- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

The Power of Playful Learning in the Early Childhood Setting

You are here

Play versus learning represents a false dichotomy in education (e.g., Hirsh-Pasek & Golinkoff 2008). In part, the persistent belief that learning must be rigid and teacher directed—the opposite of play—is motivated by the lack of a clear definition of what constitutes playful learning (Zosh et al. 2018). And, in part, it is motivated by older perceptions of play and learning. Newer research, however, allows us to reframe the debate as learning via play—as playful learning.

This piece, which is an excerpt from Chapter 5 in Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8, Fourth Edition (NAEYC 2022), suggests that defining play on a spectrum (Zosh et al. 2018, an idea first introduced by Bergen 1988) helps to resolve old divisions and provides a powerful framework that puts playful learning —rich curriculum coupled with a playful pedagogy—front and center as a model for all early childhood educators. ( See below for a discussion of play on a spectrum.)

This excerpt also illustrates the ways in which play and learning mutually support one another and how teachers connect learning goals to children’s play. Whether solitary, dramatic, parallel, social, cooperative, onlooker, object, fantasy, physical, constructive, or games with rules, play, in all of its forms, is a teaching practice that optimally facilitates young children’s development and learning. By maximizing children’s choice, promoting wonder and enthusiasm for learning, and leveraging joy, playful learning pedagogies support development across domains and content areas and increase learning relative to more didactic methods (Alfieri et al. 2011; Bonawitz et al. 2011; Sim & Xu 2015).

Playful Learning: A Powerful Teaching Tool

This narrowing of the curriculum and high-stakes assessment practices (such as paper-and-pencil tests for kindergartners) increased stress on educators, children, and families but failed to deliver on the promise of narrowing—let alone closing—the gap. All children need well-thought-out curricula, including reading and STEM experiences and an emphasis on executive function skills such as attention, impulse control, and memory (Duncan et al. 2007). But to promote happy, successful, lifelong learners, children must be immersed in developmentally appropriate practice and rich curricular learning that is culturally relevant (NAEYC 2020). Playful learning is a vehicle for achieving this. Schools must also address the inequitable access to play afforded to children (see “Both/And: Early Childhood Education Needs Both Play and Equity,” by Ijumaa Jordan.) All children should be afforded opportunities to play, regardless of their racial group, socioeconomic class, and disability if they have been diagnosed with one. We second the call of Maria Souto-Manning (2017): “Although play has traditionally been positioned as a privilege, it must be (re)positioned as a right, as outlined by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 31” (785).

What Is Playful Learning?

Playful learning describes a learning context in which children learn content while playing freely (free play or self-directed play), with teacher guidance (guided play), or in a structured game. By harnessing children’s natural curiosity and their proclivities to experiment, explore, problem solve, and stay engaged in meaningful activities—especially when doing so with others—teachers maximize learning while individualizing learning goals. Central to this concept is the idea that teachers act more as the Socratic “guide at the side” than a “sage on the stage” (e.g., King 1993, 30; Smith 1993, 35). Rather than view children as empty vessels receiving information, teachers see children as active explorers and discoverers who bring their prior knowledge into the learning experience and construct an understanding of, for example, words such as forecast and low pressure as they explore weather patterns and the science behind them. In other words, teachers support children as active learners.

Importantly, playful learning pedagogies naturally align with the characteristics that research in the science of learning suggests help humans learn. Playful learning leverages the power of active (minds-on), engaging (not distracting), meaningful, socially interactive, and iterative thinking and learning (Zosh et al. 2018) in powerful ways that lead to increased learning.

Free play lets children explore and express themselves—to be the captains of their own ship. While free play is important, if a teacher has a learning goal, guided play and games are the road to successful outcomes for children (see Weisberg, Hirsh-Pasek, & Golinkoff 2013 for a review). Playful learning in the form of guided play, in which the teacher builds in the learning as part of a fun context such as a weather report, keeps the child’s agency but adds an intentional component to the play that helps children learn more from the experience. In fact, when researchers compared children’s skill development during free play in comparison to guided play, they found that children learned more vocabulary (Toub et al. 2018) and spatial skills (Fisher et al. 2013) in guided play than in free play.

Self-Directed Play, Free Play

NAEYC’s 2020 position statement on developmentally appropriate practice uses the term self-directed play to refer to play that is initiated and directed by children. Such play is termed free play in the larger works of the authors of this excerpt; therefore, free play is the primary term used in this article, with occasional references to self-directed play, the term used in the rest of the DAP book.

Imagine an everyday block corner. The children are immersed in play with each other—some trying to build high towers and others creating a tunnel for the small toy cars on the nearby shelves. But what if there were a few model pictures on the wall of what children could strive to make as they collaborated in that block corner? Might they rotate certain pieces purposely? Might they communicate with one another that the rectangle needs to go on top of the square? Again, a simple insertion of a design that children can try to copy turns a play situation into one ripe with spatial learning. Play is a particularly effective way to engage children with specific content learning when there is a learning goal.

Why Playful Learning Is Critical

Teachers play a crucial role in creating places and spaces where they can introduce playful learning to help all children master not only content but also the skills they will need for future success. The science of learning literature (e.g., Fisher et al. 2013; Weisberg, Hirsh-Pasek, & Golinkoff 2013; Zosh et al. 2018) suggests that playful learning can change the “old equation” for learning, which posited that direct, teacher-led instruction, such as lectures and worksheets, was the way to achieve rich content learning. This “new equation” moves beyond a sole focus on content and instead views playful learning as a way to support a breadth of skills while embracing developmentally appropriate practice guidelines (see Hirsh-Pasek et al. 2020).

Using a playful learning pedagogical approach leverages the skill sets of today’s educators and enhances their ability to help children attain curricular goals. It engages what has been termed active learning that is also developmentally appropriate and offers a more equitable way of engaging children by increasing access to participation. When topics are important and culturally relevant to children, they can better identify with the subject and the learning becomes more seamless.

While educators of younger children are already well versed in creating playful and joyful experiences to support social goals (e.g., taking turns and resolving conflicts), they can use this same skill set to support more content-focused curricular goals (e.g., mathematics and literacy). Similarly, while teachers of older children have plenty of experience determining concrete content-based learning goals (e.g., attaining Common Core Standards), they can build upon this set of skills and use playful learning as a pedagogy to meet those goals.

Learning Through Play: A Play Spectrum

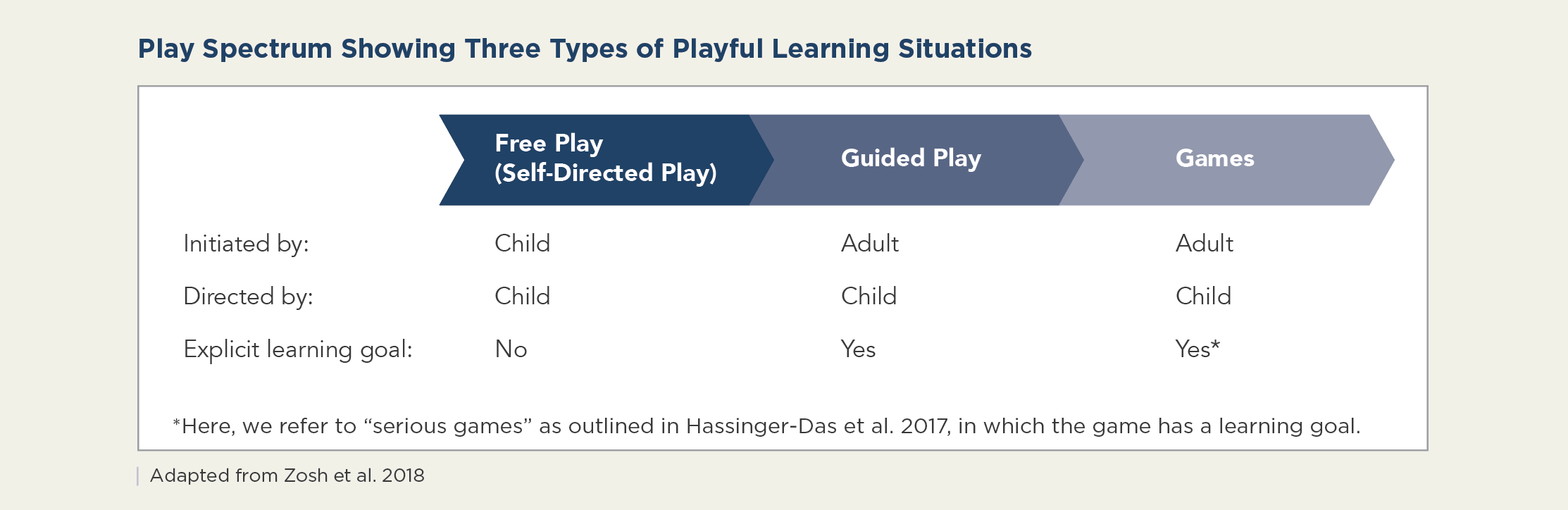

As noted previously, play can be thought of as lying on a spectrum that includes free play (or self-directed play), guided play, games, playful instruction, and direct instruction (Bergen 1988; Zosh et al. 2018). For the purposes of this piece, we use a spectrum that includes the first three of these aspects of playful learning, as illustrated in “Play Spectrum Showing Three Types of Playful Learning Situations” below.

The following variables determine the degree to which an activity can be considered playful learning:

- level of adult involvement

- extent to which the child is directing the learning

- presence of a learning goal

Toward the left end of the spectrum are activities with more child agency, less adult involvement, and loosely defined or no particular learning goals. Further to the right, adults are more involved, but children still direct the activity or interaction.

Developmentally appropriate practice does not mean primarily that children play without a planned learning environment or learn mostly through direct instruction (NAEYC 2020). Educators in high-quality early childhood programs offer a range of learning experiences that fall all along this spectrum. By thinking of play as a spectrum, educators can more easily assess where their learning activities and lessons fall on this spectrum by considering the components and intentions of the lesson. Using their professional knowledge of how children develop and learn, their knowledge of individual children, and their understanding of social and cultural contexts, educators can then begin to think strategically about how to target playful learning (especially guided play and games) to leverage how children naturally learn. This more nuanced view of play and playful learning can be used to both meet age-appropriate learning objectives and support engaged, meaningful learning.

In the kindergarten classroom in the following vignette, children have ample time for play and exploration in centers, where they decide what to play with and what they want to create. These play centers are the focus of the room and the main tool for developing social and emotional as well as academic skills; they reflect and support what the children are learning through whole-group discussions, lessons, and skills-focused stations. In the vignette, the teacher embeds guided play opportunities within the children’s free play.

Studying Bears: Self-Directed Play that Extends What Kindergartners Are Learning

While studying the habits of animals in winter, the class is taking a deeper dive into the lives of American black bears, animals that make their homes in their region. In the block center, one small group of children uses short lengths and cross-sections of real tree branches as blocks along with construction paper to create a forest habitat for black bear figurines. They enlist their friends in the art center to assist in making trees and bushes. Two children are in the writing center. Hearing that their friends are looking for help to create a habitat, they look around and decide a hole punch and blue paper are the perfect tools for making blueberries—a snack black bears love to eat! Now multiple centers and groups of children are involved in making the block center become a black bear habitat.

In the dramatic play center, some of the children pretend to be bear biologists, using stethoscopes, scales, and magnifying glasses to study the health of a couple of plush black bears. When these checkups are complete, the teacher suggests the children could describe the bears’ health in a written “report,” thus embedding guided play within their free play. A few children at the easels in the art center are painting pictures of black bears.

Contributed by Amy Blessing

Free play, or self-directed play, is often heralded as the gold standard of play. It encourages children’s initiative, independence, and problem solving and has been linked to benefits in social and emotional development (e.g., Singer & Singer 1990; Pagani et al. 2010; Romano et al. 2010; Gray 2013) and language and literacy (e.g., Neuman & Roskos 1992). Through play, children explore and make sense of their world, develop imaginative and symbolic thinking, and develop physical competence. The kindergarten children in the example above were developing their fine motor and collaboration skills, displaying their understanding of science concepts (such as the needs of animals and living things), and exercising their literacy and writing skills. Such benefits are precisely why free play has an important role in developmentally appropriate practice. To maximize learning, teachers also provide guided play experiences.

Guided Play

While free play has great value for children, empirical evidence suggests that it is not always sufficient when there is a pedagogical goal at stake (Smith & Pellegrini 2008; Alfieri et al. 2011; Fisher et al. 2013; Lillard 2013; Weisberg, Hirsh-Pasek, & Golinkoff 2013; Toub et al. 2018). This is where guided play comes in.

Guided play allows teachers to focus children’s play around specific learning goals (e.g., standards-based goals), which can be applied to a variety of topics, from learning place value in math to identifying rhyming words in literacy activities. Note, however, that the teacher does not take over the play activity or even direct it. Instead, she asks probing questions that guide the next level of child-directed exploration. This is a perfect example of how a teacher can initiate a context for learning while still leaving the child in charge. In the previous kindergarten vignette, the teacher guided the children in developing their literacy skills as she embedded writing activities within the free play at the centers.

Facilitating Guided Play

Skilled teachers set up environments and facilitate development and learning throughout the early childhood years, such as in the following:

- Ms. Taglieri notices what 4-month-old Anthony looks at and shows interest in. Following his interest and attention, she plays Peekaboo, adjusting her actions (where she places the blanket and peeks out at him) to maintain engagement.

- Ms. Eberhard notices that 22-month-old Abe knows the color yellow. She prepares her environment based on this observation, placing a few yellow objects along with a few red ones on a small table. Abe immediately goes to the table, picking up each yellow item and verbally labeling them (“Lellow!”).

- Mr. Gorga creates intrigue and participation by inviting his preschool class to “be shape detectives” and to “discover the secret of shapes.” As the children explore the shapes, Mr. Gorga offers questions and prompts to guide children to answer the question “What makes them the same kind of shapes?”

An analogy for facilitating guided play is bumper bowling. If bumpers are in place, most children are more likely than not to knock down some pins when they throw the ball down the lane. That is different than teaching children exactly how to throw it (although some children, such as those who have disabilities or who become frustrated if they feel a challenge is too great, may require that level of support or instruction). Guided play is not a one-size-fits-all prescriptive pedagogical technique. Instead, teachers match the level of support they give in guided play to the children in front of them.

Critically, many teachers already implement these kinds of playful activities. When the children are excited by the birds they have seen outside of their window for the past couple of days, the teachers may capitalize on this interest and provide children with materials for a set of playful activities about bird names, diets, habitats, and songs. Asking children to use their hands to mimic an elephant’s trunk when learning vocabulary can promote learning through playful instruction that involves movement. Similarly, embedding vocabulary in stories that are culturally relevant promotes language and early literacy development (García-Alvarado, Arreguín, & Ruiz-Escalante 2020). For example, a teacher who has several children in his class with Mexican heritage decides to read aloud Too Many Tamales (by Gary Soto, illus. Ed Martinez) and have the children reenact scenes from it, learning about different literary themes and concepts through play. The children learn more vocabulary, have a better comprehension of the text, and see themselves and their experiences reflected. The teacher also adds some of the ingredients and props for making tamales into the sociodramatic play center (Salinas-González, Arreguín-Anderson, & Alanís 2018) and invites families to share stories about family tamaladas (tamale-making parties).

Evidence Supporting Guided Play as a Powerful Pedagogical Tool

Evidence from the science of learning suggests that discovery-based guided play actually results in increased learning for all children relative to both free play and direct instruction (see Alferi et al. 2011). These effects hold across content areas including spatial learning (Fisher et al. 2013), literacy (Han et al. 2010; Nicolopoulou et al. 2015; Hassinger-Das et al. 2016; Cavanaugh et al. 2017; Toub et al. 2018; Moedt & Holmes 2020), and mathematics (Zosh et al. 2016).

There are several possible reasons for guided play’s effectiveness. First, it harnesses the joy that is critical to creativity and learning (e.g., Isen, Daubman, & Nowicki 1987; Resnick 2007). Second, during guided play, the adults help “set the stage for thought and action” by essentially limiting the number of possible outcomes for the children so that the learning goal is discoverable, but children still direct the activity (Weisberg et al. 2014, 276). Teachers work to provide high-quality materials, eliminate distractions, and prepare the space, but then, critically, they let the child play the active role of construction. Third, in guided play, the teacher points the way toward a positive outcome and hence lessens the ambiguity (the degrees of freedom) without directing children to an answer or limiting children to a single discovery (e.g., Bonawitz et al. 2011). And finally, guided play provides the opportunity for new information to be integrated with existing knowledge and updated as children explore.

Reinforcing Numeracy with a Game

The children in Mr. Cohen’s preschool class are at varying levels of understanding in early numeracy skills (e.g., cardinality, one-to-one correspondence, order irrelevance). He knows that his children need some practice with these skills but wants to make the experience joyful while also building these foundational skills. One day, he brings out a new game for them to play—The Great Race. Carla and Michael look up expectantly, and their faces light up when they realize they will be playing a game instead of completing a worksheet. The two quickly pull out the box, setting up the board and choosing their game pieces. Michael begins by flicking the spinner with his finger, landing on 2. “Nice!” Carla exclaims, as Michael moves his game piece, counting “One, two.” Carla takes a turn next, spinning a 1 and promptly counting “one” as she moves her piece one space ahead. “My turn!” Michael says, eager to win the race. As he spins a 2, he pauses. “One . . . two,” he says, hesitating, as he moves his piece to space 4 on the board. Carla corrects him, “I think you mean ‘three, four,’ right? You have to count up from where you are on the board.” Michael nods, remembering the rules Mr. Cohen taught him earlier that day. “Right,” he says, “three, four.”

Similar to guided play, games can be designed in ways that help support learning goals (Hassinger-Das et al. 2017). In this case, instead of adults playing the role of curating the activity, the games themselves provide this type of external scaffolding. The example with Michael and Carla shows how children can learn through games, which is supported by research. In one well-known study, playing a board game (i.e., The Great Race) in which children navigated through a linear, numerical-based game board (i.e., the game board had equally spaced game spaces that go from left to right) resulted in increased numerical development as compared to playing the same game where the numbers were replaced by colors (Siegler & Ramani 2008) or with numbers organized in a circular fashion (Siegler & Ramani 2009). Structuring experiences so that the learning goal is intertwined naturally with children’s play supports their learning. A critical point with both guided play and games is that children are provided with support but still lead their own learning.

Digital educational games have become enormously popular, with tens of thousands of apps marketed as “educational,” although there is no independent review of these apps. Apps and digital games may have educational value when they inspire active, engaged, meaningful, and socially interactive experiences (Hirsh-Pasek et al. 2015), but recent research suggests that many of the most downloaded educational apps do not actually align with these characteristics that lead to learning (Meyer et al. 2021). Teachers should exercise caution and evaluate any activity—digital or not—to see how well it harnesses the power of playful learning.

Next Steps for Educators

Educators are uniquely positioned to prepare today’s children for achievement today and success tomorrow. Further, the evidence is mounting that playful pedagogies appear to be an accessible, powerful tool that harnesses the pillars of learning. This approach can be used across ages and is effective in learning across domains.

By leveraging children’s own interests and mindfully creating activities that let children play their way to new understanding and skills, educators can start using this powerful approach today. By harnessing the children’s interests at different ages and engaging them in playful learning activities, educators can help children learn while having fun. And, importantly, educators will have more fun too when they see children happy and engaged.

As the tide begins to change in individual classrooms, educators need to acknowledge that vast inequalities (e.g., socioeconomic achievement gaps) continue to exist (Kearney & Levine 2016). The larger challenge remains in propelling a cultural shift so that administrators, families, and policymakers understand the way in which educators can support the success of all children through high-quality, playful learning experiences.

Consider the following reflection questions as you reflect how to support equitable playful learning experiences for each and every child:

- One of the best places to start is by thinking about your teaching strengths. Perhaps you are great at sparking joy and engagement. Or maybe you are able to frequently leverage children’s home lives in your lessons. How can you expand practices you already use as an educator or are learning about in your courses to incorporate the playful learning described in this article?

- How can you share the information in this chapter with families, administrators, and other educators? How can you help them understand how play can engage children in deep, joyful learning?

This piece is excerpted from NAEYC’s recently published book Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth Through Age 8, Fourth Edition. For more information about the book, visit NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/books/dap-fourth-edition .

Teaching Play Skills

Pamela Brillante

While many young children with autism spectrum disorder enjoy playing, they can have difficulty engaging in traditional play activities. They may engage in activities that do not look like ordinary play, including playing with only a few specific toys or playing in a specific, repetitive way.

Even though most children learn play skills naturally, sometimes families and teachers have to teach children how to play. Learning how to play will help develop many other skills young children need for the future, including

- social skills: taking turns, sharing, and working cooperatively

- cognitive skills: problem-solving skills, early academic skills

- communication skills: responding to others, asking questions

- physical skills: body awareness, fine and gross motor coordination

Several evidence-based therapeutic approaches to teaching young children with autism focus on teaching play skills, including

- The Play Project: https://playproject.org

- The Greenspan Floortime approach: https://stanleygreenspan.com

- Integrated Play Group (IPG) Model: www.wolfberg.com

While many children with autism have professionals and therapists working with them, teachers and families should work collaboratively and provide multiple opportunities for children to practice new skills and engage in play at their own level. For example, focus on simple activities that promote engagement between the adult and the child as well as the child and their peers without disabilities, including playing with things such as bubbles, cause-and-effect toys, and interactive books. You can also use the child’s preferred toy in the play, like having the Spider-Man figure be the one popping the bubbles.

Pamela Brillante , EdD, has spent 30 years working as a special education teacher, administrator, consultant, and professor. In addition to her full-time faculty position in the Department of Special Education, Professional Counseling and Disability Studies at William Paterson University of New Jersey, Dr. Brillante continues to consult with school districts and present to teachers and families on the topic of high-quality, inclusive early childhood practices.

Photographs: © Getty Images Copyright © 2022 by the National Association for the Education of Young Children. See Permissions and Reprints online at NAEYC.org/resources/permissions .

Alfieri, L., P.J. Brooks, N.J. Aldrich, & H.R. Tenenbaum. 2011. “Does Discovery-Based Instruction Enhance Learning?” Journal of Educational Psychology 103 (1): 1–18.

Bassok, D., S. Latham, & A. Rorem. 2016. “Is Kindergarten the New First Grade?” AERA Open 2 (1): 1–31. doi.10.1177/2332858415616358.

Bergen, D., ed. 1988. Play as a Medium for Learning and Development: A Handbook of Theory and Practice . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann Educational Books.

Bonawitz, E.B., P. Shafto, H. Gweon, N.D. Goodman, E.S. Spelke, & L. Schulz. 2011. “The Double-Edged Sword of Pedagogy: Instruction Limits Spontaneous Exploration and Discovery.” Cognition 120 (3): 322–30.

Cavanaugh, D.M., K.J. Clemence, M.M. Teale, A.C. Rule, & S.E. Montgomery. 2017. “Kindergarten Scores, Storytelling, Executive Function, and Motivation Improved Through Literacy-Rich Guided Play.” Journal of Early Childhood Education 45 (6): 1–13.

Christakis, E. 2016. The Importance of Being Little: What Preschoolers Really Need from Grownups . New York: Penguin Books.

Duncan, G. J., A. Claessens, A.C. Huston, L.S. Pagani, M. Engel, H. Sexton, C.J. Dowsett, K. Magnuson, P. Klebanov, L. Feinstein, J. Brooks-Gunn, K. Duckworth, & C. Japel. 2007. “School Readiness and Later Achievement.” Developmental Psychology 43 (6): 1428–46. https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1428 .

Fisher, K.R., K. Hirsh-Pasek, N. Newcombe, & R.M. Golinkoff. 2013. “Taking Shape: Supporting Preschoolers’ Acquisition of Geometric Knowledge Through Guided Play.” Child Development 84 (6): 1872–78.

García-Alvarado, S., M.G. Arreguín, & J.A. Ruiz-Escalante. 2020. “Mexican-American Preschoolers as Co-Creators of Zones of Proximal Development During Retellings of Culturally Relevant Stories: A Participatory Study.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy : 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1468798420930339 .

Gray, P. 2013. Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life . New York: Basic Books.

Han, M., N. Moore, C. Vukelich, & M. Buell. 2010. “Does Play Make a Difference? How Play Intervention Affects the Vocabulary Learning of At-Risk Preschoolers.” American Journal of Play 3 (1): 82–105.

Hannaway, J., & L. Hamilton. 2008. Accountability Policies: Implications for School and Classroom Practices . Washington, DC: Urban Institute. http://webarchive.urban.org/publications/411779.html .

Hassinger-Das, B., K. Ridge, A. Parker, R.M. Golinkoff, K. Hirsh-Pasek, & D.K. Dickinson. 2016. “Building Vocabulary Knowledge in Preschoolers Through Shared Book Reading and Gameplay.” Mind, Brain, and Education 10 (2): 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12103 .

Hassinger-Das, B., T.S. Toub, J.M. Zosh, J. Michnick, R. Golinkoff, & K. Hirsh-Pasek. 2017. “More Than Just Fun: A Place for Games in Playful Learning.” Infancia y aprendizaje: Journal for the Study of Education and Development 40 (2): 191–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2017.1292684 .

Hirsh-Pasek, K., & R.M. Golinkoff. 2008. “Why Play = Learning.” In Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online], eds. R.E. Tremblay, M. Boivin, & R.D. Peters, topic ed. P.K. Smith, 1–6. Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development and Strategic Knowledge Cluster on Early Child Development. www.child-encyclopedia.com/play/according-experts/why-play-learning .

Hirsh-Pasek, K., H. S. Hadani, E. Blinkoff, & R. M. Golinkoff. 2020. A new path to education reform: Playful learning promotes 21st-century skills in schools and beyond . The Brookings Institution: Big Ideas Policy Report. www.brookings.edu/policy2020/bigideas/a-new-path-to-education-reform-playful-learning-promotes-21st-century-skills-in-schools-and-beyond .

Hirsh-Pasek, K., J.M. Zosh, R.M. Golinkoff, J.H. Gray, M.B. Robb, & J. Kaufman. 2015. “Putting Education in ‘Educational’ Apps: Lessons from the Science of Learning.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 16 (1): 3–34.

Isen, A.M., K.A. Daubman, & G.P. Nowicki. 1987. “Positive Affect Facilitates Creative Problem Solving.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52 (6): 1122–31.

Kearney, M.S., & P.B. Levine. (2016, Spring). Income, Inequality, Social Mobility, and the Decision to Drop Out of High School . Washington, DC: Brookings. www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/income-inequality-social-mobility-and-the-decision-to-drop-out-of-high-school .

King, A. 1993. “From Sage on the Stage to Guide on the Side.” College Teaching 41 (1): 30–35.

Lillard, A.S. 2013. “Playful Learning and Montessori Education.” American Journal of Play 5 (2): 157–86.

Meyer, M., J.M. Zosh, C. McLaren, M. Robb, R.M. Golinkoff, K. Hirsh-Pasek, & J. Radesky. 2021. “How Educational Are ‘Educational’ Apps for Young Children? App Store Content Analysis Using the Four Pillars of Learning Framework.” Journal of Children and Media . Published online February 23.

Miller, E., & J. Almon. 2009. Crisis in the Kindergarten: Why Children Need to Play in School . College Park, MD: Alliance for Childhood. https:// files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504839.pdf .

Moedt, K., & R.M. Holmes. 2020. “The Effects of Purposeful Play After Shared Storybook Readings on Kindergarten Children’s Reading Comprehension, Creativity, and Language Skills and Abilities.” Early Child Development and Care 190 (6): 839–54.

NAEYC. 2020. “Developmentally Appropriate Practice.” Position statement. Washington, DC: NAEYC. www.naeyc.org/resources/position-statements/dap .

Neuman, S.B., & K. Roskos. 1992. “Literacy Objects as Cultural Tools: Effects on Children’s Literacy Behaviors in Play.” Reading Research Quarterly 27 (3): 202–25.

Nicolopoulou, A., K.S. Cortina, H. Ilgaz, C.B. Cates, & A.B. de Sá. 2015. “Using a Narrative- and Play-Based Activity to Promote Low-Income Preschoolers’ Oral Language, Emergent Literacy, and Social Competence.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 31 (2): 147–62.

Pagani, L.S., C. Fitzpatrick, I. Archambault, & M. Janosz. 2010. “School Readiness and Later Achievement: A French Canadian Replication and Extension.” Developmental Psychology 46 (5): 984–94.

Pedulla, J.J., L.M. Abrams, G.F. Madaus, M.K. Russell, M.A. Ramos, & J. Miao. 2003. “Perceived Effect of State-Mandated Testing Programs on Teaching and Learning: Findings from a National Survey of Teachers” (ED481836). ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED481836 .

Ravitch, D. 2010. “Why Public Schools Need Democratic Governance.” Phi Delta Kappan 91 (6): 24–27.

Resnick, M. 2007. “All I Really Need to Know (About Creative Thinking) I Learned (by Studying How Children Learn) in Kindergarten.” In Proceedings of the 6th ACM SIGCHI Conference on Creativity & Cognition , 1–6. New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

Romano, E., L. Babchishin, L.S. Pagani, & D. Kohen. 2010. “School Readiness and Later Achievement: Replication and Extension Using a Nationwide Canadian Survey.” Developmental Psychology 46 (5): 995–1007.

Salinas-González, I., M.G. Arreguín-Anderson, & I. Alanís. 2018. “Supporting Language: Culturally Rich Dramatic Play.” Teaching Young Children 11 (2): 4–6.

Siegler, R.S., & G.B. Ramani. 2008. “Playing Linear Numerical Board Games Promotes Low-Income Children’s Numerical Development.” Developmental Science 11 (5): 655–61.

Siegler, R.S., & G.B. Ramani. 2009. “Playing Linear Number Board Games—but Not Circular Ones—Improves Low-Income Preschoolers’ Numerical Understanding. Journal of Educational Psychology 101 (3): 545–60.

Sim, Z., & F. Xu. 2015. “Toddlers Learn from Facilitated Play, Not Free Play.” In Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society , Berkeley, CA. https://cognitivesciencesociety.org/past-conferences .

Singer, D.G., & J.L. Singer. 1990. The House of Make-Believe: Children’s Play and the Developing Imagination . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Smith, K. 1993. “Becoming the ‘Guide on the Side.’” Educational Leadership 51 (2): 35–37.

Smith P.K., & A. Pellegrini. 2008. “Learning Through Play.” In Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online], eds. R.E. Tremblay, M. Boivin, & R.D. Peters, 1–6. Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development and Strategic Knowledge Cluster on Early Child Development. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/pdf/expert/play/according-experts/learning-through-play .

Souto-Manning, M. 2017. “Is Play a Privilege or a Right? And What’s Our Responsibility? On the Role of Play for Equity in Early Childhood Education.” Foreword. Early Child Development and Care 187 (5–6): 785–87. www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03004430.2016.1266588 .

Toub, T.S., B. Hassinger-Das, K.T. Nesbitt, H. Ilgaz, D.S. Weisberg, K. Hirsh-Pasek, R.M. Golinkoff, A. Nicolopoulou, & D.K. Dickinson. 2018. “The Language of Play: Developing Preschool Vocabulary Through Play Following Shared Book-Reading.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 45 (4): 1–17.

Weisberg, D.S., K. Hirsh-Pasek, & R.M. Golinkoff. 2013. “Guided Play: Where Curricular Goals Meet a Playful Pedagogy.” Mind, Brain, and Education 7 (2): 104–12.

Weisberg, D.S., K. Hirsh-Pasek, R.M. Golinkoff, & B.D. McCandliss. 2014. “Mise en place: Setting the Stage for Thought and Action.” Trends in Cognitive Science 18 (6): 276–78.

Zosh, J.M., B. Hassinger-Das, T.S. Toub, K. Hirsh-Pasek, & R. Golinkoff. 2016. “Playing with Mathematics: How Play Supports Learning and the Common Core State Standards.” Journal of Mathematics Education at Teachers College 7 (1): 45–49. https://doi.org/10.7916/jmetc.v7i1.787 .

Zosh, J.M., K. Hirsh-Pasek, E.J. Hopkins, H. Jensen, C. Liu, D. Neale, S.L. Solis, & D. Whitebread. 2018. “Accessing the Inaccessible: Redefining Play as a Spectrum.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01124 .

Jennifer M. Zosh, PhD, is professor of human development and family studies at Penn State Brandywine. Most recently, her work has focused on technology and its impact on children as well as playful learning as a powerful pedagogy. She publishes journal articles, book chapters, blogs, and white papers and focuses on the dissemination of developmental research.

Caroline Gaudreau, PhD, is a research professional at the TMW Center for Early Learning + Public Health at the University of Chicago. She received her PhD from the University of Delaware, where she studied how children learn to ask questions and interact with screen media. She is passionate about disseminating research and interventions to families across the country.

Roberta Michnick Golinkoff, PhD, conducts research on language development, the benefits of play, spatial learning, and the effects of media on children. A member of the National Academy of Education, she is a cofounder of Playful Learning Landscapes, Learning Science Exchange, and the Ultimate Playbook for Reimagining Education. Her last book, Becoming Brilliant: What Science Tells Us About Raising Successful Children (American Psychological Association, 2016), reached the New York Times bestseller list.

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, PhD, is the Lefkowitz Faculty Fellow in the Psychology and Neuroscience department at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She is also a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. Her research examines the development of early language and literacy, the role of play in learning, and learning and technology. [email protected]

Print this article

Play-Based Learning: Evidence-Based Research to Improve Children’s Learning Experiences in the Kindergarten Classroom

- Published: 31 October 2019

- Volume 48 , pages 127–133, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Meaghan Elizabeth Taylor 1 , 2 &

- Wanda Boyer 1

34k Accesses

53 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

With a heavy increase in academic expectations and standards to be learned in the early years, educators are facing the challenge of integrating important academic standards into developmentally appropriate learning experiences for children in kindergarten. To meet this challenge, there is a need to become familiar with the role of play in the classroom with an emphasis on developmentally appropriate practices such as play-based learning (PBL). PBL is child-centered and focuses on children’s academic, social, and emotional development, and their interests and abilities through engaging and developmentally appropriate learning experiences. This paper explores the definition of play-based learning (PBL), the theoretical frameworks and historical research that have shaped PBL, the different types of play, the social and academic benefits of PBL, and the ways in which educators can facilitate, support, assess, and employ technology to enhance PBL. The authors will conclude by reflecting on how teaching practices can be informed by evidence-based research to improve children’s learning experiences in the kindergarten classroom.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Play in Kindergarten: An Interview and Observational Study in Three Canadian Classrooms

Teaching play skills to children with disabilities: research-based interventions and practices.

Play-Based Learning Within the Early Years

Bodner, G. M. (1986). Constructivism: A theory of knowledge. Journal of Chemical Education, 63 (10), 873–878. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed063p873 .

Article Google Scholar

Bruce, T. (2012). The whole child. Play. In T. Bruce (Ed.), Early childhood practice: Froebel today (pp. 5–16). London, UK: SAGE Publication Ltd.

Chapter Google Scholar

Goldstein, L. S. (1997). Between a rock and a hard place in the primary grades: The challenge of providing developmentally appropriate early childhood education in an elementary school setting. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 12 (1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0885-2006(97)90039-9 .

Hoskins, K., & Smedley, S. (2019). Protecting and extending Froebelian principles in practice: Exploring the importance of learning through play. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 17 (2), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X18809114 .

MacKay, S. H. (2019). Teaching and learning: Starting with story workshop. Retrieved from https://opalschool.org/starting-with-story-workshop/

Miller, T. (2018). Developing numeracy skills using interactive technology in a play-based learning environment. International Journal of STEM Education, 5 (1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0135-2 .

Montessori, M. (1984). The absorbent mind . A laurel book New York, NY: Dell Publishing Company.

Google Scholar

Mukherji, P., & Albon, D. (2018). Research methods in early childhood. An introductory guide (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Nicol, J., & Taplin, J. T. (2018). Understanding the Steiner Waldorf Approach. Early years education in practice (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315456577 .

Book Google Scholar

Nolan, A., & Paatsch, L. (2017). (Re)affirming identities: Implementing a play-based approach to learning in the early years of schooling. International Journal of Early Years Education, 26 (1), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2017.1369397 .

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood (C. Gattegno & F. M. Hodgson, Trans.). New York, NY: Norton & Company Inc.

Pyle, A., & Alaca, B. (2018). Kindergarten children’s perspectives on play and learning. Early Child Development and Care, 188 (8), 1063–1075. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2016.1245190 .

Pyle, A., & Bigelow, A. (2014). Play in kindergarten: An interview and observational study in three Canadian classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43 (5), 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-014-0666-1 .

Pyle, A., & Danniels, E. (2017). A continuum of play-based learning: The role of the teacher in play-based pedagogy and the fear of hijacking play. Early Education and Development, 28 (3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1220771 .

Pyle, A., & DeLuca, C. (2017). Assessment in play-based kindergarten classrooms: An empirical study of teacher perspectives and practices. The Journal of Educational Research, 110 (5), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2015.1118005 .

Steiner, R. (1996). Lectures One -Eight by Rudolph Steiner Sunday April 15–Sunday April 22, 1923 (R. Everett & R. Everett Trans. & Ed.). The child’s changing consciousness: As the basis of pedagogical practice . Hudson, NY: Anthroposophic Press. Retrieved from https://steiner.presswarehouse.com/sites/steiner/research/archive/childs_changing_consciousness/childs_changing_consciousness.pdf

Vogt, F., Hauser, B., Stebler, R., Rechsteiner, K., & Urech, C. (2018). Learning through play—Pedagogy and learning outcomes in early childhood mathematics. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26 (4), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1487160 .

Vukelich, C. (1994). Effects of play interventions on young children’s reading of environmental print. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 9 (2), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0885-2006(94)90003-5 .

Vygotsky, L. S. (1966). The role of play in development. In the published work by Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky entitled: Problems of psychology. In M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in Society. The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (1979, pp. 92–104). Retrieved from http://ouleft.org/wp-content/uploads/Vygotsky-Mind-in-Society.pdf (Original Harvard University Press 1979)

Vygotsky, L. (1967). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. Soviet Psychology, 5 (3), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-040505036 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies, University of Victoria, 3800 Finnerty Road, Victoria, P.O. Box 1700, STN CSC, BC, V8W-2YC, Canada

Meaghan Elizabeth Taylor & Wanda Boyer

Sooke School District #62, Victoria, BC, Canada

Meaghan Elizabeth Taylor

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wanda Boyer .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Taylor, M.E., Boyer, W. Play-Based Learning: Evidence-Based Research to Improve Children’s Learning Experiences in the Kindergarten Classroom. Early Childhood Educ J 48 , 127–133 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00989-7

Download citation

Published : 31 October 2019

Issue Date : March 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00989-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Play-based Learning

- Play-based assessment

- Developmentally appropriate practice

- Kindergarten

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Commitment to Diversity & Justice

- Land Acknowledgement

- PZ Doctoral Fellows

- Our First 50 Years

- Art & Aesthetics

- Assessment, Evaluation & Documentation

- Civic Engagement

- Cognition, Thinking & Understanding

- Collaboration & Group Learning

- Digital Life & Learning

- Disciplinary & Interdisciplinary Studies

- Ethics at Work

- Global & Cultural Understanding

- Humanities & Liberal Arts

- Leadership & Organizational Learning

- Learning Environments

- Making & Design

- Science Learning

- Early Childhood

- Primary / Elementary School

- Secondary / High School

- Higher Education

- Adult & Lifelong Learning

- Organizational Learning

- Agency by Design

- Artful Thinking

- Arts as Civic Commons

- Causal Learning Projects

- Center for Digital Thriving

- Citizen-Learners: A 21st Century Curriculum and Professional Development Framework

- Creando Comunidades de Indagación (Creating Communities of Inquiry)

- Creating Communities of Innovation

- Cultivating Creative & Civic Capacities

- Cultures of Thinking

- EcoLEARN Projects

- Educating with Digital Dilemmas

- Envisioning Innovation in Education

- Global Children

- Growing Up to Shape Our Place in the World

- Higher Education in the 21st Century

- Humanities and the Liberal Arts Assessment (HULA)

- Idea Into Action

- Implementation of The Good Project Lesson Plans

- Inspiring Agents of Change

- Interdisciplinary & Global Studies

- Investigating Impacts of Educational Experiences

- JusticexDesign

- Leadership Education and Playful Pedagogy (LEaPP)

- Leading Learning that Matters

- Learning Innovations Laboratory

- Learning Outside-In

- Making Ethics Central to the College Experience

- Making Learning Visible

- Multiple Intelligences

- Navigating Workplace Changes

- Next Level Lab

- Out of Eden Learn

Pedagogy of Play

- Reimagining Digital Well-being

- Re-imagining Migration

- Signature Pedagogies in Global Education

- Talking With Artists Who Teach

- Teaching for Understanding

- The Good Project

- The Good Starts Project

- The Studio Thinking Project

- The World in DC

- Transformative Repair

- Visible Thinking

- Witness Tree: Ambassador for Life in a Changing Environment

- View All Projects

- At Home with PZ

- Thinking Routine Toolbox

- Zero In Newsletters

- View All Resources

- Professional Development

Search form

You are here

Cultivating school cultures that value and support learning through play

Play is central to how children learn—the way they form and explore friendships, the way they shape and test hypotheses, and the way they make sense of their world. Much is known about how play supports learning, yet little empirical research has explored what it might mean to put play at the center of formal schooling. In 2015, the Pedagogy of Play (PoP) research project began investigating the nature of playful learning in schools. Funded by the LEGO Foundation , the project focuses on three core questions: Why do educators need a pedagogy of play? What does playful learning look and feel like in classrooms and schools? How do educators set up the conditions where playful learning thrives?

The answers to these questions can be found in our book, A Pedagogy of Play: Supporting playful learning in classrooms and schools ! On our book resource page you can find free PDFs of the English and translated versions, links to purchase physical copies of the book via the Lulu website, and a link to access an audiobook/podcast companion.

We began our research with the International School of Billund (ISB) in Denmark, a school whose mission is designed around learning through play. Our research with ISB inspired a working set of playful learning principles, practices, and tools; pictures of practice (stories illustrating playful learning in action); and the beginnings of a pedagogy of play framework. We also developed a research methodology for examining and enhancing playful teaching and learning. Recognizing the cultural variations of learning and play, we expanded our research to include schools in South Africa, the United States, and Colombia. In each context, we sought to understand what playful learning looks and feels like.

On the tabs of this web page, you can find more details about our research, including some key ideas, resources for teachers and administrators to develop or enhance their playful learning practices, and resources for teacher educators who wish to support pre-service or in-service teachers in cultivating playful classrooms and schools. We also invite you to explore our blog popatplay.org , which offers team reflections and activities, stories of playful practice, and insights and experiences from practitioner and research colleagues who support learning through play.

A Pedagogy of Play: Supporting playful learning in classrooms and schools

Play is at the heart of childhood. Through play, children learn how to collaborate, how to negotiate rules and relationships, and how to imagine and create. They learn to find and solve problems, think flexibly and critically, and communicate effectively. This book, written by researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, draws on cross-cultural, empirical research to explore what it means to embrace play as a core part of learning in school. The authors address three questions: Why do educators need a pedagogy of play? What does playful learning in schools look and feel like? and How can educators promote playful learning? The book includes practices and strategies from the classroom to the staffroom, eight pictures of classroom practice from four countries, and 18 tools for teachers, school leaders, and professional development providers to support playful learning across content areas and age groups.

You can access a free PDF of the book on the right, along with translations available in Spanish, Simplified Chinese, and Traditional Chinese. You can also purchase a physical copy of the book in English, Simplified Chinese, and Traditional Chinese via the Lulu webstore:

- Simplified Chinese

- Traditional Chinese

For an audio version of the book, click on the podcast link in the resource menu or press play in the player below.

Click here to view all episodes

Toward a Pedagogy of Play

Playful provocations and playful mindsets: teacher learning and identity shifts through playful participatory research.

Play is a core resource for how children learn. Yet current efforts to bring playful learning into schools often neglect the role adults play in embracing and modeling playfulness. This paper presents findings from a collaboration between the International School of Billund, Denmark, and Project Zero, a research organization at Harvard Graduate School of Education. The study examined Playful Participatory Research (PPR), an emergent qualitative methodology that is both teacher research and a professional development (PD) approach. Drawing on interviews with 21 teachers across the school, we found that PPR positively affects: attitudes towards PD; teachers’ self-perception and identity; incorporation of play into teaching; and overall school culture. Implications suggest that school leaders who aspire to support learning through play in schools should design adult learning environments that mirror the playful learning environments they desire for children, by providing time, resources, and encouragement for playful teacher research and PD.

Toward an American Pedagogy of Play

With the goal of supporting educators in bringing more playful learning into their classrooms and schools, the Pedagogy of Play USA project conducted research in six schools in the Boston area in the Northeastern United States (U.S.). Considering the specific challenges and affordances of the local educational context, we examined what playful learning looks and feels like. Based on our research, we found that playful learning in the classrooms we studied is empowering, meaningful, and joyful. We begin this working paper with an example from a 2nd grade math lesson, one of three examples we share throughout the paper that illustrate what playful learning can look and feel like. Then, we explain the importance of understanding what playful learning involves in U.S. schools, describe the qualitative research methods employed in this work, and introduce the Indicators of Playful Learning: Six United States Schools, a model of what learning through play looks and feels like in the six schools in this study. We conclude with a discussion of the relevance of the indicators model to other U.S. schools. In Appendix A, we share examples of online playful learning in 1st and 5th math instruction.

Toward a South African Pedagogy of Play

What does playful learning look and feel like in South African schools? In this paper we put forward two hypotheses that address this question: a) learning through play in South African schools involves the interrelated experiences of ownership, curiosity, and enjoyment and b) for South African learners and educators, Ubuntu is a central part of playful learning. To explain these hypotheses, we introduce the South African “Indicators of Playful Learning”, a model of what playful learning looks and feels like in the nation’s classrooms. We explain the research methods—including analysis of classroom observations and interviews with learners, teachers, and principals--used in formulating these hypotheses, explore the connections between Ubuntu and playful learning, and share examples of playful learning from South African classrooms to illustrate our hypotheses. We discuss implications of our work, note the preliminary nature of our findings, and suggest next steps for research. Overall, the paper makes the case for a South African pedagogy of play and, by defining the phenomenon of learning through play, begins to explore what such an approach to teaching and learning might involve.

More than one way: An approach to teaching that supports playful learning

The evidence is clear: play supports learning (e.g., Bateson & Martin, 2013; Frost et al., 2012; Hale & Bocknek, 2015; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2009; Honeyford & Boyd, 2015; Plenty, 2015; Sullivan, 2011). Play can be joyful, iterative, socially interactive, meaningful and actively engaging (Zosh et al., 2017). These emotional, social, and cognitive features of play are why it can powerfully support learning. Play increases children’s motivation. It helps connect children’s knowledge, experiences, and interests. In play, children’s attention is focused. They persist through challenges and engage in deep learning, which supports them in consolidating skills and retaining what they have learned (Liu et al., 2017). Because play supports learning, it should have an important role in school. While play is often seen as an activity—soccer, chess, or a math game—it also involves a mindset, an outlook and approach towards activities. When participants experience activities at school as empowering, meaningful and joyful, these activities become playful learning. Mindsets can differ among participants; what is playful for one is not playful for all. Thus, playful mindsets are central to play’s role in learning at school. There are three important educational implications here. First, playful learning can be part of any subject because almost any activity—exploring prime numbers or writing a composition—can be playful. Second, promoting playful learning involves teachers activating and cultivating students’ playful mindsets. Third, to activate and cultivate playful mindsets for all students, educators need to be flexible, spontaneous and open to surprise. They need to be playful, taking a more than one way approach to their teaching. In this working paper, we explore this third implication: the teaching approach of more than one way and its importance in promoting playful learning. We begin with a brief explanation of the Pedagogy of Play (PoP) USA research on which this paper is based, and then turn to an example from a 4th grade classroom that illustrates what is play for one isn’t play for all. We then explain the teaching approach of more than one way. Two additional classroom examples—from early childhood and middle school—are shared to illustrate how more than way supports playful learning. Our analysis concludes with a discussion about how the idea of more than one way may fit into a pedagogy of play framework. A description of the research methods used in the PoP USA study is provided in an appendix.

Playful Participatory Research: An emerging methodology for developing a pedagogy of play

- What is the relationship between play, playfulness, and learning through play?

- How can a pedagogy of play be adapted to address different disciplines, age levels, and cultural contexts?

- What are the aspects of a school culture that promote learning through play and the experiences, rituals, tools, and spaces (e.g. celebrations, documentation, maker spaces) that support a culture of learning through play?

- How can school leaders empower teachers to increase playfulness and learning though play?

Since 2015, we have been investigating the relationship between play and school. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that play supports children’s social, cognitive, emotional, and physical development, and that there is a positive connection between enjoying learning and academic success. But integrating playful practices into school, or embracing play as a strategy for learning, has proven challenging. In part this is due to paradoxes that arise when play and school intersect:

- In play, children are in charge. At school, the adults typically set the agenda.

- Play can be chaotic, messy, and loud. Schools often need to be orderly and quiet.

- Play often involves taking risks. Schools aim to keep children safe.

Both statements in each bullet above are true, and both statements of each bullet should be honored. These paradoxes are the underpinning of why a pedagogy of play—a whole school approach to examining, discussing, and supporting playful learning and teaching—is critical.

Six Core Principles of Playful Learning

Based on literature reviews of learning and play, insights from educators and researchers around the globe, and practitioner action-research with playful teachers and school leaders in Denmark, South Africa, the U.S., and Colombia, our research team developed six core principles of playful learning:

- Play supports learning

- Playful learning in school requires play with a purpose

- Paradoxes between play and school add complexity to teaching and learning

- Playful learning is universal yet shaped by culture

- Playful mindsets are central to playful learning

- Supportive school cultures enable playful learning to thrive

These principles form the foundation of a pedagogy of play. You can read more about each principle in our book, linked on the Overview page.

Playful Learning Indicators

It is easier to talk about, plan for, and assess playful learning with colleagues who share an understanding of what playful learning means. Together with educators, we co-created working definitions of what playful learning looks and feels like in their own contexts. Through interviews with educators and students, observations, focus groups, study group discussions, and examining documentation of student learning, we developed site-specific, culturally relevant maps of playful learning. If you hover over the points marked on the map below, you can see these Indicators of Playful Learning for each site:

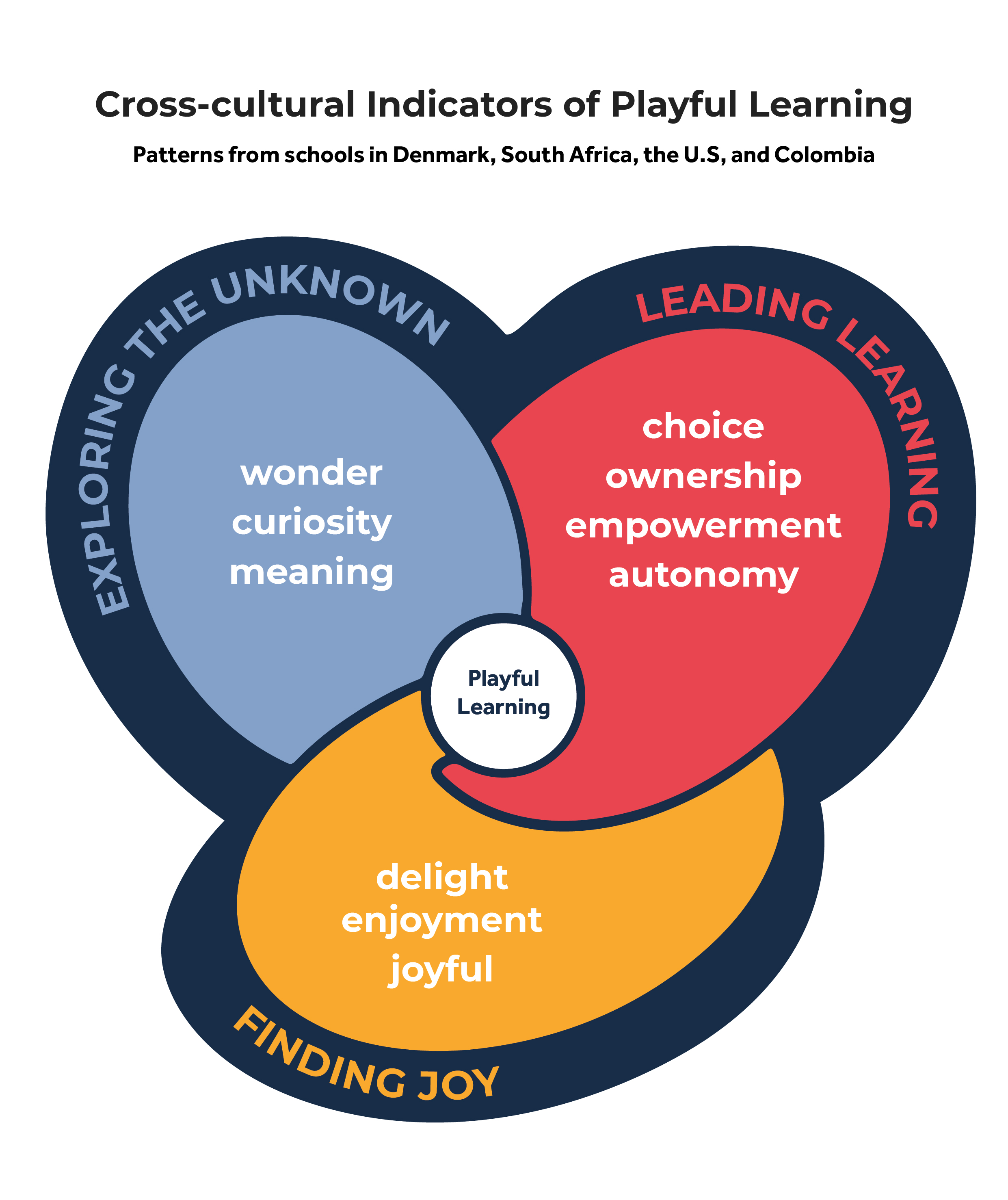

For each model, playful learning is represented at the intersection of the indicators; in other words, playful learning is likely to occur when all three indicators are present. The models are explored in depth in our working papers. Educators have used these indicators to develop a whole school approach to playful teaching and learning appropriate for their setting. Perhaps not surprisingly (after all, playful learning is universal), the models also share features across contexts. Looking across our four sites, we noticed patterns and developed a cross-cultural model of playful learning indicators.

The cross-cultural indicators provide a starting point for educators and school communities interested in exploring what playful learning looks and feels like, and how they might foster a pedagogy of play in their school. If you are interested in digging deeper or co-creating your own playful indicators, the Playful Learning Indicator Guide: A Weekly Handbook for Research Teams can be found on the For Educators tab on this website.

Playful Learning Practices & Strategies

How can educators set up the conditions where playful learning thrives? Based on extensive classroom observations and interviews across sites, consultations with key thought partners, a review of literature (including related pedagogies such as inquiry and project-based learning), and our own prior research and experiences in the classroom, we identified the following key practices and strategies that support playful learning and teaching across ages and contexts:

| Practices | Strategies |

|---|---|

Click here for an expanded description of these practices and strategies which, along with related tools, can be found on the For Educators tab and in our book.

Playful Participatory Research

To promote playful learning for children and older learners, it’s important for the adult learning community to also embody and engage in playful learning. We developed Playful Participatory Research (PPR) as a research and professional development approach for educators to reflect on their playful practice. PPR is a form of action research in which teachers collect data, analyze results, and use the knowledge to develop or deepen playful teaching and learning in their own schools. PPR provides opportunities for teachers to play with ideas, take risks, and explore new possibilities, and it provides school communities the opportunity to come together for conversations about a pedagogy of play. You can read more here about our collaboration with the International School of Billund and the impacts of PPR. If you want to learn more and try PPR in your school, you can find a link to the Playful Participatory Research Guide: An Interactive Workbook on the For Educators tab on this website.

One of our goals is to help educators—classroom teachers, teacher leaders, and administrators—incorporate more playful teaching and learning into daily practice. Here, we offer specific tools and resources that support a pedagogy of play.

The Educator Toolbox includes an overview of the playful learning practices and strategies, and eighteen related tools appropriate for all ages and contexts. We invite you to adapt the tools (with integrity!) to fit your needs.

| Planning for playful teaching and learning | |

| Empower learners to lead their own learning | |

| Build a culture of collaborative learning | |

| Promote experimentation and risk-taking | |

| Encourage imaginative thinking | |

| Welcome all emotions generated through play |

We also offer two guides and accompanying workbooks, designed for educators interested in conducting their own playful research (and research playfully!). The first is the Playful Participatory Research (PPR) Guide: An Interactive Workbook , developed by the Pedagogy of Play research team as a way to support educators’ playful learning. PPR is a type of practitioner inquiry or teacher research—research done by educators. It is a reflective and playful way for members of a learning community to explore learning through play together, through collecting and discussing data, analyzing it together, and applying what is learned. The PPR Guide provides an overview of the process, an interactive workbook to play with, and some additional resources to support the research.

The Playful Learning Indicator Guide: A Weekly Handbook for Research Teams helps educators co-create their own definition of playful learning. Modelled after the research process of Pedagogy of Play, the guide is helpful for any team of educators interested in better understanding what playful learning looks and feels like in their classrooms and school.

Welcome to the Pedagogy of Play (PoP) teacher education resource webpage. Here you will find materials for a 14-session course to introduce pre-service teacher candidates to playful learning.

These materials were created with the support, collaboration, and feedback from over 30 teacher educators from around the world. Feel free to adapt them as you see fit, using all or some of the course sessions. The material can also be adapted to use with in-service educators to promote their professional learning. Below, you will find:

- An instructor guide with detailed information about each course session

- A course syllabus that can be shared with teacher candidates

- PowerPoint slides for each course session

- Suggested Readings

- Resources, such as Activity Cards and Assignments that supplement information in the instructor guide, and a library of classroom videos from a range of age groups and geographies that are referenced in the syllabus to promote discussions of playful learning

Here are the course objectives shared with students in the syllabus:

Through this course, you will learn:

- WHY play is a core resource for learning

- WHAT play looks and feels like in different cultural contexts

- HOW educators can promote play and playful learning in schools, including practices and strategies for teaching and assessing learning through play

- To understand and address social justice and equity issues associated with learning through play with teacher research and equity-centered teaching

- To advocate for play as critical to children’s development and learning in schools

- To use Playful Participatory Research to reflect on and deepen learning through play

Students will work toward these goals by exploring and discussing theoretical and empirical literature on play, engaging in playful learning activities, and viewing examples of play from real classrooms.

Act 1 Why do we need a Pedagogy of Play?

- Through the Play Autobiography, students will begin to think about the relationship between play and learning through the lens of their personal experiences and their classmates

- Students will learn about the Principles of a Pedagogy of Play, using the hands-on Light and Shadow activity and video examples to unpack each principle

Session 1 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 1 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Through reading and class lecture/discussion, your students will learn about the neuroscience research that exists to understand how learning through play affects our brains

- Through discussion, your students will learn about prominent theories about play and playful learning and understand that theories are tools that can help educators plan for and interpret playful learning

- Through the Play Theory Gameshow, your students will practice using a range of play theories to interpret video examples of children’s play

Session 2 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 2 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Through reading and class lecture/discussion, students will explore how play can be a medium that supports children’s dispositions towards fairness and justice—how they must ensure playful learning experiences in school are open to all

Session 3 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 3 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Knowing that students may face skepticism on the part of families, administrators, and/or colleagues about playful learning, students will explore ways to advocate for play

- Introduce Playful Participatory Research through discussion of teacher research articles

- Use an activity to learn about documentation and help students identify a research question for the semester

Session 4 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 4 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

Act 2 What does learning through play look and feel like in different cultural contexts?

- Through readings, video, and discussion, students will learn that while there are general features, playful learning is also culturally determined

- In order to illustrate cultural variations of playful learning, students will be introduced to the indicators of playful learning from several contexts

Session 5 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 5 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- By sharing their Advocating for Play assignments, students will learn from and with each other about promoting playful learning

- Through readings, reflections on their play, and conversations with classmates, students will continue to explore how playful learning is influenced by culture

Session 6 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 6 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Students will learn about recommendations for technology and screentime use, try out a tech-based playful learning tool, and consider what playful learning with technology looks and feels like

- Through readings and discussion, students will consider what playful remote learning involves

Session 7 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 7 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Students will learn or revisit definitions of inclusion, dis/ability, and bilingualism

- Through reading, watching video examples, and discussion, students will build an understanding of what playful learning looks like in inclusive classrooms

- In inquiry groups, students will begin to share documentation with colleagues and use the Looking Playfully at Documentation protocol to guide their Playful Participatory Research

Session 8 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 8 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

Act 3 How can we promote a Pedagogy of Play?

- Revisit key concepts in the course so far through a playful activity (mad lib)

- Introduce students to the Pedagogy of Play practices and share examples of these from classrooms

- Make connections between the local learning standards in your context and the PoP practices. Engage students in planning learning experiences using these practices for inspiration

Session 9 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 9 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Today is all about learning how to scaffold and facilitate play, ensuring that learners explore and learn concepts in specific learning domains (e.g., literacy, mathematics, science) through play

Session 10 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 10 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Think about how to use the learning environment to foster playful learning

- Look at examples of indoor and outdoor playful learning environments

- Consider risky play

- Connect all of this to the PoP Practices

Session 11 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 11 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Take a deep look at one of the PoP Teaching Practices: Encourage Imaginative Thinking

- Learn a strategy called Storytelling and Story Acting, which was developed by Vivian Gussin Paley, and think about how to use this playful teaching approach with your learners

Session 12 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 12 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- To dig into some of the PoP practices and take more time to see examples of these in action

- To envision and practice using the PoP practices in current or future classrooms

Session 13 PowerPoint Slides (coming soon)

Session 13 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 13 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Wrap up and celebrate the Playful Participatory Research process by sharing research processes and findings with the group

Session 14 PowerPoint Slides (PPT)

Session 14 PowerPoint Slides (PDF)

- Activities and Assignment Plans

- Video Library

- Meet the Collaborators

- PoP Resources & Links

- Resources from Collaborators

- PoP Teacher Education F.A.Q.

Project Info

Mara Krechevsky

Yvonne Liu-Constant

Jennifer Oxman Ryan

Daniel Wilson

Megina Baker

Katie Ertel

Ben Mardell

Lynneth Solis

Gigi A. Visbal

Related resources.

- View all Pedagogy of Play resources -

- Privacy Policy

- Harvard Graduate School of Education

- Harvard University

- Digital Accessibility Policy

Copyright 2022 President and Fellows of Harvard College | Harvard Graduate School of Education

Subscribe to Our Mailing List

Email Address

By submitting this form, you are granting: Project Zero, 13 Appian Way, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02138, United States, http://www.pz.gse.harvard.edu permission to email you. You may unsubscribe via the link found at the bottom of every email. (See our Email Privacy Policy for details.) Emails are serviced by Constant Contact.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Playful learning describes a learning context in which children learn content while playing freely (free play or self-directed play), with teacher guidance (guided play), or in a structured game.

Play-based learning is developmentally appropriate for young children. As we think back to the scene of seventeen-three-year old children engaged and busy in the classroom, we also observe children who are content in exploring and learning through play in their early childhood classroom.

This paper explores the definition of play-based learning (PBL), the theoretical frameworks and historical research that have shaped PBL, the different types of play, the social and academic benefits of PBL, and the ways in which educators can facilitate, support, assess, and employ technology to enhance PBL.

A key element to consider is ‘learning through play’, or ‘playful learning’, which is central to quality early childhood pedagogy and education.3 This brief will help pre-primary stakeholders advocate for making play-based or playful learning a central aspect of expanding and strengthening the pre-primary sub-sector.

Play-based learning is often illustrated as a method of teaching that incorporates physical activity in the learning process. This aims to influence the children to learn in a fun way.

The aim of our study was to synthesize international research on ECE practitioners’ views on PBL. Based on a meta-synthesis of 62 studies from 24 national contexts, we show that they have differing views on the degree of conceptual compatibility between play and learning.

Play-based learning is a vital aspect of early childhood education that provides children with a meaningful and enjoyable way to learn and explore the world around them.

The play-based pedagogy is an approach that can be dated back to the late 19th century. Froebel was the first to figure out the educational benefits of play in a formal way in the 1890s (Eberle 2014; Ogunyemi & Ragpot 2016).

It’s possible to play with a purpose. There is a difference between free play and playful learning. While both are important, a pedagogy of play is grounded in playing toward certain learning goals, designing activities that fit in and leverage curricular content and goals.

Play is central to how children learn—the way they form and explore friendships, the way they shape and test hypotheses, and the way they make sense of their world. Much is known about how play supports learning, yet little empirical research has explored what it might mean to put play at the center of formal schooling.