An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Adv Pract Oncol

- v.12(4); 2021 May

Quality Improvement Projects and Clinical Research Studies

Every day, I witness firsthand the amazing things that advanced practitioners and nurse scientists accomplish. Through the conduct of quality improvement (QI) projects and clinical research studies, advanced practitioners and nurse scientists have the opportunity to contribute exponentially not only to their organizations, but also towards personal and professional growth.

Recently, the associate editors and staff at JADPRO convened to discuss the types of articles our readership may be interested in. Since we at JADPRO believe that QI projects and clinical research studies are highly valuable methods to improve clinical processes or seek answers to questions, you will see that we have highlighted various QI and research projects within the Research and Scholarship column of this and future issues. There have also been articles published in JADPRO about QI and research ( Gillespie, 2018 ; Kurtin & Taher, 2020 ). As a refresher, let’s explore the differences between a QI project and clinical research.

Quality Improvement

As leaders in health care, advanced practitioners often conduct QI projects to improve their internal processes or streamline clinical workflow. These QI projects use a multidisciplinary team comprising a team leader as well as nurses, PAs, pharmacists, physicians, social workers, and program administrators to address important questions that impact patients. Since QI projects use strategic processes and methods to analyze existing data and all patients participate, institutional review board (IRB) approval is usually not needed. Common frameworks, such as Lean, Six Sigma, and the Model for Improvement can be used. An attractive aspect of QI projects is that these are generally quicker to conduct and report on than clinical research, and often with quantifiable benefits to a large group within a system ( Table 1 ).

Clinical Research

Conducting clinical research through an IRB-approved study is another area in which advanced practitioners and nurse scientists gain new knowledge and contribute to scientific evidence-based practice. Research is intended for specific groups of patients who are protected from harm through the IRB and ethical principles. Research can potentially benefit a larger group, but benefits to participants are often unknown during the study period.

Clinical research poses many challenges at various stages of what can be a lengthy process. First, the researcher conducts a review of the literature to identify gaps in existing knowledge. Then, the researcher must be diligent in their self-reflection (is this phenomenon worth studying?) and in developing the sampling and statistical methods to ensure validity and reliability of the research ( Higgins & Straub, 2006 ). A team of additional researchers and support staff is integral to completing the research and disseminating findings. A well-designed clinical trial is worth the time and effort it takes to answer important clinical questions.

So, as an advanced practitioner, would a QI project be better to conduct than a clinical research study? That depends. A QI project uses a specific process, measures, and existing data to improve outcomes in a specific group. A research study uses an IRB-approved study protocol, strategic methods, and generates new data to hopefully benefit a larger group.

In This Issue

Both QI projects and clinical research can provide evidence to base one’s interventions on and enhance the lives of patients in one way or another. I hope you will agree that this issue is filled with valuable information on a wide range of topics. In the following pages, you will learn about findings of a QI project to integrate palliative care into ambulatory oncology. In a phenomenological study, Carrasco explores patient communication preferences around cancer symptom reporting during cancer treatment.

We have two excellent review articles for you as well. Rogers and colleagues review the management of hematologic adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors, and Lemke reviews the evidence for use of ginseng in the management of cancer-related fatigue. In Grand Rounds, Flagg and Pierce share an interesting case of essential thrombocythemia in a 15-year-old, with valuable considerations in the pediatric population. May and colleagues review practical considerations for integrating biosimilars into clinical practice, and Moore and Thompson review BTK inhibitors in B-cell malignancies.

- Higgins P. A., & Straub A. J. (2006). Understanding the error of our ways: Mapping the concepts of validity and reliability . Nursing Outlook , 54 ( 1 ), 23–29. 10.1016/j.outlook.2004.12.004 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gillespie T. W. (2018). Do the right study: Quality improvement projects and human subject research—both valuable, simply different . Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology , 9 ( 5 ), 471–473. 10.6004/jadpro.2018.9.5.1 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kurtin S. E., & Taher R. (2020). Clinical trial design and drug approval in oncology: A primer for the advanced practitioner in oncology . Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology , 11 ( 7 ), 736–751. 10.6004/jadpro.2020.11.7.7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Quality Improvement Projects and Clinical Research Studies

- PMID: 34123473

- PMCID: PMC8163249

- DOI: 10.6004/jadpro.2021.12.4.1

Publication types

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to get started in...

How to get started in quality improvement

Linked opinion.

The benefits of QI are numerous and the challenges worth overcoming

Read the full collection

- Related content

- Peer review

- Bryan Jones , improvement fellow 1 ,

- Emma Vaux , consultant nephrologist 2 ,

- Anna Olsson-Brown , research fellow 3

- 1 The Health Foundation, London, UK

- 2 Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust. Reading, UK

- 3 Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, The Institute of Translational Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

- Correspondence to B Jones bryan.jones{at}health.org.uk

What you need to know

Participation in quality improvement can help clinicians and trainees improve care together and develop important professional skills

Effective quality improvement relies on collaborative working with colleagues and patients and the use of a structured method

Enthusiasm, perseverance, good project management skills, and a willingness to explain your project to others and seek their support are key skills

Quality improvement ( box 1 ) is a core component of many undergraduate and postgraduate curriculums. 1 2 3 4 5 Numerous healthcare organisations, 6 professional regulators, 7 and policy makers 8 recognise the benefits of training clinicians in quality improvement.

Defining quality improvement 1

Quality improvement aims to make a difference to patients by improving safety, effectiveness, and experience of care by:

Using understanding of our complex healthcare environment

Applying a systematic approach

Designing, testing, and implementing changes using real time measurement for improvement

Engaging in quality improvement enables clinicians to acquire, assimilate, and apply important professional capabilities 7 such as managing complexity and training in human factors. 1 For clinical trainees, it is a chance to improve care 9 ; develop leadership, presentation, and time management skills to help their career development 10 ; and build relationships with colleagues in organisations that they have recently joined. 11 For more experienced clinicians, it is an opportunity to address longstanding concerns about the way in which care processes and systems are delivered, and to strengthen their leadership for improvement skills. 12

The benefits to patients, clinicians, and healthcare providers of engaging in quality improvement are considerable, but there are many challenges involved in designing, delivering, and sustaining an improvement intervention. These range from persuading colleagues that there is a problem that needs to be tackled, through to keeping them engaged once the intervention is up and running as other clinical priorities compete for their attention. 13 You are also likely to have competing priorities and will need support to make time for quality improvement. The organisational culture, such as the extent to which clinicians are able to question existing practice and try new ideas, 14 15 16 also has an important bearing on the success of the intervention.

This article describes the skills, knowledge, and support needed to get started in quality improvement and deliver effective interventions.

What skills do you need?

Enthusiasm, optimism, curiosity, and perseverance are critical in getting started and then in helping you to deal with the challenges you will inevitably face on your improvement journey.

Relational skills are also vital. At its best quality improvement is a team activity. The ability to collaborate with different people, including patients, is vital for a project to be successful. 17 18 You need to be willing to reach out to groups of people that you may not have worked with before, and to value their ideas. 19 No one person has the skills or knowledge to come up with the solution to a problem on their own.

Learning how systems work and how to manage complexity is another core skill. 20 An ability to translate quality improvement approaches and methods into practice ( box 2 ), coupled with good project and time management skills, will help you design and implement a robust project plan. 27

Quality improvement approaches

Healthcare organisations use a range of improvement methods, 21 22 such as the Model for Improvement , where changes are tested in small cycles that involve planning, doing, studying, and acting (PDSA), 23 and Lean , which focuses on continually improving processes by removing waste, duplication, and non-value adding steps. 24 To be effective, such methods need to be applied consistently and rigorously, with due regard to the context. 25 In using PDSA cycles, for example, it is vital that teams build in sufficient time for planning and reflection, and do not focus primarily on the “doing.” 26

Equally important is an understanding of the measurement for improvement model, which involves the gradual refinement of your intervention based on repeated tests of change. The aim is to discover how to make your intervention work in your setting, rather than to prove it works, so useful data, not perfect data, are needed. 28 29 Some experience of data collection and analysis methods (including statistical analysis tools such as run charts and statistical process control) is useful, but these will develop with increasing experience. 30 31

Most importantly, you need to enjoy the experience. It is rare that a clinician can institute real, tangible change, but with quality improvement this is a real possibility, which is both empowering and satisfying. Finally, don’t worry about what you don’t know. You will learn by doing. Many skills needed to implement successful quality improvement will be developed as you go; this is a fundamental feature of quality improvement.

How do you get started?

The first step is to recruit your improvement team. Start with colleagues and patients, 32 but also try to bring in people from other professions, including non-clinical staff. You need a blend of skills and perspectives in your team. Find a colleague experienced in quality improvement who is willing to mentor or supervise you.

Next, identify a problem collaboratively with your team. Use data to help with this (eg, clinical audits, registries of data on patients’ experiences and outcomes, and learning from incidents and complaints) ( box 3 ). Take time to understand what might be causing the problem. There are different techniques to help you (process mapping, five whys, appreciative inquiry). 35 36 37 Think about the contextual factors that are contributing to the problem (eg, the structure, culture, politics, capabilities and resources of your organisation).

Clinical audit and quality improvement

Quality improvement is an umbrella term under which many approaches sit, clinical audit being one. 33 Clinical audit is commonly used by trainees to assess clinical effectiveness. Confusion of audit as both a term for assurance and improvement has perhaps limited its potential, with many audits ending at the data collection stage and failing to lead to improvement interventions. Learning from big datasets such as the National Clinical Audits in the UK is beginning to shift the focus to a quality improvement approach that focuses on identifying and understanding unwanted variation in the local context; developing and testing possible solutions, and moving from one-off change to multiple cycles of change. 34

Next, develop your aim using the SMART framework: Specific (S), Measurable (M), Achievable (A), Realistic (R), and Timely (T). 38 This allows you to assess the scale of the intervention and to pare it down if your original idea is too ambitious. Aligning your improvement aim with the priorities of the organisation where you work will help you to get management and executive support. 39

Having done this, map those stakeholders who might be affected by your intervention and work out which ones you need to approach, and how to sell it to them. 40 Take the time to talk to them. It will be appreciated and increases the likelihood of buy in, without which your quality improvement project is likely to fail irrespective of how good your idea is. You need to be clear in your own mind about the reasons you think it is important. Developing an “elevator pitch” based on your aims is a useful technique to persuade others, 38 remembering different people are hooked in for different reasons.

The intervention will not be perfect first time. Expect a series of iterative changes in response to false starts and obstacles. Measuring the impact of your intervention will enable you to refine it. 28 Time invested in all these aspects will improve your chances of success.

Right from the start, think about how improvement will be embedded. Attention to sustainability will mean that when you move to your next job your improvement efforts, and those of others, and the impact you have collectively achieved will not be lost. 41 42

What support is needed?

You need support from both your organisation and experienced colleagues to translate your skills into practice. Here are some steps you can take to help you make the most of your skills:

Find the mentor or supervisor who will help identify and support opportunities for you. Signposting and introduction to those in an organisation who will help influence (and may hinder) your quality improvement project is invaluable

Use planning and reporting tools to help manage your project, such as those in NHS Improvement’s project management framework 27

Identify if your local quality improvement or clinical audit team may be a source of support and useful development resource for you rather than just a place to register a project. Most want to support you.

Determine how you might access (or develop your own) local peer to peer support networks, coaching, and wider improvement networks (eg, NHS networks; Q network 43 44 )

Use quality improvement e-learning platforms such as those provided by Health Education England or NHS Education for Scotland to build your knowledge 45 46

Learn through feedback and assessment of your project (eg, via the QIPAT tool 47 or a multi-source feedback tool. 48 49

Quality improvement approaches are still relatively new in the education of healthcare professionals. Quality improvement can give clinicians a more productive, empowering, and educational experience. Quality improvement projects allow clinicians, working within a team, to identify an issue and implement interventions that can result in true improvements in quality. Projects can be undertaken in fields that interest clinicians and give them transferable skills in communication, leadership, project management, team working, and clinical governance. Done well, quality improvement is a highly beneficial, positive process which enables clinicians to deliver true change for the benefit of themselves, their organisations, and their patients.

Quality improvement in action: three doctors and a medical student talk about the challenges and practicalities of quality improvement

This box contains four interviews by Laura Nunez-Mulder with people who have experience in quality improvement.

Alex Thompson, medical student at the University of Cambridge, is in the early stages of his first quality improvement project

We are aiming to improve identification and early diagnosis of aortic dissections in our hospital. Our supervising consultant suspects that the threshold for organising computed tomography angiography for a suspected aortic dissection is too high, so to start with, my student colleague and I are finding out what proportion of CT angiograms result in a diagnosis of aortic dissection.

I fit the project around my studies by working on it in small chunks here and there. You have to be very self motivated to see a project through to the end.

Anna Olsson-Brown, research fellow at the University of Liverpool, engaged in quality improvement in her F1 year, and has since supported junior doctors to do the same. This extract is adapted from her BMJ Opinion piece ( https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/ )

Working in the emergency department after my F1 job in oncology, I noticed that the guidelines on neutropenic sepsis antibiotics were relatively unknown and even less frequently implemented. A colleague and I devised a neutropenic sepsis pathway for oncology patients in the emergency department including an alert label for blood tests. The pathway ran for six months and there was some initial improvement, but the benefit was not sustained after we left the department.

As an ST3, I mentored a junior doctor whose quality improvement project led to the introduction of a syringe driver prescription sticker that continues to be used to this day.

My top tips for those supporting trainees in quality improvement:

Make sure the project is sufficiently narrow to enable timely delivery

Ensure regular evaluation to assess impact

Support trainees to implement sustainable pathways that do not require their ongoing input.

Amar Puttanna, consultant in diabetes and endocrinology at Good Hope Hospital, describes a project he carried out as a chief registrar of the Royal College of Physicians

The project of which I am proudest is a referral service we launched to review medication for patients with diabetes and dementia. We worked with practitioners on the older adult care ward, the acute medical unit, the frailty service, and the IT teams, and we promoted the project in newsletters at the trust and the Royal College of Physicians.

The success of the project depended on continuous promotion to raise awareness of the service because junior doctors move on frequently. Activity in our project reduced after I left the trust, though it is still ongoing and won a Quality in Care Award in November 2018.

Though this project was a success, not everything works. But even the projects that fail contain valuable lessons.

Mark Taubert, consultant in palliative medicine and honorary senior lecturer for Cardiff University School of Medicine, launched the TalkCPR project

Speaking to people with expertise in quality improvement helped me to narrow my focus to one question: “Can videos be used to inform both staff and patients/carers about cardiopulmonary resuscitation and its risks in palliative illness?” With my team I created and evaluated TalkCPR, an online resource that has gone on to win awards (talkcpr.wales).

The most challenging aspect was figuring out which tools might get the right information from any data I collected. I enrolled on a Silver Improving Quality Together course and joined the Welsh Bevan Commission, where I learned useful techniques such as multiple PDSA (plan, do, study, act) cycles, driver diagrams, and fishbone diagrams.

Education into practice

In designing your next quality improvement project:

What will you do to ensure that you understand the problem you are trying to solve?

How will you involve your colleagues and patients in your project and gain the support of managers and senior staff?

What steps will you take right from the start to ensure that any improvements made are sustained?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article

The authors have drawn on their experience both in partnering with patients in the design and delivery of multiple quality improvement activities and in participating in the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges Training for Better Outcomes Task and Finish Group 1 in which patients were involved at every step. Patients were not directly involved in writing this article.

Sources and selection material

Evidence for this article was based on references drawn from authors’ academic experience in this area, guidance from organisations involved in supporting quality improvement work in practice such as NHS Improvement, The Health Foundation, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and authors’ experience of working to support clinical trainees to undertake quality improvement.

Competing interests: The BMJ has judged that there are no disqualifying financial ties to commercial companies.

The authors declare the following other interests: none.

Further details of The BMJ policy on financial interests is here: https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-authors/forms-policies-and-checklists/declaration-competing-interests

Contributors: BJ produced the initial outline after discussions with EV and AOB. AO-B produced a first complete draft, which EV reworked and expanded. BJ then edited and finalised the text, which was approved by EV and AO-B. The revisions in the resubmitted version were drafted by BJ and edited and approved by EV and AO-B. BJ is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Provenance and peer review: This article is part of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on ideas generated by a joint editorial group with members from the Health Foundation and The BMJ, including a patient/carer. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication. Open access fees and The BMJ’s quality improvement editor post are funded by the Health Foundation.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

- ↵ Academy of Medical Royal Colleges (AoMRC). Quality improvement: training for better outcomes. March 2016. http://www.aomrc.org.uk/reports-guidance/quality-improvement-training-better-outcomes/

- Bethune R ,

- Woodhead P ,

- Van Hamel C ,

- Teigland CL ,

- Blasiak RC ,

- Wilson LA ,

- Meyerhoff KL ,

- ↵ Jones B, Woodhead T. Building the foundations for improvement—how five UK trusts built quality improvement capability at scale within their organisations. The Health Foundation. February 2015. https://www.health.org.uk/publication/building-foundations-improvement

- ↵ General Medical Council (GMC). Generic professional capabilities framework. May 2017. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/generic-professional-capabilities-framework-0817_pdf-70417127.pdf

- ↵ NHS improvement (NHSI). Developing people—improving care A national framework for action on improvement and leadership development in NHS-funded services. December 2016. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/developing-people-improving-care/

- ↵ The Health Foundation. Involving junior doctors in quality improvement: evidence scan. September 2011. https://www.health.org.uk/publication/involving-junior-doctors-quality-improvement

- ↵ Zarkali A, Acquaah F, Donaghy G, et al. Trainees leading quality improvement. A trainee doctor’s perspective on incorporating quality improvement in postgraduate medical training. Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management. March 2016. https://www.fmlm.ac.uk/sites/default/files/content/resources/attachments/FMLM%20TSG%20Think%20Tank%20Trainees%20leading%20quality%20improvement.pdf

- Hillman T ,

- ↵ Bohmer R. The instrumental value of medical leadership: Engaging doctors in improving services. The King’s Fund. 2012. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/instrumental-value-medical-leadership-richard-bohmer-leadership-review2012-paper.pdf

- ↵ Dixon-Woods M, McNicol S, Martin G. Ten challenges in improving quality in healthcare: lessons from the Health Foundation's programme evaluations and relevant literature. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;1e9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000760 OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- Brault MA ,

- Linnander EL ,

- Carroll JS ,

- Edmondson AC

- Mannion R ,

- Richter A ,

- McPherson K ,

- Headrick L ,

- ↵ Lucas B, Nacer H. The habits of an improver. Thinking about learning for improvement in health care. The Health Foundation. October 2015. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/TheHabitsOfAnImprover.pdf

- Greenhalgh T

- ↵ The Health Foundation. Quality Improvement made simple: what everyone should know about quality improvement. The Health Foundation. 2013. https://www.health.org.uk/publication/quality-improvement-made-simple

- ↵ Boaden R, Harvey G, Moxham C, Proudlove N. Quality improvement: theory and practice in healthcare. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. 2008. https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/publication/quality-improvement-theory-practice-in-healthcare/

- ↵ Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). IHI resources: How to improve. IHI. 2018 http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx

- ↵ Lean Enterprise Institute. What is lean? Lean Enterprise Institute. 2018. https://www.lean.org/WhatsLean/

- ↵ Bate P, Robert G, Fulop N, Øvretveit J, Dixon-Woods M. Perspectives on context. A selection of essays considering the role of context in successful quality improvement. The Health Foundation. 2014. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/PerspectivesOnContext_fullversion.pdf

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools. Project management an overview. September 2017. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/project-management-overview/

- ↵ Clarke J, Davidge M, James L. The how-to guide for measurement for improvement. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2009. https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/How-to-Guide-for-Measurement-for-Improvement.pdf

- Nelson EC ,

- Splaine ME ,

- Batalden PB ,

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools. Run charts. January 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/run-charts/

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools. Statistical process control tool. May 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/statistical-process-control-tool/

- Cornwell J ,

- Purushotham A ,

- Sturmey G ,

- Burgess R ,

- ↵ Royal College of Physicians. Unlocking the potential. Supporting doctors to use national clinical audit to drive improvement. April 2018. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/unlocking-potential-supporting-doctors-use-national-clinical-audit-drive

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools: conventional process mapping. January 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/process-mapping-conventional-model/

- ↵ Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) 5 Whys: Finding the root cause. IHI tool. 2018. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/5-Whys-Finding-the-Root-Cause.aspx

- Scottish Social Services Council (SSSC) Appreciative Inquiry Resource Pack

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools: Developing your aims statement. January 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/aims-statement-development/

- Pannick S ,

- Sevdalis N ,

- Athanasiou T

- ↵ Improvement NHS. (NHSI) Quality, Service Improvement and Redesign Tools: Stakeholder Analysis. January 2018. https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2169/stakeholder-analysis.pdf

- ↵ Maher L, Gustafson D, Evans A. Sustainability model and guide. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. February 2010. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160805122935/http:/www.nhsiq.nhs.uk/media/2757778/nhs_sustainability_model_-_february_2010_1_.pdf

- Networks NHS

- ↵ Community Q. The Health Foundation. 2018. https://q.health.org.uk/

- ↵ Health Education England. e-learning for healthcare. https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/research-audit-and-quality-improvement/

- ↵ Scotland Quality Improvement Hub NHS. QI e-learning. http://www.qihub.scot.nhs.uk/education-and-learning-xx/qi-e-learning.aspx

- ↵ Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Quality Improvement Assessment Tool (QIPAT). 2017. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/documents/may-2012-quality-improvement-assessment-tool-qipat

- ↵ Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Quality improvement assessment tool. May 2017. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/documents/may-2012-quality-improvement-assessment-tool-qipat

- ↵ Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board. Multi-source feedback. August 2014. https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/documents/multi-source-feedback-august-2014 .

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 02 March 2020

Costs and economic evaluations of Quality Improvement Collaboratives in healthcare: a systematic review

- Lenore de la Perrelle ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9239-0728 1 , 2 ,

- Gorjana Radisic 1 , 2 ,

- Monica Cations 1 , 2 ,

- Billingsley Kaambwa 3 ,

- Gaery Barbery 4 &

- Kate Laver 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 20 , Article number: 155 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

35 Citations

15 Altmetric

Metrics details

In increasingly constrained healthcare budgets worldwide, efforts to improve quality and reduce costs are vital. Quality Improvement Collaboratives (QICs) are often used in healthcare settings to implement proven clinical interventions within local and national programs. The cost of this method of implementation, however, is cited as a barrier to use. This systematic review aims to identify and describe studies reporting on costs and cost-effectiveness of QICs when used to implement clinical guidelines in healthcare.

Multiple databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, EconLit and ProQuest) were searched for economic evaluations or cost studies of QICs in healthcare. Studies were included if they reported on economic evaluations or costs of QICs. Two authors independently reviewed citations and full text papers. Key characteristics of eligible studies were extracted, and their quality assessed against the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS). Evers CHEC-List was used for full economic evaluations. Cost-effectiveness findings were interpreted through the Johanna Briggs Institute ‘three by three dominance matrix tool’ to guide conclusions. Currencies were converted to United States dollars for 2018 using OECD and World Bank databases.

Few studies reported on costs or economic evaluations of QICs despite their use in healthcare. Eight studies across multiple healthcare settings in acute and long-term care, community addiction treatment and chronic disease management were included. Five were considered good quality and favoured the establishment of QICs as cost-effective implementation methods. The cost savings to the healthcare setting identified in these studies outweighed the cost of the collaborative itself.

Conclusions

Potential cost savings to the health care system in both acute and chronic conditions may be possible by applying QICs at scale. However, variations in effectiveness, costs and elements of the method within studies, indicated that caution is needed. Consistent identification of costs and description of the elements applied in QICs would better inform decisions for their use and may reduce perceived barriers. Lack of studies with negative findings may have been due to publication bias. Future research should include economic evaluations with societal perspectives of costs and savings and the cost-effectiveness of elements of QICs.

Trial registration

PROSPERO registration number: CRD42018107417 .

Peer Review reports

A significant challenge facing health care settings is how to implement proven clinical interventions in practice in a cost-effective manner [ 1 ]. Scarce resources, including lack of time and staff are often cited as barriers to implementation [ 2 , 3 ]. A recent review of medical research shows health savings from broad research translation, significantly outweigh the cost of delivering them [ 3 ] but the field of economic evaluation of implementation strategies is still developing [ 4 ]. Decisions to use particular implementation methods can be better informed by identifying cost-benefits of methods in addition to health outcomes [ 5 , 6 ].

Methods of knowledge translation have been tested with mixed results. For example, clinical practice guidelines aim to translate research into practice and improve the quality of care and health outcomes for people. However, studies have shown that the dissemination of guidelines alone is insufficient to effect change in routine clinical practice [ 7 ]. Education and training of clinicians, the development of champions of change in organisations, and audit and feedback mechanisms have been trialled to improve adherence to guidelines [ 8 ]. However, these strategies lead to only modest effects in quality improvement [ 8 ]. A recent review found that while multifaceted strategies are more effective, costs associated with components were difficult to discern and cost-effectiveness was not explicitly evaluated [ 9 ]. Knowledge translation approaches which are tailored to an organisation can be successful but may lack transferability to other settings [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. QICs have been adapted from manufacturing industry [ 13 ] for use across multiple settings by the US Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) [ 14 ]. A QIC is a multifaceted approach to implementation of evidence-based practices, clinical guidelines or improved methods for quality and safety. Typically, they draw participants from multiple healthcare organisations to learn, apply and share improvement methods over a year or more. Teams are supported by experts who coach participants to test strategies adapted to their own setting. By collaborating, participants learn more effectively, spread improvement ideas and benchmark their progress against other organisations [ 14 , 15 ]. Common components of QICs include face to face training sessions focussing on healthcare improvement and quality improvement methods, telephone meetings, feedback and the use of process improvement methods [ 13 ]. QICs have been used in healthcare systems in several countries to improve implementation outcomes [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. They are adaptable within complex healthcare systems and offer a way to scale up implementation across many different organisations. However, inconsistent results, multiple elements and perceived cost of establishing, conducting and sustaining a collaborative are barriers to their use [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. Wells and colleagues recently identified 64 QICs reporting effectiveness measures that met their inclusion criteria [ 15 ]. They found that 73% of these collaboratives reported significant results in diverse settings such as hospitals, health clinics and nursing homes. Improvement was associated with targeted clinical practice related to infection control, management of chronic conditions or prevention of falls, wounds or pain management [ 15 ]. While these improvements were associated with cost savings, only four studies reported on cost-effectiveness outcomes [ 15 ]. They identified gaps in design, reporting and assessment of costs which limited the information on cost-effectiveness. The costs of establishing a QIC can be significant, including personnel to recruit and coordinate activities, development of materials and education, the time spent by all participants involved in the collaborative and expenses associated with face to face meetings [ 17 ].

With increasing pressure on the healthcare system to deliver evidence-based practice with scarce resources, there is a need to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of healthcare improvement and knowledge translation strategies. Economic evaluation can assess implementation strategies to guide decisions about the choice of strategy providing value for money.

The aim of this systematic review was to identify and describe studies that report on the costs and cost-effectiveness of QICs to inform strategies to implement clinical guideline recommendations in healthcare.

The protocol for this systematic review was developed in advance and was registered with PROSPERO on 7 September 2018; registration number CRD42018107417.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in this review if they reported on initiatives that comprised healthcare clinicians across teams, professions, or organisations involved in a QIC or a quality improvement team with the aim of improving practice over time. Quality improvement teams were included if they included the most common components of QICs as identified by Nadeem et al. [ 13 ]. Studies were included if the collaboratives used multi-modal interventions, such as training, developing implementation plans, trying out a practice improvement, seeking advice from experts and people with lived experience and reviewing plans over time to improve practice [ 15 ]. We included quantitative studies that used full economic evaluation (i.e. cost-effectiveness, cost-utility analysis, cost-benefit analysis, cost-consequences analysis); partial economic evaluations (i.e. cost analyses, cost descriptions, cost outcome descriptions, cost minimisation studies); and randomised trials reporting estimates of resource use or costs associated with implementation or improvement. We excluded systematic reviews, study protocols, conference proceedings, editorials and commentary papers, effectiveness analyses with no analysis of costs, burden of disease studies, and cost of illness studies. The primary outcome of interest was the cost-effectiveness or cost-benefit of the use of elements of QICs to implement improvement in healthcare or adherence to clinical guidelines. A secondary outcome was costs associated with QICs.

Search strategy and study selection

Five electronic databases were searched on 19 November 2018 (CINAHL, Medline, PsycINFO, EconLit, ProQuest (Health and Medicine: Social Sciences subsets only)). Embase was searched on 20 August 2019. Websites of large organisations interested in healthcare improvement such as the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI, USA) and government bodies such as National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), National Health Services and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) and the European Network of Health Economic Evaluation Databases were searched for grey literature. Reference lists of included studies were scanned for potentially eligible studies. Studies were limited to English language, but no time limits were imposed on the search strategies. Research librarians with expertise in systematic reviews assisted with the development of the search strategies. The search strategy was developed for MEDLINE using medical subject search headings (MeSH) and text words and then adapted for use with the other databases. The strategy combined terms relating to quality improvement, collaborative, guidelines implementation and cost, cost-benefit or economic analysis. The search strategy for MEDLINE is attached (Additional file 1 ). Results are reported per the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 20 ].

Two authors (LdlP and GR) independently screened titles and abstracts based on the inclusion criteria detailed in the review protocol. Full texts of studies identified by abstract and title screen as having met the inclusion criteria were obtained and reviewed independently (LdlP and GR). Differences between reviewer’s results were resolved by discussion and when necessary in consultation with a third review author (MC) .

Data extraction

One author (LdlP) extracted data using a modified version of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Data Extraction form for Economic Evaluations [ 21 ]. Another author (GR) checked the extraction for accuracy. Data was extracted about the study method, evaluation design, participants, intervention used, comparator, outcomes, prices and currency used for costing, time period of analysis, setting, tools used to measure outcomes and authors conclusions. This information was presented descriptively and summarised in Table 1 (Additional file 2 ) . Both costs of care resulting from improved care and costs of establishing QICs were identified. Cost components were standardised by converting currency and year to US dollars for 2018 through the Eurostat-OECD data base and manual on purchasing power parities for Euros and The World Bank GDP deflator data base for United States dollar values [ 22 , 23 ].

Risk of bias assessment

Two checklists were used to critically appraise the studies due to the difference in design of studies included. The 24 item Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist was used to determine methodological quality of all the included studies as it applies to any form of economic evaluation [ 24 ]. This is presented in Table 2a (Additional file 3 ). The Evers CHEC-List [ 25 ] was also used to assess the full economic evaluations and is included as Table 2b (Additional file 4 ) [ 26 ]. A score of one point was assigned to each positive response, zero to a negative response or for items that did not apply. A summary score is calculated at the bottom of each table with a maximum score of 24 and 19 respectively. This scoring provides an indication of total items present for each study.

Assessment of generalizability

The currency and year of studies was converted to US dollars for 2018 using the Eurostat-OECD purchasing power parities data base for Euros and the World Bank deflator data base for US dollar updates. This provided an option to compare results but due to the varied type of studies and focus on the implementation method rather than the healthcare intervention, a full transferability assessment was not conducted.

Data synthesis

Included studies were subjected to data extraction by the author (LdlP) and information was synthesised to interpret the findings of full and partial economic evaluations and cost analysis studies. The Johanna Briggs Institute (JBI) ‘three by three dominance ranking matrix tool’ was used to interpret findings [ 27 ] and was checked by another author (GR) for consistency. Any inconsistencies were resolved by discussion and by consultation with a third review author (BK). This tool assists in drawing conclusions about the results of studies in terms of both cost and effectiveness (health benefits). It classifies results as favoured, unclear or rejected in favour of the comparator. An intervention was favoured if relative to its comparator it either (i) was cheaper but more effective, (ii) was cheaper but just as effective or (iii) cost the same but was more effective. An intervention was rejected if, relative to its comparator, it either (i) was more expensive and less effective, (ii) was more expensive and just as effective or (iii) cost the same but was less effective. A judgement would have to be made about all other scenarios based on other criteria [ 27 ]. For instance, an intervention would be favoured if it was more expensive and more effective than a comparator provided the associated incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was below the threshold used for assessing cost-effectiveness e.g. €80,000 per quality adjusted life years (QALY) in the Netherlands [ 28 ].

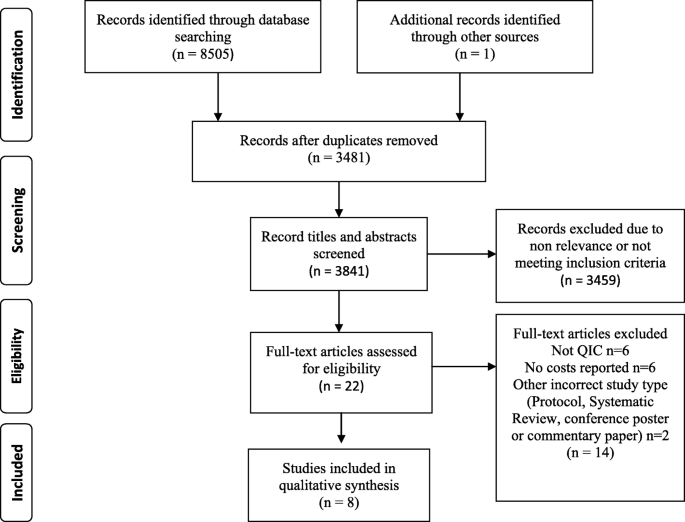

Study selection

The search identified 8505 citations and after removing duplicates, 3481 titles and abstracts were reviewed. Twenty-two full text reviews revealed eight papers that met the inclusion criteria. PRISMA flowchart at Fig. 1 describes the process of selection [ 29 ].

PRISMA flowchart describing the process of study selection

Overview of studies

Table 1 (Additional file 2 ) presents the overview of characteristics of the studies included in this review. Most studies describe the costs of establishing a collaborative to improve quality in healthcare and compared costs to outcomes. Five of the included studies involved full economic analyses using cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) or cost utility analysis (CUA) [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ], whereas three studies were cost analyses [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]. All studies were set in multi-centre healthcare settings, hospitals, long term care or community clinics, and related to diverse health conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, obstetrics, neonatal intensive care, hip fractures, pressure ulcers, cardiac care or addiction treatment. All included clinicians working either nationally or across multiple states.

Methodological quality

Table 2a (Additional file 3 ) summarises the methodological quality of the studies included in this review.

Cost effectiveness study conducted by Broughton et al. [ 30 ], and cost utility studies by Schouten et al. [ 33 ], Makai et al. [ 32 ] and Huang et al. [ 34 ] were considered high quality, complying with most of the items on CHEERS checklist [ 24 ]. Item 12 related to valuation of preferences for outcomes was not addressed in these studies [ 24 ]. A cost analysis by Bloem et al. [ 35 ] and a cost effectiveness study by Gustafson and colleagues [ 31 ] were of moderate quality. They did not address item 13, related to estimating costs via a model-based evaluation, items 15 and 16, the choice of model or assumptions or item 20, how uncertainty was addressed. The cost analysis by Rogowski et al. [ 36 ] was rated low quality on CHEERS checklist and the cost study by Dranove et al. [ 37 ] study was considered lowest quality as less than half of all items were addressed. Using the Evers CHEC-List [ 25 ], the full economic evaluations [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ] were rated good quality.

Conflicts of interest and uncertainties in data were addressed by five studies [ 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ]. An incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was not applicable for the cost analyses [ 35 , 36 , 37 ] and future costs were not directly considered for those studies.

Table 3 (Additional file 5 ) provides a three by three dominance ranking matrix (JBI DRM) tool to assist in interpreting the cost-effectiveness results of the studies included [ 27 ]. In this review, five studies were classified as favoured interventions (strong dominance) [ 30 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 ], two as unclear [ 32 , 34 ] and one rejected [ 37 ]. Bloem et al. [ 35 ], Broughton et al. [ 30 ] and Schouten et al. [ 33 ] all showed reduced costs and improved health outcomes and are most favoured interventions. The studies by Gustafson et al. [ 31 ] and Rogowski et al. [ 36 ] show reduced costs for equally effective processes which are next favoured interventions. The study by Makai et al. [ 32 ] reported increased costs and reduced pressure ulcers while Huang et al. [ 34 ] reported that the improvements in Diabetes care were not cost-effective. These results are uncertain because while the interventions were more expensive but also cost effective, most scenarios analysed yielded ICERs that were above the traditionally accepted thresholds of €80,000/QALY [ 32 ] and US$100,000/QALY [ 34 ]. They therefore need to be assessed against specific priorities for health improvements and expenditure. In a cost analysis, Dranove et al. [ 37 ] were unable to identify cost savings or health improvements as a result of quality improvement expenditure and the comparator is favoured in this case.

Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

Clinical effectiveness.

Five studies [ 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ] reported positive clinical outcomes as a result of using a QIC approach. In studies involving people with chronic health conditions, quality improvements led to reduced mortality risk and reduction in associated health events [ 33 , 35 ]. For example, adherence to guidelines for Parkinson’s disease care achieved via the collaboratives produced improved outcomes, such as reduction in hip fractures, fewer hospital admissions, lower mortality risk and fewer disease related complications [ 35 ]. Quality improvement in diabetes care [ 33 , 34 ] resulted in reduced scores for diabetes risk for cardiovascular disease events and mortality, reduced lifetime incidence of complications and improved life expectancy for both men and women. In both acute and critical care, the improvements led to reduced associated illness but differed in relation to the effect on mortality risk [ 30 , 36 ]. In obstetric care, establishment of a QIC resulted in reduced post-partum haemorrhage, reduced mortality and increased numbers of births in clinics [ 30 ]. In neonatal intensive care, a QIC achieved reductions in infections in critically ill pre-term babies and reduced surgical interventions but no significant difference in mortality was found [ 36 ]. Residents in long term care had reduced incidence of pressure ulcers and slightly improved quality of life as a result of a QIC [ 32 ].

Gustafson and colleagues tested the effectiveness of four different elements of a QIC in the context of addiction treatment clinics [ 31 ]. This study compared clinic level coaching, group telephone calls to clinicians, face to face learning sessions and a combination of these elements to see which methods were more effective. This study did not collect patient outcomes but focussed on three primary process outcomes: waiting time, retention of patients and annual numbers of new patients. These process outcomes were chosen, as the link between treatment programs and patient outcomes was considered weak [ 31 ]. Significant improvements in waiting time and number of new patients were identified for two of the interventions: coaching and the combination of all three elements. A combination of all elements was found to be more costly than coaching alone although it was similarly effective [ 31 ]. Dranove and colleagues found no direct links between the clinical outcomes for patients of hospitals studied and the amount they spent on general quality improvement activities [ 37 ].

Cost-effectiveness and cost savings

Five studies [ 30 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 ] reported favourable cost findings from the use of QICs. These were related to savings in the health care system and did not consider broader costs and benefits such as lost productivity, non-medical patient costs and carer time. These studies are considered here in relation to cost effectiveness and cost savings achieved for the use of QICs across a range of health conditions and countries. Values provided below are conversions to US$ for 2018 [ 22 , 23 ] where the price year was provided.

- Cost-effectiveness

Within the context of diabetes care in the Netherlands [ 33 ], the QIC was found to be cost-effective. For the large populations of people who live with diabetes there are significant medical costs related to medicines and cardio-vascular disease [ 33 , 34 ]. The incremental costs per quality adjusted life year (QALY) of US$1550–1714 compared favourably with other published studies on diabetes [ 33 ]. With a cost of about US$19 per patient for the QIC over 2 years, the cost-effectiveness was reported to be significant. In the US, a diabetes care improvement in public health clinics [ 34 ] found lower incidence of complications but the cost of individual improvements in care varied and all interventions but the use of an Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, were not cost-effective [ 34 ].

The cost effectiveness study examining obstetric and newborn care in Niger [ 30 ] found the cost per normal delivery reduced, with a similar decrease in both numbers and costs of deliveries with post-partum haemorrhage [ 30 ]. The cost of the QIC was calculated to be US$2.84 per delivery. The incremental cost-effectiveness was US$335 per disability-adjusted life year (DALY) averted and the study concluded that if other obstetric clinics used the collaborative approach, substantive cost savings could be achieved [ 30 ].

In long term care [ 32 ], reduction in incidence of non-severe pressure ulcers using a QIC approach increased costs of care in the short term. Cost-effectiveness in the longer term was unclear due to small effects on quality of life in nursing home populations near the end of life, and the difficulty in sustaining trained staff to continue to prevent pressure ulcers. As a preventable condition however, quality improvement in the prevention and care of pressure ulcers for a vulnerable population was a worthy goal [ 32 ].

A comparison of four different approaches to implementing QICs (in the context of addiction treatment) identified cost-effective elements [ 31 ]. This study found that while both coaching and a combination of interventions were equally effective in reducing waiting times and increasing numbers of new patients there were significant differences in costs of the interventions. They found the estimated cost per clinic for a coaching intervention was US$2878 (no year) compared to US$7930 (no year) for the combination of interventions. They concluded that the coaching intervention was substantially more cost-effective [ 31 ].

Cost analyses

A cost analysis of ParkinsonNet [ 35 ] showed annual cost savings of US$449 per patient by avoiding or delaying complications or high cost treatments of Parkinson’s disease. The cost per patient per annum was around US$30. However, based on a population of 40,000 people with Parkinson’s disease in The Netherlands, they predicted a national cost saving of over US$17.4 million per annum as a result of the quality improvement [ 35 ].

In the costly area of neonatal intensive care, a cost analysis study [ 36 ] reported significant cost savings per infant were achieved. While costs varied, the average savings per hospital in the post intervention year was US$2.3 million for an average cost of $68,206 per hospital in resources to undertake the QIC [ 36 ].

Finally, the study of costs to improve quality of care in hospitals in United States [ 37 ], found a wide variety in expenditures on quality improvement activities which were not correlated with condition specific costs. Differences in costs were not statistically significant. They presumed that a lack of consensus about the purpose of quality improvement efforts at the time, led to this variation in costs and disconnection with outcomes [ 37 ].

Costs of care

The costs of clinical treatment were measured in most studies and included clinic visits or treatment provided in hospital such as ventilation, surgery and medications, complications or infections [ 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Costs were extracted from hospital bills, medical claims and records maintained by clinicians. Some studies used estimations of costs to form their data, or surveyed managers to identify costs from budgets [ 30 , 33 ]; one used weekly diaries of activities and applied hourly costs for personnel time [ 36 ]. Costs of care were not reported in two studies [ 31 , 37 ].

Costs of establishing QICs

The most common costs identified were: program management costs for the QIC coordinators, time of the participating clinicians in face to face meetings, education sessions, collecting data, travel costs, conference calls, data analysis costs, overhead costs and some capital costs. The cost of developing evidence-based guidelines was included in the ParkinsonNet study to give a complete cost of start-up of the network [ 35 ]. Four studies provided a cost per patient of establishment of the QIC. These included US$3.67 per infant delivery [ 30 ], US$30 per person with Parkinson’s disease [ 35 ], US$19 per person with diabetes in Europe [ 33 ] and US$130 per patient with diabetes in USA [ 34 ]. Dranove et al. reported a wide variation in costs of quality improvement activities between hospitals with the highest costs attributed to meetings [ 37 ]. All reported costs are presented in Table 4 (Additional file 6 ).

There is a need for larger scale and more rapid translation of evidence-based interventions into practice [ 34 ]. However, the cost associated with research translation is an important consideration for constrained health care budgets. QICs have been used widely in diverse healthcare settings and have been effective in improving outcomes for patients [ 38 ] although the costs of the collaboratives may be a barrier to their use [ 35 ]. This review sought to identify and describe studies that report on the costs and cost-effectiveness of QICs in healthcare settings. Although a recent systematic review of QICs identified 64 studies on effectiveness, only four reported on cost-effectiveness [ 15 ]. We identified eight studies that reported on costs or cost-effectiveness of QICs. This included the four studies identified in the review by Wells et al. so updated that aspect of the review [ 15 ]. Our results confirm that the consideration of costs of QICs has not been reported in many studies. This may be because of the difficulty in defining costs associated with QICs over time and in different contexts [ 38 , 39 ]. It may be that costs are small in comparison to operating costs or funded separately to the health system and of less importance for research [ 40 ].

Five of the eight studies in this review showed that QICs were cost-effective in implementing clinical guidelines [ 30 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 ]. They identified cost savings and improvement in health outcomes for patients in both acute care and chronic condition management. The costs associated with the QIC appeared low in relation to savings across large populations or for reducing the need for high cost treatments [ 36 , 41 ]. These studies calculated the cost of the QIC per patient for the duration of the intervention which provided useful data compared to overall outcomes and savings achieved. Where smaller populations are treated with high cost interventions, the cost per patient for the QICs would be expected to be higher.

These studies were conducted in different countries or across states, with different infrastructure costs and resources. It would be difficult to generalize the costs of the QICs across such different countries and conditions. However, they used a similar process to engage clinicians and modify practices locally. This indicated that the QIC methodology was adapted to different conditions with similar set up structures needed. An investment in QICs was needed and the costs per person could be best spread across large populations of people with a condition or where high cost treatments can be reduced [ 38 ].

One study evaluated which element of the QIC intervention was more cost-effective [ 23 ]. This demonstrated that differences that can be achieved in both effectiveness and cost by the choice of how education or support was provided to clinicians. Only one study found no correlation between health outcomes and the costs of quality improvement activities in hospitals [ 26 ].

Although most of the studies captured only medical costs, most considered that societal effects of health improvements may increase the cost-effectiveness due to improved quality of life (QoL). For treatment of chronic conditions, improved care is likely to result in long term cost savings, however QoL in long term care populations was more difficult to measure [ 32 ]. Schouten et al. [ 22 ] found that a wide range of disease risk control was achieved in diabetes treatment. They suggested that outcomes of other chronic conditions may be improved through a QIC approach and the societal effects may also be higher when considering better quality of life outcomes. Bloem et al. [ 23 ] similarly identified the potential for improvement of cost-effectiveness of healthcare for other chronic disorders. They also reported the need to structure funding sources and medical insurance related to improvements in health outcomes.

Rogowski et al. [ 24 ] identified the potential for higher cost savings for expensive health interventions and at least short-term sustainability of QICs. Widespread adoption of the interventions may increase costs of interventions but Rogowski et al. considered that expected savings and benefits would offset these [ 24 ]. The potential for higher cost savings and effectiveness through a wider use or broader scale of QICs is a pertinent aspect of these studies for healthcare budgets.

The establishment of collaboratives was shown to require considerable investment in the initial phases of the improvements, which then decreased over time of the collaborative process. QICs were funded in most studies by national agencies with specialist healthcare improvement staff involved in developing the collaborative, engaging participants and providing education, guidance and support for the duration. Only one study identified the relative cost-effectiveness of different combinations of elements of a QIC [ 31 ]. This suggests an opportunity to improve cost-effectiveness of QICs by selecting key elements for uses.

Despite increasing acknowledgement of the importance of patient and public involvement, there was no involvement of members of the public or patients reported in these studies. Costs were spread across state and national healthcare systems to scale up improvements for low per clinic or patient cost. One study included the external cost of developing guidelines in the assessment of cost-effectiveness [ 35 ] which provided an additional insight into the costs of developing or adapting international guidelines to national conditions. In most cases the clinical guidelines were developed separately to implementation in healthcare services and funded separately. Despite this inclusion of the cost of developing guidelines, the use of the QIC was shown to be cost-effective [ 35 ].

The identified costs of the QIC had similar elements across the five studies showing cost-effectiveness [ 30 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 ]. Costs were highest for the initial development of collaboratives, face to face meetings and travel for participants, and for multi-factored interventions. While most studies used similar components of QICs as described by Nadeem et al. [ 13 ] and IHI [ 14 ], only one study compared the costs of different elements of the QIC [ 31 ]. There is an opportunity to consider which elements of QICs contribute to cost effectiveness and in which setting they may be useful. One study included the cost of development of guidelines and a maintenance cost for an ongoing collaborative [ 35 ]. This provides a wider consideration of all set up costs for quality improvement and the costs to maintain the collaborative beyond a research study. The local infrastructure costs varied widely in four studies [ 31 , 34 , 36 , 37 ] which made the cost assessments difficult to compare within and between studies. Inclusions and exclusions of costs varied between studies which also made comparisons between studies difficult. It would be of use to identify common costs to consider when budgeting for QICs and to allow for local differences in infrastructure.

The value of these studies shows that savings can be made to healthcare for quality improvements, the real set up costs and how to assess benefit. Caution in interpreting results is needed as the studies varied in what was included and costed and the perspective from which assessment of cost effectiveness was judged. Similarly, few studies of cost effectiveness of QICs were identified suggesting that studies with negative results may not have been published.

A strength of this review is the rigorous and systematic method used to identify studies and synthesise data. A comprehensive search strategy was developed and used in a range of databases. Our search of the grey literature was an important step given the variety of ways in which healthcare improvements are reported. The use of both the CHEERS checklist [ 24 ] and Evers CHEC-List [ 25 ] to assess the mixed designs found most studies to be of good to medium quality. The main limitations of the review are that only studies published in English were considered and we did not search trial registers. The few papers identified may reflect a publication bias or may indicate economic evaluations of QICs have not been conducted.

Few cost analyses or cost-effectiveness studies have been identified to assess the costs and benefits of QICs to translate research and knowledge into practice. Most that are included in this review show cost savings or improvement in healthcare process and patient outcomes across acute, long term care and chronic conditions. Judgement is required in relation to the priority given to healthcare improvement from a societal perspective compared to the cost of QICs. The potential to scale up knowledge translation through QICs and to improve cost-effectiveness based on these studies is suggested. The costs of QICs need to be factored into translation of improvements, and their costs or cost-effectiveness evaluated to identify savings to healthcare budgets and benefits to society. A detailed break-down of costs of QICs may assist in identifying elements of greatest cost and alternatives that may be effective for cost savings to the quality improvement process.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

European Euros

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre

Cost Effectiveness Analysis

Cost Effectiveness Ratio

Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards statement

Cost Utility Analysis

Disability Adjusted Life Year

Dominance Ranking Matrix

European Quality Group 5 dimensions 3 levels measure of quality of life

Consensus on Health Economic Criteria checklist by Silvia Evers et al.

Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Johanna Briggs Institute

Medical subject search headings

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia

Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy studies

Quality Adjusted Life Year

Quality Improvement

Quality Improvement Collaborative/s

Quality of Life

United Kingdom of Great Britain; US/USA: United States/United States of America

Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence based medicine a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014;348(7963):7.

Google Scholar

Brown V, Fuller J, Ford D, Dunbar J. The enablers and barriers for the uptake, use and spread of primary health care Collaboratives in Australia. Herston QLD: APHCRI Centre of research Excellence in Primary Health Care Microsystems; 2014. p. 2014.

KPMG. Economic Impact of Medical Research in Australia. Melbourne: KPMG; 2018. p. 2018.

Roberts, SLE, Healey A, Sevdalis N. Use of health economic evaluation in the implementation and improvement science fields—a systematic literature review. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):72.

Dalziel K, Segal L, Mortimer D. Review of Australian health economic evaluation - 245 interventions: what can we say about cost effectiveness? Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2008;6(1):9.

Article Google Scholar

Hoomans T, Severens J. Economic evaluation of implementation strategies in health care. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):168.

Grol R. Successes and Failures in the Implementation of Evidence-Based Guidelines for Clinical Practice. Med Care. 2001;39(8 Suppl 2):II46–54.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Grimshaw JM, Schünemann HJ, Burgers J, Cruz AA, Heffner J, Metersky M, et al. Disseminating and implementing guidelines: article 13 in integrating and coordinating efforts in COPD guideline development. An official ATS/ERS workshop report. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9(5):298–303.

Chan Wiley V, Pearson Thomas A, Bennett Glen C, Cushman William C, Gaziano Thomas A, Gorman Paul N, et al. ACC/AHA special report: clinical practice guideline implementation strategies: a summary of systematic reviews by the NHLBI implementation science work group: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(8):1076.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Greenhalgh T. The research traditions. In: Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, Macfarlane F, Kyriakidou O, (Editors). Diffusion of innovations in health service organisations:a systematic literature review. Malden: Blackwell; 2005.p 48–82.

Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–30.

Glasgow R, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury M, Kaplan R, Hunter C. National Institutes of Health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274–81.

Nadeem E, Olin SS, Hill LC, Hoagwood KE, Horwitz SM. Understanding the components of quality improvement Collaboratives: a systematic literature review. Milbank Q. 2013;91(2):354–94.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Breakthrough Series: IHI's Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. Boston: Institure for Healthcare Improvement; 2003. p. 2003.

Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, Naidoo D, Bekhit M, Goldmann D. Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Safety. 2018;27(3):226.

Ovretveit J, Gustafson D. Evaluation of quality improvement programmes. (Quality Improvement Research). Qual Safety Health Care. 2002;11(3):270.

Schouten L, Hulscher M, van Everdingen J, Huijsman R, Grol R. Evidence for the impact of quality improvement collaboratives: systematic review. Br Med J. 2008;336(7659):1491.

Chin MH. Quality improvement implementation and disparities: the case of the health disparities collaboratives. Med Care. 2010;48(8):668–75.

Ovretveit J, Bate P, Cleary P, Cretin S, Gustafson D, McInnes K, et al. Quality collaboratives: lessons from research. Qual Safety Health Care. 2002;11(4):345–51.

McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, McGrath TA, Bossuyt PM and thePRISMA-DTA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy studies: The PRISMA-DTA Statement, PRISMA reporting guideline for diagnostic test accuracy Studies. JAMA. 2018;319(4):388–96.

Aromataris E, Munn Z, (Editors) Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. Adelaide, SA: The Johanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

OECD, Eurostat. Eurostat-OECD Methodological Manual on Purchasing Power Parities (2012 Edition) 2012.

The World Bank. GDP Deflator (base year varies by country-United States) [Data Base]. 2019 [Data base of deflator values for US Dollars by year]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.DEFL.ZS?end=2018&locations=US&most_recent_year_desc=false&start=2000 .

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2013;346(mar25 1):f1049.

Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on health economic criteria. J of Inter Tech of Health Care. 2005;21(2):240–5.

Higgins J, Green S, (Editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2011.

Gomersall SJ, Jadotte TY, Xue TY, Lockwood TS, Riddle TD, Preda TA. Conducting systematic reviews of economic evaluations. Int J Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2015;13(3):170–8.

College voor Zorgverzekeringen (CVZ). Guidelines for pharmacoeconomic research in the Netherlands, updated version. 2006 ed. Dieman: College voor Zorgverzekeringen; 2006.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Broughton E, Saley Z, Boucar M, Alagane D, Hill K, Marafa A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a quality improvement collaborative for obstetric and newborn care in Niger. Int J Health Care Qual Assurance (09526862). 2013;26(3):250–61.

Gustafson DH, Quanbeck AR, Robinson JM, Ford JH 2nd, Pulvermacher A, French MT, et al. Which elements of improvement collaboratives are most effective? A cluster-randomized trial. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2013;108(6):1145–57.

Makai P, Koopmanschap M, Bal R, Nieboer AP. Cost-effectiveness of a pressure ulcer quality collaborative. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2010;8:11.

Schouten LM, Niessen LW, van de Pas JW, Grol RP, Hulscher ME. Cost-effectiveness of a quality improvement collaborative focusing on patients with diabetes. Med Care. 2010;48(10):884–91.

Huang ES, Zhang Q, Brown SES, Drum ML, Meltzer DO, Chin MH. The Cost-Effectiveness of Improving Diabetes Care in U.S. Federally Qualified Community Health Centers. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(6p1):2174–93.

Bloem BR, Rompen L, de Vries NM, Klink A, Munneke M, Jeurissen P. ParkinsonNet: a low-cost health care innovation with a systems approach from the Netherlands. Health Aff. 2017;36(11):1987–96.

Rogowski JA, Horbar JD, Plsek PE, Baker LS, Deterding J, Edwards WH, et al. Economic implications of neonatal intensive care unit collaborative quality improvement. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):23–9.

Dranove D, Reynolds KS, Gillies RR, Shortell SS, Rademaker AW, Huang CF. The cost of efforts to improve quality. Med Care. 1999;37(10):1084–7.

Franx G. Quality improvement in mental healthcare: the transfer of knowledge into practice, vol. 2012. Utrecht: The Trimbos Instituut; 2012.

Ovretveit J. Does improving quality save money? A review of evidence of which improvements to quality reduce costs to health service providers. London: The Health Foundation; 2009.

Chen LM, Rein MS, Bates DW. Costs of quality improvement: a survey of four acute care hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(11):544–50.

PubMed Google Scholar

Sathe NA, Nocon RS, Hughes B, Peek ME, Chin MH, Huang ES. The costs of participating in a diabetes quality improvement collaborative: variation among five clinics. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2016;42(1):18–24.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

Librarians Nikki Lee and Shannon Brown developed search strategies for six data bases.

This study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Partnership Centre on Dealing with Cognitive and Related Functional Decline in Older People (CDPC) (grant no. GNT 9100000) and a NHMRC Boosting Dementia Research Grant (APP1135667). KL is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Dementia Research Development Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Rehabilitation, Aged and Extended Care, Flinders University, Bedford Park SA, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide, 5001, South Australia

Lenore de la Perrelle, Gorjana Radisic, Monica Cations & Kate Laver

Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre, the University of Sydney, Hornsby Ku-Ring-Gai Hospital, Hornsby, NSW, Australia

Health Economics, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA, Australia

Billingsley Kaambwa

Health Services Management, School of Medicine, Griffith University, Southbank, Qld, Australia

Gaery Barbery

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KL conceptualised the review, obtained research funding, reviewed and edited the drafts and final manuscript. LdlP developed the PROSPERO registration, search strategies with assistance of librarians, screened titles, abstracts and full articles, extracted and synthesised data, drafted, reviewed and edited final manuscript. GR screened titles, abstracts and full articles, checked extraction and synthesis of data and reviewed the draft. BK reviewed and edited the drafts, checked extraction and synthesis of data and provided expert advice. MC and GB reviewed and edited the drafts and provided advice on methods and style. All authors read and approved final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lenore de la Perrelle .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Competing interests.