous approach.

Purpose and Importance of the Literature Review

An understanding of the current literature is critical for all phases of a research study. Lingard 9 recently invoked the “journal-as-conversation” metaphor as a way of understanding how one's research fits into the larger medical education conversation. As she described it: “Imagine yourself joining a conversation at a social event. After you hang about eavesdropping to get the drift of what's being said (the conversational equivalent of the literature review), you join the conversation with a contribution that signals your shared interest in the topic, your knowledge of what's already been said, and your intention.” 9

The literature review helps any researcher “join the conversation” by providing context, informing methodology, identifying innovation, minimizing duplicative research, and ensuring that professional standards are met. Understanding the current literature also promotes scholarship, as proposed by Boyer, 10 by contributing to 5 of the 6 standards by which scholarly work should be evaluated. 11 Specifically, the review helps the researcher (1) articulate clear goals, (2) show evidence of adequate preparation, (3) select appropriate methods, (4) communicate relevant results, and (5) engage in reflective critique.

Failure to conduct a high-quality literature review is associated with several problems identified in the medical education literature, including studies that are repetitive, not grounded in theory, methodologically weak, and fail to expand knowledge beyond a single setting. 12 Indeed, medical education scholars complain that many studies repeat work already published and contribute little new knowledge—a likely cause of which is failure to conduct a proper literature review. 3 , 4

Likewise, studies that lack theoretical grounding or a conceptual framework make study design and interpretation difficult. 13 When theory is used in medical education studies, it is often invoked at a superficial level. As Norman 14 noted, when theory is used appropriately, it helps articulate variables that might be linked together and why, and it allows the researcher to make hypotheses and define a study's context and scope. Ultimately, a proper literature review is a first critical step toward identifying relevant conceptual frameworks.

Another problem is that many medical education studies are methodologically weak. 12 Good research requires trained investigators who can articulate relevant research questions, operationally define variables of interest, and choose the best method for specific research questions. Conducting a proper literature review helps both novice and experienced researchers select rigorous research methodologies.

Finally, many studies in medical education are “one-offs,” that is, single studies undertaken because the opportunity presented itself locally. Such studies frequently are not oriented toward progressive knowledge building and generalization to other settings. A firm grasp of the literature can encourage a programmatic approach to research.

Approaching the Literature Review

Considering these issues, journals have a responsibility to demand from authors a thoughtful synthesis of their study's position within the field, and it is the authors' responsibility to provide such a synthesis, based on a literature review. The aforementioned purposes of the literature review mandate that the review occurs throughout all phases of a study, from conception and design, to implementation and analysis, to manuscript preparation and submission.

Planning the literature review requires understanding of journal requirements, which vary greatly by journal ( table 1 ). Authors are advised to take note of common problems with reporting results of the literature review. Table 2 lists the most common problems that we have encountered as authors, reviewers, and editors.

Sample of Journals' Author Instructions for Literature Reviews Conducted as Part of Original Research Article a

Common Problem Areas for Reporting Literature Reviews in the Context of Scholarly Articles

Locating and Organizing the Literature

Three resources may facilitate identifying relevant literature: human resources, search tools, and related literature. As the process requires time, it is important to begin searching for literature early in the process (ie, the study design phase). Identifying and understanding relevant studies will increase the likelihood of designing a relevant, adaptable, generalizable, and novel study that is based on educational or learning theory and can maximize impact.

Human Resources

A medical librarian can help translate research interests into an effective search strategy, familiarize researchers with available information resources, provide information on organizing information, and introduce strategies for keeping current with emerging research. Often, librarians are also aware of research across their institutions and may be able to connect researchers with similar interests. Reaching out to colleagues for suggestions may help researchers quickly locate resources that would not otherwise be on their radar.

During this process, researchers will likely identify other researchers writing on aspects of their topic. Researchers should consider searching for the publications of these relevant researchers (see table 3 for search strategies). Additionally, institutional websites may include curriculum vitae of such relevant faculty with access to their entire publication record, including difficult to locate publications, such as book chapters, dissertations, and technical reports.

Strategies for Finding Related Researcher Publications in Databases and Search Engines

Search Tools and Related Literature

Researchers will locate the majority of needed information using databases and search engines. Excellent resources are available to guide researchers in the mechanics of literature searches. 15 , 16

Because medical education research draws on a variety of disciplines, researchers should include search tools with coverage beyond medicine (eg, psychology, nursing, education, and anthropology) and that cover several publication types, such as reports, standards, conference abstracts, and book chapters (see the box for several information resources). Many search tools include options for viewing citations of selected articles. Examining cited references provides additional articles for review and a sense of the influence of the selected article on its field.

Box Information Resources

- Web of Science a

- Education Resource Information Center (ERIC)

- Cumulative Index of Nursing & Allied Health (CINAHL) a

- Google Scholar

Once relevant articles are located, it is useful to mine those articles for additional citations. One strategy is to examine references of key articles, especially review articles, for relevant citations.

Getting Organized

As the aforementioned resources will likely provide a tremendous amount of information, organization is crucial. Researchers should determine which details are most important to their study (eg, participants, setting, methods, and outcomes) and generate a strategy for keeping those details organized and accessible. Increasingly, researchers utilize digital tools, such as Evernote, to capture such information, which enables accessibility across digital workspaces and search capabilities. Use of citation managers can also be helpful as they store citations and, in some cases, can generate bibliographies ( table 4 ).

Citation Managers

Knowing When to Say When

Researchers often ask how to know when they have located enough citations. Unfortunately, there is no magic or ideal number of citations to collect. One strategy for checking coverage of the literature is to inspect references of relevant articles. As researchers review references they will start noticing a repetition of the same articles with few new articles appearing. This can indicate that the researcher has covered the literature base on a particular topic.

Putting It All Together

In preparing to write a research paper, it is important to consider which citations to include and how they will inform the introduction and discussion sections. The “Instructions to Authors” for the targeted journal will often provide guidance on structuring the literature review (or introduction) and the number of total citations permitted for each article category. Reviewing articles of similar type published in the targeted journal can also provide guidance regarding structure and average lengths of the introduction and discussion sections.

When selecting references for the introduction consider those that illustrate core background theoretical and methodological concepts, as well as recent relevant studies. The introduction should be brief and present references not as a laundry list or narrative of available literature, but rather as a synthesized summary to provide context for the current study and to identify the gap in the literature that the study intends to fill. For the discussion, citations should be thoughtfully selected to compare and contrast the present study's findings with the current literature and to indicate how the present study moves the field forward.

To facilitate writing a literature review, journals are increasingly providing helpful features to guide authors. For example, the resources available through JGME include several articles on writing. 17 The journal Perspectives on Medical Education recently launched “The Writer's Craft,” which is intended to help medical educators improve their writing. Additionally, many institutions have writing centers that provide web-based materials on writing a literature review, and some even have writing coaches.

The literature review is a vital part of medical education research and should occur throughout the research process to help researchers design a strong study and effectively communicate study results and importance. To achieve these goals, researchers are advised to plan and execute the literature review carefully. The guidance in this editorial provides considerations and recommendations that may improve the quality of literature reviews.

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Harvard Graduate School of Design - Frances Loeb Library

Write and Cite

- Literature Review

- Academic Integrity

- Citing Sources

- Fair Use, Permissions, and Copyright

- Writing Resources

- Grants and Fellowships

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 10:28 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gsd/write

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

- Open access

- Published: 24 April 2024

Breast cancer screening motivation and behaviours of women aged over 75 years: a scoping review

- Virginia Dickson-Swift 1 ,

- Joanne Adams 1 ,

- Evelien Spelten 1 ,

- Irene Blackberry 2 ,

- Carlene Wilson 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Eva Yuen 3 , 6 , 7 , 8

BMC Women's Health volume 24 , Article number: 256 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

137 Accesses

Metrics details

This scoping review aimed to identify and present the evidence describing key motivations for breast cancer screening among women aged ≥ 75 years. Few of the internationally available guidelines recommend continued biennial screening for this age group. Some suggest ongoing screening is unnecessary or should be determined on individual health status and life expectancy. Recent research has shown that despite recommendations regarding screening, older women continue to hold positive attitudes to breast screening and participate when the opportunity is available.

All original research articles that address motivation, intention and/or participation in screening for breast cancer among women aged ≥ 75 years were considered for inclusion. These included articles reporting on women who use public and private breast cancer screening services and those who do not use screening services (i.e., non-screeners).

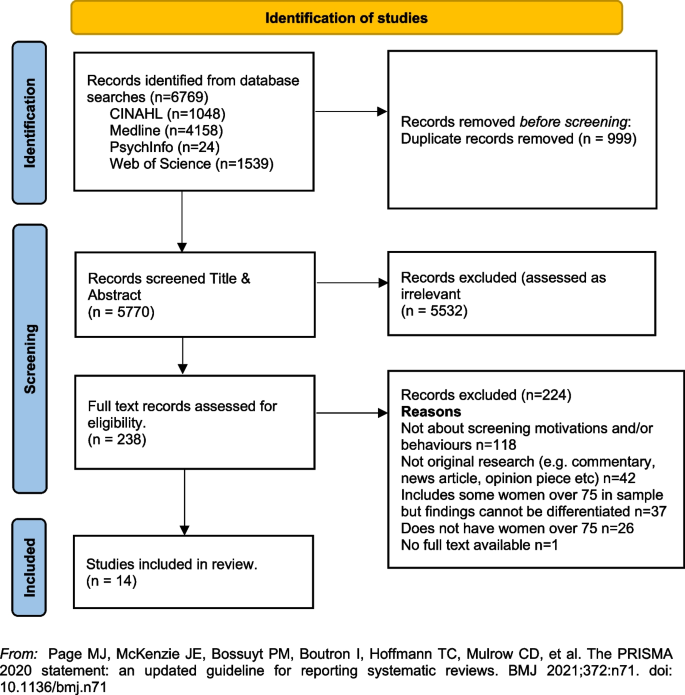

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews was used to guide this review. A comprehensive search strategy was developed with the assistance of a specialist librarian to access selected databases including: the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medline, Web of Science and PsychInfo. The review was restricted to original research studies published since 2009, available in English and focusing on high-income countries (as defined by the World Bank). Title and abstract screening, followed by an assessment of full-text studies against the inclusion criteria was completed by at least two reviewers. Data relating to key motivations, screening intention and behaviour were extracted, and a thematic analysis of study findings undertaken.

A total of fourteen (14) studies were included in the review. Thematic analysis resulted in identification of three themes from included studies highlighting that decisions about screening were influenced by: knowledge of the benefits and harms of screening and their relationship to age; underlying attitudes to the importance of cancer screening in women's lives; and use of decision aids to improve knowledge and guide decision-making.

The results of this review provide a comprehensive overview of current knowledge regarding the motivations and screening behaviour of older women about breast cancer screening which may inform policy development.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Breast cancer is now the most commonly diagnosed cancer in the world overtaking lung cancer in 2021 [ 1 ]. Across the globe, breast cancer contributed to 25.8% of the total number of new cases of cancer diagnosed in 2020 [ 2 ] and accounts for a high disease burden for women [ 3 ]. Screening for breast cancer is an effective means of detecting early-stage cancer and has been shown to significantly improve survival rates [ 4 ]. A recent systematic review of international screening guidelines found that most countries recommend that women have biennial mammograms between the ages of 40–70 years [ 5 ] with some recommending that there should be no upper age limit [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ] and others suggesting that benefits of continued screening for women over 75 are not clear [ 13 , 14 , 15 ].

Some guidelines suggest that the decision to end screening should be determined based on the individual health status of the woman, their life expectancy and current health issues [ 5 , 16 , 17 ]. This is because the benefits of mammography screening may be limited after 7 years due to existing comorbidities and limited life expectancy [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ], with some jurisdictions recommending breast cancer screening for women ≥ 75 years only when life expectancy is estimated as at least 7–10 years [ 22 ]. Others have argued that decisions about continuing with screening mammography should depend on individual patient risk and health management preferences [ 23 ]. This decision is likely facilitated by a discussion between a health care provider and patient about the harms and benefits of screening outside the recommended ages [ 24 , 25 ]. While mammography may enable early detection of breast cancer, it is clear that false-positive results and overdiagnosis Footnote 1 may occur. Studies have estimated that up to 25% of breast cancer cases in the general population may be over diagnosed [ 26 , 27 , 28 ].

The risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer increases with age and approximately 80% of new cases of breast cancer in high-income countries are in women over the age of 50 [ 29 ]. The average age of first diagnosis of breast cancer in high income countries is comparable to that of Australian women which is now 61 years [ 2 , 4 , 29 ]. Studies show that women aged ≥ 75 years generally have positive attitudes to mammography screening and report high levels of perceived benefits including early detection of breast cancer and a desire to stay healthy as they age [ 21 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. Some women aged over 74 participate, or plan to participate, in screening despite recommendations from health professionals and government guidelines advising against it [ 33 ]. Results of a recent review found that knowledge of the recommended guidelines and the potential harms of screening are limited and many older women believed that the benefits of continued screening outweighed the risks [ 30 ].

Very few studies have been undertaken to understand the motivations of women to screen or to establish screening participation rates among women aged ≥ 75 and older. This is surprising given that increasing age is recognised as a key risk factor for the development of breast cancer, and that screening is offered in many locations around the world every two years up until 74 years. The importance of this topic is high given the ambiguity around best practice for participation beyond 74 years. A preliminary search of Open Science Framework, PROSPERO, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and JBI Evidence Synthesis in May 2022 did not locate any reviews on this topic.

This scoping review has allowed for the mapping of a broad range of research to explore the breadth and depth of the literature, summarize the evidence and identify knowledge gaps [ 34 , 35 ]. This information has supported the development of a comprehensive overview of current knowledge of motivations of women to screen and screening participation rates among women outside the targeted age of many international screening programs.

Materials and methods

Research question.

The research question for this scoping review was developed by applying the Population—Concept—Context (PCC) framework [ 36 ]. The current review addresses the research question “What research has been undertaken in high-income countries (context) exploring the key motivations to screen for breast cancer and screening participation (concepts) among women ≥ 75 years of age (population)?

Eligibility criteria

Participants.

Women aged ≥ 75 years were the key population. Specifically, motivations to screen and screening intention and behaviour and the variables that discriminate those who screen from those who do not (non-screeners) were utilised as the key predictors and outcomes respectively.

From a conceptual perspective it was considered that motivation led to behaviour, therefore articles that described motivation and corresponding behaviour were considered. These included articles reporting on women who use public (government funded) and private (fee for service) breast cancer screening services and those who do not use screening services (i.e., non-screeners).

The scope included high-income countries using the World Bank definition [ 37 ]. These countries have broadly similar health systems and opportunities for breast cancer screening in both public and private settings.

Types of sources

All studies reporting original research in peer-reviewed journals from January 2009 were eligible for inclusion, regardless of design. This date was selected due to an evaluation undertaken for BreastScreen Australia recommending expansion of the age group to include 70–74-year-old women [ 38 ]. This date was also indicative of international debate regarding breast cancer screening effectiveness at this time [ 39 , 40 ]. Reviews were also included, regardless of type—scoping, systematic, or narrative. Only sources published in English and available through the University’s extensive research holdings were eligible for inclusion. Ineligible materials were conference abstracts, letters to the editor, editorials, opinion pieces, commentaries, newspaper articles, dissertations and theses.

This scoping review was registered with the Open Science Framework database ( https://osf.io/fd3eh ) and followed Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews [ 35 , 36 ]. Although ethics approval is not required for scoping reviews the broader study was approved by the University Ethics Committee (approval number HEC 21249).

Search strategy

A pilot search strategy was developed in consultation with an expert health librarian and tested in MEDLINE (OVID) and conducted on 3 June 2022. Articles from this pilot search were compared with seminal articles previously identified by the members of the team and used to refine the search terms. The search terms were then searched as both keywords and subject headings (e.g., MeSH) in the titles and abstracts and Boolean operators employed. A full MEDLINE search was then carried out by the librarian (see Table 1 ). This search strategy was adapted for use in each of the following databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Web of Science and PsychInfo databases. The references of included studies have been hand-searched to identify any additional evidence sources.

Study/source of evidence selection

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into EndNote v.X20 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and duplicates removed. The resulting articles were then imported into Covidence – Cochrane’s systematic review management software [ 41 ]. Duplicates were removed once importation was complete, and title and abstract screening was undertaken against the eligibility criteria. A sample of 25 articles were assessed by all reviewers to ensure reliability in the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Team discussion was used to ensure consistent application. The Covidence software supports blind reviewing with two reviewers required at each screening phase. Potentially relevant sources were retrieved in full text and were assessed against the inclusion criteria by two independent reviewers. Conflicts were flagged within the software which allows the team to discuss those that have disagreements until a consensus was reached. Reasons for exclusion of studies at full text were recorded and reported in the scoping review. The Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was used to guide the reporting of the review [ 42 ] and all stages were documented using the PRISMA-ScR flow chart [ 42 ].

Data extraction

A data extraction form was created in Covidence and used to extract study characteristics and to confirm the study’s relevance. This included specific details such as article author/s, title, year of publication, country, aim, population, setting, data collection methods and key findings relevant to the review question. The draft extraction form was modified as needed during the data extraction process.

Data analysis and presentation

Extracted data were summarised in tabular format (see Table 2 ). Consistent with the guidelines for the effective reporting of scoping reviews [ 43 ] and the JBI framework [ 35 ] the final stage of the review included thematic analysis of the key findings of the included studies. Study findings were imported into QSR NVivo with coding of each line of text. Descriptive codes reflected key aspects of the included studies related to the motivations and behaviours of women > 75 years about breast cancer screening.

In line with the reporting requirements for scoping reviews the search results for this review are presented in Fig. 1 [ 44 ].

PRISMA Flowchart. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

A total of fourteen [ 14 ] studies were included in the review with studies from the following countries, US n = 12 [ 33 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ], UK n = 1 [ 23 ] and France n = 1 [ 56 ]. Sample sizes varied, with most containing fewer than 50 women ( n = 8) [ 33 , 45 , 46 , 48 , 51 , 52 , 55 ]. Two had larger samples including a French study with 136 women (a sub-set of a larger sample) [ 56 ], and one mixed method study in the UK with a sample of 26 women undertaking interviews and 479 women completing surveys [ 23 ]. One study did not report exact numbers [ 50 ]. Three studies [ 47 , 53 , 54 ] were undertaken by a group of researchers based in the US utilising the same sample of women, however each of the papers focused on different primary outcomes. The samples in the included studies were recruited from a range of locations including primary medical care clinics, specialist medical clinics, University affiliated medical clinics, community-based health centres and community outreach clinics [ 47 , 53 , 54 ].

Data collection methods varied and included: quantitative ( n = 8), qualitative ( n = 5) and mixed methods ( n = 1). A range of data collection tools and research designs were utilised; pre/post, pilot and cross-sectional surveys, interviews, and secondary analysis of existing data sets. Seven studies focused on the use of a Decision Aids (DAs), either in original or modified form, developed by Schonberg et al. [ 55 ] as a tool to increase knowledge about the harms and benefits of screening for older women [ 45 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 52 , 54 , 55 ]. Three studies focused on intention to screen [ 33 , 53 , 56 ], two on knowledge of, and attitudes to, screening [ 23 , 46 ], one on information needs relating to risks and benefits of screening discontinuation [ 51 ], and one on perceptions about discontinuation of screening and impact of social interactions on screening [ 50 ].

The three themes developed from the analysis of the included studies highlighted that decisions about screening were primarily influenced by: (1) knowledge of the benefits and harms of screening and their relationship to age; (2) underlying attitudes to the importance of cancer screening in women's lives; and (3) exposure to decision aids designed to facilitate informed decision-making. Each of these themes will be presented below drawing on the key findings of the appropriate studies. The full dataset of extracted data can be found in Table 2 .

Knowledge of the benefits and harms of screening ≥ 75 years

The decision to participate in routine mammography is influenced by individual differences in cognition and affect, interpersonal relationships, provider characteristics, and healthcare system variables. Women typically perceive mammograms as a positive, beneficial and routine component of care [ 46 ] and an important aspect of taking care of themselves [ 23 , 46 , 49 ]. One qualitative study undertaken in the US showed that few women had discussed mammography cessation or the potential harms of screening with their health care providers and some women reported they would insist on receiving mammography even without a provider recommendation to continue screening [ 46 ].

Studies suggested that ageing itself, and even poor health, were not seen as reasonable reasons for screening cessation. For many women, guidance from a health care provider was deemed the most important influence on decision-making [ 46 ]. Preferences for communication about risk and benefits were varied with one study reporting women would like to learn more about harms and risks and recommended that this information be communicated via physicians or other healthcare providers, included in brochures/pamphlets, and presented outside of clinical settings (e.g., in community-based seniors groups) [ 51 ]. Others reported that women were sometimes sceptical of expert and government recommendations [ 33 ] although some were happy to participate in discussions with health educators or care providers about breast cancer screening harms and benefits and potential cessation [ 52 ].

Underlying attitudes to the importance of cancer screening at and beyond 75 years

Included studies varied in describing the importance of screening, with some attitudes based on past attendance and some based on future intentions to screen. Three studies reported findings indicating that some women intended to continue screening after 75 years of age [ 23 , 45 , 46 ], with one study in the UK reporting that women supported an extension of the automatic recall indefinitely, regardless of age or health status. In this study, failure to invite older women to screen was interpreted as age discrimination [ 23 ]. The desire to continue screening beyond 75 was also highlighted in a study from France that found that 60% of the women ( n = 136 aged ≥ 75) intended to pursue screening in the future, and 27 women aged ≥ 75, who had never undergone mammography previously (36%), intended to do so in the future [ 56 ]. In this same study, intentions to screen varied significantly [ 56 ]. There were no sociodemographic differences observed between screened and unscreened women with regard to level of education, income, health risk behaviour (smoking, alcohol consumption), knowledge about the importance and the process of screening, or psychological features (fear of the test, fear of the results, fear of the disease, trust in screening impact) [ 56 ]. Further analysis showed that three items were statistically correlated with a higher rate of attendance at screening: (1) screening was initiated by a physician; (2) the women had a consultation with a gynaecologist during the past 12 months; and (3) the women had already undergone at least five screening mammograms. Analysis highlighted that although average income, level of education, psychological features or other types of health risk behaviours did not impact screening intention, having a mammogram previously impacted likelihood of ongoing screening. There was no information provided that explained why women who had not previously undergone screening might do so in the future.

A mixed methods study in the UK reported similar findings [ 23 ]. Utilising interviews ( n = 26) and questionnaires ( n = 479) with women ≥ 70 years (median age 75 years) the overwhelming result (90.1%) was that breast screening should be offered to all women indefinitely regardless of age, health status or fitness [ 23 ], and that many older women were keen to continue screening. Both the interview and survey data confirmed women were uncertain about eligibility for breast screening. The survey data showed that just over half the women (52.9%) were unaware that they could request mammography or knew how to access it. Key reasons for screening discontinuation were not being invited for screening (52.1%) and not knowing about self-referral (35.1%).

Women reported that not being invited to continue screening sent messages that screening was no longer important or required for this age group [ 23 ]. Almost two thirds of the women completing the survey (61.6%) said they would forget to attend screening without an invitation. Other reasons for screening discontinuation included transport difficulties (25%) and not wishing to burden family members (24.7%). By contrast, other studies have reported that women do not endorse discontinuation of screening mammography due to advancing age or poor health, but some may be receptive to reducing screening frequency on recommendation from their health care provider [ 46 , 51 ].

Use of Decision Aids (DAs) to improve knowledge and guide screening decision-making

Many women reported poor knowledge about the harms and benefits of screening with studies identifying an important role for DAs. These aids have been shown to be effective in improving knowledge of the harms and benefits of screening [ 45 , 54 , 55 ] including for women with low educational attainment; as compared to women with high educational attainment [ 47 ]. DAs can increase knowledge about screening [ 47 , 49 ] and may decrease the intention to continue screening after the recommended age [ 45 , 52 , 54 ]. They can be used by primary care providers to support a conversation about breast screening intention and reasons for discontinuing screening. In one pilot study undertaken in the US using a DA, 5 of the 8 women (62.5%) indicated they intended to continue to receive mammography; however, 3 participants planned to get them less often [ 45 ]. When asked whether they thought their physician would want them to get a mammogram, 80% said “yes” on pre-test; this figure decreased to 62.5% after exposure to the DA. This pilot study suggests that the use of a decision-aid may result in fewer women ≥ 75 years old continuing to screen for breast cancer [ 45 ].

Similar findings were evident in two studies drawing on the same data undertaken in the US [ 48 , 53 ]. Using a larger sample ( n = 283), women’s intentions to screen prior to a visit with their primary care provider and then again after exposure to the DA were compared. Results showed that 21.7% of women reduced their intention to be screened, 7.9% increased their intentions to be screened, and 70.4% did not change. Compared to those who had no change or increased their screening intentions, women who had a decrease in screening intention were significantly less likely to receive screening after 18 months. Generally, studies have shown that women aged 75 and older find DAs acceptable and helpful [ 47 , 48 , 49 , 55 ] and using them had the potential to impact on a women’s intention to screen [ 55 ].

Cadet and colleagues [ 49 ] explored the impact of educational attainment on the use of DAs. Results highlight that education moderates the utility of these aids; women with lower educational attainment were less likely to understand all the DA’s content (46.3% vs 67.5%; P < 0.001); had less knowledge of the benefits and harms of mammography (adjusted mean ± standard error knowledge score, 7.1 ± 0.3 vs 8.1 ± 0.3; p < 0.001); and were less likely to have their screening intentions impacted (adjusted percentage, 11.4% vs 19.4%; p = 0.01).

This scoping review summarises current knowledge regarding motivations and screening behaviours of women over 75 years. The findings suggest that awareness of the importance of breast cancer screening among women aged ≥ 75 years is high [ 23 , 46 , 49 ] and that many women wish to continue screening regardless of perceived health status or age. This highlights the importance of focusing on motivation and screening behaviours and the multiple factors that influence ongoing participation in breast screening programs.

The generally high regard attributed to screening among women aged ≥ 75 years presents a complex challenge for health professionals who are focused on potential harm (from available national and international guidelines) in ongoing screening for women beyond age 75 [ 18 , 20 , 57 ]. Included studies highlight that many women relied on the advice of health care providers regarding the benefits and harms when making the decision to continue breast screening [ 46 , 51 , 52 ], however there were some that did not [ 33 ]. Having a previous pattern of screening was noted as being more significant to ongoing intention than any other identified socio-demographic feature [ 56 ]. This is perhaps because women will not readily forgo health care practices that they have always considered important and that retain ongoing importance for the broader population.

For those women who had discontinued screening after the age of 74 it was apparent that the rationale for doing so was not often based on choice or receipt of information, but rather on factors that impact decision-making in relation to screening. These included no longer receiving an invitation to attend, transport difficulties and not wanting to be a burden on relatives or friends [ 23 , 46 , 51 ]. Ongoing receipt of invitations to screen was an important aspect of maintaining a capacity to choose [ 23 ]. This was particularly important for those women who had been regular screeners.

Women over 75 require more information to make decisions regarding screening [ 23 , 52 , 54 , 55 ], however health care providers must also be aware that the element of choice is important for older women. Having a capacity to choose avoids any notion of discrimination based on age, health status, gender or sociodemographic difference and acknowledges the importance of women retaining control over their health [ 23 ]. It was apparent that some women would choose to continue screening at a reduced frequency if this option was available and that women should have access to information facilitating self-referral [ 23 , 45 , 46 , 51 , 56 ].

Decision-making regarding ongoing breast cancer screening has been facilitated via the use of Decision Aids (DAs) within clinical settings [ 54 , 55 ]. While some studies suggest that women will make a decision regardless of health status, the use of DAs has impacted women’s decision to screen. While this may have limited benefit for those of lower educational attainment [ 48 ] they have been effective in improving knowledge relating to harms and benefits of screening particularly where they have been used to support a conversation with women about the value of screening [ 54 , 55 , 56 ].

Women have identified challenges in engaging in conversations with health care providers regarding ongoing screening, because providers frequently draw on projections of life expectancy and over-diagnosis [ 17 , 51 ]. As a result, these conversations about screening after age 75 years often do not occur [ 46 ]. It is likely that health providers may need more support and guidance in leading these conversations. This may be through the use of DAs or standardised checklists. It may be possible to incorporate these within existing health preventive measures for this age group. The potential for advice regarding ongoing breast cancer screening to be available outside of clinical settings may provide important pathways for conversations with women regarding health choices. Provision of information and advice in settings such as community based seniors groups [ 51 ] offers a potential platform to broaden conversations and align sources of information, not only with health professionals but amongst women themselves. This may help to address any misconception regarding eligibility and access to services [ 23 ]. It may also be aligned with other health promotion and lifestyle messages provided to this age group.

Limitations of the review

The searches that formed the basis of this review were carried in June 2022. Although the search was comprehensive, we have only captured those studies that were published in the included databases from 2009. There may have been other studies published outside of these periods. We also limited the search to studies published in English with full-text availability.

The emphasis of a scoping review is on comprehensive coverage and synthesis of the key findings, rather than on a particular standard of evidence and, consequently a quality assessment of the included studies was not undertaken. This has resulted in the inclusion of a wide range of study designs and data collection methods. It is important to note that three studies included in the review drew on the same sample of women (283 over > 75)[ 49 , 53 , 54 ]. The results of this review provide valuable insights into motivations and behaviours for breast cancer screening for older women, however they should be interpreted with caution given the specific methodological and geographical limitations.

Conclusion and recommendations

This scoping review highlighted a range of key motivations and behaviours in relation to breast cancer screening for women ≥ 75 years of age. The results provide some insight into how decisions about screening continuation after 74 are made and how informed decision-making can be supported. Specifically, this review supports the following suggestions for further research and policy direction:

Further research regarding breast cancer screening motivations and behaviours for women over 75 would provide valuable insight for health providers delivering services to women in this age group.

Health providers may benefit from the broader use of decision aids or structured checklists to guide conversations with women over 75 regarding ongoing health promotion/preventive measures.

Providing health-based information in non-clinical settings frequented by women in this age group may provide a broader reach of information and facilitate choices. This may help to reduce any perception of discrimination based on age, health status or socio-demographic factors.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study is included in this published article (see Table 2 above).

Cancer Australia, in their 2014 position statement, define “overdiagnosis” in the following way. ‘’Overdiagnosis’ from breast screening does not refer to error or misdiagnosis, but rather refers to breast cancer diagnosed by screening that would not otherwise have been diagnosed during a woman’s lifetime. “Overdiagnosis” includes all instances where cancers detected through screening (ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive breast cancer) might never have progressed to become symptomatic during a woman’s life, i.e., cancer that would not have been detected in the absence of screening. It is not possible to precisely predict at diagnosis, to which cancers overdiagnosis would apply.” (accessed 22. nd August 2022; https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/resources/position-statements/overdiagnosis-mammographic-screening ).

World Health Organization. Breast Cancer Geneva: WHO; 2021 [Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer#:~:text=Reducing%20global%20breast%20cancer%20mortality,and%20comprehensive%20breast%20cancer%20management .

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC Handbooks on Cancer Screening: Volume 15 Breast Cancer Geneva: IARC; 2016 [Available from: https://publications.iarc.fr/Book-And-Report-Series/Iarc-Handbooks-Of-Cancer-Prevention/Breast-Cancer-Screening-2016 .

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2021 [Available from: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/cancer-types/breast-cancer/statistics .

Breast Cancer Network Australia. Current breast cancer statistics in Australia 2020 [Available from: https://www.bcna.org.au/media/7111/bcna-2019-current-breast-cancer-statistics-in-australia-11jan2019.pdf .

Ren W, Chen M, Qiao Y, Zhao F. Global guidelines for breast cancer screening: A systematic review. The Breast. 2022;64:85–99.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, Penault-Llorca F, Poortmans P, Rubio IT, et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(8):1194–220.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hamashima C, Hattori M, Honjo S, Kasahara Y, Katayama T, Nakai M, et al. The Japanese guidelines for breast cancer screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46(5):482–92.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, Calhoun KE, Daly MB, Farrar WB, et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, version 3.2018, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Net. 2018;16(11):1362–89.

Article Google Scholar

He J, Chen W, Li N, Shen H, Li J, Wang Y, et al. China guideline for the screening and early detection of female breast cancer (2021, Beijing). Zhonghua Zhong liu za zhi [Chinese Journal of Oncology]. 2021;43(4):357–82.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Cancer Australia. Early detection of breast cancer 2021 [cited 2022 25 July]. Available from: https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/resources/position-statements/early-detection-breast-cancer .

Schünemann HJ, Lerda D, Quinn C, Follmann M, Alonso-Coello P, Rossi PG, et al. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis: A Synopsis of the European Breast Guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2019;172(1):46–56.

World Health Organization. WHO Position Paper on Mammography Screening Geneva WHO. 2016.

Google Scholar

Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Gulati R, Mariotto AB. Personalizing age of cancer screening cessation based on comorbid conditions: model estimates of harms and benefits. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:104.

Lee CS, Moy L, Joe BN, Sickles EA, Niell BL. Screening for Breast Cancer in Women Age 75 Years and Older. Am J Roentgenol. 2017;210(2):256–63.

Broeders M, Moss S, Nystrom L. The impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality in Europe: a review of observational studies. J Med Screen. 2012;19(suppl 1):14.

Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Etzioni R, Herzig A, Michaelson JS, Shih YCT, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 Guideline update from the American cancer society. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2015;314(15):1599–614.

Walter LC, Schonberg MA. Screening mammography in older women: a review. JAMA. 2014;311:1336.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Braithwaite D, Walter LC, Izano M, Kerlikowske K. Benefits and harms of screening mammography by comorbidity and age: a qualitative synthesis of observational studies and decision analyses. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:561.

Braithwaite D, Mandelblatt JS, Kerlikowske K. To screen or not to screen older women for breast cancer: a conundrum. Future Oncol. 2013;9(6):763–6.

Demb J, Abraham L, Miglioretti DL, Sprague BL, O’Meara ES, Advani S, et al. Screening Mammography Outcomes: Risk of Breast Cancer and Mortality by Comorbidity Score and Age. Jnci-Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2020;112(6):599–606.

Demb J, Akinyemiju T, Allen I, Onega T, Hiatt RA, Braithwaite D. Screening mammography use in older women according to health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:1987–97.

Qaseem A, Lin JS, Mustafa RA, Horwitch CA, Wilt TJ. Screening for Breast Cancer in Average-Risk Women: A Guidance Statement From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(8):547–60.

Collins K, Winslow M, Reed MW, Walters SJ, Robinson T, Madan J, et al. The views of older women towards mammographic screening: a qualitative and quantitative study. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(10):1461–7.

Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(9):605–13.

Hersch J, Jansen J, Barratt A, Irwig L, Houssami N, Howard K, et al. Women’s views on overdiagnosis in breast cancer screening: a qualitative study. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2013;346:f158.

De Gelder R, Heijnsdijk EAM, Van Ravesteyn NT, Fracheboud J, Draisma G, De Koning HJ. Interpreting overdiagnosis estimates in population-based mammography screening. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33(1):111–21.

Monticciolo DL, Helvie MA, Edward HR. Current issues in the overdiagnosis and overtreatment of breast cancer. Am J Roentgenol. 2018;210(2):285–91.

Shepardson LB, Dean L. Current controversies in breast cancer screening. Semin Oncol. 2020;47(4):177–81.

National Cancer Control Centre. Cancer incidence in Australia 2022 [Available from: https://ncci.canceraustralia.gov.au/diagnosis/cancer-incidence/cancer-incidence .

Austin JD, Shelton RC, Lee Argov EJ, Tehranifar P. Older Women’s Perspectives Driving Mammography Screening Use and Overuse: a Narrative Review of Mixed-Methods Studies. Current Epidemiology Reports. 2020;7(4):274–89.

Austin JD, Tehranifar P, Rodriguez CB, Brotzman L, Agovino M, Ziazadeh D, et al. A mixed-methods study of multi-level factors influencing mammography overuse among an older ethnically diverse screening population: implications for de-implementation. Implementation Science Communications. 2021;2(1):110.

Demb J, Allen I, Braithwaite D. Utilization of screening mammography in older women according to comorbidity and age: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):168.

Housten AJ, Pappadis MR, Krishnan S, Weller SC, Giordano SH, Bevers TB, et al. Resistance to discontinuing breast cancer screening in older women: A qualitative study. Psychooncology. 2018;27(6):1635–41.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco A, Khalil HAE, et al. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis 2020 [Available from: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL .

Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Khalil H, Larsen P, Marnie C, et al. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI evidence synthesis. 2022;20(4):953–68.

Fantom NJ, Serajuddin U. The World Bank’s classification of countries by income. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; 2016.

Book Google Scholar

BreastScreen Australia Evaluation Taskforce. BreastScreen Australia Evaluation. Evaluation final report: Screening Monograph No 1/2009. Canberra; Australia Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2009.

Nelson HD, Cantor A, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: a systematic review to update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation2016.

Woolf SH. The 2009 breast cancer screening recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2010;303(2):162–3.

Covidence systematic review software. [Internet]. Veritas-Health-Innovation 2020. Available from: https://www.covidence.org/ .

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):15.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Beckmeyer A, Smith RM, Miles L, Schonberg MA, Toland AE, Hirsch H. Pilot Evaluation of Patient-centered Survey Tools for Breast Cancer Screening Decision-making in Women 75 and Older. Health Behavior and Policy Review. 2020;7(1):13–8.

Brotzman LE, Shelton RC, Austin JD, Rodriguez CB, Agovino M, Moise N, et al. “It’s something I’ll do until I die”: A qualitative examination into why older women in the U.S. continue screening mammography. Canc Med. 2022;11(20):3854–62.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Cadet T, Pinheiro A, Karamourtopoulos M, Jacobson AR, Aliberti GM, Kistler CE, et al. Effects by educational attainment of a mammography screening patient decision aid for women aged 75 years and older. Cancer. 2021;127(23):4455–63.

Cadet T, Aliberti G, Karamourtopoulos M, Jacobson A, Gilliam EA, Primeau S, et al. Evaluation of a mammography decision aid for women 75 and older at risk for lower health literacy in a pretest-posttest trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(9):2344–50.

Cadet T, Aliberti G, Karamourtopoulos M, Jacobson A, Siska M, Schonberg MA. Modifying a mammography decision aid for older adult women with risk factors for low health literacy. Health Lit Res Prac. 2021;5(2):e78–90.

Gray N, Picone G. Evidence of Large-Scale Social Interactions in Mammography in the United States. Atl Econ J. 2018;46(4):441–57.

Hoover DS, Pappadis MR, Housten AJ, Krishnan S, Weller SC, Giordano SH, et al. Preferences for Communicating about Breast Cancer Screening Among Racially/Ethnically Diverse Older Women. Health Commun. 2019;34(7):702–6.

Salzman B, Bistline A, Cunningham A, Silverio A, Sifri R. Breast Cancer Screening Shared Decision-Making in Older African-American Women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(5):556–60.

PubMed Google Scholar

Schoenborn NL, Pinheiro A, Kistler CE, Schonberg MA. Association between Breast Cancer Screening Intention and Behavior in the Context of Screening Cessation in Older Women. Med Decis Making. 2021;41(2):240–4.

Schonberg MA, Kistler CE, Pinheiro A, Jacobson AR, Aliberti GM, Karamourtopoulos M, et al. Effect of a Mammography Screening Decision Aid for Women 75 Years and Older: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(6):831–42.

Schonberg MA, Hamel MB, Davis RB. Development and evaluation of a decision aid on mammography screening for women 75 years and older. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:417.

Eisinger F, Viguier J, Blay J-Y, Morère J-F, Coscas Y, Roussel C, et al. Uptake of breast cancer screening in women aged over 75years: a controversy to come? Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20(Suppl 1):S13-5.

Schonberg MA, Breslau ES, McCarthy EP. Targeting of Mammography Screening According to Life Expectancy in Women Aged 75 and Older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(3):388–95.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Ange Hayden-Johns (expert librarian) who assisted with the development of the search criteria and undertook the relevant searches and Tejashree Kangutkar who assisted with some of the Covidence work.

This work was supported by funding from the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (ID: Health/20–21/E21-10463).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Violet Vines Centre for Rural Health Research, La Trobe Rural Health School, La Trobe University, P.O. Box 199, Bendigo, VIC, 3552, Australia

Virginia Dickson-Swift, Joanne Adams & Evelien Spelten

Care Economy Research Institute, La Trobe University, Wodonga, Australia

Irene Blackberry

Olivia Newton-John Cancer Wellness and Research Centre, Austin Health, Melbourne, Australia

Carlene Wilson & Eva Yuen

Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, Melbourne University, Melbourne, Australia

Carlene Wilson

School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Australia

Institute for Health Transformation, Deakin University, Burwood, Australia

Centre for Quality and Patient Safety, Monash Health Partnership, Monash Health, Clayton, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

VDS conceived and designed the scoping review. VDS & JA developed the search strategy with librarian support, and all authors (VDS, JA, ES, IB, CW, EY) participated in the screening and data extraction stages and assisted with writing the review. All authors provided editorial support and read and approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joanne Adams .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent to participate was not required for this study.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was not required for this study.

Competing interest

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Dickson-Swift, V., Adams, J., Spelten, E. et al. Breast cancer screening motivation and behaviours of women aged over 75 years: a scoping review. BMC Women's Health 24 , 256 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03094-z

Download citation

Received : 06 September 2023

Accepted : 15 April 2024

Published : 24 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03094-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Breast cancer

- Mammography

- Older women

- Scoping review

BMC Women's Health

ISSN: 1472-6874

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS