- Privacy Policy

Home » Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Significance of the Study

Definition:

Significance of the study in research refers to the potential importance, relevance, or impact of the research findings. It outlines how the research contributes to the existing body of knowledge, what gaps it fills, or what new understanding it brings to a particular field of study.

In general, the significance of a study can be assessed based on several factors, including:

- Originality : The extent to which the study advances existing knowledge or introduces new ideas and perspectives.

- Practical relevance: The potential implications of the study for real-world situations, such as improving policy or practice.

- Theoretical contribution: The extent to which the study provides new insights or perspectives on theoretical concepts or frameworks.

- Methodological rigor : The extent to which the study employs appropriate and robust methods and techniques to generate reliable and valid data.

- Social or cultural impact : The potential impact of the study on society, culture, or public perception of a particular issue.

Types of Significance of the Study

The significance of the Study can be divided into the following types:

Theoretical Significance

Theoretical significance refers to the contribution that a study makes to the existing body of theories in a specific field. This could be by confirming, refuting, or adding nuance to a currently accepted theory, or by proposing an entirely new theory.

Practical Significance

Practical significance refers to the direct applicability and usefulness of the research findings in real-world contexts. Studies with practical significance often address real-life problems and offer potential solutions or strategies. For example, a study in the field of public health might identify a new intervention that significantly reduces the spread of a certain disease.

Significance for Future Research

This pertains to the potential of a study to inspire further research. A study might open up new areas of investigation, provide new research methodologies, or propose new hypotheses that need to be tested.

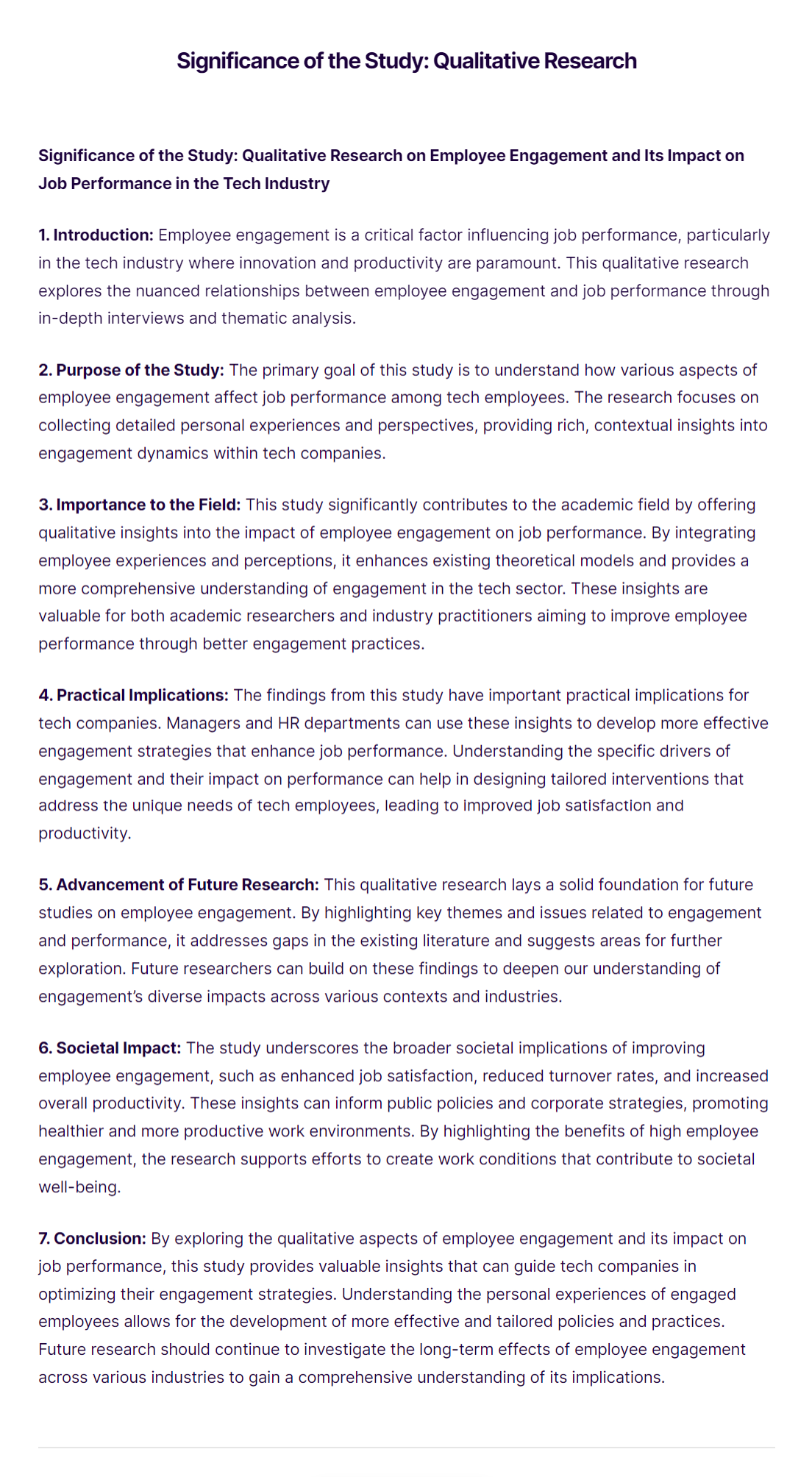

How to Write Significance of the Study

Here’s a guide to writing an effective “Significance of the Study” section in research paper, thesis, or dissertation:

- Background : Begin by giving some context about your study. This could include a brief introduction to your subject area, the current state of research in the field, and the specific problem or question your study addresses.

- Identify the Gap : Demonstrate that there’s a gap in the existing literature or knowledge that needs to be filled, which is where your study comes in. The gap could be a lack of research on a particular topic, differing results in existing studies, or a new problem that has arisen and hasn’t yet been studied.

- State the Purpose of Your Study : Clearly state the main objective of your research. You may want to state the purpose as a solution to the problem or gap you’ve previously identified.

- Contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

- Addresses a significant research gap.

- Offers a new or better solution to a problem.

- Impacts policy or practice.

- Leads to improvements in a particular field or sector.

- Identify Beneficiaries : Identify who will benefit from your study. This could include other researchers, practitioners in your field, policy-makers, communities, businesses, or others. Explain how your findings could be used and by whom.

- Future Implications : Discuss the implications of your study for future research. This could involve questions that are left open, new questions that have been raised, or potential future methodologies suggested by your study.

Significance of the Study in Research Paper

The Significance of the Study in a research paper refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic being investigated. It answers the question “Why is this research important?” and highlights the potential contributions and impacts of the study.

The significance of the study can be presented in the introduction or background section of a research paper. It typically includes the following components:

- Importance of the research problem: This describes why the research problem is worth investigating and how it relates to existing knowledge and theories.

- Potential benefits and implications: This explains the potential contributions and impacts of the research on theory, practice, policy, or society.

- Originality and novelty: This highlights how the research adds new insights, approaches, or methods to the existing body of knowledge.

- Scope and limitations: This outlines the boundaries and constraints of the research and clarifies what the study will and will not address.

Suppose a researcher is conducting a study on the “Effects of social media use on the mental health of adolescents”.

The significance of the study may be:

“The present study is significant because it addresses a pressing public health issue of the negative impact of social media use on adolescent mental health. Given the widespread use of social media among this age group, understanding the effects of social media on mental health is critical for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. This study will contribute to the existing literature by examining the moderating factors that may affect the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes. It will also shed light on the potential benefits and risks of social media use for adolescents and inform the development of evidence-based guidelines for promoting healthy social media use among this population. The limitations of this study include the use of self-reported measures and the cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inference.”

Significance of the Study In Thesis

The significance of the study in a thesis refers to the importance or relevance of the research topic and the potential impact of the study on the field of study or society as a whole. It explains why the research is worth doing and what contribution it will make to existing knowledge.

For example, the significance of a thesis on “Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare” could be:

- With the increasing availability of healthcare data and the development of advanced machine learning algorithms, AI has the potential to revolutionize the healthcare industry by improving diagnosis, treatment, and patient outcomes. Therefore, this thesis can contribute to the understanding of how AI can be applied in healthcare and how it can benefit patients and healthcare providers.

- AI in healthcare also raises ethical and social issues, such as privacy concerns, bias in algorithms, and the impact on healthcare jobs. By exploring these issues in the thesis, it can provide insights into the potential risks and benefits of AI in healthcare and inform policy decisions.

- Finally, the thesis can also advance the field of computer science by developing new AI algorithms or techniques that can be applied to healthcare data, which can have broader applications in other industries or fields of research.

Significance of the Study in Research Proposal

The significance of a study in a research proposal refers to the importance or relevance of the research question, problem, or objective that the study aims to address. It explains why the research is valuable, relevant, and important to the academic or scientific community, policymakers, or society at large. A strong statement of significance can help to persuade the reviewers or funders of the research proposal that the study is worth funding and conducting.

Here is an example of a significance statement in a research proposal:

Title : The Effects of Gamification on Learning Programming: A Comparative Study

Significance Statement:

This proposed study aims to investigate the effects of gamification on learning programming. With the increasing demand for computer science professionals, programming has become a fundamental skill in the computer field. However, learning programming can be challenging, and students may struggle with motivation and engagement. Gamification has emerged as a promising approach to improve students’ engagement and motivation in learning, but its effects on programming education are not yet fully understood. This study is significant because it can provide valuable insights into the potential benefits of gamification in programming education and inform the development of effective teaching strategies to enhance students’ learning outcomes and interest in programming.

Examples of Significance of the Study

Here are some examples of the significance of a study that indicates how you can write this into your research paper according to your research topic:

Research on an Improved Water Filtration System : This study has the potential to impact millions of people living in water-scarce regions or those with limited access to clean water. A more efficient and affordable water filtration system can reduce water-borne diseases and improve the overall health of communities, enabling them to lead healthier, more productive lives.

Study on the Impact of Remote Work on Employee Productivity : Given the shift towards remote work due to recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, this study is of considerable significance. Findings could help organizations better structure their remote work policies and offer insights on how to maximize employee productivity, wellbeing, and job satisfaction.

Investigation into the Use of Solar Power in Developing Countries : With the world increasingly moving towards renewable energy, this study could provide important data on the feasibility and benefits of implementing solar power solutions in developing countries. This could potentially stimulate economic growth, reduce reliance on non-renewable resources, and contribute to global efforts to combat climate change.

Research on New Learning Strategies in Special Education : This study has the potential to greatly impact the field of special education. By understanding the effectiveness of new learning strategies, educators can improve their curriculum to provide better support for students with learning disabilities, fostering their academic growth and social development.

Examination of Mental Health Support in the Workplace : This study could highlight the impact of mental health initiatives on employee wellbeing and productivity. It could influence organizational policies across industries, promoting the implementation of mental health programs in the workplace, ultimately leading to healthier work environments.

Evaluation of a New Cancer Treatment Method : The significance of this study could be lifesaving. The research could lead to the development of more effective cancer treatments, increasing the survival rate and quality of life for patients worldwide.

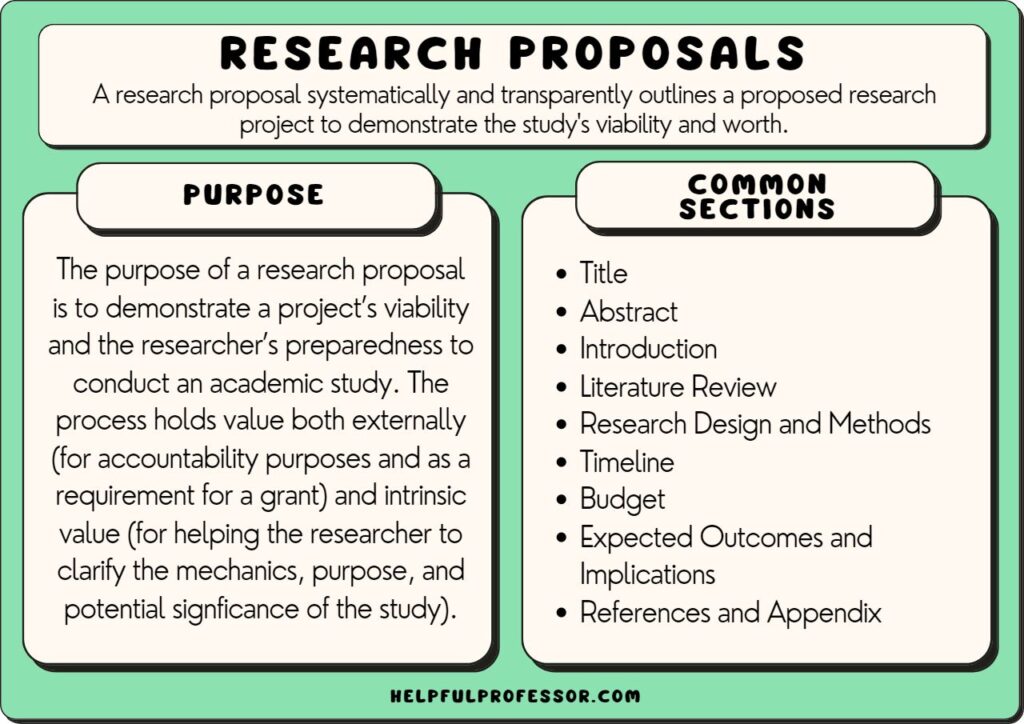

When to Write Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section is an integral part of a research proposal or a thesis. This section is typically written after the introduction and the literature review. In the research process, the structure typically follows this order:

- Title – The name of your research.

- Abstract – A brief summary of the entire research.

- Introduction – A presentation of the problem your research aims to solve.

- Literature Review – A review of existing research on the topic to establish what is already known and where gaps exist.

- Significance of the Study – An explanation of why the research matters and its potential impact.

In the Significance of the Study section, you will discuss why your study is important, who it benefits, and how it adds to existing knowledge or practice in your field. This section is your opportunity to convince readers, and potentially funders or supervisors, that your research is valuable and worth undertaking.

Advantages of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section in a research paper has multiple advantages:

- Establishes Relevance: This section helps to articulate the importance of your research to your field of study, as well as the wider society, by explicitly stating its relevance. This makes it easier for other researchers, funders, and policymakers to understand why your work is necessary and worth supporting.

- Guides the Research: Writing the significance can help you refine your research questions and objectives. This happens as you critically think about why your research is important and how it contributes to your field.

- Attracts Funding: If you are seeking funding or support for your research, having a well-written significance of the study section can be key. It helps to convince potential funders of the value of your work.

- Opens up Further Research: By stating the significance of the study, you’re also indicating what further research could be carried out in the future, based on your work. This helps to pave the way for future studies and demonstrates that your research is a valuable addition to the field.

- Provides Practical Applications: The significance of the study section often outlines how the research can be applied in real-world situations. This can be particularly important in applied sciences, where the practical implications of research are crucial.

- Enhances Understanding: This section can help readers understand how your study fits into the broader context of your field, adding value to the existing literature and contributing new knowledge or insights.

Limitations of Significance of the Study

The Significance of the Study section plays an essential role in any research. However, it is not without potential limitations. Here are some that you should be aware of:

- Subjectivity: The importance and implications of a study can be subjective and may vary from person to person. What one researcher considers significant might be seen as less critical by others. The assessment of significance often depends on personal judgement, biases, and perspectives.

- Predictability of Impact: While you can outline the potential implications of your research in the Significance of the Study section, the actual impact can be unpredictable. Research doesn’t always yield the expected results or have the predicted impact on the field or society.

- Difficulty in Measuring: The significance of a study is often qualitative and can be challenging to measure or quantify. You can explain how you think your research will contribute to your field or society, but measuring these outcomes can be complex.

- Possibility of Overstatement: Researchers may feel pressured to amplify the potential significance of their study to attract funding or interest. This can lead to overstating the potential benefits or implications, which can harm the credibility of the study if these results are not achieved.

- Overshadowing of Limitations: Sometimes, the significance of the study may overshadow the limitations of the research. It is important to balance the potential significance with a thorough discussion of the study’s limitations.

- Dependence on Successful Implementation: The significance of the study relies on the successful implementation of the research. If the research process has flaws or unexpected issues arise, the anticipated significance might not be realized.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

Research Recommendations – Examples and Writing...

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and...

Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates...

Background of The Study – Examples and Writing...

- CREd Library , Planning, Managing, and Publishing Research

Grant Section Analysis: Significance and Innovation

Part 2 in a section-by-section overview with tips, suggestions, and examples for writing a strong research grant application., shelley i. gray.

- April, 2014

DOI: 10.1044/cred-pvd-lfs002

The following is a transcript of the presentation video, edited for clarity.

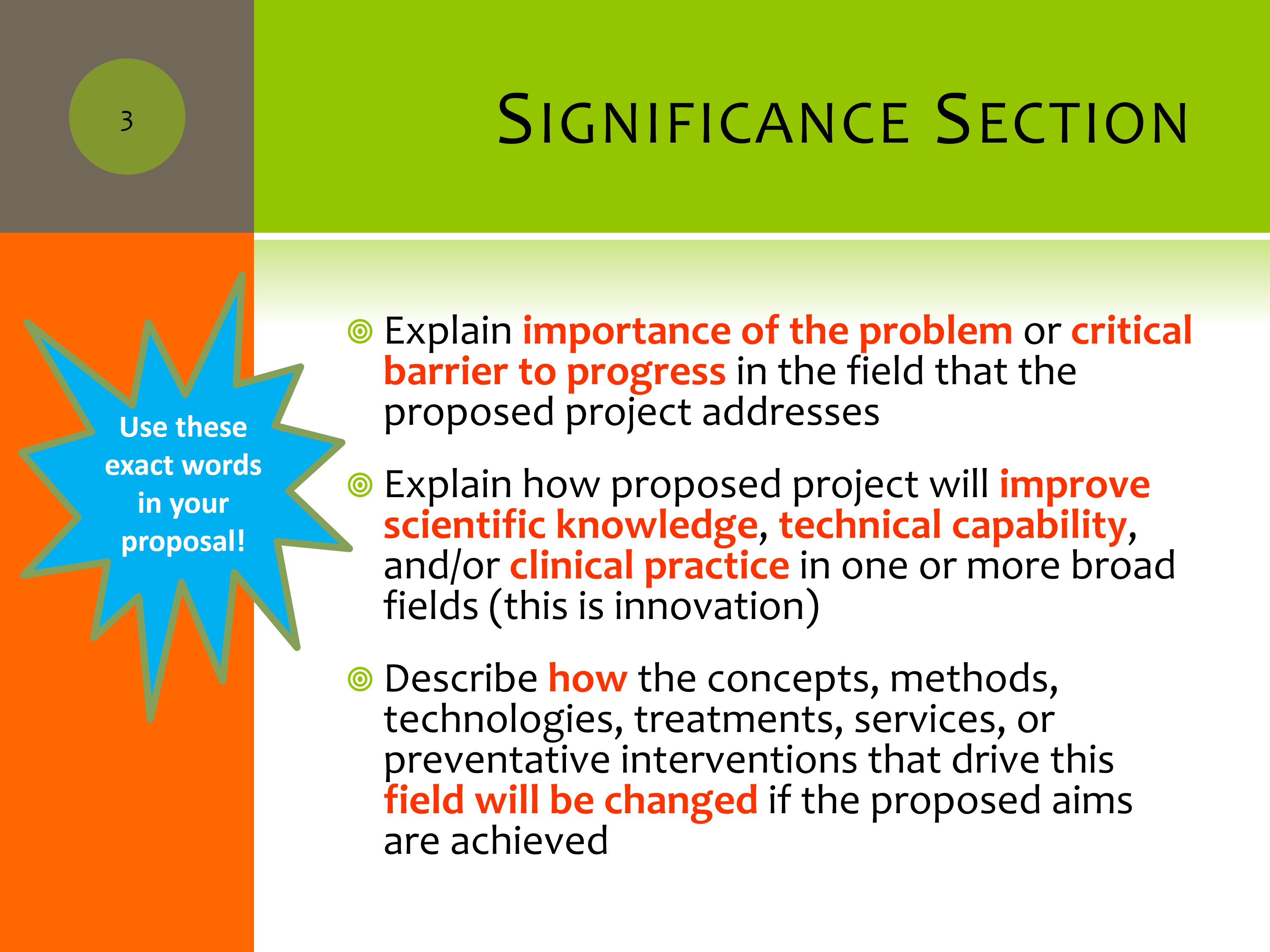

Significance

In the Significance Section, I’ve highlighted the key words straight from the instructions on what you should include. What we’re recommending is that you take this exact wording right out of the instructions and use it in your application. That makes it easy for the reviewers to find these critical words that are like little guideposts in your grant application.

You can see the words here. I think someone yesterday said that they keep a list of these things right up by their computer, or right on their desktop, as they are writing to make sure they’re being constantly reminded to include them as they write.

Clarity of Purpose

One of the more difficult things to do is to achieve this clarity of purpose. We have broad ideas, we have lots of ideas about what we want to do. For a grant application proposal, you really need to get a laser-focus on what you’re trying to accomplish, and be able to communicate that to the reviewer.

Your wording should convey your purpose clearly, enthusiastically, and concisely. To do that, one of the things I suggest is to use words with positive valence in your application. Words with positive valence evoke happy and positive thoughts as you read them. We’re using priming of positive valence words to help build a positive attitude.

Don’t be tentative. Be proactive and be confident in your grant proposal. We’ll talk about some words that are tentative. And do your best not to be vague.

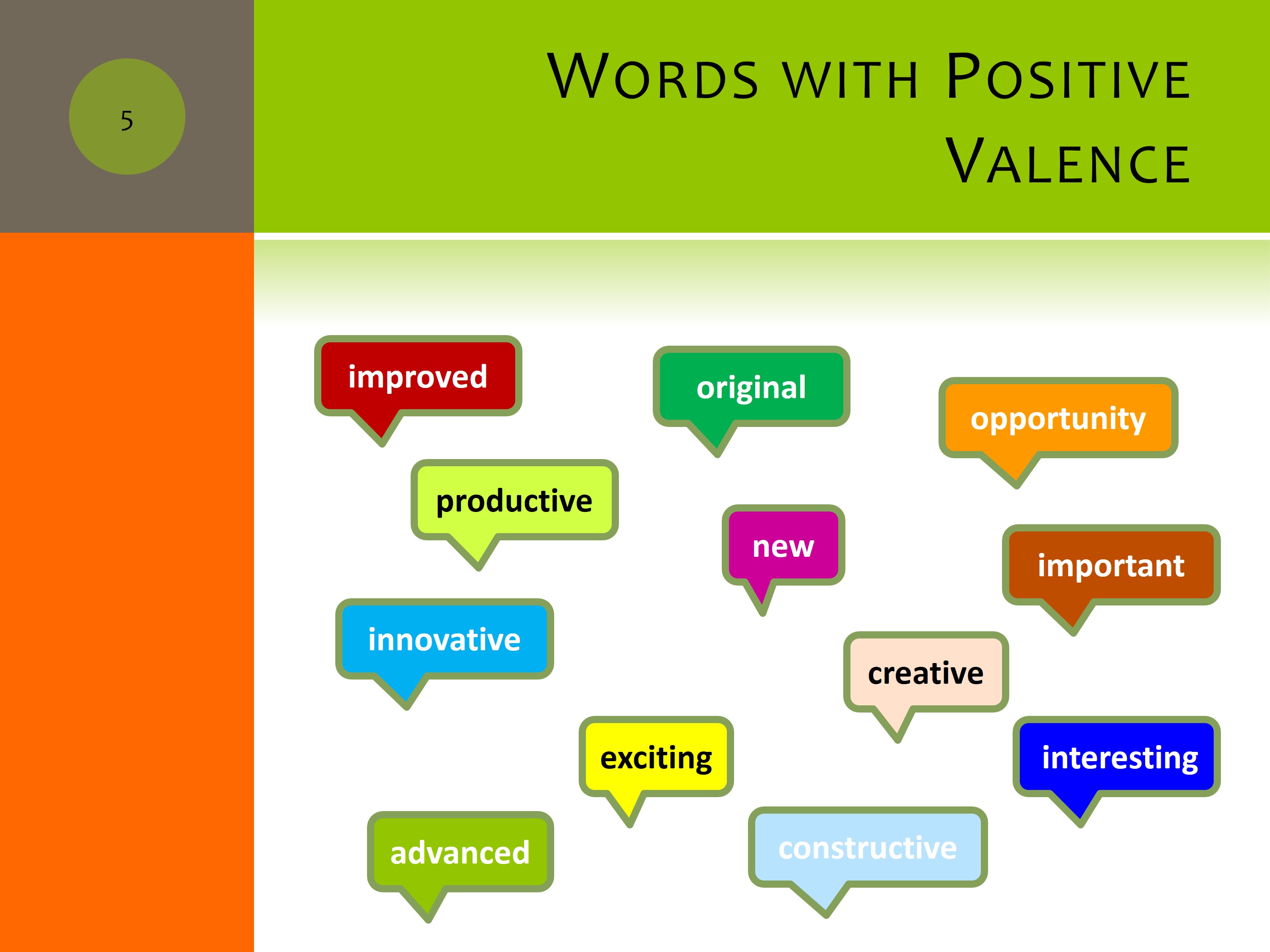

Words with Positive Valence

Here are some words with positive valence. Improved, original, opportunity, new, productive, innovative, exciting, creative, interesting, constructive, advanced, important, and you can probably think of a lot of other ones.

You can use these adjectives, but if what you’re proposing is not these things, it’s not going to do you any good. It really does have to be these things. But once you have that in your content and your proposal, this will help create a positive attitude.

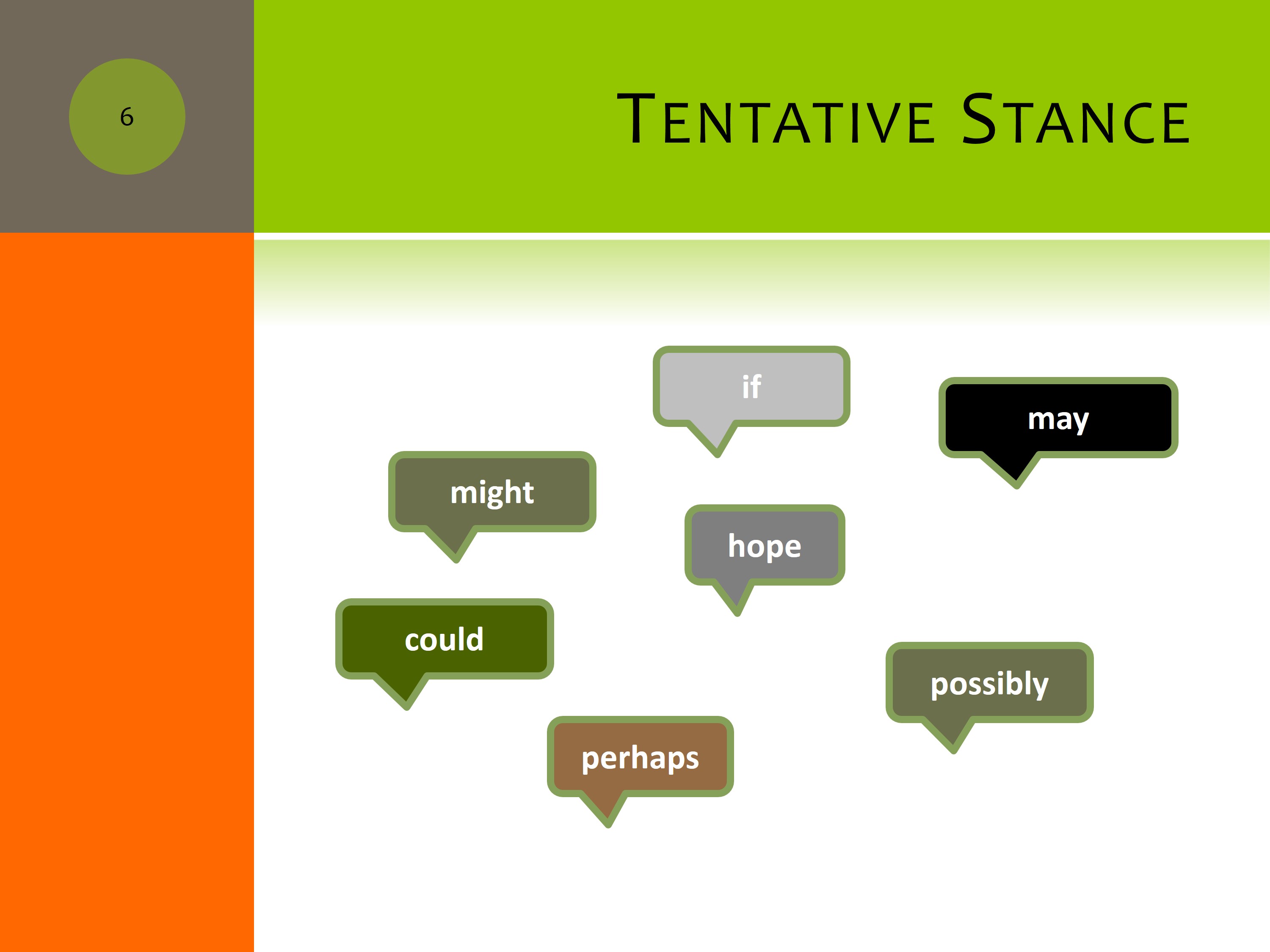

Tentative Stance

What are some words that convey a tentative stance? If. In science we use “if” statements a lot, but they shouldn’t be the kind of “if” statements that are casting doubt on whether something will turn out the way you think it will. You can use the word if for contingencies and cover both sides of the contingency, that’s important. But what you don’t want to do is raise a problem and not address it.

May — can you think of a replacement word for may?

Hope — we hope this happens. I’ve seen that in a lot of grant applications. Of course we hope it happens, but better not to say it that way.

Might — that’s another one, “it might.” In your grant application you want to plan for every contingency and let your reviewers know that you’ve thought through the different things that can happen and what you’ll do with each one of them. Same with “could.” It could happen, perhaps, possibly.

Do these words evoke a car sales ad to you? Do they make you feel like people can’t really say what this car will do for you, but it might do it, so we’re hedging our bets. You don’t want to hedge your bets in a grant application.

Vague Terminology

The thing and stuff words. Phrases like certain aspects — that’s not too specific. Some properties, a general outcome, the overall conceptualization, improved understanding, observed change, improved outlook. These might be big picture things that can happen, but when you start to use terms that aren’t real specific, it is good for you to think, “Is there something more specific I can say?”

Another recommendation we introduced last year was this book (Booth, Colomb, & Williams, 2008). You can look it up on Amazon if you’d like, but one way to start — or maybe to back up if you’re having trouble with that laser focus — would be to think about something like this. Can I say in a few short sentences what I’m trying to accomplish?

Here’s an example: A real quick description of your topic. Then can you explain what you think the theoretical significance of that would be? What would be the clinical significance? Is there a potential practical application? And why is it innovative?

If you can summarize what you’re trying to do starting with this kind of an organization, chances are you’re going to be able to expand it. As someone was saying yesterday, you really need to be able to present your program of research or grant in a 30-second bite, a 2-minute bite, and so on. This kind of thing will help you do that.

Telling the Story

Integrate Your Story into the Literature Review

Another important thing to do is to think about integrating a story into your grant application. As someone said yesterday, it should read like an action novel.

On one hand, we’re talking about wordsmithing and using good grantsmanship, and you’re getting the wording in there. But on the other hand, you really need a story to unfold. And like any good writer, you’re trying to combine these two things.

What is the story you want to tell about the problem?

What is the problem? Is it an interesting problem? Is it an important problem?

Where does that problem come from? Is it a theoretical problem that we don’t have a theory in a particular area? Or the theory has been stuck at this level of conceptualization for a period of time, and we could move beyond that to suggest new lines of research? Why is it important in your story that you’re telling in the grant?

What are the gaps in knowledge that you’re particularly interested in? You’re the hero of the story, right? Your solution to the problem is the “Aha. Here comes the main character.” You are the main character and you are solving the problem that you’ve had the opportunity to build credibility for in your background section.

Convey Significance with Context

You want to explain the problem, and what is known about the problem right now in this day and age. It’s important that you are backing this up with current research. That the reviewers know that you understand the breadth of research.

Contextualize what work you have done so far that is helping to build the story. It might be published research. It might be pilot data that you have. It might be part of your training even. It you’ve contributed in any way to this work, you certainly want to highlight that.

You want to propose the next step and tell why what you’re proposing is the next logical step. What do you want to do right now that’s important? You really need to situate your problem within a theoretical framework, or at least a model to show how you fit in with history, and how you’re part fits in with the longer-playing story.

Example Sentences: Significance

Here are a couple examples to highlight the gap in knowledge or barrier to progress.

In human subjects it is difficult to determine the links among physiology, vocal function measurement, and perceptual quality because it is not possible to systematically manipulate one and observe the effects on the other.

So can you pick out the gap or barrier to progress in this paragraph? The problem is it’s difficult to determine the links among physiology, vocal function measurement, and perceptual quality — and it says not only that it’s a problem, but explains quickly and concisely why it’s a problem. Then here comes the possible solution to the problem.

Computational and physical modeling are alternative methods for studying the links among physiology, vocal function measures, and perceptual quality.

And it describes it in a very short amount of space.

Here’s a significance statement.

The proposed research is significant because understanding how specific vocal fold asymmetries contribute to voice quality will lead to improved efficiency of evaluation and treatment of voice disorders that involve vibratory asymmetry.

There’s the word “significant” — you might even want to bold it — it explains clearly and concisely why this proposed research is significant. This is the kind of quote a reviewer can lift right out of your grant proposal and put it into the significance section of the review.

Here’s another significance statement from one of our proposals that combines both the theoretical and the clinical significance.

The theoretical and clinical significance accrued across these aims include (1) data-based comparisons of four theoretically-based WM models in children, (2) the development and testing of a new working-memory-based WL model in children, (3) establishing the relationship between WM and WL in monolingual English and bilingual Spanish-English speaking children compared to children with SLI, dyslexia and SLI/dyslexia, (4) a comprehensive description of between- and within-group WL differences in large, carefully selected typical and clinical groups and (5) the refinement of a working-memory-based WL battery for future theoretical and clinical research.

In this proposal, we listed four areas that we felt were contributing both theoretically and clinically to the research base. Then, we also highlighted the population we were going to include, because we thought that was innovative as well.

These studies address important problems in the fields of psychology, language sciences and education, including the need for comprehensive working memory and word learning batteries for children to support valid and reliable assessment and the need to understand deficits underlying poor word learning so that effective treatments can be developed. By completing this research we will advance scientific knowledge in working memory and word learning for monolingual and bilingual children with typical development and children with language impairment and significantly improve the methods for assessing working memory and word learning in school age children.

These studies address important problems — so you’re going to spell out for reviewers exactly what the important problems are and what fields they are likely to impact. That comes right out of the instructions about saying how you’re going to be addressing important problems. Also, we have these keywords, “will advance scientific knowledge” in these ways, and it will “significantly improve the methods” in these ways. If you can’t figure out how it will do it, the reviewers can’t figure out how it will do it. You need to figure it out yourself, ahead of time, and put it in your application.

Yesterday we discussed that innovation can be its own section. And some people do make it its own section with a header. But it’s also important to weave innovation and words around innovation throughout your whole application to create an overall positive representation of your work.

You want to use these key words in your application. Seeking to shift current paradigms or clinical practice. Great to put that word in your application. “The proposed work will shift current clinical practice of X by doing Y.” It takes one sentence.

What’s novel about your proposal? There are many different things that could be novel, and you should highlight each of them. The theoretical concept, your approach, your methodologies, the instrumentation or intervention you propose to use. It’s great if you can explain why what you’re proposing has an advantage over what’s currently being done. Sometimes just a refinement in a methodology is an important step forward. Sometimes there is something that has been very successful and well-tested, but you are proposing a very novel application — like the example Holly gave yesterday with a book reading intervention tried with typically developing children, but it’s never been tried with children with language impairment.

As you’re telling your story, weave in about innovation.

Things That Are Innovative

Here are some things that are innovative. A new theory or model. Different application of an existing theory. Bringing in a theory or model from another field that has particular application. Applying a normal theory to a disordered population. New and better experimental methods, better instrumentation, or new approaches to analysis.

Things That Are Not Innovative

Here are some things that are not innovative and all of us have to fight against them.

Using the technique of the day, and thinking everyone will be interested in it because it is the new hot thing to do. Collecting more data because it would be interesting to know about it. You have to be careful about that word “interesting.” That in and of itself is not innovative.

And the bane of our existence, conducting more research because “very little is known” about this thing. There might be a very good reason very little is known. Maybe nobody cares one bit about it, except for you. Remember you’re going to get a lot of money for this study, so it needs to be something that people care about.

Example Sentences: Innovation

Here are some lines out of different people’s grants with innovation statements. It seeks to “shift current working memory paradigms in children by testing …”, “shift current word learning paradigms by…”, “the proposed methodology goes beyond typical measures of word learning…”, “a novel word learning battery…”, “shift current research and clinical paradigms by studying large, diverse participant groups…”, it’s innovative because “our collaboration itself is innovative.”

What I’d like you to take a minute to do here is see if you can say, “my study is significant because…” and follow that with “my study is innovative because…”

I think a really hard part about this is being concise, and capturing the essence of what you’re doing. If you can’t capture the essence, often you haven’t got the essence yet. This is a good exercise for you — it’s a good exercise for me too.

More on Grantsmanship

A little more on grantsmanship. As I already said, use and highlight the words from the grant package and the scoring guide. You should have the scoring guide that the reviewers are using right there beside you when you write. Tape it up on the wall, put on your computer screen.

Don’t go down side roads. On many of the applications that I read when I review, you see that people have a love of many areas, but often the love of that area doesn’t feed directly into the purpose of the grant. It’s important — don’t let your train go down the dirt road. Stay on the track.

Have a careful, accurate review of the research, with an appropriate scope of research and citations. The reviewers know the literature quite well. If you haven’t done a good job with your literature search, and if you don’t have a command of the literature in the area, it will show.

And use positive valence words.

We talked about figures. Defining your terminology is really important. Don’t use acronyms. But when you’re using a term, make sure you’re defining how you’re using it, because different fields use the same term differently.

We talked about including white space.

The editing. I don’t know about you, but I really need to see it on paper to edit. How many of you that review print out grants? See — there are still four or five people who still print them out. Probably half the people in the room. You need to make sure that, if you’re a better editor on paper, go ahead and print it out and edit.

You should not have any typos or grammatical errors. Zero.

Questions and Discussion

I think we have a couple minutes if you have questions.

Question: How can we avoid “if” statements when we are not certain of the outcomes of our experiments?

I think there is a difference between your hypothesis testing — where you say that if it turns out this way, this is what it will add to our field, and if it turns out this way, it will do this — as opposed to building your story on a series of “ifs,” each one contingent on the other.

One of the things reviewers will always be concerned about is, for example, if the results of specific aim two are contingent on a certain outcome from specific aim one. Because if it doesn’t work, you’ve wasted money. If you write with a lot of if statements, it sets up that expectation. That’s different from hypothesis testing.

Question: My study is not an intervention study, it’s a basic science study. For the significance part, can I imply it is clinically important when it is not directly so for my study? If this is for the future, for long-term clinical importance can I mention this? Or, if it’s not specific, is it better to just not mention it?

My thought is that they are funding the work you are proposing now. That work needs to have impact. If it has impact ten years down the road, I don’t want to pay for that now. That’s my feeling.

Audience Discussion:

- I think what it doesn’t do, is it doesn’t use that space to really boost the feeling about your current work. If it has obvious clinical implications down the road, they’ll be fairly obvious. In my opinion, you would be better off to be really specific about the positive theoretical or scientific benefits of your proposed work right now. Often we can see clinical benefits down the road, but there are so many steps to get there that what we can’t see is the next critical, short-term step. Especially for an R03.

- I’m Dan Sklare from the NIDCD, I would add to what’s been said that you have the advantage, in a fellowship application, or a career award application, of demonstrating your vision five and ten years down the road. I think that showing the impact of a more fundamental study down the road to the field is going to be easier. Because you’re doing that within the context of tracking the vision of your own evolving research career. I think you’ve got a leg up in showing significance and impact.

- Also, don’t walk away with the impression that fundamental or basic science is in itself not innovative. It can be extremely innovative. Of course, its translatability and impact to the field is another issue. I would integrate the two, and I agree with the comments previously made about the importance of showing innovation even in a fellowship proposal.

Shelley I. Gray Arizona State University

Developed by Shelley Gray, Karen Kirk, and Bonnie Martin-Harris, with past input from Melanie Schuele, Kris Tjaden, Paul Abbas, Steven Barlow, Brenda Ryals, and Jack Jiang.

Presented at Lessons for Success (April 2014). Hosted by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Research Mentoring Network.

Lessons for Success is supported by Cooperative Agreement Conference Grant Award U13 DC007835 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and is co-sponsored by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Foundation (ASHFoundation).

Copyrighted Material. Reproduced by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association in the Clinical Research Education Library with permission from the author or presenter.

Clinical Research Education

More from the cred library, innovative treatments for persons with dementia, implementation science resources for crisp, when the ears interact with the brain, follow asha journals on twitter.

© 1997-2024 American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Privacy Notice Terms of Use

How To Write Significance of the Study (With Examples)

Whether you’re writing a research paper or thesis, a portion called Significance of the Study ensures your readers understand the impact of your work. Learn how to effectively write this vital part of your research paper or thesis through our detailed steps, guidelines, and examples.

Related: How to Write a Concept Paper for Academic Research

Table of Contents

What is the significance of the study.

The Significance of the Study presents the importance of your research. It allows you to prove the study’s impact on your field of research, the new knowledge it contributes, and the people who will benefit from it.

Related: How To Write Scope and Delimitation of a Research Paper (With Examples)

Where Should I Put the Significance of the Study?

The Significance of the Study is part of the first chapter or the Introduction. It comes after the research’s rationale, problem statement, and hypothesis.

Related: How to Make Conceptual Framework (with Examples and Templates)

Why Should I Include the Significance of the Study?

The purpose of the Significance of the Study is to give you space to explain to your readers how exactly your research will be contributing to the literature of the field you are studying 1 . It’s where you explain why your research is worth conducting and its significance to the community, the people, and various institutions.

How To Write Significance of the Study: 5 Steps

Below are the steps and guidelines for writing your research’s Significance of the Study.

1. Use Your Research Problem as a Starting Point

Your problem statement can provide clues to your research study’s outcome and who will benefit from it 2 .

Ask yourself, “How will the answers to my research problem be beneficial?”. In this manner, you will know how valuable it is to conduct your study.

Let’s say your research problem is “What is the level of effectiveness of the lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) in lowering the blood glucose level of Swiss mice (Mus musculus)?”

Discovering a positive correlation between the use of lemongrass and lower blood glucose level may lead to the following results:

- Increased public understanding of the plant’s medical properties;

- Higher appreciation of the importance of lemongrass by the community;

- Adoption of lemongrass tea as a cheap, readily available, and natural remedy to lower their blood glucose level.

Once you’ve zeroed in on the general benefits of your study, it’s time to break it down into specific beneficiaries.

2. State How Your Research Will Contribute to the Existing Literature in the Field

Think of the things that were not explored by previous studies. Then, write how your research tackles those unexplored areas. Through this, you can convince your readers that you are studying something new and adding value to the field.

3. Explain How Your Research Will Benefit Society

In this part, tell how your research will impact society. Think of how the results of your study will change something in your community.

For example, in the study about using lemongrass tea to lower blood glucose levels, you may indicate that through your research, the community will realize the significance of lemongrass and other herbal plants. As a result, the community will be encouraged to promote the cultivation and use of medicinal plants.

4. Mention the Specific Persons or Institutions Who Will Benefit From Your Study

Using the same example above, you may indicate that this research’s results will benefit those seeking an alternative supplement to prevent high blood glucose levels.

5. Indicate How Your Study May Help Future Studies in the Field

You must also specifically indicate how your research will be part of the literature of your field and how it will benefit future researchers. In our example above, you may indicate that through the data and analysis your research will provide, future researchers may explore other capabilities of herbal plants in preventing different diseases.

Tips and Warnings

- Think ahead . By visualizing your study in its complete form, it will be easier for you to connect the dots and identify the beneficiaries of your research.

- Write concisely. Make it straightforward, clear, and easy to understand so that the readers will appreciate the benefits of your research. Avoid making it too long and wordy.

- Go from general to specific . Like an inverted pyramid, you start from above by discussing the general contribution of your study and become more specific as you go along. For instance, if your research is about the effect of remote learning setup on the mental health of college students of a specific university , you may start by discussing the benefits of the research to society, to the educational institution, to the learning facilitators, and finally, to the students.

- Seek help . For example, you may ask your research adviser for insights on how your research may contribute to the existing literature. If you ask the right questions, your research adviser can point you in the right direction.

- Revise, revise, revise. Be ready to apply necessary changes to your research on the fly. Unexpected things require adaptability, whether it’s the respondents or variables involved in your study. There’s always room for improvement, so never assume your work is done until you have reached the finish line.

Significance of the Study Examples

This section presents examples of the Significance of the Study using the steps and guidelines presented above.

Example 1: STEM-Related Research

Research Topic: Level of Effectiveness of the Lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ) Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice ( Mus musculus ).

Significance of the Study .

This research will provide new insights into the medicinal benefit of lemongrass ( Cymbopogon citratus ), specifically on its hypoglycemic ability.

Through this research, the community will further realize promoting medicinal plants, especially lemongrass, as a preventive measure against various diseases. People and medical institutions may also consider lemongrass tea as an alternative supplement against hyperglycemia.

Moreover, the analysis presented in this study will convey valuable information for future research exploring the medicinal benefits of lemongrass and other medicinal plants.

Example 2: Business and Management-Related Research

Research Topic: A Comparative Analysis of Traditional and Social Media Marketing of Small Clothing Enterprises.

Significance of the Study:

By comparing the two marketing strategies presented by this research, there will be an expansion on the current understanding of the firms on these marketing strategies in terms of cost, acceptability, and sustainability. This study presents these marketing strategies for small clothing enterprises, giving them insights into which method is more appropriate and valuable for them.

Specifically, this research will benefit start-up clothing enterprises in deciding which marketing strategy they should employ. Long-time clothing enterprises may also consider the result of this research to review their current marketing strategy.

Furthermore, a detailed presentation on the comparison of the marketing strategies involved in this research may serve as a tool for further studies to innovate the current method employed in the clothing Industry.

Example 3: Social Science -Related Research.

Research Topic: Divide Et Impera : An Overview of How the Divide-and-Conquer Strategy Prevailed on Philippine Political History.

Significance of the Study :

Through the comprehensive exploration of this study on Philippine political history, the influence of the Divide et Impera, or political decentralization, on the political discernment across the history of the Philippines will be unraveled, emphasized, and scrutinized. Moreover, this research will elucidate how this principle prevailed until the current political theatre of the Philippines.

In this regard, this study will give awareness to society on how this principle might affect the current political context. Moreover, through the analysis made by this study, political entities and institutions will have a new approach to how to deal with this principle by learning about its influence in the past.

In addition, the overview presented in this research will push for new paradigms, which will be helpful for future discussion of the Divide et Impera principle and may lead to a more in-depth analysis.

Example 4: Humanities-Related Research

Research Topic: Effectiveness of Meditation on Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students.

Significance of the Study:

This research will provide new perspectives in approaching anxiety issues of college students through meditation.

Specifically, this research will benefit the following:

Community – this study spreads awareness on recognizing anxiety as a mental health concern and how meditation can be a valuable approach to alleviating it.

Academic Institutions and Administrators – through this research, educational institutions and administrators may promote programs and advocacies regarding meditation to help students deal with their anxiety issues.

Mental health advocates – the result of this research will provide valuable information for the advocates to further their campaign on spreading awareness on dealing with various mental health issues, including anxiety, and how to stop stigmatizing those with mental health disorders.

Parents – this research may convince parents to consider programs involving meditation that may help the students deal with their anxiety issues.

Students will benefit directly from this research as its findings may encourage them to consider meditation to lower anxiety levels.

Future researchers – this study covers information involving meditation as an approach to reducing anxiety levels. Thus, the result of this study can be used for future discussions on the capabilities of meditation in alleviating other mental health concerns.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what is the difference between the significance of the study and the rationale of the study.

Both aim to justify the conduct of the research. However, the Significance of the Study focuses on the specific benefits of your research in the field, society, and various people and institutions. On the other hand, the Rationale of the Study gives context on why the researcher initiated the conduct of the study.

Let’s take the research about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing Anxiety Levels of College Students as an example. Suppose you are writing about the Significance of the Study. In that case, you must explain how your research will help society, the academic institution, and students deal with anxiety issues through meditation. Meanwhile, for the Rationale of the Study, you may state that due to the prevalence of anxiety attacks among college students, you’ve decided to make it the focal point of your research work.

2. What is the difference between Justification and the Significance of the Study?

In Justification, you express the logical reasoning behind the conduct of the study. On the other hand, the Significance of the Study aims to present to your readers the specific benefits your research will contribute to the field you are studying, community, people, and institutions.

Suppose again that your research is about the Effectiveness of Meditation in Reducing the Anxiety Levels of College Students. Suppose you are writing the Significance of the Study. In that case, you may state that your research will provide new insights and evidence regarding meditation’s ability to reduce college students’ anxiety levels. Meanwhile, you may note in the Justification that studies are saying how people used meditation in dealing with their mental health concerns. You may also indicate how meditation is a feasible approach to managing anxiety using the analysis presented by previous literature.

3. How should I start my research’s Significance of the Study section?

– This research will contribute… – The findings of this research… – This study aims to… – This study will provide… – Through the analysis presented in this study… – This study will benefit…

Moreover, you may start the Significance of the Study by elaborating on the contribution of your research in the field you are studying.

4. What is the difference between the Purpose of the Study and the Significance of the Study?

The Purpose of the Study focuses on why your research was conducted, while the Significance of the Study tells how the results of your research will benefit anyone.

Suppose your research is about the Effectiveness of Lemongrass Tea in Lowering the Blood Glucose Level of Swiss Mice . You may include in your Significance of the Study that the research results will provide new information and analysis on the medical ability of lemongrass to solve hyperglycemia. Meanwhile, you may include in your Purpose of the Study that your research wants to provide a cheaper and natural way to lower blood glucose levels since commercial supplements are expensive.

5. What is the Significance of the Study in Tagalog?

In Filipino research, the Significance of the Study is referred to as Kahalagahan ng Pag-aaral.

- Draft your Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from http://dissertationedd.usc.edu/draft-your-significance-of-the-study.html

- Regoniel, P. (2015). Two Tips on How to Write the Significance of the Study. Retrieved 18 April 2021, from https://simplyeducate.me/2015/02/09/significance-of-the-study/

Written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

in Career and Education , Juander How

Jewel Kyle Fabula

Jewel Kyle Fabula is a Bachelor of Science in Economics student at the University of the Philippines Diliman. His passion for learning mathematics developed as he competed in some mathematics competitions during his Junior High School years. He loves cats, playing video games, and listening to music.

Browse all articles written by Jewel Kyle Fabula

Copyright Notice

All materials contained on this site are protected by the Republic of the Philippines copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published, or broadcast without the prior written permission of filipiknow.net or in the case of third party materials, the owner of that content. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright, or other notice from copies of the content. Be warned that we have already reported and helped terminate several websites and YouTube channels for blatantly stealing our content. If you wish to use filipiknow.net content for commercial purposes, such as for content syndication, etc., please contact us at legal(at)filipiknow(dot)net

How To Write a Significance Statement for Your Research

A significance statement is an essential part of a research paper. It explains the importance and relevance of the study to the academic community and the world at large. To write a compelling significance statement, identify the research problem, explain why it is significant, provide evidence of its importance, and highlight its potential impact on future research, policy, or practice. A well-crafted significance statement should effectively communicate the value of the research to readers and help them understand why it matters.

Updated on May 4, 2023

A significance statement is a clearly stated, non-technical paragraph that explains why your research matters. It’s central in making the public aware of and gaining support for your research.

Write it in jargon-free language that a reader from any field can understand. Well-crafted, easily readable significance statements can improve your chances for citation and impact and make it easier for readers outside your field to find and understand your work.

Read on for more details on what a significance statement is, how it can enhance the impact of your research, and, of course, how to write one.

What is a significance statement in research?

A significance statement answers the question: How will your research advance scientific knowledge and impact society at large (as well as specific populations)?

You might also see it called a “Significance of the study” statement. Some professional organizations in the STEM sciences and social sciences now recommended that journals in their disciplines make such statements a standard feature of each published article. Funding agencies also consider “significance” a key criterion for their awards.

Read some examples of significance statements from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) here .

Depending upon the specific journal or funding agency’s requirements, your statement may be around 100 words and answer these questions:

1. What’s the purpose of this research?

2. What are its key findings?

3. Why do they matter?

4. Who benefits from the research results?

Readers will want to know: “What is interesting or important about this research?” Keep asking yourself that question.

Where to place the significance statement in your manuscript

Most journals ask you to place the significance statement before or after the abstract, so check with each journal’s guide.

This article is focused on the formal significance statement, even though you’ll naturally highlight your project’s significance elsewhere in your manuscript. (In the introduction, you’ll set out your research aims, and in the conclusion, you’ll explain the potential applications of your research and recommend areas for future research. You’re building an overall case for the value of your work.)

Developing the significance statement

The main steps in planning and developing your statement are to assess the gaps to which your study contributes, and then define your work’s implications and impact.

Identify what gaps your study fills and what it contributes

Your literature review was a big part of how you planned your study. To develop your research aims and objectives, you identified gaps or unanswered questions in the preceding research and designed your study to address them.

Go back to that lit review and look at those gaps again. Review your research proposal to refresh your memory. Ask:

- How have my research findings advanced knowledge or provided notable new insights?

- How has my research helped to prove (or disprove) a hypothesis or answer a research question?

- Why are those results important?

Consider your study’s potential impact at two levels:

- What contribution does my research make to my field?

- How does it specifically contribute to knowledge; that is, who will benefit the most from it?

Define the implications and potential impact

As you make notes, keep the reasons in mind for why you are writing this statement. Whom will it impact, and why?

The first audience for your significance statement will be journal reviewers when you submit your article for publishing. Many journals require one for manuscript submissions. Study the author’s guide of your desired journal to see its criteria ( here’s an example ). Peer reviewers who can clearly understand the value of your research will be more likely to recommend publication.

Second, when you apply for funding, your significance statement will help justify why your research deserves a grant from a funding agency . The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), for example, wants to see that a project will “exert a sustained, powerful influence on the research field(s) involved.” Clear, simple language is always valuable because not all reviewers will be specialists in your field.

Third, this concise statement about your study’s importance can affect how potential readers engage with your work. Science journalists and interested readers can promote and spread your work, enhancing your reputation and influence. Help them understand your work.

You’re now ready to express the importance of your research clearly and concisely. Time to start writing.

How to write a significance statement: Key elements

When drafting your statement, focus on both the content and writing style.

- In terms of content, emphasize the importance, timeliness, and relevance of your research results.

- Write the statement in plain, clear language rather than scientific or technical jargon. Your audience will include not just your fellow scientists but also non-specialists like journalists, funding reviewers, and members of the public.

Follow the process we outline below to build a solid, well-crafted, and informative statement.

Get started

Some suggested opening lines to help you get started might be:

- The implications of this study are…

- Building upon previous contributions, our study moves the field forward because…

- Our study furthers previous understanding about…

Alternatively, you may start with a statement about the phenomenon you’re studying, leading to the problem statement.

Include these components

Next, draft some sentences that include the following elements. A good example, which we’ll use here, is a significance statement by Rogers et al. (2022) published in the Journal of Climate .

1. Briefly situate your research study in its larger context . Start by introducing the topic, leading to a problem statement. Here’s an example:

‘Heatwaves pose a major threat to human health, ecosystems, and human systems.”

2. State the research problem.

“Simultaneous heatwaves affecting multiple regions can exacerbate such threats. For example, multiple food-producing regions simultaneously undergoing heat-related crop damage could drive global food shortages.”

3. Tell what your study does to address it.

“We assess recent changes in the occurrence of simultaneous large heatwaves.”

4. Provide brief but powerful evidence to support the claims your statement is making , Use quantifiable terms rather than vague ones (e.g., instead of “This phenomenon is happening now more than ever,” see below how Rogers et al. (2022) explained it). This evidence intensifies and illustrates the problem more vividly:

“Such simultaneous heatwaves are 7 times more likely now than 40 years ago. They are also hotter and affect a larger area. Their increasing occurrence is mainly driven by warming baseline temperatures due to global heating, but changes in weather patterns contribute to disproportionate increases over parts of Europe, the eastern United States, and Asia.

5. Relate your study’s impact to the broader context , starting with its general significance to society—then, when possible, move to the particular as you name specific applications of your research findings. (Our example lacks this second level of application.)

“Better understanding the drivers of weather pattern changes is therefore important for understanding future concurrent heatwave characteristics and their impacts.”

Refine your English

Don’t understate or overstate your findings – just make clear what your study contributes. When you have all the elements in place, review your draft to simplify and polish your language. Even better, get an expert AJE edit . Be sure to use “plain” language rather than academic jargon.

- Avoid acronyms, scientific jargon, and technical terms

- Use active verbs in your sentence structure rather than passive voice (e.g., instead of “It was found that...”, use “We found...”)

- Make sentence structures short, easy to understand – readable

- Try to address only one idea in each sentence and keep sentences within 25 words (15 words is even better)

- Eliminate nonessential words and phrases (“fluff” and wordiness)

Enhance your significance statement’s impact

Always take time to review your draft multiple times. Make sure that you:

- Keep your language focused

- Provide evidence to support your claims

- Relate the significance to the broader research context in your field

After revising your significance statement, request feedback from a reading mentor about how to make it even clearer. If you’re not a native English speaker, seek help from a native-English-speaking colleague or use an editing service like AJE to make sure your work is at a native level.

Understanding the significance of your study

Your readers may have much less interest than you do in the specific details of your research methods and measures. Many readers will scan your article to learn how your findings might apply to them and their own research.

Different types of significance

Your findings may have different types of significance, relevant to different populations or fields of study for different reasons. You can emphasize your work’s statistical, clinical, or practical significance. Editors or reviewers in the social sciences might also evaluate your work’s social or political significance.

Statistical significance means that the results are unlikely to have occurred randomly. Instead, it implies a true cause-and-effect relationship.

Clinical significance means that your findings are applicable for treating patients and improving quality of life.

Practical significance is when your research outcomes are meaningful to society at large, in the “real world.” Practical significance is usually measured by the study’s effect size . Similarly, evaluators may attribute social or political significance to research that addresses “real and immediate” social problems.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

The Savvy Scientist

Experiences of a London PhD student and beyond

What is the Significance of a Study? Examples and Guide

If you’re reading this post you’re probably wondering: what is the significance of a study?

No matter where you’re at with a piece of research, it is a good idea to think about the potential significance of your work. And sometimes you’ll have to explicitly write a statement of significance in your papers, it addition to it forming part of your thesis.

In this post I’ll cover what the significance of a study is, how to measure it, how to describe it with examples and add in some of my own experiences having now worked in research for over nine years.

If you’re reading this because you’re writing up your first paper, welcome! You may also like my how-to guide for all aspects of writing your first research paper .

Looking for guidance on writing the statement of significance for a paper or thesis? Click here to skip straight to that section.

What is the Significance of a Study?

For research papers, theses or dissertations it’s common to explicitly write a section describing the significance of the study. We’ll come onto what to include in that section in just a moment.

However the significance of a study can actually refer to several different things.

Working our way from the most technical to the broadest, depending on the context, the significance of a study may refer to:

- Within your study: Statistical significance. Can we trust the findings?

- Wider research field: Research significance. How does your study progress the field?

- Commercial / economic significance: Could there be business opportunities for your findings?

- Societal significance: What impact could your study have on the wider society.

- And probably other domain-specific significance!

We’ll shortly cover each of them in turn, including how they’re measured and some examples for each type of study significance.

But first, let’s touch on why you should consider the significance of your research at an early stage.

Why Care About the Significance of a Study?

No matter what is motivating you to carry out your research, it is sensible to think about the potential significance of your work. In the broadest sense this asks, how does the study contribute to the world?

After all, for many people research is only worth doing if it will result in some expected significance. For the vast majority of us our studies won’t be significant enough to reach the evening news, but most studies will help to enhance knowledge in a particular field and when research has at least some significance it makes for a far more fulfilling longterm pursuit.

Furthermore, a lot of us are carrying out research funded by the public. It therefore makes sense to keep an eye on what benefits the work could bring to the wider community.

Often in research you’ll come to a crossroads where you must decide which path of research to pursue. Thinking about the potential benefits of a strand of research can be useful for deciding how to spend your time, money and resources.

It’s worth noting though, that not all research activities have to work towards obvious significance. This is especially true while you’re a PhD student, where you’re figuring out what you enjoy and may simply be looking for an opportunity to learn a new skill.

However, if you’re trying to decide between two potential projects, it can be useful to weigh up the potential significance of each.

Let’s now dive into the different types of significance, starting with research significance.

Research Significance

What is the research significance of a study.

Unless someone specifies which type of significance they’re referring to, it is fair to assume that they want to know about the research significance of your study.

Research significance describes how your work has contributed to the field, how it could inform future studies and progress research.

Where should I write about my study’s significance in my thesis?

Typically you should write about your study’s significance in the Introduction and Conclusions sections of your thesis.

It’s important to mention it in the Introduction so that the relevance of your work and the potential impact and benefits it could have on the field are immediately apparent. Explaining why your work matters will help to engage readers (and examiners!) early on.

It’s also a good idea to detail the study’s significance in your Conclusions section. This adds weight to your findings and helps explain what your study contributes to the field.

On occasion you may also choose to include a brief description in your Abstract.

What is expected when submitting an article to a journal

It is common for journals to request a statement of significance, although this can sometimes be called other things such as:

- Impact statement

- Significance statement

- Advances in knowledge section

Here is one such example of what is expected:

Impact Statement: An Impact Statement is required for all submissions. Your impact statement will be evaluated by the Editor-in-Chief, Global Editors, and appropriate Associate Editor. For your manuscript to receive full review, the editors must be convinced that it is an important advance in for the field. The Impact Statement is not a restating of the abstract. It should address the following: Why is the work submitted important to the field? How does the work submitted advance the field? What new information does this work impart to the field? How does this new information impact the field? Experimental Biology and Medicine journal, author guidelines

Typically the impact statement will be shorter than the Abstract, around 150 words.

Defining the study’s significance is helpful not just for the impact statement (if the journal asks for one) but also for building a more compelling argument throughout your submission. For instance, usually you’ll start the Discussion section of a paper by highlighting the research significance of your work. You’ll also include a short description in your Abstract too.

How to describe the research significance of a study, with examples

Whether you’re writing a thesis or a journal article, the approach to writing about the significance of a study are broadly the same.

I’d therefore suggest using the questions above as a starting point to base your statements on.

- Why is the work submitted important to the field?

- How does the work submitted advance the field?

- What new information does this work impart to the field?

- How does this new information impact the field?

Answer those questions and you’ll have a much clearer idea of the research significance of your work.

When describing it, try to clearly state what is novel about your study’s contribution to the literature. Then go on to discuss what impact it could have on progressing the field along with recommendations for future work.

Potential sentence starters

If you’re not sure where to start, why not set a 10 minute timer and have a go at trying to finish a few of the following sentences. Not sure on what to put? Have a chat to your supervisor or lab mates and they may be able to suggest some ideas.

- This study is important to the field because…

- These findings advance the field by…

- Our results highlight the importance of…

- Our discoveries impact the field by…

Now you’ve had a go let’s have a look at some real life examples.

Statement of significance examples

A statement of significance / impact:

Impact Statement This review highlights the historical development of the concept of “ideal protein” that began in the 1950s and 1980s for poultry and swine diets, respectively, and the major conceptual deficiencies of the long-standing concept of “ideal protein” in animal nutrition based on recent advances in amino acid (AA) metabolism and functions. Nutritionists should move beyond the “ideal protein” concept to consider optimum ratios and amounts of all proteinogenic AAs in animal foods and, in the case of carnivores, also taurine. This will help formulate effective low-protein diets for livestock, poultry, and fish, while sustaining global animal production. Because they are not only species of agricultural importance, but also useful models to study the biology and diseases of humans as well as companion (e.g. dogs and cats), zoo, and extinct animals in the world, our work applies to a more general readership than the nutritionists and producers of farm animals. Wu G, Li P. The “ideal protein” concept is not ideal in animal nutrition. Experimental Biology and Medicine . 2022;247(13):1191-1201. doi: 10.1177/15353702221082658

And the same type of section but this time called “Advances in knowledge”:

Advances in knowledge: According to the MY-RADs criteria, size measurements of focal lesions in MRI are now of relevance for response assessment in patients with monoclonal plasma cell disorders. Size changes of 1 or 2 mm are frequently observed due to uncertainty of the measurement only, while the actual focal lesion has not undergone any biological change. Size changes of at least 6 mm or more in T 1 weighted or T 2 weighted short tau inversion recovery sequences occur in only 5% or less of cases when the focal lesion has not undergone any biological change. Wennmann M, Grözinger M, Weru V, et al. Test-retest, inter- and intra-rater reproducibility of size measurements of focal bone marrow lesions in MRI in patients with multiple myeloma [published online ahead of print, 2023 Apr 12]. Br J Radiol . 2023;20220745. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20220745

Other examples of research significance

Moving beyond the formal statement of significance, here is how you can describe research significance more broadly within your paper.

Describing research impact in an Abstract of a paper:

Three-dimensional visualisation and quantification of the chondrocyte population within articular cartilage can be achieved across a field of view of several millimetres using laboratory-based micro-CT. The ability to map chondrocytes in 3D opens possibilities for research in fields from skeletal development through to medical device design and treatment of cartilage degeneration. Conclusions section of the abstract in my first paper .

In the Discussion section of a paper:

We report for the utility of a standard laboratory micro-CT scanner to visualise and quantify features of the chondrocyte population within intact articular cartilage in 3D. This study represents a complimentary addition to the growing body of evidence supporting the non-destructive imaging of the constituents of articular cartilage. This offers researchers the opportunity to image chondrocyte distributions in 3D without specialised synchrotron equipment, enabling investigations such as chondrocyte morphology across grades of cartilage damage, 3D strain mapping techniques such as digital volume correlation to evaluate mechanical properties in situ , and models for 3D finite element analysis in silico simulations. This enables an objective quantification of chondrocyte distribution and morphology in three dimensions allowing greater insight for investigations into studies of cartilage development, degeneration and repair. One such application of our method, is as a means to provide a 3D pattern in the cartilage which, when combined with digital volume correlation, could determine 3D strain gradient measurements enabling potential treatment and repair of cartilage degeneration. Moreover, the method proposed here will allow evaluation of cartilage implanted with tissue engineered scaffolds designed to promote chondral repair, providing valuable insight into the induced regenerative process. The Discussion section of the paper is laced with references to research significance.

How is longer term research significance measured?

Looking beyond writing impact statements within papers, sometimes you’ll want to quantify the long term research significance of your work. For instance when applying for jobs.

The most obvious measure of a study’s long term research significance is the number of citations it receives from future publications. The thinking is that a study which receives more citations will have had more research impact, and therefore significance , than a study which received less citations. Citations can give a broad indication of how useful the work is to other researchers but citations aren’t really a good measure of significance.

Bear in mind that us researchers can be lazy folks and sometimes are simply looking to cite the first paper which backs up one of our claims. You can find studies which receive a lot of citations simply for packaging up the obvious in a form which can be easily found and referenced, for instance by having a catchy or optimised title.

Likewise, research activity varies wildly between fields. Therefore a certain study may have had a big impact on a particular field but receive a modest number of citations, simply because not many other researchers are working in the field.

Nevertheless, citations are a standard measure of significance and for better or worse it remains impressive for someone to be the first author of a publication receiving lots of citations.

Other measures for the research significance of a study include:

- Accolades: best paper awards at conferences, thesis awards, “most downloaded” titles for articles, press coverage.

- How much follow-on research the study creates. For instance, part of my PhD involved a novel material initially developed by another PhD student in the lab. That PhD student’s research had unlocked lots of potential new studies and now lots of people in the group were using the same material and developing it for different applications. The initial study may not receive a high number of citations yet long term it generated a lot of research activity.

That covers research significance, but you’ll often want to consider other types of significance for your study and we’ll cover those next.

Statistical Significance

What is the statistical significance of a study.

Often as part of a study you’ll carry out statistical tests and then state the statistical significance of your findings: think p-values eg <0.05. It is useful to describe the outcome of these tests within your report or paper, to give a measure of statistical significance.

Effectively you are trying to show whether the performance of your innovation is actually better than a control or baseline and not just chance. Statistical significance deserves a whole other post so I won’t go into a huge amount of depth here.

Things that make publication in The BMJ impossible or unlikely Internal validity/robustness of the study • It had insufficient statistical power, making interpretation difficult; • Lack of statistical power; The British Medical Journal’s guide for authors

Calculating statistical significance isn’t always necessary (or valid) for a study, such as if you have a very small number of samples, but it is a very common requirement for scientific articles.

Writing a journal article? Check the journal’s guide for authors to see what they expect. Generally if you have approximately five or more samples or replicates it makes sense to start thinking about statistical tests. Speak to your supervisor and lab mates for advice, and look at other published articles in your field.

How is statistical significance measured?

Statistical significance is quantified using p-values . Depending on your study design you’ll choose different statistical tests to compute the p-value.

A p-value of 0.05 is a common threshold value. The 0.05 means that there is a 1/20 chance that the difference in performance you’re reporting is just down to random chance.

- p-values above 0.05 mean that the result isn’t statistically significant enough to be trusted: it is too likely that the effect you’re showing is just luck.

- p-values less than or equal to 0.05 mean that the result is statistically significant. In other words: unlikely to just be chance, which is usually considered a good outcome.

Low p-values (eg p = 0.001) mean that it is highly unlikely to be random chance (1/1000 in the case of p = 0.001), therefore more statistically significant.

It is important to clarify that, although low p-values mean that your findings are statistically significant, it doesn’t automatically mean that the result is scientifically important. More on that in the next section on research significance.

How to describe the statistical significance of your study, with examples