Key Takeaways

- Alcohol is among the most used drugs, plays a large role in many societies and cultures around the world, 1 and greatly impacts public health. 2,3 More people over age 12 in the United States have used alcohol in the past year than any other drug or tobacco product, and alcohol use disorder is the most common type of substance use disorder in the United States. 4

- NIDA works closely with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) , the lead NIH institute supporting and conducting research on the impact of alcohol use on human health and well-being. For information on alcohol and alcohol use disorder , please visit the NIAAA website .

- Because many people use alcohol while using other drugs, 4 NIDA supports and conducts research on both the biological and social dynamics between alcohol use and the use of other substances.

Looking for Treatment?

Use the SAMHSA Treatment Locator or call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) .

NIH Resources

- Find treatment for alcohol use disorder and alcohol addiction (previously called alcoholism) using the NIAAA Alcohol Treatment Navigator .

- Read more about the latest advances in alcohol addiction research on the NIAAA Director’s Blog .

- Learn more about how NIH Institutes and Centers work together to better understand, treat and prevent addiction through the Collaborative Research on Addiction at NIH (CRAN) initiative.

- Learn more about the scientific meeting “ Opioid Use in the Context of Polysubstance Use: Research Opportunities for Prevention, Treatment, and Sustained Recovery .”

NIDA Resources

- See the latest statistics on alcohol use among young students from NIDA’s Monitoring the Future Survey.

Addiction often goes hand-in-hand with other mental illnesses. both must be addressed., reported drug use among adolescents continued to hold below pre-pandemic levels in 2023, heart medication shows potential as treatment for alcohol use disorder, marijuana and hallucinogen use among young adults reached all time-high in 2021, additional resources.

- Find basic health information on alcohol use disorder from MEDLINEplus , a service of NIH’s National Library of Medicine (NIH).

- Read Alcohol Misuse information from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- Learn more about medical approaches to treating alcohol use disorder from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in Medication for the Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder: A Brief Guide .

- Read Alcohol Misuse Prevention: A Conversation for Everyone from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

- Sudhinaraset M, Wigglesworth C, Takeuchi DT. Social and Cultural Contexts of Alcohol Use: Influences in a Social-Ecological Framework. Alcohol Res. 2016;38(1):35-45.

- Witkiewitz K, Litten RZ, Leggio L. Advances in the science and treatment of alcohol use disorder. Sci Adv. 2019;5(9):eaax4043. Published 2019 Sep 25. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax4043

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 [published correction appears in Lancet. 2018 Sep 29;392(10153):1116] [published correction appears in Lancet. 2019 Jun 22;393(10190):e44]. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1015-1035. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2

- Substance Abuse Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, SAMHSA . Accessed January 2023.

Deaths from Excessive Alcohol Use — United States, 2016–2021

Weekly / February 29, 2024 / 73(8);154–161

Marissa B. Esser, PhD 1 ; Adam Sherk, PhD 2 ; Yong Liu, MD 1 ; Timothy S. Naimi, MD 2 ( View author affiliations )

What is already known about this topic?

U.S. deaths from causes fully due to excessive alcohol use increased during the past 2 decades.

What is added by this report?

Average annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use, including partially and fully alcohol-attributable conditions, increased approximately 29% from 137,927 during 2016–2017 to 178,307 during 2020–2021, and age-standardized death rates increased from approximately 38 to 48 per 100,000 population. During this time, deaths from excessive drinking among males increased approximately 27%, from 94,362 per year to 119,606, and among females increased approximately 35%, from 43,565 per year to 58,701.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Evidence-based alcohol policies (e.g., reducing the number and concentration of places selling alcohol and increasing alcohol taxes) could help reverse increasing alcohol-attributable death rates.

- Article PDF

- Full Issue PDF

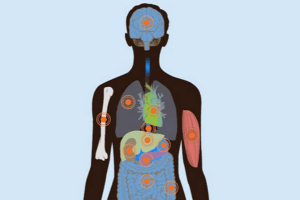

Deaths from causes fully attributable to alcohol use have increased during the past 2 decades in the United States, particularly from 2019 to 2020, concurrent with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, previous studies of trends have not assessed underlying causes of deaths that are partially attributable to alcohol use, such as injuries or certain types of cancer. CDC’s Alcohol-Related Disease Impact application was used to estimate the average annual number and age-standardized rate of deaths from excessive alcohol use in the United States based on 58 alcohol-related causes of death during three periods (2016–2017, 2018–2019, and 2020–2021). Average annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use increased 29.3%, from 137,927 during 2016–2017 to 178,307 during 2020–2021; age-standardized alcohol-related death rates increased from 38.1 to 47.6 per 100,000 population. During this time, deaths from excessive alcohol use among males increased 26.8%, from 94,362 per year to 119,606, and among females increased 34.7%, from 43,565 per year to 58,701. Implementation of evidence-based policies that reduce the availability and accessibility of alcohol and increase its price (e.g., policies that reduce the number and concentration of places selling alcohol and increase alcohol taxes) could reduce excessive alcohol use and alcohol-related deaths.

Introduction

Deaths from causes fully attributable to alcohol use (i.e., 100% alcohol-attributable causes, such as alcoholic liver disease and alcohol use disorder) have increased during the past 2 decades in the United States ( 1 ); rates were particularly elevated from 2019 to 2020,* concurrent with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, emergency department visit rates associated with acute alcohol use ( 2 ) and per capita alcohol sales † also increased during this time. Previous studies of trends have not included underlying causes of death that are partially attributable to alcohol ( 1 , 3 ), such as injuries or certain types of cancer, for which drinking is a substantial risk factor ( 4 , 5 ). A comprehensive assessment of changes in deaths from excessive alcohol use that includes conditions that are fully and partially attributable to alcohol can guide the rationale for and implementation of effective prevention strategies.

Data Sources and Measures

Total U.S. deaths from alcohol-related conditions during 2016–2021 identified from the National Vital Statistics System were grouped into three periods (2016–2017, 2018–2019, and 2020–2021). Deaths were defined using the underlying cause of death for the 58 alcohol-related conditions § in CDC’s Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) application and estimated using ARDI methods. ¶ For each cause of death, alcohol-attributable fractions were used, reflecting the cause-specific proportion that is due to excessive alcohol use. For the 15 fully alcohol-attributable conditions,** the alcohol-attributable fraction is 1.0. Fully alcohol-attributable conditions include the 100% alcohol-attributable chronic causes as well as the 100% alcohol-attributable acute causes (i.e., alcohol poisonings that are a subset of deaths in the alcohol-related poisonings category and deaths from suicide by exposure to alcohol that are a subset of the suicide category). Partially alcohol-attributable conditions are those that are caused by alcohol use or other factors, and alcohol-attributable fractions are applied to calculate the deaths from alcohol use. For most of the partially alcohol-related chronic conditions, population-attributable fractions were estimated using relative risks from published meta-analyses and adjusted prevalence estimates of low, medium, and high average daily alcohol use among U.S. adults. Prevalence estimates were obtained from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System †† and adjusted using alcohol per capita sales information to account for underreporting of self-reported drinking ( 6 ).

Alcohol-attributable fractions for acute causes (e.g., injuries) were determined mostly from a recent meta-analysis that generally measured the proportion of decedents who had a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) ≥0.10% ( 7 ). Alcohol-attributable fractions for motor vehicle crashes and other road vehicle crash deaths were obtained from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System, based on the proportion of crash deaths that involved a decedent with BAC ≥0.08%. §§

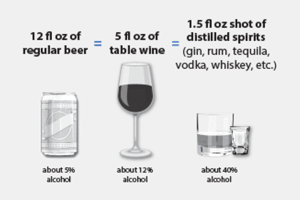

Deaths from excessive alcohol use (as opposed to deaths from any level of drinking) includes all decedents whose deaths were attributed to conditions that are fully caused by alcohol use, alcohol-related acute causes of death that involved binge drinking, and alcohol-related chronic conditions that involved medium or high average daily levels of alcohol use. For the chronic causes of death estimated using cause-specific population-attributable fractions by sex, the relative risks for death at medium daily average drinking levels (females: >1 to ≤2 drinks, males: >2 to ≤4 drinks) and high daily average drinking levels (females: >2 drinks, males: >4 drinks) were relative to the risks at low daily average drinking levels (females: >0 to ≤1 drink, males: >0 to ≤2 drinks).

Data Analyses

The average annual number of deaths resulting from excessive alcohol use during three 2-year periods, percentage change in numbers of deaths, ¶¶ and death rates were calculated overall and by sex and cause of death category. The number of sex-stratified deaths from excessive drinking was also assessed by age group. In general, deaths from chronic conditions were calculated among decedents aged ≥20 years, and deaths from acute causes were calculated among decedents aged ≥15 years. Younger children whose deaths resulted from someone else’s drinking (e.g., as passengers in motor vehicle crashes) were also included for several causes of death. Death rates (deaths per 100,000 population) were calculated based on midyear postcensal population estimates and age-standardized to the 2000 U.S. Census Bureau standard population. Nonoverlapping 95% CIs were considered significantly different. Analyses were conducted using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute). This activity was reviewed by CDC, deemed not research, and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.***

Average annual deaths from excessive alcohol use in the United States increased 5.3%, from 137,927 during 2016–2017 to 145,253 during 2018–2019; these deaths then increased more sharply (22.8%) from 2018–2019 to 178,307 during 2020–2021, for an overall 29.3% increase from 2016–2017 to 2020–2021 ( Table 1 ). Age-standardized death rates increased from 38.1 per 100,000 population during 2016–2017 to 39.1 during 2018–2019 to 47.6 during 2020–2021. Approximately two thirds of these deaths resulted from chronic causes during each period: alcohol-attributable death rates from chronic causes increased from 23.2 per 100,000 population to 24.3 to 29.4 during the respective analysis periods. During 2020–2021, fully alcohol-attributable causes ††† accounted for 51,665 deaths (29.0% of all alcohol-attributable deaths), a 46.2% increase compared with the 35,344 deaths that occurred during 2016–2017. During 2020–2021, partially alcohol-attributable causes accounted for 126,642 deaths (71.0% of all alcohol-attributable deaths), a 23.5% increase compared with the 102,583 partially alcohol-attributable deaths that occurred during 2016–2017.

Increases Among Males and Females

The average annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use among males increased by 25,244 (26.8%), from 94,362 deaths during 2016–2017 to 119,606 during 2020–2021 ( Table 2 ). Age-standardized death rates among males increased from 54.8 per 100,000 population during 2016–2017 to 55.9 during 2018–2019, and to 66.9 during 2020–2021. During each period, among all excessive alcohol use cause of death categories, death rates among males were highest from 100% alcohol-attributable chronic conditions.

Among females, the average annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use increased by 15,136 (34.7%), from 43,565 during 2016–2017, to 58,701 during 2020–2021. Age-standardized alcohol-attributable death rates among females increased from 22.7 per 100,000 population during 2016–2017 to 23.6 during 2018–2019, and to 29.4 during 2020–2021. Death rates among females were highest from heart disease and stroke during each period. Among both males and females, alcohol-attributable death rates increased for most cause of death categories. The average number of sex-specific alcohol-attributable deaths increased among all age groups from 2016–2017 to 2020–2021( Figure ).

From 2016–2017 to 2020–2021, the average annual number of U.S. deaths from excessive alcohol use increased by more than 40,000 (29%), from approximately 138,000 per year (2016–2017) to 178,000 per year (2020–2021). This increase translates to an average of approximately 488 deaths each day from excessive drinking during 2020–2021. From 2016–2017 to 2020–2021, the average annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use increased by more than 25,000 among males and more than 15,000 among females; however, the percentage increase in the number of deaths during this time was larger for females (approximately 35% increase) than for males (approximately 27%). These findings are consistent with another recent study that found a larger increase in fully alcohol-attributable death rates among females compared with males ( 8 ).

Increases in deaths from excessive alcohol use during the study period occurred among all age groups. A recent study found that one in eight total deaths among U.S. adults aged 20–64 years during 2015–2019 resulted from excessive alcohol use ( 9 ). Because of the increases in these deaths during 2020–2021, including among adults in the same age group, excessive alcohol use could account for an even higher proportion of total deaths during that 2-year period. In addition, data from Monitoring the Future, an ongoing study of the behaviors, attitudes, and values of U.S. residents from adolescence through adulthood, showed that the prevalence of binge drinking among adults aged 35–50 years was higher in 2022 than in any other year during the past decade §§§ ; this increase could contribute to future increases in alcohol-attributable deaths. In this study, fewer than one third of deaths from excessive alcohol use were from fully alcohol-attributable causes, highlighting the importance of also assessing partially alcohol-attributable causes to better understand the harms from excessive drinking, including binge drinking.

The nearly 23% increase in the deaths from excessive alcohol use that occurred from 2018–2019 to 2020–2021 was approximately four times as high as the previous 5% increase that occurred from 2016–2017 to 2018–2019. Increases in the availability of alcohol in many states might have contributed to this disproportionate increase ( 10 ). During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021, policies were widely implemented to expand alcohol carryout and delivery to homes, and places that sold alcohol for off-premise consumption (e.g., liquor stores) were deemed as essential businesses in many states (and remained open during lockdowns). ¶¶¶ General delays in seeking medical attention, including avoidance of emergency departments**** for alcohol-related conditions †††† ; stress, loneliness, and social isolation; and mental health conditions might also have contributed to the increase in deaths from excessive alcohol use during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations

The findings in this report are subject to at least two limitations. First, population-attributable fractions were calculated based on data including only persons who currently drank alcohol. Because some persons who formerly drank alcohol might also die from alcohol-related causes, population-attributable fractions might underestimate alcohol-attributable deaths. Second, several conditions (e.g., HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis) for which excessive alcohol use is a substantial risk factor were not included because relative risk estimates relevant to the U.S. population were not available for calculating the portion of these deaths attributable to drinking alcohol, further contributing to conservative death estimates in this report.

Implications for Public Health Practice

States and communities can discourage excessive alcohol use and reverse recent increases in alcohol-attributable deaths by implementing comprehensive strategies, including evidence-based alcohol policies that reduce the availability and accessibility of alcohol and increase its price (e.g., policies that reduce the number and concentration of places selling alcohol and increase alcohol taxes). §§§§ Also, CDC’s electronic screening and brief intervention ¶¶¶¶ can be used in primary and acute care, or nonclinical, settings to allow adults to check their alcohol use, receive personalized feedback, and create a plan for drinking less alcohol. Integration of screening and brief intervention into routine clinical services***** for adults and mass media communications campaigns ††††† to support people in drinking less can also help. Increased use of these strategies, particularly effective alcohol policies, could help reduce excessive alcohol use and related deaths among persons who drink and also reduce harms to persons who are affected by others’ alcohol use (e.g., child and adult relatives, friends, and strangers).

Corresponding author: Marissa B. Esser, [email protected] .

1 Division of Population Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC; 2 Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

All authors have completed and submitted the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Adam Sherk reports institutional support from the Canadian Cancer Society and Canadian Institutes for Health Research. No other potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

* https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db448.htm

† https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance-reports/surveillance120

§ https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/ardi/alcohol-related-icd-codes.html

¶ https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/ardi/methods.html

** Deaths from causes fully attributable to alcohol use (i.e., 100% alcohol-attributable causes) include alcohol abuse, alcohol cardiomyopathy, alcohol dependence syndrome, alcohol poisoning, alcohol polyneuropathy, alcohol-induced acute pancreatitis, alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis, alcoholic gastritis, alcoholic liver disease, alcoholic myopathy, alcoholic psychosis, degeneration of the nervous system due to alcohol use, fetal alcohol syndrome, fetus and newborn issues caused by maternal alcohol use, and suicide by exposure to alcohol.

†† Daily average alcohol use prevalence estimates were from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System ( https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/data_documentation/index.htm ), aligning with the respective years of the death data for the three periods in this study, and used in population attributable fraction calculations. Prevalence estimates of daily average alcohol use were calculated for three levels, including low (females: >0 to ≤1 drink, males: >0 to ≤2 drinks), medium (females: >1 to ≤2 drinks, males: >2 to ≤4 drinks), and high (females: >2 drinks, males: >4 drinks), unless the source of the relative risk estimates specified otherwise. For the three periods in this study, the categorical relative risks were calculated to correspond with the median of the alcohol use distribution for each drinking level.

§§ https://www.nhtsa.gov/research-data/fatality-analysis-reporting-system-fars

¶¶ The percentage represents the equation {[(estimated average annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use in more recent period − estimated average annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use in earlier period) / estimated average annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use in earlier period] x 100}.

*** 45 C.F.R. part 46.102(l)(2), 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. Sect. 241(d); 5 U.S.C. Sect. 552a; 44 U.S.C. Sect. 3501 et seq.

††† Fully alcohol-attributable conditions include the 100% alcohol-attributable chronic causes as well as the 100% alcohol-attributable acute causes (i.e., alcohol poisonings that are a subset of deaths in the alcohol-related poisonings category and suicide by exposure to alcohol that are a subset of deaths in the suicide category).

§§§ https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/mtfpanel2023.pdf

¶¶¶ https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/file-page/digest_state_alcohol_policies_in_response_to_covid-19_220101.pdf

**** https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7015a3.htm

†††† https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/joim.13545

§§§§ https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/prevention.htm

¶¶¶¶ https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/checkyourdrinking/index.html

***** https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/unhealthy-alcohol-use-in-adolescents-and-adults-screening-and-behavioral-counseling-interventions

††††† https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/health-communication-and-social-marketing-campaigns-include-mass-media-and-health-related.html

- Maleki N, Yunusa I, Karaye IM. Alcohol-induced mortality in the USA: trends from 1999 to 2020. Int J Ment Health Addict 2023;6:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01083-1 PMID:37363762

- Esser MB, Idaikkadar N, Kite-Powell A, Thomas C, Greenlund KJ. Trends in emergency department visits related to acute alcohol consumption before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, 2018–2020. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep 2022;3:100049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100049 PMID:35368619

- White AM, Castle IP, Powell PA, Hingson RW, Koob GF. Alcohol-related deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2022;327:1704–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.4308 PMID:35302593

- Naimi TS, Sherk A, Esser MB, Zhao J. Estimating alcohol-attributable injury deaths: a comparison of epidemiological methods. Addiction 2023;118:2466–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16299 PMID:37466014

- Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:31–54. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21440 PMID:29160902

- Esser MB, Sherk A, Subbaraman MS, et al. Improving estimates of alcohol-attributable deaths in the United States: impact of adjusting for the underreporting of alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2022;83:134–44. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2022.83.134 PMID:35040769

- Alpert HR, Slater ME, Yoon YH, Chen CM, Winstanley N, Esser MB. Alcohol consumption and 15 causes of fatal injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med 2022;63:286–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.03.025 PMID:35581102

- Karaye IM, Maleki N, Hassan N, Yunusa I. Trends in alcohol-related deaths by sex in the US, 1999–2020. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2326346. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.26346 PMID:37505494

- Esser MB, Leung G, Sherk A, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among US adults aged 20 to 64 years, 2015 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2239485. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.39485 PMID:36318209

- Trangenstein PJ, Greenfield TK, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Kerr WC. Beverage-and context-specific alcohol consumption during COVID-19 in the United States: the role of alcohol to-go and delivery purchases. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2023;84:842–51. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.22-00408 PMID:37449953

* Includes 58 causes of death related to alcohol use. Deaths from excessive alcohol use includes all decedents whose deaths were attributed to conditions that were fully caused by alcohol use, alcohol-related acute causes of death that involved binge drinking, and alcohol-related chronic conditions that involved medium (females: >1 to ≤2 drinks, males: >2 to ≤4 drinks) or high (females: >2 drinks, males: >4 drinks) daily average drinking levels. † Nonoverlapping 95% CIs of age-standardized death rates compared with 2016–2017. § Nonoverlapping 95% CIs of age-standardized death rates compared with 2018–2019. ¶ The 100% alcohol-attributable chronic causes of death included alcohol abuse, alcohol cardiomyopathy, alcohol dependence syndrome, alcohol polyneuropathy, alcohol-induced acute pancreatitis, alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis, alcoholic gastritis, alcoholic liver disease, alcoholic myopathy, and alcoholic psychosis. ** Cancer deaths from excessive alcohol use were estimated for deaths from breast cancer (females only), colorectal cancer, esophageal cancer (for the proportion due to squamous cell carcinoma only, based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program data in 17 states), laryngeal cancer, liver cancer, oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer (males only), and stomach cancer. Deaths from pancreatic and stomach cancers were calculated among people consuming high daily average levels of alcohol only (females: >2 drinks, males: >4 drinks). †† Deaths from excessive alcohol use from heart disease and stroke were estimated for deaths from atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, hemorrhagic stroke, hypertension, and ischemic stroke. §§ Deaths from excessive alcohol use were estimated for deaths from conditions of the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas, including those from acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, esophageal varices, gallbladder disease, gastroesophageal hemorrhage, portal hypertension, and unspecified liver cirrhosis. ¶¶ Deaths from excessive alcohol use were estimated for deaths from other chronic conditions including chronic hepatitis; infant deaths due to low birthweight, preterm birth, and small for gestational age; pneumonia; and seizure disorder, seizures, and unprovoked epilepsy. *** Deaths from alcohol-related poisonings included those from alcohol poisoning (100% attributable to alcohol) and the portion of deaths from poisonings that involved another substance (e.g., drug overdoses) in addition to a high blood alcohol concentration (≥0.10%). ††† Deaths from excessive alcohol use from suicide included those from suicide by exposure to alcohol (100% attributable to alcohol) and a portion of deaths from suicide based on the alcohol-attributable fraction of 0.21. §§§ Deaths from excessive alcohol use from other acute conditions included the cause-specific portion of deaths for air-space transport, aspiration, child maltreatment, drowning, fall injuries, fire injuries, firearm injuries, homicide, hypothermia, motor vehicle nontraffic crashes, occupational and machine injuries, other road vehicle crashes, and water transport.

* Includes 58 causes of death related to alcohol use. Deaths from excessive alcohol use includes all decedents whose deaths were attributed to conditions that were fully caused by alcohol use, alcohol-related acute causes of death that involved binge drinking, and alcohol-related chronic conditions that involved medium (females: >1 to ≤2 drinks, males: >2 to ≤4 drinks) or high (females: >2 drinks, males: >4 drinks) daily average drinking levels. † Nonoverlapping 95% CIs of age-standardized death rates compared with 2016–2017. § Nonoverlapping 95% CIs of age-standardized death rates compared with 2018–2019. ¶ The 100% alcohol-attributable chronic causes of death included alcohol abuse, alcohol cardiomyopathy, alcohol dependence syndrome, alcohol polyneuropathy, alcohol-induced acute pancreatitis, and alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis, alcoholic gastritis, alcoholic liver disease, alcoholic myopathy, and alcoholic psychosis. ** Cancer deaths from excessive alcohol use were estimated for deaths from breast cancer (females only), colorectal cancer, esophageal cancer (for the proportion due to squamous cell carcinoma only, based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program data in 17 states), laryngeal cancer, liver cancer, oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer (males only), and stomach cancer. Deaths from pancreatic and stomach cancers were calculated among people consuming high daily average levels of alcohol only (females: >2 drinks, males: >4 drinks). †† Deaths from excessive alcohol use from heart disease and stroke were estimated for deaths from atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, hemorrhagic stroke, hypertension, and ischemic stroke. §§ Deaths from excessive alcohol use were estimated for deaths from conditions of the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas including those from acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, esophageal varices, gallbladder disease, gastroesophageal hemorrhage, portal hypertension, and unspecified liver cirrhosis. ¶¶ Deaths from excessive alcohol use were estimated for deaths from other chronic conditions including chronic hepatitis; infant deaths due to low birth weight, preterm birth, and small for gestational age; pneumonia; and seizure disorder, seizures, and unprovoked epilepsy. *** Deaths from alcohol-related poisonings included those from alcohol poisoning (100% attributable to alcohol) and the portion of deaths from poisonings that involved another substance (e.g., drug overdoses) in addition to a high blood alcohol concentration (≥0.10%). ††† Deaths from excessive alcohol use from suicide included those from suicide by exposure to alcohol (100% attributable to alcohol) and a portion of deaths from suicide based on the alcohol-attributable fraction of 0.21. §§§ No change in percentage of average annual deaths. ¶¶¶ Deaths from excessive alcohol use from other acute conditions included the cause-specific portion of deaths for air-space transport, aspiration, child maltreatment, drowning, fall injuries, fire injuries, firearm injuries, homicide, hypothermia, motor vehicle nontraffic crashes, occupational and machine injuries, other road vehicle crashes, and water transport.

FIGURE . Average annual number of deaths from excessive alcohol use,* by age group and period among males (A) and females (B) — United States, 2016–2021

* Deaths from excessive alcohol use includes all decedents whose deaths were attributed to conditions that were fully caused by alcohol use, alcohol-related acute causes of death that involved binge drinking, and alcohol-related chronic conditions that involved medium (females: >1 to ≤2 drinks, males: >2 to ≤4 drinks) or high (females: >2 drinks, males: >4 drinks) daily average drinking levels.

Suggested citation for this article: Esser MB, Sherk A, Liu Y, Naimi TS. Deaths from Excessive Alcohol Use — United States, 2016–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73:154–161. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7308a1 .

MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report are service marks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. References to non-CDC sites on the Internet are provided as a service to MMWR readers and do not constitute or imply endorsement of these organizations or their programs by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CDC is not responsible for the content of pages found at these sites. URL addresses listed in MMWR were current as of the date of publication.

All HTML versions of MMWR articles are generated from final proofs through an automated process. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version ( https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr ) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

The nih almanac, national institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism (niaaa).

- Important Events

Legislative Chronology

The mission of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) is to generate and disseminate fundamental knowledge about the adverse effects of alcohol on health and well-being, and apply that knowledge to improve diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of alcohol-related problems, including alcohol use disorder (AUD), across the lifespan.

NIAAA provides leadership in the national effort to reduce alcohol-related problems by:

- Conducting and supporting alcohol-related research in a wide range of scientific areas including neuroscience and behavior, epidemiology and prevention, treatment and recovery, and metabolism and health effects.

- Coordinating and collaborating with other research institutes and federal programs on alcohol-related issues.

- Collaborating with international, national, state, and local institutions, organizations, agencies, and programs engaged in alcohol-related work.

- Translating and disseminating research findings to health care providers, researchers, policymakers, and the public.

Important Events in NIAAA History

1970 —The Comprehensive Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Act was passed, establishing NIAAA as part of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Senator Harold E. Hughes of Iowa played a pivotal role in sponsoring the legislation, which recognized “alcohol abuse” and “alcoholism” as major public health problems.

1971 —The First Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health was issued in December, part of a series of triennial reports established to chart the progress made by alcohol research toward understanding, preventing, and treating alcohol abuse and alcoholism.

1974 —NIAAA became an independent Institute within the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA), which also housed NIMH and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

1977 —NIAAA organized the first national research workshop on fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which reviewed the state of the research on FAS.

1980 —NIAAA science and staff were instrumental to the development of the Report to the President and the Congress on Health Hazards Associated with Alcohol and Methods to Inform the General Public of these Hazards ; this report influenced the following year’s publication of the U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Alcohol and Pregnancy of 1981 .

1989 —NIAAA launched the Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism with the goal of identifying the specific genes underlying vulnerability to alcoholism as well as collecting clinical, neuropsychological, electrophysiological, and biochemical data, and establishing a repository of immortalized cell lines.

1991 —NIAAA began the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey, designed to study drinking practices, behaviors, and related problems.

1994 —The medical success of disulfiram, a drug approved in 1951 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), spotlighted the effectiveness of pharmacological approaches for treating AUD. In 1994 and 2004, respectively, scientific evidence from NIAAA-supported studies helped achieve FDA approval of two new medications: naltrexone and acamprosate. NIAAA-supported studies also provided the foundation for the FDA’s more recent change in AUD clinical trial endpoints, opening the door for regulatory approval of a larger number of candidate AUD medications. In 2007, NIAAA established the NIAAA Clinical Investigations Group, a network of sites established to accelerate phase 2 clinical trials of promising compounds, and later expanded NCIG to include early human laboratory studies.

1995 —NIAAA celebrated its 25th anniversary.

1996 —NIAAA established the Mark Keller Honorary Lecture Series. The series pays tribute to Mark Keller, a pioneer in the field of alcohol research, and features a lecture each year by an outstanding alcohol researcher who has made significant and long-term contributions to our understanding of alcohol's effects on the body and mind.

1999 —NIAAA organized the first National Alcohol Screening Day, created to provide public education, screening, and referral for treatment when indicated. The program was held at 1,717 sites across the United States, including 499 college sites.

NIAAA co-sponsored the launch of The Leadership to Keep Children Alcohol Free, a unique coalition of state governors' spouses, federal agencies, and public and private organizations that targets prevention of drinking in young people ages 9–15.

2001 —NIAAA launched the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, a representative sample of the U.S. population with data on alcohol and drug use; alcohol and drug abuse and dependence; and associated psychiatric and other co-occurring disorders.

2002 —NIAAA published A Call to Action: Changing the Culture of Drinking at U.S. Colleges , which was developed by the Task Force of the National Advisory Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as a comprehensive review of research on college drinking and the effectiveness of prevention programs.

2004 —NIAAA established the Underage Drinking Research Initiative by convening a steering committee of experts in adolescent development, child health, brain imaging, genetics, neuroscience, prevention research, and other research fields, with the goal of working towards a more complete and integrated scientific understanding of the environmental, biobehavioral, and genetic factors that promote initiation, maintenance, and acceleration of alcohol use among youth, framed within the context of human development.

2005 —NIAAA published Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician's Guide to help primary care and mental health clinicians incorporate alcohol screening and intervention into their practices. The 2005 edition introduced a simple one-question screening tool that streamlined recommendations published in earlier NIAAA guides.

The Surgeon General released the Surgeon General's Advisory on Alcohol Use in Pregnancy , updated from the original advisory released in 1981. As with the 1981 report, NIAAA science contributed significantly to the development of this document, and NIAAA staff were instrumental in its crafting.

2007 —NIAAA partnered with NIDA, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and HBO to produce Addiction, an Emmy-award winning documentary exploring alcohol and drug addiction, treatment, and recovery, and featuring interviews with medical researchers working to better understand and treat addictive disorders.

2008 —The Acting Surgeon General of the United States issued The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking . NIAAA’s Underage Drinking Research Initiative provided much of the scientific foundation for that document.

NIAAA published a special supplemental issue of the journal Pediatrics , presenting a developmental framework for understanding and addressing underage drinking as a guide to future research, prevention, and treatment efforts. The research reflected in these articles contributed to the development of The Surgeon General’s Call to Action To Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking .

2009 —NIAAA established the Jack Mendelson, M.D., Honorary Lecture Series. The series pays tribute to Dr. Mendelson’s contributions to the field of clinical alcohol research, and features a lecture each year by an outstanding alcohol researcher whose clinical research has made significant and long-term contributions to our understanding of susceptibility to alcohol use disorder (AUD), alcohol's effects on the brain and other organs, and the prevention and treatment of AUD.

NIAAA launched Rethinking Drinking , a website and booklet, following extensive audience usability testing. These resources offer valuable, research-based information enabling people to take a look at their drinking patterns and how these patterns may be affecting their health.

2010 —To celebrate NIAAA’s 40th anniversary, the Institute published a special double issue of its peer-reviewed journal, Alcohol Research & Health that describes the Institute’s public health impact and multidisciplinary contributions to alcohol research. Additionally, on October 4, 2010, the Institute hosted a special symposium recognizing the 40th anniversary, where, leaders in the field discussed the ways in which alcohol research has evolved over the past 40 years, as well as NIAAA's role in this progress.

2011 —NIAAA released Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention for Youth: A Practitioner's Guide , Developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Pediatrics, clinical researchers, and health practitioners, the guide introduced a two-question screening tool and an innovative youth alcohol risk estimator to help clinicians overcome time constraints and other common barriers to youth alcohol screening.

2012 —NIH announced the Trans-NIH Substance Use, Abuse, and Addiction Functional Integration to enhance the NIH Institute and Center (IC) collaborations around this important scientific and public health topic. The Functional Integration is a collaborative framework that draws on the collaboration among the NIH ICs on substance use, abuse, and addiction-related research. NIAAA and NIDA have made significant progress toward integrating their intramural research programs in substance use, abuse, and addiction, including the appointment of a single Clinical Director for both Institutes and the establishment of a joint genetics intramural research program and a common optogenetics lab. By pooling resources and expertise, the Functional Integration will identify cross-cutting areas of research and confront challenges faced by multiple Institutes and Centers.

2013 —NIAAA helped establish and participated in the NIH partnership, Collaborative Research on Addiction at NIH (CRAN). CRAN’s mission is to provide a strong collaborative framework to enable NIAAA, NIDA, and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), to integrate resources and expertise to advance substance use, abuse, and addiction research and public health outcomes. NIAAA helped launch a website to share funding opportunities and research resources readily with the public.

In addition, NIAAA developed and launched an online course for health care professionals to learn more about screening youth for alcohol problems. Doctors, nurses, psychologists, and others can take the online training to earn continuing medical education credits. The course, produced jointly with Medscape, shows providers how to conduct fast, evidence-based alcohol screening and brief intervention for patients ages 9–18. Since its launch in August, more than 5,000 health care professionals have earned credit for the course.

2015 —NIAAA launched CollegeAIM — the College Alcohol Intervention Matrix , a new resource to help schools address harmful and underage student drinking. In 2020, NIAAA published significant updates to the CollegeAIM website, updating resources and scientific evidence. NIAAA also added a clinician’s portal to the Alcohol Treatment Navigator website, helping clinicians to feel more confident making patient referrals for AUD.

2016 —NIAAA science and staff were instrumental to the development of Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health . HBO Documentary Films premiered Risky Drinking, which follows the stories of four people whose drinking dramatically affects their relationships and their lives. This 85-minute film features commentary by experts including NIAAA Director George F. Koob, Ph.D., and NIAAA Medical Project Officer Deidra Roach, M.D.

2017 —NIAAA issued the NIAAA Strategic Plan, 2017-2021.

NIAAA also launched the Alcohol Treatment Navigator website to help adults find alcohol treatment for themselves or an adult loved one.

2018 —CRAN, based on the need to understand how substance use and other experiences during adolescence influence development, established the Adolescent Behavioral and Cognitive (ABCD) Study , a large scale, long-term, longitudinal study. In 2018, the ABCD study successfully completed its baseline enrollment of 11,874 participants ages 9 to 10 and began follow-up assessments which will continue into adulthood.

2020 —NIAAA celebrated its 50th anniversary with a range of events and promotional activities. These efforts culminated with a virtual 50th anniversary science symposium on November 30 and December 1, “Alcohol Across the Lifespan: 50 Years of Evidence-Based Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment Research.” Presentations spotlighted scientific milestones, the current state of the science, and future opportunities for alcohol research.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, NIAAA developed a list of web-based resources for the research community, healthcare professionals, and the general public regarding the potential for alcohol misuse, including information about telehealth for alcohol treatment. NIAAA also supported research on trends in alcohol use during the pandemic, and served as the lead institute for the NIH RADx-rad request for applications on “Automatic Detection and Tracing of SARs-CoV-2” to support proof-of-concept research on automatic, real-time detection and tracing of SARS-COV-2.

2022 —NIAAA released The Healthcare Professional's Core Resource on Alcohol help healthcare professionals provide evidence-based care for people who drink alcohol. Created with busy clinicians in mind, the HPCR provides concise, thorough information designed to help them integrate alcohol care into their practice.

2023 —As part of its efforts to raise awareness of and combat underage drinking, NIAAA launched the web resources NIAAA for Middle School and NIAAA for Teens , as well as a virtual reality and video experience, Alcohol and Your Brain .

December 31, 1970 —NIAAA was established under authority of the Comprehensive Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Act of 1970 (Public Law 91-616) with authority to develop and conduct comprehensive health, education, training, research, and planning programs for the prevention and treatment of alcohol abuse and alcoholism.

May 14, 1974 —P.L. 93-282 was passed, establishing NIAAA, NIMH, and NIDA as coequal institutes within the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration (ADAMHA).

July 26, 1976 —NIAAA's research authority was expanded to include behavioral and biomedical etiology of the social and economic consequences of alcohol abuse and alcoholism under authority of the Comprehensive Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Prevention, Treatment, and Rehabilitation Act amendments of 1976 (P.L. 94-371).

August 1981 —The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 (P.L. 97-35) was passed, transferring responsibility and funding for alcoholism treatment services to the states through the creation of an Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Services block grant administered by ADAMHA and strengthening NIAAA's research mission.

October 27, 1986 —A new Office for Substance Abuse Prevention in ADAMHA was created through the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-570), which consolidated the remainder of NIAAA's non-research prevention activities with those of NIDA and permitted NIAAA's total commitment to provide national stewardship to alcohol research.

July 10, 1992 —NIAAA became a new NIH research institute under the ADAMHA Reorganization Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-321).

December 20, 2006 —The Sober Truth on Preventing Underage Drinking Act (P.L. 109-422) was passed, requiring the Secretary of Health and Human Services to formally establish and enhance the efforts of the Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Prevention of Underage Drinking that began operating in 2004.

December 13, 2016 —The 21 st Century Cures Act (P.L. 114-255) was passed, requiring the Directors of NIAAA, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to serve as ex officio members of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Advisory Councils. It also called for increased collaboration between SAMHSA and NIAAA, NIDA, and the States to promote the study of substance abuse prevention and the dissemination and implementation of research findings that will improve the delivery and effectiveness of substance abuse prevention activities. Finally, it reauthorized the Sober Truth on Preventing Underage Drinking Act from 2018 through 2022.

Biographical Sketch of NIAAA Director George F. Koob, Ph.D.

George F. Koob, Ph.D. , is an internationally recognized expert on alcohol and stress, and the neurobiology of alcohol and drug addiction. As the Director of the NIAAA, he provides leadership in the national effort to reduce the public health burden associated with alcohol misuse. He oversees a broad portfolio of alcohol research ranging from basic science to epidemiology, diagnostics, prevention, and treatment.

Dr. Koob earned his doctorate in Behavioral Physiology from Johns Hopkins University in 1972. Prior to taking the helm at NIAAA, he served as Professor and Chair of the Scripps’ Committee on the Neurobiology of Addictive Disorders and Director of the Alcohol Research Center at the Scripps Research Institute. Early in his career, Dr. Koob conducted research in the Department of Neurophysiology at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and in the Arthur Vining Davis Center for Behavioral Neurobiology at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. He was a post-doctoral fellow in the Department of Experimental Psychology and the MRC Neuropharmacology Unit at the University of Cambridge.

Dr. Koob began his career investigating the neurobiology of emotion, particularly how the brain processes reward and stress. He subsequently applied basic research on emotions, including on the anatomical and neurochemical underpinnings of emotional function, to alcohol and drug addiction, significantly broadening knowledge of the adaptations within reward and stress neurocircuits that lead to addiction. This work has advanced our understanding of the physiological effects of alcohol and other substance use and why some people transition from use to misuse to addiction, while others do not. Dr. Koob has authored more than 650 peer-reviewed scientific papers and is a co-author of The Neurobiology of Addiction , a comprehensive textbook reviewing the most critical neurobiology of addiction research conducted over the past 50 years.

Dr. Koob is the recipient of many prestigious honors and awards for his research, mentorship, and international scientific collaboration. In 2018, Dr. Koob received the E.M. Jellinek Memorial Award for his outstanding contributions to understanding the behavioral course of addiction, In 2017, Dr. Koob was elected to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM). In 2016, the government of France awarded Dr. Koob with the insignia of Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor) for developing scientific collaborations between France and the United States. [View the video: World-class scientist Dr Koob receives the Legion of Honor .]

In addition, Dr. Koob previously received the Research Society on Alcoholism (RSA) Seixas Award for extraordinary service in advancing alcohol research; the RSA Distinguished Investigator Award; the RSA Marlatt Mentorship Award; the Daniel Efron Award for excellence in basic research and the Axelrod Mentorship Award, both from the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; the NIAAA Mark Keller Award for his lifetime contributions to our understanding of the neurobiology of alcohol use disorder; and an international prize in the field of neuronal plasticity awarded by La Fondation Ipsen.

NIAAA Directors

NIAAA’s organizational chart is available here .

NIAAA Offices manage administrative, policy and communications activities across the institute.

Office of the Director, Director: Dr. George F. Koob The Office of the Director leads the Institute by setting research and programmatic priorities and coordinating cross-cutting initiatives. The Office includes:

Office of Extramural Activities, Director: Dr. Philippe Marmillot (Acting) The Office of Extramural Activities is responsible for extramural grant and contract review, the management of chartered initial review groups and special emphasis panels, and all grants management activities. OEA also manages the Committee Management Office—responsible for advisory council activities and nominations to advisory and review panels—and provides advice to the Institute's senior leadership on matters that concern FACA (Federal Advisory Committee Act) and non-FACA meetings.

Office of Science Policy and Communications , Director: Dr. Bridget Williams-Simmons The goal of the Office of Science Policy and Communications (OSPC) is to give visibility to NIAAA-supported research and initiatives and to establish NIAAA as an authoritative source of evidence-based information on alcohol and health in support of the NIAAA mission. OSPC serves a broad range of stakeholders including NIH and NIAAA leadership, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Office of National Drug Control Policy, Congress, the research community, health professionals, advocacy organizations, the media, and patients and the public at large.

Office of Resource Management, Director: Ms. Vicki Buckley The Office of Resource Management provides administrative management support to the Institute in the areas of financial management, grants and contracts management, administrative services, and personnel operations; (2) develops administrative management policies, procedures, guidelines, and operations; (3) maintains liaison with the management staff of the Office of the Director and implements within the Institute general management policies prescribed by NIH and higher authorities.

NIAAA’s Divisions manage the Institute’s intramural and extramural basic, translational, and clinical research.

Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research , Scientific Director: Dr. David Lovinger; Clinical Director: Dr. David Goldman The Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research seeks to understand the mechanisms by which alcohol produces intoxication, dependence, and damage to vital body organs, and to develop tools to prevent and treat those biochemical and behavioral processes.

Division of Epidemiology and Prevention Research , Director: Dr. Ralph Hingson The Division of Epidemiology and Prevention Research promotes and supports applied, translational, and methodological research on the epidemiology and prevention of hazardous alcohol consumption and related behaviors, alcohol use disorder, alcohol-related mortality and morbidity, and other alcohol-related problems and consequences.

Division of Metabolism and Health Effects , Director: Dr. Kathy Jung The Division of Metabolism and Health Effects develops scientific initiatives and supports basic and translational research on the health consequences of alcohol consumption and metabolism.

Division of Neuroscience and Behavior , Director: Dr. Antonio Noronha The Division of Neuroscience and Behavior promotes research on ways in which neuronal and behavioral systems are influenced by genetic, developmental, and environmental factors in conjunction with alcohol exposure to engender alcohol use disorder.

Division of Treatment and Recovery , Director: Dr. Raye Z. Litten The Division of Treatment and Recovery stimulates and supports research to identify and improve pharmacological and behavioral treatment for alcohol use disorder, enhance methods for sustaining recovery, and increase the use of evidence-based treatments in real-world practice.

For more information about NIAAA research programs, visit the NIAAA Research webpage .

Communications and Outreach Activities

NIAAA has several major web resources to disseminate unbiased science and health information to a range of audiences and stakeholders, which include:

- NIAAA primary website

- Rethinking Drinking

- Alcohol Treatment Navigator

- NIAAA for Middle School

- NIAAA for Teens

- College Drinking Prevention

- College Alcohol Intervention Matrix (CollegeAIM )

- The Healthcare Professional's Core Resource on Alcohol

- Alcohol Research: Current Reviews

- Collaborative Research on Addiction at NIH

NIAAA also uses social media outlets to share health information, the latest science discoveries, funding and training opportunities, events, and initiatives with broader, more diverse audiences.

- Twitter: @NIAAAnews

- Facebook: @NIAAAgov

- Instagram: @NIAAAnews

- YouTube: @NIAAANIH

NIAAA also plans events and other activities with a network of liaison organizations. These organizations include research and professional societies, advocacy groups, and other interested stakeholders.

This page last reviewed on March 28, 2024

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Trusted Health Information from the National Institutes of Health

Why alcohol-use research is more important than ever

Nih's george koob talks about how addiction changes the brain and the rise in alcohol-related deaths.

Alcohol use disorder is a common but serious condition that affects how the brain functions.

George Koob, Ph.D.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) affects roughly 15 million people in the U.S. People with the condition may drink in ways that are compulsive and uncontrollable, leading to serious health issues.

"It's the addiction that everyone knows about, but no one wants to talk about," says George Koob, Ph.D., the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

As NIAAA celebrates an important milestone this year—its 50th anniversary—the institute's research is more important than ever. Like NIAAA reported earlier this year, alcohol-related health complications and deaths as a result of short-term and long-term alcohol misuse are rising in the U.S.

"Alcohol-related harms are increasing at multiple levels—from emergency department visits and hospitalizations to deaths," Dr. Koob says. He spoke about NIAAA efforts that are working to address this and how people can get help.

What has your own research focused on?

I started my career researching the science of emotion: how the brain processes things like reward and stress. Later, I translated this to alcohol and drug addiction and investigating why some people go from use to misuse to addiction, while others do not.

What are some major breakthroughs NIAAA has made in this area?

We now understand how alcohol affects the brain and why it causes symptoms of AUD . This has far-reaching implications for everything from prevention to treatment. We also understand today that AUD physically changes the brain. This has been critical in treating it as a mental disorder, like you would treat major depressive disorder.

Other breakthroughs have been made in screening and intervention, and in the medications available for treatment. All of this has led to a better understanding of how the body changes when one misuses alcohol and the proactive actions we can take to prevent alcohol misuse.

What is a misconception that people have about AUD?

Many people don't realize how common AUD is. There are seven times more people affected by AUD than opioid use disorder, for example. It doesn't discriminate against who it affects. People also don't realize that AUD is a brain disorder that actually changes how the brain functions. Severe AUD is associated with widespread injury to the brain, though some of the effects might be partially reversible.

What's next for NIAAA?

For five decades, the institute has studied how alcohol affects our health, bringing greater awareness to alcohol-related health issues and providing better options for diagnosis and treatment. Recent research has focused on areas such as the genetics of addiction, links between excessive alcohol use and mental health and other disorders, harm to long-term brain health that can be caused by adolescent alcohol use, and the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure, among others.

"We want everyone from pharmacists and nurses to addiction medicine specialists to know more about alcohol and addiction." - George Koob, Ph.D.

Currently, we are working on a number of initiatives. One is education. We want everyone from pharmacists and nurses to addiction medicine specialists to know more about alcohol and addiction. We're also working on prevention resources for middle school-aged adolescents. Other goals include understanding recovery and what treatments work best for people and why. We're also learning more about alcohol's effects on sleep and pain, and we have ongoing efforts in medication development.

Finally, we're learning more about the impact of alcohol on women and older adults. Women have begun to catch up to men in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms. Women are more susceptible to some of the negative effects that alcohol has on the body, from liver disease to certain cancers. Further, more older adults are binge drinking and this places them at greater risk of alcohol-medication interactions, falls, and health problems related to alcohol misuse.

How can someone get help?

If alcohol is negatively affecting you or someone you know, seek help from someone you respect. For example, a primary care doctor or clergy member. There are a number of online resources from NIAAA, like the NIAAA Alcohol Treatment Navigator® , an online resource to help people understand AUD treatment options and search for professionally led, evidence-based alcohol treatment nearby. There's also Rethinking Drinking SM , an interactive website to help individuals assess and change their drinking habits. Also, know that there is hope. Many people recover from AUD and lead vibrant lives.

July 16, 2020

You May Also Like

Eric Paslay doesn’t miss a note living with type 1 diabetes

Singer and songwriter Eric Paslay may have chosen a different career path than his original dream of pediatrics, but he’s...

ADHD support toolkit

If someone in your life has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), here are some ways you can offer your support. ...

ADHD across the lifespan: What it looks like in children and teens

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) affects the brain's ability to focus and control impulses and is one of the most...

Trusted health information delivered to your inbox

Enter your email below

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Volume 38 Issue 1 January 1, 2016

Drinking Across the Lifespan: Focus on Older Adults

Part of the Topic Series: Alcohol Use Among Special Populations

Kristen L. Barry, Ph.D., and Frederic C. Blow, Ph.D.

Kristen L. Barry, Ph.D., is a research professor and Frederic C. Blow is a professor, both in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

A substantial and growing number of older adults misuse alcohol. The emerging literature on the “Baby Boom” cohort, which is now reaching older adulthood, indicates that they are continuing to use alcohol at a higher rate than previous older generations. The development and refinement of techniques to address these problems and provide early intervention services will be crucial to meeting the needs of this growing population. This review provides background on the extent of alcohol misuse among older adults, including the Baby Boom cohort that has reached age 65, the consequences of misuse, physiological changes related to alcohol use, guidelines for alcohol use, methods for screening and early interventions, and treatment outcomes.

In 2010, when the leading edge of the post–World War II “Baby Boom” reached age 65, the United States began a period of increased growth in its older adult population. By 2030, it is expected that there will be 72.1 million adults age 65 or older living in the United States, almost double the 2008 population. Those older adults will represent 19.3 percent of the U.S. population, compared with 12.9 percent of the population in 2009 (Administration on Aging 2011; U.S. Census Bureau 2013). The United States is facing a “silver tsunami” that will greatly influence many segments of society, including the economy, large-scale societal programs, and the health care system. Aging research focused on “older adulthood” defines this cohort in a variety of ways, most commonly as age 50 or older, 60 or older, and 65 or older (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration [SAMHSA] 2012 a ). In this article, “older adulthood” refers to individuals who are age 65 or older, unless otherwise indicated in the text (Bartels and Naslund 2013).

The aging of the Baby Boom population will severely tax the current health care system (Bartels and Naslund 2013). There is a paucity of clinicians specializing in geriatric medicine and geriatric psychiatry. In addition, there is no single agency in the United States in charge of the mental and physical health care of this vulnerable and growing population of older adults who are more likely than previous older generations to experience problems related to mental health and alcohol use. In fact, as the Baby Boom cohort moves into older adulthood, they are likely to use more alcohol than previous generations of older adults. Misuse and abuse of alcohol, and the combination of alcohol with the use of some medications (including benzodiazepines, sedatives, and opioid analgesics), can lead to negative health outcomes. With the size of the emerging older population and their comparatively higher acceptance of alcohol and drugs, there is a growing concern that there will be a substantial increase in the number of older adults at risk for alcohol misuse and abuse (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2010; Korper and Council 2002).

Increased at-risk use and abuse of alcohol in older adults will present unique challenges in terms of recognition, interventions, and determining the most appropriate treatment options, when needed. Alcohol problems in this age group often are not recognized and, if recognized, generally are undertreated. However, older adults are more likely than younger adults to seek services from their primary and specialty care providers, which opens the door to greater recognition and assistance for those who drink above guidelines. Health care providers who work with older adults have a unique opportunity to observe and treat the repercussions of alcohol misuse, abuse, and dependence.

This review focuses on the prevalence of alcohol misuse, abuse, and dependence in older adults; guidelines for use; physiological changes in sensitivity and tolerance; and the efficacy and effectiveness of screening, interventions, and treatments in this age group.

Prevalence of Alcohol Misuse Among Older Adults

At-risk alcohol and drug use.

Over the last three decades, studies have estimated that the prevalence of at-risk and problem drinking among older adults ranges from 1 percent to 16 percent (Menninger 2002; Moore et al. 1999; SAMHSA 2004, 2007). These rates vary widely, depending on the definitions of older adults, at-risk and problem drinking, alcohol abuse/dependence, and the methodology used in obtaining samples. The 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), for example, found heavy drinking (defined as drinking 5 or more drinks on the same occasion on each of 5 or more days in the past 30 days) among 5.6 percent of 50- to 54-year-olds, 3.9 percent of 55- to 59-year-olds, 4.7 percent of 60- to 64-year-olds, and 2.1 percent of those over age 65 (SAMHSA 2014). It found even higher rates of binge drinking (defined as drinking 5 or more drinks on the same occasion on at least 1 day in the past 30 days) among these age groups; 23.0 percent of 50- to 54-year-olds, 15.9 percent of 55- to 59-year-olds, 14.1 percent of 60- to 64-year-olds, and 9.1 percent of those over 65 (SAMHSA 2014).

In addition, studies find higher rates of at-risk use and abuse among people seeking health care, because people with alcohol dependence who have at-risk use and/or are beginning to experience consequences related to that use are more likely to seek medical care (Oslin 2004). Early studies in primary care settings found that 10 to 15 percent of older patients met criteria for at-risk or problem drinking (Barry 1999), defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) as more than one-half to 1 drink per day or 7 drinks per week for women and more than 2 drinks per day or 14 drinks per week for men (Gunzerath et al. 2004; NIAAA 1995, 2007; Willenbring et al. 2009). Because patients with a previous history of problems with alcohol or other drugs are at risk for relapse, establishing a history of use can provide important clues for future problems.

Alcohol Misuse/Dependence

The rates of alcohol misuse/dependence in older adults are by far smaller than the rates of at-risk use. In 2002, over 616,000 adults age 55 and older reported meeting the criteria for alcohol dependence in the past year, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM–IV) . They represented 1.8 percent of those age 55–59, 1.5 percent of those age 60–64, and 0.5 percent of those age 65 or older (SAMHSA 2002). Later data from NSDUH showed that 780,000 older adults had alcohol abuse/dependence (SAMHSA 2012 a ). The NSDUH also has shown that illicit drug use increased from 1 percent in 2003 and 2004 to 3.9 percent in 2013 (SAMHSA 2014), suggesting that both alcohol and drug use have increased slightly in older adulthood.

Although substance dependence is less common in older adults when compared with younger adults, the mental and physical health consequences in this age group are serious (Barry and Blow 2010). Indeed, although the majority of older adults who are experiencing drinking-related problems do not meet criteria from the DSM–IV for alcohol abuse or dependence (SAMHSA 2012 b ), the diagnostic criteria that relate to the physical and emotional consequences of alcohol use may be especially important in identifying alcohol use disorders in older adults.

Impact of Physiological Changes on Alcohol Consumption

Older adults are more vulnerable to the physiological effects of alcohol than younger adults (Gargiulo et al. 2013). Alcohol consumption in amounts considered light or moderate for younger adults may have untoward health effects in older people because it is processed differently (Ferreira and Weems 2008; Gargiulo et al. 2013). In particular, as people age, liver enzymes that metabolize alcohol and other drugs are less efficient, and the central nervous system becomes more sensitive to drugs. In addition, age-related decreases in lean body mass result in a decrease in the aqueous volume of cells, which in turn increases the effective concentration of alcohol and other mood-altering chemicals in the body. Because drinking comparable amounts of alcohol produces higher and longer-lasting blood alcohol levels in older adults than in younger people, many problems common among older people, such as chronic illness and poor nutrition may be exacerbated by even small amounts of alcohol. Likewise, because older adults who drink are more likely to take alcohol-interactive medications than younger drinkers (Breslow et al. 2015), they may be at increased risk for adverse alcohol-medication interactions. Clinicians who treat older patients can assess the number of drinks per day, the number of drinking days, and any binge drinking to begin to address the health implications of an individual’s pattern of use.

Risks of Heavier Drinking in Older Adulthood

Studies analyzing data from the National Health and Retirement Study (Bobo et al. 2013) found that, although overall alcohol consumption declined with age, for a minority of individuals, consumption increased. Those who increased their consumption over time were more likely to be affluent, highly educated, male, Caucasian, unmarried, less religious, and perceive themselves to be in excellent health.

Heavy drinking or binge drinking is of particular concern in all age groups. But, as people age, binge drinking is thought to pose even higher risks for morbidity, including accidents, and mortality. To evaluate the relationship between drinking patterns and health in older adults, Holahan and colleagues (2012) studied 446 people with a mean age of 62 at the beginning of the study. Study participants were “moderate drinkers” based on NIAAA’s guidelines of drinking at least half a drink per day but no more than half a drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men (NIAAA 2007). Some also were moderate drinkers who had periods of episodic heavy drinking or binge drinking defined as drinking four or more drinks for women and five or more drinks for men on the occasion of the largest amount of drinking. Overall, the study found that moderate drinkers who engaged in episodic heavy drinking were more than twice as likely to die within 20 years compared with regular moderate drinkers.

Older adults also are at greater risk for harmful drug interactions, injury, depression, memory problems, liver disease, cognitive changes, sleep problems, cancer, and diabetes that can be related to heavier alcohol consumption (Blow and Barry 2012; Holahan et al. 2012; Moore et al. 2007; Mukamal et al. 2010; Wu and Blazer 2011). In addition, heavier drinking in this age group can significantly affect a number of other conditions in older adults (Fleming and Barry 1992), including mood disorders, sleep, and pain, as well as general health functioning (American Medical Association [AMA] 2008; Blow et al. 2002).

Not all research finds negative consequences of alcohol for older adults. In particular, one study suggests alcohol may decrease the risk of coronary heart disease. The Coro nary Heart Disease Study looked at factors, including alcohol consumption, related to the risk of coronary heart disease in older adults. In the older adult sample of more than 4,400 subjects who were free of known coronary heart disease at baseline, consumption of 14 or more drinks per week was associated with the lowest risk of coronary heart disease in the long term (Mukamal et al. 2010). Because of the risks of other disorders related to heavy alcohol use, these findings need to be placed in the context of known adverse effects of heavy drinking and the established recommended guidelines for alcohol use in older adults.

In addition to concerns regarding the misuse of alcohol alone, up to 19 percent of older Americans combine alcohol and medications in a way that can be considered misuse (NIAAA 1998 a , b ). Mixing alcohol and psychoactive medications such as benzodiazepines, sedatives, and opioid analgesics has the potential for very serious negative outcomes that prescribing physicians should discuss with older adult patients. And although the use and misuse of illicit drugs is less common in the current cohort of older adults—1.8 percent among people age 50 and over in 2002–2003 (SAMHSA 2007)—research suggests that that number is likely to increase as a result of the aging of the Baby Boom generation (Bartels and Naslund 2013).

Screening and Brief Interventions

Alcohol screening and brief interventions offer opportunities for early detection, focused motivational enhancement, and targeted encouragement to seek needed substance abuse treatment, where appropriate. The majority of older adults who misuse alcohol do not need formal specialized substance abuse treatment. Rather, many can benefit from screening and brief interventions regarding their drinking (Kuerbis et al. 2015; Pilowsky and Wu 2012).