Housing and the City: case studies of integrated urban design

This case study report assembles a series of housing initiatives from different cities that are developed to promote inclusive, sustainable and integrated designs. The schemes range in scale and geographic location, but in each case represent a clear commitment to achieve positive social and environmental outcomes through innovative yet people and planet-focused design.

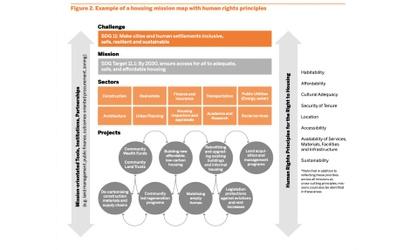

Housing is the backbone of a well-functioning and equitable city. The way in which housing is procured, financed, designed and allocated has significant implications for the lives of all urban residents. However, governments are failing to provide the human right of housing for all. The Council on Urban Initiatives has argued that mission-oriented approaches are needed to galvanise the whole of government engagement, while sectoral investment and cross-disciplinary collaboration are needed to realise the right to housing and prioritise the common good.

Housing has a profound spatial impact on cities. Apartment blocks, condominium towers, detached and terraced houses, self-built shacks and informal slums occupy by far the largest portion of urban land in cities around the world. Decisions about the physical distribution and design of housing will shape the social, economic and environmental dynamics for millions of urban residents for decades to come – particularly in Asia and Africa where urban populations are projected to balloon. Irresponsible development, poor community engagement, and overly permissive regulations and standards have encouraged architectural and urban design practices that foster inequality, exclusion and negative environmental impacts.

The report is divided into three sections: inclusive design, sustainable design and integrated design. Each section highlights examples of housing initiatives with short descriptive texts authored by individual Council members and their teams. From small-scale retrofits in Bogotá’s informal areas to Singapore’s massive state-driven investments, the case studies highlight that governing and designing housing for the common good is critical to the creation of just, green and healthy cities.

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 12 February 2021

Perspectives on urban transformation research: transformations in , of , and by cities

- Katharina Hölscher ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4504-3368 1 &

- Niki Frantzeskaki 2

Urban Transformations volume 3 , Article number: 2 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

63 Citations

53 Altmetric

Metrics details

The narrative of ‘urban transformations’ epitomises the hope that cities provide rich opportunities for contributing to local and global sustainability and resilience. Urban transformation research is developing a rich yet consistent research agenda, offering opportunities for integrating multiple perspectives and disciplines concerned with radical change towards desirable urban systems. We outline three perspectives on urban transformations in , of and by cities as a structuring approach for integrating knowledge about urban transformations. We illustrate how each perspective helps detangle different questions about urban transformations while also raising awareness about their limitations. Each perspective brings distinct insights about urban transformations to ultimately support research and practice on transformations for sustainability and resilience. Future research should endeavour to bridge across the three perspectives to address their respective limitations.

Science highlights

We outline three perspectives on urban transformations for explaining, structuring and integrating the emerging urban transformations research field.

Transformation in cities focuses on unravelling the diverse factors, processes and dynamics driving place-based transformations in cities. This perspective represents research that aims to examine and explain why transformations occur and are supported in some places and not others.

Transformation of cities examines the outcomes of transformative changes in urban (sub-)systems. It serves to understand and evaluate the emergence of new urban functions, new interactions and their implications for sustainability and resilience.

Transformation by cities looks at the changes taking place on global and regional levels as a result of urbanisation and urban development approaches. The perspective emphasises the agency of cities on a global scale and how transformation concepts travel between places.

Future research should aim to bridge across the perspectives to address their respective limitations, for example by bringing in place-based knowledge (‘in’) into global discussions (‘by’) to facilitate cross-city learning.

Policy and practice recommendations

Experimental, collaborative and place-based governance approaches facilitate the integration of local knowledge, the development of inspiring narratives that boost sense of place and empower local communities to boost transformations in cities.

To assess and coordinate urban transformations, transformations, policy and practice actors need to employ systemic concepts and visions that advance solutions with multiple benefits for synergies and minimal trade-offs.

Multi-level partnerships and (transnational) networks for policy knowledge exchange between cities help mobilising the potential of cities as agents of change for sustainability at a global scale.

Introduction

The notion of ‘urban transformation’ has been gaining ground in science and policy debates. Urban transformations to sustainability and resilience are enshrined in the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UN 2016 ) and the New Urban Agenda (UN-Habitat 2016a ). A rich research field around questions of urban transformations has started to emerge, combining multiple scientific disciplines, ontologies and methods (Elmqvist et al. 2018 , 2019 ; Wolfram et al. 2017 ; Vojnovic 2014 ). Key to these debates is the aim to put cities on a central stage for accelerating change towards local and global sustainability and resilience.

Urban transformation narratives have been driven by the recognition of the need and opportunity for radical change towards sustainable and resilient cities. Cities constantly experience changes, but contemporary urban change processes are unparalleled. Cities grapple with a variety of interrelated challenges, including pollution, poverty and inequality, ageing infrastructure and climate change (Haase et al. 2018 ; UN-Habitat 2016b ; Seto et al. 2017 ). Urbanisation in its current form causes significant changes in land use, energy demand, biodiversity and lifestyles and raises questions about the contribution of cities to global environmental change (Haase et al. 2018 ; Alberti et al. 2018 ; Elmqvist et al. 2013 ; Seto et al. 2017 ). At the same time, cities concentrate the conditions and resources for realising the fundamental changes in energy, transportation, water use, land use, housing, consumption and lifestyles that are needed to ensure liveability, wellbeing and sustainability of our (urban) future (Romero-Lankao et al. 2018 ; Koch et al. 2016 ; Elmqvist et al. 2018 ). The potential and momentum in cities is visible in for example the ‘climate emergency’ declarations of local governments that call for accelerated climate action in view of international stalemate.

The notion of urban transformation guides and formulates a better understanding of urban change. On the one hand, ‘transformation’ serves as an analytical lens to describe and understand the continuous, complex and contested processes and dynamics manifesting in cities, as well as how these dynamics alter urban functions, local needs and interactions between cities and their surroundings (McCormick et al. 2013 ; Iwaniec et al. 2019 ). On the other hand, the transformation perspective provides a normative orientation that emphasises the need for radical and systemic change in order to overcome persistent social, environmental and economic problems and to purposefully move towards sustainable and resilient cities in the long-term (Hölscher et al. 2019 ; Kabisch et al. 2018 ). Accordingly, sustainability and resilience are complementary concepts to asses and orient urban transformation processes (Elmqvist et al. 2019 ; Pickett et al. 2014 ; Simon et al. 2018 ).

In this paper, we distinguish three perspectives on urban transformations to structure and guide research and practice on urban transformations. Urban transformation research is an emergent, loosely connected interdisciplinary field combining urban studies and complex system studies. Various research fields and disciplines converge in urban transformation research; the multitude of disciplines has been systematically reviewed in Wolfram et al. ( 2017 ) and Wolfram and Frantzeskaki ( 2016 ). This diversity engenders multiple entry points and provides complementary concepts, theories and insights. However, the diversity causes ambiguities in ontologies, use of concepts and fragmented knowledge about how urban transformations unfold and can be supported.

Urban transformation research would benefit from “gradual interconnection, and the articulation of a certain range of research perspectives” (Wolfram and Frantzeskaki 2016 : 2). To facilitate this, we distinguish and describe three perspectives on urban transformations that provide areas of convergence across diverse research approaches. Each perspective provides distinct starting points to generate, structure and integrate knowledge along certain questions. Ultimately, the perspectives outline an agenda for advancing theory and practice on urban transformations for sustainability and resilience: they generate implications for urban policy and practice and a way forward to bridge across the perspectives to address the respective limitations.

Perspectives on transformations in, of and by cities

We distinguish between perspectives on urban transformations in , of and by cities. The perspectives provide entry points for formulating and structuring research questions on urban transformations, integrating research approaches and knowledge, and deriving implications for practice.

The three perspectives start from similar assumptions about cities and urban transformations. They focus on urban transformations as complex processes of radical, systemic change across multiple dimensions (e.g. social, institutional, cultural, political, economic, technological, ecological) (Hölscher et al. 2018 ; Frantzeskaki et al. 2018a ; McCormick et al. 2013 ). Cities are understood as complex, adaptive and open systems (Alberti et al. 2018 ; McPhearson and Wijsman, 2017 ; Ernstson et al., 2010 ; Collier et al. 2013 ). This implies that urban transformations are not spatially limited, and driven by and driving cross-scale and cross-sectoral dynamics: cities are “local nodes within multiple overlapping social, economic, ecological, political and physical networks, continuously shaping and shaped by flows of people, matter and information across scales” (Wolfram and Frantzeskaki 2016 : 143; see also Hansen and Coenen 2015 ; Chelleri et al. 2015 ). To describe, explain and evaluate urban transformations, cities are increasingly approached as social-ecological-technical systems (SETS), including (1) socio-economic, political and institutional dimensions (social); (2) natural resource flows and physical phenomena (ecological); (3) as well as the manmade surroundings (technological) (McPhearson 2020 ; Alberti et al. 2018 ; Bai et al. 2017 ). Actors have a central position within urban systems, influencing how cities are organised and resources are produced and consumed. Given the open character of urban systems, actors are diverse and include household members, local governments, and entrepreneurs also regional and national governments, international bodies and multinational companies, amongst others (Glaas et al. 2019 ; Webb et al. 2018 ).

Urban transformations can be desirable or undesirable (Elmqvist et al. 2019 ; Hölscher 2019 ). A shared aim across urban transformation research perspectives and approaches is to generate actionable knowledge to intervene in urban transformation processes and support radical change towards sustainable and resilient urban systems (cf. Wittmayer and Hölscher 2017 ).

Despite these shared starting points and aims, the perspectives ask distinct questions about transformations vis-à-vis urban systems. They look at systemic change dynamics taking place in cities (“in”), the outcomes of systemic change of cities (“of”), or systemic change on global and regional levels driven by cities (“by”). These entry points and corresponding questions manifest in differences along key descriptors of urban transformations (cf. Hölscher et al. 2018 ). The differences are not contradictory: they generate complementary insights for understanding and supporting urban transformations given the different level of aggregation, analysis and understanding of system dynamics and points of intervention (Table 1 ).

The main aim of the perspectives is to facilitate structuring of urban transformation research along shared themes and questions. Specifically, in articulating these, we show the actionable knowledge generated through each perspective to support urban transformations for sustainability and resilience. We also show that the perspectives offer bridges across knowledge to strengthen research and practice.

Transformation in cities: cities as places of transformations

Transformation in cities focuses on unravelling the diverse, local, regional and global factors, processes and interactions that converge in cities as places of transformations, thus driving or constraining place-based transformations.

The perspective zooms in on cities as spaces and places. Cities are geolocated in an objective, abstracted point, i.e. space, which is for example demarcated by geographical and administrative boundaries. Cities as places are defined by the physical (i.e. urban form) and philosophical (i.e. imagination and representation) relationships between people and place (Roche, 2016 ; Knox 2005 ). Thus, cities as places are both “a centre of meaning and the external context of people’s actions” (Knox 2005 : 2). As spaces and places of transformations, cities harbour specific potentials, driving forces and barriers (Hansen and Coenen 2015 ).

Place-based transformations are the result of the social construction by people responding to the opportunities and constraints of their particular locality (Fratini and Jensen 2017 ; Späth and Rohracher 2014 ). Endogenous conditions and developments include geographic location, climate, local economic structure, population dynamics and the built environment. For example, urban segregation and inequality result from and are reinforced by interactions between residential choices, personal preferences, job markets, land and real estate markets and public policies (Alberti et al. 2018 ). The construction of place-based transformations does not take place independently of societal norms and representations of the world. Economic and cultural globalisation and the resulting ‘network society’ becomes manifest in cities and shape place-based transformation dynamics (Roche, 2016 ). Scholars seeking to understand the ‘geography in transitions’ emphasise that cities are positioned within cross-scale spatial and institutional contexts that influence local change dynamics (Hansen and Coenen 2015 ; Truffer et al. 2015 ; Coenen et al. 2012 ; Hodson et al. 2017 ; McLean et al. 2016 ). Along similar lines, Loorbach et al. ( 2020 ) show the translocal character of social innovations that are locally rooted but globally connected.

This perspective positions transformative agency as deeply embedded in socio-spatial contexts. A central research focus is on urban niches that experiment with and scale new solutions (McLean et al. 2016 ; Ehnert et al. 2018 ), governance arrangements (Wolfram 2019 ; Hölscher et al. 2019a ) and ways of relating and knowing (Frantzeskaki and Rok 2018 ). Urban experimentation or real-world laboratories have become process tools to facilitate co-creative and innovative solution finding processes that empower actors to deal with urban problems, for example related to mobility, regeneration, community resilience or green job creation (Bulkeley et al. 2019 ; von Wirth et al. 2019 ; Hölscher et al. 2019c ). Such approaches represent situated manners of place-making to co-develop inspiring ‘narratives of place’, empower local communities and foster urban transformative capacities (Wolfram 2019 ; Jensen et al. 2016 ; Ziervogel, 2019 ; Castán Broto et al. 2019 ). The idea of place-specificity recognises the particular role of ‘sense of place’ and ‘place attachment’, which can be an outcome of experimentation and in turn drive transformative change (Frantzeskaki et al., 2016 ; di Masso et al. 2019 ; Brink and Wamsler 2019 ). Ryan ( 2013 ) describes how multiple small ‘eco-acupuncture’ interventions can shift the community’s ideas of what is permissible, desirable and possible.

A key value of this perspective lies on its embedded research inquiry into the ‘black box’ of a city, including social, economic and ecological situated and contextual knowledge. A main implication for urban policy and planning practice is to facilitate place-based innovation by going beyond sectoral infrastructuring and top-down masterplanning towards situated and cross-sectoral place-making. Experimental and co-creative governance approaches help recognise and mobilise place-specific capacities. The need for place-based innovation further calls for higher-level policies to be centred on the local dimension. For example, the current European Union Cohesion Policy puts a place-based approach into practice that recognises place variety (Solly 2016 ) and further extends it to a governance capacity building programme that engages with cities on the ground through the URBACT program ( www.urbact.eu ).

A limitation of this perspective is that knowledge about and actions instigating transformations in a specific city context are very entrenched in context dynamics. This can limit transferability or scaling other than ‘scaling deep’ pathway (Moore et al. 2015 ; Lam et al. 2020 ) if not connected with mechanisms for global and transnational learning and knowledge transfer (Section 2.3). In (Moore et al. 2015 ; Lam et al. 2020 ) addition, neighbourhood-level interventions need to be connected to knowledge about city-level outcomes. This calls for critical evaluations of systemic outcomes in urban systems (Section 2.2).

Transformation of cities: outcomes of transformation dynamics in urban systems

Transformation of cities examines and evaluates the outcomes of transformation dynamics in urban (sub-)systems in terms of new urban functions, local needs and interactions and implications for sustainability and resilience.

This perspective focuses on urban (sub-)systems defined by specific functions (e.g. economy, energy, transport, food, healthcare, housing). Compared to the other perspectives, it most explicitly applies socio-technical and social-ecological, and increasingly SETS, frameworks to describe urban (sub-)systems. Urban transformations are the outcome of radical changes of dominant structures (e.g. infrastructures, regulations), cultures (e.g. values) and practices (e.g. mobility behaviours) of such urban (sub-)systems. As a result of these changes, what kind of and how system functions are delivered is fundamentally altered (Ernst et al. 2016 ).

The main aim of this perspective is to explain and evaluate how transformation dynamics affect urban systems’ functions. Frameworks and models to investigate how transformation dynamics influence urban (sub-)systems pay attention to the complex processes and feedback loops within, across and beyond urban systems and the accumulated effects on the urban system level. For example, studying social-ecological-technical infrastructure systems in cities advances understanding of urban structure-function relationships between green space availability, wellbeing, biodiversity and climate adaptation (McPhearson 2020 ). Similarly, urban metabolism analysis and ecosystem studies seek to understand energy and material flows (Bai 2016 ; Dalla Fontana and Boas 2019 ). An emerging perspective on cities as ‘multi-regime’ configurations investigates dynamics across different functional systems (e.g. energy, water, mobility, food) (Grin et al. 2017 ; Irvine and Bai 2019 ). This provides opportunities to unveil interactions across multiple urban systems and scales. For instance, rapid changes in electricity systems can have knock-on effects for urban mobility or heat systems (Chen and Chen 2016 ; Chelleri et al. 2015 ). The relational geography perspective puts forth a differentiated view of urban systems: it zooms in on different boroughs, districts or neighbourhoods and raises questions such as how innovation and change in one location affects neighbouring locations (Wachsmuth et al. 2016 ).

This perspective most explicitly addresses prescriptive, ‘goal’-driven and recently mission-driven orientations for reinventing cities to be more sustainable, resilient, inclusive, attractive, prosperous, safe and environmentally healthy (Elmqvist et al. 2018 ; Kabisch et al. 2018 ; Rudd et al. 2018 ). Researchers and urban practitioners and planners employ concepts like ‘sustainability’ and ‘resilience’ as frames to evaluate the state of urban systems and to inform urban planning and regeneration programmes (Elmqvist et al. 2019 ). The systemic focus and application of such concepts also helps to identify synergies and trade-offs across urban systems and goals. For example, the sustainability paradigm of maximising efficiency in mobility or energy systems might result in vulnerability to natural disasters when systems lack parallel or redundant back-up systems (ibid.). Similarly, scholars point to the risks of green gentrification: while urban greening interventions have multiple benefits for the environment and climate adaptation, if not planned and governed inclusively, they can create unintended dynamics of exclusion, polarisation and segregation (Anguelovski et al. 2019 ; Haase et al. 2017 ).

This perspective takes a meta-level view on the agency and governance in cities, highlighting strategic partnerships and interventions based on desired system-level outcomes. From this perspective, cities may act as coherent strategic entities based on systemic understandings of city-specific and long-term effects to pursue managed transitions of their large-scale (sub-)systems (Jensen et al. 2016 ; Hodson et al., 2017 ). Urban transformation governance needs to facilitate alignment, foresight and reflexive learning to recognise, anticipate and shape transformation dynamics and leverage points (Hölscher et al. 2019b ). Key starting points are shared definitions of what ‘desirability’ means in specific contexts. Orchestration can align priorities and connect emerging alternatives, ideas, people and solutions (ibid.; Hodson et al., 2017 ). Shared and long-term visions re-orient short-term decisions and interventions that create synergies across multiple priorities. For example, Galvin and Maassen ( 2020 ) analyse Medellín’s (Columbia) mobility transformation that also contributed to inclusiveness and public safety. Transition management is a practice-oriented framework to co-develop shared visions, pathways and experiments in an ongoing learning-by-doing and doing-by-learning way (Frantzeskaki et al. 2018b ; Loorbach et al. 2015 ).

In summary, this perspective provides a view on interpreting transformation dynamics and developing orientations and practical guidance for intervention. It becomes visible in urban planning and policy practice through the development of systemic urban concepts as ‘anchor points’ or attractors for urban transformations such as ‘sharing cities’, ‘circular cities’, or ‘renaturing cities’. Cities like Rotterdam in the Netherlands and New York City in the USA are using such concepts to formulate long-term climate, sustainability and resilience agendas and establish cross-cutting city-level partnerships for their implementation (Hölscher et al. 2019a ). A main implication of this perspective is about the need to institutionalise and prioritise such long-term agendas into policy and planning across sectors and scales (ibid.).

A limitation of this perspective is that it overlooks place-specific implications and can nuance or be agnostic to politics and contestations at local sub-system level. Strategically linking place-based initiatives (Section 2.1) with systemic urban concepts and visions provides a powerful tool to align the multitude of activities taking place in cities and to coordinate urban transformations on (sub-)system scale. Additionally, this perspective requires explicit attention to the relationships between urban systems and their hinterlands or other distant territories, which affect and are affected by urban system’s functioning (Section 2.3).

Transformation by cities: cities as agents of change at global scale

The third perspective on transformation by cities draws attention to the changes taking place on global and regional levels as a result of urbanisation and urban development.

The main emphasis is here placed on cities as “agents of change at global scale” (Acuto 2016 ). As open systems, cities are not just influenced by developments outside their spatial boundaries (see Section 2.1). Urban transformations also have implications on global resources, environmental conditions, commodities and governance.

On the one hand, cities – including their social-ecological-technological configurations and the diversity of actors influencing them – can be viewed as culprits driving global high emissions, resource depletion and unsustainability. This raises critical questions about the relationship between current and unprecedented urbanisation and global sustainability (Seto et al. 2017 ; Haase et al. 2018 ). For example, the expansion of cities will triple land cover by 2030, compared to 2000, with severe implications on biodiversity (Alberti et al. 2018 ; Elmqvist et al. 2013 ). Different frameworks and concepts are employed to describe and assess the linkages between cities and their hinterland and other distant territories, including ‘urban land teleconnections’ (Seto et al. 2012 ), ‘regenerative cities’ (Girardet 2016 ) and ‘urban ecological footprint’ (Folke et al. 1997 ; Hoornweg et al. 2016 ; Rees and Wackernagel 2008 ).

On the other hand, cities have become key loci for trialling sustainable approaches and solutions that inform the global sustainability agenda (UN-Habitat 2016b ; Seto et al. 2017 ; Bai et al. 2018 ). Cities – especially local governments – play key roles in shaping global sustainability programmes and discourses and in developing and sharing knowledge and best practices. Local governments have also become celebrated for taking action when the national government is not (van der Heijden 2018 ; Acuto 2016 ). Governance strategies such as experimentation, best practices or imaginaries have been taken up globally (Haarstad 2016 ; McCann 2011 ; van der Heijden 2016 ). This raises questions about how the experiences and best practices showcased in cities become knowledge to be diffused and shared, as well as how transformations travel between places and across scales (Lam et al. 2020 ).

This perspective supports a polycentric and multi-level approach to global environmental governance. Global environmental governance is becoming increasingly decentralised and polycentric, which is visible for example in climate governance (Ostrom 2014 ; Jordan et al. 2018 ; Hölscher and Frantzeskaki 2020 ) and the urban SDG (UN 2016 ). The recent ‘city charters’ of global organisations such as the IPCC Cities and Climate Change, the Convention on Biological Diversity and Cities and Future Earth Urban Knowledge Network, showcase the recognition of ‘cities’ as key players on a global level. While urban sustainability governance has often proliferated without leadership at national levels, the nestedness of local governance in legal and institutional frameworks at regional, national and international levels requires alignment of priorities and legislation across governance levels (Hughes et al. 2017 ; Keskitalo et al. 2016 ).

In summary, this perspective creates knowledge about the role of cities in contributing to global change and what it means for governance, policy and planning at global, national, metropolitan and regional levels. It provides and requires big data from cities and their resource footprints, flows and dynamics so as to draw on patterns and pathways for change that can inform and reinforce global agendas for action. A key mechanism for urban practitioners is to strengthen policy knowledge exchange across frontrunning cities (Hölscher et al. 2019a ). Transnational city networks such as the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives (ICLEI), C40 and 100 Resilient Cities facilitate knowledge exchange and inter-city learning, foster the creation of collective goals, lobby for international attention, and enable the transplantation of innovative, sustainable and resilient policy and planning approaches (Acuto et al. 2017 ; Lee 2018 ; Mejía-Dugand et al. 2016 ; Frantzeskaki et al. 2019 ; Davidson et al. 2019 ).

A danger of this perspective is that this global discourse is mainly focused on ‘global cities’. Medium-sized and middle-income cities are leaders in terms of actual sustainability performance and need to be actively acknowledged and considered (Vojnovic 2014 ). Florida ( 2017 ) criticises how “winner-take-all cities” reinforce inequality, while many cities stagnate and middle-class neighbourhoods disappear. This requires more research into how resources and opportunities are distributed and made accessible across different cities, for example ‘global’ cities, metropolitan cities and developing countries’ cities (Coenen et al. 2012 ; Gavin et al. 2013 ). Additionally, cities are not necessarily a united front: priorities and interpretations differ across cities (Growe and Freytag 2019 ). To address these issues, this perspective would benefit from a more critical and contextual research approach on place-based transformations (Section 2.1), questioning why transformations occur and are supported in some places and not others. Comparative analyses into the factors and dynamics influencing place-based transformations can facilitate transnational knowledge transfer and upscaling of place-based initiatives.

Conclusions

We offer three perspectives on urban transformations research as a means to cherish and celebrate, but also structure the diversity of the growing urban transformations research field. Our paper is a first attempt to distinguish these perspectives, by discussing key questions, entry points, practical implications and limitations. We show that the perspectives help converge research approaches and clarify how different perspectives provide evidence for urban policy and planning.

The perspectives are not merely conceptual devices: they show up in cities’ agendas, programmes and approaches and give guidance to practitioners. The ‘transformation in cities’ perspective asks practitioners to experiment with collaborative place-making approaches like urban living labs to integrate local knowledge and strengthen a sense of place and empowerment. The ‘transformation of cities’ perspective appears as underlying integrative systems’ approach for core urban strategies such as climate change and biodiversity strategies. The ‘transformation by cities’ perspective highlights the need to invest in policy knowledge exchange between cities, for example through transnational city networks.

The three perspectives on urban transformation do not exist in isolation from one another. We have shown how the perspectives can feed into and complement each other to address respective research gaps and practical challenges. The main future research direction we put forth is to bridge across the perspectives to address their respective limitations and generate comprehensive actionable knowledge. This means to formulate integrative research questions bridging across perspectives: How do place-making initiatives in a specific neighbourhood affect urban systems’ functioning? How can place-based transformation knowledge be transferred to other city contexts? How can place-based experiments and transformation initiatives or projects inform policy at city and city-network level? What are the conditions for downscaling strategic initiatives from global level – for example, post-Aichi biodiversity targets – considering capacities of urban sub-systems?

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

US Department of Housing and Urban Development

International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives

International Panel on Climate Change

Sustainable Development Goal

Social-ecological-technological system

United NationsMeerow, S

Acuto M. Give cities a seat at the top table. Nature. 2016;537:611–3.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acuto M, Morissettte M, Tsouros A. City diplomacy: towards more strategic networking? Learning with WHO health cities. Global Policy. 2017;8(1):14–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12382 .

Article Google Scholar

Alberti M, McPhearson T, Gonzalez A. Embracing urban complexity. In: Elmqvist T, Bai X, Frantzeskaki N, Griffith C, Maddox D, McPhearson T, Parnell S, Romero-Lankao P, Simon D, Watkins M, editors. Urban planet: knowledge towards sustainable cities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018. p. 68–91.

Google Scholar

Anguelovski I, Connolly JJT, Pearsall H, Shokry G, et al. Opinion: why green “climate gentrification” threatens poor and vulnerable populations. PNAS. 2019;116(52):26139–43. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1920490117 .

Bai X. Eight energy and material flow characteristics of urban ecosystems. Ambio. 2016;45(7):819–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0785-6 .

Bai X, Dawson RJ, Ürge-Vorsatz D, Delgado GC, Salisu Barau A, Dhakal S, Dodman D, Leonardsen L, Masson-Delmotte V, Roberts DC, Schultz S. Six research priorities for cities and climate change. Nature. 2018;555:23–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02409-z .

Bai X, McPhearson T, Cleugh H, Nagendra H, Tong X, Zhu T, Zhu Y-G. Linking urbanization and the environment: conceptual and empirical advances. Annual review of environment and resources. 2017;42:215–40. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102016-061128 .

Brink E, Wamsler C. Citizen engagement in climate adaptation surveyed: The role of values, worldviews, gender and place. J Clean Prod. 2019;209:1342–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.164 .

Bulkeley H, Marvin S, Palgan YV, McCormick K, Breitfuss-Loidl M, Mai L, von Wirth T, Frantzeskaki N. Urban living laboratories: conducting the experimental city? Eur Urban Regional Stud. 2019;26(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418787222 .

Castán Broto V, Trencher G, Iwaszuk E, Westman L. Transformative capacity and local action for urban sustainability. Ambio. 2019;48(5):449–62.

Chelleri L, Water JJ, Olazabal M, Minucci G. Resilience trade-offs: addressing multiple scales and temporal aspects of urban resilience. Environmet Urbanization. 2015;27(1):181–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247814550780 .

Chen S, Chen B. Urban energy-water nexus: a network perspective. Appl Energy. 2016;184:905–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.03.042 .

Coenen L, Benneworth P, Truffer B. Toward a spatial perspective on sustainability transitions. Res Policy. 2012;41(6):968–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.014 .

Collier MJ, Nedovic-Budic Z, Aerts J, Connop S, Foley D, Foley K, Newport D, McQuaid S, Slaev A, Verburg P. Transitioning to resilience and sustainability in urban communities. Cities. 2013;32:S21–8.

Dalla Fontana M, Boas I. The politics of the nexus in the city of Amsterdam, Cities; 2019. p. 95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102388 .

Book Google Scholar

Davidson K, Coenen L, Acuto M, Gleeson B. Reconfiguring urban governance in an age of rising city networks: a research agenda, urban studies; 2019. p. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018816010 .

Di Masso A, Williams DR, Raymond CM, et al. Between fixities and flows: navigating place attachments in an increasingly mobile world. J Environ Psychol. 2019;61:125–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.01.006 .

Ehnert F, Frantzeskaki N, Barnes J, Borgström S, Gorissen L, Kern F, Strenchock F, Egermann M. The Acceleration of Urban Sustainability Transitions: a Comparison of Brighton, Budapest, Dresden, Genk, and Stockholm. Sustainability. 2018;10(3):612. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030612 .

Elmqvist T, Andersson E, Frantzeskaki N, McPhearson T, Olsson P, Gaffney O, Takeuchi K, Folke C. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nature Sustainability. 2019;2:267–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0250-1 .

Elmqvist T, Bai X, Frantzeskaki N, Griffith C, Maddox D, McPhearson T, Parnell S, Romero-Lankao P, Simon D, Watkins M, editors. Urban planet: knowledge towards sustainable cities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018.

Elmqvist T, Fragkias M, Goodness J, Gueneralp B, Marcotullio PJ, McDonald RI, Parnell S, Schewenius M, Sendstad M, Seto KC, Wilkinson C. Urbanization, biodiversity and ecosystem services: challenges and opportunities. A global assessment Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7088-1 .

Ernst L, de Graaf-Van Dinther RE, Peek GJ, Loorbach D. Sustainable urban transformation and sustainability transitions; conceptual framework and case study. J Clean Prod. 2016;112:2988–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.136 .

Ernstson H, van der Leeuw SE, Redman CL, et al. Urban transitions: on urban resilience and human-dominated ecosystems. AMBIO. 2010;39:531–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-010-0081-9 .

Florida R. The new urban crisis: how our cities are increasing inequality, deepening segregation, and failing the middle class – and what we can do about it. New York: Basic Books; 2017.

Folke C, Jansson A, Larsson J, Costanza R. Ecosystem appropriation by cities. AMBIO. 1997;26(3):167–72.

Frantzeskaki N, Bach M, Hölscher K, Avelino F. Transition management in and for cities: introducing a new governance approach to address urban challenges. In: Frantzeskaki N, Hölscher K, Bach M, Avelino F, editors. co-creating sustainable urban futures. A primer on applying transition management in cities. Tokyo: Springer; 2018a.

Chapter Google Scholar

Frantzeskaki N, Bach M, Mguni P. Understanding the urban context and its challenges. In: Frantzeskaki N, Hölscher K, Bach M, Avelino F, editors. Co-creating sustainable urban futures. A primer on applying transition management in cities. Tokyo: Springer; 2018b. p. 43–62.

Frantzeskaki N, Buchel S, Spork C, Ludwig K, Kok MTJ. The multiple roles of ICLEI: intermediating to innovate urban biodiversity governance. Ecol Econ. 2019;164:106350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.06.005 .

Frantzeskaki N, Dumitru A, Anguelovski I, Avelino F, Bach M, Best B, Binder C, Barnes J, Carrus J, Egermann M, Haxeltine A, Moore ML, Mira RG, Loorbach D, Uzzell D, Omman I, Olsson P, Silvestri G, Stedman R, Wittmayer J, Durrant R, Rauschmayer F. Elucidating the changing roles of civil society in urban sustainability transitions. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 2016;22:41–50.

Frantzeskaki N, Rok A. Co-producing urban sustainability transitions knowledge with community, policy and science. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 2018;29:47–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2018.08.001 .

Fratini CF, Jensen JS. The Role of Place-specific Dynamics in the Destabilization of the Danish Water Regime: An Actor–Network View on Urban Sustainability Transitions . In: Frantzeskaki N, Castán Broto V, Loorbach D, Coenen L, editors. Urban sustainability transitions: Routledge; 2017.

Galvin M, Maassen A. Connecting formal and informal spaces: a long-term and multi-level view of Medellín’s Metrocable. Urban Transformations. 2020;2(1).

Gavin B, Bouzarovski S, Bradshaw M, Eyre N. Geographies of energy transition: Space, place and the low-carbon economy. Energy Policy. 2013;53:331–40.

Girardet H. Regenerative cities. In: Shmelev S, editor. Green economy reader. Studies in ecological economics, vol 6. Cham: Springer; 2016. p. 183–204.

Glaas E, Hjerpe M, Storbjörk S, Neset TS, Bohman A, Muthumanickam P, Johansson J. Developing transformative capacity through systematic assessments and visualization of urban climate transitions. Ambio. 2019;48:515–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1109-9 .

Grin, J., Frantzeskaki, N., Castàn Broto, V., Coenen, L. (2017) Sustainability transitions and the cities: linking to transition studies and looking forward. In: Frantzeskaki, N., Castán Broto, V., Coenen, L., Loorbach, D. (eds.) Urban sustainability transitions. Routledge Studies in Sustainability Transitions: New York and London, pp. 359–367.

Growe A, Freytag T. Image and implementation of sustainable urban development: showcase projects and other projects in Freiburg, Heidelberg and Tübingen, Germany. Spatial Res Planning. 2019;77(5):457–74. https://doi.org/10.2478/rara-2019-0035 .

Haarstad H. Where are urban energy transitions governed? Conceptualizing the complex governance arrangements for low-carbon mobility in Europe, Cities. 2016;54:4–10.

Haase D, Güneralp B, Dahiya B, Bai X, Elmqvist T. Global Urbanization. In: Elmqvist T, Bai X, Frantzeskaki N, Griffith C, Maddox D, McPhearson T, Parnell S, Romero-Lankao P, Simon D, Watkins M, editors. Urban planet: knowledge towards sustainable cities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018. p. 19–44.

Haase D, Kabisch S, Haase A, Andersson E, Banzhaf E, Baro F, Brenck M, Fischer LK, Frantzeskaki N, Kabisch N, Krellenberg K, Kremer P, Kronenberg J, Larondelle N, Mathey J, Pauleit S, Ring I, Rink D, Schwarz N, Wolf M. Greening cities - to be socially inclusive? About the alleged paradox of society and ecology in cities, Habitat International. 2017;64:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.04.005 .

Hansen T, Coenen L. The geography of sustainability transitions: review, synthesis and reflections on an emergent research field. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 2015;17:92–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2014.11.001 .

Hodson M, Geels F, McMeekin A. Reconfiguring urban sustainability transitions, Analysing multiplicity. Sustainability. 2017;9(2):299–20.

Hölscher K. Transforming urban climate governance. Capacities for transformative climate governance. PhD thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam; 2019.

Hölscher K, Frantzeskaki F, McPhearson T, Loorbach D. Tales of transforming cities: transformative climate governance capacities in New York City, U.S. and Rotterdam, Netherlands. J Environ Manag. 2019a;231:843–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.10.043 .

Hölscher K, Frantzeskaki F, McPhearson T, Loorbach D. Capacities for urban transformations governance and the case of New York City. Cities. 2019b;94:186–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.05.037 .

Hölscher K, Frantzeskaki N. A transformative perspective on climate change and climate governance. In: Hölscher K, Frantzeskaki N, editors. Transformative climate governance. A capacities perspective to systematise, evaluate and guide climate action: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020.

Hölscher K, Wittmayer JM, Avelino F, Giezen M. Opening up the transition arena: an analysis of (dis) empowerment of civil society actors in transition management in cities. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2019c;145:176–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.004 .

Hölscher K, Wittmayer JM, Loorbach D. Transition versus transformation: What’s the difference? Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2017.10.007 .

Hoornweg D, Hosseini M, Kennedy C, Behdadi A. An urban approach to planetary boundaries. Ambio. 2016;45:567–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0764-y .

Hughes S, Chu EK, Mason SG, editors. Climate change in cities. Innovations in Multi-level Governance: Springer; 2017.

Irvine S, Bai X. Positive inertia and proactive influencing towards sustainability: systems analysis of a frontrunner city. Urban Transform. 2019;1:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-019-0001-7 .

Iwaniec DM, Cook EM, Barbosa O, Grimm NB. The framing of urban sustainability transformations. Sustainability. 2019;11:573. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030573 .

Jensen JS, Fratini CF, Cashmore MA. Socio-technical systems as place-specific matters of concern: the role of urban governance in the transition of the wastewater system in Denmark. J Environmental Policy Planning. 2016;18(2):234–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1074062 .

Jordan A, Huitema D, van Asselt H, Forster J. Governing climate change: the promise and limits of polycentric governance. In: Jordan A, Huitema D, van Asselt H, Forster J, editors. Governing climate change. Polycentricity in action? Cambridge: Cambridge University press; 2018. p. 359–83.

Kabisch S, Koch F, Gawel E, Haase A, Knapp S, Krellenberg K, Zehnsdorf A. Introduction: Urban transformations – sustainable urban development through resource efficiency, quality of life, and resilience. In: Kabisch S, Koch F, Gawel E, Haase A, Knapp S, Krellenberg K, Nivala J, Zehnsdorf A, editors. Urban transformations - Sustainable urban development through resource efficiency, quality of life and resilience. Future City 10: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. xvii–xxviii.

Keskitalo ECH, Juhola S, Baron N, Fyhn H, Klein J. Implementing local climate change adaptation and mitigation actions: the role of Varios policy instruments in a multi-level governance context. Climate. 2016;4(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli4010007 .

Knox PL. Creating ordinary places: slow cities in a fast world. J Urban Des. 2005;10(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800500062221 .

Koch F, Krellenberg K, Kabisch S. (2016) How to achieve urban sustainability transformations (UST) in real life politics? Brief for GSDR – 2016 Update. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/961514_Koch%20et%20al._How%20to%20achieve%20Urban%20Sustainability%20Transformations%20(UST)%20in%20real%20life%20politics.pdf . Accessed: 4 Oct 2018.

Lam DPM, Martín-López B, Wiek A, et al. Scaling the impact of sustainability initiatives: a typology of amplification processes. Urban Transform. 2020;2:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-020-00007-9 .

Lee T. Network comparison of socialization, learning and collaboration in the C40 cities climate group. J Environmental Policy Planning. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2018.1433998 .

Loorbach D, Frantzeskaki N, Huffenreuter LR. Transition management: taking stock from governance experimentation. J Corp Citizsh. 2015;58:48–66.

Loorbach D, Wittmayer JM, Avelino F, von Wirth T, Frantzeskaki N. Transformative innovation and translocal diffusion. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.01.009 .

McCann E. Urban policy mobilities and global circuits of knowledge: towards a research agenda. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2011;101(1):107–30.

McCormick K, Anderberg S, Coenen L, Neij L. Advancing sustainable urban transformation. J Clean Prod. 2013;50:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.01.003 .

McLean A, Bulkeley H, Crang M. Negotiating the urban smart grid: socio-technical experimentation in the city of Austin. Urban Stud. 2016;53(15):3246–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015612984 .

McPhearson T. Transforming cities and science for climate change resilience in the Anthropocene. In: Hölscher K, Frantzeskaki N, editors. Transformative climate governance. A capacities perspective to systematise, evaluate and guide climate action: Palgrave Macmillan; 2020.

McPhearson T, Wijsman K. Transitioning complex Urban Systems. The importance of urban ecology for sustainability in New York City. In: Frantzeskaki N, Castán Broto V, Coenen L, Loorbach D, editors. Urban sustainability transitions. Springer; 2017.

Mejía-Dugand S, Kanda W, Hjelm O. Analyzing international city networks for sustainability: a study of five major swedish cities. Journal of cleaner production, 134(part a): 61-69. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.093 .

Moore ML, Riddell D, Vocisano D. Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep: strategies of non-profits in advancing systemic social innovation. J Corporate Citizenship. 2015;58:67–85.

Ostrom E. A polycentric approach for coping with climate change. Ann Econ Financ. 2014;15:71–108. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5095 .

Pickett STA, McGrath B, Cadenasso ML, Felson AJ. Ecological resilience and resilient cities. Building ResInformation. 2014;42(2):143–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2014.850600 .

Rees W, Wackernagel M. Urban ecological footprints: why cities cannot be sustainable – and why they are key to sustainability. In: Marzluff JM, et al., editors. Urban ecology. Boston, MA: Springer; 2008. p. 537–55.

Roche S. Geographic information science II: less space, more places in smart cities. Prog Hum Geogr. 2016;40(4):565–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515586296 .

Romero-Lankao P, Bulkeley H, Pelling M, Burch S, Gordon D, Gupta J, Johnson C, Kurian P, Simon D, Tozer L, Ziervogel G, Munshi D. Realizing urban transformative potential in a changing climate. Nat Clim Chang. 2018a. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0264-0 .

Rudd A, Simon D, Cardama M, Birch EL, Revi A. The UN, the urban sustainable development goal, and the new urban agenda. In: Elmqvist T, Bai X, Frantzeskaki N, Griffith C, Maddox D, McPhearson T, Parnell S, Romero-Lankao P, Simon D, Watkins M, editors. Urban planet: knowledge towards sustainable cities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018. p. 180–96.

Ryan C. Eco-acupuncture: designing and facilitating pathways for urban transformation, for a resilient low-carbon future. J Clean Prod. 2013;50:189–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.029 .

Seto KC, Golden JS, Alberti M, Turner BL II. Sustainability in an urbanizing planet. PNAS. 2017;114(34):8935–8.

Seto KS, Reenberg A, Boone CC, Fragkias M, Haase D, Langanke T, Marcotullio P, Munroe DK, Olah B, Simon D. Teleconnections and sustainability: new conceptualizations of global urbanization and land change. PNAS. 2012;109(20):7687–92. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117622109 .

Simon D, Griffith C, Nagendra H. Rethinking urban sustainability and resilience. In: Elmqvist T, Bai X, Frantzeskaki N, Griffith C, Maddox D, McPhearson T, Parnell S, Romero-Lankao P, Simon D, Watkins M, editors. Urban planet: knowledge towards sustainable cities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018. p. 149–62.

Solly A. Place-based innovation in cohesion policy: meeting and measuring the challenges. Reg Stud Reg Sci. 2016;3(1):193–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2016.1150199 .

Späth P, Rohracher H. The interplay of urban energy policy and socio-technical transitions: the eco-cities of Graz and Freiburg in retrospect. Urban Stud. 2014;51(7):1415–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013500360 .

Truffer B, Murphy JT, Raven R. The geography of sustainability transitions: contours of an emerging theme. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 2015;17:63–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.07.004 .

UN (2016) Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. A/Res/70/1. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf . Accessed: 4 Oct 2018.

UN-Habitat (2016a) New Urban Agenda. http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf

UN-Habitat. Urbanization and Development. Emerging Futures. World Cities Report 2016. Nairobi: UN-Habitat; 2016b.

Van der Heijden J. Experimental governance for low-carbon buildings and cities: value and limits of local action networks. Cities. 2016;53:1–7.

Van der Heijden J. City and subnational governance: high ambitions, innovative instruments and polycentric collaborations? In: Jordan A, Huitema D, van Asselt H, Forster J, editors. governing climate change. Polycentricity in action? Cambridge: Cambridge University press; 2018. p. 81–96.

Vojnovic I. Urban sustainability: research, politics, policy and practice. Cities. 2014;41:30–44.

Von Wirth T, Fuenfschilling L, Frantzeskaki N, Coenen L. Impacts of urban living labs on sustainability transitions: mechanisms and strategies for systemic change through experimentation. Eur Plan Stud. 2019;27(2):229–57.

Wachsmuth D, Cohen DA, Angelo H. Expand the frontiers of urban sustainability. Nature. 2016;536:391–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/536391a .

Webb R, Bai X, Smith MS, Costanza R, Griggs D, Moglia M, Neuman M, Newman P, Newton P, Norman B, Ryan C, Schandl H, Steffen W, Tapper N, Thomson G. sustainable urban systems: co-design and framing for transformation. Ambio. 2018;47:57–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-017-0934-6 .

Wittmayer J, Hölscher K. Transformationsforschung – Definitionen, Ansätze, Methoden. Bericht des AP1. Dessau-Roßlau: Umweltbundesamt; 2017. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1410/publikationen/2017-11-08_texte_103-2017_transformationsforschung.pdf

Wolfram M. Assessing transformative capacity for sustainable urban regeneration: a comparative study of three south Korean cities. Ambio. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1111-2 .

Wolfram M, Frantzeskaki N. Cities and systemic change for sustainability: prevailing epistemologies and an emerging research agenda. Sustainability. 2016;8:144. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8020144 .

Wolfram M, Frantzeskaki N, Maschmeyer S. Cities, systems and sustainability: status and perspectives of research on urban transformations. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 2017;22:18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.014 .

Ziervogel G. Building transformative capacity for adaptation planning and implementation that works for the urban poor: insights from South Africa. Ambio. 2019;48:494–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1141-9 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The research leading to this article has received funding from the European Community’s Framework Program Horizon 2020 for the Connecting Nature Project (grant agreement no. 730222; www.connectingnature.eu ) and the European Community’s Framework Program FP7 for the IMPRESSIONS project [grant number 603416, www.impressions-project.eu ].

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dutch Research Institute for Transitions (DRIFT), Mandeville building (16th floor), Erasmus University Rotterdam, Burgemeester Oudlaan 50, 3062, PA, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Katharina Hölscher

Centre for Urban Transitions, Level 1 EW Building, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC, 3122, Australia

Niki Frantzeskaki

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KH conceived of the conceptual structuring approach. Both authors contributed equally to the literature review and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Katharina Hölscher .

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hölscher, K., Frantzeskaki, N. Perspectives on urban transformation research: transformations in , of , and by cities. Urban Transform 3 , 2 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-021-00019-z

Download citation

Received : 24 October 2019

Accepted : 20 January 2021

Published : 12 February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42854-021-00019-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Urban transformations

- Sustainability transitions

- Transformation research

Urban Transformations

ISSN: 2524-8162

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

The Urban Design Case Study Archive is a project of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design developed collaboratively between faculty, students, developers, and professional library staff. Specifically, it is an ongoing collaboration between the GSD’s Department of Urban Planning and Design and the Frances Loeb Library. This project received funding from the Veronica Rudge Green Prize for its development and was originally envisioned by professors Peter Rowe and Rahul Mehrotra.

As a collection of case studies, the project aims to support the study of the built environment in urban areas through a rich data model for urban design projects and their related descriptions, interpretations, drawings, and images. It makes use of excellent data entry tools that support the sophisticated search and visualization needed to support its pedagogical aims and scholarly research. Each case study includes digital photographs of the urban context, the projects themselves, and other graphic representation such as site plans, sections, and elevations, as well as texts, commentary, articles, analyses, bibliographies, people involved and interviews to facilitate and encourage discoverability and a flexible navigation within and across case studies depending on research interests.

The project launched in 2023 with urban design projects awarded the Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design and will continue to cover urban design projects of excellence across the globe. We thank the funders, faculty, staff, students, and the developers Performant Solutions, LLC for bringing this project to fruition.

Veronica Rudge Green Prize in Urban Design

Rahul Mehrotra, John T. Dunlop Professor in Housing and Urbanization

Peter Rowe, Raymond Garbe Professor of Architecture and Urban Design and Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor

Ann Whiteside, Librarian/Assistant Dean for Information Services

Bruce Boucek, GIS, Data, and Research Librarian

Alix Reiskind, Research and Teaching Support Team Lead Librarian

Ines Zalduendo, Special Collections Curator

Research Staff

Boya Guo, DDes ‘22

Liene Asahi Baptista, MAUD ‘23

Yona Chung, DDes ‘25

Priyanka Kar, MAUD ‘24

Sarahdjane Mortimer, MAUD ‘23

Enrique Mutis, MAUD ‘24

Developer/Development Team

Performant Software

Jamie Folsom

Chelsea Giordan

Derek Leadbetter

Ben Silverman

With special thanks to all the image contributors who have generously granted us copyright permission to include their images in the Urban Design Case Study Archive.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

UrbanDevelopment →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

Publications

Uniquely urban: case studies in innovative urban development.

07:14 am | 03 November 2023

Cities in the Asia and the Pacific face challenges to provide adequate infrastructure and services to their growing population. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has long recognized that cities need large scale investment to develop and maintain infrastructure and services.

This report presents case studies that highlight how ADB's teams are working together to design innovative urban projects across the Asia and Pacific region that leverage its value-added services and support sustainable economic growth. The report is based on interviews with teams in countries including the People's Republic of China, India, Viet Nam, and Uzbekistan.

- Introduction

- How Upstream Programmatic Interventions Drive Industrial and Urban Transformation

- How People-Friendly Urban Mobility and Green Sponge Infrastructure Is Transforming a City

- A First in Viet Nam Water Sector: Utility Transitions to Nonsovereign Lending

- Nonsovereign PRC Loan Demonstrates Broad Integration of Smart Water Technologies

- Beyond Slum Upgrades: How Affordable Housing Projects Build Resilient, Thriving Households

- ADB’s First Blue Loan Intercepts Plastics from Landfills, Oceans through Recycling, and Reuse of Ubiquitous PET

- Private Sector Team in Georgia Expands Green Bond Market in Asia, Urban Water Sector

- Integrating Urban Design, Nature, and Heritage for Tourism in a Cold-Climate Country: Preliminary ADB Lessons from Mongolia

- The Making of a Market-Based Mortgage Sector

Published February 2023. Source: Asian Development Bank

Download (7.72 MB)

Smart Tourism Ecosystem Development Readiness in Southeast Asia

Experts talk solutions: budi gunadi sadikin, asean taxonomy defines sustainable activities in transport, construction sectors, asia-pacific trade facilitation report 2024: promoting sustainability and resilience of global value chains, reuse of electric vehicle batteries in asean, related articles, how cities can embrace nature and meet their net-zero goals, why cities need better connectivity, asian cities to build climate-resilient infrastructure with adb support, how artificial intelligence can help build smart cities, how the cloud helps cities become sustainable and inclusive.

Want to Learn More?

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Email Address Submit

Content Search

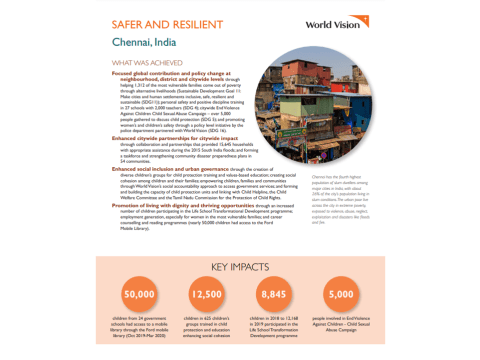

Urban case study: safer and resilient - chennai, india.

- World Vision

Attachments

WHAT WAS ACHIEVED

Focused global contribution and policy change at neighbourhood, district and citywide levels through helping 1,312 of the most vulnerable families come out of poverty through alternative livelihoods (Sustainable Development Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable (SDG11)); personal safety and positive discipline training in 27 schools with 2,000 teachers (SDG 4); citywide End Violence Against Children Child Sexual Abuse Campaign – over 5,000 people gathered to discuss child protection (SDG 5); and promoting women’s and children’s safety through a policy level initiative by the police department partnered with World Vision (SDG 16).

Enhanced citywide partnerships for citywide impact through collaboration and partnerships that provided 15,645 households with appropriate assistance during the 2015 South India floods; and forming a taskforce and strengthening community disaster preparedness plans in 54 communities.

Enhanced social inclusion and urban governance through the creation of diverse children’s groups for child protection training and values-based education; creating social cohesion among children and their families; empowering children, families and communities through World Vision’s social accountability approach to access government services; and forming and building the capacity of child protection units and linking with Child Helpline, the Child Welfare Committee and the Tamil Nadu Commission for the Protection of Child Rights.

Promotion of living with dignity and thriving opportunities through an increased number of children participating in the Life School Transformational Development programme; employment generation, especially for women in the most vulnerable families; and career counselling and reading programmes (nearly 50,000 children had access to the Ford Mobile Library).

Related Content

India: flood 2023 dref operation no. mdrin028 final report, addressing child marriage through comprehensive gender-transformative program: evidence from umang, india: salesian missions funds project to help support migrant children, india annual country report 2023 - country strategic plan 2023 - 2027.

- Facebook Profile

- YouTube Channel

- Linkedin Profile

Investing in Equitable Urban Park Systems: Case Studies & Recommendations

City Parks Alliance is leading a national initiative to research, curate, and disseminate innovative strategies and models for funding parks and green infrastructure in low-income communities.

The seven case studies included in this document showcase cities that are leading the way in using data-driven approaches to ensure more equitable distribution of funding.

As a foundation to this work on funding and equity, City Parks Alliance commissioned Urban Institute to lead research about funding models and their equity considerations in U.S. cities of various sizes. The resulting report, Investing in Equitable Urban Park Systems: Emerging Strategies and Tools , was published in July 2019. It explores twenty funding models and their equity considerations in cities of various sizes across the country. Beyond new sources of funding, the research turned up a number of strategies that utilize an equity lens to shape funding decisions. City Parks Alliance has also partnered with Groundwork USA to identify a framework to help communities use these strategies successfully, to be released in 2020.

This work is made possible with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Equitable Funding Case Studies

City of detroit parks and recreation, detroit: parks & rec improvement plan.

Learn about Detroit’s equity-focused park planning team, which used equity data to create an improvement plan for 40 neighborhood parks.

Pittsburgh Park Conservancy, Pittsburgh Parks and Recreation

Pittsburgh: parks for all.

An equitable investment plan was driven by data and coupled with residents’ input and priorities, resulting in the passage of a park tax referendum.

New York City: Framework for an Equitable Future

NYC Parks analyzed capital investment data from the past 20 years and established long-term community partnerships that sustain investment in the city’s parks.

San Francisco Recreation & Parks, San Francisco Parks Alliance

San francisco: cal enviro screen 3.0.

The approval of a park revenue measure drove the development of an equity analysis, which leveraged a statewide open data set provided by the EPA.

Philadelphia Parks & Recreation

Philadelphia: rebuilding community infrastructure.

Rebuild, funded by a sugary beverage tax, aims to revitalize neighborhood parks, recreation centers, playgrounds, and libraries.

Minneapolis Parks & Recreation

Minneapolis: community outreach department and 20-year neighborhood park plan.

Minneapolis’ Community Outreach Department uses data-driven racial and economic equity criteria to close park funding gaps and distribute funds.

Los Angeles County Regional Park and Open Space District (RPOSD)

La county: park needs assessment.

Learn how a park needs assessment and an engaged community led to the passage of a new tax-based parks measure that provides funds to high-need.

RELATED RESOURCES

Denver Parks and Recreation Letter of Partnership

This informal letter outlines roles, responsibilities, and expectations for partnership between the department and Sloan's Lake Park Foundation.

Milwaukee Parks Foundation Grant Application Guidelines

Milwaukee Parks Foundation offers grants to grassroots groups seeking to improve parks. Application guidelines and evaluation criteria are outlined.

Milwaukee Parks Foundation Project Tracker Template

This project tracker is used by Milwaukee Parks Foundation and Milwaukee County Parks to track progress, funding, and tasks for joint projects.

Urban case study: Safer and Resilient - Chennai, India

- Link for sharing

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

Download this two-page case study to learn more about World Vision’s work in the city of Chennai, India.

Discover more urban case studies from around the world:

- Case study: Urban Innovation - Dhaka, Bangladesh

- Case study: Safer and Healthier - Phnom Penh, Cambodia

- Case study: Safer, Resilient and Prosperous - Valle de Sula, Honduras

- Case study: Safer and Resilient - Beirut, Lebanon

- Case study: Safer and more Prosperous - Baseco, Philippines

Related Resources

Urban case study: Safer, Resilient and Prosperous - Valle de Sula, Honduras

Case study: Urban innovation - Dhaka, Bangladesh

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 May 2021

Intra-urban microclimate investigation in urban heat island through a novel mobile monitoring system

- Ioannis Kousis 1 , 2 ,

- Ilaria Pigliautile 1 , 2 &

- Anna Laura Pisello 1 , 2

Scientific Reports volume 11 , Article number: 9732 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

6456 Accesses

39 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Energy infrastructure

- Energy science and technology

- Engineering

- Environmental sciences

- Environmental social sciences

Monitoring microclimate variables within cities with high accuracy is an ongoing challenge for a better urban resilience to climate change. Assessing the intra-urban characteristics of a city is of vital importance for ensuring fine living standards for citizens. Here, a novel mobile microclimate station is applied for monitoring the main microclimatic variables regulating urban and intra-urban environment, as well as directionally monitoring shortwave radiation and illuminance and hence systematically map for the first time the effect of urban surfaces and anthropogenic heat. We performed day-time and night-time monitoring campaigns within a historical city in Italy, characterized by substantial urban structure differentiations. We found significant intra-urban variations concerning variables such as air temperature and shortwave radiation. Moreover, the proposed experimental framework may capture, for the very first time, significant directional variations with respect to shortwave radiation and illuminance across the city at microclimate scale. The presented mobile station represents therefore the key missing piece for exhaustively identifying urban environmental quality, anthropogenic actions, and data driven modelling toward risk and resilience planning. It can be therefore used in combination with satellite data, stable weather station or other mobile stations, e.g. wearable sensing techniques, through a citizens’ science approach in smart, livable, and sustainable cities in the near future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Hyperlocal environmental data with a mobile platform in urban environments

A mobile car monitoring system as a supplementary tool for air quality monitoring in urban and rural environments: the case study from Poland

Development of a holistic urban heat island evaluation methodology

Introduction.

Within recent decades the rural-to-urban population flow has substantially increased. In 2016, 54% of the world population was reported to live in urbanised areas. At the same time, future projections of urbanization rates are rather alarming. It is expected that by 2050 and 2100 the corresponding fraction will increase up to 66% and 85% respectively 1 . Urbanization is typically followed by high population and building density and consequent land-use and surface alterations, e.g. deforestation, loss of farmland 2 , 3 . Natural-to-urban land alterations affect in turn the local energy balance of cities and thus their microclimatic characteristics and thermal environment in particular 4 , 5 . As a result, cities tend to systematically experience higher surface and air temperatures as compared to the surrounding rural areas, a phenomenon reported as Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 . The driving physics behind UHI is the reduction in latent heat flux and increase in sensible heat flux 10 , 11 . UHI is a significant human-induced environmental change that poses threats to human life. For instance, increased morbidity and mortality 12 , indoor/outdoor discomfort 13 , air pollution 14 , 15 , increased energy consumption 16 and greenhouse gas emissions 17 , 18 , impaired air and water quality 19 and intensification of energy poverty on vulnerable social groups during the hot months of the year 20 , 21 are just some of UHI consequences that usually are interconnected. Also, UHI is associated with global warming and moreover has been found to synergistically act with heatwaves and amplify their impacts 22 , 23 , 24 . Considering the projections linked to the ongoing climate change, the livability of cities will be seriously endangered 25 . In fact, according to IPCC’s Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5, global warming is expected to reach up to 1.5° above pre-industrial levels by 2050, and up to 2.0°–4.9° by 2100 as compared to 1861–1880 26 , 27 . Thus, heat-related risk within urban canopy layers is likely to increase even more in the very near future, making the urban population particularly vulnerable during periods of hot weather.

Measures for counterbalancing UHI and its aftermaths are deemed of critical importance. In fact, techniques for controlling the variables regulating the urban microclimate are receiving increased attention from academics, urban planners and policy-makers 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 . Quantifying, however, the magnitude of each microclimatic parameter is not trivial, especially because affected by dynamic and granular anthropogenic forcing. Instead, due to the complex morphology of urban areas, microclimatic conditions have been found to significantly vary not only among different cities but also among different locations of the very same city 33 . For instance, UHI incidences has been found not only between urban and rural areas but also between urban and suburban areas 34 , 35 . In general, the profile of each investigated urban microclimate is determined by the unique characteristics of the corresponding area 36 . Therefore, the intrinsic inhomogeneity of urban microclimate needs to be in-depth investigated with respect to the spatio-temporal variations originated from the local morphology, anthropogenic actions, urban planning, and temporal weather conditions 37 , 38 , 39 . For precisely determining the gradient and the intra-urban deviations of microclimatic variables, their spatial extent needs to be thoroughly delineated. Mapping out each variable’s footprint can result in a better understanding and evaluation of cities’ function, as well as decreased biases concerning local phenomena, such as UHI magnitude and its consequent heat stress and risk mapping. Furthermore, more efficient comparison analysis among relevant studies will be feasible 40 .

Traditionally, in-situ meteorological stations have been implemented for measuring parameters such as air temperature and humidity, in and out of the city. For instance, Santamouris et al. 41 utilised and retrieved data from a network of 23 experimental weather station within the city of Athens and gauged the corresponding UHI magnitude while the same did Yang et al. 16 in the city of Nanjing, China and Foisard et al. 42 within the city of Rennes, France by implementing networks of 15 and 22 weather stations, respectively. Similarly, Richard et al. 43 employed an extended network of 47 fixed air temperature sensors for identifying thermal zones within the city of Dijon, France during a 3-week heatwave. Another sensor network of high density is established by the Birmingham Urban Climate Laboratory and comprises 29 sensors distributed within the entire city of Birmingham 44 . Results of such studies are of critical importance since not only gauge the magnitude of local phenomena, such as UHI, but also shed light on the corresponding mechanisms of urban climate and hence help towards efficient countermeasures. However, since in most cases meteorological stations are sparsely distributed, data retrieved from this method represent a point-wise momentum of each microclimatic variable and not the overall footprint and the corresponding spatial patterns 16 .