Join our newsletter!

The Intertwined Relationship Between Music And Politics

The very nature of politics is, like music, rooted in conflict and harmony. The heart of music is the interplay of the physical and the mental, as the compromise between them forms a cohesive whole. Compromise is also the heart of the political process, trying to find common ground and consensus solutions to problems of society through open communication. Both seek to inspire their targets, and both have made great use of the other to advance their ideas. While we encourage you all to go out and vote today, we thought it would be a fine time to examine the way music and politics have become strangely entwined.

The relationship between music and politics has existed for centuries, sometimes harmoniously, and other times not as much. Historical records are full of examples of songs that laud the achievements of nations, dating all the way back to ancient Egypt. On the other hand, however, songwriters have turned to their craft when confronted with social and political unjustness, and give birth to songs that seek to shine a light on the perceived inequities of the day. From protest songs to voter campaigns, campaign rallies to musical endorsements and musicians campaigning, there’s been no shortage of love between music and politics.

Protest songs

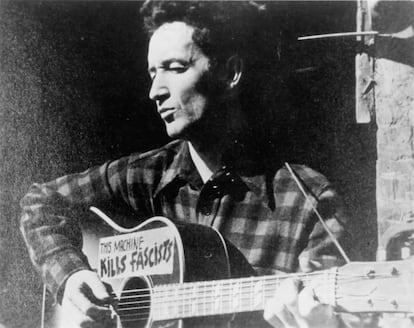

As a form of communication, music has always been used to express opinions about matters of the day. I’m sure the first caveman quartet did a scathing tune about Ogg’s lack of leadership in the “ Firegate ” debacle. There have been plenty of songs, jingles mostly, endorsing individual candidates and causes, but it seems Rather than turn this into a history lesson, we’ll focus on some of the more modern songs that have shaped the musical political climate. That said, we need to acknowledge a true pioneer of the American musical protest movement, Woody Guthrie .

This Oklahoma born singer-songwriter-poet sang in a plain, dead pan drawl that perfectly captured the message he was speaking of fighting to keep America free. His guitar often spoke the words for him, with the words “ This Machine Destroys Fascists ” emblazoned across it. It was a powerful and prescient commentary on the ability music has to rally people to a cause , and Guthrie set a precedent many would follow on the years to come.

Before Guthrie’s rabble-rousing, popular music was very pro-establishment, pro-government and even pro-war. Though some singers like Billie Holiday managed to sneak issues of civil rights and institutionalized racism into the conversation through songs like “Strange Fruit,” those were rare occasions. For much of America’s history up to the early fifties, music was primarily a tool of patriotism. Our own national anthem features evocative imagery of war, bursting bombs and gallantly defended ramparts. Using uplifting arrangements and calls to national pride, many a man found himself standing in line at the recruitment office, as radio speakers called for them to join the fight “ Over There. ”

Most of the sixties saw America at war, and the music world was the symbolic centerpiece of an anti-establishment movement. The promise of the beginning of the decade was silenced by gunfire, and the effect that constant strife had on the psyche of the budding musicians across the nation was immeasurable. Voices were raised from every gender, every race asking for equality, freedom and peace. These songs made an unprecedented leap to the top of the charts, cacallingor the people of America to let go of their old ways; to learn and grow. Bob Dylan put it best in his classic “ The Times They Are A Changin ‘”

The tumult of the sixties was a direct result of a generation born from the returning soldiers of the second World War. The horrors endured by their parents turned them against the conflict, but after an entire decade of railing against the military industrial complex and unjust wars abroad, a sense of disillusionment came over the country and the era of the protest song slowly faded away. It’s no wonder that John Lennon’s “Give Peace A Chance” became such an anthem at the end of a difficult decade.

The American counterculture war veterans were slowly getting lost in the so called “Me Decade” of self indulgence that was the seventies. Though the flames of protest seemed to cool after the conflagration of the sixties, the fires still burned bright overseas. In England, a wave of anarchic music gave voice to the growing sentiment of disillusionment and distrust among the increasingly angry youth. Jobs were scarce, especially for the young and untrained. The combination of youthful energy and lack of any positive release turned the country into a simmering stew of resentment. Protesters took to the streets, as an increasingly radical populace carried out acts of building aggression towards the elite. Punk rockers the Sex Pistols were born of that rage, and vented it in their seminal hit “ God Save The Queen. ”

Check it out below:

The eighties were a dark time for America, politically. Populist Republican Ronald Reagan had steamrolled into the Oval Office over Jimmy Carter in a landslide victory. Carter’s presidency was beset by scandals like the Iranian hostage situation, gas shortages and public perception of him as indecisive. Reagan’s simple, jingoistic message of recapturing America’s strength and charismatic, fatherly demeanor covered up his indifference to anyone outside of the middle and upper classes. From his slow reaction to the AIDS outbreaks, allowing the CIA to help worsen the drug epidemic in the inner cities to his economic policies that drained the nations social programs to the needy, the Regan White house did little to help a large portion of his constituents.

As part of his “War On Drugs,” police forces became increasingly militant, sentences for drug crimes became longer and longer and groups like N.W.A spoke the words that had been on the minds of so many for so very long. N.W.A spawned a new wave of hip hop, with socially aware and often violent lyrical content. Suddenly the people of the inner cities had a voice for protest, and the music was also incredibly popular. Hip Hop and Rap brought issues of race to the forefront in a new and viceral way. Thanks to it’s appeal across racial lines, it’s almost impossible to truly judge how important the impact of bringing these topics to the national discussion. But not all music needs to be for or against something for it to have a profound political impact.

Music For Voting

In 1990 Rock The Vote , a new, non partisan non-profit was founded to promote voter registration among the America’s youth. Their marketing snazzy blend of big name band and artist endorsements and political activism worked well out of the gate with their debut PSA featuring Madonna in dressed only in her underwear and the American flag. Check it out below:

With the most popular artists of all genres sharing the same message, a new generation realized that they could be a huge part of the process as well. In 1992 President Bill Clinton was elected, after garnering a large lead among young voters, thanks, in part, to the 1993 National Voter Registration Act, which gave potential voters a chance to register when they visited the Department Of Motor Vehicles. In 1999 they helped voters across the nation once again, helping create an online registration tool that anyone of age could easily use. This sort of bipartisan effort to make it easier for folks to do their civic duty is a noble example of the spirit of music being used to help society as a whole.

In 2004, Disco Biscuits bassist Marc Brownstein and his friend Andy Bernstein founded the nationwide non-profit HeadCount. In many ways, HeadCount was the next logical step forward along the path started by Rock The Vote. This new activist group takes registering to vote to the people, setting up shop at concerts and festivals around the nation. Keeping themselves non-partisan, HeadCount has set up registration booths at concerts and festivals all across the country, using an ever growing army of volunteers who see the value of a politically vocal population. Their methodology is a mix of old school registration booths and canvassing crowds with clipboards and more modern techniques like hosting concerts, on line media campaigns and television ads. The end result, over 300,000 voters registered, is an achievement all involved are proud of.

The good work done by HeadCount hasn’t gone unnoticed by the rest of the music community. The list of artists who have acted as spokespeople and opened space at their shows for the organization reads like a who’s who’s of the music world. A diverse array that includes main stream acts like Jay-Z , Pearl Jam , Tom Petty and Dave Matthews stand alongside Brownstein’s contemporaries from the jam scene like Phish , String Cheese Incident , and Umphrey’s McGee. Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir was an early advocate for HeadCount, appearing in ads, urging his audiences to participate in the election process, and now he serves on the board of directors .

Here’s fun interview from Marc Brownstein early in the life of the now 12 year old HeadCount:

On The Campaign Trail (Today)

Music is an vital part of every campaign stop. Every aspect of an election campaign stop is planned down to the tiniest detail. Candidates and their handlers plan not just what they’re going to say, but HOW they’re going to say it, what clothes they’ll be wearing and exactly what they’ll be standing in front of when they share the message.

From marching bands to rock anthems, candidates from every party seek to stir up the passions of potential voters using music. Any advertising executive will tell you that the right song played at the right moment will subliminally evoke emotions of trust and empathy in the listener. Music is such a key element of swaying the hearts and minds of people that quite often campaigns will rush to play songs they don’t have permission to play. It seems like every election cycle features at least one artist having to stop an overzealous candidate with opposing views to stop using their material at their events.

Republican party front runner, real estate developer and reality TV personality Donald Trump is no stranger to stepping on toes. His brash and arrogant style and controversial proposals have fiercely divided the country, and in his efforts to draw more people to his constituency, he’s made a few enemies, as well as a surprising friend or two. Adele , one of the world’s biggest recording artists in the world, joined Neil Young , REM and Aerosmith in asking Trump campaign to stop using their music at his rallies. In the past, image conscious candidates would quickly back down when artists would make such requests, but not Trump. His response was pure him…he continued using her material for a few more days, presumably turning up the volume while giving them a one fingered salute.

Not all of the artists who’ve made the music Trump’s been using are upset, mind you. While Twisted Sister lead singer Dee Snider has said he doesn’t necessarily like his policies, he does enjoy Trump’s confrontational style, and has no problem with his band’s song “We’re Not Gonna Take It” to fire up the crowd.

Endorsements

While some current candidates are getting blasted by bands for misappropriating songs, one candidate is experiencing an unprecedented wave of vocal endorsements from the music community: Democrat Bernie Sanders . Sanders’ message of “Democratic Socialism” has struck a deep chord among a wide variety of performers, from stand up comedians to bands from every genre. In an open letter endorsing Sanders’ candidacy over seventy different artists praised the candidate and openly called on their fans to strongly consider making him our next president. It’s a testament to the across socio-political lines appeal of Sanders message that members of Phish , the Red Hot Chili Peppers , Meshell Ndegeocello and Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros all agree on who should be our next president . Maybe they’re just supporting him because he’s one of their own.

Here’s Sanders joining Vampire Weekend onstage in Iowa to sing Woody Guthrie ‘s “This Land Is Your Land.”

The other Democrat in the race, Hillary Clinton has also grabbed some star power musical endorsements, though. Names like Barry Manilow , Madonna and Barbara Streisand may look odd next to Kanye West , Beyoncé and Katie Perry, but politics makes for strange bedfellows. With the youth of our nation more politically engaged than ever, it seems like having relatable music tastes is something of a priority for most candidates.

The Republican side of the campaign quite out of touch with the voters when it comes to music. Iowa caucus winner Ted Cruz can’t even name a band he likes , Probably because he says he stopped listening to new music after 9/11. Narcoleptic neurosurgeon Ben Carson strangely has hyper energetic Kid Rock backing him. Jeb Bush had Toby Keith riding with him until he found himself bucked out of the saddle. On the brighter side, long shot candidate Governor John Kasich has vowed to reunite the members of Pink Floyd for a few songs !

All of these efforts by artists to speak their minds politically is powerful force. Their millions of fans can be shown just how powerful their vote can be. If musicians and their work can use their influence to bring more people into the political process then we all benefit. It’s important that the voice of ALL the people be heard. I mean…what’s the worst that could happen…

Musicians Running For Office

…CRAP! Lucky for America, musicians have a terrible track record in getting themselves elected to a public office. In Kanye’s case, he’s given debate opponents so much ammo from his Twitter account alone that any potential run is doomed from the start. For every instance of a rocker turned candidate winning, like Sonny Bono in his bids to become Mayor of Palm Springs, California and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, there’s dozens of other, less successful examples.

2 Live Crew ‘s misogynist front man Luther Campbell ran for Mayor of Miami. Voters seemed to be more worried about his inflammatory music than his promise to clean up the schools and housing projects. Former Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic ran for the clerk’s office of Wahkiakum County of Washington State as a member of an imaginary political party. He later claimed it was a stunt to draw awareness to voting irregularities, but after his famous “Catch a bass with his face” move on MTV Video Music Awards , who really knows with him.

For all those large scale failures, when a musician seeks a relatively smaller office, they seem to have far better luck. Martha Reeves ditched the Vandellas and stopped “Dancing In The Streets” long enough to serve on the City Council of the Motor City, Detroit, Michigan. And Jerry Butler , soul singer and inductee to the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame is Cook County Illinois’ longest serving commissioner, chairing and sitting on dozens of vital committees since his election in 1985. It seems that in the few instances of a musician managing to gain the office they sought resulted in a diligent urge to serve the public good.

Candidates in other nations seemed to have faced the same kind of luck as their stateside counter parts. Nigeria’s Afrobeat legend and human rights activist Fela Kuti attempted to run for president of his nation in 1979, but found any attempts at a viable candidacy blocked by angry power brokers and establishment hard liners angered over his many criticisms of their practices. Once he finally managed to extinguish his bed, Midnight Oil lead singer Peter Garrett won himself a seat in Australia’s house of Representatives, serving there to this day, working for aboriginal rights.

There’s a lot of time between now and November’s big election, and we’re sure to see plenty more controversial statements and endless sound bites from candidates while a carefully chosen classic rock or soul song plays in the background. Remember to look beyond the surface of the candidates and their celebrity endorsements and examine their actual message. Whatever happens on the way to the election, be sure to REGISTER ONLINE HERE .

The influence of music on politics: Can punk, folk, or rap change the world?

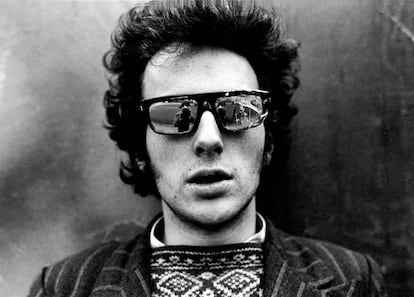

An essay on the sociopolitical themes in the lyrics written by joe strummer, lead singer of the clash, has inspired the debate about the impact popular songs have on an individual’s ideological views.

Whatever the medium, the outcome is the same. Picture it, you are in high school and a friend makes you a mixtape on cassette: what you hear on it makes you see the world in a different way. You have had your eyes opened to this or that injustice, this or that act of resistance, and you experience the music with an emotion you have never had before. The world is wrong, we can fix it, we must try. Your political worldview will never be the same, and that musical discovery may decide your opinions (and your vote) throughout your life. That is the power of music to influence the formation of people’s ideological identity. It is not to be sniffed at.

Joe Strummer (1952-2002), frontman of The Clash , collaborated in the politicization of the punk movement — so nihilistic in its outlook — and his commitment was reflected in the lyrics of all his musical projects, as analyzed in the recent essay The Punk Rock Politics of Joe Strummer: Radicalism, Resistance and Rebellion , by Gregor Gall. Anti-fascism, anti-racism, anti-imperialism, criticism of inequality, and defending the oppressed were some of the issues that the British artist addressed in his verses, some of which have not only gone down in rock and roll history but have also deeply touched the conscience of their fans. He called it rebel rock.

Can music change the world? “When the question is asked in a blunt manner, it is almost suggested music — as a non-human force external to humankind — has the potential to change humans on the scale of humanity itself,” Gall writes. If one asks, in a more nuanced way, if music can simply contribute to sociopolitical change, the answer is that music “may help to change the way people look at the world, that is, their world views and perspectives, rather than the world itself. Thus music can help to inform, potentially changing the way people think and act in a subjective manner,” adds the author.

“All we want to achieve is an atmosphere where things can happen,” said Joe Strummer in an interview with Melody Maker in 1978. Although punk might be considered the quintessential combative style, it is not the only distinguished seed of that “atmosphere.” The folk music of Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and Billy Bragg had a strong political component that predicted times of change (and, by the way, inspired Strummer). As did hip hop, especially in its beginnings (not so much now, having become the global and commercial genre of our time). Back then, Chuck D, a member of Public Enemy, said that rap was “the CNN of the neighborhoods” and he expressed his views ruthlessly and eloquently against police power and abuses. The reggae of Bob Marley , which called for unity against colonialism and oppression, also played its part in creating the atmosphere. The political sneaks in here and there, from classic rock, as in certain sections of Bruce Springsteen, to techno, as in the case of the seminal Underground Resistance collective, passing through Mexican corridos or mestizaje.

“Punk rock, hip hop, and reggae have a playful-expressive side and a political-activist side. There are young people for whom the music’s impact stays in the first category and others who move towards the second. We could say that music is a necessary condition, but it is not enough,” explains Carles Feixa, professor of Social Anthropology at the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF). Although music can encourage politicization, for it to develop and be sustained, other instances must intervene: social movements, grassroots political agents, or times of protest. Furthermore, “singing and dancing have always been a central form of expression in social movements,” adds Feixa, from the classic labor movement, to alter-globalization, and #MeToo through feminism and environmentalism. “Given that youth is the period where musical taste is formed, and young people are the largest consumers of music, this becomes a means of ideological diffusion and, therefore, of politicization,” says the anthropologist.

Affective transformation

“Music is the artistic form that has the most transformative impulse on an emotional level. So it contains a very marked political element. Every work of art is actually a social behavior and, as such, aims to generate a community around it,” says philosopher Alberto Santamaría. Joe Strummer and others, according to Santamaría, were discovering this vector. He also refers to Paco Ibáñez, for example, “laying the political power of the poets of the Golden Age before us. It is clear that in the eighties, with the greater dissemination of music, politics occupied other places within that music.”

According to Gall’s data, a quarter of Joe Strummer ’s followers who were interviewed consider his influence on their political positions as “deep and ongoing.” For others among his followers, the music was always more important than the politics. Despite everything, the essayist concludes that Strummer has been the most important left-wing politicized musician in Western culture since the mid-1970s.

In Spain, music has also had a notable influence on political issues. For example, during the eighties the nationalist left capitalized on the so-called Basque Radikal Rock (RRV) with initiatives such as the Martxa eta borroka (March and fight) tour. While the Movida madrileña (countercultural movement that took place during the transition to democracy) was dedicated to hedonistic dissipation, some bands like Kortatu or Negu Gorriak (both fronted by Fermín Muguruza, who was greatly inspired by Joe Strummer) defended Basque nationalism. Others, with a more punk style, like Eskorbuto or La Polla Records, preferred to ignore nationalism and spitting on flags, despite being frequently lumped in with the nationalists.

The Basque Popular Party had a brief similar initiative in the presentation of its so-called Pop Politics , in which the group Pignoise collaborated, with former soccer player Álvaro Benito at the helm. The neo-Nazi extreme right has also used music, in far-right versions of punk or the Oi! subgenre (a derivation of punk associated with the skinhead subculture), as in the case of the Rock Against Communism (RAC) subgenre, and international bands such as Skrewdriver or Spanish bands such as Estirpe Imperial and Klan.

Songs are better than arguments

The lyrics of Evaristo Premos, a living legend in Spanish punk, frontman with La Polla Records, planted the seeds of social criticism and anarchy in the heads of several generations, with subtle irony and a lot of audacity. The band was praised by thinkers like Santiago Alba Rico or Carlos Fernández Liria.

“We were amazed because this group’s lyrics were politically much more in tune than all the speeches and programs of the left-wing political parties. Their albums were a true course in citizenship education, an impressive teaching model to think about the condition of citizenship under capitalism. There was not one slip, not a single mistake, the lyrics were perfect,” explains today Fernández Liria, professor of Philosophy at the Complutense University of Madrid. For these reasons they came to affirm, through creating a certain amount of scandal, that those punks from Salvatierra, (Spain) were the only ones who were doing authentic philosophy in Spain in the eighties.

In addition to the messages that the lyrics may include, the music also offers a space for coming together, sociability, identification, and solidarity with like-minded individuals. It has been common for young people to build their social environment in the form of gangs or urban tribes, where music has always represented a central element that, in addition to providing an emotional outlet, also provides ideological expression. And beyond these spaces, politics can fit in other ways.

“After [spending all day in] a shitty job, when someone stops and listens to Bach or plays the tambourine or plugs in their guitar in a garage with friends, that act is in itself political,” observes Santamaría. The fact of not aspiring to excellence in the performance of music, the use of the famous three chords, the escape from commercialism, can be taken as a political attitude. “To play badly, at the wrong time, without knowing it, is another form of politics,” says the essayist. And so is the way music is produced, such as in militant, self-managed, independent record companies. A canonical case is that of the American record label Dischord Records, run by Ian MacKaye, a member of classic hardcore bands such as Minor Threat and Fugazi.

Music continues to be a direct route to the heart to convey political passions. “Music is, as I say, the vehicle that allows a people to think. Without songs, politics would be something entirely foreign to the people, an occupation of technocrats and professionals,” concludes Fernández Liria.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

More information

The ordeal and salvation of Tim Armstrong, ‘the Bob Dylan of punk’ went into rehab to form Rancid: ‘It was like a Rocky movie’

NOFX singer Fat Mike: ‘Punk is played by cool people, not jerks’

Archived in.

- Francés online

- Inglés online

- Italiano online

- Alemán online

- Crucigramas & Juegos

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Contentious Politics and Political Violence

- Governance/Political Change

- Groups and Identities

- History and Politics

- International Political Economy

- Policy, Administration, and Bureaucracy

- Political Anthropology

- Political Behavior

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Philosophy

- Political Psychology

- Political Sociology

- Political Values, Beliefs, and Ideologies

- Politics, Law, Judiciary

- Post Modern/Critical Politics

- Public Opinion

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- World Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Protest and music.

- Sumangala Damodaran Sumangala Damodaran School of Develompent Studies, Ambedkar University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.81

- Published online: 05 August 2016

The relationship between music and politics and specifically that between music and protest has been relatively under-researched in the social sciences in a systematic manner, even if actual experiences of music being used to express protest have been innumerable. Further, the conceptual analysis that has been thrown up from the limited work that is available focuses mostly on Euro-American experiences with protest music. However, in societies where most music is not written down or notated formally, the discussions on the distinct role that music can play as an art form, as a vehicle through which questions of artistic representation can be addressed, and the specific questions that are addressed and responded to when music is used for political purposes, have been reflected in the music itself, and not always in formal debates. It is only in using the music itself as text and a whole range of information around its creation—often, largely anecdotal and highly context dependent—that such music can be understood. Doing so across a whole range of non-Western experiences brings out the role of music in societal change quite distinctly from the Euro-American cases. Discussions are presented about the informed perceptions about what protest music is and should be across varied, yet specific experiences. It is based on the literature that has come out of the Euro-American world as well as from parts that experienced European colonialism and made the transition to post-colonial contexts in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

- protest music

- popular music

- socialist realism

- music and politics

- representation in music

- music and identity

Despite the recognition of the social importance of music, and that social structures and developments can be be reflected in varied ways in musical structures, music has not been given a fair hearing in the social sciences. If little systematic investigation into the relation of music to culture or society as a whole has been made, even less effort has been expended on understanding the relationship between music and politics. Music has represented a mode of expression for human beings’ interaction with their surroundings, making it a spontaneous medium for expressing their discontent with it as well. This discontent has, in varied historical and geographical contexts, been expressed through words, without words, through appraisal, evaluation, and often rejection of certain canonical forms, and through creation of new forms. Further, structures of authority have used music as a medium or mode for transmitting political information and values, mobilizing the population, evoking and sustaining pride and identity, and legitimizing patterns of authority. Despite there being a long history of the connection between music and politics, in the role of music as a medium or an instrument of political communication, in critiquing existing social contexts and norms or in expressing protest against those norms, the corpus of work on music and politics has been scant.

It is necessary to make a qualification here. This point, about the corpus of work on music and politics not being substantial, is being made for politics and protest as manifest through collective political movements and the music of protest that arises out of such political mobilizations. Political theory and political philosophy have engaged with the politics of sound and auditory regimes in capitalism, as well as the politics of the emergence of the “visual” against the “auditory” as the dominant sensorial register that acquires prominence, and through which power gets established and played out in society, particularly under capitalism (Attali, 1977 ; Bull & Back, 2003 ; Siisiainen, 2012 ). French theory, through the work of thinkers such as Ranciere ( 2006 ) and Nancy ( 2007 ), to name two, has been concerned with the relationship of music to society, the place of listening with philosophies and cultures of listening, and the place of the sonorous in being and experience. This essay is concerned specifically with protest music arising from politically challenging moments and movements, and the analysis is based on the processes of music making for such purposes.

What is protest music? Within the larger genre of political music, protest music or the music of resistance is a distinct category, encompassing the use of music in politics and as politics. Every period of social upheaval gives birth to songs of discontent. Some songs are crafted specifically as rallying cries to garner support for a cause or to broadcast a grievance, whereas others express or describe conditions in society that give rise to the discontent. The expressions can be based on the individual, can be part of collectives or musical communities, or part of organized political movements. Each period also produces people who, apart from bringing in their everyday experiences and talents into music making, elucidate clearly the reasons why they produce or reject music of particular types. For artists, often, political discourse and the momentous nature of political upheaval become a medium for articulating what might be primarily aesthetic positions as political ones, and this shapes the nature of protest music that is produced.

Much of the vibrant history, as well as diversity of the genre of protest music, is unknown today, including among practitioners or activists who compose and perform protest songs. This neglect has resulted in stereotypes, of protest music having typically standardized structures—for example, sounding agitational and mobilizational, conveying political messages stridently, through lyrics, tunes, and tempo, mostly sung by a collective, and for this reason perhaps not being good enough music “on its own terms.” As a result, the genre of protest music is associated very often with stereotypical forms and styles of rendering, very often encompassing a limited range of styles or types of lyrics. This stereotype has often resulted in, on the one hand, activist musicians, as well as political formations not considering songs as protest songs unless they conformed to the standardized stereotype with respect to form, and content and non-activist musicians, on the other hand, who dismissed protest music as “mere sloganeering.”

This is an important argument that comes from the relative neglect in the study of the music-politics relationship that has been noted above. Apart from the stereotyping of the protest song, the low levels of attention and, in fact, denigration have been seen in the case of popular music in general. This is an aspect of music scholarship that is highlighted by scholars in the field of popular music studies (Frith, 2007 ; Middleton, 1990 ), who note that categories such as “high” and “low” music are continuously employed to judge whether particular kinds of music can even be categorized seriously or not. Largely coming from the European art music tradition from the early part of the 19th century, but also echoed in countries with strong classical music traditions in South Asia, the embeddedness of music in social processes is consciously denied because such embeddedness is seen to distort the tonal qualities of “good” music and interfere with the ability of music to appeal to “higher” human sensibilities. An understanding such as this reflects an ideology of “superior” listening, associated with the ability to undertake a formalistic and cognitive analysis of musical work, which makes music structurally autonomous of social processes. From dominant western musicological frameworks, therefore, the tendency to associate structured and superior listening with autonomy of musical processes from history or society, is reflected in the need to attribute the labels of “high” and “low” to different kinds of music. In fact, even a scholar like Adorno, who argued that all music should be viewed as a distinct field of activity that can only be understood within larger social processes, uses a framework rooted in the discourse of “high culture” to critique popular music (Bennett, Frith, Grossberg, Shepherd, & Turner, 2005 , p. 2; Middleton, 1990 , pp. 34–62). Many forms of popular music, such as jazz, rock, rap, and so on, which have contained within their history and practice strong elements of protest, have been dismissed as inferior music and often dangerous, using ostensibly objective criteria of structure, style, skills, and techniques.

In turn, the forms of protest music have been determined as responses to such critiques and as a conscious attempt to challenge the structures of the canons. In the words of musicologist Chris Ballantine, “The precise nature of 1960s rock music is explicable only in relation to the protest and possibilities for social change that were the lived experience of young people during that decade; the foreclosing of these possibilities and the shrinking of the horizons of change that characterize the 1970s characterize the altered rock music of the 1970s, on the one hand the total sellout of disco music, on the other the brittle and authentic criticism of the repressive social order so well articulated by punk rock” (Ballantine, 1984 , p. 5).

Critical musical scholarship has emerged, particularly in the field of Popular Music Studies that locates the emergence of structured listening and autonomous art in the particular historical period from the 19th century onwards (Middleton, 1990 ) and as constituting an ideological position “because the bourgeoisie then needed to hold such views” (Ballantine, 1984 , p. 6). One of the reasons for the neglect of studying the relationship between music and politics, or specifically protest, arises from the nature of music scholarship that has originated from the West, which in turn is attributable to particular historical factors governing the development of Western classical music.

A perusal of the actual history and experience of protest music shows it as being a highly varied and historically evolved kind of music, and the stereotypical protest song as being a particular type within the larger genre. It becomes necessary and possible, given the wide range and variety that exists, to argue for the legitimacy of protest music as meriting analysis on its own terms, as music.

In practice, protest through music has seen, historically, the adoption of extremely diverse forms across cultures; the actual range and depth of this category of music is extensive, because it is difficult to arrive at a simple set of principles that constitute the category of protest music. The work that we know of, even if it is remarkably scant in comparison to the actual material that exists, has two characteristics: one, the conceptual analysis has been based on Euro-American experiences with protest genres, both as part of and outside of formal political movements. Two, the focus of scholarly work has, to a large extent, been on individual genres and their use in politics. For example, Bennett et al. ( 2005 ), which presents a critique of the method of using “high” and “low” categories to understand any music, is a detailed collection of essays on the rock tradition in Europe and North America. Barker, who reviews conceptual issues that have arisen in analysis of protest music, bases his own research on the American counterculture, and Drott ( 2011 ) describes ways in which rock, jazz, and contemporary music all responded to the events of 1968 in France, often in contradictory ways.

However, in societies where most music is not written down or notated formally, the discussions on the distinct role that music can play as an art form, as a vehicle through which questions of artistic representation can be addressed, and the specific questions that are addressed and responded to in using music for political purposes, have been reflected in the music itself and not always in formal debates. It is only in using the music itself as text, and a whole range of information around its creation, often, largely anecdotal and highly context-dependent, that such music can be understood. Doing so across a whole range of non-Western experiences brings out the role of music in societal change quite distinctly from the Euro-American cases. For example, Aadnani ( 2006 ) is a survey of protest music and poetry in North Africa in the contemporary period, discussed in the context of the Rai musical tradition. There are numerous studies of the Nueva Cancion movement in Latin America (Elliott, 2011 ; Gasparotto, 2011 , to cite two), of rebetiko (Tragaki, 2007 is an important example), of the Anti-Apartheid movement (Ballantine, 1993 ; Olwage, 2008 ; Schumann, 2008 ), and so on. While there are numerous case studies of such experiences, again, the conceptual analysis that takes it beyond the limits of the case that is being studied is limited.

While the insights from all such work are valuable in locating the emergence of or engagement with specific genres of music in expressing political positions or locating their politics historically, a conceptual framework that encompasses diversity of experience and yet culls out basic principles around which the relationship between music and protest can be understood is yet to be worked out.

This article reviews some of the discussions that have informed perceptions about what protest music is and should be across varied, yet specific experiences. It is based on the literature that has come out of the Euro-American world, as well as from parts that experienced European colonialism and made the transition to post-colonial contexts in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Through these examples, we attempt to raise some of the broad concerns of protest music from different parts of the world and across different periods in recent history.

The category of protest music, as a consciously conceived musical as well as a political genre, may have come into existence with the combination of political circumstances that characterized the early part of the 20th century. Anti-colonial struggles, movements for civil rights, socialist revolutions, peasant and trade union movements accelerated from the second decade of the 20th century. Nationalist movements in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, the pre- and post-revolution political movements in China and Russia, the Greek Resistance, May 1968 , the Civil Rights Movement, Popular Frontism, the Anti-Apartheid Movement, the Nueva Cancion Movement in Latin America are some examples of massive political upheavals and movements that created repertoires of protest music over the course of the 20th century. In most of these cases, protest song movements saw the creation of organizations that would undertake the task of creating the repertoires and organizing musical activity. Further, whether or not they were part of organized movements, protest music genres have been numerous, making a detailed listing difficult.

Function and Form in Protest Music

In the broadest sense, protest music expresses discontent with perceived problems in society, covering a wide variety of issues and concerns ranging from personal and interpersonal to local and global matters.

If music has been used to convey protest, in what ways does it do so? Several sets of issues have been important in the creation of protest music. First, how can music be political, or what constitutes political expression in music? Is it related to its political function or to its own structure, mode of expression, and rules? Can music be political without text? Can music be political without relying on the explicit meaning of words?

In one of the relatively early and few works that attempt to define protest music, Serge Denisoff ( 1968 ) categorizes protest songs from a teleological point of view, presenting a functional model of protest song. The functions of political protest, whether in individualistic terms or as part of political movements, are what become important in judging whether a song or a form of music is political or not. Protest songs, by this classification, are defined as such by the ends they seek to achieve, “whether in highlighting social ills, recommending solutions to problems, serving as a form of political propaganda, recruiting members for a cause, or contributing toward feelings of solidarity.” While for Denisoff himself, it is song lyrics that ultimately achieve these aims, the actual variety seen in the category of “functional” protest songs takes it far beyond song lyrics.

In practice, the functions that are served by protest music range from being able to rouse and hold the attention of large gatherings, being part of campaigns, and telling stories of injustice to reproducing music of ordinary people and depicting their lives through lyrics as well as form. Stated more elaborately, “The music of protest has been used to transform consciousness, stir emotions, impose ideology, arouse courage, mobilize forces, ameliorate anger, incriminate power, organize workers, provoke outrage, inspire reflection, express fear, …” (Edmondson, 2013 , p. 902). Thus, from singing anthems that propagate a cause or songs that exhort people into action, to those that merely lyrically describe ordinary peoples’ lives, various functions of protest music are fulfilled. Further, the functions depend upon whether the music is being produced and performed by individuals, musical groups/collectives/communities, or by organized movements.

Denisoff, in focusing on the political functions being served by protest music, makes a distinction between magnetic and rhetorical protest songs, with the former referring to songs with simple melodies and lyrics that can easily catch the attention of listeners and convey a direct political message, and the latter describing songs that are less direct, point out to some specific problem, and appeal to the audience in emotional terms (Denisoff, 1983 ). Pointing out that the American protest song movement has seen a relative decline in magnetic songs and an increase in the rhetorical kind, he suggests that this reflects a decline in class-consciousness, political organization in the politics of protest over time, and an accompanying ineffectiveness, in large mobilizational terms, of protest music.

However, despite the variety in protest music that plays an explicit political function, critics like Barker have argued that the functional approach results in “an excessive focus on song text, a reductive assertion of a unidirectional causal relationship between intended political message and political function, a subordination of the form of protest music to its function, and a prioritization of abstract categories over context”.

Even within a functional understanding of protest music, how has music without text been understood? Hanns Eisler, the German composer who also composed music for many of Bertolt Brecht’s plays, developed what might be considered a hardline view of what should come under the category of “workers’ music” in the 1920s and the 1930s. He rejected purely orchestral music as not being suitable for a worker’s music repertoire and advocated the creation of simple, direct songs. In writing about the importance and role of a workers’ music movement, he argued that “… all music forms and techniques must be developed to suit the express purpose, that is the class struggle. In practice, that will not result in what the bourgeoisie calls style, … in the workers’ music movement we do not aspire to style but to new methods of musical technique, which will make it possible to use music in the class struggle better and more intensively” (Grabs, 1978 , p. 68). Music without words, or orchestral works alone, according to him would be “not right” for a proletarian audience because “such symphonic music … is not accessible to workers either materially or ideologically, … the problem of symphonic orchestral music of a proletarian character is just as insoluble as the attempt to change a dress suit into overalls by painting it red” (Grabs, 1978 , p. 68). What would be appropriate would be programs that consist of fighting songs and orchestral music with choruses, practiced with the public, a “new revolutionary style of music (which) enables novel and original compositions to be so contrived that they can also be executed by untrained amateurs” (Grabs, 1978 , p. 220). The Socialist Realist tradition from the 1930s, which originated in the Soviet Union but was influential in left cultural movements in different parts of the world, emphasized a greater role for the texted genre as against purely symphonic music in representing revolutionary consciousness. Creating anthem-like music with lyrics that were uplifting, heroic, and optimistic, in often grandiose representations of the “new socialist man,” were considered part of the creation of revolutionary music.

Inscribed into such a view of protest music are its exhortatory as well as its didactic roles, recognizable by the qualities of simplicity, accessibility and focus on lyrics. The didactic and explanatory elements of music for the revolutionary cause also came from Brecht’s theatre, which developed these ideas as aesthetic devices in theatre. This meant an eschewal of “lyricism,” in progressive theatre music, of expression for its own sake, in favor of “gestic” music, or music that can explain the social context of the issues taken up by such theatre. Often, it also meant a denouncement of formalism, defined officially as “the separation of form from content” in music, which took many forms. An interpretation of a position such as this in East Germany, in the 1950s, for example, resulted in a critique of atonal music as “not comprehensible to the masses” (Frackman & Powell, 2015 ), along with an understanding that performers should not get too absorbed in their own performances to communicate effectively with their audiences. Underlying these positions was a didactic element for the “masses,” which was often accompanied by arguments for simplicity and accessibility, as in the case of Denisoff’s magnetic protest song. In fact, it is the magnetic protest song that perhaps represents the “stereotypical” protest song that has been referred to earlier, with effectiveness being judged by the immediate inspirational and rousing effect it has on audiences, allowing it to be an effective tool for political mobilization.

However, the functional argument apart, the debate has gone beyond encompassing the form that protest music should take, as is apparent.

History, Context, and Form

This brings up a question that has been important in the history of protest music: what are the kinds of music that need to be represented in a radical political movement or to express protest? Here political questions, as well as issues of aesthetic representation, become important, including the question of function raised earlier and the preceding section indicated. The role of form in representation, in being an intrinsic component of what protest music is but also being important in what protest music does , who to represent, and how to represent politically, has generated some of the most important debates in the history of protest music, involving the relevance of history and context that go beyond the immediate political questions being raised. Issues of nation, nationalism, tradition and that of modes of representation such as modernism, formalism, and realism have been important aspects where history and context have been seen to influence the creation of protest music repertoires.

Over the entire 20th century and into the present, expansive and varied notions of “the people” or the “popular classes,” as Gramsci was to characterize those who emerged as the objects of subjugation, were employed in the creation of protest music. Music, like other art forms, came to be employed in establishing the “ordinary person” as a legitimate subject of history and art, resulting in a varied musical iconography of “the people.” In music, as in the other art forms, realism, interpreted in various ways, emerged as the mode of representation.

In the first half of the 20th century, the ideologies that constituted globally the left and democratic politics of the time, notably nationalism, anti-fascism, and an emancipatory socialism, were being explored and expressed musically in different ways within and across political movements, pointing to interesting similarities and contrasts. Recurring questions that were being asked were: should people’s music be spontaneous and faithfully represented, or consciously crafted out of whatever forms are considered appropriate, or through newer forms? When spontaneous music emerges that reflects the lives of ordinary people, how should it be assessed?

With anti-colonial struggles gathering momentum in countries like India, for example, a crucial question that came up was the degree of engagement with “tradition.” Within a political understanding that colonialism had destroyed and marginalized the cultures of the people, one of the tasks of musical representation, it was felt, was to “bring back” traditional music on behalf of the people. A significant part of the protest music repertoire in India in the 1930s and 1940s, under the aegis of organizations such as the Indian People’s Theatre Association set up in 1943 , consisted of music that was excavated, retrieved from, and played back to “the people” (Damodaran, 2008 ). This creation of a “documentary aesthetic” was a feature of China in the buildup to the revolution from the 1920s as well, and this led Chinese musician Guo Moro to give a call to activist musicians to “be a phonograph” (Jones, 2001 , p. 28). This aesthetic of “phonographic realism” was an important component of leftwing mass music produced in China in the 1930s, which “recorded” the struggles and aspirations of the proletariat and subsequently played them back to society as a means of social mobilization. A large part of such repertoires in different contexts consisted of folk music, involving folkloric revivals; and underpinning their creations were particular notions of nation, nationalism, and “the people.”

In the second half of the 20th century, the Nueva Canción or New Song Movement involving thousands of musicians throughout Latin America, produced a huge corpus of music. One of the frontrunners of the movement in Chile, Violetta Parra, collected hundreds of folkloric musical pieces from different region of Chile and reproduced and introduced them in urban areas of the country as part of the celebration of indigenous music and traditions in affirming socialist values.

A version of the need to reproduce the conditions of life of ordinary people, in their own languages and using traditionally existing modes of expression, was seen in the music that came out of the Anti-Apartheid Movement in South Africa. While the early influences on South African popular music were strongly from the West, by the mid‐1930s, African elements were consciously brought into the music to make a political statement. As in Latin America, a new musical consciousness emerged that stressed on everyday life and on indigenous forms that were embedded in the music being created. In the words of Miriam Makeba, one of the most significant singers of the protest movement, “People say I sing politics, but what I sing is not politics, it is the truth” (Ewens, 1991 , p. 192).

The engagement with tradition in colonial countries encompassed not only indigenous folk music but classical traditions as well, with serious debates on whether or not protest music was to engage with classical traditions, which might have emerged as elitist and hence not representative of “the people.” In this, protest musicians, as part of anti-colonial struggles, had to respond to and contend with conceptualizations of nationalism, where holding up classical traditions became important in representing the people in a nationalist sense, but then having to simultaneously depict exploitative social and class structures through alternative nationalist symbols, like the folk music mentioned earlier. The Indian example is interesting to illustrate this point. As part of the organization called the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), mentioned earlier, which was formed to consciously articulate protest through cultural means, the classical musician Ravi Shankar and many others produced protest music that was strongly based in the Indian classical music tradition; they also took the position that music intended for a political cause should not compromise on complexity and rigor in its effort to be accessible to large numbers of people (Damodaran, 2008 ). The accessibility needed to be ensured, according to such a view, not by a forced simplicity of form, but by depicting political situations through the music and democratizing performance practices and venues of all music, including that which is inspired by the classical tradition.

In countries like the United States, the relationship of the protest musicians with the classical music tradition in the first half of the 20th century was somewhat different from what has been described above. Professional composers such as Elie Siegmeister, Marc Blitzstein, Aaron Copland, and others who were beginning to question and break out of what were perceived as the bourgeois and elitist trappings of classical music in the European, particularly French tradition, as it existed in the United States at the time, also became part of the protest music tradition. Their engagement with classical music involved imbuing it with “modernist” idioms, symbols of industrialism and class exploitation, and creating socially responsive music (Oja, 1988 ).

By the second half of the 20th century, disappointments with the nationalist project in post-colonial contexts led to critiques that identified people on the basis of identity and difference. Protest music was, in ways different from before, perhaps, asking questions about authenticity in representation and hence questioning overarching expressions of nationhood. For example, the scholar Josh Kun, who analyzes aspects of the creation of an “audiotopia” in the United States in the 20th century, argues that with Langton Hughes’ 1925 poem “I, Too, Sing America,” and his essay titled “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” he gave a call for a “re-hearing and a re-singing of American culture through black ears and black sounds … Let the blare of Negro jazz bands and the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing blues penetrate the ears of the colored near-intellectuals until they listen and perhaps understand” (Kun, 1995 , p. 144). Even if the marking of such differences and the absorption of sounds of difference were understood as essential for protest music in different contexts, it was the denial of rights and the conscious attempts to obliterate difference, in societies like the United States and in ex-colonial countries in South Asia, that led to questions about authenticity in representation. A whole tradition of music from the Dalit movement in India, exemplified by the work of the singer Sambhaji Bhagat, is an example where such assertions of difference and the associated foregrounding of authenticity of representation of “real people” has been seen. Bhagat, in his performances is known to make clear distinctions between what is “heard” by those who belong to upper caste groups and Dalits, those who belong to the lowermost castes in the hierarchy in India.

Thus, the understanding that musical forms are important means of identity creation, and that identities get represented and affirmed by music, became integral to the creation of protest music, with form acquiring priority in the assertion of such identity. So while the function, in this case, of representing difference, is paramount, the nuances of the music itself and what is “heard” by audiences become important elements in understanding and decoding protest music.

Eyerman and Jamison ( 1998 ) make an important point about “tradition” in their study of the role of music in social movements in the 20th century, that “Music, and song, we suggest, can maintain a movement even when it no longer has a visible presence in the form of organizations, leaders and demonstrations, and can be a vital force in preparing the emergence of a new movement. Here the role and place of music needs to be interpreted through a broader framework, in which tradition and ritual are understood as processes of identity and identification, as encoded and embodied forms of collective meaning and memory” (Eyerman & Jamison, 1998 , pp. 43–44).

Another dimension of the relationship between music, politics, and identity comes across when identities of particular groups are asserted through the difference between them and the dominant groups in their own societies through the adoption of genres of “others” who might be nationally, ethnically, or socially removed from them. For example, Eric Drott, in his study of the musical trends that arose in the wake of the May 1968 uprising in France notes that “… identification with Anglo-American youth culture opened a space where their lived experience of difference could take shape … Such was the case with free jazz by a younger generation of enthusiasts in the years around 1968 ; in the short-lived infatuation with contemporary classical music during the same period; and in the appropriation of ‘The Internationale’ by youthful protesters in May 1968 ” (Drott, 2011 , p. 271).

Thus, while the structure of particular kinds of protest music (through lyrics or form) might represent particular identities of groups that wish to assert their own identities, it has not always been through identification with own origins, necessarily. The creation of newer political identities, for example, that of the “working class,” have involved musical mixing and borrowing between cultures, apart from projecting music of one’s own cultures. Performing work and labor songs from specific cultural contexts and also from other, sometimes culturally far removed international contexts, has been a typical feature of protest song movements in many countries. The translation into several languages and the popularity of “The Internationale” in different parts of the world is but one example of such identification and solidarity.

Further, identities have not only been asserted through the forms that denote origins but have also been questioned and reconstructed through those very forms. Thus, the aesthetic nuances of the forms themselves might get used to subvert conventional or essentialist understandings of identity, as an “imagined transcendence of difference” (Drott, 2011 , p. 271) or in fact to project new identities.

Musical Structure and Protest

Conceptually, this takes us to a third set of debates around protest music: is the formal structure of music important to consider when we analyze political or protest music? How can music, with or without text, represent dissent through its own grammar? Here, while some debates have been overt and reflected in open disagreements between musicians, often written down, some have been reflected through the kinds of music created.

In the period immediately following the Russian Revolution, the maverick futurist composer Arthur Lourie, who headed Muzo, the music department of Narcompros, the Culture Department of the post-revolution Soviet Union, argued that the spirit of music needed to reflect the ideology of revolutionary chaos because for him, the revolution itself was music. Creating music that symbolized the chaos by its structure, thus, was the essential ingredient of articulating protest (Schwarz, 1972 ). The first couple of decades of music production in the Soviet Union after the revolution are replete with such examples, how the category of revolutionary music was vigorously debated, and how form itself became an important ingredient of understanding revolutionary music.

One of the important debates in the discussions on revolutionary aesthetics, especially from the 1930s, has been around the idea of socialist realism, defined and declared as the appropriate mode of representation in socialist art in the Soviet Union, but also becoming influential in many parts of the world influenced by socialist ideology. The controversies around the interpretation and implementation of the term in actual practice in political movements have been many, and beginning from art practice in the Stalinist period in the Soviet Union under Stalin to various other contexts, including Asia and many parts of Europe, the association of Socialist Realism, with rigid organizational positions and censure of artists who did not conform, has been common. More contemporary research argues that socialist realism was, to begin with, visualized only in terms of how art forms “would reflect the new life of the proletariat, it would be a truthful reflection of the progressive, revolutionary aspirations of the toiling masses building communism” (Swiderski, 1979 , p. 4); hence, it could be reduced to demands for accessibility, tunefulness, stylistic traditionalism, and folk-inspired qualities in music, but it got established as a credo and was subsequently interpreted in more strict organizational terms. In the Soviet Union particularly, the socialist-realist idiom in music was expected to focus on particular forms, such as cantatas and symphonies, and use musical materials from folk melodies (especially of non-Russian nationalities). What is not as apparent is whether the “doctrine” of socialist realism, as understood by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union as well as musicians making music for the Revolution, necessarily denounced experimentation and modernism in music, as is often held. Following from material published from the 1970s onwards, about socialist realism being an outright rejection of modernism, with the two ideas being polar opposites, more recent work on the relationship between modernism and socialist art (Titus, 2006 , drawing from Fay, 1980 ; Schwarz, 1972 ) argues that this was an extreme view, “encouraged by historians who illustrated a split throughout the twenties between the modernists and proletarian factions, with the proletarian factions ‘winning’ in the end” (Titus, 2006 , p. 63).

The pitting of simplicity against modernism, mentioned in the earlier section with regard to the United States, was fundamentally to do with musical grammar, something that went beyond the lyrics or the message and engaged with the structure of the music. While on the one hand, the simplicity or “directness” argument was important and pervasive, hinging on the need to appeal to large numbers of people, avant garde experiments with modernism in music were reflected in the use of atonal sounds depicting industrialism. The latter was a structural recording of protest against the stated oppressiveness of the European classical tradition, by challenging its grammar and rules of composition.

In India, the music of the Kerala People’s Arts Club in the southern Indian province of Kerala, consciously crafted a musical tradition where the tunes and lyrics had a distinct character that attempted to assimilate with as well as break from certain established traditions in the late 1950s. This conscious crafting of the music took place as a result of significant deliberations and debates within the movement about what the music needed to sound like to herald a new era. Specifically, this new crafted repertoire adopted the rendering practice from the North Indian classical music tradition in a cultural context that was in southern India, imbuing tunes with local flavors and combining them with lyrics that were also consciously created to convey an ethos of a “new beginning,” part of a left political movement to overthrow an existing exploitative system of landlordism. Similarly, a harmonic tradition of songwriting and composition, initiated by the musician Salil Chowdhury in the province of Bengal, fundamentally challenged the structures of Indian songwriting, while retaining Indian melodies and modes of rendering, crafting a new kind of protest song from the 1940s, that also became very popular (Damodaran, 2008 ).

The debates around musical grammar across different contexts had to do with the sounds and instruments that were used, the scales and modes of rendering, and the use of voice, the principles of tonality, and the notions of local and foreign elements in musical cultures. Again, the use of history and specific context in repertoires of protest movements have been important in discussions around musical grammar; but the focus extends to what might stretch the boundaries of known traditions in the quest to express dissent or project a new future. Thus, if the allusion to the modern involved challenges to the Western classical tradition through atonality and the sounds of industrialism in Western countries, it had to be in the adoption of Western musical formats and features, such as harmonies in non-Western musical cultures like India or China. If radical representation had to be about “the people,” it had to sometimes be “a phonograph,” or at some other times play an interpretative role, which meant breaking out of the boundaries of existing musical forms. Thus, while politics might mediate what form is employed in different contexts, often form mediates political expression in different and changing ways.

To sum up, the debates around the relationship between music and politics have, in practice, been around questions that straddle the realms of both aesthetics and politics. The combined aesthetic-political considerations have involved issues of representation (who, why, and how to represent political identities) as well as function (what the functions of protest music are). History and social context have influenced both representational and functional aspects, generating the wide variety that has been seen. Thus, different kinds of music, performed or conceptualized in different contexts, have engaged politics in different ways. The functions and meanings of different types of music are employed variously, making the protest music genre complex and highly evolved, historically, as this article has attempted to bring out.

- Aadnani, R. (2006). Beyond Rai: North African protest music and poetry . World Literature Today . Online journal available on The Free Library.

- Attali, J. (1977). Noise: The political economy of music . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ballantine, C. (1984). Music and its social meaning . Johannesburg, South Africa: Ravan Press.

- Ballantine, C. (1993). Marabi nights: Early South African jazz and vaudeville . Johannesburg, South Africa: Ravan Press.

- Bennett, T. , Frith, S. , Grossberg, L. , Shepherd, J. , & Turner, G . (Eds.). (2005). Rock and popular music: Politics, policies, institutions . New York: Routledge.

- Bull, M. , & Back, L. (2003). The auditory culture reader (sensory formations) . New York: Oxford University Press.

- Damodaran, S. (2008). Protest Through Music. Seminar , Issue 588, August.

- Denisoff, S. R. (1968). Protest movements: Class consciousness and the propaganda song. The Sociological Quarterly , 9 (2), 245.

- Denisoff, S. R. (1983). Sing a song of social significance . Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

- Drott, E. (2011). Music and the elusive revolution: Cultural politics and political culture in France, 1968 – 1981 . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Edmonson, J. (2013). Music in American life: An encyclopedia of the songs, styles, stars, and stories that shaped our culture . Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood.

- Elliott, R. (2011). Public consciousness, political conscience and memory in Latin American Nueva Cancion. In D. Clarke & E. Clarke (Eds.), Music and consciousness: Philosophical, psychological and cultural perspectives . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ewens, G. (1991). Africa o‐ye! A celebration of African music . Enfield, U.K.: Guinness.

- Eyerman, R. , & Jamison, A. (1998). Music and social movements: Mobilizing traditions in the twentieth century . Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Fay, L. (1980). Shostakovich versus Volkov: Whose testimony? Russian Review , 3 9(4), 484–493.

- Frackman, K. , & Powell, L . (Ed.). (2015). Classical music in the German Democratic Republic: Production and reception . New York: Camden House.

- Frith, S. (2007). Taking popular music seriously : Selected essays . Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate.

- Gasparotto, M. (2011). Curating la Nueva canción: Capturing the evolution of a genre and movement . RUcore digital archive. Rutgers University Community Repository.

- Grabs, M. (Ed.). (1978). Hanns Eisler: A rebel in music: Selected writings . London: Kahn and Averill.

- Jones, A. (2001). Yellow music: Media culture and colonial modernity in the Chinese jazz age . Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Kun, J. (1995). Audiotopia. Music, race, and America . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Middleton, R. (1990). Studying popular music . Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

- Nancy, J.-L. (2007). Listening ( C. Mandell , Trans.). New York: Fordham University Press.

- Oja, C. (1988). Composer with a conscience: Elie Siegmeister in profile. American Music , 6 (2), 158–180.

- Olwage, G. (2008). Composing apartheid: Music for and against apartheid . Johannesburg, South Africa: Witwatersrand University Press.

- Ranciere, J. (2006). The Politics of Aesthetics—The Distribution of the Sensible . Translated by Gabriel Rockhill . London: Continuum.

- Schumann, A. (2008). The beat that beat apartheid: The role of music in the resistance against apartheid in South Africa. Stichproben. Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien , 14 (8), 17–39.

- Schwarz, B. (1972). Music and musical life in Soviet Russia 1917–1970 . New York: W. W. Norton.

- Siisiainen, L. (2012). Foucault and the politics of hearing . New York: Routledge.

- Swiderski, E. (1979). The Philosophical Foundations of Soviet Aesthetics—Theory and Controversies in the Post-War Years . Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

- Taruskin, R. (2000). Defining Russia musically . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Titus, J. M. (2006). Modernism, socialist realism, and identity in the early film music of Dmitry Shostakovich, 1929–1932 (PhD Diss.). Ohio State University.

- Tragaki, D. (2007). Rebetiko worlds . Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Scholars.

Related Articles

- The 5 Ws of Democracy Protests

- Civil Disobedience and Conscientious Objection

- Protest and Contentious Action

- The Demobilization of Protest Campaigns

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Politics. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 09 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|162.248.224.4]

- 162.248.224.4

Character limit 500 /500

Charles Rosen’s Freedom and the Arts: Essays on Music and Literature

September 3, 2012 by Taylor Davis-Van Atta

The following review originally appeared in Issue 29 of The Quarterly Conversation .

Twentieth-century music has changed our understanding of Mozart and Beethoven. What we now hear was, of course, always there. — Charles Rosen

Freedom and the Arts: Essays on Music and Literature by Charles Rosen (Harvard University Press, May 2012) Reviewed by Taylor Davis-Van Atta

How we interpret art—as individuals and collectively—is influenced by a complex of inherited and learned sensibilities peculiar to our time, and also by prior knowledge one brings to the experience: a book is read against the tapestry of all previously read books; within a piece of music wisps of prior recordings or performances, or even entirely other pieces of music, are heard; meanwhile, innate political, cultural, and aesthetic understandings are altering our perceptions and tastes. All of this input informs and heightens our experience of art, but it can also hinder the pure pleasure of an experience. Even a desire to understand or find meaning in art can itself be a limiting factor—a paradoxical idea when one considers that the main function of art may ultimately be to liberate us from the entrapments of meaning and/or from an antiquated understanding of the world around us. Having inherited modern sensibilities implicit in our time and culture, and limited by an incomplete knowledge of the conditions of past eras out of which some of our most enduring art emerged, we might raise a central question: to what degree are we, as individuals and as a public, able to exercise free will over our own interpretations and appreciation of art?

The critic, historian, music theorist, and virtuosic pianist Charles Rosen has spent the past half century examining this question, and his latest book, Freedom and the Arts: Essays on Music and Literature , a collection of 28 essays written mainly over the past 15 years, is his most expansive analysis to date of the challenges and pleasures of art. It contains his most direct attempts to address the question of free will in artistic interpretation. Endowed with enormous knowledge (what Pierre Boulez calls his “vast culture”), Rosen is a most gifted critic, one who not only explicates and illuminates scores and texts with easy precision but whose reviews and essays stand apart from their subject as pieces of literature in their own right. Rarely of one mind on any subject, except perhaps his preferences for certain recordings and particular fingerings, Rosen in this collection unapologetically contradicts himself and homes in on paradoxes he is unable to reconcile, engaged in a decades-long discussion with the finest artists of the past four centuries—and with his own mind. Above all, he elaborates on several lifelong arguments, making this volume a valuable companion to his major books, as well as a terrific introduction those who have not yet read his work.

As a pianist, Rosen’s performances are studies in technique; his light interpretative approach brings out the emotional heart of the music (rather than putting it in , as a less deft performer might). Likewise, the genius of his criticism lies in his ability to expose through examination of an artist’s technique the nervous system of the literature or music in question, allowing the emotional and intellectual vitality of the piece to come strikingly into light. His reading of Elliot Carter’s cello sonata (in “Happy Birthday, Elliot Carter!”), for instance, is the most perceptive I have read and chased me to my CD collection to experience the piece anew, wanting to test Rosen’s insight:

The cello sonata opens with the piano in strict time, ticking away in moderate tempo with a quiet percussive staccato. The cello, however, exists in a different space-time, with a long, lyrical, and eloquent line, irregular and seemingly improvised, very few of its notes coinciding with the beats of the piano. The opening may be the first example of Carter’s use of the long, expressive, singing arabesque line that was virtually absent in modernist style. . . . No previous work for cello and piano had ever differentiated the two instruments so distinctly, and exploited the sonority of each.

In his essays Rosen moves with ease between intimate examinations of texts—be they scores or poems—and the broader context in which we experience them. Central to all of Rosen’s writing is the question of how we might best appreciate the work in question, and because this is his point of enquiry, one typically needs only a passing familiarity with his subject to be engaged by even his most rigorous examinations. On Mallarmé, Rosen teaches us new ways of reading “the seemingly unreadable poet”: