Essay Papers Writing Online

Exploring the impact of community service – a comprehensive essay sample.

Community service plays a vital role in shaping individuals and communities. Engaging in service activities not only helps those in need but also has a profound impact on the volunteers themselves. By giving back to the community, individuals can develop empathy, leadership skills, and a sense of responsibility towards society.

In this essay sample, we will explore inspiring examples of community service projects and provide tips on how you can get involved in making a difference. From volunteering at local shelters to organizing charity events, there are countless ways to contribute to your community and create a positive impact on the world around you. Let’s delve into the world of community service and discover the power of giving back!

Community Service Essay Sample

Community service is a valuable activity that allows individuals to give back to their communities. It provides an opportunity to make a positive impact on the lives of others while also developing important skills and values. Here is a sample essay that highlights the benefits of community service and reflects on personal experiences.

Introduction: Community service is an essential part of being an active and engaged member of society. It not only benefits the community but also helps individuals grow and learn. Through my involvement in various community service projects, I have seen firsthand the power of giving back and the joy it brings to both the recipient and the volunteer.

Body: One example of the impact of community service is the work I did at a local soup kitchen. By volunteering at the soup kitchen, I was able to help provide meals to those in need and offer a listening ear to those who were struggling. This experience taught me the importance of empathy and compassion, and showed me how even small acts of kindness can make a big difference in someone’s life.

Another example of the benefits of community service is the time I spent tutoring children at a local elementary school. Through this experience, I was able to help students improve their academic skills and build their confidence. I also gained a greater appreciation for the value of education and the impact it can have on a child’s future.

Conclusion: In conclusion, community service is a valuable and rewarding activity that allows individuals to make a positive impact on their communities. Through my experiences with community service, I have learned important lessons about empathy, compassion, and the power of giving back. I am grateful for the opportunities I have had to volunteer and look forward to continuing to serve my community in the future.

Inspiring Examples and Tips

When it comes to community service, there are countless inspiring examples that can motivate you to get involved. Whether it’s volunteering at a local shelter, organizing a charity event, or tutoring underprivileged children, these acts of service can make a real impact on the community.

Here are a few tips to help you get started on your community service journey:

1. Find a Cause You’re Passionate About: Choose a cause that resonates with you personally. When you care deeply about the issue you’re working on, your efforts will be more meaningful and impactful.

2. Start Small: You don’t have to take on huge projects right away. Start small by volunteering for a few hours a week or helping out at a local event. Every little bit helps.

3. Collaborate with Others: Community service is often more effective when done as a team. Reach out to friends, family, or colleagues to join you in your efforts.

4. Stay Consistent: Make a commitment to regularly engage in community service. Consistency is key to making a lasting impact.

5. Reflect on Your Impact: Take the time to reflect on how your service is making a difference. Celebrate your achievements and learn from your challenges.

By following these tips and drawing inspiration from others, you can make a meaningful contribution to your community through service. Get started today and see the positive impact you can have!

Why Community Service Matters

Community service is an essential component of a well-rounded individual. It provides an opportunity to give back to society, make a positive impact on the community, and develop valuable skills and experiences. Engaging in community service helps individuals cultivate empathy, compassion, and a sense of civic responsibility. By volunteering and helping others, individuals can learn to appreciate the needs of others and work towards creating a more inclusive and supportive society.

Furthermore, community service allows individuals to build connections with others and foster a sense of community. Through collaboration and teamwork, volunteers can develop important social and communication skills that are valuable in all aspects of life. Community service also provides a way to explore new interests, gain new perspectives, and expand one’s horizons.

Moreover, community service is a way to address pressing social issues and contribute to positive change. By participating in community service projects, individuals can make a tangible difference in the lives of others and work towards creating a more just and equitable world. Community service is a powerful tool for promoting social justice, equality, and human rights.

In conclusion, community service matters because it helps individuals grow personally, develop important skills, build meaningful relationships, and contribute to a better society. Engaging in community service is a fulfilling and impactful way to make a difference in the world and leave a lasting legacy of service and compassion.

Benefits of Engaging in Community Service

Engaging in community service offers a wide range of benefits both for the individual and the community as a whole.

1. Personal Growth: Community service allows individuals to step out of their comfort zones, develop new skills, and gain valuable life experiences. It helps enhance empathy, compassion, and understanding of diverse perspectives.

2. Social Connections: By participating in community service activities, individuals can build strong relationships with like-minded individuals and expand their social network. It provides opportunities to collaborate with others and work towards common goals.

3. Skill Development: Community service offers a platform for individuals to develop and hone various skills such as leadership, communication, problem-solving, and teamwork. These skills are transferable to other aspects of life.

4. Civic Engagement: Engaging in community service promotes active citizenship and a sense of responsibility towards one’s community. It allows individuals to contribute to positive change and make a meaningful impact on society.

5. Personal Fulfillment: Giving back to the community and helping those in need can bring a sense of fulfillment and purpose to individuals. It provides a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction knowing that one has made a positive difference in the lives of others.

Overall, engaging in community service not only benefits the community by addressing various social issues but also contributes to personal growth, social connections, skill development, civic engagement, and personal fulfillment.

How to Choose the Right Community Service Project

When deciding on a community service project, it is important to consider your interests, skills, and the needs of your community. Here are some tips to help you choose the right project:

- Identify your passion: Think about what causes or issues you feel strongly about. Whether it’s helping the environment, supporting education, or assisting the elderly, choosing a project that aligns with your passions will keep you motivated and engaged.

- Evaluate your skills: Consider what skills you have to offer. Are you good at organizing events, teaching, or fundraising? Select a project that allows you to utilize your strengths and make a meaningful impact.

- Assess the community’s needs: Research and assess the needs of your community. Talk to local organizations, schools, or community leaders to identify areas where help is most needed. By addressing pressing needs, your project will have a greater impact.

- Consider the time commitment: Be realistic about the time you can dedicate to a community service project. Choose a project that fits into your schedule and allows you to make a consistent contribution over time.

- Collaborate with others: Consider teaming up with friends, classmates, or colleagues to take on a community service project together. Working as a team can help divide tasks, share responsibilities, and create a stronger impact.

By following these tips and considering your interests, skills, and community needs, you can choose the right community service project that aligns with your values and makes a positive difference in your community.

Steps to Writing an Effective Community Service Essay

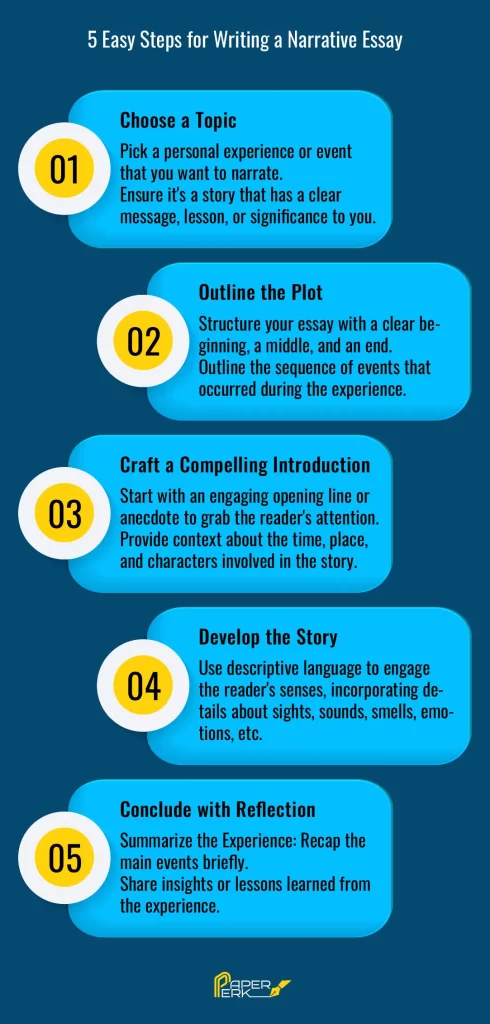

If you are tasked with writing a community service essay, follow these steps to ensure it is impactful and engaging:

- Choose a meaningful community service experience: Select a service project that has had a significant impact on you or your community.

- Reflect on your experience: Take time to think about the lessons learned, challenges faced, and personal growth from the service project.

- Outline your essay: Create a clear outline that includes an introduction, body paragraphs detailing your experiences, and a conclusion that ties everything together.

- Show, don’t tell: Use descriptive language and vivid examples to bring your community service experience to life for the reader.

- Highlight your personal growth: Discuss how the community service experience has shaped your values, beliefs, and future goals.

- Connect your experience to the broader community: Share how your service has impacted those around you and the community as a whole.

- Revise and edit your essay: Review your essay for clarity, coherence, and grammar errors. Make revisions as needed to strengthen your message.

- Seek feedback: Ask someone you trust to read your essay and provide constructive feedback for improvement.

- Finalize your essay: Make any final adjustments and ensure your essay is polished and reflects your authentic voice.

Community Service Essay Structure

When writing a community service essay, it is important to follow a structured approach to ensure that your message is clear and impactful. Here is a recommended structure to help you organize your thoughts and create a compelling essay:

- Introduction: Start with a strong opening sentence that grabs the reader’s attention. Introduce the topic of community service and provide some context for your personal experience.

- Background Information: Briefly explain what community service means to you and why you chose to engage in it. Provide background information on the organization or cause you volunteered for.

- Personal Experience: Share specific examples of your community service activities. Describe the impact you made, challenges you faced, and lessons you learned. Highlight any skills or qualities that you developed through your volunteer work.

- Reflection: Reflect on how your community service experience has influenced your personal growth and perspective on the world. Discuss any changes in your attitudes or values as a result of your volunteer work.

- Impact: Describe the positive impact your community service has had on others. Share stories of individuals or communities that benefitted from your efforts.

- Conclusion: Summarize the key points of your essay and reiterate the importance of community service. End with a powerful closing statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

By following this structure, you can effectively communicate the value of community service and inspire others to make a difference in their communities. Remember to be sincere, reflective, and passionate in your writing to convey the true essence of your volunteer experience.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Community Service — Reflective On Community Service

Reflective on Community Service

- Categories: Community Service Personal Growth and Development

About this sample

Words: 608 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 608 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, 1. personal growth and development, 2. academic enhancement, 3. social responsibility and civic engagement, 4. challenges and lessons learned, 5. future implications.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1726 words

1 pages / 575 words

2 pages / 740 words

2 pages / 830 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Community Service

In every community service and service learning there are hundreds human being more just like it’s filled with kind-hearted individuals volunteering their time to better our communities. Individual participation represent the [...]

Villanova University, renowned for its commitment to academic excellence and Augustinian values, stands out in its unique approach to education. It emphasizes not only intellectual growth but also the importance of community and [...]

The act of helping the poor and needy holds profound significance in fostering a just and compassionate society. As we navigate the complexities of modern life, it becomes increasingly imperative to address the challenges faced [...]

Education is a fundamental right that every individual should have access to, yet many low-income families struggle to provide adequate education for their children. The purpose of this community service project proposal essay [...]

Americorps is a federally-funded national service program in the United States that aims to address critical community needs through direct service. Established in 1994, Americorps has become an integral part of America's [...]

Nowadays, many people have to learn as many skills as they can, so that they can get the jobs that they find interesting. The government requires students to perform minimum of 15 hours community service to graduate from high [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Arts & Culture

Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

Community Engagement Matters (Now More Than Ever)

Data-driven and evidence-based practices present new opportunities for public and social sector leaders to increase impact while reducing inefficiency. But in adopting such approaches, leaders must avoid the temptation to act in a top-down manner. Instead, they should design and implement programs in ways that engage community members directly in the work of social change.

- order reprints

- related stories

By Melody Barnes & Paul Schmitz Spring 2016

In October 2010, three men—Chris Christie, governor of New Jersey; Cory Booker, who was then mayor of Newark, N.J.; and Mark Zuckerberg, founder and CEO of Facebook—appeared together on The Oprah Winfrey Show to announce an ambitious reform plan for Newark Public Schools. On the show, Zuckerberg pledged a $100 million matching grant to support the goal of making Newark a model for how to turn around a failing school system. This announcement was the first time that most Newark residents heard about the initiative. And that wasn’t an accident.

Christie and Booker had adopted a top-down approach because they thought that the messy work of forging a consensus among local stakeholders might undermine the reform effort. 1 They created an ambitious timeline, installed a board of philanthropists from outside Newark to oversee the initiative, and hired a leader from outside Newark to serve as the city’s superintendent of schools.

The story of school reform in Newark has become a widely cited object lesson in how not to undertake a social change project. Even in the highly charged realm of education reform, the Newark initiative stands out for the high level of tension that it created. Instead of generating excitement among Newark residents about an opportunity to improve results for their kids, the reform plan that emerged from the 2010 announcement sparked a massive public outcry. At public meetings, community members protested vigorously against the plan. In 2014, 77 local ministers pleaded with the governor to drop the initiative because of the toxic environment it had created. Ras Baraka, who succeeded Booker as mayor of Newark, made opposition to the reform plan a central part of his election campaign. The money that Zuckerberg and others contributed to support the reform plan is now gone, and the initiative faces an uncertain future.

“When Booker and Christie decided to do this without the community, that was their biggest mistake,” says Howard Fuller, former superintendent of the Milwaukee Public Schools and a prominent school reform leader. Instead of unifying Newark residents behind a shared goal, the Booker-Christie initiative polarized the city.

Zuckerberg, for his part, seems to have learned a lesson. In May 2014, he and his wife, Priscilla Chan, announced a $120 million commitment to support schools in the San Francisco Bay Area. In doing so, they emphasized their intention to “[listen] to the needs of local educators and community leaders so that we understand the needs of students that others miss.” 2

Another project launched in Newark in 2010—the Strong Healthy Communities Initiative (SHCI) —has had a much less contentious path. Both Booker and Baraka have championed it. Sponsored by Living Cities (a consortium of 22 large foundations and financial institutions that funds urban revitalization projects), SHCI operates with a clear theory of change: To achieve better educational outcomes for children, policymakers and community leaders must address the environmental conditions that help or hinder learning.

If kids are hungry, sick, tired, or under stress, their ability to learn will suffer. According to an impressive array of research, such conditions lie at the forefront of parents’ and kids’ minds, and they strongly affect kids’ chances of success in school. Inspired by this research, SHCI leaders have taken steps to eliminate blighted housing conditions, to build health centers in schools, and to increase access to high-quality food for low-income families.

SHCI began as an effort led by philanthropists and city leaders, but since then it has shifted its orientation to engage a broader crosssection of community stakeholders. Over time, those in charge of the initiative have built partnerships with leaders from communities and organizations throughout Newark. “We avoid a top-down approach as much as possible,” says Monique Baptiste-Good, director of SHCI. “We start with community and then engage established leaders. When we started, a critical decision was to operate like a campaign and not institutionalize as an organization. We fall to the background and push our partners’ capacity forward. Change happens at the pace people can adapt.”

Challenges related to housing and health may seem to be less controversial than school reform, but these issues generate considerable heat as well. (Consider, for example, the controversy that surrounds efforts by the Obama administration to change nutrition standards for children.) In any event, the crucial lesson here is one that spans a wide range of issue areas: How policymakers and other social change leaders pursue initiatives will determine whether those efforts succeed. If they approach such efforts in a top-down manner, they are likely to meet with failure. (We define a top-down approach as one in which elected officials, philanthropists, and leaders of other large institutions launch and implement programs and services without the full engagement of community leaders and intended beneficiaries.)

This lesson has become more acutely relevant in recent years. Disparities in education, health, economic opportunity, and access to justice continue to increase, and the resources available to confront those challenges have not kept pace with expanding needs. As a consequence, leaders in the public and nonprofit sectors are looking for better ways to invest those resources. At the same time, the increasing use of data-driven practices raises the hope that leaders can make progress on this front. These practices include, most notably, evidence-based programs in which there is a proven correlation between a given intervention and a specific impact. But they also include collective impact initiatives and other efforts that employ data to design and evaluate solutions. (In this article, we will use the term “data-driven” to refer to the full range of such practices.)

In rolling out programs that draw on such research, however, leaders must not neglect other vitally important aspects of social change. As the recent efforts in Newark demonstrate, data-driven solutions will be feasible and sustainable only if leaders create and implement those solutions with the active participation of people in the communities that they target.

The Promise of Data

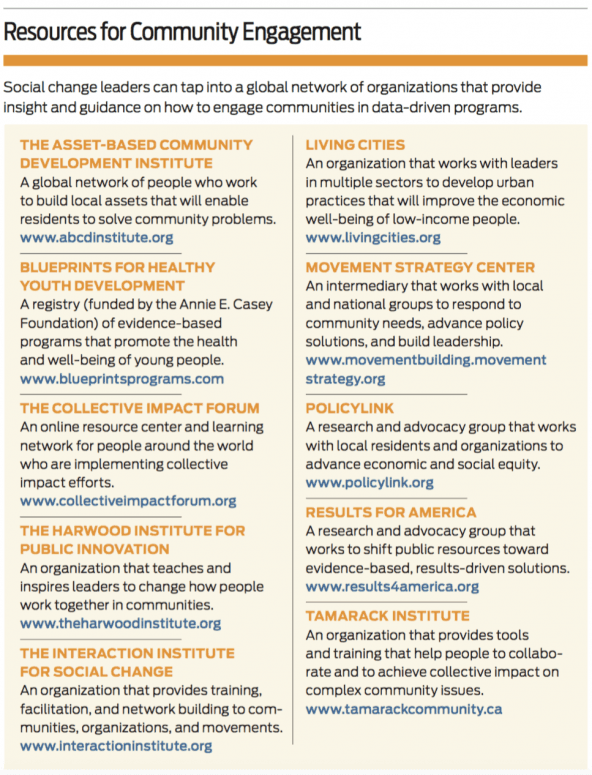

Under the sponsorship of an organization called Results for America , we recently undertook a research project that focused on how leaders can and should pursue data-driven social change efforts. For the project, we interviewed roughly 30 city administrators, philanthropists, nonprofit leaders, researchers, and community builders from across the United States. We began this research with a simple premise: Social change leaders now have an unprecedented ability to draw on data-driven insight about which programs actually lead to better results.

Leaders today know that babies born to mothers enrolled in certain home visiting programs have healthier birth outcomes. (The Nurse-Family Partnership , which matches first-time mothers with registered nurses, is a prime example of this type of intervention. 3 ) They know that students in certain reading programs reach higher literacy levels. ( Reading Partners , for instance, has shown impressive results with a program that provides one-on-one reading instruction to struggling elementary school students. 4 ) They know that criminal offenders who enter job-training and support programs when they leave prison are less likely to re-offend and more likely to succeed in gaining employment. ( The Center for Employment Opportunities has achieved such outcomes by offering life-skills education, short-term paid transitional employment, full-time job placement, and post-placement services. 5 )

Results for America, which launched in 2012, seeks to enable governments at all levels to apply data-driven approaches to issues related to education, health, and economic opportunity. In 2014, the organization published a book called Moneyball for Government . (The title is a nod to Moneyball , a book by Michael Lewis that details how the Oakland A’s baseball club used data analytics to build championship teams despite having a limited budget for player salaries.) The book features contributions by a wide range of policymakers and thought leaders (including Melody Barnes, a co-author of this article). The editors of Moneyball for Government , Jim Nussle and Peter Orszag, outline three principles that public officials should follow as they pursue social change:

- “Build evidence about the practices, policies, and programs that will achieve the most effective and efficient results so that policymakers can make better decisions.

- “Invest limited taxpayer dollars in practices, policies, and programs that use data, evidence, and evaluation to demonstrate they work.

- “Direct funds away from practices, policies, and programs that consistently fail to achieve measurable outcomes.” 6

These concepts sound simple. Indeed, they have the ring of common sense. Yet they do not correspond to the current norms of practice in the public and nonprofit sectors. According to one estimate, less than 1 percent of federal nondefense discretionary spending goes toward programs that are backed by evidence. 7 In a 2014 report, Lisbeth Schorr and Frank Farrow note that the influence of evidence on decision-making—“especially when compared to the influence of ideology, politics, history, and even anecdotes”—has been weak among policymakers and social service providers. 8 (Schorr is a senior fellow at the Center for the Study of Social Policy , and Farrow is director of the center.)

That needs to change. There is both an economic and a moral imperative for adopting data-driven approaches. Given persistently limited budgets, public and nonprofit leaders must direct funds to programs and initiatives that use data to show that they are achieving impact. Even if unlimited funds were available, moreover, leaders would have a responsibility to design programs that will deliver the best results for beneficiaries.

The Need for “Patient Urgency”

The inclination to move fast in creating and implementing data-driven programs and practices is understandable. After all, the problems that communities face today are serious and immediate. People’s lives are at stake. If there is evidence that a particular intervention can (for example) help more children get a healthy start in life—or help them read at grade level, or help them develop marketable skills—then setting that intervention in motion is pressingly urgent.

But acting too quickly in this arena entails a significant risk. All too easily, the urge to initiate programs expeditiously translates into a preference for top-down forms of management. Leaders, not unreasonably, are apt to assume that bottom-up methods will only slow the implementation of programs that have a record of delivering positive results.

A former director of data and analytics for a US city offers a cautionary tale that illustrates this idea. “We thought if we got better results for people, they would demand more of it,” she explains. “Our mayor communicated in a paternal way: ‘I know better than you what you need. I will make things better for you. Trust me.’ The problem is that they didn’t trust us. Relationships matter. Not enough was done to ask people what they wanted, to honor what they see and experience. Many of our initiatives died—not because they didn’t work but because they didn’t have community support.”

To win such support, policymakers and other leaders must treat community members as active partners. “Doing to us, not with us, is a recipe for failure,” says Fuller, who has deep experience in building community-led coalitions. “If we engage communities, then we have a solution and we have the leadership necessary to demand that solution and hold people accountable for it.” Engaging a community is not an activity that leaders can check off on a list. It’s a continuous process that aims to generate the support necessary for long-term change. The goal is to encourage intended beneficiaries not just to participate in a social change initiative but also to champion it.

“This work takes patient urgency,” Fuller argues. “If you aren’t patient, you only get illusory change. Lasting change is not possible without community. You may be gone in 5 or 10 years, but the community will still be there. You need a sense of urgency to push the process forward and maintain momentum.” The tension between urgency and patience is a productive tension. Navigating that tension allows leaders and community members to achieve the right level of engagement.

Rich Harwood, president of the Harwood Institute for Public Innovation , makes this point in a post on his website: “Understanding and strengthening a community’s civic culture is as important to collective efforts as using data, metrics and measuring outcomes. … A weak civic culture undermines the best intentions and the most rigorous of analyses and plans. For change to happen, trust and community ownership must form, people need to engage with one another, and we need to create the right underlying conditions and capabilities for change to take root and spread.” 9

Factors of Engagement

We have identified six factors that are essential to building community support for data-driven solutions. These factors are complementary. Social change initiatives that incorporate each factor will tend to have a greater chance of success.

Organizing for ownership | In many cases, efforts to engage affected communities take place after leaders have designed and launched data-driven initiatives. But engagement should begin earlier so that community members will have an incentive to support the initiative.

One of the biggest mistakes that social change leaders make is failing to differentiate between mobilizing and organizing. Mobilizing is about recruiting people to support a vision, cause, or program. In this model, a leader or an organization is the subject that makes decisions, and community members are the passive object of those decisions. Organizing, on the other hand, is about cultivating leaders, identifying their interests, and enabling them to lead change. Here, community members are the subject of the work: They collaborate on making decisions. At its best, community engagement involves working with a variety of leaders—those at the grass tops and those at the grass roots—to ensure that an effort has the support necessary for long-term success.

The International Association for Public Participation has developed a spectrum that encompasses various forms of engagement. 10 At one end of the spectrum is informing , which might take the form of a mailing or a town-hall meeting in which professional leaders describe a new change effort (and perhaps ask for feedback about it). At the other end of the spectrum is empowerment , which supports true self-determination for participants. One organization that practices empowerment is the Family Independence Initiative (FII) in Oakland, Calif. Instead of focusing on delivery of social services, FII invests in supporting the capacity and ingenuity of poor families. (Through an extensive data-collection process at six pilot sites, FII has demonstrated that participating families can achieve significant economic and social mobility.)

The further an initiative moves toward the empowerment end of the spectrum, the more community members will feel a sense of ownership over it, and the more inclined they will be to advocate for it. Of course, it’s not always possible to operate at the level of full empowerment. But initiative leaders need to be clear about where they are in the spectrum, and they need to deliver the level of engagement they promise.

John McKnight and Jody Kretzmann, co-directors of the Asset- Based Community Development Institute at Northwestern University and authors of the classic community-building guide Building Communities From the Inside Out , argue that too often “experts” undermine the natural leadership and the sense of connectedness that exist in communities as assets for solving problems. At a recent international conference of community builders, McKnight and Kretzmann suggested that when providers work with communities they should ask these questions: “What can community members do best for themselves and each other? What can community members do best if they receive some support from organizations? What can organizations do best for communities that people can’t do for themselves?”

It’s important, in other words, to view community members as producers of outcomes, not just as recipients of outcomes. Professional leaders must recognize and respect the assets that community members can bring to an initiative. If the goal is to help children to read at grade level or to help mothers to have healthy birth outcomes, then leaders should consider the roles that family members, friends, and neighbors can play in that effort. A mother who watches kids from her neighborhood after school is a kind of youth worker. The elder who checks in on a young mother is a kind of community health worker. Supporting these community members—not just for their voice but also for their ability to produce results—is crucial to the pursuit of lasting change.

Engaging grassroots leaders requires intention and attention. “If we commit to engaging community members, we have to set them up for success. We have to orient them to our world and engage in theirs,” says Angela Frusciante, knowledge development officer at the William Caspar Graustein Memorial Fund . “We need to work with leaders to make meaning out of the data about their communities: Where do they see their own stories in the data? How do they interpret what they see? Remember, data is information about people’s lives.”

Allowing for complexity | Leaders must adapt to the complex system of influences that bear on the success of any data-driven solution. Patrick McCarthy, president of the Annie E. Casey Foundation , made this point forcefully at a 2014 forum: “An inhospitable system will trump a good program—every time, all the time.” 11 Instead of trying to “plug and play” a solution, leaders should consider the cultural context in which people will implement that solution. They should develop a deep connection to the communities they serve and a deep understanding of the many constituencies that can affect the success of their efforts.

One pitfall of data-driven social change work is that it sometimes provides little scope for complexity—for the way that multiple factors are intertwined in peoples’ lives. Evidence-based approaches can “[privilege] single-level programmatic interventions,” Schorr and Farrow note. “These [programs] are most likely to pass the ‘what works?’ test within the controlled conditions of the experimental evaluation. Reliance on this hierarchy also risks neglecting or discouraging interventions that cannot be understood through this methodology and sidelining complex, multi-level systemic solutions that may be very effective but require evidence-gathering methods that rank lower in the evidence hierarchy.” 12 Those who implement data-driven practices, therefore, need to treat them not as miracle cures but as important elements within a larger ecosystem.

The need to reckon with complexity is one reason that the collective impact model has gained popularity in many communities. 13 In a collective impact initiative, organizations and community members work together at a systemic level to achieve a complex community-wide goal. They work to connect each intervention to other programs, organizations, and systems (including family and neighborhood systems) that influence the lives of beneficiaries. It’s not likely that a single intervention, pursued in isolation, will create lasting change. Delivering an evidence-based reading program for children in elementary school may have a positive impact on literacy outcomes, for example, but the long-term sustainability of that intervention will depend on the health, safety, home environment, and economic well-being of those children.

Working with local institutions | Often the pursuit of a data-driven strategy involves shifting funds away from work that isn’t demonstrating success. Taking that step is sometimes necessary, but when leaders shift funds, they must be careful not to harm the community they aim to help. Such harm can occur, for example, when they underfund programs with deep community connections, when they eliminate vital services for which there is no good alternative, or when they import programs from outside the community that destabilize existing providers.

A decision to shift funds can also generate otherwise avoidable resistance from natural allies. An official from a local foundation recounts an episode that happened in her city: “Our mayor got excited about a college access program that he visited in another city and raised money to bring it here. The existing college access programs had trouble raising money once the mayor was competing with them to raise funds, and they started going out of business. The new initiative never gained community support.” According to this official, the mayor’s actions were ultimately counterproductive. “There is now less happening for the people served,” she says.

In some cases, moreover, local organizations have built up social capital that creates an enabling environment for data-driven interventions to succeed. A community center that has fostered active participation among parents, for example, might be an important asset for a data-driven effort to improve third-grade reading scores.

For these reasons, it’s often better to encourage existing grantees to adopt data-driven practices than to defund those groups. Carol Emig, president of Child Trends , a nonprofit research organization that focuses on issues related to children and families, argues for this approach: “Instead of telling a city or foundation official that they have to defund their current grantees because they are not evidence-based, funders can tell long-standing grantees that future funding will be tied at least in part to retooling existing programs and services so that they have more of the elements of successful programs.” 14 The mayor who brought an outside college access program to his city, for example, might have had more success if he had worked with local providers to implement a variation of the program.

Collaborating with local groups takes effort. Funders must start by assessing whether a grantee has a solid grounding in the community, experience in the relevant issue area, and a willingness to alter its practice. Nicole Angresano, vice president of community impact at the United Way of Greater Milwaukee and Waukesha County , explains how her organization works with grantees to improve performance: “We assess the state of the organization’s relationships.” Her group looks in particular at the level of trust that grantees have earned within their community. “If that [trust] is high, we’ll build capacity and partner with them to improve results,” she says.

Applying an equity lens | Jim Collins, in his management strategy book Good to Great, argues that effective leaders “ first [get] the right people on the bus … and the right people in the right seats—and then they [figure] out where to drive it.” 15 Too often, social change efforts don’t engage the right mix of people. When leaders seek to bring data-driven solutions to low-income communities and communities of color, they must take care to apply an equity lens to this work. Members of those communities not only should be “at the table”; they should hold leadership positions as well.

Many groups apply an equity lens to their initiatives downstream: They analyze disaggregated data to identify disparities, and then they adopt strategies to reduce those disparities. That’s important, but it’s even more important to apply an equity lens upstream—in the places where people make critical decisions about an initiative. The ranks of board members, staff members, advisors, and partners must include members of the beneficiary community. “Some leaders just want black and brown people to carry signs,” says Fuller. “They don’t want them to actually lead, to have a voice, to have self-determination.”

It’s not enough to bring a diverse set of leaders together. Creating a culture in which those leaders can collaborate effectively is also necessary. Applying an equity lens involves working to build trust among participants and working to ensure that all of them can engage fully in an initiative. Achieving equitable participation, moreover, requires a commitment to hearing all voices, valuing all perspectives, and taking swift action to correct disparities of representation. And although this process cannot eliminate power dynamics, leaders should strive to mitigate the effects of power differences.

Leaders should also apply an equity lens to the selection of organizations that will receive funding to implement data-driven work. One way to do so is to establish a continuum of eligibility that allows groups—those that are ready to implement data-driven practices as well as those that will require capacity-building support to reach that level—to apply for funding at different stages of an initiative. That approach can enable the inclusion of small organizations that are led by people of color or by other under-represented members of a community.

Building momentum | The work of engaging communities, as we noted earlier, requires a sense of patient urgency. According to people we interviewed for our project, it often takes one to two years to complete the core planning and relationship building that are necessary to launch an initiative that features substantial community engagement. That is all the more true when the initiative incorporates data-driven approaches.

For this reason, achieving significant results within a typical two-to-three-year foundation grant cycle can be challenging. Similarly, it can be difficult to pursue lasting change within a time frame that suits the needs of public sector leaders. Government agencies usually operate in one-year budget cycles, and elected officials want to see results within a four-year election cycle. So when public agencies take the lead on an initiative, it’s incumbent on philanthropic funders and other partners to create external pressure that will lend staying power to the initiative.

Another solution to this problem is to build momentum up front by achieving quick wins—early examples of demonstrated progress. Quick wins will encourage grantmakers to invest in an initiative and will help meet the political needs of public officials. In addition, quick wins will keep resistance from building. If an initiative hasn’t shown any results for two to three years, the forces of the status quo will reassert themselves, and opponents will eagerly claim that the initiative is failing.

Early wins will also help a community build a narrative of success that can replace existing narratives that dwell on the apparent intractability of social problems. Likewise, quick wins will enable community members to see that their engagement matters. As a result, they will be more likely to embrace ambitious goals for social change. “You have to give folks who are ready to run work that will keep them energized, and [you have to] give others time to absorb change and build trust in the process,” Baptiste-Good says. “It takes patience and relationships to make it work.”

Managing constituencies through change | Leaders who shift to a new data-driven framework need to manage how various constituencies react to that change. A good way to start is by distinguishing between technical challenges and adaptive challenges. In The Practice of Adaptive Leadership , Ronald A. Heifetz, Alexander Grashow, and Marty Linsky explain that distinction: “Technical problems … can be resolved through the application of authoritative expertise and through the organization’s current structures, procedures, and ways of doing things. Adaptive challenges can only be addressed through changes in people’s priorities, beliefs, habits, and loyalties.” 16 For leaders, it’s tempting to focus on straightforward technical challenges (such as developing criteria for funding a data-driven intervention) and to neglect pressing adaptive challenges (such as dealing with changes in relationships and behaviors that staff members, partners, and service recipients will experience with the rollout of that intervention).

Multiple constituencies will feel the effects of a shift in strategy. There are existing partners, who will need to change their ways of operating and who may lose funding. There are potential new providers, who must gear up to help implement the new strategy. There are intended beneficiaries, who may need to alter or discontinue their relationships with trusted service providers. There are grant officers, who may need to jettison grantee relationships that they have cultivated over many years. And so on. To build community engagement around adoption of a new framework, leaders must prepare all of these constituencies for the adaptive changes they will have to make.

Communication is paramount, and it should begin early in the change process. In particular, leaders should take these steps:

- Signal changes early so that stakeholders can prepare for them.

- Focus less on expressing excitement about new practices than on showing empathy for the concerns of each constituency. (“Seek first to understand—and then to be understood” is a good rule to follow.)

- Disclose how and why decisions were made, and who made them.

- Acknowledge that there will be trade-offs and losses, and explain that they are a necessary consequence of adopting a strategy that promises to improve results.

- Clearly describe the transition process for people and groups that are willing and able to move toward the new framework.

Above all, leaders must focus on managing expectations for each constituency each step of the way.

Models of Engagement

Community engagement is not easy work, but it is important work. Here are two initiatives in which social change leaders are pursuing a community engagement strategy as part of their effort to implement data-driven solutions.

A youth program in Providence | In 2012, the Annie E. Casey Foundation launched an initiative in partnership with the Providence Children and Youth Cabinet (CYC) , an organization that was then part of the mayor’s office in Providence, R.I. Working within the foundation’s Evidence2Success framework, the CYC surveyed more than 5,000 young people in the 6th, 8th, 10th, and 12th grades about the root causes of personal and academic success—factors such as social and emotional skills, relationships, and family support. The CYC then convened community leaders and residents from two neighborhoods to discuss the survey data and to create a set of shared priorities. A diverse group of city, state, and neighborhood leaders helped oversee that process.

These shared priorities—which cover outcomes related to truancy and absenteeism, delinquent behavior, and emotional well-being—became the central point of focus for the initiative. Implementation teams, which included both residents and social service providers, established improvement goals for each priority. The teams then used Blueprints for Healthy Development , an online resource maintained by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, to select six evidence-based programs that are designed to advance those goals. In addition, CYC leaders conferred with residents about resources and forms of assistance that the community will need to ensure the success of these programs. Implementation of three of the six identified programs is now under way, and the CYC will measure progress toward the improvement goals in future surveys.

From the start, CYC leaders worked to improve the power dynamics among stakeholders by communicating transparently about their decision-making process. “We tailored information to different groups to empower them,” says Rebecca Boxx, director of the CYC. “We engaged everyone in a shared framework that was new to all. For community residents, we said, ‘This data is you, your lives. You own that.’ There was tremendous power in helping residents own their role.” In effect, Boxx adds, the initiative has involved “flipping expertise”—in other words, placing community members “on equal footing” with public officials, social service providers, and the like. (To ensure that the CYC would remain an independent voice for local communities—one whose future would not depend on election results—CYC leaders eventually moved the group outside the mayor’s office.)

CYC leaders spent about 18 months engaging with community members and another 18 months implementing the initial set of three evidence-based programs. “It will take three to four years to start seeing community-level results,” says Jessie Wattrous, a senior associate at the Annie E. Casey Foundation. “There is a win for [city officials] in saying, ‘We are listening to our community and spending our dollars on programs that have been proven to work.’ You also have community leaders and residents speaking out about it.” The foundation recently launched Evidence2Success partnerships in Alabama and Utah that build on the lessons of the Providence initiative to pursue evidence-based programs in those states.

A health program in Milwaukee | At one time, Milwaukee had the highest African-American infant mortality rate in the United States. To confront that problem, several partners—including the United Way of Greater Milwaukee, the mayor of that city, and the Wisconsin Partnership Program at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health —launched the Lifecourse Initiative for Healthy Families (LIHF) in 2012.

As part of the initiative, LIHF leaders invited researchers from universities, nonprofit advocacy groups, and the City of Milwaukee Health Department to share evidence about the causes of infant mortality and ways to reduce it. Many LIHF participants initially believed that unsafe sleeping conditions were the leading cause of infant mortality. But data gathered by the city’s Fetal Infant Mortality Review team showed that this factor accounted for only 15 percent of deaths and that more than 60 percent of deaths were the result of premature births. After researching evidence-based approaches to reducing the incidence of premature birth, LIHF participants agreed on a set of initiatives that focus on access to health services, fatherhood involvement, and other social determinants of health.

Previously, the City of Milwaukee and the United Way had partnered on an initiative that reduced teen pregnancy by 57 percent in seven years. (Milwaukee also once had the highest teen pregnancy rate in the nation.) Lessons from that initiative left these partners with a commitment to deep and inclusive community engagement. In the case of LIHF, those who oversaw the initiative began with a two-year planning process that involved convening more than 100 community leaders from all parts of the city.

In developing LIHF, leaders put special emphasis on achieving racial equity in the design and leadership composition of the initiative. At a launch meeting for LIHF, a group of more than 70 community leaders and residents spent an hour discussing racism and its impact on health among African-American women. Subsequent meetings have dealt explicitly with the role that racial equity must play in reaching LIHF goals. An African-American woman business leader cochairs the LIHF Steering Committee (the mayor of Milwaukee is the other cochair), and an African-American community activist serves as director of the initiative. To gain residents’ input and support, LIHF leaders also hired six community organizers who live in targeted neighborhoods and placed two people from those neighborhoods on the steering committee.

Engaging with Data

Data-driven practices and programs hold great promise as a means for making progress against seemingly intractable social problems. But ultimately they will work only when community members are able to engage in them as leaders and partners. Community engagement has two significant benefits: It can achieve real change in people’s lives—especially in the lives of the most vulnerable members of a community—and it can instill a can-do spirit that extends across an entire community.

As policymakers, elected officials, philanthropists, and nonprofit leaders shift resources to data-driven programs, they must ensure that community engagement becomes a critical element in that shift. Without such engagement, even the best programs—even programs backed by the most robust data—will not yield positive results, let alone lasting change.

Support SSIR ’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges. Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today .

Read more stories by Paul Schmitz & Melody Barnes .

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

How to Write the Community Essay – Guide with Examples (2023-24)

September 6, 2023

Students applying to college this year will inevitably confront the community essay. In fact, most students will end up responding to several community essay prompts for different schools. For this reason, you should know more than simply how to approach the community essay as a genre. Rather, you will want to learn how to decipher the nuances of each particular prompt, in order to adapt your response appropriately. In this article, we’ll show you how to do just that, through several community essay examples. These examples will also demonstrate how to avoid cliché and make the community essay authentically and convincingly your own.

Emphasis on Community

Do keep in mind that inherent in the word “community” is the idea of multiple people. The personal statement already provides you with a chance to tell the college admissions committee about yourself as an individual. The community essay, however, suggests that you depict yourself among others. You can use this opportunity to your advantage by showing off interpersonal skills, for example. Or, perhaps you wish to relate a moment that forged important relationships. This in turn will indicate what kind of connections you’ll make in the classroom with college peers and professors.

Apart from comprising numerous people, a community can appear in many shapes and sizes. It could be as small as a volleyball team, or as large as a diaspora. It could fill a town soup kitchen, or spread across five boroughs. In fact, due to the internet, certain communities today don’t even require a physical place to congregate. Communities can form around a shared identity, shared place, shared hobby, shared ideology, or shared call to action. They can even arise due to a shared yet unforeseen circumstance.

What is the Community Essay All About?

In a nutshell, the community essay should exhibit three things:

- An aspect of yourself, 2. in the context of a community you belonged to, and 3. how this experience may shape your contribution to the community you’ll join in college.

It may look like a fairly simple equation: 1 + 2 = 3. However, each college will word their community essay prompt differently, so it’s important to look out for additional variables. One college may use the community essay as a way to glimpse your core values. Another may use the essay to understand how you would add to diversity on campus. Some may let you decide in which direction to take it—and there are many ways to go!

To get a better idea of how the prompts differ, let’s take a look at some real community essay prompts from the current admission cycle.

Sample 2023-2024 Community Essay Prompts

1) brown university.

“Students entering Brown often find that making their home on College Hill naturally invites reflection on where they came from. Share how an aspect of your growing up has inspired or challenged you, and what unique contributions this might allow you to make to the Brown community. (200-250 words)”

A close reading of this prompt shows that Brown puts particular emphasis on place. They do this by using the words “home,” “College Hill,” and “where they came from.” Thus, Brown invites writers to think about community through the prism of place. They also emphasize the idea of personal growth or change, through the words “inspired or challenged you.” Therefore, Brown wishes to see how the place you grew up in has affected you. And, they want to know how you in turn will affect their college community.

“NYU was founded on the belief that a student’s identity should not dictate the ability for them to access higher education. That sense of opportunity for all students, of all backgrounds, remains a part of who we are today and a critical part of what makes us a world-class university. Our community embraces diversity, in all its forms, as a cornerstone of the NYU experience.

We would like to better understand how your experiences would help us to shape and grow our diverse community. Please respond in 250 words or less.”

Here, NYU places an emphasis on students’ “identity,” “backgrounds,” and “diversity,” rather than any physical place. (For some students, place may be tied up in those ideas.) Furthermore, while NYU doesn’t ask specifically how identity has changed the essay writer, they do ask about your “experience.” Take this to mean that you can still recount a specific moment, or several moments, that work to portray your particular background. You should also try to link your story with NYU’s values of inclusivity and opportunity.

3) University of Washington

“Our families and communities often define us and our individual worlds. Community might refer to your cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood or school, sports team or club, co-workers, etc. Describe the world you come from and how you, as a product of it, might add to the diversity of the UW. (300 words max) Tip: Keep in mind that the UW strives to create a community of students richly diverse in cultural backgrounds, experiences, values and viewpoints.”

UW ’s community essay prompt may look the most approachable, for they help define the idea of community. You’ll notice that most of their examples (“families,” “cultural group, extended family, religious group, neighborhood”…) place an emphasis on people. This may clue you in on their desire to see the relationships you’ve made. At the same time, UW uses the words “individual” and “richly diverse.” They, like NYU, wish to see how you fit in and stand out, in order to boost campus diversity.

Writing Your First Community Essay

Begin by picking which community essay you’ll write first. (For practical reasons, you’ll probably want to go with whichever one is due earliest.) Spend time doing a close reading of the prompt, as we’ve done above. Underline key words. Try to interpret exactly what the prompt is asking through these keywords.

Next, brainstorm. I recommend doing this on a blank piece of paper with a pencil. Across the top, make a row of headings. These might be the communities you’re a part of, or the components that make up your identity. Then, jot down descriptive words underneath in each column—whatever comes to you. These words may invoke people and experiences you had with them, feelings, moments of growth, lessons learned, values developed, etc. Now, narrow in on the idea that offers the richest material and that corresponds fully with the prompt.

Lastly, write! You’ll definitely want to describe real moments, in vivid detail. This will keep your essay original, and help you avoid cliché. However, you’ll need to summarize the experience and answer the prompt succinctly, so don’t stray too far into storytelling mode.

How To Adapt Your Community Essay

Once your first essay is complete, you’ll need to adapt it to the other colleges involving community essays on your list. Again, you’ll want to turn to the prompt for a close reading, and recognize what makes this prompt different from the last. For example, let’s say you’ve written your essay for UW about belonging to your swim team, and how the sports dynamics shaped you. Adapting that essay to Brown’s prompt could involve more of a focus on place. You may ask yourself, how was my swim team in Alaska different than the swim teams we competed against in other states?

Once you’ve adapted the content, you’ll also want to adapt the wording to mimic the prompt. For example, let’s say your UW essay states, “Thinking back to my years in the pool…” As you adapt this essay to Brown’s prompt, you may notice that Brown uses the word “reflection.” Therefore, you might change this sentence to “Reflecting back on my years in the pool…” While this change is minute, it cleverly signals to the reader that you’ve paid attention to the prompt, and are giving that school your full attention.

What to Avoid When Writing the Community Essay

- Avoid cliché. Some students worry that their idea is cliché, or worse, that their background or identity is cliché. However, what makes an essay cliché is not the content, but the way the content is conveyed. This is where your voice and your descriptions become essential.

- Avoid giving too many examples. Stick to one community, and one or two anecdotes arising from that community that allow you to answer the prompt fully.

- Don’t exaggerate or twist facts. Sometimes students feel they must make themselves sound more “diverse” than they feel they are. Luckily, diversity is not a feeling. Likewise, diversity does not simply refer to one’s heritage. If the prompt is asking about your identity or background, you can show the originality of your experiences through your actions and your thinking.

Community Essay Examples and Analysis

Brown university community essay example.

I used to hate the NYC subway. I’ve taken it since I was six, going up and down Manhattan, to and from school. By high school, it was a daily nightmare. Spending so much time underground, underneath fluorescent lighting, squashed inside a rickety, rocking train car among strangers, some of whom wanted to talk about conspiracy theories, others who had bedbugs or B.O., or who manspread across two seats, or bickered—it wore me out. The challenge of going anywhere seemed absurd. I dreaded the claustrophobia and disgruntlement.

Yet the subway also inspired my understanding of community. I will never forget the morning I saw a man, several seats away, slide out of his seat and hit the floor. The thump shocked everyone to attention. What we noticed: he appeared drunk, possibly homeless. I was digesting this when a second man got up and, through a sort of awkward embrace, heaved the first man back into his seat. The rest of us had stuck to subway social codes: don’t step out of line. Yet this second man’s silent actions spoke loudly. They said, “I care.”

That day I realized I belong to a group of strangers. What holds us together is our transience, our vulnerabilities, and a willingness to assist. This community is not perfect but one in motion, a perpetual work-in-progress. Now I make it my aim to hold others up. I plan to contribute to the Brown community by helping fellow students and strangers in moments of precariousness.

Brown University Community Essay Example Analysis

Here the student finds an original way to write about where they come from. The subway is not their home, yet it remains integral to ideas of belonging. The student shows how a community can be built between strangers, in their responsibility toward each other. The student succeeds at incorporating key words from the prompt (“challenge,” “inspired” “Brown community,” “contribute”) into their community essay.

UW Community Essay Example

I grew up in Hawaii, a world bound by water and rich in diversity. In school we learned that this sacred land was invaded, first by Captain Cook, then by missionaries, whalers, traders, plantation owners, and the U.S. government. My parents became part of this problematic takeover when they moved here in the 90s. The first community we knew was our church congregation. At the beginning of mass, we shook hands with our neighbors. We held hands again when we sang the Lord’s Prayer. I didn’t realize our church wasn’t “normal” until our diocese was informed that we had to stop dancing hula and singing Hawaiian hymns. The order came from the Pope himself.

Eventually, I lost faith in God and organized institutions. I thought the banning of hula—an ancient and pure form of expression—seemed medieval, ignorant, and unfair, given that the Hawaiian religion had already been stamped out. I felt a lack of community and a distrust for any place in which I might find one. As a postcolonial inhabitant, I could never belong to the Hawaiian culture, no matter how much I valued it. Then, I was shocked to learn that Queen Ka’ahumanu herself had eliminated the Kapu system, a strict code of conduct in which women were inferior to men. Next went the Hawaiian religion. Queen Ka’ahumanu burned all the temples before turning to Christianity, hoping this religion would offer better opportunities for her people.

Community Essay (Continued)

I’m not sure what to make of this history. Should I view Queen Ka’ahumanu as a feminist hero, or another failure in her islands’ tragedy? Nothing is black and white about her story, but she did what she thought was beneficial to her people, regardless of tradition. From her story, I’ve learned to accept complexity. I can disagree with institutionalized religion while still believing in my neighbors. I am a product of this place and their presence. At UW, I plan to add to campus diversity through my experience, knowing that diversity comes with contradictions and complications, all of which should be approached with an open and informed mind.

UW Community Essay Example Analysis

This student also manages to weave in words from the prompt (“family,” “community,” “world,” “product of it,” “add to the diversity,” etc.). Moreover, the student picks one of the examples of community mentioned in the prompt, (namely, a religious group,) and deepens their answer by addressing the complexity inherent in the community they’ve been involved in. While the student displays an inner turmoil about their identity and participation, they find a way to show how they’d contribute to an open-minded campus through their values and intellectual rigor.

What’s Next

For more on supplemental essays and essay writing guides, check out the following articles:

- How to Write the Why This Major Essay + Example

- How to Write the Overcoming Challenges Essay + Example

- How to Start a College Essay – 12 Techniques and Tips

- College Essay

Kaylen Baker

With a BA in Literary Studies from Middlebury College, an MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, and a Master’s in Translation from Université Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis, Kaylen has been working with students on their writing for over five years. Previously, Kaylen taught a fiction course for high school students as part of Columbia Artists/Teachers, and served as an English Language Assistant for the French National Department of Education. Kaylen is an experienced writer/translator whose work has been featured in Los Angeles Review, Hybrid, San Francisco Bay Guardian, France Today, and Honolulu Weekly, among others.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High School Success

- High Schools

- Homeschool Resources

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Outdoor Adventure

- Private High School Spotlight

- Research Programs

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Teacher Tools

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

How to Write a Great Community Service Essay

College Admissions , Extracurriculars

Are you applying to a college or a scholarship that requires a community service essay? Do you know how to write an essay that will impress readers and clearly show the impact your work had on yourself and others?

Read on to learn step-by-step instructions for writing a great community service essay that will help you stand out and be memorable.

What Is a Community Service Essay? Why Do You Need One?

A community service essay is an essay that describes the volunteer work you did and the impact it had on you and your community. Community service essays can vary widely depending on specific requirements listed in the application, but, in general, they describe the work you did, why you found the work important, and how it benefited people around you.

Community service essays are typically needed for two reasons:

#1: To Apply to College

- Some colleges require students to write community service essays as part of their application or to be eligible for certain scholarships.

- You may also choose to highlight your community service work in your personal statement.

#2: To Apply for Scholarships

- Some scholarships are specifically awarded to students with exceptional community service experiences, and many use community service essays to help choose scholarship recipients.

- Green Mountain College offers one of the most famous of these scholarships. Their "Make a Difference Scholarship" offers full tuition, room, and board to students who have demonstrated a significant, positive impact through their community service

Getting Started With Your Essay

In the following sections, I'll go over each step of how to plan and write your essay. I'll also include sample excerpts for you to look through so you can get a better idea of what readers are looking for when they review your essay.

Step 1: Know the Essay Requirements

Before your start writing a single word, you should be familiar with the essay prompt. Each college or scholarship will have different requirements for their essay, so make sure you read these carefully and understand them.

Specific things to pay attention to include:

- Length requirement

- Application deadline

- The main purpose or focus of the essay

- If the essay should follow a specific structure

Below are three real community service essay prompts. Read through them and notice how much they vary in terms of length, detail, and what information the writer should include.

From the Equitable Excellence Scholarship:

"Describe your outstanding achievement in depth and provide the specific planning, training, goals, and steps taken to make the accomplishment successful. Include details about your role and highlight leadership you provided. Your essay must be a minimum of 350 words but not more than 600 words."

From the Laura W. Bush Traveling Scholarship:

"Essay (up to 500 words, double spaced) explaining your interest in being considered for the award and how your proposed project reflects or is related to both UNESCO's mandate and U.S. interests in promoting peace by sharing advances in education, science, culture, and communications."

From the LULAC National Scholarship Fund:

"Please type or print an essay of 300 words (maximum) on how your academic studies will contribute to your personal & professional goals. In addition, please discuss any community service or extracurricular activities you have been involved in that relate to your goals."

Step 2: Brainstorm Ideas

Even after you understand what the essay should be about, it can still be difficult to begin writing. Answer the following questions to help brainstorm essay ideas. You may be able to incorporate your answers into your essay.

- What community service activity that you've participated in has meant the most to you?

- What is your favorite memory from performing community service?

- Why did you decide to begin community service?

- What made you decide to volunteer where you did?

- How has your community service changed you?

- How has your community service helped others?

- How has your community service affected your plans for the future?

You don't need to answer all the questions, but if you find you have a lot of ideas for one of two of them, those may be things you want to include in your essay.

Writing Your Essay

How you structure your essay will depend on the requirements of the scholarship or school you are applying to. You may give an overview of all the work you did as a volunteer, or highlight a particularly memorable experience. You may focus on your personal growth or how your community benefited.

Regardless of the specific structure requested, follow the guidelines below to make sure your community service essay is memorable and clearly shows the impact of your work.

Samples of mediocre and excellent essays are included below to give you a better idea of how you should draft your own essay.

Step 1: Hook Your Reader In

You want the person reading your essay to be interested, so your first sentence should hook them in and entice them to read more. A good way to do this is to start in the middle of the action. Your first sentence could describe you helping build a house, releasing a rescued animal back to the wild, watching a student you tutored read a book on their own, or something else that quickly gets the reader interested. This will help set your essay apart and make it more memorable.

Compare these two opening sentences:

"I have volunteered at the Wishbone Pet Shelter for three years."

"The moment I saw the starving, mud-splattered puppy brought into the shelter with its tail between its legs, I knew I'd do whatever I could to save it."

The first sentence is a very general, bland statement. The majority of community service essays probably begin a lot like it, but it gives the reader little information and does nothing to draw them in. On the other hand, the second sentence begins immediately with action and helps persuade the reader to keep reading so they can learn what happened to the dog.

Step 2: Discuss the Work You Did

Once you've hooked your reader in with your first sentence, tell them about your community service experiences. State where you work, when you began working, how much time you've spent there, and what your main duties include. This will help the reader quickly put the rest of the essay in context and understand the basics of your community service work.

Not including basic details about your community service could leave your reader confused.

Step 3: Include Specific Details

It's the details of your community service that make your experience unique and memorable, so go into the specifics of what you did.

For example, don't just say you volunteered at a nursing home; talk about reading Mrs. Johnson her favorite book, watching Mr. Scott win at bingo, and seeing the residents play games with their grandchildren at the family day you organized. Try to include specific activities, moments, and people in your essay. Having details like these let the readers really understand what work you did and how it differs from other volunteer experiences.

Compare these two passages:

"For my volunteer work, I tutored children at a local elementary school. I helped them improve their math skills and become more confident students."