- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

What was the outcome of the Cuban missile crisis?

Should the united states maintain the embargo against cuba that was inflamed by the cuban missile crisis.

- What was the Cold War?

- How did the Cold War end?

- Why was the Cuban missile crisis such an important event in the Cold War?

Cuban missile crisis

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- HistoryNet - Inside the Cuban Missile Crisis

- PBS LearningMedia - Cuban Missile Crisis | Retro Report

- John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum - Cuban Missile Crisis

- The History Learning Site - Cuban Missile Crisis

- Khan Academy - The Cuban Missile Crisis

- Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs - The Cuban Missile Crisis

- GlobalSecurity.org - Cuban Missile Crisis

- Academia - Cuban Missile Crisis

- Warfare History Network - The Cuban Missile Crisis: On the Brink of Nuclear War

- Alpha History - The Cuban Missile Crisis

- Hoover Institution - The 1962 Sino-Indian War and the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Spartacus Educational - Cuban Missile Crisis

- The National Security Archive - The Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962: The 40th Anniversary

- Cuban missile crisis - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Cuban missile crisis - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

What was the Cuban missile crisis?

The Cuban missile crisis was a major confrontation in 1962 that brought the United States and the Soviet Union close to war over the presence of Soviet nuclear-armed ballistic missiles in Cuba.

When did the Cuban missile crisis take place?

The Cuban missile crisis took place in October 1962.

The Cuban missile crisis marked the climax of an acutely antagonistic period in U.S.-Soviet relations. It played an important part in Nikita Khrushchev ’s fall from power and the Soviet Union’s determination to achieve nuclear parity with the United States. The crisis also marked the closest point that the world had ever come to global nuclear war.

Whether the U.S. should maintain its embargo against Cuba that was inflamed by the Cuban Missile Crisis is hotly debated. Some say Cuba has not met the conditions required to lift it, and the US will look weak for lifting the sanctions. Others say the 50-year policy has failed to achieve its goals, and Cuba does not pose a threat to the United States. For more on the Cuba embargo debate, visit ProCon.org .

Recent News

Cuban missile crisis , (October 1962), major confrontation that brought the United States and the Soviet Union close to war over the presence of Soviet nuclear-armed missiles in Cuba .

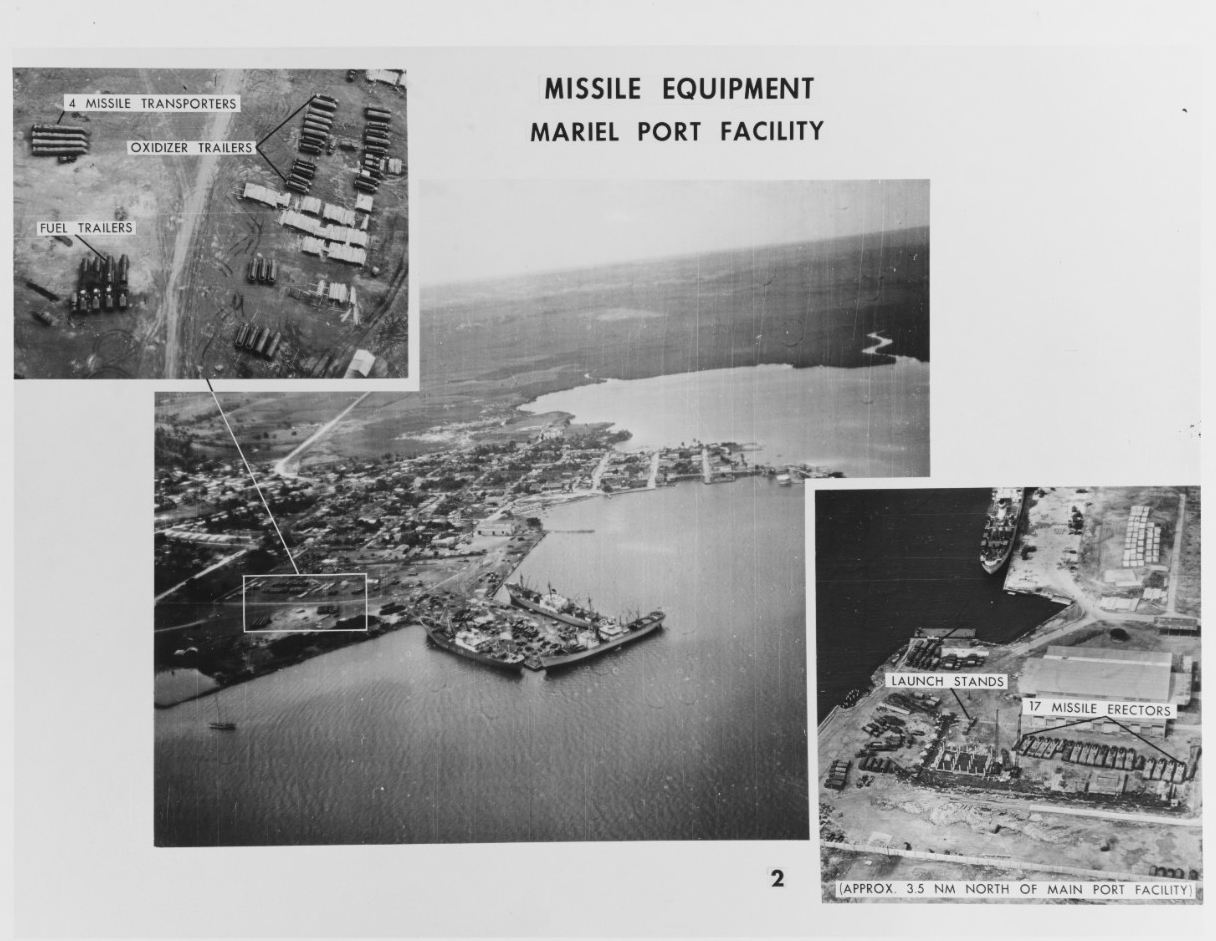

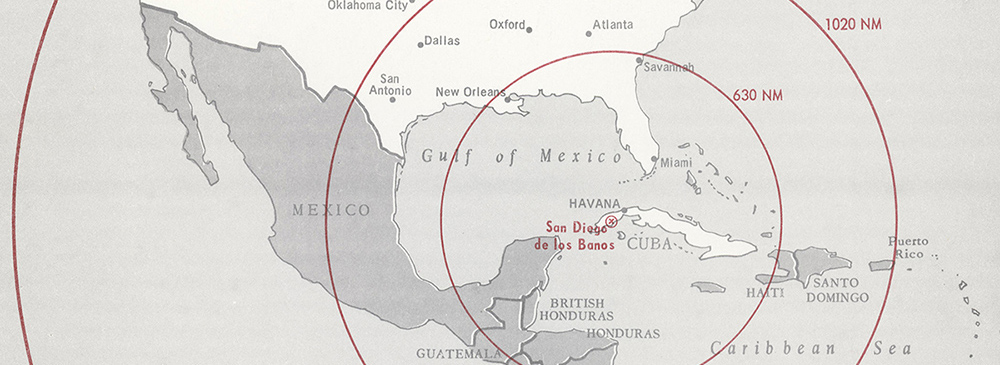

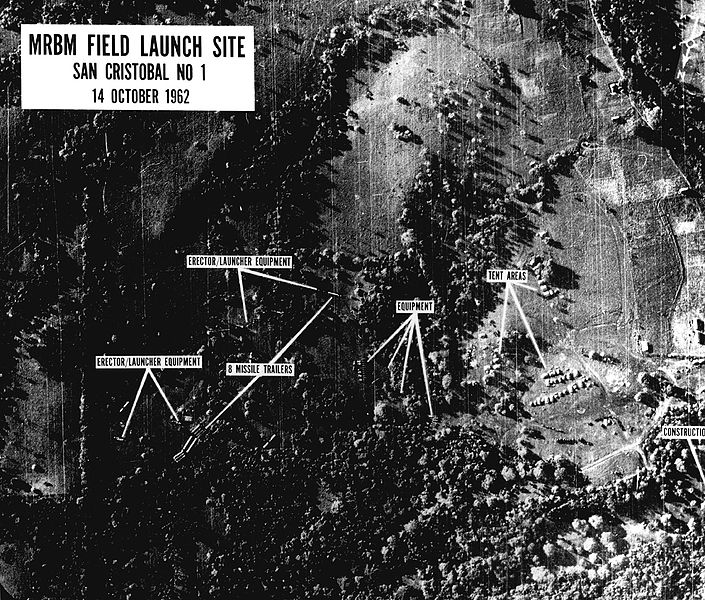

Having promised in May 1960 to defend Cuba with Soviet arms, the Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev assumed that the United States would take no steps to prevent the installation of Soviet medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Cuba. Such missiles could hit much of the eastern United States within a few minutes if launched from Cuba. The United States learned in July 1962 that the Soviet Union had begun missile shipments to Cuba. By August 29 new military construction and the presence of Soviet technicians had been reported by U.S. U-2 spy planes flying over the island, and on October 14 the presence of a ballistic missile on a launching site was reported.

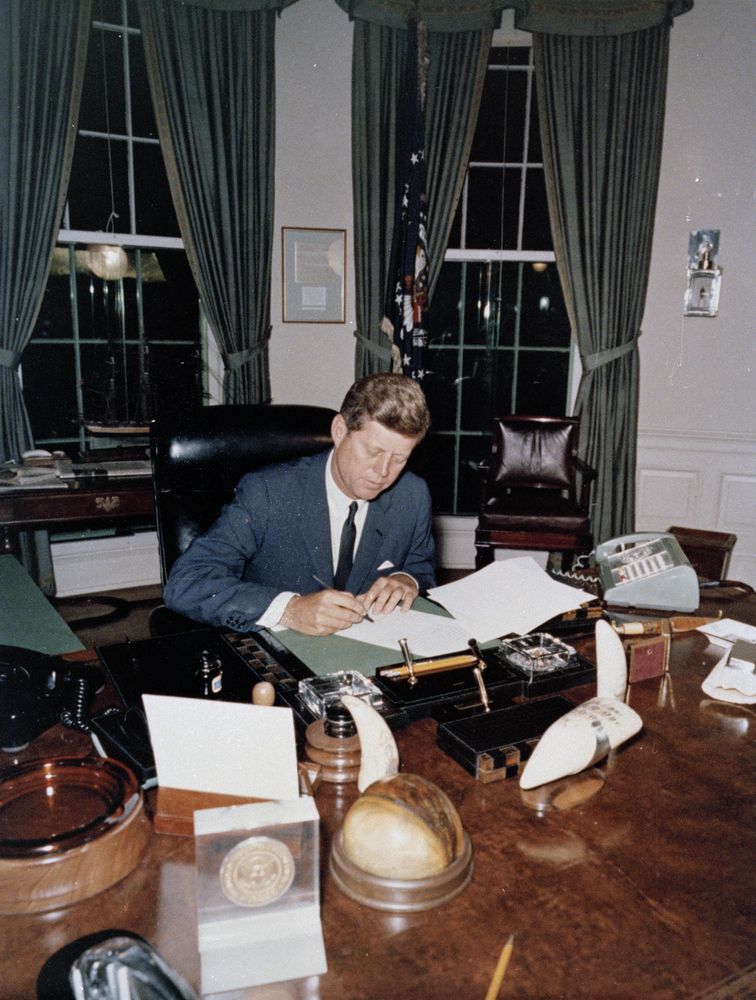

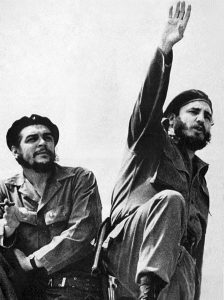

After carefully considering the alternatives of an immediate U.S. invasion of Cuba (or air strikes of the missile sites), a blockade of the island, or further diplomatic maneuvers, U.S. Pres. John F. Kennedy decided to place a naval “quarantine,” or blockade, on Cuba to prevent further Soviet shipments of missiles. Kennedy announced the quarantine on October 22 and warned that U.S. forces would seize “offensive weapons and associated matériel” that Soviet vessels might attempt to deliver to Cuba. During the following days, Soviet ships bound for Cuba altered course away from the quarantined zone. As the two superpowers hovered close to the brink of nuclear war, messages were exchanged between Kennedy and Khrushchev amidst extreme tension on both sides. On October 28 Khrushchev capitulated , informing Kennedy that work on the missile sites would be halted and that the missiles already in Cuba would be returned to the Soviet Union. In return, Kennedy committed the United States to never invading Cuba. Kennedy also secretly promised to withdraw the nuclear-armed missiles that the United States had stationed in Turkey in previous years. In the following weeks both superpowers began fulfilling their promises, and the crisis was over by late November. Cuba’s communist leader, Fidel Castro , was infuriated by the Soviets’ retreat in the face of the U.S. ultimatum but was powerless to act.

The Cuban missile crisis marked the climax of an acutely antagonistic period in U.S.-Soviet relations. The crisis also marked the closest point that the world had ever come to global nuclear war. It is generally believed that the Soviets’ humiliation in Cuba played an important part in Khrushchev’s fall from power in October 1964 and in the Soviet Union’s determination to achieve, at the least, a nuclear parity with the United States.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- John F. Kennedy as president

- Bay of Pigs Invasion

- Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis

- Lyndon Johnson as president

- Vietnam War

- The Vietnam War

- The student movement and the antiwar movement

- Second-wave feminism

- The election of 1968

- 1960s America

- In October 1962, the Soviet provision of ballistic missiles to Cuba led to the most dangerous Cold War confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union and brought the world to the brink of nuclear war.

- Over the course of two extremely tense weeks, US President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev negotiated a peaceful outcome to the crisis.

- The crisis evoked fears of nuclear destruction, revealed the dangers of brinksmanship , and invigorated attempts to halt the arms race.

The Cuban Revolution

Origins of the cuban missile crisis, negotiating a peaceful outcome, consequences of the cuban missile crisis, what do you think.

- Sergo Mikoyan, The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis: Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Missiles of November (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2012), 225-226.

- Strobe Talbott, ed. Khrushchev Remembers (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1970), 494.

- See Michael Dobbs, One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War (New York: Random House, 2008); and Timothy Naftali and Aleksandr Fursenko, One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964: The Secret History of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997).

- See James G. Blight and Philip Brenner, Sad and Luminous Days: Cuba’s Struggle with the Superpowers after the Cuban Missile Crisis (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002).

- Paul S. Boyer, Promises to Keep: The United States since World War II (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), 179.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Cuban Missile Crisis

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 20, 2023 | Original: January 4, 2010

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, leaders of the U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in a tense, 13-day political and military standoff in October 1962 over the installation of nuclear-armed Soviet missiles on Cuba, just 90 miles from U.S. shores. In a TV address on October 22, 1962, President John F. Kennedy (1917-63) notified Americans about the presence of the missiles, explained his decision to enact a naval blockade around Cuba and made it clear the U.S. was prepared to use military force if necessary to neutralize this perceived threat to national security. Following this news, many people feared the world was on the brink of nuclear war. However, disaster was avoided when the U.S. agreed to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s (1894-1971) offer to remove the Cuban missiles in exchange for the U.S. promising not to invade Cuba. Kennedy also secretly agreed to remove U.S. missiles from Turkey.

Discovering the Missiles

After seizing power in the Caribbean island nation of Cuba in 1959, leftist revolutionary leader Fidel Castro (1926-2016) aligned himself with the Soviet Union . Under Castro, Cuba grew dependent on the Soviets for military and economic aid. During this time, the U.S. and the Soviets (and their respective allies) were engaged in the Cold War (1945-91), an ongoing series of largely political and economic clashes.

Did you know? The actor Kevin Costner (1955-) starred in a movie about the Cuban Missile Crisis titled Thirteen Days . Released in 2000, the movie's tagline was "You'll never believe how close we came."

The two superpowers plunged into one of their biggest Cold War confrontations after the pilot of an American U-2 spy plane piloted by Major Richard Heyser making a high-altitude pass over Cuba on October 14, 1962, photographed a Soviet SS-4 medium-range ballistic missile being assembled for installation.

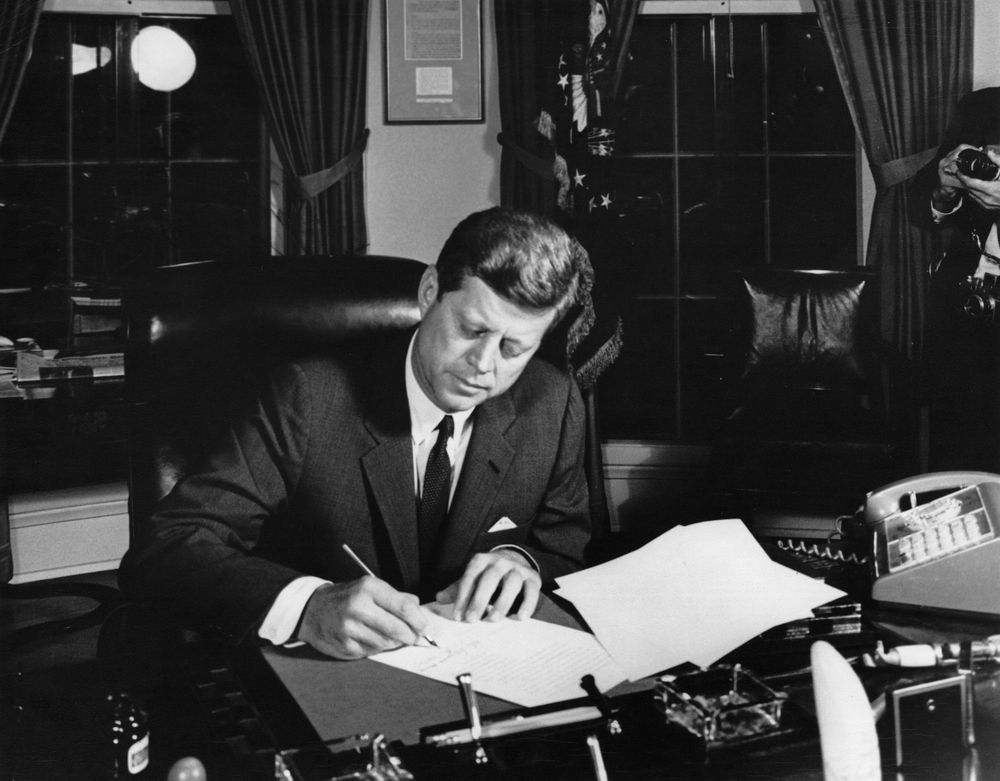

President Kennedy was briefed about the situation on October 16, and he immediately called together a group of advisors and officials known as the executive committee, or ExComm. For nearly the next two weeks, the president and his team wrestled with a diplomatic crisis of epic proportions, as did their counterparts in the Soviet Union.

A New Threat to the U.S.

For the American officials, the urgency of the situation stemmed from the fact that the nuclear-armed Cuban missiles were being installed so close to the U.S. mainland–just 90 miles south of Florida . From that launch point, they were capable of quickly reaching targets in the eastern U.S. If allowed to become operational, the missiles would fundamentally alter the complexion of the nuclear rivalry between the U.S. and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which up to that point had been dominated by the Americans.

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had gambled on sending the missiles to Cuba with the specific goal of increasing his nation’s nuclear strike capability. The Soviets had long felt uneasy about the number of nuclear weapons that were targeted at them from sites in Western Europe and Turkey, and they saw the deployment of missiles in Cuba as a way to level the playing field. Another key factor in the Soviet missile scheme was the hostile relationship between the U.S. and Cuba. The Kennedy administration had already launched one attack on the island–the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961–and Castro and Khrushchev saw the missiles as a means of deterring further U.S. aggression.

Watch the three-episode documentary event, Kennedy . Available to stream now.

Kennedy Weighs the Options

From the outset of the crisis, Kennedy and ExComm determined that the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba was unacceptable. The challenge facing them was to orchestrate their removal without initiating a wider conflict–and possibly a nuclear war. In deliberations that stretched on for nearly a week, they came up with a variety of options, including a bombing attack on the missile sites and a full-scale invasion of Cuba. But Kennedy ultimately decided on a more measured approach. First, he would employ the U.S. Navy to establish a blockade, or quarantine, of the island to prevent the Soviets from delivering additional missiles and military equipment. Second, he would deliver an ultimatum that the existing missiles be removed.

In a television broadcast on October 22, 1962, the president notified Americans about the presence of the missiles, explained his decision to enact the blockade and made it clear that the U.S. was prepared to use military force if necessary to neutralize this perceived threat to national security. Following this public declaration, people around the globe nervously waited for the Soviet response. Some Americans, fearing their country was on the brink of nuclear war, hoarded food and gas.

HISTORY Vault: Nuclear Terror

Now more than ever, terrorist groups are obtaining nuclear weapons. With increasing cases of theft and re-sale at dozens of Russian sites, it's becoming more and more likely for terrorists to succeed.

Showdown at Sea: U.S. Blockades Cuba

A crucial moment in the unfolding crisis arrived on October 24, when Soviet ships bound for Cuba neared the line of U.S. vessels enforcing the blockade. An attempt by the Soviets to breach the blockade would likely have sparked a military confrontation that could have quickly escalated to a nuclear exchange. But the Soviet ships stopped short of the blockade.

Although the events at sea offered a positive sign that war could be averted, they did nothing to address the problem of the missiles already in Cuba. The tense standoff between the superpowers continued through the week, and on October 27, an American reconnaissance plane was shot down over Cuba, and a U.S. invasion force was readied in Florida. (The 35-year-old pilot of the downed plane, Major Rudolf Anderson, is considered the sole U.S. combat casualty of the Cuban missile crisis.) “I thought it was the last Saturday I would ever see,” recalled U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (1916-2009), as quoted by Martin Walker in “The Cold War.” A similar sense of doom was felt by other key players on both sides.

Key Moments in the Cuban Missile Crisis

These are the steps that brought the United States and Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war in 1962.

A Timeline of US‑Cuba Relations

Before Fidel Castro and the Cold War chill, America and Cuba shared close economic and political ties.

JFK Was Completely Unprepared For His Summit with Khrushchev

'He just beat the hell out of me,' Kennedy said.

A Deal Ends the Standoff

Despite the enormous tension, Soviet and American leaders found a way out of the impasse. During the crisis, the Americans and Soviets had exchanged letters and other communications, and on October 26, Khrushchev sent a message to Kennedy in which he offered to remove the Cuban missiles in exchange for a promise by U.S. leaders not to invade Cuba. The following day, the Soviet leader sent a letter proposing that the USSR would dismantle its missiles in Cuba if the Americans removed their missile installations in Turkey.

Officially, the Kennedy administration decided to accept the terms of the first message and ignore the second Khrushchev letter entirely. Privately, however, American officials also agreed to withdraw their nation’s missiles from Turkey. U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy (1925-68) personally delivered the message to the Soviet ambassador in Washington , and on October 28, the crisis drew to a close.

Both the Americans and Soviets were sobered by the Cuban Missile Crisis. The following year, a direct “hot line” communication link was installed between Washington and Moscow to help defuse similar situations, and the superpowers signed two treaties related to nuclear weapons. The Cold War was and the nuclear arms race was far from over, though. In fact, another legacy of the crisis was that it convinced the Soviets to increase their investment in an arsenal of intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of reaching the U.S. from Soviet territory.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Cold War

The cuban missile crisis.

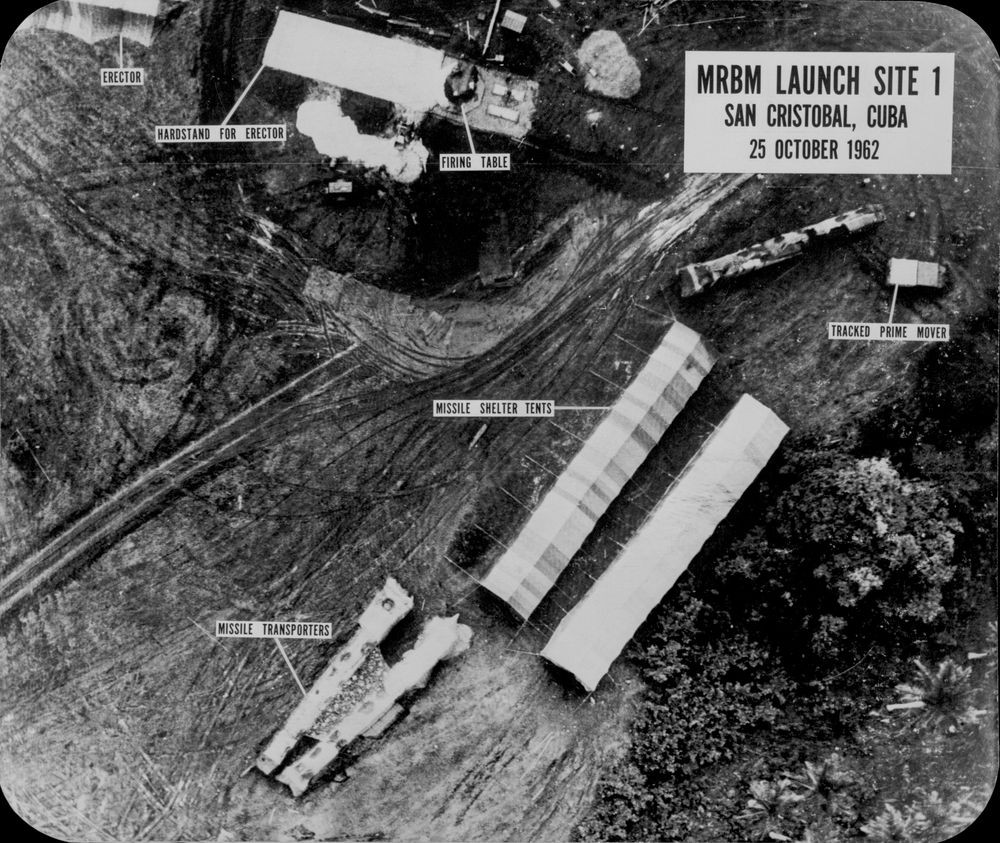

On October 14th 1962, an American U-2 spy plane completed a relatively routine run over the island of Cuba, taking reconnaissance photographs (see picture) from an altitude of 12 miles. When the film was developed it revealed evidence of missiles being assembled and erected on Cuban soil. CIA and military analysts identified them as Soviet medium-range ballistic missiles, capable of carrying nuclear warheads. The presence of these weapons in neighbouring Cuba meant the Soviets could launch attacks on locations in the southern and eastern United States. This would give the Soviet Union a first-strike capacity, giving cities like Washington DC, New York and Philadelphia just a few minutes’ warning. President John F. Kennedy was briefed about the missiles four days later (October 18th). By the end of the day, Kennedy had formed an ‘executive committee’ (EXCOMM), a 13-man team to monitor and assess the situation and formulate response options. EXCOMM’s members included vice-president Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy’s brother Robert, defence secretary Robert McNamara and other advisors from the military and Department of State.

Over the next few days, Kennedy and EXCOMM weighed their options. They agreed that the US could not tolerate the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba. Diplomatic pressure on the Soviets to withdraw the missiles was also ruled out. Advice from EXCOMM suggested the Soviets would respond poorly to belligerent language or actions. An offer of exchange, such as the withdrawal or dismantling of US missile bases in Europe, might make the Kennedy administration appear weak, handing the Russians a propaganda victory. Kennedy’s military hierarchs recommended an airstrike to destroy the missiles, followed by a ground invasion of Cuba to eliminate Fidel Castro and his regime. But Kennedy – now more wary of military advice since the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba – wanted to avoid a military confrontation with the Soviet Union. Instead, he authorised a naval blockade of the island. The US would draw a firm line around Cuba while seeking to avoid hostile action that risked triggering a nuclear war.

On October 22nd, Kennedy addressed the nation by television, announcing a “quarantine” of the Cuban island. He also said his administration would regard any missile attack launched from Cuba as an attack by the USSR, necessitating a full retaliatory response. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev described Kennedy’s quarantine as a “pirate action” and informed Kennedy by telegram that Soviet ships would ignore it. Kennedy reminded Khrushchev that the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba breached an earlier promise by the Soviet government. US Navy warships initiated their quarantine of Cuba. They allowed some small freighters through but stopped larger vessels for inspection, finding no military equipment. Meanwhile, American U-2s continued their missions over Cuba, flying every two hours. These overflights reported no pause or slow-down in the assembly of Soviet missiles.

There was no change in the situation after four days of quarantine. Kennedy came under pressure from his generals, who urged an airstrike to destroy the missiles before they became operational. At this point, a military confrontation between the US and USSR seemed almost inevitable, generating fear about a possible nuclear exchange. All levels of government hastily organised civil defence measures such as public bomb shelters; in most cases, these were capable of sheltering barely one-third of the population. Some citizens constructed their own shelters and stockpiled tinned food and other necessities. Many gathered in prayer in their local churches. Others packed up their belongings and took extended vacations with family members in remote areas where nuclear missiles were less likely to fall. In Soviet Russia, press censorship meant that most citizens were largely unaware of the crisis unfolding in the Caribbean.

The stalemate was broken by a series of developments across two days. On October 25th Adlai Stevenson, the US ambassador to the United Nations, confronted the Soviet ambassador in the Security Council with photographic evidence of the Cuban missiles. Given their previous denials, this publicly exposed Soviet dishonesty during the crisis. Around this time the White House also received a backroom offer to resolve the crisis, passed to a Washington reporter by a Soviet agent. On October 26th, the US State Department received a long, rambling letter, purportedly from Khrushchev. This letter promised to withdraw the Cuban missiles, provided the US pledged to never attack or invade Cuba. A follow-up message proposed a more direct exchange: the removal of the Cuban missiles, in return for the removal of American Jupiter missiles from Turkey and Italy. Kennedy agreed to this, provided the deal was not made public. The arrangement was finalised on the evening of October 27th, though it almost fell through after an American U-2 was shot down over Cuba by a Soviet surface-to-air missile. Kennedy resisted considerable pressure from his generals to retaliate. It later emerged the Soviets in Cuba had fired on the U-2 without authorisation from Moscow.

“The die was cast when the president met with his Executive Committee in the Oval Room at 2.30pm. It was a long and, toward the end, an unexpectedly bitter session. The choices put toward Kennedy that afternoon were two: begin with the naval blockade and, if need be, move up the ladder of military responses, rung by rung; or begin with an air strike then move almost certainly to a full-scale invasion of Cuba… The president paused gravely before speaking his mind. He said that he preferred to start with limited action. An air attack, he felt, was the wrong way to start… Kennedy was still expecting a Soviet move against Berlin, whatever happened in Cuba.” Elie Abel, journalist

The Cuban missile crisis was arguably the ‘hottest’ point of the Cold War, the closest the world has come to nuclear destruction. As US Secretary of State Dean Rusk noted toward the end of the crisis, “We were eyeball to eyeball and the other guy just blinked”. Information revealed years later suggested that the crisis could easily have deteriorated into a nuclear exchange. Soviet officers in Cuba were equipped with about 100 tactical nuclear weapons – and the authority to use them if attacked. Castro, convinced that an American invasion was imminent, urged both Khrushchev and Soviet commanders in Cuba to launch a pre-emptive strike against the US. And during the naval quarantine, a US destroyer dropped depth charges on a Soviet submarine which, unbeknownst to the Americans, was armed with a 15 kiloton nuclear missile and authority to use it. Given that several Soviet officers were authorised to fire nuclear weapons of their own accord, Kennedy’s delicate handling of the situation seems judicious. In the wake of the crisis, the Soviets reorganised their command structure and nuclear launch protocols, while the White House and Kremlin installed a ‘hotline’ to ensure direct communication in the event of a similar emergency.

1. The Cuban missile crisis unfolded in October 1962, following the discovery by US spy planes of Soviet missile sites being installed on nearby Cuba.

2. Missiles in Cuba gave the Soviet Union a ‘first-strike’ capacity. Unwilling to tolerate this, President Kennedy formed a committee to orchestrate their removal.

3. Considering all options from diplomatic pressure to an airstrike or invasion, EXCOMM settled on a naval “quarantine” of all Soviet ships sailing to Cuba.

4. The Cuban crisis and the US blockade carried a significant risk of military confrontation between the US and USSR, with the consequent risk of nuclear war.

5. The crisis was eventually resolved through a secret deal, in which the Soviets withdrew the Cuban missiles in return for the withdrawal of American Jupiter missiles from Turkey and Italy.

A CIA appraisal of the political, economic and military situation in Cuba (August 1962) A CIA report on the Soviet-backed military build up in Cuba (September 1962) US intelligence report says the installation of Soviet missiles in Cuba is unlikely (September 1962) The first intelligence reports of Soviet ballistic missiles in Cuba (October 1962) An evaluation of the Soviet missile threat in Cuba, by US intelligence bodies (October 1962) Kennedy and his advisors discuss a response to the Cuban missiles (October 1962) President John F Kennedy announces a naval quarantine of Cuba (October 1962) Castro responds to Kennedy’s announcement of a blockade (October 1962) Adlai Stevenson confronts Soviet ambassador Zorin in the UN Security Council (October 1962) Khrushchev’s letter to Kennedy urging a resolution of the crisis (October 1962) Delegates from the US and USSR debate the Cuban missile crisis in the UN (October 1962) Kennedy’s alternative speech announcing an attack on Cuba (October 1962) The Missiles of October (1974 film) Thirteen Days (2000 film) Robert McNamara reflects on the Cuban missile crisis (2003)

Content on this page is © Alpha History 2018. This content may not be republished or distributed without permission. For more information please refer to our Terms of Use . This page was written by Jennifer Llewellyn, Jim Southey and Steve Thompson. To reference this page, use the following citation: J. Llewellyn et al, “The Cuban missile crisis”, Alpha History, accessed [today’s date], https://alphahistory.com/coldwar/cuban-missile-crisis/.

Will you join us in lighting the way for the leaders of tomorrow?

Cuban missile crisis, for thirteen days in october 1962 the world waited—seemingly on the brink of nuclear war—and hoped for a peaceful resolution to the cuban missile crisis..

In October 1962, an American U-2 spy plane secretly photographed nuclear missile sites being built by the Soviet Union on the island of Cuba. President Kennedy did not want the Soviet Union and Cuba to know that he had discovered the missiles. He met in secret with his advisors for several days to discuss the problem.

After many long and difficult meetings, Kennedy decided to place a naval blockade, or a ring of ships, around Cuba. The aim of this "quarantine," as he called it, was to prevent the Soviets from bringing in more military supplies. He demanded the removal of the missiles already there and the destruction of the sites. On October 22, President Kennedy spoke to the nation about the crisis in a televised address.

Click here to listen to the Address in the Digital Archives (JFKWHA-142-001)

No one was sure how Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev would respond to the naval blockade and US demands. But the leaders of both superpowers recognized the devastating possibility of a nuclear war and publicly agreed to a deal in which the Soviets would dismantle the weapon sites in exchange for a pledge from the United States not to invade Cuba. In a separate deal, which remained secret for more than twenty-five years, the United States also agreed to remove its nuclear missiles from Turkey. Although the Soviets removed their missiles from Cuba, they escalated the building of their military arsenal; the missile crisis was over, the arms race was not.

Click here to listen to the Remarks in the Digital Archives (JFKWHA-143-004)

In 1963, there were signs of a lessening of tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States. In his commencement address at American University, President Kennedy urged Americans to reexamine Cold War stereotypes and myths and called for a strategy of peace that would make the world safe for diversity. Two actions also signaled a warming in relations between the superpowers: the establishment of a teletype "Hotline" between the Kremlin and the White House and the signing of the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty on July 25, 1963.

In language very different from his inaugural address, President Kennedy told Americans in June 1963, "For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children's future. And we are all mortal."

Visit our online exhibit: World on the Brink: John F. Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis

Milestones: 1961–1968

The cuban missile crisis, october 1962.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 was a direct and dangerous confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War and was the moment when the two superpowers came closest to nuclear conflict. The crisis was unique in a number of ways, featuring calculations and miscalculations as well as direct and secret communications and miscommunications between the two sides. The dramatic crisis was also characterized by the fact that it was primarily played out at the White House and the Kremlin level with relatively little input from the respective bureaucracies typically involved in the foreign policy process.

After the failed U.S. attempt to overthrow the Castro regime in Cuba with the Bay of Pigs invasion, and while the Kennedy administration planned Operation Mongoose, in July 1962 Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev reached a secret agreement with Cuban premier Fidel Castro to place Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba to deter any future invasion attempt. Construction of several missile sites began in the late summer, but U.S. intelligence discovered evidence of a general Soviet arms build-up on Cuba, including Soviet IL–28 bombers, during routine surveillance flights, and on September 4, 1962, President Kennedy issued a public warning against the introduction of offensive weapons into Cuba. Despite the warning, on October 14 a U.S. U–2 aircraft took several pictures clearly showing sites for medium-range and intermediate-range ballistic nuclear missiles (MRBMs and IRBMs) under construction in Cuba. These images were processed and presented to the White House the next day, thus precipitating the onset of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Kennedy summoned his closest advisers to consider options and direct a course of action for the United States that would resolve the crisis. Some advisers—including all the Joint Chiefs of Staff—argued for an air strike to destroy the missiles, followed by a U.S. invasion of Cuba; others favored stern warnings to Cuba and the Soviet Union. The President decided upon a middle course. On October 22, he ordered a naval “quarantine” of Cuba. The use of “quarantine” legally distinguished this action from a blockade, which assumed a state of war existed; the use of “quarantine” instead of “blockade” also enabled the United States to receive the support of the Organization of American States.

That same day, Kennedy sent a letter to Khrushchev declaring that the United States would not permit offensive weapons to be delivered to Cuba, and demanded that the Soviets dismantle the missile bases already under construction or completed, and return all offensive weapons to the U.S.S.R. The letter was the first in a series of direct and indirect communications between the White House and the Kremlin throughout the remainder of the crisis.

The President also went on national television that evening to inform the public of the developments in Cuba, his decision to initiate and enforce a “quarantine,” and the potential global consequences if the crisis continued to escalate. The tone of the President’s remarks was stern, and the message unmistakable and evocative of the Monroe Doctrine: “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” The Joint Chiefs of Staff announced a military readiness status of DEFCON 3 as U.S. naval forces began implementation of the quarantine and plans accelerated for a military strike on Cuba.

On October 24, Khrushchev responded to Kennedy’s message with a statement that the U.S. “blockade” was an “act of aggression” and that Soviet ships bound for Cuba would be ordered to proceed. Nevertheless, during October 24 and 25, some ships turned back from the quarantine line; others were stopped by U.S. naval forces, but they contained no offensive weapons and so were allowed to proceed. Meanwhile, U.S. reconnaissance flights over Cuba indicated the Soviet missile sites were nearing operational readiness. With no apparent end to the crisis in sight, U.S. forces were placed at DEFCON 2—meaning war involving the Strategic Air Command was imminent. On October 26, Kennedy told his advisors it appeared that only a U.S. attack on Cuba would remove the missiles, but he insisted on giving the diplomatic channel a little more time. The crisis had reached a virtual stalemate.

That afternoon, however, the crisis took a dramatic turn. ABC News correspondent John Scali reported to the White House that he had been approached by a Soviet agent suggesting that an agreement could be reached in which the Soviets would remove their missiles from Cuba if the United States promised not to invade the island. While White House staff scrambled to assess the validity of this “back channel” offer, Khrushchev sent Kennedy a message the evening of October 26, which meant it was sent in the middle of the night Moscow time. It was a long, emotional message that raised the specter of nuclear holocaust, and presented a proposed resolution that remarkably resembled what Scali reported earlier that day. “If there is no intention,” he said, “to doom the world to the catastrophe of thermonuclear war, then let us not only relax the forces pulling on the ends of the rope, let us take measures to untie that knot. We are ready for this.”

Although U.S. experts were convinced the message from Khrushchev was authentic, hope for a resolution was short-lived. The next day, October 27, Khrushchev sent another message indicating that any proposed deal must include the removal of U.S. Jupiter missiles from Turkey. That same day a U.S. U–2 reconnaissance jet was shot down over Cuba. Kennedy and his advisors prepared for an attack on Cuba within days as they searched for any remaining diplomatic resolution. It was determined that Kennedy would ignore the second Khrushchev message and respond to the first one. That night, Kennedy set forth in his message to the Soviet leader proposed steps for the removal of Soviet missiles from Cuba under supervision of the United Nations, and a guarantee that the United States would not attack Cuba.

It was a risky move to ignore the second Khrushchev message. Attorney General Robert Kennedy then met secretly with Soviet Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin, and indicated that the United States was planning to remove the Jupiter missiles from Turkey anyway, and that it would do so soon, but this could not be part of any public resolution of the missile crisis. The next morning, October 28, Khrushchev issued a public statement that Soviet missiles would be dismantled and removed from Cuba.

The crisis was over but the naval quarantine continued until the Soviets agreed to remove their IL–28 bombers from Cuba and, on November 20, 1962, the United States ended its quarantine. U.S. Jupiter missiles were removed from Turkey in April 1963.

The Cuban missile crisis stands as a singular event during the Cold War and strengthened Kennedy’s image domestically and internationally. It also may have helped mitigate negative world opinion regarding the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. Two other important results of the crisis came in unique forms. First, despite the flurry of direct and indirect communications between the White House and the Kremlin—perhaps because of it—Kennedy and Khrushchev, and their advisers, struggled throughout the crisis to clearly understand each others’ true intentions, while the world hung on the brink of possible nuclear war. In an effort to prevent this from happening again, a direct telephone link between the White House and the Kremlin was established; it became known as the “Hotline.” Second, having approached the brink of nuclear conflict, both superpowers began to reconsider the nuclear arms race and took the first steps in agreeing to a nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

Help inform the discussion

- X (Twitter)

JFK and the Cuban Missile Crisis

Listen in on the signature crisis of JFK's presidency

The Cuban Missile Crisis was the signature moment of John F. Kennedy's presidency. The most dramatic parts of that crisis—the famed "13 days"—lasted from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy first learned that the Soviet Union was constructing missile launch sites in Cuba, to October 28, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev publicly announced he was removing the missiles from the island nation.

Tensions continued, however, until November 20, when Kennedy lifted the blockade he had placed around Cuba after confirming that all offensive weapons systems had been dismantled, and that Soviet nuclear-capable bombers were to be removed from the island.

The potential for a nuclear war was real, and the following Miller Center exhibits from our Kennedy collection capture the president's thoughts and the advice he was receiving.

Date : Oct 19, 1962 Time : 9:45 a.m. Participants : John Kennedy, Curtis LeMay

While discussing various options for dealing with the threat posed by Soviet missiles in Cuba, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, after criticizing calls to blockade the island, sums up the president's political and military troubles.

Date: Oct 22, 1962 Participants: John Kennedy, Dwight Eisenhower

President Kennedy had taken pains to be sure Eisenhower was briefed on the Cuban Missile Crisis by John McCone, first on October 17 to give him the news of the deployment and then again on October 21 to tell the former president about the blockade-ultimatum decision. Having already heard from McCone about Eisenhower's supportive reaction, President Kennedy wants to discuss his dilemma directly with one of the few living men who will truly understand what he faces. Despite the distance between the two men in age, experience, and political stance, it is not the first time they have confided in each other, and it will not be the last.

Date : Oct 24, 1962 Time : 10:00 a.m. Participants : John F. Kennedy, McGeorge Bundy, C. Douglas Dillon, Roswell Gilpatric, U. Alexis Johnson, Robert Kennedy, Robert G. Kreer, Arthur Lundahl, John McCone, General McDavid, Robert McNamara, Paul Nitze, Kenneth O’Donnell, Dean Rusk, Theodore Sorensen, Maxwell Taylor, Jerome Wiesner

In this recording, President Kennedy consults with the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (commonly referred to as simply the Executive Committee or ExComm) about possible reactions to the growing Cuban Missile Crisis.

Date : Oct 26, 1962 Time : 9:59 a.m. Participants : John F. Kennedy, McGeorge Bundy, C. Douglas Dillon, Roswell Gilpatric, U. Alexis Johnson, Robert Kennedy, Robert G. Kreer, Arthur Lundahl, John McCone, General McDavid, Robert McNamara, Paul Nitze, Kenneth O’Donnell, Dean Rusk, Theodore Sorensen, Maxwell Taylor, Jerome Wiesner

In this recording, President Kennedy consults with the ExComm about the unfolding of the Cuban Missile Crisis and how the situation might be resolved.

Date : Oct 26, 1962 Time : 6:30 p.m. Participants : John F. Kennedy, Harold Macmillan

Kennedy placed this call after having held crisis meetings with advisers all day. Macmillan received the call around midnight London time. U Thant, acting secretary-general of the United Nations, had been holding round-the-clock talks in New York. In the latest development, US Ambassador to the United Nations, Adlai Stevenson, had met with U Thant earlier that day in New York. U Thant, in turn, had been talking Soviet Ambassador to the United Nations Valerian Zorin.

Date : Oct 27, 1962 Time : 4:00 p.m. Participants : John F. Kennedy, McGeorge Bundy, Alexis Johnson

President Kennedy and his advisers consider the ramifications of trading Jupiter missiles in Turkey for Soviet missiles in Cuba.

Epic Misadventure

"who would want to read a book on disasters”.

Miller Center expert Marc Selverstone examines Kennedy's foreign policy struggles

Essay: The Lessons of the Cuban Missile Crisis

For 13 chilling days in October 1962, it seemed that John F. Kennedy and Nikita S. Khrushchev might be playing out the opening scenes of World War III. The Cuban missile crisis was a uniquely compact moment of history. For the first time in the nuclear age, the two superpowers found themselves in a sort of moral road test of their apocalyptic powers.

The crisis blew up suddenly. The U.S. discovered that the Soviet Union, despite repeated and solemn denials, was installing nuclear missiles in Cuba. An American U-2 spy plane came back with photographs of the bases and their support facilities under construction: clear, irrefutable evidence. Kennedy assembled a task force of advisers. Some of them wanted to invade Cuba. In the end, Kennedy chose a course of artful restraint; he laid down a naval quarantine. After six days, Khrushchev announced that the Soviet missiles would be dismantled.

The crisis served some purposes. The U.S. and the Soviet Union have had no comparable collision since then. On the other hand, the humiliation that Khrushchev suffered may have hastened his fall. The experience may be partly responsible for both the Soviet military buildup in the past two decades and whatever enthusiasm the Soviets have displayed for nuclear disarmament.

Now, on the 20th anniversary of the crisis, six of Kennedy’s men have collaborated on a remarkable joint statement on the lessons of that October. It contains some new information, particularly in Point Eight, and at least one of their conclusions is startling and controversial: their thought that, contrary to the widespread assumption of the past two decades, the American nuclear superiority over the Soviets in 1962 had no crucial influence with Washington or Moscow at the time—and that in general, nuclear superiority is insignificant.

The authors are Dean Rusk, then Secretary of State; Robert McNamara, Secretary of Defense; George W. Ball, Under Secretary of State; Roswell L. Gilpatric, Deputy Secretary of Defense; Theodore Sorensen, special counsel to the President; and McGeorge Bundy, special assistant to the President for national security affairs. Their analysis:

In the years since the Cuban missile crisis, many commentators have examined the affair and offered a wide variety of conclusions. It seems fitting now that some of us who worked particularly closely with President Kennedy during that crisis should offer a few comments, with the advantages both of participation and of hindsight.

FIRST: The crisis could and should have been avoided. If we had done an earlier, stronger and clearer job of explaining our position on Soviet nuclear weapons in the Western Hemisphere, or if the Soviet government had more carefully assessed the evidence that did exist on this point, it is likely that the missiles would never have been sent to Cuba. The importance of accurate mutual assessment of interests between the two superpowers is evident and continuous.

SECOND: Reliable intelligence permitting an effective choice of response was obtained only just in time. It was primarily a mistake by policymakers, not by professionals, that made such intelligence unavailable sooner. But it was also a timely recognition of the need for thorough overflight, not without its hazards, that produced the decisive photographs. The usefulness and scope of inspection from above, also employed in monitoring the Soviet missile withdrawal, should never be underestimated. When the importance of accurate information for a crucial policy decision is high enough, risks not otherwise acceptable in collecting intelligence can become profoundly prudent.

THIRD: The President wisely took his time in choosing a course of action. A quick decision would certainly have been less carefully designed and could well have produced a much higher risk of catastrophe. The fact that the crisis did not become public in its first week obviously made it easier for President Kennedy to consider his options with a maximum of care and a minimum of outside pressure. Not every future crisis will be so quiet in its first phase, but Americans should always respect the need for a period of confidential and careful deliberation in dealing with a major international crisis.

FOURTH: The decisive military element in the resolution of the crisis was our clearly available and applicable superiority in conventional weapons within the area of the crisis. U.S. naval forces, quickly deployable for the blockade of offensive weapons that was sensibly termed a quarantine, and the availability of U.S. ground and air forces sufficient to execute an invasion if necessary, made the difference. American nuclear superiority was not in our view a critical factor, for the fundamental and controlling reason that nuclear war, already in 1962, would have been an unexampled catastrophe for both sides; the balance of terror so eloquently described by Winston Churchill seven years earlier was in full operation. No one of us ever reviewed the nuclear balance for comfort in those hard weeks. The Cuban missile crisis illustrates not the significance but the insignificance of nuclear superiority in the face of survivable thermonuclear retaliatory forces. It also shows the crucial role of rapidly available conventional strength.

FIFTH: The political and military pressure created by the quarantine was matched by a diplomatic effort that ignored no relevant means of communication with both our friends and our adversary. Communication to and from our allies in Europe was intense, and their support sturdy. The Organization of American States gave the moral and legal authority of its regional backing to the quarantine, making it plain that Soviet nuclear weapons were profoundly unwelcome in the Americas. In the U.N., Ambassador Adlai Stevenson drove home with angry eloquence and unanswerable photographic evidence the facts of the Soviet deployment and deception.

Still more important, communication was established and maintained, once our basic course was set, with the government of the Soviet Union. If the crisis itself showed the cost of mutual incomprehension, its resolution showed the value of serious and sustained communication, and in particular of direct exchanges between the two heads of government.

When great states come anywhere near the brink in the nuclear age, there is no room for games of blindman’s buff. Nor can friends be led by silence. They must know what we are doing and why. Effective communication is never more important than when there is a military confrontation.

SIXTH: This diplomatic effort and indeed our whole course of action were greatly reinforced by the fact that our position was squarely based on irrefutable evidence that the Soviet government was doing exactly what it had repeatedly denied that it would do. The support of our allies and the readiness of the Soviet government to draw back were heavily affected by the public demonstration of a Soviet course of conduct that simply could not be defended. In this demonstration no evidence less explicit and authoritative than that of photography would have been sufficient, and it was one of President Kennedy’s best decisions that the ordinary requirements of secrecy in such matters should be brushed aside in the interest of persuasive exposition. There are times when a display of hard evidence is more valuable than protection of intelligence techniques.

SEVENTH: In the successful resolution of the crisis, restraint was as important as strength. In particular, we avoided any early initiation of battle by American forces, and indeed we took no action of any kind that would have forced an instant and possibly ill-considered response. Moreover, we limited our demands to the restoration of the status quo ante, that is, the removal of any Soviet nuclear capability from Cuba. There was no demand for “total victory” or “unconditional surrender.” These choices gave the Soviet government both time and opportunity to respond with equal restraint. It is wrong, in relations between the superpowers, for either side to leave the other with no way out but war or humiliation.

EIGHTH: On two points of particular interest to the Soviet government, we made sure that it had the benefit of knowing the independently reached positions of President Kennedy. One assurance was public and the other private.

Publicly we made it clear that the U.S. would not invade Cuba if the Soviet missiles were withdrawn. The President never shared the view that the missile crisis should be “used” to pick a fight to the finish with Castro; he correctly insisted that the real issue in the crisis was with the Soviet government, and that the one vital bone of contention was the secret and deceit-covered movement of Soviet missiles into Cuba. He recognized that an invasion by U.S. forces would be bitter and bloody, and that it would leave festering wounds in the body politic of the Western Hemisphere. The no-invasion assurance was not a concession, but a statement of our own clear preference—once the missiles were withdrawn.

The second and private assurance—communicated on the President’s instructions by Robert Kennedy to Soviet Ambassador Anatoli Dobrynin on the evening of Oct. 27—was that the President had determined that once the crisis was resolved, the American missiles then in Turkey would be removed. (The essence of this secret assurance was revealed by Robert Kennedy in his 1969 book Thirteen Days, and a more detailed account, drawn from many sources but not from discussion with any of us, was published by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. in Robert Kennedy and His Times in 1978. In these circumstances, we think it is now proper for those of us privy to that decision to discuss the matter.) This could not be a “deal”—our missiles in Turkey for theirs in Cuba—as the Soviet government had just proposed. The matter involved the concerns of our allies, and we could not put ourselves in the position of appearing to trade their protection for our own. But in fact President Kennedy had long since reached the conclusion that the outmoded and vulnerable missiles in Turkey should be withdrawn. In the spring of 1961 Secretary Rusk had begun the necessary discussions with high Turkish officials. These officials asked for delay, at least until Polaris submarines could be deployed in the Mediterranean. While the matter was not pressed to a conclusion in the following year and a half, the missile crisis itself reinforced the President’s convictions. It was entirely right that the Soviet government should understand this reality.

This second assurance was kept secret because the few who knew about it at the time were in unanimous agreement that any other course would have had explosive and destructive effects on the security of the U.S. and its allies. If made public in the context of the Soviet proposal to make a “deal,” the unilateral decision reached by the President would have been misread as an unwilling concession granted in fear at the expense of an ally. It seemed better to tell the Soviets the real position in private, and in a way that would prevent any such misunderstanding. Robert Kennedy made it plain to Ambassador Dobrynin that any attempt to treat the President’s unilateral assurance as part of a deal would simply make that assurance inoperative.

Although for separate reasons neither the public nor the private assurance ever became a formal commitment of the U.S. Government, the validity of both was demonstrated by our later actions; there was no invasion of Cuba, and the vulnerable missiles in Turkey (and Italy) were withdrawn, with allied concurrence, to be replaced by invulnerable Polaris submarines. Both results were in our own clear interest, and both assurances were helpful in making it easier for the Soviet government to decide to withdraw its missiles.

In part this was secret diplomacy, including a secret assurance. Any failure to make good on that assurance would obviously have had damaging effects on Soviet-American relations. But it is of critical importance here that the President gave no assurance that went beyond his own presidential powers; in particular he made no commitment that required congressional approval or even support. The decision that the missiles in Turkey should be removed was one that the President had full and unquestioned authority to make and execute.

When it will help your own country for your adversary to know your settled intentions, you should find effective ways of making sure that he does, and a secret assurance is justified when a) you can keep your word, and b) no other course can avoid grave damage to your country’s legitimate interests.

NINTH: The gravest risk in this crisis was not that either head of government desired to initiate a major escalation but that events would produce actions, reactions or miscalculations carrying the conflict beyond the control of one or the other or both. In retrospect we are inclined to think that both men would have taken every possible step to prevent such a result, but at the time no one near the top of either government could have that certainty about the other side. In any crisis involving the superpowers, firm control by the heads of both governments is essential to the avoidance of an unpredictably escalating conflict.

TENTH: The successful resolution of the Cuban missile crisis was fundamentally the achievement of two men, John F. Kennedy and Nikita S. Khrushchev. We know that in this anniversary year John Kennedy would wish us to emphasize the contribution of Khrushchev; the fact that an earlier and less prudent decision by the Soviet leader made the crisis inevitable does not detract from the statesmanship of his change of course. We may be forgiven, however, if we give the last and highest word of honor to our own President, whose cautious determination, steady composure, deep-seated compassion and, above all, continuously attentive control of our options and actions brilliantly served his country and all mankind. –

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The Reintroduction of Kamala Harris

- The 7 States That Will Decide the Election

- Is the U.S. Ready for Psychedelics?

- Inside Sam Bankman-Fried's Siege of D.C.

- Do You Really Store Stress in Your Body?

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The 50 Best Romance Novels to Read Right Now

- Can Food Really Change Your Hormones?

Contact us at [email protected]

Naval History and Heritage Command

- Navy Birthday Commemoration Resources

- Navy History and Imagery

- Archived Content

- Pearl Harbor Remembrance

- Battle of Midway

- National Vietnam War Veterans Day

- Visual Resources

- Oral Histories

- Additional Reading

- Communication Resources

- Photo Gallery

- American Revolution

- Quasi-War with France

- Barbary Wars

- War of 1812

- Mexican-American War

- General Studies

- Operations and Engagements

- Medals and Awards

- Publications

- U.S. Capture of Guam

- Philippine Insurrection, 1899-1902

- The Boxer Rebellion: Bluejackets and Marines in China, 1900-1901

- The Occupation of Veracruz, Mexico, 1914

- The U.S. Navy in the Far East—The U.S. Asiatic Fleet: From Its Origins to World War II

- Documentary History

- Ships and Aircraft

- Tactics and Technology

- General Collections

- World War II Profiles in Duty

- Operation Crossroads

- Strategic Deterrence

- The Human Cost

- A Changing Navy

Cuban Missile Crisis

- The "Six-Day War" and USS Liberty

- Iran Hostage Crisis

- Lebanon—They Came in Peace

- Operation Praying Mantis

- Desert Shield/Desert Storm

- Operation Enduring Freedom

- Operation Iraqi Freedom

- Pirate Interdiction and the U.S. Navy

- Escape From the Pentagon: NSWC Crane Group on 9/11

- Operation Allied Force

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1776-1783

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1797

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1802

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1812-1815

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1815

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1830-1841

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1841

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1852

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1852-1855

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1862-1863

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1864

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1898

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1900

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1905-1913

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1917-1918

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1918-1919

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1922-1931

- Uniforms of the U.S Navy 1941

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1942-1943

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1943-1944

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1951-1952

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1961

- Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1967

- Sailors' Tattoos

- Goats and the U.S. Navy

- Navy Athletics

- The Sailor’s Creed

- The Ship’s Bell

- Striking the Flag

- Unofficial Navy Certificates

- Precedence of Forces in Parades

- Passing Honors, National Anniversaries, and Solemnities

- Rocks and Shoals: Articles for the Government of the U.S. Navy

- Plank Owners

- Ship Naming

- Twenty-One Gun Salute

- Change of Command

- Commissioning Pennant

- Ship Launching and Commissioning

- Burial at Sea

- Crossing the Line

- Origins of the U.S. Navy Flag

- Submarine Battle Flags

- The U.S. Navy's Jack

- Battle Streamers

- Personal Military Decorations

- Service and Campaign Awards

- Special Order No. 81

- Meaning and Origin of Nautical Terms

- Famous Navy Quotations

- Birth of the U.S. Navy

- Washington Signs the Naval Act of 1794

- U.S. Navy History Lessons Learned

- The Navy and Marine Corps Team

- The U.S. Naval Academy: Images of History

- The U.S. Naval Academy During the World War II Era

- Chaplain Corps Manual

- United States Navy Chief Petty Officer Creed

- The Chief Petty Officer's Pledge

- Chief Petty Officer Recipients of the Medal of Honor

- One Hundred Years of Leadership

- Navy Medicine Medal of Honor Recipients

- Nurses in the U.S. Navy Bibliography and Sources

- The Formative Years of the U.S. Navy Medical Corps, 1798−1871

- Navy Medical Corps

- Navy Nurse Corps

- 1898–1916

- 1917–1919

- 1920–1929

- 1930–1939

- 1940–1945

- 1946–1949

- 1950–1953

- 1954–1959

- 1960–1969

- 1970–1979

- 1980–1989

- 1990–1999

- 2000–2010

- Notable Aircraft

- Notable Aviators

- Notable Squadrons

- Airships and Dirigibles

- Submarine Force

- Age of Sail

- Sail to Steam Propulsion

- Modern Surface Warfare

- Navy Divers

- Naval Special Warfare

- Supply Corps

- Explosive Ordnance Disposal

- The Navy’s Humanitarian Mission

- U-2s, UFOs, and Operation Blue Book

- Port Chicago Naval Magazine Explosion

- The Sullivan Brothers and the Assignment of Family Members

- Weather Related Incidents

- The Loss of Flight 19

- Comparison of Military and Civilian Equivalent Grades

- Why is the Colonel Called "Kernal"?

- Enlisted Personnel

- Regulations and Policy

- Navy Service and Medical Records

- Military Service Records and Unit Histories: A Guide to Locating Sources

- Navy Personnel: A Research Guide

- Washington Navy Yard, District of Columbia

- Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia

- Naval Submarine Base New London, Connecticut

- Naval Station Mayport, Florida

- Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida

- Naval Station Great Lakes, Illinois

- Naval Base San Diego, California

- Naval Base Kitsap, Washington

- Naval Station Pearl Harbor, Hawaii

- U.S. Fleet Activities Yokosuka, Japan

- Naval Support Activity Bahrain

- Naval Support Activity Naples, Italy

- Mare Island Naval Shipyard

- New York (Brooklyn) Navy Yard

- The Philippines

- The Forgotten Bases of Ireland

- Hughie Lee-Smith

- Agnes Meyer Driscoll—The First Lady of Naval Cryptology

- Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. Navy

- Hispanic Americans in the U.S. Navy

- Contributions of Native Americans to the U.S. Navy

- Naval Service of LGBTQI+ Personnel

- Electricity and USS Trenton

- The Voyage of a Lifetime

- The Ships of the Great White Fleet

- Great White Fleet Gallery

- Beginning of the Cruise

- Fleet Leadership

- Crossing the Equator

- World Cruise Experience

- Puerto Rico-South America-Mexico

- U.S. West Coast

- Hawaii-Australia-New Zealand

- Japan and China

- Philippines and Ceylon (Sri Lanka)

- Suez Canal-Egypt-Turkey

- Mediterranean

- End of the Cruise

- Memorabilia

- Apollo 10 and NASA

- Gemini 9 and NASA

- Gemini 10 and NASA

- Apollo 7 and NASA

- Apollo 8 and NASA

- Apollo 12 and NASA

- Polar Exploration

- The First U.S. Naval Observatory

- Bathyscaphe Trieste

- Airships & Dirigibles

- Higgins Boats

- Navy’s Use of Torpedoes

- The Nuclear Navy

- Radar and Sonar

- Navy’s Use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

- Naval Mine Warfare

- The Navy’s Use of Carrier Pigeons

- The U.S. Navy and the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95

- The Steel Navy

- Lieutenant John F. Kennedy, USNR

- Commander Lyndon B. Johnson, USNR

- Commander Richard M. Nixon, USNR

- Lieutenant Commander Gerald R. Ford, USNR

- Lieutenant James Earl Carter Jr., USN

- Lieutenant George H. W. Bush, USNR

- Admiral William S. Benson

- Admiral Robert E. Coontz

- Admiral Edward W. Eberle

- Admiral Charles F. Hughes

- Admiral William V. Pratt

- Admiral William H. Standley

- Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy

- Admiral Harold R. Stark

- Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King

- Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz

- Admiral Louis E. Denfeld

- Admiral Forrest P. Sherman

- Admiral William M. Fechteler

- Admiral Robert B. Carney

- Admiral Arleigh A. Burke

- Admiral George W. Anderson Jr.

- Admiral David L. McDonald

- Admiral Thomas H. Moorer

- Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt Jr.

- Admiral James L. Holloway III

- Admiral Thomas B. Hayward

- Admiral James D. Watkins

- Admiral Carlisle A. H. Trost

- Admiral Frank B. Kelso II

- Admiral Jeremy M. Boorda

- Admiral Jay L. Johnson

- Admiral Vernon E. Clark

- Admiral Michael G. Mullen

- Admiral Gary Roughead

- Admiral Jonathan W. Greenert

- Admiral John M. Richardson

- Admiral Michael Gilday

- MCPON Delbert D. Black

- MCPON John D. Whittet

- MCPON Robert J. Walker

- MCPON Thomas S. Crow

- MCPON Billy C. Sanders

- MCPON William H. Plackett

- MCPON Duane R. Bushey

- MCPON John Hagan

- MCPON James L. Herdt

- MCPON Terry D. Scott

- MCPON Joe R. Campa Jr.

- MCPON Rick D. West

- MCPON Michael D. Stevens

- MCPON Steven S. Giordano

- MCPON Russell L. Smith

- MCPON James M. Honea

- MCPON Official Photographs

- John Paul Jones

- Oliver Hazard Perry

- Joshua Barney

- David Glasgow Farragut

- Esek Hopkins

- Stephen Decatur

- John A. Dahlgren

- Robert Field Stockton

- Benjamin Stoddert (1798 - 1801)

- Robert Smith (1801 - 1809)

- Paul Hamilton (1809 - 1812)

- William Jones (1813 - 1814)

- Benjamin W. Crowninshield (1815 - 1818)

- Smith Thompson (1819 - 1823)

- Samuel Southard (1823 - 1829)

- John Branch, Jr. (1829 - 1831)

- Levi Woodbury (1831 - 1834)

- Mahlon Dickerson (1834 - 1838)

- James K. Paulding (1838 - 1841)

- George Edmund Badger (1841)

- Abel P. Upshur (1841 - 1843)

- David Henshaw (1843 - 1844)

- Thomas W. Gilmer (1844)

- John Y. Mason (1844-1845) (1846-1849)

- George Bancroft (1845 - 1846)

- William B. Preston (1849 - 1850)

- William A. Graham (1850 - 1852)

- John P. Kennedy (1852 - 1853)

- James C. Dobbin (1853 - 1857)

- Isaac Toucey (1857 - 1861)

- Gideon Welles (1861 - 1869)

- Adolph Edward Borie (1869)

- George M. Robeson (1869 - 1877)

- Richard W. Thompson (1877 - 1880)

- Nathan Goff, Jr. (1881)

- William Henry Hunt (1881 - 1882)

- William Eaton Chandler (1882 - 1885)

- William C. Whitney (1885 - 1889)

- Benjamin F. Tracy (1889 - 1893)

- Hilary A. Herbert (1893 - 1897)

- John D. Long (1897 - 1902)

- William H. Moody (1902 - 1904)

- Paul Morton (1904 - 1905)

- Charles J. Bonaparte (1905 - 1906)

- Victor H. Metcalf (1906 - 1908)

- Truman H. Newberry (1908 - 1909)

- George von L. Meyer (1909 - 1913)

- Josephus Daniels (1913 - 1921)

- Edwin Denby (1921 - 1924)

- Charles F. Adams, III (1929 - 1933)

- Claude A. Swanson (1933 - 1939)

- Charles Edison (1940)

- William Franklin Knox (1940 - 1944)

- James Forrestal (1944 - 1947)

- John Lawrence Sullivan (1947 - 1949)

- Francis P. Matthews (1949 - 1951)

- Dan A. Kimball (1951 - 1953)

- Robert B. Anderson (1953 - 1954)

- Charles S. Thomas (1954 - 1957)

- Thomas S. Gates (1957 - 1959)

- William Birrell Franke (1959 - 1961)

- John Bowden Connally, Jr. (1961)

- Fred Korth (1962 - 1963)

- Paul B. Fay (acting) (1963)

- Paul Henry Nitze (1963 - 1967)

- Charles Fitz Baird (acting) (1967)

- Paul R. Ignatius (1967 - 1969)

- John Hubbard Chafee (1969 - 1972)

- John William Warner (1972 - 1974)

- J. William Middendorf (1974 - 1977)

- William Graham Claytor, Jr. (1977 - 1979)

- Edward Hidalgo (1979 - 1981)

- John Lehman (1981 - 1987)

- James H. Webb (1987 - 1988)

- William L. Ball (1988 - 1989)

- Henry L. Garrett III (1989 - 1992)

- Daniel Howard (acting) (1992)

- Sean Charles O'Keefe (1992 - 1993)

- ADM Frank B. Kelso, II (acting) (1993)

- John Howard Dalton (1993 - 1998)

- Richard Jeffrey Danzig (1998 - 2001)

- Robert B. Pirie, Jr. (acting) (2001)

- Gordon R. England (2001-2003) (2003-2005)

- Susan M. Livingstone (acting) (2003)

- Hansford T. Johnson (acting) (2003)

- Donald Charles Winter (2006 - 2009)

- Raymond Edwin Mabus, Jr. (2009 - 2017)

- Sean G. J. Stackley (acting) (2017)

- Richard V. Spencer (2017 - 2019)

- Thomas B. Modly (acting) (2019-2020)

- James E. McPherson (acting) (2020)

- Kenneth J. Braithwaite (2020-2021)

- Thomas W. Harker (acting) (2021)

- Carlos Del Toro (2021-present)

- Medal of Honor Recipients

- Sergeant Cornelius H. Charlton

- Private First Class Oscar P. Austin

- Civil Rights Activist Medgar Evers

- Private George Watson

- Cook First Class William Pinckney

- Commander Mary Sears

- Rear Admiral Grace Hopper

- Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt

- Senator Daniel K. Inouye

- Private First Class Herbert K. Pililaau

- Sergeant First Class Rodney J.T. Yano

- First Lieutenant Baldomero Lopez

- Master Sergeant Roy Benavidez

- Civil Rights Activist Cesar Chavez

- Admiral David Glasgow Farragut

- Private First Class Fernando Garcia

- Sergeant Alfredo Gonzalez

- Sergeant Rafael Peralta

- Chief Petty Officer James E. Williams

- Guide and Interpreter Sacagawea

- Sergeant Darrell Samuel Cole

- Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee

- Captain Thomas J. Hudner, Jr.

- Agnes Driscoll

- Frigate Chesapeake

- Frigate Congress

- Frigate Constellation

- Frigate Constitution

- Frigate President

- Frigate United States

- Bonhomme Richard

- U.S. Navy Brig Somers

- CSS Alabama

- Conestoga (S.P. 1128)

- USS Cumberland and CSS Florida

- Maine (Second-class Battleship)

- Memphis (Armored Cruiser No. 10)

- San Diego (Armored Cruiser No. 6)

- Tecumseh (monitor)

- Alchiba (AK-23)

- Arizona (BB-39)

- Cole (DDG-67)

- Fletcher (DD-445)

- Harmon (DE-678)

- Houston (CA-30)

- Indianapolis (CA-35)

- Jacob Jones (DD-61)

- Johnston (DD-557)

- Maddox (DD-731)

- Missouri (BB-63)

- O'Bannon (DD-450)

- Pueblo (AGER-2)

- Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58)

- San Diego (CL-53)

- San Francisco (CA-38)

- Tripoli (LPH-10)

- Turner Joy (DD-951)

- Washington (BB-56)

- Belleau Wood (CVL-24)

- Enterprise (CV-6)

- Enterprise (CVN-65)

- Essex (CV-9)

- Forrestal (CVA-59)

- Franklin (CV-13)

- Hornet (CV-8)

- Intrepid (CV-11)

- John F. Kennedy (CVA-67)

- Langley (CV-1)

- Lexington (CV-2)

- Midway (CVB-41)

- Ranger (CV-4)

- Saratoga (CV-3)

- Wasp (CV-7)

- Yorktown (CV-5)

- Barb (SS-220)

- Finback (SS-230)

- George Washington (SSBN-598)

- Growler (SS-215)

- H. L. Hunley

- Nautilus (SSN-571)

- Rasher (SS-269)

- Scorpion (SSN-589)

- Sculpin (SS-191)

- Silversides (SS-236)

- Swordfish (SS-193)

- Tang (SS-306)

- Tautog (SS-199)

- Thresher (SSN-593)

- Triton (SSR(N)-586)

- Wahoo (SS-238)

- People-Places-Things--Russian

- Historical Summary

- Navy Leadership

- Image (gif, jpg, tiff)

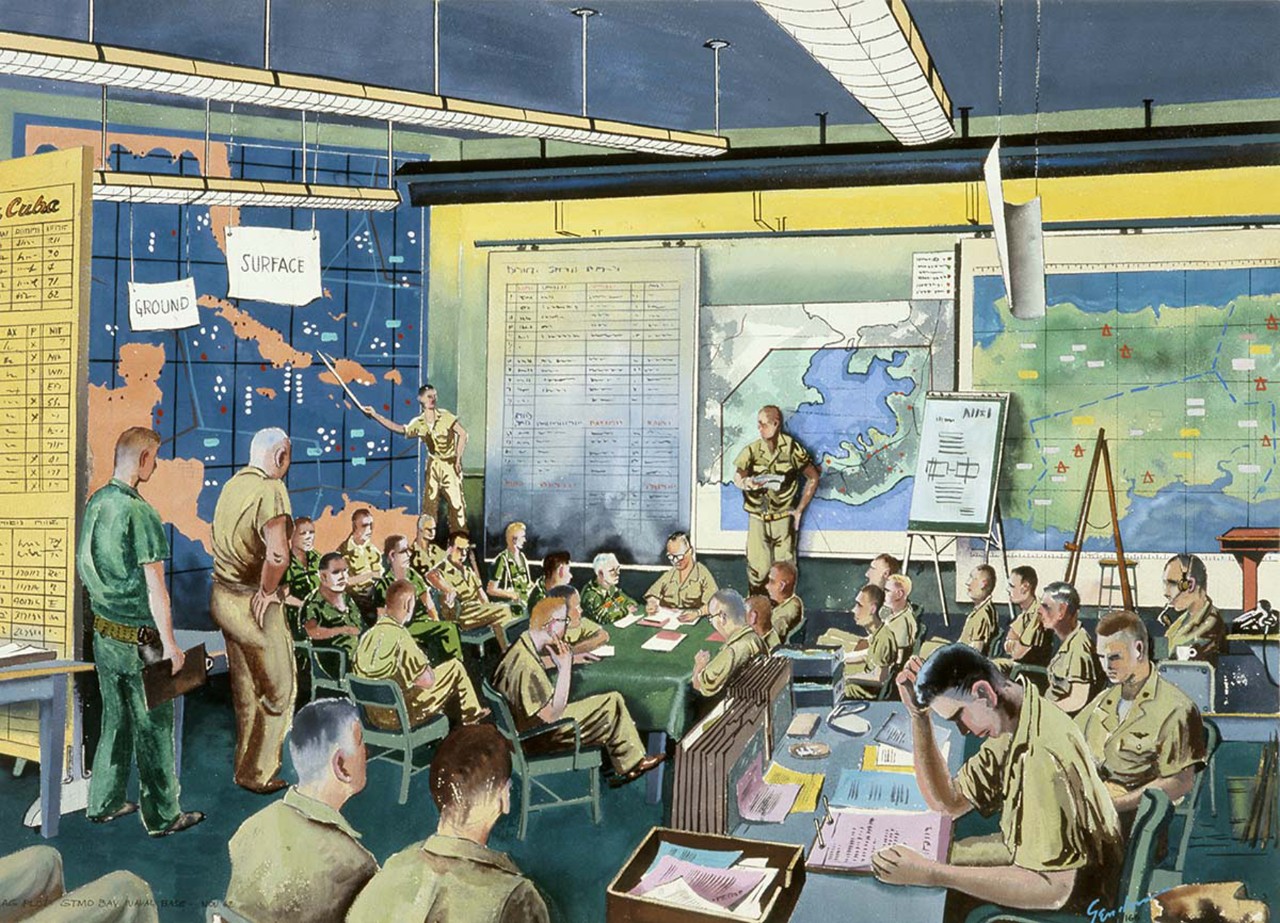

In the fall of 1962, the Soviet Union began construction on ballistic missile launch sites in Cuba. The United States responded with a naval blockade. For thirteen days, the fear of impending nuclear war continued until an agreement was reached for the removal of the weapons. Painting, watercolor on paper; by Richard Genders; 1962; unframed dimensions 20H X 28W. Accession#: 88-190-BT.

In the fall of 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union came as close as they ever would to global nuclear war. Hoping to correct what he saw as a strategic imbalance with the United States, Soviet Premier Nikita S. Khrushchev began secretly deploying medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles to Fidel Castro's Cuba. Once operational, these nuclear-armed weapons could have been used on cities and military targets in most of the continental United States. Before this happened, however, U.S. intelligence discovered Khrushchev's brash maneuver. In what became known as the Cuban Missile Crisis, President John F. Kennedy and an alerted and aroused American government, military, and public compelled the Soviets to remove not only their missiles, but also all of their offensive weapons, from Cuba.

The U.S. Navy played a pivotal role in this crisis, demonstrating the critical importance of naval forces to the national defense. The Navy, in cooperation with the other U.S. armed forces and allies, strategically employed military power in such a way that the President did not have to resort to war to protect vital Western interests. Khrushchev realized that his missile and bomber forces were no match for the Navy's powerful Polaris missile-firing submarines and the Air Force's land-based nuclear delivery systems once they became fully operational. Naval forces under the U.S. Atlantic Command, headed by Admiral Robert L. Dennison , steamed out to sea, intercepting both merchant shipping enroute to Cuba and Soviet submarines operating in the area. U.S. destroyers and frigates, kept on station through underway replenishment by oilers and stores ships, maintained a month-long naval quarantine of the island. Radar picket ships, supported by Navy fighters and airborne early warning planes, assisted the Air Force's Air Defense Command in preparing to defend American airspace from Soviet and Cuban forces. Playing a vital role, Navy aerial photographic and patrol aircraft observed the deployment of Soviet offensive weapons into Cuba (and eventually monitored their withdrawal by sea).

As the unified commander for the Caribbean, Dennison was responsible for readying Army, Air Force, Marine, and Navy assault forces for a possible invasion of Cuba. He also served as the Commander in Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet. The aircraft carriers, destroyers, and Marine forces of the subordinate Second Fleet, under Vice Admiral Alfred G. Ward , were poised to launch air, naval gunfire, and amphibious strikes from the sea against Soviet and Cuban forces ashore. With speed and efficiency, other fleet units reinforced the Marine garrison at Guantanamo on Cuba's southeastern tip and evacuated American civilians. Dennison also coordinated the maritime support operations carried out by Canadian, British, Argentine, and Venezuelan forces.

Khrushchev, faced with the armed might of the United States and its allies, had little choice but to find some way out of the difficult situation in which he had placed himself and his country. President Kennedy did not press the advantage that the strength of U.S. and allied naval and military forces gave him. Thus, the Soviet leader was able to peacefully disengage his nation from this most serious of Cold War confrontations.

Suggested Reading

- Online Reading Room: Cuban Missile Crisis

- CIA Documents on the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume XI, Cuban Missile Crisis and Aftermath

- Department of State: The Cuban Missile Crisis, October 1962

- National Security Archive: The Cuban Missile Crisis

- U.S. Navy Ships and Units Which Received the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal for Participating in the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962

- John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum: Cuban Missile Crisis

- Department of Defense Cuban Missile Crisis Briefing Materials

- The Naval Quarantine of Cuba, 1962

- The Naval Quarantine of Cuba, 1962: Quarantine, 22–26 October

- A New Look at the Cuban Missile Crisis

- “Cordon of Steel: The U.S. Navy and the Cuban Missile Crisis” by Curtis A. Utz (5.6 MB pdf download)

- “More Bang for the Buck:” U.S. Nuclear Strategy and Missile Development 1945–1965

- Cuban Missile Crisis: U.S. Naval Aviation Operations (29 KB pdf download)

Selected Imagery

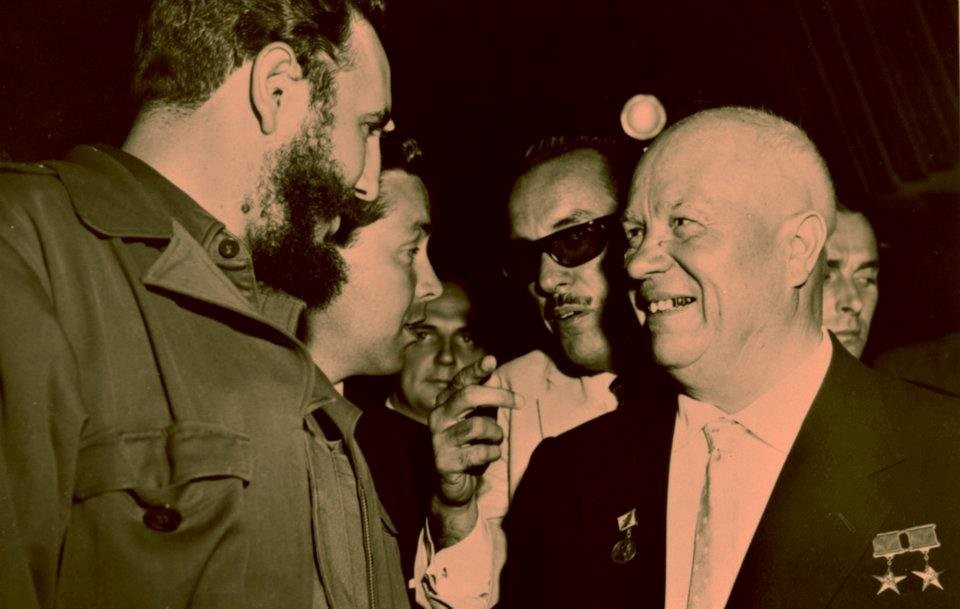

Cuban leader Fidel Castro, left, meets with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev at the United Nation in New York, September 1960. (National Archives photograph 306-PS-60-16402)

Low altitude reconnaissance photograph of medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) launch site number 1 in San Cristobal, Cuba showing missile shelter tents, launch pad, transporters, and other equipment. United States. Department of Defense. Department of Defense Cuban Missile Crisis Briefing Materials. (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. Accession Number: PX66-20:16)

Photographers and cameramen swarm President Kennedy at his desk in the Oval Office upon signing the Cuba Quarantine order, 23 October 1962. (National Archives identifier: 6817196)

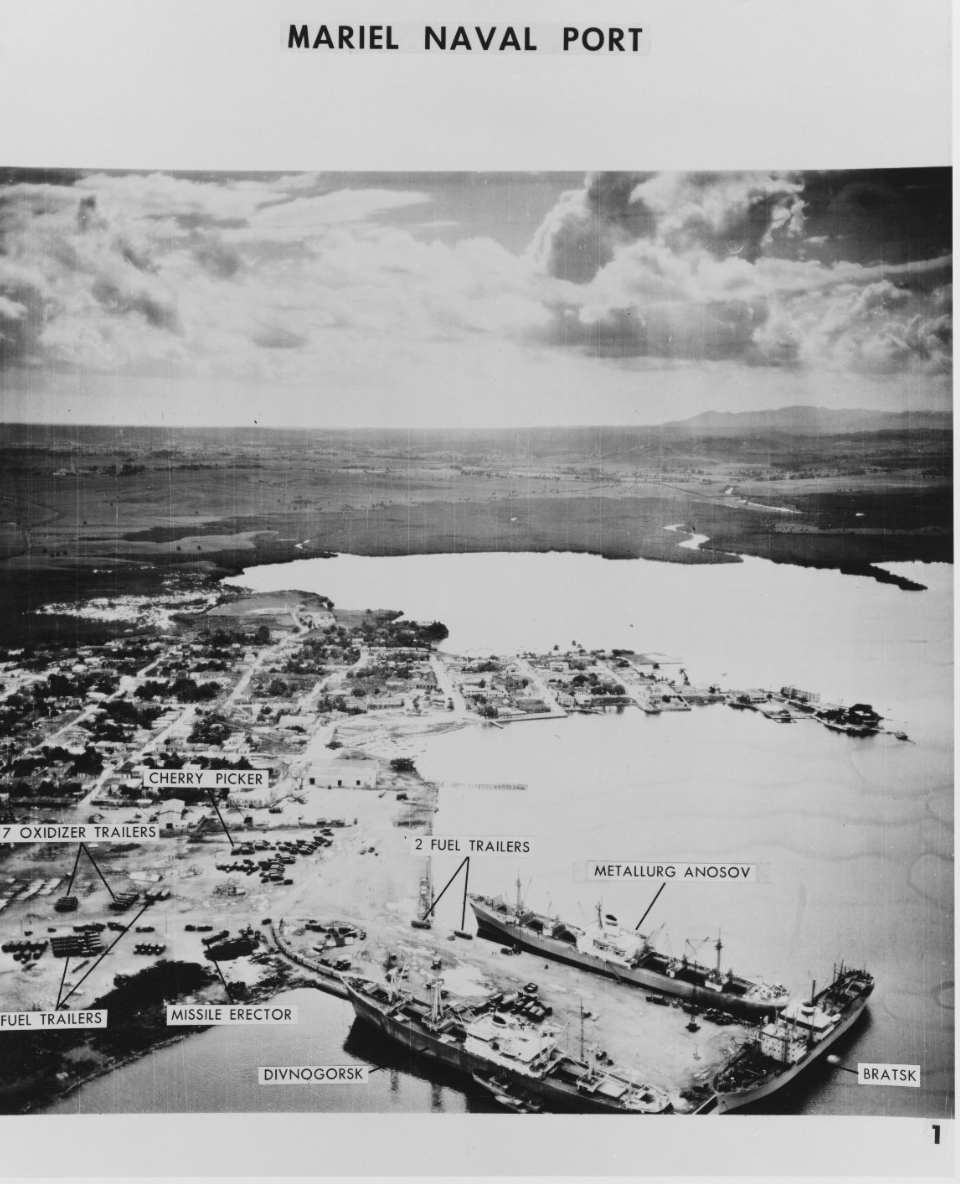

Cuban Missile Crisis. Low-level aerial photograph of Mariel Naval port, Cuba, taken 2 November 1962, showing missile support equipment at the port being prepared for loading on Soviet ships for removal from Cuba. Soviet ships present are Divnogorsk , Bratsk , and Metallurg Anosov . (National Archives. Catalog#: USN 711210)

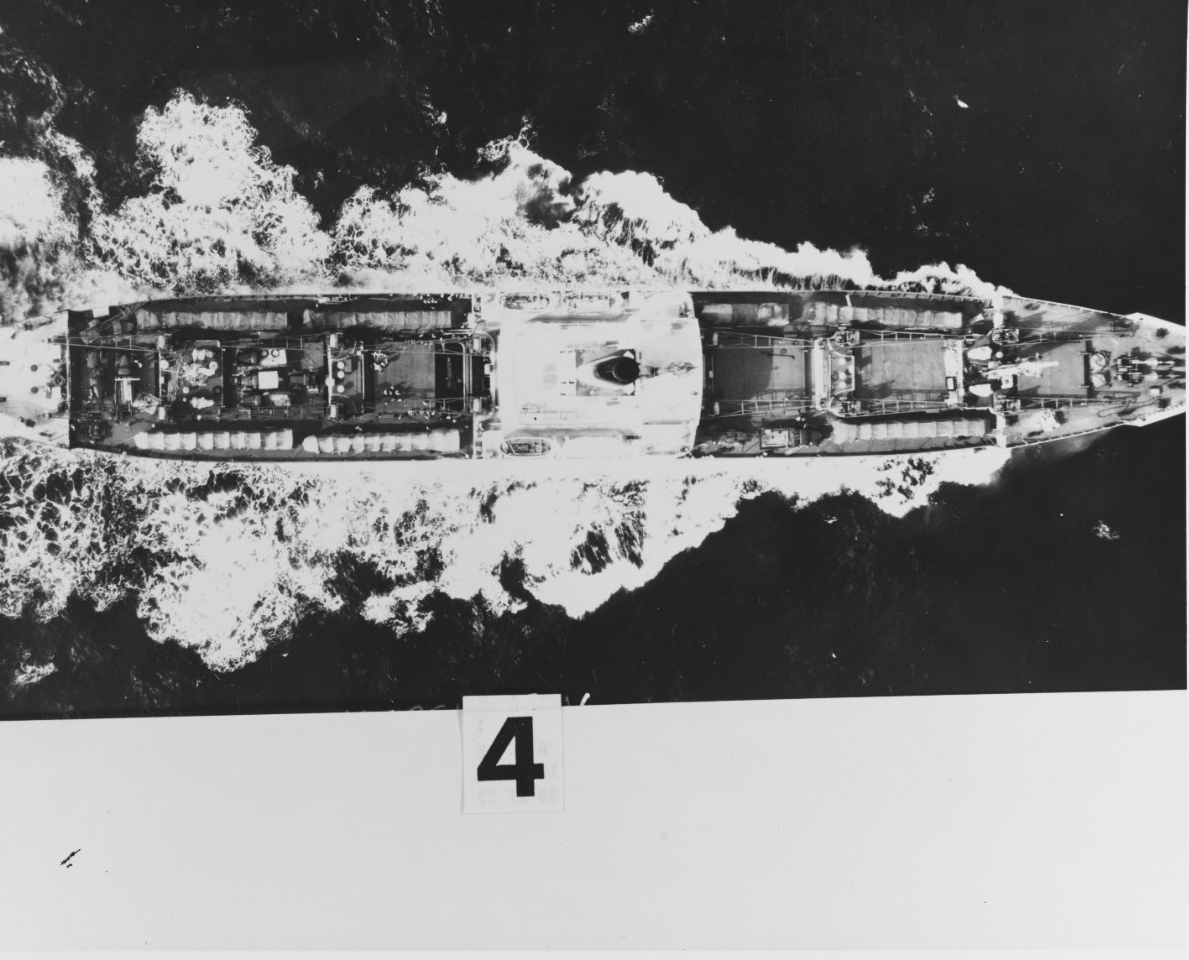

Cuban Missile Crisis. Soviet freighter Fizik Kurchatov at sea, 7 November 1962, just after leaving Cuba to return six missiles to the USSR. (National Archives. Catalog#: USN 711208)

Cuban Missile Crisis. Soviet freighter Volgoles carrying missiles away from Cuba on 9 November 1962. USS Vesole (DDR-878) is alongside. The wingtip of the photo plane, SP-2 Neptune, is also visible. (National Archives. Catalog#: USN 711204)

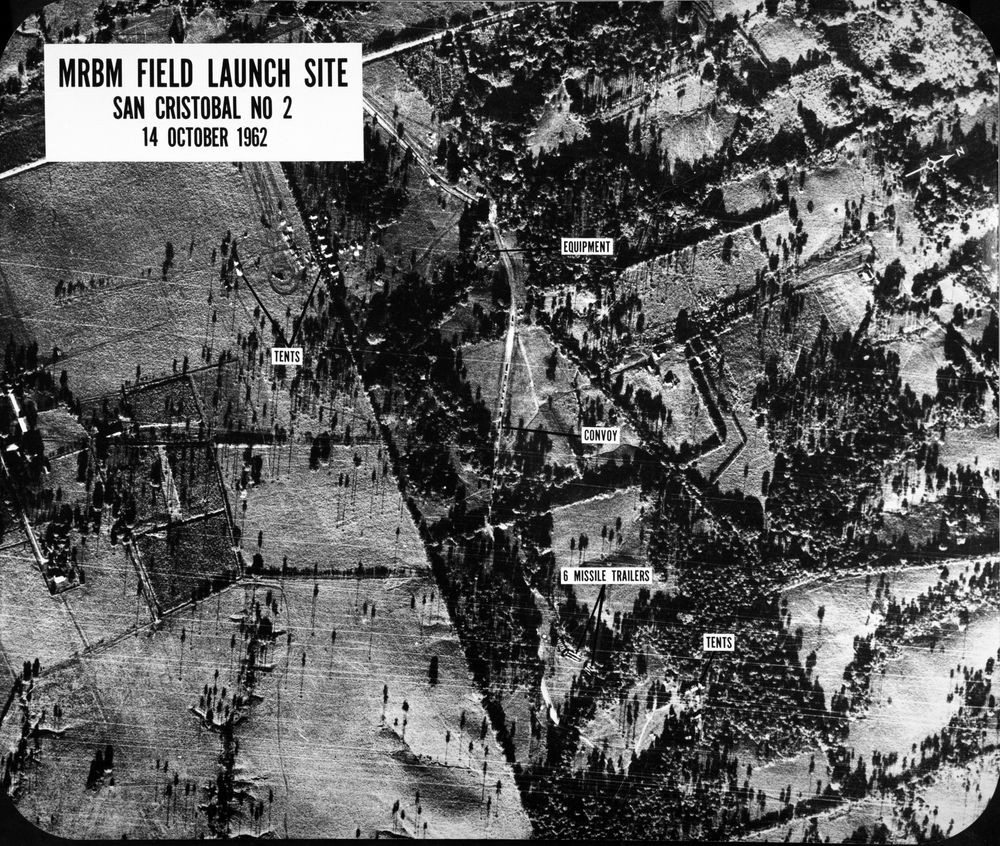

High altitude aerial reconnaissance photograph of medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) launch site number 2 in San Cristobal, Cuba, 14 October 1962. United States. Department of Defense. Department of Defense Cuban Missile Crisis Briefing Materials. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. (Accession number: PX66-20:8)

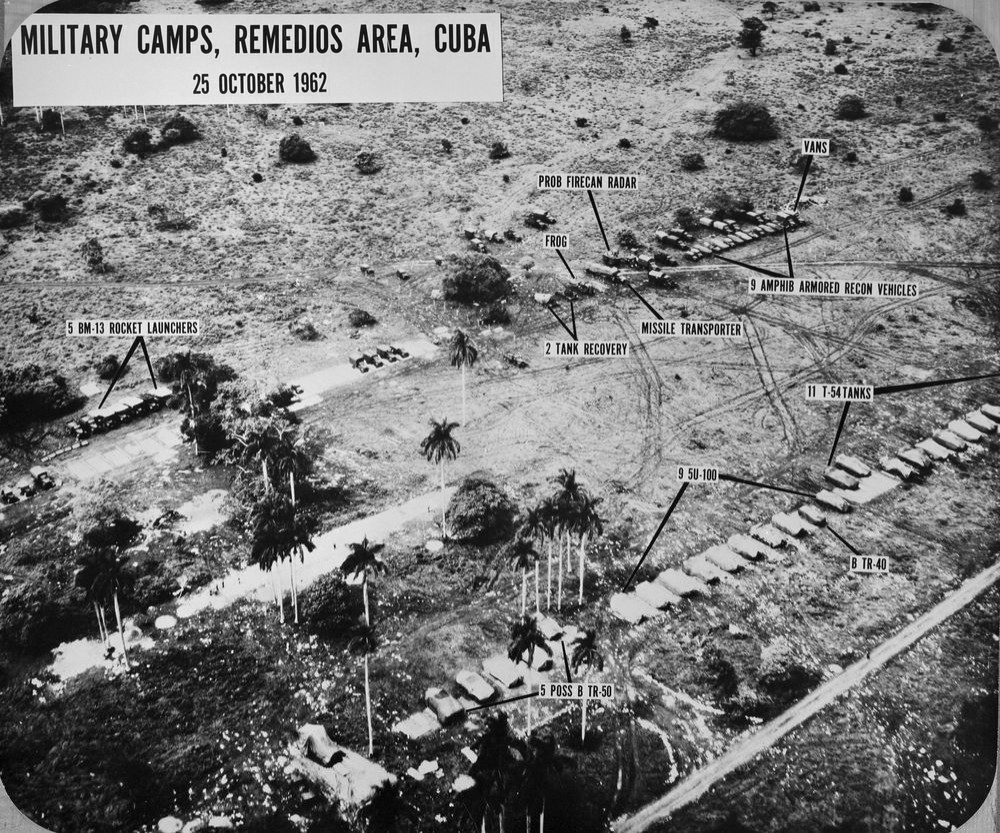

Low altitude aerial photograph made over a portion of the Remedios-area military camp in Cuba on 25 October 1962, showing a Soviet FROG missile with transporter and launcher, 130mm rocket launchers, SU-100 assault guns, T-54 tanks, and other weapons, vehicles, and associated equipment. United States. Department of Defense. Department of Defense Cuban Missile Crisis Briefing Materials. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. Accession Number: PX66-20:82.