Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Collection 06 March 2024

Psychology Top 100 of 2023

This collection highlights the most downloaded* psychology research papers published by Scientific Reports in 2023. Featuring authors from around the world, these papers highlight valuable research from an international community.

You can also view the journal's overall Top 100 or the Top 100 within various subject areas . *Data obtained from SN Insights, which is based on Digital Science’s Dimensions.

Mild internet use is associated with epigenetic alterations of key neurotransmission genes in salivary DNA of young university students

- Eugenia Annunzi

- Loreta Cannito

- Claudio D’Addario

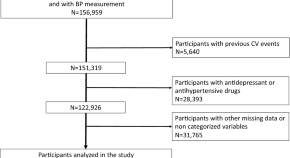

Association between cannabis use and blood pressure levels according to comorbidities and socioeconomic status

- Alexandre Vallée

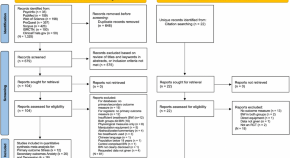

Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials

- Guy William Fincham

- Clara Strauss

- Kate Cavanagh

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder traits are a more important predictor of internalising problems than autistic traits

- Luca D. Hargitai

- Lucy A. Livingston

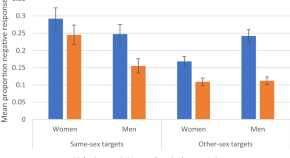

Married women with children experience greater intrasexual competition than their male counterparts

- Joyce F. Benenson

- Henry Markovits

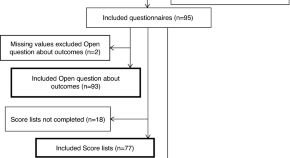

Treatment of 95 post-Covid patients with SSRIs

- Carla P. Rus

- Bert E. K. de Vries

- J. J. Sandra Kooij

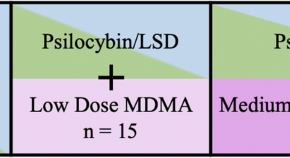

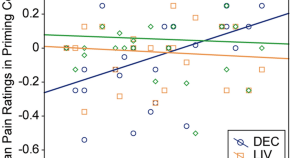

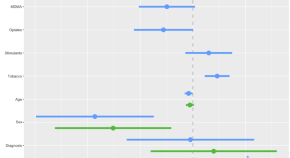

Co-use of MDMA with psilocybin/LSD may buffer against challenging experiences and enhance positive experiences

- Richard J. Zeifman

- Hannes Kettner

- Robin L. Carhart-Harris

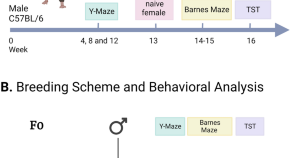

Learning and memory deficits produced by aspartame are heritable via the paternal lineage

- Sara K. Jones

- Deirdre M. McCarthy

- Pradeep G. Bhide

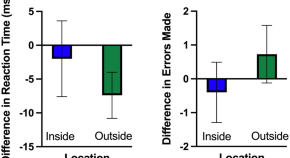

Exercising is good for the brain but exercising outside is potentially better

- Katherine Boere

- Kelsey Lloyd

- Olave E. Krigolson

Modulation of amygdala activity for emotional faces due to botulinum toxin type A injections that prevent frowning

- Shauna Stark

- Craig Stark

- Mitchell F. Brin

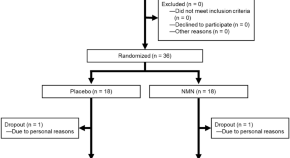

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolism and arterial stiffness after long-term nicotinamide mononucleotide supplementation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial

- Takeshi Katayoshi

- Sachi Uehata

- Kentaro Tsuji-Naito

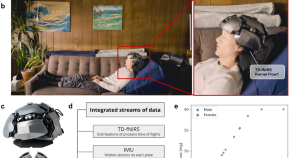

Measuring acute effects of subanesthetic ketamine on cerebrovascular hemodynamics in humans using TD-fNIRS

- Adelaida Castillo

- Julien Dubois

- Moriah Taylor

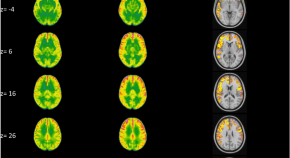

Cerebral hypoperfusion in post-COVID-19 cognitively impaired subjects revealed by arterial spin labeling MRI

- Miloš Ajčević

- Katerina Iscra

- Paolo Manganotti

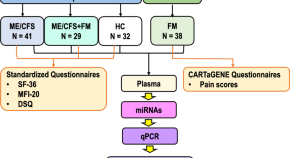

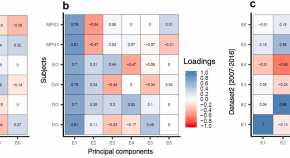

Circulating microRNA expression signatures accurately discriminate myalgic encephalomyelitis from fibromyalgia and comorbid conditions

- Evguenia Nepotchatykh

- Iurie Caraus

- Alain Moreau

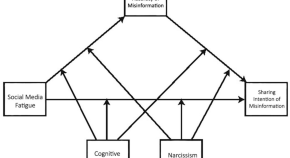

Examining the association between social media fatigue, cognitive ability, narcissism and misinformation sharing: cross-national evidence from eight countries

- Saifuddin Ahmed

- Muhammad Ehab Rasul

The illusion of the mind–body divide is attenuated in males

- Iris Berent

Genome-wide association study of school grades identifies genetic overlap between language ability, psychopathology and creativity

- Veera M. Rajagopal

- Andrea Ganna

- Ditte Demontis

Reverse effect of home-use binaural beats brain stimulation

- Michal Klichowski

- Andrzej Wicher

- Roman Golebiewski

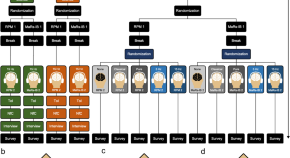

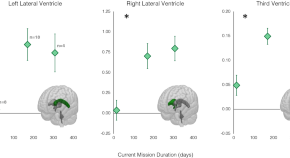

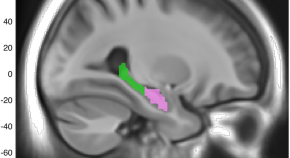

Impacts of spaceflight experience on human brain structure

- Heather R. McGregor

- Kathleen E. Hupfeld

- Rachael D. Seidler

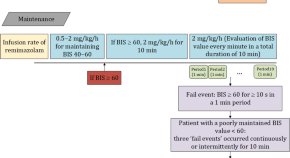

Frequency and characteristics of patients with bispectral index values of 60 or higher during the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia with remimazolam

- Byung-Moon Choi

- Ju-Seung Lee

- Gyu-Jeong Noh

Cognitive impairment in young adults with post COVID-19 syndrome

- Elena Herrera

- María del Carmen Pérez-Sánchez

- María González-Nosti

Giraffes make decisions based on statistical information

- Alvaro L. Caicoya

- Montserrat Colell

- Federica Amici

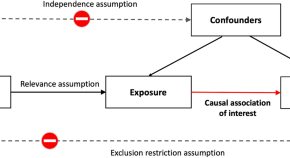

Genetic insights into the causal relationship between physical activity and cognitive functioning

- Boris Cheval

- Liza Darrous

- Matthieu P. Boisgontier

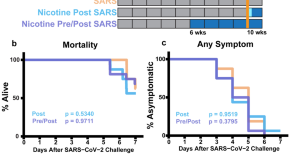

Nicotine exposure decreases likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 RNA expression and neuropathology in the hACE2 mouse brain but not moribundity

- Ayland C. Letsinger

- James M. Ward

- Jerrel L. Yakel

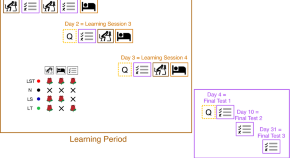

Presenting rose odor during learning, sleep and retrieval helps to improve memory consolidation: a real-life study

- Jessica Knötzele

- Dieter Riemann

- Jürgen Kornmeier

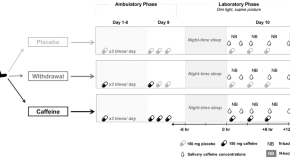

Brain activity during a working memory task after daily caffeine intake and caffeine withdrawal: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial

- Yu-Shiuan Lin

- Janine Weibel

- Carolin Franziska Reichert

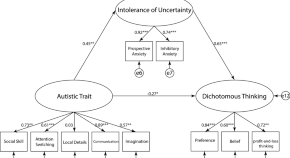

Autistic traits associated with dichotomic thinking mediated by intolerance of uncertainty

- Masahiro Hirai

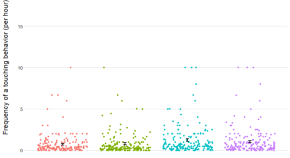

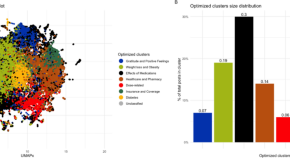

Love and affectionate touch toward romantic partners all over the world

- Agnieszka Sorokowska

- Marta Kowal

Semaglutide and Tirzepatide reduce alcohol consumption in individuals with obesity

- Fatima Quddos

- Zachary Hubshman

- Warren K. Bickel

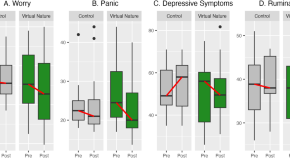

Daily exposure to virtual nature reduces symptoms of anxiety in college students

- Matthew H. E. M. Browning

- Seunguk Shin

- Wendy Heller

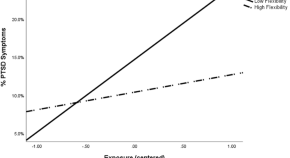

The role of cognitive flexibility in moderating the effect of school-related stress exposure

- Einat Levy-Gigi

Association of preexisting psychiatric disorders with post-COVID-19 prevalence: a cross-sectional study

- Mayumi Kataoka

- Megumi Hazumi

- Daisuke Nishi

Evaluating the complete (44-item), short (20-item) and ultra-short (10-item) versions of the Big Five Inventory (BFI) in the Brazilian population

- Raul Costa Mastrascusa

- Matheus Loli de Oliveira Fenili Antunes

- Tatiana Quarti Irigaray

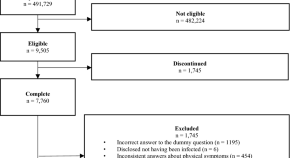

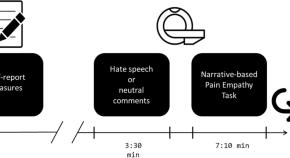

Exposure to hate speech deteriorates neurocognitive mechanisms of the ability to understand others’ pain

- Agnieszka Pluta

- Joanna Mazurek

- Michał Bilewicz

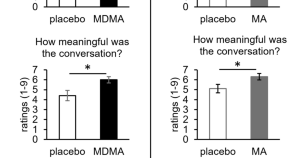

Drug-induced social connection: both MDMA and methamphetamine increase feelings of connectedness during controlled dyadic conversations

- Hanna Molla

- Harriet de Wit

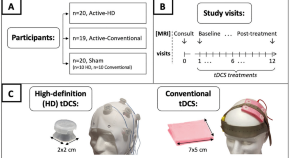

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in depression induces structural plasticity

- Mayank A Jog

- Cole Anderson

- Katherine Narr

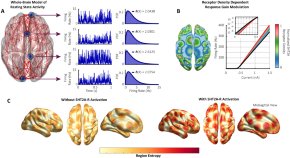

A whole-brain model of the neural entropy increase elicited by psychedelic drugs

- Rubén Herzog

- Pedro A. M. Mediano

- Rodrigo Cofre

Impact and centrality of attention dysregulation on cognition, anxiety, and low mood in adolescents

- Clark Roberts

- Barbara J. Sahakian

- Graham K. Murray

Change in brain asymmetry reflects level of acute alcohol intoxication and impacts on inhibitory control

- Ryan M. Field

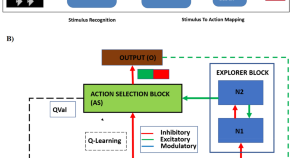

A generalized reinforcement learning based deep neural network agent model for diverse cognitive constructs

- Sandeep Sathyanandan Nair

- Vignayanandam Ravindernath Muddapu

- V. Srinivasa Chakravarthy

Exploring the role of empathy in prolonged grief reactions to bereavement

- Takuya Yoshiike

- Francesco Benedetti

- Kenichi Kuriyama

Children and adults rely on different heuristics for estimation of durations

- Sandra Stojić

- Vanja Topić

- Zoltan Nadasdy

Horses discriminate human body odors between fear and joy contexts in a habituation-discrimination protocol

- Plotine Jardat

- Alexandra Destrez

- Léa Lansade

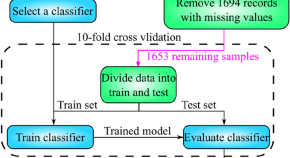

Prognosis prediction in traumatic brain injury patients using machine learning algorithms

- Hosseinali Khalili

- Maziyar Rismani

- U. Rajendra Acharya

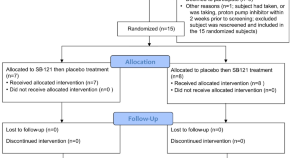

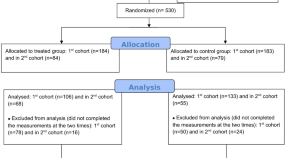

Results of a phase Ib study of SB-121, an investigational probiotic formulation, a randomized controlled trial in participants with autism spectrum disorder

- Lauren M. Schmitt

- Elizabeth G. Smith

- Craig A. Erickson

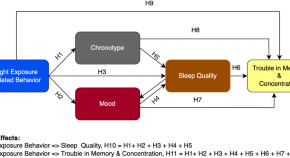

Light exposure behaviors predict mood, memory and sleep quality

- Mushfiqul Anwar Siraji

- Manuel Spitschan

- Shamsul Haque

Personality traits and dimensions of mental health

- Francois Steffens

- Antonio Malvaso

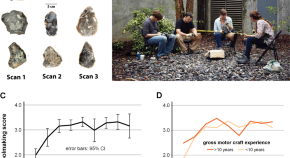

Neuroplasticity enables bio-cultural feedback in Paleolithic stone-tool making

- Erin Elisabeth Hecht

- Justin Pargeter

- Dietrich Stout

APOE ɛ4, but not polygenic Alzheimer’s disease risk, is related to longitudinal decrease in hippocampal brain activity in non-demented individuals

- Sofia Håglin

- Karolina Kauppi

Exploring regional aspects of 3D facial variation within European individuals

- Franziska Wilke

- Noah Herrick

- Susan Walsh

Personality traits and decision-making styles among obstetricians and gynecologists managing childbirth emergencies

- Gabriel Raoust

- Petri Kajonius

- Stefan Hansson

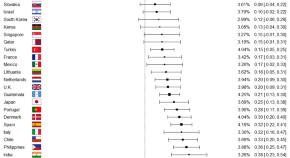

Greater traditionalism predicts COVID-19 precautionary behaviors across 27 societies

- Theodore Samore

- Daniel M. T. Fessler

- Xiao-Tian Wang

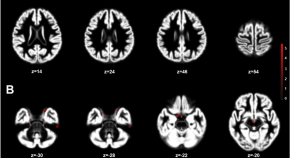

Gray matter differences associated with menopausal hormone therapy in menopausal women: a DARTEL-based VBM study

- Tae-Hoon Kim

- ByoungRyun Kim

- Young Hwan Lee

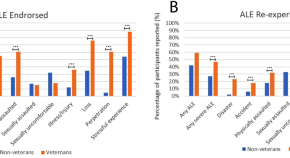

Prevalence and therapeutic impact of adverse life event reexperiencing under ceremonial ayahuasca

- Brandon Weiss

- Aleksandra Wingert

- W. Keith Campbell

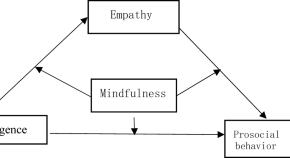

Mindfulness may be associated with less prosocial engagement among high intelligence individuals

Proteomic association with age-dependent sex differences in Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance in healthy Thai subjects

- Bupachad Khanthiyong

- Sutisa Nudmamud-Thanoi

Contribution of sustained attention abilities to real-world academic skills in children

- Courtney L. Gallen

- Simon Schaerlaeken

- Adam Gazzaley

Synchrony to a beat predicts synchrony with other minds

- Sophie Wohltjen

- Brigitta Toth

- Thalia Wheatley

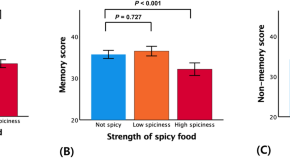

Spicy food intake predicts Alzheimer-related cognitive decline in older adults with low physical activity

- Jaeuk Hwang

- Young Min Choe

- Jee Wook Kim

Academic burnout among master and doctoral students during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Diego Andrade

- Icaro J. S. Ribeiro

- Orsolya Máté

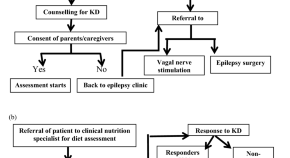

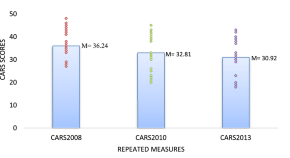

Ketogenic diet for epilepsy control and enhancement in adaptive behavior

- Omnia Fathy El-Rashidy

- May Fouad Nassar

- Yasmin Gamal Abdou El Gendy

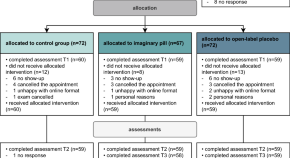

Imaginary pills and open-label placebos can reduce test anxiety by means of placebo mechanisms

- Sarah Buergler

- Dilan Sezer

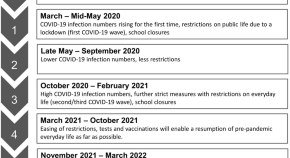

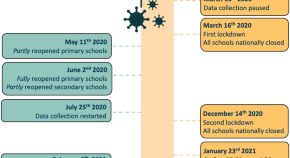

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people with and without pre-existing mental health problems

- Ronja Kleine

- Artur Galimov

- Julia Hansen

Dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis and its influence on aging: the role of the hypothalamus

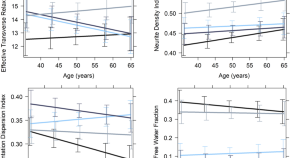

- Melanie Spindler

- Marco Palombo

- Christiane M. Thiel

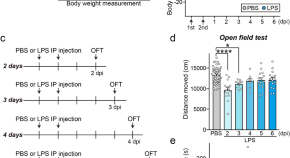

LPS induces microglial activation and GABAergic synaptic deficits in the hippocampus accompanied by prolonged cognitive impairment

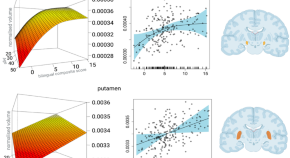

Dynamic effects of bilingualism on brain structure map onto general principles of experience-based neuroplasticity

- J. Treffers-Daller

- C. Pliatsikas

Alternative beliefs in psychedelic drug users

- Alexander V. Lebedev

- Predrag Petrovic

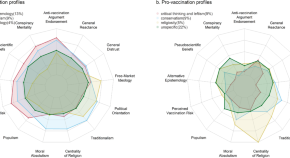

Psychological profiles of anti-vaccination argument endorsement

- Dawn L. Holford

- Angelo Fasce

- Stephan Lewandowsky

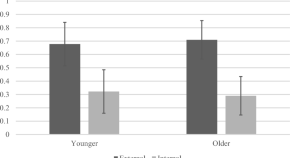

Memory compensation strategies in everyday life: similarities and differences between younger and older adults

- Madeleine J. Radnan

- Riley Nicholson

- Celia B. Harris

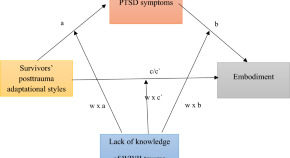

Long-lasting effects of World War II trauma on PTSD symptoms and embodiment levels in a national sample of Poles

- Marcin Rzeszutek

- Małgorzata Dragan

- Szymon Szumiał

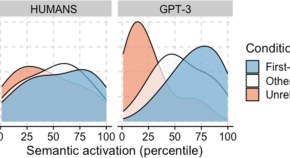

Overlap in meaning is a stronger predictor of semantic activation in GPT-3 than in humans

- Jan Digutsch

- Michal Kosinski

Poorer sleep impairs brain health at midlife

- Tergel Namsrai

- Ananthan Ambikairajah

- Nicolas Cherbuin

Screen time, impulsivity, neuropsychological functions and their relationship to growth in adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms

- Jasmina Wallace

- Elroy Boers

- Patricia Conrod

Linguistic identity as a modulator of gaze cueing of attention

- Anna Lorenzoni

- Giulia Calignano

- Eduardo Navarrete

Serum ferritin level during hospitalization is associated with Brain Fog after COVID-19

- Teruyuki Ishikura

- Tomohito Nakano

- Takashi Naka

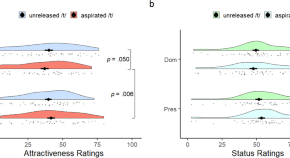

Articulatory effects on perceptions of men’s status and attractiveness

- Sethu Karthikeyan

- David A. Puts

- Glenn Geher

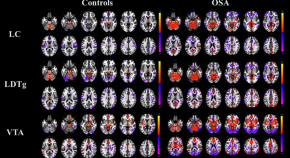

Altered functional connectivity of the ascending reticular activating system in obstructive sleep apnea

- Jung-Ick Byun

- Geon-Ho Jahng

- Won Chul Shin

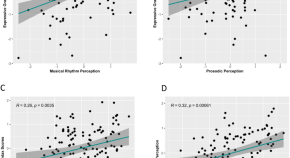

Exploring individual differences in musical rhythm and grammar skills in school-aged children with typically developing language

- Rachana Nitin

- Daniel E. Gustavson

- Reyna L. Gordon

Experiencing sweet taste is associated with an increase in prosocial behavior

- Michael Schaefer

- Anja Kühnel

- Matti Gärtner

Hypnotic suggestions cognitively penetrate tactile perception through top-down modulation of semantic contents

- Marius Markmann

- Melanie Lenz

- Albert Newen

Long-term high-fat diet increases glymphatic activity in the hypothalamus in mice

- Christine Delle

- Neža Cankar

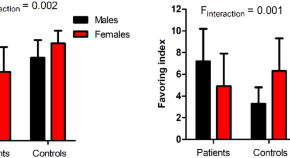

Emotional face expression recognition in problematic Internet use and excessive smartphone use: task-based fMRI study

- Szilvia Anett Nagy

- Gergely Darnai

Conflict experience and resolution underlying obedience to authority

- Felix J. Götz

- Vanessa Mitschke

- Andreas B. Eder

Comparative efficacy of onsite, digital, and other settings for cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis

- Laura Simon

- Lisa Steinmetz

- Harald Baumeister

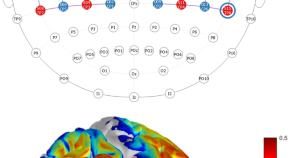

Simultaneous multimodal fNIRS-EEG recordings reveal new insights in neural activity during motor execution, observation, and imagery

- Wan-Chun Su

- Hadis Dashtestani

- Amir Gandjbakhche

Facial emotion recognition in patients with depression compared to healthy controls when using human avatars

- Marta Monferrer

- Arturo S. García

- Patricia Fernández-Sotos

Evidence that the aesthetic preference for Hogarth’s Line of Beauty is an evolutionary by-product

- Ronald Hübner

- David M. G. Lewis

- Jonathon Flores

Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on structural brain development in early adolescence

- L. van Drunen

- Y. J. Toenders

- E. A. Crone

Improving stress management, anxiety, and mental well-being in medical students through an online Mindfulness-Based Intervention: a randomized study

- Teresa Fazia

- Francesco Bubbico

- Luisa Bernardinelli

Sex-related differences in parental rearing patterns in young adults with bipolar disorder

- Huifang Zhao

- Xujing Zhang

- Fengchun Wu

A follow-up study of early intensive behavioral intervention program for children with Autism in Syria

- Wissam Mounzer

- Donald M. Stenhoff

- Amal J. Al Khatib

Dog owner mental health is associated with dog behavioural problems, dog care and dog-facilitated social interaction: a prospective cohort study

- Ana Maria Barcelos

- Niko Kargas

- Daniel S. Mills

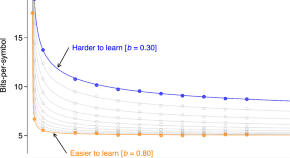

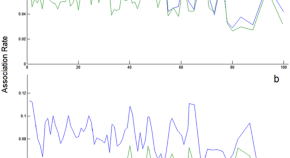

Languages with more speakers tend to be harder to (machine-)learn

- Alexander Koplenig

- Sascha Wolfer

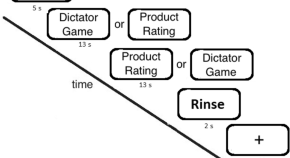

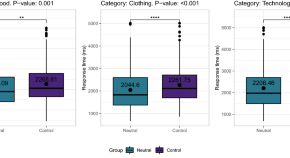

How priming with body odors affects decision speeds in consumer behavior

- Mariano Alcañiz

- Irene Alice Chicchi Giglioli

- Gün R. Semin

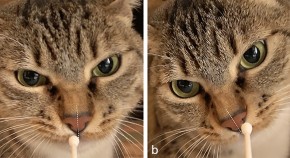

Relationship between asymmetric nostril use and human emotional odours in cats

- Serenella d’Ingeo

- Marcello Siniscalchi

- Angelo Quaranta

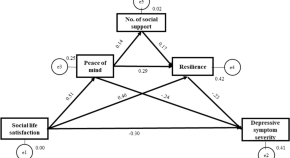

Social support enhances the mediating effect of psychological resilience on the relationship between life satisfaction and depressive symptom severity

- Yun-Hsuan Chang

- Cheng-Ta Yang

- Shulan Hsieh

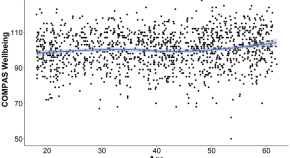

Predicting wellbeing over one year using sociodemographic factors, personality, health behaviours, cognition, and life events

- Miranda R. Chilver

- Elyse Champaigne-Klassen

- Justine M. Gatt

Multimodal assessment of the spatial correspondence between fNIRS and fMRI hemodynamic responses in motor tasks

- João Pereira

- Bruno Direito

- Teresa Sousa

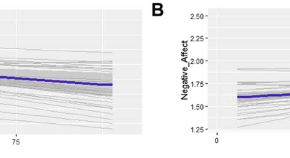

Childhood maltreatment and emotion regulation in everyday life: an experience sampling study

- Mirela I. Bîlc

- Andrei C. Miu

Individual personality predicts social network assemblages in a colonial bird

- Fionnuala R. McCully

- Paul E. Rose

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Future of Psychology: Connecting Mind to Brain

Lisa feldman barrett.

Boston College, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard Medical School

Psychological states such as thoughts and feelings are real. Brain states are real. The problem is that the two are not real in the same way, creating the mind–brain correspondence problem. In this article, I present a possible solution to this problem that involves two suggestions. First, complex psychological states such as emotion and cognition an be thought of as constructed events that can be causally reduced to a set of more basic, psychologically primitive ingredients that are more clearly respected by the brain. Second, complex psychological categories like emotion and cognition are the phenomena that require explanation in psychology, and, therefore, they cannot be abandoned by science. Describing the content and structure of these categories is a necessary and valuable scientific activity.

Physical concepts are free creations of the human mind, and are not, however it may seem, uniquely determined by the external world. — Einstein & Infeld (1938 , p. 33)

The cardinal passions of our life, anger, love, fear, hate, hope, and the most comprehensive divisions of our intellectual activity, to remember, expect, think, know, dream (and he goes on to say, feel) are the only facts of a subjective order… — James (1890 , p. 195)

From its inception in the early 18th century (as an amalgam of philosophy, neurology, and physiology), psychology has always been in a bit of an identity crisis, trying to be both a social and a natural science. 1 Psychologists attempt bridge the social and natural worlds using the conceptual tools of their time. Throughout our history, the link between the social (mind and behavior) and the natural (brain) has felt less like a solid footbridge and more like a tightrope requiring lightness of foot and a really strong safety net. Mind–brain, and relatedly, behavior–brain, correspondence continue to be central issues in psychology, and they remain the largest challenge in 21st century psychology.

The difficulty in linking the human mind and behavior on the one hand and the brain on the other is rooted, ironically enough, in the way the human brain itself works. Human brains categorize continuously, effortlessly, and relentlessly. Categorization plays a fundamental role in every human activity, including science. Categorizing functions like a chisel, dividing up the sensory world into figure and ground, leading us to attend to certain features and to ignore others. Via the process of categorization, the brain transforms only some sensory stimulation into information. Only some of the wavelengths of light striking our retinas are transformed into seen objects, and only some of the changes in air pressure registered in our ears are heard as words or music. To categorize something is to render it meaningful. It then becomes possible to make reasonable inferences about that thing, to predict what to do with it, and to communicate our experience of it to others. There are ongoing debates about how categorization works, but the fact that it works is not in question.

The brain’s compulsion to categorize presents certain unavoidable challenges to what can be learned about the natural world from human observation. Psychologists know that people don’t contribute to their perceptions of the world in a neutral way. Human brains do not dispassionately look on the world and carve nature at its joints. We make self-interested observations about the world in all manner of speaking. And what holds true for people in general certainly holds for scientists in particular. Scientists are active perceivers, and like all perceivers, we see the world from a particular point of view (which is not always shared by other scientists). We parse the world into bits and pieces using the conceptual tools that are available at a particular point in time and with a particular goal in mind (which is often inextricably linked to said conceptual tools). This is not a failing of the scientific method per se—it is a natural consequence of how the human brain sees and hears and feels … and does science.

An example of how categorization shapes science comes from the study of genetics. When molecular biologists first began to study the units of inheritance, they (inspired by Mendel) searched for and found genes : bits of DNA that make the proteins needed to constitute the human body. Yet, only a small proportion of human DNA (somewhere between 2% to 5%, depending on which paper you read) are genes; the rest of the stuff (that does not directly produce proteins) was labeled “junk” on the assumption that it was largely irrelevant to the biological understanding of life. As it turns out, however, “junk DNA” has some rather important functions, including regulating gene expression (i.e., turning on and off protein production) in a contextually sensitive fashion (for a generally accessible review, see Gibbs, 2003 ). Scientists have discovered that much of what makes us human and makes one person different from another lurks in this junk. The result has been nothing short of a revolution in molecular genetics. Genes do not, in and of themselves, provide a sufficient recipe for life. The unit of selection is not the gene, but the individual, who, for the purposes of molecular genetics, can be thought of as a bundle of genes that are turned on and off by the rest of our DNA, which serves to regulate the epigenetic context. And, the more they learned about junk DNA, the more scientists realized that it is not so easy to define what is a gene and what is not. Some molecular geneticists now try to avoid the word “gene” altogether. Instead they use the more mechanistic term transcriptional unit .

In this article, I argue that perhaps psychology needs to reconsider its vocabulary of categories. Like any young science, psychology has been practicing a very sophisticated form of phenomenology, observing the psychological world using categories derived from our own experiences. We then use common sense words to name these categories, leading us to reify them as entities. We then search for the counterparts of these categories within the brain. These two practices—carving and naming—have a far-reaching consequence: Psychology may more or less accept the Kantian idea that the knowledge stored in a human brain contributes to thoughts, feelings, memories, and perceptions in a top-down fashion, but at the same time we accept without question that emotions, thoughts, memories, the self, and the other psychological categories in folk psychology reflect the basic building blocks of the mind. We do this in much the same way that Aristotle assumed that fire, earth, air, and water were the basic elements of the material universe; as if the categories themselves are not constructed out of something else more basic. In our causal explanations, psychologists talk about psychological facts as if they are physical facts.

But what if psychological facts are not physical facts? What if the phenomena we want to explain—emotions, cognitions, the self, behaviors—are not just the subject matter of the human mind, but are also the creations of that mind? What if the boundaries for these categories are not respected in the very brain that creates them?

Such a state of things might lead some scientists to conclude that psychological categories are not real, or that psychology as a science can be dispensed with. That all scientists need to do is understand the brain. But nothing can be further from the truth. The main point I make in this article is that, in psychology, we simultaneously take our phenomenology too seriously and not seriously enough: too seriously when trying to understand how the mind corresponds to the brain and not seriously enough when we want to understand psychological phenomena as real and scientifically valuable, even in the face of spectacular and unrelenting progress in neuroscience. Changing this state of affairs is a central task for the future.

THE METAPHYSICS OF WHAT EXISTS

Scientific ontology.

The vocabulary of categories in any field of science segregates the phenomena to be explained and in so doing makes them real. Yet not all categories are real in the same way.

Natural sciences like physics deal with scientific categories that are assumed to be observer independent (they are real in the natural sense and can be discovered by humans). These kinds of categories function like an archeologist’s chisel we need a mind to discover and experience instances of these categories, but they do not depend on our minds for their existence. In 2007, I discovered that philosopher John Searle (in writing about social institutions and social power; Searle, 1995 ) called these ontologically objective categories or “brute facts.” They are also called natural kind categories. At times, human experience can lull scientists into using the wrong categories at first (e.g., genes and junk DNA), but the phenomena themselves (e.g., DNA, RNA, proteins, and so on) exist outside of human experience and can have a corrective influence on which categories are used. Here, the presumption is that the scientific method takes us on what can seem like a long, slow, carnival ride toward discovering and explaining the material world.

Social sciences like sociology or economics deal with categories that are observer-dependent (and are real because they are invented and shared by humans). Observer dependent categories function like a sculptor’s chisel—they constitute what is real and what is not. Humans create observer-dependent categories to serve some function. Their validity, and their very existence, in fact, comes from consensual agreement. Little pieces of paper have value to procure goods not because of their molecular structure, but because we all agree that they do, and they would cease to have value if many people changed their mind (and refused to accept the paper in lieu of material goods). Only certain types of pair bonds between humans are defined as “marriages” and confer real social and monetary benefits. People are citizens of the same country (e.g., Canada, Yugoslavia, or the Soviet Union) only as long as they all agree that the country exists and this membership becomes part of a person’s identity and often confers social and economic advantage. 2 Searle calls these ontologically subjective categories because they exist only by virtue of collective intentionality (which is a fancy way of saying that they are real by virtue of the fact that everybody largely agrees on their content). We might also think of them as nominal kind categories, 3 as artifact categories, or as cognitive tools for getting along and getting ahead.

Psychology, in walking a tightrope between the social world and the natural world, tries to map observer dependent categories to observer independent categories. The trick, of course, is to be clear about which is which and to never mistake one for the other. Once psychology more successfully distinguishes between the two, I predict that we will be left with the more tractable but never simple task of understanding how to map mind and behavior to the human brain.

Beginning in 1992, I began to craft the position that emotion categories labeled as anger and sadness and fear are mistakenly assumed to be observer independent, when in fact they are dependent on human (particularly Western) perceivers for their existence. I published the first sketch of these ideas about a decade later ( Barrett, 2005 , 2006b ), spurred on by my discovery of the emotion paradox : In the blink of an eye, perceivers experience anger or sadness or fear and see these emotions in other people (and in animals, or even simple moving shapes) as effortlessly as they read words on a page, 4 yet perceiver-independent measurements of faces, voices, bodies, and brains do not clearly and consistently reveal evidence of these categories ( Barrett, 2006a ; Barrett & Wager, 2006 ; also see Barrett, Lindquist, et al., 2007 ). Some studies of cardiovascular measurements, electromyographic activity of facial muscles, acoustical analyses of vocal cues, and blood-flow changes within the brain are consistent with the traditional idea that emotions are observer-independent categories, but the larger body of evidence disconfirms their status as ontologically objective entities. There is not a complete absence of statistical regularities across these measures during the events that we name as the same emotion, but the variability across different categories is not dramatically larger than the variance observed within any single category.

One solution to the emotion paradox suggests that anger , sadness , fear , and so on are observer-dependent psychological categories and that instances of these emotions live in the head of the perceiver ( Barrett, 2006b ). This is not to say that emotions like anger exist only in the head of the perceiver. Rather, it is more correct to say that they cannot exist without a perceiver. I experience myself as angry or I see your face as angry or I experience the rat’s behavior as angry, but anger does not exist independent of someone’s perception of it. Without a perceiver, there are only internal sensations and a stream of physical actions.

In 2007, based largely on neuroanatomical grounds, I extended this line of reasoning, arguing that the categories labeled as emotion and cognition are not ontologically objective categories ( Duncan & Barrett, 2007 ; for a similar view, see Pessoa, 2008 ). Thinking (e.g., sensing and categorizing an object, or deliberating on an object) feels like a fundamentally different sort of mental activity than feeling (i.e., representing how the object influences one’s internal state). As a result, psychologists have believed for some time that cognitions and emotions are separate and distinctive processes in the mind that interact like the bit and parts of a machine. But the brain does not really respect these categories, and thus mental states cannot be said to be categorically one or the other. Nor can behavior be caused by their interaction.

In this article, I am extending this reasoning even further by proposing that many—perhaps even the majority—of the categories with modern psychological currency are like money, marriage, nationality, or any of the observer-dependent categories that Searle writes about. The complex psychological categories we refer to by the words thoughts , memories , emotions , and beliefs , or automatic processing , controlled processing , or the self , and so on, are observer dependent. They are collections of mental states that are products of the brain, but they do not correspond to brain organization in a one-to-one fashion. These categories exist because a group of people agreed (for phenomenological and social reasons) that this is a functional way to parse the ongoing mental activity that is realized in the brain. Some of the categories are cross-culturally stable (because they function to address certain universal human concerns that stem from living in large, complex groups), whereas others are culturally relative. The distinction between categories like emotion and cognition , for example, is relative and can vary with cultural context (e.g., Wikan, 1990 ), thus calling into question the fact that they are universal, observer-independent categories of the mind.

Even the most basic categories in psychology appear to be observer dependent. Take, for example, behaviors (which are intentional, bounded events) and actions (which are descriptions of physical movements). We easily and effortlessly see behaviors in people and in nonhuman animals. We typically believe that behaviors exist and are there to be detected, but not created, by the human brain. But this is not quite true. Behaviors are actions with a meaning that is inferred by an observer. Social psychology has accumulated a large and nuanced body of research on how people come to see the physical actions of others as meaningful behaviors by inferring the causes for those actions (usually by imputing an intention to the actor; for a review, see Gilbert, 1998). People and animals are constantly moving and doing things—that is, they are constantly engaging in a flow of actions. A perceiver automatically and effortlessly partitions continuous movements into recognizable, meaningful, discrete behavioral acts using category knowledge about people and animals ( Vallacher & Wegner, 1987 ). In emotion research, a rat that kicks up bedding at a threatening creature is said to be defensive treading or in a state of fear . Similarly, standing still in a small spare box in response to a tone that all of the sudden predicts an electric shock can be described as freezing or it can be called fear . It can also be called a state of vigilance — an alert, behavioral stance that allows an organism to martial all its attentional and sensory resources to quickly learn more about a stimulus when its predictive value is uncertain (cf. Barrett, Lindquist, et al., 2007 ). Depending on the category used, intention is inferred to different degrees as part of the categorization of the action into a behavior. The same point can be made about situations. Physical surroundings exist separately from observers, but situations do not.

A similar point can even be made about what are typically assumed to be the observer-independent phenomena measured during functional magnetic resonance functional imaging. Areas of the brain that show increased activity during memory, perception, or emotion (or whatever the researcher is interested in measuring) are assumed to reflect changes in blood flow caused by neuronal firing at those locations. But just as behavioral scientists separate the variance in a measured behavior into effect (i.e., the measured variance of interest) and error (i.e., the measured variance that is not of interest), so do cognitive neuroscientists routinely separate in blood oxygen level dependent changes into signal (the strong changes that they believe to be task dependent) and noise (the weaker changes that they don’t care about). This separation is guided by the neuropsychological assumption that psychological functions are localized to modules in particular brain areas, like islands on a topographical map, because lesions in particular areas appear to disrupt specific psychological functions. In recent years, however, it has become clear (using multivariate voxel pattern analysis procedures) that noise carries meaningful psychological information (e.g., Haynes & Rees, 2006 ; Kay, Naselaris, Prenger, & Gallant, 2008 ; Norman, Polyn, Detre, & Haxby, 2006 ), just as junk DNA is not junk at all. This turn of events makes brain mapping less like cartography (mapping stationary masses of land) and more like meteorology (mapping changing weather patterns or “brainstorms”).

Let me be clear about what I am saying here—it is a brute fact that the brain contains neurons that fire to create mental states or cause behavior and this occurs independent of human experience and measurement. It is not a brute fact, however, that this neuronal activity can be easily classified as automatic processing or controlled processing ; that some “islands” in the brain realize cognitions whereas others realize emotion ; or even that the self , or goals , or memories live in specific parts of the brain (whether in a local or distributed specific, unchanging network). We use categories to separate ongoing mental activity into discrete mental states (such as, in this culture, anger, an attitude, a memory, or self-esteem), to classify a stream of physical movements into behaviors (such as lying, stealing, or joking), or to classify parts of the physical surroundings as situations. These categories come from and constitute human experience. The category instances are real, but they derive their reality from the human mind (in the context of other human minds). Mental activity is classified this way for reasons having to do with collective intentionality, communication, and even self-regulation, but not because this is the best way to understand how the brain mechanistically creates the mind and behavior. Emotion and cognition make up the Western psychological and social reality, and they must be explained by the brute fact of how the human brain works, but emotion and cognition are not mechanisms that are necessarily respected by the human brain or categories that are required by the human brain. Brain states are observer-independent facts. The existence of mental states is also an observer-independent fact. Cognitions, emotions, memories, self-esteem, beliefs, and so on are not observer-dependent events, however. They are categories that have been formed and named by the human mind to represent and explain the human mind.

What’s In a Name?

Words are powerful in science. When dealing with observer-independent categories, words set the ground rules for what to look for in the world. To the extent that scientists understand and use the word in a similar way, they agree on what to search for. They assume, for the moment, that genetic material really is segregated into genes and junk, and they then go about searching for the deep properties that ground these categories in the material world, with the hope either that they are right or that their observations will lead them to formulate better, more accurate categories. When dealing with observer-dependent categories that populate psychology, words are ontologically powerful. They set the ground rules for what exists.

Words can also be dangerous. They present scientists with a Faustian bargain. We need words to do the work of science, but the words lead us to mistake observer-dependent categories (or nominal kinds) for observer-independent categories (or natural kinds). By naming both defensive treading and freezing as fear , for example, scientists are lulled into thinking these behaviors share a deep property, and they will spend years searching for it, even when it may not exist. This is because a word doesn’t only name a category, it also encourages a very basic form of essentialism that Paul Bloom (2004) argues is already present in how people think about the events and objects in their everyday lives. A word functions like an “essence placeholder” that encourages people to engage in psychological essentialism—it convinces the perceiver that there is some deep reality to the category in the material world ( Medin & Ortony, 1989 ; this is true even in young children, e.g., Xu, Cote, & Baker, 2005 ). William James (1890) described the danger of referring to psychological categories with words when he wrote “Whenever we have made a word…to denote a certain group of phenomena, we are prone to suppose a substantive entity existing beyond the phenomena, of which the word shall be the name” (p. 195). In psychology’s active and ongoing attempt to knit the social and natural worlds together into one seamless universe, words cause us to take phenomenology inspired categories—Western categories no less—and search for years (often in vain) for the specific brain areas, genes, hormones, or some other biological product that they correspond to. Then we end up arguing about whether the amygdala is the brain locus of fear, whether dopamine is the hormone for reward, or whether the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) is the cause of depression.

FORWARD INTO THE PAST

Thus far, I have suggested that psychology is populated by a set of observer-dependent categories that do not directly correspond (in a one-to-one fashion) to the observer-independent facts of neurons firing in the brain. If this claim is true, then psychology’s current vocabulary of phenomenologically grounded categories won’t interface very well with neuroscience to effectively weave social and natural sciences together into one cozy blanket and solve the problem of mind–brain (or behavior–brain) correspondence. Psychology may need a different set of psychological categories—categories that more closely describe the brain’s activities in creating the mind and causing behavior. That being said, if emotion, cognition, memory, the self, and so on, exist— they are real by virtue of the fact that everyone within a culture experiences them, talks about them, uses them as reasons for actions then they cannot be discarded or ontologically reduced to (or merely redefined as nothing but) neurons firing. Psychology must explain the existence of cognition and emotion because they are part of the world that we (in the Western hemisphere) live in (even if it is a part that we, ourselves, created). 5 Can psychology both describe what emotions and cognitions (or whatever the mental categories within a given cultural context) are and also explain how they are caused? I think the answer is yes. And as with most things psychological, the answer begins with William James.

Over a century ago, William James wrote about the psychologist’s fallacy. “The great snare of the psychologist,” James wrote, “is the confusion of his own standpoint with that of the mental fact about which he is making his report.” ( James, 1890 , p. 196). This is pretty much the same thing as saying that psychologists confuse observer-dependent (or ontologically subjective) distinctions with observer-independent (or ontologically objective) ones. The solution to the psychologist’s fallacy, according to James, is to take a psychological constructionist approach. “A science of the relations of mind and brain” James wrote, “must show how the elementary ingredients of the former correspond to the elementary functions of the latter.” ( James, 1890 , p. 28).

Psychological constructionist models of the mind were developed in early years of psychology and have appeared consistently throughout the history of our science, although they have tended not to dominate (for a review, see Gendron & Barrett, in press ). They are grounded in the assumption that experienced psychological states are not the elemental units of the mind or the brain, just as fire, water, air, and earth are not the basic elements of the universe. Instead, they are products that emerge from the interplay of more basic, all-purpose components. The importance of distinguishing between the function of a mechanism (or process) and the products that it creates (what the functions are in the service of or what they allow to emerge) is inherent to a psychological constructionist approach. The contents of a psychological state reveal nothing about the processes that realize it in much the same way that a loaf of bread does not reveal the ingredients that constitute it.

A RECIPE FOR PSYCHOLOGY IN THE 21ST CENTURY

The modern constructionist approach that I envision for psychology in the 21st century is grounded in a simple observation. Every moment of waking life our brain realizes mental states and actions by combining three sources of stimulation: sensory stimulation made available by and captured from the world outside the skin (the exteroceptive sensory array of light, vibrations, chemicals, etc.), sensory signals captured from within the body that holds your brain (somatovisceral stimulation, also called the interoceptive sensory array or the internal milieu ), and prior experience that the brain makes available by the reactivation and reinhibition of sensory and motor neurons (i.e., cognition). These three sources—sensations from the world, sensations from the body, and prior experience—are continually available, and they form the three fundamental aspects of all mental life. Different recipes (combinations and weights of these three ingredients) produce the myriad of mental events that constitute the mind. Depending on the focus of attention and proclivities of the scientist, this stream of brain activity is parsed into discrete psychological moments that we call by different names: “feeling,” “thinking,” “remembering,” or even “seeing.” Each view is right in its own way.

When the focus is trying to understand what externally driven sensations refer to in the world, mental activity is called perception . Researchers who are interested in understanding perception (“What is the object?”) and behavior (“How do I act on it?”) might ask how sensory stimulation from the body and prior experience with an external sensory array are required to keep track of and impart meaning to that sensory stimulation. Said another way, scientists are asking how the brain makes predictions about what the meaning of the current sensory array from the world ( Barrett & Bar, 2009 ), allowing us to know our relation to the immediate surroundings in a moment-to-moment way and act accordingly.

When the focus is trying to understand how prior experiences are reinstated in the brain, mental activity is called cognition . When a person experiences the act of remembering, this mental activity is called memory . When they do not, it is called thinking . When the mental activity refers to the future, it is called imagining . And this mental activity provides a sense of self that continues through time. Researchers who are interested in understanding cognition (“How is the past reconstituted?”) typically ask how prior instances of sensory stimulation from the world, and from the body, are encoded and associatively recombined or reinstated for future use.

When the focus is trying to understand what internal sensations from the body stand for, the mental activity is called emotion . Researchers who are interested in understanding emotion experience (“How do I feel?”) examine how sensory information from the world and conceptual knowledge about emotion together create a context for what internal bodily sensations stand for in psychological terms. 6 Together, these three sources of input create the mental states named with emotion words. These conceptualized states are the mental tools that the human brain uses to regulate itself and the body’s internal state either directly or by acting on the world. This last piece is essentially a restatement of the model of emotion that I proposed in Barrett (2006b) .

This very general description of mental life can be developed into a psychological constructionist approach that consists of five principles: (a) the mind is realized by the continual interplay of more basic primitives that can be described in psychological terms; (b) all mental states (however categorized) can be causally reduced to these more basic psychological primitives; (c) these basic psychological primitives correspond closely to distributed networks in the brain; (d) the mind is more like a set of recipes than like a machine; and (e) mental events are probabilistically, not mechanistically, causal.

Principle 1: Psychological Primitives

The basic processes that constitute complex psychological categories can be described as psychologically primitive (to borrow a phrase from Ortony & Turner, 1990 ), meaning that they are psychologically irreducible and cannot be redescribed as anything else psychological. These “ psychological primitives ” are the ingredients in a recipe that will produce an instance of a complex psychological state—what we call an emotion, or memory, or thought, and so on—although they are not specific to any one state (see Fig. 1 ). Unlike the culturally relative complex psychological categories that they realize, psychological primitives are universal to all human beings. (This is not the same as proposing that there are broad, general laws for psychology or for domains of psychology like emotion or memory.) It might be possible to describe the operations that the brain is performing to create psychological primitives, but these operations would be identified in terms of the psychological primitives that they constitute.

Depictions of three brain states comprised of different combinations of the same three psychological primitives (represented in yellow, pink, and blue). Depending on the recipe (the combination and relative weighting of psychological primitives in a given instance) and a psychologist’s interest and theoretical proclivities, mental states are called seeing or thinking or feeling .

Although identifying specific psychological primitives is beyond the scope of this article, elsewhere, my lab and I nominated three phenomena as psychological primitives. One psychological primitive may be what has been termed valuation, salience, or affect (producing a change in a person’s internal physical state that can be consciously experienced as pleasant or unpleasant, and arousing to some degree). Another may be categorization (determining what something is, why it is, and what to do about it). And a third may be a matrix consisting of different sources of attention (where attention is defined as anything that can change the rate of neuronal firing; for discussion, see Barrett, 2006b ; Barrett, Tugade, & Engle, 2004 ; Duncan & Barrett, 2007 ). 7 And of course there are others.

Principle 2: An Ontology of Levels, Not Kinds

Complex psychological categories refer to the contents of the mind (representations) that can be redescribed as the psychological primitives that are themselves the products of neuronal firing. What psychology needs in the 21st century is a toolbox filled with categories for representing both the products and the processes at the various levels. Like David Marr’s (1982) famous computational framework for vision (which has been oft-discussed in mind—brain correspondence; e.g., Mitchell, 2006 ; Ochsner & Lieberman, 2001 ), the categories at each level of the scientific ontology capture something different from what their component parts capture, and each must be described in its own terms and with its own vocabulary. Unlike Marr’s framework, as well as other recent treatments of mind brain correspondence that explicitly discuss the need for a multilevel approach, it is assumed here that each level of the ontology must stand in relation to (and help set the boundaries for) the other levels. That is, there must be an explicit accounting of how categories at each level relate to one another. 8 One such ontology of categories to describe mind brain correspondence is suggested in Table 1 and is discussed as Principle 3.

Mind–Brain Correspondence

Principle 3: Networks, Not Locations

At the top of the ontology, complex psychological categories, such as anger, correspond to a collection of brain states that can be summarized as a broadly distributed neural reference space . A neural reference space, according to neuroscientist Gerald Edelman, refers to the neuronal workspace that implements the brain states that correspond to a class of mental events. A specific instance of a category (e.g., a specific instance of anger) corresponds to a brain state within this neural reference space. The individual brain states transcend anatomical boundaries and are coded as a flexible, distributed assembly of neurons. For example, the brain states corresponding to two different instances of anger may not be stable across people or even within a person over time.

Each mental state can be redescribed as a combination of psychological primitives. In this ontology, psychological primitives are functional abstractions for brain networks that contribute to the formation of neuronal assemblies that make up each brain state. They are psychologically based, network-level descriptions. 9 These networks are distributed across brain areas. They are not necessarily segregated (meaning that they can partially overlap). Each network exists within a context of connections to other networks, all of which run in parallel, each shaping the activity in the others.

All psychological states (including behaviors) emerge from the interplay of networks that work together, influencing and constraining one another in a sort of tug-of-war as they create the mind. From instance to instance, networks may be differentially constituted, configured, and recruited. This means that instances of a complex psychological category (e.g., different instances of anger) will be constituted as different neuronal assemblies within a person at different times (which means that there is considerable intraindividual variability, in addition to variability, that can be accounted for by differences across people or cultural contexts). It also means that phenomena that bear no subjective resemblance are constituted from many of the same brain areas.

This scientific ontology has a family resemblance to other discussions of how psychology might map to brain function (e.g., Henson, 2005 ; Price & Friston, 2005 ). Like these other scientific ontologies, it takes its inspiration from a number of notable neuroscience findings that together appear to constitute something of a paradigm shift in the field of cognitive neuroscience away from attempting to localize psychological functions to one spot or in a segregated network and toward more distributed approaches to understanding how the brain constitutes mental content. Specifically, the proposed ontology is consistent with: (a) research on large-scale distributed networks in the human brain ( Friston, 2002 ; Fuster, 2006 ; Mesulam, 1998 ; Seeley et al., 2007 ); (b) neuroanatomical evidence of pervasive feedback connections within the primate brain (e.g., Barbas, 2007 ) that are further enhanced in the human brain, as well as evidence on the functional importance of feedback ( Ghuman, Bar, Dobbins, & Schnyer, 2008 ); (c) population-based coding and multivoxel pattern analysis, in which information is contained in spatial patterns of neuronal activity (e.g., Haynes & Rees, 2006 ; Kay et al., 2008 ; Norman et al., 2006 ); (d) studies that demonstrate considerable degeneracy in brain processing (the idea being that there are multiple neuronal assemblies that can produce the same output; cf. Edelman 1987 ; Noppeney, Friston, & Price, 2004 ); (e) evidence that psychological states require temporally synchronized neuronal firing across different brain areas (e.g., Axmacher, Mormanna, Fernández, Elgera, & Fell, 2006 ; Dan Glauser & Scherer, 2008 ) so that the local field potentials that are associated with neuronal synchronization are strongly correlated to the hemodynamic signals that are measured in functional neuroimaging ( Niessing et al., 2005 ); and (f) the idea that neurons do not code for only one feature (i.e., even individual neurons in early sensory areas such as primary visual cortex may not be “feature detectors” in the strict sense of the term because they appear to respond to more than one feature; e.g., Basole, White, & Fitzpatrick, 2003 ). By combining these novel approaches, it becomes clear that psychological states are emergent phenomena that result from a complex system of dynamically interacting neurons within the human brain at multiple levels of description. Neither the complex psychological categories nor the psychological primitives that realize them correspond to particular locations in the brain per se, and thus do not reconcile well with the kind of localization approach to brain function that was inspired by neuropsychology, remained popular in neuroscience throughout much of the 20th century, and continues to prevail today. 10

The scientific ontology proposed here is also distinct from other scientific ontologies in three important ways. First, and perhaps most important, it deals with the existence of two domains of reality (one that is subjective and one that is objective) and their relation to one another.

Second, it helps solve a puzzle of why different sorts of behavioral tasks are associated with similar patterns of neural activity. For example, the so-called “default network” (which includes the ventral medial prefrontal cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortex, inferior parietal cortex, and at times, medial temporal structures like the hippocampus and lateral temporal cortex) shows increased activity not only during the spontaneous, highly associative mental activity that is without an external stimulus, but also when one remembers the autobiographical past, envisions the future, or infers mental states in others; during self-referential processing and moral decision making; while imagining fictitious experiences ( Buckner, Andrews-Hanna, & Schacter, 2008 ); during scene construction and contextual framing ( Bar, 2007 ); and during the experience and perception of emotion ( Barrett & Lindquist, 2008 ; Kober et al, 2008 ; Wager et al., 2008 ). Many functions have been proposed for this circuitry, but one approach is to ask what all these tasks have in common: They draw on stored, prior experience (in the form of episodic projection or mental simulation) that shapes sensory information from the body and the world. When working together as a functional network, this circuitry’s more general purpose may be to impart meaning to the current sensory array based on prior, episodic experience. They allow the brain to predict what the current sensory information means based on that last time something like it was encountered and to formulate an appropriate response. A similar view is discussed in Bar (2007) , who suggested that this circuitry functions to connect sensory input with memory to create predictions about what the sensory input means.

Finally, this psychological constructionist ontology also unifies a number of smaller scientific paradoxes with one solution. For example, it helps us to understand how perceptual memory can influence declarative memory tasks (even though implicit and explicit memory are supposed to be mechanistically different; e.g., Voss, Baym, & Paller, 2008 ), as well as how the same subjective feeling of remembering ( Phelps & Sharot, 2008 ) or mental imagery ( Kosslyn, Thompson, Sukel, & Alpert, 2005 ) can be produced in different ways (or, as I might say, with different recipes).

Principle 4: Recipes, Not Machines

In the psychological constructionist ontology proposed here, the metaphor for the mind in the 21st century is not a machine, but a recipe book. Psychological primitives are not separate, interacting bits and pieces of the mind that have no causal relation to one another like the cogs and wheels of a machine. Instead, they are more like the basic ingredients in a well-stocked pantry that can be used to make any number of different recipes (which make the mental states that people experience and give names to). 11 The products of the various recipes are not universal, although they are not infinitely variable or arbitrary either (e.g., bread can be baked with or without eggs, but you need some kind of grain to make bread what it is). The recipes are not universal. The recipe for anger will differ from instance to instance (with a context) within a person, and even if there is a modal recipe, it might differ across persons within a particular cultural context, as well as across cultural contexts. At the psychological level, however, the ingredients that make up the recipes might be universal (although how they function in conjunction with one another may not be). And as with all recipes, the amount of each ingredient is only one factor that is important to making the end product what it is. The process of combining ingredients is also important (e.g., are the dry ingredients added to the wet or vice versa, and are they whipped in, stirred in, or cut in?). As a result, it is not enough to just identify what the factors are, but also how they coordinate and shape one another during the process of construction.

The recipe analogy also helps us to see the scientific utility of distinguishing between complex psychological categories, psychological primitives, and neuronal firing. Scientists must understand that the category anger differs at each level in much the same way that the category bread differs for a food critic, a chef, or a chemist. Food critics don’t need to know the recipe for two different breads to be able to say which one has the preferred flavor and texture. If a chef wants to know which bread will taste best with a particular meal, it helps to know the recipe, or at least some of the key ingredients. And although a chef must know the recipe, he or she doesn’t need to know that flour and water interact to produce an interconnected network of coiled proteins (called gluten) that trap and hold the gases made by the yeast when bread is baking; it is only necessary to know that one must add yeast for bread to rise. That being said, it is much more efficient (and less costly in both the economic and caloric sense) to change the taste of bread by modifying the recipe than by slathering a slice in butter and jam. And although it is not necessary, all chefs know that it helps to have some knowledge of chemistry, otherwise experimenting with changing the recipe can feel like shots in the dark.

Principle 5: Probabilistic Causation, Not Linear Causation

If mental events are constructed like recipes, then goals or anger or memories or attitudes do not cause behavior in the typical mechanistic way that psychologists now think about causation, where Psychological Process A localized in Brain Area 1 causes the separate and distinct Psychological Process B localized in Brain Area 2, and so on (see Fig. 2a ). Saying that anger causes aggressive behavior, for example, might translate into the claim that one constructed mental state corresponding to Brain State A at Time 1 (categorized as anger ) increases the probability that a second constructed mental state corresponding to Brain State B at Time 2 (slamming one’s fist against the table) will occur (see Fig. 2b ). This is similar to what connectionist modelers like Spivey (2007) and computational neuroscientists like O’Reilly and Munakata (2000) might argue. Alternatively, saying that anger causes aggressive behavior might mean one constructed psychological state that realizes, among other things, a certain physical action (a hand with clenched fingers to strike a table) but registers them as separate events (anger on the one hand, and the behavior of slamming one’s fist against the table on the other) because the inferred intentions for each are different (blocked goals and a desire to cause harm, respectively). Either way, to say that a person pounds a table because he is angry is to give a reason for the behavior, and reasons are not causes for behavior and therefore do not constitute an explanation of it (for a discussion, see Searle, 2007 ).

Two models of mental causation. A: In the mechanistic linear model, Psychological Process A localized in Brain Area 1 causes the separate and distinct Psychological Process B localized in Brain Area 2, and so on. B: In the probabilistic model, Brain State A at Time 1 (left panel) makes it easier to enter Brain State B than Brain State C at Time 2 (right panel).

Either option points to the implication that psychologists must abandon the linear logic of an experiment as a metaphor for how the mind works. In the classic experiment, we present a participant (be it a human or some nonhuman animal) with some sensory stimulation (a stimulus), and then we measure some response. Correspondingly, psychological models of the mind (and brain) almost always follow a similar ordering (stimulus → organism → response). Neurons are presumed to generally lie quiet until stimulated by a source from the external world. Scientists talk about independent variables because we assume that they exist separate from the participant.

In real life, however, there are no independent variables. Our brains (not an experimenter) help to determine what is a stimulus and what is not, in part by predicting what will be important in the future ( Bar, 2007 ). Said another way, the current state of the human brain makes some sensory stimulation into information and relegates the rest to the psychologically impotent category of physical surroundings . In this way, sensory stimulation from the world only modulates preexisting neuronal activity, but does not cause it outright ( Llinas, Ribary, Contreras, & Pedroarena, 1998 ), and our brain contributes to every mental moment whether we experience a sense of agency or not (and usually we do not). This means that the simple linear models of psychological phenomena that psychologists often construct (stimulus → organism → response) may not really offer true explanations of psychological events.

The implication, then, is that mental events are not independent of one another. They occur in a context of what came before and what is predicted in the future. This kind of model building is easy for a human brain to accomplish, but difficult for a human mind to discover, because we have a tendency to think about ingredients in separate and sequential rather than emergent terms (e.g., Hegarty, 1992 ).

LOSING YOUR MIND?

As complex categories such as emotions , memories , goals , and the self are collections of mental states that are created from a more basic set of psychological ingredients, it might be tempting to assume that psychology can dispense with the complex categories altogether. After all, a complex psychological category like anger will not easily support the accumulation of knowledge about how anger is caused if varieties of anger are constituted by many different recipes. This was certainly William James’ position when describing his constructionist approach: “ Having the goose which lays the golden eggs, the description of each egg already laid is a minor matter.” ( James, 1890 , p. 449). When it came to emotion, James was both a constructionist and a material reductionist espousing a token–token identity model of emotion, in which every instance of emotion that feels different, even when part of the same category, can be ontologically reduced to a distinctive physical state (as opposed to a type type identity model in which every kind of emotion can be reduced to one and only one type of physical state). Like James, some scientists believe that once we understand how such psychological events are implemented in the brain, we won’t need a science of psychology at all. Mental states will be reduced to brain states, and psychology will disappear. But even William James can be wrong.

In the constructionist account proposed here, a process should not be confused with the mental content it produces, but neither can it replace the need for describing that content. Said another way, the kind of material reductionism that James advocated should be avoided if for no other than the very pragmatic reason that complex psychological categories are the targets of explanation in psychology. You have to know what you are explaining in order to have something to explain. You have to be able to identify it and describe it well. A scientific approach to understanding any psychological phenomenon requires both description (“What is it?”) and explanation (“How was it constructed or made?”).

But the more important reason to avoid material reduction is that the various phenomena we are discussing (complex psychological categories, psychological primitives, and neuronal firing) each exist at different levels of scientific inquiry and do not exist at others. Complex psychological categories like cognition ( memories , beliefs , imaginings , thoughts ), emotions ( anger , fear , happiness ), and other varieties of psychological categories ( the self , attitudes , and so on) are phenomena that fall squarely in the social science camp. They dwell at the boundary between sociology and anthropology on the one hand, and psychology on the other. Being observer-dependent categories that exist by virtue of collective intention (a group of human minds agree that anger exists and so it does), they are phenomenological distinctions. To understand them is to understand the nature, causes, and functions of these phenomenological distinctions (or the distinctions between whatever categories exist in your cultural context). They may not correspond to the brute facts of neuronal firing, but they are real in a relational way. If I categorize my mental state as a thought (instead of a feeling) and communicate this to you, you will understand something about the degree to which I feel responsible for that state and the degree to which I feel compelled to act on it, as long as you belong to a culture where the emotion cognition distinction exists (because in some cultures it does not). Furthermore, from a descriptive standpoint, we have to understand what these categories are for, both for the collective (which could be a dyad or a group of people) and for the individual. They can be epistemologically objective (i.e., studied with the methods of science) because they exist by consensus (in fact, this is what the science of emotion recognition is). And these categories may even have a biologically constructive quality of their own (see Fig. 3 ). As many neuroscientists have pointed out, humans are not born with the genetic material to provide a sufficient blueprint for the synaptic complexity that characterizes our brains. Instead, our genetic make up requires plasticity. Evolution has endowed us with the capacity to shape the microstructure of our own brains, in part via the complex categories that we transmit to one another within the social and cultural context.

Causal relations among levels. Networks of neurons realize psychological primitives that in turn are the basic ingredients of the mind. These basic ingredients construct instances of complex psychological categories like the self , attitudes , controlled processing , emotion , and so on.

At the other end of the continuum, there are brain states that are made up of collections of neurons firing with some frequency. Brain states are phenomena that fall squarely in the natural science camp. Brain states are observer-independent—they do not require the mind they create to recognize them. In realizing the mind, they change from moment to moment within a person, and they certainly vary across people. But understanding how a neuron fires is not the same as understanding why it fires, and the latter question cannot be answered without appealing to something psychological.

In between are psychological primitives—the basic ingredients of the mind that are informed by both the categories above and below them. They are not completely observer-independent, but neither are they free from the objective fact of the workings of the brain. Psychological primitives are caused by physical and chemical processes in the brain, but understanding these causes alone will never provide a sufficient scientific understanding of what psychological primitives are. They, too, have content that must be described for a complete understanding of what they are. That being said, when discussing psychological primitives, the structure of the brain cannot be ignored either. Psychological primitives will not necessarily replace complex psychological categories in the science of psychology, although sometimes they should. Whether complex psychological categories can be ontologically reduced to psychological primitives depends on the question that a scientist is trying to answer.

As a result of all this, it is possible to causally reduce complex psychological events to brain states and psychological primitives to distributed neuronal activity (what Searle, 1992 , calls causal reduction ) without redefining the mental in terms of the physical (what Searle calls ontological reduction ). Just as knowing that a car is made of atoms (or quarks) will not help a mechanic understand what happens when the motor stops working (Searle’s example), the firing of neurons alone is not sufficient for a scientific understanding of why a book is enjoyable, whether you enjoyed the book the last time you read it, why you like to read, or what joy feels like.

Now, it may be possible that the scientific need for psychological primitives is merely the result of the rudimentary state of cognitive neuroscience methods, and that even these psychological categories can be dispensed with once we have methods that can better measure cortical columns, which are (by conventional accounts) the smallest unit of functional specialization in the cortex (whose size is measured in microns). 12 It is possible that once we can measure columns in a human cortex while it is realizing some psychological state (e.g., see Kamitani & Tong, 2005 ), “what” (process) may finally correspond to “where” (one specific place in the brain), and it will be possible to ontologically reduce psychological primitives into the functioning of these units. 13 (Although this discussion is not meant to imply that only the cortex is important to psychology; it goes without saying that subcortical areas are important.

But I suspect this will not happen, for four reasons. First of all, there is some debate over whether columns are, in fact, the most basic functional units of cortical organization. Dendrites and axons of the neurons within a column extend beyond those columns ( DeFilpe et al., 2007 ; Douglas & Martin, 2007 ), which suggests that the functional units of the cortex may be somewhat larger than a column itself. Second, a single neuron within a column can participate in a number of different neuronal assemblies, depending on the frequency and timing of its firing ( Izhikevich, Desai, Walcott, & Hoppensteadt, 2003 ), which suggests that a given neuron can potentially participate in a variety of different psychological primitives (meaning it is selective, rather than specific, for a function). Third, recent evidence suggests that specific neurons do not necessarily code for single features of a stimulus. A recent study in ferrets suggests that individual neurons (when participating in neuronal assemblies) appear to respond to more than one type of sensory cue, even in primary sensory areas where receptive fields for neurons are supposed to be well defined (as in primary visual cortex or V1; Basole et al., 2003 ). In addition, a recent study with rats demonstrates that there is a functional remapping of cells in the nucleus accumbens (part of the ventral striatum)—sometimes they code for reward and other times for threat, depending on the context ( Reynolds & Berridge, 2008 ).

Finally, and perhaps most controversially, it may be a bit of an overstatement to assume that all humans have exactly the same nervous system. Human brains continue to expand at a rapid rate after birth ( Clancy, Darlington, & Finlay, 2001 ), with most of the size increase being due to changes in connectivity with other neurons ( Schoenemann, Sheehan, & Glotzer, 2005 ; for a review, see Schoenemann, 2006 ; but see Schenker, Desgouttes, & Semendeferi, 2005 ), including an increase in the size dendritic trees and density of dendritic spines ( Mai & Ashwell, 2004 ). This means that although all humans may have the same brain at a gross anatomical level, the connections between neurons are exceptionally plastic and responsive to experience and environmental influence, producing considerable variability in brains at the micro level. The implication is that the neuronal networks that constitute psychological primitives will be molded by experience or epigenetic influences and that they may not be isometric across people.

If these kinds of findings forecast the future of neuroscience, then they suggest even more strongly that psychological primitives may be the best categories for consistently describing what the brain is doing when it realizes the mind. If one accepts this reasoning, then psychology will never disappear in the face of neuroscience.

CONCLUSIONS

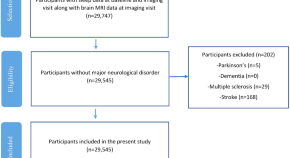

As a science of the mind, psychology is equipped with the ability to analyze how being human affects the process of doing science. We are in a better position than most to see how scientists make unintentionally biased observations of the world and have the capacity to correct for this all too common mistake. For the last century, psychology has largely used phenomenological categories to ground our scientific investigations into the mind and behavior. These categories influence the questions we ask, the experiments we design, and the interpretation of our data. We have spent the last century differentiating among psychological phenomena, improving on their labels, and searching for their correspondence in the natural world (i.e., locations in the brain).