- 0 Shopping Cart

Lesotho Large-Scale Water Transfer Scheme Case Study

AQA GCSE Geography > Resource Management > Lesotho Large-Scale Water Transfer Scheme Case Study

Lesotho Large-scale Water Transfer Scheme Case Study

Lesotho is a landlocked country within the interior of South Africa, in southern Africa. It is distinguished by its mountainous topography and status as the only nation to be entirely above 1,000 meters in elevation. Its capital and largest city is Maseru. Lesotho is also known as the “Kingdom in the Sky” due to its high altitude—it has the highest lowest point of any country in the world. The country has a constitutional monarchy and gained independence from Britain in 1966.

The country experiences high poverty levels and struggles to feed its growing population. Most farms are subsistence, and productivity is low. It is economically dependent on South Africa.

Lesotho is a low-income country (LIC) and several problems limit the country’s development :

- The country faces frequent dry spells, leading to droughts and food shortages. This can cause famine.

- Lesotho’s government and politics are still developing, which impacts the economy’s growth. Lesotho is one of the worst countries in the world for wealth inequality. Some profit from diamond mining , whereas others remain unemployed and impoverished.

To address these inequalities, the government decided in 2004 to trade surplus water with neighbouring South Africa to improve its economy and development.

What is the Lesotho Highland Water Project?

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) is a large-scale water transfer scheme where water is diverted from the highlands of Lesotho to South Africa’s Free State and the greater Johannesburg area, which desperately needs water. This is mainly due to these regions’ rapidly growing population and industrial demands.

The project includes the construction of dams, reservoirs, and tunnels designed to capture the headwaters of the Senqu/Orange River in Lesotho and transfer it to South Africa.

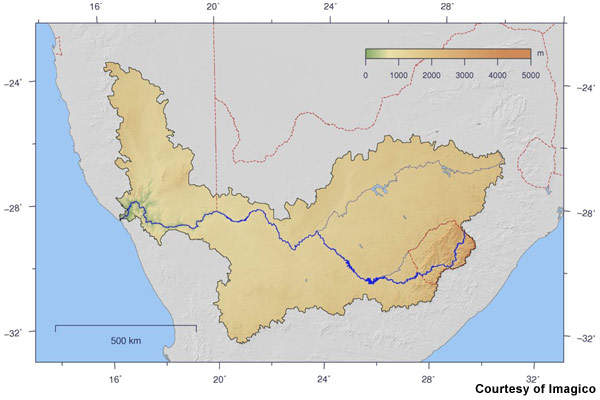

A Map of the Lesotho Highland Water Project

On completion, 40 per cent of the water from the Segu (Orange) River in Lesotho will be transferred to the River Vaal in South Africa. The scheme is expected to take 30 years to complete.

The main features of the scheme include:

- The Katse and Mohale Dams (completed in 1998 and 2002) store water transferred through a tunnel to the Mohale Reservoir .

- Water is then transported to South Africa through a 32km tunnel, enabling hydroelectric power to be produced at the Muela plant.

- The 165m high Polihali Dam will hold 2.2 billion m3 of water and connect to the Katse Dam by a 38km transfer tunnel.

- The Tsoelike Dam will be built at the confluence of the Tsolike and Senqu Rivers and will store up to 2223 million m3.

- The Ntoahae Dam and pumping station will be built 40km downstream from the Tsoelike Dam on the Senqu River.

When complete, 200km of tunnels will transfer 2000 million m3 of water to South Africa annually.

Why is the Lethoso Highland Water Project needed?:

- South Africa’s Demand: South Africa has an ever-increasing demand for water due to urbanisation , economic growth, and a relatively dry climate.

- Economic Benefits for Lesotho: Lesotho sees this as an opportunity to generate revenue by selling water, which can be used for the country’s development.

- Environmental Conservation : The project provides a clean and sustainable source of water for South Africa

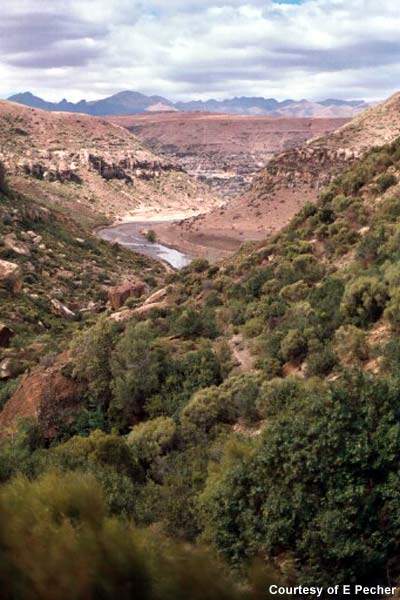

The Katse Dam

Advantages for Lesotho:

- Economic Development : The project generates significant revenue for Lesotho, boosting its economy. It will provide 75% of its GDP. The income helps develop and improve standards of living.

- Energy production: The scheme will provide Lesotho with all its HEP requirements.

- Job Creation: It has created thousands of jobs for the local population during construction.

- Infrastructure Development: The project has led to the development of infrastructure such as roads and communication networks with access roads built to the construction sites.

- Improved Water Supply: Some areas of Lesotho benefit from improved water supply systems due to the project. Water supply will reach 90% of the population of the capital, Maseru.

- Improved Sanitation: Sanitation coverage will increase from 15% to 20%.

Advantages for South Africa:

- Water Security : It provides a critical water source for South Africa’s industrial heartland.

- Safe Water: Provides safe water for the 10% of the population without access to a safe supply.

- Economic Growth: Water is essential for sustaining economic activity in the Gauteng Province.

- Drought Mitigation: It helps mitigate the effects of periodic droughts in the region. It provides water to an area with an uneven rainfall pattern and regular droughts.

- Ecosystem Improvement: Freshwater reduces the acidity of the Vaal River Reservoir. Water pollution from industry, sewage, and gold mines destroyed the local ecosystem . The influx of fresh water is restoring the balance.

Disadvantages for Lesotho:

- Displacement: Communities have been displaced by the construction of the reservoirs. The construction of the first two dams meant 30000 people had to move from their land. The construction of the Polihali Dam will displace 17 villages and reduce agricultural land for 71 villages.

- Environmental Impact : There has been an impact on local ecosystems, including the destruction of a unique wetland, due to the control of regular flooding downstream of the dams.

- Corruption: Corruption has prevented money and investment from reaching those affected by the construction.

- Dependency: An over-reliance on revenues from water sales to South Africa may make Lesotho economically vulnerable.

Disadvantages for South Africa:

- Cost: The water cost is significant and must be borne by the South African government and, ultimately, the consumers. Costs are likely to reach US$4 billion.

- Leakages: 40% of water is lost due to leaks.

- Inequality: The increased water tariffs for the scheme are too high for the poorest people.

- Political Dependence: There is a reliance on Lesotho for a critical resource, which could lead to political challenges.

- Potential for Conflict: As water becomes an increasingly scarce resource, the potential for conflict over water rights could arise.

The LHWP is an example of a transboundary water resource management project with complex implications for both nations. It’s a balancing act between meeting the water needs of a growing population and economy in South Africa and managing the socio-economic and environmental impacts on Lesotho.

Despite the project not being complete, the Lesotho government has agreed to develop a second transfer scheme with Botswana. This could lead to an increase in Lesotho’s economic and political power in the future.

Geographic Overview

Lesotho, known as the “Kingdom in the Sky,” is a mountainous, landlocked country entirely above 1,000 meters, encircled by South Africa.

Economic Context

Lesotho is economically dependent on its neighbour, with subsistence farming prevalent, but faces high poverty and food supply challenges.

Lesotho Highlands Water Project

A massive water transfer initiative, the LHWP diverts water from Lesotho to South Africa’s Free State and Johannesburg, catering to their growing demand.

Infrastructure Developments

The project includes the construction of major dams like Katse and Mohale, a hydroelectric power plant at Muela, and extensive tunnel systems for water transfer.

Benefits to Lesotho

Significant revenue boost contributing to 75% of GDP, energy self-sufficiency, job creation, infrastructure improvements, and enhanced water and sanitation access.

Benefits to South Africa

Ensures water security , supports economic activities in key provinces, mitigates drought effects, and improves local ecosystems with freshwater influx.

Challenges and Costs

It involves community displacement and environmental changes in Lesotho, while South Africa faces high costs, water leakages, and potential political dependency issues.

Check Your Knowledge

Coming soon

Test Yourself

Resource management.

Menu coming soon

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Please Support Internet Geography

If you've found the resources on this site useful please consider making a secure donation via PayPal to support the development of the site. The site is self-funded and your support is really appreciated.

Search Internet Geography

Top posts and pages.

Latest Blog Entries

Pin It on Pinterest

- Click to share

- Print Friendly

The Urge To Help

Resisting urges, promoting reflection

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project: Impacts of Large-Scale Water Development on Local Communities

Cover image courtesy of Aurecon.

–by Lauren Douglas and Simon Dempsey–

A 1986 treaty between Lesotho and South Africa initiated a large-scale water development project called the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP). Financed heavily by foreign investment, the LHWP was designed to increase water supply for the Guateng Province of South Africa while simultaneously increasing jobs and electricity in the Lesotho. However, macro-scale and institutional corruption within the LHWP have obfuscated most of the intended positive outcomes of the project. Additionally, failed compensation schemes have done little to address ways in which the LHWP exacerbated income inequality, destroyed valuable resources, and undermined social structures in rural project-affected areas. This article examines the origins and goals of the LHWP and further explores the multiple negative consequences it imposed on rural communities.

Introduction

In 1986, a treaty between the Kingdom of Lesotho and the Republic of South Africa initiated a large-scale water development project known the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP). About the size of Belgium, Lesotho is landlocked by its powerful neighbor, South Africa. While the country is among the world’s poorest and is relatively devoid of natural resources—particularly arable land—its mountain highlands contain an abundance of water. [1] As such, the LHWP aimed to utilize the vast abundance of water in Lesotho to deliver water to the highly populated Guateng Province of South Africa. Advocates for the project presented it as a natural solution to combat the water shortage experienced by South Africa while simultaneously providing an influx of electric power, jobs, money, and infrastructure to Lesotho—a country where over 50% of the population lives underneath the poverty line. [2]

However, since its inception the LHWP has been mired in controversy as it either failed to achieve its cited benefits or sacrificed too much to do so. This article will explore some of the most glaring failings of the project, particularly how these flaws harmed rural communities located within the project areas. The LHWP exacerbated poor conditions for project-affected populations in Lesotho due to pervasive institutional corruption, elimination of various tangible resources, destruction of local social paradigms, and an ineffective compensation scheme.

Project Overview

The idea behind the LHWP began with the British High Commissioner to Lesotho, Sir Evelyn Baring, in the 1950s. [3] He realized the potential within Lesotho’s abundant water supply for future economic partnership with South Africa. In 1978, both South Africa and Lesotho conducted an initial feasibility study. The Lahmeyer MacDonald Consortium followed this up with a more in-depth three-year study in 1983. The study concluded that the proposed water project would be mutually beneficial for both countries, providing water to the dry areas of South Africa in the Guateng Province while generating hydroelectric power for Lesotho.

With these findings, both countries moved forward to sign a treaty in 1986 that officially began the project by outlining it goals, the roles of South Africa and Lesotho, and a long-term plan for its implementation. The treaty also established parastatal authorities whose responsibilities included general supervision of the project as well as implementation of compensation and resettlement programs; for Lesotho this was the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority (LHDA), for South Africa, the Trans-Calderon Tunnel Authority. [4] Further details of the treaty include five planned project phases to be carried out over a thirty-year period, with an immediate focus on Phase I.

Currently, only Phase I of the project has been completed. This represents a significant lag past the initial 30-year timeframe detailed by the treaty. [5] The delay can be attributed to the project’s sheer scale, as well as pervasive project corruption and political strife in Lesotho. The project will now not likely be completed for another decade. Yet, this does not mean that the LHWP and its impact cannot yet be observed and analyzed. Thus, the remainder of this article will focus on the details and impact of Phase I of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, specifically within the Kingdom of Lesotho.

Construction of the Katse Dam as part of Phase 1A began in 1989. The dam itself is 180 meters high and 710 meters long. [6] A 45 kilometer transfer tunnel was also excavated between the Katse Dam and the planned Muela Hydropower Station. [7] Phase 1B contained the construction of the Mohale Dam, the Muela Hydropower Station, and a diversion tunnel to the Katse Dam.

The Mohale Dam spans 564 meters with a height of 140 meters. However, the combined outputs of both dams only totals about 29 cubic meters per second of water delivered, short of its desired output of 70 cubic meters of water per second. The Muela Hydropower Station was commissioned in 1998 and now generates 72 megawatts of power for Lesotho. This has served to reduce Lesotho’s near complete dependence on South Africa for electricity. Finally, Phase 1B—and by extension the entirety of Phase I—saw its completion with the inauguration of the Mohale Dam in 2004.

Positive Outcomes

The successful completion of Phase 1 created some undeniable positive outcomes for Lesotho. The official Phase I website cites a rise in GDP per annum from 3% to 5.5% during Phase 1A construction. [8] As of 1998, the project accounted for 13.6% of Lesotho’s GDP; one third of all construction in Lesotho is project related. [9] In the same vein, 16,000 jobs were created for Lesotho, and the country decreased its energy dependence on South Africa after the completion of the Muela Hydropower Plant. Furthermore, Lesotho has received over M5.2 billion in royalty revenue from water transfer and electricity sales. [10]

Despite not yet achieving the project’s water transfer goal, South Africa’s water needs have been more than met. In fact, the project is currently outputting 38.3 cubic meters per second, which is six times the daily usage of Capetown. [11] Lesotho has also benefitted from infrastructure improvements; the official Phase I website cites the construction of 400 km of gravel roads and 300 km of tarred roads, the rehabilitation of 133 km of gravel roads, and the construction of 11 bridges. [12] Certainly, the project has achieved many of its original, tangible goals, at least on paper.

Unfortunately, actual implementation of the project was rife with issues, one of which takes the form of institutional corruption. The political climate of the countries involved in the LHWP certainly did not encourage accountability. In 1986, the same year the treaty was signed, a military coup overthrew the government of Lesotho; [13] meanwhile, South Africa was ruled by an apartheid government. Previous negotiations with Lesotho on a water treaty had been unsuccessful in part due to the Lesotho’s civilian government being unwilling to associate itself with South Africa’s apartheid government. Thus, South Africa backed the military coup in part to negotiate its way to the treaty that would become the LHWP. [14]

In this way, the LHWP was founded upon an agreement between two undemocratic states; while not directly causing widespread corruption within the project, these circumstances prevented legitimate checks against growth of corruption. Much of this corruption remained hidden until 1993, when a new Lesothan civilian government conducted an audit on the LHDA. The audit revealed that the LHDA’s CEO, Masupha Ephraim Sole, was misappropriating funds for his own use. Further investigation into large sums of money received by Sole found that he had been accepting bribes from outside contractors in order to be awarded bids for the project. [15] This practice had been occurring since the project’s inception. Sole and many of the contractors were subsequently brought to court and found guilty on charges of fraud and bribery.

Similarly, project wealth stayed in the hands of the privileged. Proponents of the LHWP stated how project royalties would be redistributed among the nation’s poorest, recognizing adversely affected people first. As such, the Lesotho Fund for Community Development was created to conduct redistribution of Lesotho’s $25 million of annual royalties. [16] However, a World Bank audit found the organization guilty of corruption, with local politicians instead lining their own pockets and using the money to reward supporters of their party; Lesotho is still ranked within the top ten highest global income disparities. [17]

Many effects of this corruption still taint the LHWP. Corruption and bribery quickly gave way to project mismanagement and negligence concerning the project’s wide-ranging effects on the environment and local populations. The reputation of the LHWP became so controversial that the LHDA has attempted to reform many of its policies, even going so far as to release a new anti-corruption policy in 2011. Though this policy is a step in the right direction, it still leaves much to be desired for the LHWP—whether it actually demonstrates it has learned from its past mistakes remains to be seen. Subsequent analysis of the LHWP’s many adverse effects on local populations will demonstrate how much difficulty the project faces in winning back public trust.

Compensation Policy

The reputation of large-scale water project development is not a particularly flattering one. According to a World Commission on Dams report, this type of infrastructure development has physically displaced an estimated 40-80 million people throughout the past century. [18] Furthermore, with 60% of the world’s rivers damned by 2000 and two-thirds of large dams constructed in poor, remote areas, many studies have noted a severe disparity in the distribution of resulting benefits. Those affected by projects, while typically not benefitting from the wealth created by damns, also suffer consequences such as loss of livelihood, forced migration, and cultural alienation. [19] Given this unflattering history, large funders of these types of development projects (such as the World Bank, the world’s primary financier of large dam development) fell under pressure to adopt a set of guidelines concerning the resettlement and compensation of those that damns displaced. [20]

The World Bank did, in fact, act as a major financier of the LHWP, contributing $110 million to Phase 1A alone. As a result, the project treaty was legally obligated to follow the WB’s own guidelines regarding displaced and resettled populations. Article 44 of the 1986 treaty thus states that “The [project] shall, ensure that is far as is reasonably possible, the standard of living and the income of persons displaced by the construction of an approved scheme shall not be reduced from the standard of living and the income existing prior to the displacement of such persons.” [21] As previously mentioned, the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority represented the main entity responsible for ensuring implementation of compensation and resettlement programs. [22] Reassured by the World Bank’s vote of confidence and appraisals of minimal socio-environmental impacts, multiple other foreign financiers contributed to project funding. [23]

On paper, the compensation policies drawn up by the World Bank and LHDA are among the best to accompany a large-scale water development program. Comparatively, the LHWP hired more consultants, allocated more money, and made more efforts to restore affected livelihoods than almost any of dam development project in history. [24] For example, the compensation program for Phase 1A budgeted 1.3% (approximately $13 million) of the overall project cost for this purpose. The Phase 1B program was similarly well-funded, budgeting approximately $10 million for those affected by Mohale Dam. [25] On paper, the LHWP was off to a good start—clearly, the investors involved wanted to avoid the bad press typically associated with dam development.

The policy is largely defined by lump sum compensation for loss of resources. For example, those who had lost above 1000 m 2 of arable had to choose between an annual cash payment of $300 per hectare for 50 years or a one-time lump sum payment of $6,000 per hectare, also designed to provide 50 years’ worth of compensation. [26] To receive the lump sum compensation, the policy required applicants to draw up a viable “business plan” before granting them payment. [27] Again, a main motivation of these measures was to encourage the investment of foreign entities. This way, at the very least, the investors would have a reasonable escape clause in the event of creating severe socio-economic burdens for locals. While other dimensions of the compensation scheme included resettlement and rural development projects, this investigation will narrow its focus onto the failings of the direct compensation scheme as well as the host of tangential consequences created by the project itself.

Harm to Local Populations

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project, despite is promises and well-funded compensation plan, brought with it a host of detrimental effects to local populations. The most overwhelming blow is the significant loss of land. The Kingdom of Lesotho is landlocked; less of 10% of its land area is considered arable. By the end of Phase I, the LHWP had taken away 1,500 hectares of arable land, 1,900 ha 0f cropland, and 5,000 ha of grazing land. [28] Around 2,345 households’ fields became submerged, not even counting households who sharecropped them. Unfortunately, Lesotho’s most fertile land, the Mohale valley, was among the submerged regions. [29]

This loss of land has resulted in several adverse effects to locals. Most obviously, food security in the affected areas became highly strained as two-thirds of the population had depended on locally-produced crops. The loss of grazing land restricted herds of cattle, sheep, and goats to far smaller areas, overstressing the remaining grazing land. Additionally, the flooding of ravines and valleys took away “winter pastures” that helped shield the animals from icy winter winds; as a result, cattle-rearing became far more difficult. [30]

Another large blow was the loss of access to free, renewable resources. Fuel resources such as trees and shrubs became scarcer, taking away a common supplement to local incomes—the sale of firewood. Affected people became forced to walk significant distances to collect fuel for fire. Furthermore, the half of affected households who used to gather wild vegetables in the river valley were faced with traveling much-increased distances to gather them or forgo eating them at all. [31] Of the 175 species of medicinal plants growing in the flooded area—whose sale presented another source of supplementary income—many were wiped out completely. All told—excluding the economic value of lost crop and grazing land, the proportion of annual income lost due to lack of renewable resources totals around 45%. [32] As the resources that were previously gathered at little-to-no cost then required increased cost and effort to procure, many households stopped using the resource entirely rather than shouldering the extra cost. [33] In tangible terms, the variables of loss of land and access to resources provided the two largest blows to local livelihoods and sustainability.

Social Disruption

Beyond purely tangible losses, the LHWP generated a host of social traumas. The main source of these traumas can be traced to the huge influx of construction workers to rural areas; hearing of employment opportunity, thousands of men converged upon project areas. Unfortunately, this mass-migration meant that many locals failed to procure employment, a large promise of the project. Shanties built on the village outskirts by these men quickly outnumbered original households in the villages closest to construction sites. [34] Riding this influx of outsiders, shop owners raised prices of their wares, making purchases more difficult for locals. Additionally, many workers initiated affairs with local women, whose own husbands could not secure employment. Such disturbances to community relationships were addressed and condemned by local chiefs, whose authority was then undermined as non-local workers were not subject to these chiefs’ authority. As a result, local crimes among youth increased as the chieftainship lost respect. [35]

In a similar vein, HIV rates in project-affected areas increased significantly. A 1995 report by the Archives of Internal Medicine finds: “In the early years of the worldwide pandemic, there were no reported cases of AIDS in Lesotho. That all changed when HIV-infected construction workers arrived in the previously isolated LHWP areas. By 1992, HIV infection rates in villages around the dam were 0.5 percent, and infection rates in the dams’ work camps were over 20 times higher (5.3%).” [36] The rate of infection in the project-affected town of Leribe among 15-24 year olds jumped from 3% in 1991 to 12.6% in 1993. By 1999, 22% of pregnant women living around Katse Dam tested HIV positive. Meanwhile, in the nearby gated community of Katse Village, foreign workers from South Africa, the UK, France, Germany, and Italy lived in relative luxury. These wage-earning foreigners attracted the attention of many young local girls, who “[slept] where their parents don’t know,” in the words of a local 12-year-old. [37] This type of interpersonal involvement, among many of the other factors discussed, contributed to severe social collapse. In fact, the LHDA itself noted the disbenefits and how they “[left] the social fabric of these communities visibly disintegrating.” [38] Unfortunately, these great blows to local people present a whole other dimension of disruption—the intangible—which was not easily quantified and, in kind, not compensated in the least. This utter lack of pre-project consideration for social impact belies a lack of either effort or understanding on the part of foreign investors to anticipate full-picture consequences; a common attitude when directing resources to “developing” countries.

Failed Compensation

Even worse, the LHDA failed to effectively implement the compensation schemes that did exist. From the start, the management of the LHWP belied troubling signs. All management structures were dominated by engineers and politicians, translating to a lack of both expertise and concern for socio-economic issues and compensation objectives. The previously-discussed topic of corruption also played a role; concerning the LHDA, a 2007 World Bank report found that appointments to high-level positions had been driven by political interests instead of qualifications and experience. [39] This lack of effective infrastructure within the LDHA led to poor implementation of programs—programs that were not even comprehensive enough in the first place. In fact, a 1995 report found that project planners had underestimated the number of locals displaced by 600%. [40]

Beyond poor and negligent management, many inherent flaws of the program became apparent. A very unpopular policy was the 50-year time frame applied to all compensation of land. Many of the project-affected criticized the policy, pointing out that land is an asset passed down for countless generations, and thus a short-term compensation scheme did not account for potential impoverishment of offspring. [41] Another large flaw in compensation was the requirement of a business plan to receive the lump sum land compensation. Taking into account both lack of local experience in drawing up business plans and lack of LHDA criteria to evaluate them, very few households had received their compensation after four years of waiting. [42] Additionally, the compensation program entirely failed to consider the plight of sharecroppers who had previously subsisted on food and income gained from working on other people’s land. A population of 3,200 at Katse dam alone, these people were considered landless in the eyes of the LHDA and thus received no compensation whatsoever, as loss of access to land was not covered in the compensation policy. [43] Clearly, the compensation program of the LHWP fell short in both design and implementation.

Another facet of failure is the way that many of the cited benefits of the project ushered in detriments themselves. For example, one of the most heavily cited boons of the LHWP was the construction of infrastructure, specifically roads. Ideally, the roads would provide increased access to employment by reducing isolation. While the roads did reduce community isolation, this very development ironically harmed local economies. With the advent of easy outside access, the local market became flooded with cheap South African products and shops set up by outsiders with vehicles, cornering the market while locals found themselves unable to compete. [44] This phenomenon mirrors the way in which the majority of construction jobs were taken up by outsiders rather than affected locals; project-related jobs were incidentally another selling point for the LHWP. All in all, the image of a booming local economy and job market concocted by project designers was not represented by reality. In a greater sense, many results of the projected that were lauded as purely beneficial by the LHDA in reality harmed the livelihoods of local populations further. Yet again, the lack of foresight of project managers and investors is apparent.

The LHWP represents a highly complex and controversial issue with many convincing opinions arguing both for and against its merit. In fact, this paper only explores the tip of the iceberg, as many other facets of the project and its effects were not discussed. However, the intent of this article is not to argue whether the project is justified and/or necessary, but rather to bring to light many of its negative consequences on local populations who were already struggling immensely. As we have seen, many of the benefits cited by the Phase I website (i.e. road and job creation, etc….) have either benefitted rural populations less than expected or actively crippled them. Additionally, systemic corruption plaugued the LHWP from its inception, further undermining many of the positive goals and outcomes of the project. Given the many economic blessings of the LHWP, the complete lack of successful poverty reduction cuts especially deep; revenue from the project has completely failed to reach the people and areas that need it most.

All in all, the LHWP presents a perfect example of how large-scale infrastructure development—whether one finds it justified and/or necessary or not—can severely debilitate local populations who were already in a place of weakness. Additionally, while foreign investors may aim to feel exempt from any culpability by pointing to compensation measures, the measures are rarely comprehensive or effective enough to provide true relief. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project—through its pervasive corruption, elimination of various tangible resources, destruction of social paradigms, and ineffective compensation, actively exacerbated poor conditions for project-affected populations in Lesotho, ultimately leaving many impoverished people in a worse state than before.

This post may have been edited by admin for clarity and length.

Bibliography

Darroch, Fiona. “The Lesotho Highlands Water Project: Bribery on a Massive Scale”

Pambazuka News . Sep. 2, 2004. https://www.pambazuka.org/land-environment/lesotho-highlands-water-project-bribery-massive-scale.

Government of the Kingdom of Lesotho and Government of the Republic of South Africa. Treaty

of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project. 1986.

Hoover, Ryan. “Pipe Dreams: The World Bank’s Failed Efforts to Restore Lives and Livelihoods

of Dam-Affected People in Lesotho.” International Rivers Network (2001): 1-59.

https://web.archive.org/web/20070819071657/http://www.irn.org/programs/lesotho/pdf/pipedreams.pdf.

Lesotho Highlands Water Commission. LHWP Anti-Corruption Policy . 2011.

LHWP Phase I . Lesotho Highlands Development Authority, 2013. http://www.lhda.org.ls/Phase1/index.php.

Lesotho Highlands . Trans-Calderon Tunnel Authority, 2015.

Manwa, Haretebe. “Impacts of Lesotho Highlands Water Project on Sustainable Livelihoods.”

Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5, no. 15 (2014): 640-646.

http://www.mcser.org/journal/index.php/mjss/article/view/3273.

Mofokeng, Retsepile. “A Case Study of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, Phase 1”, University of Kwazulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg : 40-41.

Mwangi, Oscar. “Hydropolitics, Ecocide and Human Security in Lesotho: A Case Study of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project.” Journal of Southern African Studies , vol. 33, no.4, (2007): 3-17. DOI: 10.1080/03057070601136509.

Letsebe, Phoebe H. “A Study of the Impact of Lesotho Highlands Water Project on Residents of Khohlo-Ntso: Is It Too Late For Equitable Benefit Sharing?” University of the Witwatersand, (2012): 1-119. http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10539/12271/ Phoebe%20Harward%20Letsebe%20Thesis.pdf?sequence=2.

Van Niekerk, Peter. “Water from the Lesotho Highlands Water Project… Wasted?” Daily Maverick , May 4, 2018. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2018-05-04-water-from-the-lesotho-highlands-water-project-wasted/#.WvFbMqSFPIU .

Water Technology. “Lesotho Highlands Water Project” n.d https://www.water-technology.net/projects/lesotho-highlands/.

World Bank. “Project Performance Assessment Report – Lesotho Highlands Water Project, Phase 1B”, May 4, 2010: ii-xii.

[1] Hoover 1

[2] Manwa 640

[3] Water Technology

[4] Letsebe 46

[5] LHWP 1986 Treaty

[6] LHWP Phase I

[7] LHWP Phase I

[8] LHWP Phase I

[9] Hoover 1

[10] LHWP Phase I

[11] Van Niekerk

[12] LHWP Phase I

[13] Mofokeng 40

[14] Mofokeng 41

[15] Darroch

[16] Hoover 56

[17] Hoover 56

[18] Letsebe 2

[19] Letsebe 13

[20] Letsebe 27

[21] LHWP 1986 Treaty

[22] Letsebe 46

[23] Letsebe

[24] Hoover 54

[25] Hoover 28

[26] Hoover 28

[27] Hoover 29

[28] Mwangi 12

[29] Mwangi 12

[30] Mwangi 13

[31] Mwangi 13

[32] Mwangi 14

[33] Hoover 9

[34] Hoover 11

[35] Hoover 11

[36] Hoover 12

[37] Hoover 12

[38] Hoover 12

[39] Letsebe 48

[40] Letsebe 55

[41] Hoover 26

[42] Hoover 29

[43] Hoover 31

[44] Hoover 39

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Recent Posts

- A Look Into the Motive of Africa Freedom Mission

- The Water Distribution Efforts of Geoscientists Without Borders

- African Parks: How a New Approach to Conservation Impacts the Local Population

- Computer Aid International: The Reality of Donating Used Technology

- Zipline and its Implications on Data Colonialism

Recent Comments

- August 2021

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- November 2018

- August 2018

- Short Entries

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

Case Study: Lesotho Highland Water Project

The lesotho highland water project.

The Lesotho Highland Water Project is an example of a large-scale water transfer scheme. This project aims to solve the water shortage in South Africa.

How will the project work?

- 40% of the water from the Segu River in Lesotho will be transferred into the River Vaal in South Africa.

- The project plans to achieve this by using a combination of dams, reservoirs, pipelines, roads and bridges.

What are the impacts on Lesotho?

- Contributes 75% of Lesotho's GDP

- Provides hydro-electric power and improves sanitation

- 30,000 people had to move to make way for the first two dams

- The wetland ecosystem has been damaged

- Money that should have been used for compensation has disappeared due to corruption

What are the impacts on South Africa?

- Improves water security

- Reduces acidity of the Vaal River Reservoir

- Improves access to safe water

- Likely to cost US$4 billion

- 40% of water is lost through leaks

- Corruption has been a major issue

1 The Challenge of Natural Hazards

1.1 Natural Hazards

1.1.1 Types of Natural Hazards

1.1.2 Hazard Risk

1.1.3 Consequences of Natural Hazards

1.1.4 End of Topic Test - Natural Hazards

1.1.5 Exam-Style Questions - Natural Hazards

1.2 Tectonic Hazards

1.2.1 Tectonic Plates

1.2.2 Tectonic Plates & Convection Currents

1.2.3 Plate Margins

1.2.4 Volcanoes

1.2.5 Effects of Volcanoes

1.2.6 Responses to Volcanic Eruptions

1.2.7 Earthquakes

1.2.8 Earthquakes 2

1.2.9 Responses to Earthquakes

1.2.10 Case Studies: The L'Aquila & Kashmir Earthquakes

1.2.11 Earthquake Case Study: Chile 2010

1.2.12 Earthquake Case Study: Nepal 2015

1.2.13 Living with Tectonic Hazards 1

1.2.14 Living with Tectonic Hazards 2

1.2.15 End of Topic Test - Tectonic Hazards

1.2.16 Exam-Style Questions - Tectonic Hazards

1.2.17 Tectonic Hazards - Statistical Skills

1.3 Weather Hazards

1.3.1 Global Atmospheric Circulation

1.3.2 Surface Winds

1.3.3 UK Weather Hazards

1.3.4 Tropical Storms

1.3.5 Features of Tropical Storms

1.3.6 Impact of Tropical Storms 1

1.3.7 Impact of Tropical Storms 2

1.3.8 Tropical Storms Case Study: Katrina

1.3.9 Tropical Storms Case Study: Haiyan

1.3.10 UK Weather Hazards Case Study: Somerset 2014

1.3.11 End of Topic Test - Weather Hazards

1.3.12 Exam-Style Questions - Weather Hazards

1.3.13 Weather Hazards - Statistical Skills

1.4 Climate Change

1.4.1 Evidence for Climate Change

1.4.2 Causes of Climate Change

1.4.3 Effects of Climate Change

1.4.4 Managing Climate Change

1.4.5 End of Topic Test - Climate Change

1.4.6 Exam-Style Questions - Climate Change

1.4.7 Climate Change - Statistical Skills

2 The Living World

2.1 Ecosystems

2.1.1 Ecosystems

2.1.2 Ecosystem Cascades & Global Ecosystems

2.1.3 Ecosystem Case Study: Freshwater Ponds

2.2 Tropical Rainforests

2.2.1 Tropical Rainforests - Intro & Interdependence

2.2.2 Adaptations

2.2.3 Biodiversity of Tropical Rainforests

2.2.4 Deforestation

2.2.5 Case Study: Deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest

2.2.6 Sustainable Management of Rainforests

2.2.7 Case Study: Malaysian Rainforest

2.2.8 End of Topic Test - Tropical Rainforests

2.2.9 Exam-Style Questions - Tropical Rainforests

2.2.10 Deforestation - Statistical Skills

2.3 Hot Deserts

2.3.1 Overview of Hot Deserts

2.3.2 Biodiversity & Adaptation to Hot Deserts

2.3.3 Case Study: Sahara Desert

2.3.4 Desertification

2.3.5 Case Study: Thar Desert

2.3.6 End of Topic Test - Hot Deserts

2.3.7 Exam-Style Questions - Hot Deserts

2.4 Tundra & Polar Environments

2.4.1 Overview of Cold Environments

2.4.2 Adaptations in Cold Environments

2.4.3 Biodiversity in Cold Environments

2.4.4 Case Study: Alaska

2.4.5 Sustainable Management

2.4.6 Case Study: Svalbard

2.4.7 End of Topic Test - Tundra & Polar Environments

2.4.8 Exam-Style Questions - Cold Environments

3 Physical Landscapes in the UK

3.1 The UK Physical Landscape

3.1.1 The UK Physical Landscape

3.2 Coastal Landscapes in the UK

3.2.1 Types of Wave

3.2.2 Weathering & Mass Movement

3.2.3 Processes of Erosion & Wave-Cut Platforms

3.2.4 Headlands, Bays, Caves, Arches & Stacks

3.2.5 Transportation

3.2.6 Deposition

3.2.7 Spits, Bars & Sand Dunes

3.2.8 Case Study: Landforms on the Dorset Coast

3.2.9 Types of Coastal Management 1

3.2.10 Types of Coastal Management 2

3.2.11 Coastal Management Case Study - Holderness

3.2.12 Coastal Management Case Study: Swanage

3.2.13 Coastal Management Case Study - Lyme Regis

3.2.14 End of Topic Test - Coastal Landscapes in the UK

3.2.15 Exam-Style Questions - Coasts

3.3 River Landscapes in the UK

3.3.1 The River Valley

3.3.2 River Valley Case Study - River Tees

3.3.3 Erosion

3.3.4 Transportation & Deposition

3.3.5 Waterfalls, Gorges & Interlocking Spurs

3.3.6 Meanders & Oxbow Lakes

3.3.7 Floodplains & Levees

3.3.8 Estuaries

3.3.9 Case Study: The River Clyde

3.3.10 River Management

3.3.11 Hard & Soft Flood Defences

3.3.12 River Management Case Study - Boscastle

3.3.13 River Management Case Study - Banbury

3.3.14 End of Topic Test - River Landscapes in the UK

3.3.15 Exam-Style Questions - Rivers

3.4 Glacial Landscapes in the UK

3.4.1 Erosion

3.4.2 Landforms Caused by Erosion

3.4.3 Landforms Caused by Transportation & Deposition

3.4.4 Snowdonia

3.4.5 Land Use in Glaciated Areas

3.4.6 Tourism in Glacial Landscapes

3.4.7 Case Study - Lake District

3.4.8 End of Topic Test - Glacial Landscapes in the UK

3.4.9 Exam-Style Questions - Glacial Landscapes

4 Urban Issues & Challenges

4.1 Urban Issues & Challenges

4.1.1 Urbanisation

4.1.2 Urbanisation Case Study: Lagos

4.1.3 Urbanisation Case Study: Rio de Janeiro

4.1.4 UK Cities

4.1.5 Case Study: Urban Regen Projects - Manchester

4.1.6 Case Study: Urban Change in Liverpool

4.1.7 Case Study: Urban Change in Bristol

4.1.8 Sustainable Urban Life

4.1.9 End of Topic Test - Urban Issues & Challenges

4.1.10 Exam-Style Questions - Urban Issues & Challenges

4.1.11 Urban Issues -Statistical Skills

5 The Changing Economic World

5.1 The Changing Economic World

5.1.1 Measuring Development

5.1.2 Classifying Countries Based on Wealth

5.1.3 The Demographic Transition Model

5.1.4 Physical & Historical Causes of Uneven Development

5.1.5 Economic Causes of Uneven Development

5.1.6 How Can We Reduce the Global Development Gap?

5.1.7 Case Study: Tourism in Kenya

5.1.8 Case Study: Tourism in Jamaica

5.1.9 Case Study: Economic Development in India

5.1.10 Case Study: Aid & Development in India

5.1.11 Case Study: Economic Development in Nigeria

5.1.12 Case Study: Aid & Development in Nigeria

5.1.13 Economic Development in the UK

5.1.14 Economic Development UK: Industry & Rural

5.1.15 Economic Development UK: Transport & North-South

5.1.16 Economic Development UK: Regional & Global

5.1.17 End of Topic Test - The Changing Economic World

5.1.18 Exam-Style Questions - The Changing Economic World

5.1.19 Changing Economic World - Statistical Skills

6 The Challenge of Resource Management

6.1 Resource Management

6.1.1 Global Distribution of Resources

6.1.2 Food in the UK

6.1.3 Water in the UK 1

6.1.4 Water in the UK 2

6.1.5 Energy in the UK

6.1.6 Resource Management - Statistical Skills

6.2.1 Areas of Food Surplus & Food Deficit

6.2.2 Food Supply & Food Insecurity

6.2.3 Increasing Food Supply

6.2.4 Case Study: Thanet Earth

6.2.5 Creating a Sustainable Food Supply

6.2.6 Case Study: Agroforestry in Mali

6.2.7 End of Topic Test - Food

6.2.8 Exam-Style Questions - Food

6.2.9 Food - Statistical Skills

6.3.1 The Global Demand for Water

6.3.2 What Affects the Availability of Water?

6.3.3 Increasing Water Supplies

6.3.4 Case Study: Water Transfer in China

6.3.5 Sustainable Water Supply

6.3.6 Case Study: Kenya's Sand Dams

6.3.7 Case Study: Lesotho Highland Water Project

6.3.8 Case Study: Wakel River Basin Project

6.3.9 Exam-Style Questions - Water

6.3.10 Water - Statistical Skills

6.4.1 Global Demand for Energy

6.4.2 Factors Affecting Energy Supply

6.4.3 Increasing Energy Supply: Renewables

6.4.4 Increasing Energy Supply: Non-Renewables

6.4.5 Carbon Footprints & Energy Conservation

6.4.6 Case Study: Rice Husks in Bihar

6.4.7 Exam-Style Questions - Energy

6.4.8 Energy - Statistical Skills

Jump to other topics

Unlock your full potential with GoStudent tutoring

Affordable 1:1 tutoring from the comfort of your home

Tutors are matched to your specific learning needs

30+ school subjects covered

Case Study: Kenya's Sand Dams

Case Study: Wakel River Basin Project

Switch language:

- Advertise with us

- Water Supply

- Market Data

Lesotho Highlands Water Project

Project type, authorities, transfer tunnel between katse and mohale, design and supervising consultants, water transfer, katse dam and transfer tunnel supervisor, katse dam construction contractors, supervising engineers, contractors for tunnelling, muela hydropower station, electrical and mechanical contractors, equipment supplier, mohale dam supervisor, contractors, mechanical and engineering, matsoku weir and transfer tunnel, design and supervision consultants, construction contractors, mohale access roads, feasibility study contract.

The total water consumption in Lesotho is about 2m³/s, while the total availability is about 150m³/s.

Orange River flows about 2,000km westwards from the Drakensberg mountain region of Lesotho through South Africa.

The topography of the region will assist with the project, which will provide revenue for Lesotho and supply the country with hydroelectric power.

The total cost of the four-phase project is expected to be $8bn.

LHWP will have five dams and about 200km of tunnels and water transfer works constructed between the two countries.

Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) is the largest bi-national infrastructure project between Lesotho and South Africa. It involves the construction of an intricate network of tunnels and dams to divert water from the mountains of Lesotho to South Africa. It will provide water for South Africa and money and hydroelectricity for Lesotho.

Lesotho Highlands Water Commission (LHWC), previously known as the Joint Permanent Technical Commission, is a bi-national commission consisting of three delegates from each country. It is responsible for monitoring the project.

Lesotho Highlands Development Authority (LHDA) is responsible for the project’s overall implementation works such as dams, tunnels, power stations and infrastructure on Lesotho’s borders. It reports to LHWC.

Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority (TCTA) in South Africa is responsible for tunnelling, delivery, integration and flow control of water into the Ash River outfall in South African territory.

The project is being undertaken in phases. Phase one was completed in 2004 and was intended to supply water from Lesotho to South Africa. About 4.8 billion m³ of water had been transferred by 2007. Feasibility studies for phase two began in October 2005 and were completed in May 2008.

The second phase of the project has been approved by the Government of South Africa. Lesotho and South Africa signed an agreement in 2010 to undertake the project.

Phase II of the project is estimated to cost approximately $1bn (R7.3bn) and is projected to deliver water by January 2020.

Purpose of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project

Lesotho has abundant water resources that exceed requirements for possible future irrigation projects and development. The total water consumption in Lesotho is about 2m³/s, while the total availability is about 150m³/s.

Orange River flows about 2,000km westwards from the Drakensberg mountain region of Lesotho through South Africa into the Atlantic. About halfway along its length it is joined by the Vaal River, which flows from the north-east. The water has low sediment content and is of good chemical quality.

The topography of the region will assist with LHWP, which will provide a source of revenue for Lesotho and supply the country with hydroelectric power. The project will also accelerate development in the mountains.

Background of the Lesotho project

In the 1950s British High Commissioner to Lesotho Sir Evelyn Baring identified the LHWP as the most economical way of supplying water to South Africa. A feasibility study for the project was undertaken by the countries in 1978. A more detailed feasibility study was conducted by the Lahmeyer MacDonald Consortium between 1983 and 1986. The study found the project was economically viable and would allow hydroelectric power generation.

A treaty was signed by Lesotho and South Africa in October 1986 regarding the project design, construction, operation, maintenance and water transfer. South Africa agreed to pay the water transfer costs and Lesotho agreed to finance the hydroelectric power projects.

A detailed engineering and services analysis was undertaken for phase one, which involved phase 1A and phase 1B. Phase 1A required 2,800ha of rangeland and about 1,504ha of arable land and involved about 2,900 households being relocated. Phase 1B required 3,353ha of arable land and 3,434ha of rangeland and involved relocating 500 households.

Phase 1A included construction of the 185m-high double curvature concrete arch Katse Dam in the central Maluti Mountains and the 72MW Muela hydropower station. The dam has a storage capacity of 1,950 million m³ and a spillway discharge of 6,252m³/s. Phase 1A also involved building a 45km transfer tunnel and a 37km delivery tunnel.

Phase 1B involved construction of the 145m concrete-faced rock-fill Mohale Dam on the Senqunyane River.

The dam has a storage capacity of 958 million m³ and a spillway discharge of 2,600m³/s.

A 32km interconnecting transfer tunnel between the Katse and Mohale reservoirs was also built. Phase 1B included construction of the 19m-high Matsoku Weir and a 6.4km transfer tunnel. Mohale Dam was inaugurated in 2004.

Other phases

Phase II of the project includes construction of the 165m high Polihali Dam in the Mokhotlong district. It will be a concrete faced rock fill dam (CFRD) with a capacity to hold 2.2 billion m3 of water. A 38km water transfer tunnel running will be constructed to connect Polihali with Katse Reservoir. The second phase also includes a 1,000MW pump storage system.

During phase III the Tsoelike Dam will be constructed at the confluence of the Tsoelike and Senqu rivers, about 90km downstream from Mashai Dam. It will have a storage capacity of 2,223 million m³ and a pumping station. During phase IV the Ntoahae Dam and a pumping station will be built about 40km downstream from Tsoelike Dam on the Senqu River.

LHWP will have five dams and about 200km of tunnels and water transfer works constructed between the two countries. The project will transfer about 2,000 million m³ of water from Lesotho to South Africa every year.

Key players

The supervising engineer for construction of the Katse Dam and 45km transfer tunnel during phase 1A was Lesotho Highlands Consultants. The construction contractor was Highlands Water Ventures.

Construction of the Muela hydropower station and tunnelling was supervised by Lahmeyer MacDonald Consortium. Contractors for the tunnelling included Balfour Beatty, LTA, Spie Batignolle, Ed Züblin and Campenon Bernard. Electrical and mechanical work contractors included SDEM, Neyrpic and Deutsche Babcock. Equipment for Muela power station was provided by Kvaener Boving, Norelec and ABB Calor Emag Schaltanlagen.

The construction of Mohale Dam was supervised by Mohale Consultants Group. A joint venture of Concor Engineering, Hochtief and Impregilo (lead contractor) was formed for the project.

The mechanical and electrical works contract was awarded to an ATB joint venture. Lesotho Highlands Tunnel Partnership was the design and consultant supervisor for the transfer tunnel between Katse and Mohale. The contractors were Hochtief, Impregilo and Concor. The design and supervising consultant for Matsoku Weir and tunnel was Matsoku Diversion and Consult 4 partnership. The construction contractor was Matsoku Civil Contractors.

The phase two feasibility study contract was awarded to the C4-SEED joint venture. The venture consisted of companies from both countries: Consult4 of South Africa and Senqu Engineering Environment and Development Consultants of Lesotho.

The total cost of the four-phase project is expected to be $8bn. Phase 1A was expected to cost $2.5bn and phase 1B was expected to cost $1.5bn. The funds were issued by the World Bank, which also coordinates fund mobilisation from other financiers including the African Development Bank, the European Development Fund, Development Bank of South Africa, European commercial banks and several export credit agencies.

Company name

Die lösung der zukunft: die digitale verpackungswirtschaft in deutschland.

Your recommended content

Why we believe workplace health and wellness is important.

Download a free 10 page preview of our Mergers & Acquisitions in TMT – Thematic Research 2019 Report

Accelerating clinical trials : your recommended content, clinical trial continuity in asia-pacific during the covid-19 pandemic.

Future of Mining : Your recommended content

A sneak peek into canada’s largest transit expansion.

Precision medical wire : Your recommended content

Precision wire for vascular therapy: how exera® rises to the challenge.

Explore key mergers and acquisitions in the technology, media, and telecoms industry

Live revision! Join us for our free exam revision livestreams Watch now →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Geography news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Geography Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Topic Videos

Topic Video for AQA GCSE Geography: Water Transfer Case Study - Lesotho Highlands Water Project (Water Resources 5)

Last updated 25 May 2024

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

This topic video looks at the Lesotho Highlands Water Project that transfers water from Lesotho to South Africa, including details of the project, along with the benefits and drawbacks for both countries.

It is part of the AQA GCSE Geography course - Paper 2: Unit C - The Challenge of Resource Management.

You might also like

Topic video for aqa gcse geography: immediate and long-term responses to tectonic hazards (tectonic hazards 9), topic video for aqa gcse geography: human causes of climate change (climate change 4), topic video for aqa gcse geography: scale of deforestation (tropical rainforests 3), topic video for aqa gcse geography: challenges in svalbard (cold environments 4), topic video for aqa gcse geography: landforms of erosion - caves, arches, stacks and stumps (coastal landscapes 5), topic video for aqa gcse geography: food miles and carbon footprints (uk resource overview 2), topic video for aqa gcse geography: increasing food supply (food resources 4), topic video for aqa gcse geography: sustainable energy case study - nepal's micro-hydro plants (energy resources 7), our subjects.

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

Serving the hydro power and dam construction industries since 1949

Senqu Bridge construction reaches key milestone at Lesotho Highlands Water Project Phase II

- Share on Linkedin

- Share on Facebook

The construction of the Senqu Bridge, part of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) Phase II, marked a significant milestone on May 24 with the casting of the first deck segment on the northern abutment.

Spanning 825m and standing 90m high, the Senqu Bridge is the largest of three major bridges being built to cross the Polihali reservoir. It is also the first extradosed bridge in Lesotho. The design considers the harsh winter conditions in the Mokhotlong highlands.

The bridge deck is being constructed incrementally from both abutments to minimize disturbance and enhance worker safety. The deck segments are cast in 25m sections using shutter molds, then hydraulically jacked out over the gorge and connected midspan to form a continuous deck.

The Senqu Bridge construction contract, valued at approximately M2 billion, was awarded to the WRES Senqu Bridge Joint Venture in August 2022. The joint venture includes Webuild S.p.A. (Italy), Raubex Construction (South Africa), Enza Construction (South Africa), and Sigma Construction (Lesotho), with several sub-contractors from South Africa, Austria, and France.

Construction on the southern bank includes ongoing work on Piers 11 and 14, with concrete being delivered continuously to maintain progress. The cold temperatures in the Lesotho Highlands slow the concrete curing time, reducing the sliding rate of the piers.

Work on the bridge design started in 2018, led by Zutari (formerly Aurecon Lesotho). Zutari also designed the other two major bridges under Phase II, the Mabunyaneng and Khubelu bridges.

The Senqu Bridge is expected to be completed in early 2026. It is larger than the Mphorosane Bridge built during Phase I of the LHWP. The primary infrastructure projects of Phase II include the Polihali Dam and the Polihali Transfer Tunnel , which will significantly increase water transfer capacity to South Africa and enhance power generation at ‘Muela.

New roads and bridges are required to maintain access and connectivity across the reservoir. The major bridges program is complemented by the construction of four pedestrian bridges and six vehicle bridges, currently under procurement, to ensure mobility for communities in the reservoir area.

Sign up for our weekly news round-up!

Give your business an edge with our leading industry insights.

Partner Content

Afry switzerland ltd, afry india pvt. ltd, afry laos project office, afry australia pty ltd, more relevant, epupa decision due in 2000, geological studies shortlist potential dam sites in new zealand, update on vietnam, va tech hydro starts work in india, sign up to the newsletter: in brief, your corporate email address, i would also like to subscribe to:.

I consent to Verdict Media Limited collecting my details provided via this form in accordance with Privacy Policy

Thank you for subscribing

View all newsletters from across the Progressive Media network.

Resources you can trust

Take 10: Lesotho Highlands Water Project

A GCSE revision resource on the Lesotho Highlands Water Project using appealing black and white revision strips to help students learn and recall key information about the case study.

The colour photos in the PowerPoint can be used for retrieval practice as a starter. Students then cut out and annotate the strips of icons in the Word document and use a second strip to test their recall. They can use the icons to make connections between the facts as practice for writing coherent paragraphs in the exam-style questions provided. Assessment grids are included so students can mark their answers.

An extract from the resource:

Connect one idea to the next to create a chain of knowledge. For example:

- Lesotho is a small, mountainous country entirely surrounded by South Africa. What is the Lesotho Highlands Water Project?

- It transfers water from Lesotho to South Africa. What are its advantages for South Africa?

- South Africa has a large population but low rainfall – so it suffers frequent drought. And what are the project’s advantages for Lesotho?

- Lesotho has a small population but high rainfall – so lots of water to sell (around 75% of income). How big is the LHWP?

All reviews

Resources you might like.

Enter your search term

*Limited to most recent 250 articles Use advanced search to set an earlier date range

Sponsored by

Saving articles

Articles can be saved for quick future reference. This is a subscriber benefit. If you are already a subscriber, please log in to save this article. If you are not a subscriber, click on the View Subscription Options button to subscribe.

Article Saved

Contact us at [email protected]

Forgot Password

Please enter the email address that you used to subscribe on Engineering News. Your password will be sent to this address.

Content Restricted

This content is only available to subscribers

REAL ECONOMY NEWS

sponsored by

- LATEST NEWS

- LOADSHEDDING

- MULTIMEDIA LATEST VIDEOS REAL ECONOMY REPORTS SECOND TAKE AUDIO ARTICLES CREAMER MEDIA ON SAFM WEBINARS YOUTUBE

- SECTORS AGRICULTURE AUTOMOTIVE CHEMICALS CONSTRUCTION DEFENCE & AEROSPACE ECONOMY ELECTRICITY ENERGY ENVIRONMENTAL MANUFACTURING METALS MINING RENEWABLE ENERGY SERVICES TECHNOLOGY & COMMUNICATIONS TRADE TRANSPORT & LOGISTICS WATER

- SPONSORED POSTS

- ANNOUNCEMENTS

- BUSINESS THOUGHT LEADERSHIP

- MINING WEEKLY

- SHOWROOM PLUS

- PRODUCT PORTAL

- MADE IN SOUTH AFRICA

- PRESS OFFICE

- WEBINAR RECORDINGS

- COMPANY PROFILES

- VIRTUAL SHOWROOMS

- CREAMER MEDIA

- BACK COPIES

- BUSINESS LEADER

- SUPPLEMENTS

- FEATURES LIBRARY

- RESEARCH REPORTS

- PROJECT BROWSER

Article Enquiry

DWS assures it is ready for Lesotho Highlands tunnel closure

Email This Article

separate emails by commas, maximum limit of 4 addresses

As a magazine-and-online subscriber to Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly , you are entitled to one free research report of your choice . You would have received a promotional code at the time of your subscription. Have this code ready and click here . At the time of check-out, please enter your promotional code to download your free report. Email [email protected] if you have forgotten your promotional code. If you have previously accessed your free report, you can purchase additional Research Reports by clicking on the “Buy Report” button on this page. The most cost-effective way to access all our Research Reports is by subscribing to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa - you can upgrade your subscription now at this link .

The most cost-effective way to access all our Research Reports is by subscribing to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa - you can upgrade your subscription now at this link . For a full list of Research Channel Africa benefits, click here

If you are not a subscriber, you can either buy the individual research report by clicking on the ‘Buy Report’ button, or you can subscribe and, not only gain access to your one free report, but also enjoy all other subscriber benefits , including 1) an electronic archive of back issues of the weekly news magazine; 2) access to an industrial and mining projects browser; 3) access to a database of published articles; and 4) the ability to save articles for future reference. At the time of your subscription, Creamer Media’s subscriptions department will be in contact with you to ensure that you receive a copy of your preferred Research Report. The most cost-effective way to access all our Research Reports is by subscribing to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa - you can upgrade your subscription now at this link .

If you are a Creamer Media subscriber, click here to log in.

24th June 2024

By: Natasha Odendaal

Creamer Media Senior Deputy Editor

Font size: - +

The Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) is ready for the upcoming six-month closure of the Lesotho Highlands tunnel for maintenance from October until March 2025.

The department and relevant stakeholders in the water sector have taken all necessary measures to ensure that the water supply in Gauteng will not be affected during the shutdown, said DWS Gauteng provincial head Justice Maluleke .

“The main message is that we are ready for the tunnel closure and the public must not panic; we have all the plans in place, and we will be communicating”, he told delegates at a City Meets Business engagement session, hosted by the City of Ekurhuleni at the Alberton Civic Centre on June 21.

The department is working with all stakeholders from Lesotho, the Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority, Rand Water, the cities of Tshwane, Ekurhuleni and Johannesburg and other entities, and while there may be challenges along the way, Maluleke expressed confidence in the preparedness to handle any obstacles that may arise.

“In a worst-case scenario of shortage of water supply, the Integrated Vaal River System (IVRS) has 13 dams that supply water to the system. This is only at the worst-case scenario when the Vaal dam is around 18%, but since the closure will be during the rainy season, we do not anticipate that that is going to happen,” he said.

Maluleke assured businesses that they have nothing to worry about and further advised them to build on-site storage facilities for water in order to continue with their operations.

DWS system operation scientist manager Celiwe Ntuli supported Maluleke’s assertion by stating that the analysis shows no risk of water shortage in the IVRS.

Edited by Creamer Media Reporter

Research Reports

Latest Multimedia

Latest News

Leading condition monitoring specialists, WearCheck, help boost machinery lifespan and reduce catastrophic component failure through the scientific...

Your one-stop global energy-solution partner

sponsored by

Press Office

Announcements

Subscribe to improve your user experience...

Option 1 (equivalent of R125 a month):

Receive a weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa) Receive daily email newsletters Access to full search results Access archive of magazine back copies Access to Projects in Progress Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

Option 2 (equivalent of R375 a month):

All benefits from Option 1 PLUS Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports, in PDF format, on various industrial and mining sectors including Electricity; Water; Energy Transition; Hydrogen; Roads, Rail and Ports; Coal; Gold; Platinum; Battery Metals; etc.

Already a subscriber?

Forgotten your password?

MAGAZINE & ONLINE

R1500 (equivalent of R125 a month)

Receive weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

Access to full search results

Access archive of magazine back copies

Access to Projects in Progress

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

RESEARCH CHANNEL AFRICA

R4500 (equivalent of R375 a month)

All benefits from Option 1

Electricity

Energy Transition

Roads, Rail and Ports

Battery Metals

CORPORATE PACKAGES

Discounted prices based on volume

Receive all benefits from Option 1 or Option 2 delivered to numerous people at your company

Intranet integration access to all in your organisation

DWS assures business communities of enough water supply amidst the closure of Lesotho Highlands tunnel for maintenance

- Loadshedding

- South African News

- African News

- International News

- All Opinions

- Latest Opinions

- Raymond Suttner - Suttner's View

- Politics 360 - Ebrahim Fakir

- Institute for Security Studies

- South African Institute of International Affairs

- Saliem Fakir - Low Carbon Future

- The Conversation

- Real Economy

- Other Opinions

- Author Interviews

- All Legislation

- Constitution

- Audio Articles

- Recommendations

- All Case Law

- Constitutional Court

- Supreme Court of Appeal

- High Courts

- All Legal Briefs

- Company Posts

- Legal Notice

Note: Search is limited to the most recent 250 articles. To access earlier articles, click Advanced Search and set an earlier date range. To search for a term containing the '&' symbol, click Advanced Search and use the 'search headings' and/or 'in first paragraph' options.

And must exclude these words...

Sponsored by

Please enter the email address that you used to register on Polity.org.za. Your password will be sent to this address.

Email this article

separate emails by commas, maximum limit of 4 addresses

Article Enquiry

Embed video.

24th June 2024

ARTICLE ENQUIRY SAVE THIS ARTICLE EMAIL THIS ARTICLE

Font size: - +

/ MEDIA STATEMENT / The content on this page is not written by Polity.org.za, but is supplied by third parties. This content does not constitute news reporting by Polity.org.za.

The Provincial Head of Department of Water and Sanitation in Gauteng, Justice Maluleke has reassured the public about the readiness of the Department and sector stakeholders for the impending closure of the Lesotho Highlands during the City Meets Business Engagement Session, hosted by the City of Ekurhuleni at the Alberton Civic Centre on Friday, 21 June 2024. The session focused on responsible water usage for business continuity.

The Provincial Head confirmed that the Department and relevant stakeholders in the water sector have taken all necessary measures to ensure that the water supply will not be affected by the closure of the Lesotho tunnel which will commence in October this year until March 2025.

“The main message is that we are ready for the tunnel closure and the public must not panic we have all the plans in place, and we will be communicating”, He said.

According to Maluleke, the Department is working with all stakeholders from Lesotho, the TCTA, Rand Water, City of Tshwane, City of Ekurhuleni, and the City of Johannesburg and entities to ensure no water shortage in the province during the shutdown of the Lesotho tunnel. While Maluleke acknowledged that there may be challenges along the way, he expressed confidence in their preparedness to handle any obstacles that may arise.

“In a worst-case scenario of shortage of water supply, the Integrated Vaal River System has 13 dams that supply water to the Vaal River system. This is only at the worst-case scenario when the Vaal dam is around 18%, but since the closure will be during the rainy season, we don’t anticipate that that is going to happen”, Maluleke said.

Mr Maluleke has assured businesses that they have nothing to worry about and further advised them to build on-site storage facilities for water in order to continue with their operations.

Celiwe Ntuli, Scientist Manager from System Operation at the National Department of Water and Sanitation, supported Maluleke’s assertion by stating that the analysis shows no risk of water shortage in the Integrated Vaal River System (IVRS).

During her presentation, Ms. Ntuli mentioned that Phase 1 of the Lesotho Highlands transfers 700 million cubic meters of water per year into the Integrated Vaal River System (IVRS). Phase 2 project will add 490 million cubic meters per year into the IVRS.

According to the treaty signed between Lesotho and South Africa in 1996, maintenance is required every five to ten years. The last maintenance was conducted in 2019, during which the need for Phase 2 was discovered.

In conclusion, Justice Maluleke's reassurance at the City Meets Business session underscores the Department of Water and Sanitation's commitment to ensuring the sustainable water supply for Gauteng province and beyond in the face of the Lesotho Highlands closure.

Issued by the Department of Water & Sanitation

EMAIL THIS ARTICLE SAVE THIS ARTICLE ARTICLE ENQUIRY

To subscribe email [email protected] or click here To advertise email [email protected] or click here

Related Articles

- DWS set to submit NWRIA Bill to Presidency →

- LHWP tunnel closure won’t have significant impact on water supplies, assures DWS →

Polity.org.za is a product of Creamer Media. www.creamermedia.co.za

Other Creamer Media Products include: Engineering News Mining Weekly Research Channel Africa

Newsletters

Sign up for our FREE daily email newsletter

Subscriptions

We offer a variety of subscriptions to our Magazine, Website, PDF Reports and our photo library.

Subscriptions are available via the Creamer Media Store.

Advertising on Polity.org.za is an effective way to build and consolidate a company's profile among clients and prospective clients. Email [email protected]

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) is a large-scale water transfer scheme where water is diverted from the highlands of Lesotho to South Africa's Free State and the greater Johannesburg area, which desperately needs water. This is mainly due to these regions' rapidly growing population and industrial demands.

Lesotho: A Case Study of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project* Oscar Mwangi (National University of Lesotho) The Lesotho Highlands Water Project is a bi-national collaboration between Lesotho and South Africa. One of the most comprehensive water projects in the world it aims to harness the water resources of Lesotho to the mutual benefit of both ...

The article examines the origins, goals, and outcomes of the LHWP, a large-scale water development project between Lesotho and South Africa. It reveals how the project has harmed rural communities in Lesotho through corruption, resource loss, social disruption, and ineffective compensation.

Lesotho (an LIC) is a landlocked country, which is entirely surrounded by South Africa. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project is an example of a large-scale water transfer scheme, taking water from Lesotho to South Africa, and is the largest water transfer scheme in Africa, taking 30 years to complete. Lesotho is a mountainous country that receives a high level of precipitation and has a low ...

The Lesotho Highland Water Project is an example of a large-scale water transfer scheme. This project aims to solve the water shortage in South Africa. ... 6.3.7 Case Study: Lesotho Highland Water Project. 6.3.8 Case Study: Wakel River Basin Project. 6.3.9 Exam-Style Questions - Water. 6.3.10 Water - Statistical Skills. 6.4 Energy. 6.4.1 Global ...

CASE STUDY The Highlands Water Project in Lesotho -water supply and hydroelectricity Lesotho is an LEDC in southern Africa with an abundance of water. It is completely surrounded by South Africa, which is a much richer country and also short of water. This circumstance has led to the ambitious Lesotho Highlands

Lesotho is one of the 20% worst countries in the world for wealth inequality. Some of the population profit from diamond mining, whereas others remain unemployed and in extreme poverty. Therefore, in 2004, the government decided to trade surplus water with neighbouring South Africa to improve its economy and development. Source: SABC News.

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) is an ongoing water supply project with a hydropower component, ... After a feasibility study was conducted between August 1983 and August 1986 by the German-British Lahmeyer MacDonald Consortium, the project eventually began to be realized.

Abstract Between 1989 and 2007 the World Bank was. one of the funders of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project in. southern Afr ica. This project, which included two large dams. (Katse and Mohale ...

The Lesotho Highlands Water Project was initiated in 1986 as a result of discussions between the governments of the Kingdom of Lesotho and the Republic of South Africa (SA) that, together with ...