College of Arts and Sciences

History and American Studies

- What courses will I take as an History major?

- What can I do with my History degree?

- History 485

- History Resources

- What will I learn from my American Studies major?

- What courses will I take as an American Studies major?

- What can I do with my American Studies degree?

- American Studies 485

- For Prospective Students

- Student Research Grants

- Honors and Award Recipients

- Phi Alpha Theta

Alumni Intros

- Internships

Thesis Statements

Every paper must argue an idea and every paper must clearly state that idea in a thesis statement.

A thesis statement is different from a topic statement. A topic statement merely states what the paper is about. A thesis statement states the argument of that paper.

Be sure that you can easily identify your thesis and that the key points of your argument relate directly back to your thesis.

Topic statements:

This paper will discuss Harry Truman’s decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima.

The purpose of this paper is to delve into the mindset behind Truman’s decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima.

This paper will explore how Harry Truman came to the decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima.

Thesis statements:

Harry Truman’s decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima was motivated by racism.

The US confrontation with the Soviets was the key factor in Truman’s decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima.

This paper will demonstrate that in his decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima, Truman was unduly influenced by hawks in his cabinet.

How have History & American Studies majors built careers after earning their degrees? Learn more by clicking the image above.

Recent Posts

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 26, 2024

- Fall 2024 Courses

- Fall 2023 Symposium – 12/8 – All Welcome!

- Spring ’24 Course Flyers

- Internship Opportunity – Chesapeake Gateways Ambassador

- Congratulations to our Graduates!

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 21, 2023

- View umwhistory’s profile on Facebook

- View umwhistory’s profile on Twitter

Module 4: Imperial Reforms and Colonial Protests (1763-1774)

Historical thesis statements, learning objectives.

- Recognize and create high-quality historical thesis statements

Some consider all writing a form of argument—or at least of persuasion. After all, even if you’re writing a letter or an informative essay, you’re implicitly trying to persuade your audience to care about what you’re saying. Your thesis statement represents the main idea—or point—about a topic or issue that you make in an argument. For example, let’s say that your topic is social media. A thesis statement about social media could look like one of the following sentences:

- Social media are hurting the communication skills of young Americans.

- Social media are useful tools for social movements.

A basic thesis sentence has two main parts: a claim and support for that claim.

- The Immigration Act of 1965 effectively restructured the United States’ immigration policies in such a way that no group, minority or majority, was singled out by being discriminated against or given preferential treatment in terms of its ability to immigrate to America.

Identifying the Thesis Statement

A thesis consists of a specific topic and an angle on the topic. All of the other ideas in the text support and develop the thesis. The thesis statement is often found in the introduction, sometimes after an initial “hook” or interesting story; sometimes, however, the thesis is not explicitly stated until the end of an essay, and sometimes it is not stated at all. In those instances, there is an implied thesis statement. You can generally extract the thesis statement by looking for a few key sentences and ideas.

Most readers expect to see the point of your argument (the thesis statement) within the first few paragraphs. This does not mean that it has to be placed there every time. Some writers place it at the very end, slowly building up to it throughout their work, to explain a point after the fact. For history essays, most professors will expect to see a clearly discernible thesis sentence in the introduction. Note that many history papers also include a topic sentence, which clearly state what the paper is about

Thesis statements vary based on the rhetorical strategy of the essay, but thesis statements typically share the following characteristics:

- Presents the main idea

- Most often is one sentence

- Tells the reader what to expect

- Is a summary of the essay topic

- Usually worded to have an argumentative edge

- Written in the third person

This video explains thesis statements and gives a few clear examples of how a good thesis should both make a claim and forecast specific ways that the essay will support that claim.

You can view the transcript for “Thesis Statement – Writing Tutorials, US History, Dr. Robert Scafe” here (opens in new window) .

Writing a Thesis Statement

A good basic structure for a thesis statement is “they say, I say.” What is the prevailing view, and how does your position differ from it? However, avoid limiting the scope of your writing with an either/or thesis under the assumption that your view must be strictly contrary to their view.

Following are some typical thesis statements:

- Although many readers believe Romeo and Juliet to be a tale about the ill fate of two star-crossed lovers, it can also be read as an allegory concerning a playwright and his audience.

- The “War on Drugs” has not only failed to reduce the frequency of drug-related crimes in America but actually enhanced the popular image of dope peddlers by romanticizing them as desperate rebels fighting for a cause.

- The bulk of modern copyright law was conceived in the age of commercial printing, long before the Internet made it so easy for the public to compose and distribute its own texts. Therefore, these laws should be reviewed and revised to better accommodate modern readers and writers.

- The usual moral justification for capital punishment is that it deters crime by frightening would-be criminals. However, the statistics tell a different story.

- If students really want to improve their writing, they must read often, practice writing, and receive quality feedback from their peers.

- Plato’s dialectical method has much to offer those engaged in online writing, which is far more conversational in nature than print.

Thesis Problems to Avoid

Although you have creative control over your thesis sentence, you still should try to avoid the following problems, not for stylistic reasons, but because they indicate a problem in the thinking that underlies the thesis sentence.

- Hospice workers need support. This is a thesis sentence; it has a topic (hospice workers) and an argument (need support). But the argument is very broad. When the argument in a thesis sentence is too broad, the writer may not have carefully thought through the specific support for the rest of the writing. A thesis argument that’s too broad makes it easy to fall into the trap of offering information that deviates from that argument.

- Hospice workers have a 55% turnover rate compared to the general health care population’s 25% turnover rate. This sentence really isn’t a thesis sentence at all, because there’s no argument to support it. A narrow statistic, or a narrow statement of fact, doesn’t offer the writer’s own ideas or analysis about a topic.

Let’s see some examples of potential theses related to the following prompt:

- Bad thesis : The relationship between the American colonists and the British government changed after the French & Indian War.

- Better thesis : The relationship between the American colonists and the British government was strained following the Revolutionary war.

- Best thesis : Due to the heavy debt acquired by the British government during the French & Indian War, the British government increased efforts to tax the colonists, causing American opposition and resistance that strained the relationship between the colonists and the crown.

Practice identifying strong thesis statements in the following interactive.

Supporting Evidence for Thesis Statements

A thesis statement doesn’t mean much without supporting evidence. Oftentimes in a history class, you’ll be expected to defend your thesis, or your argument, using primary source documents. Sometimes these documents are provided to you, and sometimes you’ll need to go find evidence on your own. When the documents are provided for you and you are asked to answer questions about them, it is called a document-based question, or DBQ. You can think of a DBQ like a miniature research paper, where the research has been done for you. DBQs are often used on standardized tests, like this DBQ from the 2004 U.S. History AP exam , which asked students about the altered political, economic, and ideological relations between Britain and the colonies because of the French & Indian War. In this question, students were given 8 documents (A through H) and expected to use these documents to defend and support their argument. For example, here is a possible thesis statement for this essay:

- The French & Indian War altered the political, economic, and ideological relations between the colonists and the British government because it changed the nature of British rule over the colonies, sowed the seeds of discontent, and led to increased taxation from the British.

Now, to defend this thesis statement, you would add evidence from the documents. The thesis statement can also help structure your argument. With the thesis statement above, we could expect the essay to follow this general outline:

- Introduction—introduce how the French and Indian War altered political, economic, and ideological relations between the colonists and the British

- Show the changing map from Doc A and greater administrative responsibility and increased westward expansion

- Discuss Doc B, frustrations from the Iroquois Confederacy and encroachment onto Native lands

- Could also mention Doc F and the result in greater administrative costs

- Use Doc D and explain how a colonial soldier notices disparities between how they are treated when compared to the British

- Use General Washington’s sentiments in Doc C to discuss how these attitudes of reverence shifted after the war. Could mention how the war created leadership opportunities and gave military experience to colonists.

- Use Doc E to highlight how the sermon showed optimism about Britain ruling the colonies after the war

- Highlight some of the political, economic, and ideological differences related to increased taxation caused by the War

- Use Doc F, the British Order in Council Statement, to indicate the need for more funding to pay for the cost of war

- Explain Doc G, frustration from Benjamin Franklin about the Stamp Act and efforts to repeal it

- Use Doc H, the newspaper masthead saying “farewell to liberty”, to highlight the change in sentiments and colonial anger over the Stamp Act

As an example, to argue that the French & Indian War sowed the seeds of discontent, you could mention Document D, from a Massachusetts soldier diary, who wrote, “And we, being here within stone walls, are not likely to get liquors or clothes at this time of the year; and though we be Englishmen born, we are debarred [denied] Englishmen’s liberty.” This shows how colonists began to see their identity as Americans as distinct from those from the British mainland.

Remember, a strong thesis statement is one that supports the argument of your writing. It should have a clear purpose and objective, and although you may revise it as you write, it’s a good idea to start with a strong thesis statement the give your essay direction and organization. You can check the quality of your thesis statement by answering the following questions:

- If a specific prompt was provided, does the thesis statement answer the question prompt?

- Does the thesis statement make sense?

- Is the thesis statement historically accurate?

- Does the thesis statement provide clear and cohesive reasoning?

- Is the thesis supportable by evidence?

thesis statement : a statement of the topic of the piece of writing and the angle the writer has on that topic

- Thesis Statements. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/englishcomp1/wp-admin/post.php?post=576&action=edit . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Thesis Examples. Authored by : Cody Chun, Kieran O'Neil, Kylie Young, Julie Nelson Christoph. Provided by : The University of Puget Sound. Located at : https://soundwriting.pugetsound.edu/universal/thesis-dev-six-steps.html . Project : Sound Writing. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Writing Practice: Building Thesis Statements. Provided by : The Bill of Rights Institute, OpenStax, and contributing authors. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:L3kRHhAr@7/1-22-%F0%9F%93%9D-Writing-Practice-Building-Thesis-Statements . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected].

- Thesis Statement - Writing Tutorials, US History, Dr. Robert Scafe. Provided by : OU Office of Digital Learning. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2hjAk8JI0IY&t=310s . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument

Almost every assignment you complete for a history course will ask you to make an argument. Your instructors will often call this your "thesis"– your position on a subject.

What is an Argument?

An argument takes a stand on an issue. It seeks to persuade an audience of a point of view in much the same way that a lawyer argues a case in a court of law. It is NOT a description or a summary.

- This is an argument: "This paper argues that the movie JFK is inaccurate in its portrayal of President Kennedy."

- This is not an argument: "In this paper, I will describe the portrayal of President Kennedy that is shown in the movie JFK."

What is a Thesis?

A thesis statement is a sentence in which you state an argument about a topic and then describe, briefly, how you will prove your argument.

- This is an argument, but not yet a thesis: "The movie ‘JFK’ inaccurately portrays President Kennedy."

- This is a thesis: "The movie ‘JFK’ inaccurately portrays President Kennedy because of the way it ignores Kennedy’s youth, his relationship with his father, and the findings of the Warren Commission."

A thesis makes a specific statement to the reader about what you will be trying to argue. Your thesis can be a few sentences long, but should not be longer than a paragraph. Do not begin to state evidence or use examples in your thesis paragraph.

A Thesis Helps You and Your Reader

Your blueprint for writing:

- Helps you determine your focus and clarify your ideas.

- Provides a "hook" on which you can "hang" your topic sentences.

- Can (and should) be revised as you further refine your evidence and arguments. New evidence often requires you to change your thesis.

- Gives your paper a unified structure and point.

Your reader’s blueprint for reading:

- Serves as a "map" to follow through your paper.

- Keeps the reader focused on your argument.

- Signals to the reader your main points.

- Engages the reader in your argument.

Tips for Writing a Good Thesis

- Find a Focus: Choose a thesis that explores an aspect of your topic that is important to you, or that allows you to say something new about your topic. For example, if your paper topic asks you to analyze women’s domestic labor during the early nineteenth century, you might decide to focus on the products they made from scratch at home.

- Look for Pattern: After determining a general focus, go back and look more closely at your evidence. As you re-examine your evidence and identify patterns, you will develop your argument and some conclusions. For example, you might find that as industrialization increased, women made fewer textiles at home, but retained their butter and soap making tasks.

Strategies for Developing a Thesis Statement

Idea 1. If your paper assignment asks you to answer a specific question, turn the question into an assertion and give reasons for your opinion.

Assignment: How did domestic labor change between 1820 and 1860? Why were the changes in their work important for the growth of the United States?

Beginning thesis: Between 1820 and 1860 women's domestic labor changed as women stopped producing home-made fabric, although they continued to sew their families' clothes, as well as to produce butter and soap. With the cash women earned from the sale of their butter and soap they purchased ready-made cloth, which in turn, helped increase industrial production in the United States before the Civil War.

Idea 2. Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main Idea: Women's labor in their homes during the first half of the nineteenth century contributed to the growth of the national economy.

Idea 3. Spend time "mulling over" your topic. Make a list of the ideas you want to include in the essay, then think about how to group them under several different headings. Often, you will see an organizational plan emerge from the sorting process.

Idea 4. Use a formula to develop a working thesis statement (which you will need to revise later). Here are a few examples:

- Although most readers of ______ have argued that ______, closer examination shows that ______.

- ______ uses ______ and ______ to prove that ______.

- Phenomenon X is a result of the combination of ______, ______, and ______.

These formulas share two characteristics all thesis statements should have: they state an argument and they reveal how you will make that argument. They are not specific enough, however, and require more work.

As you work on your essay, your ideas will change and so will your thesis. Here are examples of weak and strong thesis statements.

- Unspecific thesis: "Eleanor Roosevelt was a strong leader as First Lady." This thesis lacks an argument. Why was Eleanor Roosevelt a strong leader?

- Specific thesis: "Eleanor Roosevelt recreated the role of the First Lady by her active political leadership in the Democratic Party, by lobbying for national legislation, and by fostering women’s leadership in the Democratic Party." The second thesis has an argument: Eleanor Roosevelt "recreated" the position of First Lady, and a three-part structure with which to demonstrate just how she remade the job.

- Unspecific thesis: "At the end of the nineteenth century French women lawyers experienced difficulty when they attempted to enter the legal profession." No historian could argue with this general statement and uninteresting thesis.

- Specific thesis: "At the end of the nineteenth century French women lawyers experienced misogynist attacks from male lawyers when they attempted to enter the legal profession because male lawyers wanted to keep women out of judgeships." This thesis statement asserts that French male lawyers attacked French women lawyers because they feared women as judges, an intriguing and controversial point.

Making an Argument – Every Thesis Deserves Its Day in Court

You are the best (and only!) advocate for your thesis. Your thesis is defenseless without you to prove that its argument holds up under scrutiny. The jury (i.e., your reader) will expect you, as a good lawyer, to provide evidence to prove your thesis. To prove thesis statements on historical topics, what evidence can an able young lawyer use?

- Primary sources: letters, diaries, government documents, an organization’s meeting minutes, newspapers.

- Secondary sources: articles and books from your class that explain and interpret the historical event or person you are writing about, lecture notes, films or documentaries.

How can you use this evidence?

- Make sure the examples you select from your available evidence address your thesis.

- Use evidence that your reader will believe is credible. This means sifting and sorting your sources, looking for the clearest and fairest. Be sure to identify the biases and shortcomings of each piece of evidence for your reader.

- Use evidence to avoid generalizations. If you assert that all women have been oppressed, what evidence can you use to support this? Using evidence works to check over-general statements.

- Use evidence to address an opposing point of view. How do your sources give examples that refute another historian’s interpretation?

Remember -- if in doubt, talk to your instructor.

Thanks to the web page of the University of Wisconsin at Madison’s Writing Center for information used on this page. See writing.wisc.edu/handbook for further information.

Writing a History Paper

- Reading Your Assignment

- Picking a Topic

Developing a Thesis Statement

- Subject Guide

- Planning Your Research

- Executing Your Research Plan

- Evaluating Your Research

- Writing Your Paper

- Additional Resources

- If We Don't Have What You Need

- History Homepage This link opens in a new window

Usually papers have a thesis, an assertion about your topic. You will present evidence in your paper to convince the reader of your point of view. Some ways to help you develop your thesis are by:

- stating the purpose of the paper

- asking a question and then using the answer to form your thesis statement

- summarizing the main idea of your paper

- listing the ideas you plan to include, then see if they form a group or theme

- using the ponts of controversy, ambiguity, or "issues" to develop a thesis statement

If you're having trouble with your thesis statement, ask your professor for help or visit the Student Academic Success Center: Communication Support . Your thesis may become refined, revised, or changed as your research progresses. Perhaps these sites may be helpful:

- Thesis Statements and Topic Sentences ( CMU Student Academic Success Center : Communication Support)

- Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements (Purdue OWL - Online Writing Lab)

- Developing a Thesis Statement (Writing Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison)

- Thesis Statements (The Writing Center at UNC-Chapel Hill)

- << Previous: Picking a Topic

- Next: Planning Your Research >>

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2022 3:37 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.cmu.edu/historypaper

California History-Social Science Project

Thesis statement, thesis and argument: answers the inquiry question with a thesis statement that is historically defensible and supported by available evidence.

Every history paper has a big idea that serves as an umbrella for all the evidence included in the essay. That umbrella is the argument, or the position the paper aims to prove within the essay. The thesis is the sentence that sums up the historical argument. The Common Core State Standards list the claim, or thesis, as a key element of writing in the history classroom. Beginning, in 9th grade, students should start to develop counterclaims.

Through their writing, students are expected to introduce their thesis, and use it to organize their evidence in the essay. The historical thinking concept should be incorporated into the thesis statement and reflected in the analysis throughout the paper. As a student’s writing develops, their thesis statements will reflect a greater knowledge of the subject at hand, a complexity of the topic under study, and the relationship between their ideas to other relevant issues or trends.

Modeling Thesis Development

When introducing students to writing thesis statements, it is important that they understand that thesis statements are drawn from an analysis of evidence. After conducting an inquiry based on primary and secondary sources, model how to move from the inquiry question, through a summary of evidence derived from relevant sources, to a draft of a thesis statement. Then create opportunities for the student to receive feedback to further refine and develop the thesis.

4 Steps for Developing a Thesis Statement:

- Rewrite the question in your own words and determine the criteria for analysis (categories). Remember to consider the historical thinking concept and how this will guide the argument.

- Review the related evidence. Select relevant and historically significant evidence that addresses the question.

- Sort evidence according to the criteria of analysis (categories), and organize the categories to best develop the argument in the paper.

- State your thesis clearly and concisely.

Example from a 10th-grade Classroom

Inquiry Question: Who started the Russian Revolution?

(Argumentative/Cause & Consequence)

Summary of Relevant Evidence from Primary and Secondary Documents:

- Women initiated a communal strike in the capital protesting the war and food shortages.

- The army supported the Russian people’s street protests against the Czar.

- Soldiers at the front turned against the authority of the state.

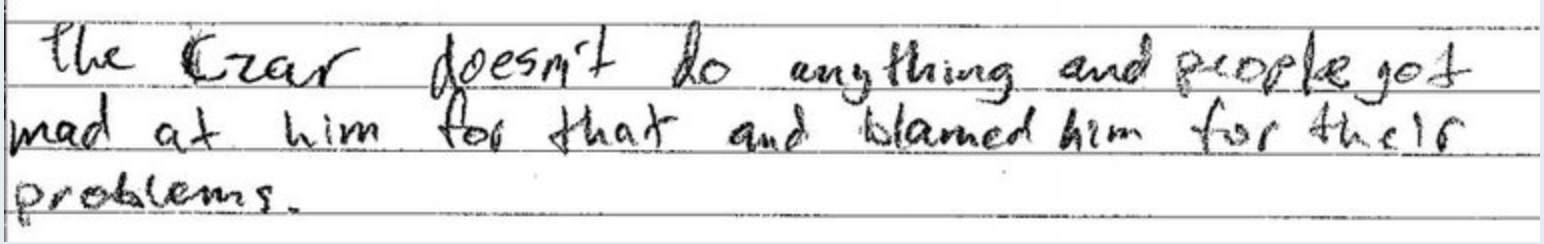

Student Writing: First Draft

Student Writing: Final Thesis

- Request Info

How to Research and Write a Compelling History Thesis

The Importance of Research for Writing a History Thesis

Just as history is more than a collection of facts about past events, an effective history thesis goes beyond simply sharing recorded information. Writing a compelling history thesis requires making an argument about a historical fact and, then, researching and providing a well-crafted defense for that position.

With so many sources available—some of which may provide conflicting findings—how should a student research and write a history thesis? How can a student create a thesis that’s both compelling and supports a position that academic editors describe as “concise, contentious, and coherent”?

Key steps in how to write a history thesis include evaluating source materials, developing a strong thesis statement, and building historical knowledge.

Compelling theses provide context about historical events. This context, according to the reference website ThoughtCo., refers to the social, religious, economic, and political conditions during an occurrence that “enable us to interpret and analyze works or events of the past, or even the future, rather than merely judge them by contemporary standards”.

The context supports the main point of a thesis, called the thesis statement, by providing an interpretive and analytical framework of the facts, instead of simply stating them. Research uncovers the evidence necessary to make the case for that thesis statement.

To gather evidence that contributes to a deeper understanding of a given historical topic, students should reference both primary and secondary sources of research.

Primary Sources

Primary sources are firsthand accounts of events in history, according to Professor David Ulbrich, director of Norwich University’s online Master of Arts in History program. These sources provide information not only about what happened and how it happened but also why it happened.

Primary sources can include letters, diaries, photos, and videos as well as material objects such as “spent artillery shells, architectural features, cemetery headstones, chemical analysis of substances, shards of bowls or bottles, farming implements, or earth or environmental features or factors,” Ulbrich says. “The author of the thesis can tell how people lived, for example, by the ways they arranged their material lives.”

Primary research sources are the building blocks to help us better understand and appreciate history. It is critical to find as many primary sources from as many perspectives as possible. Researching these firsthand accounts can provide evidence that helps answer those “what”, “how”, and “why” questions about the past, Ulbrich says.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources are materials—such as books, articles, essays, and documentaries—gathered and interpreted by other researchers. These sources often provide updates and evaluation of the thesis topic or viewpoints that support the theories presented in the thesis.

Primary and secondary sources are complementary types of research that form a convincing foundation for a thesis’ main points.

How to Write a History Thesis

What are the steps to write a history thesis? The process of developing a thesis that provides a thorough analysis of a historical event—and presents academically defensible arguments related to that analysis—includes the following:

1. Gather and Analyze Sources

When collecting sources to use in a thesis, students should analyze them to ensure they demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the materials. A student should evaluate the attributes of sources such as their origin and point-of-view.

An array of primary and secondary sources can help provide a thorough understanding of a historical event, although some of those sources may include conflicting views and details. In those cases, the American Historical Association says, it’s up to the thesis author to determine which source reflects the appropriate point-of-view.

2. Develop a Thesis Statement

To create a thesis statement, a student should establish a specific idea or theory that makes the main point about a historical event. Scribbr, an editing website, recommends starting with a working thesis, asking the question the thesis intends to answer, and, then, writing the answer.

The final version of a thesis statement might be argumentative, for example, taking a side in a debate. Or it might be expository, explaining a historical situation. In addition to being concise and coherent, a thesis statement should be contentious, meaning it requires evidence to support it.

3. Create an Outline

Developing a thesis requires an outline of the content that will support the thesis statement. Students should keep in mind the following key steps in creating their outline:

- Note major points.

- Categorize ideas supported by the theories.

- Arrange points according to the importance and a timeline of events addressed by the thesis.

- Create effective headings and subheadings.

- Format the outline.

4. Organize Information

Thesis authors should ensure their content follows a logical order. This may entail coding resource materials to help match them to the appropriate theories while organizing the information. A thesis typically contains the following elements.

- Abstract —Overview of the thesis.

- Introduction —Summary of the thesis’ main points.

- Literature review —Explanation of the gap in previous research addressed by this thesis.

- Methods —Outline how the author reviewed the research and why materials were selected.

- Results —Description of the research findings.

- Discussion —Analysis of the research.

- Conclusion —Statements about what the student learned.

5. Write the Thesis

Online writing guide Paperpile recommends that students start with the literature review when writing the thesis. Developing this section first will help the author gain a more complete understanding of the thesis’ source materials. Writing the abstract last can give the student a thorough picture of the work the abstract should describe.

The discussion portion of the thesis typically is the longest since it’s here that the writer will explain the limitations of the work, offer explanations of any unexpected results, and cite remaining questions about the topic.

In writing the thesis, the author should keep in mind that the document will require multiple changes and drafts—perhaps even new insights. A student should gather feedback from a professor and colleagues to ensure their thesis is clear and effective before finalizing the draft.

6. Prepare to Defend the Thesis

A committee will evaluate the student’s defense of the thesis’ theories. Students should prepare to defend their thesis by considering answers to questions posed by the committee. Additionally, students should develop a plan for addressing questions to which they may not have a ready answer, understanding the evaluation likely will consider how the author handles that challenge.

Developing Skills to Write a Compelling History Thesis

When looking for direction on how to write a history thesis, Norwich University’s online Master of Arts in History program can provide the needed skills and knowledge. The program’s tracks and several courses—taken as core classes or as electives in multiple concentrations—can provide a strong foundation for thesis work.

Master of Arts in History Tracks

In the Norwich online Master of Arts in History program, respected scholars help students improve their historical insight, research, writing, analytical, and presentation skills. They teach the following program tracks.

- Public History —Focuses on the preservation and interpretation of historic documents and artifacts for purposes of public observation.

- American History —Emphasizes the exploration and interpretation of key events associated with U.S. history.

- World History —Prepares students to develop an in-depth understanding of world history from various eras.

- Legal and Constitutional History —Provides a thorough study of the foundational legal and constitutional elements in the U.S. and Europe.

Master of Arts in History Courses

Norwich University’s online Master of Arts in History program enables students to customize studies based on career goals and personal interests through the following courses:

- Introduction to History and Historiography —Covers the core concepts of history-based study and research methodology, highlighting how these concepts are essential to developing an effective history thesis.

- Directed Readings in History —Highlights different ways to use sources that chronicle American history to assist in researching and writing a thorough and complete history thesis.

- Race, Gender, and U.S. Constitution —Explores key U.S. Supreme Court decisions relating to national race and gender relations and rights, providing a deeper context to develop compelling history theses.

- Archival Studies —Breaks down the importance of systematically overseeing archival materials, highlighting how to build historical context to better educate and engage with the public.

Start Your Path Toward Writing a Compelling History Thesis

For over two centuries, Norwich University has played a vital role in history as America’s first private military college and the birthplace of the ROTC. As such, the university is uniquely positioned to lead students through a comprehensive analysis of the major developments, events, and figures of the past.

Explore Norwich University’s online Master of Arts in History program. Start your path toward writing a compelling history thesis and taking your talents further.

Writing History: An Introductory Guide to How History Is Produced , American Historical Association How to Write a Thesis Statement , Scribbr The Importance of Historic Context in Analysis and Interpretation , ThoughtCo. 7 Reasons Why Research Is Important , Owlcation Primary and Secondary Sources , Scribbr Secondary Sources in Research , ThoughtCo. Analysis of Sources , History Skills Research Paper Outline , Scribbr How to Structure a Thesis , Paperpile Writing Your Final Draft , History Skills How to Prepare an Excellent Thesis Defense , Paperpile

Explore Norwich University

Your future starts here.

- 30+ On-Campus Undergraduate Programs

- 16:1 Student-Faculty Ratio

- 25+ Online Grad and Undergrad Programs

- Military Discounts Available

- 22 Varsity Athletic Teams

Future Leader Camp

Join us for our challenging military-style summer camp where we will inspire you to push beyond what you thought possible:

- Session I July 13 - 21, 2024

- Session II July 27 - August 4, 2024

Explore your sense of adventure, have fun, and forge new friendships. High school students and incoming rooks, discover the leader you aspire to be – today.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Write a History Research Paper

In my last post, I shared some tips on how to conduct research in history and emphasized that researchers should keep in mind a source’s category (transcript, court document, speech, etc.). This post is something of a sequel to that, as I will share some thoughts on what often follows primary-source research: a history research paper.

1. Background Reading The first step to a history research paper is of course, background reading and research. In the context of a class assignment, “background reading” might simply be course readings or lectures, but for independent work, this step will likely involve some quality time on your own in the library. During the background reading phase of your project, keep an eye out for intriguing angles to approach your topic from and any trends that you see across sources (both primary and secondary).

2. T hemes and Context Recounting the simple facts about your topic alone will not make for a successful research paper. One must grasp both the details of events as well as the larger, thematic context of the time period in which they occurred. What’s the scholarly consensus about these themes? Does that consensus seem right to you, after having done primary and secondary research of your own?

3. Develop an Argument Grappling with answers to the above questions will get you thinking about your emerging argument. For shorter papers, you might identify a gap in the scholarship or come up with an argumentative response to a class prompt rather quickly. Remember: as an undergraduate, you don’t have to come up with (to borrow Philosophy Professor Gideon Rosen’s phrase) ‘a blindingly original theory of everything.’ In other words, finding a nuanced thesis does not mean you have to disprove some famous scholar’s work in its entirety. But, if you’re having trouble defining your thesis, I encourage you not to worry; talk to your professor, preceptor, or, if appropriate, a friend. These people can listen to your ideas, and the simple act of talking about your paper can often go a long way in helping you realize what you want to write about.

4. Outline Your Argument With a history paper specifically, one is often writing about a sequence of events and trying to tell a story about what happened. Roughly speaking, your thesis is your interpretation of these events, or your take on some aspect of them (i.e. the role of women in New Deal programs). Before opening up Word, I suggest writing down the stages of your argument. Then, outline or organize your notes to know what evidence you’ll use in each of these various stages. If you think your evidence is solid, then you’re probably ready to start writing—and you now have a solid roadmap to work from! But, if this step is proving difficult, you might want to gather more evidence or go back to the thesis drawing board and look for a better angle. I often find myself somewhere between these two extremes (being 100% ready to write or staring at a sparse outline), but that’s also helpful, because it gives me a better idea of where my argument needs strengthening.

5. Prepare Yourself Once you have some sort of direction for the paper (i.e. a working thesis), you’re getting close to the fun part—the writing itself. Gather your laptop, your research materials/notes, and some snacks, and get ready to settle in to write your paper, following your argument outline. As mentioned in the photo caption, I suggest utilizing large library tables to spread out your notes. This way, you don’t have to constantly flip through binders, notebooks, and printed drafts.

In addition to this step by step approach, I’ll leave you with a few last general tips for approaching a history research paper. Overall, set reasonable goals for your project, and remember that a seemingly daunting task can be broken down into the above constituent phases. And, if nothing else, know that you’ll end up with a nice Word document full of aesthetically pleasing footnotes!

— Shanon FitzGerald, Social Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Writing a Good History Paper

- Top Ten Reasons for Negative Comments

- Making Sure your Paper has Substance

Common Marginal Remarks on Style, Clarity, Grammar, and Syntax

Word and phrase usage problems, analyzing a historical document, writing a book review, writing a term paper or senior thesis, top ten reasons for negative comments on history papers.

(Drawn from a survey of the History Department ) 10. You engage in cheap, anachronistic moralizing . 9. You are sloppy with the chronology . 8. You quote excessively or improperly . 7. You have written a careless “one-draft wonder.” (See revise and proofread) 6. You are vague or have empty, unsupported generalizations . 5. You write too much in the passive voice. 4. You use inappropriate sources . 3. You use evidence uncritically. 2. You are wordy . 1. You have no clear thesis and little analysis.

Making Sure your History Paper has Substance

Get off to a good start..

Avoid pretentious, vapid beginnings. If you are writing a paper on, say, British responses to the rebellion in India in 1857, don't open with a statement like this: “Throughout human history people in all cultures everywhere in the world have engaged in many and long-running conflicts about numerous aspects of government policy and diplomatic issues, which have much interested historians and generated historical theories in many areas.” This is pure garbage, bores the reader, and is a sure sign that you have nothing substantive to say. Get to the point. Here’s a better start: “The rebellion in 1857 compelled the British to rethink their colonial administration in India.” This sentence tells the reader what your paper is actually about and clears the way for you to state your thesis in the rest of the opening paragraph. For example, you might go on to argue that greater British sensitivity to Indian customs was hypocritical.

State a clear thesis.

Whether you are writing an exam essay or a senior thesis, you need to have a thesis. Don’t just repeat the assignment or start writing down everything that you know about the subject. Ask yourself, “What exactly am I trying to prove?” Your thesis is your take on the subject, your perspective, your explanation—that is, the case that you’re going to argue. “Famine struck Ireland in the 1840s” is a true statement, but it is not a thesis. “The English were responsible for famine in Ireland in the 1840s” is a thesis (whether defensible or not is another matter). A good thesis answers an important research question about how or why something happened. (“Who was responsible for the famine in Ireland in the 1840s?”) Once you have laid out your thesis, don’t forget about it. Develop your thesis logically from paragraph to paragraph. Your reader should always know where your argument has come from, where it is now, and where it is going.

Be sure to analyze.

Students are often puzzled when their professors mark them down for summarizing or merely narrating rather than analyzing. What does it mean to analyze? In the narrow sense, to analyze means to break down into parts and to study the interrelationships of those parts. If you analyze water, you break it down into hydrogen and oxygen. In a broader sense, historical analysis explains the origins and significance of events. Historical analysis digs beneath the surface to see relationships or distinctions that are not immediately obvious. Historical analysis is critical; it evaluates sources, assigns significance to causes, and weighs competing explanations. Don’t push the distinction too far, but you might think of summary and analysis this way: Who, what, when, and where are the stuff of summary; how, why, and to what effect are the stuff of analysis. Many students think that they have to give a long summary (to show the professor that they know the facts) before they get to their analysis. Try instead to begin your analysis as soon as possible, sometimes without any summary at all. The facts will “shine through” a good analysis. You can't do an analysis unless you know the facts, but you can summarize the facts without being able to do an analysis. Summary is easier and less sophisticated than analysis—that’s why summary alone never earns an “A.”

Use evidence critically.

Like good detectives, historians are critical of their sources and cross-check them for reliability. You wouldn't think much of a detective who relied solely on a suspect’s archenemy to check an alibi. Likewise, you wouldn't think much of a historian who relied solely on the French to explain the origins of World War I. Consider the following two statements on the origin of World War I: 1) “For the catastrophe of 1914 the Germans are responsible. Only a professional liar would deny this...” 2) “It is not true that Germany is guilty of having caused this war. Neither the people, the government, nor the Kaiser wanted war....” They can’t both be right, so you have to do some detective work. As always, the best approach is to ask: Who wrote the source? Why? When? Under what circumstances? For whom? The first statement comes from a book by the French politician Georges Clemenceau, which he wrote in 1929 at the very end of his life. In 1871, Clemenceau had vowed revenge against Germany for its defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War. As premier of France from 1917 to 1920, he represented France at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. He was obviously not a disinterested observer. The second statement comes from a manifesto published by ninety-three prominent German intellectuals in the fall of 1914. They were defending Germany against charges of aggression and brutality. They too were obviously not disinterested observers. Now, rarely do you encounter such extreme bias and passionate disagreement, but the principle of criticizing and cross-checking sources always applies. In general, the more sources you can use, and the more varied they are, the more likely you are to make a sound historical judgment, especially when passions and self-interests are engaged. You don’t need to be cynical as a historian (self-interest does not explain everything), but you do need to be critical and skeptical. Competent historians may offer different interpretations of the same evidence or choose to stress different evidence. You will not find a single historical Truth with a capital “T” on any matter of significance. You can, however, learn to discriminate among conflicting interpretations, not all of which are created equal. (See also: Analyzing a Historical Document )

Be precise.

Vague statements and empty generalizations suggest that you haven't put in the time to learn the material. Consider these two sentences: “During the French Revolution, the government was overthrown by the people. The Revolution is important because it shows that people need freedom.” What people? Landless peasants? Urban journeymen? Wealthy lawyers? Which government? When? How? Who exactly needed freedom, and what did they mean by freedom? Here is a more precise statement about the French Revolution: “Threatened by rising prices and food shortages in 1793, the Parisian sans-culottes pressured the Convention to institute price controls.” This statement is more limited than the grandiose generalizations about the Revolution, but unlike them, it can open the door to a real analysis of the Revolution. Be careful when you use grand abstractions like people, society, freedom, and government, especially when you further distance yourself from the concrete by using these words as the apparent antecedents for the pronouns they and it. Always pay attention to cause and effect. Abstractions do not cause or need anything; particular people or particular groups of people cause or need things. Avoid grandiose trans-historical generalizations that you can’t support. When in doubt about the appropriate level of precision or detail, err on the side of adding “too much” precision and detail.

Watch the chronology.

Anchor your thesis in a clear chronological framework and don't jump around confusingly. Take care to avoid both anachronisms and vagueness about dates. If you write, “Napoleon abandoned his Grand Army in Russia and caught the redeye back to Paris,” the problem is obvious. If you write, “Despite the Watergate scandal, Nixon easily won reelection in 1972,” the problem is more subtle, but still serious. (The scandal did not become public until after the election.) If you write, “The revolution in China finally succeeded in the twentieth century,” your professor may suspect that you haven’t studied. Which revolution? When in the twentieth century? Remember that chronology is the backbone of history. What would you think of a biographer who wrote that you graduated from Hamilton in the 1950s?

Cite sources carefully.

Your professor may allow parenthetical citations in a short paper with one or two sources, but you should use footnotes for any research paper in history. Parenthetical citations are unaesthetic; they scar the text and break the flow of reading. Worse still, they are simply inadequate to capture the richness of historical sources. Historians take justifiable pride in the immense variety of their sources. Parenthetical citations such as (Jones 1994) may be fine for most of the social sciences and humanities, where the source base is usually limited to recent books and articles in English. Historians, however, need the flexibility of the full footnote. Try to imagine this typical footnote (pulled at random from a classic work of German history) squeezed into parentheses in the body of the text: DZA Potsdam, RdI, Frieden 5, Erzgebiet von Longwy-Briey, Bd. I, Nr. 19305, gedruckte Denkschrift für OHL und Reichsleitung, Dezember 1917, und in RWA, Frieden Frankreich Nr. 1883. The abbreviations are already in this footnote; its information cannot be further reduced. For footnotes and bibliography, historians usually use Chicago style. (The Chicago Manual of Style. 15th edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.) On the Writing Center’s website you can find a useful summary of Chicago citation style prepared by a former history major, Elizabeth Rabe ’04 ( Footnotes ). RefWorks (on the library’s website) will convert your citations to Chicago style. Don’t hesitate to ask one of the reference librarians for help if you have trouble getting started on RefWorks.

Use primary sources.

Use as many primary sources as possible in your paper. A primary source is one produced by a participant in or witness of the events you are writing about. A primary source allows the historian to see the past through the eyes of direct participants. Some common primary sources are letters, diaries, memoirs, speeches, church records, newspaper articles, and government documents of all kinds. The capacious genre “government records” is probably the single richest trove for the historian and includes everything from criminal court records, to tax lists, to census data, to parliamentary debates, to international treaties—indeed, any records generated by governments. If you’re writing about culture, primary sources may include works of art or literature, as well as philosophical tracts or scientific treatises—anything that comes under the broad rubric of culture. Not all primary sources are written. Buildings, monuments, clothes, home furnishings, photographs, religious relics, musical recordings, or oral reminiscences can all be primary sources if you use them as historical clues. The interests of historians are so broad that virtually anything can be a primary source. (See also: Analyzing a Historical Document )

Use scholarly secondary sources.

A secondary source is one written by a later historian who had no part in what he or she is writing about. (In the rare cases when the historian was a participant in the events, then the work—or at least part of it—is a primary source.) Historians read secondary sources to learn about how scholars have interpreted the past. Just as you must be critical of primary sources, so too you must be critical of secondary sources. You must be especially careful to distinguish between scholarly and non-scholarly secondary sources. Unlike, say, nuclear physics, history attracts many amateurs. Books and articles about war, great individuals, and everyday material life dominate popular history. Some professional historians disparage popular history and may even discourage their colleagues from trying their hand at it. You need not share their snobbishness; some popular history is excellent. But—and this is a big but—as a rule, you should avoid popular works in your research, because they are usually not scholarly. Popular history seeks to inform and entertain a large general audience. In popular history, dramatic storytelling often prevails over analysis, style over substance, simplicity over complexity, and grand generalization over careful qualification. Popular history is usually based largely or exclusively on secondary sources. Strictly speaking, most popular histories might better be called tertiary, not secondary, sources. Scholarly history, in contrast, seeks to discover new knowledge or to reinterpret existing knowledge. Good scholars wish to write clearly and simply, and they may spin a compelling yarn, but they do not shun depth, analysis, complexity, or qualification. Scholarly history draws on as many primary sources as practical. Now, your goal as a student is to come as close as possible to the scholarly ideal, so you need to develop a nose for distinguishing the scholarly from the non-scholarly. Here are a few questions you might ask of your secondary sources (bear in mind that the popular/scholarly distinction is not absolute, and that some scholarly work may be poor scholarship). Who is the author? Most scholarly works are written by professional historians (usually professors) who have advanced training in the area they are writing about. If the author is a journalist or someone with no special historical training, be careful. Who publishes the work? Scholarly books come from university presses and from a handful of commercial presses (for example, Norton, Routledge, Palgrave, Penguin, Rowman & Littlefield, Knopf, and HarperCollins). If it’s an article, where does it appear? Is it in a journal subscribed to by our library, listed on JSTOR , or published by a university press? Is the editorial board staffed by professors? Oddly enough, the word journal in the title is usually a sign that the periodical is scholarly. What do the notes and bibliography look like? If they are thin or nonexistent, be careful. If they are all secondary sources, be careful. If the work is about a non-English-speaking area, and all the sources are in English, then it's almost by definition not scholarly. Can you find reviews of the book in the data base Academic Search Premier? If the book was published within the last few decades, and it’s not in there, that’s a bad sign. With a little practice, you can develop confidence in your judgment—and you’re on your way to being a historian. If you are unsure whether a work qualifies as scholarly, ask your professor. (See also: Writing a Book Review )

Avoid abusing your sources.

Many potentially valuable sources are easy to abuse. Be especially alert for these five abuses: Web abuse. The Web is a wonderful and improving resource for indexes and catalogs. But as a source for primary and secondary material for the historian, the Web is of limited value. Anyone with the right software can post something on the Web without having to get past trained editors, peer reviewers, or librarians. As a result, there is a great deal of garbage on the Web. If you use a primary source from the Web, make sure that a respected intellectual institution stands behind the site. Be especially wary of secondary articles on the Web, unless they appear in electronic versions of established print journals (e.g., The Journal of Asian Studies in JSTOR). Many articles on the Web are little more than third-rate encyclopedia entries. When in doubt, check with your professor. With a few rare exceptions, you will not find scholarly monographs in history (even recent ones) on the Web. You may have heard of Google’s plans to digitize the entire collections of some of the world’s major libraries and to make those collections available on the Web. Don’t hold your breath. Your days at Hamilton will be long over by the time the project is finished. Besides, your training as a historian should give you a healthy skepticism of the giddy claims of technophiles. Most of the time and effort of doing history goes into reading, note-taking, pondering, and writing. Finding a chapter of a book on the Web (as opposed to getting the physical book through interlibrary loan) might be a convenience, but it doesn’t change the basics for the historian. Moreover, there is a subtle, but serious, drawback with digitized old books: They break the historian’s sensual link to the past. And of course, virtually none of the literally trillions of pages of archival material is available on the Web. For the foreseeable future, the library and the archive will remain the natural habitats of the historian. Thesaurus abuse. How tempting it is to ask your computer’s thesaurus to suggest a more erudite-sounding word for the common one that popped into your mind! Resist the temptation. Consider this example (admittedly, a bit heavy-handed, but it drives the point home): You’re writing about the EPA’s programs to clean up impure water supplies. Impure seems too simple and boring a word, so you bring up your thesaurus, which offers you everything from incontinent to meretricious. “How about meretricious water?” you think to yourself. “That will impress the professor.” The problem is that you don’t know exactly what meretricious means, so you don’t realize that meretricious is absurdly inappropriate in this context and makes you look foolish and immature. Use only those words that come to you naturally. Don’t try to write beyond your vocabulary. Don’t try to impress with big words. Use a thesaurus only for those annoying tip-of-the-tongue problems (you know the word and will recognize it instantly when you see it, but at the moment you just can’t think of it). Quotation book abuse. This is similar to thesaurus abuse. Let’s say you are writing a paper on Alexander Hamilton’s banking policies, and you want to get off to a snappy start that will make you seem effortlessly learned. How about a quotation on money? You click on the index of Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations , and before you know it, you’ve begun your paper with, “As Samuel Butler wrote in Hudibras , ‘For what is worth in anything/ But so much money as ’t will bring?’” Face it, you’re faking it. You don’t know who Samuel Butler is, and you’ve certainly never heard of Hudibras , let alone read it. Your professor is not fooled. You sound like an insecure after-dinner speaker. Forget Bartlett’s, unless you're confirming the wording of a quotation that came to you spontaneously and relates to your paper. Encyclopedia abuse. General encyclopedias like Britannica are useful for checking facts (“Wait a sec, am I right about which countries sent troops to crush the Boxer Rebellion in China? Better check.”). But if you are footnoting encyclopedias in your papers, you are not doing college-level research.

Dictionary Abuse. The dictionary is your friend. Keep it by your side as you write, but do not abuse it by starting papers with a definition. You may be most tempted to start this way when you are writing on a complex, controversial, or elusive subject. (“According to Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary , liberalism is defined as...”). Actually, the dictionary does you little good in such cases and makes you sound like a conscientious but dull high-school student. Save in the rare case that competing dictionary definitions are the subject at hand, keep dictionary quotations out of your paper.

Quote sparingly

Avoid quoting a secondary source and then simply rewording or summarizing the quotation, either above or below the quotation. It is rarely necessary to quote secondary sources at length, unless your essay focuses on a critical analysis of the author’s argument. (See also: Writing a Book Review ) Your professor wants to see your ability to analyze and to understand the secondary sources. Do not quote unless the quotation clarifies or enriches your analysis. When in doubt, do not quote; instead, integrate the author’s argument into your own (though be sure to acknowledge ideas from your sources, even when you are paraphrasing). If you use a lot of quotations from secondary sources, you are probably writing a poor paper. An analysis of a primary source, such as a political tract or philosophical essay, might require lengthy quotations, often in block format. In such cases, you might need to briefly repeat key points or passages as a means to introduce the author’s ideas, but your analysis and interpretation of the text’s meaning should remain the most important aim. (See also: Using primary sources and Use scholarly secondary sources .)

Know your audience

Unless instructed otherwise, you should assume that your audience consists of educated, intelligent, nonspecialists. In fact, your professor will usually be your only reader, but if you write directly to your professor, you may become cryptic or sloppy (oh well, she’ll know what I’m talking about). Explaining your ideas to someone who doesn't know what you mean forces you to be clear and complete. Now, finding the right amount of detail can, admittedly, be tricky (how much do I put in about the Edict of Nantes, the Embargo Act, or President Wilson’s background?). When in doubt, err on the side of putting in extra details. You’ll get some leeway here if you avoid the extremes (my reader’s an ignoramus/my reader knows everything).

Avoid cheap, anachronistic moralizing

Many of the people and institutions of the past appear unenlightened, ignorant, misguided, or bigoted by today’s values. Resist the temptation to condemn or to get self-righteous. (“Martin Luther was blind to the sexism and class prejudice of sixteenth-century German society.”) Like you, people in the past were creatures of their time; like you, they deserve to be judged by the standards of their time. If you judge the past by today’s standards (an error historians call “presentism”), you will never understand why people thought or acted as they did. Yes, Hitler was a bad guy, but he was bad not only by today’s standards, but also by the commonly accepted standards of his own time. Someday you’re going to look pretty foolish and ignorant yourself. (“Early twenty-first century Hamilton students failed to see the shocking inderdosherism [that’s right, you don’t recognize the concept because it doesn’t yet exist] implicit in their career plans.”)

Have a strong conclusion

Obviously, you should not just stop abruptly as though you have run out of time or ideas. Your conclusion should conclude something. If you merely restate briefly what you have said in your paper, you give the impression that you are unsure of the significance of what you have written. A weak conclusion leaves the reader unsatisfied and bewildered, wondering why your paper was worth reading. A strong conclusion adds something to what you said in your introduction. A strong conclusion explains the importance and significance of what you have written. A strong conclusion leaves your reader caring about what you have said and pondering the larger implications of your thesis. Don’t leave your reader asking, “So what?”

Revise and proofread

Your professor can spot a “one-draft wonder,” so don't try to do your paper at the last moment. Leave plenty of time for revising and proofreading. Show your draft to a writing tutor or other good writer. Reading the draft aloud may also help. Of course, everyone makes mistakes, and a few may slip through no matter how meticulous you are. But beware of lots of mistakes. The failure to proofread carefully suggests that you devoted little time and effort to the assignment. Tip: Proofread your text both on the screen and on a printed copy. Your eyes see the two differently. Don’t rely on your spell checker to catch all of your misspellings. (If ewe ken reed this ewe kin sea that a computer wood nut all ways help ewe spill or rite reel good.)

Note: The Writing Center suggests standard abbreviations for noting some of these problems. You should familiarize yourself with those abbreviations, but your professor may not use them.

Remarks on Style and Clarity

Wordy/verbose/repetitive..

Try your hand at fixing this sentence: “Due to the fact that these aspects of the issue of personal survival have been raised by recently transpired problematic conflicts, it is at the present time paramount that the ultimate psychological end of suicide be contemplated by this individual.” If you get it down to “To be or not to be, that is the question,” you’ve done well. You may not match Shakespeare, but you can learn to cut the fat out of your prose. The chances are that the five pages you’ve written for your history paper do not really contain five pages’ worth of ideas.

Misuse of the passive voice.

Write in the active voice. The passive voice encourages vagueness and dullness; it enfeebles verbs; and it conceals agency, which is the very stuff of history. You know all of this almost instinctively. What would you think of a lover who sighed in your ear, “My darling, you are loved by me!”? At its worst, the passive voice—like its kin, bureaucratic language and jargon—is a medium for the dishonesty and evasion of responsibility that pervade contemporary American culture. (“Mistakes were made; I was given false information.” Now notice the difference: “I screwed up; Smith and Jones lied to me; I neglected to check the facts.”) On history papers the passive voice usually signals a less toxic version of the same unwillingness to take charge, to commit yourself, and to say forthrightly what is really going on, and who is doing what to whom. Suppose you write, “In 1935 Ethiopia was invaded.” This sentence is a disaster. Who invaded? Your professor will assume that you don't know. Adding “by Italy” to the end of the sentence helps a bit, but the sentence is still flat and misleading. Italy was an aggressive actor, and your passive construction conceals that salient fact by putting the actor in the syntactically weakest position—at the end of the sentence as the object of a preposition. Notice how you add vigor and clarity to the sentence when you recast it in the active voice: "In 1935 Italy invaded Ethiopia." I n a few cases , you may violate the no-passive-voice rule. The passive voice may be preferable if the agent is either obvious (“Kennedy was elected in 1960”), irrelevant (“Theodore Roosevelt became president when McKinley was assassinated”), or unknown (“King Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings”). Note that in all three of these sample sentences the passive voice focuses the reader on the receiver of the action rather than on the doer (on Kennedy, not on American voters; on McKinley, not on his assassin; on King Harold, not on the unknown Norman archer). Historians usually wish to focus on the doer, so you should stay with the active voice—unless you can make a compelling case for an exception.

Abuse of the verb to be.

The verb to be is the most common and most important verb in English, but too many verbs to be suck the life out of your prose and lead to wordiness. Enliven your prose with as many action verbs as possible. ( “In Brown v. Board of Education it was the opinion of the Supreme Court that the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ was in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.”) Rewrite as “ In Brown v. Board of Education the Supreme Court ruled that the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ violated the Fourteenth ”

Explain/what’s your point?/unclear/huh?

You may (or may not) know what you’re talking about, but if you see these marginal comments, you have confused your reader. You may have introduced a non sequitur ; gotten off the subject; drifted into abstraction; assumed something that you have not told the reader; failed to explain how the material relates to your argument; garbled your syntax; or simply failed to proofread carefully. If possible, have a good writer read your paper and point out the muddled parts. Reading your paper aloud may help too.

Paragraph goes nowhere/has no point or unity.

Paragraphs are the building blocks of your paper. If your paragraphs are weak, your paper cannot be strong. Try underlining the topic sentence of every paragraph. If your topic sentences are vague, strength and precision—the hallmarks of good writing—are unlikely to follow. Consider this topic sentence (from a paper on Ivan the Terrible): “From 1538 to 1547, there are many different arguments about the nature of what happened.” Disaster looms. The reader has no way of knowing when the arguing takes place, who’s arguing, or even what the arguing is about. And how does the “nature of what happened” differ from plain “what happened”? Perhaps the writer means the following: “The childhood of Ivan the Terrible has provoked controversy among scholars of Russian history.” That's hardly deathless prose, but it does orient the reader and make the writer accountable for what follows in the paragraph. Once you have a good topic sentence, make sure that everything in the paragraph supports that sentence, and that cumulatively the support is persuasive. Make sure that each sentence follows logically from the previous one, adding detail in a coherent order. Move, delete, or add material as appropriate. To avoid confusing the reader, limit each paragraph to one central idea. (If you have a series of supporting points starting with first, you must follow with a second, third , etc.) A paragraph that runs more than a printed page is probably too long. Err on the side of shorter paragraphs.

Inappropriate use of first person.

Most historians write in the third person, which focuses the reader on the subject. If you write in the first person singular, you shift the focus to yourself. You give the impression that you want to break in and say, “Enough about the Haitian revolution [or whatever], now let’s talk about me!” Also avoid the first person plural (“We believe...”). It suggests committees, editorial boards, or royalty. None of those should have had a hand in writing your paper. And don’t refer to yourself lamely as “this writer.” Who else could possibly be writing the paper?

Tense inconsistency.

Stay consistently in the past tense when you are writing about what took place in the past. (“Truman’s defeat of Dewey in 1948 caught the pollsters by surprise.”) Note that the context may require a shift into the past perfect. (“The pollsters had not realized [past perfect] that voter opinion had been [past perfect] changing rapidly in the days before the election.”) Unfortunately, the tense problem can get a bit more complicated. Most historians shift into the present tense when describing or commenting on a book, document, or evidence that still exists and is in front of them (or in their mind) as they write. (“de Beauvoir published [past tense] The Second Sex in 1949. In the book she contends [present tense] that woman....”) If you’re confused, think of it this way: History is about the past, so historians write in the past tense, unless they are discussing effects of the past that still exist and thus are in the present. When in doubt, use the past tense and stay consistent.

Ill-fitted quotation.

This is a common problem, though not noted in stylebooks. When you quote someone, make sure that the quotation fits grammatically into your sentence. Note carefully the mismatch between the start of the following sentence and the quotation that follows: “In order to understand the Vikings, writes Marc Bloch, it is necessary, ‘To conceive of the Viking expeditions as religious warfare inspired by the ardour of an implacable pagan fanaticism—an explanation that has sometimes been at least suggested—conflicts too much with what we know of minds disposed to respect magic of every kind.’” At first, the transition into the quotation from Bloch seems fine. The infinitive (to conceive) fits. But then the reader comes to the verb (conflicts) in Bloch’s sentence, and things no longer make sense. The writer is saying, in effect, “it is necessary conflicts.” The wordy lead-in and the complex syntax of the quotation have tripped the writer and confused the reader. If you wish to use the whole sentence, rewrite as “Marc Bloch writes in Feudal Society , ‘To conceive of...’” Better yet, use your own words or only part of the quotation in your sentence. Remember that good writers quote infrequently, but when they do need to quote, they use carefully phrased lead-ins that fit the grammatical construction of the quotation.

Free-floating quotation.

Do not suddenly drop quotations into your prose. (“The spirit of the Progressive era is best understood if one remembers that the United States is ‘the only country in the world that began with perfection and aspired to progress.’”) You have probably chosen the quotation because it is finely wrought and says exactly what you want to say. Fine, but first you inconvenience the reader, who must go to the footnote to learn that the quotation comes from The Age of Reform by historian Richard Hofstadter. And then you puzzle the reader. Did Hofstadter write the line about perfection and progress, or is he quoting someone from the Progressive era? If, as you claim, you are going to help the reader to judge the “spirit of the Progressive era,” you need to clarify. Rewrite as “As historian Richard Hofstadter writes in the Age of Reform , the United States is ‘the only country in the world...’” Now the reader knows immediately that the line is Hofstadter’s.

Who’s speaking here?/your view?

Always be clear about whether you’re giving your opinion or that of the author or historical actor you are discussing. Let’s say that your essay is about Martin Luther’s social views. You write, “The German peasants who revolted in 1525 were brutes and deserved to be crushed mercilessly.” That’s what Luther thought, but do you agree? You may know, but your reader is not a mind reader. When in doubt, err on the side of being overly clear.

Jargon/pretentious theory.

Historians value plain English. Academic jargon and pretentious theory will make your prose turgid, ridiculous, and downright irritating. Your professor will suspect that you are trying to conceal that you have little to say. Of course, historians can’t get along without some theory; even those who profess to have no theory actually do—it’s called naïve realism. And sometimes you need a technical term, be it ontological argument or ecological fallacy. When you use theory or technical terms, make sure that they are intelligible and do real intellectual lifting. Please, no sentences like this: “By means of a neo-Althusserian, post-feminist hermeneutics, this essay will de/construct the logo/phallo/centrism imbricated in the marginalizing post-colonial gendered gaze, thereby proliferating the subjectivities that will re/present the de/stabilization of the essentializing habitus of post-Fordist capitalism.”

Informal language/slang.

You don’t need to be stuffy, but stay with formal English prose of the kind that will still be comprehensible to future generations. Columbus did not “push the envelope in the Atlantic.” Henry VIII was not “looking for his inner child when he broke with the Church.” Prime Minister Cavour of Piedmont was not “trying to play in the major leagues diplomatic wise.” Wilson did not “almost veg out” at the end of his second term. President Hindenburg did not appoint Hitler in a “senior moment.” Prime Minister Chamberlain did not tell the Czechs to “chill out” after the Munich Conference, and Gandhi was not an “awesome dude.”

Try to keep your prose fresh. Avoid cliches. When you proofread, watch out for sentences like these: “Voltaire always gave 110 percent and thought outside the box. His bottom line was that as people went forward into the future, they would, at the end of the day, step up to the plate and realize that the Jesuits were conniving perverts.” Ugh. Rewrite as “Voltaire tried to persuade people that the Jesuits were cony, step up to the plate and realize that the Jesuits were conniving perverts.” Ugh. Rewrite as “Voltaire tried to persuade people that the Jesuits were conniving perverts.”

Intensifier abuse/exaggeration.

Avoid inflating your prose with unsustainable claims of size, importance, uniqueness, certainty, or intensity. Such claims mark you as an inexperienced writer trying to impress the reader. Your statement is probably not certain ; your subject probably not unique , the biggest, the best, or the most important. Also, the adverb very will rarely strengthen your sentence. Strike it. (“President Truman was very determined to stop the spread of communism in Greece.”) Rewrite as “President Truman resolved to stop the spread of communism in Greece.”

Mixed image.

Once you have chosen an image, you must stay with language compatible with that image. In the following example, note that the chain, the boiling, and the igniting are all incompatible with the image of the cold, rolling, enlarging snowball: “A snowballing chain of events boiled over, igniting the powder keg of war in 1914.” Well chosen images can enliven your prose, but if you catch yourself mixing images a lot, you're probably trying to write beyond your ability. Pull back. Be more literal.

Clumsy transition.