Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.1 Overview of Nonexperimental Research

Learning objectives.

- Define nonexperimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct nonexperimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Nonexperimental Research?

Nonexperimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both.

In a sense, it is unfair to define this large and diverse set of approaches collectively by what they are not . But doing so reflects the fact that most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and nonexperimental research to be an extremely important one. This is because while experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, nonexperimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this does not mean that nonexperimental research is less important than experimental research or inferior to it in any general sense.

When to Use Nonexperimental Research

As we saw in Chapter 6 “Experimental Research” , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable and randomly assign participants to conditions or to orders of conditions. It stands to reason, therefore, that nonexperimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many ways in which this can be the case.

- The research question or hypothesis can be about a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., How accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- The research question can be about a noncausal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., Is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- The research question can be about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions (e.g., Does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- The research question can be broad and exploratory, or it can be about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., What is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and nonexperimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. If it is about a causal relationship and involves an independent variable that can be manipulated, the experimental approach is typically preferred. Otherwise, the nonexperimental approach is preferred. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, nonexperimental studies establishing that there is a relationship between watching violent television and aggressive behavior have been complemented by experimental studies confirming that the relationship is a causal one (Bushman & Huesmann, 2001). Similarly, after his original study, Milgram conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974).

Types of Nonexperimental Research

Nonexperimental research falls into three broad categories: single-variable research, correlational and quasi-experimental research, and qualitative research. First, research can be nonexperimental because it focuses on a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables. Although there is no widely shared term for this kind of research, we will call it single-variable research . Milgram’s original obedience study was nonexperimental in this way. He was primarily interested in one variable—the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate—and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of single-variable research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the research asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories.)

As these examples make clear, single-variable research can answer interesting and important questions. What it cannot do, however, is answer questions about statistical relationships between variables. This is a point that beginning researchers sometimes miss. Imagine, for example, a group of research methods students interested in the relationship between children’s being the victim of bullying and the children’s self-esteem. The first thing that is likely to occur to these researchers is to obtain a sample of middle-school students who have been bullied and then to measure their self-esteem. But this would be a single-variable study with self-esteem as the only variable. Although it would tell the researchers something about the self-esteem of children who have been bullied, it would not tell them what they really want to know, which is how the self-esteem of children who have been bullied compares with the self-esteem of children who have not. Is it lower? Is it the same? Could it even be higher? To answer this question, their sample would also have to include middle-school students who have not been bullied.

Research can also be nonexperimental because it focuses on a statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both. This kind of research takes two basic forms: correlational research and quasi-experimental research. In correlational research , the researcher measures the two variables of interest with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. A research methods student who finds out whether each of several middle-school students has been bullied and then measures each student’s self-esteem is conducting correlational research. In quasi-experimental research , the researcher manipulates an independent variable but does not randomly assign participants to conditions or orders of conditions. For example, a researcher might start an antibullying program (a kind of treatment) at one school and compare the incidence of bullying at that school with the incidence at a similar school that has no antibullying program.

The final way in which research can be nonexperimental is that it can be qualitative. The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and are analyzed using nonstatistical techniques. Rosenhan’s study of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semipublic room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256).

Internal Validity Revisited

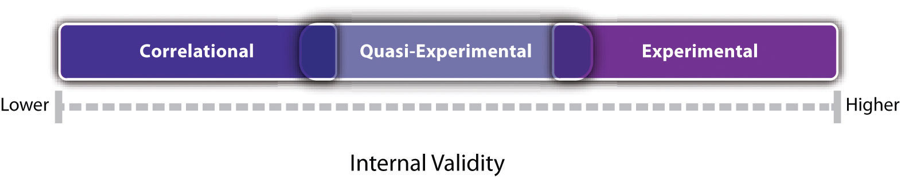

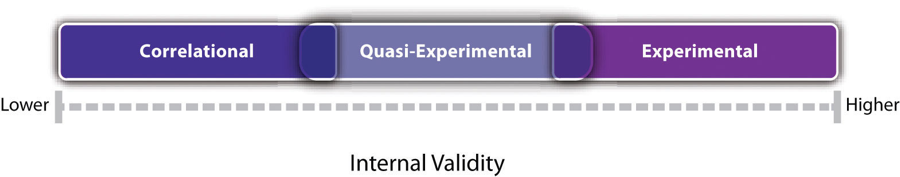

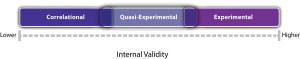

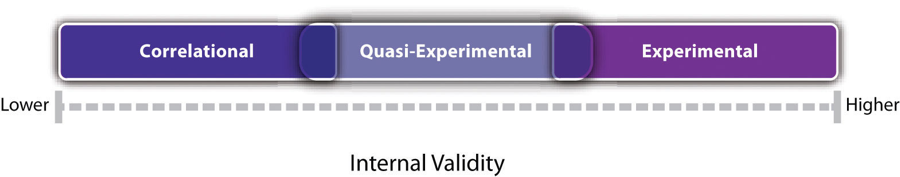

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure 7.1 shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and correlational research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest because it addresses the directionality and third-variable problems through manipulation and the control of extraneous variables through random assignment. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Correlational research is lowest because it fails to address either problem. If the average score on the dependent variable differs across levels of the independent variable, it could be that the independent variable is responsible, but there are other interpretations. In some situations, the direction of causality could be reversed. In others, there could be a third variable that is causing differences in both the independent and dependent variables. Quasi-experimental research is in the middle because the manipulation of the independent variable addresses some problems, but the lack of random assignment and experimental control fails to address others. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an antibullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” There is no directionality problem because clearly the number of bullying incidents did not determine which school got the program. However, the lack of random assignment of children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying.

Experiments are generally high in internal validity, quasi-experiments lower, and correlational studies lower still.

Notice also in Figure 7.1 that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables.

Key Takeaways

- Nonexperimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, control of extraneous variables through random assignment, or both.

- There are three broad types of nonexperimental research. Single-variable research focuses on a single variable rather than a relationship between variables. Correlational and quasi-experimental research focus on a statistical relationship but lack manipulation or random assignment. Qualitative research focuses on broader research questions, typically involves collecting large amounts of data from a small number of participants, and analyzes the data nonstatistically.

- In general, experimental research is high in internal validity, correlational research is low in internal validity, and quasi-experimental research is in between.

Discussion: For each of the following studies, decide which type of research design it is and explain why.

- A researcher conducts detailed interviews with unmarried teenage fathers to learn about how they feel and what they think about their role as fathers and summarizes their feelings in a written narrative.

- A researcher measures the impulsivity of a large sample of drivers and looks at the statistical relationship between this variable and the number of traffic tickets the drivers have received.

- A researcher randomly assigns patients with low back pain either to a treatment involving hypnosis or to a treatment involving exercise. She then measures their level of low back pain after 3 months.

- A college instructor gives weekly quizzes to students in one section of his course but no weekly quizzes to students in another section to see whether this has an effect on their test performance.

Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2001). Effects of televised violence on aggression. In D. Singer & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 223–254). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

6.1 Overview of Non-Experimental Research

Learning objectives.

- Define non-experimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct non-experimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Non-Experimental Research?

Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable. Rather than manipulating an independent variable, researchers conducting non-experimental research simply measure variables as they naturally occur (in the lab or real world).

Most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and non-experimental research to be an extremely important one. This is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, non-experimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability to make causal conclusions does not mean that non-experimental research is less important than experimental research.

When to Use Non-Experimental Research

As we saw in the last chapter , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable. It stands to reason, therefore, that non-experimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many times in which non-experimental research is preferred, including when:

- the research question or hypothesis relates to a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., How accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- the research question pertains to a non-causal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- the research question is about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions for practical or ethical reasons (e.g., does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- the research question is broad and exploratory, or is about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., what is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and non-experimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. Recall the three goals of science are to describe, to predict, and to explain. If the goal is to explain and the research question pertains to causal relationships, then the experimental approach is typically preferred. If the goal is to describe or to predict, a non-experimental approach will suffice. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, Similarly, after his original study, Milgram conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [1] .

Types of Non-Experimental Research

Non-experimental research falls into three broad categories: cross-sectional research, correlational research, and observational research.

First, cross-sectional research involves comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people. What makes this approach non-experimental is that there is no manipulation of an independent variable and no random assignment of participants to groups. Imagine, for example, that a researcher administers the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to 50 American college students and 50 Japanese college students. Although this “feels” like a between-subjects experiment, it is a cross-sectional study because the researcher did not manipulate the students’ nationalities. As another example, if we wanted to compare the memory test performance of a group of cannabis users with a group of non-users, this would be considered a cross-sectional study because for ethical and practical reasons we would not be able to randomly assign participants to the cannabis user and non-user groups. Rather we would need to compare these pre-existing groups which could introduce a selection bias (the groups may differ in other ways that affect their responses on the dependent variable). For instance, cannabis users are more likely to use more alcohol and other drugs and these differences may account for differences in the dependent variable across groups, rather than cannabis use per se.

Cross-sectional designs are commonly used by developmental psychologists who study aging and by researchers interested in sex differences. Using this design, developmental psychologists compare groups of people of different ages (e.g., young adults spanning from 18-25 years of age versus older adults spanning 60-75 years of age) on various dependent variables (e.g., memory, depression, life satisfaction). Of course, the primary limitation of using this design to study the effects of aging is that differences between the groups other than age may account for differences in the dependent variable. For instance, differences between the groups may reflect the generation that people come from (a cohort effect) rather than a direct effect of age. For this reason, longitudinal studies in which one group of people is followed as they age offer a superior means of studying the effects of aging. Once again, cross-sectional designs are also commonly used to study sex differences. Since researchers cannot practically or ethically manipulate the sex of their participants they must rely on cross-sectional designs to compare groups of men and women on different outcomes (e.g., verbal ability, substance use, depression). Using these designs researchers have discovered that men are more likely than women to suffer from substance abuse problems while women are more likely than men to suffer from depression. But, using this design it is unclear what is causing these differences. So, using this design it is unclear whether these differences are due to environmental factors like socialization or biological factors like hormones?

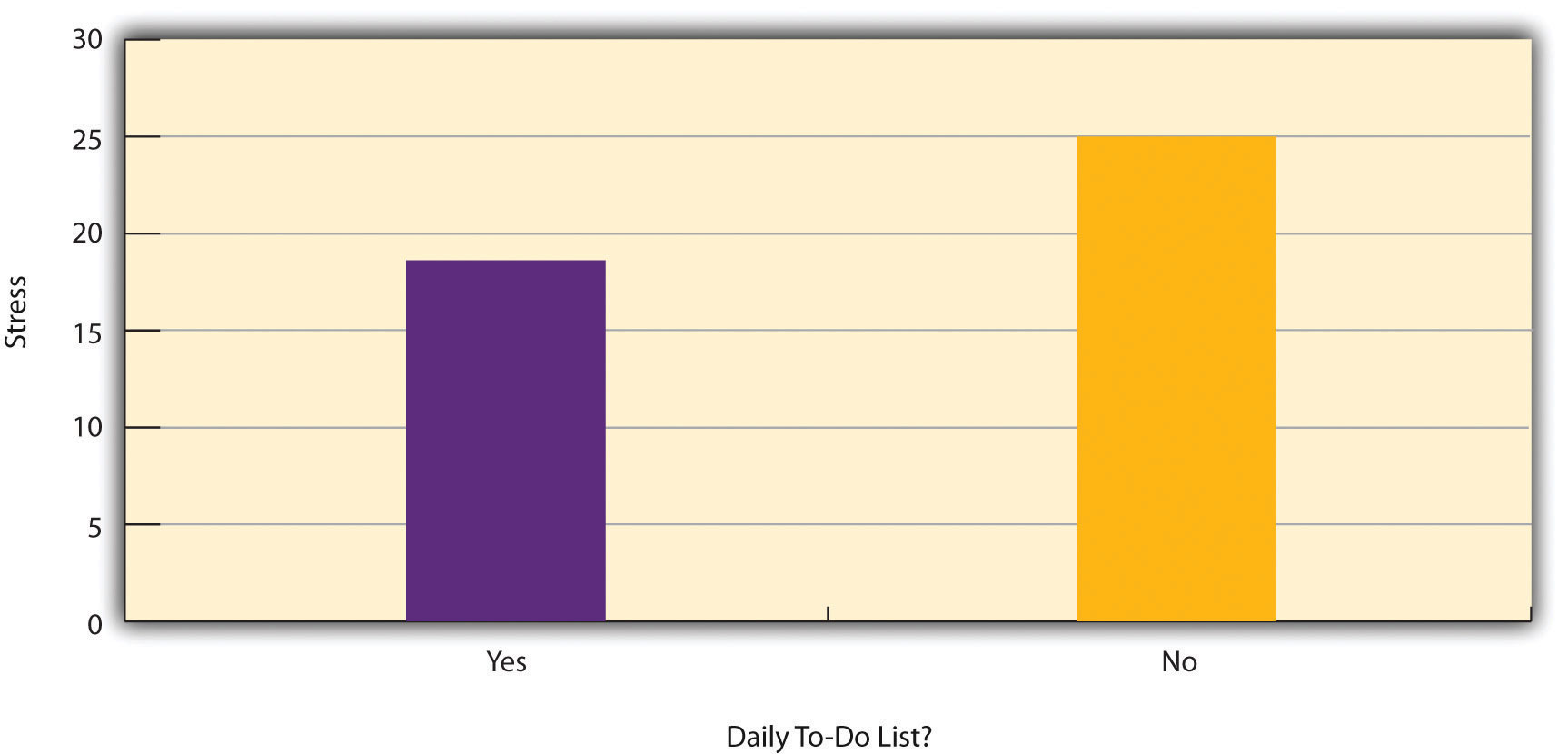

When researchers use a participant characteristic to create groups (nationality, cannabis use, age, sex), the independent variable is usually referred to as an experimenter-selected independent variable (as opposed to the experimenter-manipulated independent variables used in experimental research). Figure 6.1 shows data from a hypothetical study on the relationship between whether people make a daily list of things to do (a “to-do list”) and stress. Notice that it is unclear whether this is an experiment or a cross-sectional study because it is unclear whether the independent variable was manipulated by the researcher or simply selected by the researcher. If the researcher randomly assigned some participants to make daily to-do lists and others not to, then the independent variable was experimenter-manipulated and it is a true experiment. If the researcher simply asked participants whether they made daily to-do lists or not, then the independent variable it is experimenter-selected and the study is cross-sectional. The distinction is important because if the study was an experiment, then it could be concluded that making the daily to-do lists reduced participants’ stress. But if it was a cross-sectional study, it could only be concluded that these variables are statistically related. Perhaps being stressed has a negative effect on people’s ability to plan ahead. Or perhaps people who are more conscientious are more likely to make to-do lists and less likely to be stressed. The crucial point is that what defines a study as experimental or cross-sectional l is not the variables being studied, nor whether the variables are quantitative or categorical, nor the type of graph or statistics used to analyze the data. It is how the study is conducted.

Figure 6.1 Results of a Hypothetical Study on Whether People Who Make Daily To-Do Lists Experience Less Stress Than People Who Do Not Make Such Lists

Second, the most common type of non-experimental research conducted in Psychology is correlational research. Correlational research is considered non-experimental because it focuses on the statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable. More specifically, in correlational research , the researcher measures two continuous variables with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. As an example, a researcher interested in the relationship between self-esteem and school achievement could collect data on students’ self-esteem and their GPAs to see if the two variables are statistically related. Correlational research is very similar to cross-sectional research, and sometimes these terms are used interchangeably. The distinction that will be made in this book is that, rather than comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people as is done with cross-sectional research, correlational research involves correlating two continuous variables (groups are not formed and compared).

Third, observational research is non-experimental because it focuses on making observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything. Milgram’s original obedience study was non-experimental in this way. He was primarily interested in the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of observational research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the researchers asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories.

The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. But as you will learn in this chapter, many observational research studies are more qualitative in nature. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and therefore cannot be analyzed using statistical techniques. Rosenhan’s observational study of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semi-public room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256) [2] . Qualitative data has a separate set of analysis tools depending on the research question. For example, thematic analysis would focus on themes that emerge in the data or conversation analysis would focus on the way the words were said in an interview or focus group.

Internal Validity Revisited

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure 6.2 shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and non-experimental (correlational) research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest in internal validity because the use of manipulation (of the independent variable) and control (of extraneous variables) help to rule out alternative explanations for the observed relationships. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Non-experimental (correlational) research is lowest in internal validity because these designs fail to use manipulation or control. Quasi-experimental research (which will be described in more detail in a subsequent chapter) is in the middle because it contains some, but not all, of the features of a true experiment. For instance, it may fail to use random assignment to assign participants to groups or fail to use counterbalancing to control for potential order effects. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an anti-bullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” While a comparison is being made with a control condition, the lack of random assignment of children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying (e.g., there may be a selection effect).

Figure 6.2 Internal Validity of Correlation, Quasi-Experimental, and Experimental Studies. Experiments are generally high in internal validity, quasi-experiments lower, and correlation studies lower still.

Notice also in Figure 6.2 that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well-designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables. Internal validity is also only one of several validities that one might consider, as noted in Chapter 5.

Key Takeaways

- Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable.

- There are two broad types of non-experimental research. Correlational research that focuses on statistical relationships between variables that are measured but not manipulated, and observational research in which participants are observed and their behavior is recorded without the researcher interfering or manipulating any variables.

- In general, experimental research is high in internal validity, correlational research is low in internal validity, and quasi-experimental research is in between.

- A researcher conducts detailed interviews with unmarried teenage fathers to learn about how they feel and what they think about their role as fathers and summarizes their feelings in a written narrative.

- A researcher measures the impulsivity of a large sample of drivers and looks at the statistical relationship between this variable and the number of traffic tickets the drivers have received.

- A researcher randomly assigns patients with low back pain either to a treatment involving hypnosis or to a treatment involving exercise. She then measures their level of low back pain after 3 months.

- A college instructor gives weekly quizzes to students in one section of his course but no weekly quizzes to students in another section to see whether this has an effect on their test performance.

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 7: Nonexperimental Research

Overview of Nonexperimental Research

Learning Objectives

- Define nonexperimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct nonexperimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Nonexperimental Research?

Nonexperimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both.

In a sense, it is unfair to define this large and diverse set of approaches collectively by what they are not . But doing so reflects the fact that most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and nonexperimental research to be an extremely important one. This distinction is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, nonexperimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability does not mean that nonexperimental research is less important than experimental research or inferior to it in any general sense.

When to Use Nonexperimental Research

As we saw in Chapter 6 , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable and randomly assign participants to conditions or to orders of conditions. It stands to reason, therefore, that nonexperimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many ways in which preferring nonexperimental research can be the case.

- The research question or hypothesis can be about a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., How accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- The research question can be about a noncausal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., Is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- The research question can be about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions (e.g., Does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- The research question can be broad and exploratory, or it can be about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., What is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and nonexperimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. If it is about a causal relationship and involves an independent variable that can be manipulated, the experimental approach is typically preferred. Otherwise, the nonexperimental approach is preferred. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, nonexperimental studies establishing that there is a relationship between watching violent television and aggressive behaviour have been complemented by experimental studies confirming that the relationship is a causal one (Bushman & Huesmann, 2001) [1] . Similarly, after his original study, Milgram conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [2] .

Types of Nonexperimental Research

Nonexperimental research falls into three broad categories: single-variable research, correlational and quasi-experimental research, and qualitative research. First, research can be nonexperimental because it focuses on a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables. Although there is no widely shared term for this kind of research, we will call it single-variable research . Milgram’s original obedience study was nonexperimental in this way. He was primarily interested in one variable—the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate—and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of single-variable research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the research asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories.)

As these examples make clear, single-variable research can answer interesting and important questions. What it cannot do, however, is answer questions about statistical relationships between variables. This detail is a point that beginning researchers sometimes miss. Imagine, for example, a group of research methods students interested in the relationship between children’s being the victim of bullying and the children’s self-esteem. The first thing that is likely to occur to these researchers is to obtain a sample of middle-school students who have been bullied and then to measure their self-esteem. But this design would be a single-variable study with self-esteem as the only variable. Although it would tell the researchers something about the self-esteem of children who have been bullied, it would not tell them what they really want to know, which is how the self-esteem of children who have been bullied compares with the self-esteem of children who have not. Is it lower? Is it the same? Could it even be higher? To answer this question, their sample would also have to include middle-school students who have not been bullied thereby introducing another variable.

Research can also be nonexperimental because it focuses on a statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both. This kind of research takes two basic forms: correlational research and quasi-experimental research. In correlational research , the researcher measures the two variables of interest with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. A research methods student who finds out whether each of several middle-school students has been bullied and then measures each student’s self-esteem is conducting correlational research. In quasi-experimental research , the researcher manipulates an independent variable but does not randomly assign participants to conditions or orders of conditions. For example, a researcher might start an antibullying program (a kind of treatment) at one school and compare the incidence of bullying at that school with the incidence at a similar school that has no antibullying program.

The final way in which research can be nonexperimental is that it can be qualitative. The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and therefore cannot be analyzed using statistical techniques. Rosenhan’s study of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semipublic room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256). [3] Qualitative data has a separate set of analysis tools depending on the research question. For example, thematic analysis would focus on themes that emerge in the data or conversation analysis would focus on the way the words were said in an interview or focus group.

Internal Validity Revisited

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure 7.1 shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and correlational research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest because it addresses the directionality and third-variable problems through manipulation and the control of extraneous variables through random assignment. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Correlational research is lowest because it fails to address either problem. If the average score on the dependent variable differs across levels of the independent variable, it could be that the independent variable is responsible, but there are other interpretations. In some situations, the direction of causality could be reversed. In others, there could be a third variable that is causing differences in both the independent and dependent variables. Quasi-experimental research is in the middle because the manipulation of the independent variable addresses some problems, but the lack of random assignment and experimental control fails to address others. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an antibullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” There is no directionality problem because clearly the number of bullying incidents did not determine which school got the program. However, the lack of random assignment of children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying.

Notice also in Figure 7.1 that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables. Internal validity is also only one of several validities that one might consider, as noted in Chapter 5.

Key Takeaways

- Nonexperimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, control of extraneous variables through random assignment, or both.

- There are three broad types of nonexperimental research. Single-variable research focuses on a single variable rather than a relationship between variables. Correlational and quasi-experimental research focus on a statistical relationship but lack manipulation or random assignment. Qualitative research focuses on broader research questions, typically involves collecting large amounts of data from a small number of participants, and analyses the data nonstatistically.

- In general, experimental research is high in internal validity, correlational research is low in internal validity, and quasi-experimental research is in between.

Discussion: For each of the following studies, decide which type of research design it is and explain why.

- A researcher conducts detailed interviews with unmarried teenage fathers to learn about how they feel and what they think about their role as fathers and summarizes their feelings in a written narrative.

- A researcher measures the impulsivity of a large sample of drivers and looks at the statistical relationship between this variable and the number of traffic tickets the drivers have received.

- A researcher randomly assigns patients with low back pain either to a treatment involving hypnosis or to a treatment involving exercise. She then measures their level of low back pain after 3 months.

- A college instructor gives weekly quizzes to students in one section of his course but no weekly quizzes to students in another section to see whether this has an effect on their test performance.

- Bushman, B. J., & Huesmann, L. R. (2001). Effects of televised violence on aggression. In D. Singer & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 223–254). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

Research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable, random assignment of participants to conditions or orders of conditions, or both.

Research that focuses on a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables.

The researcher measures the two variables of interest with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them.

The researcher manipulates an independent variable but does not randomly assign participants to conditions or orders of conditions.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.1: Overview of Non-Experimental Research

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 16118

Learning Objectives

- Define non-experimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct non-experimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Non-Experimental Research?

Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable. Rather than manipulating an independent variable, researchers conducting non-experimental research simply measure variables as they naturally occur (in the lab or real world).

Most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and non-experimental research to be an extremely important one. This is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, non-experimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability to make causal conclusions does not mean that non-experimental research is less important than experimental research.

When to Use Non-Experimental Research

As we saw in the last chapter , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable. It stands to reason, therefore, that non-experimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many times in which non-experimental research is preferred, including when:

- the research question or hypothesis relates to a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., How accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- the research question pertains to a non-causal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- the research question is about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions for practical or ethical reasons (e.g., does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- the research question is broad and exploratory, or is about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., what is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and non-experimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. Recall the three goals of science are to describe, to predict, and to explain. If the goal is to explain and the research question pertains to causal relationships, then the experimental approach is typically preferred. If the goal is to describe or to predict, a non-experimental approach will suffice. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, Similarly, after his original study, Milgram conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [1] .

Types of Non-Experimental Research

Non-experimental research falls into three broad categories: cross-sectional research, correlational research, and observational research.

First, cross-sectional research involves comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people. What makes this approach non-experimental is that there is no manipulation of an independent variable and no random assignment of participants to groups. Imagine, for example, that a researcher administers the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to 50 American college students and 50 Japanese college students. Although this “feels” like a between-subjects experiment, it is a cross-sectional study because the researcher did not manipulate the students’ nationalities. As another example, if we wanted to compare the memory test performance of a group of cannabis users with a group of non-users, this would be considered a cross-sectional study because for ethical and practical reasons we would not be able to randomly assign participants to the cannabis user and non-user groups. Rather we would need to compare these pre-existing groups which could introduce a selection bias (the groups may differ in other ways that affect their responses on the dependent variable). For instance, cannabis users are more likely to use more alcohol and other drugs and these differences may account for differences in the dependent variable across groups, rather than cannabis use per se.

Cross-sectional designs are commonly used by developmental psychologists who study aging and by researchers interested in sex differences. Using this design, developmental psychologists compare groups of people of different ages (e.g., young adults spanning from 18-25 years of age versus older adults spanning 60-75 years of age) on various dependent variables (e.g., memory, depression, life satisfaction). Of course, the primary limitation of using this design to study the effects of aging is that differences between the groups other than age may account for differences in the dependent variable. For instance, differences between the groups may reflect the generation that people come from (a cohort effect) rather than a direct effect of age. For this reason, longitudinal studies in which one group of people is followed as they age offer a superior means of studying the effects of aging. Once again, cross-sectional designs are also commonly used to study sex differences. Since researchers cannot practically or ethically manipulate the sex of their participants they must rely on cross-sectional designs to compare groups of men and women on different outcomes (e.g., verbal ability, substance use, depression). Using these designs researchers have discovered that men are more likely than women to suffer from substance abuse problems while women are more likely than men to suffer from depression. But, using this design it is unclear what is causing these differences. So, using this design it is unclear whether these differences are due to environmental factors like socialization or biological factors like hormones?

When researchers use a participant characteristic to create groups (nationality, cannabis use, age, sex), the independent variable is usually referred to as an experimenter-selected independent variable (as opposed to the experimenter-manipulated independent variables used in experimental research). Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows data from a hypothetical study on the relationship between whether people make a daily list of things to do (a “to-do list”) and stress. Notice that it is unclear whether this is an experiment or a cross-sectional study because it is unclear whether the independent variable was manipulated by the researcher or simply selected by the researcher. If the researcher randomly assigned some participants to make daily to-do lists and others not to, then the independent variable was experimenter-manipulated and it is a true experiment. If the researcher simply asked participants whether they made daily to-do lists or not, then the independent variable it is experimenter-selected and the study is cross-sectional. The distinction is important because if the study was an experiment, then it could be concluded that making the daily to-do lists reduced participants’ stress. But if it was a cross-sectional study, it could only be concluded that these variables are statistically related. Perhaps being stressed has a negative effect on people’s ability to plan ahead. Or perhaps people who are more conscientious are more likely to make to-do lists and less likely to be stressed. The crucial point is that what defines a study as experimental or cross-sectional l is not the variables being studied, nor whether the variables are quantitative or categorical, nor the type of graph or statistics used to analyze the data. It is how the study is conducted.

Second, the most common type of non-experimental research conducted in Psychology is correlational research. Correlational research is considered non-experimental because it focuses on the statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable. More specifically, in correlational research , the researcher measures two continuous variables with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. As an example, a researcher interested in the relationship between self-esteem and school achievement could collect data on students’ self-esteem and their GPAs to see if the two variables are statistically related. Correlational research is very similar to cross-sectional research, and sometimes these terms are used interchangeably. The distinction that will be made in this book is that, rather than comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people as is done with cross-sectional research, correlational research involves correlating two continuous variables (groups are not formed and compared).

Third, observational research is non-experimental because it focuses on making observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything. Milgram’s original obedience study was non-experimental in this way. He was primarily interested in the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of observational research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the researchers asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories.

The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. But as you will learn in this chapter, many observational research studies are more qualitative in nature. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and therefore cannot be analyzed using statistical techniques. Rosenhan’s observational study of the experience of people in a psychiatric ward was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semi-public room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256) [2] . Qualitative data has a separate set of analysis tools depending on the research question. For example, thematic analysis would focus on themes that emerge in the data or conversation analysis would focus on the way the words were said in an interview or focus group.

Internal Validity Revisited

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and non-experimental (correlational) research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest in internal validity because the use of manipulation (of the independent variable) and control (of extraneous variables) help to rule out alternative explanations for the observed relationships. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Non-experimental (correlational) research is lowest in internal validity because these designs fail to use manipulation or control. Quasi-experimental research (which will be described in more detail in a subsequent chapter) is in the middle because it contains some, but not all, of the features of a true experiment. For instance, it may fail to use random assignment to assign participants to groups or fail to use counterbalancing to control for potential order effects. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an anti-bullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” While a comparison is being made with a control condition, the lack of random assignment of children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying (e.g., there may be a selection effect).

Notice also in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well-designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables. Internal validity is also only one of several validities that one might consider, as noted in Chapter 5.

Key Takeaways

- Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable.

- There are two broad types of non-experimental research. Correlational research that focuses on statistical relationships between variables that are measured but not manipulated, and observational research in which participants are observed and their behavior is recorded without the researcher interfering or manipulating any variables.

- In general, experimental research is high in internal validity, correlational research is low in internal validity, and quasi-experimental research is in between.

- A researcher conducts detailed interviews with unmarried teenage fathers to learn about how they feel and what they think about their role as fathers and summarizes their feelings in a written narrative.

- A researcher measures the impulsivity of a large sample of drivers and looks at the statistical relationship between this variable and the number of traffic tickets the drivers have received.

- A researcher randomly assigns patients with low back pain either to a treatment involving hypnosis or to a treatment involving exercise. She then measures their level of low back pain after 3 months.

- A college instructor gives weekly quizzes to students in one section of his course but no weekly quizzes to students in another section to see whether this has an effect on their test performance.

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Non-Experimental Research

28 Overview of Non-Experimental Research

Learning objectives.

- Define non-experimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct non-experimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Non-Experimental Research?

Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable. Rather than manipulating an independent variable, researchers conducting non-experimental research simply measure variables as they naturally occur (in the lab or real world).

Most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and non-experimental research to be an extremely important one. This is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, non-experimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability to make causal conclusions does not mean that non-experimental research is less important than experimental research. It is simply used in cases where experimental research is not able to be carried out.

When to Use Non-Experimental Research

As we saw in the last chapter , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable. It stands to reason, therefore, that non-experimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many times in which non-experimental research is preferred, including when:

- the research question or hypothesis relates to a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., how accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- the research question pertains to a non-causal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- the research question is about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions for practical or ethical reasons (e.g., does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- the research question is broad and exploratory, or is about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., what is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and non-experimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. Recall the three goals of science are to describe, to predict, and to explain. If the goal is to explain and the research question pertains to causal relationships, then the experimental approach is typically preferred. If the goal is to describe or to predict, a non-experimental approach is appropriate. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, in Milgram’s original (non-experimental) obedience study, he was primarily interested in one variable—the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate—and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. However, Milgram subsequently conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [1] .

Types of Non-Experimental Research

Non-experimental research falls into two broad categories: correlational research and observational research.

The most common type of non-experimental research conducted in psychology is correlational research. Correlational research is considered non-experimental because it focuses on the statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable. More specifically, in correlational research , the researcher measures two variables with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. As an example, a researcher interested in the relationship between self-esteem and school achievement could collect data on students’ self-esteem and their GPAs to see if the two variables are statistically related.

Observational research is non-experimental because it focuses on making observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything. Milgram’s original obedience study was non-experimental in this way. He was primarily interested in the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of observational research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the researchers asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories).

Cross-Sectional, Longitudinal, and Cross-Sequential Studies

When psychologists wish to study change over time (for example, when developmental psychologists wish to study aging) they usually take one of three non-experimental approaches: cross-sectional, longitudinal, or cross-sequential. Cross-sectional studies involve comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people (e.g., children at different stages of development). What makes this approach non-experimental is that there is no manipulation of an independent variable and no random assignment of participants to groups. Using this design, developmental psychologists compare groups of people of different ages (e.g., young adults spanning from 18-25 years of age versus older adults spanning 60-75 years of age) on various dependent variables (e.g., memory, depression, life satisfaction). Of course, the primary limitation of using this design to study the effects of aging is that differences between the groups other than age may account for differences in the dependent variable. For instance, differences between the groups may reflect the generation that people come from (a cohort effect ) rather than a direct effect of age. For this reason, longitudinal studies , in which one group of people is followed over time as they age, offer a superior means of studying the effects of aging. However, longitudinal studies are by definition more time consuming and so require a much greater investment on the part of the researcher and the participants. A third approach, known as cross-sequential studies , combines elements of both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Rather than measuring differences between people in different age groups or following the same people over a long period of time, researchers adopting this approach choose a smaller period of time during which they follow people in different age groups. For example, they might measure changes over a ten year period among participants who at the start of the study fall into the following age groups: 20 years old, 30 years old, 40 years old, 50 years old, and 60 years old. This design is advantageous because the researcher reaps the immediate benefits of being able to compare the age groups after the first assessment. Further, by following the different age groups over time they can subsequently determine whether the original differences they found across the age groups are due to true age effects or cohort effects.

The types of research we have discussed so far are all quantitative, referring to the fact that the data consist of numbers that are analyzed using statistical techniques. But as you will learn in this chapter, many observational research studies are more qualitative in nature. In qualitative research , the data are usually nonnumerical and therefore cannot be analyzed using statistical techniques. Rosenhan’s observational study of the experience of people in psychiatric wards was primarily qualitative. The data were the notes taken by the “pseudopatients”—the people pretending to have heard voices—along with their hospital records. Rosenhan’s analysis consists mainly of a written description of the experiences of the pseudopatients, supported by several concrete examples. To illustrate the hospital staff’s tendency to “depersonalize” their patients, he noted, “Upon being admitted, I and other pseudopatients took the initial physical examinations in a semi-public room, where staff members went about their own business as if we were not there” (Rosenhan, 1973, p. 256) [2] . Qualitative data has a separate set of analysis tools depending on the research question. For example, thematic analysis would focus on themes that emerge in the data or conversation analysis would focus on the way the words were said in an interview or focus group.

Internal Validity Revisited

Recall that internal validity is the extent to which the design of a study supports the conclusion that changes in the independent variable caused any observed differences in the dependent variable. Figure 6.1 shows how experimental, quasi-experimental, and non-experimental (correlational) research vary in terms of internal validity. Experimental research tends to be highest in internal validity because the use of manipulation (of the independent variable) and control (of extraneous variables) help to rule out alternative explanations for the observed relationships. If the average score on the dependent variable in an experiment differs across conditions, it is quite likely that the independent variable is responsible for that difference. Non-experimental (correlational) research is lowest in internal validity because these designs fail to use manipulation or control. Quasi-experimental research (which will be described in more detail in a subsequent chapter) falls in the middle because it contains some, but not all, of the features of a true experiment. For instance, it may fail to use random assignment to assign participants to groups or fail to use counterbalancing to control for potential order effects. Imagine, for example, that a researcher finds two similar schools, starts an anti-bullying program in one, and then finds fewer bullying incidents in that “treatment school” than in the “control school.” While a comparison is being made with a control condition, the inability to randomly assign children to schools could still mean that students in the treatment school differed from students in the control school in some other way that could explain the difference in bullying (e.g., there may be a selection effect).

Notice also in Figure 6.1 that there is some overlap in the internal validity of experiments, quasi-experiments, and correlational (non-experimental) studies. For example, a poorly designed experiment that includes many confounding variables can be lower in internal validity than a well-designed quasi-experiment with no obvious confounding variables. Internal validity is also only one of several validities that one might consider, as noted in Chapter 5.

- Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view . New York, NY: Harper & Row. ↵

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258. ↵

A research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable.

Research that is non-experimental because it focuses on the statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable.

Research that is non-experimental because it focuses on recording systemic observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything.

Studies that involve comparing two or more pre-existing groups of people (e.g., children at different stages of development).

Differences between the groups may reflect the generation that people come from rather than a direct effect of age.

Studies in which one group of people are followed over time as they age.

Studies in which researchers follow people in different age groups in a smaller period of time.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Overview of Non-Experimental Research

Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton

Learning Objectives

- Define non-experimental research, distinguish it clearly from experimental research, and give several examples.

- Explain when a researcher might choose to conduct non-experimental research as opposed to experimental research.

What Is Non-Experimental Research?

Non-experimental research is research that lacks the manipulation of an independent variable. Rather than manipulating an independent variable, researchers conducting non-experimental research simply measure variables as they naturally occur (in the lab or real world).

Most researchers in psychology consider the distinction between experimental and non-experimental research to be an extremely important one. This is because although experimental research can provide strong evidence that changes in an independent variable cause differences in a dependent variable, non-experimental research generally cannot. As we will see, however, this inability to make causal conclusions does not mean that non-experimental research is less important than experimental research. It is simply used in cases where experimental research is not able to be carried out.

When to Use Non-Experimental Research

As we saw in the last chapter , experimental research is appropriate when the researcher has a specific research question or hypothesis about a causal relationship between two variables—and it is possible, feasible, and ethical to manipulate the independent variable. It stands to reason, therefore, that non-experimental research is appropriate—even necessary—when these conditions are not met. There are many times in which non-experimental research is preferred, including when:

- the research question or hypothesis relates to a single variable rather than a statistical relationship between two variables (e.g., how accurate are people’s first impressions?).

- the research question pertains to a non-causal statistical relationship between variables (e.g., is there a correlation between verbal intelligence and mathematical intelligence?).

- the research question is about a causal relationship, but the independent variable cannot be manipulated or participants cannot be randomly assigned to conditions or orders of conditions for practical or ethical reasons (e.g., does damage to a person’s hippocampus impair the formation of long-term memory traces?).

- the research question is broad and exploratory, or is about what it is like to have a particular experience (e.g., what is it like to be a working mother diagnosed with depression?).

Again, the choice between the experimental and non-experimental approaches is generally dictated by the nature of the research question. Recall the three goals of science are to describe, to predict, and to explain. If the goal is to explain and the research question pertains to causal relationships, then the experimental approach is typically preferred. If the goal is to describe or to predict, a non-experimental approach is appropriate. But the two approaches can also be used to address the same research question in complementary ways. For example, in Milgram’s original (non-experimental) obedience study, he was primarily interested in one variable—the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate—and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. However, Milgram subsequently conducted experiments to explore the factors that affect obedience. He manipulated several independent variables, such as the distance between the experimenter and the participant, the participant and the confederate, and the location of the study (Milgram, 1974) [1] .

Types of Non-Experimental Research

Non-experimental research falls into two broad categories: correlational research and observational research.

The most common type of non-experimental research conducted in psychology is correlational research. Correlational research is considered non-experimental because it focuses on the statistical relationship between two variables but does not include the manipulation of an independent variable. More specifically, in correlational research , the researcher measures two variables with little or no attempt to control extraneous variables and then assesses the relationship between them. As an example, a researcher interested in the relationship between self-esteem and school achievement could collect data on students’ self-esteem and their GPAs to see if the two variables are statistically related.

Observational research is non-experimental because it focuses on making observations of behavior in a natural or laboratory setting without manipulating anything. Milgram’s original obedience study was non-experimental in this way. He was primarily interested in the extent to which participants obeyed the researcher when he told them to shock the confederate and he observed all participants performing the same task under the same conditions. The study by Loftus and Pickrell described at the beginning of this chapter is also a good example of observational research. The variable was whether participants “remembered” having experienced mildly traumatic childhood events (e.g., getting lost in a shopping mall) that they had not actually experienced but that the researchers asked them about repeatedly. In this particular study, nearly a third of the participants “remembered” at least one event. (As with Milgram’s original study, this study inspired several later experiments on the factors that affect false memories).

Cross-Sectional, Longitudinal, and Cross-Sequential Studies