Four of the biggest problems facing education—and four trends that could make a difference

Eduardo velez bustillo, harry a. patrinos.

In 2022, we published, Lessons for the education sector from the COVID-19 pandemic , which was a follow up to, Four Education Trends that Countries Everywhere Should Know About , which summarized views of education experts around the world on how to handle the most pressing issues facing the education sector then. We focused on neuroscience, the role of the private sector, education technology, inequality, and pedagogy.

Unfortunately, we think the four biggest problems facing education today in developing countries are the same ones we have identified in the last decades .

1. The learning crisis was made worse by COVID-19 school closures

Low quality instruction is a major constraint and prior to COVID-19, the learning poverty rate in low- and middle-income countries was 57% (6 out of 10 children could not read and understand basic texts by age 10). More dramatic is the case of Sub-Saharan Africa with a rate even higher at 86%. Several analyses show that the impact of the pandemic on student learning was significant, leaving students in low- and middle-income countries way behind in mathematics, reading and other subjects. Some argue that learning poverty may be close to 70% after the pandemic , with a substantial long-term negative effect in future earnings. This generation could lose around $21 trillion in future salaries, with the vulnerable students affected the most.

2. Countries are not paying enough attention to early childhood care and education (ECCE)

At the pre-school level about two-thirds of countries do not have a proper legal framework to provide free and compulsory pre-primary education. According to UNESCO, only a minority of countries, mostly high-income, were making timely progress towards SDG4 benchmarks on early childhood indicators prior to the onset of COVID-19. And remember that ECCE is not only preparation for primary school. It can be the foundation for emotional wellbeing and learning throughout life; one of the best investments a country can make.

3. There is an inadequate supply of high-quality teachers

Low quality teaching is a huge problem and getting worse in many low- and middle-income countries. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the percentage of trained teachers fell from 84% in 2000 to 69% in 2019 . In addition, in many countries teachers are formally trained and as such qualified, but do not have the minimum pedagogical training. Globally, teachers for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects are the biggest shortfalls.

4. Decision-makers are not implementing evidence-based or pro-equity policies that guarantee solid foundations

It is difficult to understand the continued focus on non-evidence-based policies when there is so much that we know now about what works. Two factors contribute to this problem. One is the short tenure that top officials have when leading education systems. Examples of countries where ministers last less than one year on average are plentiful. The second and more worrisome deals with the fact that there is little attention given to empirical evidence when designing education policies.

To help improve on these four fronts, we see four supporting trends:

1. Neuroscience should be integrated into education policies

Policies considering neuroscience can help ensure that students get proper attention early to support brain development in the first 2-3 years of life. It can also help ensure that children learn to read at the proper age so that they will be able to acquire foundational skills to learn during the primary education cycle and from there on. Inputs like micronutrients, early child stimulation for gross and fine motor skills, speech and language and playing with other children before the age of three are cost-effective ways to get proper development. Early grade reading, using the pedagogical suggestion by the Early Grade Reading Assessment model, has improved learning outcomes in many low- and middle-income countries. We now have the tools to incorporate these advances into the teaching and learning system with AI , ChatGPT , MOOCs and online tutoring.

2. Reversing learning losses at home and at school

There is a real need to address the remaining and lingering losses due to school closures because of COVID-19. Most students living in households with incomes under the poverty line in the developing world, roughly the bottom 80% in low-income countries and the bottom 50% in middle-income countries, do not have the minimum conditions to learn at home . These students do not have access to the internet, and, often, their parents or guardians do not have the necessary schooling level or the time to help them in their learning process. Connectivity for poor households is a priority. But learning continuity also requires the presence of an adult as a facilitator—a parent, guardian, instructor, or community worker assisting the student during the learning process while schools are closed or e-learning is used.

To recover from the negative impact of the pandemic, the school system will need to develop at the student level: (i) active and reflective learning; (ii) analytical and applied skills; (iii) strong self-esteem; (iv) attitudes supportive of cooperation and solidarity; and (v) a good knowledge of the curriculum areas. At the teacher (instructor, facilitator, parent) level, the system should aim to develop a new disposition toward the role of teacher as a guide and facilitator. And finally, the system also needs to increase parental involvement in the education of their children and be active part in the solution of the children’s problems. The Escuela Nueva Learning Circles or the Pratham Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) are models that can be used.

3. Use of evidence to improve teaching and learning

We now know more about what works at scale to address the learning crisis. To help countries improve teaching and learning and make teaching an attractive profession, based on available empirical world-wide evidence , we need to improve its status, compensation policies and career progression structures; ensure pre-service education includes a strong practicum component so teachers are well equipped to transition and perform effectively in the classroom; and provide high-quality in-service professional development to ensure they keep teaching in an effective way. We also have the tools to address learning issues cost-effectively. The returns to schooling are high and increasing post-pandemic. But we also have the cost-benefit tools to make good decisions, and these suggest that structured pedagogy, teaching according to learning levels (with and without technology use) are proven effective and cost-effective .

4. The role of the private sector

When properly regulated the private sector can be an effective education provider, and it can help address the specific needs of countries. Most of the pedagogical models that have received international recognition come from the private sector. For example, the recipients of the Yidan Prize on education development are from the non-state sector experiences (Escuela Nueva, BRAC, edX, Pratham, CAMFED and New Education Initiative). In the context of the Artificial Intelligence movement, most of the tools that will revolutionize teaching and learning come from the private sector (i.e., big data, machine learning, electronic pedagogies like OER-Open Educational Resources, MOOCs, etc.). Around the world education technology start-ups are developing AI tools that may have a good potential to help improve quality of education .

After decades asking the same questions on how to improve the education systems of countries, we, finally, are finding answers that are very promising. Governments need to be aware of this fact.

To receive weekly articles, sign-up here

Consultant, Education Sector, World Bank

Senior Adviser, Education

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

What education policy experts are watching for in 2022

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, daphna bassok , daphna bassok nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy @daphnabassok stephanie riegg cellini , stephanie riegg cellini nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy michael hansen , michael hansen senior fellow - brown center on education policy , the herman and george r. brown chair - governance studies @drmikehansen douglas n. harris , douglas n. harris nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy , professor and chair, department of economics - tulane university @douglasharris99 jon valant , and jon valant director - brown center on education policy , senior fellow - governance studies @jonvalant kenneth k. wong kenneth k. wong nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy.

January 7, 2022

Entering 2022, the world of education policy and practice is at a turning point. The ongoing coronavirus pandemic continues to disrupt the day-to-day learning for children across the nation, bringing anxiety and uncertainty to yet another year. Contentious school-board meetings attract headlines as controversy swirls around critical race theory and transgender students’ rights. The looming midterm elections threaten to upend the balance of power in Washington, with serious implications for the federal education landscape. All of these issues—and many more—will have a tremendous impact on students, teachers, families, and American society as a whole; whether that impact is positive or negative remains to be seen.

Below, experts from the Brown Center on Education Policy identify the education stories that they’ll be following in 2022, providing analysis on how these issues could shape the learning landscape for the next 12 months—and possibly well into the future.

I will also be watching the Department of Education’s negotiated rulemaking sessions and following any subsequent regulatory changes to federal student-aid programs. I expect to see changes to income-driven repayment plans and will be monitoring debates over regulations governing institutional and programmatic eligibility for federal student-loan programs. Notably, the Department of Education will be re-evaluating Gainful Employment regulations—put in place by the Obama administration and rescinded by the Trump administration—which tied eligibility for federal funding to graduates’ earnings and debt.

But the biggest and most concerning hole has been in the substitute teacher force —and the ripple effects on school communities have been broad and deep. Based on personal communications with Nicola Soares, president of Kelly Education , the largest education staffing provider in the country, the pandemic is exacerbating several problematic trends that have been quietly simmering for years. These are: (1) a growing reliance on long-term substitutes to fill permanent teacher positions; (2) a shrinking supply of qualified individuals willing to fill short-term substitute vacancies; and, (3) steadily declining fill rates for schools’ substitute requests. Many schools in high-need settings have long faced challenges with adequate, reliable substitutes, and the pandemic has turned these localized trouble spots into a widespread catastrophe. Though federal pandemic-relief funds could be used to meet the short-term weakness in the substitute labor market (and mainline teacher compensation, too ), this is an area where we sorely need more research and policy solutions for a permanent fix.

First, what’s to come of the vaccine for ages 0-4? This is now the main impediment to resuming in-person activity. This is the only large group that currently cannot be vaccinated. Also, outbreaks are triggering day-care closures, which has a significant impact on parents (especially mothers), including teachers and other school staff.

Second, will schools (and day cares) require the vaccine for the fall of 2022? Kudos to my hometown of New Orleans, which still appears to be the nation’s only district to require vaccination. Schools normally require a wide variety of other vaccines, and the COVID-19 vaccines are very effective. However, this issue is unfortunately going to trigger a new round of intense political conflict and opposition that will likely delay the end of the pandemic.

Third, will we start to see signs of permanent changes in schooling a result of COVID-19? In a previous post on this blog, I proposed some possibilities. There are some real opportunities before us, but whether we can take advantage of them depends on the first two questions. We can’t know about these long-term effects on schooling until we address the COVID-19 crisis so that people get beyond survival mode and start planning and looking ahead again. I’m hopeful, though not especially optimistic, that we’ll start to see this during 2022.

The CTC and universal pre-K top my list for 2022, but it’s a long list. I’ll also be watching the Supreme Court’s ruling on vouchers in Carson v. Makin , how issues like critical race theory and detracking play into the 2022 elections, and whether we start to see more signs of school/district innovation in response to COVID-19 and the recovery funds that followed.

Electoral dynamics will affect several important issues: the selection of state superintendents; the use of American Rescue Plan funds; the management of safe return to in-person learning for students; the integration of racial justice and diversity into curriculum; the growth of charter schools; and, above all, the extent to which education issues are leveraged to polarize rather than heal the growing divisions among the American public.

Early Childhood Education Education Policy Higher Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

Sofoklis Goulas, Isabelle Pula

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Elizabeth D. Steiner, Ashley Woo

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Footnote leads to exploration of start of for-profit prisons in N.Y.

Should NATO step up role in Russia-Ukraine war?

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

How covid taught america about inequity in education.

Harvard Correspondent

Remote learning turned spotlight on gaps in resources, funding, and tech — but also offered hints on reform

“Unequal” is a multipart series highlighting the work of Harvard faculty, staff, students, alumni, and researchers on issues of race and inequality across the U.S. This part looks at how the pandemic called attention to issues surrounding the racial achievement gap in America.

The pandemic has disrupted education nationwide, turning a spotlight on existing racial and economic disparities, and creating the potential for a lost generation. Even before the outbreak, students in vulnerable communities — particularly predominately Black, Indigenous, and other majority-minority areas — were already facing inequality in everything from resources (ranging from books to counselors) to student-teacher ratios and extracurriculars.

The additional stressors of systemic racism and the trauma induced by poverty and violence, both cited as aggravating health and wellness as at a Weatherhead Institute panel , pose serious obstacles to learning as well. “Before the pandemic, children and families who are marginalized were living under such challenging conditions that it made it difficult for them to get a high-quality education,” said Paul Reville, founder and director of the Education Redesign Lab at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (GSE).

Educators hope that the may triggers a broader conversation about reform and renewed efforts to narrow the longstanding racial achievement gap. They say that research shows virtually all of the nation’s schoolchildren have fallen behind, with students of color having lost the most ground, particularly in math. They also note that the full-time reopening of schools presents opportunities to introduce changes and that some of the lessons from remote learning, particularly in the area of technology, can be put to use to help students catch up from the pandemic as well as to begin to level the playing field.

The disparities laid bare by the COVID-19 outbreak became apparent from the first shutdowns. “The good news, of course, is that many schools were very fast in finding all kinds of ways to try to reach kids,” said Fernando M. Reimers , Ford Foundation Professor of the Practice in International Education and director of GSE’s Global Education Innovation Initiative and International Education Policy Program. He cautioned, however, that “those arrangements don’t begin to compare with what we’re able to do when kids could come to school, and they are particularly deficient at reaching the most vulnerable kids.” In addition, it turned out that many students simply lacked access.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right. You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it,” says Fernando Reimers of the Graduate School of Education.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

The rate of limited digital access for households was at 42 percent during last spring’s shutdowns, before drifting down to about 31 percent this fall, suggesting that school districts improved their adaptation to remote learning, according to an analysis by the UCLA Center for Neighborhood Knowledge of U.S. Census data. (Indeed, Education Week and other sources reported that school districts around the nation rushed to hand out millions of laptops, tablets, and Chromebooks in the months after going remote.)

The report also makes clear the degree of racial and economic digital inequality. Black and Hispanic households with school-aged children were 1.3 to 1.4 times as likely as white ones to face limited access to computers and the internet, and more than two in five low-income households had only limited access. It’s a problem that could have far-reaching consequences given that young students of color are much more likely to live in remote-only districts.

“We’re beginning to understand that technology is a basic right,” said Reimers. “You cannot participate in society in the 21st century without access to it.” Too many students, he said, “have no connectivity. They have no devices, or they have no home circumstances that provide them support.”

The issues extend beyond the technology. “There is something wonderful in being in contact with other humans, having a human who tells you, ‘It’s great to see you. How are things going at home?’” Reimers said. “I’ve done 35 case studies of innovative practices around the world. They all prioritize social, emotional well-being. Checking in with the kids. Making sure there is a touchpoint every day between a teacher and a student.”

The difference, said Reville, is apparent when comparing students from different economic circumstances. Students whose parents “could afford to hire a tutor … can compensate,” he said. “Those kids are going to do pretty well at keeping up. Whereas, if you’re in a single-parent family and mom is working two or three jobs to put food on the table, she can’t be home. It’s impossible for her to keep up and keep her kids connected.

“If you lose the connection, you lose the kid.”

“COVID just revealed how serious those inequities are,” said GSE Dean Bridget Long , the Saris Professor of Education and Economics. “It has disproportionately hurt low-income students, students with special needs, and school systems that are under-resourced.”

This disruption carries throughout the education process, from elementary school students (some of whom have simply stopped logging on to their online classes) through declining participation in higher education. Community colleges, for example, have “traditionally been a gateway for low-income students” into the professional classes, said Long, whose research focuses on issues of affordability and access. “COVID has just made all of those issues 10 times worse,” she said. “That’s where enrollment has fallen the most.”

In addition to highlighting such disparities, these losses underline a structural issue in public education. Many schools are under-resourced, and the major reason involves sources of school funding. A 2019 study found that predominantly white districts got $23 billion more than their non-white counterparts serving about the same number of students. The discrepancy is because property taxes are the primary source of funding for schools, and white districts tend to be wealthier than those of color.

The problem of resources extends beyond teachers, aides, equipment, and supplies, as schools have been tasked with an increasing number of responsibilities, from the basics of education to feeding and caring for the mental health of both students and their families.

“You think about schools and academics, but what COVID really made clear was that schools do so much more than that,” said Long. A child’s school, she stressed “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care.”

“You think about schools and academics” … but a child’s school “is social, emotional support. It’s safety. It’s the food system. It is health care,” stressed GSE Dean Bridget Long.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

This safety net has been shredded just as more students need it. “We have 400,000 deaths and those are disproportionately affecting communities of color,” said Long. “So you can imagine the kids that are in those households. Are they able to come to school and learn when they’re dealing with this trauma?”

The damage is felt by the whole families. In an upcoming paper, focusing on parents of children ages 5 to 7, Cindy H. Liu, director of Harvard Medical School’s Developmental Risk and Cultural Disparities Laboratory , looks at the effects of COVID-related stress on parent’ mental health. This stress — from both health risks and grief — “likely has ramifications for those groups who are disadvantaged, particularly in getting support, as it exacerbates existing disparities in obtaining resources,” she said via email. “The unfortunate reality is that the pandemic is limiting the tangible supports [like childcare] that parents might actually need.”

Educators are overwhelmed as well. “Teachers are doing a phenomenal job connecting with students,” Long said about their performance online. “But they’ve lost the whole system — access to counselors, access to additional staff members and support. They’ve lost access to information. One clue is that the reporting of child abuse going down. It’s not that we think that child abuse is actually going down, but because you don’t have a set of adults watching and being with kids, it’s not being reported.”

The repercussions are chilling. “As we resume in-person education on a normal basis, we’re dealing with enormous gaps,” said Reville. “Some kids will come back with such educational deficits that unless their schools have a very well thought-out and effective program to help them catch up, they will never catch up. They may actually drop out of school. The immediate consequences of learning loss and disengagement are going to be a generation of people who will be less educated.”

There is hope, however. Just as the lockdown forced teachers to improvise, accelerating forms of online learning, so too may the recovery offer options for educational reform.

The solutions, say Reville, “are going to come from our community. This is a civic problem.” He applauded one example, the Somerville, Mass., public library program of outdoor Wi-Fi “pop ups,” which allow 24/7 access either through their own or library Chromebooks. “That’s the kind of imagination we need,” he said.

On a national level, he points to the creation of so-called “Children’s Cabinets.” Already in place in 30 states, these nonpartisan groups bring together leaders at the city, town, and state levels to address children’s needs through schools, libraries, and health centers. A July 2019 “ Children’s Cabinet Toolkit ” on the Education Redesign Lab site offers guidance for communities looking to form their own, with sample mission statements from Denver, Minneapolis, and Fairfax, Va.

Already the Education Redesign Lab is working on even more wide-reaching approaches. In Tennessee, for example, the Metro Nashville Public Schools has launched an innovative program, designed to provide each student with a personalized education plan. By pairing these students with school “navigators” — including teachers, librarians, and instructional coaches — the program aims to address each student’s particular needs.

“This is a chance to change the system,” said Reville. “By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now.”

“Students have different needs,” agreed Long. “We just have to get a better understanding of what we need to prioritize and where students are” in all aspects of their home and school lives.

“By and large, our school systems are organized around a factory model, a one-size-fits-all approach. That wasn’t working very well before, and it’s working less well now,” says Paul Reville of the GSE.

Already, educators are discussing possible responses. Long and GSE helped create The Principals’ Network as one forum for sharing ideas, for example. With about 1,000 members, and multiple subgroups to address shared community issues, some viable answers have begun to emerge.

“We are going to need to expand learning time,” said Long. Some school systems, notably Texas’, already have begun discussing extending the school year, she said. In addition, Long, an internationally recognized economist who is a member of the National Academy of Education and the MDRC board, noted that educators are exploring innovative ways to utilize new tools like Zoom, even when classrooms reopen.

“This is an area where technology can help supplement what students are learning, giving them extra time — learning time, even tutoring time,” Long said.

Reimers, who serves on the UNESCO Commission on the Future of Education, has been brainstorming solutions that can be applied both here and abroad. These include urging wealthier countries to forgive loans, so that poorer countries do not have to cut back on basics such as education, and urging all countries to keep education a priority. The commission and its members are also helping to identify good practices and share them — globally.

Innovative uses of existing technology can also reach beyond traditional schooling. Reimers cites the work of a few former students who, working with Harvard Global Education Innovation Initiative, HundrED , the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills , and the World Bank Group Education Global Practice, focused on podcasts to reach poor students in Colombia.

They began airing their math and Spanish lessons via the WhatsApp app, which was widely accessible. “They were so humorous that within a week, everyone was listening,” said Reimers. Soon, radio stations and other platforms began airing the 10-minute lessons, reaching not only children who were not in school, but also their adult relatives.

Share this article

You might like.

Historian traces 19th-century murder case that brought together historical figures, helped shape American thinking on race, violence, incarceration

National security analysts outline stakes ahead of July summit

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

Six receive honorary degrees

Harvard recognizes educator, conductor, theoretical physicist, advocate for elderly, writer, and Nobel laureate

Everything counts!

New study finds step-count and time are equally valid in reducing health risks

Bridging social distance, embracing uncertainty, fighting for equity

Student Commencement speeches to tap into themes faced by Class of 2024

- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

The state of the global education crisis, a path to recovery.

The global disruption to education caused by the COVD-19 pandemic is without parallel and the effects on learning are severe. The crisis brought education systems across the world to a halt, with school closures affecting more than 1.6 billion learners. While nearly every country in the world offered remote learning opportunities for students, the quality and reach of such initiatives varied greatly and were at best partial substitutes for in-person learning. Now, 21 months later, schools remain closed for millions of children and youth, and millions more are at risk of never returning to education. Evidence of the detrimental impacts of school closures on children’s learning offer a harrowing reality: learning losses are substantial, with the most marginalized children and youth often disproportionately affected.

The State of the Global Education Crisis: A Path to Recovery charts a path out of the global education crisis and towards building more effective, equitable and resilient education systems.

Files available for download

Related topics, more to explore, unicef goodwill ambassador millie bobby brown calls for ‘a world where periods don’t hold us back’ in new video for menstrual hygiene day.

10 Fast Facts: Menstrual health in schools

UNICEF Chief Catherine Russell meets Pope Francis in a call for peace and protection of children affected by poverty, conflict and climate crises

Shipment of newest malaria vaccine, R21, to Central African Republic marks latest milestone for child survival

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

Public education is facing a crisis of epic proportions

How politics and the pandemic put schools in the line of fire

A previous version of this story incorrectly said that 39 percent of American children were on track in math. That is the percentage performing below grade level.

Test scores are down, and violence is up . Parents are screaming at school boards , and children are crying on the couches of social workers. Anger is rising. Patience is falling.

For public schools, the numbers are all going in the wrong direction. Enrollment is down. Absenteeism is up. There aren’t enough teachers, substitutes or bus drivers. Each phase of the pandemic brings new logistics to manage, and Republicans are planning political campaigns this year aimed squarely at failings of public schools.

Public education is facing a crisis unlike anything in decades, and it reaches into almost everything that educators do: from teaching math, to counseling anxious children, to managing the building.

Political battles are now a central feature of education, leaving school boards, educators and students in the crosshairs of culture warriors. Schools are on the defensive about their pandemic decision-making, their curriculums, their policies regarding race and racial equity and even the contents of their libraries. Republicans — who see education as a winning political issue — are pressing their case for more “parental control,” or the right to second-guess educators’ choices. Meanwhile, an energized school choice movement has capitalized on the pandemic to promote alternatives to traditional public schools.

“The temperature is way up to a boiling point,” said Nat Malkus, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative-leaning think tank. “If it isn’t a crisis now, you never get to crisis.”

Experts reach for comparisons. The best they can find is the earthquake following Brown v. Board of Education , when the Supreme Court ordered districts to desegregate and White parents fled from their cities’ schools. That was decades ago.

Today, the cascading problems are felt acutely by the administrators, teachers and students who walk the hallways of public schools across the country. Many say they feel unprecedented levels of stress in their daily lives.

Remote learning, the toll of illness and death, and disruptions to a dependable routine have left students academically behind — particularly students of color and those from poor families. Behavior problems ranging from inability to focus in class all the way to deadly gun violence have gripped campuses. Many students and teachers say they are emotionally drained, and experts predict schools will be struggling with the fallout for years to come.

Teresa Rennie, an eighth-grade math and science teacher in Philadelphia, said in 11 years of teaching, she has never referred this many children to counseling.

“So many students are needy. They have deficits academically. They have deficits socially,” she said. Rennie said that she’s drained, too. “I get 45 minutes of a prep most days, and a lot of times during that time I’m helping a student with an assignment, or a child is crying and I need to comfort them and get them the help they need. Or there’s a problem between two students that I need to work with. There’s just not enough time.”

Many wonder: How deep is the damage?

Learning lost

At the start of the pandemic, experts predicted that students forced into remote school would pay an academic price. They were right.

“The learning losses have been significant thus far and frankly I’m worried that we haven’t stopped sinking,” said Dan Goldhaber, an education researcher at the American Institutes for Research.

Some of the best data come from the nationally administered assessment called i-Ready, which tests students three times a year in reading and math, allowing researchers to compare performance of millions of students against what would be expected absent the pandemic. It found significant declines, especially among the youngest students and particularly in math.

The low point was fall 2020, when all students were coming off a spring of chaotic, universal remote classes. By fall 2021 there were some improvements, but even then, academic performance remained below historic norms.

Take third grade, a pivotal year for learning and one that predicts success going forward. In fall 2021, 38 percent of third-graders were below grade level in reading, compared with 31 percent historically. In math, 39 percent of students were below grade level, vs. 29 percent historically.

Damage was most severe for students from the lowest-income families, who were already performing at lower levels.

A McKinsey & Co. study found schools with majority-Black populations were five months behind pre-pandemic levels, compared with majority-White schools, which were two months behind. Emma Dorn, a researcher at McKinsey, describes a “K-shaped” recovery, where kids from wealthier families are rebounding and those in low-income homes continue to decline.

“Some students are recovering and doing just fine. Other people are not,” she said. “I’m particularly worried there may be a whole cohort of students who are disengaged altogether from the education system.”

A hunt for teachers, and bus drivers

Schools, short-staffed on a good day, had little margin for error as the omicron variant of the coronavirus swept over the country this winter and sidelined many teachers. With a severe shortage of substitutes, teachers had to cover other classes during their planning periods, pushing prep work to the evenings. San Francisco schools were so strapped that the superintendent returned to the classroom on four days this school year to cover middle school math and science classes. Classes were sometimes left unmonitored or combined with others into large groups of unglorified study halls.

“The pandemic made an already dire reality even more devastating,” said Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, referring to the shortages.

In 2016, there were 1.06 people hired for every job listing. That figure has steadily dropped, reaching 0.59 hires for each opening last year, Bureau of Labor Statistics data show. In 2013, there were 557,320 substitute teachers, the BLS reported. In 2020, the number had fallen to 415,510. Virtually every district cites a need for more subs.

It’s led to burnout as teachers try to fill in the gaps.

“The overall feelings of teachers right now are ones of just being exhausted, beaten down and defeated, and just out of gas. Expectations have been piled on educators, even before the pandemic, but nothing is ever removed,” said Jennifer Schlicht, a high school teacher in Olathe, Kan., outside Kansas City.

Research shows the gaps in the number of available educators are most acute in areas including special education and educators who teach English language learners, as well as substitutes. And all school year, districts have been short on bus drivers , who have been doubling up routes, and forcing late school starts and sometimes cancellations for lack of transportation.

Many educators predict that fed-up teachers will probably quit, exacerbating the problem. And they say political attacks add to the burnout. Teachers are under scrutiny over lesson plans, and critics have gone after teachers unions, which for much of the pandemic demanded remote learning.

“It’s just created an environment that people don’t want to be part of anymore,” said Daniel A. Domenech, executive director of AASA, The School Superintendents Association. “People want to take care of kids, not to be accused and punished and criticized.”

Falling enrollment

Traditional public schools educate the vast majority of American children, but enrollment has fallen, a worrisome trend that could have lasting repercussions. Enrollment in traditional public schools fell to less than 49.4 million students in fall 2020 , a 2.7 percent drop from a year earlier .

National data for the current school year is not yet available. But if the trend continues, that will mean less money for public schools as federal and state funding are both contingent on the number of students enrolled. For now, schools have an infusion of federal rescue money that must be spent by 2024.

Some students have shifted to private or charter schools. A rising number , especially Black families , opted for home schooling. And many young children who should have been enrolling in kindergarten delayed school altogether. The question has been: will these students come back?

Some may not. Preliminary data for 19 states compiled by Nat Malkus, of the American Enterprise Institute, found seven states where enrollment dropped in fall 2020 and then dropped even further in 2021. His data show 12 states that saw declines in 2020 but some rebounding in 2021 — though not one of them was back to 2019 enrollment levels.

Joshua Goodman, associate professor of education and economics at Boston University, studied enrollment in Michigan schools and found high-income, White families moved to private schools to get in-person school. Far more common, though, were lower-income Black families shifting to home schooling or other remote options because they were uncomfortable with the health risks of in person.

“Schools were damned if they did, and damned if they didn’t,” Goodman said.

At the same time, charter schools, which are privately run but publicly funded, saw enrollment increase by 7 percent, or nearly 240,000 students, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. There’s also been a surge in home schooling. Private schools saw enrollment drop slightly in 2020-21 but then rebound this academic year, for a net growth of 1.7 percent over two years, according to the National Association of Independent Schools, which represents 1,600 U.S. schools.

Absenteeism on the rise

Even if students are enrolled, they won’t get much schooling if they don’t show up.

Last school year, the number of students who were chronically absent — meaning they have missed more than 10 percent of school days — nearly doubled from before the pandemic, according to data from a variety of states and districts studied by EveryDay Labs, a company that works with districts to improve attendance.

This school year, the numbers got even worse.

In Connecticut, for instance, the number of chronically absent students soared from 12 percent in 2019-20 to 20 percent the next year to 24 percent this year, said Emily Bailard, chief executive of the company. In Oakland, Calif., they went from 17.3 percent pre-pandemic to 19.8 percent last school year to 43 percent this year. In Pittsburgh, chronic absences stayed where they were last school year at about 25 percent, then shot up to 45 percent this year.

“We all expected that this year would look much better,” Bailard said. One explanation for the rise may be that schools did not keep careful track of remote attendance last year and the numbers understated the absences then, she said.

The numbers were the worst for the most vulnerable students. This school year in Connecticut, for instance, 24 percent of all students were chronically absent, but the figure topped 30 percent for English-learners, students with disabilities and those poor enough to qualify for free lunch. Among students experiencing homelessness, 56 percent were chronically absent.

Fights and guns

Schools are open for in-person learning almost everywhere, but students returned emotionally unsettled and unable to conform to normally accepted behavior. At its most benign, teachers are seeing kids who cannot focus in class, can’t stop looking at their phones, and can’t figure out how to interact with other students in all the normal ways. Many teachers say they seem younger than normal.

Amy Johnson, a veteran teacher in rural Randolph, Vt., said her fifth-graders had so much trouble being together that the school brought in a behavioral specialist to work with them three hours each week.

“My students are not acclimated to being in the same room together,” she said. “They don’t listen to each other. They cannot interact with each other in productive ways. When I’m teaching I might have three or five kids yelling at me all at the same time.”

That loss of interpersonal skills has also led to more fighting in hallways and after school. Teachers and principals say many incidents escalate from small disputes because students lack the habit of remaining calm. Many say the social isolation wrought during remote school left them with lower capacity to manage human conflict.

Just last week, a high-schooler in Los Angeles was accused of stabbing another student in a school hallway, police on the big island of Hawaii arrested seven students after an argument escalated into a fight, and a Baltimore County, Md., school resource officer was injured after intervening in a fight during the transition between classes.

There’s also been a steep rise in gun violence. In 2021, there were at least 42 acts of gun violence on K-12 campuses during regular hours, the most during any year since at least 1999, according to a Washington Post database . The most striking of 2021 incidents was the shooting in Oxford, Mich., that killed four. There have been already at least three shootings in 2022.

Back to school has brought guns, fighting and acting out

The Center for Homeland Defense and Security, which maintains its own database of K-12 school shootings using a different methodology, totaled nine active shooter incidents in schools in 2021, in addition to 240 other incidents of gunfire on school grounds. So far in 2022, it has recorded 12 incidents. The previous high, in 2019, was 119 total incidents.

David Riedman, lead researcher on the K-12 School Shooting Database, points to four shootings on Jan. 19 alone, including at Anacostia High School in D.C., where gunshots struck the front door of the school as a teen sprinted onto the campus, fleeing a gunman.

Seeing opportunity

Fueling the pressure on public schools is an ascendant school-choice movement that promotes taxpayer subsidies for students to attend private and religious schools, as well as publicly funded charter schools, which are privately run. Advocates of these programs have seen the public system’s woes as an excellent opportunity to push their priorities.

EdChoice, a group that promotes these programs, tallies seven states that created new school choice programs last year. Some are voucher-type programs where students take some of their tax dollars with them to private schools. Others offer tax credits for donating to nonprofit organizations, which give scholarships for school expenses. Another 15 states expanded existing programs, EdChoice says.

The troubles traditional schools have had managing the pandemic has been key to the lobbying, said Michael McShane, director of national research for EdChoice. “That is absolutely an argument that school choice advocates make, for sure.”

If those new programs wind up moving more students from public to private systems, that could further weaken traditional schools, even as they continue to educate the vast majority of students.

Kevin G. Welner, director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado, who opposes school choice programs, sees the surge of interest as the culmination of years of work to undermine public education. He is both impressed by the organization and horrified by the results.

“I wish that organizations supporting public education had the level of funding and coordination that I’ve seen in these groups dedicated to its privatization,” he said.

A final complication: Politics

Rarely has education been such a polarizing political topic.

Republicans, fresh off Glenn Youngkin’s victory in the Virginia governor’s race, have concluded that key to victory is a push for parental control and “parents rights.” That’s a nod to two separate topics.

First, they are capitalizing on parent frustrations over pandemic policies, including school closures and mandatory mask policies. The mask debate, which raged at the start of the school year, got new life this month after Youngkin ordered Virginia schools to allow students to attend without face coverings.

The notion of parental control also extends to race, and objections over how American history is taught. Many Republicans also object to school districts’ work aimed at racial equity in their systems, a basket of policies they have dubbed critical race theory. Critics have balked at changes in admissions to elite school in the name of racial diversity, as was done in Fairfax, Va. , and San Francisco ; discussion of White privilege in class ; and use of the New York Times’s “1619 Project,” which suggests slavery and racism are at the core of American history.

“Everything has been politicized,” said Domenech, of AASA. “You’re beside yourself saying, ‘How did we ever get to this point?’”

Part of the challenge going forward is that the pandemic is not over. Each time it seems to be easing, it returns with a variant vengeance, forcing schools to make politically and educationally sensitive decisions about the balance between safety and normalcy all over again.

At the same time, many of the problems facing public schools feed on one another. Students who are absent will probably fall behind in learning, and those who fall behind are likely to act out.

A similar backlash exists regarding race. For years, schools have been under pressure to address racism in their systems and to teach it in their curriculums, pressure that intensified after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Many districts responded, and that opened them up to countervailing pressures from those who find schools overly focused on race.

Some high-profile boosters of public education are optimistic that schools can move past this moment. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona last week promised, “It will get better.” Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, said, “If we can rebuild community-education relations, if we can rebuild trust, public education will not only survive but has a real chance to thrive.”

But the path back is steep, and if history is a guide, the wealthiest schools will come through reasonably well, while those serving low-income communities will struggle. Steve Matthews, superintendent of the 6,900-student Novi Community School District in Michigan, just northwest of Detroit, said his district will probably face a tougher road back than wealthier nearby districts that are, for instance, able to pay teachers more.

“Resource issues. Trust issues. De-professionalization of teaching is making it harder to recruit teachers,” he said. “A big part of me believes schools are in a long-term crisis.”

Valerie Strauss contributed to this report.

The pandemic’s impact on education

The latest: Updated coronavirus booster shots are now available for children as young as 5 . To date, more than 10.5 million children have lost one or both parents or caregivers during the coronavirus pandemic.

In the classroom: Amid a teacher shortage, states desperate to fill teaching jobs have relaxed job requirements as staffing crises rise in many schools . American students’ test scores have even plummeted to levels unseen for decades. One D.C. school is using COVID relief funds to target students on the verge of failure .

Higher education: College and university enrollment is nowhere near pandemic level, experts worry. ACT and SAT testing have rebounded modestly since the massive disruptions early in the coronavirus pandemic, and many colleges are also easing mask rules .

DMV news: Most of Prince George’s students are scoring below grade level on district tests. D.C. Public School’s new reading curriculum is designed to help improve literacy among the city’s youngest readers.

The Challenges of Curriculum Design

- Posted June 1, 2022

- By Jill Anderson

- K-12 System Leadership

- Learning Design and Instruction

Ed.L.D. class marshal Simone Wright, Ed.L.D.’22, refers to her in education as a calling. And her decision to pursue her calling, she says, is because education touches everyone and can be transforming for students — especially for Black students — in ways that can lead to an improved society.

“I really needed the time to think about what it meant to drive change at scale,” she says of being part of the Ed.L.D. Program. “The opportunity to cultivate the skills to lead at scale and influence change. And some of that was the network, but some of it was also really leaning into the opportunity to think a little bit more intentionally about what change I wanted to have.”

The former Teach For America teacher, who spent years working in the public schools and charter schools in various capacities, leaned fully into the experience, especially her residency at the New York City Department of Education (NYCDOE) as the special adviser to the chief academic officer. She longed for a project that would allow her to lead among different constituenst both inside and outside of the NYCDOE. When the NYCDOE undertook the development of a rigorous, inclusive, and affirming K–12 English Language Arts and Math Curriculum — one that would reflect the diverse experience of the million plus students it served — Wright jumped at the opportunity.

“The project really did push me to bridge the lines of thinking around how the community perspective could inform a teaching and learning strategy and practices,” she says.

While she did not think that the core of her work at NYCDOE would disrupt the process in which the education space traditionally develops curriculum, she admits that going through the design process, she has realized the value and need for a more user-centered approach to curriculum design.

Here, Wright discusses working at NYCDOE, the challenges of curriculum design, and what it means for a curriculum to be truly culturally responsive.

Why curriculum design? When I started my residency, I was involved in everything. New York City was preparing to welcome every student back to in-person learning and had devised a strategy around academic recovery to leverage the ESSER dollars to really accelerate learning as we returned to full in person learning. One of the components of this plan was to develop a culturally responsive Math and ELA curricula that was reflective of the diverse experiences of our students across New York City. I knew that as an aspiring Chief Academic Officer that this particular project would further prepare me to lead teaching and learning at scale, but I also saw this project as a place where there was some additional capacity needed.

Everyone was kind of talking about culturally responsive curriculum and I believed in the notion of it, but I didn't fully understand what we meant when we said it. I think that curiosity really pushed me in a way to lean in and learn more.

How did you approach the need for a culturally responsive curriculum? The notion of us building our own curriculum was rooted in the real call to action from different constituents for our student experiences being reflected in their learning. There wasn't a product already built by a vendor that indicated the rich diverse experiences of the students and communities across New York City. As mentioned above, this curriculum was a part of our larger academic recovery strategy, and we believed that after almost two years of hybrid and blended learning, this was really an opportunity to reimagine the student learning experience. While representation of our students and community experiences that are historically underserved was a key driver to this work, we saw this as an opportunity to provide educators with a high-quality tool that could support them with increasing student outcomes for our most historically underserved student populations — Black and Brown students, multilingual learners, and student with disabilities. Curriculum has not always been explicitly designed to equip teachers to meet the needs of each student, particularly our most vulnerable.

How did this play out? We designed a participatory curriculum design strategy, leading with engagement. Historically engagement when it comes to curriculum usually only entails educators and typically engages educators after the core components have been developed. We developed an approach to design curricula that is responsive to the insights of students, families, educators, and community members. We launched citywide engagement where we asked them, "What are your most meaningful learning experiences?" "What would you want to see in this curriculum?" Other core components of design included continuous loops and cycles of feedback with different constituents to ensure the curricula was responsive to their feedback and high-quality (e.g. standards aligned etc.).

It’s interesting to think of curriculum design happening within a community. What did you hear from parents and the community? There was a true call to action around ensuring learning experience really prepared students for the skills they would need to be successful post-K–12, both cognitively and experientially.

There was a lot about how do you ensure school prepares students to navigate the world and ensuring that learning experience really set them up with a level of like thinking required to be successful.

What does a more user-centered approach to curriculum design look like? I think it starts with really understanding the end user's experience with curriculum, specifically students and teachers. Curriculum is a core tool to really ensuring that teachers have the knowledge and skill to effectively ensure each student is learning. The teacher facing side is one piece of it, but we actually have to look at how curriculum is informing student performance.

We have to consider, how does curriculum inform the actual student experience in the classroom? Are students engaged? Can they explain what they're learning? Do students feel comfortable asking questions? Are they empowered to really challenge the ideas or add to the ideas that are coming up in classrooms? Curriculum can be one of the foundational tools to informing a rich classroom experience. If we cannot understand the educator experience — what's working, what's not — we can't strengthen the effectiveness of this tool.

Once NYCDOE announced that we were building out this curriculum, it attracted a lot of attention from different stakeholders across the ecosystem. We were able to leverage a lot of thought partners in helping us think through this idea of a more user-centered curriculum that really lifted the perspectives of students, families, educators, community members and other constituents, to strengthen a critical and foundational element of teaching and learning. There’s research and education reports that talk about how curriculum is actually one of the most cost effective way to transform student achievement. Most teachers actually say that their curriculum is not aligned with standards and it detracts from their ability to effectively teach students. It's one of the things that we haven't really grappled with as a larger ecosystem as to how we could make it better. New York City really set out to do that.

Why do you think curriculum has yet to really be challenged in a certain way? I don't actually know that there are that many people with the expertise to challenge how we approach curriculum development and those with the expertise, do not necessarily have the capacity. A lot of the shifts to make curriculum effective for students fall on teachers. I remember as a teacher, I could never say, "Oh, the curriculum you gave me was bad." I was accountable to ensuring that whatever I put in front of my kids met there learning needs. I took that onus on myself to make those shifts and make those edits, which is unfortunate because that's time I could have spent analyzing student work and really thinking about other ways to strengthen instruction.

The latest research, perspectives, and highlights from the Harvard Graduate School of Education

Related Articles

Planting Roots of Righteousness

Stand Up for Mother Earth!

The do’s and don'ts of empowering young children in the face of climate change

Writing Student-Friendly Climate Curriculum for Teachers

Trade Schools, Colleges and Universities

Join Over 1.5 Million People We've Introduced to Awesome Schools Since 2001

Trade Schools Home > Articles > Issues in Education

Major Issues in Education: 20 Hot Topics (From Grade School to College)

By Publisher | Last Updated August 1, 2023

In America, issues in education are big topics of discussion, both in the news media and among the general public. The current education system is beset by a wide range of challenges, from cuts in government funding to changes in disciplinary policies—and much more. Everyone agrees that providing high-quality education for our citizens is a worthy ideal. However, there are many diverse viewpoints about how that should be accomplished. And that leads to highly charged debates, with passionate advocates on both sides.

Understanding education issues is important for students, parents, and taxpayers. By being well-informed, you can contribute valuable input to the discussion. You can also make better decisions about what causes you will support or what plans you will make for your future.

This article provides detailed information on many of today's most relevant primary, secondary, and post-secondary education issues. It also outlines four emerging trends that have the potential to shake up the education sector. You'll learn about:

- 13 major issues in education at the K-12 level

- 7 big issues in higher education

- 5 emerging trends in education

13 Major Issues in Education at the K-12 Level

1. Government funding for education

School funding is a primary concern when discussing current issues in education. The American public education system, which includes both primary and secondary schools, is primarily funded by tax revenues. For the 2021 school year, state and local governments provided over 89 percent of the funding for public K-12 schools. After the Great Recession, most states reduced their school funding. This reduction makes sense, considering most state funding is sourced from sales and income taxes, which tend to decrease during economic downturns.

However, many states are still giving schools less cash now than they did before the Great Recession. A 2022 article from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) notes that K-12 education is set to receive the largest-ever one-time federal investment. However, the CBPP also predicts this historic funding might fall short due to pandemic-induced education costs. The formulas that states use to fund schools have come under fire in recent years and have even been the subjects of lawsuits. For example, in 2017, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled that the legislature's formula for financing schools was unconstitutional because it didn't adequately fund education.

Less funding means that smaller staff, fewer programs, and diminished resources for students are common school problems. In some cases, schools are unable to pay for essential maintenance. A 2021 report noted that close to a quarter of all U.S. public schools are in fair or poor condition and that 53 percent of schools need renovations and repairs. Plus, a 2021 survey discovered that teachers spent an average of $750 of their own money on classroom supplies.

The issue reached a tipping point in 2018, with teachers in Arizona, Colorado, and other states walking off the job to demand additional educational funding. Some of the protests resulted in modest funding increases, but many educators believe that more must be done.

2. School safety

Over the past several years, a string of high-profile mass shootings in U.S. schools have resulted in dozens of deaths and led to debates about the best ways to keep students safe. After 17 people were killed in a shooting at a high school in Parkland, Florida in 2018, 57 percent of teenagers said they were worried about the possibility of gun violence at their school.

Figuring out how to prevent such attacks and save students and school personnel's lives are problems faced by teachers all across America.

Former President Trump and other lawmakers suggested that allowing specially trained teachers and other school staff to carry concealed weapons would make schools safer. The idea was that adult volunteers who were already proficient with a firearm could undergo specialized training to deal with an active shooter situation until law enforcement could arrive. Proponents argued that armed staff could intervene to end the threat and save lives. Also, potential attackers might be less likely to target a school if they knew that the school's personnel were carrying weapons.

Critics argue that more guns in schools will lead to more accidents, injuries, and fear. They contend that there is scant evidence supporting the idea that armed school officials would effectively counter attacks. Some data suggests that the opposite may be true: An FBI analysis of active shooter situations between 2000 and 2013 noted that law enforcement personnel who engaged the shooter suffered casualties in 21 out of 45 incidents. And those were highly trained professionals whose primary purpose was to maintain law and order. It's highly unlikely that teachers, whose focus should be on educating children, would do any better in such situations.

According to the National Education Association (NEA), giving teachers guns is not the answer. In a March 2018 survey , 74 percent of NEA members opposed arming school personnel, and two-thirds said they would feel less safe at work if school staff were carrying guns. To counter gun violence in schools, the NEA supports measures like requiring universal background checks, preventing mentally ill people from purchasing guns, and banning assault weapons.

3. Disciplinary policies

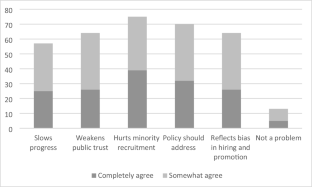

Data from the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights in 2021 suggests that black students face disproportionately high rates of suspension and expulsion from school. For instance, in K-12 schools, black male students make up only 7.7 percent of enrollees but account for over 40% percent of suspensions. Many people believe some teachers apply the rules of discipline in a discriminatory way and contribute to what has been termed the "school-to-prison pipeline." That's because research has demonstrated that students who are suspended or expelled are significantly more likely to become involved with the juvenile justice system.

In 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Department of Education issued guidelines for all public schools on developing disciplinary practices that reduce disparities and comply with federal civil rights laws. The guidelines urged schools to limit exclusionary disciplinary tactics such as suspension and expulsion. They also encourage the adoption of more positive interventions such as counseling and restorative justice strategies. In addition, the guidelines specified that schools could face a loss of federal funds if they carried out policies that had a disparate impact on some racial groups.

Opponents argue that banning suspensions and expulsions takes away valuable tools that teachers can use to combat student misbehavior. They maintain that as long as disciplinary policies are applied the same way to every student regardless of race, such policies are not discriminatory. One major 2014 study found that the racial disparities in school suspension rates could be explained by the students' prior behavior rather than by discriminatory tactics on the part of educators.

In 2018, the Federal Commission on School Safety (which was established in the wake of the school shootings in Parkland, Florida) was tasked with reviewing and possibly rescinding the 2014 guidelines. According to an Education Next survey taken shortly after the announced review, only 27 percent of Americans support federal policies that limit racial disparities in school discipline.

4. Technology in education

Technology in education is a powerful movement that is sweeping through schools nationwide. After all, today's students have grown up with digital technology and expect it to be part of their learning experience. But how much of a role should it play in education?

Proponents point out that educational technology offers the potential to engage students in more active learning, as evidenced in flipped classrooms . It can facilitate group collaboration and provide instant access to up-to-date resources. Teachers and instructors can integrate online surveys, interactive case studies, and relevant videos to offer content tailored to different learning styles. Indeed, students with special needs frequently rely on assistive technology to communicate and access course materials.

But there are downsides as well. For instance, technology can be a distraction. Some students tune out of lessons and spend time checking social media, playing games, or shopping online. One research study revealed that students who multitasked on laptops during class scored 11 percent lower on an exam that tested their knowledge of the lecture. Students who sat behind those multitaskers scored 17 percent lower. In the fall of 2017, University of Michigan professor Susan Dynarski cited such research as one of the main reasons she bans electronics in her classes.

More disturbingly, technology can pose a real threat to student privacy and security. The collection of sensitive student data by education technology companies can lead to serious problems. In 2017, a group called Dark Overlord hacked into school district servers in several states and obtained access to students' personal information, including counselor reports and medical records. The group used the data to threaten students and their families with physical violence.

5. Charter schools and voucher programs

School choice is definitely among the hot topics in education these days. Former U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos was a vocal supporter of various forms of parental choice, including charter schools and school vouchers.

Charter schools are funded through a combination of public and private money and operate independently of the public system. They have charters (i.e., contracts) with school districts, states, or private organizations. These charters outline the academic outcomes that the schools agree to achieve. Like mainstream public schools, charter schools cannot teach religion or charge tuition, and their students must complete standardized testing . However, charter schools are not limited to taking students in a certain geographic area. They have more autonomy to choose their teaching methods. Charter schools are also subject to less oversight and fewer regulations.

School vouchers are like coupons that allow parents to use public funds to send their child to the school of their choice, which can be private and may be either secular or religious. In many cases, vouchers are reserved for low-income students or students with disabilities.

Advocates argue that charter schools and school vouchers offer parents a greater range of educational options. Opponents say that they privatize education and siphon funding away from regular public schools that are already financially strapped. The 2018 Education Next survey found that 44 percent of the general public supports charter schools' expansion, while 35 percent oppose such a move. The same poll found that 54 percent of people support vouchers.

6. Common Core

The Common Core State Standards is a set of academic standards for math and language arts that specify what public school students are expected to learn by the end of each year from kindergarten through 12th grade. Developed in 2009, the standards were designed to promote equity among public K-12 students. All students would take standardized end-of-year tests and be held to the same internationally benchmarked standards. The idea was to institute a system that brought all schools up to the same level and allowed for comparison of student performance in different regions. Such standards would help all students with college and career readiness.

Some opponents see the standards as an unwelcome federal intrusion into state control of education. Others are critical of the way the standards were developed with little input from experienced educators. Many teachers argue that the standards result in inflexible lesson plans that allow for less creativity and fun in the learning process.

Some critics also take issue with the lack of accommodation for non-traditional learners. The Common Core prescribes standards for each grade level, but students with disabilities or language barriers often need more time to fully learn the material.

The vast majority of states adopted the Common Core State Standards when they were first introduced. Since then, more than a dozen states have either repealed the standards or revised them to align better with local needs. In many cases, the standards themselves have remained virtually the same but given a different name.

And a name can be significant. In the Education Next 2018 survey, a group of American adults was asked whether they supported common standards across states. About 61 percent replied that they did. But when another group was polled about Common Core specifically, only 45 percent said they supported it.

7. Standardized testing

During the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) years, schools—and teachers—were judged by how well students scored on such tests. Schools whose results weren't up to par faced intense scrutiny, and in some cases, state takeover or closure. Teachers' effectiveness was rated by how much improvement their students showed on standardized exams. The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which took effect in 2016, removed NCLB's most punitive aspects. Still, it maintained the requirement to test students every year in Grades 3 to 8, and once in high school.

But many critics say that rampant standardized testing is one of the biggest problems in education. They argue that the pressure to produce high test scores has resulted in a teach-to-the-test approach to instruction in which other non-tested subjects (such as art, music, and physical education) have been given short shrift to devote more time to test preparation. And they contend that policymakers overemphasize the meaning of standardized test results, which don't present a clear or complete picture of overall student learning.

8. Teacher salaries

According to 2021-22 data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), in most states, teacher pay has decreased over the last several years. However, in some states average salaries went up. It's also important to note that public school teachers generally enjoy pensions and other benefits that make up a large share of their compensation.

But the growth in benefits has not been enough to balance out the overall low wages. An Economic Policy Institute report found that even after factoring in benefits, public-sector teachers faced a compensation penalty of 14.2 percent in 2021 relative to other college graduates.

9. The teaching of evolution

In the U.S., public school originated to spread religious ideals, but it has since become a strictly secular institution. And the debate over how to teach public school students about the origins of life has gone on for almost a century.

Today, Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection is accepted by virtually the entire scientific community. However, it is still controversial among many Americans who maintain that living things were guided into existence. A pair of surveys from 2014 revealed that 98 percent of scientists aligned with the American Association for the Advancement of Science believed that humans evolved. But it also revealed that, overall, only 52 percent of American adults agreed.

Over the years, some states have outright banned teachers from discussing evolution in the classroom. Others have mandated that students be allowed to question the scientific soundness of evolution, or that equal time be given to consideration of the Judeo-Christian notion of divine creation (i.e., creationism).

Some people argue that the theory of intelligent design—which posits that the complexities of living things cannot be explained by natural selection and can best be explained as resulting from an intelligent cause—is a legitimate scientific theory that should be allowed in public school curricula. They say it differs from creationism because it doesn't necessarily ascribe life's design to a supernatural deity or supreme being.

Opponents contend that intelligent design is creationism in disguise. They think it should not be taught in public schools because it is religiously motivated and has no credible scientific basis. And the courts have consistently held that the teaching of creationism and intelligent design promotes religious beliefs and therefore violates the Constitution's prohibition against the government establishment of religion. Still, the debate continues.

10. Teacher tenure

Having tenure means that a teacher cannot be let go unless their school district demonstrates just cause. Many states grant tenure to public school teachers who have received satisfactory evaluations for a specified period of time (which ranges from one to five years, depending on the state). A few states do not grant tenure at all. And the issue has long been mired in controversy.

Proponents argue that tenure protects teachers from being dismissed for personal or political reasons, such as disagreeing with administrators or teaching contentious subjects such as evolution. Tenured educators can advocate for students without fear of reprisal. Supporters also say that tenure gives teachers the freedom to try innovative instruction methods to deliver more engaging educational experiences. Tenure also protects more experienced (and more expensive) teachers from being arbitrarily replaced with new graduates who earn lower salaries.

Critics contend that tenure makes it difficult to dismiss ineffectual teachers because going through the legal process of doing so is extremely costly and time-consuming. They say that tenure can encourage complacency since teachers' jobs are secure whether they exceed expectations or just do the bare minimum. Plus, while the granting of tenure often hinges on teacher evaluations, 2017 research found that, in practice, more than 99 percent of teachers receive ratings of satisfactory or better. Some administrators admit to being reluctant to give low ratings because of the time and effort required to document teachers' performance and provide support for improvement.

11. Bullying

Bullying continues to be a major issue in schools all across the U.S. According to a National Center for Education Statistics study , around 22 percent of students in Grades 6 through 12 reported having been bullied at school, or on their way to or from school, in 2019. That figure was down from 28 percent in 2009, but it is still far too high.

The same study revealed that over 22 percent of students reported being bullied once a day, and 6.3 percent reported experiencing bullying two to ten times in a day. In addition, the percentage of students who reported the bullying to an adult was over 45 percent in 2019.

But that still means that almost 60 percent of students are not reporting bullying. And that means children are suffering.

Bullied students experience a range of emotional, physical, and behavioral problems. They often feel angry, anxious, lonely, and helpless. They are frequently scared to go to school, leading them to suffer academically and develop a low sense of self-worth. They are also at greater risk of engaging in violent acts or suicidal behaviors.