- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

- Submit your manuscript

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Relationship Between the Problem-Solving Skills and Empathy Skills of Operating Room Nurses

AY, Fatma 1* ; POLAT, Şehrinaz; KASHIMI, Tennur

1 PhD, RN, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Midwifery, Istanbul University-Cerrahpaşa, Turkey

2 PhD, RN, Directorate of Nursing Services, Hospital of Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University, Turkey

3 MS, RN, Director, Operating Room, Hospital of Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University, Turkey.

Accepted for publication: January 21, 2019

*Address correspondence to: Fatma AY, No.25, Dr. Tevfik Saglam Street, Dr. Zuhuratbaba District, Bakirkoy, Istanbul 34147, Turkey. Tel: +90 212 4141500 ext. 40140; Fax: +90 212 4141515; E-mail: [email protected]

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Cite this article as: Ay, F., Polat, Ş., & Kashimi, T. (2019). Relationship between the problem-solving skills and empathy skills of operating room nurses. The Journal of Nursing Research , 28 (2), e75. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000357

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CCBY) , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background

The use of empathy in problem solving and communication is a focus of nursing practice and is of great significance in raising the quality of patient care.

Purpose

The purposes of this study are to investigate the relationship between problem solving and empathy among operating room nurses and to explore the factors that relate to these two competencies.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional, descriptive study. Study data were gathered using a personal information form, the Interpersonal Problem Solving Inventory, and the Basic Empathy Scale ( N = 80). Descriptive and comparative statistics were employed to evaluate the study data.

Results

Age, marital status, and career length were not found to affect the subscale scores of cognitive empathy ( p > .05). A negative correlation was found between the subscale scores for “diffidence” and “cognitive empathy.” Moreover, the emotional empathy scores of the graduate nurses were higher than those of the master's/doctorate degree nurses to a degree that approached significance ( p = .078). Furthermore, emotional empathy levels were found to decrease as the scores for insistent/persistent approach, lack of self-confidence, and educational level increased ( p < .05). The descriptive characteristics of the participating nurses were found not to affect their problem-solving skills.

Conclusions/Implications for Practice

Problem solving is a focus of nursing practice and of great importance for raising the quality of patient care. Constructive problem-solving skills affect cognitive empathy skills. Educational level and career length were found to relate negatively and level of self-confidence was found to relate positively with level of cognitive empathy. Finally, lower empathy scores were associated with difficult working conditions in operating rooms, intense stress, and high levels of potential stress-driven conflicts between workers in work settings.

Introduction

Healthcare institutions are where individuals seek remedies to their health problems. These institutions face problems, which relate to both employees and care recipients. These problems may occur spontaneously and require immediate solution. Moreover, these problems require that the preferred remedies be adapted to address the unique nature of both organizational circumstances and individual requirements. Therefore, it is important that nurses, who are a major component of the healthcare system, have problem-solving skills.

Operating rooms are complex, high-risk environments with intense levels of stress that require rapid judgment making and fast implementation of appropriate decisions to increase patients' chances of survival ( Kanan, 2011 ; Jeon, Lakanmaa, Meretoja, & Leino-Kilpi, 2017 ). Furthermore, aseptic principles may never be compromised, and a high level of coordination and cooperation among team members should be maintained in these areas ( Kanan, 2011 ; Sandelin & Gustafsson, 2015 ). The members of a surgical team may vary in the operating room ( Sandelin & Gustafsson, 2015 ; Sonoda, Onozuka, & Hagihara, 2018 ). Under these difficult conditions, time management and workload are important stress factors for nurses ( Happell et al., 2013 ; Suresh, Matthews, & Coyne, 2013 ). At the same time, operating room nurses are legally responsible for the nature and quality of the healthcare service received by patients before, during, and after their surgical intervention ( Kanan, 2011 ). The American Nurses Association defines a nurse as “the healthcare professional establishing, coordinating and administering the care while applying the nursing process in an aim to meet the identified physiological, psychological, sociocultural and spiritual needs of patients who are potentially at the risk of jeopardized protective reflexes or self-care ability because of surgery or invasive intervention” ( Association of periOperative Registered Nurses, 2015 ).

Problem solving is the most critical aspect of the nursing practice. The fact that nursing requires mental and abstract skills, such as identifying individual needs and finding appropriate remedies, was first stated in 1960s. In 1960s, the nursing theorists Abdellah, Orem, and Levin emphasized the mental aspect of nursing. They argued that the most critical requirement of nurses in the clinical field is the ability to decide on and plan the right action and that nursing care should be founded on a sound knowledge base ( Taşci, 2005 ).

The World Health Organization has stated that “taking measures and applying a problem-solving approach to provide appropriate care is one of the compulsory competencies of nurses” ( Taşci, 2005 ). Thus, enhancing the problem-solving skills of nurses is of great importance in raising the quality of patient care ( Taylor, 2000 ; Yu & Kirk, 2008 ). On the other hand, Bagnal (1981) argued that people with problem-solving skills need to be equipped with personal traits including innovation, clear manifestation of preferences and decisions, having a sense of responsibility, flexible thinking, courage and adventurousness, ability to show distinct ideas, self-confidence, a broad area of interest, acting rationally and objectively, creativity, productivity, and critical perspective (as cited in Çam & Tümkaya, 2008 ).

To provide the best surgical care to a patient, team members must work together effectively ( Sonoda et al., 2018 ). One of the most important factors affecting the quality of healthcare service delivery is effective communication between healthcare professionals and healthcare recipients, with empathy forming the basis for effective communication.

Because of the intrinsic nature of the nursing profession, nurses should have empathy skills. Thus, empathy is the essence of the nursing profession ( Fields et al., 2004 ; Vioulac, Aubree, Massy, & Untas, 2016 ). A review of resources in the literature on problem solving reveals that gathering problem-related data is the first major step toward determining the root causes of a problem. In this respect, empathy is an important skill that helps properly identify a problem. On the basis of the definition of empathy, sensing another person's feelings and thoughts and placing oneself in his or her position or feeling from within his or her frame of reference should work to improve one's problem-solving skills, particularly those skills related to social problem solving ( Taşci, 2005 ; Topçu, Baker, & Aydin, 2010 ; Vioulac et al., 2016 ). It is possible to explain empathic content emotionally as well as cognitively. Emotional empathy (EE) means feeling the emotions of another person and providing the most appropriate response based on his or her emotional state. This is very important in patient–nurse communications. Cognitive empathy (CE) is the ability to recognize the feelings of another without experiencing those feelings yourself ( de Kemp, Overbeek, de Wied, Engels, & Scholte, 2007 ).

Gender, age, level of education, marital status, years of work, duration working at current institution, and problem-solving situations have been shown in the literature not to affect the problem-solving or empathy skills of nurses ( Abaan & Altintoprak, 2005 ; Kelleci & Gölbaşi, 2004 ; Yu & Kirk, 2008 ). Empathy is especially critical to the quality of nursing care and is an essential component of any form of caring relationship. The findings in the literature regarding empathy among nurses are inconsistent ( Yu & Kirk, 2008 ), and no findings in the literature address the relationship between problem-solving skills and empathy skills in operating room nurses.

Today, the healthcare system demands that nurses use their professional knowledge to handle patient problems and needs in flexible and creative ways. Problem solving is a primary focus of the nursing practice and is of great importance to raising the quality of patient care ( Kelleci & Gölbaşi, 2004 ; Yu & Kirk, 2008 ). Enhancing the problem-solving and empathy skills of nurses may be expected to facilitate their identification of the sources of problems encountered during the delivery of healthcare services and their resolution of these problems.

The purposes of this study are to investigate the relationship between problem solving and empathy in operating room nurses and to explore the factors related to these two competencies.

Study Model and Hypotheses

This study is a cross-sectional and descriptive study. The three hypotheses regarding the relationships between the independent variables are as follows:

- H1: Sociodemographic characteristics affect problem-solving skills.

- H2: Sociodemographic characteristics affect level of empathy.

- H3: Problem-solving skills are positively and significantly correlated with empathy.

Study Population and Sample

The study was conducted during the period of May–June 2015 at three hospitals affiliated with Istanbul University. The study population consisted of 121 nurses who were currently working in the operating rooms of these hospitals. The study sample consisted of the 80 nurses who volunteered to participate and answered all of the questions on the inventory.

Data Collection Tool

Study data were gathered using a personal information form, the Interpersonal Problem Solving Inventory (IPSI), and the Basic Empathy Scale.

Personal information form

This questionnaire, created by the researchers, is composed of 10 questions on the age, gender, educational background, organization and department, position, and organizational and professional functions of the respondent.

Interpersonal problem solving inventory

The IPSI, developed and validated by Çam and Tümkaya (2008) , was used in this study. The Cronbach's α internal consistency coefficients of the IPSI subscales were previously evaluated at between .67 and .91. The IPSI includes 50 items, all of which are scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 = strictly inappropriate and 5 = fully appropriate . The lack of self-confidence (LSC) subscale assesses lack of confidence in problem solving. The constructive problem solving (CPS) subscale assesses emotions, thoughts, and behaviors that contribute to the effective and constructive solution of interpersonal problems. The negative approach to the problem subscale assesses intensely the negative emotions and thoughts such as helplessness, pessimism, and disappointment that are experienced when an interpersonal problem is encountered. The abstaining from responsibility subscale assesses failure to take responsibility for solving the problem. The persistent approach (PA) subscale assesses self-assertive/persistent thoughts and behaviors in solving problems encountered in interpersonal relationships. A high score on a subscale indicates a high interpersonal-problem-solving capability for that subscale category ( Çam & Tümkaya, 2008 ). A high score on the negative approach to the problem subscale indicates a higher likelihood of experiencing intense negative feelings and thoughts such as helplessness, pessimism, and sadness when encountering a problem. A high score on CPS indicates that the respondent will show more of the emotions, thoughts, and behaviors that contribute to the problem in an effective and constructive way. A low level of self-confidence indicates that the respondent will exhibit low self-confidence toward effectively resolving a problem. A high score on the abstaining from responsibility subscale indicates a high inclination to assume responsibility to resolve a problem ( Table 1 ). The high level of insistent approach indicates that the participant is more willing to solve problems ( Çam & Tümkaya, 2008 ). In this study, the Cronbach's α reliability coefficients were .901, .899, .763, .679, and .810, respectively.

Basic empathy skill scale

The Basic Empathy Skill Scale was developed by Jolliffe and Farrington (2006) and validated by Topçu et al. (2010) in Turkish. It is a 5-Likert scale (1 = s trictly disagree and 5 = strictly agree ) consisting of 20 items, of which nine measure CE and 11 measure EE. The Cronbach's α coefficients that were calculated for the reliability study range between .76 and .80. The lowest possible scores are 9 and 45 and the highest possible scores are 11 and 55 for the CE and EE subscales, respectively. A high score on the CE subscale indicates that the CE level is high, and a high score on the EE subscale indicates that the EE level is high ( Topçu et al., 2010 ). The two subscales of the Basic Empathy Skill Scale have been found to be highly reliable. The Cronbach's α reliability coefficients in this study were .782 for the CE subscale and .649 for the EE subscale.

Data Collection

The study was conducted between May and June 2015 at three hospitals affiliated with Istanbul University. The researcher explained the study to those nurses who agreed to participate. The questionnaire form was distributed to the participants, the purpose of the investigation was clarified, and permission to use participant data was obtained. The participants completed the questionnaire on their own, and the completed questionnaires were collected afterward. The time required to complete the questionnaire was 15–20 minutes in total.

Evaluation of Data

Number Cruncher Statistical System 2007 (Kaysville, UT, USA) software was used to perform statistical analysis. To compare the quantitative data, in addition to using descriptive statistical methods (mean, standard deviation, median, frequency, ratio, minimum, maximum), the Student t test was used to compare the parameters with the regular distribution in the two groups and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the parameters without normal distribution in the two groups. In addition, a one-way analysis of variance test was used to compare three or more groups with normal distribution, and a Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare three or more groups without normal distribution. Pearson's correlation analysis and Spearman's correlation analysis were used to evaluate the relationships among the parameters. Finally, linear regression analysis was employed to evaluate multivariate data. Significance was determined by a p value of < .05.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical conformity approval was obtained from the Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Board at Istanbul Medipol University (108400987-165, issued on March 30, 2015). Written consent was obtained from the administrations of the participating hospitals. Furthermore, the informed consent of nurses who volunteered to participate was obtained. Permission to use the abovementioned scales that were used in this study as data collection tools was obtained via e-mail from their original authors.

Eighty nurses (97.5% female, n = 78; 2.5% male, n = 2) were enrolled as participants. The age of participants ranged between 24 and 64 (mean = 37.56 ± 8.12) years, mean years of professional nursing experience was 15.84 ± 8.30, and mean years working in the current hospital was 13.19 ± 8.23. Other descriptive characteristics for the participants are provided in Table 2 .

A comparison of scale subdimension scores revealed a negative and statistically significant correlation at a level of 22.3%. Statistical significance was reached only between the LSC subscale and the CE subscale ( r = −.223, p = .047; Table 3 ). Thus, a higher LSC score was associated with a lower CE score.

Comparisons between participants' descriptive characteristics and subdimension scores on the problem-solving skill scale revealed no significant differences. Thus, demographic characteristics such as age, educational background, and career length were found to have no influence on problem-solving skills ( p > .05; Table 4 ).

Age, marital status, and professional career length were not found to affect the CE and EE subscale scores, with no statistically significant correlations found between the two subscales ( p > .05; Table 4 ). However, the EE scores of undergraduate nurses were found to be higher than those of postgraduate nurses, at a level that approached statistical significance ( p = .078). In addition, the average CE scores of nurses who had worked for 1–10 and 11–20 years were higher than those of nurses who had worked for 21 years or more, at a level that approached statistical significance ( p = .066).

A statistically significant difference was found between mean years working in the current hospital and educational background, respectively, and CE scores ( p = .027 and p = .013; Table 4 ). On the basis of paired comparison analysis, the CE scores of participants with 1–10 years of working experience at their current hospital were higher than those with ≥ 21 years of working experience at their current hospital ( p = .027). Also on the basis of paired comparison analysis, the CE score of participants educated to the undergraduate level was found to be higher at a statistically significant level than those educated to the master's/doctorate degree level ( p = .013).

The comparison of problem-solving skill scores by descriptive characteristics revealed no statistically significant difference between subscale scores and the variables of age, marital status, length of professional and organizational career, or educational background ( p > .05). Thus, the descriptive characteristics of the participants did not affect their problem-solving skills.

Regression Analysis of Risk Factors Affecting Cognitive and Empathy Skills

Variables found after univariate analysis to have significance levels of p < .01 were subsequently modeled and evaluated. A regression analysis was conducted to determine the effect on CE skills of educational level, duration of institutional work, CPS level, and self-insecurity level. The explanatory power of this model was 29.9% ( R 2 = .299), and the model was significant ( p < .001). As a result of the analysis, CPS ( p = .006), educational status of graduate ( p < .001), and working for the current hospital for a period of more than 20 years ( p = .004) were found to have a significant and positive influence on the CE score.

A 1-unit increase in the CPS score was found to increase CE skills by 0.139 points (β = 0.139, 95% CI [0.041, 0.237], p < .01). For education, graduate education was found to decrease the CE score by 4.520 points (β = −4.520, 95% CI [−6.986, −2.054], p < .001). For duration working for the current hospital, working for the same institution for a period exceeding 20 years was found to decrease the CE score by 3.429 points (β = −3.429, 95% CI [−5.756, −1.102], p < .05). In addition, a 1-unit increase in the LSC score was found to decrease the CE score by 0.114 points, which did not achieve statistical significance (β = 0.114, 95% CI [−0.325, 0.096], p > .05).

Regression analysis was used to evaluate the effects of education, PA, and LSC on the risk factors affecting EE. As a result of this evaluation, the explanatory power of the model was determined as 15.3% ( R 2 = .153), which was significant despite the low level ( F = 3.388, p = .001). The effects of PA ( p = .021) and educational status ( p = .015) on the EE score were shown through analysis to be statistically significant ( Table 5 ). A 1-unit increase in PA score was found to increase the EE score by 0.323 points (β = 0.323, 95% CI [0.049, 0.596], p < .05). For education, having a graduate education was found to decrease the EE score by 3.989 points (β = −3.989, 95% CI [−7.193, −0.786], p < .05). Moreover, the LSC score was found to be 0.119 points lower than the EE score. However, this result was not statistically significant (β = −0.193, 95% CI [−0.467, 0.080], p > .05). Dummy variables were used in the regression analysis of sociodemographic characteristics (educational status and years working for the current hospital).

This study found that age, marital status, educational background, years of professional working experience, and years working for the current hospital did not affect the problem-solving skills of the participants. In the literature, the findings of several studies indicate that characteristics such as age, educational background, department of service, and career length do not affect the problem-solving skills of nurses ( Abaan & Altintoprak, 2005 ; Kelleci & Gölbaşi, 2004 ; Yu & Kirk, 2008 ), whereas other studies indicate that these variables do affect these skills ( Ançel, 2006 ; Watt-Watson, Garfinkel, Gallop, Stevens, & Streiner, 2000 ; Yu & Kirk, 2008 ). However, beyond these characteristics, some studies have reported a positive correlation between the problem-solving skills of nurses and their educational level, with this correlation mediated by the physical conditions of the workplace, good relationships with colleagues, and educational background ( Yildiz & Güven, 2009 ). These findings suggest that factors affecting the empathy and problem-solving skills of nurses working in operating rooms differ from known and expected factors.

Operating room nurses deliver dynamic nursing care that requires attention and close observation because of the fast turnover of patients. In addition to the problem-solving skills that they use during the patient care process, these nurses must use or operate a myriad of lifesaving technological devices and equipment ( AbuAlRub, 2004 ; Özgür, Yildirim, & Aktaş, 2008 ). The circumstances in which nurses employ their problem-solving skills are generally near-death critical conditions and emergencies. Furthermore, operating rooms are more isolated than other areas of the hospital, which affects nurses who work in operating rooms and intensive care units ( AbuAlRub, 2004 ; Özgür et al., 2008 ).

Communication is a critical factor that affects the delivery of healthcare services. Communication does not only take place between a service recipient and a provider. To establish a teamwork philosophy between employees, it is essential to build effective communication ( Sandelin & Gustafsson, 2015 ). Empathic communication helps enhance the problem-solving skills of nurses as they work to learn about individual experiences ( Kumcağiz, Yilmaz, Çelik, & Avci, 2011 ). Studies in the literature have found that nurses who are satisfied with their relationships with colleagues, physicians, and supervisors have a high level of problem-solving skills ( Abaan & Altintoprak, 2005 ; Kumcağiz et al., 2011 ) and that higher problem-solving skills are associated with a higher level of individual achievement ( Abaan & Altintoprak, 2005 ; Chan, 2001 ). Another finding of this study is that CPS increases the cognitive emphatic level. This may be attributed to constructive problem-solving skills increasing CE, as these skills are associated with feelings, thoughts, and behaviors that contribute to problem resolution.

A review of the literature on empathy and communication skills revealed, as expected, that these skills increased with level of education ( Kumcağiz et al., 2011 ; Vioulac et al., 2016 ). However, a number of studies have reported no significant correlation between age, marital status, and professional working experience and empathy skills or communication abilities in nurses ( Kumcağiz et al., 2011 ; Yu & Kirk, 2008 ).

EE is assumed to be a more intuitive reaction to emotions. Factors that affect EE are nurses working with small patient groups, frequent contact with patient groups, and long periods spent accompanying or being in close contact with patient groups ( Vioulac et al., 2016 ). Studies in the literature have reported no correlation between the empathy skills of nurses and demographic characteristics ( Vioulac et al., 2016 ). This study supports this finding, with the empathy skills of operating room nurses found to be close to the peak value of the scale.

Studies in the literature reveal a positive correlation between empathy and career length ( Watt-Watson et al., 2000 ; Yu & Kirk, 2008 ) as well as a correlation between increased professional experience and lower empathy ( Yu & Kirk, 2008 ). This study found an association between longer periods working for the same hospital and higher levels of education with lower empathy scores. This may be attributed to the difficult working conditions in operating rooms, intense stress, and high level of potential stress-driven conflicts between employees in work settings.

Stress is a major factor that affects the empathy skills and relationship-building abilities of nurses ( Vioulac et al., 2016 ). Nurses are exposed to a wide variety of stressors such as quality of the service, duration of shifts, workload, time pressures, and limited decision-making authority ( Patrick & Lavery, 2007 ; Shimizutani et al., 2008 ; Vioulac et al., 2016 ). In particular, environments evoking a sense of death (e.g., operating rooms) is another factor known to elevate perceived stress ( Ashker, Penprase, & Salman, 2012 ). High stress may lead to negative consequences such as reduced problem-solving abilities ( Zhao, Lei, He, Gu, & Li, 2015 ). Both having a long nursing career and working in stressful environments such as operating rooms may negatively affect empathy and problem-solving skills. However, this study revealed that working for a long period at the current hospital had no influence on problem-solving skills. The low reliability of the scales means that the variance may be high in other samples that are drawn from the same main sample, with the resultant data thus not reflecting the truth.

Low reliability coefficients reduce the significance and value of the results obtained by increasing the standard error of the data ( Şencan, 2005 ). The Cronbach's α of the EE scale used in the study was between .60 and .80 and is highly trustworthy. However, the Cronbach's α value is close to .60 (i.e., .649). This result may elicit suspicion in regression analysis estimates that are done to determine the variables that affect EE. In the correlation analysis, a statistically significant weak correlation was found only between the LSC subdimension and CE. However, the fact that the subscales of empathy and problem-solving skills are significantly related to the regression models may also be related to the reliability levels of the scales.

According to the results of the regression analysis, all of the variables remaining in Model A affected level of low for the CE ( R 2 = .299). Having constructive problem-solving skills ( p = .006), having a high level of education ( p < .001), and working for the current hospital for over 20 years ( p = .004) were found to be significantly related to CE.

Other variables were found to have no significant effect. According to the results of the regression analysis, all of the remaining variables in Model B accounted for a relatively low portion of the EE ( R 2 = .153). When the t test results for the significance of the regression coefficients were examined, it was determined that PA ( p = .021) and educational status ( p = .015) were significant predictors of EE. Other variables had no significant effect ( Table 5 ). The increase in the level of education of nurses may have increased their cognitive and emotional development. Thus, working in the same hospital for over 20 years was found to increase the levels of CE and EE. This result may be because of greater professional experience and regular experience handling numerous, different problems. In addition, the low explanatory power of the models may also be because of the fact that many other arguments that may affect empathy were not modeled. When constant values are fixed and the value of the independent variables entering the regression formula is zero, constant value is the estimated value of the dependent variable. According to findings of this study, sociodemographic characteristics and problem-solving abilities did not affect empathy level, although the CE value was 31.707 and the EE value was 37.024. Repeating this research in larger and different nurse groups may be useful to verify these research results.

Conclusions

The following results were derived from this study: First, constructive problem-solving skills affect CE skills. EE is adversely affected by the PA and LSC. Second, no correlation was found between the demographic characteristics of nurses and their problem-solving skills. Third, as level of education increases, cognitive and emotional levels of empathy decrease.

Duration of time spent working at one's current healthcare institution and educational level were both found to correlate negatively with the CE score. The higher the educational level and PA and the lower the self-confidence of the participants, the lower their EE levels. Finally, higher constructive problem-solving scores were associated with higher CE skills.

Limitations

The major limitation of the study is that it was conducted in the affiliated hospitals of one healthcare organization. The study data were obtained from operating room nurses who currently worked in these hospitals and who volunteered to participate. The conditions of nurses who did not participate in the study cannot be ascertained. A second important limitation is that the data reflect the subjective perceptions and statements of the participants. A third important limitation is that participant characteristics such as trust in management, trust in the institution, burnout, and communication skills were not assessed. For this reason, the effects of these variables on problem-solving and empathy skills remain unknown.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: SP

Data collection: TK

Data analysis and interpretation: FA, SP

Drafting of the article: FA

Critical revision of the article: FA

- Cited Here |

- Google Scholar

operating room; critical thinking; surgery; cognitive; emotional

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Effectiveness of a patient safety incident disclosure education program: a..., the relationship between critical thinking skills and learning styles and....

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Relationship Between the Problem-Solving Skills and Empathy Skills of Operating Room Nurses

Affiliations.

- 1 PhD, RN, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Midwifery, Istanbul University-Cerrahpaşa, Turkey.

- 2 PhD, RN, Directorate of Nursing Services, Hospital of Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University, Turkey.

- 3 MS, RN, Director, Operating Room, Hospital of Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University, Turkey.

- PMID: 31856024

- DOI: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000357

Background: The use of empathy in problem solving and communication is a focus of nursing practice and is of great significance in raising the quality of patient care.

Purpose: The purposes of this study are to investigate the relationship between problem solving and empathy among operating room nurses and to explore the factors that relate to these two competencies.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional, descriptive study. Study data were gathered using a personal information form, the Interpersonal Problem Solving Inventory, and the Basic Empathy Scale (N = 80). Descriptive and comparative statistics were employed to evaluate the study data.

Results: Age, marital status, and career length were not found to affect the subscale scores of cognitive empathy (p > .05). A negative correlation was found between the subscale scores for "diffidence" and "cognitive empathy." Moreover, the emotional empathy scores of the graduate nurses were higher than those of the master's/doctorate degree nurses to a degree that approached significance (p = .078). Furthermore, emotional empathy levels were found to decrease as the scores for insistent/persistent approach, lack of self-confidence, and educational level increased (p < .05). The descriptive characteristics of the participating nurses were found not to affect their problem-solving skills.

Conclusions/implications for practice: Problem solving is a focus of nursing practice and of great importance for raising the quality of patient care. Constructive problem-solving skills affect cognitive empathy skills. Educational level and career length were found to relate negatively and level of self-confidence was found to relate positively with level of cognitive empathy. Finally, lower empathy scores were associated with difficult working conditions in operating rooms, intense stress, and high levels of potential stress-driven conflicts between workers in work settings.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Gender differences in empathy, emotional intelligence and problem-solving ability among nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Deng X, Chen S, Li X, Tan C, Li W, Zhong C, Mei R, Ye M. Deng X, et al. Nurse Educ Today. 2023 Jan;120:105649. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105649. Epub 2022 Nov 17. Nurse Educ Today. 2023. PMID: 36435156

- Investigating the psychological resilience, self-confidence and problem-solving skills of midwife candidates. Ertekin Pinar S, Yildirim G, Sayin N. Ertekin Pinar S, et al. Nurse Educ Today. 2018 May;64:144-149. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.02.014. Epub 2018 Feb 17. Nurse Educ Today. 2018. PMID: 29482050

- Problem-solving skills of University nursing students and factors affecting them: A Cross-sectional study. Yildirim JG, Calt AC, Ardahan M. Yildirim JG, et al. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019 Nov;69(11):1717-1720. doi: 10.5455/JPMA.2635.. J Pak Med Assoc. 2019. PMID: 31740886

- Do higher dispositions for empathy predispose males toward careers in nursing? A descriptive correlational design. Penprase B, Oakley B, Ternes R, Driscoll D. Penprase B, et al. Nurs Forum. 2015 Jan-Mar;50(1):1-8. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12058. Epub 2014 Jan 3. Nurs Forum. 2015. PMID: 24383747 Review.

- Does vicarious traumatisation affect oncology nurses? A literature review. Sinclair HA, Hamill C. Sinclair HA, et al. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007 Sep;11(4):348-56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2007.02.007. Epub 2007 May 7. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2007. PMID: 17482879 Review.

- Factors influencing the complex problem-solving skills in reflective learning: results from partial least square structural equation modeling and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. Wang Y, Xu ZL, Lou JY, Chen KD. Wang Y, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2023 May 25;23(1):382. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04326-w. BMC Med Educ. 2023. PMID: 37231484 Free PMC article.

- Clinical learning opportunity in public academic hospitals: A concept analysis. Motsaanaka MN, Makhene A, Ndawo G. Motsaanaka MN, et al. Health SA. 2022 Oct 26;27:1920. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v27i0.1920. eCollection 2022. Health SA. 2022. PMID: 36337451 Free PMC article.

- The influencing factors of clinical nurses' problem solving dilemma: a qualitative study. Li YM, Luo YF. Li YM, et al. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2022 Dec;17(1):2122138. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2022.2122138. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2022. PMID: 36120892 Free PMC article.

- Basic Empathy Scale: A Systematic Review and Reliability Generalization Meta-Analysis. Cabedo-Peris J, Martí-Vilar M, Merino-Soto C, Ortiz-Morán M. Cabedo-Peris J, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2021 Dec 24;10(1):29. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10010029. Healthcare (Basel). 2021. PMID: 35052193 Free PMC article. Review.

- Empathy and Mobile Phone Dependence in Nursing: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Public Hospital of the Island of Crete, Greece. Rovithis M, Koukouli S, Fouskis A, Giannakaki I, Giakoumaki K, Linardakis M, Moudatsou M, Stavropoulou A. Rovithis M, et al. Healthcare (Basel). 2021 Jul 31;9(8):975. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9080975. Healthcare (Basel). 2021. PMID: 34442112 Free PMC article.

- Abaan S., & Altintoprak A. (2005). Nurses' perceptions of their problem solving ability: Analysis of self apprasials. Journal of School Nursing, 12(1), 62–76. (Original work published in Turkish)

- AbuAlRub R. F. (2004). Job stress, job performance, and social support among hospital nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(1), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04016.x - DOI

- Ançel G. (2006). Developing empathy in nurses: An inservice training program. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 20(6), 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2006.05.002 - DOI

- Ashker V. E., Penprase B., & Salman A. (2012). Work-related emotional stressors and coping strategies that affect the well-being of nurses working in hemodialysis units. Journal of the American Nephrology Nurses' Association, 39(3), 231–236.

- Association of periOperative Registered Nurses. (2015). Guidelines for perioperative practice (p. 694). Denver, CO: Author.

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Wolters Kluwer

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

How to Empathize: Resist Being a Problem Solver

When someone comes for help, don’t hand out a to do list.

Posted April 30, 2018

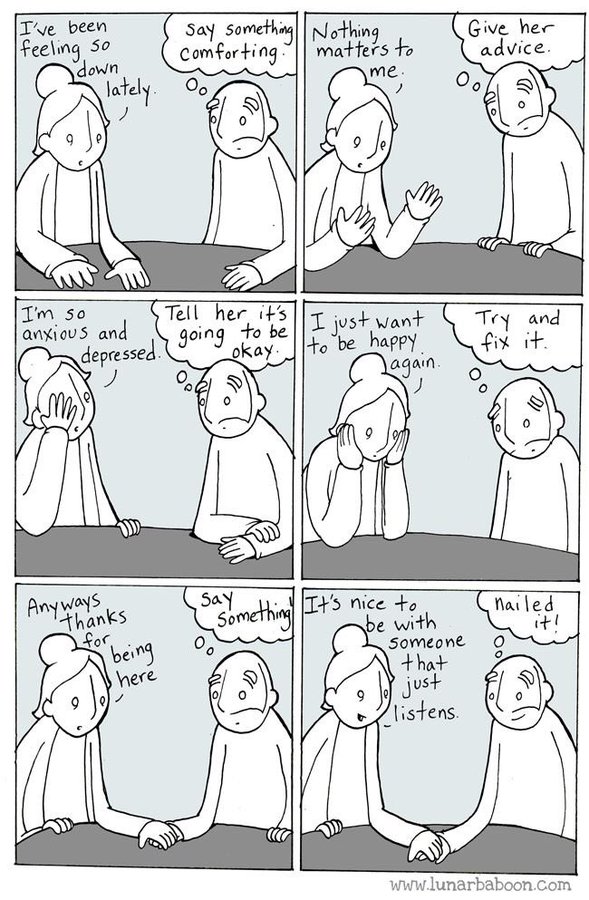

Human beings. What are we going to do with ourselves? We are born fixers. And I mean literally, born , as in since the dawn of time. When there were cracks in those cave walls, you can be sure we were there with our primitive spackling tools to patch them right up. Well, OK, home improvement was not quite the priority on the honey-do list, what with the more immediate issues—predatory birds, lions, poisonous snakes, the occasional out of hand neighbor. The kinds of things we had to fix back in the day were life and death. And thus it was in that milieu of danger at every turn that our inner alarm system—our fight-or-flight responsiveness to threat—developed. So while we have the amygdala, the C.O.O. of the brain’s alarm system, to thank for bringing us to this day there’s a bit more she wrote. Sensitivity (reading the fine print of a situation) is not the amygdala’s strong suit. So when we find ourselves feeling threatened not by a large bird with claws, but none other than our adult daughter standing before us upset about a non-large bird issue like, maybe, just for the sake of argument…having a stressful situation at work, it’s the amygdala showing up first that instantly makes us feel like our child’s distress is a fire to put out. In those moments that call for empathy, compassion and soothing, the amygdala shouting fire! is more of the problem than the solution.

I know this well. As an anxiety therapist, I speak to patients all day about ways to override and reset the amygdala when the proverbial snake turns out to be a harmless stick. And though I try to live by what I teach, there are those moments where my blindspots are pointed out to me. Like by my daughter and the aforementioned situation at her job, right away I picked up my spackler and got to work. I jumped in with all the different ways my daughter might look at the situation, all the different things she could do to make it better. In fact, I had so much to say about her situation, I’m not sure she could get a word in edgewise. What she wanted, in her words, was empathy, period , and I handed her a to do list. Gotcha.

Whether we are talking to our children, our coworkers, our partners, even ourselves, I think my daughter hit the nail on the head. When we are upset we want empathy, period . Not the laundry list of things we need, could, or should do. Not yet, and maybe not ever. At the very least we need to pause and listen, the longer the better, before we ask if those spackling tools that our primitive instincts are tapping behind our backs are actually being requested.

How do we do this? How do we tell our amygdalas to send the fire trucks back to the station? How do we turn off our revving engines running circles around an unsuspecting troubled person who has come to us for comfort, but is getting more upset by our (even with a Ph.D. in psychology) bungled response? What’s really the fire? We need to take charge of our own discomfort with someone else’s discomfort and realize our desire to solve things or to make invisible the things we can’t solve is…. drumroll please… our own problem—not the other person’s. The person who is in need of soothing was not in emergency mode until they were inundated with our to-do list for them. Not exactly what we were going for. If we as helpers can punch in the security code of our own amygdalas, do an override, take a breath, and remind ourselves that what is needed from us is not the brave slaying of dragons and such, but sometimes the braver offering of compassionate words or simply saying “yes—that sounds hard,” or “I’m sorry that’s happening,” or EVEN: “Tell me more about it” (because our to do list essentially conveys: tell me less ) we will be a different kind of hero. We are protecting ourselves and each other from our desire to fix and in so doing, will find a place where understanding ripples out and smooths the way for all of us.

And when each of us forgets about this idea, which we inevitably will given our jumpy amygdalas, let’s just agree to turn to each other and say, “Empathy, period , please!” Or… if you prefer… “Hold the spackler, please.” Namaste.

©2018 Tamar Chansky, Ph.D. www.tamarchansky.com

Tamar Chansky, Ph.D. is author of Freeing Yourself from Anxiety: 4 Simple Steps to Overcome Worry and Create the Life You Want and Freeing Your Child from Anxiety.

Tamar Chansky, Ph.D., is a psychologist dedicated to helping children, teens, and adults overcome anxiety.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

HOME - open only this page - put into left frame

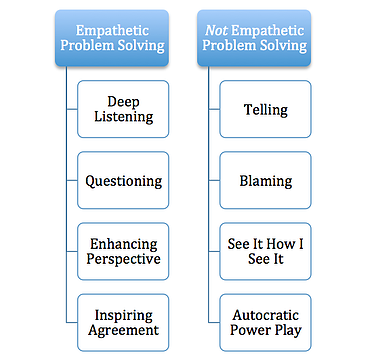

Empathy in problem solving , for projects and relationships.

Understanding other people, by thinking with empathy, is almost always essential for skillful design thinking, for solving problems. You use design thinking (with empathy) for almost everything in life , so empathy can help you achieve a wide variety of objectives, in design projects and in relationships as described in an overview of using empathy in Design-Thinking Process by asking empathy questions — "What do THEY want?" and "What do I want?" and, combining these, "What do WE want?" — while you're trying to achieve win-win results.

In the following sections about empathy, later we'll explore the similarities between Empathy (to understand others) & Metacognition (to understand self) and will examine the Empathy-Ecology of a Classroom .

But we'll begin by asking...

What is empathy?

It's useful to think about — and think with, * and cultivate in yourself & others — different kinds of empathy : Cognitive Empathy by cognitively understanding the feeling-and-thinking and behaviors of another person; Emotional Empathy (aka Affective Empathy ) by feeling what another person feels; Compassionate Empathy (aka Compassion or Empathic Concern or Compassionate Concern ) is a desire for the well-being of another person.

For most purposes, including education, it seems more useful to think about 2 kinds of empathy (Cognitive & Emotional) instead of 3, and to focus on the Cognitive Empathy that I think is more learn-able and generally is more beneficially useful for problem solving, for making things better. * Why 2, not 3? Instead of Compassionate Empathy, I prefer the term Empathic Concern because it places attention on the compassionate Concern (the Compassion ) that is produced by Cognitive Empathy (perhaps combined with Emotional Empathy ) and is motivated by Kindness . / * There is wide variation in the terms used, and their definitions; a comprehensive Literature Review about Empathy Training includes a recognition that "there are as many researchers acknowledging discrepancies in the use of the term, as there are inconsistent definitions." many definitions of empathy(s)

also - How wide is the scope of "others"? In addition to other humans, we also can have empathy for animals — such as a monkey or dolphin, dog or cat, parrot or lizard — although the accuracy of our empathy is limited by significant differences between us and them in our experiences of thinking & feeling, and our difficulties in communicating with them.

* Do we "think with" empathy? Both kinds of empathy, cognitive and emotional, are important. But this is a website about thinking that is productive for problem solving, so I'll be saying more about Cognitive Empathy, which is the ability to understand what another person is thinking-and-feeling.

Developing and Using a Growth Mindset for

Improving emotional-and-social intelligence.

As part of a whole-person education for ideas-and-skills & more a teacher can help students learn how to more effectively use both kinds of empathy, by improving their Cognitive Empathies and Emotional Empathies, and their skills in being aware (cognitively and emotionally) of the thinking & feeling of others in a wide variety of life-situations, and also (with metacognitive self-empathy ) of themselves. These essential components of Emotional Intelligence* are closely related to Social Intelligence. Students can improve all of their multiple intelligences (including emotional-and-social) when they develop-and-use a growth mindset by believing that their abilities are not fixed at the current levels, instead each ability can become better, can be “grown” when they invest intelligent effort to improve this kind of ability.

* Psychology Today describes Emotional Intelligence as "the ability to identify and manage one’s own emotions, as well as the emotions of others. Emotional intelligence is generally said to include at least three skills: emotional awareness, or the ability to identify and name one's own emotions [by using self-empathy, and by using empathy to "identify and name" another person's emotions]; the ability to harness those emotions and apply them to tasks like thinking and [to "make things better" in ways that include improved relationships] problem solving; and the ability to manage emotions, which includes both regulating one's own emotions when necessary, and helping others to do the same." { em phasis and [comments] added by me}

Two closely related abilities – Social Intelligence and Emotional Intelligence – are combined in educational programs * to improve the Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) that is briefly defined by ca sel .org — "social and emotional learning (SEL) is the process through which children and adults understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions" — in the introduction for What is SEL? { * and people improve these skills informally by learning from their life-experiences }

As part of a school's Social-Emotional Learning to improve Social Intelligence and Emotional Intelligence , teachers can help students improve their Cognitive Empathy & Emotional Empathy and their Empathic Concern and Compassionate Action.

Compassion in Action: A process that produces compassionate action occurs in a sequence: cognitive empathy and/or emotional empathy, plus kindness, may produce empathic concern for a person, which may produce a desire to help them, and then action to help them. / The whole process can occur quickly, as with emergency action, or during a long period of time. Or action may not occur at all, if the sequence is broken at any point.

Compassion in Design: A process of design may lead to Compassionate Action if, for any area of life, * Empathic Concern is a motivating-and-guiding factor when you Define a Problem by Choosing an Objective and Defining Goal-Criteria. { * compassionate action can be motivated by empathic concern in traditional design projects and in relationships }

Is empathy always useful? In most design projects – even when you are not motivated mainly by compassion – it's very useful to think with empathy . { why do I say "most" projects, instead of “all”? } And self-empathy , to understand yourself, is useful when your objective is a personal decision or a personal thinking strategy . {more about empathy and self-empathy }

Human-Centered Design: Because "empathy is the foundation of a human-centered design process," d.school (of Stanford) emphasizes the importance of a mode for Empathy by including it (when you search for "empath") in 19 of its 47 pages. And one of their mindsets for design-thinking is to Focus on Human Values. { Empathy in Design Thinking with d.school and DEEPdt} { designing with empathy and self-empathy }

Accuracy in Empathy

Do you have an accurate understanding of people? If you are surprised by a behavior — because your Observations (of how a person responds, in what they do or say) don't match your Predictions (your expectations) — something is wrong with your empathetic understanding of the way other people are thinking & feeling, of how they will respond in this situation. Why?

When you do a Reality Check by comparing Predictions with Observations, a mis-match can occur due to...

your inadequate Observations in the past, or your incorrect interpretations of these Observations when you constructed an explanatory Theory/Model (used to make Predictions ) for this aspect of human feeling/thinking-and-behaving, in one of the areas (re: psychology, sociology, economics, marketing, politics,...) studied by Social Sciences. Or maybe the other person(s) responded in an unusual way, not consistent with their previous feeling & thinking & actions.

view only this page - put into left frame

Empathy in design projects.

In all phases of a traditional Design Project — especially in Modes 1A and 1B when you Choose an Objective and Define Desired Goal-Properties for a product (or activity, strategy, theory) — it's important to think with empathy. This is important for your Solution-Users and for those (you and maybe others) who are Solution-Designers.

Empathy for Solution-Users: You learn about the thinking-and-behavior of potential users of a product by getting observations — old (already known by yourself or others) or new (from your own new studies) from customer interviews, focus groups, market surveys,... — that help you understand, with better insights into “how will they use the product? what do they need? and want?” Ask users for feedback (positive & negative), for constructive criticism and suggestions. By creatively imagining what it's like to “be a user and think like a user” from their perspective, make predictions. * Also try to “think like a buyer” or (in another aspect of the project) to “think like a seller.” These information-gathering activities will help you supplement your internal egocentric thinking with externally-oriented empathetic thinking for all stake - holders in a project, for everyone who will be involved in (or affected by) the project in any way, who will design, make, market, distribute, sell, buy, use, or service the product, or be involved or affected in other ways.

* Predictive Empathy: Usually you'll try to "think like a buyer/user" in their future, which may differ from their thinking in the present. For example, Helen Walters describes the "approach to customer research [of Steve Jobs, who said] ‘It isn't the consumers' job to know what they want.’ Jobs is comfortable hanging out in the world of the unknown, and this confidence allows him to take risks and make intuitive bets" by using empathy-based predictions of what buyers/users will want later, even if they don't yet want it now.

Relevant Empathy: You can never fully understand another person. Usually your main goal is relevant empathy, by trying to understand what is most important for a particular situation. If you're designing a product, for example, you'll want to understand the thinking & feeling, the needing and wanting, of people who would use (or might buy) the product, in the context of their using the product and/or b uying it. And for a relationship-situation, usually you focus on understanding what is most relevant in the context of that situation.

Empathy for Solution-Designers: During a design project you'll want to develop empathy for solution-users (those you are serving), as described above . And when you're co-designing as part of a group, you'll want to develop empathy for the other solution-designers in your team, to make your process of cooperative problem-solving more enjoyable and productive. If members of a group improve their use of “collaborative empathy” this will improve their interactions, and will help them develop a cooperative community for creative collaboration . This can occur in many contexts, including schools where better educational teamwork (by everyone involved in education ) will make the process more enjoyable for teachers, and more effective for students by increasing positives (in learning, performing, enjoying ) and decreasing negatives (like jealous attitudes & bullying behaviors). { building empathy-ecology in a classroom }

Traditional and Relational: Empathy is useful whenever you want to solve a problem by “making it better” with a traditional design project ( above ) — when you use empathy to produce a better solution (for your solution-users ) and a better process (if you're working in a team of solution-producers ) — and/or a relational design project (below) when your objective is to improve an interpersonal relationship.

Empathy in relationships .

An Important Objective: Originally I defined four general categories for problem-solving objectives – for when we decide to design a better product, strategy, activity, and/or theory. Later I added relationships because our most important problems (our opportunities to make things better ) usually involve people, so improved relationships are among the most important objectives we can choose to improve. How? An essential foundation is developing...

Empathy and Self-Empathy to improve Two Understandings: You can build a solid foundation for improving your relationships by improving two kinds of understandings (external and internal) with externally-oriented empathetic skills – to develop empathy (overall and also situation-specific relevant empathy ) based on external observations, trying to understand what others are feeling & thinking – and internally-oriented metacognitive skills (to develop self-empathy based on internal observations, trying to understand what you are feeling & thinking). The practical value of these life-skills is a reason to define...

Educational Goals for Relationship Skills: We can aim for whole-person education that will help students improve personally useful ideas & skills and more in their whole lives as whole people. Our educational goals should include the important life-skill of building better relationships, with empathy & kindness and in other ways. A very useful general strategy — for educating students (and yourself) in all of the multiple intelligences, including social-emotional intelligences — is to develop & consistently use a growth mindset .

Kindness plus Empathy: When you want to be kind — and you combine your kindness with empathy — this will help you...

Choose a Win-Win Goal: In many common life-situations, when you are trying to "make things better" your two understandings (external for others, and internal for self) are combined when you ask — while you are defining your goals — “what do they want?” (using empathy to understand others ) and (using self-empathy to understand yourself ) “what do I want?” and (if you choose to define your goal as an optimal win-win result ) “what do we want?” / You also make choices when you...

Define the Scope of Your Win-Win Goals: How broadly do you define "they" when you're trying to achieve win-win results? If you want to decrease the unfortunate tendency of positive teamwork to become negative tribalism, one strategy is for you (and those you influence) to increase your...

Understanding and Respect: One of the many ways we can improve relationships is to develop better teamwork . But one strategy for developing strong relationships among insiders (within a team) — by promoting hostile “us against them” attitudes toward outsiders (not in the team) — can convert positive teamwork into negative tribalism. { I'm calling it negative tribalism because tribe-like strong loyalties produce some positive effects and some negative effects. } One kind of educational activity that can help reduce the negative aspects of tribalism is examined in a page describing how my favorite high school teacher, by using informative debates in his civics class, helped us develop Accurate Understandings and Respectful Attitudes . How? After he helped us carefully-and-diligently study an issue, so our understandings of different position-perspectives were more accurate and thorough, usually we recognized that even when we have justifiable reasons to prefer one position, * people on other sides of an issue may also have justifiable reasons, both intellectual and ethical, for believing as they do, so we learned respectful attitudes. { * yes, he wanted us to find "justifiable reasons" because his educational goal was not a logically-fuzzy postmodern relativism , instead he promoted a logically appropriate humility with confidence that is not too little and not too much.} When this kind of educational process is done well, it can produce a foundation of empathetic understanding that is useful for producing authentic understanding & respect, that helps us be more kind in our feeling & thinking & actions.

Empathy without Kindness: This can be a bad combination, when it allows the use of empathetic thinking as a tool for manipulating others in harmful ways.

Empathy plus Kindness: This is a good combination, when empathy (a useful skill) is accompanied by kindness (an essential aspect of good character). Thinking with empathy is beneficial for other people when it's combined with kindness-and-caring in feeling & thinking & actions, when an attitude of caring for others (in feeling & thinking) leads to caring for others (in actions), with actions motivated by kindness, by genuinely caring for other people.

Kindness in Thinking-and-Actions: More people will have better lives... if more of us are more often motivated by kindness, with goals of trying to “make things better” for other people, wanting to affect their lives in ways that are beneficial for them, that make life better for them; and if our empathy-based compassionate concerns were more often actualized with kindness in our actions.

A Wonderful Life produces Beneficial Effects: A creative illustration of helping others is my favorite movie, It's a Wonderful Life. I like it partly for its artistry (in plot, dialogue, acting, directing, photography) but mainly for the message: each of us affects other people – as dramatized in the end-of-movie comparison of lives with & without George Bailey – and our own life is better when we affect others in ways that make their lives better, and help them achieve worthy goals in life. We can help others enjoy what they do, and (when they “pass it on”) do more actions that benefit others, and more fully develop their whole-person potentials.

Helping Others achieve Their Goals: For understanding how we can be more beneficial — by helping another person "enjoy..." and "more fully develop their whole-person potentials" so they are becoming a better version of themself, growing into the kind of “ideal person” they want to be, or they should be — a useful perspective is the Michelangelo Phenomenon; this concept was developed by social psychologists, with Caryl Rusbult ( my wonderful sister ) being a main developer. As described in a review article by Rusbult, Finkel, & Kumashiro: "close partners sculpt one another's selves, shaping one another's skills and traits [analogous to Michelangelo's Actions while shaping a piece of stone so it becomes a beautiful work of art] and promoting versus inhibiting one another's goal pursuits... of attaining his or her ideal-self goals" in the "dreams and aspirations, or the constellation of skills, traits, and resources that an individual ideally wishes to acquire." When lovingly influential Michelangelo Actions are done well, the beneficial effects usually are lovingly appreciated, as we see in "Love" by Roy Croft: "I love you, not only for what you have made of yourself, but for what you are making of me." Or in the language of education, when feedback-actions help another person improve, this is formative feedback that helps them “form themselves” into a better person. Of course, a beneficial shaping influence — a teaching influence that helps them develop a growth mindset about improving their skills with social-emotional intelligences and relational empathy — can come from a "close partner" and also others, including friends and family, counselors, fellow students & team members & co-workers, and teachers & coaches & supervisors.

Golden Rule with Empathy: For building mutually beneficial relationships, one useful principle-for-life is a Golden Rule with Empathy that combines kindness with empathy, by treating others in ways THEY want to be treated, which may differ from what you would want. * Treating others this way will be beneficial for them, and also for you (especially in the long run), in a wide variety of situations. / * But it doesn't really "differ from what you would want," if we look more deeply. Why? You want others to empathetically understand you, and then treat you the way you want to be treated. Other people also want this, so you should Seek First to Understand (with Habit 5 in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People ) and then use a Golden Rule , e.g. "Do for others what you want them to do for you" by treating them the way THEY want to be treated.

Empathy for Society: I.O.U. – This paragraph might be written before mid-2023, with ideas from John Rawls: imagine you are part of a group in Original Position (before you're born) that is designing a society with the goal of making life optimal for all, and you are self-interested in "all" because – with a Veil of Ignorance – you don't know “who you will be” when you are born, re: your multiple intelligences, looks, race, health, wealth, status, location,... ; in reality we cannot be “ignorant of our situation” now, during life as it really is, but we can use empathy + kindness/compassion in our thinking about society. {for more, an article by Richard Beck, Empathy, the Veil of Ignorance, and Justice }

Clever and Kind: Abraham Heschel, sharing an insightful observation based on self-empathy, wisely said "When I was young, I admired clever people. Now that I am old, I admire kind people." Teachers can help students, while they are still young, appreciate the value of being truly clever (with skills in creative-and-critical productive thinking to solve problems to make things better) and also kind.

Empathy and Metacognition

These related ways of thinking – helping you understand others , and understand yourself – are very useful in all areas of life, including education. This section — first in Goals & Perspectives, then in RESULTS and PROCESS , and Using Empathetic Feedback in a Classroom — will examine ideas & strategies that can help a teacher and students develop better empathy-ecology in their classroom .

Goals & Perspectives

Empathy and Metacognition have similar goals (to understand thinking & feeling) but different orientation-perspectives, re: external and internal.

• With empathy you try to understand the thinking & feeling of others, who are external to you. { two empathies and a result : cognitive empathy (used "to understand" thinking & feeling) plus emotional empathy (to feel) can produce empathic concern. } • With metacognition ( self-empathy ) you try to understand your own internal thinking (& feeling). { In its basic definition, with metacognition you "think about your thinking. " But in practice, thinking and feeling are related, often with strong mutual influences. Therefore, typically it's useful to “think about your thinking AND feeling . ” }

External & Internal, for You and Others:

everyone – you and others – thinks with externally-oriented empathy, to understand the thinking & feeling of other people; everyone – you and others – thinks with internally-oriented metacognition, to understand your own thinking & feeling.

The external & internal understandings constructed by you are summarized in the 1st & 2nd rows-of-cells in this table.

The 3rd & 4th cell-rows describe the external & internal understandings constructed by another person .

| and ) | ||

| by you, for ANOTHER PERSON, is | external understanding of , of | |

| by you, for YOURSELF, aka is | internal understanding of , of | |

| by another person, for YOU, is | understanding of , of | |

| by another person, for THEMSELF, is | understanding of , of |

Metacognition and Self-Empathy: These terms have the same meaning, in this page. More generally, when these terms are used by others, typically with metacognition the emphasis is more heavily on thinking, and with self-empathy it's on feeling (but also thinking).

other terms: a metacognitive understanding is aka personal metacognitive knowledge that is one aspect of a person's overall general-and-personal metacognitive knowledge . By analogy, empathetic understanding also can be called empathetic knowledge, although the term metacognitive knowledge is used much more often.

RESULTS — Perspectives and Understandings

By comparing understandings of YOU in the 2nd & 3rd cell-rows, or of THEM in the 1st & 4th rows, you can see how understandings ( of YOU , or of THEM ) depend on point-of-view perspectives (on whether the constructing is done by you , or by them ).

two pov-perspectives on YOU, in rows 2 & 3: You use internal metacognition (self-empathy) to construct your understanding of YOUR thinking & feeling. And another person uses external empathy to construct their understanding of YOUR thinking & feeling. It can be interesting to compare these two understandings, asking “How do I view me? How do they view me?” and “What are the similarities? and differences?” and “Why do the differences occur?” and “Which understanding is more accurate ? and in what ways?”

three pov-perspectives on ANOTHER PERSON, in rows 1 & 4 & _: You also can make comparisons and ask questions (about similarities & differences, and accuracy), re: understandings of ANOTHER PERSON – “How do I view THEM ? How does this person view THEMSELF ? And, not shown in the table, how do other people view THEM ?”

When we compare empathy (to understand others) with metacognition (to understand self), we see many similarities and analogous relationships in the PROCESS used (below) and (above) the RESULT produced .

PROCESS — constructing Empathy & Metacognition

Now we'll shift attention from RESULTS to PROCESS.

We construct our understandings (of others & self) in a social context, so it's useful to distinguish between...

Understanding and Feedback: We construct (i.e. we develop) feedback in a two-step process. First we use empathy or metacognition to construct understanding that we use, after evaluative filtering, to provide feedback for others, with communication. { Understanding and Feedback, Part 2 }

You construct your external EMPATHY (it's your understanding of ANOTHER PERSON ) when you internally interpret all of the evidence you find. You can use three kinds of evidence: your observations of the person ; feedback about the person from other people; feedback about self from the person.

You construct your internal SELF-EMPATHY (to get your understanding of YOURSELF ) when you internally interpret all of the evidence you find. You can use two kinds of evidence: your observations of yourself ; and feedback about you from others.

{an option: If the table below is too wide for easy reading in your browser window, you can temporarily view this page in a new full-width window . }

The first 4 rows in the tables above (for RESULTS) and below (for PROCESS) are matched, re: who is trying to understand WHO . Below,

The 1st and 2nd rows summarize-and-organize the processes you use to construct your understandings of ANOTHER and YOURSELF . The 3rd and 4th rows describe how, using the same processes, another person constructs their other-understanding of YOU , and their self-understanding of THEMSELF . The 5th row shows how they construct their other-understanding of ANOTHER PERSON, of someone who isn't YOU or THEM, and thus is a THIRD PERSON .

| , trying to , is | , using found-evidence that is empathetic of-person , empathetic about-person , metacognitive about-person , | about ] |

| , trying to , is | , using found-evidence that is metacognitive of-self , empathetic about-you , | of ] |

| , trying to , is | , using found-evidence that is empathetic of-you , metacognitive about-yourself , empathetic about-you , | about ] |

| , trying to , is | , using found-evidence that is metacognitive of-self , empathetic about-them that can include about-them , | of ] |

| , trying to , is | , using found-evidence that is empathetic of-third , metacognitive about-third , empathetic about-third that can include about-third , | about a ] |

Did you notice that the 3rd & 5th rows are analogous but with one difference? (what is it? the 5th-row process can include one extra evidence that is "feedback-about-third from you")

Understanding and Feedback — These are related, but different. They occur in sequence:

1. First you use empathy and observations-of-performance, trying to get accurate understandings of another person(s), and of their performance(s). 2. Then if you want to provide helpful feedback, * you will wisely filter your understandings by not saying everything you are thinking, but only what will be helpful. You do this by deciding, for each person or group, what to say (and not say), when and how, or whether to say nothing. The goal is to be helpful by providing formative feedback with an intention, and hopefully a result, of being kind and beneficial . / * Unfortunately, sometimes (if a person doesn't want to be kind-and-beneficial) the feedback is intended to be un-helpful. 1-during-2: An empathetic understanding (developed in Step 1) is used (in Step 2) during the process of filtering, when you're deciding the details (the what/when/how-and-whether) of providing feedback that will be helpful.

MORE - Other useful strategies for providing helpful feedback are in two places: Developing a Creative (and critical) Community by trying to minimize any "harshness" in feedback-providing and feedback-receiving; Evaluation is Argumentation that in a group requires "the social skills of communication" when you combine Evaluative Thinking with a Persuasion Strategy and Communication Skills, along with productive Attitudes while Arguing.

Using Empathetic Feedback in a Classroom

The three * s — above in the table-for-process and below in descriptions of each * — are three kinds of "feedback... from you ." Imagine that you are a teacher , and two of your students are Sue (" a person ", aka " them ") and John (" a third person ", aka " third ").

How will you use these 3 kinds of empathy-based feedbacks? If you're an effective teacher, then (in cell-Rows 4, 5, and 3)...

* You want to provide feedback that will help Sue construct a better self-understanding of HERSELF . (This is her SELF-EMPATHY, aka her METACOGNITION, in Row 4.) / a new term: Sue's own internal METACOGNITION (by "thinking about Sue's thinking) is being supplemented by your feedback-to-her about her, which is aka external metacognition because it's the "thinking about Sue's thinking" that is externally supplied by you, as an empathetic observer. * You want to provide feedback that will help Sue (and other students) construct a better other-understanding of JOHN . (This is her EMPATHY for A THIRD PERSON in Row 5.) / You can provide feedback-to-others about all of your students, individually and collectively, to influence each student's other-understandings of their fellow students, and attitudes toward them. * You want to provide feedback that will help Sue construct a better other-understanding of YOU . (This is her EMPATHY for YOU in Row 3.)

With a particular feedback, you want to help a student understand themself (Row 4), or another student (Row 5), or you (Row 3).

Building an Ecology of Empathy in a Classroom

All of these * -feedbacks are one part of the complex personal interactions (simplistically symbolized in the diagram) that occur in every classroom. In this context, "better self-understanding" and "better other-understanding" will help all of you — Teacher , Student (like Sue or John), and students (in the whole class, or in smaller groups) — develop a better ecology of empathy in your classroom.

In the interactions-diagram, arrows indicate a variety of interactions, including communications that are verbal (with * -feedbacks and in other ways) and non-verbal:

two arrows point away from the Teacher (you) who can communicate with only one Student (like Sue) or with two or more students . two arrows point away from the Student (Sue) who can communicate with you , or with one or more other students . two arrows point away from students (John & others) who can communicate with you , or with any other Student (s). {note: A complex diagram that is more-complete would show more kinds of interactions between students, as individuals and in groups.}

A skilled teacher will provide guidance for students in how to " wisely filter " their communications (using feedback and in other ways) with the teacher and each other, so their interactions will be helpful. A wise evaluating-and-filtering should be based on a foundation of healthy interpersonal motivations, with each student wanting to be kind, wanting to affect others in beneficial ways.

Shared Goals and Individual Goals: In ideal educational teamwork the teacher and all students will have shared educational goals of “greatest good for the greatest number” with optimal learning-performing-enjoying for everyone in the classroom. But each student also will have their own personal goals that include wanting to improve their interpersonal relationships and personal education .

Habit 5 of Highly Effective People is "Seek first to understand, then to be understood. " As a teacher, you can use this habit/principle in (at least) two ways:

When you provide feedback , in Step 1 you try to understand Sue, as a foundation for Step 2 when you help her understand your view of her and what she is doing and how she can improve. {your feedback is one aspect of stimulating and guiding students} In the third * -feedback you try to understand Sue, so (with your * -feedback about yourself) you can help her understand you .

Building Empathy-Ecology for a Classroom

I.O.U. - Below are some ideas that eventually, maybe by mid-2019, will be developed more fully.

a humble disclaimer: This section is just ideas, and most of the ideas (maybe all of them) aren't really new. I'm just describing some goals of skilled teachers, and some strategies they already are using to effectively pursue their goals.

Important foundational ideas, essential for this section, are in other parts of the website: