An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Effects of Mindfulness on Psychological Health: A Review of Empirical Studies

Shian-ling keng.

a Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708

Moria J. Smoski

b Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710

Clive J. Robins

Within the past few decades, there has been a surge of interest in the investigation of mindfulness as a psychological construct and as a form of clinical intervention. This article reviews the empirical literature on the effects of mindfulness on psychological health. We begin with a discussion of the construct of mindfulness, differences between Buddhist and Western psychological conceptualizations of mindfulness, and how mindfulness has been integrated into Western medicine and psychology, before reviewing three areas of empirical research: cross-sectional, correlational research on the associations between mindfulness and various indicators of psychological health; intervention research on the effects of mindfulness-oriented interventions on psychological health; and laboratory-based, experimental research on the immediate effects of mindfulness inductions on emotional and behavioral functioning. We conclude that mindfulness brings about various positive psychological effects, including increased subjective well-being, reduced psychological symptoms and emotional reactivity, and improved behavioral regulation. The review ends with a discussion on mechanisms of change of mindfulness interventions and suggested directions for future research.

Mindfulness is the miracle by which we master and restore ourselves. Consider, for example: a magician who cuts his body into many parts and places each part in a different region—hands in the south, arms in the east, legs in the north, and then by some miraculous power lets forth a cry which reassembles whole every part of his body. Mindfulness is like that—it is the miracle which can call back in a flash our dispersed mind and restore it to wholeness so that we can live each minute of life. Hanh (1976 , p. 14)

Mindfulness has been theoretically and empirically associated with psychological well-being. The elements of mindfulness, namely awareness and nonjudgmental acceptance of one's moment-to-moment experience, are regarded as potentially effective antidotes against common forms of psychological distress—rumination, anxiety, worry, fear, anger, and so on—many of which involve the maladaptive tendencies to avoid, suppress, or over-engage with one's distressing thoughts and emotions ( Hayes & Feldman, 2004 ; Kabat-Zinn, 1990 ). Though promoted for centuries as a part of Buddhist and other spiritual traditions, the application of mindfulness to psychological health in Western medical and mental health contexts is a more recent phenomenon, largely beginning in the 1970s (e.g., Kabat-Zinn, 1982 ). Along with this development, there has been much theoretical and empirical work illustrating the impact of mindfulness on psychological health. The goal of this paper is to offer a comprehensive narrative review of the effects of mindfulness on psychological health. We begin with an overview of the construct of mindfulness, differences between Buddhist and Western psychological conceptualizations of mindfulness, and how mindfulness has been integrated into Western medicine and psychology. We then review evidence from three areas of research that shed light on the relationship between mindfulness and psychological health: 1. correlational, cross-sectional research that examines the relations between individual differences in trait or dispositional mindfulness and other mental-health related traits, 2. intervention research that examines the effects of mindfulness-oriented interventions on psychological functioning, and 3. laboratory-based research that examines, experimentally, the effects of brief mindfulness inductions on emotional and behavioral processes indicative of psychological health. We conclude with an examination of mechanisms of effects of mindfulness interventions and suggestions for future research directions.

The word mindfulness may be used to describe a psychological trait, a practice of cultivating mindfulness (e.g., mindfulness meditation), a mode or state of awareness, or a psychological process ( Germer, Siegel, & Fulton, 2005 ). To minimize possible confusion, we clarify which meaning is intended in each context we describe ( Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009 ). One of the most commonly cited definitions of mindfulness is the awareness that arises through “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” ( Kabat-Zinn, 1994 , p. 4). Descriptions of mindfulness provided by most other researchers are similar. Baer (2003) , for example, defines mindfulness as “the nonjudgmental observation of the ongoing stream of internal and external stimuli as they arise” (p. 125). Though some researchers focus almost exclusively on the attentional aspects of mindfulness (e.g., Brown & Ryan, 2003 ), most follow the model of Bishop et al. (2004) , which proposed that mindfulness encompasses two components: self-regulation of attention, and adoption of a particular orientation towards one's experiences. Self-regulation of attention refers to non-elaborative observation and awareness of sensations, thoughts, or feelings from moment to moment. It requires both the ability to anchor one's attention on what is occurring, and the ability to intentionally switch attention from one aspect of the experience to another. Orientation to experience concerns the kind of attitude that one holds towards one's experience, specifically an attitude of curiosity, openness, and acceptance. It is worth noting that “acceptance” in the context of mindfulness should not be equated with passivity or resignation ( Cardaciotto, Herbert, Forman, Moitra, & Farrow, 2008 ). Rather, acceptance in this context refers to the ability to experience events fully, without resorting to either extreme of excessive preoccupation with, or suppression of, the experience. To sum up, current conceptualizations of mindfulness in clinical psychology point to two primary, essential elements of mindfulness: awareness of one's moment-to-moment experience nonjudgmentally and with acceptance .

As alluded to earlier, mindfulness finds its roots in ancient spiritual traditions, and is most systematically articulated and emphasized in Buddhism, a spiritual tradition that is at least 2550 years old. As the idea and practice of mindfulness has been introduced into Western psychology and medicine, it is not surprising that differences emerge with regard to how mindfulness is conceptualized within Buddhist and Western perspectives. Several researchers (e.g., Chambers, Gullone, & Allen, 2009 ; Rosch, 2007 ) have argued that in order to more fully appreciate the potential contribution of mindfulness in psychological health it is important to gain an understanding of these differences, and specifically, from a Western perspective, how mindfulness is conceptualized in Buddhism. Given the diversity of traditions and teachings within Buddhism, an in-depth exploration of this topic is beyond the scope of this review (for a more extensive discussion of this topic, see Rosch, 2007 ). We offer a preliminary overview of differences in conceptualization of mindfulness in Western usage versus early Buddhist teachings, specifically, those of Theravada Buddhism.

Arguably, Buddhist and Western conceptualizations of mindfulness differ in at least three levels: contextual, process, and content. At the contextual level, mindfulness in the Buddhist tradition is viewed as one factor of an interconnected system of practices that are necessary for attaining liberation from suffering, the ultimate state or end goal prescribed to spiritual practitioners in the tradition. Thus, it needs to be cultivated alongside with other spiritual practices, such as following an ethical lifestyle, in order for one to move toward the goal of liberation. Western conceptualization of mindfulness, on the other hand, is generally independent of any specific circumscribed philosophy, ethical code, or system of practices. At the process level, mindfulness, in the context of Buddhism, is to be practiced against the psychological backdrop of reflecting on and contemplating key aspects of the Buddha's teachings, such as impermanence, non-self, and suffering. As an example, in the Satipatthana Sutta (The Foundation of Mindfulness Discourse), one of the key Buddhist discourses on mindfulness, the Buddha recommended that one maintains mindfulness of one's bodily functions, sensations and feelings, consciousness, and content of consciousness while observing clearly the impermanent nature of these objects. Western practice generally places less emphasis on non-self and impermanence than traditional Buddhist teachings. Finally, at the content level and in relation to the above point, in early Buddhist teachings, mindfulness refers rather specifically to an introspective awareness with regard to one's physical and psychological processes and experiences. This is contrast to certain Western conceptualizations of mindfulness, which view mindfulness as a form of awareness that encompasses all forms of objects in one's internal and external experience, including features of external sensory objects like sights and smells. This is not to say that external sensory objects do not ultimately form part of one's internal experience; rather, in Buddhist teachings, mindfulness more fundamentally has to do with observing one's perception of and reactions toward sensory objects than focusing on features of the sensory objects themselves.

The integration of mindfulness into Western medicine and psychology can be traced back to the growth of Zen Buddhism in America in the 1950s and 1960s, partly through early writings such as Zen in the Art of Archery ( Herrigel, 1953 ) , The World of Zen: An East-West Anthology ( Ross, 1960 ), and The Method of Zen ( Herrigel, Hull, & Tausend, 1960 ). Beginning the 1960s, interest in the use of meditative techniques in psychotherapy began to grow among clinicians, especially psychoanalysts (e.g., see Boss, 1965 ; Fingarette, 1963 ; Suzuki, Fromm, & De Martino, 1960 ; Watts, 1961 ). Through the 1960s and the 1970s, there was growing interest within experimental psychology in examining various means of heightening awareness and broadening the boundaries of consciousness, including meditation. Early electroencephalogram (EEG) studies on meditation found that individuals who meditated showed persistent alpha activity with restful reductions in metabolic rate ( Anand, Chhina, & Singh, 1961 ; Bagchi & Wenger, 1957 ; Wallace, 1970 ), as well as increases in theta waves, which reflect lower states of arousal associated with sleep ( Kasamatsu & Hirai, 1966 ). Beginning in the early 1970s, there was a surge of interest in and research on transcendental meditation, a form of concentrative meditation technique popularized by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi ( Wallace, 1970 ). The practice of transcendental meditation was found to be associated with reductions in indicators of physiological arousal such as oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide elimination, and respiratory rate ( Benson, Rosner, Marzetta, & Klemchuk, 1974 ; Wallace, 1970 ; Wallace, Benson, & Wilson, 1971 ).

Despite the fact that research on mindfulness meditation had already begun in the 1960s, it was not until the late 1970s that mindfulness meditation began to be studied as an intervention to enhance psychological well-being. Application of mindfulness meditation as a form of behavioral intervention for clinical problems began with the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn, which explored the use of mindfulness meditation in treating patients with chronic pain ( Kabat-Zinn, 1982 ), now known popularly as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction. Since the establishment of MBSR, several other interventions have also been developed using mindfulness-related principles and practices, including Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002 ), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993a ) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999 ). In this review, both meditation-oriented interventions (i.e., MBSR and MBCT), as well as interventions that teach mindfulness using less meditation-oriented techniques (i.e., DBT and ACT), are considered as a family of “mindfulness-oriented interventions”, and thus are of empirical interest.

Correlational Research on Mindfulness and Psychological Health

Relationship between trait mindfulness and psychological health.

Many studies of mindfulness to date have reported on correlations between self-reported mindfulness and psychological health. Such correlations have been reported for samples of undergraduate students (e.g., Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006 ; Brown & Ryan, 2003 ), community adults (e.g., Brown & Ryan, 2003 ; Chadwick et al., 2008 ) and clinical populations (e.g., Baer, Smith, & Allen, 2004 ; Chadwick et al., 2008 ; Walach, Buchheld, Buttenmuller, Kleinknecht, & Schmidt, 2006 ). Before going over these findings, it may be helpful to review questionnaires that have been developed to measure mindfulness. Questionnaires that assess mindfulness as a general, trait-like tendency to be mindful in daily life include: Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory ( Buchheld, Grossman, & Walach, 2001 ), Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (KIMS; Baer et al., 2004 ), Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, 2003 ), Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire ( Baer et al., 2006 ), Cognitive Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised ( Feldman, Hayes, Kumar, Greeson, & Laurenceau, 2007 ), Toronto Mindfulness Scale-Trait Version ( Davis, Lau, & Cairns, 2009 ), Philadelphia Mindfulness Scale ( Cardaciotto et al., 2008 ), and Southampton Mindfulness Questionnaire ( Chadwick et al., 2008 ). Some of these questionnaires measure mindfulness as a single-factor construct. For example, the MAAS ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ) assesses mindfulness as the general tendency to be attentive to and aware of experiences in daily life, and has a single factor structure of open/ receptive awareness and attention. Other questionnaires measure mindfulness as a multi-faceted construct. For example, the KIMS ( Baer et al., 2004 ) contains subscales that correspond to four mindfulness skills conceptualized in DBT's framework: observing one's moment-to-moment experience, describing one's experiences with words, acting or participating with awareness, and nonjudgmental acceptance of one's experiences. In addition to trait measures of mindfulness, state measures of mindfulness have been developed to measure momentary mindful states. These measures include the Toronto Mindfulness Scale ( Lau et al., 2006 ) and Brown and Ryan (2003) 's state version of the MAAS.

Trait mindfulness has been associated with higher levels of life satisfaction ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ), agreeableness ( Thompson & Waltz, 2007 ), conscientiousness ( Giluk, 2009 ; Thompson & Waltz, 2007 ), vitality ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ), self esteem ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ; Rasmussen & Pidgeon, 2010 ), empathy ( Dekeyser, Raes, Leijssen, Leysen, & Dewulf, 2008 ), sense of autonomy ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ), competence ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ), optimism ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ), and pleasant affect ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ). Studies have also demonstrated significant negative correlations between mindfulness and depression ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ; Cash & Whittingham, 2010 ), neuroticism ( Dekeyser et al., 2008 ; Giluk, 2009 ), absent-mindedness ( Herndon, 2008 ), dissociation ( Baer et al., 2006 ; Walach et al., 2006 ), rumination ( Raes & Williams, 2010 ), cognitive reactivity ( Raes, Dewulf, Van Heeringen, & Williams, 2009 ), social anxiety ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ; Dekeyser et al., 2008 ; Rasmussen & Pidgeon, 2010 ), difficulties in emotion regulation ( Baer et al., 2006 ), experiential avoidance ( Baer et al., 2004 ), alexithymia ( Baer et al., 2004 ), intensity of delusional experience in the context of psychosis ( Chadwick et al., 2008 ), and general psychological symptoms ( Baer et al., 2006 ). Research also has begun to explore the association between mindfulness and cognitive processes that may have important implications for psychological health. For example, Frewen, Evans, Maraj, Dozois, and Partridge (2008) found that, among undergraduate students, mindfulness was related both to a lower frequency of negative automatic thoughts and to an enhanced ability to let go of those thoughts. Two other studies have also demonstrated an association between mindfulness and enhanced performance on tasks assessing sustained attention ( Schmertz, Anderson, & Robins, 2009 ) and persistence ( Evans, Baer, & Segerstrom, 2009 ).

Mindfulness has been shown to be related not only to self-report measures of psychological health, but also to differences in brain activity observed using functional neuroimaging methods. Creswell, Way, Eisenberger, and Lieberman (2007) found that trait mindfulness was associated with reduced bilateral amygdala activation and greater widespread prefrontal cortical activation during an affect labeling task. There was also a strong inverse association between prefrontal cortex and right amygdala responses among those who scored high on mindfulness, but not among those who scored low on mindfulness, which suggests that individuals who are mindful may be better able to regulate emotional responses via prefrontal cortical inhibition of the amygdala. Trait mindfulness also was negatively correlated with resting activity in the amygdala and in medial prefrontal and parietal brain areas that are associated with self-referential processing, whereas levels of depressive symptoms were positively correlated with resting activity in these areas ( Way, Creswell, Eisenberger, & Lieberman, 2010 ). These findings are consistent with the association of mindfulness with greater self-reported ability to let go of negative thoughts about the self (e.g., Frewen et al., 2008 ).

Relationship between Mindfulness Meditation and Psychological Health

Research also has examined the relationship between mindfulness meditation practices and psychological well-being. Lykins and Baer (2009) compared meditators and non-meditators on several indices of psychological well-being. Meditators reported significantly higher levels of mindfulness, self-compassion and overall sense of well-being, and significantly lower levels of psychological symptoms, rumination, thought suppression, fear of emotion, and difficulties with emotion regulation, compared to non-meditators, and changes in these variables were linearly associated with extent of meditation practice. In addition, the data were consistent with a model in which trait mindfulness mediates the relationship between extent of meditation practice and several outcome variables, including fear of emotion, rumination, and behavioral self-regulation. In two other studies, facets of trait mindfulness were found to mediate the relationship between meditation experience and psychological well-being in combined samples of meditators and non-meditators ( Baer et al., 2008 ; Josefsson, Larsman, Broberg, & Lundh, 2011 ). In addition to correlations with self-report measures, research has examined behavioral and neurobiological correlates of mindfulness meditation. Ortner, Kilner and Zelazo (2007) used an emotional interference task in which participants categorized tones presented 1 or 4 seconds following the onset of affective or neutral pictures. Levels of emotional interference were indexed by differences in reaction times to tones for affective pictures versus neutral pictures. A participant's mindfulness meditation experience was significantly associated with reduced interference both from unpleasant pictures (for 1 and 4 second delays) as well as pleasant pictures (for 4 second delay only), as well as higher levels of self-reported mindfulness and psychological well-being. These findings suggest that mindfulness meditation practice may enhance psychological well-being by increasing mindfulness and attenuating reactivity to emotional stimuli by facilitating disengagement of attention from stimuli. There is also emerging evidence from studies comparing meditators and non-meditators on a variety of performance-based measures that suggest that regular meditation practice is associated with enhanced cognitive flexibility and attentional functioning ( Hodgins & Adair, 2010 ; Moore & Malinowski, 2009 ), outcomes that may have important implications for psychological well-being. Research has also identified potential neurobiological correlates of mindfulness meditation by comparing brain structure and activity in adept mindfulness meditation practitioners to those of non-practitioners. These studies found that extensive mindfulness meditation experience is associated with increased thickness in brain regions implicated in attention, interoception, and sensory processing, including the prefrontal cortex and right anterior insula ( Lazar et al., 2005 ); increased activation in brain areas involved in processing of distracting events and emotions, which include the rostral anterior cingulate cortex and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, respectively ( Hölzel et al., 2007 ); and greater gray matter concentration in brain areas that have been found to be active during meditation, including the right anterior insula, left inferior temporal gyrus, and right hippocampus ( Hölzel et al., 2008 ). These findings are consistent with the premise that systematic training in mindfulness meditation induces changes in attention, awareness, and emotion, which can be assessed and identified at subjective, behavioral, and neurobiological levels (cf. Treadway & Lazar, 2009 ).

Overall, evidence from correlational research suggests that mindfulness is positively associated with a variety of indicators of psychological health, such as higher levels of positive affect, life satisfaction, vitality, and adaptive emotion regulation, and lower levels of negative affect and psychopathological symptoms. There is also burgeoning evidence from neurobiological and laboratory behavioral research that indicates the potential roles of trait mindfulness and mindfulness meditation practices in reducing reactivity to emotional stimuli and enhancing psychological well-being. Given the correlational nature of these data, experimental studies are needed to clarify the directional links between mindfulness and psychological well-being. Does training in mindfulness practices result in improvements in psychological well-being? Does psychological well-being facilitate greater mindfulness and/or inclination towards engagement in mindfulness practice? The next section reviews empirical evidence from studies of the effects of mindfulness-oriented interventions on psychological health.

Controlled Studies of Mindfulness-Oriented Interventions

Several mindfulness-oriented interventions have been developed and received much research attention within the past two decades, including MBSR, MBCT, DBT and ACT. Some research on these interventions has been uncontrolled and some has focused primarily on physical health outcomes. In this section, we limit our review to published, peer-reviewed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that assessed psychological health outcomes in adult populations. Some other promising interventions have also incorporated mindfulness techniques, including mindfulness-based relapse prevention ( Witkiewitz, Marlatt, & Walker, 2005 ) and exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression ( Hayes, Beevers, Feldman, Laurenceau, & Perlman, 2005 ), but no RCTs of those interventions have yet been published.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR): Description of Intervention and Review of Controlled Studies

MBSR is a group-based intervention program originally designed as an adjunct treatment for patients with chronic pain ( Kabat-Zinn, 1982 ; 1990 ). The program offers intensive training in mindfulness meditation to help individuals relate to their physical and psychological conditions in more accepting and nonjudgmental ways. The program consists of an eight-to-ten week course, in which a group of up to thirty participants meet for two to two and a half hours per week for mindfulness meditation instruction and training ( Kabat-Zinn, 1990 ). In addition to in-class mindfulness exercises, participants are encouraged to engage in home mindfulness practices and attend an all-day intensive mindfulness meditation retreat. The premise of MBSR is that with repeated training in mindfulness meditation, individuals will eventually learn to be less reactive and judgmental toward their experiences, and more able to recognize, and break free from, habitual and maladaptive patterns of thinking and behavior.

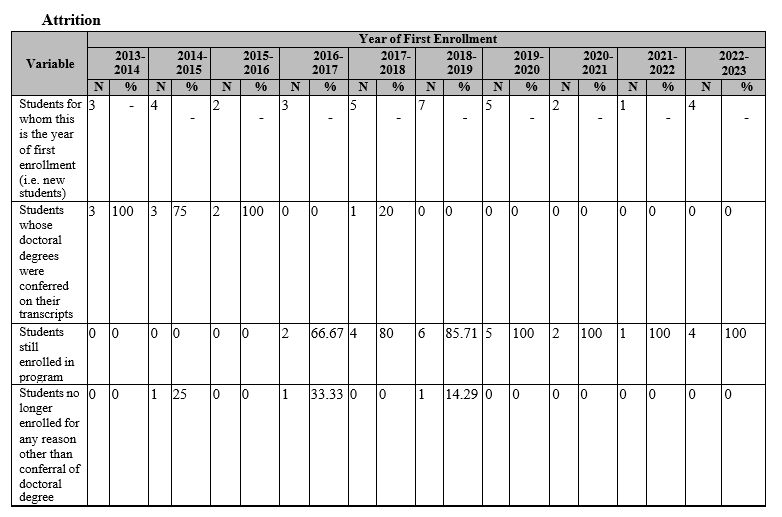

A number of RCTs of MBSR have been conducted among clinical and non-clinical populations, mostly using a waiting-list control design. Early studies were reviewed by Baer (2003) and Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, and Walach (2004) , but several important studies have since been published. Table 1 summarizes RCTs that have examined the impact of MBSR on psychological functioning. Overall, these studies found that MBSR reduces self-reported levels of anxiety ( Shapiro, Schwartz, & Bonner, 1998 ; Anderson, Lau, Segal, & Bishop, 2007 ), depression ( Anderson et al., 2007 ; Grossman et al., 2010 ; Koszycki, Benger, Shlik, & Bradwejn, 2007 ; Sephton et al., 2007 ; Shapiro et al., 1998 ; Speca, Carlson, Goodey, & Angen, 2000 ), anger ( Anderson et al., 2007 ), rumination ( Anderson et al. 2007 ; Jain et al., 2007 ), general psychological distress, including perceived stress ( Astin, 1997 ; Bränström, Kvillemo, Brandberg, & Moskowitz, 2010 ; Nyklíček, & Kuipers, 2008; Oman, Shapiro, Thoresen, Plante, & Flinders, 2008 ; Shapiro, Astin, Bishop, & Cordova, 2005 ; Speca et al., 2000 ; Williams, Kolar, Reger, & Pearson, 2001 ), cognitive disorganization ( Speca et al., 2000 ), post-traumatic avoidance symptoms ( Bränström et al., 2010 ), and medical symptoms ( Williams et al., 2001 ). It has been found to improve positive affect ( Anderson et al., 2007 ; Bränström et al., 2010 ), Nyklíček, & Kuijpers, 2008), sense of spirituality ( Astin, 1997 ; Shapiro et al., 1998 ), empathy ( Shapiro et al., 1998 ), sense of cohesion ( Weissbecker et al., 2002 ), mindfulness ( Anderson et al., 2007 ; Shapiro, Oman, Thoresen, Plante, & Flinders, 2008 ; Nyklíček, & Kuijpers, 2008), forgiveness ( Oman et al., 2008 ), self compassion ( Shapiro et al., 2005 ), satisfaction with life, and quality of life ( Grossman et al., 2010 ; Koszycki et al., 2007 ; Nyklíček, & Kuijpers,2008; Shapiro et al., 2005 ) among both clinical and non-clinical populations.

| Study | N | Type Participant | Mean Age | % Male | No. of Treatment Sessions | Control Group(s) | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 | College undergrads | NR | 5 | 8 2-hr sessions | NI (14) | MBSR > NI: reductions in psychological symptoms, increases in domain-specific sense of control & spiritual experiences | |

| 78 | Medical & premedical students | NR | 44 | 7 2.5-hr sessions | WL (41) | MBSR > WL: reductions in state and trait anxiety, overall distress, & depression, increases in empathy & spiritual experiences | |

| 90 | Cancer patients | 51 | 19 | 7 1.5-hr sessions | WL (37) | MBSR > WL: reductions in mood disturbance & symptoms of stress | |

| 103 | Community adults | 43 | 28 | 8 2.5-hr sessions, 1 8-hr session | Received educational materials and referral to community resources (44) | MBSR > Control Group: reductions in daily hassles, distress, & medical symptoms | |

| 91 | Fibromyalgia patients | 48 | 0 | 8 2.5-hr sessions | WL (40) | MBSR > WL: increase in disposition to experience life as manageable and meaningful | |

| 41 | Corporate employees | 36 | 29 | 8 2.5-hr sessions, 1 7-hr session | WL (16) | MBSR > WL: increased left-sided anterior activation & antibody titer responses to influenza vaccine, reduction in anxiety | |

| 38 | Health care professionals | NR | NR | 8 2-hr sessions | WL (20) | MBSR > WL: reductions in perceived stress & burnout, increases in self compassion & satisfaction with life | |

| 53 | Generalized social anxiety disorder patients | NR | NR | 8 2.5-hr sessions, 1 7.5-hr session | CBGT (27) | MBSR = CBGT: improvements in mood, functionality, & quality of life; MBSR < CGBT: reductions in social anxiety & response and remission rates | |

| 91 | Fibromyalgia patients | 48 | 0 | 8 2.5-hr sessions, 1 day-long session | WL (40) | MBSR > WL: reductions in depressive symptoms | |

| 36 | Community adults | 44 | 25 | 8 2-hr sessions | WL (16) | MBSR > WL: reduced activation of mPFC; increased activation of lPFC & several viscerosomatic areas when engaging in mindfulness exercises | |

| 81 | Students | 25 | 19 | 4 1.5 hr-sessions | SR (24), NI (30) | MBSR (a shortened program) = SR > NI: reductions in distress & increase in positive mood states; MBSR > NI: reductions in rumination & distraction | |

| 72 | Community adults | NR | NR | 8 2-hr sessions | WL (33) | MBSR = WL: performance on attentional tasks; Tx > WL: increases in mindfulness & positive affect; reductions in depression, anxiety symptoms, & general and anger-related rumination | |

| 44 | College undergrads | 18 | 20 | 8 1.5-hr sessions | EPP (14), WL (15) | MBSR = EPP > WL: reductions in perceived stress & rumination, increase in forgiveness | |

| Nyklíček, & Kuijpers, 2008 | 60 | Community adults with symptoms of stress | 44 | 33 | 8 2.5-hr sessions, 1 6-hr session | WL (30) | MBSR > WL: reductions in perceived stress & vital exhaustion, increases in positive affect & mindfulness |

| 44 | College undergrads | 18 | 20 | 8 1.5-hr sessions | EPP (14), WL (15) | MBSR = EPP > WL: increase in mindfulness | |

| 71 | Cancer patients | 52 | 1 | 8 2-hr sessions | WL (39) | MBSR > WL: reductions in perceived stress & posttraumatic avoidance symptoms, increase in positive states of mind | |

| 36 | Community adults | 44 | 25 | 8 2-hr sessions | WL (16) | MBSR > WL: reduced activation in medial and lateral brain regions, reduced deactivation in insula and other visceral and somasensory areas | |

| 150 | Patients with multiple sclerosis | 47 | 21 | 8 2.5-hr sessions, 1 7-hr session | UC (74) | MBSR > UC: increases in health-related quality of life, reductions in fatigue & depression |

NR = Not Reported; NI = No Intervention; WL = Wait-list; SR = Somatic Relaxation; CBGT = Cognitive-Behavioral Group Therapy; mPFC = medial prefrontal cortex; lPFC = lateral prefrontal cortex; UC = Usual Care.

Participation in MBSR has also been associated with brain changes reflective of positive emotional states and adaptive self representation and emotion regulatory processes, such as increases in left frontal activation, which is indicative of dispositional and state positive affect ( Davidson et al., 2003 ), increased activation in brain regions implicated in experiential, present-focused mode of self reference ( Farb et al., 2007 ), and reduced activation in brain regions implicated in conceptual processing, cognitive elaboration, and reappraisal ( Farb et al., 2010 ; Ochsner & Gross, 2008 ).

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT): Description of Intervention and Review of Controlled Studies

MBCT is an eight-week, manualized group intervention program adapted from the MBSR model ( Segal et al., 2002 ). Developed as an approach to prevent relapse in remitted depression, MBCT combines mindfulness training and elements of cognitive therapy (CT) with the goal of targeting vulnerability processes that have been implicated in the maintenance of depressive episodes. Like CT, MBCT aims to help participants view thoughts as mental events rather than as facts, recognize the role of negative automatic thoughts in maintaining depressive symptoms, and disengage the occurrence of negative thoughts from their negative psychological effects ( Barnhofer, Crane, & Didonna, 2009 ). However, unlike the traditional CT approach that places considerable emphasis on evaluating and changing the validity of the content of thoughts and developing alternative thoughts, MBCT aims primarily to change one's awareness of and relationship to thoughts and emotions ( Teasdale et al., 2000 ). The theoretical rationale on which MBCT is based ( Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995 ) is that the negative thoughts that accompany depression become associated with the depressed state, and that, as the number of depressive episodes increases, negative automatic thoughts become more easily reactivated by feelings of dysphoria, even when these do not occur in the context of a full-blown depressive episode. The negative thoughts, in turn, increase depressed mood and other symptoms of depression, leading to an increased risk for relapse to a major depressive episode. MBCT specifically targets loosening the association between negative automatic thinking and dysphoria. Because these associations are theorized to be stronger among those with a greater number of previous episodes, they may be expected to show the greatest benefit of the intervention.

Several RCTs, summarized in Table 2 , have evaluated the effects of MBCT on relapse prevention and other depression-related outcomes (for recent reviews, see Chiesa & Serreti, 2010 ; Coelho, Canter, & Ernst, 2007 ). Consistent with the theoretical model, initial studies found that MBCT reduced relapse rates among patients with three or more episodes of depression, but not among those with two or fewer past episodes ( Ma & Teasdale, 2004 ; Teasdale et al., 2000 ). Subsequent studies of MBCT and depression relapse selected only patients with three or more episodes and have replicated the effect of MBCT on reduced relapse rates ( Goldfrin & Heeringen, 2010 ; Kuyken et al., 2008 ) or prolonged time to relapse ( Bondolfi et al., 2010 ). Furthermore, MBCT also has been found to improve a range of symptomatic and psychosocial outcomes among remitted depressed patients, such as residual depressive symptoms and quality of life ( Goldfrin & Heeringen, 2010 ; Kuyken et al., 2008 ). There is also preliminary evidence that MBCT is more effective than treatment as usual (TAU) in reducing depressive symptoms among currently depressed patients ( Barnhofer et al., 2009 ; Hepburn et al., 2009 ). Lastly, MBCT has been adapted for treatment of bipolar disorder ( Williams et al., 2008 ), social phobia ( Piet, Hougaard, Hecksher, & Rosenberg, 2010 ), and depressive symptoms among individuals with epilepsy ( Thompson et al., 2010 ). The results of these studies are promising and in need of further replication.

| Study | N | Type Participant | Mean Age | % Male | No. of Treatment Sessions | Control Group(s) | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 145 | Patients in remission from depression | 43 | 24 | 8 2-hr sessions | TAU (69) | MBCT > TAU: reduction in rate of depressive relapse/recurrence for patients with 3 or more previous relapses, but not patients with 2 or fewer episodes | |

| * | 45 | Patients in remission from depression | 44 | 51 | 8 2-hr sessions | TAU (20) | MBCT > TAU: reduction in generality of autobiographical memory |

| 100 | Patients in remission from depression | 44 | 22 | 8 2-hr sessions | TAU (48) | MBCT > TAU: increase in metacognitive awareness | |

| 75 | Patients in remission from depression | 45 | 24 | 8 2-hr sessions | TAU (38) | MBCT > TAU: reduction in rate of depressive relapse/recurrence for patients with 3 or more previous relapses, but not patients with 2 or fewer episodes | |

| 68 | Patients in remission from depression and with a history of suicidal ideation or behavior | NR | NR | 8 2-hr sessions, 1 all-day session | WL (35) | MBCT + TAU > TAU: less increase in actual-ideal self discrepancy | |

| 123 | Patients in remission from depression and with a history of 3 or more depressive episodes | 49 | 24 | 8 2-hr sessions | m-ADM (62) | MBCT = m-ADM: rate of depressive relapse/recurrence; MBCT > m-ADM: reductions in residual depressive symptoms & psychiatric comorbidity, increase in quality of life | |

| 31 | Patients with recurrent depression and a history of suicidal ideation | 42 | 25 | 8 2-hr sessions | TAU (15) | MBCT > TAU: reductions in depressive symptoms & number of patients meeting full criteria for depression at post-treatment | |

| 68 | Patients in remission from depression and with a history of suicidal ideation | 44 | NR | 8 2-hr sessions, 1 6-hr session | TAU (35) | MBCT > TAU: reductions in depressive symptoms & thought suppression | |

| 27 | Depressed patients with a history of suicidal ideation or behavior | 42 | 33 | 8 2-hr sessions | TAU (13) | MBCT + TAU > TAU: reduced depression severity, increased meta-awareness of & specificity of memory related to previous suicidal crisis | |

| 68 | Patients with unipolar and bipolar disorders | NR | NR | 8 2-hr sessions, 1 all-day session | WL (35) | MBCT > WL: reduced depressive symptoms in both subsamples & less increase in anxiety among bipolar patients | |

| 60 | Patients in remission from depression and with a history of 3 or more depressive episodes | 47 | 28 | 8 2-hr sessions | TAU (29) | MBCT + TAU > TAU: prolonged time to relapse; Tx = TAU: rate of depressive relapse/recurrence | |

| 106 | Recovered depressed patients with a history of 3 or more depressive episodes | 46 | 19 | 8 2.75-hr sessions | TAU (54) | MBCT + TAU > TAU: reduced rate of depressive relapse/recurrence, depressive mood & quality of life | |

| 26 | Patients with social phobia | 22 | 30 | 8 2-hr sessions | GCBT (12) | MBCT = GCBT: reductions in symptoms of social phobia | |

| 53 | Patients with epilepsy and depressive symptoms | 36 | 19 | 8 1-hr sessions | TAU (27) | MBCT > WL: reduction in depressive symptoms |

NR = Not Reported; NI = No Intervention; WL = Wait-list; TAU = Treatment As Usual; m-ADM = Maintenance Anti-depressant Medication; GCBT = Group Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT): Description of Intervention and Review of Controlled Studies

DBT ( Linehan, 1993a ) was first developed as a treatment for chronic suicidal and other self-injurious behaviors, which are often present in patients with severe borderline personality disorder (BPD). It conceptualizes the dysfunctional behaviors of individuals with BPD as a consequence of an underlying dysfunction of the emotion regulation system, which involves intense emotional reactivity and an inability to modulate emotions. DBT integrates elements of traditional CBT with Zen philosophy and practice, and has a simultaneous focus on acceptance and behavior change strategies to help patients improve their emotion regulation abilities ( Linehan, 1993a ; Robins, 2002 ). There are four modes of treatment in DBT: individual therapy, group skills training, telephone consultation between therapist and patient, and consultation team meetings for therapists. Mindfulness skills are taught in the context of the skills-training group as a way of helping patients increase self acceptance, and as an exposure strategy aiming to reduce avoidance of difficult emotion and fear responses ( Linehan, 1993b ). These skills consist of a set of mindfulness “what” skills (observe, describe, and participate) and a set of mindfulness “how” skills (nonjudgmentally, one-mindfully, and effectively). Specific exercises that are used to foster mindfulness include visualizing thoughts, feelings, and sensations as if they are clouds passing by in the sky, observing breath by counting or coordinating with footsteps, and bringing mindful awareness into daily activities. Mindfulness skills are also integrated within the other three skills modules, which focus on distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness.

To date, 11 randomized trials of DBT, or adaptations of it, have been conducted ( Lynch, Trost, Salsman, & Linehan, 2007 ; Robins & Chapman, 2004 ). These studies are summarized in Table 3 . Standard outpatient DBT has been found to be more effective than TAU or another active treatment in reducing frequency and severity of parasuicidal and self harm behavior among individuals with BPD, especially those with a history of parasuicidal behavior; reducing number of inpatient psychiatric days, emergency visits, and hospitalizations ( Koons et al., 2001 ; Linehan, Amstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991 ; Linehan et al., 2006 ; Verheul et al., 2003 ); and in reducing substance use among individuals with co-morbid BDP and substance use disorders ( Linehan et al., 1999 ; Linehan et al., 2002 ). Among studies that included follow-up assessments, the effects of DBT were found to last for up to one year on the following outcome measures: number of parasuicidal behaviors, global functioning, social adjustment, and use of crisis services ( Linehan et al., 1991 ; Linehan et al., 2006 ; Linehan et al., 1999 ; Linehan, Heard, & Armstrong, 1993 ; Linehan, Tutek, Heard, & Armstrong, 1994 ). Finally, modifications of DBT have been found to be effective in binge eating disorder ( Telch, Agras, and Linehan, 2001 ), bulimia ( Safer, Telch, & Agras, 2001 ), and chronic depression in the elderly ( Lynch, Morse, Mendelson & Robins, 2003 ).

| Study | N | Type Participant | Mean Age | % Male | No. of Treatment Sessions | Control Group(s) | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46 | Chronically parasuicidal patients with BPD | NR | 0 | 1 year | TAU (22) | DBT > TAU: reductions in number of & medical severity of parasuicide behavior & number of psychiatric inpatient days, treatment retention; DBT = TAU: depression, hopelessness, suicidal ideation, & reasons for living | |

| 39 | Chronically parasuicidal patients with BPD | NR | 0 | 1 year | TAU (20) | DBT > TAU: increases in global functioning & social adjustment, reductions in parasuicide behavior & number of psychiatric inpatient days | |

| 26 | Chronically parasuicidal patients with BPD | 27 | 0 | 1 year | TAU (13) | DBT > TAU: reductions in anger, increases in global social adjustment & global functioning | |

| 28 | Patients with comorbid BPD and substance dependence | 30 | 0 | 1 year | TAU (16) | DBT > TAU: reductions in drug use, increased global & social adjustment, & treatment retention | |

| 24 | Patients with BPD | 22 | 21 | 1 year | CCT (12) | DBT > CCT: reductions in parasuicide behavior, suicidal ideation, depression, impulsivity, anger, & number of psychiatric inpatient days, & increase in global functioning | |

| 28 | Patients with BPD | 35 | 0 | 6 months | TAU (14) | DBT > TAU: reductions in suicidal ideation, depression, hopelessness, dissociation, & anger expression | |

| 44 | Patients with BED | 50 | 0 | 20 weeks | WL (22) | DBT > WL: reductions in number of binge episodes & days; DBT = WL: improvements in mood & affect regulation | |

| 31 | Individuals with at least one binge/purge episode per week | 34 | 0 | 20 weeks | WL (16) | DBT > WL: reductions in number of binge episodes & days; DBT = WL: improvements in mood & affect regulation | |

| 23 | Patients with comorbid BPD and substance dependence | NR | 0 | 1 year | CVT+12S (12) | DBT = CVT+12S: drug use; DBT > CVT+12S: maintenance of reduction of drug use throughout treatment; DBT < CVT+12S: treatment retention | |

| 58 | Patients with BPD | 35 | 0 | 1 year | TAU (31) | DBT > TAU: reductions in self-mutilating & self harm behaviors, treatment retention | |

| 34 | Depressed patients | 66 | 15 | 28 weeks | MED (17) (Note: In this study, MED was compared against MED+DBT) | DBT > MED: reduction in depression, improvements in dependency & adaptive coping, number of patients in remission at post-treatment | |

| 101 | Patients with BPD | 30 | 0 | 1 year | CTBE (49) | DBT > CTBE: reductions in suicide risk, medical risk of suicide attempts & self injurious behavior, psychiatric hospitalizations & emergency visits, treatment retention | |

| 35 | Patients with co-morbid depression and personality disorder | 61 | 34 | 24 weeks | MED (14) (Note: In this study, MED was compared against MED+DBT) | DBT > MED: reductions in interpersonal sensitivity & interpersonal aggression |

NR = Not Reported; BPD = Borderline Personality Disorder; TAU = Treatment As Usual; BED = Binge Eating Disorder; WL = Waiting List; CVT+12S = Comprehensive Validation Therapy with 12-Step; MED = Antidepressant Medication; CTBE = Community Treatment by Experts.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Description of Intervention and Review of Controlled Studies

ACT ( Hayes et al., 1999 ) was developed based on the premise that psychological distress is often associated with attempts to control or avoid negative thoughts and emotions, which often paradoxically increase the frequency, intensity, or salience of these internal events, and result in further distress and inability to engage in behaviors that would lead to valued long-term goals. Thus, the central aim of ACT is to create greater psychological flexibility by teaching skills that increase an individual's willingness to come into fuller contact with their experiences, recognize their values, and commit to behaviors that are consistent with those values. There are six core treatment processes that are highlighted in ACT: acceptance, defusion, contact with the present moment, self as context, values, and committed action ( Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006 ). Mindfulness is taught in the context of the first four processes, where a variety of exercises are used to enhance awareness of an observing self and foster the deliteralization of thoughts and beliefs. Although ACT does not incorporate mindfulness meditation exercises, its focus on helping patients cultivate present-centered awareness and acceptance is consistent with that of other mindfulness-based approaches ( Baer, 2003 ). ACT has been delivered in both individual and group settings, with durations varying from one day (e.g., Gregg, Callaghan, Hayes, & Glenn-Lawson, 2007 ) to 16 weeks (e.g., Hayes et al., 2004 ).

A number of studies, summarized in Table 4 , have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of ACT in treating a range of mental health outcomes, including those associated with depression, anxiety, impulse control disorders, schizophrenia, substance abuse and addiction, and workplace stress ( Hayes et al., 2006 ; Powers, Zum Vorde Sive Vording, & Emmelkamp, 2009 ). Specifically, ACT has been found to be more effective than TAU in improving affective symptoms, social functioning, and symptom reporting, and lowering rehospitalization rates and symptom believability among psychiatric inpatients with psychotic symptoms ( Bach & Hayes, 2002 ; Gaudiano & Herbert, 2006 ). Among populations with depressive and anxiety symptoms, ACT was generally found to be superior to no intervention, and as effective as another established treatment in reducing levels of depression, anxiety, and poor mental health outcomes ( Bond & Bunce, 2000 ; Forman, Herbert, Moitra, Yeomans, & Geller, 2007 ; Lappalainen et al., 2007 ; Zettle, 2003 ; Zettle & Hayes, 1986 ; Zettle & Rains, 1989 ). In addition, ACT has been shown to be effective at reducing substance use and dependence among nicotine-dependent ( Gifford et al., 2004 ) and polysubstance-abusing individuals ( Hayes et al., 2004 ). Finally, there is preliminary evidence indicating the effectiveness of ACT in treating trichotillomania ( Woods, Wetterneck, & Flessner, 2006 ).

| Study | N | Type Participant | Mean Age | % Male | No. of Treatment Sessions | Control Group(s) | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | Depressed patients | NR | 0 | 12 weeks | CT (12) | ACT > CT: reductions in depression & believability of thoughts; Tx = CT; frequency of automatic thoughts | |

| 31 | Depressed patients | 41 | 0 | 12 weeks | CCT (10) PCT (10) | ACT = CCT = PCT: reduction in depression; ACT < CCT & PCT: reduction in dysfunctional attitudes | |

| 90 | Volunteers of a media organization | 36 | 50 | 3 9-hr sessions | IPP (30) WL (30) | ACT = IPP > WL: reduction in depression & increase in propensity to innovate | |

| 80 | Psychiatric inpatients with psychotic symptoms | 39 | 64 | 4 45-50-min sessions | TAU (40) | ACT > TAU: improvement in symptom reporting, reductions in symptom believability & rates of hospitalization | |

| 24 | College students | 31 | 17 | 6 weeks | SD (12) | ACT = SD: reductions in math & test anxiety; ACT < SD: reduction in trait anxiety | |

| 76 | Nicotine-dependent smokers | 43 | 41 | 7 weeks | NRT (43) | ACT = NRT: average number of cigarettes smoked & quit rates | |

| 124 | Polysubstance-abusing Opiate Addicts | 42 | 49 | 16 weeks | MM (38) ITSF (44) | ACT = ITSF > MM: reductions in opiate & drug use (at follow up); ACT = ITSF = MM: reduction in distress & improvement in adjustment | |

| 25 | Patients with trichotillomania | 35 | 8 | 12 weeks | WL (13) | ACT > WL: reductions in hair pulling severity, impairment, & amount of hair pulled | |

| 40 | Psychiatric inpatients with psychotic symptoms | 40 | 64 | 3 sessions (average) | ETAU (21) | ACT > ETAU: reductions in affective symptoms, social impairment, & hallucination-associated distress | |

| 28 | Outpatients (mixed symptoms/ diagnoses) | 42 | 11 | 10 sessions | CBT (14) | ACT > CBT: reduced depression, improved social functioning | |

| 99 | Outpatients (mixed symptoms/ diagnoses) | 28 | 20 | 15-16 sessions (average) | CT (44) | ACT = CT: reductions in depression & anxiety, improvements in quality of life, life satisfaction, & general functioning |

Notes . NR = Not Reported; CT = Cognitive Therapy; CCT = Complete Cognitive Therapy; PCT = Partial Cognitive Therapy; WL = Waitlist; TAU = Treatment As Usual; SD = Systematic Desensitization; NRT = Nicotine Replacement Therapy; MM = Methodone Alone; ITSF = Intensive Twelve Step Facilitation Therapy Plus Methodone Maintenance; ETAU = Enhanced Treatment As Usual.

A growing research body supports the efficacy of all four major forms of mindfulness-oriented interventions, but several important research questions need to be addressed in future studies. Because these interventions all involve multiple components, future research should examine how individual treatment components, especially the mindfulness training component, contribute to overall treatment effects. Also, these interventions differ in how they teach mindful awareness, and future research could compare the efficacy of different mindfulness teaching approaches in fostering greater mindful awareness in daily life. For example, both MBSR and MBCT place considerable emphasis on engaging participants in formal meditative practices. DBT and ACT, on the other hand, incorporate a range of informal mindfulness exercises in their treatment approach. Research attention should also be devoted to possible moderators of treatment effects, such as pre-existing differences in coping style and types of cognitive processes maintaining a particular psychological problem. Finally, research needs to examine whether there is a dose-response relationship between amount of intervention exposure and amount of psychological benefits. Although MBSR in its standard form involves eight weekly 2-2.5 hour classes and an all-day retreat, it has been delivered in abbreviated forms to fit the needs of specific populations. Carmody and Baer (2009) examined class contact hours and effect sizes of psychological outcomes reported in published trials of MBSR, and did not find a systematic relationship between the two variables. Another review ( Vettese, Toneatto, Stea, Nguyen, & Wang, 2009 ) found no consistent relationship between amount of home mindfulness meditation practice and treatment outcomes. Taken together, these reviews do not support a dose-response relationship between level of treatment exposure and reported psychological benefits. Other factors, such as level of expertise of an instructor, may account for the psychological improvements observed following MBSR or other mindfulness-based interventions, and should be systematically measured in future studies.

Laboratory Research on Immediate Effects of Mindfulness Interventions

In addition to correlational and clinical intervention research on mindfulness, a third line of empirical research has examined the immediate effects of brief mindfulness interventions in controlled laboratory settings on a variety of emotion-related processes, including recovery from dysphoric mood, emotional reactivity to aversive or emotionally provocative stimuli, and willingness to return to or persist on an unpleasant task. Such laboratory studies have the advantage of more easily isolating mindfulness practice from other elements typically present in clinical intervention packages, thus allowing greater control over independent variables and stronger conclusions about causal effects.

Several studies have examined the immediate effects of mindfulness interventions on coping with dysphoric mood. Instructions to practice mindfulness of thoughts and feelings following negative mood induction were found to be more effective than rumination or no instruction in alleviating negative mood states in healthy university students ( Broderick, 2005 ), previously depressed individuals ( Singer & Dobson, 2007 ), and currently depressed individuals ( Huffziger & Kuehner, 2009 ), but not in one study of university students ( Kuehner, Huffziger, & Liebsch, 2009 ). As the latter authors noted, these differential findings may result in part from differences in methods used to induce mindfulness across studies (use of mindful self-focus statements on cards in Kuehner et al., 2009 versus audiotaped guided meditation instructions in Broderick, 2005 ), and/or differences in clinical status of study samples (e.g., beneficial effects of mindfulness may be more noticeable among clinical populations than among healthy subjects). It is unsurprising that mindfulness instructions would be more helpful in recovery from sad mood than rumination, which has been shown to be maladaptive ( Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991 ). Mindfulness also has been compared with other potentially adaptive mood-regulation strategies. Evidence is mixed with regard to the relative effects of mindfulness and distraction. Whereas two studies ( Huffziger & Kuehner, 2009 ; Singer & Dobson, 2007 ) found that mindfulness and distraction had equivalent effects on recovery from dysphoric mood, one study ( Broderick, 2005 ) found that mindfulness was more effective than distraction and another study ( Kuehner et al., 2009 ) found that distraction was more effective than mindfulness. Further studies are needed to clarify the relative effects of mindfulness and distraction on mood regulation, and whether those effects may be moderated by situational or personality factors. No published studies to date have compared the effects on recovery from dysphoric mood of mindfulness and cognitive reappraisal of distressing stimuli or situations.

Studies have also examined effects of mindfulness instructions on emotional responses to aversive or emotionally provocative stimuli. In a study by Arch and Craske (2006) , university students viewed a series of affectively-valenced pictures and rated their emotional responses to them, both before and after one of three sets of recorded instructions to which they were randomly assigned: focused breathing, unfocused attention, or worry. Whereas the other two groups showed a decrease in positive emotional response to neutral slides from pre-induction to post-induction, those assigned to the focused breathing condition maintained consistently positive responses to neutral slides. They also reported lower negative affect than the worry group in response to post-induction negative-valence slides and greater willingness to view negative slides than those in the unfocused attention condition, as indicated by viewing a greater number of additional optional negative slides. Findings of this study were extended by a recent study by Erisman and Roemer (2010) , which found that a brief mindfulness intervention, relative to a control condition, resulted in reduced emotion regulation difficulties and negative affect in response to an affectively-mixed film clip. Campbell-Sills, Barlow, Brown, and Hofmann (2006) randomly assigned patients with mood and anxiety disorders to instructions to either accept or suppress their emotions while viewing an emotionally provocative film. The two groups reported similar levels of subjective distress while watching the film but, relative to those in the suppression condition, the acceptance group displayed lower heart rate while viewing the film and reported less negative emotion during the post-film recovery period. The findings of these studies suggest that training in two key elements of mindfulness practice (focused awareness and acceptance) may reduce emotional reactivity to negative stimuli and increase willingness to remain in contact with them. There is preliminary work investigating the effects of brief mindfulness instructions on substance-related urges and substance use behavior. Bowen and Marlatt (2009) presented college smokers either brief mindfulness instructions or no instructions before and after exposure to a cue designed to elicit urges to smoke. Although there was no immediate effect on urge to smoke, mindfulness instructions resulted in significant decreases in smoking behavior during the next 7 days. As the authors noted, mindfulness training may alter responses to urges, rather than reducing urges. These findings were extended in another study that compared the effectiveness of using suppression versus a mindfulness-based strategy in coping with cigarette craving among a community sample of smokers ( Rogojanski, Vettese, & Antony, 2011 ). The study found that whereas both strategies reduced self-reported amount of smoking and increased self-efficacy associated with coping with cigarette craving, only those in the mindfulness condition reported significant decreases in negative affect and depressive symptoms and marginal decreases in nicotine dependence.

Research has also examined the efficacy of mindfulness as an emotion regulation strategy in response to a biological challenge, specifically to inhalations of carbon dioxide-enriched air (CO 2 challenge), a procedure that has frequently been used to create a laboratory analog of panic attacks ( Sanderson, Rapee, & Barlow, 1988 ). In a study by Feldner, Zvolensky, Eifert, and Spira (2003) , individuals who scored either high or low on a measure of emotional avoidance were instructed either to mindfully observe and accept or to try to suppress feelings during CO 2 challenge. High emotional avoidance participants reported higher anxiety than low emotional avoidance participants in the suppression condition, but not in the observation condition. Levitt, Brown, Orsillo, and Barlow (2004) randomized patients with panic disorder to one of three experimental conditions: a 10-minute audiotape describing a rationale for either suppressing or accepting one's emotions, or a neutral narrative, and then exposed them to CO 2 challenge. The acceptance group reported significantly lower levels of anxiety during the biological challenge than the other two groups and greater willingness to participate in a second challenge. One coping strategy commonly taught to patients with anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder, is breathing retraining, in which patients are taught to take deeper, slower breaths. Eifert and Heffner (2003) compared the effects of brief acceptance training, breathing retraining, and no training on responses to CO 2 challenge in undergraduates who scored high on a measure of anxiety sensitivity. Acceptance instructions led to less intense fear, fewer catastrophic thoughts, and lower behavioral avoidance (indicated both by latency between trials and reported willingness to return for another experimental session) than breathing retraining instructions or no instructions. Collectively, these studies suggest that mindful observation and acceptance of emotional responses may be an effective strategy for reducing subjective anxiety and behavioral avoidance in the face of physiological arousal, among highly anxiety sensitive or emotionally avoidant individuals and patients with panic disorder.

Laboratory studies of mindfulness have helped provide further insight into the functions of mindfulness and the potential processes through which mindfulness lead to positive psychological effects. The majority of the findings suggest that brief mindfulness training, whether in the form of a short, guided meditation practice or in the form of instructions to adopt an accepting attitude toward internal experiences, can have an immediate positive effect on recovery from dysphoric mood and level of emotional reactivity to aversive stimuli, consistent with the positive psychological effects reported in research on mindfulness-oriented intervention programs. The laboratory studies also suggest that it does not take extensive prior training in mindfulness to experience some immediate benefits of mindfulness training.

From a methodological standpoint, it is important that future studies more closely examine the extent to which a state of mindfulness is actually manipulated by the study instructions. Whereas most studies did include post-experimental manipulation checks on adherence to the training instructions, they did not explicitly assess the extent to which participants were able to be mindfully aware of their emotions or thoughts during or after exposure to a mood induction or a laboratory stressor. Research also could examine which training approaches or instructions (e.g. mindful breathing or mindfulness of emotions) are most effective at helping individuals regulate emotions in response to a stressor; whether there are key moderator variables such as pre-existing differences in dispositional mindfulness or coping styles; and whether effects differ by type of stressors or across different emotions. Research is also needed to compare the effects and mechanisms of mindfulness instructions with those of other documented emotion regulation strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal and distraction.

Mechanisms of Effects of Mindfulness Interventions

The studies reviewed so far indicate that measures of mindful awareness are related to various indices of psychological health and that mindfulness interventions have a positive impact on psychological health. The next natural question, then, is how this impact comes about. Several psychological processes, some of which may overlap, have been proposed as potential mediators of the beneficial effects of mindfulness interventions, including increases in mindful awareness, reperceiving (also known as decentering, metacognitive awareness, or defusion), exposure, acceptance, attentional control, memory, values clarification, and behavioral self-regulation.

Mindfulness training would be expected to increase scores on measures of mindfulness, and changes in mindfulness would be expected, in turn, to predict clinical outcomes. Research has found that mindfulness training leads to increases in self-reported trait mindfulness, assessed by the MAAS ( Anderson et al., 2007 ; Brown & Ryan, 2003 ; Carmody, Reed, Kristeller and Merriam, 2008 ; Michalak, Heidenreich, Meibert, & Schulte, 2008 ; Shapiro, Brown & Biegel, 2007 ), the CAMS-R ( Greeson et al., in press ) and the FFMQ ( Carmody & Baer, 2008 ; Robins, Keng, Ekblad, & Brantley, 2010 ; Shapiro et al., 2008 ), as well as TMS-assessed state mindfulness ( Carmody et al., 2008 ; Lau et al., 2006 ). Intervention-associated increases in trait mindfulness, assessed by the MAAS, the KIMS, the CAMS-R, and/or the FFMQ, have been shown to predict increases in sense of spirituality ( Carmody et al., 2008 ; Greeson et al., in press ), self-compassion ( Shapiro et al., 2007 ), and positive states of mind ( Bränström et al., 2010 ), and decreases in rumination ( Shapiro et al., 2007 ), trait anxiety ( Shapiro et al., 2007 ), risk of depressive relapse ( Michalak et al., 2008 ), posttraumatic avoidance symptoms ( Bränström et al., 2010 ), perceived stress ( Bränström et al., 2010 ; Shapiro et al., 2007 ), and overall psychological distress ( Carmody et al., 2008 ). A number of studies have also demonstrated that increases in trait mindfulness (again, assessed by the MAAS, the KIMS, and/or the FFMQ) statistically mediated the effects of mindfulness interventions on perceived stress (Nyklíček, & Kuipers, 2008; Shapiro et al., 2008 ), rumination ( Shapiro et al., 2008 ), cognitive reactivity ( Raes et al., 2009 ), quality of life (Nyklíček, & Kuipers, 2008), depressive symptoms ( Kuyken et al., 2010 ; Shahar, Britton, Sbarra, Figueredo, & Bootzin, 2010 ), and behavioral regulation ( Keng, Smoski, Robins, Ekblad, & Brantley, 2010 ). Lastly, one study ( Carmody & Baer, 2008 ) demonstrated that changes in FFMQ-assessed mindfulness at least partially mediated the relationships between amount of formal mindfulness practice and changes in psychological well being, perceived stress, and psychological symptoms.

Mindfulness training also is thought to increase metacognitive awareness, which is the ability to reperceive or decenter from one's thoughts and emotions, and view them as passing mental events rather than to identify with them or believe thoughts to be accurate representations of reality ( Hayes et al., 1999 ; Segal et al., 2002 ; Shapiro, Carlson, Astin, & Freeman, 2006 ). Increased metacognitive awareness has been hypothesized to lead to reductions in rumination ( Teasdale, 1999 ), a process of repetitive negative thinking that has been considered a risk factor for a number of psychological disorders ( Ehring & Watkins, 2008 ). Preliminary evidence suggests that mindfulness training leads to increases in metacognitive awareness ( Hargus et al., 2010 ; Teasdale et al., 2002 ) and reductions in rumination ( Jain et al., 2007 ; Ramel, Goldin, Carmona, & McQuaid, 2004 ), and that increased metacognitive awareness, or decentering, may in turn predict better clinical outcomes such as lower rates of depressive relapses ( Fresco, Segal, Buis, & Kennedy, 2007 ).

Exposure is another process that several authors have suggested may occur during mindfulness practice ( Baer, 2003 ; Kabat-Zinn, 1982 ; Linehan, 1993a ). By intentionally attending to experiences in a nonjudgmental and open manner, an individual may undergo a process of desensitization through which distressing sensations, thoughts and emotions that otherwise would be avoided become less distressing. One study has shown that participation in MBSR is associated with significant pre- to post-intervention increases in exposure ( Carmody, Baer, Lykins, & Olendzki, 2009 ). A closely-related process of change that has been highlighted in the literature is acceptance ( Hayes, 1994 ). Several studies reported that increases in experiential acceptance mediated the effects of ACT on a range of psychological outcomes, including workplace stress ( Bond & Bunce, 2000 ), smoking cessation ( Gifford et al., 2004 ), and functioning difficulties ( Forman et al., 2007 ).

Because mindfulness practices involve sustaining attention on the present-moment experience, as well as switching attention back to the present-moment experience whenever it wanders ( Bishop et al., 2004 ), mindfulness training may improve the ability to control attention, which may, in turn, influence other beneficial psychological outcomes. Several aspects of attention, each related to different neurobiological substrates, may be distinguished ( Posner & Petersen, 1990 ): orienting (the ability to direct attention towards a set of stimuli and sustain attention on it), alerting (the ability to remain vigilant or receptive towards a wide range of potential stimuli), and conflict monitoring (the ability to prioritize attention among competing cognitive demands/tasks). Using a variety of neuropsychological tasks, experimental studies have shown that mindfulness training is associated with improvements in orienting ( Jha, Krompinger, & Baime, 2007 ) and conflict monitoring ( Tang et al., 2007 ). Among experienced meditators, participation in an intensive mindfulness retreat has also been associated with improved alerting ( Jha et al., 2007 ). In addition, mindfulness training has been associated with improvements in sustained attention among both novice meditators ( Chambers, Lo, & Allen, 2008 ) and experienced meditators ( Valentine & Sweet, 1999 ), with one study demonstrating an association between intervention-related improvements in sustained attention and reductions in depressive symptoms ( Chambers et al., 2008 ). Overall, evidence suggests that mindfulness training may affect various subcomponents of attention, and that the specific subsystems affected may depend on the extent of previous meditation experience.

Another mechanism through which mindfulness training may influence psychological well-being is change in memory functioning. Two studies ( Hargus et al., 2010 ; Williams et al., 2000 ) have shown that mindfulness training reduces overgeneral autobiographical memory, a construct that has been associated with increased severity of depression and suicidality ( Kuyken & Brewin, 1995 ). Participation in mindfulness training has also been shown to buffer against decreases in working memory capacity (WMC) during high stress periods, with changes in WMC mediating the relationship between amount of mindfulness practice and reductions in negative affect ( Jha, Stanley, Kiyonaga, Wong, & Gelfand, 2010 ). In addition, brief mindfulness training has been shown to reduce memory for negative stimuli ( Alberts & Thewissen, in press ), a mechanism that may partly underlie the beneficial effects of mindfulness-based interventions on emotion functioning.

Finally, values clarification and improved behavioral self-regulation may be two additional avenues through which mindfulness training improves psychological well-being ( Gratz & Roemer, 2004 ; Shapiro et al., 2006 ). Staying present with thoughts and emotions in an objective, open and nonjudgmental manner may facilitate a greater sense of clarity with regard to one's values, and behaviors that are more consistent with those values. Higher levels of self-reported mindfulness are associated with self-reports of greater engagement in valued behaviors and interests ( Brown & Ryan, 2003 ) and of ability to engage in goal-directed behavior when emotionally upset ( Baer et al., 2006 ). In addition, mindfulness training has been found to lead to self-reported improved behavioral regulation in a nonclinical sample ( Robins et al., 2010 ) and reduced self-discrepancy, which is associated with adaptive self-regulation, among recovered depressed patients with a history of depression and suicidality ( Crane et al., 2008 ). In another study, values clarification was found to mediate partially the relationship between increased mindfulness/ reperceiving and decreased psychological distress in a sample of participants who underwent MBSR ( Carmody et al., 2009 ).

Areas in Need of Further Research

Understanding and quantification of mindfulness.

Because mindfulness is a construct that originates in Buddhism, and has only a brief history in Western psychological science, it is unsurprising that there is considerable challenge in defining, operationalizing, and quantifying it ( Grossman, 2008 ). Although a number of self-report inventories have been developed to assess mindfulness, they vary greatly in content and factor structure, reflecting a lack of agreement on the meaning and nature of mindfulness ( Brown, Ryan, & Creswell, 2007 ). Whereas some researchers consider mindfulness to be a one-dimensional construct referring specifically to paying attention to the present-moment experience (e.g., Brown & Ryan, 2003 ; Carmody, 2009 ), others argue that qualities such as curiosity, acceptance, and compassion are inherent to mindfulness ( Baer & Sauer, 2009 ; Feldman et al., 2007 ; Lau et al., 2006 ). Further collaborative inquiry is needed so that researchers can reach a general agreement on the nature and meaning of mindfulness, or at least clarify and specify which aspects of mindfulness are being addressed in a particular study.

Several issues pertaining to the assessment of mindfulness are also worth highlighting here. First, individual responses to questionnaire items may vary as a function of differential understanding of the questionnaire items ( Grossman, 2008 ), which may depend on the extent of an individual's exposure to the idea or practice of mindfulness. One study demonstrated that the factor structure of the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory changed within the same group of respondents from just before to just after attending meditation retreats of 3 to 10 days ( Buchheld, Grossman, & Wallach, 2001 ). Further research is clearly needed to improve the construct validity of self-report mindfulness questionnaires, in part via reducing potential variability in item functioning across meditators and non-meditators. A second issue concerns limitations in the use of self-report measures of mindfulness, which rely on the assumption that mindfulness is assessable by declarative knowledge ( Brown et al., 2007 ). It is not known how well self-reports of mindfulness correspond with actual experiences in daily life. To make the matter more complicated, there is an inherent paradox in using frequency of attention lapses as an index of mindfulness because the ability to detect such lapses is contingent upon one's overall level of mindfulness ( Van Dam, Earlywine, & Borders, 2010 ; Van Dam, Earleywine, & Danoff-Burg, 2009 ). One way in which the validity of self-report questionnaires can be improved is by developing performance-based measures of mindfulness against which they can be calibrated, or which can be used in multi-method assessment of the construct ( Garland & Gaylord, 2009 ).

Specificity of Effects of Mindfulness Interventions

Little is yet known regarding for whom and under what conditions mindfulness training is most effective, but there is some preliminary evidence to suggest that its effectiveness may vary as a function of individual differences. Cordon, Brown, and Gibson (2009) found that participation in MBSR resulted in greater reduction in perceived stress for individuals with an insecure attachment style than for securely attached individuals. Another recent study ( Shapiro, Brown, Thoresen, & Plante, 2011 ) showed that trait mindfulness moderated the effects of MBSR. Specifically, compared to controls, participants with higher levels of baseline trait mindfulness demonstrated greater improvements in mindfulness, subjective well-being, empathy, and hope, and larger decreases in perceived stress up to one year post-intervention. MBCT is effective for reducing depressive relapses among remitted depressed patients with a history of three or more depressive episodes, but not among patients with two previous episodes (e.g., Teasdale et al., 2000 ; Ma & Teasdale, 2004 ). In light of these considerations, several researchers have cautioned against the indiscriminate application of mindfulness as a general-purpose, “cure-all” therapeutic technique, and instead advocated for a problem formulation approach in the use of mindfulness techniques for treating psychological conditions ( Kocovski, Segal, Battista, & Didonna, 2009 ; Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 2003 ). In order to maximize the effectiveness and clinical utility of mindfulness interventions, sufficient attention needs to go into tailoring them to fit the needs of specific populations and psychological conditions. For example, treatment of disorders that primarily involve a deficit in attentional abilities, like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), may require that greater focus be placed on the attentional aspect of mindfulness training. On the other hand, treatment of disorders that tend to involve excessive shame and guilt, such as eating disorders, may benefit from greater treatment emphasis on the acceptance and self compassion aspects of mindfulness. Finally, given that mindfulness training has been increasingly integrated with a variety of psychotherapeutic techniques (e.g., Linehan, 1993a ), it is important that future research examine how mindfulness works alongside these psychotherapeutic techniques.

Other Potential Applications of Mindfulness Interventions

Mindfulness-oriented interventions have been shown to improve psychological health in nonclinical populations and effectively treat a range of psychological and psychosomatic conditions. There may be additional therapeutic applications of mindfulness training. Researchers have reported promising results in pilot trials of mindfulness interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ( Zylowska et al., 2008 ), bipolar disorder ( Miklowitz et al., 2009 ; Weber et al., 2010 ; Williams et al., 2008 ), panic disorder ( Kim et al., 2010 ), generalized anxiety disorder ( Evans et al., 2008 ; Craigie, Rees, Marsh, & Nathan, 2008 ; Roemer, Orsillo, & Salters-Pedneault, 2008 ), eating disorders ( Baer, Fischer, & Huss, 2005 ; Kristeller & Hallett, 1999 ), psychosis ( Chadwick, Taylor, & Abba, 2005 ), and alcohol and substance use problems ( Bowen et al., 2006 ; Witkiewitz et al., 2005 ). While the data is overall preliminary and requires further validation, the results are promising. Researchers have also begun to investigate the application of mindfulness techniques within specific populations and settings, such as children ( Bogels, Hoogstad, van Dun, de Schutter, & Restifo, 2008 ; Lee, Semple, Rosa, & Miller, 2008 ; Napoli, Krech, & Holley, 2005 ), adolescent psychiatric outpatients ( Biegel, Brown, Shapiro, & Schubert, 2009 ), parents ( Altmaier & Maloney, 2007 ; Bögels et al., 2008 ; Singh et al., 2006 ), school teachers ( Napoli, 2004 ), elderly and their caregivers ( Epstein-Lubow, McBee, Darling, Armey, & Miller, in press ; McBee, 2008 ; Smith, 2004 ), prison inmates ( Bowen et al., 2006 ; Samuelson, Carmody, Kabat-Zinn, & Bratt, 2007 ), and socio-economically disadvantaged individuals ( Hick & Furlotte, 2010 ).