Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 10 September 2020

- Ulcerative colitis

- Taku Kobayashi 1 ,

- Britta Siegmund 2 ,

- Catherine Le Berre 3 ,

- Shu Chen Wei 4 ,

- Marc Ferrante 5 ,

- Bo Shen 6 ,

- Charles N. Bernstein 7 ,

- Silvio Danese 8 ,

- Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet 3 &

- Toshifumi Hibi 1

Nature Reviews Disease Primers volume 6 , Article number: 74 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

669 Citations

185 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Gastrointestinal diseases

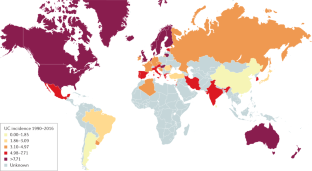

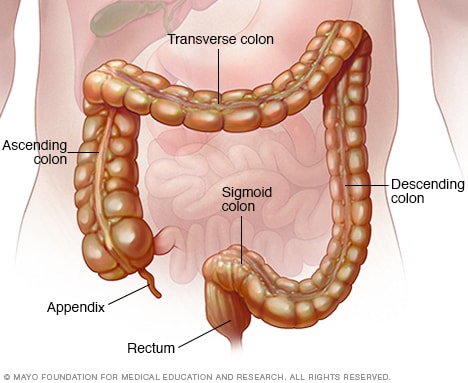

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease of unknown aetiology affecting the colon and rectum. Multiple factors, such as genetic background, environmental and luminal factors, and mucosal immune dysregulation, have been suggested to contribute to UC pathogenesis. UC has evolved into a global burden given its high incidence in developed countries and the substantial increase in incidence in developing countries. An improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying UC has led to the emergence of new treatments. Since the early 2000s, anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) treatment has significantly improved treatment outcomes. Advances in medical treatments have enabled a paradigm shift in treatment goals from symptomatic relief to endoscopic and histological healing to achieve better long-term outcomes and, consequently, diagnostic modalities have also been improved to monitor disease activity more tightly. Despite these improvements in patient care, a substantial proportion of patients, for example, those who are refractory to medical treatment or those who develop colitis-associated colorectal dysplasia or cancer, still require restorative proctocolectomy. The development of novel drugs and improvement of the treatment strategy by implementing personalized medicine are warranted to achieve optimal disease control. However, delineating the aetiology of UC is necessary to ultimately achieve disease cure.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

92,52 € per year

only 92,52 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Microscopic colitis

Crohn’s disease

Clinical factors associated with severity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Brazil based on 2-year national registry data from GEDIIB

Wilks, S. Morbid appearances in the intestine of Miss Bankes. Med. Gaz. 2 , 264–265 (1859). This paper is the first historical report of UC .

Google Scholar

Hibi, T. & Ogata, H. Novel pathophysiological concepts of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastroenterol. 41 , 10–16 (2006).

PubMed Google Scholar

Ungaro, R., Mehandru, S., Allen, P. B., Peyrin-Biroulet, L. & Colombel, J.-F. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 389 , 1756–1770 (2017).

Rubin, D. T., Ananthakrishnan, A. N., Siegel, C. A., Sauer, B. G. & Long, M. D. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 114 , 384–413 (2019). This paper describes the clinical guidelines on the management of UC recommended by the American College of Gastroenterology .

Matsuoka, K. et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastroenterol. 53 , 305–353 (2018).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Magro, F. et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and Ileo-anal pouch disorders. J. Crohns Colitis 11 , 649–670 (2017). Consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of UC by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation .

Truelove, S. C. & Witts, L. J. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. BMJ 2 , 1041–1048 (1955). This paper describes the results from a clinical trial on the use of steroids in UC .

Gallo, G., Kotze, P. G. & Spinelli, A. Surgery in ulcerative colitis: When? How? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 32–33 , 71–78 (2018).

Ungaro, R., Colombel, J.-F., Lissoos, T. & Peyrin-Biroulet, L. A treat-to-target update in ulcerative colitis: a systematic review. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 114 , 874–883 (2019).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Colombel, J.-F., D’haens, G., Lee, W.-J., Petersson, J. & Panaccione, R. Outcomes and strategies to support a treat-to-target approach in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J. Crohns Colitis 14 , 254–266 (2020).

Peyrin-Biroulet, L. et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110 , 1324–1338 (2015). Consensus statements on treat-to-target strategy in the management of UC .

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ozaki, R. et al. Histological risk factors to predict clinical relapse in ulcerative colitis with endoscopically normal mucosa. J. Crohn’s Colitis 12 , 1288–1294 (2018).

Peyrin-Biroulet, L., Bressenot, A. & Kampman, W. Histologic remission: the ultimate therapeutic goal in ulcerative colitis? Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12 , 929–934.e2 (2014).

Bernstein, C. N. et al. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: a population-based study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 101 , 1559–1568 (2006).

Bitton, A. et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Québec: recent trends. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 20 , 1770–1776 (2014).

Leddin, D., Tamim, H. & Levy, A. R. Decreasing incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Eastern Canada: a population database study. BMC Gastroenterol. 14 , 140 (2014).

Torabi, M. et al. Geographical variation and factors associated with inflammatory bowel disease in a Central Canadian province. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 26 , 581–590 (2020).

Coward, S. et al. Past and future burden of inflammatory bowel diseases based on modeling of population-based data. Gastroenterology 156 , 1345–1353.e4 (2019).

Ng, S. C. et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 390 , 2769–2778 (2017). A systematic review providing an overview of the global epidemiology of IBD .

Ng, S. C. et al. Population density and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective population-based study in 13 countries or regions in Asia-Pacific. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 114 , 107–115 (2019).

Banerjee, R. et al. IBD in India: similar phenotype but different demographics than the west. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000001282 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Kedia, S. & Ahuja, V. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in India: the Great Shift East. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2 , 102–115 (2017).

Perminow, G. et al. A characterization in childhood inflammatory bowel disease, a new population-based inception cohort from South-Eastern Norway, 2005–07, showing increased incidence in Crohn’s disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 44 , 446–456 (2009).

Malmborg, P., Grahnquist, L., Lindholm, J., Montgomery, S. & Hildebrand, H. Increasing incidence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in northern Stockholm county, 2002–2007. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 57 , 29–34 (2013).

Benchimol, E. I. et al. Trends in epidemiology of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: distributed network analysis of multiple population-based provincial health administrative databases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112 , 1120 (2017).

Muise, A. M., Snapper, S. B. & Kugathasan, S. The age of gene discovery in very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 143 , 285–288 (2012).

Shah, S. C. et al. Sex-based differences in incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases—pooled analysis of population-based studies from western countries. Gastroenterology 155 , 1079–1089.e3 (2018).

Benchimol, E. I. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in immigrants to Canada and their children: a population-based cohort study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110 , 553–563 (2015).

Ananthakrishnan, A. N. Environmental triggers for inflammatory bowel disease. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 15 , 302 (2013).

Bernstein, C. N. et al. World gastroenterology organisation global guidelines inflammatory bowel disease: update August 2015. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 50 , 803–818 (2016).

Wang, P. et al. Smoking and inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison of China, India, and the USA. Dig. Dis. Sci. 63 , 2703–2713 (2018).

Amarapurkar, A. D. et al. Risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective multi-center study. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 37 , 189–195 (2018).

Lerner, A. & Matthias, T. Changes in intestinal tight junction permeability associated with industrial food additives explain the rising incidence of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 14 , 479–489 (2015).

Wang, Y.-F. et al. Multicenter case-control study of the risk factors for ulcerative colitis in China. World J. Gastroenterol. 19 , 1827–1833 (2013).

Benchimol, E. I. et al. Rural and urban residence during early life is associated with risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based inception and birth cohort study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112 , 1412–1422 (2017).

Ungaro, R. et al. Antibiotics associated with increased risk of new-onset Crohn’s disease but not ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 109 , 1728–1738 (2014).

Lewis, J. D. & Abreu, M. T. Diet as a trigger or therapy for inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 152 , 398–414.e6 (2017).

Marrie, R. A. et al. Rising incidence of psychiatric disorders before diagnosis of immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 28 , 333–342 (2019).

Bonaz, B. L. & Bernstein, C. N. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 144 , 36–49 (2013).

Myrelid, P., Landerholm, K., Nordenvall, C., Pinkney, T. D. & Andersson, R. E. Appendectomy and the risk of colectomy in ulcerative colitis: a national cohort study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112 , 1311–1319 (2017).

Parian, A. et al. Appendectomy does not decrease the risk of future colectomy in UC: results from a large cohort and meta-analysis. Gut 66 , 1390–1397 (2017).

Eaden, J. A., Abrams, K. R. & Mayberry, J. F. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut 48 , 526–535 (2001).

Olén, O. et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet 395 , 123–131 (2020).

Bernstein, C. N. et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: extra-intestinal diseases in IBD. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2 , S73–S80 (2019).

Desai, D. et al. Colorectal cancers in ulcerative colitis from a low-prevalence area for colon cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 21 , 3644–3649 (2015).

Wang, Y. N. et al. Clinical characteristics of ulcerative colitis-related colorectal cancer in Chinese patients. J. Dig. Dis. 18 , 684–690 (2017).

Keller, D. S., Windsor, A., Cohen, R. & Chand, M. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: review of the evidence. Tech. Coloproctol. 23 , 3–13 (2019).

Moody, G. A., Jayanthi, V., Probert, C. S., Mac Kay, H. & Mayberry, J. F. Long-term therapy with sulphasalazine protects against colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a retrospective study of colorectal cancer risk and compliance with treatment in Leicestershire. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 8 , 1179–1183 (1996).

Eaden, J., Abrams, K., Ekbom, A., Jackson, E. & Mayberry, J. Colorectal cancer prevention in ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 14 , 145–153 (2000).

Bye, W. A., Nguyen, T. M., Parker, C. E., Jairath, V. & East, J. E. Strategies for detecting colon cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9 , CD000279 (2017).

Turpin, W., Goethel, A., Bedrani, L. & Croitoru Mdcm, K. Determinants of IBD Heritability: Genes, Bugs, and More. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 24 , 1133–1148 (2018).

Jostins, L. et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 491 , 119–124 (2012). A study of genetics reporting 163 disease susceptibility loci for IBD .

Mirkov, M. U., Verstockt, B. & Cleynen, I. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease: beyond NOD2. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2 , 224–234 (2017).

Spehlmann, M. E. et al. Risk factors in German twins with inflammatory bowel disease: results of a questionnaire-based survey. J. Crohns Colitis 6 , 29–42 (2012).

Halfvarson, J., Bodin, L., Tysk, C., Lindberg, E. & Järnerot, G. Inflammatory bowel disease in a Swedish twin cohort: a long-term follow-up of concordance and clinical characteristics. Gastroenterology 124 , 1767–1773 (2003).

Ng, S. C., Woodrow, S., Patel, N., Subhani, J. & Harbord, M. Role of genetic and environmental factors in British twins with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18 , 725–736 (2012).

van Dongen, J., Slagboom, P. E., Draisma, H. H. M., Martin, N. G. & Boomsma, D. I. The continuing value of twin studies in the omics era. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13 , 640–653 (2012).

Cleynen, I. et al. Inherited determinants of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis phenotypes: a genetic association study. Lancet 387 , 156–167 (2016).

Kredel, L. I. et al. T-cell composition in ileal and colonic creeping fat - separating ileal from colonic Crohn’s disease. J. Crohns Colitis 13 , 79–91 (2019).

Yoshitake, S., Kimura, A., Okada, M., Yao, T. & Sasazuki, T. HLA class II alleles in Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Tissue Antigens 53 , 350–358 (1999).

Inoue, N. et al. Lack of common NOD2 variants in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 123 , 86–91 (2002).

Martini, E., Krug, S. M., Siegmund, B., Neurath, M. F. & Becker, C. Mend your fences: the epithelial barrier and its relationship with mucosal immunity in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4 , 33–46 (2017).

Van Klinken, B. J., Van der Wal, J. W., Einerhand, A. W., Büller, H. A. & Dekker, J. Sulphation and secretion of the predominant secretory human colonic mucin MUC2 in ulcerative colitis. Gut 44 , 387–393 (1999).

Gitter, A. H., Wullstein, F., Fromm, M. & Schulzke, J. D. Epithelial barrier defects in ulcerative colitis: characterization and quantification by electrophysiological imaging. Gastroenterology 121 , 1320–1328 (2001).

Büning, C. et al. Increased small intestinal permeability in ulcerative colitis: rather genetic than environmental and a risk factor for extensive disease? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18 , 1932–1939 (2012).

Kaser, A., Adolph, T. E. & Blumberg, R. S. The unfolded protein response and gastrointestinal disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 35 , 307–319 (2013).

Grootjans, J., Kaser, A., Kaufman, R. J. & Blumberg, R. S. The unfolded protein response in immunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16 , 469–484 (2016).

Krug, S. M. et al. Tricellulin is regulated via interleukin-13-receptor α2, affects macromolecule uptake, and is decreased in ulcerative colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 11 , 345–356 (2018).

Neurath, M. F. Targeting immune cell circuits and trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Immunol. 20 , 970–979 (2019).

Jorch, S. K. & Kubes, P. An emerging role for neutrophil extracellular traps in noninfectious disease. Nat. Med. 23 , 279–287 (2017).

Bennike, T. B. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ulcerative colitis: a proteome analysis of intestinal biopsies. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 21 , 2052–2067 (2015).

Dinallo, V. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps sustain inflammatory signals in ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 13 , 772–784 (2019).

Camoglio, L., Te Velde, A. A., Tigges, A. J., Das, P. K. & Van Deventer, S. J. Altered expression of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 4 , 285–290 (1998).

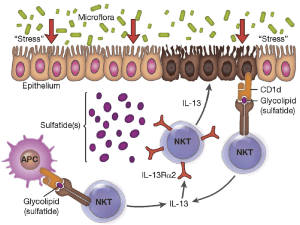

Heller, F. et al. Interleukin-13 is the key effector Th2 cytokine in ulcerative colitis that affects epithelial tight junctions, apoptosis, and cell restitution. Gastroenterology 129 , 550–564 (2005).

Heller, F., Fuss, I. J., Nieuwenhuis, E. E., Blumberg, R. S. & Strober, W. Oxazolone colitis, a Th2 colitis model resembling ulcerative colitis, is mediated by IL-13-producing NK-T cells. Immunity 17 , 629–638 (2002).

Danese, S. et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe UC: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIa study. Gut 64 , 243–249 (2015).

Kindler, V., Sappino, A. P., Grau, G. E., Piguet, P. F. & Vassalli, P. The inducing role of tumor necrosis factor in the development of bactericidal granulomas during BCG infection. Cell 56 , 731–740 (1989).

Lissner, D. et al. Monocyte and M1 macrophage-induced barrier defect contributes to chronic intestinal inflammation in IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 21 , 1297–1305 (2015).

Hanauer, S. B. et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet 359 , 1541–1549 (2002).

Rutgeerts, P. et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 353 , 2462–2476 (2005). This study is the first phase III randomized, controlled clinical trial of an anti-TNF agent for UC .

Uhlig, H. H. et al. Differential activity of IL-12 and IL-23 in mucosal and systemic innate immune pathology. Immunity 25 , 309–318 (2006).

Kobayashi, T. et al. IL23 differentially regulates the Th1/Th17 balance in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut 57 , 1682–1689 (2008).

Feagan, B. G. et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 375 , 1946–1960 (2016).

Sands, B. E. et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 381 , 1201–1214 (2019).

Gerlach, K. et al. TH9 cells that express the transcription factor PU.1 drive T cell-mediated colitis via IL-9 receptor signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. Nat. Immunol. 15 , 676–686 (2014).

Nishida, A. et al. Increased expression of interleukin-36, a member of the interleukin-1 cytokine family, in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22 , 303–314 (2016).

Russell, S. E. et al. IL-36α expression is elevated in ulcerative colitis and promotes colonic inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 9 , 1193–1204 (2016).

Scheibe, K. et al. Inhibiting interleukin 36 receptor signaling reduces fibrosis in mice with chronic intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology 156 , 1082–1097.e11 (2019).

Gordon, I. O. et al. Fibrosis in ulcerative colitis is directly linked to severity and chronicity of mucosal inflammation. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 47 , 922–939 (2018).

Harusato, A. et al. IL-36γ signaling controls the induced regulatory T cell-Th9 cell balance via NFκB activation and STAT transcription factors. Mucosal Immunol. 10 , 1455–1467 (2017).

Sonnenburg, J. L. & Bäckhed, F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 535 , 56–64 (2016).

Machiels, K. et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 63 , 1275–1283 (2014).

Halfvarson, J. et al. Dynamics of the human gut microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Microbiol. 2 , 17004 (2017).

Schulthess, J. et al. The short chain fatty acid butyrate imprints an antimicrobial program in macrophages. Immunity 50 , 432–445.e7 (2019).

Moayyedi, P. et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 149 , 102–109.e6 (2015).

Paramsothy, S. et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 389 , 1218–1228 (2017).

Rossen, N. G. et al. Findings from a randomized controlled trial of fecal transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 149 , 110–118.e4 (2015).

Zheng, L. et al. Microbial-derived butyrate promotes epithelial barrier function through IL-10 receptor-dependent repression of claudin-2. J. Immunol. 199 , 2976–2984 (2017).

Glauben, R. et al. Histone hyperacetylation is associated with amelioration of experimental colitis in mice. J. Immunol. 176 , 5015–5022 (2006).

Fischer, A. et al. Differential effects of α4β7 and GPR15 on homing of effector and regulatory T cells from patients with UC to the inflamed gut in vivo. Gut 65 , 1642–1664 (2016).

Feagan, B. G. et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 369 , 699–710 (2013).

Wei, S.-C. et al. Management of ulcerative colitis in Taiwan: consensus guideline of the Taiwan society of inflammatory bowel disease. Intest. Res. 15 , 266–284 (2017).

Fausel, R. A., Kornbluth, A. & Dubinsky, M. C. The first endoscopy in suspected inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 26 , 593–610 (2016).

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee. et al. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest. Endosc. 81 , 1101–1121.e1-13 (2015).

Chutkan, R. K., Scherl, E. & Waye, J. D. Colonoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest. Endosc. Clin. N. Am. 12 , 463–483 (2002).

Langner, C. et al. The histopathological approach to inflammatory bowel disease: a practice guide. Virchows Arch. 464 , 511–527 (2014).

Su, H.-J. et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and its treatment in 2018: global and Taiwanese status updates. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 118 , 1083–1092 (2019).

D’Haens, G. et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 132 , 763–786 (2007).

Schroeder, K. W., Tremaine, W. J. & Ilstrup, D. M. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N. Engl. J. Med. 317 , 1625–1629 (1987).

Peyrin-Biroulet, L. et al. Defining disease severity in inflammatory bowel diseases: current and future directions. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14 , 348–354.e17 (2016).

Fagerhol, M. K., Dale, I. & Andersson, T. A radioimmunoassay for a granulocyte protein as a marker in studies on the turnover of such cells. Bull. Eur. Physiopathol. Respir. 16 , 273–282 (1980).

Guerrant, R. L. et al. Measurement of fecal lactoferrin as a marker of fecal leukocytes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30 , 1238–1242 (1992).

van Rheenen, P. F., Van de Vijver, E. & Fidler, V. Faecal calprotectin for screening of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease: diagnostic meta-analysis. BMJ 341 , c3369 (2010).

Walsham, N. E. & Sherwood, R. A. Fecal calprotectin in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 9 , 21–29 (2016).

Lin, W.-C. et al. Fecal calprotectin correlated with endoscopic remission for Asian inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 21 , 13566–13573 (2015).

Menees, S. B., Powell, C., Kurlander, J., Goel, A. & Chey, W. D. A meta-analysis of the utility of C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, fecal calprotectin, and fecal lactoferrin to exclude inflammatory bowel disease in adults with IBS. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110 , 444–454 (2015).

Poullis, A., Foster, R., Northfield, T. C. & Mendall, M. A. Review article: faecal markers in the assessment of activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 16 , 675–681 (2002).

Sipponen, T. et al. Correlation of faecal calprotectin and lactoferrin with an endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease and histological findings. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 28 , 1221–1229 (2008).

Holtman, G. A. et al. Evaluation of point-of-care test calprotectin and lactoferrin for inflammatory bowel disease among children with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Fam. Pract. 34 , 400–406 (2017).

D’Haens, G. et al. Fecal calprotectin is a surrogate marker for endoscopic lesions in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18 , 2218–2224 (2012).

Reenaers, C. et al. Expert opinion for use of faecal calprotectin in diagnosis and monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease in daily clinical practice. United European Gastroenterol. J. 6 , 1117–1125 (2018).

Ministro, P. & Martins, D. Fecal biomarkers in inflammatory bowel disease: how, when and why? Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11 , 317–328 (2017).

Tibble, J. A., Sigthorsson, G., Foster, R., Forgacs, I. & Bjarnason, I. Use of surrogate markers of inflammation and Rome criteria to distinguish organic from nonorganic intestinal disease. Gastroenterology 123 , 450–460 (2002).

Hübenthal, M. et al. Sparse modeling reveals miRNA signatures for diagnostics of inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS ONE 10 , e0140155 (2015).

Zhang, H., Zeng, Z., Mukherjee, A. & Shen, B. Molecular diagnosis and classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 18 , 867–886 (2018).

Allocca, M. et al. Accuracy of Humanitas ultrasound criteria in assessing disease activity and severity in ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. J. Crohns Colitis 12 , 1385–1391 (2018).

Kinoshita, K. et al. Usefulness of transabdominal ultrasonography for assessing ulcerative colitis: a prospective, multicenter study. J. Gastroenterol. 54 , 521–529 (2019).

Sagami, S. et al. Transperineal ultrasound predicts endoscopic and histological healing in ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 51 , 1373–1383 (2020).

Okabayashi, S. et al. A simple 1-day colon capsule endoscopy procedure demonstrated to be a highly acceptable monitoring tool for ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 24 , 2404–2412 (2018).

Shi, H. Y. et al. A prospective study on second-generation colon capsule endoscopy to detect mucosal lesions and disease activity in ulcerative colitis (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 86 , 1139–1146.e6 (2017).

Li, J. & Leung, W. K. Colon capsule endoscopy for inflammatory bowel disease. J. Dig. Dis. 19 , 386–394 (2018).

Maeda, Y. et al. Fully automated diagnostic system with artificial intelligence using endocytoscopy to identify the presence of histologic inflammation associated with ulcerative colitis (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 89 , 408–415 (2019).

Ullman, T. A. & Itzkowitz, S. H. Intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology 140 , 1807–1816 (2011).

Watanabe, T. et al. Comparison of targeted vs random biopsies for surveillance of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 151 , 1122–1130 (2016).

Harbord, M. et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: current management. J. Crohns Colitis 11 , 769–784 (2017).

Van Assche, G., Vermeire, S. & Rutgeerts, P. Management of acute severe ulcerative colitis. Gut 60 , 130–133 (2011). Consensus guidelines on treatment of UC by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation .

Nguyen, G. C. et al. Consensus statements on the risk, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in inflammatory bowel disease: Canadian association of gastroenterology. Gastroenterology 146 , 835–848.e6 (2014).

Travis, S. P. et al. Predicting outcome in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut 38 , 905–910 (1996).

Higashiyama, M. et al. Management of elderly ulcerative colitis in Japan. J. Gastroenterol. 54 , 571–586 (2019).

Ruemmele, F. M. & Turner, D. Differences in the management of pediatric and adult onset ulcerative colitis — lessons from the joint ECCO and ESPGHAN consensus guidelines for the management of pediatric ulcerative colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 8 , 1–4 (2014).

Sturm, A. et al. European Crohn’s and Colitis organisation topical review on IBD in the elderly: table 1. J. Crohns Colitis https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw188 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Marteau, P. et al. Combined oral and enema treatment with Pentasa (mesalazine) is superior to oral therapy alone in patients with extensive mild/moderate active ulcerative colitis: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled study. Gut 54 , 960–965 (2005).

Sandborn, W. J. et al. Once-daily budesonide MMX® extended-release tablets induce remission in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis: results from the CORE I study. Gastroenterology 143 , 1218–1226.e2 (2012).

Herfarth, H. et al. Methotrexate is not superior to placebo in maintaining steroid-free response or remission in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 155 , 1098–1108.e9 (2018).

Nielsen, O. H., Steenholdt, C., Juhl, C. B. & Rogler, G. Efficacy and safety of methotrexate in the management of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. EClinicalMedicine 20 , 100271 (2020).

Colombel, J. F. et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 141 , 1194–1201 (2011).

Panaccione, R. et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 146 , 392–400.e3 (2014).

Sandborn, W. J. et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 142 , 257–265.e1–3 (2012).

Sandborn, W. J. et al. Subcutaneous golimumab induces clinical response and remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 146 , 85–95 (2014).

Colombel, J.-F. et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut 66 , 839–851 (2017).

Sands, B. E. et al. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 381 , 1215–1226 (2019).

Sandborn, W. J. et al. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab subcutaneous formulation in a randomized trial of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 158 , 562–572.e12 (2020).

Sandborn, W. J. et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 376 , 1723–1736 (2017).

FDA. FDA approves boxed warning about increased risk of blood clots and death with higher dose of arthritis and ulcerative colitis medicine tofacitinib (Xeljanz, Xeljanz XR). FDA https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-approves-boxed-warning-about-increased-risk-blood-clots-and-death-higher-dose-arthritis-and (2019).

Sandborn, W. J. et al. Venous thromboembolic events in the tofacitinib ulcerative colitis clinical development programme. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 50 , 1068–1076 (2019).

Samuel, S. et al. Cumulative incidence and risk factors for hospitalization and surgery in a population-based cohort of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 19 , 1858–1866 (2013).

Coakley, B. A., Telem, D., Nguyen, S., Dallas, K. & Divino, C. M. Prolonged preoperative hospitalization correlates with worse outcomes after colectomy for acute fulminant ulcerative colitis. Surgery 153 , 242–248 (2013).

Targownik, L. E., Singh, H., Nugent, Z. & Bernstein, C. N. The epidemiology of colectomy in ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based cohort. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 107 , 1228–1235 (2012).

Kaplan, G. G. et al. Decreasing colectomy rates for ulcerative colitis: a population-based time trend study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 107 , 1879–1887 (2012).

Eriksson, C. et al. Changes in medical management and colectomy rates: a population-based cohort study on the epidemiology and natural history of ulcerative colitis in Örebro, Sweden, 1963–2010. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 46 , 748–757 (2017).

Schineis, C. et al. Colectomy with ileostomy for severe ulcerative colitis-postoperative complications and risk factors. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 35 , 387–394 (2020).

Gu, J., Stocchi, L., Remzi, F. & Kiran, R. P. Factors associated with postoperative morbidity, reoperation and readmission rates after laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 15 , 1123–1129 (2013).

Madbouly, K. M. et al. Perioperative blood transfusions increase infectious complications after ileoanal pouch procedures (IPAA). Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 21 , 807–813 (2006).

Zittan, E. et al. Preoperative anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis is not associated with an increased risk of infectious and noninfectious complications after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22 , 2442–2447 (2016).

Mor, I. J. et al. Infliximab in ulcerative colitis is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Dis. Colon Rectum 51 , 1202–1207 (2008).

Selvasekar, C. R. et al. Effect of infliximab on short-term complications in patients undergoing operation for chronic ulcerative colitis. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 204 , 956–962 (2007).

Yung, D. E. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: vedolizumab and postoperative complications in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 24 , 2327–2338 (2018).

Gu, J., Remzi, F. H., Shen, B., Vogel, J. D. & Kiran, R. P. Operative strategy modifies risk of pouch-related outcomes in patients with ulcerative colitis on preoperative anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy. Dis. Colon Rectum 56 , 1243–1252 (2013).

Remzi, F. H. et al. Restorative proctocolectomy: an example of how surgery evolves in response to paradigm shifts in care. Colorectal Dis. 19 , 1003–1012 (2017).

Ahmed Ali, U. et al. Open versus laparoscopic (assisted) ileo pouch anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1 , CD006267 (2009).

Shen, B., Remzi, F. H., Lavery, I. C., Lashner, B. A. & Fazio, V. W. A proposed classification of ileal pouch disorders and associated complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6 , 145–158 (2008).

Garrett, J. W. & Drossman, D. A. Health status in inflammatory bowel disease. Biological and behavioral considerations. Gastroenterology 99 , 90–96 (1990).

De Dombal, F. T., Burton, I. & Goligher, J. C. The early and late results of surgical treatment for Crohn’s disease. Br. J. Surg. 58 , 805–816 (1971).

Guyatt, G. et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 96 , 804–810 (1989).

Love, J. R., Irvine, E. J. & Fedorak, R. N. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 14 , 15–19 (1992).

Irvine, E. J., Zhou, Q. & Thompson, A. K. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn’s relapse prevention trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 91 , 1571–1578 (1996).

Casellas, F., López-Vivancos, J., Vergara, M. & Malagelada, J. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on health-related quality of life. Dig. Dis. 17 , 208–218 (1999).

Lönnfors, S. et al. IBD and health-related quality of life – discovering the true impact. J. Crohns Colitis 8 , 1281–1286 (2014).

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 4 , 79 (2006).

PubMed Central Google Scholar

WHO. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). WHO http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/ (2018).

Cieza, A. & Stucki, G. The international classification of functioning disability and health: its development process and content validity. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 44 , 303–313 (2008).

Peyrin-Biroulet, L. et al. Disability in inflammatory bowel diseases: developing ICF core sets for patients with inflammatory bowel diseases based on the international classification of functioning, disability, and health. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 16 , 15–22 (2010).

Ananthakrishnan, A. N. et al. Permanent work disability in Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 103 , 154–161 (2008).

Thompson, P. W. & Pegley, F. S. A comparison of disability measured by the stanford health assessment questionnaire disability scales (HAQ) in male and female rheumatoid outpatients. Br. J. Rheumatol. 30 , 298–300 (1991).

Dasgupta, B. et al. Patient and physician expectations of add-on treatment with golimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: relationships between expectations and clinical and quality of life outcomes. Arthritis Care Res. 66 , 1799–1807 (2014).

CAS Google Scholar

Noseworthy, J. H., Vandervoort, M. K., Wong, C. J. & Ebers, G. C. Interrater variability with the expanded disability status scale (EDSS) and functional systems (FS) in a multiple sclerosis clinical trial. Neurology 40 , 971–975 (1990).

Butzkueven, H. et al. Efficacy and safety of natalizumab in multiple sclerosis: interim observational programme results. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 85 , 1190–1197 (2014).

Peyrin-Biroulet, L. et al. Development of the first disability index for inflammatory bowel disease based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Gut 61 , 241–247 (2012).

Gower-Rousseau, C. et al. Validation of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index in a population-based cohort. Gut 66 , 588–596 (2017).

Lee, Y. et al. Disability in restorative proctocolectomy recipients measured using the inflammatory bowel disease disability index. J. Crohns Colitis 10 , 1378–1384 (2016).

Lichtenstein, G. R., Cohen, R., Yamashita, B. & Diamond, R. H. Quality of life after proctocolectomy with ileoanal anastomosis for patients with ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 40 , 669–677 (2006).

Peyrin-Biroulet, L., Germain, A., Patel, A. S. & Lindsay, J. O. Systematic review: outcomes and post-operative complications following colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 44 , 807–816 (2016).

Shafer, L. A. et al. Independent validation of a self-report version of the IBD disability index (IBDDI) in a population-based cohort of IBD patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 24 , 766–774 (2018).

Chiricozzi, A. et al. Quality of life of psoriatic patients evaluated by a new psychometric assessment tool: PsoDisk. Eur. J. Dermatol. 25 , 64–69 (2015).

Mercuri, S. R., Gregorio, G. & Brianti, P. Quality of life of psoriasis patients measured by the PSOdisk: a new visual method for assessing the impact of the disease. G. Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 152 , 424–431 (2017).

Ghosh, S. et al. Development of the IBD Disk: a visual self-administered tool for assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 23 , 333–340 (2017).

Levenstein, S. et al. Psychological stress and disease activity in ulcerative colitis: a multidimensional cross-sectional study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 89 , 1219–1225 (1994).

Nahon, S. et al. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 18 , 2086–2091 (2012).

Mikocka-Walus, A. et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety are independently associated with clinical recurrence of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14 , 829–835.e1 (2016).

Bitton, A. et al. Psychosocial determinants of relapse in ulcerative colitis: a longitudinal study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98 , 2203–2208 (2003).

Christensen, B. et al. Histologic normalization occurs in ulcerative colitis and is associated with improved clinical outcomes. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15 , 1557–1564.e1 (2017).

Colombel, J.-F. et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn’s disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 390 , 2779–2789 (2018).

Adedokun, O. J. Association between serum concentration of infliximab and efficacy in adult patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 147 , 1296–1307.e5 (2014).

Kobayashi, T. et al. First trough level of infliximab at week 2 predicts future outcomes of induction therapy in ulcerative colitis-results from a multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial and its post hoc analysis. J. Gastroenterol. 51 , 241–251 (2016).

Papamichael, K. et al. Infliximab concentration thresholds during induction therapy are associated with short-term mucosal healing in patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14 , 543–549 (2016).

Afif, W. et al. Clinical utility of measuring infliximab and human anti-chimeric antibody concentrations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105 , 1133–1139 (2010).

Kobayashi, T. First trough level of infliximab at week 2 predicts future outcomes of induction therapy in ulcerative colitis—results from a multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial and its post hoc analysis. J. Gastroenterol. 51 , 241–251 (2016).

Vande Casteele, N. et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 148 , 1320–1329.e3 (2015).

Roda, G., Jharap, B., Neeraj, N. & Colombel, J.-F. Loss of response to anti-TNFs: definition, epidemiology, and management. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 7 , e135 (2016).

Peyrin-Biroulet, L. et al. Loss of response to vedolizumab and ability of dose intensification to restore response in patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17 , 838–846.e2 (2019).

Baker, K. F. & Isaacs, J. D. Novel therapies for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: what can we learn from their use in rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis? Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77 , 175–187 (2018).

Feagan, B. G. et al. Induction therapy with the selective interleukin-23 inhibitor risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet 389 , 1699–1709 (2017).

Ma, C., Jairath, V., Khanna, R. & Feagan, B. G. Investigational drugs in phase I and phase II clinical trials targeting interleukin 23 (IL23) for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 27 , 649–660 (2018).

Vermeire, S. et al. Etrolizumab as induction therapy for ulcerative colitis: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 384 , 309–318 (2014).

Vermeire, S. et al. Anti-MAdCAM antibody (PF-00547659) for ulcerative colitis (TURANDOT): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 390 , 135–144 (2017).

Yoshimura, N. et al. Safety and efficacy of AJM300, an oral antagonist of α4 integrin, in induction therapy for patients with active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 149 , 1775–1783.e2 (2015).

Langer-Gould, A., Atlas, S. W., Green, A. J., Bollen, A. W. & Pelletier, D. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. N. Engl. J. Med. 353 , 375–381 (2005).

Sandborn, W. J. et al. Ozanimod induction and maintenance treatment for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 374 , 1754–1762 (2016).

Vermeire, S. et al. Clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease treated with filgotinib (the FITZROY study): results from a phase 2, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 389 , 266–275 (2017).

D’Amico, F., Fiorino, G., Furfaro, F., Allocca, M. & Danese, S. Janus kinase inhibitors for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases: developments from phase I and phase II clinical trials. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 27 , 595–599 (2018).

Hansen, J. J. & Sartor, R. B. Therapeutic manipulation of the microbiome in IBD: current results and future approaches. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 13 , 105–120 (2015).

Barber, G. E. et al. Genetic markers predict primary non-response and durable response to anti-TNF biologic therapies in Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 111 , 1816–1822 (2016).

Boyapati, R. K., Kalla, R., Satsangi, J. & Ho, G.-T. Biomarkers in search of precision medicine in IBD. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 111 , 1682–1690 (2016).

West, N. R. et al. Oncostatin M drives intestinal inflammation and predicts response to tumor necrosis factor-neutralizing therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Med. 23 , 579–589 (2017).

Choung, R. S. et al. Serologic microbial associated markers can predict Crohn’s disease behaviour years before disease diagnosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 43 , 1300–1310 (2016).

Doherty, M. K. et al. Fecal microbiota signatures are associated with response to Ustekinumab therapy among Crohn’s disease patients. mBio https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.02120-17 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zhou, Y. et al. Gut microbiota offers universal biomarkers across ethnicity in inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis and infliximab response prediction. mSystems https://doi.org/10.1128/mSystems.00188-17 (2018).

Arijs, I. et al. Predictive value of epithelial gene expression profiles for response to infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 16 , 2090–2098 (2010).

Gamo, K. et al. Gene signature-based approach identified MEK1/2 as a potential target associated with relapse after anti-TNFα treatment for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 24 , 1251–1265 (2018).

Kaplan, G. G. et al. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada 2018: epidemiology. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2 , S6–S16 (2019).

Danese, S. New therapies for inflammatory bowel disease: from the bench to the bedside. Gut 61 , 918–932 (2012).

Download references

Acknowledgements

B.S. acknowledges the DFG (German Research foundation) for funding her research (CRC-TRR 241 and CRC1340).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Advanced IBD Research and Treatment, Kitasato University Kitasato Institute Hospital, Tokyo, Japan

Taku Kobayashi & Toshifumi Hibi

Division of Gastroenterology, Infectiology and Rheumatology, Charite–Universitatsmedizin, Berlin, Germany

Britta Siegmund

Department of Gastroenterology, Nancy University Hospital, Inserm U1256 NGERE, Lorraine University, Lorraine, France

Catherine Le Berre & Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet

Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

Shu Chen Wei

Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Hospitals Leuven, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Marc Ferrante

Center for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Columbia University Irving Medical Center-New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA

University of Manitoba IBD Clinical and Research Centre and Department of Internal Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada

Charles N. Bernstein

Humanitas Clinical and Research Center - IRCCS - and Humanitas University, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Milan, Italy

Silvio Danese

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Introduction (T.H., T.K. and S.D.); Epidemiology (C.N.B.); Mechanisms/pathophysiology (B. Siegmund); Diagnosis, screening and prevention (S.C.W.); Management (M.F. and B. Shen); Quality of life (C.L.B. and L.P.-B.); Outlook (T.K.); Overview of Primer (T.K. L.P.-B and T.H.).

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Taku Kobayashi or Toshifumi Hibi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

T.K. receives research support from AbbVie GK, Alfresa Pharma, EA Pharma, Kyorin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Nippon Kayaku, Otsuka Holdings, Thermo Fisher Scientific and ZERIA; receives advisory fees from AbbVie GK, Activaid, Alfresa Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion, CovidienÐ, Eli Lilly, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Kissei, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Nippon Kayaku, Pfizer, Takeda Pharmaceutical and Thermo Scientific and receives lecture fees from AbbVie GK, Astellas, Alfresa Pharma, Celltrion, EA Pharma, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, JIMRO, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Nippon Kayaku, Takeda Pharmaceutical and ZERIA. B. Siegmund received speaker’s fees from Abbvie, CED Service GmbH, Falk, Ferring, Janssen, Novartis, and Takeda (B. Siegmund served as representative of the Charité) and has served as consultant for AbbVie, Boehringer, Celgene, Falk, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer, Prometheus and Takeda. C.L.B. receives honoraria from AbbVie and Ferring. S.C.W. reports consultancy fees from AbbVie, AbGenomics, Celltrion, Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc., Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and Tanabe and receives lecture fees from AbbVie, Celltrion, Eisai, Excelsior Biopharma Inc., Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc., Janssen, Takeda, Tanabe, Tillotts Pharma, and TSPC (Taiwan Specialty Pharma Corp.). M.F. receives research grants from Amgen, Biogen, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda and receives consultancy fees from AbbVie, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Sandoz, and Takeda and receives speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Falk, Ferring, Janssen, Lamepro, MSD, Mylan, Pfizer, and Takeda. B. Shen receives consultant fees for AbbVie, Takeda and Janssen. C.N.B. has received educational grants from AbbVie Canada, Janssen Canada, Pfizer Canada, Shire Canada, and Takeda Canada and a research grant from AbbVie Canada. C.N.B. has performed contract research for AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Janssen, Pfizer and Roche. He is on the advisory boards for AbbVie Canada, Janssen Canada, Pfizer Canada, Takeda Canada, and Shire Canada and consulted to Mylan Pharmaceuticals. S.D. receives consultancy fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Ely Lilly, Enthera, Ferring Pharmaceuticals Inc., Gilead, Hospira, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, MSD, Mundipharma, Mylan, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Sublimity Therapeutics, Takeda, TiGenix, UCB Inc., and Vifor. L.P.-B. receives research grants from AbbVie, MSD, and Takeda and reports personal fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Alma, Amgen, Applied Molecular Transport, Arena, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Celltrion, Celgene, Enterome, Enthera, Ferring, Fresenius, Genentech, Gilead, Hikma, Index Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Nestle, Norgine, Oppilan Pharma, OSE Immunotherapeutics, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Roche, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Sterna, Sublimity Therapeutics, Takeda, Vifor, and Tillots and stock options from CTMA. T.H. has received research grants from AbbVie, EA Pharma, JIMRO, Otuska Holdings, and Zeria Pharmaceuticals and lecture fees from Aspen Japan KK, AbbVie GK, Ferring, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, JIMRO, Kissei Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Nippon Kayaku Pfizer, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Zeria Pharmaceutical and advisory or consultancy fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion, EA Pharma, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Kyorin, Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma, Nichi-Iko Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Zeria Pharmaceuticals.

Additional information

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Disease Primers thanks O. H. Nielsen, D. Rubin, J. Schölmerich and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

An abnormal narrowing of the digestive tract.

An abnormal connection between two organs or spaces.

A medical sign of facial swelling with deposition of fat.

An abnormal feeling of incomplete defecation.

Dilation of the colon without any mechanical obstruction.

A repetitive invagination of colonic surface epithelium.

A collection of neutrophils in an intestinal crypt.

The presence of plasma cells beneath the base of the crypts.

A transformation of one differentiated cell type to another.

A type of colonic epithelial cell that secrete mucus.

An abnormally fragile surface of the intestine due to inflammation.

A surgically created opening of the small intestine in the abdominal wall.

A space or a cavity in a bone.

The process of formation of a kidney stone.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kobayashi, T., Siegmund, B., Le Berre, C. et al. Ulcerative colitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 6 , 74 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0205-x

Download citation

Accepted : 21 July 2020

Published : 10 September 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0205-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Desulfovibrio vulgaris interacts with novel gut epithelial immune receptor lrrc19 and exacerbates colitis.

- Runxiang Xie

- Hailong Cao

Microbiome (2024)

YAP represses intestinal inflammation through epigenetic silencing of JMJD3

Clinical Epigenetics (2024)

Association between bowel movement frequency and erectile dysfunction in patients with ulcerative colitis: a cross-sectional study

- Shinya Furukawa

- Teruki Miyake

- Yoichi Hiasa

International Journal of Impotence Research (2024)

Endoscopic healing is associated with a reduced risk of biologic treatment failure in patients with ulcerative colitis

- Akira Komatsu

- Takahiko Toyonaga

- Masayuki Saruta

Scientific Reports (2024)

Longitudinal variation of serum PCSK9 in ulcerative colitis: association with disease activity, T helper 1/2/17 cells, and clinical response of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor

- Jialin Deng

- Yongqian Jiang

Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -) (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Ulcerative Colitis With an Unexpected Cause

— can the immune response to covid-19 trigger inflammatory bowel disease.

by Kate Kneisel , Contributing Writer, MedPage Today March 1, 2022

A 50-year-old male patient presented to an outpatient clinic in the spring of 2020 with fever and dyspnea; he told clinicians that the symptoms had persisted for the past 3 days.

Physical examination findings included a fever of 37.8°C (100°F), respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min, and heart rate of 105 beats/min. There was no organomegaly, and the patient was a non-smoker.

Initial laboratory test findings included:

- White blood cell count: 6.4 × 109/L

- C-reactive protein (CRP): 4.6 mg/L

- Ferritin: 162 ng/mL

- D-dimer: 842 ng/mL

Findings of a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2 were negative. However, the patient's wife and two children had positive PCR test results; and the patient's CT chest scan revealed diffuse ground-glass opacities consistent with viral pneumonia. Clinicians diagnosed him with COVID-19, and he was started on a now-debunked 7-day regimen of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. Once he was clinically stable, he was released with instructions to return for a follow-up assessment.

He returned several weeks later with bloody diarrhea, which he explained had come on about 2 weeks after he completed COVID-19 treatment. Stool analysis revealed 10 to 12 erythrocytes and five to six leukocytes. However, there was no evidence of amoebas or Clostridium difficile A+B. Complete blood count and CRP were within normal ranges. Clinicians prescribed treatment with ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and probiotics.

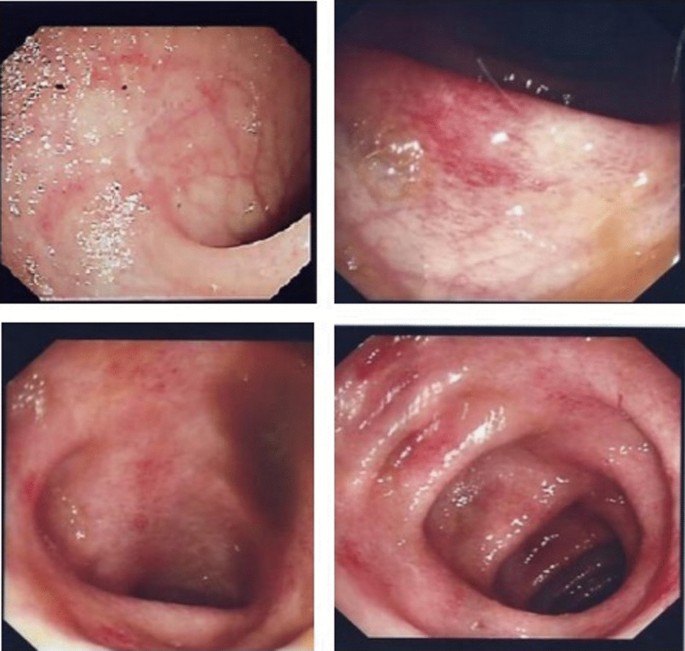

On follow-up assessment 1 week later, the patient reported no improvement in symptoms. His stool calprotectin level was 1800 μg/g (normal range: 0-50 μg/g). Endoscopy revealed a diffuse, micro-ulcerated, granulated appearance that clinicians noted continued uninterrupted from the dentate line to the sigmoid colon, as well as distortion of the submucosal vascularization.

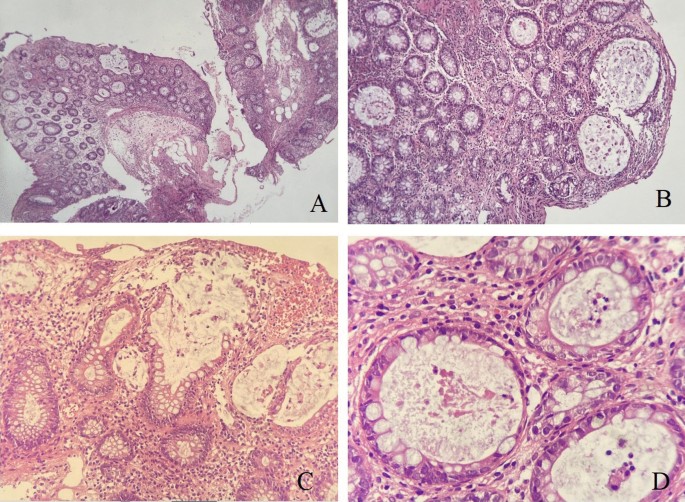

Based on presumed diagnoses of infectious colitis and ulcerative colitis, biopsies were taken. Pathology findings included mucin loss and distortion in the colonic glands, as well as evidence of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNL) and plasma cell infiltration. Clinicians also noted cryptitis and a crypt abscess between the glands; no granulomatous or specific micro-organisms were detected.

The patient was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, which clinicians believed had been triggered by COVID-19. The patient was prescribed treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) therapy, initiated orally and by enema. After 3 days of this drug therapy, his bloody diarrhea and other symptoms resolved.

On testing, the patient's anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were found to be IgG positive and IgM weak positive. A subsequent CT scan revealed significant improvement from the initial findings and evidence of a sequela lesion.

Clinicians presenting this case – which they believe is the second documentation of ulcerative colitis with COVID-19 in the literature – made the report "to show that COVID-19 can appear with other organ pathologies, in addition to upper and lower respiratory tract complaints."

The group noted that initial reports of COVID-19 from China around the time this patient was diagnosed focused only on its respiratory manifestations, so the absence of reports of diarrhea or other gastrointestinal complaints may have "led to under-recognition of these symptoms."

They noted that several studies have since reported the involvement of other organs and diarrhea symptoms. For example, a single-center study of 95 COVID-19 patients admitted to the hospital found GI symptoms in 61% (n=58) of patients overall. Of those symptomatic patients, about 12% were symptomatic on admission, and the remaining 49% developed symptoms (primarily elevated bilirubin and, to a lesser extent, diarrhea) during hospitalization, possibly aggravated by various medications, including antibiotics, researchers reported.

Those researchers found "no statistically significant difference in the general demographics or clinical outcomes between patients with and without GI symptoms." Of the 58 patients with GI manifestations , impaired hepatic function occurred in about 31% during hospitalization, compared with only 1% who were affected on initial presentation.

The next most common symptom, diarrhea (two to 10 loose or watery stools a day) was noted in 24% overall, followed by anorexia and nausea, each affecting 18%. Vomiting affected just 4% of patients.

The researchers noted that antibiotic treatment was associated with development of diarrhea ( P =0.034) and elevated bilirubin levels ( P =0.028) during hospitalization, effects that were not noted with antiviral treatment. Importantly, of the 11 patients with GI symptoms only, 12% had no evidence of COVID-19 pneumonia on imaging, that paper stated.

Authors of the current case report noted that while "COVID-19 RNA can be detected by PCR tests in the stool after respiratory samples become negative in some infected patients," it is not known how long the COVID-19 virus can remain viable in the stool.

They referred to a recent study conducted at China's Wuhan Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Center which suggested that the prompt measures taken to prevent the spread of the virus may explain why none of the 318 registered IBD patients developed COVID-19. While another case series noted diarrhea in just 3% to 5% of patients, authors of the current case report wrote that "clinicians have begun to question the prevalence of IBD as a symptom of COVID-19," citing another report in which 31% of 84 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia had diarrhea.

Case authors pointed to the other report of COVID-19 and ulcerative colitis in which a 19-year-old female from Italy "presented with fever, vomiting, bloody diarrhea, and loss of taste and smell ... a positive PCR test but no CT evidence of pneumonia, and contrast enhancement in the ileum and colon." She recovered fully, returned a negative PCR test, and was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis following an ultrasound of the small bowel on day 16, with no evidence of COVID-19 in stool samples.

Likewise, case authors noted that their patient also tested negative for COVID-19, despite CT evidence of diffuse ground-glass opacities, "the most common manifestation of COVID-19"; he also developed GI symptoms after finishing treatment for COVID-19, which improved on CT.

While noting that their patient's clinical picture was not compatible with ischemic colitis, case authors advised clinicians to also "consider ischemic colitis in the differential diagnosis of antibiotic-induced colitis." Regarding the latter, the group noted that while "late-onset antibiotic-induced colitis can occur on rare occasions," that did not apply in the current case, given his lack of symptoms for 2 weeks after antibiotic treatment, and the absence of amoeba and C. difficile toxins in stool analyses.

In this case, authors noted that their patient's clinical parameters, the presence of bloody diarrhea in the absence of a toxic condition (such as ischemia or necrosis), endoscopic and pathological findings, plus his "very rapid response to 5-ASA treatment for ulcerative colitis, and the onset of complaints after recovery from COVID-19" suggest his ulcerative colitis may have been due to an immune response triggered by COVID-19.

The group explained that the etiology of ulcerative colitis is unknown -- the disease may be induced by inflammation triggered by any condition. That their patient had no history of GI complaints; developed bloody diarrhea and abdominal pain shortly after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms; and had imaging and pathology findings compatible with ulcerative colitis "might suggest that the disease could be triggered by COVID-19," the group noted.

The high levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) and transmembrane serine protease required for the COVID-19 virus to enter cells are expressed by human intestines, they noted, citing emerging data suggesting the virus's effect on the GI system and liver may also be associated with hepatic cells' expression of ACE-2, "a major receptor for gastrointestinal epithelial cells and COVID-19."

Case authors observed that, while little is known about COVID-19 and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), "the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IOIBD) ... recently recommended reducing corticosteroid therapy and maintaining thiopurines and biologics." In 2021, that group also released consensus recommendations regarding SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for IBD patients.

Given the dynamic course seen in COVID-19 and the increasing range of clinical symptoms being reported, "there is an urgent need to properly determine the clinical features of COVID-19," case authors wrote. They acknowledged that while the lack of PCR investigations in stool or tissue samples was a limitation in this case, there was considerable evidence to suggest that the patient did experience COVID-19.

They concluded by urging further study of the association between COVID-19 and IBD, especially ulcerative colitis, and COVID-19 testing in patients presenting with gastrointestinal complaints.

![case study of ulcerative colitis author['full_name']](https://clf1.medpagetoday.com/media/images/author/KKneisel_188.jpg)

Kate Kneisel is a freelance medical journalist based in Belleville, Ontario.

Disclosures

The case report authors noted no conflicts of interest.

Primary Source

Turkish Journal of Gastroenterology

Source Reference: Aydın MF, Taşdemir H "Ulcerative colitis in a COVID-19 patient: A case report" Turk J Gastroenterol 2021; DOI: 10.5152/tjg.2021.20851.

- Current Issue

- Supplements

Gastroenterology & Hepatology

October 2023 - volume 19, issue 10, case report: medical management of acute severe ulcerative colitis.

Sudheer Kumar Vuyyuru, DM Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada Alimentiv, London, Ontario, Canada

Vipul Jairath, MD, PhD Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada Alimentiv, London, Ontario, Canada Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada

Jurij Hanžel, MD, PhD Alimentiv, London, Ontario, Canada Faculty of Medicine, University of Ljubljana and Department of Gastroenterology, University Medical Center Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Christopher Ma, MD, MPH Alimentiv, London, Ontario, Canada Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Departments of Medicine and Community Health Sciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Brian G. Feagan, MD Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada Alimentiv, London, Ontario, Canada Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada

A 29-year-old female patient presented 5 years ago with bloody diarrhea, fecal urgency, and crampy abdominal pain. A colonoscopy was performed, which revealed diffuse loss of vascular pattern and superficial ulcers throughout the colon with a normal terminal ileum. Histopathologic examination of colonic biopsies showed chronic inflammatory changes with cryptitis, crypt abscesses, and architectural distortion of crypts. On this basis, the patient was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC) and began receiving 5-aminosalicylic acid (4.8 g/day). After an initial period of remission, she experienced flare-ups requiring oral corticosteroids, azathioprine (2 mg/kg), and then vedolizumab (Entyvio, Takeda; 300 mg intravenously at weeks 0, 2, and 6, followed by every 8 weeks).

The patient was in clinical remission for 2 years and then presented to the emergency department with an acute exacerbation of UC, with 20 bloody bowel movements per day. On physical examination, there was tachycardia (120 beats per minute), fever (38.3 °C), and mild tenderness in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen. Laboratory findings revealed a markedly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP; 104 mg/L) and fecal calprotectin (3000 µg/g), anemia (hemoglobin 90 g/L), leukocytosis (14,000 cells/mm 3 ), and hypoalbuminemia (28 g/L). She was hospitalized and received intravenous methylprednisolone (60 mg/day) along with other supportive measures, including thromboprophylaxis.

Despite 48 hours of intravenous corticosteroids, the patient continued to have bloody stools (15 per day) and her CRP concentration remained elevated (98 mg/L). Flexible sigmoidoscopy showed deep ulcers and spontaneous mucosal bleeding (modified Mayo endoscopic score of 3), and histopathology indicated features of severe colitis. There was no evidence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) inclusion bodies on immunohistochemistry, and stool culture and toxin testing for Clostridioides difficile were negative. Abdominal radiograph did not demonstrate colonic dilatation.

Infliximab (10 mg/kg) was administered as rescue therapy, and surgical consultation was obtained. Two days after the first dose of infliximab, stool frequency was still 12 times per day with blood and the CRP level was persistently high (98 mg/L). A second infusion of infliximab was administered on day 8 of hospitalization. On day 10, the patient experienced worsening abdominal pain without clinical improvement, and subtotal colectomy with temporary end ileostomy was performed. Following surgery, the patient recovered well and without any postoperative complications, and corticosteroids were rapidly tapered. Subsequently, she underwent surgery for ileal pouch formation and ileostomy closure.

Approximately one-fourth of patients diagnosed with UC will experience an acute exacerbation requiring hospital admission during their lifetime. 1 An episode of acute severe UC (ASUC) can be a life-threatening medical emergency with an overall mortality of 1%. 2 ASUC can lead to serious complications such as toxic megacolon and colonic perforation, and emergency colectomy may be needed in medically refractory cases. 3 Up to 20% of patients admitted with ASUC require a colectomy on their first admission, and this risk increases to 40% after 2 admissions. 1,4

Global hospitalization rates for UC have declined as a result of advanced biologic therapies, optimization of management algorithms, and shifting patterns in UC epidemiology. 5 Although hospitalization rates for UC are decreasing in Western nations, there has been an increase in hospitalizations in newly industrialized countries. 6 This could be attributed to increasing incidence of UC along with limited access to advanced therapies in developing countries. 7 Similarly, in a nationwide registry–based study, a declining trend in emergency colectomy rates was observed from 2000 to 2014 in the United States, while rates of elective ileoanal pouch surgery remained stable. 8 Rates of colectomy in patients with UC from 2007 to 2016 in the United States have decreased as the use of biologic drugs has increased, suggesting a potential association between advanced treatment and the reduction in need for colectomy. 9

Risk Stratification

In 1955, Truelove and Witts conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of cortisone in hospitalized patients with UC in which patients with severe disease experienced worse outcomes than patients with moderate or mild disease. 10 Nearly 70 years later, the criteria that they developed to define severe disease are still commonly used. According to the Truelove and Witts definition, ASUC is characterized by the presence of 6 or more bloody stools per day and at least one of the following signs of systemic toxicity: tachycardia (mean pulse rate >90 beats per minute), fever (>37.8 °C), anemia (hemoglobin <105 g/L), and/or a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (>30 mm/hr). These criteria were later modified to include elevated CRP (>30 mg/L) (Table 1). 11

Initial Management

Patients with ASUC should be admitted urgently and treated according to a standardized management approach to prevent complications. Intravenous corticosteroids remain the gold standard for initial treatment. The pooled response rate following intravenous corticosteroids is reported to be 67% (95% CI, 65-69) with a colectomy rate of 27% (95% CI, 48-76). 12 In patients requiring nutritional support, enteral nutrition is preferred over parenteral nutrition because it is associated with fewer adverse events in ASUC. 13 All patients should receive thromboprophylaxis unless there is a clear contraindication. 14 Importantly, rectal bleeding associated with ASUC is generally not a contraindication to thromboprophylaxis. Stool cultures are essential to rule out C difficile and other bacterial infections. Although C difficile infection in patients with ASUC requires appropriate antibiotic therapy, routine antibiotics are not recommended in all patients. Colonic biopsy with immunohistochemistry should be performed to exclude active CMV infection, especially in patients with a history of corticosteroid dependency. 15 Performing CMV polymerase chain reaction analysis in peripheral blood and tissues is not routinely recommended, as sensitivity and specificity are suboptimal. 16

Predictors of Response to Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 60 mg or hydrocortisone 300-400 mg intravenously) are generally administered for at least 3 to 5 days before proceeding to salvage therapy, as a longer course of corticosteroids is associated with increased morbidity 17 and higher doses are not superior to standard doses. 12,18 Approximately 40% of patients fail to respond to intravenous corticosteroids and are at an increased risk of complications. 3 Therefore, early identification of these patients and instituting appropriate salvage therapy are crucial.

A number of prognostic indices comprised of clinical, endoscopic, and biochemical parameters have been developed to predict corticosteroid therapy failure and subsequent colectomy (Table 2). CRP is one of the commonly monitored biomarkers, and a persistently high CRP on day 3 of corticosteroids has been associated with corticosteroid failure. 19 Criteria developed by Travis and colleagues based on a retrospective case series of 48 patients with ASUC demonstrated that elevated stool frequency (>8 per day) or between 3 and 8 stools per day along with a CRP concentration of greater than 45 mg/L on day 3 of admission predicted an 85% likelihood of colectomy. 20 Ho and colleagues formulated a risk score using stool frequency, colonic dilatation, and serum albumin levels on day 3 as predictive variables in which patients with a score of 4 or greater had a corticosteroid failure rate of 85%. 21 Similarly, the Seo index predicted a colectomy rate of 60% and 83% after 1 and 2 weeks of corticosteroids, respectively, in patients with a score of greater than 200. 22 In the index developed by Lindgren and colleagues, CRP and stool frequency were considered predictive factors of corticosteroid response (CRP mg/L × 0.14 + number of bowel movements). 19 A score of greater than 8 on day 3 of intravenous corticosteroids was associated with colectomy in 72% of patients within 30 days.

Some markers have been shown to be useful in predicting outcomes as early as day 1 of hospitalization. Notably, the number of systemic Truelove and Witts criteria present on admission, in addition to at least 6 bloody stools per day, has been correlated with colectomy (1 criterion: 8.5%; ≥3 criteria: 48%). 1 The Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) has been used to identify high-risk patients at the time of admission. A UCEIS score of 7 or greater was shown to be associated with the need for salvage therapy in 79% (n=11/14) of patients with ASUC. 23 In a subsequent study, 100% of patients with a UCEIS score of greater than 6 on admission day and a fecal calprotectin level greater than 1000 µg/g on day 3 did not respond to corticosteroid therapy. 24 Most recently, a predictive model composed of objective parameters (serum albumin, CRP, and UCEIS score) was developed in a patient cohort from Oxford, United Kingdom, and was externally validated in 2 additional cohorts. A score of 3 or greater on the day of admission had a predictive value of 84% for corticosteroid failure. 25

Medical Salvage Therapy

Patients who fail intravenous corticosteroids require either medical or surgical salvage therapy. Cyclosporine and infliximab have been systematically investigated in clinical trials and are recommended as medical salvage therapy in ASUC. In the open-label CYSIF trial, 115 patients with corticosteroid-refractory ASUC were randomized 1:1 to infliximab (5 mg/kg intravenously on days 0, 14, and 42) and cyclosporine (2 mg/kg intravenously per day for 1 week followed by oral cyclosporine). 26 The primary outcome was treatment failure (absence of clinical response at day 7, relapse between day 7 and day 98, absence of corticosteroid-free remission at day 98, a severe adverse event leading to treatment interruption, colectomy, or death). There was no statistically significant difference between infliximab and cyclosporine in treatment failure, adverse events, and colectomy-free survival at 1 year and 5 years. 27 In the subsequent open-label, pragmatic RCT CONSTRUCT, 270 patients were randomly allocated 1:1 to receive infliximab (5 mg/kg intravenously at weeks 0, 2, and 6) or cyclosporine (2 mg/kg intravenously for 7 days, followed by 5.5 mg/kg orally per day for 12 weeks). 28 No significant differences were found between the 2 drugs with respect to the primary endpoint of quality-adjusted survival, or the secondary endpoints of colectomy rates, time to colectomy, serious adverse events, and death. A meta-analysis of RCTs that investigated infliximab and cyclosporine as salvage therapy in corticosteroid-refractory UC also found no significant differences between infliximab and cyclosporine. 29 Although consensus guidelines do not favor either agent, infliximab is generally preferred at regular or accelerated dosing regimens because of ease of administration and concerns of cyclosporine-related nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity, especially when associated with hypercholesterolemia and hypomagnesemia. Therefore, long-term use of cyclosporine is not recommended, and patients who responded to intravenous cyclosporine should be bridged to an alternative maintenance therapy such as thiopurines. 30 Thus, cyclosporine is not advisable for patients who have previously failed thiopurine therapy. 30 However, recent evidence for the use of biologics as maintenance therapies, including vedolizumab, ustekinumab (Stelara, Janssen), and ozanimod (Zeposia, Bristol Myers Squibb), following cyclosporine rescue therapy has emerged. 31-35 Additionally, there have been reports of sequential rescue therapy after failure of initial salvage therapy, but it is not recommended owing to increased risk of adverse events. 36

Accelerated Dosing of Infliximab

Increased clearance of infliximab in patients with ASUC, especially in those with high inflammatory burden, led to the hypothesis that higher induction doses of infliximab may be needed in this population. However, the data supporting this hypothesis are conflicting.