MBA Knowledge Base

Business • Management • Technology

Home » Management Case Studies » Case Study: Wal-Mart’s Distribution and Logistics System

Case Study: Wal-Mart’s Distribution and Logistics System

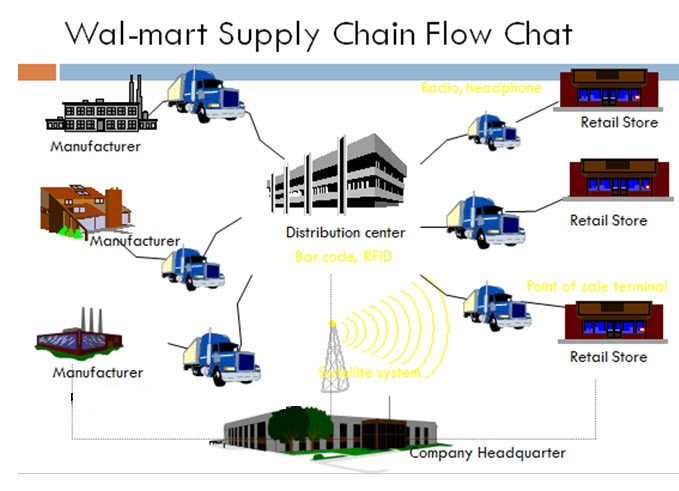

As the world’s largest retailer with net sales of almost $419 billion for the fiscal year 2011, Wal-Mart is considered a “best-in-class” company for its supply chain management practices . These practices are a key competitive advantage that have enabled Wal-Mart to achieve leadership in the retail industry through a focus on increasing operational efficiency and on customer needs. Wal-Mart’s corporate website calls “logistics” and “distribution” the heart of its operation, one that keeps millions of products moving to customers every day of the year.

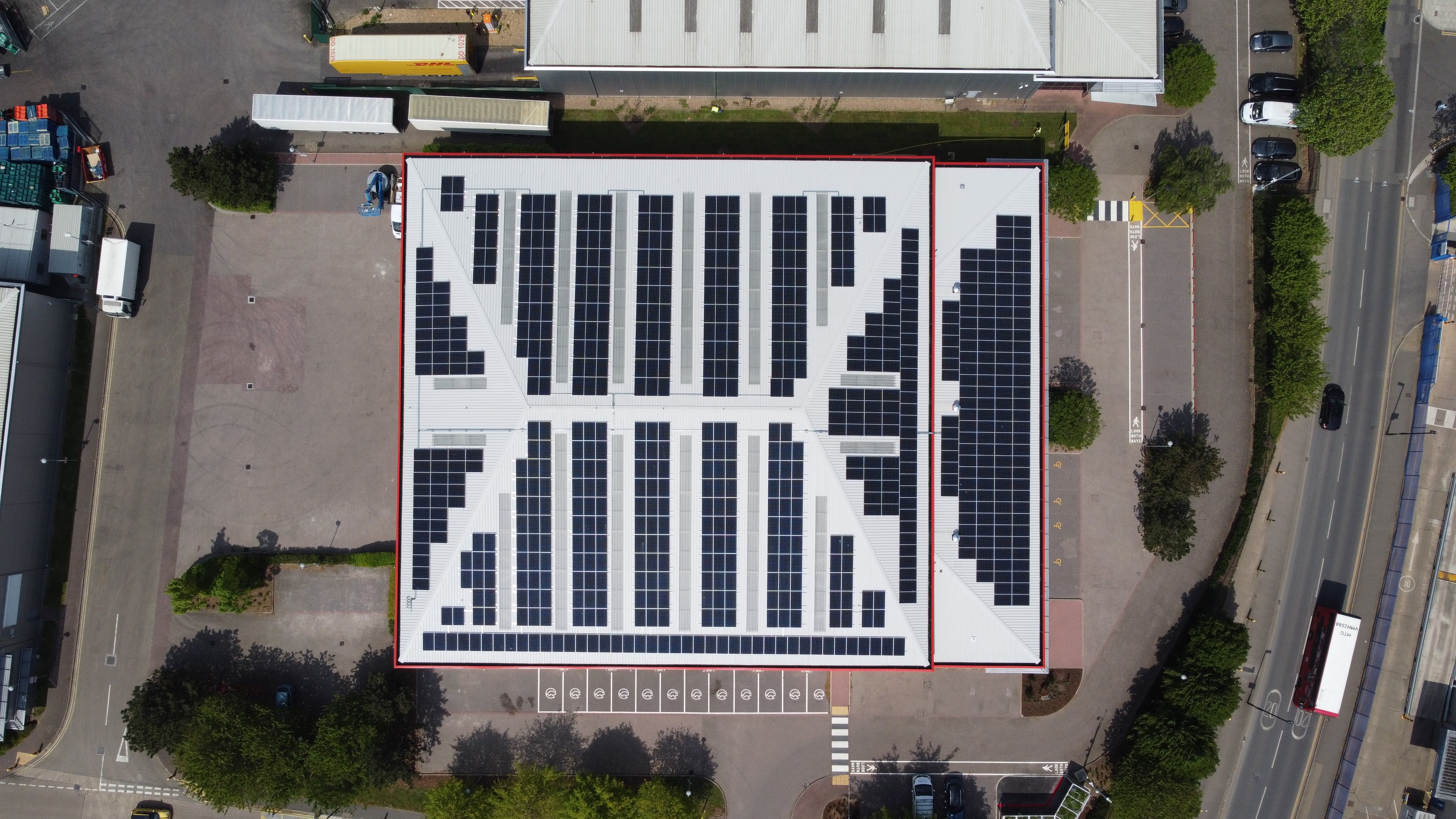

Wal-Mart’s highly-automated distribution centers, which operate 24 hours a day and are served by Wal-Mart’s truck fleet, are the foundation of its growth strategy and supply network. In the United States alone, the company has more than 40 regional distribution centers for import flow and more than 140 distribution centers for domestic flow. When entering a new geographic arena, the company first determines if the area will be able to contain enough stores to support a distribution center. Each distribution center supports between 75 to 100 retail stores within a 250-mile area. Once a center is built, stores are gradually built around it to saturate the area and the distribution network is realigned to maximize efficiencies through a process termed “reoptimization”. The result is a “trickle-down” effect: trucks do not have to travel as far to retail stores to make deliveries, shorter distances reduce transportation costs and lead time, and shorter lead time means holding less safety inventory. If shortages do occur, replenishment can be made more quickly because stores receive daily deliveries from distribution centers.

An important feature of Wal-Mart’s logistics infrastructure was its fast and responsive transportation system. The distribution centers were serviced by more than 3,500 company owned trucks. These dedicated truck fleets allowed the company to ship goods from the distribution centers to the stores within two days and replenish the store shelves twice a week. The truck fleet was the visible link between the stores and distribution centers. Wal-Mart believed that it needed drivers who were committed and dedicated to customer service. The company hired only experienced drivers who had driven more than 300,000 accident-free miles, with no major traffic violation.

Wal-Mart truck drivers generally moved the merchandise-loaded trailers from Wal-Mart distribution centers to the retail stores serviced by each distribution center. These retail stores were considered as customers by the distribution centers. The drivers had to report their hours of service to a coordinator daily. The coordinator scheduled all dispatches depending on the available driving time and the estimated time for travel between the distribution centers and the retail stores. The coordinator informed the driver of his dispatches, either on the driver’s arrival at the distribution center or on his return to the distribution center from the retail store. The driver was usually expected to take a loaded truck trailer from the distribution center to the retail store and return back with an empty trailer. He had to dispatch a loaded truck trailer at the retail store and spend the night there. A driver had to bring the trailer at the dock of a store only at its scheduled unloading time, no matter when he arrived at the store. The drivers delivered the trailers in the afternoon and evening hours and they would be unloaded at the store at nights. There was a gap of two hours between unloading of each trailer. For instance, if a store received three trailers, the first one would be unloaded at midnight (12 AM), the second one would be unloaded at 2 AM and the third one at 4 AM. Although, the trailers were left unattended, they were secured by the drivers, until the store personnel took charge of them at night. Wal-Mart received more trailers than they had docks, due to their large volume of business.

Because Wal-Mart’s fast, responsive transportation operations are such a major part of the company’s successful logistics system, great care is taken in the hiring, training, supervising, and assigning of drivers’ schedules and job responsibilities. From the onset of his retailing career, Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton recognized the importance of hiring experienced people and of building loyalty not only in his customers but also in his employees. The company hires only experienced drivers who have driven more than 300,000 accident-free miles and whom it believes will be committed to customer service. Its retail stores are considered important “customers” of the distribution centers. As stated in the “Private Fleet Driver Handbook” that each driver is given a copy of, drivers are expected to be “polite” and “kind” when dealing with store personnel and others. In addition to containing a driver’s code of conduct, the Private Fleet Driver Handbook gives instructions and rules for following pre-planned travel routes and schedules, the responsible unloading of a truck trailer at a retail store, and the safe-guarding of Wal-Mart’s property. For example, although drivers deliver loaded trailers in the afternoon and evening hours, a trailer can be brought to the store’s docks only at its scheduled unloading time. Because unloading is done at two-hour intervals during the night, a driver is expected to spend the night, returning to the distribution center at a pre-scheduled time with an empty trailer. Coordinators closely monitor the detailed records of each driver’s activities for adherence to rules. Violations are dealt with according to handbook procedures, which include employee education to prevent future occurrences of incorrect actions. By effectively managing every aspect of its transportation operations and treating its drivers fairly, Wal-Mart gets results that are unrivaled in the logistics arena. This philosophy parallels the successful coaching style of New York Giant’s football coach Tom Coughlin who believes that rules are more than just discipline. Rules are a key to consistency, which leads to preparedness, which then leads to proper execution.

To make its distribution process more efficient, Wal-Mart also made use of a logistics technique known as ‘cross-docking.’ In this system, the finished goods were directly picked up from the manufacturing plant of a supplier, sorted out and then directly supplied to the customers. The system reduced the handling and storage of finished goods, virtually eliminating the role of the distribution centers and stores. There were five types of cross-docking.

- Opportunistic Cross docking – In this method of cross docking, the exact information about where the necessary good should be shipped and from where it should be procured and exact quantity which will be sent was necessary. This method of cross docking has allowed the company to ship directly the goods, necessary retail clients, not storing them in warehouse bins or shelves. Opportunistic cross docking could also be used when the warehouse software of management installed by the retailer, has set ready it, that the specific product was ready to moving and could be moved immediately.

- Flow-through Cross docking – In this type of cross docking, there was a constant inflow and outflow of the goods from the distribution center. This type of cross docking was mostly suitable for the perishable goods which had very short interval of time, or the goods which were difficult to be kept in warehouses. This cross docking system was mainly accompanied by supermarkets and other retail discount stores, especially for perishable items.

- Distributor Cross docking – In this type of cross docking, the manufacturer has delivered the goods to directly to retailer. No intermediaries have been involved in this process. It has allowed the retailer to save a major portion of the expenses in the form of storage. As the retailer should not support the distribution center for storage various kinds of the goods, he has helped it to save warehouse costs. The lead time for the delivery of goods from the manufacturer to the consumer was also drastically reduced. However, this method had some disadvantages too. Expenses of transportation both for the manufacturer and for the retailer tended to increase during time when the goods have been required to be transported to different locations several times. Besides, the transportation system should be very fast. Otherwise, the purpose of cross docking has been lost. The transportation system should be also highly responsive and to take the responsibility for delays in delivery of the goods. The retailer was at a greater risk. He has lost that advantage to sharing risks with the manufacturer. This type of cross docking was suitable only for those retailers who had the big distributive network and could be used in situations when goods had to be delivered in a short span of time.

- Manufacturing Cross docking – In Manufacturing cross docking, these cross docking facilities served the factories and acted as temporary and “mini warehouses.” Whenever a manufacturing company required some parts or materials for manufacturing a particular product, it was delivered by the supplier in small lots within a very short span of time, just when it was needed. This helped reduce the transportation and warehouse costs substantially.

- Pre-Allocated Cross Docking – Pre-allocated cross docking is very much like the usual cross-docking, except that in this type of cross docking, the goods are already packed and labeled by the manufacturer and it is ready for shipment to the distribution center from where it is sent to the store. The goods can be delivered by the distribution center directly to the store without opening the pack of the manufacturer and re-packing the goods. The store can then deliver the goods directly to the consumer without any further repacking. Goods received by the distribution center or the store are directly sent into the outbound shipping truck, to be delivered to the consumer, without altering the package of the good. Cross docking requires very close co-ordination and co-operation of the manufacturers, warehouse personnel and the stores personnel. Goods can be easily and quickly delivered only when accurate information is available readily. The information can be managed with the help of Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) and other general sales information.

In cross docking, requisitions received for different goods from a store were converted into purchase or procurement orders. These purchase orders were then forwarded to the manufacturers who conveyed their ability or inability to supply the goods within a particular period of time. In cases where the manufacturer agreed to supply the required goods within the specified time, the goods were directly forwarded to a place called the staging area. The goods were packed here according to the orders received from different stores and then directly sent to the respective customers. To gain maximum out of cross-docking, Wal-Mart had to make fundamental changes in its approach to managerial control . Traditionally, decisions about merchandising, pricing and promotions had been highly centralized and were generally taken at the corporate level. The crossdocking system, however, changed this practice. The system shifted the focus from “supply chain” to the “demand chain,” which meant that instead of the retailer ‘pushing’ products into the system; customers could ‘pull’ products, when and where they needed. This approach placed a premium on frequent, informal cooperation among stores, distribution centers and suppliers with far less centralized control than earlier.

Besides, if the supplier knows also, that for the company it will be incredibly difficult to make proper adjustments to guarantee smooth transition to the different supplier, then they will be less inclined to lower their price as much. It is not, how existing suppliers deal with Wal-Mart; when they see that Wal-Mart has found the supplier who will give them lower price, current suppliers lower their prices accordingly. They know that logistical system of the Wal-Mart can address with transition easily, and consequently they do not receive additional leverage, as it will not be difficult or expensive for Wal-Mart to choose other supplier.

Another reason that Wal-Mart’s prices are so competitive is because they buy in such large quantities that transportation from one end of the supply chain to another is not as expensive for additional units. This aspect of the logistical system does not come from skill or expertise it simply comes from the sheer size of the company, but this is still a factor. On the other hand, the Wal-Mart buys so many supplies from different places throughout the world, that they have the luxury of using bigger trucks and using less fuel to go back and forth. Also if by chance they have to use shipping services to transport material from one location to another, Wal-Mart will give them so much business that they will get huge discounts.

On the whole, the logistical system that Wal-Mart uses is so effective because it is so flexible. This is why Wal-Mart is able to offer things much cheaper than other companies can.

About Wal-mart Stores

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. is the largest retailer in the world, the world’s second-largest company and the nation’s largest nongovernmental employer. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. operates retail stores in various retailing formats in all 50 states in the United States. The Company’s mass merchandising operations serve its customers primarily through the operation of three segments. The Wal-Mart Stores segment includes its discount stores, Supercenters, and Neighborhood Markets in the United States. The Sam’s club segment includes the warehouse membership clubs in the United States. The Company’s subsidiary, McLane Company, Inc. provides products and distribution services to retail industry and institutional foodservice customers. Wal-Mart serves customers and members more than 200 million times per week at more than 8,416 retail units under 53 different banners in 15 countries. With fiscal year 2010 sales of $405 billion, Wal-Mart employs more than 2.1 million associates worldwide. Nearly 75% of its stores are in the United States (“Wal-Mart International Operations”, 2004), but Wal-Mart is expanding internationally. The Group is engaged in the operations of retail stores located in all 50 states of the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Japan, Puerto Rico and the United Kingdom, Central America, Chile, Mexico,India and China.

Related posts:

- Case Study: Wal-Marts Competitive Advantage

- Case Study: Wal-Mart’s Failure in Germany

- Case Study: Business Strategy Analysis of Wal-Mart

- Case Study: An Assessment of Wal-Mart’s Global Expansion Strategy

- Case Study of Walmart: Procurement and Distribution

- Use of Logistics Channel and Public and Private Distribution Facilities – For Material Sources

- Case Study of FedEx: Pioneer of Internet Business in the Global Transportation and Logistics Industry

- Distribution Center Decisions

- Case Study: Strategy of Ryanair

- Case Study: How Netflix Took Down Blockbuster

One thought on “ Case Study: Wal-Mart’s Distribution and Logistics System ”

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses cookies to improve your experience. By viewing our content, you are accepting the use of cookies. To help us insure we adhere to various privacy regulations, please select your country/region of residence. If you do not select a country we will assume you are from the United States. View our privacy policy and terms of use.

- Materials Handling

- Tracking and Tracing

Negotiating With A Chatbot: A Walmart Procurement Case Study

Talking Logistics

MAY 1, 2023

This past February we asked members of our Indago supply chain research community — who are all supply chain and logistics executives from manufacturing, retail, and distribution companies — “Is your company using Artificial Intelligence in its supply chain or logistics operations?”

Distribution Network Cost- A Mini Case Study

Logistics Bureau

SEPTEMBER 7, 2022

You can access a recorded webinar about Distribution Network Costs on this link: [link]. ?. Related articles on this topic have appeared throughout our website, check them out: The 7 Principles of Warehouse and Distribution Centre Design. The Long and Short of Designing a Distribution Network.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Trending Sources

The Logistics of Logistics

- The Lean Thinker

CASE STUDY: Amware Helps Image Skincare Scale Fulfillment to Support Growth

Amware Logistics and Fulfillment

SEPTEMBER 21, 2021

Image Skincare had just one company-run distribution center in South Florida and sought to open another DC in the center of the country to distribute faster with lower shipping costs. After a competitive bid process, Image turned to Amware to fulfill national orders (except for FL and GA) from its Dallas distribution center.

Fulfillment That Makes You Smile: Smile America Partners Case Study

3PL Insights

FEBRUARY 2, 2023

After meeting with many fulfillment providers, Smile America Partners decided to work with Evans Distribution Systems. Download the case study here. The post Fulfillment That Makes You Smile: Smile America Partners Case Study appeared first on Evans Distribution Systems.

A ‘Case Study’ on Distribution Channels

SEPTEMBER 7, 2021

Distribution channels are frequently overlooked as a source of performance enhancement in the Supply Chain. Remember that one of the most important factors to consider when evaluating Distribution Channels would be the cost to serve. It can lead to some excellent alternative Distribution Strategies.

Recent Case Studies Highlight Weber’s Retail Logistics Expertise

West Coast and California Logistics

MAY 30, 2024

Weber Logistics continues to demonstrate excellence in retail logistics through its partnerships with leading brands. Weber’s work with Cuisinart Outdoors and Reduce Everyday illustrate how 3PL services are tailored to meet their diverse needs of clients, ensuring efficiency, scalability, and superior customer satisfaction.

CASE STUDY: Handling a 500% order Spike During Pandemic

JUNE 30, 2020

Most sales are online at publicgoods.com, but in early 2020 the company began national distribution to a major retail chain. As if opening up a new sales channel wasn’t enough of a distribution challenge, something else happened in this timeframe – the Coronavirus pandemic shutdown hit hard.

Watch: Innocent Armor and Jillamy: A Distribution Case Study

Supply Chain Brain

SEPTEMBER 23, 2022

Mike Wang, chief executive officer and founder of Innocent Armor, and Dwayne Shakespeare, director of e-commerce and parcel with Jillamy Inc., explain why Innocent Armor turned to Jillamy for a fulfillment center that could scale in line with the client’s projected growth.

Principles of Distribution Network Design

APRIL 12, 2022

Here is a simple case study on Distribution Networks that illustrates some key principles in Distribution Network Design. ?. Related articles on this topic have appeared throughout our website, check them out: Do You Know the Signs of Poor Distribution Network Design?

A ‘Case Study’ on Distribution Channels and Thinking Outside the Box to Save 18% on Costs

Watch: Cintas & LogistiVIEW: A Case Study

APRIL 17, 2023

Seth Patin, CEO and founder of LogistiVIEW, and David Meyn, senior director of distribution at Cintas, discuss optimizing labor visibility and productivity at the uniform company.

Case Study: Mitigating disruption when COVID-19 closes your distribution center

Logistics Management

JUNE 24, 2020

Learn how an up-to-date optimization model provided one U.S. distributor with a 55% cost avoidance when one of their facilities had to temporarily close because of a worker who contracted COVID-19.

Case Study: InterChange Group

Camelot 3PL Software

NOVEMBER 13, 2020

Background: InterChange Group in Harrisonburg, VA performs cold-storage warehousing and distribution for major U.S. The post Case Study : InterChange Group appeared first on Camelot 3PL Software. food producers and other suppliers around the world.

Case Study: How did GEODIS improve put-away operator productivity by 30%?

SEPTEMBER 18, 2020

The company was proactively looking for ways to enhance their material handling processes in distribution centers when in the fall of 2019, they began researching solutions to make jobs safer while increasing efficiency and throughput. As a 3PL company, GEODIS handles many different operations within its distribution centers.

Warehouse & Distribution Centre Benchmarking Case Study with John Monck

AUGUST 4, 2020

BENCHMARKING IS A FANTASTIC BUSINESS IMPROVEMENT TOOL. John Monck, Manager Consulting at Logistics Bureau will demonstrate its use and explain more… and more about it. Kindly watch the video below: Best Regards, Rob O’Byrne. Email: [email protected]. Phone: +61 417 417 307.

247 Customs Broker

Kindly… The post Warehouse & Distribution Centre Benchmarking Case Study with John Monck appeared first on 24/7 Customs Broker News. BENCHMARKING IS A FANTASTIC BUSINESS IMPROVEMENT TOOL. John Monck, Manager Consulting at Logistics Bureau will demonstrate its use and explain more….and and more about it.

Case Study: Paper Made Easy

FEBRUARY 23, 2021

The post Case Study : Paper Made Easy appeared first on Evans Distribution Systems. We have been able to flex by thousands of tons of inbound and outbound shipments over the years with Evans. They are one of our most trusted and reliable 3PL partners.”.

Flexible Warehousing with Flexe CEO Karl Siebrecht

MARCH 24, 2023

Founded in 2013 and headquartered in Seattle, Flexe brings deep logistics expertise and enterprise-grade technology to deliver innovative eCommerce fulfillment, retail distribution and network capacity programs to the Fortune 500.

Case Study: Container Legs in LNG Innovation

Logistics Business Magazine

NOVEMBER 27, 2019

The post Case Study : Container Legs in LNG Innovation appeared first on Logistics Business® Magazine. The new ConFoot CF model with a capacity of 34 tons was introduced in the summer of 2019, offering extended range of use for tank container operators in particular.

Case Study: The Order Fulfillment Group

AUGUST 12, 2021

Known for its efficiency and quick turnarounds, the third-party logistics provider (3PL) offers comprehensive fulfillment and distribution services that include order entry, accounting, warehousing, and returns receiving to organizations nationwide. Postal Service. The Order Fulfillment Group.

How a Compost Collection Start-Up Went From 15 Customers to Thousands – A Case Study

APRIL 19, 2019

Read our case study on The Compost Crew and learn how better planning has enabled them to manage up to 600 stops per day! The Compost Crew Case Study Download the case study to learn how WorkWave Route Manager played an important role in The Compost Crew’s sustainable success!

Case Study: Reusable Box for Magazines and Newspapers

APRIL 20, 2020

AMP, Belgium’s largest media distributor, was looking for an efficient and reusable packaging solution for the distribution of magazines and newspapers. The distribution of magazines and newspapers to supermarkets, petrol stations and press & bookshops takes place at the crack of dawn, before all outlets are open. The Challenge.

IoT in Logistics “The Maersk Case Study”

Logistics at MPEPS at UPV

MARCH 15, 2021

According to the article “ How IoT can improve the logistic pro ces s ” the internet of things (IoT) provides data, which describes objects “physical assets” for example a good to be transported and distributed worldwide. Photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com.

PepsiCo: Experts in products but struggling in their distribution

MARCH 9, 2021

The distribution system they operated was through exportation of their products to Ukrainian bottling companies, which then sold the products to independent distributors. Sources: Marketing Channels And Logistics: a Case Study Of Pepsi International.

Case Study: How to Keep Your Warehouse Pristine

DECEMBER 9, 2019

Beaches Logistics is a busy warehouse and distribution site in Carlisle, a brand new 40,000 square feet facility that only closes for 5 hours every night. In addition to distributing goods for clients we also provide storage for customers who access the warehouse themselves. This is his story: The Cleaning Issue.

Case Study: From Pick to Shout to Pick to Light

NOVEMBER 26, 2019

The Chilean company has installed Pick to Light for order picking of packaged, long-life products and Put to Light for the distribution of daily fresh pastry products and other food products. “ The post Case Study : From Pick to Shout to Pick to Light appeared first on Logistics Business® Magazine.

Distribution Center Robots: How Robots Continue to Power the Distribution Center

GlobalTranz

APRIL 6, 2018

Spurred by the record-breaking growth of e-commerce and rising labor costs, robots can have a very positive impact in distribution centers when implemented correctly. Why Do Companies Fear Distribution Center Robots and Their Implementation? Anyone who has worked in a distribution center knows that exceptions arise constantly.

Case Study: Loading Bay Technology at High-Spec Business Park

DECEMBER 13, 2018

The park has 500,000 sq ft left to be developed, and the latest project to complete was a campus of five high specification industrial / distribution units. Understanding the requirements of large warehouses and distribution centres, Hörmann was able to provide the site with products from their award-winning range of loading bay technology.

Case Study: Doubling Productivity with SSI Schaefer Automation

Pet supplier Fressnapf opted for a sustainable system concept and SSI Schaefer’s intralogistics competence when extending its European distribution centre. ” The post Case Study : Doubling Productivity with SSI Schaefer Automation appeared first on Logistics Business® Magazine.

Last Mile Delivery Platform: MercuryGate Use Cases and Success Stories

MercuryGate

OCTOBER 17, 2023

Read these case studies to see how MercuryGate’s last-mile delivery platform helps businesses overcome delivery challenges, optimize routes, and enhance customer communication. The post Last Mile Delivery Platform: MercuryGate Use Cases and Success Stories appeared first on MercuryGate International.

Case Study: CKF Systems Robots Pick Fragile Snack Product at High Speed

MARCH 30, 2020

The system is helping them to produce, pack and distribute a steady supply of their product to the UK’s supermarkets. The post Case Study : CKF Systems Robots Pick Fragile Snack Product at High Speed appeared first on Logistics Business® Magazine.

Case Study: Good Day at the Office for System Store Solutions

DECEMBER 11, 2019

This growth has meant change within the business and in July it relocated its warehousing and distribution operation to a brand-new facility in Kempston, Bedfordshire. The post Case Study : Good Day at the Office for System Store Solutions appeared first on Logistics Business® Magazine.

Case Study: Smelling the Coffee with JCB’s Teletruk

JUNE 7, 2019

The company produces and distributes some 6 million litres of milk per week from its processing facility in Acton, West London and operates additional retail distribution sites in Leeds, Manchester, Derby, Coventry, Cardiff, Birmingham and Plympton in Devon. The company’s Acton site operates around-the-clock, seven-days-a-week.

Case Study: STILL RX70 Truck Handles Agri Business

MARCH 19, 2019

Steve Holt (IAE Distribution Manager) commented: “We trialled 10 different suppliers and STILL’s product came out on top in terms of fuel-saving and efficiency. In addition, IAE decided to extend their operation (in the distribution side of the business) to a 2-shift pattern and the truck hours have been increased to reflect this.

Case Study: Marangoni Blackline Performs for Danish Truck Fleet

JULY 31, 2019

It is Marangoni’s recommendation that the RDG101 is utilised on vehicles typically used for regional distribution , like those of Bach & Pedersen, a Danish company with a fleet of 52 trucks and 90 trailers that have been making use of the product in the sizes of 315/60R22,5 and 315/70R22,5.

Case Study: Helly Hansen opts for UniCarriers once more

OCTOBER 1, 2019

Norwegian clothing manufacturer Helly Hansen operates most of its company fleet at its European distribution centre in the Dutch town of Born. Workwear stocks were warehoused at a separate distribution centre in Sweden until 2011, but they are now stored together with sports clothing at the Born EDC. The centre holds a total of 2.5

Sortation Case Study: Prepared for Peak Times

JULY 11, 2018

Austrian postal service Österreichische Post AG has built its new distribution centre in Wernberg, in the southernmost Austrian state of Carinthia. The Austrian postal service has responded to this tough task and opened a new distribution centre in Wernberg, in the state of Carinthia. Up to 30,000 packages are handled on a daily basis.

Case Study: Wanzl Roll Cages Supplied to University Hospital Zurich

MARCH 6, 2019

The construction of the new UHZ Logistics and Service Centre in Schlieren, which supplies the UHZ centre in Zurich as well as the external wards, made it necessary to put in place specially coordinated roll containers for distribution . The organisation found Wanzl Logistics + Industry to be the ideal partner for this task.

Case Study: Customer-Centric Live Logistics Optimization for Large Online Retailer

DECEMBER 31, 2018

The client was one of the largest online home goods retailer in North America with more than 60 million active online users, 10 million hosted products, and 20,000 suppliers. LogiNext optimized their entire logistics movement with optimized carrier handling and high customer (delivery) experience.

Case Study: Roll Out the Barrel for Tailored Materials Handling

NOVEMBER 12, 2019

Following the acquisition of both the Charles Wells Brewing and Beer business and various supply contracts in 2017, Marston’s elected to bring the distribution operation in-house at a new site in West Thurrock. The post Case Study : Roll Out the Barrel for Tailored Materials Handling appeared first on Logistics Business® Magazine.

How Exceptional Companies Grow with Sarah Ahern & Jonathon McKay

SEPTEMBER 15, 2023

Focused on logistics, manufacturing, and distribution channel strategies, Jonathon helps organizations make confident decisions for bold growth. About Jonathon McKay Jonathon McKay is a highly experienced partner at PATH specializing in exceptional growth strategies for the supply chain industry.

MAY 13, 2024

Plus hard-hitting interviews, site visits and case studies with Ocado, Bobcat, the UK Department for Transport, Blue Yonder, Koerber, Kinaxis, Sennder, Bowe, Fortna, Dematic, Beumer, TGW, Clark, RightHand Robotics, Distrisort, Transdek, Fronius, Bonfiglioli, Gather AI and Efaflex.

Case Study: Tooling Up with Storage and Picking System

JULY 4, 2018

Based in Yeovil, Somerset, the organisation operates from a purpose-built distribution centre and its philosophy of providing more than 6,000 tools ex-stock at low prices has earned the company an unrivalled industry reputation. The post Case Study : Tooling Up with Storage and Picking System appeared first on Logistics Business® Magazine.

Case Study: Yale and Forkway Enable Stelrad to Radiate Success

JUNE 18, 2018

As the materials handling equipment supplier to Stelrad for over 15 years, Yale sub-dealer, Forkway, is best placed to advise and guide the company on the most efficient operation in their warehouse and distribution centre. Thanks to the steady growth of the company, there was a need to extend the distribution centre to meet growing demand.

Stay Connected

Join 84,000+ Insiders by signing up for our newsletter

- Participate in Logistics Brief

- Add a Source

- Add a Resource

- 2019 Logistics Brief MVP Awards

- 2020 Logistics Brief MVP Awards

- 2021 Logistics Brief MVP Awards

- 2022 Logistics Brief MVP Awards

- Thu. Jul 11

- Wed. Jul 10

- Tue. Jul 09

- Mon. Jul 08

- Jun 29 - Jul 05

- Supply Chains

- Distribution

- Transportation

- More Topics

Input your email to sign up, or if you already have an account, log in here!

Enter your email address to reset your password. a temporary password will be e‑mailed to you., be in the know on, logistics brief.

Expert insights. Personalized for you.

We organize all of the trending information in your field so you don't have to. Join 84,000+ users and stay up to date on the latest articles your peers are reading.

Get the good stuff

Subscribe to the following Logistics Brief newsletters:

You must accept the Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions to proceed.

You know about us, now we want to get to know you!

Check your mail, we've sent an email to . please verify that you have received the email..

We have resent the email to

Let's personalize your content

Use social media to find articles.

We can use your profile and the content you share to understand your interests and provide content that is just for you.

Turn this off at any time. Your social media activity always remains private.

Let's get even more personalized

Choose topics that interest you., so, what do you do.

Are you sure you want to cancel your subscriptions?

Cancel my subscriptions

Don't cancel my subscriptions

Changing Country?

Accept terms & conditions.

It looks like you are changing your country/region of residence. In order to receive our emails, you must expressly agree. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link at the bottom of our emails.

You appear to have previously removed your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions.

We noticed that you changed your country/region of residence; congratulations! In order to make this change, you must accept the Aggregage Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy. Once you've accepted, then you will be able to choose which emails to receive from each site .

You must choose one option

Please choose which emails to receive from each site .

- Update All Sites

- Update Each Site

Please verify your previous choices for all sites

Sites have been updated - click Submit All Changes below to save your changes.

We recognize your account from another site in our network , please click 'Send Email' below to continue with verifying your account and setting a password.

You must accept the Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions to proceed.

This is not me

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Distribution →

- 25 Jun 2024

- Research & Ideas

How Transparency Sped Innovation in a $13 Billion Wireless Sector

Many companies are wary of sharing proprietary information with suppliers and partners. However, Shane Greenstein and colleagues show in a study of wireless routers that being more open about technology can lead to new opportunities.

- 22 Mar 2024

Open Source Software: The $9 Trillion Resource Companies Take for Granted

Many companies build their businesses on open source software, code that would cost firms $8.8 trillion to create from scratch if it weren't freely available. Research by Frank Nagle and colleagues puts a value on an economic necessity that will require investment to meet demand.

- 12 Dec 2023

COVID Tested Global Supply Chains. Here’s How They’ve Adapted

A global supply chain reshuffling is underway as companies seek to diversify their distribution networks in response to pandemic-related shocks, says research by Laura Alfaro. What do these shifts mean for American businesses and buyers?

- 25 Apr 2023

How SHEIN and Temu Conquered Fast Fashion—and Forged a New Business Model

The platforms SHEIN and Temu match consumer demand and factory output, bringing Chinese production to the rest of the world. The companies have remade fast fashion, but their pioneering approach has the potential to go far beyond retail, says John Deighton.

- 29 Nov 2022

How Much More Would Holiday Shoppers Pay to Wear Something Rare?

Economic worries will make pricing strategy even more critical this holiday season. Research by Chiara Farronato reveals the value that hip consumers see in hard-to-find products. Are companies simply making too many goods?

- 18 Oct 2022

- Cold Call Podcast

Chewy.com’s Make-or-Break Logistics Dilemma

In late 2013, Ryan Cohen, cofounder and then-CEO of online pet products retailer Chewy.com, was facing a decision that could determine his company’s future. Should he stay with a third-party logistics provider (3PL) for all of Chewy.com’s e-commerce fulfillment or take that function in house? Cohen was convinced that achieving scale would be essential to making the business work and he worried that the company’s current 3PL may not be able to scale with Chewy.com’s projected growth or maintain the company’s performance standards for service quality and fulfillment. But neither he nor his cofounders had any experience managing logistics, and the company’s board members were pressuring him to leave order fulfillment to the 3PL. They worried that any changes could destabilize the existing 3PL relationship and endanger the viability of the fast-growing business. What should Cohen do? Senior Lecturer Jeffrey Rayport discusses the options in his case, “Chewy.com (A).”

- 10 Jan 2022

How to Get Companies to Make Investments That Benefit Everyone

Want more organizations to give back to their communities? Frank Nagle says the success of open source software offers an innovative—and unexpected—roadmap for social good. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 19 Jul 2020

- Working Paper Summaries

Open Source Software and Global Entrepreneurship

Does more activity in open source software development lead to increased entrepreneurial activity and, if so, how much, and in what direction? This study measures how participation on the GitHub open source platform affects the founding of new ventures globally.

- 01 Jun 2020

- What Do You Think?

Will Challenged Amazon Tweak Its Retail Model Post-Pandemic?

James Heskett's readers have little sympathy for Amazon's loss of market share during the pandemic. Has the organization lost its ability to learn? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Mar 2019

The Impacts of Increasing Search Frictions on Online Shopping Behavior: Evidence from a Field Experiment

This paper challenges the logic that making it easier for consumers to search across a wide assortment of products is the best strategy for online retailers. Experiments show that adding extra search costs to find discounted items can improve gross margins and sales by increasing the number of items inspected and serving as a self-selecting price discrimination mechanism among customers.

- 18 Oct 2018

How to Use Free Shipping as a Competitive Weapon

Free shipping is an increasingly important tool in the online retailer's marketing arsenal, but profit is lost when not done right, says Donald Ngwe. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Sep 2018

The Hidden Benefit of Giving Back to Open Source Software

Firms that allow their software programmers to "give back" to the open source community on company time gain benefits—even though competitors might benefit too, says Frank Nagle. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Jun 2017

Amazon, Whole Foods Deal a Big Win for Consumers

What does Amazon's $13.4 billion deal for Whole Foods say about the future of retail? Harvard Business School professors Jose Alvarez and Len Schlesinger see good times ahead for consumers as well as both companies. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 06 Jul 2015

Money and Quotas Motivate the Sales Force Best

Bonus programs are effective for motivating sales people, but also costly for companies to maintain. Doug Chung and Das Narayandas study several compensation schemes to see which work best. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 21 May 2015

Incentives versus Reciprocity: Insights from a Field Experiment

Sales force compensation is a key instrument available to firms for motivating and enhancing sales performance. What are the most effective forms of compensation? In a field experiment involving four regional sales forces of a prominent firm in India, the authors examined the impact of conditional and unconditional bonus schemes. Findings from this study provide guidance to firms on how to use conditional and unconditional compensation to enhance sales rep productivity and better manage the achievement of sales forecasts. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 02 Apr 2015

Digital Initiative Summit: The Business of Crowdsourcing

Gaining the community's trust is vital to building a successful business with crowdsourcing. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 17 Mar 2015

Where Did My Shopping Mall Go?

The growing popularity of online shopping is remaking the world of offline shopping—stores are getting smaller, malls are getting scarcer. Rajiv Lal and José Alvarez look ahead five years at our radically transforming shopping experience. Plus: Book excerpt. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 02 Mar 2015

Retail Reaches a Tipping Point—Which Stores Will Survive?

Part 1: The new book Retail Revolution: Will Your Brick and Mortar Store Survive? argues that ecommerce is about to deal severe blows to many familiar store-based brands—even including Walmart. Here's how retailers can fight back, according to Rajiv Lal, José Alvarez, and Dan Greenberg. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 29 Sep 2014

Why Do Outlet Stores Exist?

Created in the 1930s, outlet stores allowed retailers to dispose of unpopular items at fire-sale prices. Today, outlets seem outmoded and unnecessary—stores have bargain racks, after all. Donald K. Ngwe explains why outlets still exist. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 08 Sep 2014

The Strategic Way To Hire a Sales Team

The equivalent of an entire sales force is replaced at many firms every four years, so it's critical that go-to-market initiatives remain tied to strategic goals. Frank Cespedes explains how in his book, Aligning Strategy and Sales. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

Helping Distributors Make More Money

Value-added resale partners.

Build relationships with your customers by providing tools for taking on distribution’s greatest challenges.

Integration Partners

Connect the best application options the ERP world has to offer. Integrate with the best and brightest organizations in distribution to cover all of your needs, and more.

CASE STUDIES

See how these distributors harnessed process control and data visibility to take their business operations to new heights. Each story packs industry best practices, relevant for businesses of all sizes and across industries.

Steiner Tractor Parts

Steiner Tractor Supply was ready to modernize and streamline its order management system. Manual input and slow reporting were limiting the company’s potential. Learn how they moved from tracking every order on paper to automating processes and growing their business with SalesPad by Cavallo.

Geckobrands

To encourage their customers to carry additional products, geckobrands needed to prove that unexpected products or styles were top sellers for many customers. Learn how Cavallo helped them leverage their existing data to drive sales.

Lightbulbs.com

LightBulbs.com needed a credit card gateway that was reliable and could scale with their growing business. Learn how they've supercharged their online business with the SalesPad and Square integration.

ExpressPoint

After an acquisition, ExpressPoint needed a single distribution management system that could handle its legacy repair business as well as its new sales business. Learn why it chose SalesPad by Cavallo.

Miller Welding Supply

Maintaining Miller Welding Supply’s legacy distribution management system took three employees five to six hours per day. Learn how SalesPad by Cavallo cut that overhead to improve the company’s speed and flexibility.

By working with teams from Admiral Consulting and Cavallo, Krowne overcame these obstacles and recognized transformative results.

By choosing a solution that combined flexibility, ease of use, and reliability, Bon Chef established new processes that led to scalable growth.

Chadwell Supply

As the top supplier of maintenance and flooring products in the United States, Chadwell Supply needed an Operational ERP platform that could handle its growing business.

BlenderBottle

To keep up with skyrocketing sales, BlenderBottle needed a software upgrade. Flexibility in a new solution was a must, one that could grow with the company for years to come.

Picnic Time Family of Brands

Frustrated by its previous software’s lack of flexibility, Picnic Time was in the market for a solution that could keep its order processing moving as the company continued to grow.

Hoy Shoe Co

Find out why SalesPad was the answer to Hoy Shoe Co’s® pursuit of perfect customer service.

Regal Fabrics

Before Regal Fabrics implemented SalesPad, it struggled with an order processing system that required clicking among multiple different screens, with little to no visibility over its inventory. Now, order processing is free from worries about inventory status.

The Handi-Craft Company

Toy manufacturer-turned-baby product distributor, the Handi-Craft Company moved to Cavallo for its user-friendly interface — but stayed for major efficiency improvements.

Ohio Power Tool

Ohio Power Tool turned to SalesPad by Cavallo for streamlining its order management processes, improving inventory management, and creating workflows for every business process.

National Band Saw Company

The National Band Saw Company turned to SalesPad by Cavallo when it needed a software solution that was easy to work with, could handle complex shipping demands, and didn’t compromise on power or scope.

Key Surgical

Key Surgical is a Minneapolis, Minnesota-based manufacturer and distributor of sterile processing and operating room supplies. With SalesPad added to their on-premises order-to-cash cycle strategy, the company was able to extend the life of its Dynamics GP investment significantly.

Dental City

While searching for an improvement on the company’s old system, Dental City was introduced to both Microsoft Dynamics GP and SalesPad by Cavallo®, which provided additional power and more user-friendly options for managing the company's order-to-cash cycle.

SEE THE FUTURE OF DISTRIBUTION

- Cavallo for BC

- SalesPad for GP

- Professional Services

- Cavallo Support

- Become a Strategic Partner

- Partner Lead Registration

- Case Studies

- Fact Sheets

- White Papers

- Events Calendar

- Agreements / Legal

3351 Claystone Street SE, Suite 100, Grand Rapids, MI 49546

616.245.1221 800.935.5660

- Skip to content.

- Jump to Page Footer.

Strategic expansion: Canadian companies' roadmap to US capital success

Our latest guide will give you direct-application tools to help tap into the US funding market.

Case study: Dell—Distribution and supply chain innovation

Read the highlights

- Cutting out the middleman can work very well.

- Forgoing the retail route can increase customer value.

- Re-examine & improve efficiency for process/operations.

- Use sales data and customer feedback to get ahead of the curve.

In 1983, 18-year-old Michael Dell left college to work full-time for the company he founded as a freshman, providing hard-drive upgrades to corporate customers. In a year’s time, Dell’s venture had $6 million in annual sales. In 1985, Dell changed his strategy to begin offering built-to-order computers. That year, the company generated $70 million in sales. Five years later, revenues had climbed to $500 million, and by the end of 2000, Dell’s revenues had topped an astounding $25 billion. The meteoric rise of Dell Computers was largely due to innovations in supply chain and manufacturing, but also due to the implementation of a novel distribution strategy. By carefully analyzing and making strategic changes in the personal computer value chain, and by seizing on emerging market trends, Dell Inc. grew to dominate the PC market in less time than it takes many companies to launch their first product.

No more middleman: Dell started out as a direct seller, first using a mail-order system, and then taking advantage of the Internet to develop an online sales platform. Well before use of the Internet went mainstream, Dell had begun integrating online order status updates and technical support into their customer-facing operations. By 1997, Dell’s Internet sales had reached an average of $4 million per day . While most other PCs were sold preconfigured and pre-assembled in retail stores, Dell offered superior customer choice in system configuration at a deeply discounted price, due to the cost-savings associated with cutting out the retail middleman. This move away from the traditional distribution model for PC sales played a large role in Dell’s formidable early growth. Additionally, an important side-benefit of the Internet-based direct sales model was that it generated a wealth of market data the company used to efficiently forecast demand trends and carry out effective segmentation strategies. This data drove the company’s product development efforts and allowed Dell to profit from information on the value drivers in each of its key customer segments.

Virtual integration: On the manufacturing side, the company pursued an aggressive strategy of “virtual integration.” Dell required a highly reliable supply of top-quality PC components, but management did not want to integrate backward to become its own parts manufacturer. Instead, the company sought to develop long-term relationships with select, name-brand PC component manufacturers. Dell also required its key suppliers to establish inventory hubs near its own assembly plants. This allowed the company to communicate with supplier inventory hubs in real time for the delivery of a precise number of required components on short notice. This “just-in-time,” low-inventory strategy reduced the time it took for Dell to bring new PC models to market and resulted in significant cost advantages over the traditional stored-inventory method. This was particularly powerful in a market where old inventory quickly fell into obsolescence. Dell openly shared its production schedules, sales forecasts and plans for new products with its suppliers. This strategic closeness with supplier partners allowed Dell to reap the benefits of vertical integration, without requiring the company to invest billions setting up its own manufacturing operations in-house.

Innovation on the assembly floor: In 1997, Dell reorganized its assembly processes. Rather than having long assembly lines with each worker repeatedly performing a single task, Dell instituted “manufacturing cells.” These “cells” grouped workers together around a workstation where they assembled entire PCs according to customer specifications. Cell manufacturing doubled the company’s manufacturing productivity per square foot of assembly space, and reduced assembly times by 75%. Dell combined operational and process innovation with a revolutionary distribution model to generate tremendous cost-savings and unprecedented customer value in the PC market. The following are some key lessons from the story of Dell’s incredible rise:

1. Disintermediation (cutting out the middleman): Deleting a player in the distribution chain is a risky move, but can result in a substantial reduction in operating costs and dramatically improved margins. Some companies that have surged ahead after they eliminated an element in the traditional industry distribution chain include:

- Expedia (the online travel site that can beat the rates of almost any travel agency, while giving customers more choice and more detailed information on their vacation destination)

- ModCloth (a trendy virtual boutique with no bricks-and-mortar retail outlets to drive up costs)

- PropertyGuys.com (offers a DIY kit for homeowners who want to sell their houses themselves)

- iTunes (an online music purchasing platform that won’t have you sifting through a jumble of jewel cases at your local HMV)

- Amazon.com (an online sales platform that allows small-scale buyers and sellers to access a broad audience without the need for an expensive storefront or a custom website)

- Netflix (the no-late-fees online video rental company that will ship your chosen video rentals right to your door)

2. Enhancing customer value: Forgoing the retail route allowed Dell to simultaneously improve margins while offering consumers a better price on their PCs. This move also gave customers a chance to configure PCs according to their specific computing needs. The dramatic improvement in customer value that resulted from Dell’s unique distribution strategy propelled the company to a leading market position.

3. Process and operations innovation: Michael Dell recognized that “the way things had always been done” wasn’t the best or most efficient way to run things at his company. There are countless examples where someone took a new look at a company process and realized that there was a much better way to get things done. It is always worth re-examining process-based work to see if a change could improve efficiency. This is equally true whether you’re a company of five or 500.

4. Let data do the driving: Harnessing the easily accessible sales and customer feedback data that resulted from online sales allowed Dell to stay ahead of the demand curve in the rapidly evolving PC market. Similarly, sales and feedback data were helpful in discovering new ways to enhance customer value in each of Dell’s key customer segments. Whether your company is large or small, it is essential to keep tabs on metrics that could reveal emerging trends, changing attitudes, and other important opportunities for your company.

See additional learning materials for distribution .

Summary: Dell combined operational and process innovation with a revolutionary distribution model to generate tremendous cost-savings and unprecedented customer value in the PC market.

Read next: customer discovery: identifying effective distribution channels for your startup.

Strickland, T. (1999). Strategic Management, Concepts and Cases . McGraw Hill College Division: New York.

Should startups build distribution channels or sell products directly?

Customer discovery: identifying effective distribution channels for your startup, sign up for our monthly startup resources newsletter about building high-growth companies..

- Enter your email *

You may unsubscribe at any time. To find out more, please visit our Privacy Policy .

This site uses cookies to improve your experience. By viewing our content, you are accepting the use of cookies. To help us insure we adhere to various privacy regulations, please select your country/region of residence. If you do not select a country we will assume you are from the United States. View our privacy policy and terms of use.

- Inventory Management Software

- Forecasting

- Sustainability

- Supply Chain Visibility

Negotiating With A Chatbot: A Walmart Procurement Case Study

Talking Logistics

MAY 1, 2023

This past February we asked members of our Indago supply chain research community — who are all supply chain and logistics executives from manufacturing, retail, and distribution companies — “Is your company using Artificial Intelligence in its supply chain or logistics operations?”

Distribution Network Cost- A Mini Case Study

Logistics Bureau

SEPTEMBER 7, 2022

You can access a recorded webinar about Distribution Network Costs on this link: [link]. ?. Related articles on this topic have appeared throughout our website, check them out: The 7 Principles of Warehouse and Distribution Centre Design. The Long and Short of Designing a Distribution Network.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Trending Sources

Logistics Viewpoints

The Logistics of Logistics

- Enchange Supply Chain Consultancy

- Enterra Insights

A ‘Case Study’ on Distribution Channels

SEPTEMBER 7, 2021

Distribution channels are frequently overlooked as a source of performance enhancement in the Supply Chain. Remember that one of the most important factors to consider when evaluating Distribution Channels would be the cost to serve. It can lead to some excellent alternative Distribution Strategies.

Supply Chain Case Study: the Executive's Guide

Supply Chain Opz

JUNE 1, 2014

Analysis of case study is certainly one of the most popular methods for people from business management background. In order to accelerate the learning, this article has gathered 20+ most sought-after supply chain case studies , analyzed/categorized them by industry and the findings are presented.

Case Study: DSV Implements a Single-Instance Control Tower with a Global Footprint

Advertisement

DSV is one of the biggest names in transport and logistics , operating in over 90 countries with a global network of over 75,000 employees. Supporting inbound freight management, outbound flows, domestic distribution , and storage and value-added services would require all three of DSV’s multi-national business units to participate.

AI in the Retail Industry: Benefits, Case Studies & Examples

MARCH 27, 2024

The Evolution of Retail Supply Chain & Logistics : A Pre-AI Overview In the pre-AI era, the retail sector was markedly different, especially since the traditional supply chain and logistics models were largely driven by manual labor. This has made deliveries faster. Another way of ensuring greater customer satisfaction!

AI in the Food Industry: Case Studies, Challenges & Future Trends

MARCH 28, 2024

Integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) within different segments of the Food Industry, including transportation and logistics , production planning, quality control, and others has kicked off revolutionary transformations. Energy-efficient processing and distribution have minimal environmental impact.

A Case Study in Closed-Loop Operational Management

NOVEMBER 19, 2014

As I’ve said before, the biggest challenge facing supply chain and logistics executives today is not managing change, because that’s always been the norm in supply chain management, but managing the rapid pace of change. In a recent webcast hosted by Logistics Management and sponsored by Solvoyo , I had the opportunity to interview Orhan Da?l?o?lugil,

Principles of Distribution Network Design

APRIL 12, 2022

Here is a simple case study on Distribution Networks that illustrates some key principles in Distribution Network Design. ?. Related articles on this topic have appeared throughout our website, check them out: Do You Know the Signs of Poor Distribution Network Design?

CEVA Logistics Drives Agile, Multi-Leg Inbound Flows for Tech Company

CEVA Logistics , a global leader in third-party logistics , was contracted to help a technology company manage its complex supply chain, supporting B2B, B2C, and reverse flows across multi-leg transport.

Cross Docking 101: What, Why and How? [with case studies]

SEPTEMBER 23, 2021

Cross docking is an option to consider if you’re thinking about ways to streamline your supply chain – it’s a popular distribution system for fast-moving consumer goods, but can be used in a variety of other industries. This removes the ‘storage’ element of warehousing logistics , and saves on costs, warehousing space, time and labour.

A ‘Case Study’ on Distribution Channels and Thinking Outside the Box to Save 18% on Costs

Distribution Center Robots: How Robots Continue to Power the Distribution Center

GlobalTranz

APRIL 6, 2018

Spurred by the record-breaking growth of e-commerce and rising labor costs, robots can have a very positive impact in distribution centers when implemented correctly. As explained by Clint Raiser of Logistics Viewpoints , e-commerce retail sales have grown at 15% annually, doubling in size since 2012. Measure performance.

TMS for SMB: A Case Study with Carhartt

OCTOBER 19, 2016

Rapid growth, coupled with new market segments and channels (including ecommerce), prompted Carhartt to embark on a multi-million dollar upgrade of its distribution center, which included investments in warehouse management and transportation management solutions. Is SMB defined by a company’s annual revenues?

Judging Supply Chain Improvement: Campbell Soup Case Study

Supply Chain Shaman

AUGUST 11, 2014

Our approach simply breaks accountabilities and goals across the areas of Manufacturing, Logistics /Network Optimization and Ingredients/Packaging. We now have the ability to focus more on materials management and suppliers upstream, and distribution and customer solutions downstream, to drive optimization. What have you learned?

Fast Track Your Logistics Career: Expert Training with SCMDOJO

JUNE 11, 2024

Are you ready to excel in logistics management? The SCMDOJO Logistics Management Track is your ultimate logistics training pathway. It’s designed to equip you with the skills and knowledge needed to thrive in the logistics industry. Visit Website to Read Full Program Why SCMDOJO Logistics Track is Unique?

Delivering Green: Three Case Studies in Low-Carbon Logistics

MIT Supply Chain

APRIL 29, 2013

Caterpillar is the subject of one of three case studies that show how supply chain management can support both environmental and financial goals. Here are three case studies that offer clear, irrefutable evidence that sustainability and profitability can be compatible in the supply chain domain.

A Case Study in Reverse Logistics Optimization!

Supply Chain Game Changer

NOVEMBER 23, 2018

Check out What Exactly Is Reverse Logistics ? The OEM turned over management of one of the most critical, high-volume segments of its reverse logistics program—the processor business—saving the manufacturer millions of dollars each year; reducing excess inventory; increasing same-day, on-time ship rates; and improving customer satisfaction.

Recent Case Studies Highlight Weber’s Retail Logistics Expertise

West Coast and California Logistics

MAY 30, 2024

Weber Logistics continues to demonstrate excellence in retail logistics through its partnerships with leading brands. Weber’s work with Cuisinart Outdoors and Reduce Everyday illustrate how 3PL services are tailored to meet their diverse needs of clients, ensuring efficiency, scalability, and superior customer satisfaction.

The Critical Path: Navigating Supply Chain Efficiency in the Oil Industry

JUNE 27, 2024

Distribution : Transporting oil products to various markets. How Does Automation Enhance Production and Distribution ? What Are the Logistical Challenges in the Oil Industry? How Do Seasonal Weather Patterns Affect Transportation and Distribution ? Extraction : Drilling and pumping oil from underground.

Importance of Digitalisation to Improve Supply Chains: Helping Businesses Navigate Through Supply Chain Disruptions

The Logistics & Supply Chain Management Society

AUGUST 19, 2022

IoT is making a mark on more and more industries, including logistics . Logistics companies are also leveraging IoT and automation to create more efficient processes. In logistics , this differs significantly from the use of IoT in other industries. In logistics , this differs significantly from the use of IoT in other industries.

How Exceptional Companies Grow with Sarah Ahern & Jonathon McKay

SEPTEMBER 15, 2023

Focused on logistics , manufacturing, and distribution channel strategies, Jonathon helps organizations make confident decisions for bold growth. The Logistics of Logistics Podcast If you enjoy the podcast, please leave a positive review, subscribe, and share it with your friends and colleagues. The Greenscreens.ai

Adexa is Recipient of 2024 Top Supply Chain Projects Award

JUNE 17, 2024

The past 12 months has seen companies within the supply chain and logistics space upgrade, enhance, adopt and adapt in order to achieve greater efficiency along the chain. Supply & Demand Chain Executive and sister publication Food Logistics also operate SCN Summit and Women in Supply Chain Forum.

Free Trade Zone – Is Your 3PL Giving You All the Warehouse and Distribution Cost Savings You Deserve?

ModusLink Corporation

FEBRUARY 8, 2023

Fulfillment Free trade zones, or FTZs, are controlled places in a country that offer warehouse and distribution services for goods from foreign markets, excluding them from paying taxes on those goods. Managing a free trade zone can impact warehouse and distribution operations. The answer, unfortunately, is only sometimes yes.

Supply Chain Risk Management: Revisiting Ericsson

SCM Research

JUNE 29, 2020

Norrman & Jansson’s (2004) case study on Ericsson’s supply chain risk management (SCRM) practices is definitely part of the canon of SCM literature. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. After 15 years, it was time for an update. Norrman, A. & & Wieland, A.

Next Generation Supply Chain Risk Management: A Case Study

DECEMBER 16, 2015

A case in point is offered by AGCO. AGCO is a global leader in the design, manufacture and distribution of a wide range of agricultural equipment. We are entering an era where it is becoming possible to detect supply chain risks much more quickly.

Retail Delivery Trends with Matt Schultz

OCTOBER 21, 2022

Matt is Vice President of Logistics Partnerships at OneRail , an Orlando-based last mile transportation visibility solution providing shippers with Amazon-level dependability and speed. Matt Schultz is Vice President of Logistic Partnerships at OneRail. Premier Pet Case Study . The Logistics of Logistics Podcast.

5 Logistics Best Practices

DECEMBER 2, 2021

These logistics best practices will help businesses of all sizes turn their supply chain into a revenue driver for their business. Prioritizing logistics and supply chain has become a top prior ity for many businesses recovering from recent supply chain disruptions and volatile consumer demand. Logistics Best Practice #4: Plan Ahead.

Top Talking Logistics Posts & Episodes (Q3 2017)

NOVEMBER 7, 2017

Before You Hire a Logistics Data Scientist. The Mind-Boggling Complexities of Food Distribution (Why Optimization is Critical). 3 Steps to Achieving Predictive Logistics . Using Intelligence Over Scale: The Power of AI and Machine Learning in Supply Chain and Logistics . A Case Study in Project Logistics .

A New Model for Grocery Delivery with Sean Coakley

NOVEMBER 19, 2021

Sean is the Chief Commercial Officer of Capstone Logistics , a leading provider of technology-enabled warehouse services, freight management, and last mile distribution solutions. He is responsible for helping the company continue its rapid growth across its end-to-end logistics services offering. About Capstone Logistics .

Best Logistics Management Software: Everything You Need to Know Before Making a Purchase Decision

MAY 3, 2024

As we step into 2024, the world of logistics isn’t what it used to be. Everything is connected – what happens in one part of the supply chain can shake things up in logistics , and the other way around. That is why logistics management software (LMS) is so much more today than what it used to be. We’ve all been witness to this!

Restructuring Global Value Chains & Tariff Reduction – A Continuous Evolution for Supply Chains

Feature Article by Dr. Raymon Krishnan – President at the Logistics and Supply Chain Management Society. Owning sound data is crucial to planning optimal shipping routes, locating distribution centers and warehouses, and forecasting revenue volumes and other trends. MORE FROM THIS EDITION.

Best AI Tools for Supply Chain and Logistics: The Ultimate Guide for 2024

APRIL 30, 2024

Exploring the world of AI tools for supply chain and logistics can be quite overwhelming. That’s why we put together this guide – to help you get a glimpse of the best AI tools for supply chain and logistics , how to implement these tools, what to take care of and more. Best AI Tools for Supply Chain and Logistics 1.

Leveraging Cold Chain Logistics Visibility for COVID-19 Vaccine

FEBRUARY 4, 2021

Let's explore the logistics case study of one of the world’s largest pharma companies, the story of how this US-headquartered, globally present pharma giant improved teamwork in their logistics and is now confidently shipping COVID-19 vaccines using cold chain logistics visibility.

11th annual Cold Chain Distribution Conference and Exhibition

Supply Chain Movement

JUNE 20, 2016

11 th annual Cold Chain Distribution Conference and Exhibition. Following the fruitful discussions in 2015, SMi’s annual Cold Chain Distribution conference will bring back lively debates and industry updates to London, offering the best platform for delegates to stay ahead of this lucrative market! Date: 12-13 December 2016.

Lull Case Study: Order Fulfillment that Doesn’t Keep You Up at Night

OCTOBER 11, 2018

Get the PDF of Lull’s case study >> Challenges to Order Fulfillment. Limited Options: It didn’t make sense to continue with only dropshipping, but signing a long-term contract with a third-party logistics provider (3PL) wasn’t the right fit. They make it possible to solve traditional logistics challenges.”.

Basic Introduction on Supply Chain and Logistics Benchmarking

OCTOBER 13, 2020

Robobyrne: Warehouse & Distribution Centre Benchmarking Case Study . Also, we have a recorded webinar on this topic. You can access it here: [link]. Related articles on this topic have appeared throughout our websites, why not check them out? Supply Chain Secrets: One Of The Best KPI Ever.

Strong Supply Chains Required For an Economic Rebound: Six Steps To Take

APRIL 15, 2020

No doubt about it, we are characters in a supply chain case study searching to define a new normal. Today, we find ourselves in the middle of a risk management case study . News coverage showcases the differences between logistics and supply chain management. Expect border friction and logistics to be an issue.

Temperature Controlled Logistics leadership forum – DACH – 2016

JULY 20, 2016

Temperature Controlled Logistics leadership forum – DACH – 2016. Bringing together industry leaders from across logistics , quality, supply chain and distribution the brand new Temperature Controlled Logistics Leaders Forum takes a hard look at core challenges and best practices to take your TCL strategy to the next level!

Rockwell Automation: A Case Study in Supply Chain Excellence

DECEMBER 4, 2018

In his role, Ernest owns strategic sourcing, materials planning, customer care, and logistics operations globally. This methodology was especially crucial for Rockwell Automation global customers, whose impact was notable since it didn’t have the benefit of their distribution network. He is a humble and quiet leader.

ROI in Supply Chain: Achieving Rapid Value with ThroughPut AI in Just 90 Days

MAY 22, 2024

Download this case study to learn how ThroughPut enabled the manufacturer to: Enhance product mix and segmentation while reducing excess inventory Identify optimal stock levels and reduce working capital Drive 17.8% Global Cement Manufacturer Achieves $1.5M improvement in yield margins 2.

Book Review: Logistics Clusters-Delivering Value and Driving Growth

OCTOBER 24, 2012

Case Studies . Book Review: Logistics Clusters-Delivering Value and Driving Growth. Recently, Ive found the new book called " Logistics Clusters: Delivering Value and Driving Growth ". Recently, Ive found the new book called " Logistics Clusters: Delivering Value and Driving Growth ". Author of the Book.

Blockchain in Supply Chain: 2 Ethereum-Based Projects That Demonstrate How Blockchain Can Improve Supply Chains

FEBRUARY 6, 2018

Otherwise known as a distributed ledger, the automatic recording of data into the blockchain allows for cryptocurrencies such as Ethereum or Bitcoin to serve as way more than just a store of value. It’s still early days, but there are already two Ethereum-based projects that address some of the major problems that hamper logistics .

Supply Chain Spotlight on Mexico: Takeaways from Logistic Summit & Expo 2015

APRIL 6, 2015

A clear sign that Mexico is currently in the supply chain spotlight was last month’s Logistic Summit & Expo 2015 in Mexico City, which attracted over 10,000 attendees and almost 200 exhibitors, including leading 3PLs, software vendors, and other supply chain and logistics companies from both the United States and Mexico.

Stay Connected

Join 136,000+ Insiders by signing up for our newsletter

- Participate in Supply Chain Brief

- How to achieve six-figure benefits from digitizing paper-based supply chain operation

- 2019 Supply Chain Brief Summer Reading List

- Stay At Home Reading List

- Add a Source

- Add a Resource

- 2018 Supply Chain Brief MVP Awards

- 2019 Supply Chain Brief MVP Awards

- 2020 Supply Chain Brief MVP Awards

- 2021 Supply Chain Brief MVP Awards

- 2022 Supply Chain Brief MVP Awards

- Thu. Jul 11

- Wed. Jul 10

- Tue. Jul 09

- Mon. Jul 08

- Jun 29 - Jul 05

- Warehousing

- Procurement

- Transportation

- Supply Chain

- More Topics

Input your email to sign up, or if you already have an account, log in here!

Enter your email address to reset your password. a temporary password will be e‑mailed to you., be in the know on.

Supply Chain Brief

Expert insights. Personalized for you.

We organize all of the trending information in your field so you don't have to. Join 136,000+ users and stay up to date on the latest articles your peers are reading.

Get the good stuff

Subscribe to the following Supply Chain Brief newsletters:

You must accept the Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions to proceed.

You know about us, now we want to get to know you!

Check your mail, we've sent an email to . please verify that you have received the email..

We have resent the email to

Let's personalize your content

Use social media to find articles.

We can use your profile and the content you share to understand your interests and provide content that is just for you.

Turn this off at any time. Your social media activity always remains private.

Let's get even more personalized

Choose topics that interest you., so, what do you do.

Are you sure you want to cancel your subscriptions?

Cancel my subscriptions

Don't cancel my subscriptions

Changing Country?

Accept terms & conditions.

It looks like you are changing your country/region of residence. In order to receive our emails, you must expressly agree. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link at the bottom of our emails.

You appear to have previously removed your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions.

We noticed that you changed your country/region of residence; congratulations! In order to make this change, you must accept the Aggregage Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy. Once you've accepted, then you will be able to choose which emails to receive from each site .

You must choose one option

Please choose which emails to receive from each site .

- Update All Sites

- Update Each Site

Please verify your previous choices for all sites

Sites have been updated - click Submit All Changes below to save your changes.

We recognize your account from another site in our network , please click 'Send Email' below to continue with verifying your account and setting a password.

You must accept the Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions to proceed.

This is not me

A ‘Case Study’ on Distribution Channels

Sep 21, 2021 | Case Studies , Chain of Responsibility , Distribution Channels , Logistics , Supply Chain , Videos , Vlogs | 2 comments

Distribution channels are frequently overlooked as a source of performance enhancement in the Supply Chain. But if you think outside the box, your company could save 18% annually.

Remember that one of the most important factors to consider when evaluating Distribution Channels would be the cost to serve. It can lead to some excellent alternative Distribution Strategies.

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published on September 08, 2021, under the title “A ‘Case Study’ on Distribution Channels and Thinking Outside the Box to Save 18% on Costs” on Logistics Bureau’s website.

Nice dickie

Thanks, Demetrius!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *