Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.1 Culture and the Sociological Perspective

Learning objectives.

- Describe examples of how culture influences behavior.

- Explain why sociologists might favor cultural explanations of behavior over biological explanations.

As this evidence on kissing suggests, what seems to us a very natural, even instinctual act turns out not to be so natural and biological after all. Instead, kissing seems best understood as something we learn to enjoy from our culture , or the symbols, language, beliefs, values, and artifacts (material objects) that are part of a society. Because society, as defined in Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective” , refers to a group of people who live in a defined territory and who share a culture, it is obvious that culture is a critical component of any society.

If the culture we learn influences our beliefs and behaviors, then culture is a key concept to the sociological perspective. Someone who grows up in the United States differs in many ways, some of them obvious and some of them not so obvious, from someone growing up in China, Sweden, South Korea, Peru, or Nigeria. Culture influences not only language but the gestures we use when we interact, how far apart we stand from each other when we talk, and the values we consider most important for our children to learn, to name just a few. Without culture, we could not have a society.

The profound impact of culture becomes most evident when we examine behaviors or conditions that, like kissing, are normally considered biological in nature. Consider morning sickness and labor pains, both very familiar to pregnant women before and during childbirth, respectively. These two types of discomfort have known biological causes, and we are not surprised that so many pregnant women experience them. But we would be surprised if the husbands of pregnant women woke up sick in the morning or experienced severe abdominal pain while their wives gave birth. These men are neither carrying nor delivering a baby, and there is no logical—that is, biological—reason for them to suffer either type of discomfort.

And yet scholars have discovered several traditional societies in which men about to become fathers experience precisely these symptoms. They are nauseous during their wives’ pregnancies, and they experience labor pains while their wives give birth. The term couvade refers to these symptoms, which do not have any known biological origin. Yet the men feel them nonetheless, because they have learned from their culture that they should feel these types of discomfort (Doja, 2005). And because they should feel these symptoms, they actually do so. Perhaps their minds are playing tricks on them, but that is often the point of culture. As sociologists William I. and Dorothy Swaine Thomas (1928) once pointed out, if things are perceived as real, then they are real in their consequences. These men learn how they should feel as budding fathers, and thus they feel this way. Unfortunately for them, the perceptions they learn from their culture are real in their consequences.

The example of drunkenness further illustrates how cultural expectations influence a behavior that is commonly thought to have biological causes. In the United States, when people drink too much alcohol, they become intoxicated and their behavior changes. Most typically, their inhibitions lower and they become loud, boisterous, and even rowdy. We attribute these changes to alcohol’s biological effect as a drug on our central nervous system, and scientists have documented how alcohol breaks down in our body to achieve this effect.

Culture affects how people respond when they drink alcohol. Americans often become louder and lose their sexual inhibitions when they drink, but people in some societies studied by anthropologists often respond very differently, with many never getting loud or not even enjoying themselves.

Melissa Wang – bp tourney – CC BY-SA 2.0.

This explanation of alcohol’s effect is OK as far as it goes, but it turns out that how alcohol affects our behavior depends on our culture. In some small, traditional societies, people drink alcohol until they pass out, but they never get loud or boisterous; they might not even appear to be enjoying themselves. In other societies, they drink lots of alcohol and get loud but not rowdy. In some societies, including our own, people lose sexual inhibitions as they drink, but in other societies they do not become more aroused. The cross-cultural evidence is very clear: alcohol as a drug does affect human behavior, but culture influences the types of effects that occur. We learn from our culture how to behave when drunk just as we learn how to behave when sober (McCaghy, Capron, Jamieson, & Carey, 2008).

Culture and Biology

These examples suggest that human behavior is more the result of culture than it is of biology. This is not to say that biology is entirely unimportant. As just one example, humans have a biological need to eat, and so they do. But humans are much less under the control of biology than any other animal species, including other primates such as monkeys and chimpanzees. These and other animals are governed largely by biological instincts that control them totally. A dog chases any squirrel it sees because of instinct, and a cat chases a mouse for the same reason. Different breeds of dogs do have different personalities, but even these stem from the biological differences among breeds passed down from one generation to another. Instinct prompts many dogs to turn around before they lie down, and it prompts most dogs to defend their territory. When the doorbell rings and a dog begins barking, it is responding to ancient biological instinct.

Because humans have such a large, complex central nervous system, we are less controlled by biology. The critical question then becomes, how much does biology influence our behavior? Predictably, scholars in different disciplines answer this question in different ways. Most sociologists and anthropologists would probably say that culture affects behavior much more than biology does. In contrast, many biologists and psychologists would give much more weight to biology. Advocating a view called sociobiology , some scholars say that several important human behaviors and emotions, such as competition, aggression, and altruism, stem from our biological makeup. Sociobiology has been roundly criticized and just as staunchly defended, and respected scholars continue to debate its premises (Freese, 2008).

Why do sociologists generally favor culture over biology? Two reasons stand out. First, and as we have seen, many behaviors differ dramatically among societies in ways that show the strong impact of culture. Second, biology cannot easily account for why groups and locations differ in their rates of committing certain behaviors. For example, what biological reason could explain why suicide rates west of the Mississippi River are higher than those east of it, to take a difference discussed in Chapter 2 “Eye on Society: Doing Sociological Research” , or why the U.S. homicide rate is so much higher than Canada’s? Various aspects of culture and social structure seem much better able than biology to explain these differences.

Many sociologists also warn of certain implications of biological explanations. First, they say, these explanations implicitly support the status quo. Because it is difficult to change biology, any problem with biological causes cannot be easily fixed. A second warning harkens back to a century ago, when perceived biological differences were used to justify forced sterilization and mass violence, including genocide, against certain groups. As just one example, in the early 1900s, some 70,000 people, most of them poor and many of them immigrants or African Americans, were involuntarily sterilized in the United States as part of the eugenics movement, which said that certain kinds of people were biologically inferior and must not be allowed to reproduce (Lombardo, 2008). The Nazi Holocaust a few decades later used a similar eugenics argument to justify its genocide against Jews, Catholics, gypsies, and gays (Kuhl, 1994). With this history in mind, some scholars fear that biological explanations of human behavior might still be used to support views of biological inferiority (York & Clark, 2007).

Key Takeaways

- Culture refers to the symbols, language, beliefs, values, and artifacts that are part of any society.

- Because culture influences people’s beliefs and behaviors, culture is a key concept to the sociological perspective.

- Many sociologists are wary of biological explanations of behavior, in part because these explanations implicitly support the status quo and may be used to justify claims of biological inferiority.

For Your Review

- Have you ever traveled outside the United States? If so, describe one cultural difference you remember in the nation you visited.

- Have you ever traveled within the United States to a very different region (e.g., urban versus rural, or another part of the country) from the one in which you grew up? If so, describe one cultural difference you remember in the region you visited.

- Do you share the concern of many sociologists over biological explanations of behavior? Why or why not?

Doja, A. (2005). Rethinking the couvade . Anthropological Quarterly, 78, 917–950.

Freese, J. (2008). Genetics and the social science explanation of individual outcomes [Supplement]. American Journal of Sociology, 114, S1–S35.

Kuhl, S. (1994). The Nazi connection: Eugenics, American racism, and German national socialism . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lombardo, P. A. (2008). Three generations, no imbeciles: Eugenics, the Supreme Court, and Buck v. Bell . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

McCaghy, C. H., Capron, T. A., Jamieson, J. D., & Carey, S. H. (2008). Deviant behavior: Crime, conflict, and interest groups . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Thomas, W. I., & Thomas, D. S. (1928). The child in America: Behavior problems and programs . New York, NY: Knopf.

York, R., & Clark, B. (2007). Gender and mathematical ability: The toll of biological determinism. Monthly Review, 59, 7–15.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

3.4 Theoretical Perspectives on Culture

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- Discuss the major theoretical approaches to cultural interpretation

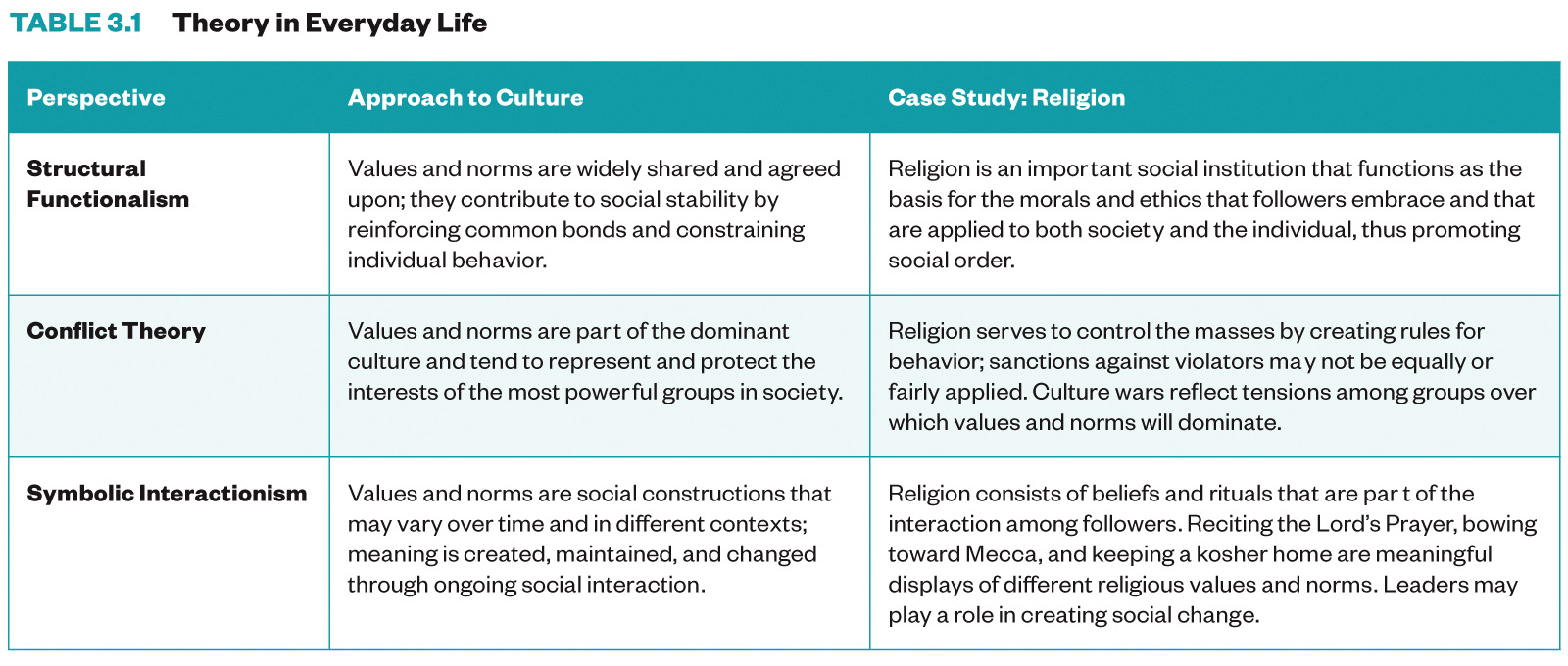

Music, fashion, technology, and values—all are products of culture. But what do they mean? How do sociologists perceive and interpret culture based on these material and nonmaterial items? Let’s finish our analysis of culture by reviewing them in the context of three theoretical perspectives: functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism.

Functionalists view society as a system in which all parts work—or function—together to create society as a whole. They often use the human body as an analogy. Looking at life in this way, societies need culture to exist . Cultural norms function to support the fluid operation of society, and cultural values guide people in making choices. Just as members of a society work together to fulfill a society’s needs, culture exists to meet its members’ social and personal needs.

Functionalists also study culture in terms of values. For example, education is highly valued in the U.S. The culture of education—including material culture such as classrooms, textbooks, libraries, educational technology, dormitories and non-material culture such as specific teaching approaches—demonstrates how much emphasis is placed on the value of educating a society’s members. In contrast, if education consisted of only providing guidelines and some study material without the other elements, that would demonstrate that the culture places a lower value on education.

Functionalists view the different categories of culture as serving many functions. Having membership in a culture, a subculture, or a counterculture brings camaraderie and social cohesion and benefits the larger society by providing places for people who share similar ideas.

Conflict theorists, however, view social structure as inherently unequal, based on power differentials related to issues like class, gender, race, and age. For a conflict theorist, established educational methods are seen as reinforcing the dominant societal culture and issues of privilege. The historical experiences of certain groups— those based upon race, sex, or class, for instance, or those that portray a negative narrative about the dominant culture—are excluded from history books. For a long time, U.S. History education omitted the assaults on Native American people and society that were part of the colonization of the land that became the United States. A more recent example is the recognition of historical events like race riots and racially based massacres like the Tulsa Massacre, which was widely reported when it occurred in 1921 but was omitted from many national historical accounts of that period of time. When an episode of HBO’s Watchmen showcased the event in stunning and horrific detail, many people expressed surprise that it had occurred and it hadn’t been taught or discussed (Ware 2019).

Historical omission is not restricted to the U.S. North Korean students learn of their benevolent leader without information about his mistreatment of large portions of the population. According to defectors and North Korea experts, while famines and dire economic conditions are obvious, state media and educational agencies work to ensure that North Koreans do not understand how different their country is from others (Jacobs 2019).

Inequities exist within a culture’s value system and become embedded in laws, policies, and procedures. This inclusion leads to the oppression of the powerless by the powerful. A society’s cultural norms benefit some people but hurt others. Women were not allowed to vote in the U.S. until 1920, making it hard for them to get laws passed that protected their rights in the home and in the workplace. Same-sex couples were denied the right to marry in the U.S. until 2015. Elsewhere around the world, same-sex marriage is only legal in 31 of the planet’s 195 countries.

At the core of conflict theory is the effect of economic production and materialism. Dependence on technology in rich nations versus a lack of technology and education in poor nations. Conflict theorists believe that a society’s system of material production has an effect on the rest of culture. People who have less power also have fewer opportunities to adapt to cultural change. This view contrasts with the perspective of functionalism. Where functionalists would see the purpose of culture—traditions, folkways, values—as helping individuals navigate through life and societies run smoothly, conflict theorists examine socio-cultural struggles, including the power and privilege created for some by using and reinforcing a dominant culture that sustains their position in society.

Symbolic interactionism is the sociological perspective that is most concerned with the face-to-face interactions and cultural meanings between members of society. It is considered a micro-level analysis. Instead of looking how access is different between the rich and poor, interactionists see culture as being created and maintained by the ways people interact and in how individuals interpret each other’s actions. In this perspective, people perpetuate cultural ways. Proponents of this theory conceptualize human interaction as a continuous process of deriving meaning from both objects in the environment and the actions of others. Every object and action has a symbolic meaning, and language serves as a means for people to represent and communicate interpretations of these meanings to others. Symbolic interactionists perceive culture as highly dynamic and fluid, as it is dependent on how meaning is interpreted and how individuals interact when conveying these meanings. Interactionists research changes in language. They study additions and deletions of words, the changing meaning of words, and the transmission of words in an original language into different ones.

We began this chapter by asking, “What is culture?” Culture is comprised of values, beliefs, norms, language, practices, and artifacts of a society. Because culture is learned, it includes how people think and express themselves. While we may like to consider ourselves individuals, we must acknowledge the impact of culture on us and our way of life. We inherit language that shapes our perceptions and patterned behavior, including those of family, friends, faith, and politics.

To an extent, culture is a social comfort. After all, sharing a similar culture with others is precisely what defines societies. Nations would not exist if people did not coexist culturally. There could be no societies if people did not share heritage and language, and civilization would cease to function if people did not agree on similar values and systems of social control.

Culture is preserved through transmission from one generation to the next, but it also evolves through processes of innovation, discovery, and cultural diffusion. As such, cultures are social constructions. The society approves or disapproves of items or ideas, which are therefore included or not in the culture. We may be restricted by the confines of our own culture, but as humans we have the ability to question values and make conscious decisions. No better evidence of this freedom exists than the amount of cultural diversity around the world. The more we study another culture, the better we become at understanding our own.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 3e

- Publication date: Jun 3, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/3-4-theoretical-perspectives-on-culture

© Jan 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Essays on the Sociology of Culture

DOI link for Essays on the Sociology of Culture

Get Citation

Karl Mannheim was one of the leading sociologists of the twentieth century. Essays on the Sociology of Culture , originally published in 1956, was one of his most important books. In it he sets out his ideas of intellectuals as producers of culture and explores the possibilities of a democratization of culture. This new edition includes a superb new preface by Bryan Turner which sets Mannheim's study in the appropriate historical and intellectual context and explains why his thought on culture remains essential for students engaged in debates about mass culture, the politics of culture and postmodernity.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter | 13 pages, introduction, part | 75 pages, towards the sociology of the mind, chapter | 11 pages, first approach to the subject, chapter | 34 pages, the false and the proper concepts of history and society, chapter | 23 pages, the proper and improper concept of the mind, chapter | 6 pages, an outline of the sociology of the mind, chapter | 1 pages, recapitulation: the sociology of the mind as an area of inquiry, part | 80 pages, the problem of the intelligentsia, part | 76 pages, the democratization of culture 1, chapter | 4 pages, some problems of political democracy at the stage of its full development, chapter | 72 pages, the problem of democratization as a general cultural phenomenon.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

1st Edition

Essays on the Sociology of Culture

- Taylor & Francis eBooks (Institutional Purchase) Opens in new tab or window

Description

Karl Mannheim was one of the leading sociologists of the twentieth century. Essays on the Sociology of Culture , originally published in 1956, was one of his most important books. In it he sets out his ideas of intellectuals as producers of culture and explores the possibilities of a democratization of culture. This new edition includes a superb new preface by Bryan Turner which sets Mannheim's study in the appropriate historical and intellectual context and explains why his thought on culture remains essential for students engaged in debates about mass culture, the politics of culture and postmodernity.

Table of Contents

Karl Mannheim

About VitalSource eBooks

VitalSource is a leading provider of eBooks.

- Access your materials anywhere, at anytime.

- Customer preferences like text size, font type, page color and more.

- Take annotations in line as you read.

Multiple eBook Copies

This eBook is already in your shopping cart. If you would like to replace it with a different purchasing option please remove the current eBook option from your cart.

Book Preview

Culture in Sociology (Definition, Types and Features)

Sourabh Yadav (MA)

Sourabh Yadav is a freelance writer & filmmaker. He studied English literature at the University of Delhi and Jawaharlal Nehru University. You can find his work on The Print, Live Wire, and YouTube.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Culture, as used in sociology, is the “way of life” of a particular group of people: their values, beliefs, norms, etc.

Think of a typical day in your life. You wake up, get ready, and then leave for school or work. Once the day is over, you probably spend your time with family/friends or pursue your hobbies.

Almost every aspect of this—your means of travel, how you behave among your colleagues, or what kind of recreation you prefer—comes under culture. It is something that we acquire socially and plays a huge role in shaping who we are.

Sociologists have come up with various theories about culture (why it exists, how it functions, etc.), which we will discuss later. But before that, let us learn about the concept in more detail and look at some examples.

Sociological Definition of Culture

Edward Tylor defined culture as

“that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” (1871)

Another definition comes from Scott, who sees culture as “all that in human society which is socially rather than biologically transmitted” (2014).

Since the beginning of civilization, humans have lived together in communities and developed common ways of dealing with life (acquiring food, raising children, etc.). These common ways are what make culture.

Culture consists of both intangible and tangible things. The former is known as nonmaterial culture, which includes things like ideas or values of a society. In contrast, material culture has a physical existence, such as a clothing item.

Both nonmaterial and material are linked because physical items often symbolize cultural ideas (Little, 2016). For example, you wear a suit (not a pair of shorts) to a business meeting, which is linked to the workplace values of formality & decorum.

Two of the most important elements of culture are its values & beliefs. Values refer to what a society considers good and just: individuality, for example, is a key value in most Western countries. Beliefs are the convictions that people hold to be true, such as the American belief that hard work can make anybody successful.

Values and beliefs are deeply entrenched in a culture, and going against them can have consequences. These can range from minor cultural sanctions (say being frowned upon) to major legal actions. In contrast, upholding values & beliefs leads to social approval.

Cultural values differ across cultures. The individualism of Western cultures seems solipsistic & arrogant to many Non-Western cultures, who instead value collectivism. Besides such variations, values also evolve with time.

Culture vs Society

The terms “culture” and “society” are often used interchangeably in everyday speech, but they refer to different things.

Society refers to a group of people who live together in a common territory & share a culture. This common territory can be any definable region, say a small neighborhood or a large country.

When we use the term “society”, we are referring to social structures & their organization.

Culture, in contrast, is the “way of life” of a group of people; it consists of values, beliefs, and artifacts.

For example, in the United States, African-Americans have historically been oppressed, and even today, they often do not get equal opportunities. Here, we are talking about social structures, which include race and class.

African-American culture has—such as the literary works of Zora Neale Hurston or the jazz music of Duke Ellington—developed in response to these (unfair) social structures. So, both society & culture are mutually connected; neither can exist without the other.

Features of Cultures

The following are 10 key features of culture that we explore in sociology:

- Symbols: Symbols can be words, gestures, or objects that carry particular meanings recognized by those who share the same culture. For instance, the bald eagle functions as a symbol of freedom and authority in American culture .

- Language: Language is a key aspect of culture, as it is the means of communication that conveys cultural heritage and values. For example, the French language, rich in literature and philosophy, reveals much about French culture’s emphasis on art, intellect, and romance.

- Rituals and Traditions: These are practices or ceremonies that are regularly performed in a culture and bear symbolic meaning. An example of a ritual would be Diwali, the festival of lights celebrated by Hindus, symbolizes the spiritual victory of light over darkness, good over evil.

- Norms: Norms are behavioral standards and expectations that culture sets. In British culture, for instance, queueing is a significant societal norm, signifying order and fairness. See: cultural norms .

- Values: These are the learned beliefs that guide individual and collective behavior and decisions, such as respect for human rights evident in many democratic societies. See: cultural values .

- Social Structures: Social structures are the arranged relationships and patterned interactions between members of a culture, like the extended family system prevalent in many Latin American cultures.

- Artifacts: Physical objects or architectural structures that represent cultural accomplishments, such as the Pyramids in Egypt representing ancient Egyptian civilization. See: cultural artifacts .

- Rules and Laws: Codified principles that guide societal behavior. For example, the constitution in the U.S. reflects its cultural emphasis on democracy and individual freedom.

- Religion and Spirituality: Beliefs about a higher power, rituals related to this belief, and moral codes derived from these beliefs. Buddhism, for instance, is a significant part of East Asian cultures.

- Food and Diet: Specific to each culture, these are dietary habits and special cuisines, like the Mediterranean diet filled with seafood, olives, and vegetables, reflecting coastal cultures of Greece and Italy.

Types of Culture in Sociology

- National Culture: This represents the shared customs, behaviors, and artifacts that characterize a nation, for instance, the Brazilian culture marked by energetic music and vibrant festivals.

- Subculture : A cultural group existing within larger cultures distinguished by their unique practices and beliefs. For example, The Amish in the United States have a distinct lifestyle centered around simplicity and community.

- Counterculture : This represents groups that reject mainstream norms and values, seeking to challenge the status quo. The Punk movement of the 1970s in the UK, known for its rebellious attitudes and alternative fashion, is a clear example. Countercultures often cause widespread moral panic among the dominant culture in a society .

- Folk Culture : Traditional, community-based customs representing the shared cultural heritage, such as folk music and folklore of Irish culture.

- Pop Culture : Mainstream trends influenced by mass media, fashion, and celebrities, like K-Pop’s influence on global music and fashion trends.

- High Culture : Artifacts and activities considered ‘refined’ or ‘sophisticated’ by elite society, such as opera and ballet in European cultures (Bourdieu, 2010). This is contrasted to low culture , which represents the culture of the working-class.

- Material Culture : Tangible artifacts of human society like architecture, fashion, or food. The medieval castles peppered throughout France offer insight into its material culture. This is of great concern, for example, to archaeologists.

- Non-Material Culture : Intangible aspects of a culture, such as values and norms. The continued emphasis on politeness in British culture is an example of this. This is of great concern, for example, to sociocultural anthropologists.

- Professional Culture: Standards and behaviors specific to a particular profession. The Hippocratic Oath and an emphasis on patient care are integral to medical culture.

- Organizational Culture: Refers to the shared values, beliefs, and behaviors that form the unique social and psychological environment of an organization. Google’s culture of innovation and employee freedom reflects this.

For More, Read: 17 Types of Culture

Theoretical Approaches to Culture in Sociology

Sociologists have come up with various theories of culture, explaining why and how they exist.

1. Functionalism

Functionalism sees society as a group of elements that function together to maintain a stable whole.

Émile Durkheim, one of the founders of sociology, used an organic analogy to explain this. In a biological creature, all the constituent body parts work together to maintain an organic whole; in the same way, the parts of a society work together to ensure its stability.

Under such a view, culture is something that helps society to exist as a stable entity: cultural norms, for example, guide people’s behavior and ensure that they appropriately. Talcott Parsons said that culture performs “latent pattern maintenance”, meaning that it maintains social patterns of behavior and allows orderly change (Little).

To put it in one sentence, culture ensures that our “way of life” remains stable. Functionalism can provide excellent insights into all cultural expressions, even ones that seem quite irrational. For example, sports in themselves may seem quite “useless”.

What exactly is the point of trying to hit a ball far or kicking one into a net? Functionalists would explain that sports brings people together and creates a collective experience. It provides an outlet for aggressive energies, teaches us the value of teamwork, and of course, makes us physically fit.

Real culture allows a given society to see how far its aspirations lie from its achievements, allowing it to take redressal steps.

Read More about Functionalism in Sociology Here

2. Conflict Theory

Conflict theory focuses on the power relations that exist in society and believes that culture is entrenched in this power play.

These sociologists emphasize the unequal nature of social structures, and how they are related to factors of class, race, gender, etc. For them, culture is another tool for reinforcing and perpetuating these differences.

A key focus of conflict theory is on critiquing “ideology”, which is seen as a set of ideas that support or conceal the existing power relations in society. For example, as we discussed earlier, one of the key beliefs in the United States is the “American Dream”: anyone can work hard to achieve success.

But this belief hardly takes into account larger social factors (historical oppression, generational wealth, etc.). For a white, middle-class man, it may certainly be possible to work hard and achieve incredible success. But for a poor black woman, the American dream is mostly a myth.

Case Study: Conflict Theory and Culture

Conflict Theorists (and some functionalists) argue that there are two types of culture: ideal and real. The ideal culture is the culture that society strives toward – it’s the standard that maintains a goal of society. This is contrasted to real culture , which sociologist Max Weber says is the real-life manifestation of culture. This includes the elements of oppression and inequalities, which ideal culture does not consider. For example, if ideal culture talks about democracy, real culture points out how politics is biased toward privileged people.

3. Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism focuses on face-to-face interactions of individuals and sees culture as an outcome of these.

Such sociologists believe that human interactions are a continuous process of finding meaning from the actions of others and the objects in the environment (Little). All these actions & objects have a “symbolic meaning”.

Culture is how this symbolic meaning is shared and interpreted. Symbolic interactions also believe that our social world is quite dynamic: instead of obsessing over rigid structures, they emphasize how situations and meanings are constantly changing.

For a symbolic interactionist, something as simple as a t-shirt communicates a symbolic meaning. They would argue that clothes do not simply play a “functional” role (protection) but also express something about the wearer.

See Also: Examples of Symbolic Interactionism

Culture includes the values, practices, and artifacts of a group of people; it is our shared “way of life”.

Most human behavior —from what we eat at breakfast to when we go back to sleep—is socially acquired through culture. It gives us a shared sense of “meaning” and guides human behavior, helping to maintain a stable society. However, it is also entrenched in power relations and can both enforce/challenge those relations.

Little, William. (2016). Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition . OpenEd.

Murdock, George P. (1949). Social Structure . Macmillan.

Scott, Taylor. (2014). A Dictionary of Sociology. Oxford.

Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive culture: Researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art, and custom. J. Murray.

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Indirect Democracy: Definition and Examples

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Pluralism (Sociology): Definition and Examples

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Equality Examples

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Instrumental Learning: Definition and Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Sociology 101

This lesson introduces how sociologists think about culture. Culture is one of the fundamental elements of social life and, thus, an essential topic in sociology. Many of the concepts presented here will come up again in almost every subsequent lesson. Because culture is learned so slowly and incrementally, we are often unaware of how it becomes ingrained in our ways of thinking. Applying the sociological perspective to culture requires us to recognize the strangeness in our own culture. This lesson outlines the basics of studying culture and allows you to test potential relationships between television depictions of families and marriage rates. Although culture is familiar to us, you should be seeing it in a new and different way by the time you finish this lesson.

Learning Objectives ¶

By the end of this lesson, you will be able to:

Describe how sociologists define the components of culture.

Identify variation in culture and cultural change.

Analyze the relationship between culture and family.

Deadlines ¶

Be sure to hand these in before the deadline

Inquizitive Chapter 3 (Thursday at 9:30am)

Obesity case study (Sunday at 10:00pm)

Disclosure reflection (Sunday at 10:00pm)

Class Lecture Recorded 2/9. Slides

Cultures, Subcultures, & Countercultures

Symbols, Values, & Norms

Discuss (Thursday during class): ¶

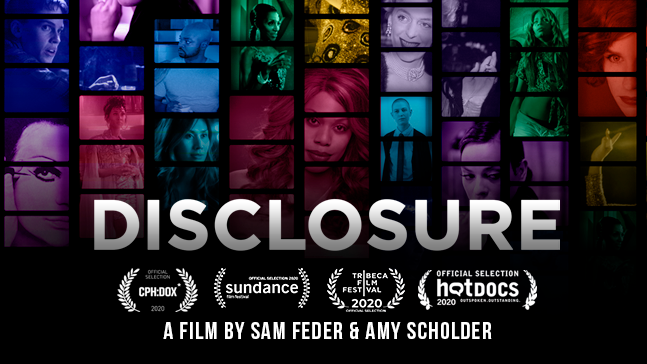

Disclosure ¶.

is an unprecedented, eye-opening look at transgender depictions in film and television, revealing how Hollywood simultaneously reflects and manufactures our deepest anxieties about gender. Leading trans thinkers and creatives, including Laverne Cox, Lilly Wachowski, Yance Ford, Mj Rodriguez, Jamie Clayton, and Chaz Bono, share their reactions and resistance to some of Hollywood’s most beloved moments. Grappling with films like A Florida Enchantment (1914), Dog Day Afternoon, The Crying Game, and Boys Don’t Cry, and with shows like The Jeffersons, The L-Word, and Pose, they trace a history that is at once dehumanizing, yet also evolving, complex, and sometimes humorous. What emerges is a fascinating story of dynamic interplay between trans representation on screen, society’s beliefs, and the reality of trans lives. Reframing familiar scenes and iconic characters in a new light, director Sam Feder invites viewers to confront unexamined assumptions, and shows how what once captured the American imagination now elicit new feelings. Disclosure provokes a startling revolution in how we see and understand trans people.. Official Description

We will be applying our sociological tools to the film Disclosure on Netflix. We will watch it together starting Thursday during class.

Be sure to have the movie ready to roll at the start of class.

Login to the course Slack at 9:30am and say hi to your group!

Case Study: Obesity ¶

In this assignment, you will read about a sociological study that examined whether obesity spreads like a contagion through social networks. You will then be asked five questions about the research. These case studies help you develop your ability to understand and evaluate social science research and make connections between research and our theoretical toolkit.

Note: Once you start, you only have 30 minutes to complete this assignment. Students with ARS accomodations may have additional time.

You can find the case study on Sakai under Tests and Quizzes. It is only available during this lesson week.

Questions ¶

If you have any questions at all about what you are supposed to do on this assignment, please remember I am here to help. Reach out any time so I can support your success.

Post it in the Slack #questions channel!

Signup for virtual office hours !

Email me or your TA.

Lesson Keywords ¶

ethnocentrism

cultural relativism

material culture

symbolic culture

Sapir-Whorf hypothesis

social control

Dominant culture

counterculture

ideal culture

real culture

cultural diffusion

cultural imperialism

The least you need to know ¶

Theoretical perspectives and culture

Extra Resources ¶

Teaching videos ¶.

Overview of culture (Khan Academy)

Culture and society (Khan Academy)

Subculture vs counterculture (Khan Academy)

Culture lag and culture shock (Khan Academy)

Diffusion (Khan Academy)

What is normal? Exploring folkways, mores, and taboos (Khan Academy)

Other Resources ¶

To Code Switch or Not to Code Switch? (8 minute TEDx Talk by Katelynn Duggins)

Tropes vs. Women in Video Games (Anita Sarkeesian’s series of video essays on gender and the gamer community)

The Story of Stuff (Annie Leonard on where our stuff comes from.]

Sociology, Cultural Studies and the Cultural Turn

Cite this chapter.

- Gregor McLennan

896 Accesses

2 Citations

For 40 years, the relationship between sociology and cultural studies has posed central questions of self-definition and practice for both projects. By orchestrating a range of manifesto-style statements — the full literature can only be gestured towards — this chapter offers an analytical profile of the unfolding dealings between the two formations, starting with the prevailing discourse around sociology at the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) in the 1970s (‘Birmingham’). The second sketch — ‘postmodern con-juncturalism’ — takes as background the worldwide growth of cultural studies as an undergraduate quasi-discipline, involving the active displacement of disciplinary sociology. In a third movement —‘sociological readjustment’ — the tables are ostensibly turned once again, but at this point the whole notion of the ‘cultural turn’, which rhetorically governs most of the debate, requires critical focus. In the years after 2000, a mood of ‘pragmatic reflexivity’ emerges in cultural studies and sociology alike, in which, despite latent tensions, various balances are struck between culture and economy, theory and method, political purpose and academic professionalism. With these developments, the prospect of a more principled partnership between the ‘warring twins’ (D. Inglis, 2007) could be glimpsed. However, several recent currents of thought and research are undermining the ‘culture and society’ problematic that has sustained most versions of the sociology-cultural studies encounter.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cultural Sociology in Scandinavia

The “Cultural Turn” and the Changing Face of the Humanities in Poland

Bibliography.

Abell, P. and Reyniers, D. (2000) ‘On the Failure of Social Theory’, British Journal of Sociology 51(4): 739–50.

Article Google Scholar

Abrams, P.; Deem, R.; Finch, J. and Rock, P. (1981) Practice and Progress: British Sociology1950–1980 . London: Allen & Unwin.

Google Scholar

Adkins, L. (2004a) ‘Introduction: Feminism, Bourdieu and After’, in L. Adkins and B. Skeggs (eds), Feminism After Bourdieu . Oxford: Blackwell.

Adkins, L. (2004b) ‘Gender and the Poststructural Social’, in B. Marshall and A. Witz (eds), Engendering the Social: Feminist Encounters with Sociological Theory . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Agger, B. (1992) Cultural Studies as Critical Theory . London: Falmer Press.

Alasuutari, P. (1995) Researching Culture: Qualitative Method and Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Alexander, J.C. (1988a) ‘The New Theoretical Movement’, in N. Smelser (ed.), Handbook of Sociology . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Alexander, J.C. (1988b) ‘Durkheimian Sociology and Cultural Studies Today’, in J.C. Alexander, Structure and Meaning: Relinking Classical Sociology . New York: Columbia University Press.

Alexander, J.C. (2003) The Meanings of Social Life: A Cultural Sociology . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Alexander, J.C. and Thompson, K. (2008) a Contemporary Introduction to Sociology: Culture and Society in Transition . Boulder, CO, and London: Paradigm.

Anderson, P. (1969) ‘Components of the National Culture’, in A. Cockburn (ed.), Student Power . Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Back, L.; Bennett, A.; Edles, L.D.; Gibson, M.; Inglis, D.; Jacobs, R. and Woodward, I. (2012) Cultural Sociology: An Introduction . Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Baetens, J. (2005) ‘Cultural Studies after the Cultural Studies Paradigm’, Cultural Studies 19(1): 1–13.

Baldwin, E.; Longhurst, B.; McCracken, S.; Ogburn, M. and Smith, G. (2004) Introducing Cultural Studies , 2nd edition. London: Prentice Hall.

Barker, C. (2003) Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice , 2nd edition. London: Sage.

Barrett, M.; Corrigan, P.; Kuhn, A. and Wolff, J. (1979) Ideology and Cultural Production , London: Croom Helm/BSA.

Barrett, M. (1980). Women’s Oppression Today: Problems in Marxist-Feminist Analysis . London: Verso.

Barrett, M. (1991) The Politics of Truth: From Marx to Foucault . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Barrett, M. (1992) ‘Words and Things: Materialism and Method in Contemporary Feminist Theory’, in M. Barrett and A. Phillips, Destabilising Theory: Contemporary Feminist Debates . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Barrett, M. (1999) Imagination in Theory: Essays on Writing and Culture . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Barrett, M. (2000) ‘Sociology and the Metaphorical Tiger’, in P. Gilroy, L. Grossberg and A. McRobbie (eds), Without Guarantees: In Honour of Stuart Hall. London: Verso.

Belghazi, T. (1995) ‘Cultural Studies, the University and the Question of Borders’, in B. Adam and S. Allan (eds), Theorizing Culture: An Interdisciplinary Critique After Postmodernism . London: UCL Press.

Bennett, T. (1998) Culture: a Reformer’s Science . London: Sage.

Bland, L.; Brunsdon, C.; Hobson, D. and Winship, J. (1978a) ‘Women “Inside and Outside” the Relations of Production’, in Women’s Studies Group CCCS, Women Take Issue: Aspects of Women’s Subordination . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Bland, L.; Harrison, R.; Mort, F. and Weedon, C. (1978b) ‘Relations of Reproduction: Approaches through Anthropology’, in Women’s Studies Group CCCS, Women Take Issue: Aspects of Women’s Subordination . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Bonnell, V.E. and Hunt, L. (eds) (1999) Beyond the Cultural Turn . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bourdieu, P. and Wacquant, L. (1999) ‘On the Cunning of Imperial Reason’, Theory, Culture & Society , 16(1): 41–58.

Bradley, H. and Fenton, S. (1999). ‘Reconciling Culture and Economy: Ways Forward in the Analysis of Ethnicity and Gender’, in L. Ray and A. Sayer (eds), Culture and Economy After the Cultural Turn . London: Sage.

Brantlinger, P. (1990) Crusoe’s Footprints: Cultural Studies in Britain and America . London: Routledge.

Brook, E. and Finn, D. (1978) ‘Working Class Images of Society and Community Studies’, in On Ideology . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Butters, S. (1976) ‘The Logic of Enquiry of Participant Observation: A Critical Review’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

Candea, M. (ed.) (2010) The Social After Gabriel Tarde: Debates and Assessments . London: Routledge.

CCCS (1973) ‘Literature/Society: Mapping the Field’, in Culture Studies 4 Literature-Society . Birmingham: CCCS.

CCCS (1981) Unpopular Education: Schooling and Social Democracy in England since 1944 . London: Hutchinson.

Chaney, D. (1994) The Cultural Turn: Scene Setting Essays on Contemporary Cultural History . London: Routledge.

Clarke, J.; Hall, S.; Jefferson, T. and Roberts, B. (1976) ‘Subcultures, Cultures and Class’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

Couldry, N. (2000) Inside Culture: Re-Imagining the Method of Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Crane, D. (1994) ‘Introduction: The Challenge of the Sociology of Culture to Sociology as a Discipline’, in D. Crane (ed.), The Sociology of Culture: Emerging Theoretical Perspectives . Oxford: Blackwell.

Critcher, C. (1979) ‘Sociology, Cultural Studies and the Post-War Working Class’, in J. Clarke, C. Critcher and R. Johnson (eds), Working Class Culture: Studies in History and Theory . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Crompton, R. and Scott, J. (2005) ‘Class Analysis: Beyond the Cultural Turn’, in F. Devine, M. Savage, J. Scott and R. Crompton (eds), Rethinking Class: Cultures, Identities and Lifestyles . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Denzin, N.K. (1992) Symbolic Interactionism and Cultural Studies: The Problem of Interpretation . Oxford: Blackwell.

Devine, F. and Savage, M. (2005) ‘The Cultural Turn, Sociology and Class Analysis’, in F. Devine, M. Savage, J. Scott and R. Crompton (eds), Rethinking Class: Cultures, Identities and Lifestyles . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

du Gay, P. (1997) ‘Introduction’, >in P. du Gay et al. (eds), Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman . London: Sage/Open University.

du Gay, P. and Pryke, M. (2002) ‘Cultural Economy: An Introduction’, in P. du Gay and M. Pryke (eds), Cultural Economy . London: Sage.

During, S. (1993) ‘Introduction’, The Cultural Studies Reader . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

During, S. (2005) Cultural Studies: A Critical Introduction . London: Routledge.

Editorial Group (1978) ‘Women’s Studies Group: Trying to do Feminist Intellectual Work’, in Women’s Studies Group CCCS, Women Take Issue: Aspects of Women’s Subordination . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Elliott, A. (ed.) (1999) The Blackwell Reader in Contemporary Social Theory . Oxford: Blackwell.

Elliott, A. (2009) Contemporary Social Theory: An Introduction . London: Routledge.

Evans, M. (2003) Gender and Social Theory . Buckingham, Open University Press.

Ferguson, M. and Golding, P. (eds) (1997) Cultural Studies in Question . London: Sage.

Fraser, N. (2000) ‘Rethinking Recognition’, New Left Review 3: 107–20.

Fulcher, J. and Scott, J. (2004) Sociology , 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gilroy, P. (1982) ‘Steppin’ Out of Babylon - Race, Class and Autonomy’, in CCCS, The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Gray, A. (2003) Research Practice for Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Goldthorpe, J.H. (2004) ‘Book Review Symposium: The Scientific Study of Society’, British Journal of Sociology 55(1): 123–6.

Grossberg, L. (1993) ‘The Formation of Cultural Studies: An American in Birmingham’, in V. Blundell, J. Shepherd and I. Taylor (eds), Relocating Cultural Studies: Developments in Theory and Research . London: Routledge.

Hall, S.; Critcher, C.; Clarke, J.; Jefferson, T. and Roberts, B. (1977) Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order . London: Macmillan.

Hall, S. (1978) ‘The Hinterland of Science: Ideology and the Sociology of Knowledge’, in CCCS, On Ideology . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Hall, S. (1980). ‘Cultural Studies and the Centre: Some Problematics and Problems’, in S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe and P. Willis (eds), Culture, Media, Language . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Hall, S. (1988) The Hard Road to Renewal: Thatcherism and the Crisis of the Left . London: Verso.

Hall, S. (1992a) ‘Cultural Studies and its Theoretical Legacies’, in L. Grossberg, C. Nelson and P.A. Treichler (eds), Cultural Studies . New York: Routledge.

Hall, S. (1992b) ‘New Ethnicities’, in J. Donald and A. Rattansi (eds), Race, Culture and Difference . London: Sage.

Hall, S. (1992c) ‘The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power’, in S. Hall and B. Gieben (eds), Formations of Modernity . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hall, S. (1996a) ‘On Postmodernism and Articulation’, in D. Morley and K.H. Chen (eds), Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies . London: Routledge.

Hall, S. (1996b) ‘When was “the Post-colonial”? Thinking at the Limit’, in L. Curti, and I. Chambers (eds), The Post-Colonial Question: Common Skies, Divided Horizons . London: Routledge.

Hall S. (1997a) ‘Introduction’, in S. Hall (ed.), Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices . London: Sage/Open University.

Hall, S. (1997b) ‘The Centrality of Culture: Notes on the Cultural Revolutions of Our Time’, in K. Thompson (ed.), Media and Cultural Regulation . London: Sage/Open University.

Hall, S. (2000) ‘Conclusion: The Multi-Cultural Question’, in B. Hesse (ed.), Un/settled Multiculturalisms . London: Zed Press.

Harris, D. (1992) From Class Struggle to the Politics of Pleasure . London: Routledge.

Hicks, D. (2010) ‘The Material-Cultural Turn: Event and Effect’, in D. Hicks and M.C. Beaudry (eds), Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hicks, D. and Beaudry, M.C. (2010) ‘Introduction’, in D. Hicks and M.C. Beaudry (eds), Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Inglis, D. (2007) ‘The Warring Twins: Sociology, Cultural Studies, Alterity and Sameness’, History of the Human Sciences 20(2): 99–122.

Inglis, F. (2004) Culture . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Jessop, B. and Oosterlynck, S. (2008) ‘Cultural Political Economy: On Making the Cultural Turn without falling into soft economic sociology’, Geoforum 39(3): 1155–69.

Johnson, R. (1997) ‘Reinventing Cultural Studies: Remembering for the Best Version’, in E. Long (ed.), From Sociology to Cultural Studies . Oxford: Blackwell.

Johnson, R.; Chambers, D.; Raghuram, P. and Ticknell, E. (2004) The Practice of Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Joyce, P. (ed.) (2002) The Social in Question: New Bearings in History and the Social Sciences . London: Routledge.

Jutel, T. (2004) ‘Lord of the Rings: Landscape, Transformation, and the Geography of the Virtual’, in C. Bell and S. Mathewman (eds), Cultural Studies in Aotearoa New Zealand . Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Kellner, D. (1995) Media Culture: Cultural Studies, Identity, and Politics between the Modern and the Postmodern . London: Routledge.

Lash, S. (2010) Intensive Culture: Social Theory, Religion and Contemporary Capitalism . London: Sage.

Latour, B. (2002) ‘Gabriel Tarde and the End of the Social’, in P. Joyce (ed.), The Social in Question: New Bearings in History and the Social Sciences . London: Routledge.

Latour, B. (2005) Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to ANT . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Law, J. (1999) ‘After ANT: Complexity, Naming and Topology’, in J. Law and J. Hassard (eds), ANT and After . Oxford: Blackwell.

Law, J. (2002) ‘Economics as Interference’, in P. du Gay and M. Pryke (eds), Cultural Economy . London: Sage.

Lawrence, E. (1982) ‘In the Abundance of Water the Fool is Thirsty: Sociology and Black “Pathology”’, in CCCS, The Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain. London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Lewis, J. (2003) Cultural Studies: The Basics . London: Sage.

Macionis, J.J. and Plummer, K. (2005) Sociology: A Global Introduction , 3rd edition. Harlow: Pearson Prentice Hall.

McGuigan, J. (1992) Cultural Populism . London: Routledge.

McGuigan, J. (2009) Cool Capitalism . London: Pluto Press.

McLennan, G. (2005) ‘The New American Cultural Sociology: An Appraisal’, Theory, Culture & Society 22(6): 1–18.

McLennan, G. (2006) Sociological Cultural Studies: Reflexivity and Positivity in the Human Sciences . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

McLennan, G. (2013) ‘Postcolonial Critique: The Necessity of Sociology’, Political Power and Social Theory 24: 119–44.

McNay, L. (2004a) ‘Agency and Experience: Gender as a Lived Relation’, in L. Adkins and B. Skeggs (eds), Feminism After Bourdieu . Oxford: Blackwell.

McNay, L. (2004b) ‘Situated Intersubjectivity’, in B. Marshall and A. Witz (eds), Engendering the Social: Feminist Encounters with Sociological Theory . Buckingham: Open University Press.

McRobbie, A. and Garber, J. (1976) ‘Girls and Subcultures: An Exploration’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

McRobbie, A. (1997) Back to Reality? Social Experience and Cultural Studies . Manchester: Manchester University Press.

McRobbie, A. (2005) The Uses of Cultural Studies . London: Sage.

Morley, D. (1997). ‘Theoretical Orthodoxies: Textualism, Constructivism and the “New Ethnography” in Cultural Studies’, in M. Ferguson and P. Golding (eds), Cultural Studies in Question . London: Sage.

Morley, D. (2000) ‘Cultural Studies and Common Sense’, in P. Gilroy, L. Grossberg and A. McRobbie (eds), Without Guarantees: In Honour of Stuart Hall. London: Verso.

Morley, D., and Robins, K. (eds) (2001) British Cultural Studies . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mulhern, F. (2000) Culture/Metaculture . London: Routledge.

Osborne, T. (2008) The Structure of Modem Cultural Theory . Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Osborne, T.; Rose, N. and Savage, M. (2008) ‘Reinscribing British Sociology’, Sociological Review 56(4): 519–34.

Pearson, G. and Twohig, J. (1976) ‘Ethnography Through the Looking Glass: the Case of Howard Becker’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

Pickering, A. (ed.) (1992) Science as Practice and Culture . Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Ray, L. (2003) ‘Foreword’, in B. Smart, Economy, Culture and Society: A Sociological Critique of Neo-liberalism . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Ray, L. and Sayer, A. (eds) (1999) Culture and Economy After the Cultural Turn . London: Sage.

Reed, I. and Alexander, J.C. (eds) (2009) Meaning and Method: the Cultural Approach to Sociology . Boulder, CO, and London: Paradigm.

Roberts, B. (1976) ‘Naturalistic Research into Subcultures and Deviance: An Account of a Sociological Tendency’, in S. Hall and T. Jefferson (eds), Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain . London: CCCS/ Unwin Hyman.

Rojek, C. (1985) Capitalism and Leisure Theory . London: Tavistock.

Rojek, C. (1992) ‘The Field of Play in Sport and Leisure Studies’, in E. Dunning and C. Rojek (eds), Sport and Leisure in the Civilizing Process: Critique and Counter-Critique . Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Rojek, C. and Turner, B. (2000) ‘Decorative Sociology: Towards a Critique of the Cultural Turn’, Sociological Review 48(4): 629–48.

Rojek, C. (2003) Stuart Hall . Cambridge: Polity Press.

Roseneil, S. and Frosh, S. (eds) (2012) Social Research After the Cultural Turn . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Savage, M. (2012) ‘The Politics of Method and the Challenge of Digital Data’, in S. Roseneil and S. Frosh (eds), Social Research After the Cultural Turn . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sayer, A. (2005) The Moral Significance of Class . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schwarz, B. (2005) Review of Rojek, ‘Stuart Hall’, Cultural Studies 19(2): 176–202.

Skeggs, B. (2004) Class, Self, Culture . London: Routledge.

Skeggs, B. (2005) ‘The Re-branding of Class: Propertizing Culture’, in F. Devine, M. Savage, J. Scott and R. Crompton (eds), Rethinking Class: Cultures, Identities and Lifestyles . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Silva, E. and Warde, A. (eds) (2010). Cultural Analysis and Bourdieu’s Legacy: Settling Accounts and Developing Alternatives . London: Routledge.

Smart, B. (2003) Economy, Culture and Society: A Sociological Critique of Neo-Liberalism . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Smelser, N. (1992) ‘Culture: Coherent or Incoherent?’, in R. Munch and N.J. Smelser (eds), Theory of Culture . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Smith, Paul (2000) ‘Looking Backwards and Forwards at Cultural Studies’, in T. Bewes and J. Gilbert (eds), Cultural Capitalism: Politics After New Labour . London: Lawrence & Wishart.

Storey, J. (2001) Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: An Introduction . Harlow: Prentice Hall.

Stratton, J. and Ang, I. (1996). ‘On the Impossibility of a Global Cultural Studies’, in D. Morley and K.H. Chen (eds), Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies . London: Routledge.

Tester, K. (1994) Media, Culture and Morality . London: Routledge.

Thrift, N. (2005) Knowing Capitalism . London: Sage.

Thrift, N. (2008) Non-representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect . London: Routledge.

Tomlinson, J. (2012) ‘Cultural Analysis’, G. in Ritzer (ed.), Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Sociology . London: John Wiley.

Turner, B.S. and Rojek, C. (2001) Society and Culture: Principles of Scarcity and Solidarity . London: Sage.

Turner, G. (1990) British Cultural Studies . Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman.

White, M. and Schwoch, J. (2006) ‘Introduction’, in M. White and J. Schwoch (eds), Questions of Method in Cultural Studies . Oxford: Blackwell.

Willis, P. (1977) Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids get Working Class Jobs . Farnborough: Saxon House.

Willis, P. (1980) ‘Notes on Method’, in S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe and P. Willis (eds), Culture, Media, Language . London: CCCS/Hutchinson.

Willis, P. (2003) ‘Introduction’, in C. Barker, Cultural Studies: Theoty and Practice , 2nd edition. London: Sage.

Witz, A. and Marshall, B.L. (2004) ‘The Masculinity of the Social: Towards a Politics of Interrogation’, in B.L. Marshall and A. Witz (eds), Engendering the Social . Buckingham: Open University Press.

Wolff, J. (1999) ‘Cultural Studies and the Sociology of Culture’, Contemporary Sociology 28(5): 499–507.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Nottingham, UK

John Holmwood

University of Copenhagen, Denmark

Copyright information

© 2014 Gregor McLennan

About this chapter

McLennan, G. (2014). Sociology, Cultural Studies and the Cultural Turn. In: Holmwood, J., Scott, J. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Sociology in Britain. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137318862_23

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137318862_23

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-33548-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-31886-2

eBook Packages : Palgrave Social Sciences Collection Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An essay on culture

- Política & Sociedade 20(49):134-162

- 20(49):134-162

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- THOMAS KUHN

- Bronislaw Malinowski

- John Levi Martin

- Alessandra Lembo

- Michael Warner

- Pierre Bourdieu

- Richard Nice

- Stephan Fuchs

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- DOI: 10.4324/9780203205594

- Corpus ID: 144810099

Essays on the Sociology of Culture

- K. Mannheim

- Published 1992

102 Citations

The sociology of knowledge: a preliminary analysis on the sociological approach to the development of islamic religious scıences, criticism of marxism as a proto-theory of cultural capital and the “new class”: j. w. machajski’s theory of intelligentsia, the new sociology, from political to social generations, authoritative knowledge and heteronomy in classical sociological theory*, reflections on the theatrical nature of a human being: suggestion and its hidden potential, from political to social generations: a critical reappraisal of mannheim’s classical approach, remarks on technology and culture, the protestant ethic and the spirit of political power: sociopolitical conditions underlying the development of calvinism, on the civilising of objectification. language use, discursive patterns and the psychological expertise of work planning, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Essays on the Sociology of Culture

Karl mannheim , bryan s. turner ( foreword ) , professor bryan s turner ( foreword ).

First published January 1, 1956

About the author

Karl Mannheim

Ratings & reviews.

What do you think? Rate this book Write a Review

Friends & Following

Community reviews, join the discussion, can't find what you're looking for.

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Sociological Imagination

Essays on Sociological Imagination

Sociological imagination essay topic examples, argumentative essays.

Argumentative sociological imagination essays require you to present and defend a viewpoint on a sociological issue or concept. Consider these topic examples:

- 1. Argue for or against the idea that social media has transformed the way we form and maintain relationships, considering its impact on social interactions and personal identity.

- 2. Defend your perspective on the role of economic inequality in shaping opportunities and life outcomes, and discuss potential solutions to address this issue.

Example Introduction Paragraph for an Argumentative Sociological Imagination Essay: The sociological imagination allows us to examine how individual experiences are intertwined with larger societal forces. In this essay, I will argue that the rise of social media has redefined our notions of friendship and identity, fundamentally altering the way we connect and interact with others.

Example Conclusion Paragraph for an Argumentative Sociological Imagination Essay: In conclusion, our sociological examination of the impact of social media on relationships highlights the need for a nuanced understanding of modern social interactions. As we navigate this evolving landscape, we must consider the profound influence of technology on our lives.

Compare and Contrast Essays

Compare and contrast sociological imagination essays involve analyzing the differences and similarities between sociological concepts, theories, or societal phenomena. Consider these topics:

- 1. Compare and contrast the perspectives of functionalism and conflict theory in explaining the role of education in society, emphasizing their views on social inequality and the education system.

- 2. Analyze the differences and similarities between rural and urban communities in terms of social structure, opportunities, and challenges, highlighting the impact of location on individuals' lives.

Example Introduction Paragraph for a Compare and Contrast Sociological Imagination Essay: Sociological theories provide diverse lenses through which we can analyze and understand society. In this essay, we will compare and contrast the perspectives of functionalism and conflict theory in their explanations of the role of education in shaping social inequalities and the education system.

Example Conclusion Paragraph for a Compare and Contrast Sociological Imagination Essay: In conclusion, the comparison and contrast of functionalism and conflict theory underscore the complexity of educational systems and their implications for social inequality. As we delve into these theories, we are reminded of the multifaceted nature of sociological analysis.

Descriptive Essays

The sociological imagination prompts us to explore the complex interactions within society and culture. For those looking to deepen their analysis and needing support to craft thorough and insightful examinations, there are specialized services available. Read about the best websites where you can do your homework with the help of experts, ensuring academic success as you navigate these intricate topics.

Descriptive essays on sociological imagination allow you to provide in-depth accounts and analyses of societal phenomena, social issues, or individual experiences. Here are some topic ideas:

- 1. Describe the impact of globalization on cultural diversity, exploring how it has shaped the cultural landscape and individuals' sense of identity.

- 2. Paint a vivid picture of the challenges faced by immigrant communities in adapting to a new cultural and social environment, emphasizing their experiences and resilience.

Example Introduction Paragraph for a Descriptive Sociological Imagination Essay: The sociological imagination encourages us to delve into the intricate dynamics of society and culture. In this essay, I will immerse you in the transformative effects of globalization on cultural diversity, examining how it has redefined our identities and cultural experiences.

Example Conclusion Paragraph for a Descriptive Sociological Imagination Essay: In conclusion, the descriptive exploration of the impact of globalization on cultural diversity reveals the interconnectedness of our world and the evolving nature of cultural identities. As we navigate this globalized society, we are challenged to embrace diversity and promote intercultural understanding.

Persuasive Essays

Persuasive sociological imagination essays involve convincing your audience of the significance of a sociological issue, theory, or perspective, and advocating for a particular viewpoint or action. Consider these persuasive topics:

- 1. Persuade your readers of the importance of gender equality in the workplace, emphasizing the societal benefits of promoting diversity and inclusion.

- 2. Argue for the integration of sociological education into school curricula, highlighting the value of fostering sociological thinking skills for informed citizenship.

Example Introduction Paragraph for a Persuasive Sociological Imagination Essay: Sociological insights have the power to shape our understanding of pressing issues. In this persuasive essay, I will make a compelling case for the significance of promoting gender equality in the workplace, underscoring its positive effects on society as a whole.

Example Conclusion Paragraph for a Persuasive Sociological Imagination Essay: In conclusion, the persuasive argument for gender equality in the workplace highlights the broader societal benefits of creating inclusive and diverse environments. As we advocate for change, we are reminded of the transformative potential of sociological perspectives in addressing contemporary challenges.

Narrative Essays

Narrative sociological imagination essays allow you to share personal stories, experiences, or observations related to sociological concepts, theories, or societal phenomena. Explore these narrative essay topics:

- 1. Narrate a personal experience of cultural adaptation or encountering cultural diversity, reflecting on how it has shaped your perspectives and understanding of society.

- 2. Share a story of social activism or involvement in a community project aimed at addressing a specific societal issue, highlighting the impact of collective action.

Example Introduction Paragraph for a Narrative Sociological Imagination Essay: The sociological imagination encourages us to explore our personal experiences within the broader context of society. In this narrative essay, I will take you through my personal journey of encountering cultural diversity and reflect on how it has influenced my worldview and understanding of society.

Example Conclusion Paragraph for a Narrative Sociological Imagination Essay: In conclusion, the narrative of my cultural adaptation experience underscores the transformative power of personal encounters with diversity. As we embrace the sociological imagination, we are reminded that our stories contribute to the broader narrative of societal change.

The Importance of Imagination in Movies

What is the sociological imagination and its examples, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Analysis of My Sociological Imagination

Sociological imagination, understanding the concept of sociological imagination by c. wright mills, examining our society using sociological imagination, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

A View of Society Through Sociological Imagination

Sociological imagination and how it is involved in our life, women’s feelings on body image through social imagination, sociological imagination between personal experience and the wider society, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Role of Sociological Imagination in Our Lives

Understanding today’s technology through social imagination, the influence of race and ethnicity on my life, personal troubles and public issues: sociological imagination, sociological imagination by charles wright mills, finding the true reasons for my love for sports through my sociological imagination, a discussion of statuses, roles and the sociological imagination, review of "the sociological imagination" by c. write mills, first impressions: judging someone without knowing them, the importance of sociological imagination for society improvement, how sociologists seek to understand the sporting world, the importance of sociological imagination in our personal problems, sociological imagination: interpretation of private concerns and public issues, the sociological imagination by c. wright mills: the collective dream, sociological imagination in relation to divorce, sociological imagination, structural, and functional theories, the difference between sociological imagination and common sense, overview of the role of social imagination in society, sociology quiz, research of the essence of 'thinking sociologically'.

The concept of sociological imagination involves the ability to step outside of our familiar daily routines and examine them from a fresh and critical perspective. It encourages us to think beyond the confines of our personal experiences and consider the broader social, cultural, and historical factors that shape our lives.

The phrase was introduced by C. Wright Mills, an American sociologist, in his 1959 publication "The Sociological Imagination." Mills used this term to describe the unique perspective and understanding that sociology provides. He emphasized the importance of looking beyond individual experiences and examining the larger social structures and historical contexts that shape our lives.

The roots of sociological imagination can be traced back to earlier sociological thinkers such as Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, and Max Weber, who emphasized the importance of understanding society as a whole and the impact of social structures on individuals. Throughout the years, sociological imagination has evolved and expanded, with various scholars and researchers contributing to its development. It has become a fundamental tool for sociologists to analyze social issues, explore the intersections of individual lives and societal structures, and understand the complexities of human behavior. Today, sociological imagination continues to be a crucial concept in sociology, empowering individuals to critically analyze the social world and recognize the larger societal forces that shape their lives.