- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

OrganizationalCulture →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

- Employee Success Platform Improve engagement, inspire performance, and build a magnetic culture.

- Engagement Survey

- Lifecycle Surveys

- Pulse Surveys

- Action Planning

- Recognition

- Talent Reviews

- Succession Planning

- Expert-Informed AI

- Seamless Integrations

- Award-Winning Service

- Robust Analytics

- Scale Employee Success with AI

- Drive Employee Retention

- Identify and Develop Top Talent

- Build High Performing Teams

- Increase Strategic Alignment

- Manage Remote Teams

- Improve Employee Engagement

- Customer Success Stories

- Customer Experience

- Customer Advisory Board

- Not Another Employee Engagement Trends Report

- Everyone Owns Employee Success

- Employee Success ROI Calculator

- Employee Retention Quiz

- Ebooks & Templates

- Leadership Team

- Partnerships

- Best Places to Work

- Request a Demo

The Importance of Organizational Culture

Research & advice for building a more magnetic culture.

65% of employees say their company culture has changed post-pandemic. Our research shows that employee perceptions of company culture have a direct impact on engagement and retention. This information can help leaders rethink their approach to culture and create a foundation for business success.

2022 Organizational Culture Research Report

Table of contents.

What is organizational culture

The top elements of organizational culture

What employees think about organizational culture

How culture impacts employee engagement & retention risk

Where organizational culture thrives

What employees want in an organizational culture

Who shapes organizational culture

5 tips for creating a strong, engaging culture

Make culture easier with quantum workplace.

![research topics on organizational culture Why is Organizational Culture Important? [Original Research & Tips]](https://www.quantumworkplace.com/hubfs/Culture%20Report%20-%20HRE%20Ad%20LP%20-%20052022%20%28400%20%C3%97%20400%20px%29%20%281200%20%C3%97%201000%20px%29.png)

Unpacking organizational culture

Company culture has become a top priority for leaders across all industries. In fact, 66% of executives believe culture is more important than an organization's business strategy or operation model.

The rise of remote and hybrid work has had a significant impact on the way we work. Our research shows 65% of employees say their company culture has changed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. As the workplace has changed, culture has too—for better or for worse.

Those organizations that have adapted their approach to culture have fared well over the past few years. They've created an attractive value proposition for prospective talent and have kept current employees engaged—even through periods of significant change. Those who have been slower to evolve have seen consequences of disengagement, burnout, and unwanted turnover.

Our research shows disengaged employees are 3.8 times more likely than their engaged counterparts to cite organizational culture as a reason for leaving.

While most leaders agree a strong culture is key to business success, many have different ideas about what culture really is. This lack of clarity makes it difficult to make changes that move the needle. Leaders need to take a good look at the role culture plays in attracting, retaining, engaging, and empowering talent. They need to focus on the aspects of culture that drive employee, team, and business success.

Our organizational culture research offers a fresh perspective on workplace culture. It helps make clear the most critical aspects of creating an engaging and successful culture. It shows the link between culture, employee engagement, and retention. And it will help organizational leaders rethink their approach to culture in order to shape a foundation for business success.

What is organizational culture?

Culture has been historically defined as organizational norms, rituals, and values. But organizational culture is so much more than that. It’s about the day-to-day attitudes, actions, and behaviors at an organization. Essentially, it’s how work gets done within a business, including:

- The way you make decisions

- The way you communicate

- The way you celebrate employees

- The way you behave

- The way you reward and recognize others

Employees experience culture through many aspects of your organization. But our research shows that some aspects are felt much more powerfully than others. Culture is really about the day-to-day details of how work gets done. Here are the top ways that employees feel the culture at their organization.

50% of employees experience culture most strongly in their organization's approach to employee performance.

The way you manage performance has a strong impact on engagement and organizational culture. How managers create alignment, communicate, recognize, and give feedback all shape an employee’s experience. Focus on performance management approaches that drive employee success and wellbeing. Read our research on creating an engaging performance management approach here >>

53% of employees feel culture most strongly through recognition and celebrations.

Employees want to feel valued for their contributions. How you recognize individuals and teams says a lot about your culture and what you value. When you publicly recognize employees for behaviors that align with your culture and values, it helps bring culture to life.

54% of employees experience culture most strongly through their organization's mission and values.

Your mission and values set the tone for how work gets done. If your mission is to help others, your culture might be more collaborative. If innovation is a core value, put systems in place that encourage innovation. To create a strong culture, leverage your mission and values to guide everyday initiatives.

What employees think about organizational culture

Company culture is changing across all industries. Our research shows that while some employees believe this change is positive, others think differently. As culture continues to evolve, it impacts the employee experience in different ways than before.

65% of employees say their company's culture has changed post-pandemic.

35% say their culture has changed dramatically. As the workplace has changed, culture has changed too—for better or worse. Whether or not you’re actively investing in your culture, someone or something is shaping it. Leaders must keep a pulse on culture to ensure they’re driving the right changes at the right times.

2 in 3 employees say their organizational culture is "very positive."

66% of employees say their culture positively impacts their work and behavior everyday.

Culture is a day by day, moment by moment experience. It’s key to create a culture that promotes the right outcomes and behaviors. Listen to what your employees have to say about the day to day happenings inside your organization—and make adjustments that improve their experience.

Culture—or “how work gets done”—is going to look different in your unique workplace. The way you communicate, treat each other, and make decisions can either positively impact engagement and retention, negatively impact it, or not impact it at all.

Employees who say their culture is positive are 3.8x more likely to be engaged.

A positive culture strengthens employee engagement. When employees agree that their organizational cultures are positive, they are more likely to be highly engaged, (84%) than those who do not agree (22%).

Employees who say their culture has improved since the pandemic are 2.9x more likely to be highly engaged.

When employees say their culture has improved over the past two years, they are more likely to be highly engaged (81%) than employees who say it has declined (28%). This illustrates the link between culture and engagement. A strong culture drives employee engagement, whereas a weak culture can boost disengagement.

Disengaged employees are 2.6x more likely to leave their company for a better culture.

Roughly 60% of disengaged employees—and only 23% of engaged employees—would leave their company for a better culture. This suggests that employee engagement is the motivating factor behind retention. One of the ways to drive engagement? A positive workplace culture.

Where organizational culture thrives

Remote and hybrid work environments are becoming the norm. While many leaders believe that culture suffers outside of the physical workplace, our research provides a different perspective. Those offered flexibility in the workplace are likely to see culture more favorably.

Remote/hybrid employees are more likely to report a strong and positive company culture.

Only 65% of on-site employees believe their company has a strong culture, compared to over 70% of remote and hybrid workers. Only 58% of onsite employees say their culture is positive, compared to roughly 70% of remote and hybrid employees. Company culture isn’t attached to the physical workplace. In fact, it can be strengthened in a remote/hybrid environment. Giving employees the option to choose where they work fosters a culture of mutual trust and respect.

Remote/hybrid employees are more likely to say their culture has improved.

While remote (45%) and hybrid (44%) say their cultures have improved, only 37% of on-site employees say the same. Flexible work arrangements promote employee wellbeing, autonomy, work-life balance, inclusion and productivity.

Workplace employees are most likely to say their culture has declined.

28% of on-site workers say their culture has declined since the start of the pandemic. Now more than ever, employees expect flexibility, autonomy, and trust. When you can’t give your employees the option to work from home, try to find other ways for them to decide how their work gets done.

A Note on Industry Impact There are some industries and roles that are inherently less conducive to remote/hybrid work arrangements. Therefore, we explored whether other factors, like industry or company size, influence employees' perceptions of culture. While industry and company size can impact these perceptions, we found that where and how employees work has a stronger influence on their perceptions of culture. Regardless of the type of work you do, employees want a culture of flexibility and trust. That's why culture doesn't fizzle out in flexible or non-traditional work environments.

Engaged and disengaged employees describe their cultures in different ways. But both engaged and disengaged employees know what they want—and don’t want—when it comes to culture.

No surprises here. Engaging cultures have a better reputation with talent.

It’s no surprise that engaged employees value their culture. After all, culture is a key factor behind engagement. The top words engaged employees use to describe their culture are:

- Inclusive

- Caring

- Collaborative

But disengaged employees have different thoughts. A few words disengaged employees use to describe their culture include:

- Disorganized

- Professional

How employees describe an ideal culture

Regardless of engagement level, employees know what they want when it comes to culture. The top 5 words employees used to describe an ideal culture are:

1. Flexible 2. Inclusive 3. Supportive 4. Collaborative 5. Caring

To engage your employees, give them the flexibility to decide how, when, and where their work gets done. You should also prioritize inclusivity and give everyone the opportunity to succeed regardless of role, tenure or background. Regular check-ins, growth-focused coaching, and collaboration will support employee success further. Finally, ensure you show your people that you care about them as humans—not just employees.

Who shapes organizational culture?

According to our research, employees believe leaders, managers, and HR are responsible for company culture. But to create a great culture, everyone needs to play a part. Culture should grow and evolve in a way that resonates with each employee, regardless of role.

Employees believe that leaders and managers are responsible for culture.

Culture starts at the top. In fact, Leaders should clearly define culture, communicate about it regularly, set a good example, and tie business outcomes to company values. This will empower employees to practice, develop, and evolve cultural norms.

57% of employees believe HR is responsible for creating company culture.

Many employees expect HR to shape company culture. But while HR is probably trying to create culture, they need leadership and employees to support their efforts. Without company-wide adoption, you won’t see the culture change you want.

57% of employees believe individual contributors are responsible for shaping culture.

Each individual plays a part in culture. To create a strong culture, employees must understand and live out their culture, mission, and values. They must collaborate, recognize, communicate, and behave in a way that aligns with cultural norms.

Everyone plays a part in culture. The healthiest cultures are shaped by every person within an organization. And the job of creating culture is never done. As your organization changes, it’s important to be intentional about how those changes impact culture.

A healthy culture looks different for everyone. Leaders should keep their unique business problems and opportunities in mind when creating a culture strategy. Shape your approach with these tips to foster a culture of engagement, performance, and long-term success.

1. Aim your culture strategies at engagement.

A healthy culture drives employee engagement first and foremost. When you evaluate “how work gets done” at your organization, try to understand how each aspect could impact employee engagement. Engagement is all about connecting employees to their work, team, and organization—ensure your culture strategies do the same.

2. Evolve your approach to employee performance.

Employees say performance management is a key component of culture. With the right practices, you can drive alignment, motivation, growth, and engagement. With the wrong approach, you risk toxicity, distrust, and burnout. Use performance management as a tool to strengthen culture with continuous feedback, effective communication, company-wide alignment, and fairness and transparency.

3. Focus on driving trust-building leadership practices.

To create a culture of trust , clearly outline your organization’s vision, strategy, progress, and goals. Leaders should communicate frequently and transparently to prevent employee confusion or resentment when change happens. Continue this communication when you gather employee feedback too, explaining how feedback was used—or why it wasn’t. Finally, allow employees to see leaders as real people—genuine relationships are needed to foster genuine trust.

4. Weave employee recognition into all that you do.

Recognition happens in the way you communicate, promote, compensate, assign work, and provide opportunities. Build a system that recognizes behaviors critical to your organizational culture. You should prioritize authenticity when you recognize employees and tailor your communication to each individual. Employee recognition should happen every day—a simple thank you goes a long way.

5. Invest in tech that helps you see, understand, and act on culture.

A robust employee engagement, performance, and people analytics platform will outline the big picture behind your culture and help you understand where to focus and when. With the right tools, you can uncover deep insights, measure employee perceptions, and create a thriving culture.

Every employee in the company builds culture. That's why it's crucial for every aspect of your business to intentionally reflect the culture you want your organization to have.

Employee success tools and technology make it easy for your employees to contribute positively to your culture in their day-to-day tasks, goals, communication, and celebrations.

We make it easy to grow, develop, and retain your best talent.

Lack of career growth and development is one of the primary reasons employees leave their organization. Employees don’t want to feel stagnant. If they do, the result is a lack of engagement and impact. It is crucial to leverage tools that help managers and employees map and track development together.

We make it easy to connect and celebrate meaningfully.

Your culture comes to life through the ways you celebrate and recognize your employees. Building a culture of connection and appreciation centered around your organization’s core values not only boosts employee morale, but also engagement and impact.

We make it easy to predict and prevent turnover.

You need to take a targeted approach to analyzing turnover and retention. To move from reacting to turnover to proactively addressing it, you have to understand what drives top talent to leave and continuously implement strategies to retain your best employees.

We make it easy to stand out and compete for talent.

Employees are your most vital asset. You need to have a dynamic strategy in place to stand out against your competitors and attract top talent. Benchmarking can help you understand the strengths and opportunities of your employee value proposition compared to your competitors. Transform your EVP into one that cannot be imitated.

Survey Methodology

The research from this report was derived from the Best Places to Work contest—powered by Quantum Workplace. This nationwide contest measures the employee experience of over 1 million voices across thousands of the most successful organizations in the United States.

From this respondent pool, we conduct an opt-in, independent research panel with over 32,000 individuals who share their workplace experiences. This unique vantage point gives us the ability to understand workplace trends to supply insights that help other organizations succeed.

Learn how to build a magnetic culture by making culture easier for you and your teams!

Published August 22, 2023 | Written By Kristin Ryba

Related Content

14 One on One Meeting Topics You Should Be Discussing With Employees

Quick links.

- Performance

- Intelligence

Subscribe to Our Blog

View more resources on Company Culture

![research topics on organizational culture The Ultimate Guide to Company Culture [2022 Edition]](https://www.quantumworkplace.com/hubfs/workplace-culture.png)

The Ultimate Guide to Company Culture [2022 Edition]

10 minute read

15 Diversity and Inclusion Best Practices for Bridging the D&I Gap

6 minute read

![research topics on organizational culture Culture Change in the Workplace [Infographic]](https://www.quantumworkplace.com/hubfs/Marketing/Website/Blog/Feature-Images/FEATURE%20IMAGE%20Culture%20Infographic%20400%20x%20350.png)

Culture Change in the Workplace [Infographic]

Less than 1 minute read

- All Resources

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Terms of Service

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The Leader’s Guide to Corporate Culture

- Boris Groysberg,

- Jeremiah Lee,

- Jesse Price,

- J. Yo-Jud Cheng

Executives are often confounded by culture, because much of it is anchored in unspoken behaviors, mindsets, and social patterns. Many leaders either let it go unmanaged or relegate it to HR, where it becomes a secondary concern for the business. This is a mistake, because properly managed, culture can help them achieve change and build organizations that will thrive in even the most trying times.

The authors have reviewed the literature on culture and distilled eight distinct culture styles: caring, focused on relationships and mutual trust; purpose, exemplified by idealism and altruism; learning, characterized by exploration, expansiveness, and creativity; enjoyment, expressed through fun and excitement; results, characterized by achievement and winning; authority, defined by strength, decisiveness, and boldness; safety, defined by planning, caution, and preparedness; and order, focused on respect, structure, and shared norms.

These eight styles fit into an “integrated culture framework” according to the degree to which they reflect independence or interdependence (people interactions) and flexibility or stability (response to change). They can be used to diagnose and describe highly complex and diverse behavioral patterns in a culture and to model how likely an individual leader is to align with and shape that culture.

Through research and practical experience, the authors have arrived at five insights regarding culture’s effect on companies’ success: (1) When aligned with strategy and leadership, a strong culture drives positive organizational outcomes. (2) Selecting or developing leaders for the future requires a forward-looking strategy and culture. (3) In a merger, designing a new culture on the basis of complementary strengths can speed up integration and create more value over time. (4) In a dynamic, uncertain environment, in which organizations must be more agile, learning gains importance. (5) A strong culture can be a significant liability when it is misaligned with strategy.

How to manage the eight critical elements of organizational life

Strategy and culture are among the primary levers at top leaders’ disposal in their never-ending quest to maintain organizational viability and effectiveness. Strategy offers a formal logic for the company’s goals and orients people around them. Culture expresses goals through values and beliefs and guides activity through shared assumptions and group norms.

A survey to get the conversation started

- BG Boris Groysberg is a professor of business administration in the Organizational Behavior unit at Harvard Business School and a faculty affiliate at the school’s Race, Gender & Equity Initiative. He is the coauthor, with Colleen Ammerman, of Glass Half-Broken: Shattering the Barriers That Still Hold Women Back at Work (Harvard Business Review Press, 2021). bgroysberg

- JL Jeremiah Lee leads innovation for advisory services at Spencer Stuart. He and Jesse Price are cofounders of two culture-related businesses.

- JP Jesse Price is a leader in organizational culture services at Spencer Stuart. He and Jeremiah Lee are cofounders of two culture-related businesses.

- JC J. Yo-Jud Cheng is an Assistant Professor of Business Administration in the Strategy, Ethics and Entrepreneurship area at Darden.

Partner Center

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Categorical thinking can lead to investing errors

How storytelling helps data-driven teams succeed

Financial services’ deliberate approach to AI

Credit: zhikun sun / iStock

Ideas Made to Matter

Organizational Culture

MIT Sloan research on organizational culture

Kara Baskin

Jul 25, 2022

COVID-19 has upended traditional working arrangements: Remote and hybrid work have expanded geographic possibilities, while abbreviated work weeks and flex time have changed the parameters of the traditional workday and workers’ expectations.

In this new era, leaders at every level of the enterprise are struggling to articulate an organizational culture that’s right for this new moment.

Here’s what MIT Sloan experts and researchers think are the key steps to building an organizational culture that works now and into the future.

Embrace distributed leadership

Smart organizations are shifting from command-and-control leadership to distributed leadership, which MIT Sloan professor Deborah Ancona defines as collaborative, autonomous practices managed by a network of formal and informal leaders across an organization.

The practice gives people autonomy to innovate and uses noncoercive means to align them around a common goal, a structure that’s highly appealing to employees who are used to being autonomous and empowered.

“Top leaders are flipping the hierarchy upside down,” said MIT Sloan lecturer Kate Isaacs, who collaborates with Ancona on research about teams and nimble leadership.

“Their job isn't to be the smartest people in the room who have all the answers,” Isaacs said, “but rather to architect the gameboard where as many people as possible have permission to contribute the best of their expertise, their knowledge, their skills, and their ideas.”

Nurture a digital workforce …

To transform a traditional workforce into one that is future-ready, leaders should equip workers with the technologies they need and give them the accountability and capabilities to fully exploit those tools, according to Kristine Dery, an academic research fellow with the MIT Center for Information Systems Research .

Companies should aim to make their employees empowered problem solvers, Dery said, by creating a supportive environment of continual and rapid learning where they can leverage technologies to solve unpredictable problems. These employees need to have confidence to solve problems, and the skills to work effectively in a digital world.

This isn’t just a nice idea in theory: Companies that invest in the right experience for their people, and make sure they are ready for the future, tend to outperform their competitors. On average they deliver 19% more growth in revenue than their competitors and have 15% more profit. These companies are also more innovative, better at cross-selling, and deliver a significantly better customer experience, Dery said.

… but don’t ignore employee hierarchies

The ascension of junior employees needs to be handled with care. In a tech-first world, younger workers often possess more savvy than older colleagues — but quickly promoting them could create friction with senior co-workers, noted MIT Sloan work and organization studies professor Kate Kellogg. She recommends creating peer-training programs that rotate both senior and junior employees through the role of trainer.

Strive for managers who understand nimble leadership

Nimble organizations are filled with people who feel free to step forward, propose new ideas, and translate them into action. Isaacs, Ancona, and co-researcher Elaine Backman have identified three types of leaders in a nimble organization:

- Entrepreneurial — lower- to mid-level idea generators who inspire trust through technical expertise and reputational credibility.

- Enabling — often middle managers who are good connectors and communicators and who remove obstacles for entrepreneurial leaders.

- Architecting — often high-level leaders who shape culture, structure, and values.

“In a lot of companies ‘purpose’ becomes a motto on the wall, it's not really lived, it’s just lip service,” Isaacs said during an MIT Sloan Executive Education webinar on nimble leadership . “In nimble organizations, [managers] are good at bringing the purpose down off the wall and into daily decision making.”

Turn to middle managers to help promote DEI

Nearly all companies have increased their efforts around diversity, equity, and inclusion. Research from Stephanie Creary , an assistant professor at The Wharton School, shows middle managers will be especially important when promoting diversity and inclusion within a workforce.

Speaking last year at the MIT Sloan Management Review Work/22 event, Creary explained that executives and senior managers are often motivated by market position and competition, but middle managers are typically focused on their team and its performance, making them ideal champions of DEI efforts.

Build a culture that supports remote teams

In their book “ Remote, Inc. ,” MIT Sloan senior lecturer Robert Pozen and co-author Alexandra Samuel, offer ways for managers to effectively communicate with and encourage productivity in their remote employees.

The authors recommend four tools: ground rules, team meetings, one-on-ones, and performance reviews.

“Even experienced managers face new challenges when they first start managing an all or partially remote team,” the authors write. “You need to ensure your team gets its work done, but you also need to put some extra thought and TLC into managing the issues that crop up for remote workers, like personal isolation and trouble communicating with colleagues.”

Strengthen the link between worker well-being and company goals

Research by MIT Sloan professor Erin Kelly, co-author of “ Overload: How Good Jobs Went Bad and What We Can Do about It ,” finds that happier employees are more likely to be engaged, enthusiastic about work, and likely to stay at their jobs.

To promote employee satisfaction, companies should consider pursuing a dual-agenda work redesign — that is, an action plan that links employees’ well-being and experience with a company’s priorities and goals.

A dual-agenda design prompts employees and managers to look at how work can be changed in ways that benefit employees and their families, and also the organization.

“Work redesign is not a change in company policy, it is an effort to construct a new normal, to reconsider and revamp how a team does its work,” Kelly said. “Dual agenda refers to the fact that these changes address both organizational concerns (working effectively) and employee concerns (working in ways that are more sustainable and reflect their personal and family priorities and protect their health).”

Related Articles

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

Organizational Culture

Organizational culture Organizational culture is embedded in the everyday working lives of all cultural members. Manifestations of cultures in organizations include formal practices (such as pay levels, structure of the HIERARCHY,JOB DESCRIPTIONS, and other written policies); informal practices (such as behavioral norms); the organizational stories employees tell to explain “how things are done around here;” RITUALS (such as Christmas parties and retirement dinners); humor (jokes about work and fellow employees); jargon (the special language of organizational initiates); and physical arrangements (including interior decor, dress norms, and architecture). Cultural manifestations also include values, sometimes referred to more abstractly as content themes. It is essential to distinguish values/content themes that are espoused by employees from values/content themes that are seen to be enacted in behavior. All of these cultural manifestations are interpreted, evaluated, and enacted in varying ways because cultural members have differing interests, experiences, responsibilities and values.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Organizational Culture and Climate: New Perspectives and Challenges

Loading... Editorial 15 September 2023 Editorial: Organizational culture and climate: new perspectives and challenges Thais González-Torres , Vera Gelashvili , Juan Gabriel Martínez-Navalón and Giovanni Herrera-Enríquez 2,926 views 0 citations

Systematic Review 13 July 2023 Dynamics of organizational climate and job satisfaction in healthcare service practice and research: a protocol for a systematic review Silvina Santana and Cristina Pérez-Rico 2,425 views 1 citations

Original Research 05 June 2023 Organizational health climate as a precondition for health-oriented leadership: expanding the link between leadership and employee well-being Friederike Teetzen , 2 more and Sabine Gregersen 3,149 views 1 citations

Original Research 25 April 2023 Gender and organizational culture in the European Union: situation and prospects Nuria Alonso Gallo and Irene Gutiérrez López 2,501 views 2 citations

Original Research 09 March 2023 Factors that favor or hinder the acquisition of a digital culture in large organizations in Chile Carolina Busco , 1 more and Michelle Aránguiz 2,946 views 2 citations

Original Research 10 February 2023 Implementation model of data analytics as a tool for improving internal audit processes Rubén Álvarez-Foronda , 1 more and José-Luis Rodríguez-Sánchez 3,085 views 1 citations

Original Research 17 January 2023 The Impact of Team Learning Climate on Innovation Performance – Mediating role of knowledge integration capability Ming-Shun Li , 3 more and Xin-Tao Deng 1,999 views 1 citations

Loading... Original Research 11 January 2023 The relation between Self-Esteem and Productivity: An analysis in higher education institutions Fabiola Gómez-Jorge and Eloísa Díaz-Garrido 6,138 views 2 citations

Original Research 23 December 2022 Validating the evaluation capacity scale among practitioners in non-governmental organizations Steven Sek-yum Ngai , 6 more and Elly Nga-hin Yu 1,362 views 1 citations

Loading... Original Research 02 December 2022 Digitalization and digital transformation in higher education: A bibliometric analysis Vicente Díaz-García , 2 more and Rocío Gallego-Losada 8,706 views 9 citations

Loading... Original Research 21 October 2022 A multi-level study on whether ethical climate influences the affective well-being of millennial employees Wei Su and Juhee Hahn 3,054 views 6 citations

Review Frontiers in Psychology Solvency and Profitability: The duality of the large Spanish banks between the two economic-financial crises of the 21st century 1,806 views 0 citations

Conceptualizing organizational culture and business-IT alignment: a systematic literature review

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 08 August 2022

- Volume 2 , article number 120 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Marcel R. Sieber ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2282-6164 1 ,

- Milan Malý ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5812-918X 2 &

- Radek Liška ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4639-7026 2

3024 Accesses

Explore all metrics

For decades, business and information technology alignment has fascinated scholars and practitioners. However, understanding these alignment mechanisms is challenging. The significant role of information technology (IT) in digitalization and agile transformation calls for targeted management of the readiness and capability of IT as an enabler and strategic business partner. This paper assumes that organizational culture is a success factor for business-IT alignment. Therefore, it aims to explore the culture-alignment relationship by the following research questions: What are typical IT management organizational culture characteristics, and how do they contribute to business-IT alignment? The study conducts a systematic literature review. First, after defining the critical terms, it searches the databases indexed in the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Then, the study uses bibliometrics to get quantitative insights into the research topic. Finally, it investigates the key arguments and findings of the selected papers. The analyzed literature depicts the relationship between an IT management culture and business-IT alignment elements. However, the research lacks concrete modeling and conception. This article contributes to a better culture-alignment relationship interpretation and closes a gap in the body of knowledge by combining quantitative and qualitative literature review methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Digital transformation: a review, synthesis and opportunities for future research

Reactions towards organizational change: a systematic literature review

Competitiveness Through Development of Strategic Talent Management and Agile Management Ecosystems

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The growing economic importance of information technology (IT) leads to an increased significance of the alignment of business and IT (Chan and Reich 2007 , p. 298; Hiekkanen et al. 2015 ; Jonathan 2018 ; Kappelman et al. 2013 ; Luftman and Brier 1999 ). Especially when industries and businesses encounter agile and digital transformation challenges, IT departments and their alignment to the business play a crucial role (Gajardo and Ariel 2019 ). Furthermore, IT supports the business in realizing digitalization opportunities as a provider of dedicated digital infrastructure, products, services, and solutions (Kahre et al. 2017 ).

Although regularly on top of the practitioners’ and scientists’ agendas, business-IT alignment remains challenging (Jonathan and Hailemariam 2020 ; Luftman et al. 2013 , p. 357). Business and IT need a mutual understanding , strategically aligned as one, founded on IT governance (Chew and Gottschalk 2013 , pp. 186–190). As part of corporate governance, IT governance ensures that IT supports and enlarges the organizations’ strategies and objectives, including the alignment of IT to realize business gains (IT Governance Institute 2003 , pp. 10–11). It also helps prioritize and allocate the needed resources (Luftman and Brier 1999 , p. 119). However, traditionally, IT primarily remains in a strategically executive role, functional and essentially subordinate to the business (Hiekkanen et al. 2012 , Kahre et al. 2017 , p. 4706). This perspective roots in the senior executives’ perceptions of IT as a cost factor in a historical context because it has not achieved the expected competitive advantage in the 1980s and 1990s (Chew and Gottschalk 2013 , p. 327; Peppard and Ward 1999 , p. 32). Practitioners regularly report shortcomings of IT realizations in time, cost, and quality; this is mainly an issue of the critical relationship between cost-efficiency and effectiveness, including the role of IT strategy and culture (Aitken 2003 ). Critics about a hindering IT culture because of its stability and security tendencies call for entrepreneurial, or at least commercial behaviors in IT functions, welcoming change and risks (Aitken 2003 ).

Many organizations still struggle with the cultural separation of IT and business , which results in a “us” vs. “them” and a lack of synchronized governance of decisions and strategies (Chew and Gottschalk 2013 , p. 186; Mithas and McFarlan 2017 , p. 6). As a result, the relationship between business and IT remains potentially conflictual (Leidner and Kayworth 2006 ). Besides the biased attitude towards IT, such conflicts concern the user groups of information systems and their often contradictory vision (Leidner and Kayworth 2006 , pp. 374–375). Although they found only a few studies about the managerial’s role, Leidner and Kayworth ( 2006 , p. 380) proposed that managers could reduce conflicts by shaping and promoting shared values in business and IT. Such values would be part of a shared organizational culture, fostering the relationship between business and IT. However, the business-IT partnership also depends on the IT department’s business orientation, managerial knowledge, and perceived IT value. Accordingly, although to a relatively small magnitude, a significantly technology-oriented IT negatively impacts the relationship between business and IT (Manfreda and Indihar Štemberger 2019 , p. 962). These findings are consistent with the research of 20 years ago, where the examined organizations’ IT management acknowledged that they need to increase their business knowledge (Peppard and Ward 1999 , p. 50).

Before this background, this paper aims to explore the influence of organizational culture on business-IT alignment, i.e., if particular organizational culture dimensions help IT management leaders or teams suitably align to the business. It investigates the following research questions:

What are the information technology management’s typical organizational culture characteristics?

How do these characteristics contribute to the alignment of business and information technology?

Therefore, it employs a systematic literature review and follows a hybrid approach by integrating a bibliometric and structured review (Paul and Criado 2020 , p. 2). As a result, the study presents a comprehensive and extended overview of the knowledge base about the relationship between organizational culture and business-IT alignment. Furthermore, it discusses the implications of research strategies, bibliometric analyses, and qualitative aspects of the literature review in this paper.

The remainder of the paper starts with the theoretical background and then explains the methodology, including the search procedure and strategy, bibliometrics, and paper selection. Then follow the results with quantitative and qualitative analyses of the references, which reflect the relevance and relation of the critical research topics and the studies relating to this paper’s research questions. After the discussion of the results with summarizing them before the theoretical background, the paper finally closes in the conclusions by considering this paper’s contributions and limitations and answering the research questions.

Theoretical background

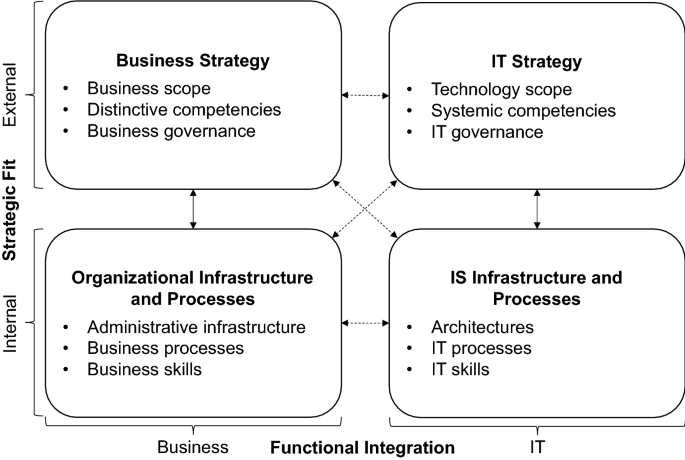

The concept of alignment is only vaguely defined (Hiekkanen et al. 2012 , p. 219). This study takes a decent strategic management point of view. From this perspective, the common goal to deliver the best value and service to the information system’s user denotes the relationship between business and IT strategy (Buchta et al. 2010 ). Different models and frameworks for business-IT alignment exist in the literature (El-Mekawy 2016 ). The strategic alignment model (SAM) of Henderson and Venkatraman ( 1993 ) and the strategic alignment maturity model (SAMM), published by Luftman ( 2000 ), are probably the most cited and widely used works. This paper relies on Henderson and Venkatraman’s ( 1993 , p. 472) model and its definition of business-IT alignment as “four fundamental domains of strategic choice: business strategy, information technology strategy, organizational infrastructure and processes, and information technology infrastructure and processes,” see Fig. 1 . Along with these traits, business and IT align in a mutual “process of continuous adaptation and change” (Henderson and Venkatraman 1993 , p. 473).

Strategic alignment model (adapted from Henderson and Venkatraman 1993 )

The SAMM focuses on maturity levels, measured by six criteria (Luftman 2000 , p. 10): Communications, competency/value, governance, partnership, scope & architecture, and skills. The last criterium contains an organization’s cultural and social environment (Luftman 2000 , p. 20). This overlapping with organizational culture is the most important reason not to include the SAMM in this paper’s analyses.

Organizational culture is multi-faceted, and no widely shared definition exists. Table 1 provides a brief classification of organizational culture perspectives. The first authors emphasize culture as a variable or out of a functional view (Baetge et al. 2007 , p. 186). They argue that an organization has a specific culture that can be managed, measured, and compared. The second group of scholars states that an organization is a culture, with its uniqueness and perceptions of practices (Hofstede et al.), values (Sagiv et al.), and underlying assumptions (Schein). These perspectives are more subjective than the above noted; they are harder to compare. The third theory evolved as a combination of those mentioned above and questions the deterministic, taken-for-granted, and simply assessable view of organizational culture (Alvesson 2013 , pp. 31–32). Alvessonn ( 2013 , p. 65) advises studying the specific cultural manifestations and their consequences rather than the entire corporate culture and its impact on organizational performance.

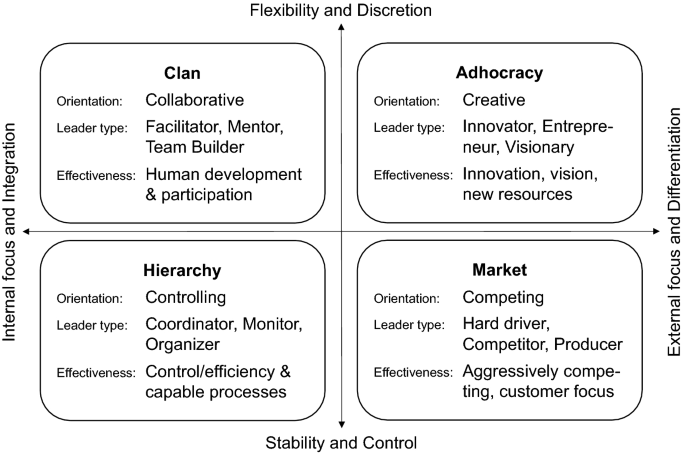

This paper takes a functional perspective and focuses on culture as “the norms and values that guide behavior within organizations” (Chatman and O’Reilly 2016 , p. 218). Culture is responsible for adapting organizations to their societal and economic environment, and it integrates structures and processes for the alignment of conjoint activities (Herget and Strobl 2018 , p. 6). That functional view also holds Cameron and Quinn’s ( 2011 , p. 168) Competing Values Framework (CVF). It emphasizes culture as a variable that can be managed and measured at the corporate level. This paper defines organizational culture before the background of the CVF as “a potential predictor of other organizational outcomes (such as effectiveness),” which “includes core values and consensual interpretations about how things are” (Cameron and Quinn 2011 , p. 169).

Figure 2 depicts the framework with its four quadrants and characteristics. It spans two dimensions: the y-axis contrasts effectiveness between flexibility/freedom to act and stability vs. control , the x-axis internal focus and integration , and external focus and differentiation . The dimensions’ properties result in the four ideal-typical quadrants Clan , Adhocracy , Market , and Hierarchy .

Competing values framework (adapted from Cameron and Quinn ( 2011 , p.53))

Prior research shows an influence of business-IT alignment on various outcomes, such as competitive advantage (Kearns and Lederer 2003 ), business/organizational performance (Chan and Reich 2007 , p. 298; Charoensuk et al. 2014 ; Hiekkanen et al. 2012 ; Kahre et al. 2017 , p. 4707), process performance (Cleven 2011 ); organizational agility (Koçu 2018 ; Lemrabet et al. 2011 ), organizational change (Wattel 2012 ), and information security (El Mekawy et al. 2014 ).

However, there is a shortcoming of studies about the relationship between organizational culture and business-IT alignment (El-Mekawy et al. 2016 ); culture is just one among other factors of business-IT alignment (Hiekkanen et al. 2012 , p. 221). We know a lot about organizational culture and effectiveness (Denison and Mishra 1995 ; Hartnell et al. 2011 ; Quinn and Rohrbaugh 1983 ; Wallach 1983 ), performance (Dasgupta 2014 ; Deshpandé and Farley 2004 ; Henri 2006 ; Heskett 2012 ; Kotter and Heskett 1992 ; Wilkins and Ouchi 1983 ), and (organizational) agility (Felipe et al. 2017 ; Iivari and Iivari 2011 ; Ravichandran 2018 ; Sambamurthy et al. 2003 ; Tallon et al. 2019 ) but not in direct relation to business-IT alignment.

Methodology

This study conducted a systematic literature review. As a guideline and intention to structure the review procedure, the paper applied the Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al. 2009 ; Jackson et al. 2015 , p. 41). That framework helps scholars improve the review’s reporting and consists of a checklist with different items, which reflect the iterative process of reviews, and a proposed flow diagram for screening and selecting the literature (Moher et al. 2009 , pp. 5–6; 8).

The paper followed a hybrid approach, as described in (Paul and Criado 2020 , p. 2). After a domain-based systematic literature search, it conducted a bibliometric analysis with the found references and selected the full-text articles and conference papers. Finally, the analysis structured and discussed the selected studies’ contributions to the body of knowledge.

Search procedure

Table 2 summarizes the approach for getting the relevant search terms. The main aspects in column one reflect the keywords regarding the research questions. For example, the terms IT , short for information technology , and different business and IT alignment writings, such as business-IT or IT-business alignment – with or without the hyphen–, company alignment , or just alignment , are challenging.

Columns two and three of Table 2 present the binding and related terms, i.e., synonyms, derived from the key terms. Bold terms or parts of the terms indicate possible truncations for the search procedure to find words with different typings, such as organization, organizational, the British organisation, organisational, and the German Organisation, or Organisations-. Emphasized words with an asterisk are terms out of the scope of this literature review. This study followed a strategic and socio-institutional organizational culture and business-IT alignment approach. This institutional perspective excluded psychological concepts such as identity and climate or operational and process concepts such as operations and maturity . Also out of scope were emerging investigations relating to data and data science as special information systems topics.

The research strategy considered databases of the Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science (WoS), Elsevier’s Scopus, and Google Scholar, as, for example, Yang and Meho ( 2007 , p. 12) and Paul and Criado ( 2020 , p. 3) recommend. The search procedure from May 2022 needed appropriate adaptation since these providers use different forms, syntaxes, and filters.

For the Web of Science , this study applied the following steps:

Select the suitable indexes,

Use the search field Topic, which searches the documents’ title , abstracts , author keywords , and Keywords Plus , i.e., the keywords attributed automatically by the indexing database,

Apply truncations, for example, organi?ati* , corpor* , or enterpr* , and connect the terms by the boolean operator OR,

Use the particular operator NEAR/50 with culture, truncated as *ultur* , which enables the finding of, for example, organizational and culture within a distance of 50 words,

Add rows with the boolean AND and the terms of the other main aspects of Table 2 ,

Add rows with the boolean NOT with all terms out of the scope of the research field,

Search and refine the results by the document types articles, conference papers, books, book chapters (if apparent), and Web of Science categories.

For Scopus , the steps were similar:

Search within article title , abstract , and keywords ,

Connect the truncated terms with OR and culture with W/50, similar to the Web of Science operator NEAR/50,

Add main aspect terms with AND,

Exclude terms out of focus with AND NOT ,

Exclude subject areas irrelevant to the research field, such as Arts and Humanities , Environmental Science , Mathematics , or Medicine ,

Limit to document type, i.e., article, conference paper, book chapter, and book,

Exclude most apparent keywords not relevant to the search terms, such as Knowledge Management , Societies and Institutions , Project Management , Marketing , Personnel , or Human Resource Management .

Since Google Scholar is less standardized than Web of Science and Scopus, the search procedure differs. A similar search strategy in Google Scholar would have given too many results. Therefore, we used the exact terms, such as organizational culture or corporate culture and business-IT alignment . The results must be sorted by relevance, and the box named “include citations” unticked. Finally, it tooks a manual effort by ticking the star to include the references with the terms in the title and description in the personal library.

This review protocol aligns with Moher et al. ( 2009 ) checklist items five and eight. Appendix A of the supplementary material summarizes and refers to the checklist’s items in this study, Appendix B depicts the review protocol with further details of the search procedure.

Bibliometric analysis

Bibliometrics helps the researcher quantitatively overview the publications’ citation trends and the state-of-the-art of a research field or topic (Paul and Criado 2020 , p. 2; Aria et al. 2020 , p. 805). By using statistical tools, bibliometric analysis knows mainly two branches. First, the bibliometric performance analysis measures scholars’ publication activity and productivity over time and how often they get cited (Aria et al. 2020 , p. 805). Second, the science mapping analyzes and visualizes a specific domain’s structural and knowledge linkages (Aria et al. 2020 , p. 806). In order to answer the research questions, we focused on the afore-mentioned second purpose of bibliometrics.

For this purpose, we applied the regularly updated R-package bibliometrix , explained and maintained by Aria and Cuccurullo ( 2017 ), who propose a science mapping workflow. For bibliometric analysis, other software tools are available, such as CitNetExplorer (van and Waltman 2014 ), HistCite (HistCite - Research HUB n.d.), Pajek (Mrvar and Batagelj 2016 ), or SciMAT (Cobo et al. 2012 ). However, the evaluation of different tools is out of the scope of this paper. Since we are used to R as a convenient statistical tool, and bibliometrix is fully integrated and reasonable for our purpose, we consequently applied it in this study.

The first step of the science mapping workflow was loading the data and converting it into an R data frame (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 , p. 963). Therefore, the bibliometrix package provides a particular function for Web of Science and Scopus data. Next, the Scopus data frame needed additional fields and a change of sorting for the later merge with the Web of Science data. For Google Scholar, we applied the R-function ReadBib of the RefManageR package (McLean 2014 ). Again, with additional fields, a renaming of columns, and new sorting, we adapted the Google Scholar data to the Web of Science format. Finally, we eliminated duplicate entries by title after combining the three files. The remaining records were the final sample for the bibliometric analysis.

This approach corresponds to the checklist item seven of Moher et al. ( 2009 ).

Paper selection

According to Moher et al. ( 2009 , p. 2), the paper selection’s first step identified the records through database searching. After removing duplicates and filtering by publication date, this study applied the following eligibility criteria:

The sources are open access or available through the lookup engines of this paper’s authors’ affiliation libraries.

In the full-text papers, the key terms notably appear. However, it is insufficient to mention them in the references without citation, and it needs arguing about considering them for further examination.

The key terms are properties in the studies’ research model, methodology, propositions, hypotheses, or findings.

These steps correspond to items six and nine of Moher et al.’s ( 2009 ) checklist.

Quantitative analyses

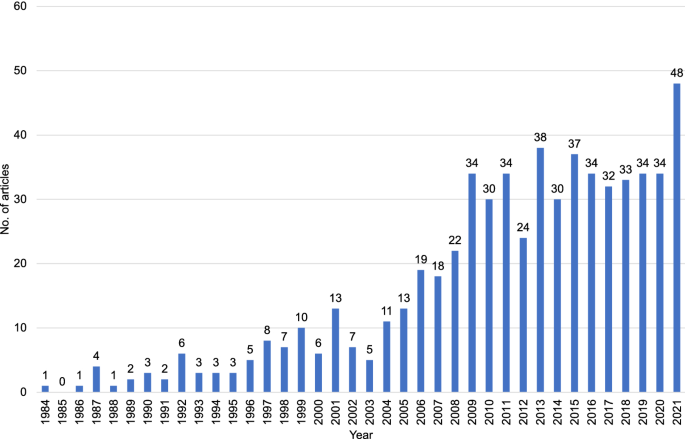

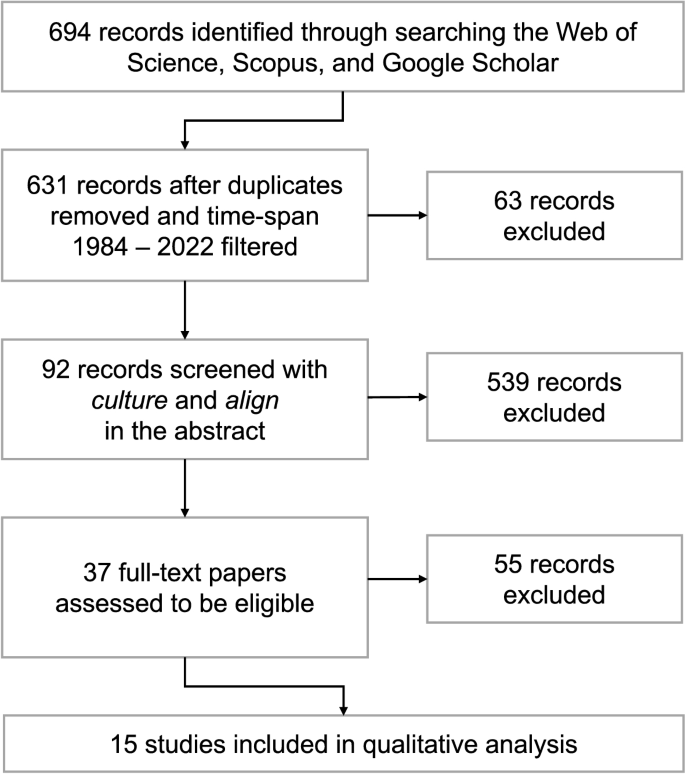

Although the Web of Science quality assurance is the highest reported (Aria et al. 2020 , p. 807), the addition of Scopus and Google Scholar resulted in a more general picture of the body of knowledge (Yang and Meho 2007 , p. 12). The study counted 345 records on the Web of Science, 307 references on Scopus, and 42 entries on Google Scholar. After eliminating duplicates, there remained 660 records. The bibliometrix algorithm filters the records by publication year spanning 1984 to 2022, document type, and average citation per year. As Fig. 6 depicts, the filtering by the period from 1984 to 2022 led to a reduced sample of 631 records.

Table 3 depicts the primary information regarding this collection.

This compilation and the following analyses stem from applying the R tool bibliometrix (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 ). The collection contains 631 documents published in 501 sources. Furthermore, it shows the number of document contents (keywords), authors, authors’ collaboration indexes, and document types.

With an annual growth rate of 7.57%, the annual scientific production of Fig. 3 , i.e., the number of articles published per year, shows a growing trend over the last 20 years.

Annual scientific production

The ten most relevant sources in Table 4 are of considerable validity for the research topic. They consist of high-quality journals, such as Organization Science , Industrial Marketing Management , or Long Range Planning .

Next, we used the words’ analysis section in the documents part of bibliometrix . The options for counting the most frequent words are the fields keywords , titles , or abstracts . We chose abstracts with bigrams , i.e., two-word terms, and the 50 most apparent words. Another important option is to load a list of terms to remove . This list contains regularly used methodological terms, such as empirical research , structural equation , equation modeling , or more general ones, like success factors or future research .

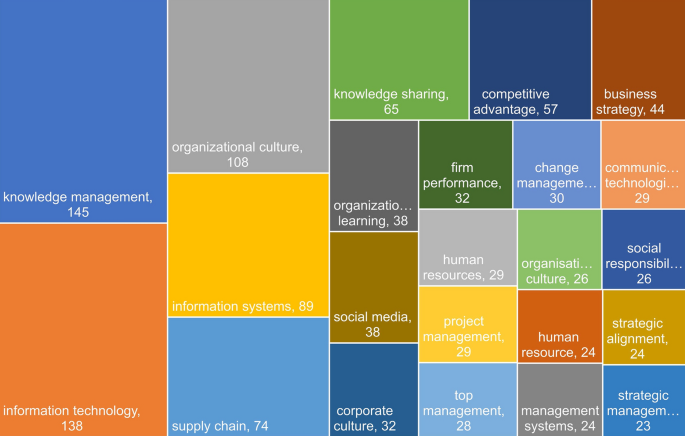

Figure 4 depicts the most frequent bigrams in the paper abstracts with a treemap.

Treemap of the most frequent bigrams in the abstracts

It shows that organizational culture counts 108 and is the third most mentioned after knowledge management with 145 and information technology with 138. However, if we include corporate and organisational , the term organizational culture is with 166 the most mentioned. The terms regarding business-IT alignment are indirect, strategical topics, such as competitive advantage , business strategy , strategic alignment , and strategic management . Added up, they occur 148 times.

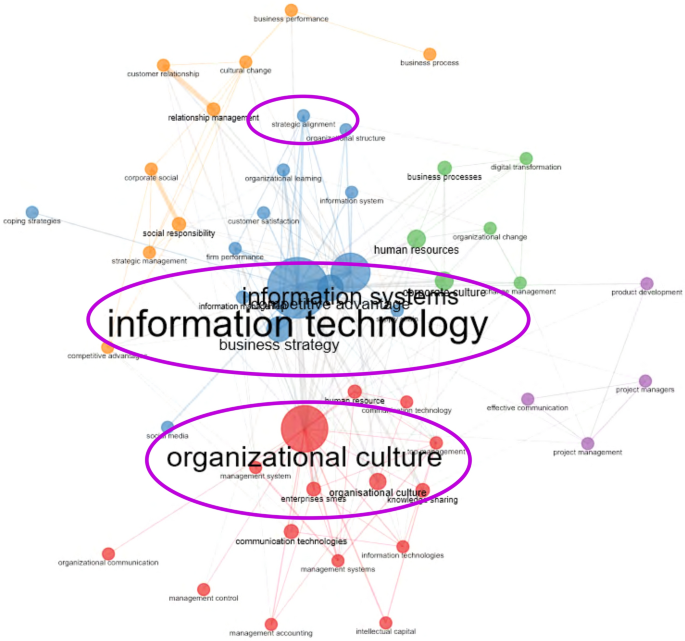

The study can then draw a conceptional framework picture of the research field with a so-called co-occurrence network or co-word analysis (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 , p. 969). This analysis mapped and clustered the data collection terms from the abstracts. Figure 5 depicts that the node of organizational culture has a strong emphasis beside information technology where strategic alignment occurs, although to a lower extent.

Co-occurrence network of the bigrams in the abstracts

Qualitative analysis

As the study reports and depicts in Fig. 6 , the first step of the literature selection was removing duplicates and filtering the search results by the timespan 1984–2022.

Literature selection scheme, adapted from Moher et al. ( 2009 , p. 8)

This step resulted in 631 studies and excluded 63 records. Second, after screening the results with culture / cultural and align / alignment in the abstract, 92 records remained, eliminating 539 entries. Third, from these 92 records, 37 papers were assessed for eligibility by filtering the full texts. The records were deleted if the key terms were not substantially mentioned in the papers and did not appear in the research model, methodology, propositions, hypotheses, or findings. Finally, the fourth step assembled 15 articles and conference papers from these 37 records for further analyses. The selected literature had to contribute to the research questions of this paper.

The relationship between organizational culture and business-IT alignment lacks broad examination (Silvius et al. 2009 ; El-Mekawy et al. 2016 ). There were few literature review studies in the business-IT alignment research field in the reference sample. Moreover, they scarcely investigate organizational or corporate culture properties.

Based on Chan and Reich’s ( 2007 , pp. 300–301) alignment dimensions, Spósito et al. ( 2016 , p. 554) found that less than two-thirds of the papers consider culture. Nevertheless, they do not discuss the papers’ findings and organizational culture properties further. Therefore, the study is not eligible for this analysis. In her thesis, Aasi ( 2016 , pp. 56–57) discusses six papers with an organizational culture influence on the IT governance’s strategic alignment area. Part of them also found entrance in the paper. However, Aasi does not explicitly further examine the relationship, why her thesis is not part of the literature analysis at hand. Also, M. S. A. El-Mekawy ( 2016 , pp. 7–8) only cites a few papers. Finally, Rusu and Jonathan ( 2017 , p. 38) only cite two studies with organizational culture as an influencing factor for the alignment in public organizations. Nevertheless, both papers lack transparent culture or alignment concepts and will not be further analyzed here.

Table 5 shows the compiled studies about the relationships between culture and alignment sorted by type of study, author, and publication year. The collection consists of two literature reviews, one single case study, three multiple case studies, one focus group paper, and nine surveys. This differentiation is notable for the generalization purposes of the studies’ findings.

The table gathers the papers with their organizational culture dimensions, alignment concepts, and critical arguments and findings.