What You Need to Know About the Book Bans Sweeping the US

What you need to know about the book bans sweeping the u.s., as school leaders pull more books off library shelves and curriculum lists amid a fraught culture war, we explore the impact, legal landscape and history of book censorship in schools..

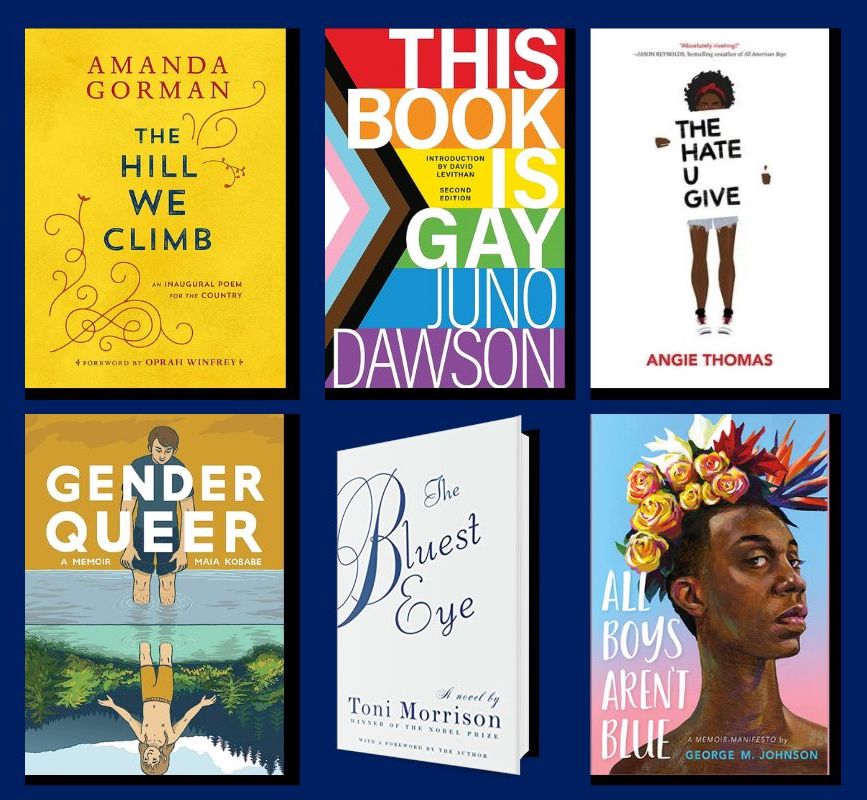

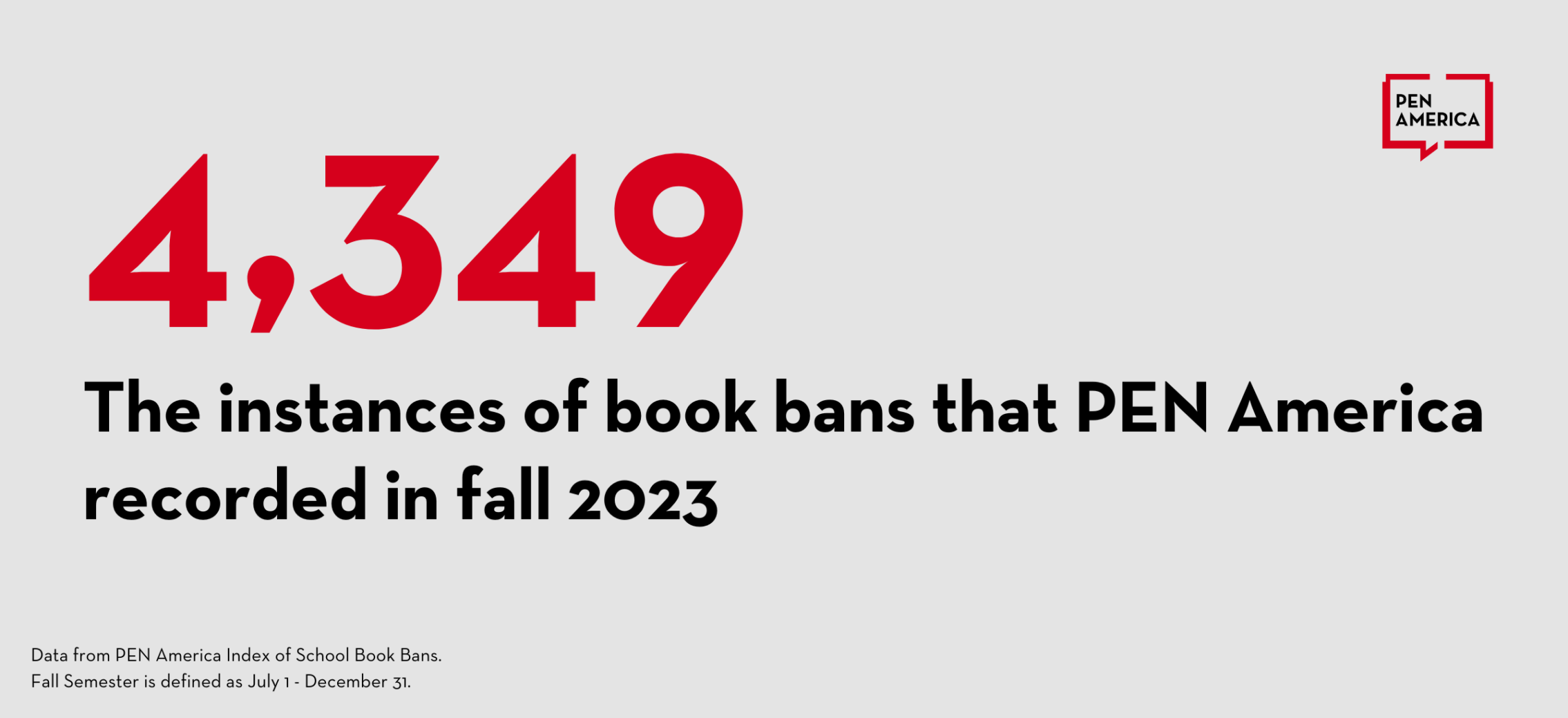

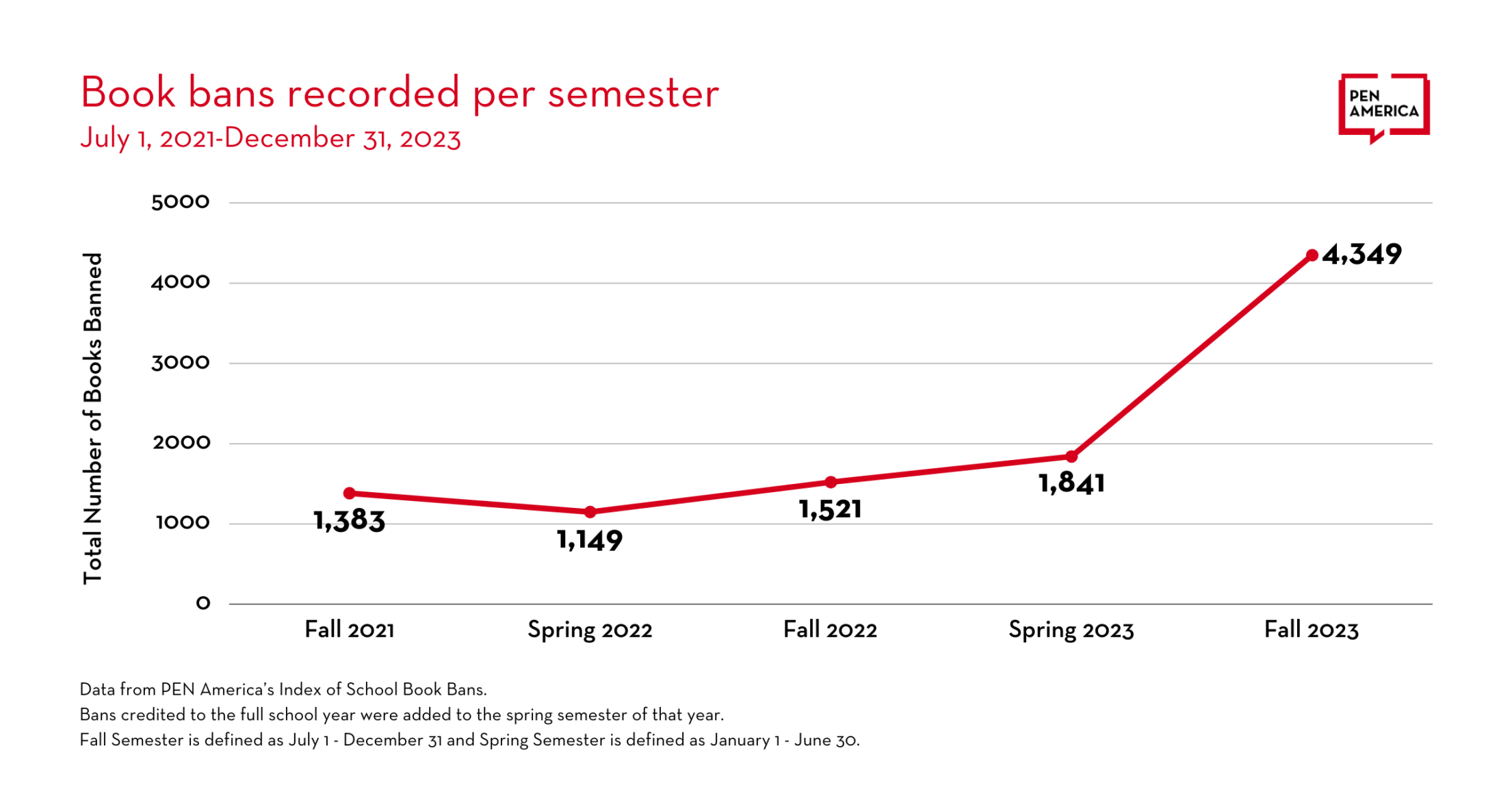

- The American Library Association reported a record-breaking number of attempts to ban books in 2022— up 38 percent from the previous year. Most of the books pulled off shelves are “written by or about members of the LGBTQ+ community and people of color."

- U.S. school boards have broad discretion to control the material disseminated in their classrooms and libraries. Legal precedent as to how the First Amendment should be considered remains vague, with the Supreme Court last ruling on the issue in 1982.

- Battles to censor materials over social justice issues pose numerous implications for education while also mirroring other politically-motivated acts of censorship throughout history.

Here are all of your questions about book bans answered by TC experts.

Alex Eble, Assistant Professor of Economics and Education; Sonya Douglass, Professor of Education Leadership; Michael Rebell, Professor of Law and Educational Practice; and Ansley Erickson, Associate Professor of History and Education Policy. (Photos; TC Archives)

How Do Book Bans Impact Students?

Prior to the rise in bans, white male youth were already more likely to see themselves depicted in children’s books than their peers, despite research demonstrating how more culturally inclusive material can uplift all children, according to a study, forthcoming in the Quarterly Journal of Economics , from TC’s Alex Eble.

“Books can change outcomes for students themselves when they see people who look like them represented,” explains the Associate Professor of Economics and Education. “What people see affects who they become, what they believe about themselves and also what they believe about others…Not having equitable representation robs people of seeing the full wealth of the future that we all can inhabit.”

While books have stood in the crossfire of political battles throughout history, today’s most banned books address issues related to race, gender identity and sexuality — major flashpoints in the ongoing American culture war. But beyond limiting the scope of how students see themselves and their peers, what are the risks of limiting information access?

The student plaintiffs in Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982) march in protest of the Long Island school district's removal of titles such as Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut. While the district would ultimately return the banned books to its shelves, the Supreme Court's ultimate ruling largely allowed school leaders to maintain discretion over information access. (Photo credit: unknown)

“[Book bans] diminish the quality of education students have access to and restrict their exposure to important perspectives that form the fabric of a culturally pluralist society like the United States,” explains TC’s Sonya Douglas s, Professor of Education Leadership. “It's a battle over the soul of the country in many ways; it's about what we teach young people about our country, what we determine to be the truth, and what we believe should be included in the curriculum they're receiving. There's a lot at stake there.”

Material stripped from libraries and curriculum include works written by Black authors that discuss police brutality, the history of slavery in the U.S. and other issues. As such, Black students are among those who may be most affected by bans across the country, but — in Douglass’ view — this is simply one of the more recent disappointments in a long history of Black communities being let down by public education — chronicled in her 2020 book, and further supported by a 2021 study from Douglass’ Black Education Research Center that revealed how Black families lost trust in schools following the pandemic response and murder of George Floyd.

In that historical and cultural context — even as scholars like Douglass work to implement Black studies curriculums — the failure of schools to properly integrate Black experiences into the curriculum remains vast.

“We want to make sure that children learn the truth, and that we give them the capacity to handle truths that may be uncomfortable and difficult,” says Douglass, citing Germany as an example of a nation that has prioritized curriculum that highlights its own injustices, such as the Holocaust. “This moment again requires us to take stock of the fact that racism and bigotry still are a challenging part of American life. When we better understand that history, when we see the patterns, when we recognize the source of those issues, we can then do something about it.”

Beginning in 1933, members of Hitler Youth regularly burned books written by prominent Jewish, liberal, and leftist writers. (Photo: World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo, dated 1938)

Why Is Banning Books Legal?

While legal battles over book censorship in schools consistently unfold at local levels, the wave of book bans across the U.S. surfaces a critical question: why hasn’t the United States had more definitive legal closure on this issue?

In 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a noncommittal ruling that continues to keep school and library books in the political crosshairs more than 40 years later. In Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982), the Court deemed that “local school boards have broad discretion in the management of school affairs” and that discretion “must be exercised in a manner that comports with the transcendent imperatives of the First Amendment.”

But what does this mean in practice? In these kinds of cases, the application of the First Amendment hinges on the existence of evidence that books are banned for political reasons and violate freedom of expression. However, without more explicit guidance, school boards often make decisions that prioritize “community values” first and access to information second.

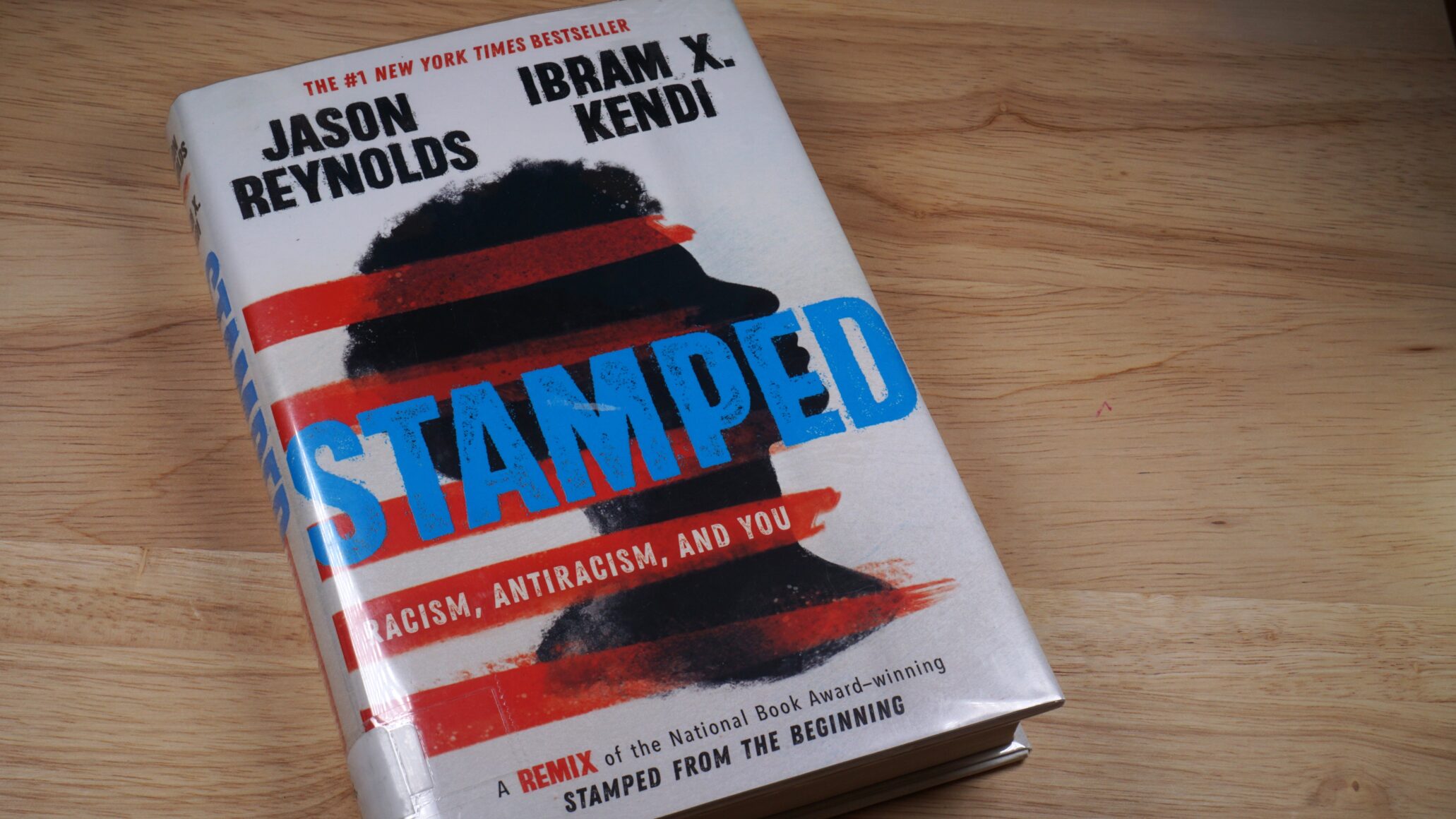

While today's recent book bans most frequently include topics related to racial justice and gender identity (pictured above), other frequently targeted titles include Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close , The Kite Runner and The Handmaid's Tale . (Cover images courtesy of: Viking Books, Sourcebooks Fire, Balzer + Bray, Oni Press, Random House and Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

“America traditionally has prided itself on local control of education — the fact that we have active citizen and parental involvement in school board issues, including curriculum,” explains TC’s Michael Rebell , Professor of Law and Educational Practice. “We have, whether you want to call it a clash or a balancing, of two legal considerations here: the ability of children to freely learn what they need to learn to be able to exercise their constitutional rights, and this traditional right of the school authorities to determine what the curriculum is.”

So would students benefit from more national and uniform legal guidance on book banning? In this political climate, Rebell attests, the risks very well might outweigh the potential rewards.

“Your local institutions are —in theory — protecting the values you believe in. And if somebody in Washington were going to say that we couldn't have books that talk about transgender rights and things in New York libraries, we'd go crazy, right?” said Rebell, who leads the Center for Educational Equity . “So I can't imagine that in this polarized environment, people would be in favor of federal law, whatever it said.”

Why Do Waves of Book Bans Keep Happening?

Historians date censorship back all the way to the earliest appearance of written materials. Ancient Chinese emperor Shih Huang Ti began eliminating historical texts in 259 B.C., and in 35 A.D., Roman emperor Caligula objected to the ideals of Greek freedom depicted in The Odyssey . In numerous waves of censorship since then, book bans have consistently manifested the struggle for political control.

“We have to think about [the current bans] as part of a longer pattern of fights over what is in curriculum and what is kept out of it,” explains TC’s Ansley Erickson , Associate Professor of History and Education Policy, who regularly prepares local teachers on how to integrate Harlem history into social studies curriculum.

“The United States’ history, since its inception, is full of uses of curriculum to shape politics, the economy and the culture,” says Erickson. “This is a really dramatic moment, but the curriculum has always been political, and people in power have always been using it to emphasize their power. And historically marginalized groups have always challenged that power.”

One example: when Latinx students were forbidden from speaking Spanish in their Southwest schools throughout the 20th century, they worked to maintain their traditions and culture at home.

“These bans really matter, but one of the ways we can imagine a response is by looking back at how people created spaces for what wasn’t given room for in the classroom,” Erickson says.

What Could Happen Next?

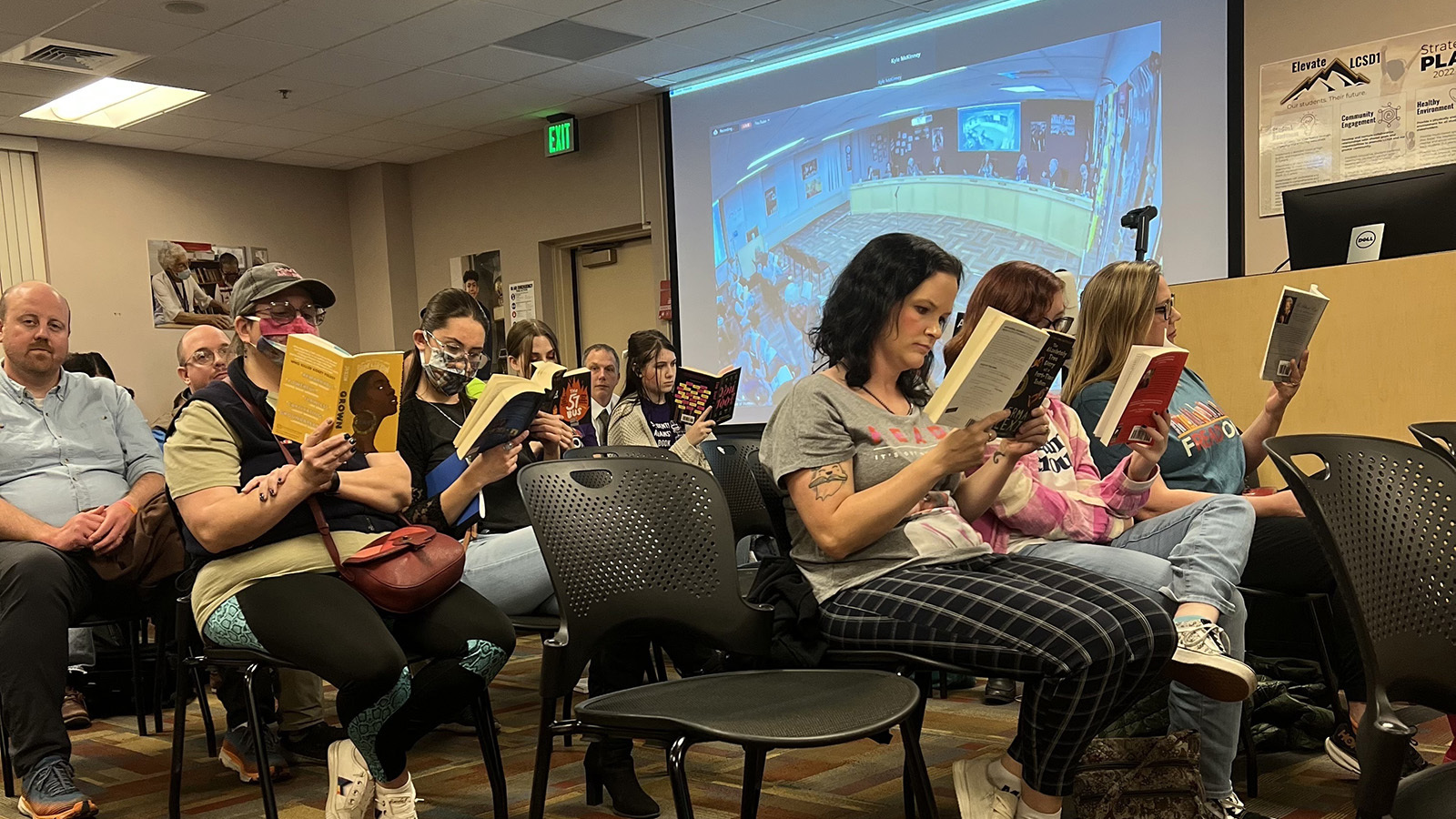

American schools stand at a critical inflection point, and amid this heated debate, Rebell sees civil discourse at school board meetings as a paramount starting point for any sort of resolution. “This mounting crisis can serve as a motivator to bring people together to try to deal with our differences in respectful ways and to see how much common ground can be found on the importance of exposing all of our students to a broad range of ideas and experiences,” says Rebell. “Carve-outs can also be found for allowing parents who feel really strongly that certain content is inconsistent with their religious or other values to exempt their children from certain content without limiting the options for other children.”

But students, families and educators also have the opportunity to speak out, explains Douglass, who expressed concern for how her own daughter is affected by book bans.

“I’d like to see a groundswell movement to reclaim the nation's commitment to education — to recognize that we're experiencing growing pains and changes in terms of what we stand for; and whether or not we want to live up to the democratic ideal of freedom of speech; different ideas in the marketplace, and a commitment to civics education and political participation,” says Douglass.

As publishers and librarians file lawsuits to push back, students are also mobilizing to protest bans — from Texas to western New York and elsewhere. But as more local battles unfold, bigger issues remain unsolved.

“We need to have a conversation as a nation about healing; about being able to confront the past; about receiving an apology and beginning that process of reconciliation,” says Douglass. “Until we tackle that head on, we'll continue to have these types of battles.”

— Morgan Gilbard

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the speaker to whom they are attributed. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the faculty, administration, staff or Trustees either of Teachers College or of Columbia University.

Tags: Views on the News Education Policy K-12 Education Social Justice

Programs: Economics and Education Education Leadership History and Education

Departments: Education Policy & Social Analysis

Published Wednesday, Sep 6, 2023

Teachers College Newsroom

Address: Institutional Advancement 193-197 Grace Dodge Hall

Box: 306 Phone: (212) 678-3231 Email: views@tc.columbia.edu

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Browse content in Biological, Health, and Medical Sciences

- Administration Of Health Services, Education, and Research

- Agricultural Sciences

- Allied Health Professions

- Anesthesiology

- Anthropology

- Anthropology (Biological, Health, and Medical Sciences)

- Applied Biological Sciences

- Biochemistry

- Biophysics and Computational Biology (Biological, Health, and Medical Sciences)

- Biostatistics

- Cell Biology

- Dermatology

- Developmental Biology

- Emergency Medicine

- Environmental Sciences (Biological, Health, and Medical Sciences)

- Immunology and Inflammation

- Internal Medicine

- Medical Sciences

- Medical Microbiology

- Microbiology

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Ophthalmology

- Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine

- Plant Biology

- Population Biology

- Psychological and Cognitive Sciences (Biological, Health, and Medical Sciences)

- Public Health and Epidemiology

- Radiation Oncology

- Rehabilitation

- Sustainability Science (Biological, Health, and Medical Sciences)

- Systems Biology

- Veterinary Medicine

- Browse content in Physical Sciences and Engineering

- Aerospace Engineering

- Applied Mathematics

- Applied Physical Sciences

- Bioengineering

- Biophysics and Computational Biology (Physical Sciences and Engineering)

- Chemical Engineering

- Civil and Environmental Engineering

- Computer Sciences

- Computer Science and Engineering

- Earth Resources Engineering

- Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences

- Electric Power and Energy Systems Engineering

- Electronics, Communications and Information Systems Engineering

- Engineering

- Environmental Sciences (Physical Sciences and Engineering)

- Materials Engineering

- Mathematics

- Mechanical Engineering

- Sustainability Science (Physical Sciences and Engineering)

- Browse content in Social and Political Sciences

- Anthropology (Social and Political Sciences)

- Economic Sciences

- Environmental Sciences (Social and Political Sciences)

- Political Sciences

- Psychological and Cognitive Sciences (Social and Political Sciences)

- Social Sciences

- Sustainability Science (Social and Political Sciences)

- Author guidelines

- Submission site

- Open access policy

- Self-archiving policy

- Why submit to PNAS Nexus

- The PNAS portfolio

- For reviewers

- About PNAS Nexus

- About National Academy of Sciences

- Editorial Board

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, materials and methods, acknowledgments, supplementary material, author contributions, data availability.

- < Previous

Book bans in political context: Evidence from US schools

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Competing Interest: The authors declare no competing interest.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Marcelo S O Goncalves, Isabelle Langrock, Jack LaViolette, Katie Spoon, Book bans in political context: Evidence from US schools, PNAS Nexus , Volume 3, Issue 6, June 2024, pgae197, https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae197

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In the 2021–2022 school year, more books were banned in US school districts than in any previous year. Book banning and other forms of information censorship have serious implications for democratic processes, and censorship has become a central theme of partisan political rhetoric in the United States. However, there is little empirical work on the exact content, predictors of, and repercussions of this rise in book bans. Using a comprehensive dataset of 2,532 bans that occurred during the 2021–2022 school year from PEN America, combined with county-level administrative data, multiple book-level digital trace datasets, restricted-use book sales data, and a new crowd-sourced dataset of author demographic information, we find that (i) banned books are disproportionately written by people of color and feature characters of color, both fictional and historical, in children's books; (ii) right-leaning counties that have become less conservative over time are more likely to ban books than neighboring counties; and (iii) national and state levels of interest in books are largely unaffected after they are banned. Together, these results suggest that rather than serving primarily as a censorship tactic, book banning in this recent US context, targeted at low-interest children's books featuring diverse characters, is more similar to symbolic political action to galvanize shrinking voting blocs.

Book banning is increasingly common in US schools. While most studies focus on centralized, state-sponsored censorship, individuals such as parents and local organizations have participated in this recent wave of banning. Our study empirically describes banned books and authors, finding high rates of children's books written by authors of color among banned books. Furthermore, we analyze the local contexts that predict bans and evaluate how interest changes after books are banned. In sum, we suggest that this wave of book bans is best understood as a form of political action in increasingly contested local contexts rather than as a means of effective censorship. These findings contribute to scholarship on social movements, polarization, and censorship in contemporary democracies.

While a quintessential signifier of censorship and intellectual suppression, book banning is not a foreign practice to the American public ( 1 ). United States schools and libraries have banned books with some regularity for the past two centuries, as traditional norms were challenged by modernist and scientific thought ( 2 , 3 ). However, the 2021–2022 school year saw a drastic increase in book bans across the country, often through mandates from school boards and parent complaints ( 4 , 5 ). Following the 2020 murder of George Floyd and the intensification of a partisan “culture war” ( 6 , 7 ), book bans have become central to a broader conversation around politics, civics, and identity.

Journalists have diligently documented the recent rise in book bans, particularly noting how bans directed against profanity, violence, and sexual content target books with LGBTQ+ and Black characters ( 8–11 ). While there are cases, most notably around the work of Mark Twain, where books are removed from the curriculum or annotated to note the historical context, the vast majority of bans follow larger debates about the inclusion of critical race theory ( 12 ), LGBTQ+ perspectives, and inclusive gender theory ( 13 , 14 ) in school curriculums. To proponents of bans, exposure to books that convey these theories is a form of indoctrinating students, such that bans protect children from inappropriate content ( 15 ). By contrast, opponents describe bans as questionably legal attempts to deny young people access to information about the reality of systematic race- and gender-based discrimination in US public institutions and to vital social representations affirming a wide range of experiences and identities ( 16 , 17 ). Bans seemingly censor particular identities exactly at the time that students begin to explore their own.

Academic research on contemporary book banning in the United States is scant but growing. Legal scholars have identified the contradictions between students’ First Amendment rights and censorship attempts ( 17 , 18 ), while library science scholars have described recent book bans as a revival of McCarthyism, diminishing intellectual freedom and a sign of increasing precarity for public libraries and schools ( 4 , 19 ). Education scholars find little evidence that bans protect children ( 20 ) and further argue that bans, in infringing upon children's human rights and their ability to access information, are likely to hinder the development of critical thinking skills ( 16 ).

Outside of book bans, much of our understanding of contemporary information censorship comes from the study of authoritarian actors and online environments, where states take a variety of measures to suppress oppositional information ( 21–24 ). Yet unlike state-sponsored forms of information suppression, book bans in the United States exist within a framework of participatory democracy. Bans are supported by complex and often opaque collaborations between local parent organizations and national political organizations such Moms for Liberty, with close ties to the Republican Party ( 25 ) and are adjudicated through the democratic operations of school boards. As book bans are dispersed across the country, what are the motivating factors uniting them? To what extent are they predictable, both politically and in regards to the content they target?

Our study answers these questions through a systematic analysis of 2,532 book bans that occurred in the United States during the 2021–2022 school year ( 26 ) that we annotate and substantially extend with administrative data, multiple digital trace datasets, restricted-use book sales data, and a new crowd-sourced dataset. These multifaceted data allow us to empirically assess the full spectrum of content being banned—the majority of which, we show, is written by women and people of color and features characters of color, both fictional and historical—but that otherwise does not neatly align with the descriptions of gratuitous sexual content or dogmatic texts on race and gender theory. We also assess the heterogeneity of socio-political contexts in which book bans occur, a level of detail crucial to understanding book bans as a form of collective action embedded within multiple layers of social context. Altogether, our findings suggest that it is perhaps more apt to think of current book bans as a political tactic to galvanize conservative voters in increasingly divisive electoral political districts, rather than as a pragmatic effort to restrict access to certain materials.

Additionally, we test for the presence of two competing common effects of censorship: (i) the successful suppression of information ( 27 ) or (ii) a backlash effect, also known as the “Streisand effect,” where attempts at censorship drive more attention to the information ( 28 ). We find that there is very little interest in banned books even before they are banned. Furthermore, we find that the bans rarely intervene to draw more or less attention to a book, with national and state levels of interest in books remaining largely unaffected after they are banned. These findings suggest that while many banned books and authors are in line with the “culture wars” surrounding race and gender, bans are likely ineffective as a form of mass censorship of these topics. These findings compel us to reconsider book bans not solely as cultural or educational issues but as forms of political action, targeting the ballot box via library shelves and classrooms.

We investigate three aspects of contemporary book bans. First, we assess the variety of content and identities of authors that are being targeted. We address the first question by grouping crowd-sourced book genres into broad thematic clusters, and the latter by collecting and analyzing self-identified author demographic information. Second, we ask in what contexts books are most likely to be banned via a series of regression analyses applied to a broad range of county-level demographic factors. Finally, we ask how interest changes after books are banned through a pre–post analysis across several indicators of interest, including book sales and Google searches. Table S1 lists each research question and data source.

Types of banned books and authors

We use an inductive, data-driven approach to produce a high-level typology of books that are banned. The goal of this approach is to identify high-level book groupings (which we refer to as “genres”) based on book subgenres, such that each book is more similar in subgenre composition to the other books within its genre than to books in other genres. We use crowd-sourced book subgenres from Goodreads—a popular website where users can list and review books they read—yielding 143 unique subgenres (e.g. “Fantasy,” “LGBT,” “American History”) among the banned books in our sample, with each individual book associated with up to 10 subgenres. This procedure, based on the commonly combined Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) and Hierarchical Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (HDBSCAN) algorithms (( 29 , 30 ); see Materials and methods for more details on the clustering procedure), identified six thematic genre clusters that parsimoniously characterize the banned books (Fig. S1 ).

We summarize these genres, in order of frequency, as: (i) children's books with diverse characters, including both LGBTQ+ characters and characters of color (37%), (ii) nonfiction books about social movements and historical figures (22%), (iii) fantasy and science fiction (10%), (iv) young adult queer romance novels (10%), (v) women-centered fiction (10%), and (vi) fiction with mature, nonromance themes, like violence or drug use (7%), with 4% of books remaining unclustered as outliers (Fig. 1 A). These trends remain relatively stable across the 12 months of the 2021–2022 school year, with a peak for book banning in the winter months, when school boards are more likely to be actively meeting (Fig. 1 B).

Children's books featuring diverse characters are most likely to be banned. A) Proportion of banned books clustered into each genre. Books ( N = 1,370) can only be clustered into one genre, so genres sum to 100%. B) Number of bans per genre over time. Number of bans ( N = 2,532; books can be banned multiple times) per genre each month over the 2021–2022 school year, smoothed with loess.

In addition to characterizing the main genres targeted by book bans, we identify how bans also operate to censor authors from various demographic groups. Through an Amazon Mechanical Turk crowd-sourcing task, we collected the self-identified gender, race, ethnicity, and sexuality of the 1,139 unique authors in our sample (with 95.7% of authors having a publicly-available online profile containing the information). We found that 64% of banned authors are women and 3% are nonbinary, while only 29% are men. In addition, 19% of authors in our sample self-identify as LGBTQ+ and 39% as people of color (Asian, Black, Hispanic, Indigenous, or otherwise self-identifying as a person of color).

To identify how the demographics of banned authors might systematically differ from the general author population, we compare them to (i) the US Census group who self-identify as authors ( 31 ) and (ii) a dataset of authors who wrote the most popular books from 1950–2018 ( 32 ), where popular books were defined as those published by the most prolific publishing houses and held by at least 10 libraries. We find that while women and LGBTQ+ authors are slightly overrepresented among banned authors, authors of color are strongly overrepresented among banned authors (women, χ 2 (2, N = 4,631) = 14.5, P < 0.001; LGBTQ+, χ 2 (1, N = 4,610) = 6.8, P = 0.009; people of color, χ 2 (2, N = 4,887) = 839.6, P < 0.001; Fig. S2 ).

In fact, the odds that an author of color was banned is 4.5 times higher than a white author, in comparison to all authors ( z = 7.8, P < 0.001; Fig. 2 A), and 12.0 times higher than a white author, in comparison to only the most popular authors ( z = 25.1, P < 0.001; Fig. 2 B). This phenomenon is driven largely by women of color, who make up 24% of banned authors in our sample, roughly twice the proportion of authors of color overall ( 31 ) and five times the proportion of authors of color who wrote the most popular books from 1950–2018 ( 32 ). Unfortunately, neither reference group of authors collected intersectional gender and race information (e.g. the proportion of authors who are women of color) or information about nonbinary authors (Fig. S2 ).

Books written by authors of color are far more likely to be banned. Odds ratios, split by demographic variable (race, gender, and whether an author identified as LGBTQ+), comparing the proportion of authors who wrote banned books in the United States during the 2021–2022 school year to A) the proportion of authors who listed their occupation as a writer or author in the United States in 2022 ( 31 ), which does not collect data on LGBTQ + authors, e.g. where odds POC /odds white = ( n POC banned / n POC all )/( n white banned / n white all ) and B) the proportion of authors who wrote the most popular books in the United States from 1950–2018 ( 32 ), e.g. where odds POC /odds white = ( n POC banned / n POC popular )/( n white banned / n white popular ). 95% confidence intervals and statistical significance were assessed via a z test.

Further, we find that the types of books authors write are associated with their identities. Children's books and nonfiction books about social movements were the most popular genres for each intersectional group of authors (e.g. non-LGBTQ+ white men or LGBTQ+ women of color), with the exception of nonbinary authors, who were more likely to write fantasy sci-fi books than any other genre (Fig. S3 ). However, non-LGBTQ+ women of color were more likely than any other group to write children's books featuring diverse characters, the most frequently banned category of books. By banning children's books, women authors of color are effectively banned as well.

Socio-political environments of book bans

While the majority of book bans occurred in Florida, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas, they appear across the country (32 states), indicating that there are contextual factors motivating book bans beyond simple regional tendencies (Fig. 3 A). In order to assess the factors that predict book bans, we establish a comparison group comprised of counties that were not the site of book bans but which share a commuting zone with at least one county whose schools did ban books. Commuting zones are official designations developed by the US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service that group counties based on dense economic interrelationships. Each county belongs to exactly one commuting zone, of which there are 709 in total. This empirical strategy allows us to investigate how counties with school districts that ban books might differ along social and political lines despite sharing a similar socioeconomic background, regional context, and, presumably, culture.

Republican vote share predicts bans across counties in the same commuting zone. A) Distribution of book bans across US counties (2021–2022). Counties containing school districts that banned books in the 2021–2022 school year are compared to neighboring counties in the same commuting zones that did not ban books. There were no book bans in Hawaii (not displayed) during the study period. B) Republican vote share in book-banning counties vs. neighboring counties. The fraction of voters in counties with and without book bans who voted for the Republican presidential candidate each year, beginning in 2000.

Given the lack of prior quantitative research about the current wave of book bans, we test for a broad range of potentially associated factors including immigration patterns, average income and education levels, rates of religious observance, racial demographics, and political participation (Fig. S4 ). For example, one could imagine that racial threat ( 33 , 34 ) associated with local influxes of nonwhite immigrants might increase the likelihood of local book bans, or that parents of higher socioeconomic status have more free time to devote to volunteer activities ( 35 ), or that religiosity net of political identity is associated with support for censorship ( 36 ).

Across all factors, one of the most substantial distinctions between counties that banned books and those in the same commuting zone that did not was the change in vote share won by Republican candidates in US presidential elections. From 2000 to 2016, there was no significant difference in Republican vote share between counties that banned books and others in their commuting zone that did not ban books (Fig. 3 B). However, in 2020, counties with a weakened Republican majority, although still remaining above 50%, went on to ban books during the 2021–2022 school year while the nearby countries where the Republican majority gained strength did not ban books. Regression analyses identify that books are banned in communities that are wealthier, more educated and whiter, but the change in Republican vote share remains one of the strongest and most significant predictors across multiple specifications (Table S2 ). In other words, Republican strongholds were not likely to ban books while counties with increasingly precarious conservative majorities were.

Interest in banned books

We use two different indicators—internet searches and book sales—to assess national interest in the banned books in the months prior to and proceeding each ban. Both interest indicators only cover a fraction of the total number of bans ( Bookshop.org , 13%; Google Trends, 62%), with data unavailable for the remaining bans because of low interest (i.e. there were no sales or too few Google searches to populate the Google Trends data). The different rates of available data across the two indicators reflect the different types of interest captured in the two datasets; for example, it takes significantly less effort to search for a book online than it does to purchase it.

There is strikingly low overall national interest across both indicators throughout the period of our study. This is particularly noteworthy given the historical focus of censorship on banning popular books. The low data availability is consistent with our other data collection efforts (see Section S3 for more information). The individuals and organizations that advocate for book bans presumably strive for a decrease in interest, which would be a sign of effective censorship, an effect we are unlikely to see at the national level. Conversely, we could expect increased interest due to a “Streisand effect” ( 28 ), whereby interest rises following the ban due to the increased media attention or as a form of protest.

We observe a small positive change—approximately 1%—comparing the three months following a ban and the 3 months prior among national Google search results for books (Fig. 4 A), but this is not evident in the sales data (Fig. 4 B). However, this is tempered by the large rate of missing data and the null results of the sales, suggesting that book bans produce little change in the number of people who engage (or do not) with a book. Primarily, we find that bans are directed at books that largely do not attract the public's interest to begin with.

Interest in books does not substantially change after they are banned. Average interest across the 3 months prior to each ban and 3 months after each ban, with 95% confidence intervals, for A) Google Trends searches, which has a small significant positive change in mean interest and B) Bookshop.org sales, which do not significantly change.

The relationship between national levels of interests in banned books and the local effects are unknown. Indeed, data availability prohibits more targeted estimates ( Section S3 ). While national levels of Google searches increase slightly after books are banned, at the state level, searches do not change significantly (Fig. S9 ). At the local level, Seattle Public Library's open data portal allows us to access book check-out data, and we find these local results to be consistent with the national- and state-level trends: interest is generally low both pre- and post-ban, and does not change (Fig. S10 ). However, no school district in Seattle banned books during our study period nor is the city representative of areas that generally ban books. Even so, we interpret these null results as confirming our broader argument that contemporary book bans do not generally target popular books.

Disaggregating interest data for each of the five most frequently banned books in our sample, we find that there is only a small increase in interest for one book: Gender Queer: A Memoir ( 37 ), which received more Google searches in the months after a ban than it did preceding (Fig. S5 ). It is not possible to distinguish the increased interest in Gender Queer: A Memoir as a backlash effect to the ban or a general rise due to the increased media attention the book received as the country's most frequently banned book.

Book bans are increasingly common in US schools and libraries, suggesting censorship is growing within certain participatory democracy systems. Our large-scale study identifies consistent features of contemporary book bans: the books targeted for bans are most often children's books and nonfiction books about historical figures; they are disproportionately likely to be written by women and authors of color, particularly women of color; and the general US public has low levels of interest in them, both before and after bans occur. Further, we find books are more likely to be banned by school districts in counties with increasingly contested presidential elections compared with neighboring counties: specifically, those in which the Republican candidate, while still winning over 50% of votes, faces stronger competition from Democratic challengers than in previous elections. This is one of the strongest predictors that a school district within a county will ban a book. Despite the increasing prominence of book bans in American political and social life, bans tend to target books with relatively low sales and interest to begin with, suggesting that the goals of traditional forms of censorship (i.e. suppression of oppositional information) are not the most important practical outcome of book bans.

These findings prompt an expansion of the dominant censorship narrative around book bans. We do not propose that conservative organizers are uninterested in restricting access to content they deem objectionable. However, our results demonstrate that bans are impractical efforts of censorship, insofar as they are directed at rather marginal cultural objects. Furthermore, at a time when roughly 97% of 3- to 18-year-olds have home internet access ( 38 ), it is unclear whether the removal of school books meaningfully restricts student access to their, or similar, content.

This raises the question: if they are not meaningful censorship campaigns, what are book bans accomplishing? We argue that our findings are suggestive evidence that book banning primarily serves as a reaction to increasingly contested, local political contexts. Given the strong association between conservatism and book bans in contemporary media coverage, it is somewhat surprising that the counties banning books are less conservative (as proxied by presidential elections) than neighboring counties, in particular since the 2016 election. One way to resolve this apparent contradiction is to interpret book bans as a form of collective action whose primary motive is to galvanize an apparently shrinking voting bloc by appealing to “culture war” antagonisms around race, gender, and sexual identity, rather than (or in addition to) as a form of control directed at access to certain cultural and intellectual goods. From this perspective, we identify censorship as a strategy potentially used to mobilize conservative voters, rather than an authoritarian, top-down approach of suppressing information in the perceived interest of the state.

In light of our findings, further work should better distinguish the political efficacy and spread of book bans, especially those targeting diverse casts of characters, women and nonbinary authors, and authors of color. In particular, identifying how book bans might galvanize conservatives’ involvement in local politics and increase voter turnout will be required for better understanding the political effects of book bans. Our results are compatible with at least two different, but nonmutually exclusive interpretations that future work could disambiguate: (i) that due to the politically contested nature of these districts grassroots interest in local book bans precedes and ultimately benefits from the intervention of politicians and groups such as Moms for Liberty, or whether (ii) these organized groups identify candidate school districts on the basis of electoral politics and subsequently mobilize conservative parents in the area.

Additionally, while we find no evidence for mass censorship at a national scale, it is possible that book bans are associated with other outcomes at the local level. To this end, more qualitative work about the experience of parents and children in schools that ban books is necessary. Children's books, particularly those that win awards, already over-represent white characters ( 39 ) and there is a risk that further removing books featuring characters of color and LGBTQ+ characters from school shelves will only exacerbate what Ebony Elizabeth Thomas calls the “Diversity Crisis” in children's and young adult literature, whereby characters of color are scarce and often only depicted as the subjects of violent plot points ( 40 ). This could have serious implications for a child's sense of belonging in their community—regardless of whether they can still feasibly access the content of the books in other ways—that is invisible at the national level of our analysis. Even children belonging to social groups that are not targeted by these efforts may experience adverse consequences in learning outcomes if their schools become the sites of political contestation ( 41 ).

Our study is necessarily limited by data availability ( Section S3 ). The PEN America Index of Book Bans is the most comprehensive resource available but should not be interpreted as an absolute record of all bans. We are not able to differentiate between bans that are still in effect and those that were implemented and then overturned by the school board. The availability of books at each school is also not known: books might be placed on a no-purchase list or otherwise barred from acquisition before they have the opportunity to be banned from shelves; alternatively, banned books may never appear in the most conservative districts due to a lack of demand rather than a coordinated removal. In general, there is very little accessible data about book sales and interest. Despite the celebrity of “Best Seller” lists, book sales are heavily embargoed and it is not possible to extract usable sales data from Amazon, which represents about half of the online book sales and 75% of the ebook market ( 42 ). These data restrictions pose difficulties for assessing the state of banned books in particular and the diversity of the publishing industry in general ( 43 ). The open data portal provided by the Seattle Public Library offers a sign of promise for the collection of book interest and engagement data, although it requires a level of infrastructure unavailable to most school districts and libraries. It is possible that more robust and localized sales or library check-out data would be better positioned to identify the presence of a censorship effect, although our results suggest this is most likely not the case.

Our results allow us to better understand the rise of book bans. Book banning appears more similar to political strategies to receive attention and exert power. This is not to say that we should dismiss them as censorship attempts, but rather understand their primary purpose as most likely something other than information suppression, especially since the vast majority of the books banned are not popular books. In fact, the most sensational cases of book bans, which receive the majority of media attention, are rarely representative of the average banned book. While classic novels like Harper Lee's To Kill A Mockingbird ( 44 ) and Toni Morrison's Beloved ( 45 ) do appear in our sample of banned books, it is far more likely that banned books are picture books or contemporary educational nonfiction books about important historical figures. Attention should be directed towards the children's books that make up the majority of the bans and future research should investigate which books are the target of bans and which stay on shelves.

As bans continue to increase across the country, our results suggest that these are political actions in addition to censorship tactics. The political ramifications of book bans remain under-examined. For example, in one Texas school district, an estimated $30,000 was spent compensating hundreds of hours of staff time reviewing and adjudicating book bans during the 2022–2023 school year ( 46 ). As book bans continue, they will infringe upon student's rights to information and incur heavy costs on taxpayers. Understanding their political context is an imperative.

We rely on PEN America's Index of School Book Bans ( 26 ), which includes instances in the United States in which student access to a book is restricted for a period of time, either in a school library or classroom. It is assembled through reviews of news articles, school websites, and letters to school districts, and should be considered a conservative estimate of book bans in the United States. It does not include books that were deaccessioned through standard procedures nor can it speak to books that were not purchased by the school in the first place. We use this dataset to identify each instance of book banning and each banned book (which could be banned by multiple school districts). The dataset documents a total of 2,532 bans and 1,649 unique books in the United States during the 2021–2022 school year. Table S1 summarizes our data sources and their relation to our research questions.

County-level data

We matched each school district in the PEN America list to their respective counties and augmented each ban with county-level demographic data from the US Census Bureau. We combine this with the county-level presidential vote share data from the MIT Election Data and Science Lab ( 47 ) and data from the US Religion Census Religious Congregations and Membership Study ( 48 ). It is important to highlight that 29 school districts (out of 146) span more than one county. In these cases, all the counties that overlap with the school district were marked as a county that banned a book in the period. In our final sample, there are a total of 621 counties. Among these, 146 counties are home to school districts that enacted book bans during the specified period. The remaining 475 counties are counties in the same commuting zones as those that banned books but did not have their school districts enact book bans during that time.

Book-level metadata

We collect book-level metadata from multiple sources. First, we collected all the Goodreads genres listed for every banned book. Goodreads is a digital platform owned by Amazon that allows users to track their reading habits and leave reviews for books. Goodreads crowd-sources its genre labels through “user shelves” which function as a reader-produced classification system ( 49 ). For the 1,371 books in our sample that could be found on Goodreads with genre annotations (83%), there were a total of 143 unique genres, with each book having a maximum of 10 genre associations—such as “Law,” “Feminism,” “Young Adult,” or “Fantasy”—per book and an average of 7.2 genres per book before preprocessing. Because genre associations are derived from Goodreads users rather than publishers or authors, we manually created a set of genre correspondences to ensure qualitative consistency among genres (such that, e.g. a book tagged “Lesbian” would necessarily also be tagged “LGBT” if it were not already). After this preprocessing, the average book was linked to 7.8 genres.

With each book represented as a vector of genre dummy variables in this 143-genre feature space, we used the UMAP algorithm ( 50 ) to convert this sparse representation to a dense, 2D, and continuous one, then clustered these 2D representations of each book using the HDBSCAN algorithm ( 30 ). We combine these algorithms as UMAP's dimensionality reduction has been shown to improve the performance of HDBSCAN ( 51 , 52 ), while also enabling 2D visualization. As with many clustering applications, a model which yields too few clusters may obscure important variation in the data, while too many clusters can undermine the ultimate goal of summarizing data in a qualitatively legible way. Given that our purpose for clustering is to summarize and yield qualitative insights about our data rather than other downstream applications, we explored a range of hyperparameters and evaluated them in terms of the percent of books left unclustered (which we sought to minimize) and qualitatively, in terms of the perceived quality and distinctiveness of clusters. In the end we selected a model that yields six high-level genre clusters of books.

Finally, we used the Google Books API to gather short descriptions of each book (generally similar or identical to what appears on the book's back cover). After removing blurbs from critics and author bios such that only descriptions of book content per se remained, we fit a structural topic model ( 53 ) to these documents to provide an overview of lexical themes and their interrelations within the corpus of book descriptions. As the results of the topic model substantively replicate those of the genre-based analysis, we include them in the supplement (Fig. S1) rather than present them here.

Author demographic data

We collected the self-identified gender, race, and sexuality of each author in our dataset through an Amazon Mechanical Turk crowd-sourcing task that asked participants to collect such self-reported data from publicly available biographies on author websites, Wikipedia pages, and similar sources. We tested and timed the task to take around 3 min for a user new to the task to complete. We intentionally did not use a name-based algorithmic classifier to obtain this information because of known biases, especially for those who identify as people of color ( 54 ).

To assess the quality of information obtained, we audited a random sample of the results ( N = 50 authors). We found that the majority of authors who self-identified their gender, race/ethnicity, or sexuality online were found by participants, but 22% of authors who self-identified as queer and 19% of authors who identified their race and/or ethnicity were not found by participants, so our estimates of the proportions of queer authors and authors of color are likely conservative. However, participants generally copied over the information accurately (98% accuracy for gender information, 85% for sexuality information and 100% for race/ethnicity information). Detailed results of this audit can be found in Table S3 .

We compared our results to two reference datasets: (i) the proportion of writers and authors in the United States who listed their occupation as a writer or author in 2020, provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics ( 31 ) and (ii) the proportion of authors who wrote the most popular books in the United States from 1950 to 2018 ( 32 ). Unfortunately, neither reference source collected cross-tabulated (intersectional) gender and race data (for example, the proportion of authors who are women of color).

Interest data

We leverage two distinct measures of interest to assess the possible impact of book bans, comparing the average interest in the 3 months prior to and following each ban. Outside of best seller lists, book sales data are heavily embargoed, with the top provider of book data to publishing houses refusing to license their data for academic research or interested individuals ( 43 ). To overcome this limitation, we negotiated access to restricted-use sales data from Bookshop.org , an online platform responsible for about 1% of the online book market in the United States. While sales data are likely the most robust measure of interest in a book, we complemented the sales data with a weaker yet broader measure of interest—search data from Google Trends (for more details see Section S3 ). The Bookshop.org data is normalized as they shared the data with us under the condition that we do not report exact sales. Both the Bookshop.org and Google Trends results reported in the main text are measures of interest at the national level. We also ran Google Trends results at the state level and found that interest did not significantly change post-ban (Fig. S9 ). Finally, the most granular level of interest is at the local level, and there is very little public data available at the local level. We ran the same analysis using Seattle Library's open data portal, where we can collect the number of checkouts for each book in the city's library system, and again found no significant change (Fig. S10 ). However, Seattle is not representative of the regions that typically ban books, thus we cannot draw specific local-level conclusions, but as a large metropolitan area we expect that national-level effects, were they to exist, should be visible in these data and thus it serves as an additional robustness check of our national-level results.

For each interest indicator, we conduct a pre–post design, comparing the average interest across the 3 months preceding the ban with the three following months. The latter group contains the ban month itself. We chose a monthly time series measure because the PEN America dataset includes the month of each ban but not the day. Indeed, bans are likely to occur over several weeks as a group petitions the school district for the removal of a book, meetings are held, and a final decision is made. For robustness, we ran the same tests on different time groups (1 month, 4 months, 6 months); all groupings produce similar, nonsignificant results (Fig. S7 ).

We thank Chris Bail, Lizzie Martin, Jay A. Pearson, Alejandra Regla-Vargas, Nina Wang, Sam Zhang, and reviewers for helpful comments. We additionally thank Bookshop.org for their cooperation and generous sharing of data. This manuscript was posted on a preprint: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4618699 .

Supplementary material is available at PNAS Nexus online.

This research was assisted by a Social Science Research Council (SSRC)/Summer Institutes in Computational Social Science Research Grant.

All authors contributed equally to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, and writing.

Open-source code used for our analyses is available at https://zenodo.org/records/10982953 . All underlying source data used to run our analyses is available at https://zenodo.org/records/10982955 , with the exception of the restricted-use book sales data and the author demographic data. Anonymized versions of the book sales data and author demographic data are included in the open-source repository, but the full versions may be available upon request to qualified researchers.

Zimmerman J . 2022 . Whose America? Culture wars in the public schools . 2nd ed. Chicago (IL) : The University of Chicago Press .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Boyer PS . 2009 . Gilded-age consensus, repressive campaigns, and gradual liberalization. In: Kaestle C , Radway J , editors. A history of the book in America: volume 4: print in motion: the expansion of publishing and reading in the United States, 1880–1940 . Chapel Hill (NC) : University of North Carolina Press . p. 276 – 298 .

Donaldson S . 1991 . Censorship and a farewell to arms . SAF . 19 ( 1 ): 85 – 93 .

Oltmann SM . 2023 . The fight against book bans: perspectives from the field . London, England : Bloomsbury .

Caldweall-Stone D . 2022 . Letter to house oversight committee opposing book bans and challenges to free speech. https://alair.ala.org/handle/11213/18004

Curtis J . 2022 . The effect of the 2020 racial justice protests on attitudes and preferences in rural and urban America . Soc Sci Q. 103 ( 1 ): 90 – 107 .

Yuracko KA . 2022 . The culture war over girls’ sports: understanding the argument for transgender girls’ inclusion . Villanova Law Rev. 67 ( 4 ): 717 – 758 .

Gabbatt A . 2022 . ‘Unparalleled in intensity’—1,500 book bans in US school districts. The Guardian . https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/apr/07/book-bans-pen-america-school-districts

Harris EA , Alter A . 2022 . With rising book bans, librarians have come under attack. The New York Times . https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/06/books/book-ban-librarians.html

Harris EA , Alter A . 2023 . Book removals may have violated students’ rights, education department says. The New York Times . https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/22/books/book-banning-education-civil-rights.html

Natanson H , Rozsa L . 2022 . Students lose access to books amid ‘state-sponsored purging of ideas.’ Washington Post . https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2022/08/17/book-ban-restriction-access-lgbtq/

Delgado R , Stefancic J , Harris A . 2017 . Critical race theory . 3rd ed. New York (NY) : NYU Press .

Citizens for Renewing America . 2021 . Combatting critical race theory in your community: an A to Z guide on how to stop critical race theory and reclaim your local school board. https://citizensrenewingamerica.com/issues/combatting-critical-race-theory-in-your-community/

Lavietes M . 2023, April 25 . Over half of 2022's most challenged books have LGBTQ themes. NBC News . https://www.nbcnews.com/nbc-out/out-politics-and-policy/half-2022s-challenged-books-lgbtq-themes-rcna81324

Harris EA , Alter A . 2022 . A fast-growing network of conservative groups is fueling a surge in book bans. The New York Times . https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/12/books/book-bans-libraries.html

Vissing Y , Juchniewicz M . 2023 . Children's book banning, censorship and human rights. In: Zajda J , Hallam P , Whitehouse J , editors. Globalisation, values education and teaching democracy . Cham (Switzerland) : Springer International Publishing . p. 181 – 201 .

Perry A . 2023 . Pico, LGBTQ+ book bans, and the battle for students’ first amendment rights . Tul. JL & Sexuality . 32 : 197 – 219 .

Shearer M . 2022 . Banning books or banning BIPOC? Nw U L Rev Online . 117 : 24 – 45 .

Jaeger PT , et al. 2022 . Exuberantly exhuming McCarthy: confronting the widespread attacks on intellectual freedom in the United States . Libr Q. 92 ( 4 ): 321 – 328 .

Ferguson CJ . 2014 . Is reading “banned” books associated with behavior problems in young readers? The influence of controversial young adult books on the psychological well-being of adolescents . Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. 8 ( 3 ): 354 – 362 .

Hobbs WR , Roberts ME . 2018 . How sudden censorship can increase access to information . Am Political Sci Rev . 112 ( 3 ): 621 – 636 .

Roberts ME . 2018 . Censored: distraction and diversion inside China's Great firewall . Princeton (NJ) : Princeton University Press .

Roberts ME . 2020 . Resilience to online censorship . Ann Rev Political Sci . 23 ( 1 ): 401 – 419 .

Nabi Z . 2014 . R̶e̶s̶i̶s̶t̶a̶n̶c̶e̶ censorship is futile. First Monday . https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v19i11.5525

Swenson A . 2023 . Moms for Liberty rises as power player in GOP politics after attacking schools over gender, race. Associated Press . https://apnews.com/article/moms-for-liberty-2024-election-republican-candidates-f46500e0e17761a7e6a3c02b61a3d229

PEN America . 2022 . Pen America index of school book bans - 2021–2022 [dataset]. https://pen.org/banned-book-list-2021-2022/

Morozov E . 2011 . The net delusion: the dark side of internet freedom . New York (NY) : Public Affairs .

Jansen SC , Martin B . 2015 . The streisand effect and censorship backfire . Int J Commun . 9 ( 0 ): Article 0 .

McInnes L , Healy J , Melville J . 2020 . UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv:1802.03426. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1802.03426 , preprint: not peer reviewed.

McInnes L , Healy J , Astels S . 2017 . Hdbscan: hierarchical density based clustering . J Open Source Softw . 2 ( 11 ): 205.

Bureau of Labor Statistics . 2022 . Employed persons by detailed occupation, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

So RJ . 2020 . Redlining culture: a data history of racial inequality and postwar fiction . New York (NY) : Columbia University Press .

Blalock HM . 1967 . Toward a theory of minority-group relations . New York : Wiley .

Blumer H . 1958 . Race prejudice as a sense of group position . Pac Sociol Rev. 1 : 3 – 7 .

Nelson AA , Gazley B . 2014 . The rise of school-supporting nonprofits . Educ Finance Policy. 9 ( 4 ): 541 – 566 .

Droubay BA , Butters RP , Shafer K . 2021 . The pornography debate: religiosity and support for censorship . J Relig Health . 60 ( 3 ): 1652 – 1667 .

Kobabe M . 2019 . Gender queer: a memoir . St. Louis (MO) : Lion Forge .

National Center for Education Statistics . 2023 . Children’s Internet Access at Home. US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cch/home-internet-access#suggested-citation

Adukia A , Eble A , Harrison E , Runesha HB , Szasz T . 2021 . What we teach about race and gender: representation in images and text of children's books (Working Paper 29123) . National Bureau of Economic Research .

Thomas EE . 2019 . The dark fantastic: race and the imagination from Harry Potter to the hunger games . New York (NY) : New York University Press .

Burmester S , Howard LC . 2022 . Confronting book banning and assumed curricular neutrality: a critical inquiry framework . Theory Pract. 61 ( 4 ): 373 – 383 .

Anderson P . 2020, August 17 . US publishers, authors, booksellers call out Amazon's “Concentrated Power.” Publishing perspectives . https://publishingperspectives.com/2020/08/us-publishers-authors-booksellers-call-out-amazons-concentrated-power-in-the-book-market/

Walsh M . 2022, October 4 . Where is all the book data? Public books . https://www.publicbooks.org/where-is-all-the-book-data/

Lee H . 2002 . To kill a mockingbird . 1st Perennial Classics ed. Philadelphia (PA) : HarperCollins .

Morrison T . 1987 . Beloved . New York (NY) : Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Beloved .

Ryan S . 2023, March 29 . More than $30K of taxpayers’ money, 220 hours spent on single Spring Branch ISD book ban, docs show. ABC13 Houston . https://abc13.com/spring-branch-isd-book-ban-school-library-books-student-resources-texas-schoolbook-restrictions/13037457/

MIT Election Data and Science Lab . 2022 . County presidential election returns 2000–2020 (Version 11) [dataset]. Harvard Dataverse . https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VOQCHQ

Jones DE , Houseal R , Krindatch A , Stanley R , Grammich C , Hadaway K , Taylor RH . 2018 . U.S . religion census—religious congregations and membership study, 2010 (State File) . https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/X8D69

Walsh M , Antoniak M . 2021 . The goodreads “classics”: a computational study of readers, Amazon, and crowdsourced amateur criticism . J Cult Analyt . 6 ( 2 ): 243 – 287 . https://doi.org/10.22148/001c.22221 .

McInnes L , Healy J , Saul N , Großberger L . 2018 . UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection . J Open Source Softw . 3 ( 29 ): 861 .

Allaoui M , Kherfi ML , Cheriet A . 2020 . Considerably improving clustering algorithms using UMAP dimensionality reduction technique: a comparative study. In: El Moataz A , Mammass D , Mansouri A , Nouboud F , editors. Image and signal processing . Cham (Switzerland) : Springer International Publishing . p. 317 – 325 .

Blanco-Portals J , Peiró F , Estradé S . 2022 . Strategies for EELS data analysis. Introducing UMAP and HDBSCAN for dimensionality reduction and clustering . Microsc Microanal. 28 ( 1 ): 109 – 122 .

Roberts ME , Stewart BM , Tingley D . 2019 . Stm: an R package for structural topic models . J Stat Softw. 91 : 1 – 40 .

Lockhart JW , King MM , Munsch C . 2023 . Name-based demographic inference and the unequal distribution of misrecognition . Nat Hum Behav 7 ( 7 ): 1084 – 1095 .

Author notes

Supplementary data.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| June 2024 | 1,421 |

| July 2024 | 2,246 |

| August 2024 | 974 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Contact PNAS Nexus

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2752-6542

- Copyright © 2024 National Academy of Sciences

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events conversation

What Students Are Saying About Banning Books From School Libraries

Teenagers share their nuanced views on the various book banning efforts spreading across the country.

By The Learning Network

Please note: This post is part of The Learning Network’s ongoing Current Events Conversation feature in which we invite students to react to the news via our daily writing prompts and publish a selection of their comments each week.

In the article “ Book Ban Efforts Spread Across the U.S. ,” Elizabeth A. Harris and Alexandra Alter write about the growing trend of parents, political activists, school board officials and lawmakers arguing that some books do not belong in school libraries.

As we regularly do when The Times reports on an issue that touches the lives of teenagers, we used our daily Student Opinion forum to ask teenagers to share their perspectives . The overwhelming majority of students were opposed to book bans in any form, although their reasons and opinions were varied and nuanced. They argued that young people have the right to read unsanitized versions of history, that diverse books expose them to a variety of experiences and perspectives, that controversial literature helps them to think critically about the world, and that, in the age of the internet, book bans just aren’t that effective. Below, you can read some of their comments organized by theme.

Thank you to all those from around the world who joined the conversation this week, including teenagers from Japan ; Julia R. Masterman School in Philadelphia; and Patino High School in Fresno, Calif .

Please note: Student comments have been lightly edited for length, but otherwise appear as they were originally submitted.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Banned Books — Banned Books and the Freedom of Expression

Banned Books and The Freedom of Expression

- Categories: Banned Books Freedom of Expression

About this sample

Words: 793 |

Published: Sep 16, 2023

Words: 793 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The phenomenon of banned books, the implications of banned books, the paradox of banned books, the enduring value of intellectual freedom, conclusion: the unbreakable bond between books and freedom, 1. offensive content:, 2. political or ideological concerns:, 3. religious sensitivities:, 4. social justice and controversial themes:, 5. protecting children:, 1. suppression of free expression:, 2. preservation of ignorance:, 3. cultural impact:, 4. loss of artistic and literary value:.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3.5 pages / 1507 words

5 pages / 2245 words

5 pages / 2303 words

6.5 pages / 2859 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Banned Books

Go Ask Alice by Beatrice Sparks is a controversial book that has faced challenges and bans in various schools and libraries across the United States. The book, written in the form of a diary, chronicles the life of a teenage [...]

What do you think of when you hear the word library? Is a library a large repository of books? Is a library a place where students can access computers and other equipment? Is a library a quiet place where one can lose [...]

"The Giver" by Lois Lowry has been a controversial book since its publication in 1993, sparking debates about censorship, freedom of expression, and the role of literature in society. In this essay, we will explore the banning [...]

Banning books is a contentious and complex issue that has sparked debates for centuries. This essay delves into the topic of banning books, exploring the reasons behind book censorship, its impact on society, the arguments for [...]

Throughout history, the suppression of knowledge through banning or destroying books has been seen at some point in most modern societies. The reason as to why books are banned varies from different governments and their [...]

Notes from Underground written by Fyodor Dostoevsky and Grendel written by John Gardner are both novels which contain characters who suffer immensely as the novel progresses. Notes from Underground is a novel about a [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

When are book bans unconstitutional? A First Amendment scholar explains

Associate Professor of Law, University of Dayton

Disclosure statement

Erica Goldberg does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Dayton provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

The United States has become a nation divided over important issues in K-12 education, including which books students should be able to read in public school.

Efforts to ban books from school curricula , remove books from libraries and keep lists of books that some find inappropriate for students are increasing as Americans become more polarized in their views.

These types of actions are being called “book banning.” They are also often labeled “censorship.”

But the concept of censorship, as well as legal protections against it, are often highly misunderstood.

Book banning by the political right and left

On the right side of the political spectrum, where much of the book banning is happening, bans are taking the form of school boards’ removing books from class curricula.

Politicians have also proposed legislation banning books that are what some legislators and parents consider too mature for school-age readers, such as “ All Boys Aren’t Blue ,” which explores queer themes and topics of consent. Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison’s classic “ The Bluest Eye ,” which includes themes of rape and incest, is also a frequent target.

In some cases, politicians have proposed criminal prosecutions of librarians in public schools and libraries for keeping such books in circulation.

Most books targeted for banning in 2021, says the American Library Association, “ were by or about Black or LGBTQIA+ persons .” State legislators have also targeted books that they believe make students feel guilt or anguish based on their race or imply that students of any race or gender are inherently bigoted .

There are also some attempts on the political left to engage in book banning as well as removal from school curricula of books that marginalize minorities or use racially insensitive language, like the popular “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Defining censorship

Whether any of these efforts are unconstitutional censorship is a complex question.

The First Amendment protects individuals against the government’s “ abridging the freedom of speech .” However, government actions that some may deem censorship – especially as related to schools – are not always neatly classified as constitutional or unconstitutional, because “censorship” is a colloquial term, not a legal term.

Some principles can illuminate whether and when book banning is unconstitutional.

Censorship does not violate the Constitution unless the government does it .

For example, if the government tries to forbid certain types of protests solely based on the viewpoint of the protesters, that is an unconstitutional restriction on speech. The government cannot create laws or allow lawsuits that keep you from having particular books on your bookshelf, unless the substance of those books fits into a narrowly defined unprotected category of speech such as obscenity or libel. And even these unprotected categories are defined in precise ways that are still very protective of speech.

The government, however, may enact reasonable regulations that restrict the “ time, place or manner ” of your speech, but generally it has to do so in ways that are content- and viewpoint-neutral. The government thus cannot restrict an individual’s ability to produce or listen to speech based on the topic of the speech or the ultimate opinions expressed.

And if the government does try to restrict speech in these ways, it likely constitutes unconstitutional censorship.

What’s not unconstitutional

In contrast, when private individuals, companies and organizations create policies or engage in activities that suppress people’s ability to speak, these private actions don’t violate the Constitution .

The Constitution’s general theory of liberty considers freedom in the context of government restraint or prohibition. Only the government has a monopoly on the use of force that compels citizens to act in one way or another. In contrast, if private companies or organizations chill speech, other private companies can experiment with different policies that allow people more choices to speak or act freely.

Still, private action can have a major impact on a person’s ability to speak freely and the production and dissemination of ideas. For example, book burning or the actions of private universities in punishing faculty for sharing unpopular ideas thwarts free discussion and unfettered creation of ideas and knowledge.

When schools can ‘ban’ books

It’s hard to definitively say whether the current incidents of book banning in schools are constitutional – or not. The reason: Decisions made in public schools are analyzed by the courts differently than censorship in nongovernment contexts.

Control over public education, in the words of the Supreme Court, is for the most part given to “ state and local authorities .” The government has the power to determine what is appropriate for students and thus the curriculum at their school.

However, students retain some First Amendment rights: Public schools may not censor students’ speech, either on or off campus, unless it is causing a “ substantial disruption .”

But officials may exercise control over the curriculum of a school without trampling on students’ or K-12 educators’ free speech rights.

There are exceptions to government’s power over school curriculum: The Supreme Court ruled, for example, that a state law banning a teacher from covering the topic of evolution was unconstitutional because it violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment, which prohibits the state from endorsing a particular religion.

School boards and state legislators generally have the final say over what curriculum schools teach. Unless states’ policies violate some other provision of the Constitution – perhaps the protection against certain kinds of discrimination – they are generally constitutionally permissible.

[ Over 150,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today .]

Schools, with finite resources, also have discretion to determine which books to add to their libraries. However, several members of the Supreme Court have written that removal is constitutionally permitted only if it is done based on the educational appropriateness of the book, but not because it was intended to deny students access to books with which school officials disagree.