Home ➔ Essay Structure ➔ Body Paragraphs ➔ Evidence in Essays

Guide to Evidence in an Essay

In essays, evidence can be presented in a number of ways. It might be data from a relevant study, quotes from a literary work or historical event, or even an anecdote that helps to illustrate your point. No matter what form it takes, evidence supports your thesis statement and major arguments.

Why is using evidence important? In academic writing, it is important to make a clear and well-supported argument. In order to do this, you need to use evidence to back up your claims. Provide evidence to show that you have done your research and that your arguments are based on facts, not just opinions.

What is evidence in academic writing?

In academic writing, evidence is often presented in the form of data from research studies or quotes from literary works. It can be used to support your argument or to illustrate a point you are making. Good evidence must be relevant, persuasive, and trustworthy.

Types of evidence

There are many different types of evidence that can be used in essays. Some common examples include:

Analogical: An analogy or comparison that supports your argument.

Example: “Like the human body, a car needs regular maintenance to function properly.”

This type is considered to be one of the weakest, as it is often based on opinion rather than fact. To use it well, you need to be sure that the analogy is relevant and that there are enough similarities between the two things you are comparing.

Anecdotal: A personal experience or story, your own research, or example that illustrates your point.

Example: “I know a woman who was fired from her job after she became pregnant.”

Anecdotal evidence is used to support a point or argument, but it should be used sparingly, as it is often considered to be less reliable than other types of evidence. It can also be used as a hook to engage the reader’s attention.

Hypothetical : A hypothetical situation or thought experiment that supports your argument.

Example: “If we do not take action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the Earth’s average temperature will continue to rise.”

This type of evidence can be useful in persuading readers to see your point of view. It is important to make sure that the hypothetical situation is realistic, as otherwise, it will undermine your argument. It is also not a strong form of evidence, and to make it work well, you will need to make the reader feel invested in the outcome.

Logical: A reasoning or argument that uses logic to support your claim.

Example: “The death penalty is a deterrent to crime because it removes the possibility of rehabilitation.”

This type is based on the idea that if something is true, then it must be the case that something else is also true. It is not the strongest type of evidence, as there are often other factors that can impact the validity of the argument.

Statistical: Data from research studies or surveys that support your argument.

Example: “According to a study by the American Medical Association, gun violence is the third leading cause of death in the United States.”

This type of evidence is often considered to be the most persuasive, as it is based on factual data. However, it is important to make sure that the data is from a reliable source and that it is interpreted correctly.

Testimonial: A quote from an expert or someone with first-hand experience that supports your argument.

Example: According to Dr. John Smith, a leading expert on the health effects of smoking, “Smoking is a major contributor to heart disease and lung cancer.”

This type of evidence can be very persuasive, as it uses the authority of an expert to support your argument. However, it is important to make sure that the expert is credible and that their opinion is relevant to your argument.

Textual: A quote from a literary work or historical document that supports your argument.

Example: “In the book ‘ To Kill a Mockingbird ,’ Atticus Finch says, ‘You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view.'”

This type of evidence can be used to support your argument, but it is important to make sure that the quote is relevant and that it is interpreted correctly.

Visual: A graph, chart, or image that supports your argument.

This evidence type might not be the most common in essays, but it can be very effective in persuading the reader to see your point of view. It is important to make sure that the visual is clear and easy to understand, as otherwise, it will not be as effective.

Types of evidence sources

When you want to find evidence to support your argument, it is important to consider the source. There are two major types of sources:

- Primary sources: These are first-hand accounts or data that has been collected by the author. Examples of such sources include research studies, surveys, and interviews.

- Secondary sources: These are second-hand accounts or data that has been collected by someone other than the author. Examples of such sources include books, articles, and websites.

For example, if you are writing an essay about George Orwell’s “1984,” a primary source would be the novel itself, while a secondary source would be an article about the author’s life.

As for which one is better or worse, it all depends on the context. In general, primary sources are more reliable, but they can be difficult to find or interpret. Secondary sources are easier to find, but they might not be as accurate.

But in general, these two types complement each other. In other words, you will likely need to use both primary and secondary sources to support your argument.

Incorporating evidence

There are different ways to introduce evidence effectively in your essay. The most common methods are:

- Direct Quotation: A direct quotation is when you reproduce the exact words of a source. This can be done by using quotation marks and citing the source in your paper .

- Paraphrasing: Paraphrasing is when you explain something in your own words. It’s a way of conveying the main idea of a text without simply repeating what the author has already said. When you paraphrase, you can use your own voice and style to communicate someone else’s words in a way that better suits your audience.

- Summarizing: Summarizing is when you provide a brief overview of a text. This can be done by identifying the main points and ideas in the text and conveying them in your own words.

- Factual data: Factual data is information that can be verified through research. This could include statistics, numbers, or other types of data that support your main argument.

How to use evidence in essays

Besides knowing what type of evidence to use, it is also important to know how to use it in the most effective way. Here are some steps that you can take to incorporate evidence in your paper.

1. Present your argument first

Before you start introducing evidence into your essay, it is important to first make a claim or thesis statement . This will give your paper direction and let your reader know what to expect.

On a paragraph level, your topic sentences are the arguments you are making. The rest of the paragraph should be used to support this claim with evidence.

Let’s say the topic of the essay is “The Impact of Social Media on Young People.”

Then, your thesis statement could be something like, “Social media has had a negative impact on the mental health of young people.”

And your first body paragraph might start with the following topic sentence: “The first way social media has had a negative impact on young people is by causing them to compare themselves to others.”

2. Introduce your evidence

Once you have presented your argument, you will need to introduce your evidence. This can be done by using a signal phrase or lead-in .

A signal phrase is a phrase that introduces the evidence you are about to provide. It can be used to introduce a direct quotation or paraphrase. For example:

- According to Dr. Smith,…

- Dr. Smith argues that…

- As Dr. Smith points out,…

- There is evidence to suggest that..

- The survey reveals that…

- As suggested by the study,…

Word Choice in Essays – read more about various words that you can use in your essay in different cases.

3. Present evidence

After you have introduced your evidence, you will need to state it clearly. This can be done by using a direct quotation, paraphrasing, or summarizing.

When using a direct quotation , you will need to use quotation marks and cite the source in your paper. For example:

As Dr. Smith points out, “Teenagers spend a lot of time on social media platforms observing the lives of others and comparing themselves to what they see, which can lead to damaged self-esteem and depression.”

When paraphrasing or summarizing , you will need to make sure that you are conveying the main points of the source using different words. For example:

Dr. Smith argues that social media can have a negative impact on young people’s mental health because it makes them compare themselves to others.

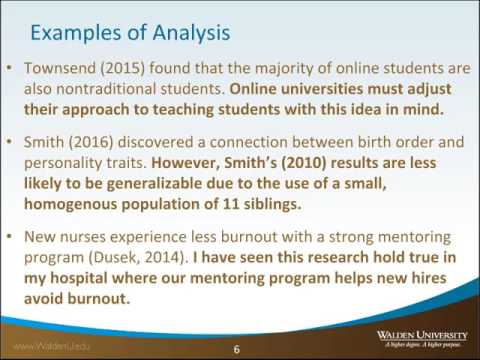

4. Comment on your evidence

After you have stated your supporting evidence, you will need to explain how it supports your argument. This can be done by providing your own analysis or interpretation.

For example:

By constantly comparing themselves to others, young people are more likely to develop a negative view of themselves. This can lead to mental health problems such as depression and low self-esteem.

5. Repeat for additional evidence

If you have more than one piece of evidence that supports your own argument, you will need to repeat steps 2-4 for each additional piece.

6. Link back to your key points

Once you have finished discussing your evidence, it is important to link back to your initial argument in the last sentence of your body paragraph and transition to the next paragraph .

Example of a full body paragraph with all the steps applied:

One way social media has had a negative impact on young people is by causing them to compare themselves to others. According to Dr. Smith, “Teenagers spend a lot of time on social media platforms observing the lives of others and comparing themselves to what they see, which can lead to depression and damaged self-esteem” (qtd. in Jones). By constantly comparing themselves to others, young people are more likely to develop a negative view of themselves. This can lead to mental health problems such as depression and low self-esteem. But this is not the only way social media can negatively affect young people’s mental health.

7. Wrap it up in a conclusion

Once you have finished all your body paragraphs, you will need to write a conclusion . This is where you will wrap up your argument and emphasize the main points that you have proven.

Remember, using evidence is just one part of the essay-writing process . You also need to make sure that your paper is well organized, has a clear structure , and is free of grammar and spelling errors. But if you can master the use of evidence, you will be well on your way to writing a strong essay.

Was this article helpful?

What this handout is about

This handout will provide a broad overview of gathering and using evidence. It will help you decide what counts as evidence, put evidence to work in your writing, and determine whether you have enough evidence. It will also offer links to additional resources.

Introduction

Many papers that you write in college will require you to make an argument ; this means that you must take a position on the subject you are discussing and support that position with evidence. It’s important that you use the right kind of evidence, that you use it effectively, and that you have an appropriate amount of it. If, for example, your philosophy professor didn’t like it that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in your ethics paper, you need to find out more about what philosophers count as good evidence. If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you’re “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” or asked you how certain points are related to your argument, it may mean that you can do more to fully incorporate your evidence into your argument. Comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand” in the margins of your graded paper suggest that you may need more evidence. Let’s take a look at each of these issues—understanding what counts as evidence, using evidence in your argument, and deciding whether you need more evidence.

What counts as evidence?

Before you begin gathering information for possible use as evidence in your argument, you need to be sure that you understand the purpose of your assignment. If you are working on a project for a class, look carefully at the assignment prompt. It may give you clues about what sorts of evidence you will need. Does the instructor mention any particular books you should use in writing your paper or the names of any authors who have written about your topic? How long should your paper be (longer works may require more, or more varied, evidence)? What themes or topics come up in the text of the prompt? Our handout on understanding writing assignments can help you interpret your assignment. It’s also a good idea to think over what has been said about the assignment in class and to talk with your instructor if you need clarification or guidance.

What matters to instructors?

Instructors in different academic fields expect different kinds of arguments and evidence—your chemistry paper might include graphs, charts, statistics, and other quantitative data as evidence, whereas your English paper might include passages from a novel, examples of recurring symbols, or discussions of characterization in the novel. Consider what kinds of sources and evidence you have seen in course readings and lectures. You may wish to see whether the Writing Center has a handout regarding the specific academic field you’re working in—for example, literature , sociology , or history .

What are primary and secondary sources?

A note on terminology: many researchers distinguish between primary and secondary sources of evidence (in this case, “primary” means “first” or “original,” not “most important”). Primary sources include original documents, photographs, interviews, and so forth. Secondary sources present information that has already been processed or interpreted by someone else. For example, if you are writing a paper about the movie “The Matrix,” the movie itself, an interview with the director, and production photos could serve as primary sources of evidence. A movie review from a magazine or a collection of essays about the film would be secondary sources. Depending on the context, the same item could be either a primary or a secondary source: if I am writing about people’s relationships with animals, a collection of stories about animals might be a secondary source; if I am writing about how editors gather diverse stories into collections, the same book might now function as a primary source.

Where can I find evidence?

Here are some examples of sources of information and tips about how to use them in gathering evidence. Ask your instructor if you aren’t sure whether a certain source would be appropriate for your paper.

Print and electronic sources

Books, journals, websites, newspapers, magazines, and documentary films are some of the most common sources of evidence for academic writing. Our handout on evaluating print sources will help you choose your print sources wisely, and the library has a tutorial on evaluating both print sources and websites. A librarian can help you find sources that are appropriate for the type of assignment you are completing. Just visit the reference desk at Davis or the Undergraduate Library or chat with a librarian online (the library’s IM screen name is undergradref).

Observation

Sometimes you can directly observe the thing you are interested in, by watching, listening to, touching, tasting, or smelling it. For example, if you were asked to write about Mozart’s music, you could listen to it; if your topic was how businesses attract traffic, you might go and look at window displays at the mall.

An interview is a good way to collect information that you can’t find through any other type of research. An interview can provide an expert’s opinion, biographical or first-hand experiences, and suggestions for further research.

Surveys allow you to find out some of what a group of people thinks about a topic. Designing an effective survey and interpreting the data you get can be challenging, so it’s a good idea to check with your instructor before creating or administering a survey.

Experiments

Experimental data serve as the primary form of scientific evidence. For scientific experiments, you should follow the specific guidelines of the discipline you are studying. For writing in other fields, more informal experiments might be acceptable as evidence. For example, if you want to prove that food choices in a cafeteria are affected by gender norms, you might ask classmates to undermine those norms on purpose and observe how others react. What would happen if a football player were eating dinner with his teammates and he brought a small salad and diet drink to the table, all the while murmuring about his waistline and wondering how many fat grams the salad dressing contained?

Personal experience

Using your own experiences can be a powerful way to appeal to your readers. You should, however, use personal experience only when it is appropriate to your topic, your writing goals, and your audience. Personal experience should not be your only form of evidence in most papers, and some disciplines frown on using personal experience at all. For example, a story about the microscope you received as a Christmas gift when you were nine years old is probably not applicable to your biology lab report.

Using evidence in an argument

Does evidence speak for itself.

Absolutely not. After you introduce evidence into your writing, you must say why and how this evidence supports your argument. In other words, you have to explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

As writers, we sometimes assume that our readers already know what we are talking about; we may be wary of elaborating too much because we think the point is obvious. But readers can’t read our minds: although they may be familiar with many of the ideas we are discussing, they don’t know what we are trying to do with those ideas unless we indicate it through explanations, organization, transitions, and so forth. Try to spell out the connections that you were making in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it. Remember, you can always cut prose from your paper later if you decide that you are stating the obvious.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself about a particular bit of evidence:

- OK, I’ve just stated this point, but so what? Why is it interesting? Why should anyone care?

- What does this information imply?

- What are the consequences of thinking this way or looking at a problem this way?

- I’ve just described what something is like or how I see it, but why is it like that?

- I’ve just said that something happens—so how does it happen? How does it come to be the way it is?

- Why is this information important? Why does it matter?

- How is this idea related to my thesis? What connections exist between them? Does it support my thesis? If so, how does it do that?

- Can I give an example to illustrate this point?

Answering these questions may help you explain how your evidence is related to your overall argument.

How can I incorporate evidence into my paper?

There are many ways to present your evidence. Often, your evidence will be included as text in the body of your paper, as a quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Sometimes you might include graphs, charts, or tables; excerpts from an interview; or photographs or illustrations with accompanying captions.

When you quote, you are reproducing another writer’s words exactly as they appear on the page. Here are some tips to help you decide when to use quotations:

- Quote if you can’t say it any better and the author’s words are particularly brilliant, witty, edgy, distinctive, a good illustration of a point you’re making, or otherwise interesting.

- Quote if you are using a particularly authoritative source and you need the author’s expertise to back up your point.

- Quote if you are analyzing diction, tone, or a writer’s use of a specific word or phrase.

- Quote if you are taking a position that relies on the reader’s understanding exactly what another writer says about the topic.

Be sure to introduce each quotation you use, and always cite your sources. See our handout on quotations for more details on when to quote and how to format quotations.

Like all pieces of evidence, a quotation can’t speak for itself. If you end a paragraph with a quotation, that may be a sign that you have neglected to discuss the importance of the quotation in terms of your argument. It’s important to avoid “plop quotations,” that is, quotations that are just dropped into your paper without any introduction, discussion, or follow-up.

Paraphrasing

When you paraphrase, you take a specific section of a text and put it into your own words. Putting it into your own words doesn’t mean just changing or rearranging a few of the author’s words: to paraphrase well and avoid plagiarism, try setting your source aside and restating the sentence or paragraph you have just read, as though you were describing it to another person. Paraphrasing is different than summary because a paraphrase focuses on a particular, fairly short bit of text (like a phrase, sentence, or paragraph). You’ll need to indicate when you are paraphrasing someone else’s text by citing your source correctly, just as you would with a quotation.

When might you want to paraphrase?

- Paraphrase when you want to introduce a writer’s position, but their original words aren’t special enough to quote.

- Paraphrase when you are supporting a particular point and need to draw on a certain place in a text that supports your point—for example, when one paragraph in a source is especially relevant.

- Paraphrase when you want to present a writer’s view on a topic that differs from your position or that of another writer; you can then refute writer’s specific points in your own words after you paraphrase.

- Paraphrase when you want to comment on a particular example that another writer uses.

- Paraphrase when you need to present information that’s unlikely to be questioned.

When you summarize, you are offering an overview of an entire text, or at least a lengthy section of a text. Summary is useful when you are providing background information, grounding your own argument, or mentioning a source as a counter-argument. A summary is less nuanced than paraphrased material. It can be the most effective way to incorporate a large number of sources when you don’t have a lot of space. When you are summarizing someone else’s argument or ideas, be sure this is clear to the reader and cite your source appropriately.

Statistics, data, charts, graphs, photographs, illustrations

Sometimes the best evidence for your argument is a hard fact or visual representation of a fact. This type of evidence can be a solid backbone for your argument, but you still need to create context for your reader and draw the connections you want them to make. Remember that statistics, data, charts, graph, photographs, and illustrations are all open to interpretation. Guide the reader through the interpretation process. Again, always, cite the origin of your evidence if you didn’t produce the material you are using yourself.

Do I need more evidence?

Let’s say that you’ve identified some appropriate sources, found some evidence, explained to the reader how it fits into your overall argument, incorporated it into your draft effectively, and cited your sources. How do you tell whether you’ve got enough evidence and whether it’s working well in the service of a strong argument or analysis? Here are some techniques you can use to review your draft and assess your use of evidence.

Make a reverse outline

A reverse outline is a great technique for helping you see how each paragraph contributes to proving your thesis. When you make a reverse outline, you record the main ideas in each paragraph in a shorter (outline-like) form so that you can see at a glance what is in your paper. The reverse outline is helpful in at least three ways. First, it lets you see where you have dealt with too many topics in one paragraph (in general, you should have one main idea per paragraph). Second, the reverse outline can help you see where you need more evidence to prove your point or more analysis of that evidence. Third, the reverse outline can help you write your topic sentences: once you have decided what you want each paragraph to be about, you can write topic sentences that explain the topics of the paragraphs and state the relationship of each topic to the overall thesis of the paper.

For tips on making a reverse outline, see our handout on organization .

Color code your paper

You will need three highlighters or colored pencils for this exercise. Use one color to highlight general assertions. These will typically be the topic sentences in your paper. Next, use another color to highlight the specific evidence you provide for each assertion (including quotations, paraphrased or summarized material, statistics, examples, and your own ideas). Lastly, use another color to highlight analysis of your evidence. Which assertions are key to your overall argument? Which ones are especially contestable? How much evidence do you have for each assertion? How much analysis? In general, you should have at least as much analysis as you do evidence, or your paper runs the risk of being more summary than argument. The more controversial an assertion is, the more evidence you may need to provide in order to persuade your reader.

Play devil’s advocate, act like a child, or doubt everything

This technique may be easiest to use with a partner. Ask your friend to take on one of the roles above, then read your paper aloud to them. After each section, pause and let your friend interrogate you. If your friend is playing devil’s advocate, they will always take the opposing viewpoint and force you to keep defending yourself. If your friend is acting like a child, they will question every sentence, even seemingly self-explanatory ones. If your friend is a doubter, they won’t believe anything you say. Justifying your position verbally or explaining yourself will force you to strengthen the evidence in your paper. If you already have enough evidence but haven’t connected it clearly enough to your main argument, explaining to your friend how the evidence is relevant or what it proves may help you to do so.

Common questions and additional resources

- I have a general topic in mind; how can I develop it so I’ll know what evidence I need? And how can I get ideas for more evidence? See our handout on brainstorming .

- Who can help me find evidence on my topic? Check out UNC Libraries .

- I’m writing for a specific purpose; how can I tell what kind of evidence my audience wants? See our handouts on audience , writing for specific disciplines , and particular writing assignments .

- How should I read materials to gather evidence? See our handout on reading to write .

- How can I make a good argument? Check out our handouts on argument and thesis statements .

- How do I tell if my paragraphs and my paper are well-organized? Review our handouts on paragraph development , transitions , and reorganizing drafts .

- How do I quote my sources and incorporate those quotes into my text? Our handouts on quotations and avoiding plagiarism offer useful tips.

- How do I cite my evidence? See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

- I think that I’m giving evidence, but my instructor says I’m using too much summary. How can I tell? Check out our handout on using summary wisely.

- I want to use personal experience as evidence, but can I say “I”? We have a handout on when to use “I.”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Miller, Richard E., and Kurt Spellmeyer. 2016. The New Humanities Reader , 5th ed. Boston: Cengage.

University of Maryland. 2019. “Research Using Primary Sources.” Research Guides. Last updated October 28, 2019. https://lib.guides.umd.edu/researchusingprimarysources .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Introduce Evidence: 41 Effective Phrases & Examples

Research requires us to scrutinize information and assess its credibility. Accordingly, when we think about various phenomena, we examine empirical data and craft detailed explanations justifying our interpretations. An essential component of constructing our research narratives is thus providing supporting evidence and examples.

The type of proof we provide can either bolster our claims or leave readers confused or skeptical of our analysis. Therefore, it’s crucial that we use appropriate, logical phrases that guide readers clearly from one idea to the next. In this article, we explain how evidence and examples should be introduced according to different contexts in academic writing and catalog effective language you can use to support your arguments, examples included.

When to Introduce Evidence and Examples in a Paper

Evidence and examples create the foundation upon which your claims can stand firm. Without proof, your arguments lack credibility and teeth. However, laundry listing evidence is as bad as failing to provide any materials or information that can substantiate your conclusions. Therefore, when you introduce examples, make sure to judiciously provide evidence when needed and use phrases that will appropriately and clearly explain how the proof supports your argument.

There are different types of claims and different types of evidence in writing. You should introduce and link your arguments to evidence when you

- state information that is not “common knowledge”;

- draw conclusions, make inferences, or suggest implications based on specific data;

- need to clarify a prior statement, and it would be more effectively done with an illustration;

- need to identify representative examples of a category;

- desire to distinguish concepts; and

- emphasize a point by highlighting a specific situation.

Introductory Phrases to Use and Their Contexts

To assist you with effectively supporting your statements, we have organized the introductory phrases below according to their function. This list is not exhaustive but will provide you with ideas of the types of phrases you can use.

| stating information that is not “common knowledge” | ] | |

| drawing conclusions, making inferences, or suggesting implications based on specific data | ||

| clarifying a prior statement | ||

| identifying representative examples of a category |

*NOTE: “such as” and “like” have two different uses. “Such as” introduces a specific example that is part of a category. “Like” suggests the listed items are similar to, but not included in, the topic discussed. | |

| distinguishing concepts | ||

| emphasizing a point by highlighting a specific situation |

Although any research author can make use of these helpful phrases and bolster their academic writing by entering them into their work, before submitting to a journal, it is a good idea to let a professional English editing service take a look to ensure that all terms and phrases make sense in the given research context. Wordvice offers paper editing , thesis editing , and dissertation editing services that help elevate your academic language and make your writing more compelling to journal authors and researchers alike.

For more examples of strong verbs for research writing , effective transition words for academic papers , or commonly confused words , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources website.

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

Using evidence.

Like a lawyer in a jury trial, a writer must convince her audience of the validity of her argument by using evidence effectively. As a writer, you must also use evidence to persuade your readers to accept your claims. But how do you use evidence to your advantage? By leading your reader through your reasoning.

The types of evidence you use change from discipline to discipline--you might use quotations from a poem or a literary critic, for example, in a literature paper; you might use data from an experiment in a lab report.

The process of putting together your argument is called analysis --it interprets evidence in order to support, test, and/or refine a claim . The chief claim in an analytical essay is called the thesis . A thesis provides the controlling idea for a paper and should be original (that is, not completely obvious), assertive, and arguable. A strong thesis also requires solid evidence to support and develop it because without evidence, a claim is merely an unsubstantiated idea or opinion.

This Web page will cover these basic issues (you can click or scroll down to a particular topic):

- Incorporating evidence effectively.

- Integrating quotations smoothly.

- Citing your sources.

Incorporating Evidence Into Your Essay

When should you incorporate evidence.

Once you have formulated your claim, your thesis (see the WTS pamphlet, " How to Write a Thesis Statement ," for ideas and tips), you should use evidence to help strengthen your thesis and any assertion you make that relates to your thesis. Here are some ways to work evidence into your writing:

- Offer evidence that agrees with your stance up to a point, then add to it with ideas of your own.

- Present evidence that contradicts your stance, and then argue against (refute) that evidence and therefore strengthen your position.

- Use sources against each other, as if they were experts on a panel discussing your proposition.

- Use quotations to support your assertion, not merely to state or restate your claim.

Weak and Strong Uses of Evidence

In order to use evidence effectively, you need to integrate it smoothly into your essay by following this pattern:

- State your claim.

- Give your evidence, remembering to relate it to the claim.

- Comment on the evidence to show how it supports the claim.

To see the differences between strong and weak uses of evidence, here are two paragraphs.

Weak use of evidence

Today, we are too self-centered. Most families no longer sit down to eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This is a weak example of evidence because the evidence is not related to the claim. What does the claim about self-centeredness have to do with families eating together? The writer doesn't explain the connection.

The same evidence can be used to support the same claim, but only with the addition of a clear connection between claim and evidence, and some analysis of the evidence cited.

Stronger use of evidence

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much anymore as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence. In fact, the evidence shows that most American families no longer eat together, preferring instead to eat on the go while rushing to the next appointment (Gleick 148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

This is a far better example, as the evidence is more smoothly integrated into the text, the link between the claim and the evidence is strengthened, and the evidence itself is analyzed to provide support for the claim.

Using Quotations: A Special Type of Evidence

One effective way to support your claim is to use quotations. However, because quotations involve someone else's words, you need to take special care to integrate this kind of evidence into your essay. Here are two examples using quotations, one less effective and one more so.

Ineffective Use of Quotation

Today, we are too self-centered. "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (Gleick 148). Everything is about what we want.

This example is ineffective because the quotation is not integrated with the writer's ideas. Notice how the writer has dropped the quotation into the paragraph without making any connection between it and the claim. Furthermore, she has not discussed the quotation's significance, which makes it difficult for the reader to see the relationship between the evidence and the writer's point.

A More Effective Use of Quotation

Today, Americans are too self-centered. Even our families don't matter as much any more as they once did. Other people and activities take precedence, as James Gleick says in his book, Faster . "We are consumers-on-the-run . . . the very notion of the family meal as a sit-down occasion is vanishing. Adults and children alike eat . . . on the way to their next activity" (148). Sit-down meals are a time to share and connect with others; however, that connection has become less valued, as families begin to prize individual activities over shared time, promoting self-centeredness over group identity.

The second example is more effective because it follows the guidelines for incorporating evidence into an essay. Notice, too, that it uses a lead-in phrase (". . . as James Gleick says in his book, Faster ") to introduce the direct quotation. This lead-in phrase helps to integrate the quotation with the writer's ideas. Also notice that the writer discusses and comments upon the quotation immediately afterwards, which allows the reader to see the quotation's connection to the writer's point.

REMEMBER: Discussing the significance of your evidence develops and expands your paper!

Citing Your Sources

Evidence appears in essays in the form of quotations and paraphrasing. Both forms of evidence must be cited in your text. Citing evidence means distinguishing other writers' information from your own ideas and giving credit to your sources. There are plenty of general ways to do citations. Note both the lead-in phrases and the punctuation (except the brackets) in the following examples:

Quoting: According to Source X, "[direct quotation]" ([date or page #]).

Paraphrasing: Although Source Z argues that [his/her point in your own words], a better way to view the issue is [your own point] ([citation]).

Summarizing: In her book, Source P's main points are Q, R, and S [citation].

Your job during the course of your essay is to persuade your readers that your claims are feasible and are the most effective way of interpreting the evidence.

Questions to Ask Yourself When Revising Your Paper

- Have I offered my reader evidence to substantiate each assertion I make in my paper?

- Do I thoroughly explain why/how my evidence backs up my ideas?

- Do I avoid generalizing in my paper by specifically explaining how my evidence is representative?

- Do I provide evidence that not only confirms but also qualifies my paper's main claims?

- Do I use evidence to test and evolve my ideas, rather than to just confirm them?

- Do I cite my sources thoroughly and correctly?

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Finance and Business

- Legal Matters

- Contracts and Legal Agreements

How to Introduce Evidence in an Essay

Last Updated: May 5, 2024

This article was co-authored by Tristen Bonacci . Tristen Bonacci is a Licensed English Teacher with more than 20 years of experience. Tristen has taught in both the United States and overseas. She specializes in teaching in a secondary education environment and sharing wisdom with others, no matter the environment. Tristen holds a BA in English Literature from The University of Colorado and an MEd from The University of Phoenix. This article has been viewed 240,794 times.

When well integrated into your argument, evidence helps prove that you've done your research and thought critically about your topic. But what's the best way to introduce evidence so it feels seamless and has the highest impact? There are actually quite a few effective strategies you can use, and we've rounded up the best ones for you here. Try some of the tips below to introduce evidence in your essay and make a persuasive argument.

Things You Should Know

- "According to..."

- "The text says..."

- "Researchers have learned..."

- "For example..."

- "[Author's name] writes..."

Setting up the Evidence

- You can use 1-2 sentences to set up the evidence, if needed, but usually more concise you are, the better.

- For example, you may make an argument like, “Desire is a complicated, confusing emotion that causes pain to others.”

- Or you may make an assertion like, “The treatment of addiction must consider root cause issues like mental health and poor living conditions.”

- For example, you may write, “The novel explores the theme of adolescent love and desire.”

- Or you may write, “Many studies show that addiction is a mental health issue.”

Putting in the Evidence

- For example, you may use an introductory clause like, “According to Anne Carson…”, "In the following chart...," “The author states…," "The survey shows...." or “The study argues…”

- Place a comma after the introductory clause if you are using a quote. For example, “According to Anne Carson, ‘Desire is no light thing" or "The study notes, 'levels of addiction rise as levels of poverty and homelessness also rise.'"

- A list of introductory clauses can be found here: https://student.unsw.edu.au/introducing-quotations-and-paraphrases .

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, Carson is never shy about how her characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back…’”

- Or you may write, "The study charts the rise in addiction levels, concluding: 'There is a higher level of addiction in specific areas of the United States.'"

- For example, you may write, “Carson views events as inevitable, as man moving through time like “a harpoon,” much like the fates of her characters.”

- Or you may write, "The chart indicates the rising levels of addiction in young people, an "epidemic" that shows no sign of slowing down."

- For example, you may write in the first mention, “In Anne Carson’s The Autobiography of Red , the color red signifies desire, love, and monstrosity.” Or you may write, "In the study Addiction Rates conducted by the Harvard Review...".

- After the first mention, you can write, “Carson states…” or “The study explores…”.

- If you are citing the author’s name in-text as part of your citation style, you do not need to note their name in the text. You can just use the quote and then place the citation at the end.

- If you are paraphrasing a source, you may still use quotation marks around any text you are lifting directly from the source.

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, the characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back (Carson, 48).”

- Or you may write, "Based on the data in the graph below, the study shows the 'intersection between opioid addiction and income' (Branson, 10)."

- If you are using footnotes or endnotes, make sure you use the appropriate citation for each piece of evidence you place in your essay.

- You may also mention the title of the work or source you are paraphrasing or summarizing and the author's name in the paraphrase or summary.

- For example, you may write a paraphrase like, "As noted in various studies, the correlation between addiction and mental illness is often ignored by medical health professionals (Deder, 10)."

- Or you may write a summary like, " The Autobiography of Red is an exploration of desire and love between strange beings, what critics have called a hybrid work that combines ancient meter with modern language (Zambreno, 15)."

- The only time you should place 2 pieces of evidence together is when you want to directly compare 2 short quotes (each less than 1 line long).

- Your analysis should then include a complete compare and contrast of the 2 quotes to show you have thought critically about them both.

Analyzing the Evidence

- For example, you may write, “In the novel, Carson is never shy about how her characters express desire for each other: ‘When they made love/ Geryon liked to touch in slow succession each of the bones of Herakles' back (Carson, 48). The connection between Geryon and Herakles is intimate and gentle, a love that connects the two characters in a physical and emotional way.”

- Or you may write, "In the study Addiction Rates conducted by the Harvard Review, the data shows a 50% rise in addiction levels in specific areas across the United States. The study illustrates a clear connection between addiction levels and communities where income falls below the poverty line and there is a housing shortage or crisis."

- For example, you may write, “Carson’s treatment of the relationship between Geryon and Herakles can be linked back to her approach to desire as a whole in the novel, which acts as both a catalyst and an impediment for her characters.”

- Or you may write, "The survey conducted by Dr. Paula Bronson, accompanied by a detailed academic dissertation, supports the argument that addiction is not a stand alone issue that can be addressed in isolation."

- For example, you may write, “The value of love between two people is not romanticized, but it is still considered essential, similar to the feeling of belonging, another key theme in the novel.”

- Or you may write, "There is clearly a need to reassess the current thinking around addiction and mental illness so the health and sciences community can better study these pressing issues."

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ Tristen Bonacci. Licensed English Teacher. Expert Interview. 21 December 2021.

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/quoliterature/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/evidence/

- ↑ https://wts.indiana.edu/writing-guides/using-evidence.html

About This Article

Before you introduce evidence into your essay, begin the paragraph with a topic sentence. This sentence should give the reader an overview of the point you’ll be arguing or making with the evidence. When you get to citing the evidence, begin the sentence with a clause like, “The study finds” or “According to Anne Carson.” You can also include a short quotation in the middle of a sentence without introducing it with a clause. Remember to introduce the author’s first and last name when you use the evidence for the first time. Afterwards, you can just mention their last name. Once you’ve presented the evidence, take time to explain in your own words how it backs up the point you’re making. For tips on how to reference your evidence correctly, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Apr 15, 2022

Did this article help you?

Mar 2, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

3 Strong Argumentative Essay Examples, Analyzed

General Education

Need to defend your opinion on an issue? Argumentative essays are one of the most popular types of essays you’ll write in school. They combine persuasive arguments with fact-based research, and, when done well, can be powerful tools for making someone agree with your point of view. If you’re struggling to write an argumentative essay or just want to learn more about them, seeing examples can be a big help.

After giving an overview of this type of essay, we provide three argumentative essay examples. After each essay, we explain in-depth how the essay was structured, what worked, and where the essay could be improved. We end with tips for making your own argumentative essay as strong as possible.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an essay that uses evidence and facts to support the claim it’s making. Its purpose is to persuade the reader to agree with the argument being made.

A good argumentative essay will use facts and evidence to support the argument, rather than just the author’s thoughts and opinions. For example, say you wanted to write an argumentative essay stating that Charleston, SC is a great destination for families. You couldn’t just say that it’s a great place because you took your family there and enjoyed it. For it to be an argumentative essay, you need to have facts and data to support your argument, such as the number of child-friendly attractions in Charleston, special deals you can get with kids, and surveys of people who visited Charleston as a family and enjoyed it. The first argument is based entirely on feelings, whereas the second is based on evidence that can be proven.

The standard five paragraph format is common, but not required, for argumentative essays. These essays typically follow one of two formats: the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model.

- The Toulmin model is the most common. It begins with an introduction, follows with a thesis/claim, and gives data and evidence to support that claim. This style of essay also includes rebuttals of counterarguments.

- The Rogerian model analyzes two sides of an argument and reaches a conclusion after weighing the strengths and weaknesses of each.

3 Good Argumentative Essay Examples + Analysis

Below are three examples of argumentative essays, written by yours truly in my school days, as well as analysis of what each did well and where it could be improved.

Argumentative Essay Example 1

Proponents of this idea state that it will save local cities and towns money because libraries are expensive to maintain. They also believe it will encourage more people to read because they won’t have to travel to a library to get a book; they can simply click on what they want to read and read it from wherever they are. They could also access more materials because libraries won’t have to buy physical copies of books; they can simply rent out as many digital copies as they need.

However, it would be a serious mistake to replace libraries with tablets. First, digital books and resources are associated with less learning and more problems than print resources. A study done on tablet vs book reading found that people read 20-30% slower on tablets, retain 20% less information, and understand 10% less of what they read compared to people who read the same information in print. Additionally, staring too long at a screen has been shown to cause numerous health problems, including blurred vision, dizziness, dry eyes, headaches, and eye strain, at much higher instances than reading print does. People who use tablets and mobile devices excessively also have a higher incidence of more serious health issues such as fibromyalgia, shoulder and back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and muscle strain. I know that whenever I read from my e-reader for too long, my eyes begin to feel tired and my neck hurts. We should not add to these problems by giving people, especially young people, more reasons to look at screens.

Second, it is incredibly narrow-minded to assume that the only service libraries offer is book lending. Libraries have a multitude of benefits, and many are only available if the library has a physical location. Some of these benefits include acting as a quiet study space, giving people a way to converse with their neighbors, holding classes on a variety of topics, providing jobs, answering patron questions, and keeping the community connected. One neighborhood found that, after a local library instituted community events such as play times for toddlers and parents, job fairs for teenagers, and meeting spaces for senior citizens, over a third of residents reported feeling more connected to their community. Similarly, a Pew survey conducted in 2015 found that nearly two-thirds of American adults feel that closing their local library would have a major impact on their community. People see libraries as a way to connect with others and get their questions answered, benefits tablets can’t offer nearly as well or as easily.

While replacing libraries with tablets may seem like a simple solution, it would encourage people to spend even more time looking at digital screens, despite the myriad issues surrounding them. It would also end access to many of the benefits of libraries that people have come to rely on. In many areas, libraries are such an important part of the community network that they could never be replaced by a simple object.

The author begins by giving an overview of the counter-argument, then the thesis appears as the first sentence in the third paragraph. The essay then spends the rest of the paper dismantling the counter argument and showing why readers should believe the other side.

What this essay does well:

- Although it’s a bit unusual to have the thesis appear fairly far into the essay, it works because, once the thesis is stated, the rest of the essay focuses on supporting it since the counter-argument has already been discussed earlier in the paper.

- This essay includes numerous facts and cites studies to support its case. By having specific data to rely on, the author’s argument is stronger and readers will be more inclined to agree with it.

- For every argument the other side makes, the author makes sure to refute it and follow up with why her opinion is the stronger one. In order to make a strong argument, it’s important to dismantle the other side, which this essay does this by making the author's view appear stronger.

- This is a shorter paper, and if it needed to be expanded to meet length requirements, it could include more examples and go more into depth with them, such as by explaining specific cases where people benefited from local libraries.

- Additionally, while the paper uses lots of data, the author also mentions their own experience with using tablets. This should be removed since argumentative essays focus on facts and data to support an argument, not the author’s own opinion or experiences. Replacing that with more data on health issues associated with screen time would strengthen the essay.

- Some of the points made aren't completely accurate , particularly the one about digital books being cheaper. It actually often costs a library more money to rent out numerous digital copies of a book compared to buying a single physical copy. Make sure in your own essay you thoroughly research each of the points and rebuttals you make, otherwise you'll look like you don't know the issue that well.

Argumentative Essay Example 2

There are multiple drugs available to treat malaria, and many of them work well and save lives, but malaria eradication programs that focus too much on them and not enough on prevention haven’t seen long-term success in Sub-Saharan Africa. A major program to combat malaria was WHO’s Global Malaria Eradication Programme. Started in 1955, it had a goal of eliminating malaria in Africa within the next ten years. Based upon previously successful programs in Brazil and the United States, the program focused mainly on vector control. This included widely distributing chloroquine and spraying large amounts of DDT. More than one billion dollars was spent trying to abolish malaria. However, the program suffered from many problems and in 1969, WHO was forced to admit that the program had not succeeded in eradicating malaria. The number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa who contracted malaria as well as the number of malaria deaths had actually increased over 10% during the time the program was active.

One of the major reasons for the failure of the project was that it set uniform strategies and policies. By failing to consider variations between governments, geography, and infrastructure, the program was not nearly as successful as it could have been. Sub-Saharan Africa has neither the money nor the infrastructure to support such an elaborate program, and it couldn’t be run the way it was meant to. Most African countries don't have the resources to send all their people to doctors and get shots, nor can they afford to clear wetlands or other malaria prone areas. The continent’s spending per person for eradicating malaria was just a quarter of what Brazil spent. Sub-Saharan Africa simply can’t rely on a plan that requires more money, infrastructure, and expertise than they have to spare.

Additionally, the widespread use of chloroquine has created drug resistant parasites which are now plaguing Sub-Saharan Africa. Because chloroquine was used widely but inconsistently, mosquitoes developed resistance, and chloroquine is now nearly completely ineffective in Sub-Saharan Africa, with over 95% of mosquitoes resistant to it. As a result, newer, more expensive drugs need to be used to prevent and treat malaria, which further drives up the cost of malaria treatment for a region that can ill afford it.

Instead of developing plans to treat malaria after the infection has incurred, programs should focus on preventing infection from occurring in the first place. Not only is this plan cheaper and more effective, reducing the number of people who contract malaria also reduces loss of work/school days which can further bring down the productivity of the region.

One of the cheapest and most effective ways of preventing malaria is to implement insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs). These nets provide a protective barrier around the person or people using them. While untreated bed nets are still helpful, those treated with insecticides are much more useful because they stop mosquitoes from biting people through the nets, and they help reduce mosquito populations in a community, thus helping people who don’t even own bed nets. Bed nets are also very effective because most mosquito bites occur while the person is sleeping, so bed nets would be able to drastically reduce the number of transmissions during the night. In fact, transmission of malaria can be reduced by as much as 90% in areas where the use of ITNs is widespread. Because money is so scarce in Sub-Saharan Africa, the low cost is a great benefit and a major reason why the program is so successful. Bed nets cost roughly 2 USD to make, last several years, and can protect two adults. Studies have shown that, for every 100-1000 more nets are being used, one less child dies of malaria. With an estimated 300 million people in Africa not being protected by mosquito nets, there’s the potential to save three million lives by spending just a few dollars per person.

Reducing the number of people who contract malaria would also reduce poverty levels in Africa significantly, thus improving other aspects of society like education levels and the economy. Vector control is more effective than treatment strategies because it means fewer people are getting sick. When fewer people get sick, the working population is stronger as a whole because people are not put out of work from malaria, nor are they caring for sick relatives. Malaria-afflicted families can typically only harvest 40% of the crops that healthy families can harvest. Additionally, a family with members who have malaria spends roughly a quarter of its income treatment, not including the loss of work they also must deal with due to the illness. It’s estimated that malaria costs Africa 12 billion USD in lost income every year. A strong working population creates a stronger economy, which Sub-Saharan Africa is in desperate need of.

This essay begins with an introduction, which ends with the thesis (that malaria eradication plans in Sub-Saharan Africa should focus on prevention rather than treatment). The first part of the essay lays out why the counter argument (treatment rather than prevention) is not as effective, and the second part of the essay focuses on why prevention of malaria is the better path to take.

- The thesis appears early, is stated clearly, and is supported throughout the rest of the essay. This makes the argument clear for readers to understand and follow throughout the essay.

- There’s lots of solid research in this essay, including specific programs that were conducted and how successful they were, as well as specific data mentioned throughout. This evidence helps strengthen the author’s argument.

- The author makes a case for using expanding bed net use over waiting until malaria occurs and beginning treatment, but not much of a plan is given for how the bed nets would be distributed or how to ensure they’re being used properly. By going more into detail of what she believes should be done, the author would be making a stronger argument.

- The introduction of the essay does a good job of laying out the seriousness of the problem, but the conclusion is short and abrupt. Expanding it into its own paragraph would give the author a final way to convince readers of her side of the argument.

Argumentative Essay Example 3

There are many ways payments could work. They could be in the form of a free-market approach, where athletes are able to earn whatever the market is willing to pay them, it could be a set amount of money per athlete, or student athletes could earn income from endorsements, autographs, and control of their likeness, similar to the way top Olympians earn money.

Proponents of the idea believe that, because college athletes are the ones who are training, participating in games, and bringing in audiences, they should receive some sort of compensation for their work. If there were no college athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t exist, college coaches wouldn’t receive there (sometimes very high) salaries, and brands like Nike couldn’t profit from college sports. In fact, the NCAA brings in roughly $1 billion in revenue a year, but college athletes don’t receive any of that money in the form of a paycheck. Additionally, people who believe college athletes should be paid state that paying college athletes will actually encourage them to remain in college longer and not turn pro as quickly, either by giving them a way to begin earning money in college or requiring them to sign a contract stating they’ll stay at the university for a certain number of years while making an agreed-upon salary.

Supporters of this idea point to Zion Williamson, the Duke basketball superstar, who, during his freshman year, sustained a serious knee injury. Many argued that, even if he enjoyed playing for Duke, it wasn’t worth risking another injury and ending his professional career before it even began for a program that wasn’t paying him. Williamson seems to have agreed with them and declared his eligibility for the NCAA draft later that year. If he was being paid, he may have stayed at Duke longer. In fact, roughly a third of student athletes surveyed stated that receiving a salary while in college would make them “strongly consider” remaining collegiate athletes longer before turning pro.

Paying athletes could also stop the recruitment scandals that have plagued the NCAA. In 2018, the NCAA stripped the University of Louisville's men's basketball team of its 2013 national championship title because it was discovered coaches were using sex workers to entice recruits to join the team. There have been dozens of other recruitment scandals where college athletes and recruits have been bribed with anything from having their grades changed, to getting free cars, to being straight out bribed. By paying college athletes and putting their salaries out in the open, the NCAA could end the illegal and underhanded ways some schools and coaches try to entice athletes to join.

People who argue against the idea of paying college athletes believe the practice could be disastrous for college sports. By paying athletes, they argue, they’d turn college sports into a bidding war, where only the richest schools could afford top athletes, and the majority of schools would be shut out from developing a talented team (though some argue this already happens because the best players often go to the most established college sports programs, who typically pay their coaches millions of dollars per year). It could also ruin the tight camaraderie of many college teams if players become jealous that certain teammates are making more money than they are.

They also argue that paying college athletes actually means only a small fraction would make significant money. Out of the 350 Division I athletic departments, fewer than a dozen earn any money. Nearly all the money the NCAA makes comes from men’s football and basketball, so paying college athletes would make a small group of men--who likely will be signed to pro teams and begin making millions immediately out of college--rich at the expense of other players.

Those against paying college athletes also believe that the athletes are receiving enough benefits already. The top athletes already receive scholarships that are worth tens of thousands per year, they receive free food/housing/textbooks, have access to top medical care if they are injured, receive top coaching, get travel perks and free gear, and can use their time in college as a way to capture the attention of professional recruiters. No other college students receive anywhere near as much from their schools.

People on this side also point out that, while the NCAA brings in a massive amount of money each year, it is still a non-profit organization. How? Because over 95% of those profits are redistributed to its members’ institutions in the form of scholarships, grants, conferences, support for Division II and Division III teams, and educational programs. Taking away a significant part of that revenue would hurt smaller programs that rely on that money to keep running.

While both sides have good points, it’s clear that the negatives of paying college athletes far outweigh the positives. College athletes spend a significant amount of time and energy playing for their school, but they are compensated for it by the scholarships and perks they receive. Adding a salary to that would result in a college athletic system where only a small handful of athletes (those likely to become millionaires in the professional leagues) are paid by a handful of schools who enter bidding wars to recruit them, while the majority of student athletics and college athletic programs suffer or even shut down for lack of money. Continuing to offer the current level of benefits to student athletes makes it possible for as many people to benefit from and enjoy college sports as possible.

This argumentative essay follows the Rogerian model. It discusses each side, first laying out multiple reasons people believe student athletes should be paid, then discussing reasons why the athletes shouldn’t be paid. It ends by stating that college athletes shouldn’t be paid by arguing that paying them would destroy college athletics programs and cause them to have many of the issues professional sports leagues have.

- Both sides of the argument are well developed, with multiple reasons why people agree with each side. It allows readers to get a full view of the argument and its nuances.

- Certain statements on both sides are directly rebuffed in order to show where the strengths and weaknesses of each side lie and give a more complete and sophisticated look at the argument.

- Using the Rogerian model can be tricky because oftentimes you don’t explicitly state your argument until the end of the paper. Here, the thesis doesn’t appear until the first sentence of the final paragraph. That doesn’t give readers a lot of time to be convinced that your argument is the right one, compared to a paper where the thesis is stated in the beginning and then supported throughout the paper. This paper could be strengthened if the final paragraph was expanded to more fully explain why the author supports the view, or if the paper had made it clearer that paying athletes was the weaker argument throughout.

3 Tips for Writing a Good Argumentative Essay

Now that you’ve seen examples of what good argumentative essay samples look like, follow these three tips when crafting your own essay.

#1: Make Your Thesis Crystal Clear

The thesis is the key to your argumentative essay; if it isn’t clear or readers can’t find it easily, your entire essay will be weak as a result. Always make sure that your thesis statement is easy to find. The typical spot for it is the final sentence of the introduction paragraph, but if it doesn’t fit in that spot for your essay, try to at least put it as the first or last sentence of a different paragraph so it stands out more.

Also make sure that your thesis makes clear what side of the argument you’re on. After you’ve written it, it’s a great idea to show your thesis to a couple different people--classmates are great for this. Just by reading your thesis they should be able to understand what point you’ll be trying to make with the rest of your essay.

#2: Show Why the Other Side Is Weak

When writing your essay, you may be tempted to ignore the other side of the argument and just focus on your side, but don’t do this. The best argumentative essays really tear apart the other side to show why readers shouldn’t believe it. Before you begin writing your essay, research what the other side believes, and what their strongest points are. Then, in your essay, be sure to mention each of these and use evidence to explain why they’re incorrect/weak arguments. That’ll make your essay much more effective than if you only focused on your side of the argument.

#3: Use Evidence to Support Your Side

Remember, an essay can’t be an argumentative essay if it doesn’t support its argument with evidence. For every point you make, make sure you have facts to back it up. Some examples are previous studies done on the topic, surveys of large groups of people, data points, etc. There should be lots of numbers in your argumentative essay that support your side of the argument. This will make your essay much stronger compared to only relying on your own opinions to support your argument.

Summary: Argumentative Essay Sample

Argumentative essays are persuasive essays that use facts and evidence to support their side of the argument. Most argumentative essays follow either the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model. By reading good argumentative essay examples, you can learn how to develop your essay and provide enough support to make readers agree with your opinion. When writing your essay, remember to always make your thesis clear, show where the other side is weak, and back up your opinion with data and evidence.

What's Next?

Do you need to write an argumentative essay as well? Check out our guide on the best argumentative essay topics for ideas!

You'll probably also need to write research papers for school. We've got you covered with 113 potential topics for research papers.

Your college admissions essay may end up being one of the most important essays you write. Follow our step-by-step guide on writing a personal statement to have an essay that'll impress colleges.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Types of Evidence in Writing [Ultimate Guide + Examples]

When it comes to writing, the strength of your argument often hinges on the evidence you present.

Here is a quick summary of the types of evidence in writing: