- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2024

Trends in socio-demographic characteristics and substance use among high school learners in a selected district in Limpopo Province, South Africa

- Linda Shuro 1 &

- Firdouza Waggie 2

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1407 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

868 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Substance use is an escalating public health problem in South Africa resulting in risky behaviours and poor educational attainment among adolescents. There is a huge battle to overcome substance use among learners as more drugs become easily available with the mean age of drug experimentation reported to be at 12 years of age. It is important to continuously understand the trends in substance use in order to assess if there are positive changes and provide evidence for the development of context-specific effective interventions. This paper outlines the prevalence of substance use among selected high schools in a district in Limpopo province.

To determine the prevalence of substance use among selected high school learners in a district in Limpopo Province, a cross-sectional school survey of 768 learners was conducted. Data was analysed using SPSS v 26. Descriptive analysis was used to describe the independent and dependent variables and Chi-Square test was used to investigate associations between demographic characteristics and substance use among high school learners.

The most abused substances by learners were alcohol (49%), cigarettes (20.8%) and marijuana (dagga/cannabis) (16.8%). In a lifetime, there was a significant difference ( P < 0.05) in cigarette smoking with gender, school, and grade; with more use in males (14.2%) than females (7.6%); in urban schools (14.6) than peri-urban (6.7%) and more in Grade 12 (6.4%). There was a significant difference ( P < 0.05) in alcohol use with more use in Grade 10 (12.6%) and varied use among male and female learners but cumulatively more alcohol use in females (27.7%). Drug use varied, with an overall high drug use in urban schools (20.7%).

Conclusions

Substance use is rife among high school learners in the district and health promotion initiatives need to be tailored within the context of socio-demographic characteristics of learners including the multiple levels of influence such as peer pressure, poverty, unemployment and child headed families. Additional research is required to investigate the factors leading to a notable gradual increase in use among female learners and into the environmental and family settings of learners in influencing substance use.

Peer Review reports

Substance use and abuse is a major public health concern among female and male adolescents with prevalence varying in different contexts. Drug consumption in South Africa is twice the global average [ 1 ]. South Africa is ranked in the top 10 narcotics and alcohol abusers in the world. For every 100 people, 15 have a drug problem and for every 100 Rands in circulation, 25 Rands is linked to substance use [ 2 ]. Many schools in South Africa continue to battle with the problem of substance use among learners. The most experimented substances by adolescents in South Africa is tobacco and alcohol [ 3 ]. A majority of these adolescents are found in schools. The use of substances at an early age, especially among learners results in negative health and social outcomes such as school dropouts, and early onset of sexual behavior which may lead to teenage pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections [ 4 , 5 ]. A review of studies on impact of substance use on school performance and public health indicate that use of substances is significantly associated with negative school outcomes such as truancy, low motivation to learn, regular sickness, increasing school abstenteeism, decreasing marks and high chances of skipping school [ 6 , 7 , 8 ].

The mean age of drug experimentation in South Africa is 12 years and this is rapidly decreasing [ 9 ]. Globally 1 in 4 learners (13–15 years old) had their first smoke before the age of 10 and the percentage of use is greater than 10% for any tobacco product by 13-15-year-old learners [ 10 ]. The increased availability and variety of drugs available to South African teenagers is a cause for alarm, for example, marijuana (known as dagga/cannabis), cocaine, glue, methamphetamine known as TIK and whoonga known as “nyaope”-a street name for a mixture of mainly dagga and low-grade heroin [ 11 ]. South Africa is also experiencing an up rise in drugs and gangsterism labelled the “twin evils of our time”, especially found among youth in previously marginalized communities. The problem is viewed as an indication of the many socio-economic challenges faced by working class communities [ 12 ].

Global initiatives such as the WHO Global School Health initiative promote health promoting schools (HPS) to improve the health of the school community. An HPS is a “school constantly strengthening its capacity as a healthy setting for living, learning and working” [ 13 ]. The HPS approach was implemented in South Africa in 1994 in efforts to redress inequalities created during apartheid in the education and health sector and also the policy context was favourable for its acceptance [ 14 ]. There are many public health initiatives to address health issues among adolescents in South Africa which are integrated as part of the current health reforms such as re-engineering primary health care, National Drug Master Plan 2013–2017 [ 15 ] and the revised Integrated School Health Policy (ISHP). With a focus on school health, the ISHP was launched in 2012, as a collaboration between the Department of Health (DoH) and the Department of Basic Education (DBE) [ 16 ] as a framework for the new school health programme (grade 0 to 12 learners), implemented at sub-district level. It is therefore invested at the primary level and aligned to several government commitments such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and Bill of Rights of the South African Constitution [ 17 ]. The above initiatives require a more integrated approach for effective change and to address the social determinants of substance use among learners [ 18 ].

Schools in Limpopo face multiple social challenges that affect effective teaching and learning such as crime and violence, sexual assault/abuse, substance use and bullying [ 19 ]. There was a recent outcry for action by learners to the Education Member of Executive Council (MEC) to address these social challenges [ 20 ]. A review of prevalence studies [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ] in Limpopo high schools shows that male learners abuse drugs more than female learners. The review also showed past month low prevalence rates in rural high schools but with progression of studies and lifetime use, a gradual increase in prevalence rates in schools was noted. Some of the contributing factors to substance use noted include more access to finances by the males, the presence of liquor stores near the learners’ homes; certain demographic characteristics such as being male, urban versus rural learners; substance use among parents and friends. The major determinants of alcohol use found in students include, “gender, age, ever having smoked a cigarette, ever damaged property, walking home alone at night, easy availability of alcohol, thinking alcohol use was wrong, attending religious services and number of friends who used alcohol” [ 21 ]. A similar study identified the following five community level factors linked to use of home prepared alcohol by learners: i) subjective adult norms around substance use in the community, ii) negative opinions about one’s neighbourhood, iii) perceived levels of adult antisocial behavior in the community, iv) community affirmations of adolescents, and v) perceived levels of crime and violence in the community (derelict neighbourhood)” [ 26 ]. In one district in Limpopo, learners identified alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, petrol, glue and jeyes fluid mixed with spirit as the commonly used substances and other learners experimented on heroin and cannabis as they had friends with access to the drugs in town [ 27 ] which is consistent with other studies [ 28 , 29 ]. Youth in Limpopo are engaged in different substances (tobacco, alcohol, hard core drugs) with cannabis, inhalants, bottled wine, home, and commercially brewed beer as commonly abused substances [ 30 ]. This highlights the need for more monitoring studies to review the escalating situation of substance use among learners to create a wider data baseline for evidence-based initiatives. One of the research sessions at the 47th annual meeting of the Society for Epidemiologic Research on to tobacco and smoking showed that continued publication of health effects leads to reduction in smoking [ 31 ].

This study adds on to recent prevalence studies on substance use in high schools and adolescents in Limpopo province. Additionally, it contributes to baseline information which assists in the development of evidence-based initiatives. In line with the aims of international surveys [ 32 ] from which this study adopts, the findings support reporting of comparable data on drug use trends in Limpopo as well as having data from 1 of the 6 districts helps comparison within the province and supports targeted intervention and not a one size fits all approach. The main researcher was involved in anti-substance use clubs in some schools in Limpopo as part of health promotion and in light of many existing policies, it is worrying to note a gradual increase in prevalence rates of substance use amongst learners noting the gap between what is on paper and actual implementation (Lenkokile, 2016; Madikane, 2018; Mokwena et al., 2020). This study was an important process in Limpopo focused at providing current evidence towards developing effective context specific anti-substance use initiatives in high schools. The aim of this study was therefore to determine the prevalence of substance use among selected high school learners in schools in one district in Limpopo Province.

Study design

A cross-sectional survey (quantitative) was conducted among 768 high school learners from four high schools in the district.

Study population and sampling

The study population was all high school learners (N-13 244) enrolled in the period 2019–2020, Grade 8 to 12 [ 33 ]. Fifteen high schools within the Polokwane circuit were stratified into two strata according to socioeconomic and geographical divide: Urban and Peri-Urban. Simple random sampling was used to select two schools from each stratum. Once the four schools were identified, simple random sampling was used to select one class each from Grade 8 to 12 for participation in the cross-sectional survey. Consideration was taken to include the whole class so that learners are treated equally and excluding some students could affect anonymity perceptions and lead to disturbances [ 32 ]. However, due to the pressure of the announcement of the lockdown due to Covid 19 in March 2020 and schools closing, random sampling of classes was a bit limited to available classes in each grade.

Research sites

The study took place in four public high schools in the Polokwane circuit, Capricorn district, Polokwane local Municipality. The two peri urban schools selected are in the Seshego cluster on the north-west outskirts of the Polokwane city which is divided into 8 residential zones. Seshego is diverse with both extremes (poverty and wealth) located about 5kms from the CBD and most people must commute to the city for work. The urban schools are found more adjacent to the Polokwane city in Nirvana and Flora Park (formerly “coloured” and white” suburbs) but now quite diverse [ 34 ]. Polokwane is found in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Limpopo is a rural province with 5 district municipalities: Capricorn, Sekhukhune, Waterberg, Vhembe, and Mopani. Within the Capricorn district are four local municipalities: Polokwane, Blouberg, Molemole and Lepelle-Nkumpi [ 35 ].

Data Collection

The school management and the heads of department for Life Orientation were instrumental to grant permission to conduct the survey and to randomly select one class per each grade to participate in the schools. The questionnaire was distributed to the learners to fill in and the researcher was present to explain the purpose of the research and address any clarifications. The survey took place in March 2020, a few weeks, and days before the national lockdown due to COVID 19. The self-administered questionnaire used in this study, is a modified instrument adapted from the UNODC Global Assessment Programme on Drug Abuse (GAP) Toolkit questionnaire on Conducting School Surveys on Drug Abuse. This tool is deemed valid and reliable as it was used and adapted in previous studies [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. The original questionnaire was developed to build local level capacity among member states to collect data that can guide reduction activities in schools and therefore better fits the purpose for this study. The questionnaire was adapted to the local context using SA based terms and removing terms not relevant to the local context. A pilot study was conducted in a different circuit and adjustments made to the questionnaire and the process of data collection.

Ethical considerations

Permission to conduct the study was granted by the Limpopo Department of Education (Ref: 2/2/2) and the University of Western Cape (HS19/9/12). Information sheets, consent, and assent forms to participate in the study and seek permission from a guardian or parent were given to the learners prior to the data collection date. The researcher went with the invitations, information sheets and consent forms to the education circuit and these were sent to each school via the circuit office. The researcher also went with copies of the information sheets for the parents and learners to each school before the data collection. Therefore, the learners were informed of the study by providing them with an information sheet and explaining the purpose of the research and what is expected of them. An information sheet was also provided for the parents or guardians. Parents received information sheets and parental consent sought for learners to participate in the school survey. The signed forms from the parents/guardians were collected before administering the questionnaire to learners. Before administering the questionnaire, an explanation was provided again and learners above 18 received the consent forms and assent forms for learners under 18 to agree to participate in the study once they fully understood the purpose of the research.

Data analysis

Microsoft Excel was used to capture the data and exported to IBM SPSS v 26 for analysis to obtain baseline information about substance use in high schools (Briggs, 2016). Descriptive analysis was used to describe the independent and dependent variables using percentages, means, and standard deviation and inferential analysis such as correlation between sociodemographic characteristics and substance use, was used as well [ 39 ]. Percentages of gender, age, school, grades, level of parent’s education and person living with the learner were described. The frequency of substance use (alcohol, cigarette smoking and drugs) was presented to show lifetime, during the last 12 months and past 30 days (previous month) substance use. The Chi-Square test was used to investigate associations between demographic characteristics and substance use (cigarette smoking, alcohol use and drug use). The different p-values of less than 0.05 at a 5% significance level obtained, suggested that either grade, school, and gender have an influence and the differences on substance use depending on the substance. Percentages on awareness of substances, disapproval of substance use, friends who used substances, access to substances, perceived risk and associated behaviours under influence of substance use.

Demographic characteristics

Seven hundred and sixty-eight ( N = 768) learners from four high schools participated in the survey. 54.2% ( n = 416) were female and 45.8% ( n = 352) male learners, with a mean average age of 16 years. There were 286 participants from two schools in the peri-urban (school 2 and 3) and 482 participants from the urban environment (school 1 and 4). The percentage of grades was distributed proportionally with a slightly increased percentage among the Grade 10s. The break-down of the participants is represented in Table 1 . The percentage of participation in each grade in each school varied due to class size variation. For purpose of this article, only geographical location (urban and peri-urban), gender, age and school are reported in relation to substance use.

Perceived availability and awareness of substances

In the four participating schools, learners responded to availability of several substances with cigarettes indicated as the most easily accessible substance 46.5% ( n = 357) and mandrax the least accessible (see Table 2 ). The results indicate a wide variety of substances available to learners.

When learners were asked if they ever heard of the drugs listed on the questionnaire, learners had mostly heard of marijuana 72.1% ( n = 554), nyaope 69.8% ( n = 536), and least heard of ecstasy 22.3% ( n = 171) and other drugs 22.5% ( n = 173). Learners went on to mention the other drugs which included petrol, vape, tretamines and names that seemed mostly to be street names such as weed, Bluetooth, globe, flakka, hubbly, hashishka, cat, lollipop, ice pace and soil pill.

Trends in cigarette smoking and alcohol use

The overall lifetime prevalence of cigarette smoking among the learners was 20.8% (split according to the number of occasions (from 1 to 2 times to 40+) as seen in Table 3 ). 11.4% of the learners responded to have smoked during the last 12 months. In the last 30 days there was an overall prevalence of 7.1% further broken down by number of occasions. There was a high lifetime overall utilisation of alcohol with 49% of the learners having drunk alcohol (split according to the number of occasions (from 1 to 2 times to 40+) in Table 3 . 37.1% indicated alcohol consumption during the last 12 months with 13.7% who did not indicate. In the last 30 days the overall prevalence was at 20.9% with 16.3% who did not indicate. 9.6% of the learners indicated that they had five or more drinks in a row at least once and 4.4%, 10 or more times in the last 30 days.

An attempt was made to establish whether the learners’ socio-demographic characteristics were associated with cigarette smoking and alcohol use in a lifetime. The results as shown in Table 4 shows Chi-square test with a P- value of 0.000 at a 5% significance level suggesting that grade, school and gender have an influence on lifetime cigarette smoking. Schools in the urban area had an overall higher prevalence of cigarette smoking (14.6%) than schools in the Peri-Urban (7%) as cumulative effect. The results also show a significant difference in use for cigarette smoking by gender with more males (14.2%) than females (7.6%). The results in Table 4 also shows Chi-square test with a P- value of 0.001 for grade and 0.000 for gender suggest an association between lifetime alcohol use and these two socio-demographic characteristics with most alcohol use found to be in grade 10 (12.8%) and least in grade 8 (8%) as a cumulative effect. The differences in use among male and female learners varied with the number of occasions with overall high use in females (27.7%). There was no significant difference in alcohol use with schools.

Results showed that the age at first use of alcohol (beer, wine) and cigarette smoking was quite low at 13 years or less with a significant percentage even below 15 years of age. An age of 13 years or younger was taken as an indicator of early onset. At the age of 13 years or younger: 18.5% ( n = 142) of the learners had drunk beer, 18.8% ( n = 144) drank wine and 11.1% ( n = 85) had smoked cigarettes. There was a percentage decline in use with increasing age.

Trends in drug use

Learners who tried drugs.

When asked if they had ever tried the listed drugs on the questionnaire, 19.3% male learners and 13.9% of the female learners said “Yes” to marijuana. The results for the other drugs had lower percentages which varied but indicate more males had tried out substances than females.

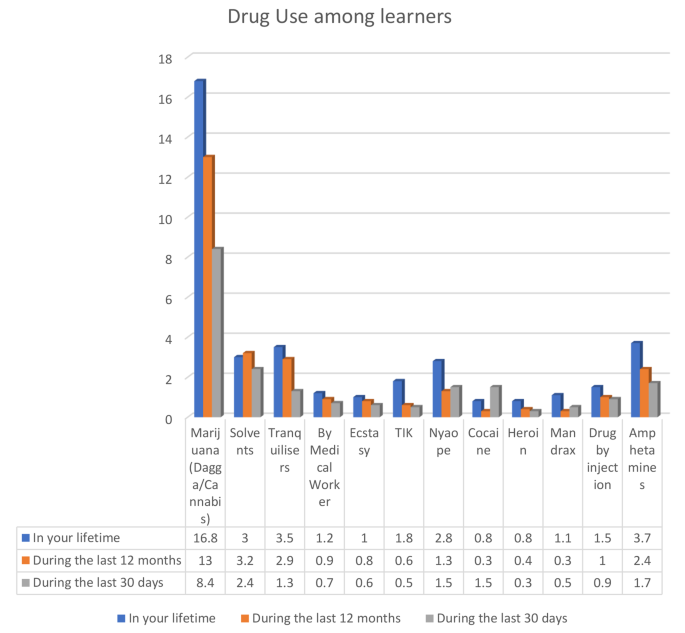

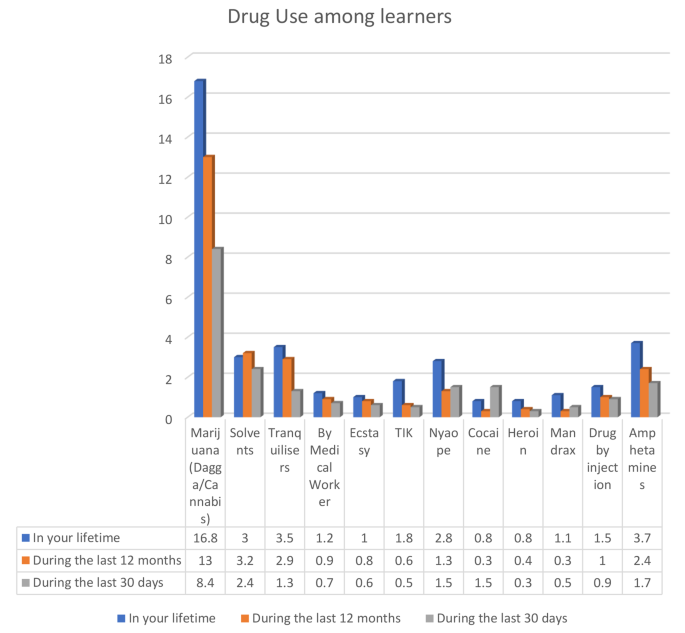

Lifetime use of drugs, during 12 months and last 30 days

Lifetime use of drugs varied with the type of drugs (see Fig. 1 ). A percentage overall of 16.8% of the learners had used marijuana in a lifetime, 13% in the last 12 months, and 8.4% in the last 30 days (see Fig. 1 ). Results also showed that the most common drug first tried was marijuana (dagga) (12.1%).

Drug use- Lifetime, During last 12 months and last 30 days

The Chi-square test was applied to investigate the association between socio-demographic characteristics and lifetime use of drugs. There was a significant association between school and the use of drugs prescribed by medical workers ( P = 0.03), ecstasy (0.01), nyaope/whoonga (0.025) and mandrax (0.03) with higher use in urban (20.7%) compared to peri-urban (16.9%) schools. There was an association between grade and the use of marijuana (dagga) (0.000) with overall high use from Grade 10 to 12 and gender on the use of marijuana (0.000) and nyaope (0.018) with more males (25.1%) than females (14.1%).

Risk of substance use

46% ( n = 352) of learners perceived great risk with smoking one or more packs of cigarettes per day, 40% ( n = 307) perceived great risk by having four or five drinks in a row nearly every day, 24% ( n = 183) of the learners perceived smoking cigarettes occasionally as a great risk but closely 22% ( n = 169) perceived no risk with smoking occasionally, 19% ( n = 147) no risk with having one or two drinks nearly every day and 16% ( n = 125) no risk with trying marijuana.

This study investigated the prevalence of substance use among high school learners and highlighted how certain socio-demographic characteristics such as gender, grade, and school influence substance use patterns.

Notably, our findings reveal gender disparities in substance use. Whilst alcohol use varied with the number of occasions among female and male learners, there was an overall high alcohol use in females (27.7%) compared to their male counterparts (24.5%). It is essential to recognize that our study, primarily focused on prevalence, and did not delve into the determinants of substance use specifically within gender groups. Nonetheless, contextual factors such as poverty and gender-based violence prevalent in South African communities may contribute to the elevated substance use rates observed among female learners. Additionally, delays in accessing social assistance could potentially exacerbate risky behaviors among this demographic. Additional research is needed into factors influencing a gradual increase in uptake among female learners which was beyond the scope of this study.

The study also shows further gender disparity with male learners demonstrating higher levels of experimentation and use of drugs, particularly marijuana and nyaope (whoonga). This trend aligns with existing research, which consistently indicates a higher prevalence of substance abuse among male learners. A review of past and present prevalence studies conducted in Limpopo high schools corroborates this observation, with multiple studies consistently reporting higher rates of drug abuse among male learners [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Assumptions from observation can be made that this could be linked to societal settings and friends in which boys “hang out” with more than girls and may have ease of access to drugs. Males tend to be found more on the corners of streets, shops and stay out late. The phenomenon of having more male users than females is found in many prevalence studies [ 20 , 29 , 48 , 49 , 50 ] suggesting the need for male-oriented initiatives. To show the magnitude of the problem “Harmful use of alcohol is accountable for 7.1% and 2.2% of the global burden of disease for males and females respectively” [ 51 ]. However, several studies are beginning to show that there is little difference in use between genders [ 55 ]. This suggests the need for gender-specific initiatives to ensure effective programs among adolescents.

The results of the present study indicate that substance use is rife in both peri-urban and urban environments among high school learners in the district. In a lifetime, cigarette smoking (20.8%), alcohol (49%), and marijuana (16.8%) were identified as the commonly used substances among the learners, mirroring trends observed in past studies conducted in Limpopo and Sub-Saharan Africa. A baseline study among youth conducted in Limpopo in 2013 showed percentage use of inhalants at 39%, marijuana (49%) and alcohol (54,8%) as the most used substances [ 30 ]. Similarly, a systematic review of 27 studies in Sub-Saharan Africa among 143 201 adolescents shows that alcohol (32.8%), tobacco products (23.5%), khat (22%) and cannabis (15.9%) were the most commonly used substances [ 53 ].

Despite these similarities, the present study indicates a decrease in the percentage use of these substances compared to past studies. This discrepancy could potentially be attributed to the present study’s focus on selected high schools within a district, as opposed to previous studies that may have had broader sampling across the entire province or region. Nonetheless, overall this data is comparable to a certain extent to results of national surveys that have been conducted using a similar instrument which show trends in use in a lifetime, annually and in the past month and correlations across demographic characteristics and substance use. Examples include the annual drug national survey of 2020 (Monitoring the Future) in the United States [ 38 ] and an older survey in Kenya on patterns of drug use in public secondary schools [ 36 ]. Therefore, the findings add to a wider data baseline for evidence-based initiatives and more specific to Limpopo towards evidence-based context-specific anti-substance use initiatives in high schools.

A worrying phenomenon observed in this study and other previous studies is the decreasing age of onset of substance use at the age of 13 years or less. Despite the legal restrictions in South Africa setting the minimum age purchasing alcohol and cigarettes at 18, adolescents are gaining access to these substances, as indicated by the study findings. The findings are consistent with the study conducted in Limpopo in 2013, which shows the age of first use of cannabis/marijuana as early as 10 years or less [ 29 ]. There have been policy discussions to amend the age to 21 but this may seem not to be effective considering that alcohol is easy to access by a 13-year-old or younger suggesting a “ thriving illegal market” [ 40 ]. A similar finding by the Southern Africa Alcohol Policy Alliance (SAAPA) showed that 12% of those under 13 years were said to have drunk alcohol in the past month and 25% of young people binge drinking [ 40 ]. The rise in underage use may also be linked to the ongoing alcohol advertising which is prominent in the neighbourhoods and entices adolescents. With mixed views on the introduction of the new Limpopo tobacco bill, it’s crucial to monitor any changes in adolescent access to substances. Calls for the bill to enforce strict measures on the sale of tobacco products to minors highlight the urgency of addressing this issue [ 52 ].

According to the WHO Global status report on alcohol and health [ 41 ], Alcohol is the leading risk factor for premature mortality and disability among those aged 15 to 49 years, accounting for 10% of all deaths in this age group. This highlights a huge public health challenge and the need for preventive strategies that target lower grades before the onset of substance use. Whilst learners are aware of the different types of substances there is still a significant number of learners who do not perceive the risk of smoking and drinking occasionally and trying marijuana. To improve the perceived risk associated with substance use among learners, as part of integration in education, consistent awareness programmes in all the subjects of the curriculum could assist in improving the level of perceived risk and not limited to the Life Orientation subject in the school curriculum only as recommended that health education should be established in all school topics [ 42 ]. . This approach aligns with recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [ 56 ], which emphasize the significance of prevention programs at different life stages and involving the community.

The increased lifetime utilisation of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana is linked to the ease of access of these substances as first experimental substances, providing a gateway for the introduction of other substances [ 30 ]. In line with the ecological model on determinants of health, some of the multiple factors for increased use and availability of marijuana among the learners could be that South Africa is ranked among the countries in the region where cannabis cultivation and production occur to a large extent and marijuana use is legalised for adults to cultivate and smoke in their homes. A contributing factor to use by learners is substance use by parents or adults they live with. In 2017, 3.8% of the global population aged 15 to 64 years used cannabis at least once and cannabis use increased significantly between 2010 and 2017 in Africa [ 46 ]. Cannabis (marijuana/dagga) is highly used globally with approximately 3.8% between 15 and 64 years, about 188 million people having used it once or more times in 2017 (UNODC, 2019). Cannabis is ranked among the most used substances among adolescents attributed to its ease of access and a low and drop in the percentage of the perceived risk of using it, as evidenced in Western countries (UNODC, 2018; UNODC, 2014; UNODC, 2021).

In terms of geographical determinants of substance use and abuse, there were higher percentages of cigarette smoking and drug use in the urban schools compared to peri-urban schools. There is a diverse group of learners attending schools in urban areas coming from different areas including from the peri-urban and rural areas. The majority of the learners commute to attend schools and are exposed to access and use of substances when traveling which contributes as a factor to the ongoing public health concern of substance use among adolescents. This phenomenon of learners commuting long distances is also highlighted by a study in New York where older students, girls, and higher attaining students are likely to commute to distant schools despite schools close to them [ 54 ]. As a result, the road to school exposes learners to many risky situations including access to substances. A collaboration between the Department of Education and the Department of Transport should exist to ensure safe transport systems for learners whilst, at the same time, more work needs to go into improving local schools working together with the local municipality.

There is a need for policy coherence in all sectors to address substance use especially in the health, education, justice, transport, trade and social development sectors. Policies in the trade sectors which ensure strict adherence to the sale of substances, harsher sentences in the justice sector for the illegal market, improvement in quality of local schools and improved learner transport, if adequately implemented can curb the access and exposure of substances among minors. Key policies like the National Drug Master Plan, which aims for a drug-free society through collaboration with other national departments such as health, justice, and education, need strengthening and universal implementation, including in all schools [ 47 ]. While numerous health-oriented public policies exist, there’s a noticeable gap in their implementation, highlighting the necessity for increased resources allocated toward their effective execution [ 43 ].

The revised ISHP has a component on health education on prevention of substance use. If implemented in all schools, it has a potential to reach learners and raise awareness at an early age and across all phases (foundation, intermediate and senior) on the dangers of use and may contribute more effectively to the reduction of substance use and early onset [ 44 ]. The School Safety Programme which derives itself from many of the policies including the South African Constitution, School Health Promotion, and Children’s Justice Act should also be strengthened to assist in the prevention and control of drugs in schools. The programme has a component of building capacity among school stakeholders [ 45 ]. Training should be escalated to all including educators to assist with the timely identification and intervention of learners who use drugs. Parents or guardians need to be included in the training and implementation process for prevention to support behavior change among the learners.

Limitations

There are two major limitations in this study that could be addressed in future research. Firstly, the analysis was restricted to specific socio-demographic variables, overlooking the potential influence of parents’ educational attainment and the composition of the learners’ living environment. Due to constraints in resources and time, this study did not delve into the association between substance use and these factors. However, exploring the impact of parents’ level of education and the presence of individuals residing with the learners could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying determinants of substance use. Future research endeavors should prioritize investigating these associations to enrich the existing knowledge base.

Secondly, the selection of classes was not randomized but based on availability, primarily due to logistical challenges exacerbated by the unforeseen onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown measures. Schools were compelled to adapt their operations swiftly, hindering the feasibility of a randomized sampling approach. Despite this limitation, the selected classes adequately represented the target population and facilitated the attainment of the study’s objectives. It is important to note that the deviation from randomization was a pragmatic adjustment necessitated by external circumstances and did not compromise the integrity or validity of the research findings.

Addressing these limitations in future studies will enhance the comprehensiveness of investigations into the complex dynamics of substance use among learners.

The findings of the study indicate that substance use is rife in high schools and utilization varies with sociodemographic characteristics. A more robust approach should be implemented which supports consistent health education integrated within all subjects of the curriculum from an early age. This should explore interactive means to reach the different social and educational platforms for learners to be informed, perceive the risk of substances from an early age and receive support. Findings also suggest the need for tailored health promotion programmes depending on the demographics of the learners (gender, grade and location of school) while also addressing the social determinants of substance use. One size does not fit all. The findings of this study contribute to the body of updated evidence on the prevalence of substance use in Limpopo Province among high school learners.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Central Drug Authority

Department of Basic Education

Department of Education

Department of Health

Department of Social Development

Department of Corporate Governance and Traditional Affairs

Human Immuno-deficiency Virus

Head of Department

Health Promoting Schools

Integrated School Health Policy

National School Safety Framework

Primary Health Care

South African Medical Research Council

South African National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence SACENDU: South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use

Statistics South Africa

School Governing Body

School Management Team

Crystal Methamphetamine

United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime

United Nations Population Fund

United Nations Children’s Fund

World Health Organisation

Youth Risk Behaviour Survey

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2014 (United Nations publication, Sales No. E.14.XI.7). United Nations publication. 2014.

Christian Addiction Support. Latest Drug Statistics-South Africa. 2016.

Kelley CP, [PDF], A review of Literature on Drug and Substance Abuse amongst Youth. and Young Women in South Africa - Free Download PDF [Internet]. 2016. https://silo.tips/download/a-review-of-literature-on-drug-and-substance-abuse-amongst-youth-and-young-women .

Ritchwood TD, Ford H, DeCoster J, Sutton M, Lochman JE. Risky sexual behavior and substance use among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev [Internet]. 2015;52:74–88. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4375751/ .

Jonas K, Crutzen R, van den Borne B, Sewpaul R, Reddy P. Teenage pregnancy rates and associations with other health risk behaviours: a three-wave cross-sectional study among South African school-going adolescents. Reprod Health [Internet]. 2016;13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4855358/ .

Heradstveit O, Skogen JC, Hetland J, Hysing M. Alcohol and illicit drug use are important factors for school-related problems among adolescents. Front Psychol. 2017;8(JUN).

Aboh I, Aboagye G, Isaac A, Ama Baidoo-Mensah M, Osei A, Enyonamowusu G. Effects of Substance Use on Students’ academic performance in selected Health Training Institutions effects of Substance Use on Students’ academic performance in selected Health Training Institutions. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2019;8:41–6.

Google Scholar

Abdullahi AM, Taha S. Substance abuse: a literature review of the implications and solutions. Int J Sci Eng Res. 2019;10(10).

Dada S, Town NH C, Burnhams C, Town J E., South African Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use SOUTH AFRICAN COMMUNITY EPIDEMIOLOGY NETWORK ON DRUG USE (SACENDU). Monitoring Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Abuse Treatment Admissions in South Africa [Internet]. 2017. Available from: http://196.21.144.194/adarg/sacendu/SACENDUPhase40.pdf.

World Health Organization. WHO | About youth and tobacco. Who.int [Internet]. 2004; https://www.who.int/tobacco/research/youth/youth/en/ .

Dada S, Harker N, Jodilee B, Lucas W, Parry C, Bhana A, MONITORING ALCOHOL, TOBACCO AND OTHER DRUG ABUSE TREATMENT ADMISSIONS IN SOUTH AFRICA [Internet]. 2020. p. 41. https://www.samrc.ac.za/sites/default/files/attachments/2022-07/SACENDUFullReportPhase47.pdf .

Alcock W. Gangsterism and drugs: The twin evils of our time [Internet]. 2018. https://www.news24.com/news24/mynews24/gangsterism-and-drugs-the-twin-evils-of-our-time-20181011 .

World Health Organization. Health promoting schools [Internet]. World Health Organization: WHO. 2019. https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-promoting-schools#tab=tab_1 .

World Health Organization. Intersectoral Case Study, THE HEALTHY SCHOOLS PROGRAMME IN SOUTH AFRICA CONTENTS [Internet]., 2013. https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2018-02/2014-03-06-the-healthy-schools-programme-in-south-africa.pdf .

Howell S, Couzyn K, The South African National Drug Master. Plan 2013–2017: A critical review. South African Journal of Criminal Justice [Internet]. 2015;28:1–23. https://www.jutajournals.co.za/the-south-african-national-drug-master-plan-2013-2017-a-critical-review/ .

World Health Organization Africa. President Jacob Zuma launches the Integrated School Health Programme [Internet]. 2023. https://www.afro.who.int/news/president-jacob-zuma-launches-integrated-school-health-programme .

Department of Basic Education, Department of Health. Integrated School Health Policy. South Africa. 2012.

Shuro L. The Development of An Anti-Substance Abuse Initiative for High Schools in The Capricorn District, Polokwane [Internet]. http://etd.uwc.ac.za/ .

Department of Education. Annual Report [Internet]. 2015. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201610/basiceducationannualreport201516.pdf .

Myburgh RC. Limpopo learners’ outcry for action [Internet]. 2019. https://www.citizen.co.za/review-online/news-headlines/2019/07/04/lim-learners-outcry-for-action/ .

Onya HE, Flisher AJ. Prevalence of substance use among rural high school students in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr J Drug Alcohol Stud. 2009;7.

Magabane PMK. An investigation of alcohol abuse among teenage learners: a case study of Lebitso Senior Secondary School, Limpopo Province [Internet]. 2009. http://ulspace.ul.ac.za/handle/10386/912 .

OWO OWOI. ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUGS: Prevalence, Demographic Characteristics and Perceived Effects On The Academic Performance Of High School Students Within The Mogalakwena Municipality Of Limpopo Province [Internet]. 2011. https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/ac1ac5bb-b388-4c60-8e62-a2f5afdcac33/content .

Tshitangano TG, Tosin OH. Substance use amongst secondary school students in a rural setting in South Africa: Prevalence and possible contributing factors. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med [Internet]. 2016;8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4845911/ .

Maserumule OM, Skaal L, Sithole SL. Alcohol use among high school learners in rural areas of Limpopo province. South Afr J Psychiatry. 2019;25.

Onya H, Tessera A, Myers B, Flisher A. Adolescent alcohol use in rural South African high schools. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg). 2012;15.

Lebese RT, Ramakuela NJ, Maputle MS. Perceptions of teenagers about substance abuse at Muyexe Village, Mopani district of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Afr J Phys Health Educ Recreat Dance. 2014;20:329–47.

Mohasoa I, Mokoena S. Factors contributing to Substance (drug) abuse among male adolescents in South African public secondary schools. Online. Int J Social Sci Humanity Stud. 2017;9:1309–8063.

Burton P, Leoschut L. School Violence in South Africa Results of the 2012 National School Violence Study [Internet]. Centre For Justice And Crime Prevention; 2013. pp. 1–129. Available from: School.

Department of Social Development, University of Limpopo. Substance use, misuse and abuse amongst the youth in Limpopo Province [Internet]. 2013. Available from: Substance.

Buck Louis GM, Bloom MS, Gatto NM, Hogue CR, Westreich DJ, Zhang C. Epidemiology’s Continuing Contribution to Public Health: The Power of Then and Now. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2015;181:e1–e8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4565605/ .

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Handbook for implementing school surveys on drug abuse GAP Toolkit Module 2: Handbook on School Surveys [Internet]. 2003. https://www.unodc.org/pdf/gap_toolkit_module2_school-surveys.pdf .

Department of Education. SA-SAMS Term 2. 2018.

African Centre for Migration & Society, University of Witwatersrand, Feinstein International Center Tufts University. Developing a Profiling Methodology for Displaced People in Urban Areas [Internet]. 2012. pp. 1–55. https://fic.tufts.edu/wp-content/uploads/Polokwane-report-final-jv1-1.pdf .

Statistics South Africa. Limpopo Community Survey 2016 results [Internet]. Statistics South Africa. 2016. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=7988#:~:text=Limpopo .

Ndetei DM, Khasakhala LI, Mutiso V, Ongecha-Owuor FA, Kokonya DA. Patterns of drug abuse in public secondary schools in Kenya. Subst Abus. 2009;30:69–78.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Kraus L, Guttormsson U, Leifman H, Arpa S, Molinaro S, Monshouwer K et al. ESPAD report 2015 results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs. 2016.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Monitoring the Future [Internet]. 2021. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/monitoring-future .

Creswell JW. Research Design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Sage Publications Ltd; 2014.

Law for All. Legal Drinking Age in South Africa: Should it be 21? | LAW FOR ALL Online [Internet]. 2018. https://www.lawforall.co.za/legal-news/legal-drinking-age-south-africa/ .

World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 Oct 24]. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/274603/9789241565639-eng.pdf?sequence=1 .

World Health Organization, Nations Educational U, Organization S. C. Making every school a health-promoting school – Implementation Guidance [Internet]. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240025073 .

Masiko N, Xinwa S. Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation Substance Abuse in South Africa, Its Linkages with Gender Based Violence and Urban Violence CSVR Fact Sheet on Substance Abuse in South Africa L October 2017 [Internet]. 2017. https://www.saferspaces.org.za/uploads/files/Substance_Abuse_in_SA_-_Linkages_with_GBV__Urban_Violence.pdf .

Lipari R, Jean-Francois B. Trends in Perception of Risk and Availability of Substance Use Among Full-Time College Students. The CBHSQ Report. 2013.

Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention. National School Safety Framework (NSSF) [Internet]. 2015. https://www.saferspaces.org.za/be-inspired/entry/national-school-safety-framework-nssf .

Stephens RS. Cannabis and hallucinogens. World drug report. 2019;1–73.

Department of Social Development. & Central Drug Authority. National Drug Master Plan 2013–2017 [Internet]. 2013. https://www.gov.za/documents/national-drug-master-plan-2013-2017 .

Al-Musa H, Doos S, Al-Montashri S. Substance abuse among male secondary school students in Abha City, Saudi Arabia: prevalence and associated factors. Biomedical Research [Internet]. 2016;27. https://www.alliedacademies.org/articles/substance-abuse-among-male-secondary-school-students-in-abha-city-saudi-arabia-prevalence-and-associated-factors.pdf .

Idowu A, Aremu AO, Olumide A, Ogunlaja AO. Substance abuse among students in selected secondary schools of an urban community of Oyo-state, South West Nigeria: implication for policy action. Afr Health Sci [Internet]. 2018;18:776–85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6307013/ .

Anyanwu OU, Ibekwe RC, Ojinnaka NC. Pattern of substance abuse among adolescent secondary school students in Abakaliki. Cogent Med. 2016;3(1):1272160.

Article Google Scholar

World Health Organization. Harmful use of alcohol [Internet]. World Health Organization: WHO. 2018. https://www.who.int/health-topics/alcohol#tab=tab_1 .

Media Statement: Tzaneen Residents Express Mixed Views on Tobacco Bill and Highlight a Concern on Inadequate Capacity to Enforce Laws. - Parliament of South Africa [Internet]. Parliament.gov.za. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 5]. https://www.parliament.gov.za/press-releases/media-statement-tzaneen-residents-share-mixed-views-tobacco-bill-and-highlight-concern-inadequate-capacity-enforce-laws .

Olawole-Isaac A, et al. Substance use among adolescents in sub-saharan africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. South Afr J Child Health. 2018;12(2b):79. https://doi.org/10.7196/sajch.2018.v12i2b.1524 .

Corcoran SP. (2018) School choice and commuting, Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/school-choice-and-commuting (Accessed: 09 February 2024).

McHugh RK et al. (2018) Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders, Clinical psychology review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5945349/ (Accessed: 09 February 2024).

Bierman KL, Hendricks Brown C, Clayton RR, Dishion TJ, Foster EM, Glantz MD et al. Preventing Drug Use Among Children and Adolescents (Redbook) [Internet]. 2003. https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/preventingdruguse_2.pdf .

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work is based on the research supported by The Belgian Directorate- General for Development Cooperation, through its Framework Agreement with the Institute for Tropical Medicine (Grant Ref: FA4 DGD-ITM 2017–2020). The authors would also like to acknowledge funding from the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant no. 82769)’. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the funders.

The Belgian Directorate- General for Development Cooperation, through its Framework Agreement with the Institute for Tropical Medicine (Grant Ref: FA4 DGD-ITM 2017–2020), The South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant no. 82769) funded the involvement of LS in this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape, Robert Sobukwe Rd, Bellville, Cape Town, 7535, South Africa

Linda Shuro

Faculty of Community & Health Sciences, University of the Western Cape, 14 Blanckenberg Road Bellville, Cape Town, 7535, South Africa

Firdouza Waggie

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.S. took lead in writing this manuscript and F.W. provided critical feedback and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Linda Shuro .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The research proposal for the study received ethical clearance from the University of Western Cape (UWC) Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee from 18 November 2019 to 18 November 2020, ethics reference number: HS19/9/12. An application to the ethics committee for additional ethical amendments was made to include conducting interviews virtually in July 2020 due to the Covid-19 lockdown regulations. Ethics renewal was also sought and granted with an extension from 21 April 2021 to 21 April 2023. Permission was granted to conduct the study by the Limpopo Department of Education within the selected schools. The study was conducted in accordance with the general ethical guidelines and regulations of the ethics committee and Department of Education. Informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality and right to withdraw was assured to all the participants. Informed consent ensured that the participants were fully informed of what the study entailed, what is expected from them, for them to decide whether they will participate in the research or not. The researcher visited each of the schools and explained the study to the principals and HOD. The researcher also visited the NGO that participated to present the study and ask for participation. The researcher went with the invitations, information sheets and consent forms to the circuit and these were sent to each school via the circuit office. The researcher also went with copies of the information sheets for the parents and learners to each school before the data collection. Therefore, the learners were informed of the study by providing them with an information sheet explaining the purpose of the research and what is expected of them. They also received the consent forms and assent forms to agree to participate in the study once they fully understood the purpose of the research. Parents/legal guardians received information sheets and parental informed consent sought for learners to participate in the school survey. Anonymity was assured by the fact that participants’ information/responses were not ascribed to them specifically. It was assured that no names of individuals or the schools were written on the transcripts or in the report or publications. A preliminary report was made available to all relevant participants to verify the accuracy of the information before submission of the thesis for marking. An explanation was provided that the research is for academic purposes only and that there are no foreseeable risks from this research. Counselling and referral services to a social worker were arranged if participants experienced emotional discomfort during the data collection. However, during data collection, no participants required such services. Participants were informed that they are free to not participate further in the study at any time during the data collection process. It was explained that the research is not designed to help the participants personally, but the results may help the investigator learn more about factors linked to substance abuse in high schools and develop informed strategies. It was explained that the study provided valuable information and resources (Anti-Substance Abuse Initiative and situational analysis of the problem) which can benefit the high school community to develop skills to tackle substance abuse. This in turn could improve educational attainment and reduce risky behaviours.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shuro, L., Waggie, F. Trends in socio-demographic characteristics and substance use among high school learners in a selected district in Limpopo Province, South Africa. BMC Public Health 24 , 1407 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18927-7

Download citation

Received : 24 October 2023

Accepted : 22 May 2024

Published : 27 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18927-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Substance use

- High School Learners

- Adolescents

- School health

- Limpopo, South Africa

- Cross-sectional survey

- Socio-ecological model

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Open access

- Published: 07 July 2023

Prevalence and correlates of substance use among school-going adolescents (11-18years) in eight Sub-Saharan Africa countries

- Nuworza Kugbey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0413-0350 1

Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy volume 18 , Article number: 44 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

7187 Accesses

7 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Substance use constitutes a major public health issue especially among adolescents as it has associated adverse behavioural, health, social and economic outcomes. However, there is a paucity of comprehensive evidence on the prevalence and associated factors of substance use (alcohol, marijuana and amphetamine) among school-going adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). This study examined the magnitude of substance use and its associated factors among school-going adolescents in eight eligible sub-Saharan Africa countries.

Data for the study were obtained from the Global School-based Health Survey (2012–2017) of 8 countries in SSA (N = 16,318).

Findings showed overall prevalence rates of 11.3% (95%CI = 10.8 − 11.8%), 2% (95%CI = 1.8 − 2.2%) and 2.6% (95%CI = 2.3 − 2.9%) for current alcohol use, current marijuana use and lifetime amphetamine use, respectively between 2012 and 2017. Late adolescence (15–18 years), being male, anxiety, bullying, fighting, truancy, having close friends, current cigarette smoking and tobacco use are significant risk factors for alcohol use. Anxiety, truancy, current cigarette smoking, tobacco use and suicidal attempt are significant risk factors for marijuana use. Anxiety, bullying, truancy, current cigarette smoking, tobacco use and suicidal attempt are significant risk factors for amphetamine use. Parental knowledge of activity, supervision and respect of privacy are significant protective factors of substance use.

There is the need for comprehensive public health policies beyond school-based psycho-behavioural interventions targeting the significant risk factors of substance use among school-going adolescents in SSA.

Introduction

Substance use among adolescents is a major public health issue as its consequences transcend physical health, psychological problems and social problems to include truancy and poor academic performance due to memory problems [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. According to the WHO, the adolescence period is a transition between childhood and adulthood, usually from 10 to 19years. Some early researchers have categorized adolescents between 10 and 14years as early adolescence and those between 15 and 19years as late adolescence [ 5 ]. The Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) study reported alcohol use to be the 4th leading cause of disability among youth between 10 and 24years with significant sex variations [ 6 , 7 ]. Substance use among adolescents is associated with poor physical health outcomes, serious injuries, depression, anxiety, truancy, poor academic performance and other risky behaviours [ 1 , 4 , 5 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ].

Estimates from individual studies on alcohol use among in-school adolescents in SSA countries range from 10 to 44% [ 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Apart from alcohol use, marijuana and amphetamine use are on the rise among adolescents with their associated negative consequences. Some multi-country studies have reported varying rates of substance use among in-school adolescents. For example, Peltzer and Pengpid [ 15 ] found 0.9% lifetime cannabis use and 1% lifetime amphetamine use among in-school adolescents from five Asian countries. However, individual country estimates of marijuana use among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa range from 5 to 28% [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. These high rates of marijuana use have been reported to have associated comorbid substance use and mental health problems.

Estimates of amphetamine use from individual countries in SSA range from 7 to 10% [ 1 , 18 ]. However, the WHO African Region in 2021 asserts that “[a]mphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) such as ‘ecstasy’ and methamphetamine now rank as Africa’s second most widely abused drug type”. An earlier multi-country study conducted among in-school adolescents between 2009 and 2013 reported a 4.1% current marijuana and a 5.1% lifetime amphetamine use in nine sub-Saharan Africa countries [ 19 ].

Several risks and protective factors have been associated with substance use among adolescents especially in Africa. For example, socio-demographic characteristics such as grade in school, sex-being male, and age-older adolescents [ 20 , 21 ], mental health-related factors such as depression, anxiety, suicidal behaviours and tobacco use [ 10 ], socio-environmental factors such as having experienced hunger, been bullied, having been in a physical fight and having been attacked [ 18 , 20 , 22 ] and parenting factors such as parental substance use, knowledge of activity, supervision and respect of privacy [ 18 , 20 , 23 , 24 ] are implicated.

Apart from the study on cannabis and amphetamine use by school-going adolescents in nine SSA countries by Peltzer and Pengpid [ 19 ] which examined the Global School-based Health Survey (2009–2013), no recent multi-country studies have been conducted to (1) examine the burden of substance use (alcohol, marijuana and amphetamine) among adolescents using the most recent data from in-school adolescents in SSA (2012–2017) as well as (2) explore the risk and protective factors of substance use to inform targeted school-based and other public health interventions. The study by Peltzer and Pengpid [ 19 ] only examined cannabis and amphetamine without alcohol which has become a major public health issue among youth worldwide and in SSA in particular. This current study fills this gap by examining the prevalence and associated factors of substance use (alcohol, marijuana and amphetamine) among in-school adolescents in eight SSA countries to inform policy, practice and education.

Data and sample

Secondary data were used for this study. Data were obtained from the Global School-based Student Health Survey of 8 countries in SSA (N = 16,318) between 2012 and 2017 (see Table 1 ). The Global School-based Health Survey is sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to collect data on health behaviours and their associated factors in school-going adolescents across several low-income and middle-income countries. Health behaviours and related factors include alcohol use, dietary behaviours, drug use, hygiene, mental health, physical activity, protective factors, sexual behaviours, tobacco use, violence and unintentional injury. Data collection involved closed-ended questionnaires administered to in-school adolescents in the various countries. Multi-stage sampling technique was used and the eligible sample sizes from the eight countries are summarized in Table 1 . For this study, 16,318 adolescents across the eight countries had the complete set of the study variables.

Study variables

Outcome variables.

There were three main outcome variables in this study (current alcohol use, current marijuana use and lifetime amphetamine use). Single items were used to measure each of the outcome variables. Current alcohol use was measured with the question “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink containing alcohol?” Responses ranged from 1 = 0 days to 7 = All 30 days. The responses were further recoded as 1 = 0 (No) and 2 to 7 = 1 (Yes). Current marijuana use was measured with the question “During the past 30 days, how many times have you used marijuana (also called dagga, weed, boom, cannabis, stop, grass, pipt, stop, and joint or other country-specific names)?” Responses ranged from 1 = 0 days to 7 = All 30 days. The responses were further recoded as 1 = 0 (No) and 2 to 7 = 1 (Yes). Lifetime amphetamine use was measured with the question “During your life, how many times have you used amphetamines or methamphetamines (also called tik, speed, bennies, uppers, black beauties, mollies, or splash, or other country-specific names)?” Responses ranged from 1 = 0 times to 5 = 20 or more times. The responses were further recoded as 1 = 0 (No) and 2 to 5 = 1 (Yes).

Explanatory variables

A set of explanatory variables including socio-demographic characteristics (age and sex), mental health variables (anxiety, loneliness and suicidal behaviours), socio-environmental factors (hunger, bullying, physical attack, fighting, tobacco use, cigarette smoking, truancy, and having close friends) and parental factors (supervision, connectedness, knowledge of activity and privacy) were used in the current study based on their relevance in influencing adolescents’ health-related behaviours [ 5 , 9 , 25 , 26 ].

Statistical analyses

Stata Software version 17 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for the data analysis. Data from the eight countries were extracted from the WHO website, cleaned and recoded for the analysis. To pull all the data together, the append command was used to generate one dataset comprising the eight countries. Measurements of the prevalence of substance use (alcohol, marijuana and amphetamine) in the eight were done using counts and percentages with graphical illustration (Fig. 1 ). The bivariate associations between the explanatory variables and substance use were done using Pearson’s Chi-square test, and alpha level was set at 0.05. Multivariate analysis was done using logistic regression analysis with results presented in both unadjusted (OR) and adjusted (AOR) forms for each outcome variable. The odd ratios were presented with their 95% Confidence interval with statistical significance set at 0.05. Collinearity analysis was done and the results showed VIF values between 1.01 and 1.60 with a mean of 1.20. These results showed no evidence of substantial collinearity among the study variables. In all the analyses, the survey sampling weight was applied to ensure accurateness in the estimates from the surveys.

Prevalence of substance use among adolescents in Africa

Results from Fig. 1 showed that the overall prevalence rates of substance use among school-going adolescents in SSA were 11.3%, 2% and 2.6% for current alcohol use, marijuana use and amphetamine use, respectively. Current alcohol use was highest in Seychelles (46.5%) and lowest in Tanzania (2.7%). Current marijuana use was highest in Seychelles (6.6%) and lowest in Mozambique (0.9%). The highest rate of lifetime amphetamine use was reported among adolescents in Ghana (5.5%), and the lowest rate of amphetamine use was reported among adolescents in Mozambique (0.7%).

Prevalence of current alcohol use, current marijuana use, and amphetamine use

Associations between explanatory variables and adolescents’ substance use

Findings from Table 2 showed that all the explanatory variables in exception of respect of privacy (No privacy = 11.3% vs. Privacy = 11.1%, p = 0.165) were significantly associated with current alcohol use among the school-going adolescents. All the explanatory variables except having close friends (No = 2.8% vs. 1.9%, p = 0.493) were significantly associated with current marijuana use among school-going adolescents in SSA. It was further revealed that all the explanatory variables except social connectedness (No = 2.5% vs. Yes = 2.7%, p = 0.198) were significantly associated with current amphetamine use among school-going adolescents in SSA.

Risk and protective factors of substance use among school-going adolescents

Results from Table 3 show that late adolescence (aOR = 2.63, 95%CI = 2.19–3.16), being male (aOR = 1.34, 95%CI = 1.16–1.54), anxiety (aOR = 1.86, 95%CI = 1.50–2.30), bullying (aOR = 1.49, 95%CI = 1.29–1.73), engaging in a fight (aOR = 1.32, 95%CI = 1.13–1.55), truancy (aOR = 1.49, 95%CI = 1.29–1.74), having close friends (aOR = 1.56, 95%CI = 1.22–2.00), current cigarette smoking (aOR = 5.41, 95%CI = 3.97–7.37) and tobacco use (aOR = 2.64, 95%CI = 1.93–3.59) significantly increased the odds for current alcohol use among school-going adolescents. However, parental supervision (aOR = 0.70, 95%CI = 0.60–0.82) and parental knowledge of activity (aOR = 0.63, 95%CI = 0.53–0.74) significantly decreased the odds for current alcohol use among school-going adolescents.

Anxiety (aOR = 1.90, 95%CI = 1.05–3.41), truancy (aOR = 3.20, 95%CI = 2.12–4.83), current cigarette smoking (aOR = 5.16, 95%CI = 3.03–8.79), tobacco use (aOR = 9.34, 95%CI = 5.62–15.52) and suicidal attempt (aOR = 2.21, 95%CI = 1.30–3.74] significantly increased the odds for marijuana use among school-going adolescents in SSA. However, parental knowledge of activity (aOR = 0.59, 95%CI = 0.36–0.96) and respect for privacy (aOR = 0.62, 95%CI = 0.40–0.97) significantly decreased the odds for marijuana use among school-going adolescents in SSA.

Anxiety (aOR = 2.16, 95%CI = 1.39–3.34), bullying (aOR = 2.25, 95%CI = 1.54–3.29), truancy (aOR = 1.83, 95%CI = 1.31–2.57), current cigarette smoking (aOR = 2.43, 95%CI = 1.42–4.17), tobacco use (aOR = 7.68, 95%CI = 4.91–12.02) and suicidal attempt (aOR = 1.86, 95%CI = 1.14–3.01) significantly increased the odds for amphetamine use among school-going adolescents in SSA. However, only parental respect of privacy (aOR = 0.52, 95%CI = 0.36–0.75) decreased the odds for current amphetamine use among school-going adolescents in SSA.

Substance use predisposes adolescents to several physical, psychological [ 27 ], social and academic consequences. Understanding the burden of substance use in SSA is one of the major steps in addressing the menace with focus on key identified risk and protective factors. This study addressed this gap by examining the prevalence and the associated risk and protective factors of alcohol, marijuana and amphetamine use among school-going adolescents in SSA.

Prevalence of alcohol, marijuana and amphetamine use among school-going adolescents

The overall prevalence rates of substance use among school-going adolescents in SSA were 11.3%, 2% and 2.6% for current alcohol use, current marijuana use and life time amphetamine use, respectively. The prevalence rates vary by country with school-going adolescents in Seychelles (46.5%) reporting the highest rate of current alcohol use and school-going adolescents in Tanzania (2.7%) reporting the lowest rate of current alcohol use. For current marijuana use, school-going adolescents in Seychelles (6.6%) reported the highest rate and school-going adolescents in Mozambique (0.9%) reported the lowest rate. The highest rate of lifetime amphetamine use was reported among school-going adolescents in Ghana (5.5%) and the lowest rate of amphetamine use was reported among adolescents in Mozambique (0.7%). These variations in the prevalence of substance use among school-going adolescents can be attributed to variations in the risk and protective factors of substance use within SSA countries. For example, multi-country studies in SSA have reported variations in risk factors for substance use such as bullying victimization [ 9 ], serious injuries [ 5 , 26 ], truancy [ 25 ] and suicidal behaviours [ 19 , 24 ]. Specifically, Seychelles has large tourist visits from western countries with liberal attitudes and practices regarding substance use including alcohol and marijuana which could influence school-going adolescents through observational learning. In the case of Ghana, the lack of effective drug enforcements could be one of the key contributing factors to high amphetamine use among in-school adolescents as some researchers have reported increasing use of drugs including tramadol [ 28 ]. One of the key contributing factors to these high rates and variations in substance use among adolescents in Africa could be lack of effective implementation of laws regarding substance use among underage youth in many African countries. Additionally, the easy access and availability of these substances as well as social norms [ 29 ] in the various countries might have contributed to the high rates of substance use among adolescents in Africa.

Risk and protective factors of alcohol, marijuana and amphetamine use among school-going adolescents

Findings from the study showed late adolescence (15–18 years), being male, anxiety, bullying, fighting, truancy, having close friends, current cigarette smoking and tobacco use are significant risk factors for alcohol use. Several studies conducted in individual countries have found varied risk factors for alcohol consumption among in-school adolescents in Africa. Male adolescents are reported to engage in more risky behaviours than females [ 6 , 30 ], and late adolescents have been noted for increased risky behaviours including alcohol consumption as reported in the GBD study on adolescents which found alcohol use to rank as the 3rd leading contributor to disease burden among late adolescent males [ 6 ]. The experience of mental health challenges and negative socio-environmental circumstances predisposes adolescents to the use of alcohol and other substances as a coping strategy to deal with their problems [ 10 , 14 ].

Similar risk factors were found for marijuana and amphetamine use except for the socio-demographic characteristics. For example, anxiety, truancy, current cigarette smoking, tobacco use and suicidal attempt increased the risks for both marijuana use and amphetamine use. This is consistent with most of the country-level study findings [ 18 , 31 , 32 ] and multi-country-level findings among adolescents from the Caribbean, ASEAN and some African countries [ 15 , 19 , 33 ]. The experience of bullying was a significant risk factor for amphetamine use which is a cause for concern as bullying has been reported to be pervasive among adolescents in Africa [ 9 , 34 , 35 ]. The implication of these findings is that school-based intervention programmes aimed at addressing substance use among adolescents should take into consideration mental health and socio-environmental issues that predispose adolescents to engage in substance use behaviours.

Parental knowledge of activity, supervision and respect of privacy were found be significant protective factors of substance use. The role of parental involvement in adolescents’ risky behaviours has been widely reported by previous studies [ 10 , 24 , 30 ]. This is because when adolescents are monitored and given the necessary guidance in dealing with the myriad of challenges associated with the period of adolescence, they are less likely to engage in substance use behaviours. Thus, the role of parents in any intervention programmes aimed at addressing substance use should not be overlooked.

Limitations

Although the cross-sectional study nature presents a major limitation to the findings, this study provides updated knowledge on substance use burden among in-school adolescents in SSA to inform adolescents health research, practice and policy. The different data collection years could serve as a limitation to the findings as these variations in the periods could influence the outcomes. For example, countries may have experienced different socio-economic or political environments which could have impacted on substance use among the adolescents. Due to the self-report nature of the data collection procedure, there could be social desirability biases which can influence the variations in the findings. It is also important to note that the prevalence of amphetamine cannot be compared with that of alcohol and marijuana since the periods of measurement differ, that is, lifetime prevalence for amphetamine and current prevalence (30days) for alcohol and marijuana. Despite these limitations, regular updates using most recent data from the Global School-based Student Health Survey is warranted. It is also important examine the trends in substance use across the various countries to understand the magnitude and patterns of substance use problems among adolescents in SSA. Wider policy-level factors were not examined in this study as the available data did not cover substance use policy variables.

Substance use among in-school adolescents is a major public health issue, and the between country variations observed in this current study in the prevalence of alcohol, marijuana and amphetamine use suggests the need for country-specific programmes adapted to the needs and available resources within each country. Mental health and socio-environmental factors are significant risk factors of substance use in Africa, and urgent efforts are needed using a multi-sectoral approach to address this menace. High risks of alcohol use in adolescence could escalate into heavy alcohol use and alcohol dependence. Tobacco and alcohol use are ‘gateway’ substances that facilitate experimentation of marijuana and methamphetamine, and addressing these through public health policies could have an impact on other drug use among adolescents [ 36 , 37 ]. Amphetamine, a relatively less used substance, is now becoming a common place among in-school adolescents in SSA and therefore requires concerted efforts to holistically address it.

Availability of supporting data

Data for this study can be obtained from https://extranet.who.int/ncdsmicrodata/index.php/catalog/GSHS .

Degenhardt L, Coffey C, Moran P, Carlin JB, Patton GC. The predictors and consequences of adolescent amphetamine use: findings from the Victoria Adolescent Health Cohort Study. Addiction. 2007;102(7):1076–84.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Degenhardt L, Stockings E, Patton G, Hall WD, Lynskey M. The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(3):251–64.

Livingston M, Raninen J, Pennay A, Callinan S. The relationship between age at first drink and later risk behaviours during a period of youth drinking decline. Addiction. 2023;118(2):256–64.

Macleod J, Oakes R, Copello A, Crome I, Egger M, Hickman M, Oppenkowski T, Stokes-Lampard H, Smith GD. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. The Lancet. 2004;363(9421):1579–88.

Article Google Scholar

Aboagye RG, Mireku DO, Nsiah JJ, Ahinkorah BO, Frimpong JB, Hagan JE, Abodey E, Seidu A-A. Prevalence and psychosocial factors associated with serious injuries among in-school adolescents in eight sub-saharan african countries. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–8.

Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Mathers CD. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. The Lancet. 2011;377(9783):2093–102.

Ward JL, Azzopardi PS, Francis KL, Santelli JS, Skirbekk V, Sawyer SM, Kassebaum NJ, Mokdad AH, Hay SI, Abd-Allah F. Global, regional, and national mortality among young people aged 10–24 years, 1950–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2021;398(10311):1593–618.