Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Content Analysis | Guide, Methods & Examples

Content Analysis | Guide, Methods & Examples

Published on July 18, 2019 by Amy Luo . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Content analysis is a research method used to identify patterns in recorded communication. To conduct content analysis, you systematically collect data from a set of texts, which can be written, oral, or visual:

- Books, newspapers and magazines

- Speeches and interviews

- Web content and social media posts

- Photographs and films

Content analysis can be both quantitative (focused on counting and measuring) and qualitative (focused on interpreting and understanding). In both types, you categorize or “code” words, themes, and concepts within the texts and then analyze the results.

Table of contents

What is content analysis used for, advantages of content analysis, disadvantages of content analysis, how to conduct content analysis, other interesting articles.

Researchers use content analysis to find out about the purposes, messages, and effects of communication content. They can also make inferences about the producers and audience of the texts they analyze.

Content analysis can be used to quantify the occurrence of certain words, phrases, subjects or concepts in a set of historical or contemporary texts.

Quantitative content analysis example

To research the importance of employment issues in political campaigns, you could analyze campaign speeches for the frequency of terms such as unemployment , jobs , and work and use statistical analysis to find differences over time or between candidates.

In addition, content analysis can be used to make qualitative inferences by analyzing the meaning and semantic relationship of words and concepts.

Qualitative content analysis example

To gain a more qualitative understanding of employment issues in political campaigns, you could locate the word unemployment in speeches, identify what other words or phrases appear next to it (such as economy, inequality or laziness ), and analyze the meanings of these relationships to better understand the intentions and targets of different campaigns.

Because content analysis can be applied to a broad range of texts, it is used in a variety of fields, including marketing, media studies, anthropology, cognitive science, psychology, and many social science disciplines. It has various possible goals:

- Finding correlations and patterns in how concepts are communicated

- Understanding the intentions of an individual, group or institution

- Identifying propaganda and bias in communication

- Revealing differences in communication in different contexts

- Analyzing the consequences of communication content, such as the flow of information or audience responses

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

- Unobtrusive data collection

You can analyze communication and social interaction without the direct involvement of participants, so your presence as a researcher doesn’t influence the results.

- Transparent and replicable

When done well, content analysis follows a systematic procedure that can easily be replicated by other researchers, yielding results with high reliability .

- Highly flexible

You can conduct content analysis at any time, in any location, and at low cost – all you need is access to the appropriate sources.

Focusing on words or phrases in isolation can sometimes be overly reductive, disregarding context, nuance, and ambiguous meanings.

Content analysis almost always involves some level of subjective interpretation, which can affect the reliability and validity of the results and conclusions, leading to various types of research bias and cognitive bias .

- Time intensive

Manually coding large volumes of text is extremely time-consuming, and it can be difficult to automate effectively.

If you want to use content analysis in your research, you need to start with a clear, direct research question .

Example research question for content analysis

Is there a difference in how the US media represents younger politicians compared to older ones in terms of trustworthiness?

Next, you follow these five steps.

1. Select the content you will analyze

Based on your research question, choose the texts that you will analyze. You need to decide:

- The medium (e.g. newspapers, speeches or websites) and genre (e.g. opinion pieces, political campaign speeches, or marketing copy)

- The inclusion and exclusion criteria (e.g. newspaper articles that mention a particular event, speeches by a certain politician, or websites selling a specific type of product)

- The parameters in terms of date range, location, etc.

If there are only a small amount of texts that meet your criteria, you might analyze all of them. If there is a large volume of texts, you can select a sample .

2. Define the units and categories of analysis

Next, you need to determine the level at which you will analyze your chosen texts. This means defining:

- The unit(s) of meaning that will be coded. For example, are you going to record the frequency of individual words and phrases, the characteristics of people who produced or appear in the texts, the presence and positioning of images, or the treatment of themes and concepts?

- The set of categories that you will use for coding. Categories can be objective characteristics (e.g. aged 30-40 , lawyer , parent ) or more conceptual (e.g. trustworthy , corrupt , conservative , family oriented ).

Your units of analysis are the politicians who appear in each article and the words and phrases that are used to describe them. Based on your research question, you have to categorize based on age and the concept of trustworthiness. To get more detailed data, you also code for other categories such as their political party and the marital status of each politician mentioned.

3. Develop a set of rules for coding

Coding involves organizing the units of meaning into the previously defined categories. Especially with more conceptual categories, it’s important to clearly define the rules for what will and won’t be included to ensure that all texts are coded consistently.

Coding rules are especially important if multiple researchers are involved, but even if you’re coding all of the text by yourself, recording the rules makes your method more transparent and reliable.

In considering the category “younger politician,” you decide which titles will be coded with this category ( senator, governor, counselor, mayor ). With “trustworthy”, you decide which specific words or phrases related to trustworthiness (e.g. honest and reliable ) will be coded in this category.

4. Code the text according to the rules

You go through each text and record all relevant data in the appropriate categories. This can be done manually or aided with computer programs, such as QSR NVivo , Atlas.ti and Diction , which can help speed up the process of counting and categorizing words and phrases.

Following your coding rules, you examine each newspaper article in your sample. You record the characteristics of each politician mentioned, along with all words and phrases related to trustworthiness that are used to describe them.

5. Analyze the results and draw conclusions

Once coding is complete, the collected data is examined to find patterns and draw conclusions in response to your research question. You might use statistical analysis to find correlations or trends, discuss your interpretations of what the results mean, and make inferences about the creators, context and audience of the texts.

Let’s say the results reveal that words and phrases related to trustworthiness appeared in the same sentence as an older politician more frequently than they did in the same sentence as a younger politician. From these results, you conclude that national newspapers present older politicians as more trustworthy than younger politicians, and infer that this might have an effect on readers’ perceptions of younger people in politics.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Cohort study

- Peer review

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Luo, A. (2023, June 22). Content Analysis | Guide, Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/content-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, descriptive research | definition, types, methods & examples, reliability vs. validity in research | difference, types and examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Chapter 17. Content Analysis

Introduction.

Content analysis is a term that is used to mean both a method of data collection and a method of data analysis. Archival and historical works can be the source of content analysis, but so too can the contemporary media coverage of a story, blogs, comment posts, films, cartoons, advertisements, brand packaging, and photographs posted on Instagram or Facebook. Really, almost anything can be the “content” to be analyzed. This is a qualitative research method because the focus is on the meanings and interpretations of that content rather than strictly numerical counts or variables-based causal modeling. [1] Qualitative content analysis (sometimes referred to as QCA) is particularly useful when attempting to define and understand prevalent stories or communication about a topic of interest—in other words, when we are less interested in what particular people (our defined sample) are doing or believing and more interested in what general narratives exist about a particular topic or issue. This chapter will explore different approaches to content analysis and provide helpful tips on how to collect data, how to turn that data into codes for analysis, and how to go about presenting what is found through analysis. It is also a nice segue between our data collection methods (e.g., interviewing, observation) chapters and chapters 18 and 19, whose focus is on coding, the primary means of data analysis for most qualitative data. In many ways, the methods of content analysis are quite similar to the method of coding.

Although the body of material (“content”) to be collected and analyzed can be nearly anything, most qualitative content analysis is applied to forms of human communication (e.g., media posts, news stories, campaign speeches, advertising jingles). The point of the analysis is to understand this communication, to systematically and rigorously explore its meanings, assumptions, themes, and patterns. Historical and archival sources may be the subject of content analysis, but there are other ways to analyze (“code”) this data when not overly concerned with the communicative aspect (see chapters 18 and 19). This is why we tend to consider content analysis its own method of data collection as well as a method of data analysis. Still, many of the techniques you learn in this chapter will be helpful to any “coding” scheme you develop for other kinds of qualitative data. Just remember that content analysis is a particular form with distinct aims and goals and traditions.

An Overview of the Content Analysis Process

The first step: selecting content.

Figure 17.2 is a display of possible content for content analysis. The first step in content analysis is making smart decisions about what content you will want to analyze and to clearly connect this content to your research question or general focus of research. Why are you interested in the messages conveyed in this particular content? What will the identification of patterns here help you understand? Content analysis can be fun to do, but in order to make it research, you need to fit it into a research plan.

| New stories | Blogs | Comment posts | Lyrics |

| Letters to editor | Films | Cartoons | Advertisements |

| Brand packaging | Logos | Instagram photos | Tweets |

| Photographs | Graffiti | Street signs | Personalized license plates |

| Avatars (names, shapes, presentations) | Nicknames | Band posters | Building names |

Figure 17.1. A Non-exhaustive List of "Content" for Content Analysis

To take one example, let us imagine you are interested in gender presentations in society and how presentations of gender have changed over time. There are various forms of content out there that might help you document changes. You could, for example, begin by creating a list of magazines that are coded as being for “women” (e.g., Women’s Daily Journal ) and magazines that are coded as being for “men” (e.g., Men’s Health ). You could then select a date range that is relevant to your research question (e.g., 1950s–1970s) and collect magazines from that era. You might create a “sample” by deciding to look at three issues for each year in the date range and a systematic plan for what to look at in those issues (e.g., advertisements? Cartoons? Titles of articles? Whole articles?). You are not just going to look at some magazines willy-nilly. That would not be systematic enough to allow anyone to replicate or check your findings later on. Once you have a clear plan of what content is of interest to you and what you will be looking at, you can begin, creating a record of everything you are including as your content. This might mean a list of each advertisement you look at or each title of stories in those magazines along with its publication date. You may decide to have multiple “content” in your research plan. For each content, you want a clear plan for collecting, sampling, and documenting.

The Second Step: Collecting and Storing

Once you have a plan, you are ready to collect your data. This may entail downloading from the internet, creating a Word document or PDF of each article or picture, and storing these in a folder designated by the source and date (e.g., “ Men’s Health advertisements, 1950s”). Sølvberg ( 2021 ), for example, collected posted job advertisements for three kinds of elite jobs (economic, cultural, professional) in Sweden. But collecting might also mean going out and taking photographs yourself, as in the case of graffiti, street signs, or even what people are wearing. Chaise LaDousa, an anthropologist and linguist, took photos of “house signs,” which are signs, often creative and sometimes offensive, hung by college students living in communal off-campus houses. These signs were a focal point of college culture, sending messages about the values of the students living in them. Some of the names will give you an idea: “Boot ’n Rally,” “The Plantation,” “Crib of the Rib.” The students might find these signs funny and benign, but LaDousa ( 2011 ) argued convincingly that they also reproduced racial and gender inequalities. The data here already existed—they were big signs on houses—but the researcher had to collect the data by taking photographs.

In some cases, your content will be in physical form but not amenable to photographing, as in the case of films or unwieldy physical artifacts you find in the archives (e.g., undigitized meeting minutes or scrapbooks). In this case, you need to create some kind of detailed log (fieldnotes even) of the content that you can reference. In the case of films, this might mean watching the film and writing down details for key scenes that become your data. [2] For scrapbooks, it might mean taking notes on what you are seeing, quoting key passages, describing colors or presentation style. As you might imagine, this can take a lot of time. Be sure you budget this time into your research plan.

Researcher Note

A note on data scraping : Data scraping, sometimes known as screen scraping or frame grabbing, is a way of extracting data generated by another program, as when a scraping tool grabs information from a website. This may help you collect data that is on the internet, but you need to be ethical in how to employ the scraper. A student once helped me scrape thousands of stories from the Time magazine archives at once (although it took several hours for the scraping process to complete). These stories were freely available, so the scraping process simply sped up the laborious process of copying each article of interest and saving it to my research folder. Scraping tools can sometimes be used to circumvent paywalls. Be careful here!

The Third Step: Analysis

There is often an assumption among novice researchers that once you have collected your data, you are ready to write about what you have found. Actually, you haven’t yet found anything, and if you try to write up your results, you will probably be staring sadly at a blank page. Between the collection and the writing comes the difficult task of systematically and repeatedly reviewing the data in search of patterns and themes that will help you interpret the data, particularly its communicative aspect (e.g., What is it that is being communicated here, with these “house signs” or in the pages of Men’s Health ?).

The first time you go through the data, keep an open mind on what you are seeing (or hearing), and take notes about your observations that link up to your research question. In the beginning, it can be difficult to know what is relevant and what is extraneous. Sometimes, your research question changes based on what emerges from the data. Use the first round of review to consider this possibility, but then commit yourself to following a particular focus or path. If you are looking at how gender gets made or re-created, don’t follow the white rabbit down a hole about environmental injustice unless you decide that this really should be the focus of your study or that issues of environmental injustice are linked to gender presentation. In the second round of review, be very clear about emerging themes and patterns. Create codes (more on these in chapters 18 and 19) that will help you simplify what you are noticing. For example, “men as outdoorsy” might be a common trope you see in advertisements. Whenever you see this, mark the passage or picture. In your third (or fourth or fifth) round of review, begin to link up the tropes you’ve identified, looking for particular patterns and assumptions. You’ve drilled down to the details, and now you are building back up to figure out what they all mean. Start thinking about theory—either theories you have read about and are using as a frame of your study (e.g., gender as performance theory) or theories you are building yourself, as in the Grounded Theory tradition. Once you have a good idea of what is being communicated and how, go back to the data at least one more time to look for disconfirming evidence. Maybe you thought “men as outdoorsy” was of importance, but when you look hard, you note that women are presented as outdoorsy just as often. You just hadn’t paid attention. It is very important, as any kind of researcher but particularly as a qualitative researcher, to test yourself and your emerging interpretations in this way.

The Fourth and Final Step: The Write-Up

Only after you have fully completed analysis, with its many rounds of review and analysis, will you be able to write about what you found. The interpretation exists not in the data but in your analysis of the data. Before writing your results, you will want to very clearly describe how you chose the data here and all the possible limitations of this data (e.g., historical-trace problem or power problem; see chapter 16). Acknowledge any limitations of your sample. Describe the audience for the content, and discuss the implications of this. Once you have done all of this, you can put forth your interpretation of the communication of the content, linking to theory where doing so would help your readers understand your findings and what they mean more generally for our understanding of how the social world works. [3]

Analyzing Content: Helpful Hints and Pointers

Although every data set is unique and each researcher will have a different and unique research question to address with that data set, there are some common practices and conventions. When reviewing your data, what do you look at exactly? How will you know if you have seen a pattern? How do you note or mark your data?

Let’s start with the last question first. If your data is stored digitally, there are various ways you can highlight or mark up passages. You can, of course, do this with literal highlighters, pens, and pencils if you have print copies. But there are also qualitative software programs to help you store the data, retrieve the data, and mark the data. This can simplify the process, although it cannot do the work of analysis for you.

Qualitative software can be very expensive, so the first thing to do is to find out if your institution (or program) has a universal license its students can use. If they do not, most programs have special student licenses that are less expensive. The two most used programs at this moment are probably ATLAS.ti and NVivo. Both can cost more than $500 [4] but provide everything you could possibly need for storing data, content analysis, and coding. They also have a lot of customer support, and you can find many official and unofficial tutorials on how to use the programs’ features on the web. Dedoose, created by academic researchers at UCLA, is a decent program that lacks many of the bells and whistles of the two big programs. Instead of paying all at once, you pay monthly, as you use the program. The monthly fee is relatively affordable (less than $15), so this might be a good option for a small project. HyperRESEARCH is another basic program created by academic researchers, and it is free for small projects (those that have limited cases and material to import). You can pay a monthly fee if your project expands past the free limits. I have personally used all four of these programs, and they each have their pluses and minuses.

Regardless of which program you choose, you should know that none of them will actually do the hard work of analysis for you. They are incredibly useful for helping you store and organize your data, and they provide abundant tools for marking, comparing, and coding your data so you can make sense of it. But making sense of it will always be your job alone.

So let’s say you have some software, and you have uploaded all of your content into the program: video clips, photographs, transcripts of news stories, articles from magazines, even digital copies of college scrapbooks. Now what do you do? What are you looking for? How do you see a pattern? The answers to these questions will depend partially on the particular research question you have, or at least the motivation behind your research. Let’s go back to the idea of looking at gender presentations in magazines from the 1950s to the 1970s. Here are some things you can look at and code in the content: (1) actions and behaviors, (2) events or conditions, (3) activities, (4) strategies and tactics, (5) states or general conditions, (6) meanings or symbols, (7) relationships/interactions, (8) consequences, and (9) settings. Table 17.1 lists these with examples from our gender presentation study.

Table 17.1. Examples of What to Note During Content Analysis

| What can be noted/coded | Example from Gender Presentation Study |

|---|---|

| Actions and behaviors | |

| Events or conditions | |

| Activities | |

| Strategies and tactics | |

| States/conditions | |

| Meanings/symbols | |

| Relationships/interactions | |

| Consequences | |

| Settings |

One thing to note about the examples in table 17.1: sometimes we note (mark, record, code) a single example, while other times, as in “settings,” we are recording a recurrent pattern. To help you spot patterns, it is useful to mark every setting, including a notation on gender. Using software can help you do this efficiently. You can then call up “setting by gender” and note this emerging pattern. There’s an element of counting here, which we normally think of as quantitative data analysis, but we are using the count to identify a pattern that will be used to help us interpret the communication. Content analyses often include counting as part of the interpretive (qualitative) process.

In your own study, you may not need or want to look at all of the elements listed in table 17.1. Even in our imagined example, some are more useful than others. For example, “strategies and tactics” is a bit of a stretch here. In studies that are looking specifically at, say, policy implementation or social movements, this category will prove much more salient.

Another way to think about “what to look at” is to consider aspects of your content in terms of units of analysis. You can drill down to the specific words used (e.g., the adjectives commonly used to describe “men” and “women” in your magazine sample) or move up to the more abstract level of concepts used (e.g., the idea that men are more rational than women). Counting for the purpose of identifying patterns is particularly useful here. How many times is that idea of women’s irrationality communicated? How is it is communicated (in comic strips, fictional stories, editorials, etc.)? Does the incidence of the concept change over time? Perhaps the “irrational woman” was everywhere in the 1950s, but by the 1970s, it is no longer showing up in stories and comics. By tracing its usage and prevalence over time, you might come up with a theory or story about gender presentation during the period. Table 17.2 provides more examples of using different units of analysis for this work along with suggestions for effective use.

Table 17.2. Examples of Unit of Analysis in Content Analysis

| Unit of Analysis | How Used... |

|---|---|

| Words | |

| Themes | |

| Characters | |

| Paragraphs | |

| Items | |

| Concepts | |

| Semantics |

Every qualitative content analysis is unique in its particular focus and particular data used, so there is no single correct way to approach analysis. You should have a better idea, however, of what kinds of things to look for and what to look for. The next two chapters will take you further into the coding process, the primary analytical tool for qualitative research in general.

Further Readings

Cidell, Julie. 2010. “Content Clouds as Exploratory Qualitative Data Analysis.” Area 42(4):514–523. A demonstration of using visual “content clouds” as a form of exploratory qualitative data analysis using transcripts of public meetings and content of newspaper articles.

Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Sarah E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15(9):1277–1288. Distinguishes three distinct approaches to QCA: conventional, directed, and summative. Uses hypothetical examples from end-of-life care research.

Jackson, Romeo, Alex C. Lange, and Antonio Duran. 2021. “A Whitened Rainbow: The In/Visibility of Race and Racism in LGBTQ Higher Education Scholarship.” Journal Committed to Social Change on Race and Ethnicity (JCSCORE) 7(2):174–206.* Using a “critical summative content analysis” approach, examines research published on LGBTQ people between 2009 and 2019.

Krippendorff, Klaus. 2018. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology . 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A very comprehensive textbook on both quantitative and qualitative forms of content analysis.

Mayring, Philipp. 2022. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Formulates an eight-step approach to QCA.

Messinger, Adam M. 2012. “Teaching Content Analysis through ‘Harry Potter.’” Teaching Sociology 40(4):360–367. This is a fun example of a relatively brief foray into content analysis using the music found in Harry Potter films.

Neuendorft, Kimberly A. 2002. The Content Analysis Guidebook . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Although a helpful guide to content analysis in general, be warned that this textbook definitely favors quantitative over qualitative approaches to content analysis.

Schrier, Margrit. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice . Thousand Okas, CA: SAGE. Arguably the most accessible guidebook for QCA, written by a professor based in Germany.

Weber, Matthew A., Shannon Caplan, Paul Ringold, and Karen Blocksom. 2017. “Rivers and Streams in the Media: A Content Analysis of Ecosystem Services.” Ecology and Society 22(3).* Examines the content of a blog hosted by National Geographic and articles published in The New York Times and the Wall Street Journal for stories on rivers and streams (e.g., water-quality flooding).

- There are ways of handling content analysis quantitatively, however. Some practitioners therefore specify qualitative content analysis (QCA). In this chapter, all content analysis is QCA unless otherwise noted. ↵

- Note that some qualitative software allows you to upload whole films or film clips for coding. You will still have to get access to the film, of course. ↵

- See chapter 20 for more on the final presentation of research. ↵

- . Actually, ATLAS.ti is an annual license, while NVivo is a perpetual license, but both are going to cost you at least $500 to use. Student rates may be lower. And don’t forget to ask your institution or program if they already have a software license you can use. ↵

A method of both data collection and data analysis in which a given content (textual, visual, graphic) is examined systematically and rigorously to identify meanings, themes, patterns and assumptions. Qualitative content analysis (QCA) is concerned with gathering and interpreting an existing body of material.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Afr J Emerg Med

- v.7(3); 2017 Sep

A hands-on guide to doing content analysis

Christen erlingsson.

a Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Linnaeus University, Kalmar 391 82, Sweden

Petra Brysiewicz

b School of Nursing & Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4041, South Africa

Associated Data

There is a growing recognition for the important role played by qualitative research and its usefulness in many fields, including the emergency care context in Africa. Novice qualitative researchers are often daunted by the prospect of qualitative data analysis and thus may experience much difficulty in the data analysis process. Our objective with this manuscript is to provide a practical hands-on example of qualitative content analysis to aid novice qualitative researchers in their task.

African relevance

- • Qualitative research is useful to deepen the understanding of the human experience.

- • Novice qualitative researchers may benefit from this hands-on guide to content analysis.

- • Practical tips and data analysis templates are provided to assist in the analysis process.

Introduction

There is a growing recognition for the important role played by qualitative research and its usefulness in many fields, including emergency care research. An increasing number of health researchers are currently opting to use various qualitative research approaches in exploring and describing complex phenomena, providing textual accounts of individuals’ “life worlds”, and giving voice to vulnerable populations our patients so often represent. Many articles and books are available that describe qualitative research methods and provide overviews of content analysis procedures [1] , [2] , [3] , [4] , [5] , [6] , [7] , [8] , [9] , [10] . Some articles include step-by-step directions intended to clarify content analysis methodology. What we have found in our teaching experience is that these directions are indeed very useful. However, qualitative researchers, especially novice researchers, often struggle to understand what is happening on and between steps, i.e., how the steps are taken.

As research supervisors of postgraduate health professionals, we often meet students who present brilliant ideas for qualitative studies that have potential to fill current gaps in the literature. Typically, the suggested studies aim to explore human experience. Research questions exploring human experience are expediently studied through analysing textual data e.g., collected in individual interviews, focus groups, documents, or documented participant observation. When reflecting on the proposed study aim together with the student, we often suggest content analysis methodology as the best fit for the study and the student, especially the novice researcher. The interview data are collected and the content analysis adventure begins. Students soon realise that data based on human experiences are complex, multifaceted and often carry meaning on multiple levels.

For many novice researchers, analysing qualitative data is found to be unexpectedly challenging and time-consuming. As they soon discover, there is no step-wise analysis process that can be applied to the data like a pattern cutter at a textile factory. They may become extremely annoyed and frustrated during the hands-on enterprise of qualitative content analysis.

The novice researcher may lament, “I’ve read all the methodology but don’t really know how to start and exactly what to do with my data!” They grapple with qualitative research terms and concepts, for example; differences between meaning units, codes, categories and themes, and regarding increasing levels of abstraction from raw data to categories or themes. The content analysis adventure may now seem to be a chaotic undertaking. But, life is messy, complex and utterly fascinating. Experiencing chaos during analysis is normal. Good advice for the qualitative researcher is to be open to the complexity in the data and utilise one’s flow of creativity.

Inspired primarily by descriptions of “conventional content analysis” in Hsieh and Shannon [3] , “inductive content analysis” in Elo and Kyngäs [5] and “qualitative content analysis of an interview text” in Graneheim and Lundman [1] , we have written this paper to help the novice qualitative researcher navigate the uncertainty in-between the steps of qualitative content analysis. We will provide advice and practical tips, as well as data analysis templates, to attempt to ease frustration and hopefully, inspire readers to discover how this exciting methodology contributes to developing a deeper understanding of human experience and our professional contexts.

Overview of qualitative content analysis

Synopsis of content analysis.

A common starting point for qualitative content analysis is often transcribed interview texts. The objective in qualitative content analysis is to systematically transform a large amount of text into a highly organised and concise summary of key results. Analysis of the raw data from verbatim transcribed interviews to form categories or themes is a process of further abstraction of data at each step of the analysis; from the manifest and literal content to latent meanings ( Fig. 1 and Table 1 ).

Example of analysis leading to higher levels of abstraction; from manifest to latent content.

Glossary of terms as used in this hands-on guide to doing content analysis. *

| Condensation | Condensation is a process of shortening the text while still preserving the core meaning |

| Code | A code can be thought of as a label; a name that most exactly describes what this particular condensed meaning unit is about. Usually one or two words long |

| Category | A category is formed by grouping together those codes that are related to each other through their content or context. In other words, codes are organised into a category when they are describing different aspects, similarities or differences, of the text’s content that belong together |

| When analysis has led to a plethora of codes, it can be helpful to first assimilate smaller groups of closely related codes in sub-categories. Sub-categories related to each other through their content can then be grouped into categories | |

| A category answers questions about , , , or ? In other words, categories are an expression of manifest content, i.e., what is visible and obvious in the data | |

| Category names are factual and short | |

| Theme | A theme can be seen as expressing an underlying meaning, i.e., latent content, found in two or more categories. |

| Themes are expressing data on an interpretative (latent) level. A theme answers questions such as , , , or ? | |

| A theme is intended to communicate with the reader on both an intellectual and emotional level. Therefore poetic and metaphoric language is well suited in theme names to express underlying meaning | |

| Theme names are very descriptive and include verbs, adverbs and adjectives |

The initial step is to read and re-read the interviews to get a sense of the whole, i.e., to gain a general understanding of what your participants are talking about. At this point you may already start to get ideas of what the main points or ideas are that your participants are expressing. Then one needs to start dividing up the text into smaller parts, namely, into meaning units. One then condenses these meaning units further. While doing this, you need to ensure that the core meaning is still retained. The next step is to label condensed meaning units by formulating codes and then grouping these codes into categories. Depending on the study’s aim and quality of the collected data, one may choose categories as the highest level of abstraction for reporting results or you can go further and create themes [1] , [2] , [3] , [5] , [8] .

Content analysis as a reflective process

You must mould the clay of the data , tapping into your intuition while maintaining a reflective understanding of how your own previous knowledge is influencing your analysis, i.e., your pre-understanding. In qualitative methodology, it is imperative to vigilantly maintain an awareness of one’s pre-understanding so that this does not influence analysis and/or results. This is the difficult balancing task of keeping a firm grip on one’s assumptions, opinions, and personal beliefs, and not letting them unconsciously steer your analysis process while simultaneously, and knowingly, utilising one’s pre-understanding to facilitate a deeper understanding of the data.

Content analysis, as in all qualitative analysis, is a reflective process. There is no “step 1, 2, 3, done!” linear progression in the analysis. This means that identifying and condensing meaning units, coding, and categorising are not one-time events. It is a continuous process of coding and categorising then returning to the raw data to reflect on your initial analysis. Are you still satisfied with the length of meaning units? Do the condensed meaning units and codes still “fit” with each other? Do the codes still fit into this particular category? Typically, a fair amount of adjusting is needed after the first analysis endeavour. For example: a meaning unit might need to be split into two meaning units in order to capture an additional core meaning; a code modified to more closely match the core meaning of the condensed meaning unit; or a category name tweaked to most accurately describe the included codes. In other words, analysis is a flexible reflective process of working and re-working your data that reveals connections and relationships. Once condensed meaning units are coded it is easier to get a bigger picture and see patterns in your codes and organise codes in categories.

Content analysis exercise

The synopsis above is representative of analysis descriptions in many content analysis articles. Although correct, such method descriptions still do not provide much support for the novice researcher during the actual analysis process. Aspiring to provide guidance and direction to support the novice, a practical example of doing the actual work of content analysis is provided in the following sections. This practical example is based on a transcribed interview excerpt that was part of a study that aimed to explore patients’ experiences of being admitted into the emergency centre ( Fig. 2 ).

Excerpt from interview text exploring “Patient’s experience of being admitted into the emergency centre”

This content analysis exercise provides instructions, tips, and advice to support the content analysis novice in a) familiarising oneself with the data and the hermeneutic spiral, b) dividing up the text into meaning units and subsequently condensing these meaning units, c) formulating codes, and d) developing categories and themes.

Familiarising oneself with the data and the hermeneutic spiral

An important initial phase in the data analysis process is to read and re-read the transcribed interview while keeping your aim in focus. Write down your initial impressions. Embrace your intuition. What is the text talking about? What stands out? How did you react while reading the text? What message did the text leave you with? In this analysis phase, you are gaining a sense of the text as a whole.

You may ask why this is important. During analysis, you will be breaking down the whole text into smaller parts. Returning to your notes with your initial impressions will help you see if your “parts” analysis is matching up with your first impressions of the “whole” text. Are your initial impressions visible in your analysis of the parts? Perhaps you need to go back and check for different perspectives. This is what is referred to as the hermeneutic spiral or hermeneutic circle. It is the process of comparing the parts to the whole to determine whether impressions of the whole verify the analysis of the parts in all phases of analysis. Each part should reflect the whole and the whole should be reflected in each part. This concept will become clearer as you start working with your data.

Dividing up the text into meaning units and condensing meaning units

You have now read the interview a number of times. Keeping your research aim and question clearly in focus, divide up the text into meaning units. Located meaning units are then condensed further while keeping the central meaning intact ( Table 2 ). The condensation should be a shortened version of the same text that still conveys the essential message of the meaning unit. Sometimes the meaning unit is already so compact that no further condensation is required. Some content analysis sources warn researchers against short meaning units, claiming that this can lead to fragmentation [1] . However, our personal experience as research supervisors has shown us that a greater problem for the novice is basing analysis on meaning units that are too large and include many meanings which are then lost in the condensation process.

Suggestion for how the exemplar interview text can be divided into meaning units and condensed meaning units ( condensations are in parentheses ).

| Meaning units (Condensations) |

|---|

| – Well, ok, where to start, that was a bad day in my life |

| – And it started so much the same as any other day. Right up until I was in that car crash! |

| – I still have nightmares about the sound of the other car and the lady screaming |

| – I can’t get the sound out of my head! |

| – it is a crazy place there. Do you know…do you work there? |

| – Well the people in the ambulance, when they had me in the ambulance they were looking worried, they kept telling me “there was lots of blood here” |

| – I really remember that. I thought, “Well there is not much I can do” |

| – Anyway, they seemed to want to get me into the EC in a real hurry. Then pushed my trolley in fast. |

| – I was feeling very cold. I think my legs were shaking. |

| – I think they had cut off my jeans. It was very uncomfortable, |

| – I wasn’t sure if the blanket covered me. I tried to grab the blanket with my hand. |

| – They must have given me something, maybe in that drip thing |

| – because I remember thinking that I should be in pain…. my legs must be sore… they were jammed in the car …but I really can’t remember feeling it |

| – just remember being cold, shaky |

| – feeling very alone (Feeling very alone) |

| – just saw everything moving past me |

| – I really wished my sister was there. She always seems to know what to do. She doesn’t panic, |

| – But there was no one. |

| – No one spoke to me. |

| – I wondered if I was invisible. |

| – They pushed me into a big room and there were lots of people there. It looked so busy, lots of noise, phones ringing, people talking loudly |

| – And I remember thinking that my sister wouldn’t know how to find me |

| – I tried to tell the ambulance guy that I needed him to please call my sister |

| – … but I had a thing on my face – for air they said before– so no one heard me, ( |

| – No one seemed to be looking at my face. |

| – They pushed me into the middle of the room and then walked away. They just left me |

| – And I am not sure what everyone was doing |

| – They seemed to be rushing around |

| – … but no one spoke to me. |

| – Suddenly someone grabbed my leg, |

| – I got such a fright |

| – they didn’t say anything to me… |

| – just poked my leg. |

| – I remember screaming. |

| – I remember that pain! |

Formulating codes

The next step is to develop codes that are descriptive labels for the condensed meaning units ( Table 3 ). Codes concisely describe the condensed meaning unit and are tools to help researchers reflect on the data in new ways. Codes make it easier to identify connections between meaning units. At this stage of analysis you are still keeping very close to your data with very limited interpretation of content. You may adjust, re-do, re-think, and re-code until you get to the point where you are satisfied that your choices are reasonable. Just as in the initial phase of getting to know your data as a whole, it is also good to write notes during coding on your impressions and reactions to the text.

Suggestions for coding of condensed meaning units.

| Meaning units condensations | Codes |

|---|---|

| It was a bad day in my life | The crash |

| Ordinary day until the crash | The crash |

| Nightmares about the sounds of the crash | The crash |

| Can’t get the sound out of my head | The crash |

| Emergency Centre is a crazy place | Emergency Centre is crazy |

| Ambulance staff looked worried about all the blood | In the ambulance |

| Ambulance staff were in a great hurry to get the trolley into EC | Staff in a hurry |

| I feel cold and my legs are shaking | Cold and shaky |

| Jeans cut off and very uncomfortable | Feeling exposed |

| Tried to grab the blanket to cover me | Feeling exposed |

| Must have been given something in a drip | In the ambulance |

| Thinking I should be in pain but can’t remember feeling legs jammed in the car | In the ambulance |

| Being cold and shaky | Cold and shaky |

| Feeling very alone | Feeling alone |

| Only saw things moving past me | Emergency Centre is busy |

| I wanted my sister who knows what to do and doesn’t panic | Wanting support |

| There was no one | Feeling alone |

| No one spoke to me | Not spoken to |

| Was I invisible | Feeling invisible |

| A big, busy, noisy room | Emergency Centre is noisy |

| Tried to tell ambulance guy I needed him to call my sister | Wanting help |

| With this thing on my face no one heard me | Not heard |

| No one looked at my face | Not looked at |

| Pushed me to the middle of the room, walked away, left me | Left alone |

| I didn’t know what they were doing | Unsure |

| They were rushing about | Staff in a hurry |

| No one spoke to me | Not spoken to |

| Suddenly someone grabbed my leg | Staff actions |

| I got a fright | Frightened |

| Saying nothing to me | Not spoken to |

| They poked my leg | Staff actions |

| I screamed | Pain |

| I remember the pain | Pain |

Developing categories and themes

The next step is to sort codes into categories that answer the questions who , what , when or where? One does this by comparing codes and appraising them to determine which codes seem to belong together, thereby forming a category. In other words, a category consists of codes that appear to deal with the same issue, i.e., manifest content visible in the data with limited interpretation on the part of the researcher. Category names are most often short and factual sounding.

In data that is rich with latent meaning, analysis can be carried on to create themes. In our practical example, we have continued the process of abstracting data to a higher level, from category to theme level, and developed three themes as well as an overarching theme ( Table 4 ). Themes express underlying meaning, i.e., latent content, and are formed by grouping two or more categories together. Themes are answering questions such as why , how , in what way or by what means? Therefore, theme names include verbs, adverbs and adjectives and are very descriptive or even poetic.

Suggestion for organisation of coded meaning units into categories and themes.

| Overarching theme: THE EMERGENCY CENTRE THROUGH PATIENTS’ EYES – ALONE AND COLD IN CHAOS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condensations | Codes | Categories | ||

| It was a bad day in my life | The crash | Reliving the crash | ||

| Ordinary day until the crash | The crash | |||

| Nightmares about the sounds of the crash | The crash | |||

| Can’t get the sound out of my head | The crash | |||

| Ambulance staff looked worried about all the blood | In the ambulance | Reliving the rescue | ||

| Must have been given something in a drip | In the ambulance | |||

| Thinking I should be in pain but can’t remember feeling legs jammed in the car | In the ambulance | |||

| Condensations | Codes | Categories | ||

| EC is a crazy place | Emergency Centre is crazy | Emergency Centre is a crazy, noisy, environment | ||

| Only saw things moving past me | Emergency Centre is busy | |||

| A big, busy noisy room | Emergency Centre is noisy | |||

| Ambulance staff were in a great hurry to get the trolley into EC | Staff in a hurry | Staff actions and non-actions | ||

| They were rushing about | Staff in a hurry | |||

| Pushed me to the middle of the room, walked away, left me | Left alone | |||

| No one spoke to me | Not spoken to | |||

| No one spoke to me | Not spoken to | |||

| Saying nothing to me | Not spoken to | |||

| Suddenly someone grabbed my leg | Staff actions | |||

| They poked my leg | Staff actions | |||

| No one looked at my face | Not looked at | |||

| With this thing on my face no one heard me | Not heard | |||

| I wanted my sister who knows what to do and doesn’t panic | Wanting support | Unmet needs | ||

| Tried to tell ambulance guy I needed him to call my sister | Wanting help | |||

| Condensations | Codes | Categories | ||

| I feel cold and my legs are shaking | Cold and shaky | Physical responses | ||

| Being cold and shaky | Cold and shaky | |||

| I remember the pain | Pain | |||

| I screamed | Pain | |||

| I couldn’t do anything about it | Feeling helpless | Emotional responses | ||

| Pants cut off and very uncomfortable | Feeling exposed | |||

| Tried to grab the blanket to cover me | Feeling exposed | |||

| Was I invisible | Feeling invisible | |||

| There was no one, | Feeling alone | |||

| Feeling very alone | Feeling alone | |||

| I didn’t know what they were doing | Unsure | |||

| Thinking my sister wouldn’t find me | Feeling lost | |||

| I got a fright | Frightened | |||

Some reflections and helpful tips

Understand your pre-understandings.

While conducting qualitative research, it is paramount that the researcher maintains a vigilance of non-bias during analysis. In other words, did you remain aware of your pre-understandings, i.e., your own personal assumptions, professional background, and previous experiences and knowledge? For example, did you zero in on particular aspects of the interview on account of your profession (as an emergency doctor, emergency nurse, pre-hospital professional, etc.)? Did you assume the patient’s gender? Did your assumptions affect your analysis? How about aspects of culpability; did you assume that this patient was at fault or that this patient was a victim in the crash? Did this affect how you analysed the text?

Staying aware of one’s pre-understandings is exactly as difficult as it sounds. But, it is possible and it is requisite. Focus on putting yourself and your pre-understandings in a holding pattern while you approach your data with an openness and expectation of finding new perspectives. That is the key: expect the new and be prepared to be surprised. If something in your data feels unusual, is different from what you know, atypical, or even odd – don’t by-pass it as “wrong”. Your reactions and intuitive responses are letting you know that here is something to pay extra attention to, besides the more comfortable condensing and coding of more easily recognisable meaning units.

Use your intuition

Intuition is a great asset in qualitative analysis and not to be dismissed as “unscientific”. Intuition results from tacit knowledge. Just as tacit knowledge is a hallmark of great clinicians [11] , [12] ; it is also an invaluable tool in analysis work [13] . Literally, take note of your gut reactions and intuitive guidance and remember to write these down! These notes often form a framework of possible avenues for further analysis and are especially helpful as you lift the analysis to higher levels of abstraction; from meaning units to condensed meaning units, to codes, to categories and then to the highest level of abstraction in content analysis, themes.

Aspects of coding and categorising hard to place data

All too often, the novice gets overwhelmed by interview material that deals with the general subject matter of the interview, but doesn’t seem to answer the research question. Don’t be too quick to consider such text as off topic or dross [6] . There is often data that, although not seeming to match the study aim precisely, is still important for illuminating the problem area. This can be seen in our practical example about exploring patients’ experiences of being admitted into the emergency centre. Initially the participant is describing the accident itself. While not directly answering the research question, the description is important for understanding the context of the experience of being admitted into the emergency centre. It is very common that participants will “begin at the beginning” and prologue their narratives in order to create a context that sets the scene. This type of contextual data is vital for gaining a deepened understanding of participants’ experiences.

In our practical example, the participant begins by describing the crash and the rescue, i.e., experiences leading up to and prior to admission to the emergency centre. That is why we have chosen in our analysis to code the condensed meaning unit “Ambulance staff looked worried about all the blood” as “In the ambulance” and place it in the category “Reliving the rescue”. We did not choose to include this meaning unit in the categories specifically about admission to the emergency centre itself. Do you agree with our coding choice? Would you have chosen differently?

Another common problem for the novice is deciding how to code condensed meaning units when the unit can be labelled in several different ways. At this point researchers usually groan and wish they had thought to ask one of those classic follow-up questions like “Can you tell me a little bit more about that?” We have examples of two such coding conundrums in the exemplar, as can be seen in Table 3 (codes we conferred on) and Table 4 (codes we reached consensus on). Do you agree with our choices or would you have chosen different codes? Our best advice is to go back to your impressions of the whole and lean into your intuition when choosing codes that are most reasonable and best fit your data.

A typical problem area during categorisation, especially for the novice researcher, is overlap between content in more than one initial category, i.e., codes included in one category also seem to be a fit for another category. Overlap between initial categories is very likely an indication that the jump from code to category was too big, a problem not uncommon when the data is voluminous and/or very complex. In such cases, it can be helpful to first sort codes into narrower categories, so-called subcategories. Subcategories can then be reviewed for possibilities of further aggregation into categories. In the case of a problematic coding, it is advantageous to return to the meaning unit and check if the meaning unit itself fits the category or if you need to reconsider your preliminary coding.

It is not uncommon to be faced by thorny problems such as these during coding and categorisation. Here we would like to reiterate how valuable it is to have fellow researchers with whom you can discuss and reflect together with, in order to reach consensus on the best way forward in your data analysis. It is really advantageous to compare your analysis with meaning units, condensations, coding and categorisations done by another researcher on the same text. Have you identified the same meaning units? Do you agree on coding? See similar patterns in the data? Concur on categories? Sometimes referred to as “researcher triangulation,” this is actually a key element in qualitative analysis and an important component when striving to ensure trustworthiness in your study [14] . Qualitative research is about seeking out variations and not controlling variables, as in quantitative research. Collaborating with others during analysis lets you tap into multiple perspectives and often makes it easier to see variations in the data, thereby enhancing the quality of your results as well as contributing to the rigor of your study. It is important to note that it is not necessary to force consensus in the findings but one can embrace these variations in interpretation and use that to capture the richness in the data.

Yet there are times when neither openness, pre-understanding, intuition, nor researcher triangulation does the job; for example, when analysing an interview and one is simply confused on how to code certain meaning units. At such times, there are a variety of options. A good starting place is to re-read all the interviews through the lens of this specific issue and actively search for other similar types of meaning units you might have missed. Another way to handle this is to conduct further interviews with specific queries that hopefully shed light on the issue. A third option is to have a follow-up interview with the same person and ask them to explain.

Additional tips

It is important to remember that in a typical project there are several interviews to analyse. Codes found in a single interview serve as a starting point as you then work through the remaining interviews coding all material. Form your categories and themes when all project interviews have been coded.

When submitting an article with your study results, it is a good idea to create a table or figure providing a few key examples of how you progressed from the raw data of meaning units, to condensed meaning units, coding, categorisation, and, if included, themes. Providing such a table or figure supports the rigor of your study [1] and is an element greatly appreciated by reviewers and research consumers.

During the analysis process, it can be advantageous to write down your research aim and questions on a sheet of paper that you keep nearby as you work. Frequently referring to your aim can help you keep focused and on track during analysis. Many find it helpful to colour code their transcriptions and write notes in the margins.

Having access to qualitative analysis software can be greatly helpful in organising and retrieving analysed data. Just remember, a computer does not analyse the data. As Jennings [15] has stated, “… it is ‘peopleware,’ not software, that analyses.” A major drawback is that qualitative analysis software can be prohibitively expensive. One way forward is to use table templates such as we have used in this article. (Three analysis templates, Templates A, B, and C, are provided as supplementary online material ). Additionally, the “find” function in word processing programmes such as Microsoft Word (Redmond, WA USA) facilitates locating key words, e.g., in transcribed interviews, meaning units, and codes.

Lessons learnt/key points

From our experience with content analysis we have learnt a number of important lessons that may be useful for the novice researcher. They are:

- • A method description is a guideline supporting analysis and trustworthiness. Don’t get caught up too rigidly following steps. Reflexivity and flexibility are just as important. Remember that a method description is a tool helping you in the process of making sense of your data by reducing a large amount of text to distil key results.

- • It is important to maintain a vigilant awareness of one’s own pre-understandings in order to avoid bias during analysis and in results.

- • Use and trust your own intuition during the analysis process.

- • If possible, discuss and reflect together with other researchers who have analysed the same data. Be open and receptive to new perspectives.

- • Understand that it is going to take time. Even if you are quite experienced, each set of data is different and all require time to analyse. Don’t expect to have all the data analysis done over a weekend. It may take weeks. You need time to think, reflect and then review your analysis.

- • Keep reminding yourself how excited you have felt about this area of research and how interesting it is. Embrace it with enthusiasm!

- • Let it be chaotic – have faith that some sense will start to surface. Don’t be afraid and think you will never get to the end – you will… eventually!

Peer review under responsibility of African Federation for Emergency Medicine.

Appendix A Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001 .

Appendix A. Supplementary data

What Is Qualitative Content Analysis?

Qca explained simply (with examples).

By: Jenna Crosley (PhD). Reviewed by: Dr Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | February 2021

If you’re in the process of preparing for your dissertation, thesis or research project, you’ve probably encountered the term “ qualitative content analysis ” – it’s quite a mouthful. If you’ve landed on this post, you’re probably a bit confused about it. Well, the good news is that you’ve come to the right place…

Overview: Qualitative Content Analysis

- What (exactly) is qualitative content analysis

- The two main types of content analysis

- When to use content analysis

- How to conduct content analysis (the process)

- The advantages and disadvantages of content analysis

1. What is content analysis?

Content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on recorded human artefacts such as manuscripts, voice recordings and journals. Content analysis investigates these written, spoken and visual artefacts without explicitly extracting data from participants – this is called unobtrusive research.

In other words, with content analysis, you don’t necessarily need to interact with participants (although you can if necessary); you can simply analyse the data that they have already produced. With this type of analysis, you can analyse data such as text messages, books, Facebook posts, videos, and audio (just to mention a few).

The basics – explicit and implicit content

When working with content analysis, explicit and implicit content will play a role. Explicit data is transparent and easy to identify, while implicit data is that which requires some form of interpretation and is often of a subjective nature. Sounds a bit fluffy? Here’s an example:

Joe: Hi there, what can I help you with?

Lauren: I recently adopted a puppy and I’m worried that I’m not feeding him the right food. Could you please advise me on what I should be feeding?

Joe: Sure, just follow me and I’ll show you. Do you have any other pets?

Lauren: Only one, and it tweets a lot!

In this exchange, the explicit data indicates that Joe is helping Lauren to find the right puppy food. Lauren asks Joe whether she has any pets aside from her puppy. This data is explicit because it requires no interpretation.

On the other hand, implicit data , in this case, includes the fact that the speakers are in a pet store. This information is not clearly stated but can be inferred from the conversation, where Joe is helping Lauren to choose pet food. An additional piece of implicit data is that Lauren likely has some type of bird as a pet. This can be inferred from the way that Lauren states that her pet “tweets”.

As you can see, explicit and implicit data both play a role in human interaction and are an important part of your analysis. However, it’s important to differentiate between these two types of data when you’re undertaking content analysis. Interpreting implicit data can be rather subjective as conclusions are based on the researcher’s interpretation. This can introduce an element of bias , which risks skewing your results.

2. The two types of content analysis

Now that you understand the difference between implicit and explicit data, let’s move on to the two general types of content analysis : conceptual and relational content analysis. Importantly, while conceptual and relational content analysis both follow similar steps initially, the aims and outcomes of each are different.

Conceptual analysis focuses on the number of times a concept occurs in a set of data and is generally focused on explicit data. For example, if you were to have the following conversation:

Marie: She told me that she has three cats.

Jean: What are her cats’ names?

Marie: I think the first one is Bella, the second one is Mia, and… I can’t remember the third cat’s name.

In this data, you can see that the word “cat” has been used three times. Through conceptual content analysis, you can deduce that cats are the central topic of the conversation. You can also perform a frequency analysis , where you assess the term’s frequency in the data. For example, in the exchange above, the word “cat” makes up 9% of the data. In other words, conceptual analysis brings a little bit of quantitative analysis into your qualitative analysis.

As you can see, the above data is without interpretation and focuses on explicit data . Relational content analysis, on the other hand, takes a more holistic view by focusing more on implicit data in terms of context, surrounding words and relationships.

There are three types of relational analysis:

- Affect extraction

- Proximity analysis

- Cognitive mapping

Affect extraction is when you assess concepts according to emotional attributes. These emotions are typically mapped on scales, such as a Likert scale or a rating scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 is “very sad” and 5 is “very happy”.

If participants are talking about their achievements, they are likely to be given a score of 4 or 5, depending on how good they feel about it. If a participant is describing a traumatic event, they are likely to have a much lower score, either 1 or 2.

Proximity analysis identifies explicit terms (such as those found in a conceptual analysis) and the patterns in terms of how they co-occur in a text. In other words, proximity analysis investigates the relationship between terms and aims to group these to extract themes and develop meaning.

Proximity analysis is typically utilised when you’re looking for hard facts rather than emotional, cultural, or contextual factors. For example, if you were to analyse a political speech, you may want to focus only on what has been said, rather than implications or hidden meanings. To do this, you would make use of explicit data, discounting any underlying meanings and implications of the speech.

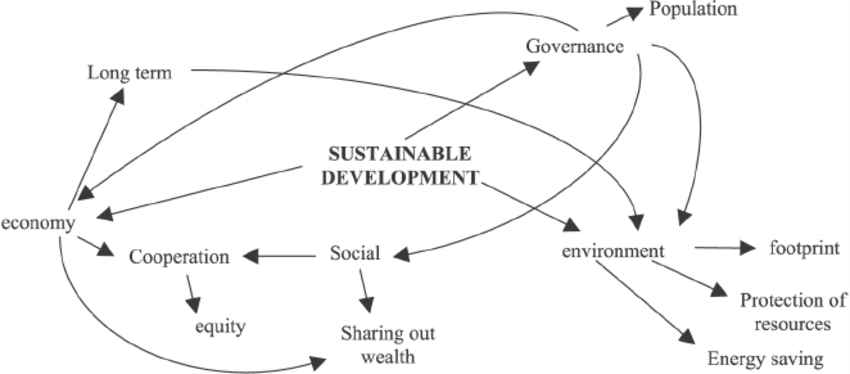

Lastly, there’s cognitive mapping, which can be used in addition to, or along with, proximity analysis. Cognitive mapping involves taking different texts and comparing them in a visual format – i.e. a cognitive map. Typically, you’d use cognitive mapping in studies that assess changes in terms, definitions, and meanings over time. It can also serve as a way to visualise affect extraction or proximity analysis and is often presented in a form such as a graphic map.

To recap on the essentials, content analysis is a qualitative analysis method that focuses on recorded human artefacts . It involves both conceptual analysis (which is more numbers-based) and relational analysis (which focuses on the relationships between concepts and how they’re connected).

Need a helping hand?

3. When should you use content analysis?

Content analysis is a useful tool that provides insight into trends of communication . For example, you could use a discussion forum as the basis of your analysis and look at the types of things the members talk about as well as how they use language to express themselves. Content analysis is flexible in that it can be applied to the individual, group, and institutional level.

Content analysis is typically used in studies where the aim is to better understand factors such as behaviours, attitudes, values, emotions, and opinions . For example, you could use content analysis to investigate an issue in society, such as miscommunication between cultures. In this example, you could compare patterns of communication in participants from different cultures, which will allow you to create strategies for avoiding misunderstandings in intercultural interactions.

Another example could include conducting content analysis on a publication such as a book. Here you could gather data on the themes, topics, language use and opinions reflected in the text to draw conclusions regarding the political (such as conservative or liberal) leanings of the publication.

4. How to conduct a qualitative content analysis

Conceptual and relational content analysis differ in terms of their exact process ; however, there are some similarities. Let’s have a look at these first – i.e., the generic process:

- Recap on your research questions

- Undertake bracketing to identify biases

- Operationalise your variables and develop a coding scheme

- Code the data and undertake your analysis

Step 1 – Recap on your research questions

It’s always useful to begin a project with research questions , or at least with an idea of what you are looking for. In fact, if you’ve spent time reading this blog, you’ll know that it’s useful to recap on your research questions, aims and objectives when undertaking pretty much any research activity. In the context of content analysis, it’s difficult to know what needs to be coded and what doesn’t, without a clear view of the research questions.

For example, if you were to code a conversation focused on basic issues of social justice, you may be met with a wide range of topics that may be irrelevant to your research. However, if you approach this data set with the specific intent of investigating opinions on gender issues, you will be able to focus on this topic alone, which would allow you to code only what you need to investigate.

Step 2 – Reflect on your personal perspectives and biases

It’s vital that you reflect on your own pre-conception of the topic at hand and identify the biases that you might drag into your content analysis – this is called “ bracketing “. By identifying this upfront, you’ll be more aware of them and less likely to have them subconsciously influence your analysis.

For example, if you were to investigate how a community converses about unequal access to healthcare, it is important to assess your views to ensure that you don’t project these onto your understanding of the opinions put forth by the community. If you have access to medical aid, for instance, you should not allow this to interfere with your examination of unequal access.

Step 3 – Operationalise your variables and develop a coding scheme

Next, you need to operationalise your variables . But what does that mean? Simply put, it means that you have to define each variable or construct . Give every item a clear definition – what does it mean (include) and what does it not mean (exclude). For example, if you were to investigate children’s views on healthy foods, you would first need to define what age group/range you’re looking at, and then also define what you mean by “healthy foods”.

In combination with the above, it is important to create a coding scheme , which will consist of information about your variables (how you defined each variable), as well as a process for analysing the data. For this, you would refer back to how you operationalised/defined your variables so that you know how to code your data.

For example, when coding, when should you code a food as “healthy”? What makes a food choice healthy? Is it the absence of sugar or saturated fat? Is it the presence of fibre and protein? It’s very important to have clearly defined variables to achieve consistent coding – without this, your analysis will get very muddy, very quickly.

Step 4 – Code and analyse the data

The next step is to code the data. At this stage, there are some differences between conceptual and relational analysis.

As described earlier in this post, conceptual analysis looks at the existence and frequency of concepts, whereas a relational analysis looks at the relationships between concepts. For both types of analyses, it is important to pre-select a concept that you wish to assess in your data. Using the example of studying children’s views on healthy food, you could pre-select the concept of “healthy food” and assess the number of times the concept pops up in your data.

Here is where conceptual and relational analysis start to differ.

At this stage of conceptual analysis , it is necessary to decide on the level of analysis you’ll perform on your data, and whether this will exist on the word, phrase, sentence, or thematic level. For example, will you code the phrase “healthy food” on its own? Will you code each term relating to healthy food (e.g., broccoli, peaches, bananas, etc.) with the code “healthy food” or will these be coded individually? It is very important to establish this from the get-go to avoid inconsistencies that could result in you having to code your data all over again.

On the other hand, relational analysis looks at the type of analysis. So, will you use affect extraction? Proximity analysis? Cognitive mapping? A mix? It’s vital to determine the type of analysis before you begin to code your data so that you can maintain the reliability and validity of your research .

How to conduct conceptual analysis

First, let’s have a look at the process for conceptual analysis.

Once you’ve decided on your level of analysis, you need to establish how you will code your concepts, and how many of these you want to code. Here you can choose whether you want to code in a deductive or inductive manner. Just to recap, deductive coding is when you begin the coding process with a set of pre-determined codes, whereas inductive coding entails the codes emerging as you progress with the coding process. Here it is also important to decide what should be included and excluded from your analysis, and also what levels of implication you wish to include in your codes.

For example, if you have the concept of “tall”, can you include “up in the clouds”, derived from the sentence, “the giraffe’s head is up in the clouds” in the code, or should it be a separate code? In addition to this, you need to know what levels of words may be included in your codes or not. For example, if you say, “the panda is cute” and “look at the panda’s cuteness”, can “cute” and “cuteness” be included under the same code?