- Corpus ID: 8690309

Organic Farming in Sri Lanka

- U. R. Sangakkara

- Published 2004

- Agricultural and Food Sciences

7 Citations

Farmers’ attitude towards organic agriculture: a case of rural sri lanka, challenges and way-forward of non-organic agriculture to organic agriculture: a comparative study between china and sri lanka, agricultural research for sustainable food systems in sri lanka: volume 1: a historical perspective, consumer purchase intention towards organic food ; with special reference to undergraduates in sri lanka, the impact of chemical fertilizer ban on the paddy sector: propensity score matching and value chain analysis, effect of partially-burnt paddy husk as a supplementary source of potassium on growth and yield of turmeric (curcuma longa l.) and soil properties, underutilized crops in the agricultural farms of southeastern sri lanka: farmers’ knowledge, preference, and contribution to household economy, 4 references, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 12 October 2021

Climate change and food security in Sri Lanka: towards food sovereignty

- Mahinda Senevi Gunaratne ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2296-900X 1 ,

- R. B. Radin Firdaus ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7022-0576 1 &

- Shamila Indika Rathnasooriya 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 229 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

32k Accesses

25 Citations

34 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

- Environmental studies

- Social policy

This study explored food security and climate change issues and assessed how food sovereignty contributes to addressing the climate change impacts on entire food systems. The study aimed to contextualise food security, climate change, and food sovereignty within Sri Lanka’s current development discourse by bringing global learning, experience, and scholarship together. While this paper focused on many of the most pressing issues in this regard, it also highlighted potential paths towards food sovereignty in the context of policy reforms. This study used a narrative review that relied on the extant literature to understand the underlying concepts and issues relating to climate change, food security and food sovereignty. Additionally, eight in-depth interviews were conducted to obtain experts’ views on Sri Lanka’s issues relating to the thematic areas of this study and to find ways forward. The key findings from the literature review suggest that climate change has adverse impacts on global food security, escalating poverty, hunger, and malnutrition, which adversely affect developing nations and the poor and marginalised communities disproportionately. This study argues that promoting food sovereignty could be the key to alleviating such impacts. Food sovereignty has received much attention as an alternative development path in international forums and policy dialogues while it already applies in development practice. Since the island nation has been facing many challenges in food security, poverty, climate change, and persistence of development disparities, scaling up to food sovereignty in Sri Lanka requires significant policy reforms and structural changes in governance, administrative systems, and wider society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Global impacts of heat and water stress on food production and severe food insecurity

The economic commitment of climate change

The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

Introduction.

Agriculture predominantly depends on the climate and natural resources; thus, climate change decisively impacts agriculture. The FAO ( 2016 ) has noted that climate change has prolonged impacts on agriculture and food security. A 60% increase in global food demand will occur by 2050 against 2006 levels due to population increases and changes to food patterns, while climate change will continually impact global food systems. Although agriculture has an immense capacity to absorb carbon dioxide (CO 2 ), agriculture, forestry, and other land-use practices contributed to 24% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2010 (Tubiello et al., 2014 ). In 2015, entire food systems—including agriculture, changing land-use patterns in agriculture, food processing, supply chains and consumption—contributed to 34% of global GHG emissions (Crippa et al., 2021 ). In his special report to the UNHRC in 2014, the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food highlighted the drawbacks of current food security processes, their significant risks and GHG emissions. Thus, he proposed agroecological techniques and small-scale farming to promote food system sustainability, improve climate change resilience and enhance food sovereignty (Sage, 2014 ; De Schutter, 2014 ). These techniques include intercropping, agroforestry, crop and livestock diversification to promote natural nutrient recycling, natural farming practices and the minimisation of external inputs (De Schutter, 2014 ). Moreover, the ten elements of agroecology (i.e., diversity, co-creation and sharing of knowledge, synergies, efficiency, recycling, resilience, human and social values, culture and food traditions, responsible governance, and a circular and solidarity economy) put agroecology into practice (FAO, 2018 ).

Climate shocks and changes in weather patterns affect agriculture to a greater extent in Sri Lanka than in other countries. The country experienced its worst drought conditions in late 2016, while a 40% decline in paddy production occurred in early 2017. Afterwards, heavy rains in May 2017 further deteriorated food crop production. Moreover, 229,560 households were food insecure, with rain-fed farmers and agricultural labourers being the most affected (Coslet et al., 2017 ). In Sri Lanka, heavy rains, landslides and floods in May 2017 resulted in 246 deaths and the displacement of over 600,000 people, which ranked the island as the second-worst hit in the 2017 Global Climate Risk Index (Eckstein et al., 2019 ). Heat stress due to temperature increases and extreme rainfall anomalies are the two general climate change trends that adversely affect food security in Sri Lanka (Sathischandra et al., 2014 ). The severity of weather-related disasters in Sri Lanka is extreme since flash floods and prolonged droughts are much higher and more frequent than in other countries (IMF, 2018 ). In Sri Lanka, average annual losses from natural disasters between 1998 and 2012 were US$ 380 million, with losses due to flooding and cyclones being the most significant contributors (Siriwardana et al., 2018 ). Floods, landslides, droughts and storms accounted for 74% of the total disaster occurrences during the 1990–2018 period (UNDRR, 2019 ). Studies have claimed that such high climate variances were due to both La Niña and El Niño extremes (Sumathipala, 2014 ; Hapuarachchi and Jayawardena, 2015; Jayawardene et al., 2015 ; Abeysekera et al., 2019 ). Moreover, Sri Lanka is vulnerable to climate change impacts such as upsurges in temperature, changes in rainfall patterns, seawater rise and extreme weather events (Mani et al., 2018 ). Conversely, Sri Lanka’s hidden climate hotspots are at high risk from climate change impacts and are located around agricultural areas, with the North, North Central, Western and North Western provinces being the most adversely affected (The World Bank, 2018 ).

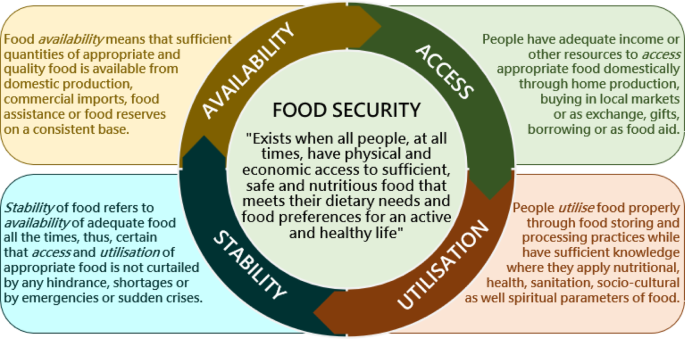

Food security has four dimensions: food availability, accessibility, utilisation and stability (FAO, 2006 ). As per the definition, ‘food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’ (World Food Summit, 1996 ; FAO, 2008 ). Figure 1 presents the four dimensions of food security in detail.

(As per its definition, food security has four dimensions ‘Availability, Accessibility, Utilisation and Stability’. Impediments in any of these dimensions would challenge food security at all levels, from person to global. Thus, Figure 1 demonstrates the interconnectedness of said four dimensions and details the definition of food security and each dimension).

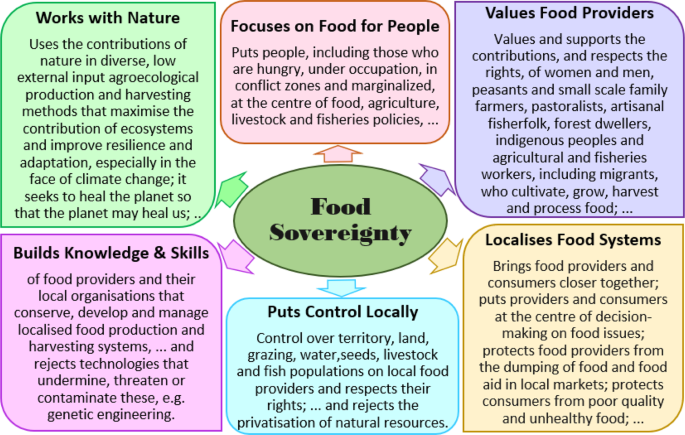

In contrast, food sovereignty ‘is the right of people to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. It puts those who produce, distribute, and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies rather than the demands of markets and corporations. It defends the interests and inclusion of the next generation…. It ensures that the rights to use and manage our lands, territories, waters, seeds, livestock and biodiversity are in the hands of those of us who produce food’ (Nyeleni, 2007a ). Accordingly, food sovereignty has six pillars (Nyeleni, 2007b ; La Via Campesina, 2018 ), which are presented in Fig. 2 .

(Food sovereignty is based on six pillars or approaches: Works with Nature, Focuses on food for people, Values food providers, Localises food systems, Puts control locally, and Builds knowledge and skills. Figure 2 here detailed these six pillars, thus, supports readers to grasp the food sovereignty concept quickly).

Globally, food sovereignty evolved as a solution to climate change impacts on food security, diminishing rights of local food producers and consumers, and increasing poverty, hunger and fragility of food systems (Wittman 2011 ; Chihambakwe et al., 2018 ). The obvious interdependence of climate change and agriculture establishes food security well in development discourse (Firdaus et al., 2018 ; Yadav et al., 2019 ; Tan et al., 2021 ). Despite food security having four dimensions, the focus has mainly been on food availability by increasing food production. As such, less focus has been given to food accessibility and utilisation (Capone et al., 2014 ; Stringer 2016 ; Firdaus et al., 2020 ). Moreover, the vast majority of people that depend on agriculture for their livelihood are adversely affected by hunger and malnutrition worldwide (FAO et al., 2018 ; Yadav et al., 2019 ). Food sovereignty aims to secure the right for people and countries to make independent decisions regarding their food systems without any external influences or deterrents (Levkoe et al., 2019 ; Patel, 2009 ; Wittman, 2011 ). This is vital since small-scale food producers represent 40–85% of food production, while 76% of the world’s poor lives in rural areas and depends on agriculture for their livelihood (FAO and IFAD, 2019 ; IFAD, 2014 ; United Nations, 2019 ).

We felt that authorities and policymakers in Sri Lanka may not adequately be informed of such global initiatives or are reluctant to shift from conventional agriculture to sustainable initiatives. For instance, Yatawara ( 2005 ) elaborated that ‘the agriculture sector has suffered from the absence of a clear and consistent agriculture strategy over the last decade’. Moreover, the draft Overarching Agricultural Policy of Sri Lanka prioritises conventional agriculture while promoting export-oriented agriculture (Ministry of Agriculture, 2019 ) instead of focusing on the country’s food security. Policies focused on food security should be a more significant concern in Sri Lanka, where over 80% of the population live in rural areas (Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 2019 ). Despite being the majority, rural communities have little influence over policymaking and lack sufficient knowledge regarding their right to food, land, water and other inputs, which could be demanded from the government (Foti and De Silva, 2010 ). Thus, it emphasises the significant impacts of climate change on food security, lives, livelihoods, and natural resources in Sri Lanka. Consequently, this study had the following aims: (1) Map the interrelation between climate change, food security and food systems; (2) Elaborate the ways that food sovereignty contributes to securing the rights of people and nature while also exploring agrifood activism and discourses on food security and food sovereignty; (3) Understand the extent to which these concepts are established in Sri Lankan development discourse while determining a way forward.

Methodology

This study applied a narrative literature review of carefully selected works published in academic journals, periodicals, books, policy documents and reputable agencies’ publications from 1996 to 2021. Only English-language works were included and reviewed. Based on our study objectives, we identified key search terms and databases to search for relevant articles. A total of 378 documents were identified through the initial database search process. Lists of papers were outputted from each search, and abstracts were read to assess their relevance. Using this method, 109 documents were identified and accessed. Each document was then read and analysed. This led to the identification of additional relevant references, and a further 71 relevant papers were identified and read. Reasons for removing documents during the screening and eligibility checking process included duplication, being published outside of the study period and not being relevant to the study focus. All of the papers considered in this review were retrieved through online databases such as Google Scholar, Elsevier, JSTOR, Springer, Taylor & Francis and Kopernio. Multiple search terms were used, including agriculture, agroecology, climate change, farmer movements, food security, food sovereignty, peasant movements, poverty, and sustainable development. The selected articles were assessed in two levels: (1) To grasp a more comprehensive global picture of climate change, food security and food sovereignty; (2) To assess the identified concepts and practices in the Sri Lankan context with the aim of applying them locally. Figure 3 presents an overview of the study process.

(This flow chart explains different stages of secondary data analysis, from defining study objectives to analysing the selected documents).

Additionally, we conducted in-depth interviews with social activists, the leaders of farmer organisations, agricultural practitioners, and experts currently involved in climate change, food security and food sovereignty. The eight participants who were involved in this study represent the purposive sample. Thus, the selected participants have unique information and comprehensive experience, facilitating these informants’ engagement (Valerio et al., 2016 ). The objectives of the in-depth interviews were to capture different stakeholders’ perspectives on several key concepts in this review, their importance and the changes required to make food security and food sovereignty a reality in Sri Lanka in the wake of climate change. The key concepts covered in interviews were food security, climate change, agroecology, sustainable development and food sovereignty. On average, the interviews lasted 45 min, and the questions were based on the informants’ expertise. Among the eight participants, five of them were male, and three were female. Their ages ranged from 35 to 65 years; they had 15 to 40 years of experience and were active in their professions. Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview protocol. The interview protocol was first developed in English and then translated to the Sinhalese Language as the participants are native Sinhalese. This study complies with ethical standards and guidelines of the institutional ethical committee on human experiments. Before the field data collection, a statement was presented to the participants detailing the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants and that the data will be used in scientific research and publications. With the prior consent of the participants, all the interviews were tape-recorded. The number of participants was limited to eight due to data saturation. The interview findings were restricted to the focus of this study (i.e., climate change, food security and food sovereignty) in the Sri Lankan context (Andrade, 2021 ).

Discussion of findings

This paper first reviews climate change and food security interconnectedness, focusing on poverty, hunger, and malnutrition. In this section, the paper focuses on climate change impacts on food security in Sri Lanka concerning recent climatic change and its impacts on food crop production. The following two sections assess the emergence and progression of food sovereignty in the global and Sri Lankan contexts. This section provides details on the emergence of food sovereignty, different approaches at the ground level, and international policy and decision-making platforms. Next, the study outlines various approaches to making food sovereignty a reality based on cases from different countries worldwide. The study concludes with concluding remarks that provide some policy and structural interventions to ensure food security and food sovereignty in Sri Lanka.

Climate change and food security: the reality in Sri Lanka

Although Sri Lanka is an agriculture-based country, contributions to national gross domestic product (GDP) from the agricultural sector declined sharply from 33.53% in 1974 to 7.24% in 2019, which is even lower than the global average 10.46%. However, the agricultural land area increased from 23,420 km 2 in 1991 to 27,400 km 2 in 2016. Notably, the agricultural sector’s employment percentage declined from 42.84 to 27.1% during the same period (The Global Economy.com, 2020 ). Sri Lanka produces approximately 80% of its food requirements locally, while wheat, sugar, fish and milk products account for 65% of total food imports (World Food Programme, 2017 ). Rice is nearly self-sufficient, while over 75% of the other food crops are produced locally. However, climatic changes challenge local food production and food security in Sri Lanka. In 2019, the country ranked 66th out of 113 countries in the Global Food Security Index 2019, with an overall score of 60.8%—a 1.2% improvement from 2018 (The Economist Intellgence Unit, 2019 ).

Sri Lanka has been experiencing drastic changes in rainfall, rain patterns, droughts and temperature, which poses challenges for agricultural productivity, livelihoods and food security (Coslet et al., 2017 ; Eckstein et al., 2019 ; Marambe et al., 2015 ). According to Ratnasiri et al. ( 2019 ), the increase in temperature adversely impacts rice production more than the rainfall variance under different climate change scenarios for Sri Lanka. Another study in Sri Lanka indicated that an increase in rainfall is beneficial across the country, yet temperature increases will adversely affect dry zone agriculture (Seo et al., 2005 ). Studies on Sri Lankan home gardens highlighted their benefits in food security, providing ecosystem services and being cost-effective and pro-poor (Landreth and Saito, 2014 ; Yapa, 2018 ; Mattsson et al., 2018 ). Moreover, home gardens are considered climate-resilient since they depend on strategies that maintain diversity (Weerahewa et al., 2012 ). Some studies stressed the negative impacts of climate change on agriculture, fisheries and livestock, thus underscoring the execution of adaptation strategies (Esham et al., 2018 ; Marambe et al., 2015 ). However, Menike and Keeragalaarachchi ( 2016 ) found that adaptation practices are mainly based on socio-economic, environmental and institutional factors and the economic structure.

Furthermore, the South Asia Policy and Research Institute ( 2017 ) raised concerns regarding malnutrition, disparities in malnutrition, micronutrient deficiencies, yield stagnation, food price fluctuations, income inequality, poor roads and inefficient food systems in Sri Lanka. Multiple issues related to poverty, land fragmentation and degradation, food safety and gaps in policy and programmatic responses jeopardise food security in Sri Lanka (APWLD, 2011 ; Siriwardana et al., 2018 ; Ratnasiri et al., 2019 ). Although absolute poverty has declined sharply due to social security systems, sectoral and regional disparities, pockets of poverty persist in Sri Lanka. For instance, although the National Poverty Headcount Index for 2016 was 4.1, it was 1.9, 4.3 and 8.8 for urban, rural and estate sectors, respectively (Department of Census and Statistics, 2017 ). The country has also been experiencing pockets of poverty with high regional poverty disparities (Herath, 2018 ). Nevertheless, achieving food and nutritional security is a significant concern due to poor nutritional knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP)—specifically among women in marginalised areas—which adversely affect household food security (Weerasekara et al., 2020 ). Moreover, Esham et al. ( 2018 ) emphasised the lack of research on the climate change impacts on food systems in Sri Lanka, including impacts on livestock and fisheries.

The fishery sector in Sri Lanka is also vulnerable to climate change impacts, coastal and marine resource exploitation, pollution and natural habitat destruction (Wickramasinghe, 2010 ). Notably, development trends focused on the maximum use of marine and coastal resources infringe on fishers’ rights (Amarasinghe and De Silva, 2018 ). Approximately 560,000 people are employed in the fisheries sector, which provides livelihoods for over 2.7 million people in coastal communities throughout Sri Lanka (NARA, 2018 ). Fishing practices and fish availability depend on weather patterns, making coastal fishing dependent on seasonal climate variance (Arunatilake et al., 2008 ). Climate change impacts, illegal fishing, inequalities, user conflicts, outdated policies, the overexploitation of resources and insufficient governance trigger vulnerabilities in the fishery sector (Sosai, 2015 ; The World Bank, 2017 ; Ibrahim, 2020 ). Since fish provides ~70% of the animal protein intake in Sri Lanka and the coastal belt hosts approximately 25% of the population and 70% of the hotels and industries (Ministry of Fisheries, 2007 ), any challenges in the fishery sector will jeopardise food security in Sri Lanka.

Table 1 provides excerpts from the in-depth qualitative interviews. The identified issues are specifically relevant to small-scale food producers. The participants explained climate change impacts in detail while emphasising their adverse impacts on rural communities, peasants and agricultural workers, small-scale fishers, and poor, marginalised and indigenous communities. Some informants felt that climate change is a consequence of neoliberal development drive. Recent efforts have resulted in increasing food crop production via commercial agriculture practices that threaten the food security of ordinary people while making them the victims of climate change impacts.

Esham and Garforth ( 2013 ) found that climate change adaptation strategies lacked connections with national development policies in Sri Lanka. Therefore, they recommended further studies on adaptation practices suitable for smallholder farmers and methods of mainstreaming climate change adaptation into national development policies while finding ways to implement them at the national, regional and local levels. Moreover, the Institute of Policy Studies ( 2018 ) emphasised the dearth of policy and strategic interventions in Sri Lanka addressing food insecurity and malnutrition, specifically in agriculture and climate change impacts on agriculture and food systems.

Table 2 presents some of the climate change adaptation practices in Sri Lanka noted during the in-depth interviews. These practices are prevalent among small-scale farmers and rural communities attached to farmer movements and societies. Simultaneously, agricultural extension services also promote certain climate change adaptation practices.

Approximately 25% of the Sri Lankan population lives on US$ 2.50 per day and is the most vulnerable to climate and economic shocks. Thus, establishing the food and nutrition security of 4.6 million malnourished people while providing safe and high-quality food for 2.4 million additional people by 2050 represents a significant challenge in Sri Lanka (World Food Programme, 2017 ). Local food production in Sri Lanka accounts for approximately 85% of domestic food requirements (Institute of Policy Studies, 2018 ), while the livelihoods of approximately 28% of the population depend on agriculture. The adverse impacts of climate change on agriculture will challenge the entire population’s food security and the livelihoods of the vast majority of people (Climate Change Secretariat, 2016 ). Moreover, the living standards of approximately 90% of the population living in areas projected as having severe and moderate hotspots will decline by 7.0% by 2050 under the carbon-intensive scenario (The World Bank, 2018 ). Therefore, despite focusing on resilient food production, Sri Lanka requires a holistic approach to its entire agricultural system (Esham et al., 2018 ). Accordingly, we assess food sovereignty in the next section with the support of different studies worldwide.

Food sovereignty: a global perspective

The 1996 World Food Summit in Rome declared that the goal set during the World Food Conference 1974 to eradicate hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity within a decade was not achieved, mainly due to policy and funding failures (FAO, 1996 ; World Food Summit, 1996 ). While over 800 million people worldwide lack sufficient food, the World Food Summit of 1996 pledged to reduce the number of malnourished people globally by half by 2015. The Rome Declaration on World Food Security emphasised sustainable food security and the eradication of hunger, poverty and malnutrition (Shaw and Clay, 1998 ). However, many studies claim that climate change challenges all dimensions of food security (FAO et al., 2018 ; Firdaus et al., 2019 ; Islam and Wong, 2017 ; Schmidhuber and Tubiello, 2007 ; Wheeler and von Braun 2013 ). Stringer ( 2016 ) claimed that only food availability has succeeded since the world produces enough food to feed everyone. For instance, global food production has increased by 2.5 times over the last 40 years (Greenpeace International, 2009 ); however, hunger, poverty, and malnutrition increased drastically. Globally, approximately 821 million people were undernourished in 2017 compared to 804 million in 2016, while food insecurity has increased steadily in Asia, Africa and Latin America (FAO et al., 2018 ).

People who depend on family farming are the primary targets and contributors to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the 2030 Agenda of the United Nations (UN) (FAO and IFAD, 2019 ). However, such people have been considered as obstacles to development than integral parts of the solution (FAO, 2014a , 2014b ). Conversely, progress indicators for achieving the SDGs reveal that 690 million people were hungry, while approximately 750 million people were exposed to severe food insecurity in 2019 (FAO et al., 2020 ). Notably, healthy diets would reduce 97% of health costs and 41 to 74% of the social costs of GHG emissions by 2030. Without overall changes in the current global food systems, the burning issues of poverty, hunger, malnourishment, climate change, and other socio-political and environmental issues will not be resolved. Moreover, the COVID 19 pandemic will have a lasting negative impact on overall progress towards achieving the SDGs (FAO et al., 2020 ).

The food sovereignty concept brought much attention in public debates during the World Food Summit of 1996 and afterwards since it challenges the neoliberal development policies that are driving the world into poverty, hunger and food insecurity (Gordillo and Jeronimo, 2013 ; Levkoe et al., 2019 ; Shaw and Clay, 1998 ; Windfuhr and Jonsen, 2005 ). Although numerous organisations have taken the food sovereignty policy framework forward, La Via Campesina (LVC) originally developed the concept in the early 1990s (La Via Campesina, 2003; Windfuhr and Jonsen, 2005 ; Wittman, 2011 ). LVC is a transnational network organisation of over 200 million peasants and farmers, small-scale food producers, landless people, agricultural workers, women, young farmers and indigenous people from 182 social organisations in 81 countries worldwide (Walsh-Dilley et al., 2016 ). LVC emerged from the agrarian movements in Latin America and Europe and established itself as a global network of peasant movements in 1993 in response to the Uruguay Round of GATT (McKeon, 2015 ). LVC gradually converged into a transnational social movement and has merged various cultures, epistemologies and diversities (Rosset and Martínez-Torres, 2014 ). LVC and its wider networks demanded the inclusion of a food sovereignty framework into global food policymaking and advocated with relevant organisations such as the WTO, UN General Assembly and FAO by participating in various processes, forums and discussions (La Via Campesina, 2003; Brem-Wilson, 2015 ).

Food sovereignty challenges current global food systems and promotes the creation of new food systems that protect the rights of small-scale food producers, food providers and consumers regarding their choices (Nyeleni, 2007a ; Walsh-Dilley et al., 2016 ). The right to food is an internationally recognised and legally enforceable human right that is considered an individual right. In contrast, food sovereignty advocates the right to food as a people’s right (Cotula et al., 2008 ). To realise the right to food, individuals should have access to enough food that meets their dietary needs. Food availability refers to a country’s available food stock to meet domestic demand, whether locally produced or imported (Firdaus et al., 2019 ). The right to food was first affirmed in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, followed by several international treaties and instruments (Cotula et al., 2008 ). Despite this, the conventional food security approach does not establish the right to food emphasised in the concept of food sovereignty (Cotula et al., 2008 ; Gordillo and Jeronimo, 2013 ).

On the other hand, food sovereignty supports the rights of individuals, communities, people and countries to produce their food domestically. Since it emphasises land and natural resources access, it has evolved as a collective right with specific policy orientations (Claeys, 2015 ; Patel, 2009 ; Walsh-Dilley et al., 2016 ). The food sovereignty policy framework focuses on providing food for people by framing it as the right to food. It promotes and supports the values and contributions of food and respects rights while bringing food providers and consumers together in decision-making processes (Cotula et al., 2008 ; Nyeleni, 2007b ). It also underscores locally controlled food production, distribution and consumption patterns, builds on local food providers’ knowledge and skills, sustains such wisdom and works in harmony with nature while preserving ecosystem functions (Nyeleni, 2007b ; Rosset and Martínez-Torres, 2014 ). Table 3 provides a detailed comparative analysis of conventional agriculture and food sovereignty approaches on different issues.

However, Patel ( 2009 ) claimed that the egalitarian view of food sovereignty is the central issue in functional democracy and resource distribution since it limits conversations on food policies. Thus, the rights emphasised in food sovereignty must be met for everyone in a meaningful way. However, this raises the question of how this aim could be achieved. Sage ( 2014 ) explained the UN Special Rapporteur’s involvement in the right to food constituting food sovereignty, agroecology and small-scale farming in high-profile policy forums. Moreover, several studies have explained how food sovereignty campaigns utilise UN systems while building alliances and social movements to amplify the voice of the voiceless and promote food-producing constituencies and other stakeholders in decision-making processes (Brem-Wilson, 2015 ; Desmarais et al., 2014 ; Edelman et al., 2014 ; Plahe et al., 2017 ; Walsh-Dilley et al., 2016 ). Several countries have made food sovereignty a constitutional and legal right in local legislature and policies while creating right-based standards in high-level policy forums, including the UN (Brem-Wilson, 2015 ; Claeys, 2015 ; Gordillo and Jeronimo, 2013 ; McKay et al., 2014 ). The above assessment provides a solid foundation to apply food sovereignty and assess to what extent it was established in the Sri Lankan context.

Food sovereignty in Sri Lanka

Climate change impacts food systems, prevailing poverty, hunger and food insecurity, food rights, neoliberal economic policies and development displacements in Sri Lanka, which has led to social movements towards food sovereignty. Although uncertainties remain regarding who introduced the food sovereignty concept into Sri Lanka, one could strongly claim that it was Movement for National Land and Agricultural Reform (MONLAR). As a founding member of LVC and a leader in LVC South Asia (La Via Campesina, 2020 ), MONLAR has applied the food sovereignty framework and supported agrarian struggles in Sri Lanka. MONLAR advocates for agricultural and land policy reforms, ecological agriculture, land to the landless, the protection of natural resources, seed rights and food sovereignty while participating in high-level policy forums locally and internationally (Fernando, 2013 ). The late Sarath Fernando, the founder of MONLAR, was a true believer in nature’s capacity to regenerate itself, which was later termed as ‘regenerative agriculture’. He reframed agroecology with nature’s capacity to regenerate and applied the same natural principles in regenerative agriculture to promote diversity, natural functions and interconnectedness in farmland (Fernando, 2008 ; 2014 ).

In the present study, the participants in the in-depth interviews first learned about food sovereignty through their affiliations with MONLAR and confirmed that MONLAR had introduced food sovereignty into Sri Lanka (Box 1 ). They are long-standing activists and professionals in the development and education sectors related to agriculture, people’s development rights, and environmental conservation. The views gathered from the in-depth interviews indicate that MONLAR and its peasant movement have introduced and promoted food sovereignty and agroecological practices in Sri Lanka.

Ecological agriculture applies ecology to agricultural fields while emphasising agricultural biodiversity conservation (Delgado, 2008 ), which integrates social and ecological principles in agriculture to enhance and promote sustainable food systems (FAO, 2018 ). This process maximises natural functions in farmlands where soil, water, weather patterns, plants, microbes, insects, animals and humans work together to improve biodiversity and food production while tackling climate change (Ching, 2018 ; Ortega-Espes and Finch, 2018 ; Schaller, 2013 ). Since nature has a great capacity to regenerate, ecological agriculture enhances nature’s capacity to provide food. Agroecology goes beyond the farmland, having broader interactions and interdependence with ten elements of agroecology. They function as an analytical tool or guiding principles that help policymakers, agroecological practitioners and other stakeholders to plan, implement and evaluate the agroecological transition process (FAO 2018 ; Barrios et al., 2020 ).

MONLAR uses ecological agriculture as a core strategy of small-scale food producers’ struggle. For instance, Van Daele ( 2013 ) described that ‘while proposing the alternatives of regenerative agriculture, MONLAR frames it in terms of reducing input prices, providing equitable access to markets and achieving food sovereignty in the face of World Trade Organization-induced trade liberalisation’. To address agricultural and environmental crises, MONLAR proposed strengthening the rural agrarian economy. This requires new approaches and methodologies, promotes ecological agriculture, utilises local knowledge and experience, promotes local food production and enables policies (Fernando, 2007 ). Predominantly, MONLAR’s struggle is twofold: (1) Finding urgent solutions for the burning issues of the poor, landless, marginalised and underprivileged; (2) Being involved in pro-poor public policy reforms on land, agriculture, fisheries, water, trade and the environment. The lasting experience of farmer organisations, peoples’ movements and communities demonstrate the effectiveness of ecological agriculture to overcome hunger, poverty and health issues while healing nature against the ecological destruction caused by conventional chemical farming (Fernando, 2014 ).

For instance, zero budget natural farming (ZBNF) in India brings millions of farming families out of poverty, indebtedness and agrarian crises of the neoliberal economy. Notably, ZBNF is not merely an agroecological farming practice but a peasant social movement for justice and change. ZBNF reduces the direct costs of farming, improves the lives and livelihoods of farming families and changes the agricultural practices while being centred in agriculture policy planning and extension services in some state governments in India (Bharucha et al., 2020 ; Khadse et al., 2018 ; Tripathi et al., 2018 ). In Cuba, Mexico, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador, Brazil, India and the Latin American region, agroecology and food sovereignty have become integral components of overall food and agriculture policies, extension services and sustainability approaches. The development rights of the people and stability of food systems are grounded as participatory, transformative and transdisciplinary actions (Altieri and Toledo, 2011 ; Cacho et al., 2018 ; Gliessman, 2013 ; McKay et al., 2014 ; Reardon and Perez, 2010 ). In Ecuador, food sovereignty and agroecology have become a government obligation and a strategic goal as per the country’s constitutional provisions and food sovereignty laws (Giunta, 2014 ; Intriago et al., 2017 ). However, some impediments in government policies that go against the realities remain.

In Sri Lanka, academic studies related to agroecology have extensively focused on agroforestry, home gardens and traditional agricultural practices. Home gardens are a mixture of crops, plantations, livestock and occasionally fish (Pushpakumara et al., 2012 ; Yapa, 2018 ; Haan et al., 2020 ). They provide various benefits such as food and nutritional security, firewood and timber, household income and herbal medicines while promoting ecosystem services such as biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration, soil and water conservation and resilience to climate change (Landreth and Saito, 2014 ; Mattsson et al., 2018 ; Melvani et al., 2020 ; Weerahewa et al., 2012 ). The issues surrounding home gardens emphasise a poor understanding of climate change adaptation and mitigation, less stakeholder participation in policy processes, and information and empirical study gaps. Home gardens fully follow agroecological practices with a mixture of chemical and non-chemical agriculture. Studies on food sovereignty and agroecology have noted MONLAR’s involvement in diverse peasant networks (Fernando, 2008 ); however, such efforts have not been adequately documented.

Van Daele ( 2013 ) stated that ‘MONLAR proposes a shift towards non-chemical agriculture, which restores the capacity of the soil and nature to regenerate itself’. In Sarath Fernando’s words, ‘when the soil is provided with organic manure or compost, it can recover its capacity to become an ‘eternal spring of gifts’’. He argues that regenerative agriculture restores ecological relations, making farming viable again and accessible for everyone. The current neoliberal development model in Sri Lanka has failed since nearly all human development indicators provide a daunting picture of the country. Thus, it must move to small-scale sustainable ecological agriculture, developing a cordial relationship between nature and society (Fernando, 2012 , 2013 ). Ecological agriculture promotes soil fertility, enhances soil water and moisture content, promotes integrated pest management, uses organic matter, promotes microbial activity, prevents soil erosion and environmental degradation, and reduces carbon footprints (Ching, 2018 ; Ortega-Espes and Finch, 2018 ; Schaller, 2013 ). Therefore, Fernando ( 2014 ) proposed shifting from conventional to ecological agriculture for economic enhancement, poverty and hunger reduction, and uplifting social justice. Since food sovereignty and ecological agriculture have provided promising results worldwide (Bharucha et al., 2020 ; Chappell et al., 2013 ; Intriago et al., 2017 ; McKay et al., 2014 ; Wittman, 2011 ), it is appropriate for Sri Lanka to take progressive steps towards applying these concepts.

Table 4 provides various reasons to promote food sovereignty in Sri Lanka and some possible strategies and policy interventions based on in-depth interviews with informants. These underscore the importance of introducing a new national agricultural policy and development framework for the agricultural sector that promotes sustainable development practices. With this understanding, the next section of the article will look at how food sovereignty has been placed in different parts of the world, the pros and cons of policy reforms and the realities of putting food sovereignty into practice.

Box 1. Expert views on promoting food sovereignty in Sri Lanka

Informant 1 (Development Practitioner/Social Researcher): I received an opportunity to work with MONLAR and its founder Sarath Fernando since the early 1990s, where I learned about food security and the need to go beyond it with food sovereignty to find solutions for the global food crisis and rural poverty. Since then, I began to work for food sovereignty.

Informant 2 (President-National Farmer Movement): As a social activist, I have known the MONLAR founding members since the 1970s. We have been learning about and practising organic farming methods since the year 2000 as an alternative to chemical agriculture. The concept was further improved beyond organic to ecological agriculture and food sovereignty with a broader socio-economic, political and environmental vision, as envisioned by La Via Campesina and locally by MONLAR.

Informant 3 (National Coordinator-MONLAR): In 2003, I joined MONLAR’s youth movement, where I first heard about food sovereignty. As a founding member of La Via Campesina, MONLAR introduced the food sovereignty concept into Sri Lanka. We promote and apply the food sovereignty concept and its principles and practices locally, regionally, and globally.

Informant 4 (Professor-University of Sabaragamuwa): As a professor of ecological agriculture, I was fascinated with the concept of food sovereignty while listening to a lecture given by the late Sarath Fernando of MONLAR in 2007. Since then, I have tried to complement the concepts of ecological agriculture and food sovereignty while providing thorough knowledge to my university students on these subjects.

Informant 5 (National Coordinator-Uva-Wellassa Women Organisation): I first became involved in farmers’ rights and protecting nature in the early 1980s during the Sri Lankan government’s efforts to privatise vast areas of farming and forest lands into a sugarcane factory. Although national policies have not promoted food sovereignty since then, it has become a familiar concept widely discussed locally and globally.

Informant 6 (President-Ecological Agricultural Producers and Entrepreneurs Cooperative Society): I first learned about food sovereignty in the early 2000s while working with mothers and children. If I compare it with the past, food sovereignty is now widespread in public discussions, policy forums and civil rights movements.

Informant 7 (National Coordinator-Savisthri National Women’s Movement): I began to work on food security and sovereignty in the late 1990s. Although food sovereignty is a popular concept discussed in different forums, it has not been a genuine interest of policy and decision-makers.

Informant 8 (Field Coordinator-Bio Foods Pvt. Ltd.): I heard about food sovereignty in 2000 and have received a broader understanding of it from MONLAR since 2001. This concept is prevalent in America, Europe and Latin America; yet, less popular in Asia, including Sri Lanka. Thus, we should move to food sovereignty to safeguard our rights, cultural diversity, health, biodiversity and nature.

Source: In-depth interviews with experts.

Food sovereignty: a case for change

Many countries worldwide are increasingly vulnerable to climate change and natural disasters that can destroy decades of development and cause harm to the natural environment, thereby increasing poverty, hunger, conflicts, and inequality since vulnerable people typically depend on nature for their livelihoods (The World Bank and UN, 2010; Thomas, 2017 ). Concerning crop adaptations to climate change, the effect of CO 2 concentration could be beneficial. With increasing latitude, the adverse effects of increased temperature are reduced, which increased rice crops by 24% under the crop simulation model in East Asia’s monsoon climates (Kim et al., 2013 ). However, climate change negatively impacts crops such as rice, which depends on specific agronomic conditions (Fahad et al., 2019 ). Increased CO 2 levels in the atmosphere will substantially reduce the iron, zinc and protein content of rice, wheat, soybeans and field peas while increasing the carbohydrates (Myers et al., 2014 ; Al‐Hadeethi et al., 2019 ). Despite this, agriculture decisively contributes to climate change. Entire food systems, including production, distribution and consumption, account for approximately 20% of global GHG emissions. Additionally, 6–17% of GHG emissions stem from global land-use changes related to agriculture (Greenpeace International, 2009 ). As one of the primary GHG producers, agriculture should apply sound abatement policies and practices—especially pro-poor mitigation measures—while modifying agricultural practices and productions to meet the growing global food demand.

Recent progress assessments on attaining the SDGs indicate that the world will not achieve the goals by 2030 unless significant changes occur (Moyer and Hedden, 2020 ). The SDGs are interconnected in their nature. Concerning climate change and food security, the key SDGs are Goal 1 (No Poverty), Goal 2 (Zero Hunger) and Goal 13 (Climate Action). Goal 1 focuses on ending global poverty in all forms by ensuring sustainable livelihood and addressing various forms of discrimination and exclusions in development decision-making. Goal 2 focuses on eradicating hunger, malnutrition and achieving food security by promoting sustainable agriculture, changing food production systems, and protecting the environment. Goal 13 relates to taking immediate actions to tackle climate change impacts by responding nationally and globally (United Nations, 2015 ; Herath, 2018 ; Moyer and Hedden, 2020 ). After decades of struggling to combat poverty, food insecurity, hunger, malnutrition and climate change, the entire world is at a crossroads to take firm decisions on whether to continue our efforts with food security approaches or move on to food sovereignty. The obvious option is to move on to food sovereignty since dominant neoliberal agriculture approaches, and corporate food chains have failed to feed the world. Hence, it is essential to find ways to make food sovereignty a reality by switching from conventional to sustainable agriculture. However, this may require significant changes in policy decisions and agricultural practices.

Agroecology promotes farming without significant investments, utilises family labour, creates partnerships with consumers, and eliminates factors affecting food insecurity, hunger, poverty and disasters while ensuring food sovereignty. ZBNF in India is one of the best cases for justifying this claim. Khadse et al. ( 2018 ) elaborated on how ZBNF developed as a social movement in Karnataka, India, by addressing the indebtedness and suicides of peasants and farmers. The ZBNF movement goes beyond the technical aspects of agroecological farming by applying social aspects such as networking, movement building, setting up local markets, advocating for public policies, organising stakeholders at different levels, leadership building, and pedagogical processes and discourses. In Andhra Pradesh, India, ZBNF drastically reduced farming costs while producing high yields with non-chemical inputs, which led the state government to initiate ZBNF among all 6 million farmers in the state. This case signifies the importance of policy formation, financing and institutional support, capacity building and extension, farmer-centred development initiatives, learning ecosystems and networking (Bharucha et al., 2020 ). ZBNF widely contributes to achieving the SDGs in India. The massive-scale ZBNF programme in Andhra Pradesh has already experienced progress related to all SDGs and approximately 25% of the relevant targets (Tripathi et al., 2018 ).

By assessing the key drivers and multidimensional process of scaling up agroecological movements in Central America, Cuba, Mexico, Brazil and India, Cacho et al. ( 2018 ) identified eight key drivers: (i) catch a crisis that requires alternatives, (ii) establish social organisations and social process, (iii) progressive learning processes, (iv) effective agroecological practices, (v) mobilising discourses, (vi) established external allies, (vii) favourable markets and (viii) favourable policies. Accordingly, crises in society define the social process drivers while social organisations bring people together, and social processes promote sharing and learning among people. Concise and compelling agroecological processes help farmers practice and replicate them, which makes these processes easy to teach and learn. Concise and well-framed discourses promote people to support and practice them while motivating them to stand against the neoliberal agricultural model. External allies and stakeholders bring many resources to scale up the process by playing critical roles and amplifying the process. As a strategic approach, alternative market systems transform the food system and promote agroecological food, influencing public policies. Enacting relevant public policies and supportive political systems helps establish and scale up agroecology while institutionalising the entire process.

Food sovereignty is a concept of action’ that emerged from transnational peasant movements and offered new visions and prospects for resolving the most pressing issues of our time. It is above the right to food and emerged as a reaction to food security, neoliberal industrial agriculture and corporate food systems (La Via Campesina, 2018 ). Food sovereignty is a revolutionary approach capable of preventing food systems, environments and societies from totally collapsing. Conventional agriculture and the agro-industrial approach could not eradicate global hunger, malnutrition and poverty. Indeed, conventional agriculture is one of the significant contributors to global warming and climate change. Conversely, food sovereignty relates to peoples’ and countries’ rights to decide on and produce their food, safeguard nature and promote ecosystem services (La Via Campesina, 2003).

Since the food sovereignty concept was presented at the World Food Summit in 1996, it influenced propaganda, debates and discussions in many international forums, including the UN. Such involvement was instrumental in developing several UN guidelines (e.g., the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas). The Nyeleni Forum and Nyeleni Declaration on Food Sovereignty are critical milestones in bringing food sovereignty to the international level. This has led some countries to include food sovereignty in their constitutions. Since Ecuador first constitutionalised food sovereignty in 2008, Senegal, Bolivia, Mali, Nepal, Egypt and Venezuela have followed. Moreover, countries such as Argentina, Brazil, Nicaragua, Uruguay, Mexico, Colombia, Honduras and Guatemala have legally recognised food security, food sovereignty and the right to food. Such constitutional, legal and institutional recognition underscores the credibility and validity of food sovereignty approaches while providing a boost for a paradigm shift on a global scale.

By assessing the state’s role in food sovereignty in three Latin American countries (i.e., Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela), McKay et al. ( 2014 ) underscored state-society relations in terms of development approaches, the redistribution of power over controlling food systems, resources and the class struggle. However, they noted that food sovereignty in said countries limits the way states recognise it, which has resulted in a reduction in pro-poor initiatives in some situations. During the new constitutional drafting process in Ecuador in 2007, the assembly diluted the food sovereignty proposal of social movements by limiting peasants’ participation to a bureaucratic ‘council’ and removing land and land reform provisions. Even with such impediments, food sovereignty involvement promotes participatory decision-making at local levels, which sets the groundwork to achieve food sovereignty in the long run.

Climate change impacts on food systems are complex, yet impacts on agriculture production, incomes, food prices, safety, quality and food delivery are evident (Vermeulen, Campbell, and Ingram, 2012 ). Low-income food producers and consumers would face the adverse impacts of climate change. Thus, modern agriculture and food systems should go beyond the farm gate to rural communities to attain new food systems, while farms should be designed using ecological principles where the place, people and species inhabit spaces together (Francis et al., 2003 ; Gliessman, 2013 ; Cacho et al., 2018 ). This very idea views sustainability as the key to addressing issues surrounding agriculture and food systems. Therefore, ensuring sustainability as the fifth dimension of food security assessments is the way forward. Otherwise, current policies and interventions could intensify future food insecurity (Berry et al., 2015 ). Hence, it is essential to assess sustainability in detail. Nonetheless, persisting Poverty and food insecurity challenge the current food production and distribution systems (Windfuhr and Jonsen, 2005 ). Therefore, food security, nutritional security and food sovereignty should be considered together within the framework of the right to food (Gordillo and Jeronimo, 2013 ).

Pimbert ( 2010 ) claims that ‘existing decision-making and policy processes that are based on models of representative democracy are inadequate for transformation towards food sovereignty’. Therefore, it requires establishing a direct democratic system in which citizens can exercise their rights related to governance setting at local, regional and national levels. Food sovereignty is a socio-political solution to the global food system crisis that requires the awareness and actions of all stakeholders. Moreover, it requires structural changes in the global economic order to end global hunger by transforming the global food system. Resolving the looming issues of climate change and food security while moving towards food sovereignty requires all countries worldwide to take immediate and accelerated actions and develop partnerships among governments and relevant stakeholders at all levels. Therefore, this requires comprehensive and radical changes in government structures, international trade and policies, organisations, and bureaucratic and global systems.

Concluding remarks

Sri Lanka is predominantly an agriculture-based country, with over 80% of its food producers being small-scale farmers. Thus, promoting food sovereignty and applying agroecological practices in agriculture, fisheries and livestock farming are viable and sustainable practices to combat ongoing massive-scale agro-industrial approaches. In Sri Lanka, food security extensively depends on agriculture, fisheries and livestock production. However, government policies are far more favourable towards the industry and service sectors. Therefore, the agricultural sector’s share in national accounts has been declining sharply. New development projects have resulted in tremendous adversities for natural resources while also creating labour shortages in agriculture. A holistic approach to food security and sustainability is paramount to make the agricultural sector productive and sustainable. It also requires targeted interventions in marginalised and vulnerable communities, regional agricultural development programmes, and employment opportunities to tackle malnutrition, poverty and hunger. Realising the right to food requires safeguarding the rights of small-scale food producers, local distributors and consumers to decide on what they produce, share and eat. This approach should be brought to the regional and national levels by defining and designing a local production-oriented food and agricultural system that forms an integral part of the country’s agricultural policy framework.

Achieving food sovereignty in Sri Lanka and many other countries have become the focus of peasant development and social movements. Owing to the current development drive, profit-oriented agro-industries and different priorities of governments, greater possibilities for food sovereignty and agroecology have been sidelined. In Sri Lanka, few studies have been conducted on agroecology and food sovereignty, while studies on climate change and food security are limited to sectoral rather than holistic approaches. Therefore, academics should initiate research and publish scientific articles on food sovereignty, agroecology, small-scale food producers (i.e., agricultural workers, small-scale fishers, pastoralists and landless people), local food distributors and consumers. The emergence and development of peasant movements, local seed banks, traditional seed and planting material conservation, natural farming systems, and peasant and social movements in lobbying, advocacy, policy and decision-making processes also require much attention from academics and social researchers. Overall, suppose we aim to make this world sustainable and liveable over the long term by resolving food insecurity, hunger and poverty while addressing climate change. In that case, we should recognise, secure and promote the rights of small-scale food producers, revamp food systems and sustain ecosystem services by promoting agroecological principles and food sovereignty.

Data availability

All secondary data analysed and cited in this article are available in the public domain, while the primary datasets analysed during the study are not publicly available due to ethical considerations but may be provided upon an appropriate request to the corresponding author.

Abeysekera AB, Punyawardena BVR, Marambe B et al. (2019) Effect of El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events on inter-seasonal variability of rainfall in wet and intermediate zones of Sri Lanka. Trop Agric 167:14–27

Google Scholar

Al‐Hadeethi I, Li Y, Odhafa AKH et al. (2019) Assessment of grain quality in terms of functional group response to elevated [CO 2], water, and nitrogen using a meta‐analysis: grain protein, zinc, and iron under future climate. Ecol Evol 9:7425–7437. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.5210

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Altieri MA, Toledo VM (2011) The agroecological revolution in Latin America: rescuing nature, ensuring food sovereignty and empowering peasants. J Peasant Stud 38:587–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2011.582947

Article Google Scholar

Amarasinghe O, De Silva N (2018) Aiming for holistic management. SAMUDRA Issue no. 80. International Collective in Support of Fishworkers

Andrade C (2021) The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian J Psychol Med 43:86–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620977000

Article PubMed Google Scholar

APWLD (2011) Climate justice briefs: rural women’s adaptation strategies, Sri Lanka. Asia Pacific Forum for Women Law and Development, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Arunatilake N, Gunawardena A, Marawila D et al. (2008) Analysis of the fisheries sector in Sri Lanka: guided case studies for value chain development in conflict-affected environments. United States Agency for International Development, Washington, DC

Barrios E, Gemmill-Herren B, Bicksler A et al. (2020) The 10 Elements of Agroecology: enabling transitions towards sustainable agriculture and food systems through visual narratives. Ecosyst People 16:230–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2020.1808705

Berry EM, Dernini S, Burlingame B et al. (2015) Food security and sustainability: can one exist without the other? Public Health Nutr 18:2293–2302. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001500021X

Bharucha ZP, Mitjans SB, Pretty J (2020) Towards redesign at scale through zero budget natural farming in Andhra Pradesh, India*. Int J Agric Sustain 18:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2019.1694465

Brem-Wilson J (2015) Towards food sovereignty: interrogating peasant voice in the United Nations Committee on World Food Security. J Peasant Stud 42:73–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.968143

Cacho MMYTG, Giraldo OF, Aldasoro M et al. (2018) Bringing agroecology to scale: key drivers and emblematic cases. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst 42:637–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2018.1443313

Capone R, El Bilali H, Debs P et al. (2014) Food system sustainability and food security: connecting the dots. J Food Secur 2:13–22. https://doi.org/10.12691/jfs-2-1-2

Central Bank of Sri Lanka (2019) Economic and social statistics of Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka

Chappell MJ, Wittman H, Bacon CM, et al (2013) Food sovereignty: an alternative paradigm for poverty reduction and biodiversity conservation in Latin America. F1000Research 2: https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.2-235.v1

Chihambakwe M, Mafongoya P, Jiri O (2018) Urban and peri-urban agriculture as a pathway to food security: a review mapping the use of food sovereignty. Challenges 10:6. https://doi.org/10.3390/challe10010006

Ching LL (2018) Agroecology for sustainable food systems. Third World Network, Penang, Malaysia

Claeys P (2015) Food sovereignty and the recognition of new rights for peasants at the UN: a critical overview of la via campesina’s rights claims over the last 20 years. Globalizations 12:452–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2014.957929

Climate Change Secretariat (2016) National adaptation plan for climate change impacts in Sri Lanka: 2016–2025. Colombo, Sri Lanka

Coslet C, Goodbody S, Guccione C (2017) Special report: FAO/WFP crop and food security assessment mission to Sri Lanka. FAO and WFP, Rome, Italy

Cotula L, Djire M, Tanga RW (2008) The right to food and access to natural resources. FAO, Rome, Italy

Crippa M, Solazzo E, Guizzardi D et al. (2021) Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nat Food 2:198–209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9

Van Daele W (2013) The political economy of desire in ritual and activism in Sri Lanka. In: Carbonnier G, Kartas M, Silva KT (eds) International development policy: religion and development. Palgrave Macmillan, UK, London, pp. 159–173

Chapter Google Scholar

Delgado A (2008) Opening up for participation in agro-biodiversity conservation: the expert-lay interplay in a Brazilian social movement. J Agric Environ Ethics 21:559–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-008-9117-6

Department of Census and Statistics (2017) Poverty indicators household income and expenditure survey-2016. Colombo, Sri Lanka

Desmarais AA, Rivera-Ferre MG, Gasco B (2014) Building alliances for food sovereignty: La Vía Campesina, NGOs, and social movements. In: Research in rural sociology and development. pp. 89–110

Eckstein D, Hutfils M-L, Winges M (2019) Global climate change index 2019: who suffers most from extreme whether events? Germanwatch, Bonn, Germany

Edelman M, Weis T, Baviskar A et al. (2014) Introduction: critical perspectives on food sovereignty. J Peasant Stud 41:911–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.963568

Esham M, Garforth C (2013) Climate change and agricultural adaptation in Sri Lanka: a review. Clim Dev 5:66–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2012.762333

Esham M, Jacobs B, Rosairo HSR, Siddighi BB (2018) Climate change and food security: a Sri Lankan perspective. Environ Dev Sustain 20:1017–1036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-9945-5

Fahad S, Adnan M, Noor M, et al (2019) Major constraints for global rice production. In: Hasanuzzaman M, Fujita M, Nahar K, Biswas JK (eds) Advances in rice research for abiotic stress tolerance. Elsevier, pp. 1–22

FAO (2016) The state of food and agriculture: climate change, agriculture and food security. FAO of UN, Rome, Italy

FAO (2018) The 10 elements of agroecology: guiding the transition to sustainable food and agricultural systems. FAO of UN, Rome, Italy

FAO (2006) Food security: policy brief. FAO of UN, Rome, Italy

FAO (2008) Climate change and food security: a framework document. FAO of UN, Rome, Italy

FAO (2014a) The state of food and agriculture: innovation in family farming. FAO of UN, Rome, Italy

FAO (1996) The World Food Summit 1996. http://www.fao.org/wfs/ . Accessed 12 Jan 2021

FAO (2014b) The right to food: past commitment, current obligation, further action for the future. FAO of UN, Rome, Italy

FAO and IFAD (2019) United nations decade of family farming 2019-2028: global action plan. FAO and IFAD, Rome, Italy

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF. et al. (2018) Food security and nutrition in the world: building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. FAO of UN, Rome, Italy

FAO, IFAD, UNISEF. et al. (2020) The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020: transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. FAO of UN, Rome, Italy

Fernando S (2013) Who should own and control land. MONLAR, Colombo, Sri Lanka

Fernando S (2008) Approaching food as a strategy towards global survival in a better world Omertaa, J Appl Anthropol 0039:312–318

Fernando S (2014) Ecological agriculture is the way out of poverty. In: Social watch (ed) Social watch report 2014. Montevideo, Uruguay

Fernando S (2007) Peasants situation and human rights in Sri Lanka. Focus Asia-Pacific 50:1–4

Fernando S (2012) People and the environment should be first. In: Social Watch (ed) Social Watch Report 2012-The Right to a Future. Social Watch, Montevideo, Uruguay, pp. 174–175

Firdaus RBR, Gunaratne MS, Rahmat SR, Kamsi NS (2019) Does climate change only affect food availability? What else matters? Cogent Food Agric 5:1707607. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1707607

Firdaus RBR, Leong Tan M, Rahmat SR, Senevi Gunaratne M (2020) Paddy, rice and food security in Malaysia: a review of climate change impacts. Cogent Soc Sci 6:1818373. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1818373

Firdaus RBR, Mohamad SS, Singh PSJ et al. (2018) Impact of climate change on agriculture based on the crop growth simulation (CGS) model. Geogr Malaysian J Soc Sp 14:53–66

Foti J, De Silva L (2010) A seat at the table: including the poor in decisions for development and environment. World Resources Institute, Washington DC, USA

Francis C, Lieblein G, Gliessman S et al. (2003) Agroecology: the ecology of food systems. J Sustain Agric 22:99–118. https://doi.org/10.1300/J064v22n03_10

Giunta I (2014) Food sovereignty in Ecuador: peasant struggles and the challenge of institutionalization. J Peasant Stud 41:1201–1224. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.938057

Gliessman S (2013) Agroecology: growing the roots of resistance. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst 37:19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440046.2012.736927

Gordillo G, Jeronimo OM (2013) Food security and sovereignty- base document for discussion. FAO, Rome, Italy

Greenpeace International (2009) Agriculture at a crossroads: food for survival. Greenpeace International, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Haan R de, Hambly Odame H, Thevathasan N, Nissanka SP (2020) Local knowledge and perspectives of change in homegardens: a photovoice study in Kandy District, Sri Lanka. Sustain 12: https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12176866

Hapuarachchi HASU, Jayawardena IMSP (2015) Modulation of seasonal rainfall in Sri Lanka by ENSO extremes. Sri Lanka J Meteorol 1:3–11

Herath G (2018) Challenges to meeting the UN sustainable development goals in Sri Lanka. Asian Surv 58:726–746. https://doi.org/10.1525/as.2018.58.4.726

Ibrahim FA (2020) Between the sea and the land: small-scale fishers and multiple vulnerabilities in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka J Soc Sci 43:5–20. https://doi.org/10.4038/sljss.v43i1.7641

IFAD (2014) The international year of family farming: IFAD’s commitment and call for action. International Fund for Agricultural Development, Rome, Italy

IMF (2018) Sri Lanka: selected issues. International Monetary Fund, Washington DC, USA

Institute of Policy Studies (2018) Climate change, food security and rural livelihoods in Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka

Intriago R, Amézcua RG, Bravo E, O’Connell C (2017) Agroecology in Ecuador: historical processes, achievements, and challenges. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst 41:311–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2017.1284174

Islam S, Wong AT (2017) Climate change and food in/security: a critical nexus. Environments 4:1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments4020038

Article CAS Google Scholar

Jayawardene H, Jayewardene D, Sonnadara D (2015) Interannual variability of precipitation in Sri Lanka. J Natl Sci Found Sri Lanka 43:75. https://doi.org/10.4038/jnsfsr.v43i1.7917

Khadse A, Rosset PM, Morales H, Ferguson BG (2018) Taking agroecology to scale: the Zero Budget Natural Farming peasant movement in Karnataka, India. J Peasant Stud 45:192–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1276450

Kim H-Y, Ko J, Kang S, Tenhunen J (2013) Impacts of climate change on paddy rice yield in a temperate climate. Glob Chang Biol 19:548–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12047

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

La Via Campesina (2018) Food sovereignty now: a guide to food sovereignty. European Coordination Via Campesina, Bruxelles, Belgium

La Via Campesina (2003) Food sovereignty: Via Campesina. https://viacampesina.org/en/food-sovereignty/ . Accessed 13 Jan 2021

La Via Campesina (2020) Via Campesina: International Peasants’ Movement. In: La Via Campesina. https://viacampesina.org/en . Accessed 13 Jan 2021

Landreth N, Saito O (2014) An ecosystem services approach to sustainable livelihoods in the homegardens of Kandy, Sri Lanka. Aust Geogr 45:355–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2014.930003

Levkoe CZ, Brem-Wilson J, Anderson CR (2019) People, power, change: three pillars of a food sovereignty research praxis. J Peasant Stud 46:1389–1412. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1512488

Mani M, Bandyopadhyay S, Chonabayashi S et al. (2018) South Asia’s hotspots: the impact of temparature and precipitation changes on living standards. The World Bank Group, Washington, DC

Book Google Scholar

Marambe B, Ranjith Punyawardena PS, Premalal S et al. (2015) Climate, climate risk, and food security in Sri Lanka: the need for strengthening adaptation strategies. In: Leal Filho W (ed) Handbook of climate change adaptation. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 1759–1789

Mattsson E, Ostwald M, Nissanka SP (2018) What is good about Sri Lankan homegardens with regards to food security? A synthesis of the current scientific knowledge of a multifunctional land-use system. Agrofor Syst 92:1469–1484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-017-0093-6

McKay B, Nehring R, Walsh-Dilley M (2014) The ‘state’ of food sovereignty in Latin America: political projects and alternative pathways in Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia. J Peasant Stud 41:1175–1200. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.964217

McKeon N (2015) La Via Campesina: the ‘peasants” way’ to changing the system, not the climate.’. J World-Systems Res 21:241–249. https://doi.org/10.5195/jwsr.2015.19

Melvani K, Myers B, Palaniandavan N, et al (2020) Forest gardens increase the financial viability of farming enterprises in Sri Lanka. Agrofor Syst 9: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-020-00564-9

Menike LMCS, Keeragalaarachchi KAGP (2016) Adaptation to climate change by smallholder farmers in rural communities: evidence from Sri Lanka. Procedia Food Sci 6:288–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profoo.2016.02.057

Ministry of Agriculture (2019) Sri Lanka Overarching Agricultural Policy (Draft). Colombo, Sri Lanka

Ministry of Fisheries (2007) Ten year development policy framework of the fisheries and aquatic resources sector. Colombo, Sri Lanka

Moyer JD, Hedden S (2020) Are we on the right path to achieve the sustainable development goals? World Dev 127:104749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104749

Myers SS, Zanobetti A, Kloog I et al. (2014) Increasing CO 2 threatens human nutrition. Nature 510:139–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13179

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

NARA (2018) Fisheries industry outlook-2017. National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA), Colombo, Sri Lanka

Nyeleni (2007a) Declaration of Nyeleni 2007. Selingue, Mali

Nyeleni (2007b) Nyeleni synthesis report. Selingue, Mali

Ortega-Espes D, Finch S (2018) Agroecology: innovating for sustainable agriculture & food systems. Friends of the Earth International, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Patel R (2009) Food sovereignty. J Peasant Stud 36:663–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150903143079

Pimbert M (2010) Towards food sovereignty: reclaiming autonomous food systems. CAFS, IIED and RCC, London and Munich

Plahe J, Wright S, Marembo M. (2017) Livelihoods crises in Vidarbha, India: food sovereignty through traditional farming systems as a possible solution. J South Asian Stud 40:600–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401.2017.1339581

Pushpakumara DKNG, Marambe B, Silva GLLP et al. (2012) A Review of research on homegardens in Sri lanka: the status, importance and future perspective. Trop Agric 160:55–125

Ratnasiri S, Walisinghe R, Rohde N, Guest R (2019) The effects of climatic variation on rice production in Sri Lanka. Appl Econ 51:4700–4710. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1597253

Reardon JAS, Perez RA (2010) Agroecology and the development of indicators of food sovereignty in cuban food systems. J Sustain Agric 34:907–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/10440046.2010.519205

Rosset PM, Martínez-Torres ME (2014) Food sovereignty and agroecology in the convergence of rural social movements. In: Constance DH, Renard M-C, Rivera-Ferre MG (eds) Alternative agrifood movements: patterns of convergence and divergence. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 137–157

Sage C (2014) Food security, food sovereignty and the special rapporteur. Dialogues Hum Geogr 4:195–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820614537156

Sathischandra HGAS, Marambe B, Punyawardena R (2014) Seasonal changes in temperature and rainfall and its relationship with the incidence of weeds and insect pests in rice (Oryza sativa L) cultivation in Sri Lanka. Clim Chang Environ Sustain 2:105–115. https://doi.org/10.5958/2320-642X.2014.00002.7

Schaller N (2013) Agro-ecology: different definitions, common principles. Centre for Studies and Strategic Foresight, Cedex, France

Schmidhuber J, Tubiello FN (2007) Global food security under climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:19703–19708. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0701976104

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

De Schutter O (2014) Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Final report: the transformative potential of the right to food, United Nations General Essembly, New York, NY, USA

Seo S-NN, Mendelsohn R, Munasinghe M (2005) Climate change and agriculture in Sri Lanka: a Ricardian valuation. Environ Dev Econ 10:581–596. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X05002044

Shaw DJ, Clay EJ (1998) Global hunger and food security after the World Food Summit. Can J Dev Stud Can d’études du développement 19:55–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.1998.9669778

Siriwardana CSA, Jayasiri GP, Hettiarachchi SSL (2018) Investigation of efficiency and effectiveness of the existing disaster management frameworks in Sri Lanka. Procedia Eng 212:1091–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2018.01.141

Sosai AS (2015) Illegal fishing activity‒a new threat in mannar island coastal area (Sri Lanka). Transylvanian Rev Syst Ecol Res 17:95–108. https://doi.org/10.1515/trser-2015-0051

South Asia Policy & Research Institute (2017) National strategic review of food security and nutrition towards zero hunger. WFP, Rome, Italy

Stringer R (2016) Food security global overview. In: Caraher M, Coveney J (eds) Food poverty and insecurity: international food inequalities, First. Springer International Publishing AG, 125

Sumathipala W (2014) El Nino-A short term signal of a long term and a large scale climate variation. J Natl Sci Found Sri Lanka 42:199–200. https://doi.org/10.4038/jnsfsr.v42i3.7405

Tan BT, Fam PS, Firdaus RBR et al. (2021) Impact of climate change on rice yield in Malaysia: a panel data analysis. Agriculture 11:569. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11060569

The Economist Intellgence Unit (2019) Global Food Security Index 2019: strengthening food systems and the environment through innovation and investment. London, UK

The Global Economy.com (2020) Sri Lanka Economic Indicators. Bus Econ data 200 Ctries. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Sri-Lanka/ . Accessed 28 Aug 2020

The World Bank (2018) Sri Lanka’ s hotspots:the impact of temperature and precipitation changes on living standard. The World Bank Group, Washington, DC

The World Bank (2017) Sri Lanka: managing coastal natural wealth. The World Bank Group, Washington, DC

The World Bank, UN (2010) Natural hazards, unnatural disasters: the economics of effective prevention. The World Bank Group, Washington DC

Thomas V (2017) Climate change and natural disasters: Transforming economies and policies for a sustainable future. Taylor & Francis, London and New York, NY