- Mental Health , Research

- Written by Cara Goodwin, Ph.D.

Homework: The Good and The Bad

Homework. A single word that for many brings up memories of childhood stress. Now that you’re a parent, you may be reminded of that feeling every time your child spills their backpack across the table. You also may be questioning how much homework is too much and wondering how you can best help your child with their schoolwork.

Here, Dr. Cara Goodwin of Parenting Translator explains what the research actually says about homework. She outlines specific ways parents can support their kids to maximize the academic benefits and develop lifelong skills in time management and persistence.

In recent years, many parents and educators have raised concerns about homework. Specifically, they have questioned how much it enhances learning and if its benefits outweigh potential costs, such as stress to the family.

So, what does the research say?

Academic benefits vs risks of homework

One of the most important questions when it comes to homework is whether it actually helps kids understand the content better. So does it? Research finds that homework is associated with higher scores on academic standardized tests for middle and high school students, but not for elementary school students (1, 2).

In other words, homework seems to have little impact on learning in elementary school students.

Additionally, a 2012 study found that while homework is related to higher standardized test scores for high schoolers, it is not related to higher grades.

Not surprisingly, homework is more likely to be associated with improved academic performance when students and teachers find the homework to be meaningful or relevant, according to several studies (1, 3, 4). Students tend to find homework to be most engaging when it involves solving real-world problems (5).

The impact of homework may also depend on socioeconomic status. Students from higher income families show improved academic skills with more homework and gain more knowledge from homework, according to research. On the other hand, the academic performance of more disadvantaged children seems to be unaffected by homework (6, 7). This may be because homework provides additional stress for disadvantaged children. They are less likely to get help from their parents on homework and more likely to be punished by teachers for not completing it (8).

Non-academic benefits vs risks of homework

Academic outcomes are only part of the picture. It is important to look at how homework affects kids in ways other than grades and test scores.

Homework appears to have benefits beyond improving academic skills, particularly for younger students. These benefits include building responsibility, time management skills, and persistence (1, 9, 10). In addition, homework may also increase parents’ involvement in their children’s schooling (11, 12, 13, 14).

Yet, studies show that too much homework has drawbacks. It can reduce children’s opportunities for free play, which is essential for the development of language, cognitive, self-regulation, and social-emotional skills (15). It may also interfere with physical activity, and too much homework is associated with an increased risk for being overweight (16, 17).

In addition to homework reducing opportunities for play, it also leads to increased conflicts and stress for families. For example, research finds that children with more hours of homework experience more academic stress, physical health problems, and lack of balance in their lives (18).

Clearly, more is not better when it comes to homework.

What is the “right” amount of homework?

Recent reports indicate that elementary school students are assigned three times the recommended amount of homework. Even kindergarten students report an average of 25 minutes of homework per day (19).

Additionally, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) found that homework has been increasing in recent years for younger students. Specifically, 35% of 9-year-olds reported that they did not do homework the previous night in 1984 versus 22% of 9-years-old in 2012. However, homework levels have stayed relatively stable for 13- and 17-year-olds during this same time period.

Research suggests that homework should not exceed 1.5 to 2.5 hours per night for high school students and no more than 1 hour per night for middle school students (1). Homework for elementary school students should be minimal and assigned with the aim of building self-regulation and independent work skills. A common rule , supported by both the National Education Association (NEA) and National Parent Teacher Association (PTA), is 10-minutes of homework per grade in elementary school. Any more than this and homework may no longer have a positive impact. Importantly, the NEA and the National PTA do not endorse homework for kindergarteners.

How can parents best help with homework?

Most parents feel that they are expected to be involved in their children’s homework (20). Yet, it is often unclear exactly how to be involved in a way that helps your child to successfully complete the assignment without taking over entirely. Most studies find that parental help is important but that it matters more HOW the parent is helping rather than how OFTEN the parent is helping (21).

While this can all feel very overwhelming for parents, there are some simple guidelines you can follow to ease the homework burden and best support your child’s learning.

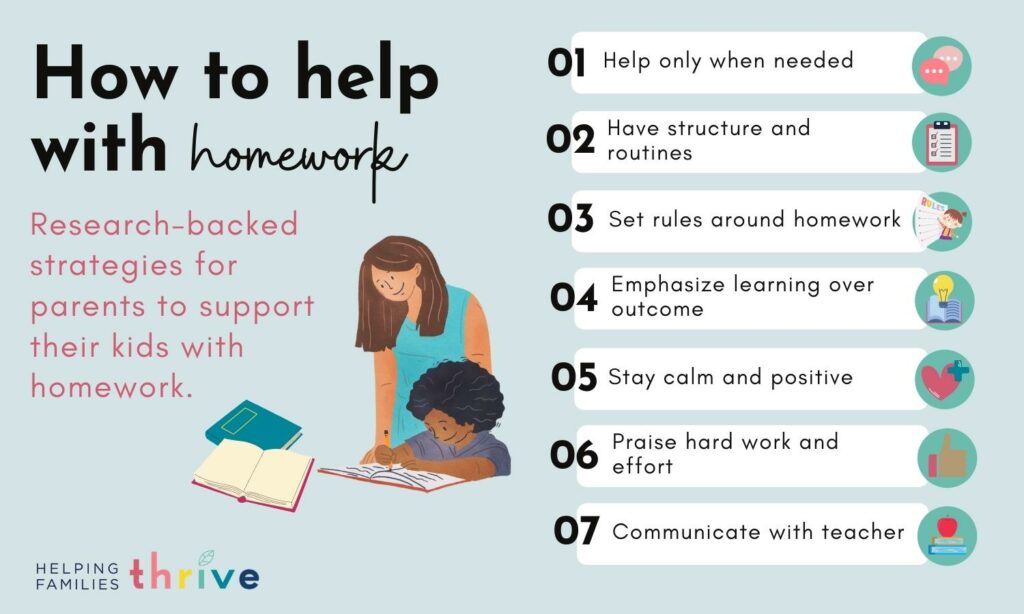

1. Help only when needed.

Parents should focus on providing general monitoring, guidance and encouragement. Allow children to generate answers on their own and complete their homework as independently as possible . This is important because research shows that allowing children more independence in completing homework benefits their academic skills (22, 23). In addition, too much parent involvement and being controlling with homework is associated with worse academic performance (21, 24, 25).

What does this look like?

- Be present when your child is completing homework to help them to understand the directions.

- Be available to answer simple questions and to provide praise for their effort and hard work.

- Only provide help when your child asks for it and step away whenever possible.

2. Have structure and routines.

Help your child create structure and to develop some routines. This helps children become more independent in completing their homework. Research finds that providing this type of structure and responsiveness is related to improved academic skills (25).

This structure may include:

- A regular time and place for homework that is free from distractions.

- Have all of the materials they need within arm’s reach.

- Teach and encourage kids to create a checklist for their homework tasks each day.

Parents can also help their children to find ways to stay motivated. For example, developing their own reward system or creating a homework schedule with breaks for fun activities.

3. Set specific rules around homework.

Research finds that parents setting rules around homework is related to higher academic performance (26). For example, parents may require that children finish homework before screen time or may require children to stop doing homework and go to sleep at a certain hour.

4. Emphasize learning over outcome.

Encourage your child to persist in challenging assignments and frame difficult assignments as opportunities to grow. Research finds that this attitude is associated with student success (20). Research also indicates that more challenging homework is associated with enhanced school performance (27).

Additionally, help your child to view homework as an opportunity to learn and improve skills. Parents who view homework as a learning opportunity rather than something that they must get “right” or complete successfully to obtain a higher grade are more likely to have children with the same attitudes (28).

5. Stay calm and positive.

Yes, we know this is easier said than done, but it does have a big impact on how kids persevere when things get hard! Research shows that mothers showing positive emotions while helping with homework may improve children’s motivation in homework (29)

6. Praise hard work and effort.

Praise focused on effort is likely to increase motivation (30). In addition, research finds that putting more effort into homework may be associated with enhanced development of conscientiousness in children (31).

7. Communicate with your child’s teacher.

Let your child’s teacher know about any problems your child has with homework and the teachers’ learning goals. Research finds that open communication about homework is associated with improved school performance (32).

In summary, research finds that homework provides some academic benefit for middle- and high-school students but is less beneficial for elementary school students. As a parent, how you are involved in your child’s homework really matters. By following these evidence-based tips, you can help your child to maximize the benefits of homework and make the process less painful for all involved!

For more resources, take a look at our recent posts on natural and logical consequences and simple ways to decrease challenging behaviors .

- Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003. Review of educational research , 76 (1), 1-62.

- Muhlenbruck, L., Cooper, H., Nye, B., & Lindsay, J. J. (1999). Homework and achievement: Explaining the different strengths of relation at the elementary and secondary school levels. Social Psychology of Education , 3 (4), 295-317.

- Marzano, R. J., & Pickering, D. J. (2007). Special topic: The case for and against homework. Educational leadership , 64 (6), 74-79.

- Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Schnyder, I., & Niggli, A. (2006). Predicting homework effort: support for a domain-specific, multilevel homework model. Journal of educational psychology , 98 (2), 438.

- Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Schneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2014). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. In Applications of flow in human development and education (pp. 475-494). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Daw, J. (2012). Parental income and the fruits of labor: Variability in homework efficacy in secondary school. Research in social stratification and mobility , 30 (3), 246-264.

- Rønning, M. (2011). Who benefits from homework assignments?. Economics of Education Review , 30 (1), 55-64.

- Calarco, J. M. (2020). Avoiding us versus them: How schools’ dependence on privileged “Helicopter” parents influences enforcement of rules. American Sociological Review , 85 (2), 223-246.

- Corno, L., & Xu, J. (2004). Homework as the job of childhood. Theory into practice , 43 (3), 227-233.

- Göllner, R., Damian, R. I., Rose, N., Spengler, M., Trautwein, U., Nagengast, B., & Roberts, B. W. (2017). Is doing your homework associated with becoming more conscientious?. Journal of Research in Personality , 71 , 1-12.

- Balli, S. J., Demo, D. H., & Wedman, J. F. (1998). Family involvement with children’s homework: An intervention in the middle grades. Family relations , 149-157.

- Balli, S. J., Wedman, J. F., & Demo, D. H. (1997). Family involvement with middle-grades homework: Effects of differential prompting. The Journal of Experimental Education , 66 (1), 31-48.

- Epstein, J. L., & Dauber, S. L. (1991). School programs and teacher practices of parent involvement in inner-city elementary and middle schools. The elementary school journal , 91 (3), 289-305.

- Van Voorhis, F. L. (2003). Interactive homework in middle school: Effects on family involvement and science achievement. The Journal of Educational Research , 96 (6), 323-338.

- Yogman, M., Garner, A., Hutchinson, J., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., & Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. (2018). The power of play: A pediatric role in enhancing development in young children. Pediatrics , 142 (3).

- Godakanda, I., Abeysena, C., & Lokubalasooriya, A. (2018). Sedentary behavior during leisure time, physical activity and dietary habits as risk factors of overweight among school children aged 14–15 years: case control study. BMC research notes , 11 (1), 1-6.

- Hadianfard, A. M., Mozaffari-Khosravi, H., Karandish, M., & Azhdari, M. (2021). Physical activity and sedentary behaviors (screen time and homework) among overweight or obese adolescents: a cross-sectional observational study in Yazd, Iran. BMC pediatrics , 21 (1), 1-10.

- Galloway, M., Conner, J., & Pope, D. (2013). Nonacademic effects of homework in privileged, high-performing high schools. The journal of experimental education , 81 (4), 490-510.

- Pressman, R. M., Sugarman, D. B., Nemon, M. L., Desjarlais, J., Owens, J. A., & Schettini-Evans, A. (2015). Homework and family stress: With consideration of parents’ self confidence, educational level, and cultural background. The American Journal of Family Therapy , 43 (4), 297-313.

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Battiato, A. C., Walker, J. M., Reed, R. P., DeJong, J. M., & Jones, K. P. (2001). Parental involvement in homework. Educational psychologist , 36 (3), 195-209.

- Moroni, S., Dumont, H., Trautwein, U., Niggli, A., & Baeriswyl, F. (2015). The need to distinguish between quantity and quality in research on parental involvement: The example of parental help with homework. The Journal of Educational Research , 108 (5), 417-431.

- Cooper, H., Lindsay, J. J., & Nye, B. (2000). Homework in the home: How student, family, and parenting-style differences relate to the homework process. Contemporary educational psychology , 25 (4), 464-487.

- Dumont, H., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Neumann, M., Niggli, A., & Schnyder, I. (2012). Does parental homework involvement mediate the relationship between family background and educational outcomes?. Contemporary Educational Psychology , 37 (1), 55-69.

- Barger, M. M., Kim, E. M., Kuncel, N. R., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2019). The relation between parents’ involvement in children’s schooling and children’s adjustment: A meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin , 145 (9), 855.

- Dumont, H., Trautwein, U., Nagy, G., & Nagengast, B. (2014). Quality of parental homework involvement: predictors and reciprocal relations with academic functioning in the reading domain. Journal of Educational Psychology , 106 (1), 144.

- Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). The effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes: a meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological bulletin , 134 (2), 270.Dettmars et al., 2010

- Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2016)

- Pomerantz, E. M., Grolnick, W. S., & Price, C. E. (2005). The Role of Parents in How Children Approach Achievement: A Dynamic Process Perspective.

- Haimovitz, K., Wormington, S. V., & Corpus, J. H. (2011). Dangerous mindsets: How beliefs about intelligence predict motivational change. Learning and Individual Differences , 21 (6), 747-752.Gollner et al., 2017

- Hill, N. E., & Tyson, D. F. (2009). Parental involvement in middle school: a meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental psychology , 45 (3), 740.

Share this post

Pingback: nfl|nfl highlights|nfl draft|nfl theme|nfl halftime show|nfl theme song|nfl draft 2023|nfl super bowl 2023|nfl 23|nfl 22|nfl halftime show 2022|nfl news|nfl live|nfl mock draft 2023|NFL player collapse|NFL live coverage|NFL Playoffs 2023|NFL game|NFL pred

Pingback: dutch driver license

Pingback: หวยออนไลน์ LSM99

Pingback: biracial silicone dolls

Comments are closed.

As psychologists, we were passionate about evidence-based parenting even before having kids ourselves. Once we became parents, we were overwhelmed by the amount of parenting information available, some of which isn’t backed by research. This inspired the Helping Families Thrive mission: to bring parenting science to the real world.

search the site

Learn With Us

Psychologist created, parent tested workshops and mini-courses to help families thrive.

Our comprehensive Essentials course puts the power of the most studied parenting tools in the palm of your hand.

post categories

Improve Your Child’s Emotion Regulation Skills

A free, 15-page guide filled with practical strategies.

find us elsewhere

find your way around

discover courses

important links

Our 3-Step Strategy

Download our free guide to improve your child’s cooperation.

For educational purposes only. Not intended to diagnose or treat any condition, illness or disease.

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

More than two hours of homework may be counterproductive, research suggests.

A Stanford education researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter. "Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good," wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education . The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students' views on homework. Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year. Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night. "The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students' advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being," Pope wrote. Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school. Their study found that too much homework is associated with: • Greater stress : 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor. • Reductions in health : In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems. • Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits : Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were "not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills," according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy. A balancing act The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills. Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as "pointless" or "mindless" in order to keep their grades up. "This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points," said Pope, who is also a co-founder of Challenge Success , a nonprofit organization affiliated with the GSE that conducts research and works with schools and parents to improve students' educational experiences.. Pope said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said. "Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development," wrote Pope. High-performing paradox In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. "Young people are spending more time alone," they wrote, "which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities." Student perspectives The researchers say that while their open-ended or "self-reporting" methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for "typical adolescent complaining" – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe. The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Clifton B. Parker is a writer at the Stanford News Service .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

Improving lives through learning

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Shop NewBeauty Reader’s Choice Awards winners — from $13

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Music Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

Is homework robbing your family of joy? You're not alone

Children are not the only ones who dread their homework these days. In a 2019 survey of 1,049 parents with children in elementary, middle, or high school, Office Depot found that parents spend an average of 21 minutes a day helping their children with their homework. Those 21 minutes are often apparently very unpleasant.

Parents reported their children struggle to complete homework. One in five believed their children "always or often feel overwhelmed by homework," and half of them reported their children had cried over homework stress.

Parents are struggling to help. Four out of five parents reported that they have had difficulty understanding their children's homework.

This probably comes as no surprise to any parent who has come up against a third grade math homework sheet with the word "array" printed on it. If you have not yet had the pleasure, for the purposes of Common Core math, an array is defined as a set of objects arranged in rows and columns and used to help kids learn about multiplication. For their parents, though, it's defined as a "What? Come again? Huh?"

It's just as hard on the students. "My high school junior says homework is the most stressful part of high school...maybe that’s why he never does any," said Mandy Burkhart, of Lake Mary, Florida, who is a mother of five children ranging in age from college to preschool.

In fact, Florida high school teacher and mother of three Katie Tomlinson no longer assigns homework in her classroom. "Being a parent absolutely changed the way I assign homework to my students," she told TODAY Parents .

"Excessive homework can quickly change a student’s mind about a subject they previously enjoyed," she noted. "While I agree a check and balance is necessary for students to understand their own ability prior to a test, I believe it can be done in 10 questions versus 30."

But homework is a necessary evil for most students, so what is a parent to do to ensure everyone in the house survives? Parents and professionals weigh in on the essentials:

Understand the true purpose of homework

"Unless otherwise specified, homework is designed to be done by the child independently, and it's most often being used as a form of formative assessment by the teacher to gauge how the kids are applying — independently — what they are learning in class," said Oona Hanson , a Los Angeles-area educator and parent coach.

"If an adult at home is doing the heavy lifting, then the teacher never knows that the child isn't ready to do this work alone, and the cycle continues because the teacher charges ahead thinking they did a great job the day before!" Hanson said. "It's essential that teachers know when their students are struggling for whatever reason."

Hanson noted the anxiety both parents and children have about academic achievement, and she understands the parental impulse to jump in and help, but she suggested resisting that urge. "We can help our kids more in the long run if we can let them know it's OK to struggle a little bit and that they can be honest with their teacher about what they don't understand," she said.

Never miss a parenting story with the TODAY Parenting newsletter! Sign up here.

Help kids develop time management skills

Some children like to finish their homework the minute they get home. Others need time to eat a snack and decompress. Either is a valid approach, but no matter when students decide to tackle their homework, they might need some guidance from parents about how to manage their time .

One tip: "Set the oven timer for age appropriate intervals of work, and then let them take a break for a few minutes," Maura Olvey, an elementary school math specialist in Central Florida, told TODAY Parents. "The oven timer is visible to them — they know when a break is coming — and they are visible to you, so you can encourage focus and perseverance." The stopwatch function on a smartphone would work for this method as well.

But one size does not fit all when it comes to managing homework, said Cleveland, Ohio, clinical psychologist Dr. Sarah Cain Spannagel . "If their child has accommodations as a learner, parents know they need them at home as well as at school: quiet space, extended time, audio books, etcetera," she said. "Think through long assignments, and put those in planners in advance so the kid knows it is expected to take some time."

Know when to walk away

"I always want my parents to know when to call it a night," said Amanda Feroglia, a central Florida elementary teacher and mother of two. "The children's day at school is so rigorous; some nights it’s not going to all get done, and that’s OK! It’s not worth the meltdown or the fight if they are tired or you are frustrated...or both!"

Parents also need to accept their own limits. Don't be afraid to find support from YouTube videos, websites like Khan Academy, or even tutors. And in the end, said Spannagel, "If you find yourself yelling or frustrated, just walk away!" It's fine just to let a teacher know your child attempted but did not understand the homework and leave it at that.

Ideally, teachers will understand when parents don't know how to help with Common Core math, and they will assign an appropriate amount of homework that will not leave both children and their parents at wits' ends. If worst comes to worst, a few parents offered an alternative tip for their fellow homework warriors.

"If Brittany leaves Boston for New York at 3:00 pm traveling by train at 80 MPH, and Taylor leaves Boston for New York at 1:00 pm traveling by car at 65 MPH, and Brittany makes two half hour stops, and Taylor makes one that is ten minutes longer, how many glasses of wine does mommy need?" quipped one mom of two.

Also recommended: "Chocolate, in copious amounts."

Allison Slater Tate is a freelance writer and editor in Florida specializing in parenting and college admissions. She is a proud Gen Xer, ENFP, Leo, Diet Coke enthusiast, and champion of the Oxford Comma. She mortifies her four children by knowing all the trending songs on TikTok. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram .

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

How important is homework, and how much should parents help?

Please try again

A version of this post was originally published by Parenting Translator. Sign up for the newsletter and follow Parenting Translator on Instagram .

In recent years, homework has become a very hot topic . Many parents and educators have raised concerns about homework and questioned how effective it is in enhancing students’ learning. There are also concerns that students may be getting too much homework, which ultimately interferes with quality family time and opportunities for physical activity and play . Research suggests that these concerns may be valid. For example, one study reported that elementary school students, on average, are assigned three times the recommended amount of homework.

So what does the research say? What are the potential risks and benefits of homework, and how much is too much?

Academic benefits

First, research finds that homework is associated with higher scores on academic standardized tests for middle and high school students, but not elementary school students . A recent experimental study in Romania found some benefit for a small amount of writing homework in elementary students but not math homework. Yet, interestingly, this positive impact only occurred when students were given a moderate amount of homework (about 20 minutes on average).

Non-academic benefits

The goal of homework is not simply to improve academic skills. Research finds that homework may have some non-academic benefits, such as building responsibility , time management skills, and task persistence . Homework may also increase parents’ involvement in their children’s schooling. Yet, too much homework may also have some negative impacts on non-academic skills by reducing opportunities for free play , which is essential for the development of language, cognitive, self-regulation and social-emotional skills. Homework may also interfere with physical activity and too much homework is associated with an increased risk for being overweight . As with the research on academic benefits, this research also suggests that homework may be beneficial when it is minimal.

What is the “right” amount of homework?

Research suggests that homework should not exceed 1.5 to 2.5 hours per night for high school students and no more than one hour per night for middle school students. Homework for elementary school students should be minimal and assigned with the aim of building self-regulation and independent work skills. Any more than this and homework may no longer have a positive impact.

The National Education Association recommends 10 minutes of homework per grade and there is also some experimental evidence that backs this up.

Overall translation

Research finds that homework provides some academic benefit for middle and high school students but is less beneficial for elementary school students. Research suggests that homework should be none or minimal for elementary students, less than one hour per night for middle school students, and less than 1.5 to 2.5 hours for high school students.

What can parents do?

Research finds that parental help with homework is beneficial but that it matters more how the parent is helping rather than how often the parent is helping.

So how should parents help with homework, according to the research?

- Focus on providing general monitoring, guidance and encouragement, but allow children to generate answers on their own and complete their homework as independently as possible . Specifically, be present while they are completing homework to help them to understand the directions, be available to answer simple questions, or praise and acknowledge their effort and hard work. Research shows that allowing children more autonomy in completing homework may benefit their academic skills.

- Only provide help when your child asks for it and step away whenever possible. Research finds that too much parental involvement or intrusive and controlling involvement with homework is associated with worse academic performance .

- Help your children to create structure and develop some routines that help your child to independently complete their homework . Have a regular time and place for homework that is free from distractions and has all of the materials they need within arm’s reach. Help your child to create a checklist for homework tasks. Create rules for homework with your child. Help children to develop strategies for increasing their own self-motivation. For example, developing their own reward system or creating a homework schedule with breaks for fun activities. Research finds that providing this type of structure and responsiveness is related to improved academic skills.

- Set specific rules around homework. Research finds an association between parents setting rules around homework and academic performance.

- Help your child to view homework as an opportunity to learn and improve skills. Parents who view homework as a learning opportunity (that is, a “mastery orientation”) rather than something that they must get “right” or complete successfully to obtain a higher grade (that is, a “performance orientation”) are more likely to have children with the same attitudes.

- Encourage your child to persist in challenging assignments and emphasize difficult assignments as opportunities to grow . Research finds that this attitude is associated with student success. Research also indicates that more challenging homework is associated with enhanced academic performance.

- Stay calm and positive during homework. Research shows that mothers showing positive emotions while helping with homework may improve children’s motivation in homework.

- Praise your child’s hard work and effort during homework. This type of praise is likely to increase motivation. In addition, research finds that putting more effort into homework may be associated with enhanced development of conscientiousness in children.

- Communicate with your child and the teacher about any problems your child has with homework and the teacher’s learning goals. Research finds that open communication about homework is associated with increased academic performance.

Cara Goodwin, PhD, is a licensed psychologist, a mother of three and the founder of Parenting Translator , a nonprofit newsletter that turns scientific research into information that is accurate, relevant and useful for parents.

K-12 Resources By Teachers, For Teachers Provided by the K-12 Teachers Alliance

- Teaching Strategies

- Classroom Activities

- Classroom Management

- Technology in the Classroom

- Professional Development

- Lesson Plans

- Writing Prompts

- Graduate Programs

The Value of Parents Helping with Homework

Dr. selena kiser.

- September 2, 2020

The importance of parents helping with homework is invaluable. Helping with homework is an important responsibility as a parent and directly supports the learning process. Parents’ experience and expertise is priceless. One of the best predictors of success in school is learning at home and being involved in children’s education. Parental involvement with homework helps develop self-confidence and motivation in the classroom. Parents helping students with homework has a multitude of benefits including spending individual time with children, enlightening strengths and weaknesses, making learning more meaningful, and having higher aspirations.

How Parental Involvement with Homework Impacts Students

Parental involvement with homework impacts students in a positive way. One of the most important reasons for parental involvement is that it helps alleviate stress and anxiety if the students are facing challenges with specific skills or topics. Parents have experience and expertise with a variety of subject matter and life experiences to help increase relevance. Parents help their children understand content and make it more meaningful, while also helping them understand things more clearly.

Also, their involvement increases skill and subject retention. Parents get into more depth about content and allow students to take skills to a greater level. Many children will always remember the times spent together working on homework or classroom projects. Parental involvement with homework and engagement in their child’s education are related to higher academic performance, better social skills and behavior, and increased self-confidence.

Parents helping with homework allows more time to expand upon subjects or skills since learning can be accelerated in the classroom. This is especially true in today’s classrooms. The curricula in many classrooms is enhanced and requires teaching a lot of content in a small amount of time. Homework is when parents and children can spend extra time on skills and subject matter. Parents provide relatable reasons for learning skills, and children retain information in greater depth.

Parental involvement increases creativity and induces critical-thinking skills in children. This creates a positive learning environment at home and transfers into the classroom setting. Parents have perspective on their children, and this allows them to support their weaknesses while expanding upon their strengths. The time together enlightens parents as to exactly what their child’s strengths and weaknesses are.

Virtual learning is now utilized nationwide, and parents are directly involved with their child’s schoolwork and homework. Their involvement is more vital now than ever. Fostering a positive homework environment is critical in virtual learning and assists children with technological and academic material.

Strategies for Including Parents in Homework

An essential strategy for including parents in homework is sharing a responsibility to help children meet educational goals. Parents’ commitment to prioritizing their child’s educational goals, and participating in homework supports a larger objective. Teachers and parents are specific about the goals and work directly with the child with classwork and homework. Teachers and parents collaboratively working together on children’s goals have larger and more long-lasting success. This also allows parents to be strategic with homework assistance.

A few other great examples of how to involve parents in homework are conducting experiments, assignments, or project-based learning activities that parents play an active role in. Interviewing parents is a fantastic way to be directly involved in homework and allows the project to be enjoyable. Parents are honored to be interviewed, and these activities create a bond between parents and children. Students will remember these assignments for the rest of their lives.

Project-based learning activities examples are family tree projects, leaf collections, research papers, and a myriad of other hands-on learning assignments. Children love working with their parents on these assignments as they are enjoyable and fun. This type of learning and engagement also fosters other interests. Conducting research is another way parents directly impact their child’s homework. This can be a subject the child is interested in or something they are unfamiliar with. Children and parents look forward to these types of homework activities.

Parents helping students with homework has a multitude of benefits. Parental involvement and engagement have lifelong benefits and creates a pathway for success. Parents provide autonomy and support, while modeling successful homework study habits.

- #homework , #ParentalInvolvement

More in Professional Development

How Sensory Rooms Help Students with Autism Thrive

Students with autism often face challenges in the classroom due to their sensory…

Establishing a Smooth Flow: The Power of Classroom Routines

Learners thrive in environments where there’s structure and familiarity, and implementing classroom routines…

The Benefits of Learning a Foreign Language

One of my favorite memories from my time in high school was when…

How to Enhance Working Memory in your Classroom

Enhancing working memory is vital in the learning process of all classrooms. There…

The New York Times

Motherlode | when homework stresses parents as well as students, when homework stresses parents as well as students.

Educators and parents have long been concerned about students stressed by homework loads , but a small research study asked questions recently about homework and anxiety of a different group: parents. The results were unsurprising. While we may have already learned long division and let the Magna Carta fade into memory, parents report that their children’s homework causes family stress and tension — particularly when additional factors surrounding the homework come into play.

The researchers, from Brown University, found that stress and tension for families (as reported by the parents) increased most when parents perceived themselves as unable to help with the homework, when the child disliked doing the homework and when the homework caused arguments, either between the child and adults or among the adults in the household.

The number of parents involved in the research (1,173 parents, both English and Spanish-speaking, who visited one of 27 pediatric practices in the greater Providence area of Rhode Island) makes it more of a guide for further study than a basis for conclusions, but the idea that homework can cause significant family stress is hard to seriously debate. Families across income and education levels may struggle with homework for different reasons and in different ways, but “it’s an equal opportunity problem,” says Stephanie Donaldson-Pressman , a contributing editor to the research study and co-author of “ The Learning Habit .”

“Parents may find it hard to evaluate the homework,” she says. “They think, if this is coming home, my child should be able to do it. If the child can’t, and especially if they feel like they can’t help, they may get angry with the child, and the child feels stupid.” That’s a scenario that is likely to lead to more arguments, and an increased dislike of the work on the part of the child.

The researchers also found that parents of students in kindergarten and first grade reported that the children spent significantly more time on homework than recommended. Many schools and organizations, including the National Education Association and the Great Schools blog , will suggest following the “10-minute rule” for how long children should spend on school work outside of school hours: 10 minutes per grade starting in first grade, and most likely more in high school. Instead, parents described their first graders and kindergartners working, on average, for 25 to 30 minutes a night. That is consistent with other research , which has shown an increase in the amount of time spent on homework in lower grades from 1981 to 2003.

“This study highlights the real discrepancy between intent and what’s actually happening,” Ms. Donaldson-Pressman said, speaking of both the time spent and the family tensions parents describe. “When people talk about the homework, they’re too often talking about the work itself. They should be talking about the load — how long it takes. You can have three problems on one page that look easy, but aren’t.”

The homework a child is struggling with may not be developmentally appropriate for every child in a grade, she suggests, noting that academic expectations for young children have increased in recent years . Less-educated or Spanish-speaking parents may find it harder to evaluate or challenge the homework itself, or to say they think it is simply too much. “When the load is too much, it has a tremendous impact on family stress and the general tenor of the evening. It ruins your family time and kids view homework as a punishment,” she said.

At our house, homework has just begun; we are in the opposite of the honeymoon period, when both skills and tolerance are rusty and complaints and stress are high. If the two hours my fifth-grade math student spent on homework last night turn out the be the norm once he is used to the work and the teacher has had a chance to hear from the students, we’ll speak up.

We should, Ms. Donaldson-Pressman says. “Middle-class parents can solve the problem for their own kids,” she says. “They can make sure their child is going to all the right tutors, or get help, but most people can’t.” Instead of accepting that at home we become teachers and homework monitors (or even taking classes in how to help your child with his math ), parents should let the school know that they’re unhappy with the situation, both to encourage others to speak up and to speak on behalf of parents who don’t feel comfortable complaining.

“Home should be a safe place for students,” she says. “A child goes to school all day and they’re under stress. If they come home and it’s more of the same, that’s not good for anyone.”

Read more about homework on Motherlode: Homework and Consequences ; The Mechanics of Homework ; That’s Your Child’s Homework Project, Not Yours and Homework’s Emotional Toll on Students and Families.

What's Next

Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Should Kids Get Homework?

Homework gives elementary students a way to practice concepts, but too much can be harmful, experts say.

Getty Images

Effective homework reinforces math, reading, writing or spelling skills, but in a way that's meaningful.

How much homework students should get has long been a source of debate among parents and educators. In recent years, some districts have even implemented no-homework policies, as students juggle sports, music and other activities after school.

Parents of elementary school students, in particular, have argued that after-school hours should be spent with family or playing outside rather than completing assignments. And there is little research to show that homework improves academic achievement for elementary students.

But some experts say there's value in homework, even for younger students. When done well, it can help students practice core concepts and develop study habits and time management skills. The key to effective homework, they say, is keeping assignments related to classroom learning, and tailoring the amount by age: Many experts suggest no homework for kindergartners, and little to none in first and second grade.

Value of Homework

Homework provides a chance to solidify what is being taught in the classroom that day, week or unit. Practice matters, says Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University 's Wheelock College of Education & Human Development.

"There really is no other domain of human ability where anybody would say you don't need to practice," she adds. "We have children practicing piano and we have children going to sports practice several days a week after school. You name the domain of ability and practice is in there."

Homework is also the place where schools and families most frequently intersect.

"The children are bringing things from the school into the home," says Paula S. Fass, professor emerita of history at the University of California—Berkeley and the author of "The End of American Childhood." "Before the pandemic, (homework) was the only real sense that parents had to what was going on in schools."

Harris Cooper, professor emeritus of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University and author of "The Battle Over Homework," examined more than 60 research studies on homework between 1987 and 2003 and found that — when designed properly — homework can lead to greater student success. Too much, however, is harmful. And homework has a greater positive effect on students in secondary school (grades 7-12) than those in elementary.

"Every child should be doing homework, but the amount and type that they're doing should be appropriate for their developmental level," he says. "For teachers, it's a balancing act. Doing away with homework completely is not in the best interest of children and families. But overburdening families with homework is also not in the child's or a family's best interest."

Negative Homework Assignments

Not all homework for elementary students involves completing a worksheet. Assignments can be fun, says Cooper, like having students visit educational locations, keep statistics on their favorite sports teams, read for pleasure or even help their parents grocery shop. The point is to show students that activities done outside of school can relate to subjects learned in the classroom.

But assignments that are just busy work, that force students to learn new concepts at home, or that are overly time-consuming can be counterproductive, experts say.

Homework that's just busy work.

Effective homework reinforces math, reading, writing or spelling skills, but in a way that's meaningful, experts say. Assignments that look more like busy work – projects or worksheets that don't require teacher feedback and aren't related to topics learned in the classroom – can be frustrating for students and create burdens for families.

"The mental health piece has definitely played a role here over the last couple of years during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the last thing we want to do is frustrate students with busy work or homework that makes no sense," says Dave Steckler, principal of Red Trail Elementary School in Mandan, North Dakota.

Homework on material that kids haven't learned yet.

With the pressure to cover all topics on standardized tests and limited time during the school day, some teachers assign homework that has not yet been taught in the classroom.

Not only does this create stress, but it also causes equity challenges. Some parents speak languages other than English or work several jobs, and they aren't able to help teach their children new concepts.

" It just becomes agony for both parents and the kids to get through this worksheet, and the goal becomes getting to the bottom of (the) worksheet with answers filled in without any understanding of what any of it matters for," says professor Susan R. Goldman, co-director of the Learning Sciences Research Institute at the University of Illinois—Chicago .

Homework that's overly time-consuming.

The standard homework guideline recommended by the National Parent Teacher Association and the National Education Association is the "10-minute rule" – 10 minutes of nightly homework per grade level. A fourth grader, for instance, would receive a total of 40 minutes of homework per night.

But this does not always happen, especially since not every student learns the same. A 2015 study published in the American Journal of Family Therapy found that primary school children actually received three times the recommended amount of homework — and that family stress increased along with the homework load.

Young children can only remain attentive for short periods, so large amounts of homework, especially lengthy projects, can negatively affect students' views on school. Some individual long-term projects – like having to build a replica city, for example – typically become an assignment for parents rather than students, Fass says.

"It's one thing to assign a project like that in which several kids are working on it together," she adds. "In (that) case, the kids do normally work on it. It's another to send it home to the families, where it becomes a burden and doesn't really accomplish very much."

Private vs. Public Schools

Do private schools assign more homework than public schools? There's little research on the issue, but experts say private school parents may be more accepting of homework, seeing it as a sign of academic rigor.

Of course, not all private schools are the same – some focus on college preparation and traditional academics, while others stress alternative approaches to education.

"I think in the academically oriented private schools, there's more support for homework from parents," says Gerald K. LeTendre, chair of educational administration at Pennsylvania State University—University Park . "I don't know if there's any research to show there's more homework, but it's less of a contentious issue."

How to Address Homework Overload

First, assess if the workload takes as long as it appears. Sometimes children may start working on a homework assignment, wander away and come back later, Cooper says.

"Parents don't see it, but they know that their child has started doing their homework four hours ago and still not done it," he adds. "They don't see that there are those four hours where their child was doing lots of other things. So the homework assignment itself actually is not four hours long. It's the way the child is approaching it."

But if homework is becoming stressful or workload is excessive, experts suggest parents first approach the teacher, followed by a school administrator.

"Many times, we can solve a lot of issues by having conversations," Steckler says, including by "sitting down, talking about the amount of homework, and what's appropriate and not appropriate."

Study Tips for High School Students

Tags: K-12 education , students , elementary school , children

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

Applications for THINK Summer Institute Closing Soon

The application deadline has been extended to April 12 for MATH 181 and ANTH 222!

Costs and Benefits of Family Involvement in Homework

This paper presents the results of three 2-year longitudinal interventions of the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) homework program in elementary mathematics, middle school language arts, and middle school science. The findings suggest that the benefits of TIPS intervention in terms of emotion and achievement outweigh its associated costs.

Author: Van Voorhis, F. L. Publication: Journal of Advanced Academics Publisher: Prufrock Press, Inc. Volume: Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 220-249 Year: Winter 2011

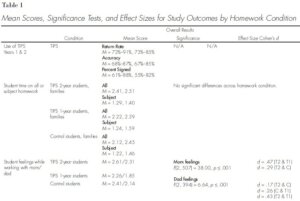

Homework represents one research-based instructional strategy linked to student achievement. However, challenges abound with its current practice. This paper presents the results of three 2-year longitudinal interventions of the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) homework program in elementary mathematics, middle school language arts, and middle school science. Each weekly standards-related TIPS assignment included specific instructions for students to involve a family partner in a discussion, interview, experiment, or other interaction. Depending on subject and grade level, TIPS students returned between 72% and 91% of TIPS activities, and families signed between 55% and 83% of TIPS assignments. TIPS students and families responded significantly more positively than controls to questions about their emotions and attitudes about the homework experience, and TIPS families and students reported higher levels of family involvement in the TIPS subject. No differences emerged in the amount of time students spent on subject homework across the homework groups, but students using TIPS for 2 years earned significantly higher standardized test scores than did controls. The findings suggest that the benefits of TIPS intervention in terms of emotion and achievement outweigh its associated costs.

What factors affect student academic achievement? Research indicates that in addition to classroom instruction and students’ responses to class lessons, homework is one important factor that increases achievement (Marzano, 2003; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008). According to Cooper, homework involves tasks assigned to students by schoolteachers that are meant to be carried out during noninstructional time (Bembenutty, 2011). Although results vary, meta-analytic studies of homework effects on student achievement report percentile gains for students between 8% and 31% (Marzano & Pickering, 2007). If homework serves a clear benefit for students, it is puzzling why there are persistent discussions and contention about its practice (Bennett & Kalish, 2006; Kohn, 2006; Kralovec & Buell, 2000). Homework requires students, teachers, and parents to invest time and effort on assignments. Their views about homework vary. On a positive note, 90% of teachers, students, and parents believe homework will help students reach important goals. Yet, 26% of students, 24% of teachers, and 40% of parents report that some homework is just busywork, and 29% of parents report homework is a “major source of stress” (Markow, Kim, & Liebman, 2007, p. 15).

It is critical, then, to improve current practice and for educators and researchers to examine the emotional and cognitive costs and benefits of homework for students, families, and teachers (Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2001; Van Voorhis, 2004, 2009, in press; Van Voorhis & Epstein, 2002). The purpose of this paper is to describe the results of one homework intervention designed to ease some homework tensions between students and families. The Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) interactive homework process draws on the theory of overlapping spheres of influence , which stipulates that students do better in school when parents, educators, and others in the community work together to guide and support student learning and development. In this model, three contexts—home, school, and community—have unique (nonoverlapping) and combined (overlapping) influences on children’s learning and development through the interactions of parents, educators, community partners, and students. Each context moves closer or farther from the others as a result of external forces and practices that encourage or discourage the internal interactions of the partners in children’s education (Epstein, 2011; Sanders, Sheldon, & Epstein, 2005).

Three aspects of homework that entail costs and or produce benefits for home and school contexts are time, homework design, and family involvement. A common complaint about homework, and one of the most studied factors, is time on homework. Data on the time students spend on homework vary based on who reports it (Bembenutty, 2009; Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2001; Kitsantas & Zimmerman, 2009; Warton, 2001; Xu, 2009), as do recommendations about sensible requirements for time on homework. Specifically, parents of elementary students have a fair sense of their children’s homework responsibilities, but in the secondary grades, parents often underestimate the frequency of homework assignments and overestimate the time their children spend (Markow et al., 2007).

Some teachers tend to underestimate how often families are involved. In one study of middle school students, parents helped their children with homework, on average, between one and three times per week and checked homework four times per week (Eccles & Harold, 1996). Students reported working with their parents on schoolwork between one and three times weekly. However, students reported that teachers asked them to request parental assistance only one to two times per month on tasks such as checking homework, studying for tests, or working on projects.

These discrepancies are just one example of homework communication problems among all parties involved. Overall, like many education issues, a percentage of students at all grade levels (5% of 9-year-olds, 8% of 13-year-olds, and 11% of 17-year-olds) spend a lot of time on homework (> 2 hours per night); others complete none at all or fail to complete assigned work (24% to 39%); and many are right in the middle, completing less than 1 hour (28% to 60%) or between 1 and 2 hours per night (13% to 22%; Perie & Moran, 2005). Some studies conducted on the relationship of time on homework and achievement find that the age of the student moderates the relationship. Specifically, the homework and achievement relationship is stronger and positive for secondary students and negative or null for elementary students (Cooper, 1989; Cooper, Robinson, & Patall, 2006). The studies have resulted in different time expectations for younger and older students. Many schools have adopted the 10-minute rule as a general guide for developmentally appropriate time on homework (Henderson, 1996). For example, students in the elementary and middle grades should be assigned roughly 10 minutes multiplied by the grade level (i.e., 30 minutes for a third-grade student), while high school student assignment time varies by subject. The time differences also raise some questions about different purposes and content of homework across the grades.

Issues of purpose and content relate to the next topic, homework design. There are instructional (practice, preparation, participation, and personal development) and noninstructional or nonacademic (Corno & Xu, 2004) purposes of homework (parent-child relations, parent-teacher communications, policy; Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2001). Not surprisingly, more than 70% of homework assignments by teachers at all levels of schooling are designed for the purpose of students finishing classwork or practicing skills (Polloway, Epstein, Bursuck, Madhavi, & Cumblad, 1994). Homework in the early grades should encourage positive attitudes and character traits, allow appropriate parent involvement, and reinforce simple skills introduced in class (Cooper, 2007). For secondary grades, homework should work toward improving standardized test scores and grades. Teachers report that the homework process needs to improve, and that they would like time to ensure that assignments are relevant to the course and topic of study; build in time for feedback on assignments daily; and establish effective policies at the curriculum, grade, and school levels (Markow et al., 2007, p. 136).

Homework design also needs to develop the third topic— family involvement in the homework process. Families report that homework costs them time and energy when teachers fail to explain the assignment to students in class, assignments do not relate to classwork, or when students are unsure about how to complete it. Parents report that they sometimes provide poor or inappropriate help, often feel unprepared to help with certain subjects (Hoover-Dempsey, Bassler, & Burow, 1995; Markow et al., 2007), and sometimes spend time trying to motivate their children to complete their homework by making the assignment more interesting. The quality of the family-student interactions not only affect students’ completion of homework and achievement, but also children’s emotional and social functioning (Pomerantz, Moorman, & Litwack, 2007).

Kenney-Benson and Pomerantz (2005) simulated a lab homework experience and found that elementary students with mothers who were involved in an autonomy-supportive manner were less likely to experience depressive symptoms than children with controlling mothers. Similarly, junior high students who perceived their parents as supportive of their academic endeavors exhibited less acting-out behavior (Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994). In fact, parents of both elementary and middle grade students reported that they would help their children more if the teacher guided them in how they could help at home (Dauber & Epstein, 1993; Kay, Fitzgerald, Paradee, & Mellencamp, 1994).

Aim of the Study

This present discussion of homework suggests that issues of time, design, and family involvement can influence students’ homework experiences and the results of their efforts. This study presents the results of a homework intervention that helps teachers consider issues of time, design, and family involvement in their assignments for students. Three 2-year intervention studies of the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) Interactive Homework process were conducted—the first longitudinal studies of the TIPS process. This study summarizes the findings from the three studies combined, looking across the elementary and middle grades, three courses, and diverse community contexts to address three main research questions:

- Students’ work: What percent of TIPS activities were completed and how well? How much time was invested by students?

- Student and family emotional investments: How did emotions and attitudes about homework compare for TIPS and control groups?

- Student outcomes: How did student achievement(s) compare for TIPS and control groups over 2 years?

Overall, given the attention to student and family roles in homework and a regular schedule of weekly, standards-based interactive homework, it was hypothesized that the students and families in the TIPS groups would experience more positive emotional homework interactions and higher achievement than the students and families in the control group.

Participants The sample included students in an elementary mathematics intervention in third and fourth grades (Van Voorhis, 2009, in press), a middle school language arts intervention in sixth and seventh grades (Van Voorhis, 2009), and a middle school science intervention in seventh and eighth grades (Van Voorhis, 2008). This combined study sample included only students who participated in 2 years of the study who were control students (no use of TIPS either year), TIPS 1-year students (TIPS in either Year 1 or 2), and TIPS 2-year students (TIPS use both years). All three studies—the elementary math (2004–2006), middle school language arts (2005–2007), and middle school science study (2006–2008)—took place in schools in urban southeastern school districts. There were 4 similar elementary schools (grades K–5); and 5 middle schools (grades 6–8). At each school, teachers were randomly assigned to implement either the TIPS interactive homework assignments weekly along with other homework or to serve as control teachers and assign only regular, noninteractive homework assignments. Thus, teachers were randomly assigned to the intervention and control conditions. Although students were not randomly assigned to classrooms, every effort was made to select similar, average classrooms of students.

The full sample included 575 students in 9 schools. Overall, 30% of the sample represented control students, 35% were TIPS 1-year students, and 35% were TIPS 2-year students. Elementary math students comprised 16% of the sample, 49% were middle school language arts students, and 35% were middle school science students. Fifty-seven percent of students received free or reduced-price meals, and 51% of students were male. The majority of students (52%) were African American, 42% were White, and 6% were Hispanic. The average previous standardized test score of students was 51.8%. Eighty-one percent of the full sample of students represented average-achieving students, 11% represented gifted students, and the remaining 8% of students were below average.

Each year, teachers administered student and family surveys on attitudes about homework in general and TIPS homework in specific subjects. Eighty-nine percent of students in Years 1 and 2 returned surveys, and 80% of families in Year 1 and 65% of families in Year 2 completed them. Overall, 36 teachers served as TIPS (19) or control (17) teachers over the course of the study, 44% of whom taught elementary math, 36% taught middle school language arts, and 20% taught middle school science. These teachers had taught an average of 13 years and had worked at their respective schools an average of 6 years.

TIPS Intervention

For one week during the summer prior to the start of each TIPS year, the author provided professional development to the TIPS teachers in each subject area to enable them to understand the research on homework, designs for interactive homework, and to adapt and/or develop TIPS activities based on their own district’s curriculum objectives. All TIPS activities, regardless of subject, include four common components: letter to family partner, various kinds of student-led interactions, home-to-school communication, and parent/guardian signature (Epstein et al., 2009). In each activity, students and families are instructed where an interaction (i.e., discussion, interview, survey, experiment) is to occur and the roles the student and family partner play in the interaction. For example, in a third-grade math activity, students practice counting money and writing it in two ways. The student completes several practice problems independently and shows his work on two of them to his family partner. Then, the student and family partner each put a few coins in their hands. The student counts both his coins as well as the family partner’s and records the answers. For a middle school science activity, the student examines a chart of physical, social, emotional, and intellectual changes and records the changes she has observed in life. The student and family partner then discuss questions like “Which changes are you happy about, and which changes are you least happy about?”

Two-way communications are encouraged in home-to-school communication that invites the family partner to share comments and observations with teachers about whether the child understood the homework, whether he enjoyed the activity, and whether the parent gained information about the student’s classwork.

Teachers designed each interactive TIPS activity for two sides of one page, linked them to the curriculum and to class lessons, and described them as the student’s responsibility to complete despite the request for family involvement in certain sections. Teachers also assigned point values to questions in all TIPS assignments to provide consistency in grading across teachers.

TIPS condition. During the summer work time, the TIPS teachers wrote a letter to the families of students in their classes. This letter included information on the weekly use of TIPS, the grading schedule, and the expectation for a family partner to participate with the student. Teachers of TIPS students in the math and language arts studies assigned one assignment weekly for a total of 30 TIPS activities each year, in addition to their other homework. Students in the control group completed homework as usual. More specifically, for the elementary math and language arts studies, teachers in the control group used their normal homework practices and homework. In discussion with these teachers prior to the school year, the author learned that they rarely asked families to be involved in homework. For both subjects, control and TIPS teachers generally assigned worksheets and problem sets to practice math facts and concepts introduced in class or worksheets and writing assignments for language arts. Both TIPS teachers and teachers in the control group assigned homework almost every week night, with TIPS teachers assigning TIPS once a week and the control group teachers assigning an independent activity. Science homework occurred less frequently, generally once or twice per week. Like the other studies, control science teachers assigned an independent assignment while TIPS teachers assigned the TIPS activities, at most once per week. In this study, TIPS students completed 24 activities in Year 1 and 17 in Year 2.

Teachers graded TIPS and all other homework and provided these data to the author every 9 weeks. At the end of each school year, TIPS students, families, and teachers completed an end-ofyear survey on homework in the TIPS subject.