- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Qualitative Research Methods

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Qualitative Data Collection: What it is + Methods to do it

Qualitative data collection is vital in qualitative research. It helps researchers understand individuals’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors in a specific context.

Several methods are used to collect qualitative data, including interviews, surveys, focus groups, and observations. Understanding the various methods used for gathering qualitative data is essential for successful qualitative research.

In this post, we will discuss qualitative data and its collection methods of it.

Content Index

What is Qualitative Data?

What is qualitative data collection, what is the need for qualitative data collection, effective qualitative data collection methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative data collection.

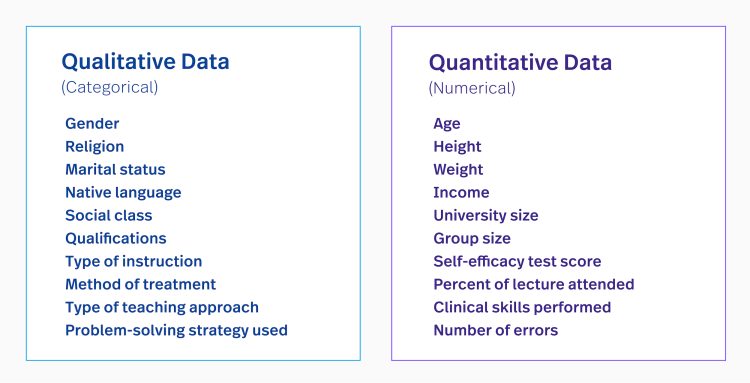

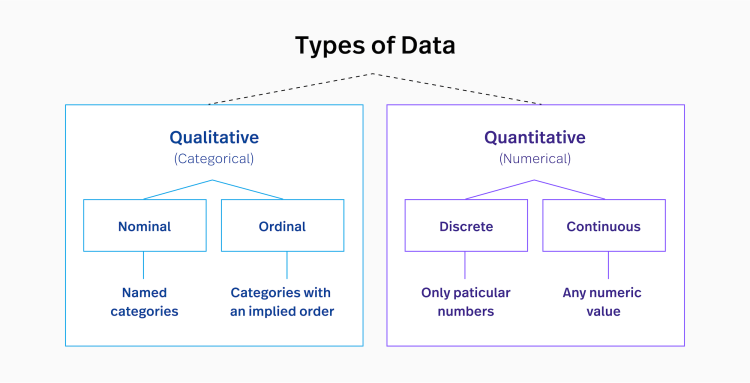

Qualitative data is defined as data that approximates and characterizes. It can be observed and recorded.

This data type is non-numerical in nature. This type of data is collected through methods of observations, one-to-one interviews, conducting focus groups, and similar methods.

Qualitative data in statistics is also known as categorical data – data that can be arranged categorically based on the attributes and properties of a thing or a phenomenon.

It’s pretty easy to understand the difference between qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative data does not include numbers in its definition of traits, whereas quantitative research data is all about numbers.

- The cake is orange, blue, and black in color (qualitative).

- Females have brown, black, blonde, and red hair (qualitative).

Qualitative data collection is gathering non-numerical information, such as words, images, and observations, to understand individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, and motivations in a specific context. It is an approach used in qualitative research. It seeks to understand social phenomena through in-depth exploration and analysis of people’s perspectives, experiences, and narratives. In statistical analysis , distinguishing between categorical data and numerical data is essential, as categorical data involves distinct categories or labels, while numerical data consists of measurable quantities.

The data collected through qualitative methods are often subjective, open-ended, and unstructured and can provide a rich and nuanced understanding of complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research is a type of study carried out with a qualitative approach to understand the exploratory reasons and to assay how and why a specific program or phenomenon operates in the way it is working. A researcher can access numerous qualitative data collection methods that he/she feels are relevant.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

Qualitative data collection methods serve the primary purpose of collecting textual data for research and analysis , like the thematic analysis. The collected research data is used to examine:

- Knowledge around a specific issue or a program, experience of people.

- Meaning and relationships.

- Social norms and contextual or cultural practices demean people or impact a cause.

The qualitative data is textual or non-numerical. It covers mostly the images, videos, texts, and written or spoken words by the people. You can opt for any digital data collection methods , like structured or semi-structured surveys, or settle for the traditional approach comprising individual interviews, group discussions, etc.

Data at hand leads to a smooth process ensuring all the decisions made are for the business’s betterment. You will be able to make informed decisions only if you have relevant data.

Well! With quality data, you will improve the quality of decision-making. But you will also enhance the quality of the results expected from any endeavor.

Qualitative data collection methods are exploratory. Those are usually more focused on gaining insights and understanding the underlying reasons by digging deeper.

Although quantitative data cannot be quantified, measuring it or analyzing qualitative data might become an issue. Due to the lack of measurability, collection methods of qualitative data are primarily unstructured or structured in rare cases – that too to some extent.

Let’s explore the most common methods used for the collection of qualitative data:

Individual interview

It is one of the most trusted, widely used, and familiar qualitative data collection methods primarily because of its approach. An individual or face-to-face interview is a direct conversation between two people with a specific structure and purpose.

The interview questionnaire is designed in the manner to elicit the interviewee’s knowledge or perspective related to a topic, program, or issue.

At times, depending on the interviewer’s approach, the conversation can be unstructured or informal but focused on understanding the individual’s beliefs, values, understandings, feelings, experiences, and perspectives on an issue.

More often, the interviewer chooses to ask open-ended questions in individual interviews. If the interviewee selects answers from a set of given options, it becomes a structured, fixed response or a biased discussion.

The individual interview is an ideal qualitative data collection method. Particularly when the researchers want highly personalized information from the participants. The individual interview is a notable method if the interviewer decides to probe further and ask follow-up questions to gain more insights.

Qualitative surveys

To develop an informed hypothesis, many researchers use qualitative research surveys for data collection or to collect a piece of detailed information about a product or an issue. If you want to create questionnaires for collecting textual or qualitative data, then ask more open-ended questions .

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

To answer such qualitative research questions , the respondent has to write his/her opinion or perspective concerning a specific topic or issue. Unlike other collection methods, online surveys have a wider reach. People can provide you with quality data that is highly credible and valuable.

Paper surveys

Online surveys, focus group discussions.

Focus group discussions can also be considered a type of interview, but it is conducted in a group discussion setting. Usually, the focus group consists of 8 – 10 people (the size may vary depending on the researcher’s requirement). The researchers ensure appropriate space is given to the participants to discuss a topic or issue in a context. The participants are allowed to either agree or disagree with each other’s comments.

With a focused group discussion, researchers know how a particular group of participants perceives the topic. Researchers analyze what participants think of an issue, the range of opinions expressed, and the ideas discussed. The data is collected by noting down the variations or inconsistencies (if any exist) in the participants, especially in terms of belief, experiences, and practice.

The participants of focused group discussions are selected based on the topic or issues for which the researcher wants actionable insights. For example, if the research is about the recovery of college students from drug addiction. The participants have to be college students studying and recovering from drug addiction.

Other parameters such as age, qualification, financial background, social presence, and demographics are also considered, but not primarily, as the group needs diverse participants. Frequently, the qualitative data collected through focused group discussion is more descriptive and highly detailed.

Record keeping

This method uses reliable documents and other sources of information that already exist as the data source. This information can help with the new study. It’s a lot like going to the library. There, you can look through books and other sources to find information that can be used in your research.

Case studies

In this method, data is collected by looking at case studies in detail. This method’s flexibility is shown by the fact that it can be used to analyze both simple and complicated topics. This method’s strength is how well it draws conclusions from a mix of one or more qualitative data collection methods.

Observations

Observation is one of the traditional methods of qualitative data collection. It is used by researchers to gather descriptive analysis data by observing people and their behavior at events or in their natural settings. In this method, the researcher is completely immersed in watching people by taking a participatory stance to take down notes.

There are two main types of observation:

- Covert: In this method, the observer is concealed without letting anyone know that they are being observed. For example, a researcher studying the rituals of a wedding in nomadic tribes must join them as a guest and quietly see everything.

- Overt: In this method, everyone is aware that they are being watched. For example, A researcher or an observer wants to study the wedding rituals of a nomadic tribe. To proceed with the research, the observer or researcher can reveal why he is attending the marriage and even use a video camera to shoot everything around him.

Observation is a useful method of qualitative data collection, especially when you want to study the ongoing process, situation, or reactions on a specific issue related to the people being observed.

When you want to understand people’s behavior or their way of interaction in a particular community or demographic, you can rely on the observation data. Remember, if you fail to get quality data through surveys, qualitative interviews , or group discussions, rely on observation.

It is the best and most trusted collection method of qualitative data to generate qualitative data as it requires equal to no effort from the participants.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

You invested time and money acquiring your data, so analyze it. It’s necessary to avoid being in the dark after all your hard work. Qualitative data analysis starts with knowing its two basic techniques, but there are no rules.

- Deductive Approach: The deductive data analysis uses a researcher-defined structure to analyze qualitative data. This method is quick and easy when a researcher knows what the sample population will say.

- Inductive Approach: The inductive technique has no structure or framework. When a researcher knows little about the event, an inductive approach is applied.

Whether you want to analyze qualitative data from a one-on-one interview or a survey, these simple steps will ensure a comprehensive qualitative data analysis.

Step 1: Arrange your Data

After collecting all the data, it is mostly unstructured and sometimes unclear. Arranging your data is the first stage in qualitative data analysis. So, researchers must transcribe data before analyzing it.

Step 2: Organize all your Data

After transforming and arranging your data, the next step is to organize it. One of the best ways to organize the data is to think back to your research goals and then organize the data based on the research questions you asked.

Step 3: Set a Code to the Data Collected

Setting up appropriate codes for the collected data gets you one step closer. Coding is one of the most effective methods for compressing a massive amount of data. It allows you to derive theories from relevant research findings.

Step 4: Validate your Data

Qualitative data analysis success requires data validation. Data validation should be done throughout the research process, not just once. There are two sides to validating data:

- The accuracy of your research design or methods.

- Reliability—how well the approaches deliver accurate data.

Step 5: Concluding the Analysis Process

Finally, conclude your data in a presentable report. The report should describe your research methods, their pros and cons, and research limitations. Your report should include findings, inferences, and future research.

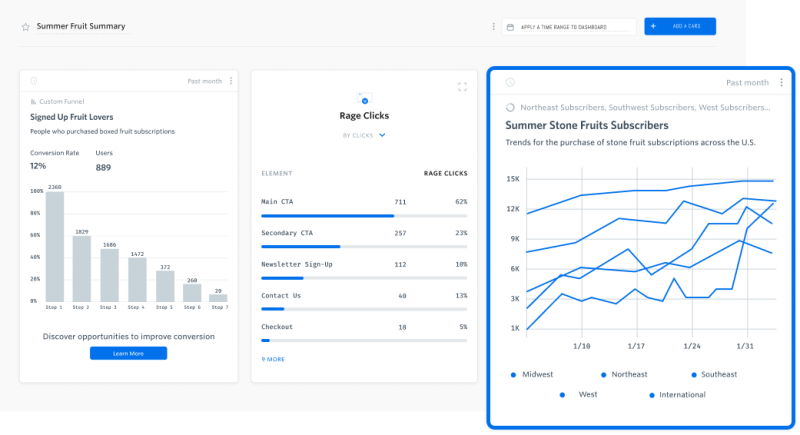

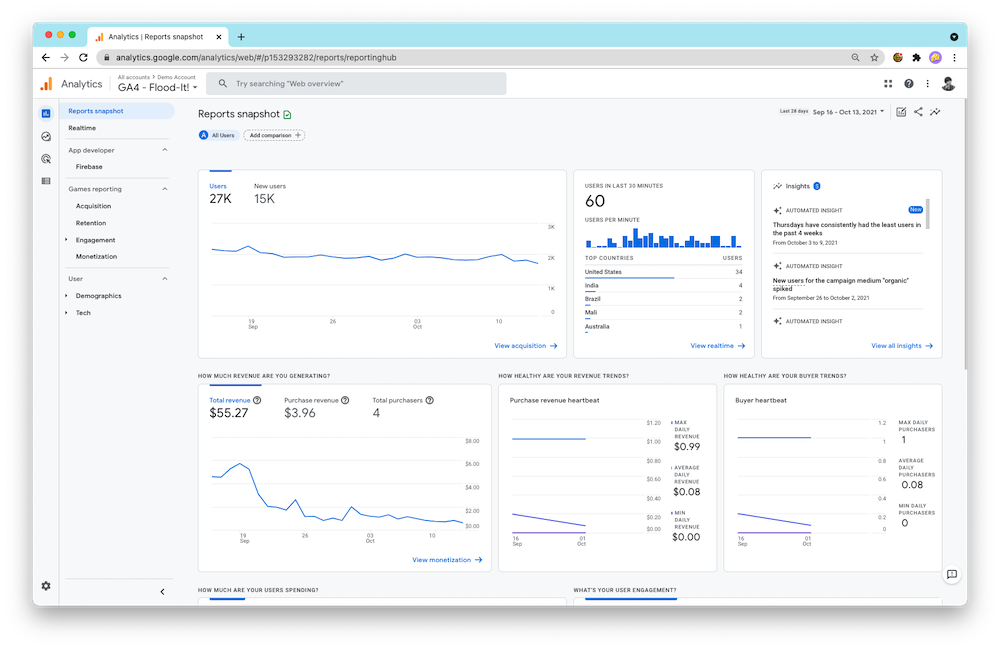

QuestionPro is a comprehensive online survey software that offers a variety of qualitative data analysis tools to help businesses and researchers in making sense of their data. Users can use many different qualitative analysis methods to learn more about their data.

Users of QuestionPro can see their data in different charts and graphs, which makes it easier to spot patterns and trends. It can help researchers and businesses learn more about their target audience, which can lead to better decisions and better results.

LEARN ABOUT: Steps in Qualitative Research

Qualitative data collection has several advantages, including:

- In-depth understanding: It provides in-depth information about attitudes and behaviors, leading to a deeper understanding of the research.

- Flexibility: The methods allow researchers to modify questions or change direction if new information emerges.

- Contextualization: Qualitative research data is in context, which helps to provide a deep understanding of the experiences and perspectives of individuals.

- Rich data: It often produces rich, detailed, and nuanced information that cannot capture through numerical data.

- Engagement: The methods, such as interviews and focus groups, involve active meetings with participants, leading to a deeper understanding.

- Multiple perspectives: This can provide various views and a rich array of voices, adding depth and complexity.

- Realistic setting: It often occurs in realistic settings, providing more authentic experiences and behaviors.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

Qualitative research is one of the best methods for identifying the behavior and patterns governing social conditions, issues, or topics. It spans a step ahead of quantitative data as it fails to explain the reasons and rationale behind a phenomenon, but qualitative data quickly does.

Qualitative research is one of the best tools to identify behaviors and patterns governing social conditions. It goes a step beyond quantitative data by providing the reasons and rationale behind a phenomenon that cannot be explored quantitatively.

With QuestionPro, you can use it for qualitative data collection through various methods. Using Our robust suite correctly, you can enhance the quality and integrity of the collected data.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Employee Listening Strategy: What it is & How to Build One

Jul 17, 2024

Winning the Internal CX Battles — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Jul 16, 2024

Knowledge Management: What it is, Types, and Use Cases

Jul 12, 2024

Response Weighting: Enhancing Accuracy in Your Surveys

Jul 11, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved July 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Qualitative Study Design and Data Collection

- First Online: 10 February 2022

Cite this chapter

- Charles P. Friedman 4 ,

- Jeremy C. Wyatt 5 &

- Joan S. Ash 6

Part of the book series: Health Informatics ((HI))

1682 Accesses

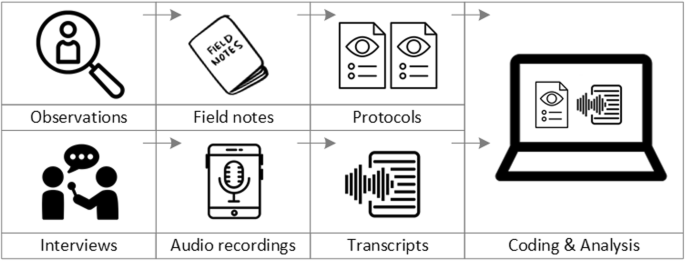

While the prior chapter set the stage for an understanding of the nature of qualitative evaluation, this chapter will offer strategies for planning a study and making decisions about how to gather data. The process is depicted as an iterative looping through steps beginning with idea generation to dissemination of results. It is critical that strategies for rigor be incorporated throughout the process. This chapter outlines methods for data collection utilizing interviews, focus groups, observation, and naturally occurring data, and then it also describes combinations often used together, which constitute toolkits of complementary techniques.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

This is of course a major point of departure between qualitative methods and their quantitative counterparts. In quantitative work, investigators rarely acknowledge bias, and if they do, they may be disqualified from participating in the study.

For the same reasons, the observers should not dress too formally. They should dress as comparably as possible to the workers being observed in the field. Always ask ahead of time about dress codes.

Ash JS, Chin HL, Sittig DF, Dykstra R. Ambulatory computerized physician order entry implementation. Proc Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;2005:11–5.

Google Scholar

Ash JS, Sittig DF, McMullen CK, Wright A, Bunce A, Mohan V, Cohen DJ, Middleton B. Multiple perspectives on clinical decision support: a qualitative study of fifteen clinical and vendor organizations. BMC Med Inform Decision Making. 2015 Apr 24;15:35.

Article Google Scholar

Beebe J. Rapid assessment process: an introduction. Lanham, PA: AltaMira Press; 2001.

Berg BL, Lune H. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 8th ed. Boston: Pearson; 2012.

Brunet LW, Morrissey CY, Gorry GA. Oral history and information technology: human voices of assessment. J Org Comput. 1991;1:251–74.

Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999.

Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR. User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Manag Sci. 1989;35:982–1003.

Erickson K, Stull D. Doing team ethnography: warnings and advice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

Book Google Scholar

Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE. The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e38–46.

Glaser BG, Strauss A. Discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1967.

Goedhart NS, Zuiderent-Jerak T, Woudstra J, Broerse JEW, Betten AW, Dedding C. Persistent inequitable design and implementation of patient portals for users at the margins. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28:276–83.

Hussain MI, Figuerredo MC, Tran BD, Su Z, Molldrem S, Eikey EV, Chen Y. A scoping review of qualitative research in JAMIA: past contributions and opportunities for future work. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28:402–13.

Kiyimba N, Lester JN, O’Reilly M. Using naturally occurring data in qualitative Health Research: a practical guide. Amsterdam: Springer; 2019.

Leedy PD, Ormrod JE. Practical research: planning and design. 11th ed. Pearson: Boston, MA; 2016.

Linstone H. Multiple perspectives for decision making: bridging the gap between analysis and action. North-Holland Elsevier: Amsterdam, NE; 1984.

McMullen CK, Ash JS, Sittig DF, Bunce A, Guappone K, Dykstra R, et al. Rapid assessment of clinical information systems in the healthcare setting: an efficient method for time-pressed evaluation. Methods Inform Med. 2011;50:299–307.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994.

Mohan V, Woodcock D, McGrath K, Scholl G, Pransat R, Doberne JW, et al. Using simulations to improve electronic health record use, clinician training and patient safety: recommendations from a consensus conference. AMIA Ann Symp Proc. 2016;2016:904–13.

Morgan DL, Krueger RA. The focus group kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research. Qualitative methods in health research: opportunities and considerations in application and review. NIH Publication No. 02-!5046, December 2001.

Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1980.

Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2020.

Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995.

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990.

Tolley EE, Ulin PR, Mack N, Robinson ET, Succop SM. Qualitative methods in public health: a field guide for applied research. Hoboken NJ: Wiley; 2016.

University of Technology Sydney. Adapting research methods in the COVID-19 pandemic: resources for researchers, 2nd ed. UTS and University of Washington, December, 2020.

Weinstein JN, Caciu A, editors. Communities in action: pathways to health equity. New York: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, National Academies Press; 2017.

Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Learning Health Sciences, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Charles P. Friedman

Department of Primary Care, Population Sciences and Medical Education, School of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

Jeremy C. Wyatt

Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA

Joan S. Ash

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Charles P. Friedman .

Answers to Self-Tests

Self-test 15.1.

Which of the strategies to ensure study rigor is primarily employed in the qualitative study scenarios below:

Data from interviews about the usability of a resource are analyzed thematically. The evaluation study team looks to see if and how similar themes have arisen in earlier meetings of the team.

Audit trail

A member of the study team, who has recently participated in another study of a similar kind of resource, becomes concerned that that person’s views about the current study are being shaped by that previous experience. That person sits with another member of the study team to share that person’s concerns and put them in perspective.

Reflexivity

At a “town hall” meeting called to present the results of a qualitative study, the sponsor of the study raises deep and serious questions about the validity of the findings. The study team returns to notes from their team meetings to review how and based on what data they came to this conclusion.

Member checking

During an evaluation project team meeting, one of the study team members finds themselves deeply repelled by off-color comments made by one of the project staff. The team member makes a note of this personal response as part of field notes.

After interviewing 10 patients participating in a study, a study team member perceives that they are hearing the same points raised by all interviewees. The team member requests a study team meeting to consider reducing the total number of interviews from 20, as previously planned, to 12.

Data saturation

A study team member “corners” a participant in a system development effort following a meeting and asks for the participant’s impressions on what transpired in the meeting.

Self-Test 15.2

Label each of the following interview scenarios, conducted as part of a qualitative study, as representing the fully structured, semi-structured or unstructured approach.

A study team member “corners” a participant in a system development project following a meeting and asks for that person’s impressions on what transpired in the meeting.

A study team member schedules time with a patient who is using an information resource to acquire specific information about the patient’s medical history.

Likely fully structured, though it could generate discussion, in which case it could veer towards semi-structured.

A study team member works with partners on the study team to develop a set of questions to be asked to all interviewees. Each question is to be followed up with the question: “Why do you think this is the case?”. At the end of the interview, subjects will be asked: “What else would you like to tell us to shed light on these matters?”

Semi-structured

An interview begins with the statement: “In general, what has been your experience using this EHR?” The remaining questions depend on how the interviewee answers this opening question.

Unstructured

A set of specific questions are read verbatim from an interview guide. No other questions are asked. The interviewees’ responses are recorded.

Fully structured

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Friedman, C.P., Wyatt, J.C., Ash, J.S. (2022). Qualitative Study Design and Data Collection. In: Evaluation Methods in Biomedical and Health Informatics. Health Informatics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86453-8_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86453-8_15

Published : 10 February 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-86452-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-86453-8

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

UpMetrics Blog

Read the latest expert insights, trends, and best practices around impact measurement and leveraging actionable data to drive meaningful change.

8 Essential Qualitative Data Collection Methods

Qualitative data methods allow you to deep dive into the mindset of your audience to discover areas for growth, development, and improvement.

British mathematician and marketing mastermind Clive Humby once famously stated that “Data is the new oil.” He has a point. Without data, nonprofit organizations are left second-guessing what their clients and supporters think, how their brand compares to others in the market, whether their messaging is on-point, how their campaigns are performing, where improvements can be made, and how overall results can be optimized.

There are two primary data collection methodologies: qualitative data collection and quantitative data collection. At UpMetrics, we believe that relying on quantitative, static data is no longer an option to drive effective impact. In the nonprofit sector, where financial gain is not the sole purpose of your organization’s existence. In this guide, we’ll focus on qualitative data collection methods and how they can help you gather, analyze, and collate information that can help drive your organization forward.

What is Qualitative Data?

Data collection in qualitative research focuses on gathering contextual information. Unlike quantitative data, which focuses primarily on numbers to establish ‘how many’ or ‘how much,’ qualitative data collection tools allow you to assess the ‘why’s’ and ‘how’s’ behind those statistics. This is vital for nonprofits as it enables organizations to determine:

- Existing knowledge surrounding a particular issue.

- How social norms and cultural practices impact a cause.

- What kind of experiences and interactions people have with your brand.

- Trends in the way people change their opinions.

- Whether meaningful relationships are being established between all parties.

In short, qualitative data collection methods collect perceptual and descriptive information that helps you understand the reasoning and motivation behind particular reactions and behaviors. For that reason, qualitative data methods are usually non-numerical and center around spoken and written words rather than data extrapolated from a spreadsheet or report.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Data

Quantitative and qualitative data represent both sides of the same coin. There will always be some degree of debate over the importance of quantitative vs. qualitative research, data, and collection. However, successful organizations should strive to achieve a balance between the two.

Organizations can track their performance by collecting quantitative data based on metrics including dollars raised, membership growth, number of people served, overhead costs, etc. This is all essential information to have. However, the data lacks value without the additional details provided by qualitative research because it doesn’t tell you anything about how your target audience thinks, feels, and acts.

Qualitative data collection is particularly relevant in the nonprofit sector as the relationships people have with the causes they support are fundamentally personal and cannot be expressed numerically. Qualitative data methods allow you to deep dive into the mindset of your audience to discover areas for growth, development, and improvement.

8 Types of Qualitative Data Collection Methods

As we have firmly established the need for qualitative data, it’s time to answer the next big question: how to collect qualitative data.

Here is a list of the most common qualitative data collection methods. You don’t need to use them all in your quest for gathering information. However, a foundational understanding of each will help you refine your research strategy and select the methods that are likely to provide the highest quality business intelligence for your organization.

1. Interviews

One-on-one interviews are one of the most commonly used data collection methods in qualitative research because they allow you to collect highly personalized information directly from the source. Interviews explore participants' opinions, motivations, beliefs, and experiences and are particularly beneficial in gathering data on sensitive topics because respondents are more likely to open up in a one-on-one setting than in a group environment.

Interviews can be conducted in person or by online video call. Typically, they are separated into three main categories:

- Structured Interviews - Structured interviews consist of predetermined (and usually closed) questions with little or no variation between interviewees. There is generally no scope for elaboration or follow-up questions, making them better suited to researching specific topics.

- Unstructured Interviews – Conversely, unstructured interviews have little to no organization or preconceived topics and include predominantly open questions. As a result, the discussion will flow in completely different directions for each participant and can be very time-consuming. For this reason, unstructured interviews are generally only used when little is known about the subject area or when in-depth responses are required on a particular subject.

- Semi-Structured Interviews – A combination of the two interviews mentioned above, semi-structured interviews comprise several scripted questions but allow both interviewers and interviewees the opportunity to diverge and elaborate so more in-depth reasoning can be explored.

While each approach has its merits, semi-structured interviews are typically favored as a way to uncover detailed information in a timely manner while highlighting areas that may not have been considered relevant in previous research efforts. Whichever type of interview you utilize, participants must be fully briefed on the format, purpose, and what you hope to achieve. With that in mind, here are a few tips to follow:

- Give them an idea of how long the interview will last

- If you plan to record the conversation, ask permission beforehand

- Provide the opportunity to ask questions before you begin and again at the end.

2. Focus Groups

Focus groups share much in common with less structured interviews, the key difference being that the goal is to collect data from several participants simultaneously. Focus groups are effective in gathering information based on collective views and are one of the most popular data collection instruments in qualitative research when a series of one-on-one interviews proves too time-consuming or difficult to schedule.

Focus groups are most helpful in gathering data from a specific group of people, such as donors or clients from a particular demographic. The discussion should be focused on a specific topic and carefully guided and moderated by the researcher to determine participant views and the reasoning behind them.

Feedback in a group setting often provides richer data than one-on-one interviews, as participants are generally more open to sharing when others are sharing too. Plus, input from one participant may spark insight from another that would not have come to light otherwise. However, here are a couple of potential downsides:

- If participants are uneasy with each other, they may not be at ease openly discussing their feelings or opinions.

- If the topic is not of interest or does not focus on something participants are willing to discuss, data will lack value.

The size of the group should be carefully considered. Research suggests over-recruiting to avoid risking cancellation, even if that means moderators have to manage more participants than anticipated. The optimum group size is generally between six and eight for all participants to be granted ample opportunity to speak. However, focus groups can still be successful with as few as three or as many as fourteen participants.

3. Observation

Observation is one of the ultimate data collection tools in qualitative research for gathering information through subjective methods. A technique used frequently by modern-day marketers, qualitative observation is also favored by psychologists, sociologists, behavior specialists, and product developers.

The primary purpose is to gather information that cannot be measured or easily quantified. It involves virtually no cognitive input from the participants themselves. Researchers simply observe subjects and their reactions during the course of their regular routines and take detailed field notes from which to draw information.

Observational techniques vary in terms of contact with participants. Some qualitative observations involve the complete immersion of the researcher over a period of time. For example, attending the same church, clinic, society meetings, or volunteer organizations as the participants. Under these circumstances, researchers will likely witness the most natural responses rather than relying on behaviors elicited in a simulated environment. Depending on the study and intended purpose, they may or may not choose to identify themselves as a researcher during the process.

Regardless of whether you take a covert or overt approach, remember that because each researcher is as unique as every participant, they will have their own inherent biases. Therefore, observational studies are prone to a high degree of subjectivity. For example, one researcher’s notes on the behavior of donors at a society event may vary wildly from the next. So, each qualitative observational study is unique in its own right.

4. Open-Ended Surveys and Questionnaires

Open-ended surveys and questionnaires allow organizations to collect views and opinions from respondents without meeting in person. They can be sent electronically and are considered one of the most cost-effective qualitative data collection tools. Unlike closed question surveys and questionnaires that limit responses, open-ended questions allow participants to provide lengthy and in-depth answers from which you can extrapolate large amounts of data.

The findings of open-ended surveys and questionnaires can be challenging to analyze because there are no uniform answers. A popular approach is to record sentiments as positive, negative, and neutral and further dissect the data from there. To gather the best business intelligence, carefully consider the presentation and length of your survey or questionnaire. Here is a list of essential considerations:

- Number of questions : Too many can feel intimidating, and you’ll experience low response rates. Too few can feel like it’s not worth the effort. Plus, the data you collect will have limited actionability. The consensus on how many questions to include varies depending on which sources you consult. However, 5-10 is a good benchmark for shorter surveys that take around 10 minutes and 15-20 for longer surveys that take approximately 20 minutes to complete.

- Personalization: Your response rate will be higher if you greet patients by name and demonstrate a historical knowledge of their interactions with your brand.

- Visual elements : Recipients can be easily turned off by poorly designed questionnaires. Besides, it’s a good idea to customize your survey template to include brand assets like colors, logos, and fonts to increase brand loyalty and recognition.

- Reminders : Sending survey reminders is the best way to improve your response rate. You don’t want to hassle respondents too soon, nor do you want to wait too long. Sending a follow-up at around the 3-7 mark is usually the most effective.

- Building a feedback loop : Adding a tick-box requesting permission for further follow-ups is a proven way to elicit more in-depth feedback. Plus, it gives respondents a voice and makes their opinion feel valued.

5. Case Studies

Case studies are often a preferred method of qualitative research data collection for organizations looking to generate incredibly detailed and in-depth information on a specific topic. Case studies are usually a deep dive into one specific case or a small number of related cases. As a result, they work well for organizations that operate in niche markets.

Case studies typically involve several qualitative data collection methods, including interviews, focus groups, surveys, and observation. The idea is to cast a wide net to obtain a rich picture comprising multiple views and responses. When conducted correctly, case studies can generate vast bodies of data that can be used to improve processes at every client and donor touchpoint.

The best way to demonstrate the purpose and value of a case study is with an example: A Longitudinal Qualitative Case Study of Change in Nonprofits – Suggesting A New Approach to the Management of Change .

The researchers established that while change management had already been widely researched in commercial and for-profit settings, little reference had been made to the unique challenges in the nonprofit sector. The case study examined change and change management at a single nonprofit hospital from the viewpoint of all those who witnessed and experienced it. To gain a holistic view of the entire process, research included interviews with employees at every level, from nursing staff to CEOs, to identify the direct and indirect impacts of change. Results were collated based on detailed responses to questions about preparing for change, experiencing change, and reflecting on change.

6. Text Analysis

Text analysis has long been used in political and social science spheres to gain a deeper understanding of behaviors and motivations by gathering insights from human-written texts. By analyzing the flow of text and word choices, relationships between other texts written by the same participant can be identified so that researchers can draw conclusions about the mindset of their target audience. Though technically a qualitative data collection method, the process can involve some quantitative elements, as often, computer systems are used to scan, extract, and categorize information to identify patterns, sentiments, and other actionable information.

You might be wondering how to collect written information from your research subjects. There are many different options, and approaches can be overt or covert.

Examples include:

- Investigating how often certain cause-related words and phrases are used in client and donor social media posts.

- Asking participants to keep a journal or diary.

- Analyzing existing interview transcripts and survey responses.

By conducting a detailed analysis, you can connect elements of written text to specific issues, causes, and cultural perspectives, allowing you to draw empirical conclusions about personal views, behaviors, and social relations. With small studies focusing on participants' subjective experience on a specific theme or topic, diaries and journals can be particularly effective in building an understanding of underlying thought processes and beliefs.

7. Audio and Video Recordings

Similarly to how data is collected from a person’s writing, you can draw valuable conclusions by observing someone’s speech patterns, intonation, and body language when you watch or listen to them interact in a particular environment or within specific surroundings.

Video and audio recordings are helpful in circumstances where researchers predict better results by having participants be in the moment rather than having them think about what to write down or how to formulate an answer to an email survey.

You can collect audio and video materials for analysis from multiple sources, including:

- Previously filmed records of events

- Interview recordings

- Video diaries

Utilizing audio and video footage allows researchers to revisit key themes, and it's possible to use the same analytical sources in multiple studies – providing that the scope of the original recording is comprehensive enough to cover the intended theme in adequate depth.

It can be challenging to present the results of audio and video analysis in a quantifiable form that helps you gauge campaign and market performance. However, results can be used to effectively design concept maps that extrapolate central themes that arise consistently. Concept Mapping offers organizations a visual representation of thought patterns and how ideas link together between different demographics. This data can prove invaluable in identifying areas for improvement and change across entire projects and organizational processes.

8. Hybrid Methodologies

It is often possible to utilize data collection methods in qualitative research that provide quantitative facts and figures. So if you’re struggling to settle on an approach, a hybrid methodology may be a good starting point. For instance, a survey format that asks closed and open questions can collect and collate quantitative and qualitative data.

A Net Promoter Score (NPS) survey is a great example. The primary goal of an NPS survey is to collect quantitative ratings of various factors on a score of 1-10. However, they also utilize open-ended follow-up questions to collect qualitative data that helps identify insights into the trends, thought processes, reasoning, and behaviors behind the initial scoring.

Collect and Collate Actionable Data with UpMetrics

Most nonprofits believe data is strategically important. It has been statistically proven that organizations with advanced data insights achieve their missions more efficiently. Yet, studies show that despite 90% of organizations collecting data, only 5% believe internal decision-making is data-driven. At UpMetrics, we’re here to help you change that.

UpMetrics specializes in bringing technology and humanity together to serve social good. Our unique social impact software combines quantitative and qualitative data collection methods and analysis techniques, enabling social impact organizations to gain insights, drive action, and inspire change. By reporting and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data in one intuitive platform, your impact organization gains the understanding it needs to identify the drivers of positive outcomes, achieve transparency, and increase knowledge sharing across stakeholders.

Contact us today to learn more about our nonprofit impact measurement solutions and discover the power of a partnership with UpMetrics.

Disrupting Tradition

Download our case study to discover how the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation is using a Learning Mindset to Support Grantees in Measuring Impact

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

759k Accesses

332 Citations

90 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

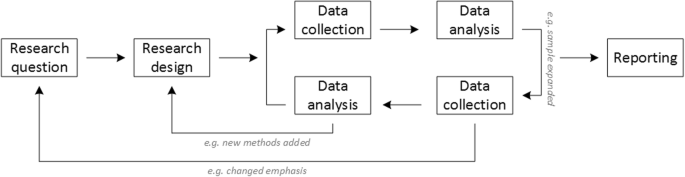

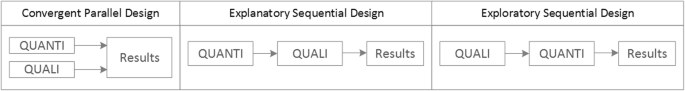

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

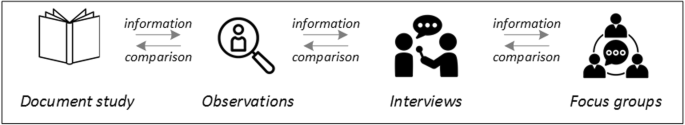

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations