- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Results Section – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Results

Research results refer to the findings and conclusions derived from a systematic investigation or study conducted to answer a specific question or hypothesis. These results are typically presented in a written report or paper and can include various forms of data such as numerical data, qualitative data, statistics, charts, graphs, and visual aids.

Results Section in Research

The results section of the research paper presents the findings of the study. It is the part of the paper where the researcher reports the data collected during the study and analyzes it to draw conclusions.

In the results section, the researcher should describe the data that was collected, the statistical analysis performed, and the findings of the study. It is important to be objective and not interpret the data in this section. Instead, the researcher should report the data as accurately and objectively as possible.

Structure of Research Results Section

The structure of the research results section can vary depending on the type of research conducted, but in general, it should contain the following components:

- Introduction: The introduction should provide an overview of the study, its aims, and its research questions. It should also briefly explain the methodology used to conduct the study.

- Data presentation : This section presents the data collected during the study. It may include tables, graphs, or other visual aids to help readers better understand the data. The data presented should be organized in a logical and coherent way, with headings and subheadings used to help guide the reader.

- Data analysis: In this section, the data presented in the previous section are analyzed and interpreted. The statistical tests used to analyze the data should be clearly explained, and the results of the tests should be presented in a way that is easy to understand.

- Discussion of results : This section should provide an interpretation of the results of the study, including a discussion of any unexpected findings. The discussion should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Limitations: This section should acknowledge any limitations of the study, such as sample size, data collection methods, or other factors that may have influenced the results.

- Conclusions: The conclusions should summarize the main findings of the study and provide a final interpretation of the results. The conclusions should also address the study’s research questions and explain how the results contribute to the field of study.

- Recommendations : This section may provide recommendations for future research based on the study’s findings. It may also suggest practical applications for the study’s results in real-world settings.

Outline of Research Results Section

The following is an outline of the key components typically included in the Results section:

I. Introduction

- A brief overview of the research objectives and hypotheses

- A statement of the research question

II. Descriptive statistics

- Summary statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation) for each variable analyzed

- Frequencies and percentages for categorical variables

III. Inferential statistics

- Results of statistical analyses, including tests of hypotheses

- Tables or figures to display statistical results

IV. Effect sizes and confidence intervals

- Effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d, odds ratio) to quantify the strength of the relationship between variables

- Confidence intervals to estimate the range of plausible values for the effect size

V. Subgroup analyses

- Results of analyses that examined differences between subgroups (e.g., by gender, age, treatment group)

VI. Limitations and assumptions

- Discussion of any limitations of the study and potential sources of bias

- Assumptions made in the statistical analyses

VII. Conclusions

- A summary of the key findings and their implications

- A statement of whether the hypotheses were supported or not

- Suggestions for future research

Example of Research Results Section

An Example of a Research Results Section could be:

- This study sought to examine the relationship between sleep quality and academic performance in college students.

- Hypothesis : College students who report better sleep quality will have higher GPAs than those who report poor sleep quality.

- Methodology : Participants completed a survey about their sleep habits and academic performance.

II. Participants

- Participants were college students (N=200) from a mid-sized public university in the United States.

- The sample was evenly split by gender (50% female, 50% male) and predominantly white (85%).

- Participants were recruited through flyers and online advertisements.

III. Results

- Participants who reported better sleep quality had significantly higher GPAs (M=3.5, SD=0.5) than those who reported poor sleep quality (M=2.9, SD=0.6).

- See Table 1 for a summary of the results.

- Participants who reported consistent sleep schedules had higher GPAs than those with irregular sleep schedules.

IV. Discussion

- The results support the hypothesis that better sleep quality is associated with higher academic performance in college students.

- These findings have implications for college students, as prioritizing sleep could lead to better academic outcomes.

- Limitations of the study include self-reported data and the lack of control for other variables that could impact academic performance.

V. Conclusion

- College students who prioritize sleep may see a positive impact on their academic performance.

- These findings highlight the importance of sleep in academic success.

- Future research could explore interventions to improve sleep quality in college students.

Example of Research Results in Research Paper :

Our study aimed to compare the performance of three different machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Neural Network) in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company. We collected a dataset of 10,000 customer records, with 20 predictor variables and a binary churn outcome variable.

Our analysis revealed that all three algorithms performed well in predicting customer churn, with an overall accuracy of 85%. However, the Random Forest algorithm showed the highest accuracy (88%), followed by the Support Vector Machine (86%) and the Neural Network (84%).

Furthermore, we found that the most important predictor variables for customer churn were monthly charges, contract type, and tenure. Random Forest identified monthly charges as the most important variable, while Support Vector Machine and Neural Network identified contract type as the most important.

Overall, our results suggest that machine learning algorithms can be effective in predicting customer churn in a telecommunications company, and that Random Forest is the most accurate algorithm for this task.

Example 3 :

Title : The Impact of Social Media on Body Image and Self-Esteem

Abstract : This study aimed to investigate the relationship between social media use, body image, and self-esteem among young adults. A total of 200 participants were recruited from a university and completed self-report measures of social media use, body image satisfaction, and self-esteem.

Results: The results showed that social media use was significantly associated with body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem. Specifically, participants who reported spending more time on social media platforms had lower levels of body image satisfaction and self-esteem compared to those who reported less social media use. Moreover, the study found that comparing oneself to others on social media was a significant predictor of body image dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem.

Conclusion : These results suggest that social media use can have negative effects on body image satisfaction and self-esteem among young adults. It is important for individuals to be mindful of their social media use and to recognize the potential negative impact it can have on their mental health. Furthermore, interventions aimed at promoting positive body image and self-esteem should take into account the role of social media in shaping these attitudes and behaviors.

Importance of Research Results

Research results are important for several reasons, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research results can contribute to the advancement of knowledge in a particular field, whether it be in science, technology, medicine, social sciences, or humanities.

- Developing theories: Research results can help to develop or modify existing theories and create new ones.

- Improving practices: Research results can inform and improve practices in various fields, such as education, healthcare, business, and public policy.

- Identifying problems and solutions: Research results can identify problems and provide solutions to complex issues in society, including issues related to health, environment, social justice, and economics.

- Validating claims : Research results can validate or refute claims made by individuals or groups in society, such as politicians, corporations, or activists.

- Providing evidence: Research results can provide evidence to support decision-making, policy-making, and resource allocation in various fields.

How to Write Results in A Research Paper

Here are some general guidelines on how to write results in a research paper:

- Organize the results section: Start by organizing the results section in a logical and coherent manner. Divide the section into subsections if necessary, based on the research questions or hypotheses.

- Present the findings: Present the findings in a clear and concise manner. Use tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data and make the presentation more engaging.

- Describe the data: Describe the data in detail, including the sample size, response rate, and any missing data. Provide relevant descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations, and ranges.

- Interpret the findings: Interpret the findings in light of the research questions or hypotheses. Discuss the implications of the findings and the extent to which they support or contradict existing theories or previous research.

- Discuss the limitations : Discuss the limitations of the study, including any potential sources of bias or confounding factors that may have affected the results.

- Compare the results : Compare the results with those of previous studies or theoretical predictions. Discuss any similarities, differences, or inconsistencies.

- Avoid redundancy: Avoid repeating information that has already been presented in the introduction or methods sections. Instead, focus on presenting new and relevant information.

- Be objective: Be objective in presenting the results, avoiding any personal biases or interpretations.

When to Write Research Results

Here are situations When to Write Research Results”

- After conducting research on the chosen topic and obtaining relevant data, organize the findings in a structured format that accurately represents the information gathered.

- Once the data has been analyzed and interpreted, and conclusions have been drawn, begin the writing process.

- Before starting to write, ensure that the research results adhere to the guidelines and requirements of the intended audience, such as a scientific journal or academic conference.

- Begin by writing an abstract that briefly summarizes the research question, methodology, findings, and conclusions.

- Follow the abstract with an introduction that provides context for the research, explains its significance, and outlines the research question and objectives.

- The next section should be a literature review that provides an overview of existing research on the topic and highlights the gaps in knowledge that the current research seeks to address.

- The methodology section should provide a detailed explanation of the research design, including the sample size, data collection methods, and analytical techniques used.

- Present the research results in a clear and concise manner, using graphs, tables, and figures to illustrate the findings.

- Discuss the implications of the research results, including how they contribute to the existing body of knowledge on the topic and what further research is needed.

- Conclude the paper by summarizing the main findings, reiterating the significance of the research, and offering suggestions for future research.

Purpose of Research Results

The purposes of Research Results are as follows:

- Informing policy and practice: Research results can provide evidence-based information to inform policy decisions, such as in the fields of healthcare, education, and environmental regulation. They can also inform best practices in fields such as business, engineering, and social work.

- Addressing societal problems : Research results can be used to help address societal problems, such as reducing poverty, improving public health, and promoting social justice.

- Generating economic benefits : Research results can lead to the development of new products, services, and technologies that can create economic value and improve quality of life.

- Supporting academic and professional development : Research results can be used to support academic and professional development by providing opportunities for students, researchers, and practitioners to learn about new findings and methodologies in their field.

- Enhancing public understanding: Research results can help to educate the public about important issues and promote scientific literacy, leading to more informed decision-making and better public policy.

- Evaluating interventions: Research results can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, such as treatments, educational programs, and social policies. This can help to identify areas where improvements are needed and guide future interventions.

- Contributing to scientific progress: Research results can contribute to the advancement of science by providing new insights and discoveries that can lead to new theories, methods, and techniques.

- Informing decision-making : Research results can provide decision-makers with the information they need to make informed decisions. This can include decision-making at the individual, organizational, or governmental levels.

- Fostering collaboration : Research results can facilitate collaboration between researchers and practitioners, leading to new partnerships, interdisciplinary approaches, and innovative solutions to complex problems.

Advantages of Research Results

Some Advantages of Research Results are as follows:

- Improved decision-making: Research results can help inform decision-making in various fields, including medicine, business, and government. For example, research on the effectiveness of different treatments for a particular disease can help doctors make informed decisions about the best course of treatment for their patients.

- Innovation : Research results can lead to the development of new technologies, products, and services. For example, research on renewable energy sources can lead to the development of new and more efficient ways to harness renewable energy.

- Economic benefits: Research results can stimulate economic growth by providing new opportunities for businesses and entrepreneurs. For example, research on new materials or manufacturing techniques can lead to the development of new products and processes that can create new jobs and boost economic activity.

- Improved quality of life: Research results can contribute to improving the quality of life for individuals and society as a whole. For example, research on the causes of a particular disease can lead to the development of new treatments and cures, improving the health and well-being of millions of people.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Results/Findings Section in Research

What is the research paper Results section and what does it do?

The Results section of a scientific research paper represents the core findings of a study derived from the methods applied to gather and analyze information. It presents these findings in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation from the author, setting up the reader for later interpretation and evaluation in the Discussion section. A major purpose of the Results section is to break down the data into sentences that show its significance to the research question(s).

The Results section appears third in the section sequence in most scientific papers. It follows the presentation of the Methods and Materials and is presented before the Discussion section —although the Results and Discussion are presented together in many journals. This section answers the basic question “What did you find in your research?”

What is included in the Results section?

The Results section should include the findings of your study and ONLY the findings of your study. The findings include:

- Data presented in tables, charts, graphs, and other figures (may be placed into the text or on separate pages at the end of the manuscript)

- A contextual analysis of this data explaining its meaning in sentence form

- All data that corresponds to the central research question(s)

- All secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

If the scope of the study is broad, or if you studied a variety of variables, or if the methodology used yields a wide range of different results, the author should present only those results that are most relevant to the research question stated in the Introduction section .

As a general rule, any information that does not present the direct findings or outcome of the study should be left out of this section. Unless the journal requests that authors combine the Results and Discussion sections, explanations and interpretations should be omitted from the Results.

How are the results organized?

The best way to organize your Results section is “logically.” One logical and clear method of organizing research results is to provide them alongside the research questions—within each research question, present the type of data that addresses that research question.

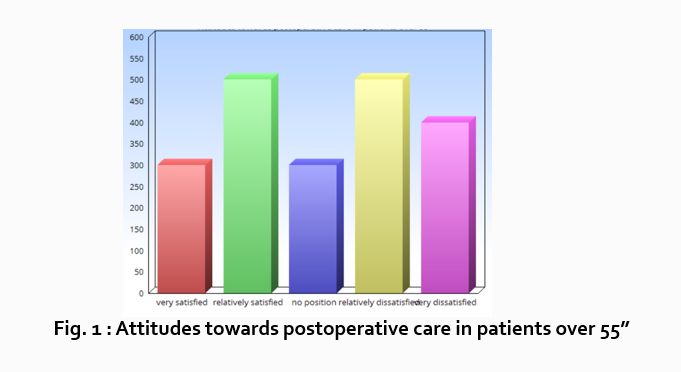

Let’s look at an example. Your research question is based on a survey among patients who were treated at a hospital and received postoperative care. Let’s say your first research question is:

“What do hospital patients over age 55 think about postoperative care?”

This can actually be represented as a heading within your Results section, though it might be presented as a statement rather than a question:

Attitudes towards postoperative care in patients over the age of 55

Now present the results that address this specific research question first. In this case, perhaps a table illustrating data from a survey. Likert items can be included in this example. Tables can also present standard deviations, probabilities, correlation matrices, etc.

Following this, present a content analysis, in words, of one end of the spectrum of the survey or data table. In our example case, start with the POSITIVE survey responses regarding postoperative care, using descriptive phrases. For example:

“Sixty-five percent of patients over 55 responded positively to the question “ Are you satisfied with your hospital’s postoperative care ?” (Fig. 2)

Include other results such as subcategory analyses. The amount of textual description used will depend on how much interpretation of tables and figures is necessary and how many examples the reader needs in order to understand the significance of your research findings.

Next, present a content analysis of another part of the spectrum of the same research question, perhaps the NEGATIVE or NEUTRAL responses to the survey. For instance:

“As Figure 1 shows, 15 out of 60 patients in Group A responded negatively to Question 2.”

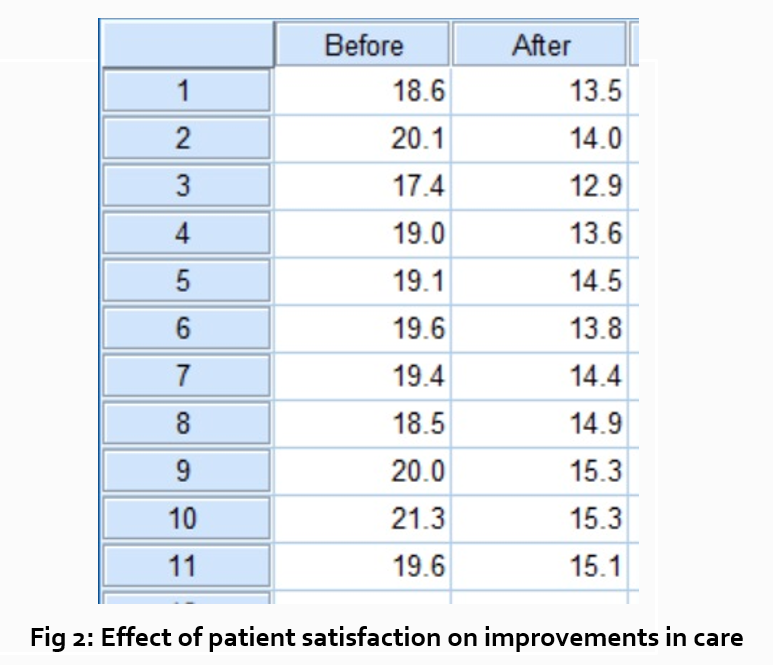

After you have assessed the data in one figure and explained it sufficiently, move on to your next research question. For example:

“How does patient satisfaction correspond to in-hospital improvements made to postoperative care?”

This kind of data may be presented through a figure or set of figures (for instance, a paired T-test table).

Explain the data you present, here in a table, with a concise content analysis:

“The p-value for the comparison between the before and after groups of patients was .03% (Fig. 2), indicating that the greater the dissatisfaction among patients, the more frequent the improvements that were made to postoperative care.”

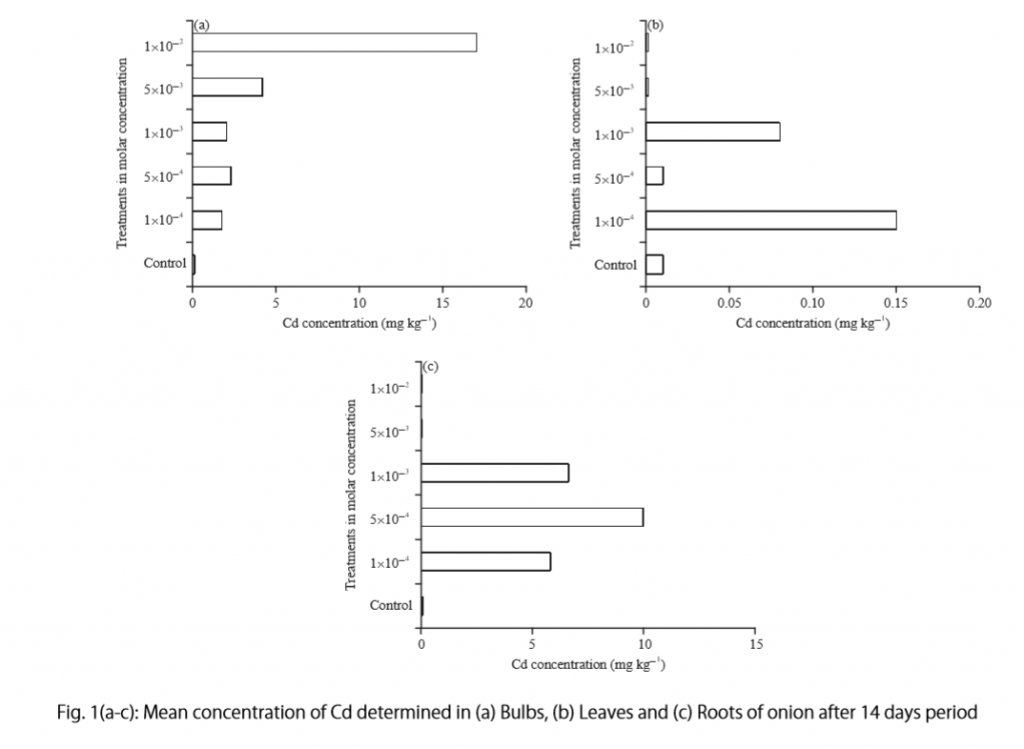

Let’s examine another example of a Results section from a study on plant tolerance to heavy metal stress . In the Introduction section, the aims of the study are presented as “determining the physiological and morphological responses of Allium cepa L. towards increased cadmium toxicity” and “evaluating its potential to accumulate the metal and its associated environmental consequences.” The Results section presents data showing how these aims are achieved in tables alongside a content analysis, beginning with an overview of the findings:

“Cadmium caused inhibition of root and leave elongation, with increasing effects at higher exposure doses (Fig. 1a-c).”

The figure containing this data is cited in parentheses. Note that this author has combined three graphs into one single figure. Separating the data into separate graphs focusing on specific aspects makes it easier for the reader to assess the findings, and consolidating this information into one figure saves space and makes it easy to locate the most relevant results.

Following this overall summary, the relevant data in the tables is broken down into greater detail in text form in the Results section.

- “Results on the bio-accumulation of cadmium were found to be the highest (17.5 mg kgG1) in the bulb, when the concentration of cadmium in the solution was 1×10G2 M and lowest (0.11 mg kgG1) in the leaves when the concentration was 1×10G3 M.”

Captioning and Referencing Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are central components of your Results section and you need to carefully think about the most effective way to use graphs and tables to present your findings . Therefore, it is crucial to know how to write strong figure captions and to refer to them within the text of the Results section.

The most important advice one can give here as well as throughout the paper is to check the requirements and standards of the journal to which you are submitting your work. Every journal has its own design and layout standards, which you can find in the author instructions on the target journal’s website. Perusing a journal’s published articles will also give you an idea of the proper number, size, and complexity of your figures.

Regardless of which format you use, the figures should be placed in the order they are referenced in the Results section and be as clear and easy to understand as possible. If there are multiple variables being considered (within one or more research questions), it can be a good idea to split these up into separate figures. Subsequently, these can be referenced and analyzed under separate headings and paragraphs in the text.

To create a caption, consider the research question being asked and change it into a phrase. For instance, if one question is “Which color did participants choose?”, the caption might be “Color choice by participant group.” Or in our last research paper example, where the question was “What is the concentration of cadmium in different parts of the onion after 14 days?” the caption reads:

“Fig. 1(a-c): Mean concentration of Cd determined in (a) bulbs, (b) leaves, and (c) roots of onions after a 14-day period.”

Steps for Composing the Results Section

Because each study is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to designing a strategy for structuring and writing the section of a research paper where findings are presented. The content and layout of this section will be determined by the specific area of research, the design of the study and its particular methodologies, and the guidelines of the target journal and its editors. However, the following steps can be used to compose the results of most scientific research studies and are essential for researchers who are new to preparing a manuscript for publication or who need a reminder of how to construct the Results section.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the target journal or publisher provides authors and read research papers it has published, especially those with similar topics, methods, or results to your study.

- The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches.

- Note length limitations on restrictions on content. For instance, while many journals require the Results and Discussion sections to be separate, others do not—qualitative research papers often include results and interpretations in the same section (“Results and Discussion”).

- Reading the aims and scope in the journal’s “ guide for authors ” section and understanding the interests of its readers will be invaluable in preparing to write the Results section.

Step 2 : Consider your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements and catalogue your results.

- Focus on experimental results and other findings that are especially relevant to your research questions and objectives and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses.

- Catalogue your findings—use subheadings to streamline and clarify your report. This will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Create appendices that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers.

- Decide how you will structure of your results. You might match the order of the research questions and hypotheses to your results, or you could arrange them according to the order presented in the Methods section. A chronological order or even a hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. Consider your audience, evidence, and most importantly, the objectives of your research when choosing a structure for presenting your findings.

Step 3 : Design figures and tables to present and illustrate your data.

- Tables and figures should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the main text of the paper.

- Information in figures should be relatively self-explanatory (with the aid of captions), and their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for readers to understand the findings without reading all of the text.

- Use tables and figures as a focal point to tell a clear and informative story about your research and avoid repeating information. But remember that while figures clarify and enhance the text, they cannot replace it.

Step 4 : Draft your Results section using the findings and figures you have organized.

- The goal is to communicate this complex information as clearly and precisely as possible; precise and compact phrases and sentences are most effective.

- In the opening paragraph of this section, restate your research questions or aims to focus the reader’s attention to what the results are trying to show. It is also a good idea to summarize key findings at the end of this section to create a logical transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows.

- Try to write in the past tense and the active voice to relay the findings since the research has already been done and the agent is usually clear. This will ensure that your explanations are also clear and logical.

- Make sure that any specialized terminology or abbreviation you have used here has been defined and clarified in the Introduction section .

Step 5 : Review your draft; edit and revise until it reports results exactly as you would like to have them reported to your readers.

- Double-check the accuracy and consistency of all the data, as well as all of the visual elements included.

- Read your draft aloud to catch language errors (grammar, spelling, and mechanics), awkward phrases, and missing transitions.

- Ensure that your results are presented in the best order to focus on objectives and prepare readers for interpretations, valuations, and recommendations in the Discussion section . Look back over the paper’s Introduction and background while anticipating the Discussion and Conclusion sections to ensure that the presentation of your results is consistent and effective.

- Consider seeking additional guidance on your paper. Find additional readers to look over your Results section and see if it can be improved in any way. Peers, professors, or qualified experts can provide valuable insights.

One excellent option is to use a professional English proofreading and editing service such as Wordvice, including our paper editing service . With hundreds of qualified editors from dozens of scientific fields, Wordvice has helped thousands of authors revise their manuscripts and get accepted into their target journals. Read more about the proofreading and editing process before proceeding with getting academic editing services and manuscript editing services for your manuscript.

As the representation of your study’s data output, the Results section presents the core information in your research paper. By writing with clarity and conciseness and by highlighting and explaining the crucial findings of their study, authors increase the impact and effectiveness of their research manuscripts.

For more articles and videos on writing your research manuscript, visit Wordvice’s Resources page.

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

- Manuscript Preparation

How to write the results section of a research paper

- 3 minute read

Table of Contents

At its core, a research paper aims to fill a gap in the research on a given topic. As a result, the results section of the paper, which describes the key findings of the study, is often considered the core of the paper. This is the section that gets the most attention from reviewers, peers, students, and any news organization reporting on your findings. Writing a clear, concise, and logical results section is, therefore, one of the most important parts of preparing your manuscript.

Difference between results and discussion

Before delving into how to write the results section, it is important to first understand the difference between the results and discussion sections. The results section needs to detail the findings of the study. The aim of this section is not to draw connections between the different findings or to compare it to previous findings in literature—that is the purview of the discussion section. Unlike the discussion section, which can touch upon the hypothetical, the results section needs to focus on the purely factual. In some cases, it may even be preferable to club these two sections together into a single section. For example, while writing a review article, it can be worthwhile to club these two sections together, as the main results in this case are the conclusions that can be drawn from the literature.

Structure of the results section

Although the main purpose of the results section in a research paper is to report the findings, it is necessary to present an introduction and repeat the research question. This establishes a connection to the previous section of the paper and creates a smooth flow of information.

Next, the results section needs to communicate the findings of your research in a systematic manner. The section needs to be organized such that the primary research question is addressed first, then the secondary research questions. If the research addresses multiple questions, the results section must individually connect with each of the questions. This ensures clarity and minimizes confusion while reading.

Consider representing your results visually. For example, graphs, tables, and other figures can help illustrate the findings of your paper, especially if there is a large amount of data in the results.

Remember, an appealing results section can help peer reviewers better understand the merits of your research, thereby increasing your chances of publication.

Practical guidance for writing an effective results section for a research paper

- Always use simple and clear language. Avoid the use of uncertain or out-of-focus expressions.

- The findings of the study must be expressed in an objective and unbiased manner. While it is acceptable to correlate certain findings in the discussion section, it is best to avoid overinterpreting the results.

- If the research addresses more than one hypothesis, use sub-sections to describe the results. This prevents confusion and promotes understanding.

- Ensure that negative results are included in this section, even if they do not support the research hypothesis.

- Wherever possible, use illustrations like tables, figures, charts, or other visual representations to showcase the results of your research paper. Mention these illustrations in the text, but do not repeat the information that they convey.

- For statistical data, it is adequate to highlight the tests and explain their results. The initial or raw data should not be mentioned in the results section of a research paper.

The results section of a research paper is usually the most impactful section because it draws the greatest attention. Regardless of the subject of your research paper, a well-written results section is capable of generating interest in your research.

For detailed information and assistance on writing the results of a research paper, refer to Elsevier Author Services.

- Research Process

Writing a good review article

Why is data validation important in research?

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

How To Write The Results/Findings Chapter

For quantitative studies (dissertations & theses).

By: Derek Jansen (MBA). Expert Reviewed By: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | July 2021

So, you’ve completed your quantitative data analysis and it’s time to report on your findings. But where do you start? In this post, we’ll walk you through the results chapter (also called the findings or analysis chapter), step by step, so that you can craft this section of your dissertation or thesis with confidence. If you’re looking for information regarding the results chapter for qualitative studies, you can find that here .

Overview: Quantitative Results Chapter

- What exactly the results/findings/analysis chapter is

- What you need to include in your results chapter

- How to structure your results chapter

- A few tips and tricks for writing top-notch chapter

What exactly is the results chapter?

The results chapter (also referred to as the findings or analysis chapter) is one of the most important chapters of your dissertation or thesis because it shows the reader what you’ve found in terms of the quantitative data you’ve collected. It presents the data using a clear text narrative, supported by tables, graphs and charts. In doing so, it also highlights any potential issues (such as outliers or unusual findings) you’ve come across.

But how’s that different from the discussion chapter?

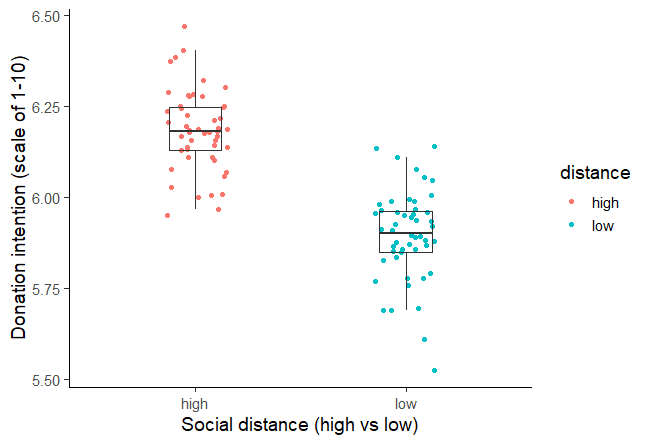

Well, in the results chapter, you only present your statistical findings. Only the numbers, so to speak – no more, no less. Contrasted to this, in the discussion chapter , you interpret your findings and link them to prior research (i.e. your literature review), as well as your research objectives and research questions . In other words, the results chapter presents and describes the data, while the discussion chapter interprets the data.

Let’s look at an example.

In your results chapter, you may have a plot that shows how respondents to a survey responded: the numbers of respondents per category, for instance. You may also state whether this supports a hypothesis by using a p-value from a statistical test. But it is only in the discussion chapter where you will say why this is relevant or how it compares with the literature or the broader picture. So, in your results chapter, make sure that you don’t present anything other than the hard facts – this is not the place for subjectivity.

It’s worth mentioning that some universities prefer you to combine the results and discussion chapters. Even so, it is good practice to separate the results and discussion elements within the chapter, as this ensures your findings are fully described. Typically, though, the results and discussion chapters are split up in quantitative studies. If you’re unsure, chat with your research supervisor or chair to find out what their preference is.

What should you include in the results chapter?

Following your analysis, it’s likely you’ll have far more data than are necessary to include in your chapter. In all likelihood, you’ll have a mountain of SPSS or R output data, and it’s your job to decide what’s most relevant. You’ll need to cut through the noise and focus on the data that matters.

This doesn’t mean that those analyses were a waste of time – on the contrary, those analyses ensure that you have a good understanding of your dataset and how to interpret it. However, that doesn’t mean your reader or examiner needs to see the 165 histograms you created! Relevance is key.

How do I decide what’s relevant?

At this point, it can be difficult to strike a balance between what is and isn’t important. But the most important thing is to ensure your results reflect and align with the purpose of your study . So, you need to revisit your research aims, objectives and research questions and use these as a litmus test for relevance. Make sure that you refer back to these constantly when writing up your chapter so that you stay on track.

As a general guide, your results chapter will typically include the following:

- Some demographic data about your sample

- Reliability tests (if you used measurement scales)

- Descriptive statistics

- Inferential statistics (if your research objectives and questions require these)

- Hypothesis tests (again, if your research objectives and questions require these)

We’ll discuss each of these points in more detail in the next section.

Importantly, your results chapter needs to lay the foundation for your discussion chapter . This means that, in your results chapter, you need to include all the data that you will use as the basis for your interpretation in the discussion chapter.

For example, if you plan to highlight the strong relationship between Variable X and Variable Y in your discussion chapter, you need to present the respective analysis in your results chapter – perhaps a correlation or regression analysis.

Need a helping hand?

How do I write the results chapter?

There are multiple steps involved in writing up the results chapter for your quantitative research. The exact number of steps applicable to you will vary from study to study and will depend on the nature of the research aims, objectives and research questions . However, we’ll outline the generic steps below.

Step 1 – Revisit your research questions

The first step in writing your results chapter is to revisit your research objectives and research questions . These will be (or at least, should be!) the driving force behind your results and discussion chapters, so you need to review them and then ask yourself which statistical analyses and tests (from your mountain of data) would specifically help you address these . For each research objective and research question, list the specific piece (or pieces) of analysis that address it.

At this stage, it’s also useful to think about the key points that you want to raise in your discussion chapter and note these down so that you have a clear reminder of which data points and analyses you want to highlight in the results chapter. Again, list your points and then list the specific piece of analysis that addresses each point.

Next, you should draw up a rough outline of how you plan to structure your chapter . Which analyses and statistical tests will you present and in what order? We’ll discuss the “standard structure” in more detail later, but it’s worth mentioning now that it’s always useful to draw up a rough outline before you start writing (this advice applies to any chapter).

Step 2 – Craft an overview introduction

As with all chapters in your dissertation or thesis, you should start your quantitative results chapter by providing a brief overview of what you’ll do in the chapter and why . For example, you’d explain that you will start by presenting demographic data to understand the representativeness of the sample, before moving onto X, Y and Z.

This section shouldn’t be lengthy – a paragraph or two maximum. Also, it’s a good idea to weave the research questions into this section so that there’s a golden thread that runs through the document.

Step 3 – Present the sample demographic data

The first set of data that you’ll present is an overview of the sample demographics – in other words, the demographics of your respondents.

For example:

- What age range are they?

- How is gender distributed?

- How is ethnicity distributed?

- What areas do the participants live in?

The purpose of this is to assess how representative the sample is of the broader population. This is important for the sake of the generalisability of the results. If your sample is not representative of the population, you will not be able to generalise your findings. This is not necessarily the end of the world, but it is a limitation you’ll need to acknowledge.

Of course, to make this representativeness assessment, you’ll need to have a clear view of the demographics of the population. So, make sure that you design your survey to capture the correct demographic information that you will compare your sample to.

But what if I’m not interested in generalisability?

Well, even if your purpose is not necessarily to extrapolate your findings to the broader population, understanding your sample will allow you to interpret your findings appropriately, considering who responded. In other words, it will help you contextualise your findings . For example, if 80% of your sample was aged over 65, this may be a significant contextual factor to consider when interpreting the data. Therefore, it’s important to understand and present the demographic data.

Step 4 – Review composite measures and the data “shape”.

Before you undertake any statistical analysis, you’ll need to do some checks to ensure that your data are suitable for the analysis methods and techniques you plan to use. If you try to analyse data that doesn’t meet the assumptions of a specific statistical technique, your results will be largely meaningless. Therefore, you may need to show that the methods and techniques you’ll use are “allowed”.

Most commonly, there are two areas you need to pay attention to:

#1: Composite measures

The first is when you have multiple scale-based measures that combine to capture one construct – this is called a composite measure . For example, you may have four Likert scale-based measures that (should) all measure the same thing, but in different ways. In other words, in a survey, these four scales should all receive similar ratings. This is called “ internal consistency ”.

Internal consistency is not guaranteed though (especially if you developed the measures yourself), so you need to assess the reliability of each composite measure using a test. Typically, Cronbach’s Alpha is a common test used to assess internal consistency – i.e., to show that the items you’re combining are more or less saying the same thing. A high alpha score means that your measure is internally consistent. A low alpha score means you may need to consider scrapping one or more of the measures.

#2: Data shape

The second matter that you should address early on in your results chapter is data shape. In other words, you need to assess whether the data in your set are symmetrical (i.e. normally distributed) or not, as this will directly impact what type of analyses you can use. For many common inferential tests such as T-tests or ANOVAs (we’ll discuss these a bit later), your data needs to be normally distributed. If it’s not, you’ll need to adjust your strategy and use alternative tests.

To assess the shape of the data, you’ll usually assess a variety of descriptive statistics (such as the mean, median and skewness), which is what we’ll look at next.

Step 5 – Present the descriptive statistics

Now that you’ve laid the foundation by discussing the representativeness of your sample, as well as the reliability of your measures and the shape of your data, you can get started with the actual statistical analysis. The first step is to present the descriptive statistics for your variables.

For scaled data, this usually includes statistics such as:

- The mean – this is simply the mathematical average of a range of numbers.

- The median – this is the midpoint in a range of numbers when the numbers are arranged in order.

- The mode – this is the most commonly repeated number in the data set.

- Standard deviation – this metric indicates how dispersed a range of numbers is. In other words, how close all the numbers are to the mean (the average).

- Skewness – this indicates how symmetrical a range of numbers is. In other words, do they tend to cluster into a smooth bell curve shape in the middle of the graph (this is called a normal or parametric distribution), or do they lean to the left or right (this is called a non-normal or non-parametric distribution).

- Kurtosis – this metric indicates whether the data are heavily or lightly-tailed, relative to the normal distribution. In other words, how peaked or flat the distribution is.

A large table that indicates all the above for multiple variables can be a very effective way to present your data economically. You can also use colour coding to help make the data more easily digestible.

For categorical data, where you show the percentage of people who chose or fit into a category, for instance, you can either just plain describe the percentages or numbers of people who responded to something or use graphs and charts (such as bar graphs and pie charts) to present your data in this section of the chapter.

When using figures, make sure that you label them simply and clearly , so that your reader can easily understand them. There’s nothing more frustrating than a graph that’s missing axis labels! Keep in mind that although you’ll be presenting charts and graphs, your text content needs to present a clear narrative that can stand on its own. In other words, don’t rely purely on your figures and tables to convey your key points: highlight the crucial trends and values in the text. Figures and tables should complement the writing, not carry it .

Depending on your research aims, objectives and research questions, you may stop your analysis at this point (i.e. descriptive statistics). However, if your study requires inferential statistics, then it’s time to deep dive into those .

Step 6 – Present the inferential statistics

Inferential statistics are used to make generalisations about a population , whereas descriptive statistics focus purely on the sample . Inferential statistical techniques, broadly speaking, can be broken down into two groups .

First, there are those that compare measurements between groups , such as t-tests (which measure differences between two groups) and ANOVAs (which measure differences between multiple groups). Second, there are techniques that assess the relationships between variables , such as correlation analysis and regression analysis. Within each of these, some tests can be used for normally distributed (parametric) data and some tests are designed specifically for use on non-parametric data.

There are a seemingly endless number of tests that you can use to crunch your data, so it’s easy to run down a rabbit hole and end up with piles of test data. Ultimately, the most important thing is to make sure that you adopt the tests and techniques that allow you to achieve your research objectives and answer your research questions .

In this section of the results chapter, you should try to make use of figures and visual components as effectively as possible. For example, if you present a correlation table, use colour coding to highlight the significance of the correlation values, or scatterplots to visually demonstrate what the trend is. The easier you make it for your reader to digest your findings, the more effectively you’ll be able to make your arguments in the next chapter.

Step 7 – Test your hypotheses

If your study requires it, the next stage is hypothesis testing. A hypothesis is a statement , often indicating a difference between groups or relationship between variables, that can be supported or rejected by a statistical test. However, not all studies will involve hypotheses (again, it depends on the research objectives), so don’t feel like you “must” present and test hypotheses just because you’re undertaking quantitative research.

The basic process for hypothesis testing is as follows:

- Specify your null hypothesis (for example, “The chemical psilocybin has no effect on time perception).

- Specify your alternative hypothesis (e.g., “The chemical psilocybin has an effect on time perception)

- Set your significance level (this is usually 0.05)

- Calculate your statistics and find your p-value (e.g., p=0.01)

- Draw your conclusions (e.g., “The chemical psilocybin does have an effect on time perception”)

Finally, if the aim of your study is to develop and test a conceptual framework , this is the time to present it, following the testing of your hypotheses. While you don’t need to develop or discuss these findings further in the results chapter, indicating whether the tests (and their p-values) support or reject the hypotheses is crucial.

Step 8 – Provide a chapter summary

To wrap up your results chapter and transition to the discussion chapter, you should provide a brief summary of the key findings . “Brief” is the keyword here – much like the chapter introduction, this shouldn’t be lengthy – a paragraph or two maximum. Highlight the findings most relevant to your research objectives and research questions, and wrap it up.

Some final thoughts, tips and tricks

Now that you’ve got the essentials down, here are a few tips and tricks to make your quantitative results chapter shine:

- When writing your results chapter, report your findings in the past tense . You’re talking about what you’ve found in your data, not what you are currently looking for or trying to find.

- Structure your results chapter systematically and sequentially . If you had two experiments where findings from the one generated inputs into the other, report on them in order.

- Make your own tables and graphs rather than copying and pasting them from statistical analysis programmes like SPSS. Check out the DataIsBeautiful reddit for some inspiration.

- Once you’re done writing, review your work to make sure that you have provided enough information to answer your research questions , but also that you didn’t include superfluous information.

If you’ve got any questions about writing up the quantitative results chapter, please leave a comment below. If you’d like 1-on-1 assistance with your quantitative analysis and discussion, check out our hands-on coaching service , or book a free consultation with a friendly coach.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

Thank you. I will try my best to write my results.

Awesome content 👏🏾

this was great explaination

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Write the Results Section of a Research Paper

Table of Contents

Laura Moro-Martin, freelance scientific writer on Kolabtree, provides expert tips on how to write the results section of a research paper .

You have prepared a detailed −but concise− Methods section . Now it is time to write the Results of your research article. This part of the paper reports the findings of the experiments that you conducted to answer the research question(s). The Results can be considered the nucleus of a scientific article because they justify your claims, so you need to ensure that they are clear and understandable. You are telling a story −of course, a scientific story− and you want the readers to picture that same story in their minds. Let’s see how to avoid that your message ends up as in the ‘telephone game’.

The Results Section: Goals and Structure

Depending on the discipline, journal, and the nature of the study, the structure of the article can differ. We will focus on articles were the Results and Discussion appear in two separate sections, but it is possible in some cases to combine them.

In the Results section, you provide an overall description of the experiments and present the data that you obtained in a logical order, using tables and graphs as necessary. The Results section should simply state your findings without bias or interpretation. For example, in your analysis, you may have noticed a significant correlation between two variables never described before. It is correct to explain this in the Results section. However, speculation about the reasons for this correlation should go in the Discussion section of your paper.

In general, the Results section includes the following elements:

- A very short introductory context that repeats the research question and helps to understand your results.

- Report on data collection, recruitment, and/or participants. For example, in the case of clinical research, it is common to include a first table summarizing the demographic, clinical, and other relevant characteristics of the study participants.

- A systematic description of the main findings in a logical order (generally following the order of the Methods section), highlighting the most relevant results.

- Other important secondary findings, such as secondary outcomes or subgroup analyses (remember that you do not need to mention any single result).

- Visual elements, such as, figures, charts, maps, tables, etc. that summarize and illustrate the findings. These elements should be cited in the text and numbered in order. Figures and tables should be able to stand on its own without the text, which means that the legend should include enough information to understand the non-textual element.

How to Write the Results Section of a Research Paper: Tips

The first tip −applicable to other sections of the paper too− is to check and apply the requirements of the journal to which you are submitting your work.

In the Results section, you need to write concisely and objectively, leaving interpretation for the Discussion section. As always, ‘learning from others’ can help you. Select a few papers from your field, including some published in your target journal, which you consider ‘good quality’ and well written. Read them carefully and observe how the Results section is structured, the type and amount of information provided, and how the findings are exposed in a logical order. Keep an eye on visual elements, such as figures, tables, and supplementary materials. Understand what works well in those papers to effectively convey their findings, and apply it to your writing.

Your Results section needs to describe the sequence of what you did and found, the frequency of occurrence of a particular event or result, the quantities of your observations, and the causality (i.e. the relationships or connections) between the events that you observed.

To organize the results, you can try to provide them alongside the research questions. In practice, this means that you will organize this section based on the sequence of tables and figures summarizing the results of your statistical analysis. In this way, it will be easier for readers to look at and understand your findings. You need to report your statistical findings, without describing every step of your statistical analysis. Tables and figures generally report summary-level data (for example, means and standard deviations), rather than all the raw data.

Following, you can prepare the summary text to support those visual elements. You need not only to present but also to explain your findings, showing how they help to address the research question(s) and how they align with the objectives that you presented in the Introduction . Keep in mind that results do not speak for themselves, so if you do not describe them in words, the reader may perceive the findings differently from you. Build coherence along this section using goal statements and explicit reasoning (guide the reader through your reasoning, including sentences of this type: ‘In order to…, we performed….’; ‘In view of this result, we ….’, etc.).

In summary, the general steps for writing the Results section of a research article are:

- Check the guidelines of your target journal and read articles that it has published in similar topics to your study.

- Catalogue your findings in relation to the journal requirements, and design figures and tables to organize your data.

- Write the Results section following the order of figures and tables.

- Edit and revise your draft and seek additional input from colleagues or experts.

The Style of the Results Section

‘If you are out to describe the truth, leave elegance to the tailor’, Austrian physicist Ludwig Boltzmann said. Although the scope of the Results section −and of scientific papers in general− is eminently functional, this does not mean that you cannot write well. Try to improve the rhythm to move the reader along, use transitions and connectors between different sections and paragraphs, and dedicate time to revise your writing.

The Results section should be written in the past tense. Although writing in the passive voice may be tempting, the use of the active voice makes the action much more visualizable. The passive voice weakens the power of language and increases the number of words needed to say the same thing, so we recommend using the active voice as much as possible. Another tip to make your language visualizable and reduce sentence length is the use of verbal phrases instead of long nouns. For example, instead of writing ‘As shown in Table 1, there was a significant increase in gene expression’, you can say ‘As shown in Table 1, gene expression increased significantly’.

Get a Second (And Even Third) Opinion

Writing a scientific article is not an individual work. Take advantage of your co-authors by making them check the Results section and adding their comments and suggestions. Not only that, but an external opinion will help you to identify misinterpretations or errors. Ask a colleague that is not directly involved in the work to review your Results and then try to evaluate what your colleague did or did not understand. If needed, seek additional help from a qualified expert.

Common Errors to Avoid While Writing the Results Section

Several mistakes frequently occur when you write the Results section of a research paper. Here we have collected a few examples:

- Including raw results and/or endlessly repetitive data. You do not need to present every single number and calculation, but a summary of the results. If relevant, raw data can be included in supplementary materials.

- Including redundant information. If data are contained in the tables or figures, you do not need to repeat all of them in the Results section. You will have the opportunity to highlight the most relevant results in the Discussion .

- Repeating background information or methods , or introducing several sentences of introductory information (if you feel that more background information is necessary to present a result, consider inserting that information in the Introduction ).

- Results and Methods do not match . You need to explain the methodology used to obtain all the experimental observations.

- Ignoring negative results or results that do not support the conclusions. In addition to posing potential ethical concerns on your work, reviewers will not like it. You need to mention all relevant findings, even if they failed to support your predictions or hypotheses. Negative results are useful and will guide future studies on the topic. Provide your interpretation for negative results in the Discussion .

- Discussing or interpreting the results . Leave that for the Discussion , unless your target journal allows preparing one section combining Results and Discussion .

- Errors in figures/tables are varied and common . Examples of errors include using an excessive number of figures/tables (it is a good idea to select the most relevant ones and move the rest to supplementary materials), very complex figures/tables (hard-to-read figures with many subfigures or enormous tables may confuse your readers; think how these elements will be visualized in the final format of the article), difficult to interpret figures/tables (cryptic abbreviations; inadequate use of colors, axis, scales, symbols, etc.), and figures/tables that are not self-standing (figures/tables require a caption, all abbreviations used need to be explained in the legend or a footnote, and statistical tests applied are frequently reported). Do not include tables and figures that are not mentioned in the body text of your Results .

In summary, the Results section is the nucleus of your paper that justifies your claims. Take time to adequately organize it and prepare understandable figures and tables to convey your message to the reader. Good writing!

- The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. https://abacus.bates.edu/~ganderso/biology/resources/writing/HTWsections.html – methods (accessed on 30th September 2020)

- Organizing Academic Research Papers: 7. The Results. https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185931 (accessed on 30th September 2020)

- Kendra Cherry. How to Write an APA Results Section. https://www.verywellmind.com/how-to-write-a-results-section-2795727 (accessed on 30th September 2020)

- Chapin Rodríguez. Empowering your scientific language by making it “visualizable”. http://creaducate.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/tipsheet36_visualizable-lang-tip-sheet.pdf (accessed on 1st October 2020)

- IMRaD Results Discussion. https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/guides/imrad-results-discussion (accessed on 1st October 2020)

- Writing the Results Section for a Research Paper. https://wordvice.com/writing-the-results-section-for-a-research-paper/ (accessed on 1st October 2020)

- Scott L. Montgomery. The Chicago Guide to Communicating Science , Chapter 9. Second edition, The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

- Hilary Glasman-Deal . Science Research Writing for Non-Native Speakers of English, Unit 2 . Imperial College Press, 2010.

Unlock Corporate Benefits • Secure Payment Assistance • Onboarding Support • Dedicated Account Manager

Sign up with your professional email to avail special advances offered against purchase orders, seamless multi-channel payments, and extended support for agreements.

About Author

Ramya Sriram manages digital content and communications at Kolabtree (kolabtree.com), the world's largest freelancing platform for scientists. She has over a decade of experience in publishing, advertising and digital content creation.

Related Posts

Spotlight: kolabtree’s regulatory medical writer dr. nare simonyan, how healthcare writers can help your business , the benefits of outsourcing in continuing medical education (cme), leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Automated page speed optimizations for fast site performance

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The results section is where you report the findings of your study based upon the methodology [or methodologies] you applied to gather information. The results section should state the findings of the research arranged in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation. A section describing results should be particularly detailed if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Findings can only confirm or reject the hypothesis underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise. Use non-textual elements appropriately, such as figures and tables, to present findings more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish information that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other content that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data that has not been summarized should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good strategy is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper that follows].

Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Brett, Paul. "A Genre Analysis of the Results Section of Sociology Articles." English for Specific Speakers 13 (1994): 47-59; Go to English for Specific Purposes on ScienceDirect;Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit; "Reporting Findings." In Making Sense of Social Research Malcolm Williams, editor. (London;: SAGE Publications, 2003) pp. 188-207.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Organization and Approach