Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Mesopotamian creation myths.

Ira Spar Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Stories describing creation are prominent in many cultures of the world. In Mesopotamia, the surviving evidence from the third millennium to the end of the first millennium B.C. indicates that although many of the gods were associated with natural forces, no single myth addressed issues of initial creation. It was simply assumed that the gods existed before the world was formed. Unfortunately, very little survives of Sumerian literature from the third millennium B.C. Several fragmentary tablets contain references to a time before the pantheon of the gods, when only the Earth (Sumerian: ki ) and Heavens (Sumerian: an ) existed. All was dark, there existed neither sunlight nor moonlight; however, the earth was green and water was in the ground, although there was no vegetation. More is known from Sumerian poems that date to the beginning centuries of the second millennium B.C.

A Sumerian myth known today as “ Gilgamesh and the Netherworld” opens with a mythological prologue. It assumes that the gods and the universe already exist and that once a long time ago the heavens and earth were united, only later to be split apart. Later, humankind was created and the great gods divided up the job of managing and keeping control over heavens, earth, and the Netherworld.

The origins of humans are described in another early second-millennium Sumerian poem, “The Song of the Hoe.” In this myth, as in many other Sumerian stories, the god Enlil is described as the deity who separates heavens and earth and creates humankind. Humanity is formed to provide for the gods, a common theme in Mesopotamian literature.

In the Sumerian poem “The Debate between Grain and Sheep,” the earth first appeared barren, without grain, sheep, or goats. People went naked. They ate grass for nourishment and drank water from ditches. Later, the gods created sheep and grain and gave them to humankind as sustenance. According to “The Debate between Bird and Fish,” water for human consumption did not exist until Enki, lord of wisdom, created the Tigris and Euphrates and caused water to flow into them from the mountains. He also created the smaller streams and watercourses, established sheepfolds, marshes, and reedbeds, and filled them with fish and birds. He founded cities and established kingship and rule over foreign countries. In “The Debate between Winter and Summer,” an unknown Sumerian author explains that summer and winter, abundance, spring floods, and fertility are the result of Enlil’s copulation with the hills of the earth.

Another early second-millennium Sumerian myth, “Enki and the World Order,” provides an explanation as to why the world appears organized. Enki decided that the world had to be well managed to avoid chaos. Various gods were thus assigned management responsibilities that included overseeing the waters, crops, building activities, control of wildlife, and herding of domestic animals, as well as oversight of the heavens and earth and the activities of women.

According to the Sumerian story “Enki and Ninmah,” the lesser gods, burdened with the toil of creating the earth, complained to Namma, the primeval mother, about their hard work. She in turn roused her son Enki, the god of wisdom, and urged him to create a substitute to free the gods from their toil. Namma then kneaded some clay, placed it in her womb, and gave birth to the first humans.

Babylonian poets, like their Sumerian counterparts, had no single explanation for creation. Diverse stories regarding creation were incorporated into other types of texts. Most prominently, the Babylonian creation story Enuma Elish is a theological legitimization of the rise of Marduk as the supreme god in Babylon, replacing Enlil, the former head of the pantheon. The poem was most likely compiled during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar I in the later twelfth century B.C., or possibly a short time afterward. At this time, Babylon , after many centuries of rule by the foreign Kassite dynasty , achieved political and cultural independence. The poem celebrates the ascendancy of the city and acts as a political tractate explaining how Babylon came to succeed the older city of Nippur as the center of religious festivals.

The poem itself has 1,091 lines written on seven tablets. It opens with a theogony, the descent of the gods, set in a time frame prior to creation of the heavens and earth. At that time, the ocean waters, called Tiamat, and her husband, the freshwater Apsu, mingled, with the result that several gods emerged in pairs. Like boisterous children, the gods produced so much noise that Apsu decided to do away with them. Tiamat, more indulgent than her spouse, urged patience, but Apsu, stirred to action by his vizier, was unmoved. The gods, stunned by the prospect of death, called on the resourceful god Ea to save them. Ea recited a spell that made Apsu sleep. He then killed Apsu and captured Mummu, his vizier. Ea and his wife Damkina then gave birth to the hero Marduk, the tallest and mightiest of the gods. Marduk, given control of the four winds by the sky god Anu, is told to let the winds whirl. Picking up dust, the winds create storms that upset and confound Tiamat. Other gods suddenly appear and complain that they, too, cannot sleep because of the hurricane winds. They urge Tiamat to do battle against Marduk so that they can rest. Tiamat agrees and decides to confront Marduk. She prepares for battle by having the mother goddess create eleven monsters. Tiamat places the monsters in charge of her new spouse, Qingu, who she elevates to rule over all the gods. When Ea hears of the preparations for battle, he seeks advice from his father, Anshar, king of the junior gods. Anshar urges Ea and afterward his brother Anu to appease the goddess with incantations. Both return frightened and demoralized by their failure. The young warrior god Marduk then volunteers his strength in return for a promise that, if victorious, he will become king of the gods. The gods agree, a battle ensues, and Marduk vanquishes Tiamat and Qingu, her host. Marduk then uses Tiamat’s carcass for the purpose of creation. He splits her in half, “like a dried fish,” and places one part on high to become the heavens, the other half to be the earth. As sky is now a watery mass, Marduk stretches her skin to the heavens to prevent the waters from escaping, a motif that explains why there is so little rainfall in southern Iraq. With the sky now in place, Marduk organizes the constellations of the stars. He lays out the calendar by assigning three stars to each month, creates his own planet, makes the moon appear, and establishes the sun, day, and night. From various parts of Tiamat’s body, he creates the clouds, winds, mists, mountains, and earth.

The myth continues as the gods swear allegiance to the mighty king and create Babylon and his temple, the Esagila, a home where the gods can rest during their sojourn upon the earth. The myth conveniently ignores Nippur, the holy city esteemed by both the Sumerians and the rulers of Kassite Babylonia . Babylon has replaced Nippur as the dwelling place of the gods.

Meanwhile, Marduk fulfills an earlier promise to provide provisions for the junior gods if he gains victory as their supreme leader. He then creates humans from the blood of Qingu, the slain and rebellious consort of Tiamat. He does this for two reasons: first, in order to release the gods from their burdensome menial labors, and second, to provide a continuous source of food and drink to temples.

The gods then celebrate and pronounce Marduk’s fifty names, each an aspect of his character and powers. The composition ends by stating that this story and its message (presumably the importance of kingship to the maintenance of order) should be preserved for future generations and pondered by those who are wise and knowledgeable. It should also be used by parents and teachers to instruct so that the land may flourish and its inhabitants prosper.

The short tale “Marduk, Creator of the World” is another Babylonian narrative that opens with the existence of the sea before any act of creation. First to be created are the cities, Eridu and Babylon, and the temple Esagil is founded. Then the earth is created by heaping dirt upon a raft in the primeval waters. Humankind, wild animals, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the marshlands and canebrake, vegetation, and domesticated animals follow. Finally, palm groves and forests appear. Just before the composition becomes fragmentary and breaks off, Marduk is said to create the city of Nippur and its temple, the Ekur, and the city of Uruk, with its temple Eanna.

“The Creation of Humankind” is a bilingual Sumerian- Akkadian story also referred to in scholarly literature as KAR 4. This account begins after heaven was separated from earth, and features of the earth such as the Tigris, Euphrates, and canals established. At that time, the god Enlil addressed the gods asking what should next be accomplished. The answer was to create humans by killing Alla-gods and creating humans from their blood. Their purpose will be to labor for the gods, maintaining the fields and irrigation works in order to create bountiful harvests, celebrate the gods’ rites, and attain wisdom through study.

Spar, Ira. “Mesopotamian Creation Myths.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/epic/hd_epic.htm (April 2009)

Further Reading

Black, J. A., G. Cunningham, E. Flückiger-Hawker, E. Robson, and G. Zólyomi, trans. The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature .. Oxford: , 1998–2006.

Foster, Benjamin R. Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature . 3d ed.. Bethesda, Md.: CDL Press, 2005.

Jacobsen, Thorkild. The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976.

Jacobsen, Thorkild, trans. and ed. The Harps That Once . . . : Sumerian Poetry in Translation . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

Lambert, W. G. "Mesopotamian Creation Stories." In Imagining Creation , edited by Markham J. Geller and Mineke Schipper, pp. 17–59. IJS Studies in Judaica 5.. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

Lambert, W. G., and Alan R. Millard. Atra-Hasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood . Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

Additional Essays by Ira Spar

- Spar, Ira. “ Flood Stories .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ Gilgamesh .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ Mesopotamian Deities .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ The Gods and Goddesses of Canaan .” (April 2009)

- Spar, Ira. “ The Origins of Writing .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Flood Stories

- The Isin-Larsa and Old Babylonian Periods (2004–1595 B.C.)

- Mesopotamian Deities

- The Akkadian Period (ca. 2350–2150 B.C.)

- Art of the First Cities in the Third Millennium B.C.

- Assyria, 1365–609 B.C.

- Early Excavations in Assyria

- The Gods and Goddesses of Canaan

- The Middle Babylonian / Kassite Period (ca. 1595–1155 B.C.) in Mesopotamia

- The Old Assyrian Period (ca. 2000–1600 B.C.)

- The Origins of Writing

- Mesopotamia, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Mesopotamia, 1–500 A.D.

- Mesopotamia, 2000–1000 B.C.

- Mesopotamia, 8000–2000 B.C.

- 10th Century B.C.

- 1st Century B.C.

- 2nd Century B.C.

- 2nd Millennium B.C.

- 3rd Century B.C.

- 3rd Millennium B.C.

- 4th Century B.C.

- 5th Century B.C.

- 6th Century B.C.

- 7th Century B.C.

- 8th Century B.C.

- 9th Century B.C.

- Agriculture

- Akkadian Period

- Ancient Near Eastern Art

- Aquatic Animal

- Architecture

- Astronomy / Astrology

- Babylonian Art

- Deity / Religious Figure

- Kassite Period

- Literature / Poetry

- Mesopotamian Art

- Mythical Creature

- Religious Art

- Sumerian Art

World History Edu

- Religion / World History

13 Creation Myths in World History

by World History Edu · November 7, 2020

Creation myths and stories

Ever since the dawn of civilization, we humans have pondered where everything, including life, came from. It has also been the case of why and how did we and things around come to being. And so, with the passage of time, there have been quite a plethora of creation stories from different cultures and civilizations. Often times, those creation stories formed the foundations of many ancient religions across the globe. The 13 creation myths that we are about to explore are generally regarded as the most amazing creation stories of all time.

Heliopolis creation story – ancient Egypt

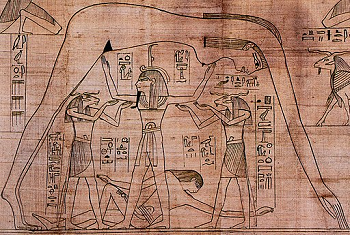

Shu (center) separating Geb from Nut

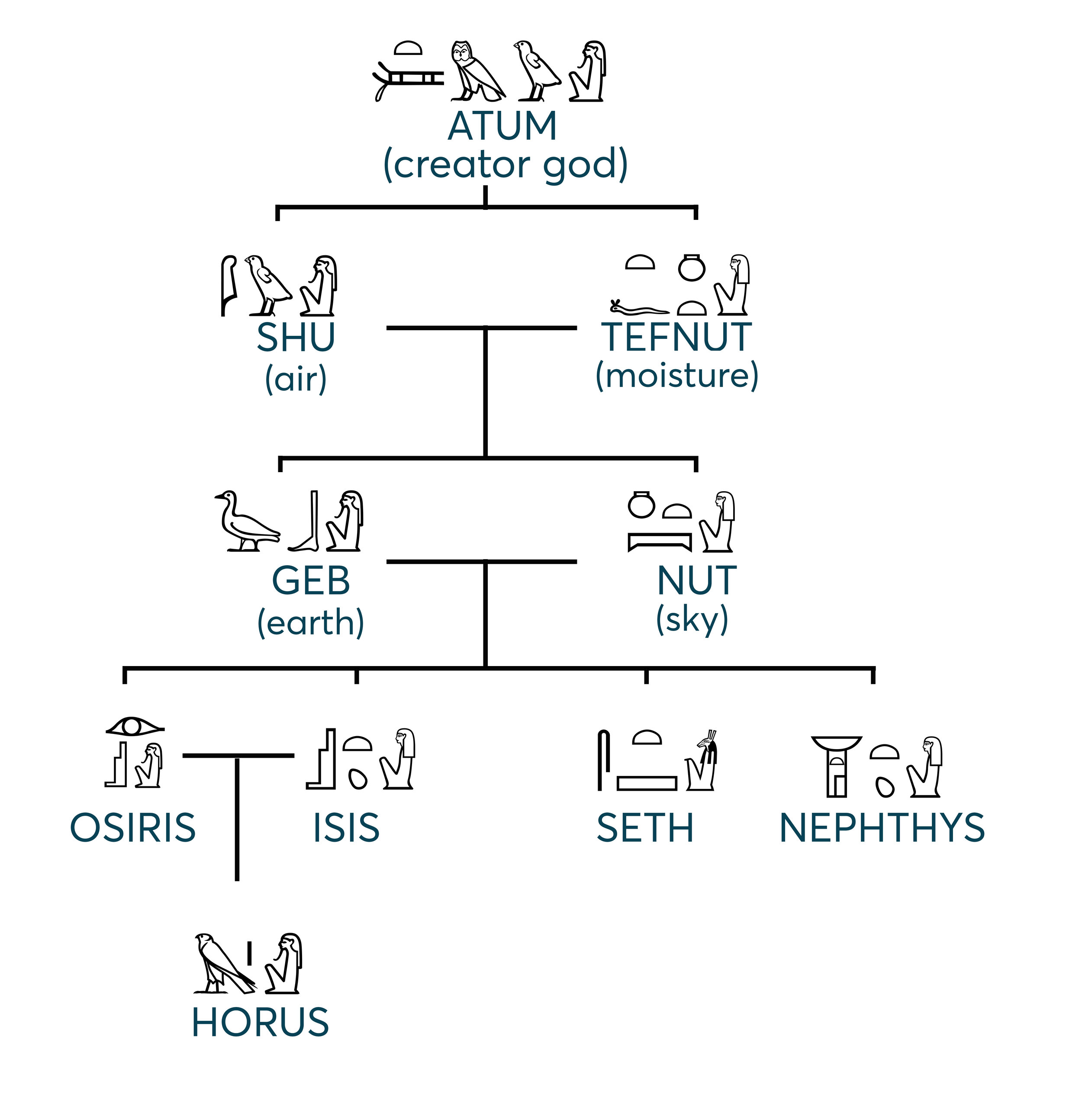

According to the ancient Egyptians , the universe started with a primordial ocean known as Nun. At the center of Nun was a giant pyramid called benben. Deep within benben, came forth Atum (in some cases Ra , the sun deity), the creator deity .

As the physical embodiment of the sun, Atum created life in an asexual manner. He also created the first Egyptian deities – Shu (air) and Tefnut (water/moisture). Together with his children, Atum was able to hold back the destructive forces of chaos and keep the universe in balance. Atum was also supported by Ma’at , the ancient Egyptian goddess of truth and order .

READ MORE: Why did the people of Egypt rebel against Ra?

The union between Shu and Tefnut brought forth Geb (earth) and Nut (sky). Due to the immense love shared between Geb and Nut, the two deities remained inseparable. Atum then instructed Shu to separate Geb (the earth) from Nut (the sky). But just before Shu could carry out the task, Geb and Nut gave birth to famous Egyptian deities such as Osiris , Isis , Seth , and Nephthys .

Atum (or Ra) along with his eight descendants make up the Ennead of Heliopolis in ancient Egypt. Undoubtedly, the Heliopolis creation story is one of the major events found in ancient Egyptian religion.

Read More: 10 Most Famous Ancient Egyptian Gods and Goddesses

Proto-Indo-European Creation Myths

Among many Proto-Indo-European cultures, Ymir was the force that existed in the time before time. This being was also the embodiment of the vast sea of chaos (Ginnungagap) – a region devoid of any life form or structure or order. Thus Ymir was there long before famous Norse gods like Odin , Thor or Freya even came onto the scene.

Due to the absence of any celestial body, sea, land or crops, Ymir is believed to have suckled on a primordial cow called Audhumla.

One time, while suckling on Audhumla, two enormous giants were asexually produced from Ymir’s perspirations. The myth goes on to say that a third giant, equally as large as the first two, also emerged from Ymir’s legs.

With regard to the primordial cow Audhumla, her source of nourishment was from the salt sediments found on the creature called Buri. Norse mythology regards Buri as the first god in the pantheon. As Audhumla licked Buri, the chains that held the god gradually faded away, and the god was free. Buri’s son, Borr, went on to mate with Ymir, producing a being called Bestla.

After Borr and Bestla mated Odin, the all father god in Norse mythology, was born. Envious of his grandfather Ymir, it is believed that Odin and his sibling killed Ymir. Odin then used the dismembered body of Ymir to create the world that we know.

READ MORE: Most Powerful Weapons in Norse Mythology

Each body part of Ymir produced a particular feature of nature. For example, an old Norse collection of poems – the Poetic Edda – state that: The earth was created from Ymir’s flesh; the seas/oceans of the world came from Ymir’s sweat; from his bones emerged the mountains; from his hair came the trees and the greens of the world; and finally, from Ymir’s skull burst out the sky. The poem also states that the clouds we see today emerged from Ymir’s brains. So where did men come from?

The myth goes on to say that Odin and the Norse gods fashioned a realm called Midgard (Earth) from the eyebrows of Ymir. They then used the Midgard to create the first humans, Ask and Embla .

Read More: 10 Most Famous Norse Gods and Goddesses

Mayan creation story

Mayan creation story | image: El Castillo, at Chichen Itza

The Mayan creation story is contained in the Popul Vuh (also known the “Book of the Community” or the “Book of the People”). The text was written in Mayan hieroglyphics. Kind courtesy to the translation that was done later we know what the Mayan creation story is. According to the text, the beginning of time was filled with nothingness devoid of any structure or order.

Tepeu (the maker) and Gucumatz (the feathered spirit) joined their thoughts together to create the universe. They proceeded to create man. In their first attempt, they created man out of wet clay; however, that did not go as planned as the clay crumbled apart.

READ MORE: 11 Principal Maya Gods and Goddesses

In their second attempt, the gods created man out of wood; and just like the first attempt, the creation failed to please the creators. In their third attempt, they created man out of maize dough. It is believed that this form of man thrived and was able to speak, feel and think.

In order to make the earth very habitable for their creation, the gods created the sun, the moon and the stars. Subsequently, they created four kinds of animals – a parrot, a coyote, a fox, and a crow. These animals then went in four different directions to make a home for themselves. Because the animals could not speak, the gods commanded them to forever remain obedient to human beings. The humans were also allowed to feed on the animals.

Read More: Timeline of Maya Civilization

Babylonian creation myth

The ancient Babylonians believed that in the beginning two primordial gods – Aspu and Tiamet (or Tiamat) – existed. Prior to that, the universe was a vast void of nothingness, land and sky had yet formed.

Tiamet and Aspu mated and gave birth to a new crop of gods. It is believed that Tiamet grew enormous amount of hatred toward the new gods. Tiamet set out to destroy them.

However, just before Tiamet could carry out his plan, the gods found out and proceeded to stop him. Led by Marduk , the gods threw a strong, powerful net over Tiamet. Once trapped in the net, the gods beat Tiamet to pulp and cracked her skull.

Tiamet’s body was then dismembered; half of the body was used to create the sky while the other half was used to create human beings, plants, animals, and the creatures that occupy the land today.

READ MORE: Marduk’s Conflict with Tiamat

Creation of mankind according to the ancient Greeks

Prometheus watches as the goddess Athena bestows upon his creation, man, with reason (painting by Christian Griepenkerl, 1877)

In ancient Greece, the predominant creation story was the one that involved the Greek Titan Prometheus , the Titan who created man.

In the beginning, the world was endlessly empty and full of a being known as Nyx – the deity of darkness. The goddess Nyx is believed to have laid a golden egg. After sitting on the egg for eons of years, the egg hatched, producing the deity of love Eros . The broken shells of the egg became the sky and the earth.

The earth was called Gaia , also known as the goddess of the earth. On the other hand, the sky was called Uranus. The goddess Gaia and the god Uranus mated, bringing forth a new generation of gods known as the titans, Hekatonkheires, Cyclopes, etc. Those Greek Titans included the likes of Oceanus, Crius, Iapetus, Tethys , Phoebe , and Kronus .

Kronus, who early on had overthrown his father Uranus, then went on to give birth (with Rhea) to another generation of gods, which included the likes of Hera , Hades , Poseidon , Hestia , Demeter , and Zeus . Similar to the fate that Uranus suffered, Kronus and his siblings were overthrown by his children who were led by Zeus (the King of the Olympians ).

After the battle with the Titans, Zeus commanded Prometheus and his brother Epimethius to go down to earth and create the first humans. Epimethius created animals. Prometheus grew so fond of his creation – mankind – that he stole fire from the home of the gods and gifted it to mankind. This act of his incurred the wrath of Zeus who bound Prometheus to a stone and allowed an eagle to peck his liver for an eternity.

Read More: 10 Most Powerful Greek Gods and Goddesses

Ainu Creation story

The water wagtail was very important in Ainu creation myth

The Ainu creation myth emerged from Ainu peoples of Japan. In this myth, time can be broken down into three parts – “mosir noskekehe” (“the world’s center”); “Mosir sikah ohta” (“a time when the universe was born”); and “mosir kes” (“end of the world”).

According to the Ainu people, the creator god dispatched his trusted water wagtail to create the land from the cosmic ocean. The bird used its wings to move the water to one side. Subsequently, he created islands for the Ainu people to populate.

Read More: Top 10 Japanese Gods and Goddesses

Raven creation story

In many Native American cultures, the raven is arguably the most powerful creature in the entire cosmos. It is therefore not surprising that many of ancient tribes in the Americas considered the bird the creator of the universe.

In one myth, the raven is believed to have encountered an adult man who he approached to inquire about the man’s whereabouts. The man is believed to have to told the raven that he lived in the inner regions of a pea pod for four days; and on the fifth day, the man came out of the pod a full grown man.

The man also told the raven that he used the vast sea of water in his surrounding to relief the excruciating pain in his abdomen. As the Raven listened to the man attentively, he began to see a striking similarity between the man and himself. Amazed by their shared features, the Raven inquired further.

Finally, the Raven implored the man to wait for him so that could go and fetch some berries. The Raven then commanded the man to eat the berries. Shortly after, the Raven took the Man to creek. At that point, the Raven tapped four objects with his wings, bringing the four objects to life.

READ MORE: 13 Most Famous Trickster Deities in World History

Creation story according to Zoroastrianism

The Zoroastrianism faith states that there existed two opposing deities in the beginning of time. Those beings were Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainya, the deity of light and the deity of darkness respectively. Those two beings existed side by side, with each domineering over an area of the universe.

Being a benevolent force, Ahura Mazda created angels/beings that supported him in spreading the light across the universe. One such being was Amesha Spentas.

Together with his archangels Amesha Spentas (“Holy Immortals”), Ahura Mazda divided the universe into two sections – the spiritual section and the physical section. It is believed that the physical section was created about 3,000 years after the spiritual section. Shortly after the emergence of the physical section, Ahura Mazda created perfect man and a bull.

While Ahura Mazda was creating his perfect beings and man, Angra Mainyu was busily creating all the fiercest demons and evil forces in a bid to counter Ahura Mazda’s creations. It is believed that Angra Mainyu created scary animals such as ants, flies, mosquitoes, snakes, spiders etc. Angra Mainyu’s creations had the power to bring forth pain, diseases, and death.

As time went by, Ahura Mazda’s perfect man and bull died after succumbing to an evil force of Angra Mainyu. From the dead body of the perfect man came forth the first man and woman – Mashya and Mashynag. However, from the dead body of the bull, trees and vegetation sprang out.

5 Most Important Developments in Early Human History

The Sumerian creation myth (the Eridu Genesis)

During an expedition conducted by the University of Pennsylvania in 1893, an ancient Sumerian tablet was unearthed in Nippur (“Enlil City”) – i.e. modern-day Afak, Iraq. The tablet had the Sumerian creation myth – the Eridu Genesis.

The tablet describes how the main deities – An (the sky father), Enlil (the earth and wind god), Enki (god of water, knowledge and mischief), and Ninhursanga (the mother goddess) – created the world. They also create human beings to populate the world.

In one account of the myth, the gods collectively decide that mankind is not worth saving from a massive flood. However, Enki – the god of the waters – proceeds to warn an upright man by the name of Atrahasis. Enki instructs Atrahsis to construct an ark so that he could save humanity from the deluge. The flood is believed to have been caused by rains that fell for seven days and nights.

In another account, the builder of the ark is not Atrahsis; instead, it is Ziusudra, the ruler of Shuruppak. Once the flood ends, the sun god, Utu, appears outside the window of the ark. Ziusudra then bows down before Utu.

Read More: 12 Most Revered Gods of Ancient Mesopotamia

Hindu Creation Story

Hindu creation story | Image: from left to right: Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva

Hindus have quite a number of creation stories. What runs through most of those creation stories is the cyclical nature of birth, death and rebirth. According to one Hindu creation story, in the beginning there existed a mighty cobra that lived in the vast cosmic ocean. And in the hands of this cobra lay the sleeping Vishnu, the creator god.

As time went by, a lotus began to emerge from the belly button of Vishnu. And inside this sacred lotus was another Hindu god of creation called Brahma (also known as Svayambhu). The Lord of Speech, Brahma, then conceived the idea of creating the universe. But before he could do so, he goes into a deep state of meditation for several eons.

In creating the universe, Brahma – the four-headed god – is believed to have divided the lotus into three parts. The first part turns into the heavens; the second becomes the sky; and the final and third part gives birth to the earth. Pleased by how things are going, Brahma endows the earth with animals and plants of all shapes and sizes. He also creates the first human beings to dwell on the earth.

Now it must be noted that both Vishnu and Brahma are part of the Hindu triumvirate – a group of three very powerful Hindu gods responsible for creating and destroying the universe. The other god in this triumvirate is Lord Shiva , who is responsible for the destruction of the universe so that it could be reborn again. Together, these three gods – Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva – feature prominently in Hinduism and its creation story.

Read More: Lakshmi – Hindu Goddess of Wealth and Beauty

Genesis creation story

The line – “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth” – is perhaps one of the most well-known lines in scriptures from the Abrahamic religions (i.e. Christian, Islam and Judaic faiths). In the Genesis creation story , a supreme being, who was hovering over the vast cosmic waters, is believed to have created the world in six days and resting on the seventh day. On day one, God commanded for light to come out before proceeding to separate the light from the darkness. On the second day, God parted the sky from the waters, gathering the waters at one place for it to become the sea. On the third day, the Supreme Being created all the greenery and vegetation on the dry land.

On the fourth day, God created the Sun, moon and all the stars that fill our cosmos. Satisfied with the progress of his creation, God went on to create all the sea and land animals on the fifth day. On the sixth day, God created the first man, Adam, in his own image. And from the rib of Adam, God created the first woman, Eve, to serve as a companion of Adam. Exhausted by the sheer amount of work, God rested on the seventh day.

Regarding the first human beings, the Genesis story states that God placed Adam and Eve in a magnificent garden known as Eden . In that paradise condition Adam and Eve knew no suffering, no death, and no misery. However, that all changed when a serpent in the garden convinced Eve and Adam to eat from the Tree of Knowledge. Angered by their disobedience, God cast Adam and Eve out of Eden and into the world, where they and their descendants were fated to endure pain, sickness and death.

The Yoruba Creation Myth – The Golden Chain myth

Predominantly located in the West African nation of Nigeria, the Yoruba tribe have for centuries believed in the Golden Chain creation story. In the beginning, the gods lived happily in the sky. The king and queen of the gods were Olorun and Olokun, respectively.

In spite of the bliss in the sky, a lesser god known as Obatala was not completely content. Obatala desired to have for beings in addition to the celestial beings in the sky. Therefore, he consulted with Orunmila, the oldest son of Olorun. Orunmila commanded Obatala to forge a golden chain out of a snail shell filled with sand, palm nut, a black cat, and a white hen.

Obatala then descends from the sky down to the earth using his magical golden chain. The god proceeds to create the land and all living things using a white hen, a black cat, a palm nut, and a snail shell filled with sand. He placed the items in a large pit. The palm nut grew into a full palm tree. The god then brewed palm wine from the palm fruits and sat by the tree.

Drunk on so much wine, Obatala started human beings. Owing to the fact that he was intoxicated, Obatala is believed to have created human beings that were imperfect relative to the gods in the sky.

Read More: 12 Most Famous Yoruba Gods and Goddesses

Creation myth of Chinese

Image of the Chinese deity Pangu

In this creation myth, the universe began as a chaotic soup without any structure. In this universe lay a black egg that housed a gargantuan being known as Pangu – a hairy giant with two horns and two tusks.

The giant Pangu is believed to have slept in the egg for more than 18,000 years. All the while that Pangu slept, the universe was kept in perfect balance – i.e. equal amounts of darkness (yin) and light (yang).

Upon waking up from his deep sleep, Pangu proceeded to escape from the egg. By so doing, he broke the force that kept the universe in perfect balance. The top half of the egg shell, which represented yang , turned into the sky; while the bottom half, which represented yin , became the earth.

Standing in the broken shell, Pangu started to push the top part of shell farther away in order to keep yin and yang apart. As he pushes the sky up, he is believed to have grown taller – about ten feet. Aiding him in this task were four celestial creatures – the Qilin, the Phoenix, the Dragon, and the Turtle.

He would do this for close to 18,000 years before dying. Pangu’s body fell to the earth and turned into several earthly things. For example:

- His breath turned into the wind and clouds;

- His eyes became the sun and the moon;

- Pangu’s limbs and head turned into the mountains;

- His muscles turned into the fertile land;

- Pangu’s thick facial hair became the stars and the galaxy;

- And his voice became thunder.

- From the parasites that feasted on his body came forth the first human beings.

Did you know : The Daoist Xu Zheng is generally recognized as the first person to record the creation myth of Pangu?

READ MORE: Most Famous Ancient Chinese Gods and Goddesses

Tags: Ainu Ancient Mayans China Creation myths Egypt Religion Sumerian civilization Yoruba

You may also like...

Most Famous United Nations Security Council Resolutions

September 8, 2023

Treaty of Kadesh: The World’s First Peace Treaty

July 16, 2023

Vietnam War Facts: 6 Things You Need to Know about the War

September 4, 2020

- Pingbacks 0

really awesome

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Next story Hua Mulan: The Legendary Chinese Heroine

- Previous story Margaret Thatcher: 8 Major Achievements

- Popular Posts

- Recent Posts

Who were the three helpers of Tang Sanzang?

What was the Tetrarchy and why was it established by Emperor Diocletian?

What was the Ghana Empire known for?

Life and Major Accomplishments of Nicolaus Copernicus

What was life like on Mount Olympus?

Greatest African Leaders of all Time

Queen Elizabeth II: 10 Major Achievements

Donald Trump’s Educational Background

Donald Trump: 10 Most Significant Achievements

8 Most Important Achievements of John F. Kennedy

Odin in Norse Mythology: Origin Story, Meaning and Symbols

Ragnar Lothbrok – History, Facts & Legendary Achievements

9 Great Achievements of Queen Victoria

Most Ruthless African Dictators of All Time

12 Most Influential Presidents of the United States

Greek God Hermes: Myths, Powers and Early Portrayals

Kamala Harris: 10 Major Achievements

Kwame Nkrumah: History, Major Facts & 10 Memorable Achievements

8 Major Achievements of Rosa Parks

How did Captain James Cook die?

Trail of Tears: Story, Death Count & Facts

5 Great Accomplishments of Ancient Greece

Most Famous Pharaohs of Egypt

The Exact Relationship between Elizabeth II and Elizabeth I

How and when was Morse Code Invented?

- Adolf Hitler Alexander the Great American Civil War Ancient Egyptian gods Ancient Egyptian religion Apollo Athena Athens Black history Carthage China Civil Rights Movement Cold War Constantine the Great Constantinople Egypt England France Hera Horus India Isis John Adams Julius Caesar Loki Medieval History Military Generals Military History Napoleon Bonaparte Nobel Peace Prize Odin Osiris Ottoman Empire Pan-Africanism Queen Elizabeth I Religion Set (Seth) Soviet Union Thor Timeline Turkey Women’s History World War I World War II Zeus

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

111 Creation Myth Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Creation myths are ancient stories that explain the origins of the world and humanity. They often reflect the beliefs, values, and cultural norms of the societies that created them. Writing an essay on creation myths can be an exciting opportunity to explore different cultures, analyze religious beliefs, and delve into the human imagination. To help you get started, here are 111 creation myth essay topic ideas and examples:

- The creation myth of the Aztecs: a reflection of their warrior culture.

- A comparative analysis of creation myths from different Native American tribes.

- The role of animals in creation myths: a cross-cultural perspective.

- The creation myth in Hinduism: the concept of Brahma and the cycle of creation.

- Exploring the creation myth in Norse mythology: the role of gods and giants.

- How creation myths shape cultural identity: a study of African tribal myths.

- The creation myth in Christianity: the story of Adam and Eve.

- The role of women in creation myths: a feminist analysis.

- The creation myth in ancient Egyptian religion: the role of Ra and Osiris.

- A comparative study of creation myths in Greek and Roman mythology.

- The creation myth in Chinese folklore: the cosmic egg and Pangu.

- The relationship between creation myths and astronomy: a scientific analysis.

- Creation myths and the concept of time: a philosophical exploration.

- The creation myth in Aboriginal Dreamtime: the role of ancestral beings.

- The creation myth in Japanese Shintoism: the story of Izanagi and Izanami.

- The creation myth in the Bible: a symbolic interpretation.

- The role of creation myths in shaping environmental attitudes.

- The creation myth in Mayan civilization: the story of the Hero Twins.

- Creation myths and the evolution of human consciousness.

- The creation myth in ancient Mesopotamia: the Enuma Elish.

- Exploring creation myths in African diaspora religions: Vodou, Santeria, and Candomble.

- The role of creation myths in oral traditions: a study of Native American tribes.

- Creation myths and the origins of agriculture: a historical perspective.

- The creation myth in ancient Greek philosophy: Plato, Aristotle, and the demiurge.

- How creation myths influence art and literature: a study of Renaissance painters.

- The role of creation myths in contemporary popular culture: movies, books, and video games.

- Creation myths and the concept of the afterlife: a comparative analysis.

- The creation myth in Australian Aboriginal culture: the Rainbow Serpent.

- The role of creation myths in shaping gender roles and expectations.

- The creation myth in Zoroastrianism: the battle between Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu.

- Creation myths and the origins of evil: a moral exploration.

- The creation myth in ancient Sumerian religion: the story of Enki and Ninhursag.

- Exploring creation myths in indigenous cultures of the Americas: Inca, Aztec, and Maya.

- The role of creation myths in the colonization of indigenous peoples.

- Creation myths and the formation of cultural taboos: a sociological analysis.

- The creation myth in African mythology: the Yoruba story of Oduduwa.

- The relationship between creation myths and ancient cosmology.

- The creation myth in Jainism: the concept of Tirthankaras and cycles of creation.

- Creation myths and the origins of language: a linguistic analysis.

- The role of creation myths in shaping ethical systems.

- The creation myth in ancient Babylonian religion: the story of Marduk and Tiamat.

- The influence of creation myths on political ideologies and power structures.

- Creation myths and the concept of divine intervention: a theological exploration.

- The creation myth in Maori culture: the story of Ranginui and Papatuanuku.

- The role of creation myths in shaping family structures and dynamics.

- The creation myth in ancient Persian religion: the battle between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman.

- Creation myths and the origins of music: a cultural analysis.

- The creation myth in African-American folklore: the story of Brer Rabbit.

- The relationship between creation myths and psychological development.

- The creation myth in ancient Canaanite religion: the story of El and Baal.

- Creation myths and the origins of human suffering: a philosophical inquiry.

- The role of creation myths in shaping religious rituals and ceremonies.

- The creation myth in Polynesian culture: the story of Maui.

- Creation myths and the concept of divine punishment: a comparative analysis.

- The influence of creation myths on gender equality and women's rights.

- The creation myth in ancient Mesoamerican civilizations: Olmec, Zapotec, and Toltec.

- Creation myths and the origins of social hierarchies: a historical analysis.

- The role of creation myths in shaping environmental conservation efforts.

- The creation myth in African diaspora religions: the Yoruba story of Obatala and Oduduwa.

- Creation myths and the origins of moral values: a philosophical exploration.

- The creation myth in ancient Celtic culture: the story of Cernunnos and the Morrigan.

- The influence of creation myths on architectural styles and city planning.

- Creation myths and the concept of human purpose: a existentialist analysis.

- The creation myth in Australian Aboriginal culture: the Dreaming and songlines.

- The role of creation myths in healing practices and traditional medicine.

- The creation myth in ancient Finnish mythology: the story of Väinämöinen.

- Creation myths and the origins of war and conflict: a sociopolitical analysis.

- The creation myth in ancient Egyptian religion: the story of Isis and Osiris.

- The relationship between creation myths and the concept of divine providence.

- Creation myths and the origins of technology: a historical exploration.

- The creation myth in Native American tribes of the Pacific Northwest: the Raven and the Whale.

- Exploring creation myths in ancient South American civilizations: Moche, Nazca, and Chimu.

- The role of creation myths in shaping dietary practices and food taboos.

- The creation myth in ancient Japanese folklore: the story of Amaterasu and Susanoo.

- Creation myths and the origins of artistic expression: a cultural analysis.

- The creation myth in ancient Persian religion: the story of Gayomart and Zahhak.

- The influence of creation myths on educational systems and curriculum.

- Creation myths and the concept of human free will: a philosophical inquiry.

- The creation myth in ancient Sumerian religion: the story of Enlil and Ninlil.

- Creation myths and the origins of religious intolerance: a sociocultural analysis.

- The role of creation myths in shaping concepts of beauty and body ideals.

- The creation myth in Native American tribes of the Great Plains: the Buffalo and the Sun.

- Creation myths and the origins of cultural diversity: a historical exploration.

- The creation myth in ancient Hawaiian culture: the story of Pele and Kamapua'a.

- The relationship between creation myths and the concept of fate.

- Creation myths and the origins of artistic inspiration: a psychological analysis.

- The creation myth in ancient Mesopotamian religion: the story of Inanna and Dumuzid.

- Exploring creation myths in ancient Southeast Asian civilizations: Khmer, Cham, and Srivijaya.

- The creation myth in ancient Egyptian religion: the story of Nut and Geb.

- Creation myths and the origins of social justice movements: a sociopolitical analysis.

- The creation myth in Native American tribes of the Southwest: the Corn Mother and Kokopelli.

- Creation myths and the origins of cultural heritage: a historical exploration.

- The role of creation myths in shaping concepts of love and relationships.

- The creation myth in ancient Aztec culture: the story of Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca.

- Creation myths and the concept of divine revelation: a theological inquiry.

- The influence of creation myths on fashion trends and clothing styles.

- Creation myths and the origins of scientific inquiry: a historical analysis.

- The creation myth in ancient Greek religion: the story of Gaia and Uranus.

- Creation myths and the origins of social inequality: a sociological exploration.

- The role of creation myths in shaping concepts of mental health and well-being.

- The creation myth in Native American tribes of the Northeast: the Turtle and the Sky Woman.

- Exploring creation myths in ancient Central Asian civilizations: Scythian, Sogdian, and Bactrian.

- The relationship between creation myths and the concept of divine love.

- Creation myths and the origins of cultural traditions: a historical analysis.

- The creation myth in ancient Egyptian religion: the story of Horus and Set.

- Creation myths and the concept of human rights: a sociopolitical exploration.

- The creation myth in Native American tribes of the Northwest Coast: the Thunderbird and the Killer Whale.

- Creation myths and the origins of cultural exchange: a historical analysis.

- The role of creation myths in shaping concepts of spirituality and religious experience.

These 111 creation myth essay topic ideas and examples should provide you with a broad range of options to explore. Remember to choose a topic that interests you and allows you to delve into the rich tapestry of human imagination, cultural diversity, and religious beliefs. Happy writing!

Want to research companies faster?

Instantly access industry insights

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Leverage powerful AI research capabilities

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2024 Pitchgrade

Glencairn Museum News

Ancient egyptian creation myths: from watery chaos to cosmic egg.

Glencairn Museum News | Number 5, 2021

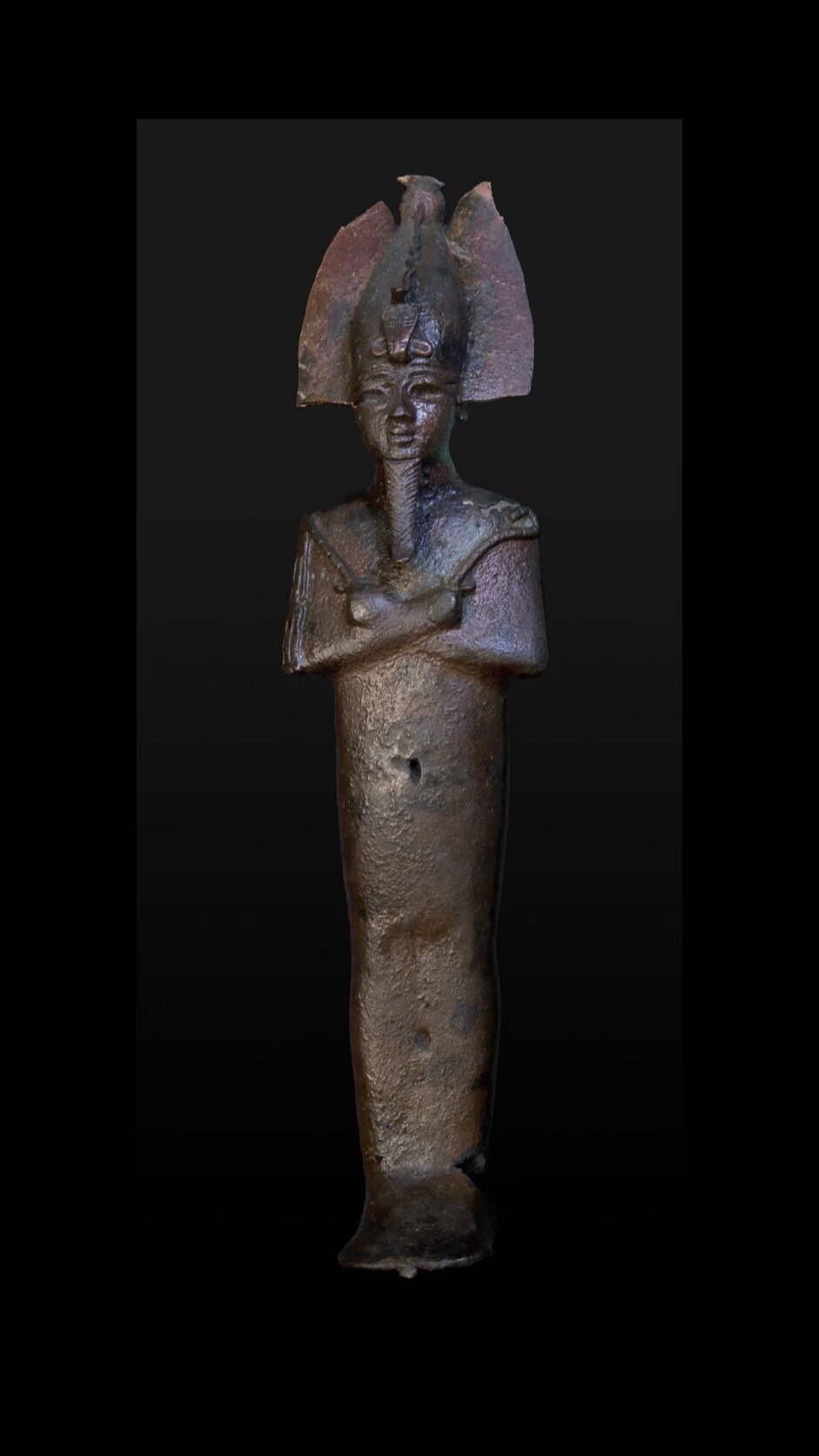

In the single column of text on the back of this faience figurine of Ptah, the god is recognized as a creator god and referred to as “the one who made heaven and who gave birth to craftsmanship.” The text further tells us that Ptah will offer life, prosperity, health, and all happiness to the owner/dedicator of the statuette.

Where did we come from and how did our world begin? For thousands of years, people from cultures all around the globe have devised stories to explain the creation of their domains. The ancient Egyptians were no different in this regard. By examining their religious literature and accompanying representations, we can come away with an understanding of how they explained the creation of the world in which they lived. Their beliefs were complex and reflected their natural environment. In this essay for Glencairn Museum News , Dr. Jennifer Houser Wegner, Associate Curator in the Egyptian Section at the Penn Museum, introduces us to the fascinating subject of ancient Egyptian creation myths, including the cosmological context for several objects in Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian gallery.

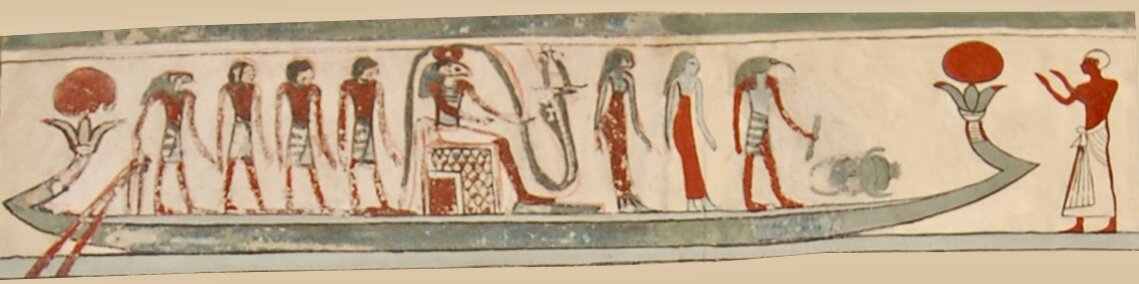

The Egyptian pantheon was filled with deities who inhabited the heavens but whose influence was experienced on earth. In the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom, which first appeared on the interiors of the pyramids of the kings of the Fifth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (c. 2500–2350 BCE), we learn that the Egyptians regarded the sky as a dwelling place of their gods and a location connected to the afterlife. Just as their daily life depended upon the Nile River, the Egyptians envisioned this heavenly realm as a landscape that divine beings navigated in sacred boats (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A scene of the divine figures in a solar boat from the stela of Pebeh (EA8466). Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 2. The falcon-headed sun god Re is adored by the priest Diefankh (UPMAA E2044). Image courtesy of the Penn Museum.

The sun god, Re, was of paramount importance to the ancient Egyptians, and the sun’s daily passage from east to west and its daily rising and setting served as a metaphor for the cycle of life—from birth, to adulthood, to death, to rebirth (Figure 2). The omnipresent sun in what was largely a desert environment may also explain the early Egyptians’ interest in solar concepts. At dusk, the sun god proceeded into the underworld (the Duat). New Kingdom funerary texts (1292–1075 BCE) and the associated images found on the walls of royal tombs record his nighttime journey. The sun god spent the twelve hours of the night traveling in the underworld, ultimately merging with Osiris, the primary funerary deity. The journey was treacherous, and the sun god faced his enemy, Apophis, a serpent who threatened him as he traveled in his solar boat nightly.

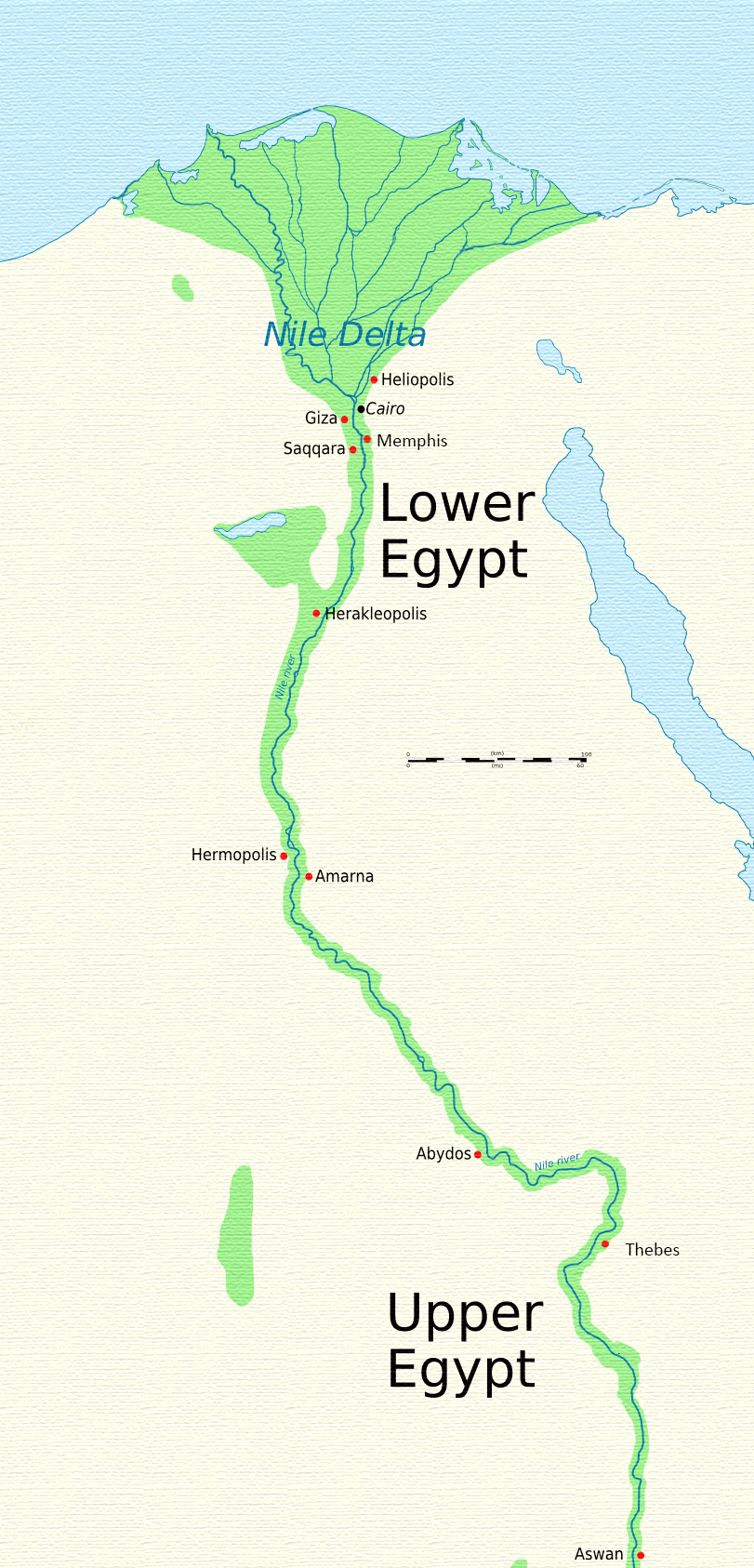

Another of Re’s important roles was as a creator god. The sun’s reappearance on the horizon at dawn each day was a symbol of the re-creation of the world. However, Re was not the sole creator god in Egyptian mythology. The Egyptians had several elaborate myths describing the origins of their world. Each of these creation stories was centered at a different city in ancient Egypt (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Map of Upper and Lower Egypt.

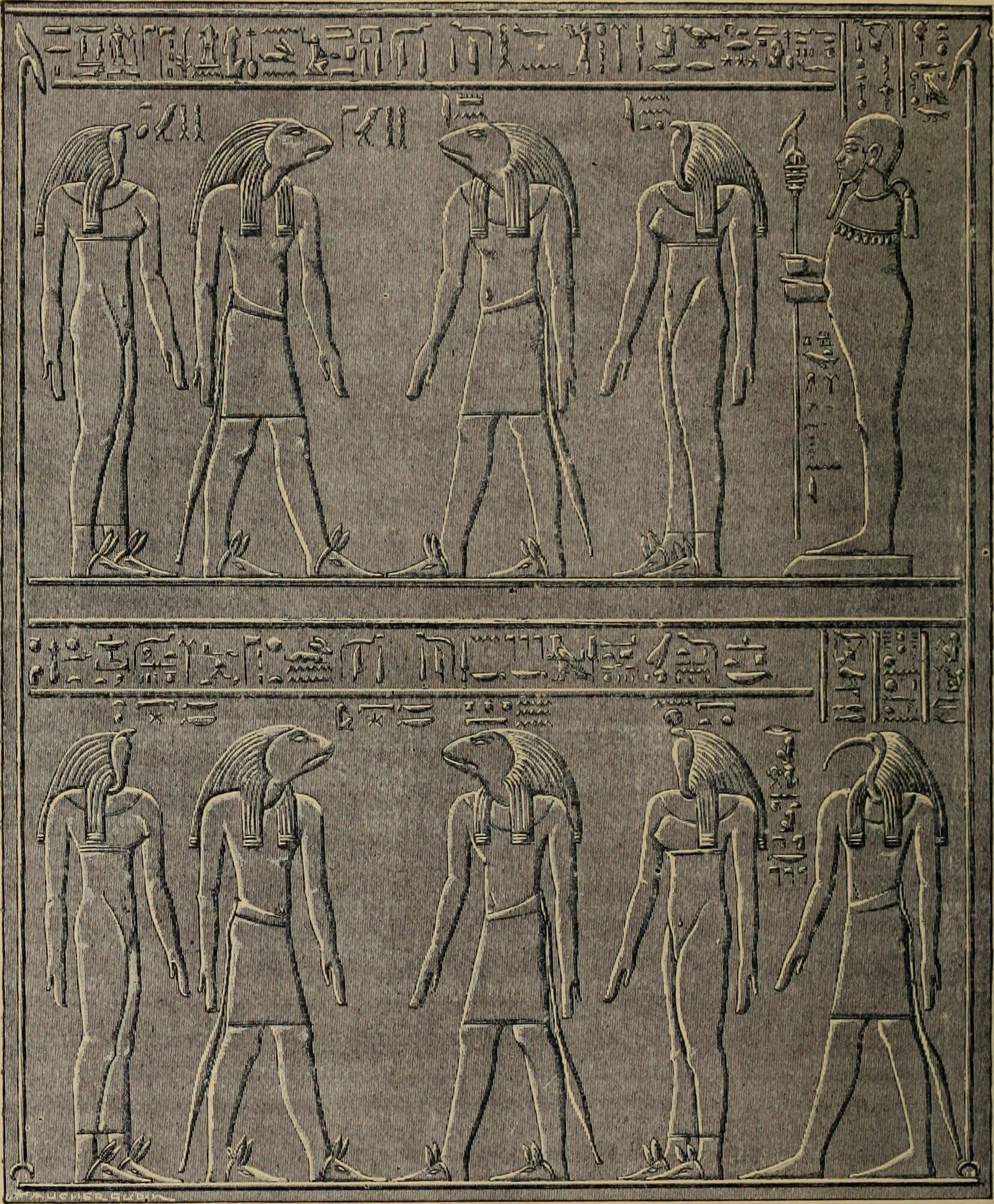

The Hermopolitan cosmology arose at the site of Hermopolis in Middle Egypt. Hermopolis was a city sacred to Thoth, the god of wisdom. The ancient Greeks equated Thoth with their god Hermes, which gives us the name Hermopolis, or “city of Hermes.” The ancient Egyptian name for this city was Khemnu, or “Eight-Town.” The number eight in this place-name makes references to the eight deities (the Ogdoad) who are the main characters in this version of the creation story. The Ogdoad consisted of four frog-headed male gods and their serpent-headed female counterparts (Figure 4). This divine group represented the dark, watery, unknown, and eternal state of the cosmos prior to creation. Nun and Naunet represented water. Heh and Hauhet expressed the notion of infinity. Kek and Kauket stood for darkness. Amun and Amaunet reflected the concept of hiddenness. These eight gods existed within the watery chaos of pre-creation.

Figure 4. An illustration of the Ogdoad, drawn by Faucher-Gudin from a photograph by Béato.

Within this unchanging “nothingness,” there was the potential for creation. The Egyptians believed that from these eight gods came a cosmic egg that contained the deity responsible for creating the rest of the world, including the primeval mound—the first land to arise out of the waters of pre-creation. In some versions of the myth, the egg was laid by a goose named “the Great Cackler,” while in other versions an ibis, the bird associated with the god Thoth, is responsible for the egg (Figures 5-6). Thoth’s appearance here in the myth is probably the work of the Hermopolitan priesthood, who wanted to recognize the importance of the city’s patron deity. After the mound appeared, a lotus blossom bloomed signaling the birth of the newborn sun god (Figure 7). After the sun made its first appearance, the rest of creation could follow. In some cases, this myth further describes a scarab beetle that emerges from the lotus. The scarab is often a solar symbol, and the texts describe how this beetle transforms into a child. When this child cried, his tears became humankind (Figure 8).

Figure 5. An amulet representing the god Thoth as an ibis-headed man (Glencairn Museum E219).

Figure 6. A bronze statuette representing the god Thoth as an ibis (Glencairn Museum E1121).

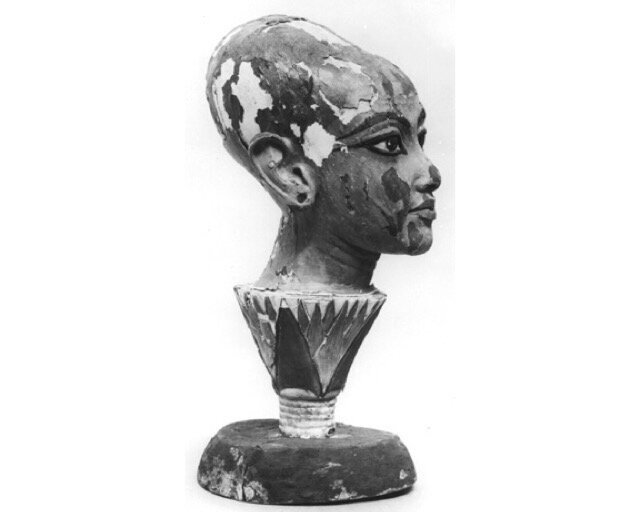

Figure 7. In this statuette from the tomb of Tutankhamun, the boy king is shown as the newborn sun god emerging from a lotus flower at the moment of creation (Cairo Museum JE 60723). Image courtesy of the Griffith Institute.

Figure 8. On this bracelet of Nimlot, the newborn sun god is shown as a child seated atop a lotus flower (EA14595). Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

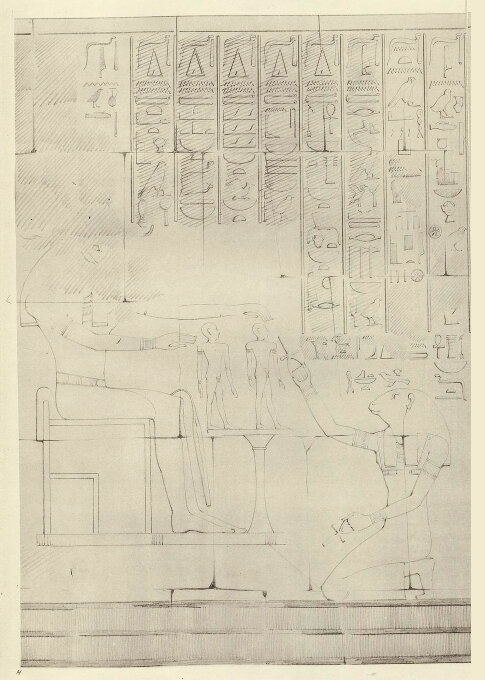

The importance of the sun in the creation of the world is highlighted in another creation myth that makes reference to a collective of gods known as the Heliopolitan Ennead (Figure 9). These nine deities (the Ennead) are mentioned in the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts. This myth seems to have originated at the city of Iunu (or Heliopolis, meaning “City of the Sun” in Greek). Here, the creation of the world begins with a creator god named Atum (or Re-Atum). Just as we see with the Hermopolitan version of creation, there is a chaotic, watery state of pre-creation, in which Atum resides before he is born. Atum is self-created and arises in the shape of an obelisk-like pillar (the benben ) in Heliopolis. He engenders by means of his own bodily fluids. To begin the creation of the world, Atum spits out a pair of divine beings: Shu, the god of air, and Tefnut, his female counterpart, the goddess of moisture (Figure 10).

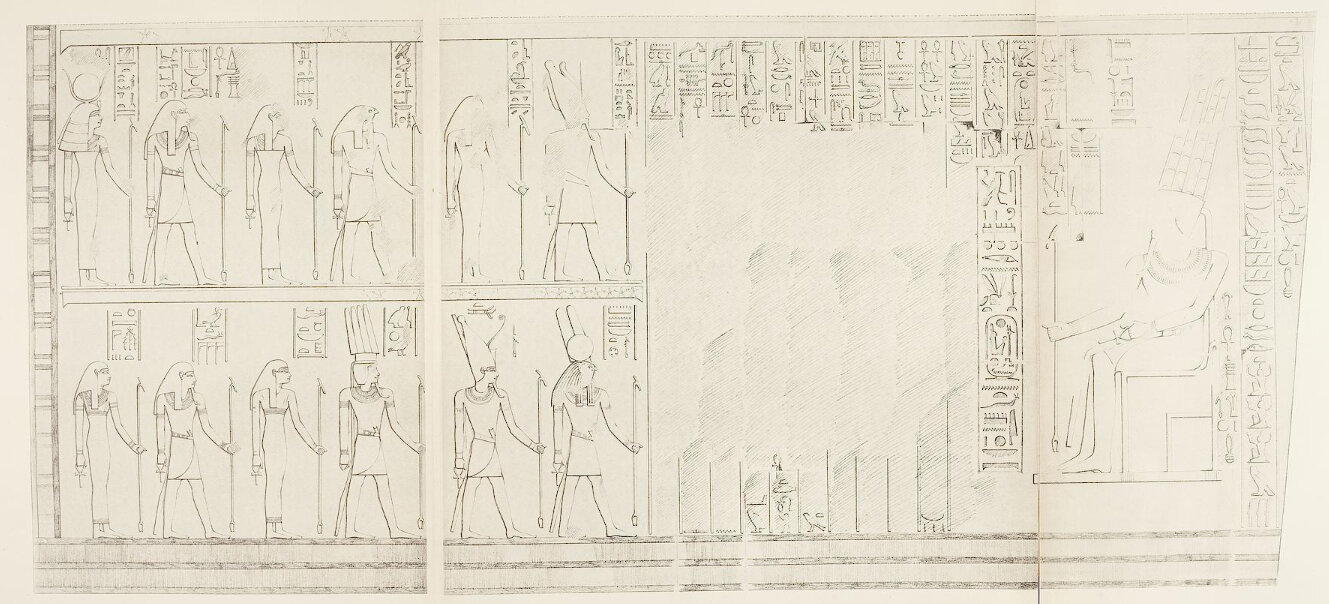

Figure 9. An illustration of a relief from the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el Bahri showing the members of the Ennead before Amun Re. This drawing appears in E. Naville, The Temple of Deir el Bahari , volume 2, London: Egypt Exploration Fund, 1896, pl. xlvi.

Figure 10. A faience amulet of the god Shu shown with upraised arms lifting up the sky (Glencairn Museum E453).

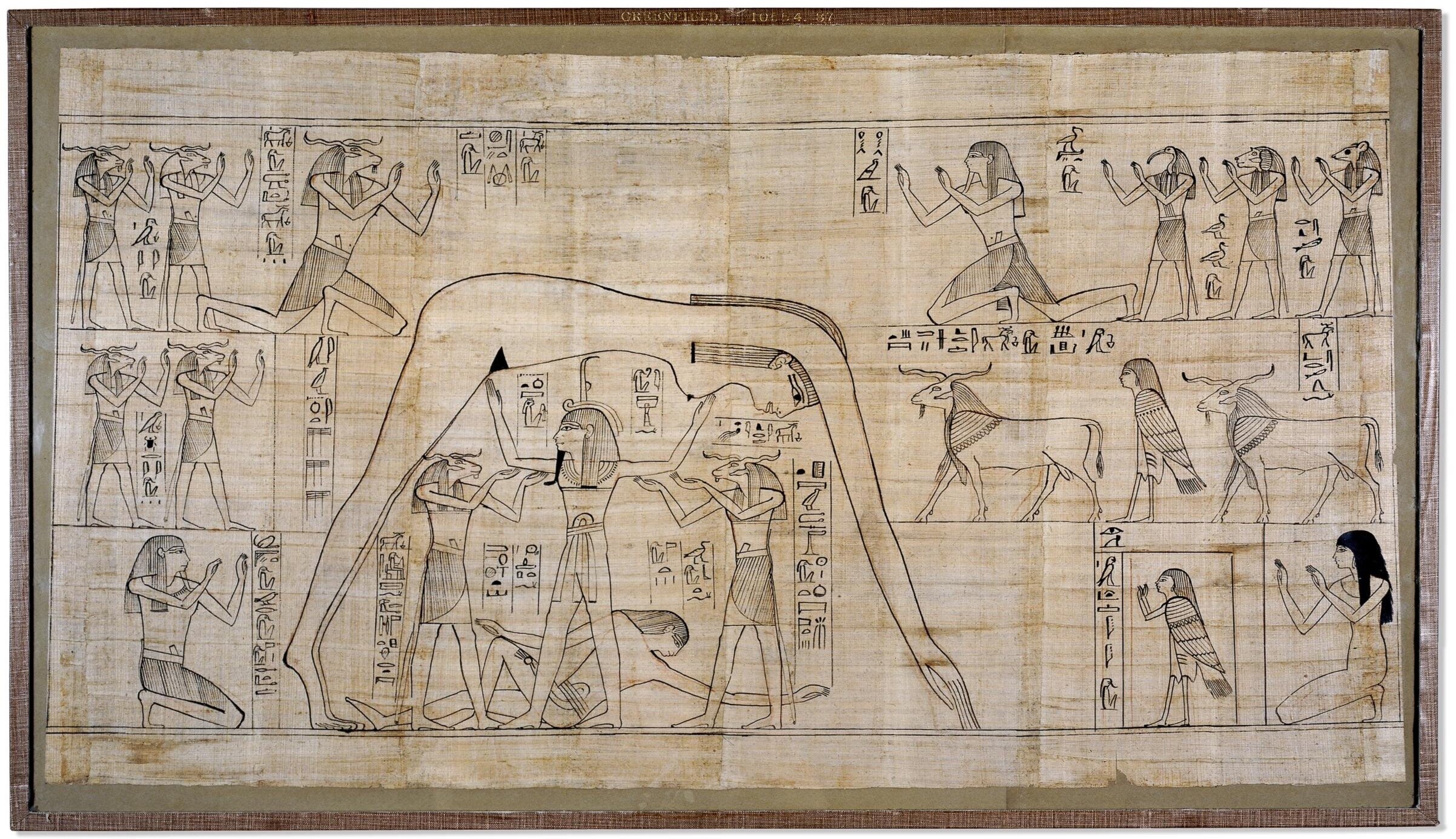

Shu and Tefnut in turn produce a second generation of gods. Their son, Geb, is the god of the earth, and his sister-wife, Nut, is the sky goddess. With this second generation, the Egyptian cosmos comes into existence and all the elements necessary for life on earth—the sun, air, moisture, land, and sky—are now in place. The iconography of Geb and Nut together is particularly evocative (Figure 11). Geb appears as a human male lying on the ground. Arched above him, separated by their father Shu, stretches the figure of his sister-wife Nut, often shown as a nude female whose body is covered in stars. The Egyptians envisioned her arms and legs as the pillars of the sky and each of her limbs as indicators of the four cardinal points. Before their separation by their father, Geb and Nut were able to produce another generation of gods: Isis, Osiris, Seth, and Nephthys. Isis (Figure 12) and Osiris (Figure 13) in turn produced Horus. (It is interesting to consider that the Heliopolitan genealogy can also be viewed as the family tree of the Egyptian king (Figure 14). Each king was considered a representative of Horus while he was alive, and was then associated with the god Osiris, the king of the dead, after his death.)

Figure 11. The Egyptian version of the cosmos as seen on this drawing from the Book of the Dead of Nestanebetisheru. Here Shu, the god of air, separates the earth god Geb from the sky goddess Nut (EA10554,87). Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 12. Figurine of Isis, member of the Heliopolitan Ennead, suckling Horus (Glencairn Museum E1164).

Figure 13. Figurine of Osiris, member of the Heliopolitan Ennead (Glencairn Museum E74).

Figure 14. The family tree of the Heliopolitan Ennead.

In addition to their roles in the creation of the cosmos, members of the Ennead are involved in other cycles of life and rebirth. For example, the sky goddess Nut is believed to give birth to the sun each day, and in some traditions she also gives birth to the stars. When observing the nighttime sky, the Egyptians may have noticed that the outer arm of the Milky Way resembled a female form and identified this celestial feature with the goddess Nut. As a goddess responsible for the sun’s daily rebirth, Nut was also accorded a role in the resurrection of the dead. Representations of Nut on the ceilings of New Kingdom (1539–1075 BCE) royal tombs show the goddess with the sun entering her mouth and passing through her star-covered body during the night, to be reborn in the morning. She often appears on the inside lids of sarcophagi, protecting the deceased until he or she, like the sun god Re, would be reborn. Nut can also appear on the lids of coffins as a woman with wings spread protectively across the chest of the deceased (Figure 15).

Figure 15. The goddess Nut on the lid of the coffin of Sema-tawy-iirdis (Glencairn Museum E1267).

A third version of the creation of the cosmos can be found in a text known as the Memphite Theology. Memphis was one of the most important cities in ancient Egyptian history. Situated along the Nile at the point where the Nile River branches out into the Nile Delta, Memphis was Egypt’s first capital city. Throughout Egypt’s long history, Memphis remained an important religious and administrative center even during times when its status as the country’s capital city had shifted. According to the historian Manetho, Memphis was founded by the legendary king Menes around 3200 BCE. The divine triad who protected the city consisted of Ptah, his consort Sekhmet, and their child, Nefertem (Figure 16). Ptah was the patron deity of craftsmen, and in the Memphite version of creation he plays the role of the primary creator god (see also lead photo above).

Figure 16. Members of the Memphite triad, the patron deities of Memphis (Glencairn Museum E113, E967, E905).

Unlike the versions of creation expressed in the Hermopolitan and Heliopolitan creation myths, which have been reconstructed from various ancient religious texts, the Memphite creation myth is preserved on a single document known as the Shabaka Stone, which is now preserved in the British Museum (Figure 17). The text inscribed on this monument relates how King Shabaka, a Nubian pharaoh of Egypt’s 25th Dynasty (705–690 BCE), found a worm-eaten papyrus in the library of the Temple of Ptah at Memphis. Realizing how important the damaged document was, Shabaka purportedly ordered that the words be carved anew in stone to preserve them. In this text Ptah (Figure 18) is credited with the creation of the world. He creates by means of thought and words: “Sight, hearing, breathing—they report to the heart, and it makes every understanding come forth. As to the tongue, it repeats what the heart has devised. Thus all the gods were born and his Ennead was completed. For every word of the god came about through what the heart devised and the tongue commanded.” The text describes how Ptah was responsible for the creation of all the gods and the establishment of their worship throughout Egypt:

“He gave birth to the gods. He made the towns, He established the nomes, He placed the gods in their shrines, He settled their offerings, He established their shrines, He made their bodies according to their wishes. Thus the gods entered into their bodies, Of every wood, every stone, every clay, Everything that grows upon him In which they came to be. Thus were gathered to him all the gods and their kas, Content, united with the Lord of the Two Lands.”

Figure 17. The Shabaka Stone, a basalt slab inscribed with the text of the Memphite Theology. The stone was later used as a millstone, which explains some of the damage to its surface (EA498). Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 18. A representation of the god Ptah on the stela of Maienhekau (Glencairn Museum E1266). Ptah is shown with his characteristic skull cap.

Reference to the moment of creation is not only seen in Egyptian texts. Most temples have architectural features that mimic elements of the cosmos at the beginning of creation. A large gateway called a pylon usually fronts a temple (Figure 19). The form of the pylon consists of two tapering towers joined by a lower section. The shape of the pylon imitates the hieroglyph for the word “horizon” ( akhet ), represented as two hills with a sun disk in the center. Further adding to the solar imagery, a pair of obelisks often stands before the entrance to the temple. An obelisk is a four-sided standing stone that tapers as it rises and ends in a small pyramid called a “pyramidion.” Obelisks were sacred to the sun god and were a symbol of the sun related to the benben , which calls to mind the primordial mound described in the Heliopolitan and Hermopolitan creation myths.

Figure 19. A view of the temple pylon at Philae Temple. Photo courtesy of Marc Ryckaert.

Figure 20. A view of papyriform and lotiform columns in the temple of Kom Ombo. Photo courtesy of Marie Thérèse Hébert & Jean Robert Thibault.

Each temple was a microcosm of the world wherein the creation was repeated on a daily basis. Beyond the entrance pylon, the typical temple contained one or more open courts, a hypostyle hall, and, at the innermost space, the sanctuary. The columns found throughout the temple often had capitals that are papyriform or lotiform in design, echoing the marshy plants that emerged on the primeval mound (Figure 20). The dark sanctuary or shrine that housed the image of the temple’s resident god imitated the mound upon which creation began. When priests carried out the morning rituals and opened the god’s shrine, they reenacted the very moment of creation, and the temple’s resident deity took the position of the creator god. Many temple precincts are also bounded by walls whose bricks are laid in a wavy design, perhaps symbolizing the chaotic waters of pre-creation which are held at bay by the creation of the (primordial) mound upon which the temple structure was built.

In addition to the creator gods depicted in the three main creation myths, there are other deities who were also considered creator gods such as Min, Amun, Khnum, and the Aten. One of Egypt’s earliest known deities was the god Min (Figure 21). Depictions of him appear as early as the Predynastic Period. Three colossal statues of Min dating to around 3300 BCE were excavated by W.M.F. Petrie at the site of Coptos. These statues, while fragmentary, originally depicted this god with the erect phallus that became standard for his representations. As a god connected with fertility and creation, Min is usually shown in this distinctive ithyphallic pose. He grasps a flail in one upraised arm and wears a tall plumed crown very similar to that of Amun-Re.

Figure 21. The god Min (EA60045). Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

A member of the Hermopolitan Ogdoad, Amun’s name means “the hidden one.” During the Middle Kingdom (c. 1945-1640 BCE) this god became increasingly important, and by the New Kingdom he rose to prominence as a state god and was given the epithet “king of the gods.” Amun, together with his consort Mut, and their child, Khonsu, comprise the Theban triad, the patron deities of the city of Thebes (Figure 22). At the same time, Amun (or his combined form, Amun-Re) became thought of as a creator god in his own right. Amun was usually shown as a human, and when he was in the form of Amun-Re he wore a crown with two tall plumes. The ram and the goose were animals sacred to him.

Figure 22. A bronze statuette of the god Amun (right, Glencairn Museum E1165) and his consort Mut (Glencairn Museum E1145).

The ram-headed god Khnum is described in the Coffin Texts, a collection of funerary spells composed around 1991-1786 BCE, as a creator of humans and animals (Figure 23). By the reign of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut (reigned 1479-1458 BCE), Khnum is described as a god who is responsible for fashioning gods, humans, and animals on a potter’s wheel (Figure 24).

Figure 23. Relief showing the ram-headed god Khnum (EA635). Image © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 24. An illustration of a relief from the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el Bahri showing Khnum creating Hatshepsut and her ka on a potter’s wheel. This drawing appears in E. Naville, The Temple of Deir el Bahari , volume 2, London: Egypt Exploration Fund, 1896, pl. xlviii.

Figure 25. The Aten appears at the top of this relief fragment above a figure of King Akhenaten. Unlike other Egyptian deities, the Aten does not take a human or animal form. This deity is shown as a sun disk with rays that end in tiny hands (UPMAA E16230). Image courtesy of the Penn Museum.

During the Amarna Period, when the pharaoh Akhenaten (reigned 1353-1336 BCE) changed the religious system from a polytheistic one to one that approached monotheism, his chosen deity, the Aten, naturally took position as creator god (Figure 25). The Aten was a solar deity, and his role in creation is celebrated in hymns composed during this period. In one version, the Aten is praised and described as follows. (It is interesting to note that scholars have long observed the similarity of this hymn to the phraseology of Psalm 104 in the Bible): “How numerous are your works, though hidden from sight. Unique god, there is none beside him. You mold the earth to your wish, you and you alone. All people, herds and flocks, All on earth that walk on legs, All on high that fly with their wings. And on the foreign lands of Khar and Kush, the land of Egypt You place every man in his place, you make what they need, so that everyone has his food, his lifespan counted.”

This religious experiment did not last long beyond the death of Akhenaten. By the beginning years of the reign of Tutankhamun, the traditional religious system with its many gods had been restored and the Aten returned to being just one of many solar deities in the Egyptian pantheon.

As we can see, there was no one single creation story in Egyptian religious tradition. There were several different ways in which the Egyptians explained the origin of the world. These various traditions were not mutually exclusive. They often complimented and intersected each other, yet distinctions can be drawn amongst the various creation myths, which helps to distinguish one from the other.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD Associate Curator, Egyptian Section, Penn Museum University of Pennsylvania

Select Bibliography

Andrews, Carol. 1994. Amulets of ancient Egypt . London: The British Museum Press.

Lichtheim, Miriam. 1976. Ancient Egyptian literature: a book of readings. Vol. 2. The New Kingdom . Berkeley/London.

O’ Rourke, Paul. 2001. “Khnum.” In Donald B. Redford (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt , vol. 2: 231-232. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Romanosky, Eugene. 2001. “Min.” In Donald B. Redford (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt , vol. 2: 413-415. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schlögl, Hermann A. 2001. “Aten.” In Donald B. Redford (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt , vol. 1: 1156-158. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simpson, William Kelly (ed.) 2003. The literature of ancient Egypt: an anthology of stories, instructions, stelae, autobiographies, and poetry , third ed. New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

Tobin, Vincent A. 2001. “Amun and Amun-Re.” In Donald B. Redford (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt , vol. 1: 82-85. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tobin, Vincent A. 2001. “Myths: Creation Myths.” In Donald B. Redford (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt , vol. 2: 469-472. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilkinson, Richard H. 2003. The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egyp t. London: Thames & Hudson.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here .

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Nature and significance

- Creation by a supreme being

- Creation through emergence

- Creation by world parents

- Creation from the cosmic egg

- Creation by earth divers

- Primordiality

- Dualisms and antagonisms

- Creation and sacrifice

- Transcendence and otherness

- Creation through emanations

- The unknowability of creation

- Hartshorne and Reese

creation myth

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Ancient Origins - 10 of the Wildest Creation Myths in History

- Live Science - The Top 10 Intelligent Designs (or Creation Myths)

- Academia - ANCIENT EGYPTIAN COSMOGONIC MYTHS

- Learn Religions - Creation Myths from Around the World

- Table Of Contents

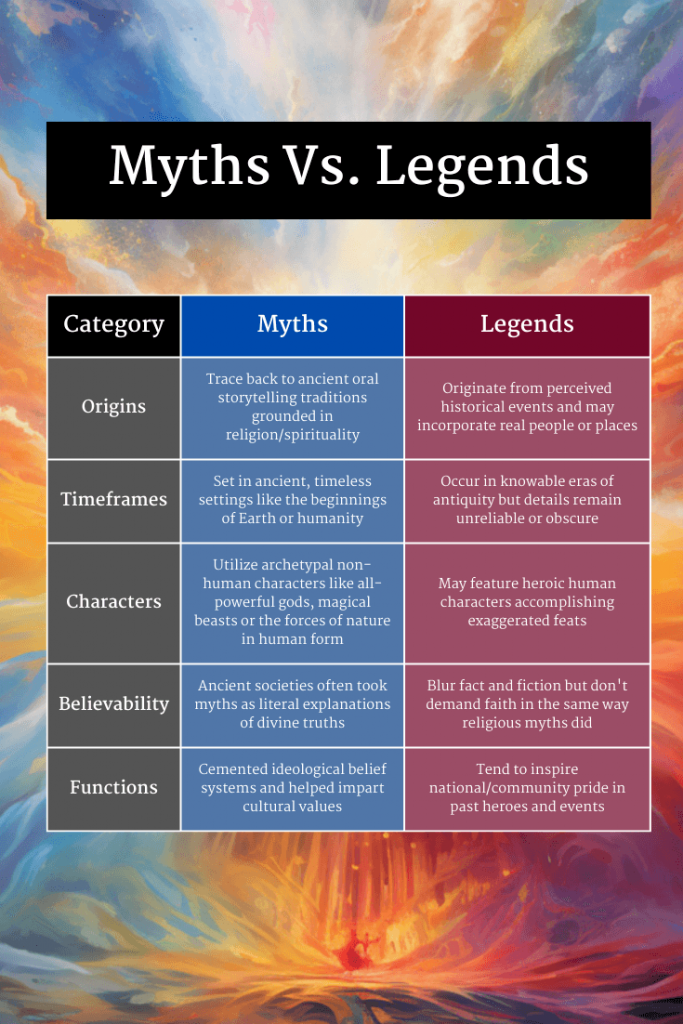

creation myth , philosophical and theological elaboration of the primal myth of creation within a religious community . The term myth here refers to the imaginative expression in narrative form of what is experienced or apprehended as basic reality ( see also myth ). The term creation refers to the beginning of things, whether by the will and act of a transcendent being, by emanation from some ultimate source, or in any other way.

The myth of creation is the symbolic narrative of the beginning of the world as understood by a particular community. The later doctrines of creation are interpretations of this myth in light of the subsequent history and needs of the community. Thus, for example, all theology and speculation concerning creation in the Christian community are based on the myth of creation in the biblical book of Genesis and of the new creation in Jesus Christ . Doctrines of creation are based on the myth of creation, which expresses and embodies all of the fertile possibilities for thinking about this subject within a particular religious community.

Myths are narratives that express the basic valuations of a religious community. Myths of creation refer to the process through which the world is centred and given a definite form within the whole of reality. They also serve as a basis for the orientation of human beings within the world. This centring and orientation specify humanity’s place in the universe and the regard that humans must have for other humans, nature, and the entire nonhuman world; they set the stylistic tone that tends to determine all other gestures, actions, and structures in the culture . The cosmogonic (origin of the world) myth is the myth par excellence. In this sense, the myth is akin to philosophy, but, unlike philosophy, it is constituted by a system of symbols; and because it is the basis for any subsequent cultural thought, it contains rational and nonrational forms. There is an order and structure to the myth, but this order and structure is not to be confused with rational, philosophical order and structure. The myth possesses its own distinctive kind of order.

Myths of creation have another distinctive character in that they provide both the model for nonmythic expression in the culture and the model for other cultural myths. In this sense, one must distinguish between cosmogonic myths and myths of the origin of cultural techniques and artifacts . Insofar as the cosmogonic myth tells the story of the creation of the world, other myths that narrate the story of a specific technique or the discovery of a particular area of cultural life take their models from the stylistic structure of the cosmogonic myth. These latter myths may be etiological (i.e., explaining origins); but the cosmogonic myth is never simply etiological, for it deals with the ultimate origin of all things.

The cosmogonic myth thus has a pervasive structure; its expression in the form of philosophical and theological thought is only one dimension of its function as a model for cultural life. Though the cosmogonic myth does not necessarily lead to ritual expression, ritual is often the dramatic presentation of the myth. Such dramatization is performed to emphasize the permanence and efficacy of the central themes of the myth, which integrates and undergirds the structure of meaning and value in the culture. The ritual dramatization of the myth is the beginning of liturgy, for the religious community in its central liturgy attempts to re-create the time of the beginning.

From this ritual dramatization the notion of time is established within the religious community. To be sure, in most communities there is the notion of a sacred and a profane time. The prestige of the cosmogonic myth establishes sacred or real time. It is this time that is most efficacious for the life of the community. Dramatization of sacred time enables the community to participate in a time that has a different quality than ordinary time, which tends to be neutral. All significant temporal events are spoken of in the language of the cosmogonic myth, for only by referring them to this primordial model will they have significance.

In like manner, artistic expression in archaic or “ primitive ” societies, often related to ritual presentation, is modelled on the structure of the cosmogonic myth. The masks, dances, and gestures are, in one way or another, aspects of the structure of the cosmogonic myth. This meaning may also extend to the tools that people use in the making of artistic designs and to the precise technique they employ in the craft.

Mention has been made above of the fact that the cosmogonic myth situates humankind in a place, in space. This centring is at once symbolic and empirical : symbolic because through symbols it defines the spatiality of human beings in ontological terms (of being) and empirical because it orients them in a definite landscape. Indeed, the names given to the flora and fauna and to the topography are a part of the orientation of humans in a space. The subsequent development of language within a human community is an extension of the language of the cosmogonic myth.

The initial ordering of the world through the cosmogonic myth serves as the primordial structure of culture and the articulation of the embryonic forms and styles of cultural life out of which various and differing forms of culture emerge. The recollection and celebration of the myth enable the religious community to think of and participate in the fundamentally real time, space, and mode of orientation that enables them to define their cultural life in a specific manner.

Home — Essay Samples — Religion — Creation Myth — The Importance of Creation Myths

The Importance of Creation Myths

- Categories: Creation Myth History of Education

About this sample

Words: 649 |

Published: Mar 20, 2024

Words: 649 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Historical and cultural significance, psychological and sociological implications, understanding cultural diversity, contemporary relevance.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Religion Education

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 639 words

3 pages / 1323 words

1 pages / 574 words

10 pages / 4687 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Creation Myth

The Celtic culture is rich with myths and legends that have been passed down through generations. One of the most fascinating aspects of Celtic mythology is the creation myths that explain how the world and everything in it came [...]

The divine creation theory stands as a profound paradigm that seeks to bridge the realms of science and spirituality, offering insights into the origins and purpose of existence. This theory posits that the universe, life, and [...]

When it comes to the origin of life, creationism and evolution stand out for their differing views. Creationism is a religious theory that God created everything in the universe, while evolution is based on scientific principles [...]

The Apache people, indigenous to the American Southwest, have a rich and complex oral tradition that includes a variety of myths and legends. Among these narratives, the Apache Creation Myth stands out as a central and [...]

Different cultures globally all have various creation narratives that they live by. With that in mind, the world was only made one time so many of these creation stories are very similar. From a Christianity perspective, they [...]

Pitch black in the dark void, there were two lonely gods: the Sun God, Ilios, and the Moon God, Taiga. They were disappointed they had no one to talk to, however, Ilios accepted the fact that he’s the only one in this solemn [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The Creation

In the beginning, there was only Chaos , the gaping emptiness. Then, either all by themselves or out of the formless void, sprang forth three more primordial deities: Gaea (Earth), Tartarus (the Underworld), and Eros (Love). Once Love was there, Gaea and Chaos – two female deities – were able to procreate and shape everything known and unknown in the universe.

The Children of Chaos and Gaea

Erebus and nyx.

Chaos gave birth to Erebus (Darkness) and Nyx (Night). Erebus slept with his sister Nyx , and out of this union Aether , the bright upper air, and Hemera , the Day, emerged. Afterward, feared by everyone but her brother, Night fashioned a family of haunting forces all by herself. Among others, her children included the hateful Moros (Fate), the black Ker (Doom), Thanatos (Death), Hypnos (Sleep), Oneiroi (Dreams), Geras (Old Age), Oizus (Pain), Nemesis (Revenge), Eris (Strife), Apate (Deceit), Philotes (Sexual Pleasure), Momos (Blame), and the Hesperides (the Daughters of the Evening).

Gaea and Uranus

Meanwhile, Gaea gave birth to Uranus , the Starry Sky. Uranus became Gaea's husband, surrounding her from all sides. Together, they produced three sets of children: the three one-eyed Cyclopes , the three Hundred-Handed Hecatoncheires , and the twelve Titans .

- Who were Zeus’ Lovers?

- How was the World created?

- What is the Trojan Horse?

The Castration of Uranus

However, Uranus was a cruel husband and an even crueler father. He hated his children and didn’t want to allow them to see the light of day. So, he imprisoned them into the hidden places of the earth, Gaea's womb. This angered Gaea, and she plotted with her sons against Uranus. She made a harpe , a great adamant sickle, and tried to incite her children to attack Uranus. All were too afraid, except the youngest Titan, Cronus .

Cronus Revenge