If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 4

- Jacksonian Democracy - background and introduction

- Jacksonian Democracy - the "corrupt bargain" and the election of 1824

- Jacksonian Democracy - mudslinging and the election of 1828

- Jacksonian Democracy - spoils system, Bank War, and Trail of Tears

Expanding democracy

- The presidency of Andrew Jackson

- Indian Removal

- The Nullification crisis

- The age of Jackson

- Manifest Destiny

- Annexing Texas

- Developing an American identity, 1800-1848

- James K. Polk and Manifest Destiny

- In the early nineteenth century, political participation rose as states extended voting rights to all adult white men.

- During the 1820s, the Second Party system formed in the United States, pitting Jacksonian Democrats against Whigs.

A new kind of democracy

The rise of political parties: the democrats and the whigs, what do you think, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Jacksonian Democracy

Notes: jacksonian democracy.

Political Cartoons: Differing Views of Andrew Jackson

DBQ 1990: Jacksonian Democracy

DBQ 2011: Politics from 1815-1840

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.2: Race and Jacksonian Democracy

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 9933

- American YAWP

- Stanford via Stanford University Press

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

More than anything else, however, it was racial inequality that exposed American democracy’s limits. Over several decades, state governments had lowered their property requirements so poorer men could vote. But as northern states ended slavery, whites worried that free black men could also go to the polls in large numbers. In response, they adopted new laws that made racial discrimination the basis of American democracy.

At the time of the Revolution, only two states explicitly limited black voting rights. By 1839, almost all states did. (The four exceptions were all in New England, where the Democratic Party was weakest.) For example, New York’s 1821 state constitution enfranchised nearly all white male taxpayers but only the richest black men. In 1838, a similar constitution in Pennsylvania prohibited black voting completely.

The new Pennsylvania constitution disenfranchised even one of the richest people in Philadelphia. James Forten, a free-born sailmaker who had served in the American Revolution, had become a wealthy merchant and landowner. He used his wealth and influence to promote the abolition of slavery, and after the 1838 constitution, he undertook a lawsuit to protect his right to vote. But he lost, and his voting rights were terminated. An English observer commented sarcastically that Forten wasn’t “white enough” to vote, but “he has always been considered quite white enough to be taxed .” 40

During the 1830s, furthermore, the social tensions that had promoted Andrew Jackson’s rise also worsened race relations. Almost four hundred thousand free blacks lived in America by the end of the decade. 41 In the South and West, Native Americans stood in the way of white expansion. And the new Irish Catholic immigrants, along with native working-class whites, often despised nonwhites as competitors for scarce work, housing, and status.

Racial and ethnic resentment thus contributed to a wave of riots in American cities during the 1830s. In Philadelphia, thousands of white rioters torched an antislavery meeting house and attacked black churches and homes. Near St. Louis, abolitionist newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy was murdered as he defended his printing press. Contemplating the violence, another journalist wondered, “Does it not appear that the character of our people has suffered a considerable change for the worse?” 42

Racial tensions also influenced popular culture. The white actor Thomas Dartmouth Rice appeared on stage in blackface, singing and dancing as a clownish slave named “Jim Crow.” Many other white entertainers copied him. Borrowing from the work of real black performers but pandering to white audiences’ prejudices, they turned cruel stereotypes into one of antebellum America’s favorite forms of entertainment.

Some whites in the 1830s, however, joined free black activists in protesting racial inequality. Usually, they lived in northern cities and came from the class of skilled laborers, or in other words, the lower middle class. Most of them were not rich, but they expected to rise in the world.

In Boston, for example, the Female Anti-Slavery Society included women whose husbands sold coal, mended clothes, and baked bread, as well as women from wealthy families. In the nearby village of Lynn, many abolitionists were shoemakers. They organized boycotts of consumer products like sugar that came from slave labor, and they sold their own handmade goods at antislavery fund-raising fairs. For many of them, the antislavery movement was a way to participate in “respectable” middle-class culture, a way for both men and women to have a say in American life.

Debates about slavery, therefore, reflected wider tensions in a changing society. The ultimate question was whether American democracy had room for people of different races as well as religions and classes. Some people said yes and struggled to make American society more welcoming. But the vast majority, whether Democrats or Whigs, said no.

- The Columbian Exchange

- De Las Casas and the Conquistadors

- Early Visual Representations of the New World

- Failed European Colonies in the New World

- Successful European Colonies in the New World

- A Model of Christian Charity

- Benjamin Franklin’s Satire of Witch Hunting

- The American Revolution as Civil War

- Patrick Henry and “Give Me Liberty!”

- Lexington & Concord: Tipping Point of the Revolution

- Abigail Adams and “Remember the Ladies”

- Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” 1776

- Citizen Leadership in the Young Republic

- After Shays’ Rebellion

- James Madison Debates a Bill of Rights

- America, the Creeks, and Other Southeastern Tribes

- America and the Six Nations: Native Americans After the Revolution

- The Revolution of 1800

- Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase

- The Expansion of Democracy During the Jacksonian Era

- The Religious Roots of Abolition

- Individualism in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance”

- Aylmer’s Motivation in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “The Birthmark”

- Thoreau’s Critique of Democracy in “Civil Disobedience”

- Hester’s A: The Red Badge of Wisdom

- “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?”

- The Cult of Domesticity

- The Family Life of the Enslaved

- A Pro-Slavery Argument, 1857

- The Underground Railroad

- The Enslaved and the Civil War

- Women, Temperance, and Domesticity

- “The Chinese Question from a Chinese Standpoint,” 1873

- “To Build a Fire”: An Environmentalist Interpretation

- Progressivism in the Factory

- Progressivism in the Home

- The “Aeroplane” as a Symbol of Modernism

- The “Phenomenon of Lindbergh”

- The Radio as New Technology: Blessing or Curse? A 1929 Debate

- The Marshall Plan Speech: Rhetoric and Diplomacy

- NSC 68: America’s Cold War Blueprint

- The Moral Vision of Atticus Finch

The Expansion of Democracy during the Jacksonian Era

Advisor: Reeve Huston , Associate Professor of History, Duke University ©2011 National Humanities Center

Lesson Contents

Teacher’s note.

- Image Analysis & Close Reading Questions

Follow-Up Assignment

- Student Version PDF

How did the character of American politics change between the 1820s and the 1850s as a result of growing popular participation?

Understanding.

Between the 1820s and 1850, as more white males won the right to vote and political parties became more organized, the character of American democracy changed. It became more partisan and more raucous, a turn that bred ambivalence and even discontent with politics and the dominant parties.

The County Election

- George Caleb Bingham, The County Election , painting, 1852 (St. Louis Art Museum)

- Richard Caton Woodville, Politics in an Oyster House , painting, 1848 (Walters Art Museum)

- Agrarian Workingmen’s Party, New York City, political cartoon , ca. 1830 (Columbia University Libraries)

Find more primary resources on popular democracy between the 1820s and 1850s in The Triumph of Nationalism/The House Dividing .

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

Common Core State Standards

- ELA-LITERACY RH.11-12.2 (Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source…)

Advanced Placement US History

- Key Concept 4.1 (IC) (…new political parties arose…)

Advanced Placement Language and Composition

- Analyze graphics and visual images… as alternative forms of text.

The richest document of the three, The County Election is a reasonably reliable depiction of elections of this period. It tells us who participated and who was excluded from election rituals. It illustrates how the parties induced voters to come to the polls and vote for their candidates. They supplied alcohol: note the three stages of inebriation — still conscious in the left corner, about to pass out in the right, and long gone in the center. They engaged in polite persuasion: note the party activist on the stairs tipping his top hat and offering what is probably a pre-printed party ballot to the rural gentleman. But there was also voter-to-voter case-making, unsponsored by the parties but deeply serious nonetheless: note the resolute look and finger-to-the-palm intensity of the solid citizen in the right center. Despite its civic importance and the touch of solemnity imparted by the oath-taking man at the top of the stairs, there is about the whole scene the air of a convivial community gathering, suitable for children and tolerant of stray dogs.

While Bingham’s The County Election offers broad commentary on popular elections, Woodville’s Politics in an Oyster House makes a more concentrated point. It depicts the passionate commitments that party politics stirred up, as exemplified by the figure on the right, but also suggests that not everyone shared those passions. It is worth discussing what the attitude of the figure on the left is toward his companion’s political harangue. The older gentleman stares almost directly at us, seeming to implore us to rescue him from his tedious companion. Here, as in The County Election , a newspaper fuels opinions and stirs emotion.

The Agrarian Workingmen’s Party cartoon was likely published during the 1830 political campaign in New York (the men listed on the flag ran for office that year as candidates for the Agrarian Party, a splinter group of the city Workingmen’s Party). The cartoon depicts two kinds of politics: one the corruption of republican virtue, the other a restoration of it. On the left, a party politician dressed as a wealthy man — note the top hat again — and carrying a bag of money makes a deal with Satan. He asks Satan to “give me one of your favorites — TAMMANY , SENTINEL , or JOURNAL — or the POOR will get their rights. I’ll pay all.” Tammany was the Tammany Society, one of the most powerful Democratic clubs in New York. The Sentinel and the Journal were the newspapers of rival workingmen’s factions that pummelled the Agrarian Party’s political stands. In other words, the devil controls all the opposing parties; they are all his favorites. By turning one — any one — over to the hack, he will insure that the poor will be oppressed. In contrast, on the right, a workingman, raising a ballot, approaches a box carried by Lady Liberty, who holds a pole adorned with a liberty cap, a symbol of revolution and equality.

This lesson is divided into two parts, both accessible below. Three images with accompanying close reading questions provide analytical study. An optional follow-up assignment enhances the lesson. The teacher’s guide includes a background note, the image analysis with responses to the close reading questions, and an optional follow-up assignment. The student’s version, an interactive PDF, contains all of the above except the responses to the close reading questions and the follow-up assignment.

Teacher’s Guide

From the 1820s through the 1850s American politics became in one sense more democratic, in another more restrictive, and, in general, more partisan and more effectively controlled by national parties. Since the 1790s, politics became more democratic as one state after another ended property qualifications for voting. Politics became more restrictive as one state after another formally excluded African Americans from the suffrage. By 1840, almost all white men could vote in all but three states (Rhode Island, Virginia, and Louisiana), while African Americans were excluded from voting in all but five states and women were disfranchised everywhere. At the same time, political leaders in several states began to revive the two-party conflict that had been the norm during the political struggles between the Federalists and the Jeffersonian Republicans (1793–1815). Parties and party conflict became national with Andrew Jackson’s campaign for the presidency in 1828 and have remained so ever since. Parties nominated candidates for every elective post from fence viewer to president and fought valiantly to get them elected.

The number of newspapers exploded; the vast majority of them were mouthpieces for the Democratic Party or the Whig Party (the National Republican Party before 1834). Accompanying the newspapers was a flood of pamphlets, broadsides, and songs aimed at winning the support of ordinary voters and teaching them to think as a Democrat or a Whig. Parties also created gigantic and incredibly effective grass-roots organizations. Each party in almost every school district and urban ward in the country formed an electoral committee, which organized partisan parades, dinners, and picnics; distributed partisan newspapers and pamphlets, and canvassed door-to-door. In this way the parties got ordinary voters involved in politics, resulting in extremely high voter participation rates (80–90%). Even more than in the earlier period, parties were centrally coordinated and controlled. They expected their leaders, their newspapers, and their voters to toe the party line. Once the party caucus or convention had decided on a policy or a candidate, everyone was expected to support that decision.

The Democrats, National Republicans, and Whigs were not the only people creating a new kind of democracy, however. Several small, sectional parties promoted a way of conducting politics that was quite different from the practices of the major parties. The Workingmen’s Party, for example, organized in the major northeastern cities and in dozens of small, industrial towns in New England. Workingmen’s parties were part of the emerging labor movement and were made up primarily of skilled craftsmen whose trades were being industrialized. In addition, a growing movement of evangelical Christians sought to reform society by advocating temperance, an end to prostitution, the abolition of slavery, women’s rights, and more.

The two paintings and the cartoon offered here capture the passion, tumult, and divisions that came to characterize American democracy at this time.

George Caleb Bingham (1811–79) was one of the most successful and important American artists of the early nineteenth century. Born in 1811 to a prosperous farmer, miller, and slaveowner in western Virginia, Bingham knew prosperity but also experienced economic hardship when his father lost his property in 1818 and again when his father died in 1823. While he was a cabinet-maker’s apprentice, Bingham began painting portraits for $20 apiece and, by 1838, was beginning to acquire a reputation as an artist. During the 1840s he moved to St. Louis, the largest city in the West, where he pursued a successful career as a portrait artist. In 1848 he was elected to the Missouri General Assembly and later held several appointive posts. With gentle humor The County Election captures the arguing, the campaigning, and the drinking that accompanied the masculine ritual of voting in mid-nineteenth century rural America.

Richard Caton Woodville (1825–55) was born in Baltimore. His family hoped he would become a physician, and he did undertake medical studies in 1842. However, by 1845, when he traveled to Germany to train at the Dusseldorf Academy, he had abandoned medicine to pursue a career as an artist. Although he spent the rest of his life in Germany, France, and England, he devoted himself to re-creating his native Baltimore on canvas. With humor akin to that of Bingham, Politics in an Oyster House depicts a “conversation” between a young political enthusiast and a skeptical old-timer. As in The County Election , the political realm is exclusively masculine, for the oyster house is a male-only pub.

The Workingmen’s Party cartoon illustrates disillusionment with and dissent from the sharply divisive politics of the age. It suggests that the corruption of both the Whigs and the Democrats will lead to the oppression of the poor.

For each image, before posing the content-specific questions listed below, we recommend that you have students conduct a general analysis using the following four-step procedure.

- Visual Inventory: Describe the image, beginning with the largest, most obvious features and proceed toward more particular details. Describe fully, without making evaluations. What do you see? What is the setting? What is the time of day, the season of the year, the region of the country?

- Documentation: Note what you know about the work. Who made it? When? Where? What is its title? How was it made? What were the circumstances of its creation? How was it received? (With this step you may have to help students. Refer to the lesson’s background note for information.)

- Associations: Begin to make evaluations and draw conclusions using observations and prior knowledge. How does this image relate to its historical and cultural framework? Does it invite comparison or correlation with historical or literary texts? Do you detect a point of view or a mood conveyed by the image? Does it present any unexplained or difficult aspects? Does it trigger an emotional response in you as a viewer? What associations (historical, literary, cultural, artistic) enrich your viewing of this image?

- Interpretation: Develop an interpretation of the work which both recognizes its specific features and also places it in a larger historical or thematic context.

George Caleb Bingham, The County Election , oil on canvas, 1851–1852 (St. Louis Art Museum)

2. How did Bingham explain the enormous popular participation in politics? What drew so many people into politics? The political parties offered drink, food, fellowship, and the opportunity to discuss issues of the day. They distributed pamphlets and broadsides.

3. Why might elections in rural areas have become important social gatherings? They would be a reason for those in rural areas to gather. General farm work took up much of the time, and an election was a reason to take a break from farm work and catch up with the community. The fact that elections occurred on a regular schedule for the most part helped as well.

4. How important were political candidates, issues, and party loyalties? They became important as more people were able to vote. As the parties worked to build their constituency they expected those of their party to be loyal to the party line.

5. How engaged are the voters? They are engaged, including drinking (several have had more than enough to drink), accepting a broadside or sample ballot, and discussing the issues of the election.

6. Who are the men in the top hats? What are they doing? How does Bingham portray them? How do they relate to ordinary voters? The men in the top hats are probably working for a party trying to garner support. They are portrayed as polite strangers who are trying to engage and encourage voters through discussion and distributing pamphlets or sample ballots.

7. What do you think Bingham’s attitude toward elections was? His attitude was that the election was a community gathering for a purpose. There is a suggestion of certified business conveyed by the man at the top of the stairs, so the viewer does not forget that the election is official. But in general the tone is that of a friendly community gathering that welcomes all potential voters.

8. Did he see them as serious exercises of democracy, as farce, or as something in between? He saw them as something in between. There is indeed a serious exercise of democracy as speech appears to be free, but there are also focused attempts at persuasion (coercion?) by those working for the party.

9. What was his attitude toward the electorate? Did he see voters as serious well informed men or as manipulated dupes? He saw voters as well informed, listening to party members and discussing issues with their fellow voters.

Politics in an Oyster House

Richard Caton Woodville, Politics in an Oyster House , oil on fabric, 1848 (Walters Art Museum)

12. What might the open curtain symbolize? It might symbolize that this could have been a private table where the two men could have discussed issued in private. That the curtain is open could symbolize that the issues or discussion expanded beyond the normal limits of conversation. It also could imply that the man on the left is wanting to leave.

13. What sort of people are the men in the painting? What do their clothes tell us? Why has Woodville dressed the young man entirely in one color? What is the significance of their difference in age? The younger man is wearing his top hat indoors, giving the impression of a young, perhaps inexperienced man on the go. By dressing him in one color the viewer focuses more on his apparent harangue than his clothing. The older man on the left appears to be dressed more appropriately, with color, and he conveys experience and possible affluence.

14. What is the man on the right doing? How much does he care about politics? How does Woodville signal his passion? What is the source of his arguments? The man on the right is conveying his passionate argument, and he cares very much about politics. His body language leaning forward conveys his passion. He’s using his hands to convey his message and signal his passion and clings to the newspaper from which his arguments are drawn.

15. How does the man on the left feel about his companion’s political arguments and passion? Do you think he agrees or disagrees? Does he care? The man on the left is a bit apathetic, conveying that he has either heard this before or doesn’t care. His facial expression asks the viewer to save him from this speech.

Agrarian Workingmen’s Party cartoon

Upper left: “We are in favour of Monarchy, Aristocracy, Monopolies, Auctions, laws that oppress the Poor , Imposture and the rights of the rich man to govern and enslave the Poor man at his will and pleasure, denying the Poor the right to redress, or any participation in political power.”

Satan: “Take any, my dear Friend, they will all help you to grind the WORKIES [workingmen]!!”

Box in Satan’s hand: “Ballot Box”

Man in top hat: “My Old Friend, give me one of your favourites — TAMMANY — SENTINEL , or JOURNAL , or the POOR will get their rights. I’ll pay all.”

Box in lower left foreground: “This contains the cause of all the misery and distress of the human family.”

Upper right: “We are opposed to Monarchy, Aristocracy, Monopolies, Auctions, and in favour of the Poor to political power, denying the right of the rich to govern the Poor, and asserting in all cases, that those who labour should make the laws by which such labour should be protected and rewarded and finally, opposed to degrading the Mechanic, by making Mechanics of Felons. Our motto shall be Liberty , Equity , Justice , and The Rights of Man .”

Liberty’s banner [Candidates of the Agrarian Workingmen’s Party, Nov. 1830 election]: “ Register , John R. Soper, Mariner. Assembly , Henry Ireland, Coppersmith; William Forbes, Silversmith; William Odell, Grocer; Micajah Handy, Shipwright; Edmund L. Livingston, Brassfounder; Joseph H. Ray, Printer; Merritt Sands, Cartman; Samuel Parsons, Moroccodresser; Thompson Town, Engineer; Alexander Ming, Senior, Printer; Hugh M’Bride, Cartman. For Lieutenant-governor , Jonas Humbert, Senior, Baker. Senator , George Bruce, Typefounder. Congress , Alden Potter, Machinist; John Tuthill, Jeweller; Thomas Skidmore, Machinist.

Worker: “Now for a noble effort for Rights, Liberties, and Comforts, equal to any in the land. No more grinding the POOR — But Liberty and the Rights of man.”

Box in Liberty’s hand: “Ballot Box”

Agrarian Workingmen’s Party of New York City, political cartoon, ca. 1830 (Columbia University Libraries)

18. What is the politician trying to accomplish? He is making a deal with the devil in order to limit and control the working man.

19. What function does the cartoonist think the parties and their newspapers served? The parties and their newspapers kept the working man from achieving the liberties due to him. They kept monarchies, anarchies, and those who would deny working rights in power. They also kept the working man from achieving political power.

20. What was the cartoonist saying about the character of the Workingmen’s Party? The Workingmen’s Party is directly opposed to the main parties and wants to empower the working man to have control over those laws that directly affect them.

21. Which figure — the workingman or the party politician — did the cartoonist think was the legitimate protector of the accomplishments of the Revolution? He felt the workingman was, since he is working with Mother Liberty.

22. What is the cartoonist saying about the nature of politics as conducted by the major parties? The major parties conduct politics in an evil and dishonest way, making deals with the devil. They are corrupt. The party man has a bag of money in his hand, contrasted with the ballot in the hands of the workingman. Thus the major parties get their power from money rather than the voice of the people (or the ballot).

Ask your students, either in discussion or in a written assignment, to analyze George Caleb Bingham’s Stump Speaking (oil on canvas, 1853-54) in terms of the changes that occurred in American politics between the 1820s and the 1850s.

- How does Bingham’s Stump Speaking reflect changes that occurred in American politics between the 1820s and 1850s?

If you want to bring the discussion into the twentieth century, you can ask students to compare Stump Speaking with Norman Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech (oil on canvas, 1943) from his Four Freedoms series. (The link takes you to the presentation of the painting in the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Picturing America website. It includes an informative note plus useful interpretative prompts that you could apply to both works.)

- Compare and contrast Bingham’s Stump Speaking with Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech . How does the 1943 painting reflect political changes that took place in America a century earlier?

- George Caleb Bingham, The County Election , oil on canvas, 1852. Saint Louis Art Museum, gift of Bank of America, 44:2001. Reproduced by permission.

- Richard Caton Woodville, Politics in an Oyster House , oil on fabric, 1848. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland, 37.1994. Reproduced by permission.

- Agrarian Workingmen’s Party of New York City, political cartoon, ca. 1830. Columbia University Libraries, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Edwin Kilroe Ephemera Collection. Reproduced by permission.

National Humanities Center | 7 T.W. Alexander Drive, P.O. Box 12256 | Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709

Phone: (919) 549-0661 | Fax: (919) 990-8535 | nationalhumanitiescenter.org

Copyright 2010–2023 National Humanities Center. All rights reserved.

ENGL405: The American Renaissance

Jacksonian democracy and the ideal of the self-made man.

As you saw when reading his biography, Jackson is widely regarded as a self-made man. Read this short essay on the development of this concept of the self-made man in the context of Jacksonian Democracy and American Romanticism. Think about how the pieces by Truth and Apess contradict this self-making. What does this reveal about race, ethnicity, and class in this literary period? Are certain people and voices allowed personhood when others are not?

Perhaps no one's figure casts as long a shadow over the first half of the nineteenth century as Andrew Jackson. As described elsewhere in this subunit, Jackson was frequently taken to embody the best and worst of the new nation. He had emerged from the Revolutionary War as an orphan. After moving to the frontier of Tennessee, he had successfully become a wealthy planter and important political leader before gaining national military renown in the War of 1812. Jackson's election to the presidency in 1828 was seen by many as the triumph of democracy. Where most states had significant property requirements for suffrage after the Revolution, by the time of Jackson's election, universal adult white male suffrage was the rule. At the same time, the democratization of white male suffrage corresponded with increasing voting limitations on people of color, the deepening entrenchment of slavery in the South, and the expansion of Indian removal from the eastern United States. For those opposed to Jackson, his election suggested the rise of mob rule or demagoguery. Jackson represented more than just the rule of the common (white) man; he represented, for many, the potential of each and every man to determine his own fate, economically, socially, and politically. During the Revolutionary era, many American colonists implicitly acceded to the idea that the more elite members of society should be trusted to make the most important decisions regarding the political and social lives of the nation. Where most American colonists and Americans of the Revolutionary era would have accepted that a person's place in the world was determined by God and/or by his family's social and economic standing, the Jacksonian era saw the full emergence of the ideal that each American, through hard work and perseverance, not only could but should determine his place in the world and that he should have an equal voice in determining the future of the country.

While not yet so widely accepted, this emphasis on self-determination can be found in nascent form in many Revolutionary-era writings and thinkers, with Thomas Jefferson's celebration of the yeoman farmer and Benjamin Franklin's account of his own rags-to-riches story as a model for young Americans standing out. Where Jefferson called, before his presidency at least, for economic self-sufficiency grounded in small scale agriculture, Franklin foresaw the fuller development of market forces. One of the key factors behind the development of Jacksonian democracy and its emphasis on the self-made man was the market revolution, the broadening incorporation of more and more Americans into market relations in terms of selling their labor and their products and in terms of buying the goods they consumed. Jefferson's concerns about market relations – that the dependence "on casualties and caprice of customers . . . . begets subservience and venality" – indicates the ways that they had traditionally seemed to undermine masculine economic independence. Over the course of the nineteenth century, however, this ideal of economic self-sufficiency largely detached from the marketplace became harder and harder to imagine, as farmers increasingly became reliant on selling their crops to markets for funds to purchase their daily goods and artisanal work was largely displaced by large-scale factory operations. At the same time as most American men became more entrenched within market relations and more dependent on them, defenders of the capitalist marketplace began to characterize those economic relations not in terms of dependence and subservience but in terms of proving one's self-worth and relying on one's self to survive and thrive within the competitive environment of the marketplace. What had previously been seen as detrimental to individual masculine economic self-sufficiency came to be a vital part of new definitions of masculine independence.

At the same time that political changes gave the average white man greater political power and economic transformations played up the individual's responsibility for taking care of his financial needs in an increasingly interdependent economy, cultural developments similarly emphasized the priority of the individual. Within religion, as explored more fully elsewhere in this course, the Second Great Awakening brought an intensified focus on the individual's soul and his individual relationship to God. Within literature and philosophy, romanticism, as first articulated at the end of the eighteenth century in Germany, France, and England, foregrounded individual judgment in ethical and aesthetic matters and enshrined subjective perception as the starting point for inquiry. In the United States, this romantic individualism reaches its apex in the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson. To an even greater extent than his European precursors, Emerson viewed the individual as the focus of philosophical and literary pursuit and the yardstick by which truth and morality could be judged. This more profound reliance on the self within the American context derived, in part, from the United States' relative lack of strong social structures and of long-standing social and political relationships and hierarchies. Unlike most of Europe, the U.S. provided ample opportunities for geographic and social mobility, thus countering any sense that any social or cultural institutions should determine individuals' behavior or their sense of place within society. This relative lack of impediment against self-determination (for most white men, at least) gave rise to American romanticism and American culture more broadly to what the literary historian R. W. B. Lewis called the American Adam, the idea that like Adam, the individual American was not constrained by the past or by social connections or entanglements, by longstanding social or communal habits, or by ways of being and thinking.

Emerson's philosophical and literary emphasis on individual perspective and judgment and on self-reliance can be seen as parallel to the democratization of the Jacksonian era and the increasing acceptance of a capitalist ethos of economic self-orientation. Critics and historians have explored how Emerson's thought in particular and American romanticism more broadly both emerged out of these developments and helped to encourage them. And, at times, Emerson's characterization of his ideal of self-reliance played up the economic self-sufficiency and political self-determination of these other spheres. In his essay "Self-Reliance" and elsewhere, Emerson alludes at different times to the importance of maintaining individual political judgment and to the forces of capitalism acting as correctives to those who do not wisely rely on themselves economically. Emerson more frequently and consistently distinguished his emphasis on the individual from political and economic individualism. As "Self-Reliance" repeatedly emphasizes, this political and economic sort of self-reliance is, for Emerson, a very thin version of what he actually calls for. In fact, he often suggests that what most Americans saw as essential to self-made manhood – free political judgment and economic self-sufficiency – most often involved neither, as the vast majority of individuals simply followed their political party or church and the economic relations of the modern world necessarily involved a high level of interdependence. While most white American men would have insisted that they acted independently, following their own judgments, Emerson maintained that his contemporaries merely followed the herd, that "we are a mob". In particular, towards the end of the essay, when he insists that "a greater self-reliance must work a revolution in all the offices and relations of men", Emerson points to supposed economic independence as yet another form of relying on people and objects outside the self – "And so the reliance on Property, including the reliance on governments which protect it, is the want of self-reliance". Emerson's individualism calls for the very obliteration of the self, for the deepest, truest part of the self is not, finally, our own. This point arises when he asks about "the reason of self-trust" and concludes that the foundation for that self-trust, "the fountain of action and of thought", derives from the fact that "We lie in the lap of immense intelligence, which makes us receivers of its truth and organs of its activity. When we discern justice, when we discern truth, we do nothing of ourselves, but allow a passage to its beams". Rather than being an expression of individual will-power and self-determination, for Emerson true individualism emerges out of a loss of the self into something greater, to allowing the universal flow of divinity to guide us.

Like many other authors from the antebellum period, both canonical writers such as Hawthorne and Melville as well as more recently recovered writers such as Margaret Fuller and Frederick Douglass, Emerson offers a profound critique of dominant conceptions of American masculine individualism even as he shares many features with them. He evidences one of the many ways that many Americans from that time forward have viewed such an ideal as less a real goal for the nation's individuals to pursue than a delusion. Unlike Emerson's critique, however, which saw contemporary notions of self-reliance as too dependent on dominant notions of success and independence and as failing to acknowledge the self's foundation in a universal oneness, most critiques emphasized – and continue to emphasize – how this ideal obscures the fact that relatively few individuals (even among adult white men) have the opportunity and economic resources to even approximate this kind of independence. Yet the self-made manhood that Jackson so forcefully embodied continues to have great power in the U.S. Even as there is widespread recognition of how limited the opportunities of such self-creation were in the past – a point many authors of the antebellum period reflected on in various ways – the nation as a whole still tends to view the ideal as defining our greatest heroes and its expansion to as many individuals as defining our nation's social and moral health.

THE AMERICAN YAWP

9. democracy in america.

George Caleb Bingham, The County Election . Reynolda House Museum of American Art .

*The American Yawp is an evolving, collaborative text. Please click here to improve this chapter.*

I. Introduction

Ii. democracy in the early republic, iii. the missouri crisis, iv. the rise of andrew jackson, v. the nullification crisis, vi. the eaton affair and the politics of sexuality, vii. the bank war, viii. the panic of 1837, ix. rise of the whigs, x. anti-masons, anti-immigrants, and the whig coalition, xi. race and jacksonian democracy, xii. primary sources, xiii. reference material.

On May 30, 1806, Andrew Jackson, a thirty-nine-year-old Tennessee lawyer, came within inches of death. A duelist’s bullet struck him in the chest, just shy of his heart (the man who fired the gun was purportedly the best shot in Tennessee). But the wounded Jackson remained standing. Bleeding, he slowly steadied his aim and returned fire. The other man dropped to the ground, mortally wounded. Jackson—still carrying the bullet in his chest—later boasted, “I should have hit him, if he had shot me through the brain.” 1

The duel in Logan County, Kentucky, was one of many that Jackson fought during the course of his long and highly controversial career. The tenacity, toughness, and vengefulness that carried Jackson alive out of that duel, and the mythology and symbolism that would be attached to it, would also characterize many of his later dealings on the battlefield and in politics. By the time of his death almost forty years later, Andrew Jackson would become an enduring and controversial symbol, a kind of cipher to gauge the ways that various Americans thought about their country.

Today, most Americans think democracy is a good thing. We tend to assume the nation’s early political leaders believed the same. Wasn’t the American Revolution a victory for democratic principles? For many of the founders, however, the answer was no.

A wide variety of people participated in early U.S. politics, especially at the local level. But ordinary citizens’ growing direct influence on government frightened the founding elites. At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Alexander Hamilton warned of the “vices of democracy” and said he considered the British government—with its powerful king and parliament—“the best in the world.” 2 Another convention delegate, Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, who eventually refused to sign the finished Constitution, agreed. “The evils we experience flow from an excess of democracy,” he proclaimed. 3

Too much participation by the multitudes, the elite believed, would undermine good order. It would prevent the creation of a secure and united republican society. The Philadelphia physician and politician Benjamin Rush, for example, sensed that the Revolution had launched a wave of popular rebelliousness that could lead to a dangerous new type of despotism. “In our opposition to monarchy,” he wrote, “we forgot that the temple of tyranny has two doors. We bolted one of them by proper restraints; but we left the other open, by neglecting to guard against the effects of our own ignorance and licentiousness.” 4

Such warnings did nothing to quell Americans’ democratic impulses in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Americans who were allowed to vote (and sometimes those who weren’t) went to the polls in impressive numbers. Citizens also made public demonstrations. They delivered partisan speeches at patriotic holiday and anniversary celebrations. They petitioned Congress, openly criticized the president, and insisted that a free people should not defer even to elected leaders. In many people’s eyes, the American republic was a democratic republic: the people were sovereign all the time, not only on election day.

The elite leaders of political parties could not afford to overlook “the cultivation of popular favour,” as Alexander Hamilton put it. 5 Between the 1790s and 1830s, the elite of every state and party learned to listen—or pretend to listen—to the voices of the multitudes. And ironically, an American president, holding the office that most resembles a king’s, would come to symbolize the democratizing spirit of American politics.

A more troubling pattern was also emerging in national politics and culture. During the first decades of the nineteenth century, American politics shifted toward “sectional” conflict among the states of the North, South, and West.

Since the ratification of the Constitution in 1789, the state of Virginia had wielded more influence on the federal government than any other state. Four of the first five presidents, for example, were from Virginia. Immigration caused by the market revolution, however, caused the country’s population to grow fastest in northern states like New York. Northern political leaders were becoming wary of what they perceived to be a disproportionate influence in federal politics by Virginia and other southern states.

Furthermore, many northerners feared that the southern states’ common interest in protecting slavery was creating a congressional voting bloc that would be difficult for “free states” to overcome. The North and South began to clash over federal policy as northern states gradually ended slavery but southern states came to depend even more on enslaved labor.

The most important instance of these rising tensions erupted in the Missouri Crisis. When white settlers in Missouri, a new territory carved out of the Louisiana Purchase, applied for statehood in 1819, the balance of political power between northern and southern states became the focus of public debate. Missouri already had more than ten thousand enslaved labors and was poised to join the southern slave states in Congress. 6

Accordingly, Congressman James Tallmadge of New York proposed an amendment to Missouri’s application for statehood. Tallmadge claimed that the institution of slavery mocked the Declaration of Independence and the liberty it promised to “all men.” He proposed that Congress should admit Missouri as a state only if bringing more enslaved people to Missouri were prohibited and children born to those enslaved there were freed at age twenty-five.

Congressmen like Tallmadge opposed slavery for moral reasons, but they also wanted to maintain a sectional balance of power. Unsurprisingly, the Tallmadge Amendment met with firm resistance from southern politicians. It passed in the House of Representatives because of the support of nearly all the northern congressmen, who had a majority there, but it was quickly defeated in the Senate.

When Congress reconvened in 1820, a senator from Illinois, another new western state, proposed a compromise. Jesse Thomas hoped his offer would not only end the Missouri Crisis but also prevent any future sectional disputes over slavery and statehood. Henry Clay of Kentucky joined in promoting the deal, earning himself the nickname “the Great Compromiser.”

Their bargain, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, contained three parts. 7 First, Congress would admit Missouri as a slave state. Second, Congress would admit Maine (which until now had been a territory of Massachusetts) as a free state, maintaining the balance between the number of free and slave states. Third, the rest of the Louisiana Purchase territory would be divided along the 36°30’ line of latitude—or in other words, along the southern border of Missouri. Slavery would be prohibited in other new states north of this line, but it would be permitted in new states to the south. The compromise passed both houses of Congress, and the Missouri Crisis ended peacefully.

Not everyone, however, felt relieved. The Missouri Crisis made the sectional nature of American politics impossible to ignore. The Missouri Crisis split the Democratic-Republican party entirely along sectional lines, suggesting trouble to come.

Worse, the Missouri Crisis demonstrated the volatility of the slavery debate. Many Americans, including seventy-seven-year-old Thomas Jefferson, were alarmed at how readily some Americans spoke of disunion and even civil war over the issue. “This momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror,” Jefferson wrote. “I considered it at once as the [death] knell of the Union.” 8

For now, the Missouri Crisis did not result in disunion and civil war as Jefferson and others feared. But it also failed to settle the issue of slavery’s expansion into new western territories. The issue would cause worse trouble in years ahead.

The career of Andrew Jackson (1767–1845), the survivor of that backcountry Kentucky duel in 1806, exemplified both the opportunities and the dangers of political life in the early republic. A lawyer, enslaver, and general—and eventually the seventh president of the United States—he rose from humble frontier beginnings to become one of the most powerful Americans of the nineteenth century.

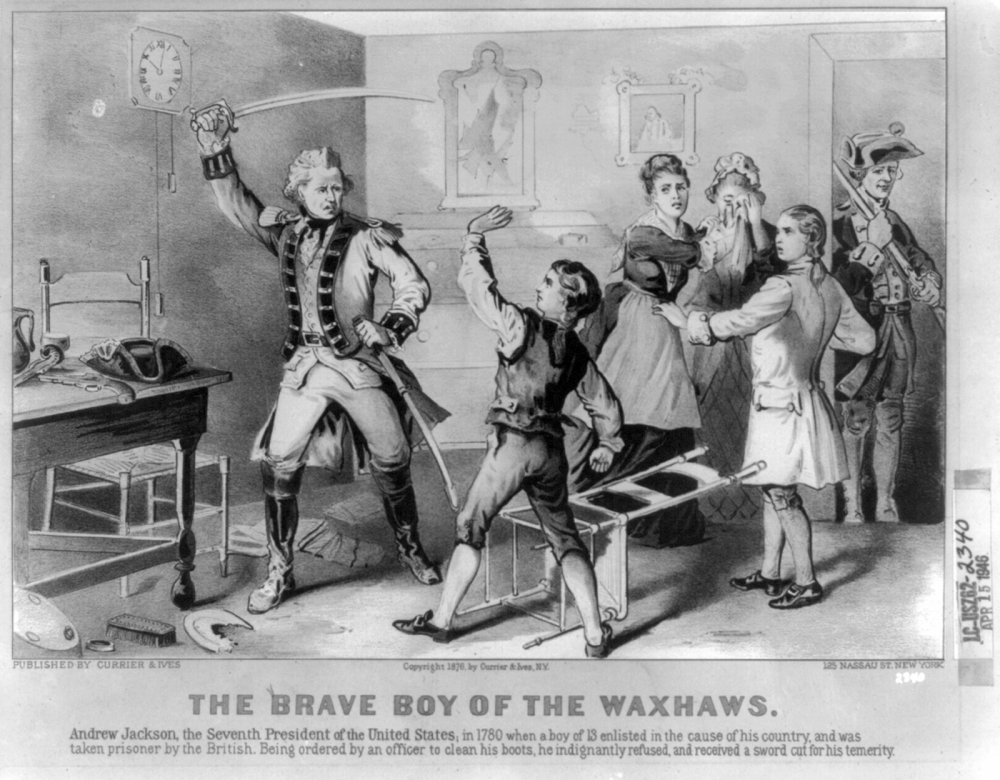

Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, on the border between North and South Carolina, to two immigrants from northern Ireland. He grew up during dangerous times. At age thirteen, he joined an American militia unit in the Revolutionary War. He was soon captured, and a British officer slashed at his head with a sword after he refused to shine the officer’s shoes. Disease during the war had claimed the lives of his two brothers and his mother, leaving him an orphan. Their deaths and his wounds had left Jackson with a deep and abiding hatred of Great Britain.

After the war, Jackson moved west to frontier Tennessee, where despite his poor education, he prospered, working as a lawyer and acquiring land and enslaved laborers. (He would eventually come to keep 150 enslaved laborers at the Hermitage, his plantation near Nashville.) In 1796, Jackson was elected as a U.S. representative, and a year later he won a seat in the Senate, although he resigned within a year, citing financial difficulties.

Thanks to his political connections, Jackson obtained a general’s commission at the outbreak of the War of 1812. Despite having no combat experience, General Jackson quickly impressed his troops, who nicknamed him “Old Hickory” after a particularly tough kind of tree.

Jackson led his militiamen into battle in the Southeast, first during the Creek War, a side conflict that started between different factions of Muskogee (Creek) fighters in present-day Alabama. In that war, he won a decisive victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. A year later, he also defeated a large British invasion force at the Battle of New Orleans. There, Jackson’s troops—including backwoods militiamen, free African Americans, Native Americans, and a company of slave-trading pirates—successfully defended the city and inflicted more than two thousand casualties against the British, sustaining barely three hundred casualties of their own. 9 The Battle of New Orleans was a thrilling victory for the United States, but it actually happened several days after a peace treaty was signed in Europe to end the war. News of the treaty had not yet reached New Orleans.

The end of the War of 1812 did not end Jackson’s military career. In 1818, as commander of the U.S. southern military district, Jackson also launched an invasion of Spanish-owned Florida. He was acting on vague orders from the War Department to break the resistance of the region’s Seminole people, who protected runaway enslaved people and attacked American settlers across the border. On Jackson’s orders in 1816, U.S. soldiers and their Creek allies had already destroyed the “Negro Fort,” a British-built fortress on Spanish soil, killing 270 formerly enslaved people and executing some survivors. 10 In 1818, Jackson’s troops crossed the border again. They occupied Pensacola, the main Spanish town in the region, and arrested two British subjects, whom Jackson executed for helping the Seminoles. The execution of these two Britons created an international diplomatic crisis.

Most officials in President James Monroe’s administration called for Jackson’s censure. But Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, the son of former president John Adams, found Jackson’s behavior useful. He defended the impulsive general, arguing that he had been forced to act. Adams used Jackson’s military successes in this First Seminole War to persuade Spain to accept the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, which gave Florida to the United States.

Images like this—showing a young Jackson defending his family from a British officer—established Jackson’s legend. Currier & Ives, The Brave Boy of the Waxhaws, 1876. Wikimedia .

Any friendliness between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, however, did not survive long. In 1824, four nominees competed for the presidency in one of the closest elections in American history. Each came from a different part of the country—Adams from Massachusetts, Jackson from Tennessee, William H. Crawford from Georgia, and Henry Clay from Kentucky. Jackson won more popular votes than anyone else. But with no majority winner in the Electoral College, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives. There, Adams used his political clout to claim the presidency, persuading Clay to support him. After his election, Adams then named Henry Clay the Secretary of State, a position that had often been held by politicians before winning the presidency. Jackson would never forgive Adams, whom his supporters accused of engineering a “corrupt bargain” with Clay to circumvent the popular will.

Four years later, in 1828, Adams and Jackson squared off in one of the dirtiest presidential elections to date. 11 Pro-Jackson partisans accused Adams of elitism and claimed that while serving in Russia as a diplomat he had offered the Russian emperor an American prostitute. Adams’s supporters, on the other hand, accused Jackson of murder and attacked the morality of his marriage, pointing out that Jackson had unwittingly married his wife Rachel before the divorce on her prior marriage was complete. This time, Andrew Jackson won the election easily, but Rachel Jackson died suddenly before his inauguration. Jackson would never forgive the people who attacked his wife’s character during the campaign.

In 1828, Jackson’s broad appeal as a military hero won him the presidency. He was “Old Hickory,” the “Hero of New Orleans,” a leader of plain frontier folk. His wartime accomplishments appealed to many voters’ pride. Over the next eight years, he would claim to represent the interests of ordinary white Americans, especially from the South and West, against the country’s wealthy and powerful elite. This attitude would lead him and his allies into a series of bitter political struggles.

Nearly every American had an opinion about President Jackson. To some, he epitomized democratic government and popular rule. To others, he represented the worst in a powerful and unaccountable executive, acting as president with the same arrogance he had shown as a general in Florida. One of the key issues dividing Americans during his presidency was a sectional dispute over national tax policy that would come to define Jackson’s no-holds-barred approach to government.

Once Andrew Jackson moved into the White House, most southerners expected him to do away with the hated Tariff of 1828, the so-called Tariff of Abominations. This import tax provided protection for northern manufacturing interests by raising the prices of European products in America. Southerners, however, blamed the tariff for a massive transfer of wealth. It forced them to purchase goods from the North’s manufacturers at higher prices, and it provoked European countries to retaliate with high tariffs of their own, reducing foreign purchases of the South’s raw materials.

Only in South Carolina, though, did the discomfort turn into organized action. The state was still trying to shrug off the economic problems of the Panic of 1819, but it had also recently endured the Denmark Vesey slave conspiracy, which convinced white South Carolinians that antislavery ideas put them in danger of a massive uprising.

Elite South Carolinians were especially worried that the tariff was merely an entering wedge for federal legislation that would limit slavery. Andrew Jackson’s own vice president, John C. Calhoun, who was from South Carolina, asserted that the tariff was “the occasion, rather than the real cause of the present unhappy state of things.” The real fear was that the federal government might attack “the peculiar domestick institution of the Southern States”—meaning slavery. 12 When Jackson failed to act against the tariff, Vice President Calhoun was caught in a tight position.

In 1828, Calhoun secretly drafted the “South Carolina Exposition and Protest,” an essay and set of resolutions that laid out the doctrine of nullification.” 13 Drawing from the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798 and 1799, Calhoun argued that the United States was a compact among the states rather than among the whole American people. Since the states had created the Union, he reasoned, they were still sovereign, so a state could nullify a federal statute it considered unconstitutional. Other states would then have to concede the right of nullification or agree to amend the Constitution. If necessary, a nullifying state could leave the Union.

When Calhoun’s authorship of the essay became public, Jackson was furious, interpreting it both as a personal betrayal and as a challenge to his authority as president. His most dramatic confrontation with Calhoun came in 1832 during a commemoration for Thomas Jefferson. At dinner, the president rose and toasted, “Our Federal Union: it must be preserved.” Calhoun responded with a toast of his own: “The Union: next to our Liberty the most dear.” 14 Their divorce was not pretty. Martin Van Buren, a New York political leader whose skill in making deals had earned him the nickname “the Little Magician,” replaced Calhoun as vice president when Jackson ran for reelection in 1832.

Calhoun returned to South Carolina, where a special state convention nullified the federal tariffs of 1828 and 1832. It declared them unconstitutional and therefore “null, void, and no law” within South Carolina. 15 The convention ordered South Carolina customs officers not to collect tariff revenue and declared that any federal attempt to enforce the tariffs would cause the state to secede from the Union.

President Jackson responded dramatically. He denounced the ordinance of nullification and declared that “disunion, by armed force, is TREASON.” 16 Vowing to hang Calhoun and any other nullifier who defied federal power, he persuaded Congress to pass a Force Bill that authorized him to send the military to enforce the tariffs. Faced with such threats, other southern states declined to join South Carolina. Privately, however, Jackson supported the idea of compromise and allowed his political enemy Henry Clay to broker a solution with Calhoun. Congress passed a compromise bill that slowly lowered federal tariff rates. South Carolina rescinded nullification for the tariffs but nullified the Force Bill.

The legacy of the Nullification Crisis is difficult to sort out. Jackson’s decisive action seemed to have forced South Carolina to back down. But the crisis also united the ideas of secession and states’ rights, two concepts that had not necessarily been linked before. Perhaps most clearly, nullification showed that the immense political power of enslavers was matched only by their immense anxiety about the future of slavery. During later debates in the 1840s and 1850s, they would raise the ideas of the Nullification Crisis again.

Meanwhile, a more personal crisis during Jackson’s first term also drove a wedge between him and Vice President Calhoun. The Eaton Affair, sometimes insultingly called the “Petticoat Affair,” began as a disagreement among elite women in Washington, D.C., but it eventually led to the disbanding of Jackson’s cabinet.

True to his backwoods reputation, when he took office in 1829, President Jackson chose mostly provincial politicians, not Washington veterans, to serve in his administration. One of them was his friend John Henry Eaton, a senator from Tennessee, whom Jackson nominated to be his secretary of war.

A few months earlier, Eaton had married Margaret O’Neale Timberlake, the recent widow of a navy officer. She was the daughter of Washington boardinghouse proprietors, and her humble origins and combination of beauty, outspokenness, and familiarity with so many men in the boardinghouse had led to gossip. During her first marriage, rumors had circulated that she and John Eaton were having an affair while her husband was at sea. When her first husband’s death was originally (but incorrectly) labeled a suicide, and she married Eaton just nine months later, the society women of Washington had been scandalized. One wrote that Margaret Eaton’s reputation had been “totally destroyed.” 17

This photograph shows Eaton at a much older age. “Eaton, Mrs. Margaret (Peggy O’Neill), old lady,” c. 1870-1880. Library of Congress .

John Eaton was now secretary of war, but other cabinet members’ wives refused have anything to do with his wife. No respectable lady who wanted to protect her own reputation could exchange visits with her, invite her to social events, or be seen chatting with her. Most importantly, the vice president’s wife, Floride Calhoun, shunned Margaret Eaton, spending most of her time in South Carolina to avoid her. Even Jackson’s own niece, Emily Donelson, visited Eaton once and then refused to have anything more to do with her.

Although women could not vote or hold office, they played an important role in politics as people who controlled influence. 18 They helped hold official Washington together. And according to one local society woman, “the ladies” had “as much rivalship and party spirit, desire of precedence and authority” as male politicians had. 19 These women upheld a strict code of femininity and sexual morality. They paid careful attention to the rules that governed personal interactions and official relationships.

Margaret Eaton’s social exclusion thus greatly affected Jackson, his cabinet, and the rest of Washington society. At first, President Jackson blamed his rival Henry Clay for the attacks on the Eatons. But he soon perceived that Washington women and his new cabinet had initiated the gossip. Jackson scoffed, “I did not come here to make a cabinet for the ladies of this place,” and claimed that he “had rather have live vermin on my back than the tongue of one of these Washington women on my reputation.” 20 He began to blame the ambition of Vice President Calhoun for Floride Calhoun’s actions, deciding “it was necessary to put him out of the cabinet and destroy him.” 21

Jackson was so indignant because he had recently been through a similar scandal with his late wife, Rachel. Her character, too, had been insulted by leading politicians’ wives because of the circumstances of her marriage. Jackson believed that Rachel’s death had been caused by those slanderous attacks. Furthermore, he saw the assaults on the Eatons as attacks on his authority.

In one of the most famous presidential meetings in American history, Jackson called together his cabinet members to discuss what they saw as the bedrock of society: women’s position as protectors of the nation’s values. There, the men of the cabinet debated Margaret Eaton’s character. Jackson delivered a long defense, methodically presenting evidence against her attackers. But the men attending the meeting—and their wives—were not swayed. They continued to shun Margaret Eaton, and the scandal was resolved only with the resignation of four members of the cabinet, including Eaton’s husband.

Andrew Jackson’s first term was full of controversy. For all of his reputation as a military and political warrior, however, the most characteristic struggle of his presidency was financial. As president, he waged a “war” against the Bank of the United States.

The charter of the controversial national bank that Congress established under Alexander Hamilton’s financial plan had expired in 1811. But five years later, Congress had given a new charter to the Second Bank of the United States. Headquartered in Philadelphia, the bank was designed to stabilize the growing American economy. By requiring other banks to pay their debts promptly in gold, it was supposed to prevent them from issuing too many paper banknotes that could drop suddenly in value. Of course, the Bank of the United States was also supposed to reap a healthy profit for its private stockholders, like the Philadelphia banker Stephen Girard and the New York merchant John Jacob Astor.

Though many Democratic-Republicans had supported the new bank, some never gave up their Jeffersonian suspicion that such a powerful institution was dangerous to the republic. Andrew Jackson was one of the skeptics. He and many of his supporters blamed the bank for the Panic of 1819, which had become a severe economic depression. The national bank had made that crisis worse, first by lending irresponsibly and then, when the panic hit, by hoarding gold currency to save itself at the expense of smaller banks and their customers. Jackson’s supporters also believed the bank had corrupted many politicians by giving them financial favors.

In 1829, after a few months in office, Jackson set his sights on the bank and its director, Nicholas Biddle. Jackson became more and more insistent over the next three years as Biddle and the bank’s supporters fought to save it. A visiting Frenchman observed that Jackson had “declared a war to the death against the Bank,” attacking it “in the same cut-and-thrust style” with which he had once fought Native Americans and the British. For Jackson, the struggle was a personal crisis. “The Bank is trying to kill me,” he told Martin Van Buren, “but I will kill it!” 22

The bank’s charter was not due for renewal for several years, but in 1832, while Jackson was running for reelection, Congress held an early vote to reauthorize the Bank of the United States. The president vetoed the bill.

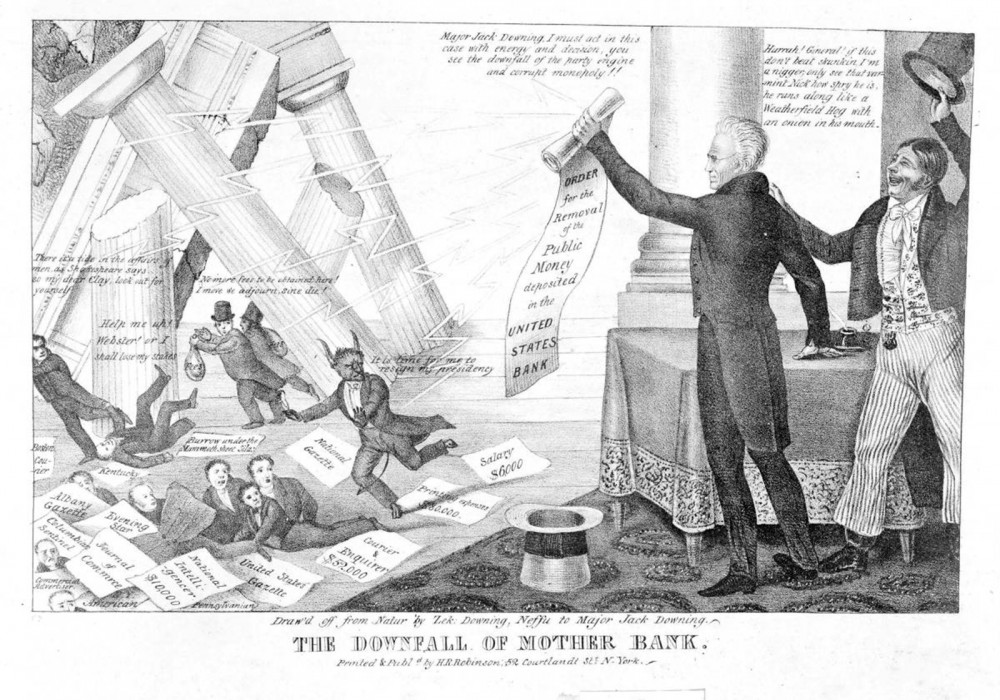

“The bank,” Andrew Jackson told Martin Van Buren, “is trying to kill me, but I will kill it!” That is just the unwavering force that Edward Clay depicted in this lithograph, which praised Jackson for terminating the Second Bank of the United States. Clay shows Nicholas Biddle as the Devil running away from Jackson as the bank collapses around him, his hirelings, and speculators. Edward W. Clay, c. 1832. Wikimedia .

In his veto message, Jackson called the bank unconstitutional and “dangerous to the liberties of the people.” The charter, he explained, didn’t do enough to protect the bank from its British stockholders, who might not have Americans’ interests at heart. In addition, Jackson wrote, the Bank of the United States was virtually a federal agency, but it had powers that were not granted anywhere in the Constitution. Worst of all, the bank was a way for well-connected people to get richer at everyone else’s expense. “The rich and powerful,” the president declared, “too often bend the acts of government to their selfish purposes.” 23 Only a strictly limited government, Jackson believed, would treat people equally.

Although its charter would not be renewed, the Bank of the United States could still operate for several more years. So in 1833, to diminish its power, Jackson also directed his cabinet to stop depositing federal funds in it. From now on, the government would do business with selected state banks instead. Critics called them Jackson’s “pet banks.”

Jackson’s bank veto set off fierce controversy. Opponents in Philadelphia held a meeting and declared that the president’s ideas were dangerous to private property. Jackson, they said, intended to “place the honest earnings of the industrious citizen at the disposal of the idle”—in other words, redistribute wealth to lazy people—and become a “dictator.” 24 A newspaper editor said that Jackson was trying to set “the poor against the rich,” perhaps in order to take over as a military tyrant. 25 But Jackson’s supporters praised him. Pro-Jackson newspaper editors wrote that he had kept a “monied aristocracy” from conquering the people. 26

By giving President Jackson a vivid way to defy the rich and powerful, or at least appear to do so, the Bank War gave his supporters a specific “democratic” idea to rally around. More than any other issue, opposition to the national bank came to define their beliefs. And by leading Jackson to exert executive power so dramatically against Congress, the Bank War also helped his political enemies organize.

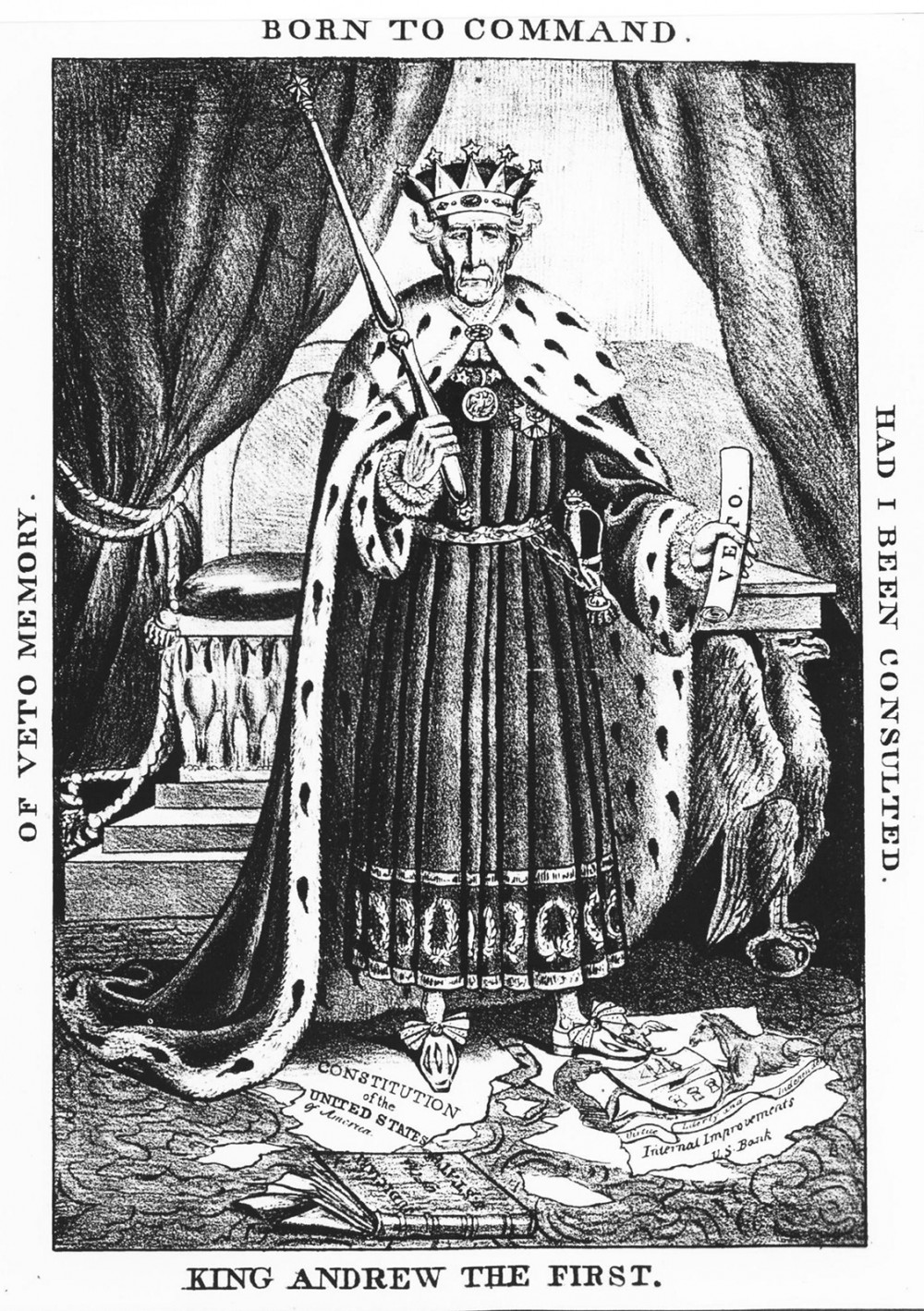

Increasingly, supporters of Andrew Jackson referred to themselves as Democrats. Under the strategic leadership of Martin Van Buren, they built a highly organized national political party, the first modern party in the United States. Much more than earlier political parties, this Democratic Party had a centralized leadership structure and a consistent ideological program for all levels of government. Meanwhile, Jackson’s enemies, mocking him as “King Andrew the First,” named themselves after the patriots of the American Revolution, the Whigs.

Unfortunately for Jackson’s Democrats (and most other Americans), their victory over the Bank of the United States worsened rather than solved the country’s economic problems.

Things looked good initially. Between 1834 and 1836, a combination of high cotton prices, freely available foreign and domestic credit, and an infusion of specie (“hard” currency in the form of gold and silver) from Europe spurred a sustained boom in the American economy. At the same time, sales of western land by the federal government promoted speculation and poorly regulated lending practices, creating a vast real estate bubble.

Meanwhile, the number of state-chartered banks grew from 329 in 1830 to 713 just six years later. As a result, the volume of paper banknotes per capita in circulation in the United States increased by 40 percent between 1834 and 1836. Low interest rates in Great Britain also encouraged British capitalists to make risky investments in America. British lending across the Atlantic surged, raising American foreign indebtedness from $110 million to $220 million over the same two years. 27

As the boom accelerated, banks became more careless about the amount of hard currency they kept on hand to redeem their banknotes. And although Jackson had hoped his bank veto would reduce bankers’ and speculators’ power over the economy, it actually made the problems worse.

Two further federal actions late in the Jackson administration also worsened the situation. In June 1836, Congress decided to increase the number of banks receiving federal deposits. This plan undermined the banks that were already receiving federal money, since they saw their funds distributed to other banks. Next, seeking to reduce speculation on credit, the Treasury Department issued an order called the Specie Circular in July 1836, requiring payment in hard currency for all federal land purchases. As a result, land buyers drained eastern banks of even more gold and silver.

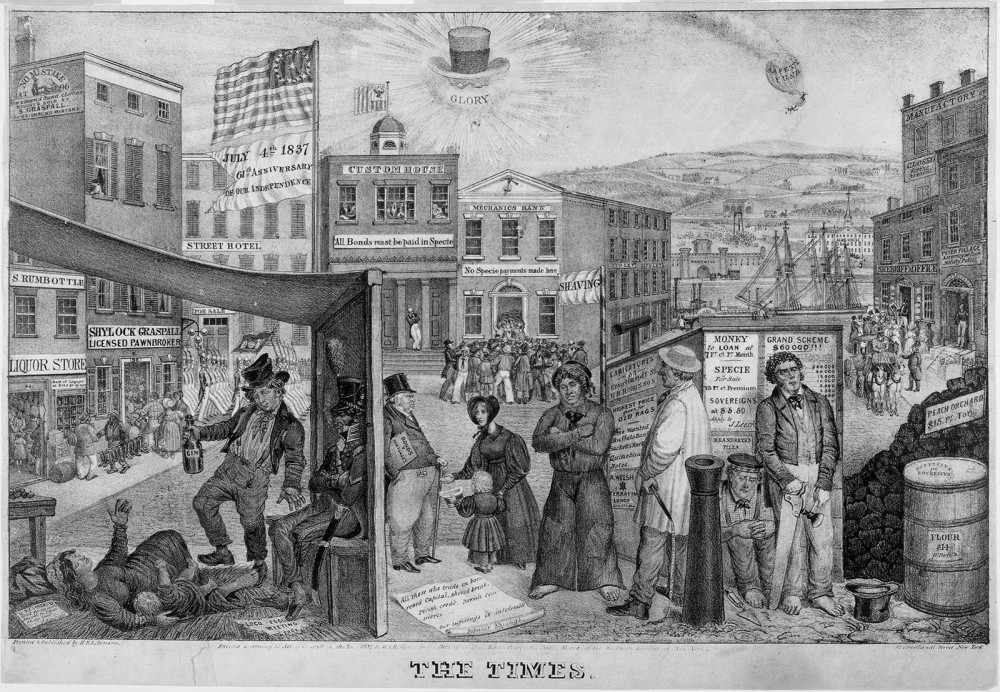

By late fall in 1836, America’s economic bubbles began to burst. Federal land sales plummeted. The New York Herald reported that “lands in Illinois and Indiana that were cracked up to $10 an acre last year, are now to be got at $3, and even less.” The newspaper warned darkly, “The reaction has begun, and nothing can stop it.” 28

Runs on banks began in New York on May 4, 1837, as panicked customers scrambled to exchange their banknotes for hard currency. By May 10, the New York banks, running out of gold and silver, stopped redeeming their notes. As news spread, banks around the nation did the same. By May 15, the largest crowd in Pennsylvania history had amassed outside Independence Hall in Philadelphia, denouncing banking as a “system of fraud and oppression.” 29

The Panic of 1837 led to a general economic depression. Between 1839 and 1843, the total capital held by American banks dropped by 40 percent as prices fell and economic activity around the nation slowed to a crawl. The price of cotton in New Orleans, for instance, dropped 50 percent. 30

Traveling through New Orleans in January 1842, a British diplomat reported that the country “presents a lamentable appearance of exhaustion and demoralization.” 31 Over the previous decade, the American economy had soared to fantastic new heights and plunged to dramatic new depths.

Many Americans blamed the Panic of 1837 on the economic policies of Andrew Jackson, who is sarcastically represented in the lithograph as the sun with top hat, spectacle, and a banner of “Glory” around him. The destitute people in the foreground (representing the common man) are suffering while a prosperous attorney rides in an elegant carriage in the background (right side of frame). Edward W. Clay, “The Times,” 1837. Wikimedia .

Normal banking activity did not resume around the nation until late 1842. Meanwhile, two hundred banks closed, cash and credit became scarce, prices declined, and trade slowed. During this downturn, eight states and a territorial government defaulted on loans made by British banks to finance internal improvements. 32

The disaster of the Panic of 1837 created an opportunity for the Whig Party, which had grown partly out of the political coalition of John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay and opposed Andrew Jackson and the Democratic Party. The National Republicans, a loose alliance concentrated in the Northeast, had become the core of a new anti-Jackson movement. But Jackson’s enemies were a varied group; they included pro-slavery southerners angry about Jackson’s behavior during the Nullification Crisis as well as antislavery Yankees.

After they failed to prevent Andrew Jackson’s reelection, this fragile coalition formally organized as a new party in 1834 “to rescue the Government and public liberty.” 33 Henry Clay, who had run against Jackson for president and was now serving again as a senator from Kentucky, held private meetings to persuade anti-Jackson leaders from different backgrounds to unite. He also gave the new Whig Party its anti-monarchical name.

At first, the Whigs focused mainly on winning seats in Congress, opposing “King Andrew” from outside the presidency. They remained divided by regional and ideological differences. The Democratic presidential candidate, Vice President Martin Van Buren, easily won election as Jackson’s successor in 1836. But the Whigs gained significant public support after the Panic of 1837, and they became increasingly well organized. In late 1839, they held their first national convention in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Andrew Jackson portrayed himself as the defender of the common man, and in many ways he democratized American politics. His opponents, however, zeroed in on Jackson’s willingness to utilize the powers of the executive office. Unwilling to defer to Congress and absolutely willing to use his veto power, Jackson came to be regarded by his adversaries as a tyrant (or, in this case, “King Andrew I”.) Anonymous, c. 1832. Wikimedia .

To Henry Clay’s disappointment, the convention voted to nominate not him but General William Henry Harrison of Ohio as the Whig candidate for president in 1840. Harrison was known primarily for defeating Shawnee warriors led by Tecumseh before and during the War of 1812, most famously at the Battle of Tippecanoe in present-day Indiana. Whig leaders viewed him as a candidate with broad patriotic appeal. They portrayed him as the “log cabin and hard cider” candidate, a plain man of the country, unlike the easterner Martin Van Buren. To balance the ticket with a southerner, the Whigs nominated a slave-owning Virginia senator, John Tyler, for vice president. Tyler had been a Jackson supporter but had broken with him over states’ rights during the Nullification Crisis.

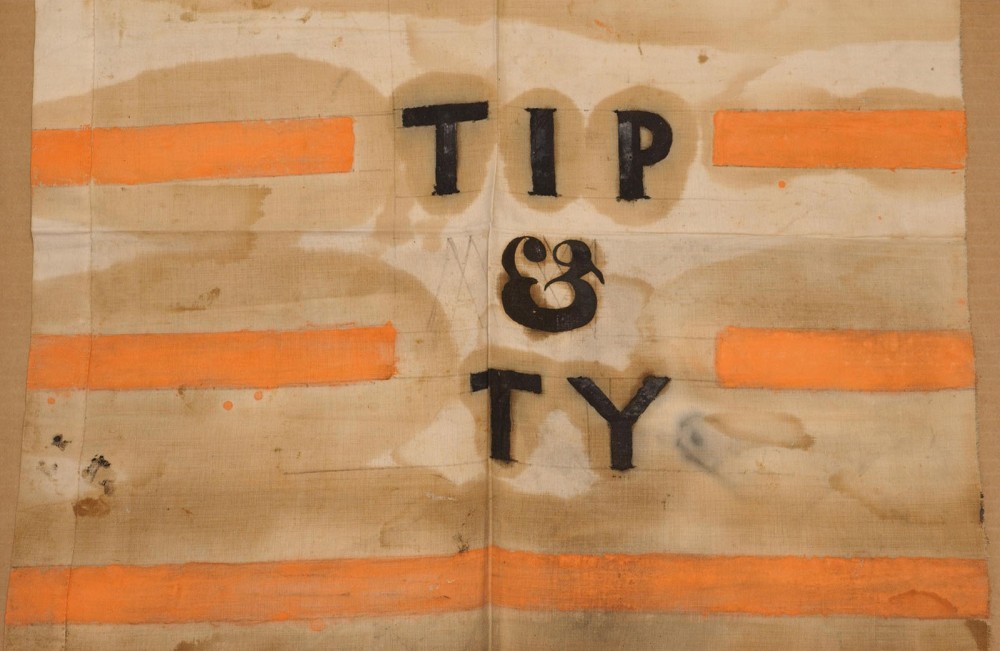

The popular slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” helped the Whigs and William Henry Harrison (with John Tyler) win the presidential election in 1840. Pictured here is a campaign banner with shortened “Tip and Ty,” one of the many ways that Whigs waged the “log cabin campaign,” Wikimedia .

Although “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” easily won the presidential election of 1840, this choice of ticket turned out to be disastrous for the Whigs. Harrison became ill (for unclear reasons, though tradition claims he contracted pneumonia after delivering a nearly two-hour inaugural address without an overcoat or hat) and died after just thirty-one days in office. Harrison thus holds the ironic honor of having the longest inaugural address and the shortest term in office of any American president. 34 Vice President Tyler became president and soon adopted policies that looked far more like Andrew Jackson’s than like a Whig’s. After Tyler twice vetoed charters for another Bank of the United States, nearly his entire cabinet resigned, and the Whigs in Congress expelled “His Accidency” from the party.

The crisis of Tyler’s administration was just one sign of the Whig Party’s difficulty uniting around issues besides opposition to Democrats. The Whig Party succeeded in electing one more president but remained deeply divided. Its problems grew as the issue of slavery strained the Union in the 1850s. Unable to agree on a consistent national position on slavery, and unable to find another national issue to rally around, the Whigs broke apart by 1856.