Examining the effects of birth order on personality

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Psychology, University of Leipzig, 04109 Leipzig, Germany;

- 2 Department of Psychology, Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, 55099 Mainz, Germany.

- 3 Department of Psychology, University of Leipzig, 04109 Leipzig, Germany; [email protected].

- PMID: 26483461

- PMCID: PMC4655522

- DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1506451112

This study examined the long-standing question of whether a person's position among siblings has a lasting impact on that person's life course. Empirical research on the relation between birth order and intelligence has convincingly documented that performances on psychometric intelligence tests decline slightly from firstborns to later-borns. By contrast, the search for birth-order effects on personality has not yet resulted in conclusive findings. We used data from three large national panels from the United States (n = 5,240), Great Britain (n = 4,489), and Germany (n = 10,457) to resolve this open research question. This database allowed us to identify even very small effects of birth order on personality with sufficiently high statistical power and to investigate whether effects emerge across different samples. We furthermore used two different analytical strategies by comparing siblings with different birth-order positions (i) within the same family (within-family design) and (ii) between different families (between-family design). In our analyses, we confirmed the expected birth-order effect on intelligence. We also observed a significant decline of a 10th of a SD in self-reported intellect with increasing birth-order position, and this effect persisted after controlling for objectively measured intelligence. Most important, however, we consistently found no birth-order effects on extraversion, emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, or imagination. On the basis of the high statistical power and the consistent results across samples and analytical designs, we must conclude that birth order does not have a lasting effect on broad personality traits outside of the intellectual domain.

Keywords: Big Five; birth order; personality; siblings; within-family analyses.

Publication types

- Comparative Study

- Multicenter Study

- Aged, 80 and over

- Databases, Factual*

- Follow-Up Studies

- Middle Aged

- Parturition*

- Personality*

- Siblings / psychology*

- United Kingdom

- United States

The Reporter

New Evidence on the Impacts of Birth Order

What determines a child's success? We know that family matters — children from higher socioeconomic status families do better in school, get more education, and earn more.

However, even beyond that, there is substantial variation in success across children within families. This has led researchers to study factors that relate to within-family differences in children's outcomes. One that has attracted much interest is the role played by birth order, which varies systematically within families and is exogenously determined.

While economists have been interested in understanding human capital development for many decades, compelling economic research on birth order is more recent and has largely resulted from improved availability of data. Early work on birth order was hindered by the stringent data requirements necessary to convincingly identify the effects of birth order. Most importantly, one needs information on both family size and birth order. As there is only a third-born child in a family with at least three children, comparing third-borns to firstborns across families of different sizes will conflate the birth order effect with a family size effect, so one needs to be able to control for family size. Additionally, it is beneficial to have information on multiple children from the same family so that birth order effects can be estimated from within-family differences in child outcomes; otherwise, birth order effects will be conflated with other effects that vary systematically with birth order, such as cohort effects. Large Scandinavian register datasets that became available to researchers beginning in the late 1990s have enabled birth order research, as they contain population data on both family structure and a variety of child outcomes. Here, I describe my research with a number of coauthors, using these data to explore the effects of birth order on outcomes including human capital accumulation, earnings, development of cognitive and non-cognitive skills, and health.

Birth Order and Economic Success

Almost a half-century ago, economists including Gary Becker, H. Gregg Lewis, and Nigel Tomes created models of quality-quantity trade-offs in child-rearing and used these models to explore the role of family in children's success. They sought to explain an observed negative correlation between family income and family size: if child quality is a normal good, as income rises the family demands higher-quality children at the cost of lower family size. 1

However, this was a difficult model to test, as characteristics other than family income and child quality vary with family size. The introduction of natural experiments, combined with newly available large administrative datasets from Scandinavia, made testing such a model possible.

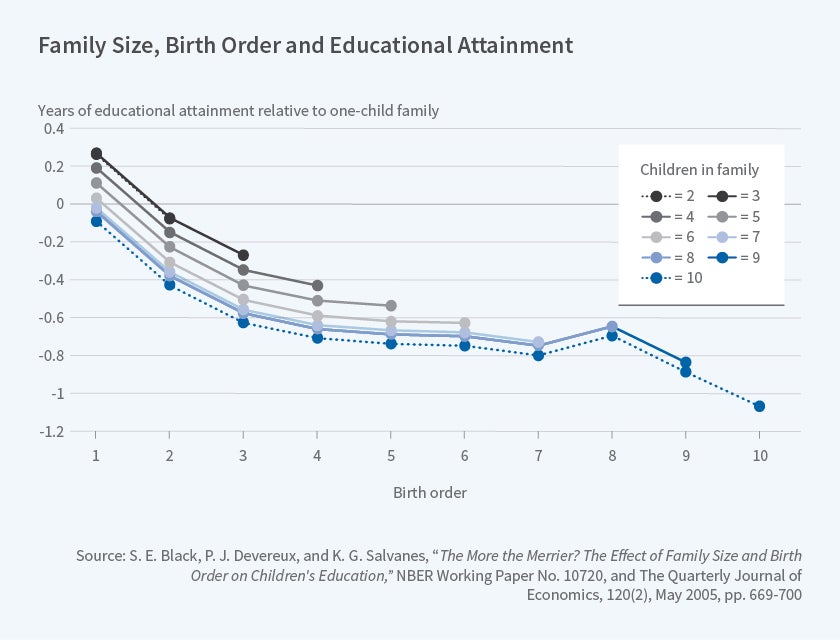

In my earliest work on the topic, Paul Devereux, Kjell Salvanes, and I took advantage of the Norwegian administrative dataset and set out to better understand this theoretical quantity-quality tradeoff. 2 It became clear that child "quality" was not a constant within a family — children within families were quite different, despite the model assumptions to the contrary. Indeed, we found that birth order could explain a large fraction of the family size differential in children's educational outcomes. Average educational attainment was lower in larger families largely because later-born children had lower average education, rather than because firstborns had lower education in large families than in small families. We found that firstborns had higher educational attainment than second-borns who in turn did better than third-borns, and so on. These results were robust to a variety of specifications; most importantly, we could compare outcomes of children within the same families.

To give a sense of the magnitude of these effects: The difference in educational attainment between the first child and the fifth child in a five-child family is roughly equal to the difference between the educational attainment of blacks and whites calculated from the 2000 Census. We augmented the education results by examining earnings, whether full-time employed, and whether one had a child as a teenager as additional outcome variables, and found strong evidence for birth order effects, particularly for women. Later-born women have lower earnings (whether employed full-time or not), are less likely to work full-time, and are more likely to have their first child as teenagers. In contrast, while later-born men have lower full-time earnings, they are not less likely to work full-time [Figure 1].

Birth Order and Cognitive Skills

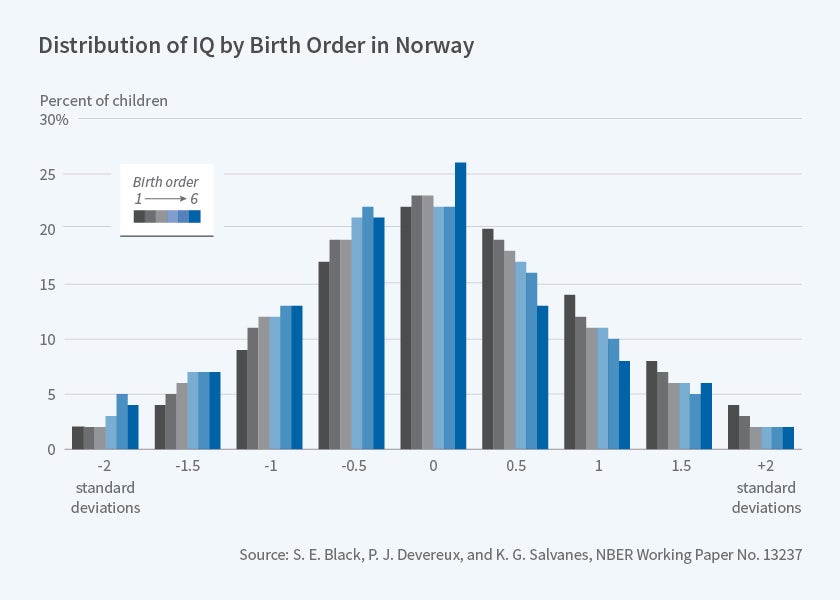

One possible explanation for these differences is that cognitive ability varies systematically by birth order. In subsequent work, Devereux, Salvanes, and I examined the effect of birth order on IQ scores. 3

The psychology literature has long debated the role of birth order in determining children's IQs; this debate was seemingly resolved when, in 2000, J. L. Rodgers et al. published a paper in American Psychologist entitled "Resolving the Debate Over Birth Order, Family Size, and Intelligence" that referred to the apparent relationship between birth order and IQ as a "methodological illusion." 4 However, this work was limited due to the absence of large representative datasets necessary to identify these effects. We again used population register data from Norway to estimate this relationship.

To measure IQ, we used the outcomes of standardized cognitive tests administered to Norwegian men between the age of 18 and 20 when they enlist in the military. Consistent with our earlier findings on educational attainment but in contrast to the previous work in the literature, we found strong birth order effects on IQ that are present when we look within families. Later-born children have lower IQs, on average, and these differences are quite large. For example, the difference between firstborn and second-born average IQ is on the order of one-fifth of a standard deviation, or about three IQ points. This translates into approximately a 2 percent difference in annual earnings in adulthood.

The Effect of Birth Order on Non-Cognitive Skills

Personality is another factor that is posited to vary by birth order, a proposition that has been particularly difficult to assess in a compelling way due to the paucity of large datasets containing information on individual personality. In recent work on the topic, Erik Gronqvist, Bjorn Ockert, and I use Swedish administrative datasets to examine this issue. 5

In the economics literature, personality traits are often referred to as non-cognitive abilities and denote traits that can be distinguished from intelligence. 6 To measure "personality" (or non-cognitive skills), we use the outcome of a standardized psychological evaluation, conducted by a certified psychologist, that is performed on all Swedish men between the ages of 18 and 20 when they enlist in the military, and which is strongly related to success in the labor market. An individual is given a higher score if he is considered to be emotionally stable, persistent, socially outgoing, willing to assume responsibility, and able to take initiative. Similar to the results for cognitive skills, we find evidence of consistently lower scores in this measure for later-born children. Third-born children have non-cognitive abilities that are 0.2 standard deviations below firstborn children. Interestingly, boys with older brothers suffer almost twice as much in terms of these personality characteristics as boys with older sisters.

Importantly, we also demonstrate that these personality differences translate into differences in occupation choice by birth order. Firstborn children are significantly more likely to be employed and to work as top managers, while later-born children are more likely to be self-employed. More generally, firstborn children are more likely to be in occupations requiring sociability, leadership ability, conscientiousness, agreeableness, emotional stability, extraversion, and openness.

The Effect of Birth Order on Health

Finally, how do these differences translate into later health? In more recent work, Devereux, Salvanes, and I analyze the effect of birth order on health. 7 There is a sizable body of literature about the relationship between birth order and adult health; individual studies have typically examined only one or a small number of health outcomes and, in many cases, have used relatively small samples. Again, we use large nationally representative data from Norway to identify the relationship between birth order and health when individuals are in their 40s, where health is measured along a number of dimensions, including medical indicators, health behaviors, and overall life satisfaction.

The effects of birth order on health are less straightforward than other outcomes we have examined, as firstborns do better on some dimensions and worse on others. We find that the probability of having high blood pressure declines with birth order, and the largest gap is between first- and second-borns. Second-borns are about 3 percent less likely to have high blood pressure than firstborns; fifth-borns are about 7 percent less likely to have high blood pressure than firstborns. Given that 24 percent of this population has high blood pressure, this is quite a large difference. Firstborns are also more likely to be overweight and obese. Compared with second-borns, firstborns are 4 percent more likely to be overweight and 2 percent more likely to be obese. The equivalent differences between fifth-borns and firstborns are 10 percent and 5 percent. For context, 47 percent of the population is overweight and 10 percent is obese. Once again, the magnitudes are quite large.

However, later-borns are less likely to consider themselves to be in good health, and measures of mental health generally decline with birth order. Later-born children also exhibit worse health behaviors. The number of cigarettes smoked daily increases monotonically with birth order, suggesting that the higher prevalence of smoking by later-borns found among U.S. adolescents by Laura M. Argys et al. 8 may persist throughout adulthood and, hence, have important effects on health outcomes.

Possible Mechanisms

Why are adult outcomes likely to be affected by birth order? A host of potential explanations has been proposed across several academic disciplines.

A number of biological factors may explain birth order effects. These relate to changes in the womb environment or maternal immune system that occur over successive births. Beyond biology, parents could have other influences. Childhood inputs, especially in the first years of life, are considered crucial for skill formation. 9 Firstborn children have the full attention of parents, but as families grow the family environment is diluted and parental resources become scarcer. 10 In contrast, parents are more experienced and tend to have higher incomes when raising later-born children. In addition, for a given amount of resources, parents may treat firstborn children differently than second- or later-born children. Parents may use more strict parenting practices toward the firstborn, so as to gain a reputation for "toughness" necessary to induce good behavior among later-borns. 11

There are also theories that suggest that interactions among siblings can shape birth order effects. For example, based on evolutionary psychology, Frank J. Sulloway suggests that firstborns have an advantage in following the status quo, while later-borns — by having incentives to engage in investments aimed at differentiating themselves — become more sociable and unconventional in order to attract parental resources. 12

In each of these papers, we attempted to identify potential mechanisms for the patterns we observed. However, it is here we see the limitations of these large administrative datasets, as for the most part, we lack necessary detailed information on biological factors and on household dynamics when the children are young. However, we do have some evidence on the role of biological factors. Later-born children tend to have better birth outcomes as measured by factors such as birth weight. In our Swedish data, we took advantage of the fact that some children's biological birth order is different from their environmental birth order, due to the death of an older sibling or because their parent gave up a child for adoption. When we examine this subsample, we find that the birth order effect on occupational choice is entirely driven by the environmental birth order, again suggesting that biological factors may not be central.

Also in our Swedish study, we found that firstborn teenagers are more likely to read books, spend more time on homework, and spend less time watching TV or playing video games. Parents spend less time discussing school work with later-born children, suggesting there may be differences in parental time investments. Using Norwegian data, we found that smoking early in pregnancy is more prevalent for first pregnancies than for later ones. However, women are more likely to quit smoking during their first pregnancy than during later ones, and firstborns are more likely to be breastfed. These findings suggest that early investments may systematically benefit firstborns and help explain their generally better outcomes.

In the past two decades, with the increased accessibility of administrative datasets on large swaths of the population, economists and other researchers have been better able to identify the role of birth order in the outcomes of children. There is strong evidence of substantial differences by birth order across a range of outcomes. While I have described several of my own papers on the topic, a number of other researchers have also taken advantage of newly available datasets in Florida and Denmark to examine the role of birth order on other important outcomes, specifically juvenile delinquency and later criminal behavior. 13 Consistent with the work discussed here, later-born children experience higher rates of delinquency and criminal behavior; this is at least partly attributable to time investments of parents.

Researchers

More from nber.

G. Becker, "An Economic Analysis of Fertility," in Demographic and Economic Change in Developed Countries , New York, Columbia University Press, 1960, pp. 209-40; G. Becker and H. Lewis, "Interaction Between Quantity and Quality of Children," in Economics of the Family: Marriage, Children, and Human Capital , 1974, pp. 81-90; G. Becker and N. Tomes, "Child Endowments, and the Quantity and Quality of Children," NBER Working Paper 123 , February 1976.

S. Black, P. Devereux, and K. Salvanes, "The More the Merrier? The Effect of Family Composition on Children's Education" NBER Working Paper 10720 , September 2004, and Quarterly Journal of Economics , 120(2), 2005, pp. 669-700.

S. Black, P. Devereux, and K. Salvanes, "Older and Wiser? Birth Order and the IQ of Young Men," NBER Working Paper 13237 , July 2007, and CESifo Economic Studies , Oxford University Press, vol. 57(1), pages 103-20, March 2011.

J. Rodgers, H. Cleveland, E. van den Oord, and D. Rowe, "Resolving the Debate Over Birth Order, Family Size, and Intelligence," American Psychologist , 55(6), 2000, pp. 599-612.

S. Black, E. Gronqvist, and B. Ockert, "Born to Lead? The Effect of Birth Order on Non-Cognitive Abilities," NBER Working Paper 23393 , May 2017.

L. Borghans, A. Duckworth, J. Heckman, and B. ter Weel, "The Economics and Psychology of Personality Traits," Journal of Human Resources , 43, 2008, pp. 972-1059.

S. Black, P. Devereux, K. Salvanes, "Healthy (?), Wealthy, and Wise: Birth Order and Adult Health, NBER Working Paper 21337 , July 2015.

L. Argys, D. Rees, S. Averett, and B. Witoonchart, "Birth Order and Risky Adolescent Behavior," Economic Inquiry , 44(2), 2006, pp. 215-33.

F. Cunha and J. Heckman, "The Technology of Skill Formation," NBER Working Paper 12840 , January 2007.

R. Zajonc and G. Markus, "Birth Order and Intellectual Development," Psychological Review , 82(1), 1975, pp. 74-88; R. Zajonc, "Family Configuration and Intelligence," Science , 192(4236), 1976, pp. 227-36; J. Price, "Parent-Child Quality Time: Does Birth Order Matter?" in Journal of Human Resources , 43(1), 2008, pp. 240-65; J.Lehmann, A. Nuevo-Chiquero, and M. Vidal-Fernandez, "The Early Origins of Birth Order Differences in Children's Outcomes and Parental Behavior," forthcoming in Journal of Human Resources .

V. Hotz and J. Pantano, "Strategic Parenting, Birth Order, and School Performance," NBER Working Paper 19542 , October 2013, and Journal of Population Economics , 28(4), 2015, pp. 911-936. ↩

F. Sulloway, Born to Rebel: Birth Order, Family Dynamics, and Creative Lives , New York, Pantheon Books, 1996.

S. Breining, J. Doyle, D. Figlio, K. Karbownik, J. Roth, "Birth Order and Delinquency: Evidence from Denmark and Florida," NBER Working Paper 23038 , January 2017.

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

© 2023 National Bureau of Economic Research. Periodical content may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Birth Order

Introduction, general overviews.

- Parental Investment

- Sibling Niche Theory

- Methodological Issues and Research Design

- Politics and the Life Sciences Controversy: Agendas and Methodology

- Birth Order Stereotypes

- Personality

- Family Dynamics

- Friendship and Cooperation

- Sexual/Romantic Relationships

- Sexual Orientation and the Fraternal Birth Order Effect

- Intelligence

- Challenges to Confluence Theory of Intelligence

- Theory of Mind/Cognitive Skills

- The Workplace

- Religion and Politics

- Risk-Taking

- Consumer Behavior

- Mental and Physical Health

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Developmental Psychology (Social)

- Personality Psychology

- Twin Studies

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Data Visualization

- Remote Work

- Workforce Training Evaluation

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Birth Order by Catherine Salmon LAST REVIEWED: 29 October 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 29 October 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0103

Birth order, defined as an individual’s rank by age among siblings, has long been of interest to psychologists as well as lay-people. Much of the fascination has focused on the possible role of birth order in shaping personality and behavior. Many decades ago, Alfred Adler, a contemporary of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, suggested that personality traits are related to a person’s ordinal position within the family. He claimed that firstborns, once the sole focus of parental attention and resources, would be resentful when attention shifted upon the birth of the next child, and that this would result in neuroticism and possible substance abuse. In his view, lastborns would be spoiled and emotionally immature, while middle children would be the most stable, as they never experienced dethronement or being spoiled. Adler’s work led to an explosion of birth order studies examining the relationships between birth order and pretty much any topic one can think of, from personality traits to psychiatric disorders, intelligence, creativity, and sexual orientation. Not all of the research employed controls for other relevant factors, a number of hard-hitting critiques of the field were made, and the number of studies being done waned. Currently, the common view is that genetic differences account for a substantial portion (around 40 percent) of the variance in personality, for example, but that a similar amount of variance (around 35 percent) is due to non-shared environment, while the remainder is due to shared environment and measurement error. Birth order is one part of the non-shared environment. Siblings may grow up in the same family, but they do not all experience that family environment in the same way. Recently, researchers have suggested that birth order shapes strategies for dealing with the family environment, some of which may manifest themselves in settings outside the family domain. The first section of this article introduces general overviews or reviews of the birth order literature as well as some general theoretical perspectives and aspects of the debate over the important of birth order effects. The remaining sections examine the research in various areas where birth order has been well studied.

A wide variety of articles and books provide insight into the theoretical perspectives on birth order as well as reviewing portions of the field. Birth order research touches on many somewhat specialized areas of psychology; for example, cognition, child and lifespan development, social, and personality psychology, and reviews typically focus on just one specific aspect, most frequently personality. Research can be largely atheoretical or may come from an Adlerian perspective or a Darwinian one. There are a number of books and reviews that challenge the impact of birth order, including Harris 1998 , and just as many that argue for strong effects, such as Sulloway 1996 and Sulloway 2010 . Those interested in mastering the birth order literature have a lot of reading ahead of them; thousands of articles have been published. But the articles and books included here will acquaint the reader with the major debates within the field and will highlight the most consistent of findings (and the least). The narrative review of Schooler 1972 provides evidence that the impact of birth order is overstated, while Ernst and Angst 1983 is a well known review of the birth order literature from the 1940s to 1980 that suggests that birth order does not influence personality. Many of the studies it references later became part of Sulloway’s meta-analysis. Plomin, et al. 2001 revisits the role of non-shared environment in answering the question of why siblings are so different from each other with a behavioral genetics influence. Eckstein 2000 and Eckstein, et al. 2010 are influenced by the Adlerian perspective and focus mainly on studies that providence evidence for birth order differences in personality traits.

Eckstein, D. 2000. Empirical studies indicating significant birth-order related personality differences. Journal of Individual Psychology 56:481–494.

A review of studies, largely published between 1960 and 1999, that provides support for birth order differences in personality. Includes studies that relate to traits of firstborns, middleborns, lastborns, and only children. Shows the range of study topics from conformity to narcissism. Illustrates greater research focus on firstborns historically.

Eckstein, D., K. J. Aycock, M. A. Sperber, et al. 2010. A review of 200 birth-order studies: Lifestyle characteristics . Journal of Individual Psychology 66:408–434.

Gives Adlerian perspective and reviews Sulloway and his critics. Provides tables of characteristics by birth order (first/middle/last/only) and the statistically significant related studies from 1960–2010. Does not address non-significant study results, but an otherwise comprehensive reference.

Ernst, C., and J. Angst. 1983. Birth order: Its influence on personality . New York: Springer.

Extensive review of birth order literature from 1946 to 1980. Concludes that effects are the result of poor research design, in particular failure to control for family size and socioeconomic status. Suggests that effects are found more often in studies that fail to control and are not found in ones with proper controls. The meta-analysis of Sulloway 1996 was a statistical counter to this paper.

Harris, J. R. 1998. The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do . New York: Free Press.

Argues that genes and peers shape personality more than parents (and by extension birth order) do and that, while parental love and attention are not distributed evenly and siblings do compete, these experiences do not translate into their relationships with non-kin. Focuses more on peers and socialization.

Plomin, R., K. Asbury, P. G. Dip, and J. Dunn. 2001. Why are children in the same family so different? Non-shared environment a decade later. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 46:225–233.

Behavioral genetics approach considers what aspects make up non-shared environment for siblings (parental favoritism, peers, interaction between genetics and environment). Plomin is one of first to highlight this question. Calls for more research and for consideration of role of chance. Available online for purchase or by subscription.

Schooler, C. 1972. Birth order effects: Not here, not now. Psychological Bulletin 78:161–175.

DOI: 10.1037/h0033026

Early narrative review of the literature on “normal” and psychiatric populations. Raises family size issues. No discussion of issues involved with using self-report of parental treatment of offspring. Studies are largely confined to comparing firstborns to lastborns or laterborns (everyone but firstborns), which is another issue not discussed (see Methodological Issues and Research Design ). Available online for purchase or by subscription.

Sulloway, F. J. 1996. Born to rebel: Birth order, family dynamics, and creative lives . New York: Pantheon.

Makes solid case for Darwinian theoretical approach to birth order focusing on differential parental investment and sibling competition. Documents personality differences and how they play out in terms of revolutions in science, religion, and politics. Highlights the rebellious role of the laterborn child.

Sulloway, F. J. 2010. Why siblings are like Darwin’s finches: Birth order, sibling competition, and adaptive divergence within the family. In The Evolution of Personality and Individual Differences . Edited by D. M. Buss and P. H. Hawley, 86–119. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195372090.001.0001

Darwinian approach to birth order, personality divergence among siblings due to differential parental investment and sibling conflict. Focus on sibling niche picking and that sibling divergence is an adaptive strategy. Covers wide range of studies in review.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Psychology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abnormal Psychology

- Academic Assessment

- Acculturation and Health

- Action Regulation Theory

- Action Research

- Addictive Behavior

- Adolescence

- Adoption, Social, Psychological, and Evolutionary Perspect...

- Advanced Theory of Mind

- Affective Forecasting

- Affirmative Action

- Ageism at Work

- Allport, Gordon

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Ambulatory Assessment in Behavioral Science

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA)

- Animal Behavior

- Animal Learning

- Anxiety Disorders

- Art and Aesthetics, Psychology of

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Psychology

- Assessment and Clinical Applications of Individual Differe...

- Attachment in Social and Emotional Development across the ...

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Childre...

- Attitudinal Ambivalence

- Attraction in Close Relationships

- Attribution Theory

- Authoritarian Personality

- Bayesian Statistical Methods in Psychology

- Behavior Therapy, Rational Emotive

- Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Genetics

- Belief Perseverance

- Bereavement and Grief

- Biological Psychology

- Birth Order

- Body Image in Men and Women

- Bystander Effect

- Categorical Data Analysis in Psychology

- Childhood and Adolescence, Peer Victimization and Bullying...

- Clark, Mamie Phipps

- Clinical Neuropsychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Consistency Theories

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Communication, Nonverbal Cues and

- Comparative Psychology

- Competence to Stand Trial: Restoration Services

- Competency to Stand Trial

- Computational Psychology

- Conflict Management in the Workplace

- Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

- Consciousness

- Coping Processes

- Correspondence Analysis in Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Creativity at Work

- Critical Thinking

- Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Cultural Psychology

- Daily Life, Research Methods for Studying

- Data Science Methods for Psychology

- Data Sharing in Psychology

- Death and Dying

- Deceiving and Detecting Deceit

- Defensive Processes

- Depressive Disorders

- Development, Prenatal

- Developmental Psychology (Cognitive)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM...

- Discrimination

- Dissociative Disorders

- Drugs and Behavior

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Psychology

- Educational Settings, Assessment of Thinking in

- Effect Size

- Embodiment and Embodied Cognition

- Emerging Adulthood

- Emotional Intelligence

- Empathy and Altruism

- Employee Stress and Well-Being

- Environmental Neuroscience and Environmental Psychology

- Ethics in Psychological Practice

- Event Perception

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Expansive Posture

- Experimental Existential Psychology

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Eyewitness Testimony

- Eysenck, Hans

- Factor Analysis

- Festinger, Leon

- Five-Factor Model of Personality

- Flynn Effect, The

- Forensic Psychology

- Forgiveness

- Friendships, Children's

- Fundamental Attribution Error/Correspondence Bias

- Gambler's Fallacy

- Game Theory and Psychology

- Geropsychology, Clinical

- Global Mental Health

- Habit Formation and Behavior Change

- Health Psychology

- Health Psychology Research and Practice, Measurement in

- Heider, Fritz

- Heuristics and Biases

- History of Psychology

- Human Factors

- Humanistic Psychology

- Implicit Association Test (IAT)

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Inferential Statistics in Psychology

- Insanity Defense, The

- Intelligence, Crystallized and Fluid

- Intercultural Psychology

- Intergroup Conflict

- International Classification of Diseases and Related Healt...

- International Psychology

- Interviewing in Forensic Settings

- Intimate Partner Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Introversion–Extraversion

- Item Response Theory

- Law, Psychology and

- Lazarus, Richard

- Learned Helplessness

- Learning Theory

- Learning versus Performance

- LGBTQ+ Romantic Relationships

- Lie Detection in a Forensic Context

- Life-Span Development

- Locus of Control

- Loneliness and Health

- Mathematical Psychology

- Meaning in Life

- Mechanisms and Processes of Peer Contagion

- Media Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Mediation Analysis

- Memories, Autobiographical

- Memories, Flashbulb

- Memories, Repressed and Recovered

- Memory, False

- Memory, Human

- Memory, Implicit versus Explicit

- Memory in Educational Settings

- Memory, Semantic

- Meta-Analysis

- Metacognition

- Metaphor, Psychological Perspectives on

- Microaggressions

- Military Psychology

- Mindfulness

- Mindfulness and Education

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- Money, Psychology of

- Moral Conviction

- Moral Development

- Moral Psychology

- Moral Reasoning

- Nature versus Nurture Debate in Psychology

- Neuroscience of Associative Learning

- Nonergodicity in Psychology and Neuroscience

- Nonparametric Statistical Analysis in Psychology

- Observational (Non-Randomized) Studies

- Obsessive-Complusive Disorder (OCD)

- Occupational Health Psychology

- Olfaction, Human

- Operant Conditioning

- Optimism and Pessimism

- Organizational Justice

- Parenting Stress

- Parenting Styles

- Parents' Beliefs about Children

- Path Models

- Peace Psychology

- Perception, Person

- Performance Appraisal

- Personality and Health

- Personality Disorders

- Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies: From Car...

- Phenomenological Psychology

- Placebo Effects in Psychology

- Play Behavior

- Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

- Positive Psychology

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Prejudice and Stereotyping

- Pretrial Publicity

- Prisoner's Dilemma

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Procrastination

- Prosocial Behavior

- Prosocial Spending and Well-Being

- Protocol Analysis

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Literacy

- Psychological Perspectives on Food and Eating

- Psychology, Political

- Psychoneuroimmunology

- Psychophysics, Visual

- Psychotherapy

- Psychotic Disorders

- Publication Bias in Psychology

- Reasoning, Counterfactual

- Rehabilitation Psychology

- Relationships

- Reliability–Contemporary Psychometric Conceptions

- Religion, Psychology and

- Replication Initiatives in Psychology

- Research Methods

- Risk Taking

- Role of the Expert Witness in Forensic Psychology, The

- Sample Size Planning for Statistical Power and Accurate Es...

- Schizophrenic Disorders

- School Psychology

- School Psychology, Counseling Services in

- Self, Gender and

- Self, Psychology of the

- Self-Construal

- Self-Control

- Self-Deception

- Self-Determination Theory

- Self-Efficacy

- Self-Esteem

- Self-Monitoring

- Self-Regulation in Educational Settings

- Self-Report Tests, Measures, and Inventories in Clinical P...

- Sensation Seeking

- Sex and Gender

- Sexual Minority Parenting

- Sexual Orientation

- Signal Detection Theory and its Applications

- Simpson's Paradox in Psychology

- Single People

- Single-Case Experimental Designs

- Skinner, B.F.

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Small Groups

- Social Class and Social Status

- Social Cognition

- Social Neuroscience

- Social Support

- Social Touch and Massage Therapy Research

- Somatoform Disorders

- Spatial Attention

- Sports Psychology

- Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE): Icon and Controversy

- Stereotype Threat

- Stereotypes

- Stress and Coping, Psychology of

- Student Success in College

- Subjective Wellbeing Homeostasis

- Taste, Psychological Perspectives on

- Teaching of Psychology

- Terror Management Theory

- Testing and Assessment

- The Concept of Validity in Psychological Assessment

- The Neuroscience of Emotion Regulation

- The Reasoned Action Approach and the Theories of Reasoned ...

- The Weapon Focus Effect in Eyewitness Memory

- Theory of Mind

- Therapy, Cognitive-Behavioral

- Thinking Skills in Educational Settings

- Time Perception

- Trait Perspective

- Trauma Psychology

- Type A Behavior Pattern (Coronary Prone Personality)

- Unconscious Processes

- Video Games and Violent Content

- Virtues and Character Strengths

- Women and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM...

- Women, Psychology of

- Work Well-Being

- Wundt, Wilhelm

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.39.149.46]

- 185.39.149.46

January 1, 2010

How Birth Order Affects Your Personality

For decades the evidence has been inconclusive, but new studies show that family position may truly affect intelligence and personality

By Joshua K. Hartshorne

Sally Anscombe Getty Images

WHEN I TELL PEOPLE I study whether birth order affects personality, I usually get blank looks. It sounds like studying whether the sky is blue. Isn’t it common sense? Popular books invoke birth order for self-discovery, relationship tips, business advice and parenting guidance in titles such as The Birth Order Book: Why You Are the Way You Are (Revell, 2009). Newspapers and morning news shows debate the importance of the latest findings (“Latter-born children engage in more risky behavior; what should parents do?”) while tossing in savory anecdotes (“Did you know that 21 of the first 23 astronauts into space were firstborns?”).

But when scientists scrutinized the data, they found that the evidence just did not hold up. In fact, until very recently there were no convincing findings that linked birth order to personality or behavior. Our common perception that birth order matters was written off as an example of our well-established tendency to remember and accept evidence that supports our pet theories while readily forgetting or overlooking that which does not. But two studies from the past three years finally found measurable effects: our position in the family does indeed affect both our IQ and our personality. It may be time to reconsider birth order as a real influence over whom we grow up to be.

Size Matters Before discussing the new findings, it will help to explain why decades of research that seemed to show birth-order effects was, in fact, flawed. Put simply, birth order is intricately linked to family size. A child from a two-kid family has a 50 percent chance of being a firstborn, whereas a child from a five-kid family has only a 20 percent chance of being a firstborn. So the fact that astronauts are disproportionately firstborns, for example, could merely show that they come from smaller families—not that firstborns have any particularly astronautic qualities. (Of course, firstborns may indeed have astronautic qualities. The point is that with these data, we cannot tell.)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

There are many reasons that family size could affect our predilections and personalities. More children mean that parental resources (money, time and attention) have to be spread more thinly. Perhaps more telling, family size is associated with many important social factors, such as ethnicity, education and wealth. For example, wealthier, better-educated parents typically have fewer children. If astronauts are more likely to have well-educated, comfortable parents, then they are also more likely to come from a smaller family and thus are more likely to be a firstborn.

Of the some 65,000 scholarly articles about birth order indexed by Google Scholar, the vast majority suffer from this problem, making the research difficult to interpret. Many of the few remaining studies fail to show significant effects of birth order. In 1983 psychiatrists Cecile Ernst and Jules Angst of the University of Zurich determined, after a thorough review of the literature, that birth-order effects were not supported by the evidence. In 1998 psychologist Judith Rich Harris published another comprehensive attack on the concept in The Nurture Assumption (Free Press). By 2003 cognitive scientist Steven Pinker of Harvard University found it necessary to spend only two pages of his 439-page discussion of nature and nurture, The Blank Slate (Penguin), dismissing birth order as irrelevant.

New Evidence Even so, the case in 2003 against birth-order effects was mainly an absence of good evidence, rather than evidence of an absence. In fact, the past few years have provided good news for the theory. In 2007 Norwegian epidemiologists Petter Kristensen and Tor Bjerkedal published work showing a small but reliable negative correlation between IQ and birth order: the more older siblings one has, the lower one’s IQ. Whether birth order affects intelligence has been debated inconclusively since the late 1800s, although the sheer size of the study (about 250,000 Norwegian conscripts) and the rigorous controls for family size make this study especially convincing.

In 2009 my colleagues and I published evidence that birth order influences whom we choose as friends and spouses. Firstborns are more likely to associate with firstborns, middle-borns with middle-borns, last-borns with last-borns, and only children with only children. Because we were able to show the effect independent of family size, the finding is unlikely to be an artifact of class or ethnicity. The result is exactly what we should expect if birth order affects personality. Despite the adage that opposites attract, people tend to resemble their spouses in terms of personality. If spouses correlate on personality, and personality correlates with birth order, spouses should correlate on birth order.

Thus, the evidence seems to be shifting back in favor of our common intuition that our position in our family somehow affects who we become. The details, however, remain vague. The Norwegian study shows a slight effect on intelligence. The relationship study shows that oldest, middle, youngest and only children differ in some way yet gives no indication as to how. Moreover, although these effects are reasonably sized by the standards of research, they are small enough that it would not make any sense to organize college admissions or dating pools around birth order, much less NASA applicants.

Still, I expect people—myself included—will continue to try to make sense of the world through the prism of birth order. It’s fine for scientists to say “more study is needed,” but we must find love, gain self-knowledge and parent children now . In that sense, a great deal about who we are and how we think can be learned reading those shelves of birth order–related self-help books, even if the actual content is not yet—or will never be—experimentally confirmed.

Note this story was originally published with the title "Ruled by Birth Order?"

Joshua K. Hartshorne is a Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA post-doctoral fellow in the Computational Cognitive Science group at MIT and an occasional contributor to Scientific American Mind. He conducts research both in his brick-and-mortar laboratory and online at GamesWithWords.org. You can follow him on Twitter at @jkhartshorne.

Birth order and unwanted fertility

- Original Paper

- Published: 22 August 2019

- Volume 33 , pages 413–440, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Wanchuan Lin 1 ,

- Juan Pantano 2 &

- Shuqiao Sun 3

1492 Accesses

7 Citations

24 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

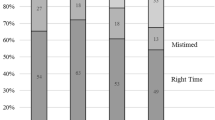

An extensive literature documents the effects of birth order on various individual outcomes, with later-born children faring worse than their siblings. However, the potential mechanisms behind these effects remain poorly understood. This paper leverages US data on pregnancy intention to study the role of unwanted fertility in the observed birth order patterns. We document that children higher in the birth order are much more likely to be unwanted, in the sense that they were conceived at a time when the family was not planning to have additional children. Being an unwanted child is associated with negative life cycle outcomes as it implies a disruption in parental plans for optimal human capital investment. We show that the increasing prevalence of unwantedness across birth order explains a substantial part of the documented birth order effects in education and employment. Consistent with this mechanism, we document no birth order effects in families who have more control over their own fertility.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Births that are Later-than-Desired: Correlates and Consequences

Caroline Sten Hartnett & Rachel Margolis

Selection Bias in the Link Between Child Wantedness and Child Survival: Theory and Data From Matlab, Bangladesh

David Bishai, Abdur Razzaque, … Michelle Hindin

Trajectories of Unintended Fertility

Sowmya Rajan, S. Philip Morgan, … Karen Benjamin Guzzo

We follow the demographic definition of an unwanted birth as a birth in excess of total desired fertility. The broader notion of unintended birth includes both unwanted and mistimed births. Given our purposes, we do not consider mistimed births.

The birth order literature is more limited in developing countries so little is known about how these patterns generalize to that context. For a few exceptions, see Birdsall ( 1979 , 1990 ), Behrman( 1988 ), Horton ( 1988 ), Ejrnæs and Pörtner ( 2004 ), Edmonds ( 2006 ) and De Haan et al. ( 2014 )

See Kessler ( 1991 ) for additional early references.

See among others (Baydar 1995 ; Kubička et al. 1995 ; Myhrman et al. 1995 ).

The indicator is not defined for those who reported being out of labor force for the entire year.

Children who result from mistimed pregnancies, particularly when these occur before marriage, may also have negative effects on outcomes later in life. See, for example, (Nguyen 2018 )

Joyce et al. ( 2002 ) find that prospective and retrospective reports of pregnancy intention provide the same estimate of the effects of being an unintended child on various prenatal outcomes once they control for selective pregnancy recognition using an IV procedure. Further, they show that the extent of unwanted fertility was the same regardless of whether the assessment was during pregnancy or after birth. They show this for a subsample of women for whom pregnancy intention was assessed both prospectively (during pregnancy) and retrospectively (after birth).

In principle, since we are looking at families with two and three children, the number of first-born and second-born children should be the same. In practice however, our number of second-born children is slightly smaller than the number of first-borns because they are more likely to have missing information on our outcome of interest, completed education.

However, it is of interest to explore whether the pattern of increasing prevalence of unwanted children across birth order holds in 4-child families. Since we only know whether the first, last, or second to last child in a family was unwanted, we cannot tell whether a second-born child in a four-child family was unwanted. But we can still look at first-, third-, and fourth-born children in those families. Consistent with the patterns in Table 2 , we find that in four-child families, the incidence of unwanted children grows from 16% among first-borns, to 27% among third-borns to a whopping 53% among fourth-borns.

These are families for which we identify at least one unwanted child or families for which information for pregnancy status is missing for at least one child.

We follow the religion taxonomy in Evans ( 2002 ) and classify the following religions as having a more strict attitude against abortion: Roman Catholic, Protestant, other Protestant, other Non-Christian, Latter Day Saints, Mormon, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Greek/Russian/Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, Christian, Christian Science, Seventh Day Adventist, Pentecostal, Jewish, Amish, and Mennonite. Mothers reporting these religions are more likely to be pro-life and less likely to use abortion to terminate unwanted pregnancies. We then classify Baptists, Episcopalians, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Unitarians along with Agnostics and Atheists as having a less strict attitude towards abortion.

In the pooled specification, the effects for the third child are statistically significantly different from each other across the two tables.

Ananat EO, Hungerman DM (2012) The power of the pill for the next generation: oral contraception’s effects on fertility, abortion, and maternal and child characteristics. Rev Econ Stat 94(1):37–51

Google Scholar

Argys LM, Rees DI, Averett SL, Witoonchart BK (2006) Birth order and risky adolescent behavior. Econ Enquiry 44(2):215–233

Averett SL, Argys LM, Rees DI (2011) Older siblings and adolescent risky behavior: does parenting play a role? J Popul Econ 24(3):957–978

Bagger J, Birchenall JA, Mansour H, Urzua S (2013) Education, birth order, and family size. Working Paper 19111, National Bureau of Economic Research

Bailey MJ (2010) “Momma’s got the pill”: How Anthony Comstock and Griswold v. Connecticut shaped US childbearing. Amer Econ Rev 100(1):98–129

Barmby T, Cigno A (1990) A sequential probability model of fertility patterns. J Popul Econ 3(1):31–51

Baydar N (1995) Consequences for children of their birth planning status. Fam Plan Perspect 27(6):228–245

Becker GS, Lewis HG (1973) On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 81(2, Part 2):S279–S288

Behrman JR, Pollak RA, Taubman P (1982) Parental preferences and provision for progeny. J Polit Econ 90(1):52–73

Behrman JR, Taubman P (1986) Birth order, schooling, and earnings. J Labor Econ 4(3, Part 2):S121–S145

Behrman JR (1988) Nutrition, health, birth order and seasonality: Intrahousehold allocation among children in rural india. J Dev Econ 28(1):43–62

Belmont L, Marolla FA (1973) Birth order, family size, and intelligence. Science 182(4117):1096–1101

Birdsall N (1979) Siblings and schooling in urban colombia. Ph.D. thesis, Yale University

Birdsall N (1990) Birth order effects and time allocation. Res Popul Econ 7:191–213

Björkegren E, Svaleryd H (2017) Birth order and child health. Working paper, Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2005) The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. Q J Econ 120(2):669–700

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2011) Older and wiser? birth order and iq of young men. CESifo Econ Stud 57(1):103–120

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2016) Healthy (?), wealthy, and wise: Birth order and adult health. Econ Human Biol 23:27–45

Black SE, Grönqvist E, Öckert B (2017) Born to lead? the effect of birth order on non-cognitive abilities. Working Paper 23393, National Bureau of Economic Research

Booth AL, Kee HJ (2009) Birth order matters: the effect of family size and birth order on educational attainment. J Popul Econ 22(2):367–397

Breining S, Doyle J, Figlio D, Karbownik K, Roth J (2017) Birth order and delinquency: Evidence from Denmark and Florida. Working Paper 23394, National Bureau of Economic Research

Brenøe AA, Molitor R (2018) Birth order and health of newborns. J Popul Econ 31(2):397–395

Charles KK, Stephens Jr M (2006) Abortion legalization and adolescent substance use. J Law Econ 49(2):481–505

Child Trends (2013) Unintended births

Conley D, Glauber R (2006) Parental educational investment and children’s academic risk: Estimates of the impact of sibship size and birth order from exogenous variation in fertility. J Hum Resour 41(4):722–737

De Haan M (2010) Birth order, family size and educational attainment. Econ Educ Rev 29(4):576–588

De Haan M, Plug E, Rosero J (2014) Birth order and human capital development evidence from ecuador. J Hum Resour 49(2):359–392

Do Q-T, Phung TD (2010) The importance of being wanted. Amer Econ J: Appl Econ 2(4):236–253

Donohue JJ, Grogger J, Levitt SD (2009) The impact of legalized abortion on teen childbearing. Amer Law Econ Rev 11(1):24–46

Donohue JJ, Levitt SD (2001) The impact of legalized abortion on crime. Q J Econ 116(2):379–420

Eckstein D, Aycock KJ, Sperber MA, McDonald J, Van Wiesner V, Watts III RE, Ginsburg P (2010) A review of 200 birth-order studies: Lifestyle characteristics. J Individ Psychol 66(4):408–434

Edmonds EV (2006) Understanding sibling differences in child labor. J Popul Econ 19(4):795–821

Ejrnæs M, Pörtner CC (2004) Birth order and the intrahousehold allocation of time and education. Rev Econ Stat 86(4):1008–1019

Ermisch JF, Francesconi M (2001) Family structure and children’s achievements. J Popul Econ 14(2):249–270

Evans JH (2002) Polarization in abortion attitudes in u.s. religious traditions, 1972–1998. Sociol Forum 17(3):397–422

Galton F (1875) English men of science: Their nature and nurture. D. Appleton

Gruber J, Levine P, Staiger D (1999) Abortion legalization and child living circumstances: who is the ”marginal child”? Q J Econ 114(1):263–291

Hao L, Hotz VJ, Jin GZ (2008) Games parents and adolescents play: Risky behaviour, parental reputation and strategic transfers. Econ J 118(528):515–555

Horton S (1988) Birth order and child nutritional status: evidence from the philippines. Econ Dev Cult Chang 36(2):341–354

Hotz VJ, Pantano J (2015) Strategic parenting, birth order and school performance. J Popul Econ 28(4):911–936

Joyce TJ, Kaestner R, Korenman S (2000) The effect of pregnancy intention on child development. Demography 37(1):83–94

Joyce TJ, Kaestner R, Korenman S (2002) On the validity of retrospective assessments of pregnancy intention. Demography 39(1):199–213

Kantarevic J, Mechoulan S (2006) Birth order, educational attainment, and earnings an investigation using the PSID. J Hum Resour 41(4):755–777

Kessler D (1991) Birth order, family size, and achievement: Family structure and wage determination. J Labor Econ 9(4):413–426

Kubička L, Matějček Z, David H, Dytrych Z, Miller W, Roth Z (1995) Children from unwanted pregnancies in prague, Czech Republic revisited at age thirty. Acta Psychiatr Scand 91(6):361–369

Lehmann J-YK, Nuevo-Chiquero A, Vidal-Fernandez M (2013) Birth order and differences in early inputs and outcomes. Discussion Paper 6755, IZA Institute of Labor Economics

Lin W, Pantano J (2015) The unwanted: Negative outcomes over the life cycle. J Popul Econ 28(2):479–508

Lin W, Pantano J, Pinto R, Sun S (2017) Identification of quantity quality tradeoff with imperfect fertility control. Unpublished working paper

Lindert PH (1977) Sibling position and achievement. J Hum Resour 12 (2):198–219

Mechoulan S, Wolff F-C (2015) Intra-household allocation of family resources and birth order: evidence from France using siblings data. J Popul Econ 28(4):937–964

Michael RT, Willis RJ (1976) Contraception and fertility: Household production under uncertainty. In: Household Production and Consumption. NBER, pp 25–98

Miller AR (2009) Motherhood delay and the human capital of the next generation. Am Econ Rev 99(2):154–58

Myhrman A, Olsen P, Rantakallio P, Laara E (1995) Does the wantedness of a pregnancy predict a child’s educational attainment? Fam Plan Perspect 27 (3):116–119

Nguyen CV (2018) The long-term effects of mistimed pregnancy on children’s education and employment. J Popul Econ 31(3):937–968

Ozbeklik S (2014) The effect of abortion legalization on childbearing by unwed teenagers in future cohorts. Econ Inq 52(1):100–115

Pavan R (2016) On the production of skills and the birth order effect. J Hum Resour 51(3):699–726

Pop-Eleches C (2006) The impact of an abortion ban on socioeconomic outcomes of children: Evidence from romania. J Polit Econ 114(4):744–773

Price J (2008) Parent-child quality time: Does birth order matter? J Hum Resour 43(1):240–265

Rosenzweig MR, Wolpin KI (1993) Maternal expectations and ex post rationalizations: the usefulness of survey information on the wantedness of children. J Hum Resour 23(2):205–229

Schoen R, Astone NM, Kim YJ, Nathanson CA, Fields JM (1999) Do fertility intentions affect fertility behavior? J Marriage Fam 61(3):790–799

Sulloway FJ (2010) Why siblings are like darwin’s finches: Birth order, sibling competition, and adaptive divergence within the family. In: The Evolution of Personality and Individual Differences. Oxford University Press, New York

Westoff CF, Ryder NB (1977) The predictive validity of reproductive intentions. Demography 14(4):431–453

Willis RJ (1973) A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. J Polit Econ 81(2, Part 2):S14–S64

Download references

Acknowledgments

We thank Janet Currie, Joe Doyle, Martha Bailey and seminar participants at the University of Michigan for helpful comments. Lin acknowledges research support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.71573004) and the Key Laboratory of Mathematical Economics and Quantitative Finance (Peking University), Ministry of Education. During work on this project, Sun was supported in part by the George Katona Economic Behavior Research Award funded by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan. All errors remain our own. The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions.

Wanchuan Lin acknowledges research support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.71573004) and the Key Laboratory of Mathematical Economics and Quantitative Finance (Peking University), Ministry of Education. Shuqiao Sun was supported by the George Katona Economic Behavior Research Award, funded by the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Guanghua School of ManagementPeking University, Haidian Qu, Beijing, China

Wanchuan Lin

Department of Economics, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, USA

Juan Pantano

Department of Economics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Shuqiao Sun

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shuqiao Sun .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible editor : Alessandro Cigno

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Lin, W., Pantano, J. & Sun, S. Birth order and unwanted fertility. J Popul Econ 33 , 413–440 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-019-00747-4

Download citation

Received : 19 December 2018

Accepted : 30 July 2019

Published : 22 August 2019

Issue Date : April 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-019-00747-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Birth order

- Unwanted births

- Fertility intentions

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Why Your Big Sister Resents You

“Eldest daughter syndrome” assumes that birth order shapes who we are and how we interact. Does it?

By Catherine Pearson

Catherine Pearson is a younger daughter who still leans on her older sister for guidance all the time.

In a TikTok video that has been watched more than 6 million times, Kati Morton, a licensed marriage and family therapist in Santa Monica, Calif., lists signs that she says can be indicative of “eldest daughter syndrome.”

Among them: an intense feeling of familial responsibility, people-pleasing tendencies and resentment toward your siblings and parents.

On X, a viral post asks : “are u happy or are u the oldest sibling and also a girl”?

Firstborn daughters are having a moment in the spotlight , at least online, with memes and think pieces offering a sense of gratification to responsible, put-upon big sisters everywhere. But even mental health professionals like Ms. Morton — herself the youngest in her family — caution against putting too much stock in the psychology of sibling birth order, and the idea that it shapes personality or long term outcomes.

“People will say, ‘It means everything!’ Other people will say, ‘There’s no proof,’” she said, noting that eldest daughter syndrome (which isn’t an actual mental health diagnosis) may have as much to do with gender norms as it does with birth order. “Everybody’s seeking to understand themselves, and to feel understood. And this is just another page in that book.”

What the research says about birth order

The stereotypes are familiar to many of us: Firstborn children are reliable and high-achieving; middle children are sociable and rebellious (and overlooked); and youngest children are charming and manipulative.

Studies have indeed found ties between a person’s role in the family lineup and various outcomes, including educational attainment and I.Q . (though those scores are not necessarily reliable measures of intelligence ), financial risk tolerance and even participation in dangerous sports . But many studies have focused on a single point in time, cautioned Rodica Damian, a social-personality psychologist at the University of Houston. That means older siblings may have appeared more responsible or even more intelligent simply because they were more mature than their siblings, she said, adding that the sample sizes in most birth order studies have also been relatively small.

In larger analyses, the link between birth order and personality traits appears much weaker. A 2015 study looking at more than 20,000 people in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States found no link between birth order and personality characteristics — though the researchers did find evidence that older children have a slight advantage in I.Q. (So, eldest daughters, take your bragging rights where you can get them.)

Dr. Damian worked on a different large-scale study, also published in 2015 , that included more than 370,000 high schoolers in the United States. It found slight differences in personality and intelligence, but the differences were so small, she said, that they were essentially meaningless. Dr. Damian did allow that cultural practices such as property or business inheritance (which may go to the first born) might affect how birth order influences family dynamics and sibling roles.

Still, there is no convincing some siblings who insist their birth order has predestined their role in the family.

After her study published, Dr. Damian appeared on a call-in radio show. The lines flooded with listeners who were delighted to tell her how skewed her findings were.

“Somebody would say: ‘You’re wrong! I’m a firstborn and I’m more conscientious than my siblings!’ And then someone else would call in and say, ‘You’re wrong, I’m a later-born and I’m more conscientious than my siblings!” she said.

What personal experience says

Sara Stanizai, a licensed marriage and family therapist in Long Beach, Calif., runs a virtual group with weekly meet-ups, where participants reflect on how they believe their birth order has affected them and how it may be continuing to shape their romantic lives, friendships and careers.

The program was inspired by Ms. Stanizai’s experience as an eldest daughter in an Afghan-American family, where she felt “parentified” and “overly responsible” for her siblings — in part because she was older, and in part because she was a girl .

While Ms. Stanizai acknowledged that the research around birth order is mixed, she finds it useful for many of her clients to reflect on their birth order and how they believe it shaped their family life — particularly if they felt hemmed in or saddled by certain expectations.

Her therapy groups spend time reflecting on questions like: How does my family see me? How do I see myself? Can we talk about any discrepancies in our viewpoints, and how they shape family dynamics? For instance, an older sibling might point out that he or she is often the one to plan family vacations. A younger sibling might point out that he or she often feels pressured into going along with whatever the rest of the group wants.

Whether or not there is evidence that birth order determines personality traits is almost beside the point, experts acknowledged.

“I think people are just looking for meaning and self-understanding,” Ms. Stanizai said. “Horoscopes, birth order, attachment styles” are just a few examples, she said. “People are just looking for a set of code words and ways of describing their experiences.”

Catherine Pearson is a Times reporter who writes about families and relationships. More about Catherine Pearson

Explore Our Style Coverage

The latest in fashion, trends, love and more..

An Unusual Path to Hollywood: Sobhita Dhulipala has taken on risky roles in her acting career, outside of India’s blockbuster hits . Now, she’s starring in Dev Patel’s “Monkey Man.”

These Scientists Rock, Literally: The Pasteur Institute in Paris, known for its world-altering scientific research , has been making advancements in another field: the musical arts.

JoJo Siwa Grows Up: Siwa, the child star turned children’s entertainer, who at first modeled her career on Hannah Montana, is now after her own Miley (Cyrus) moment .

Jill Biden Makes an Entrance: The first lady was glittering in crystals — days after Melania Trump stepped out in pink at a Palm Beach fund-raiser. Together, the pictures offer a harbinger of what is to come .

Creating Works of Ephemeral Beauty: A YouTube rabbit hole led Blanka Amezkua to a small Mexican town and the centuries-old craft of papel picado — chiseling intricate patterns into colorful paper flags.

New York Bridal Fashion Week: Reimagined classic silhouettes, a play on textures and interactive presentations brought fresh takes to the spring and summer 2025 bridal collections.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

An Investigation of the Connection between Parenting Styles, Birth Order, Personality, and Sibling Relationships

2019, JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY & BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE

Related Papers

April Bleske-Rechek

Richard E. Watts

Journal of Research in Personality

Todd K Shackelford

Associations between personality traits and the quality of sibling relationships

Hamide Gozu , Joan Newman

Sibling relationship is one of the longest relationships in human life and play a major role since some skills such as nurturance, caretaking, and meeting their own needs and those of other people around them (e.g. spouse, children, and parents) are fostered through sibling interaction. Several studies have been conducted among adults to identify the factors associated with sibling relationships. Despite its seeming importance, only a few researchers have focused on the role of personality type in sibling relationships. The current study examined whether Big-Five personality traits were associated with the quality of sibling relationships among young adults. Participants included 552 university students living in the United States of America (54% female and 46% male) aged 18 to 25 years. Participants completed the Lifespan Sibling Relationship Scale and the Big Five Inventory. A series regression analyses revealed that all personality traits were significantly associated with the quality of sibling relationships after controlling participant's gender and gender constellation. Of the personality traits, agreeableness was the strongest predictor of quality of sibling relationships. The current study's strengths and limitations and the implications future research are discussed.

Bigi Thomas

The size of the family influences the personality pattern both directly and indirectly. Directly, it determines what role the person will play in the family constellation, what kind of relationship he will have with other family members, and to a large extent, what opportunities he will have to make the most of his native abilities. Indirectly, family size influences the personality pattern through the kind of home climate fostered by families of different sizes and by the attitudes of the most significant members of the family toward the person. Another aspect of the connection between family size and personality is the amount of understanding and empathy found in families of different sizes. In a small family, parents have time to empathize with their children and to communicate with them. In a large family, there is less time, and also, as the number of children increases, the gap between the generations grows wider. This combination of conditions tends to lead to less warmth and...

The Open Family Studies Journal

Dr Hadas Doron

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences

Jude Wampah

Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR)

Intakhab A Khan