- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Cyberbullying in adolescents: a literature review

Cyberbullying is a universal public health concern that affects adolescents. The growing usage of electronic gadgets and the Internet has been connected to a rise in cyberbullying. The increasing use of the Internet, along with the negative outcomes of cyberbullying on adolescents, has required the study of cyberbullying. In this paper author reviews existing literature on cyberbullying among adolescents. The concept of cyberbullying is explained, including definitions, types of cyberbullying, characteristics or features of victims and cyberbullies, risk factors or causes underlying cyberbullying, and the harmful consequences of cyberbullying to adolescents. Furthermore, examples of programs or intervention to prevent cyberbullying and recommendations for further studies are presented.

Research funding: None declared.

Author contributions: Author has accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Competing interests: Author states no conflict of interest.

Informed consent: Not applicable.

Ethical approval: Not applicable.

1. Ovigli, D, Colombo, P. Information and communication technologies (ICT) in educational research in science museums in Brazil. IJEDICT 2020;16:272–86. Search in Google Scholar

2. Eleuteri, S, Saladino, V, Verrastro, V. Identity, relationships, sexuality, and risky behaviors of adolescents in the context of social media. Sex Relatsh Ther 2017;32:354–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2017.1397953 . Search in Google Scholar

3. Saladino, V, Eleuteri, S, Verrastro, V, Petruccelli, F. Perception of cyberbullying in adolescence: a brief evaluation among Italian students. Front Psychol 2020;11:1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.607225 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

4. Beale, AV, Hall, KR. Cyberbullying: what school administrators (and parents) can do. Clearing House 2007;81:8–12. https://doi.org/10.3200/tchs.81.1.8-12 . Search in Google Scholar

5. Brody, N, Vangelisti, AL. Bystander intervention in cyberbullying. Commun Monogr 2016;83:94–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2015.1044256 . Search in Google Scholar

6. Athanasiou, K, Melegkovits, E, Andrie, EK, Magoulas, C, Tzavara, CK, Richardson, C. Cross-national aspects of cyberbullying victimization among 14–17-year-old adolescents across seven European countries. BMC Publ Health 2018;18:800. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5682-4 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. González-Cabrera, J, Tourón, J, Machimbarrena, JM, Gutiérrez-Ortega, M, Álvarez-Bardón, A, Garaigordobil, M. Cyberbullying in gifted students: prevalence and psychological well-being in a Spanish sample. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:2173. 10.3390/ijerph16122173 Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

8. Lee, C, Shin, N. Prevalence of cyberbullying and predictors of cyberbullying perpetration among Korean adolescents. Comput Hum Behav 2017;68:352–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.047 . Search in Google Scholar

9. Safaria, T. Prevalence and impact of cyberbullying in a sample of Indonesian junior high school students. The Turk Online J Educ Technol 2016;15:82–91. Search in Google Scholar

10. Lee, M-S, Wu, W, Svanström, L, Dalal, K. Cyber bullying prevention: intervention in Taiwan. PLoS One 2013;8:e64031. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064031 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

11. Whittaker, E, Kowalski, RM. Cyberbullying via social media. J Sch Violence 2015;14:11–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2014.949377 . Search in Google Scholar

12. Vaillancourt, T, Faris, R, Mishna, F. Cyberbullying in children and youth: implications for health and clinical practice. Can J Psychiatry 2016;62:368–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716684791 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

13. Nixon, C. Current perspectives: the impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health. Adolesc Health Med Ther 2014;5:143–58. https://doi.org/10.2147/ahmt.s36456 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

14. Heiman, T, Shemesh, D. Cyberbullying experience and gender differences among adolescents in different educational settings. J Learn Disabil 2013;48:146–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219413492855 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Paris, S, Robert, D. Cyberbullying by adolescents: a preliminary assessment. Educ Forum 2006;70:21–36. 10.1080/00131720508984869 Search in Google Scholar

16. Patchin, JW, Hinduja, S. Bullies move beyond the schoolyard A preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence Juv Justice 2006;4:148–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204006286288 . Search in Google Scholar

17. Kowalski, RM, Limber, SP. Electronic bullying among middle school students. J Adolesc Health 2007;41(6 Suppl 1):S22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.017 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

18. Raskauskas, J, Stoltz, AD. Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Dev Psychol 2007;43:564–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

19. Menesini, E, Nocentini, A, Palladino, BE, Frisén, A, Berne, S, Rosario, R. Cyberbullying definition among adolescents: a comparison across six European countries. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2012;15:455–63. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0040 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Dooley, JJ, Pyżalski, J, Cross, D. Cyberbullying versus face-to-face bullying: a theoretical and conceptual review. Z Psychol 2009;217:182–8. https://doi.org/10.1027/0044-3409.217.4.182 . Search in Google Scholar

21. Nocentini, A, Calmaestra, J, Anja, A, Scheithauer, H, Ortega, R, Menesini, E. Cyberbullying: labels, behaviours and definition in three European countries. Aust J Guid Counsell 2010;20:129–42. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.20.2.129 . Search in Google Scholar

22. Aboujaoude, E, Savage, MW, Starcevic, V, Salame, WO. Cyberbullying: review of an old problem gone viral. J Adolesc Health 2015;57:10–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.011 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

23. Ferrara, P, Ianniello, F, Villani, A, Corsello, G. Cyberbullying a modern form of bullying: let’s talk about this health and social problem. Ital J Pediatr 2018;44:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-018-0446-4 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

24. Smith, PK, Mahdavi, J, Carvalho, M, Fisher, S, Russell, S, Tippett, N. Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. JCPP (J Child Psychol Psychiatry) 2008;49:376–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01846.x . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

25. Garett, R, Lord, LR, Young, SD. Associations between social media and cyberbullying: a review of the literature. mHealth 2016;2:46. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2016.12.01 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

26. Li, Q. Bullying in the new playground: research into cyberbullying and cyber victimisation. Australas J Educ Technol 2007;23:435–54. 10.14742/ajet.1245 Search in Google Scholar

27. Zeljka, D, Vesna, C, Rajkovača, I, Včev, A, Miskic, D, Miskic, B. Cyberbullying in early adolescence: is there a difference between urban and rural environment? Am J Biomed Sci Res 2019;1:191–6. 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.01.000542 Search in Google Scholar

28. Ybarra, ML, Mitchell, KJ, Wolak, J, Finkelhor, D. Examining characteristics and associated distress related to internet harassment: findings from the second youth internet safety survey. Pediatrics 2006;118:e1169–77. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-0815 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Li, Q. Cyberbullying in schools: a research of gender differences. Sch Psychol Int 2006;27:157–70. 10.1177/0143034306064547 Search in Google Scholar

30. Ybarra, ML, Mitchell, KJ. Youth engaging in online harassment: associations with caregiver–child relationships, Internet use, and personal characteristics. J Adolesc 2004;27:319–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-1971(04)00039-9 . Search in Google Scholar

31. Dhond, V, Richter, S, McKenna, B, editors. Exploratory research to identify the characteristics of cyber victims on social media in New Zealand . Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. 10.1007/978-3-030-11395-7_18 Search in Google Scholar

32. Ybarra, ML, Mitchell, KJ. Prevalence and frequency of Internet harassment instigation: implications for adolescent health. J Adolesc Health 2007;41:189–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.005 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Zhong, J, Zheng, Y, Huang, X, Mo, D, Gong, J, Li, M. Study of the influencing factors of cyberbullying among Chinese college students incorporated with digital citizenship: from the perspective of individual students. Front Psychol 2021;12:621418. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.621418 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

34. Wong-Lo, M, Bullock, LM, Gable, RA. Cyber bullying: practices to face digital aggression. Emot Behav Difficulties 2011;16:317–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632752.2011.595098 . Search in Google Scholar

35. Barlett, C, Gentile, D. Attacking others online: the formation of cyberbullying in late adolescence. Psychol Popular Media Culture 2012;1:123–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028113 . Search in Google Scholar

36. Mason. Cyberbullying: a preliminary assessment for school personnel. Psychol Sch 2008;45:323–48. 10.1002/pits.20301 Search in Google Scholar

37. Pratto, F, Stewart, AL, Zeineddine, F. When inequality fails: power, group dominance, and societal change. J Soc Polit Psychol 2013;1:132–60. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v1i1.97 . Search in Google Scholar

38. Koski, JE, Xie, H, Olson, IR. Understanding social hierarchies: the neural and psychological foundations of status perception. Soc Neurosci 2015;10:527–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2015.1013223 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

39. Walker, C, Sockman, B, Koehn, S. An exploratory study of cyberbullying with undergraduate university students. TechTrends 2011;55:31–8. 10.1007/s11528-011-0481-0 Search in Google Scholar

40. Pratto, F, Sidanius, J, Levin, S. Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 2006;17:271–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280601055772 . Search in Google Scholar

41. Sidanius, J, Pratto, F, Van Laar, C, Levin, S. Social dominance theory: its agenda and method. Polit Psychol 2004;25:845–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00401.x . Search in Google Scholar

42. Closson, LM. Aggressive and prosocial behaviors within early adolescent friendship cliques: what’s status got to do with it? Merrill-Palmer Q 2009;55:406–35. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0035 . Search in Google Scholar

43. Salmivalli, C, Kärnä, A, Poskiparta, E. Counteracting bullying in Finland: the KiVa program and its effect on different forms of being bullied. IJBD (Int J Behav Dev) 2011;35:405–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025411407457 . Search in Google Scholar

44. Chisholm, JF. Review of the status of cyberbullying and cyberbullying prevention. J Inf Syst Educ 2014;25:77–87. Search in Google Scholar

45. Bonanno, RA, Hymel, S. Cyber bullying and internalizing difficulties: above and beyond the impact of traditional forms of bullying. J Youth Adolesc 2013;42:685–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9937-1 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

46. Wolke, D, Copeland, WE, Angold, A, Costello, EJ. Impact of bullying in childhood on adult health, wealth, crime, and social outcomes. Psychol Sci 2013;24:1958–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613481608 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

47. Foody, M, Samara, M, Carlbring, P. A review of cyberbullying and suggestions for online psychological therapy. Internet Interv 2015;2:235–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2015.05.002 . Search in Google Scholar

48. Dredge, R, Gleeson, J, Garcia, X. Cyberbullying in social networking sites: an adolescent victim’s perspective. Comput Hum Behav 2014;36:13–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.026 . Search in Google Scholar

49. Schenk, AM, Fremouw, WJ. Prevalence, psychological impact, and coping of cyberbully victims among college students. J Sch Violence 2012;11:21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2011.630310 . Search in Google Scholar

50. Burger, C, Bachmann, L. Perpetration and victimization in offline and cyber contexts: a variable- and person-oriented examination of associations and differences regarding domain-specific self-esteem and school adjustment. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2021;18:10429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910429 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

51. Price, M, Dalgleish, J. Cyberbullying: experiences, impacts and coping strategies as described by Australian young people. Youth Stud Aust 2010;29:51–9. Search in Google Scholar

52. Jang, H, Song, J, Kim, R. Does the offline bully-victimization influence cyberbullying behavior among youths? Application of General Strain Theory. Comput Hum Behav 2014;31:85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.007 . Search in Google Scholar

53. Ybarra, ML, West, M, Leaf, PJ. Examining the overlap in internet harassment and school bullying: implications for school intervention. J Adolesc Health 2007;41(6 Suppl 1):S42–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.004 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

54. Mishna, F, Kassabri, M, Gadalla, T, Daciuk, J. Risk factors or involvement in cyber bullying: victims, bullies and bully–victims. Child Youth Serv Rev 2012;34:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.08.032 . Search in Google Scholar

55. Wong, DSW, Chan, HC, Cheng, CHK. Cheng. Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among adolescents in Hong Kong. Child Youth Serv Rev 2014;36:133–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.11.006 . Search in Google Scholar

56. Bauman, S, Toomey, RB, Walker, JL. Associations among bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide in high school students. J Adolesc 2013;36:341–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.12.001 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

57. Fletcher, A, Yau, N, Jones, R, Allen, E, Viner, RM, Bonell, C. Brief report: cyberbullying perpetration and its associations with socio-demographics, aggressive behaviour at school, and mental health outcomes. J Adolesc 2014;37:1393–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.10.005 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

58. Kraft, EM, Wang, J. Effectiveness of cyber bullying prevention strategies: a study on students’ perspectives. Int J Cyber Criminol 2009;3:513. Search in Google Scholar

59. Williford, A, Elledge, LC, Boulton, AJ, DePaolis, KJ, Little, TD, Salmivalli, C. Effects of the KiVa antibullying program on cyberbullying and cybervictimization frequency among Finnish youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2013;42:820–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.787623 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

60. Menesini, E, Zambuto, V, Palladino, BE. 10 - online and school-based programs to prevent cyberbullying among Italian adolescents: what works, why, and under which circumstances. In: Campbell, M, Bauman, S, editors. Reducing cyberbullying in schools . Cambridge: Academic Press; 2018:35–43 pp. 10.1016/B978-0-12-811423-0.00010-9 Search in Google Scholar

61. David, A, Rio, J, Pueyo, A, Calvo, G. Effects of a cooperative learning intervention program on cyberbullying in secondary education: a case study. Qual Rep 2019;24:2426–40. Search in Google Scholar

62. Leung, ANM, Wong, N, Farver, JM. Farver. Testing the effectiveness of an E-course to combat cyberbullying. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2019;22:569–77. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0609 . Search in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Barón, J, Buelga, S, Ayllón, E, Ferrer, B, Cava, M. Effects of intervention program Prev@cib on traditional bullying and cyberbullying. Int J Environ Res Publ Health 2019;16:527. 10.3390/ijerph16040527 Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Doane, A, Ehlke, S, Kelley, M. Bystanders against cyberbullying: a video program for college students. Int J Bull Prev 2020;2:41–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-019-00051-5 . Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Journal and Issue

Articles in the same issue.

Cyberbullying: A Systematic Literature Review to Identify the Factors Impelling University Students Towards Cyberbullying

Ieee account.

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

Cyberbullying in adolescents: a literature review

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Health Education and Behavioral Sciences, Faculty of Public Health, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

- PMID: 35245420

- DOI: 10.1515/ijamh-2021-0133

Cyberbullying is a universal public health concern that affects adolescents. The growing usage of electronic gadgets and the Internet has been connected to a rise in cyberbullying. The increasing use of the Internet, along with the negative outcomes of cyberbullying on adolescents, has required the study of cyberbullying. In this paper author reviews existing literature on cyberbullying among adolescents. The concept of cyberbullying is explained, including definitions, types of cyberbullying, characteristics or features of victims and cyberbullies, risk factors or causes underlying cyberbullying, and the harmful consequences of cyberbullying to adolescents. Furthermore, examples of programs or intervention to prevent cyberbullying and recommendations for further studies are presented.

Keywords: adolescents; cyberbullying; literature review.

© 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston.

Publication types

- Adolescent Behavior*

- Bullying* / prevention & control

- Crime Victims*

- Cyberbullying*

- Risk Factors

Cyberbullying detection and machine learning: a systematic literature review

- Published: 24 July 2023

- Volume 56 , pages 1375–1416, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Vimala Balakrisnan 1 &

- Mohammed Kaity 1

781 Accesses

Explore all metrics

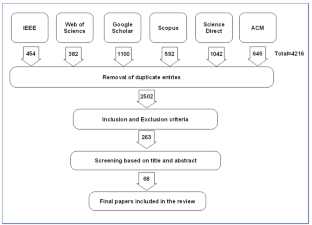

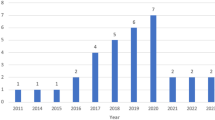

The rise in research work focusing on detection of cyberbullying incidents on social media platforms particularly reflect how dire cyberbullying consequences are, regardless of age, gender or location. This paper examines scholarly publications (i.e., 2011–2022) on cyberbullying detection using machine learning through a systematic literature review approach. Specifically, articles were sought from six academic databases (Web of Science, ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore, Association for Computing Machinery, Scopus, and Google Scholar), resulting in the identification of 4126 articles. A redundancy check followed by eligibility screening and quality assessment resulted in 68 articles included in this review. This review focused on three key aspects, namely, machine learning algorithms used to detect cyberbullying, features, and performance measures, and further supported with classification roles, language of study, data source and type of media. The findings are discussed, and research challenges and future directions are provided for researchers to explore.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Can Machine Learning Really Detect Cyberbullying?

Leevesh Pokhun & Yasser M. Chuttur

Harnessing the Power of Interdisciplinary Research with Psychology-Informed Cyberbullying Detection Models

Deborah L. Hall, Yasin N. Silva, … Katie Baumel

Cyber Analyzer—A Machine Learning Approach for the Detection of Cyberbullying—A Survey

https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2011-01-01%202022-12-31&q=deep%20learning&hl=en .

Agrawal S, Awekar A (2018) Deep learning for detecting cyberbullying across multiple social media platforms. In European Conference on Information Retrieval (pp. 141–153). Springer, Cham

Aizenkot D, Kashy-Rosenbaum G (2018) Cyberbullying in WhatsApp classmates’ groups: evaluation of an intervention program implemented in israeli elementary and middle schools. New Media & Society 20(12):4709–4727

Article Google Scholar

Akhter MP, Zheng JB, Naqvi IR, Abdelmajeed M, Sadiq MT (2020) Automatic Detection of Offensive Language for Urdu and Roman Urdu. IEEE Access 8:91213–91226.

Aldhyani TH, Al-Adhaileh MH, Alsubari SN (2022) Cyberbullying identification system based deep learning algorithms. Electronics 11(20):3273

Al-Garadi MA, Hussain MR, Khan N, Murtaza G, Nweke HF, Ali I, …, Gani A (2019) Predicting cyberbullying on social media in the big data era using machine learning algorithms: review of literature and open challenges. IEEE Access 7:70701–70718

Al-garadi MA, Varathan KD, Ravana SD (2016) Cybercrime detection in online communications: the experimental case of cyberbullying detection in the Twitter network. Comput Hum Behav 63:433–443

Al-Harigy LM, Al-Nuaim HA, Moradpoor N, Tan Z (2022) Building towards Automated Cyberbullying Detection: A Comparative Analysis. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022

Alom Z, Carminati B, Ferrari E (2020) A deep learning model for Twitter spam detection. Online Social Networks and Media 18:100079

Alpaydin E (2010) Introduction to machine learning, 2nd edn. MIT Press

Ates EC, Bostanci E, Guzel MS (2021) Comparative performance of machine learning algorithms in cyberbullying detection: using turkish language preprocessing techniques. arXiv preprint arXiv :2101.12718

Ayo FE, Folorunso O, Ibharalu FT, Osinuga IA (2020) Machine learning techniques for hate speech classification of twitter data: state-of-the-art, future challenges and research directions. Comput Sci Rev 38:100311

Balakrishnan V (2015) Cyberbullying among young adults in Malaysia: the roles of gender, age and internet frequency. Comput Hum Behav 46:149–157

Balakrishnan V, Khan S, Arabnia HR (2020a) Improving cyberbullying detection using Twitter users’ psychological features and machine learning. Computers & Security 90:101710

Balakrishnan V, Khan S, Arabnia HR (2020b) Improving cyberbullying detection using Twitter users’ psychological features and machine learning. Computers & Security 90:101710

Balakrishnan V, Khan S, Fernandez T, Arabnia HR (2019) Cyberbullying detection on twitter using Big Five and Dark Triad features. Pers Individ Differ 141, 252–257.

Bretschneider U, Wöhner T, Peters R (2014) Detecting online harassment in social networks.

Buan TA, Ramachandra R (2020) Automated Cyberbullying Detection in Social Media Using an SVM Activated Stacked Convolution LSTM Network. In Proceedings of the 2020 the 4th International Conference on Compute and Data Analysis (pp. 170–174)

Camerini AL, Marciano L, Carrara A, Schulz PJ (2020) Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among children and adolescents: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Telematics Inform 49:101362

Chatzakou D, Kourtellis N, Blackburn J, De Cristofaro E, Stringhini G, Vakali A (2017) Mean birds: Detecting aggression and bullying on twitter. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on web science conference (pp. 13–22)

Chavan VS, Shylaja SS (2015) Machine learning approach for detection of cyber-aggressive comments by peers on social media network. In 2015 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI) (pp. 2354–2358). IEEE

Cheng L, Guo R, Silva YN, Hall D, Liu H (2021) Modeling temporal patterns of cyberbullying detection with hierarchical attention networks. ACM/IMS Trans Data Sci 2(2):1–23

Cheng L, Li J, Silva YN, Hall DL, Liu H (2019) Xbully: Cyberbullying detection within a multi-modal context. In Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (pp. 339–347)

Chen Y, Zhou Y, Zhu S, Xu H (2012) Detecting offensive language in social media to protect adolescent online safety. In 2012 International Conference on Privacy, Security, Risk and Trust and 2012 International Confernece on Social Computing (pp. 71–80). IEEE

Dadvar M, De Jong F (2012) Cyberbullying detection: a step toward a safer internet yard. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on World Wide Web (pp. 121–126)

Dadvar M, Jong FD, Ordelman R, Trieschnigg D (2012) Improved cyberbullying detection using gender information. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Dutch-Belgian Information Retrieval Workshop (DIR 2012) . University of Ghent

Dadvar M, Trieschnigg D, Ordelman R, de Jong F (2013) Improving cyberbullying detection with user context. In European Conference on Information Retrieval (pp. 693–696). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Dey R, Bag S, Sarkar RR (2021) Identification of stable housekeeping genes for normalization of qPCR data in a pathogenic fungus. J Microbiol Methods 180:106106

Google Scholar

Dinakar K, Picard R, Lieberman H (2015) Common sense reasoning for detection, prevention, and mitigation of cyberbullying. In IJCAI International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence .

Dinakar K, Reichart R, Lieberman H (2011) Modeling the detection of textual cyberbullying. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Weblog and Social Media 2011

Divyashree VH, Deepashree NS (2016) An effective approach for cyberbullying detection and avoidance. International Journal of Innovative Research in Computer and Communication Engineering , 14

Djuraskovic O, Cyberbullying Statistics F (2020) and Trends with Charts: First Site Guide; 2020. Available from: https://firstsiteguide.com/cyberbullying-stats/

Elmezain M, Malki A, Gad I, Atlam ES (2022) Hybrid deep learning model–based prediction of images related to Cyberbullying. Int J Appl Math Comput Sci 32(2):323–334

MATH Google Scholar

Fahrnberger G, Nayak D, Martha VS, Ramaswamy S (2014) SafeChat: A tool to shield children’s communication from explicit messages. In 2014 14th International Conference on Innovations for Community Services (I4CS) (pp. 80–86). IEEE

Fang Y, Yang S, Zhao B, Huang C (2021) Cyberbullying detection in social networks using bi-gru with self-attention mechanism. Information 12(4):171

Foong YJ, Oussalah M (2017), September Cyberbullying system detection and analysis. In 2017 European Intelligence and Security Informatics Conference (EISIC) (pp. 40–46). IEEE

Galán-García P, Puerta JGDL, Gómez CL, Santos I, Bringas PG (2016) Supervised machine learning for the detection of troll profiles in twitter social network: application to a real case of cyberbullying. Log J IGPL 24(1):42–53

MathSciNet Google Scholar

García-Recuero Á (2016) Discouraging abusive behavior in privacy-preserving online social networking applications. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference Companion on World Wide Web (pp. 305–309)

Ge S, Cheng L, Liu H (2021) Improving cyberbullying detection with user interaction. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021 (pp. 496–506)

Goodboy AK, Martin MM (2015) The personality profile of a cyberbully: examining the Dark Triad. Comput Hum Behav 49:1–4

Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A (2016) Deep learning. MIT Press

Haidar B, Chamoun M, Serhrouchni A (2017a) Multilingual cyberbullying detection system: Detecting cyberbullying in Arabic content. In 2017 1st Cyber Security in Networking Conference (CSNet) (pp. 1–8). IEEE

Haidar B, Chamoun M, Serhrouchni A (2017b) A multilingual system for cyberbullying detection: arabic content detection using machine learning. Adv Sci Technol Eng Syst J 2(6):275–284

Hani J, Nashaat M, Ahmed M, Emad Z, Amer E, Mohammed A (2019) Social media cyberbullying detection using machine learning. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl 10(5):703–707

Hinduja S, Patchin JW (2010) Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Archives of suicide research 14(3):206–221

Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX (2013) Applied Logistic Regression. Wiley

Hosseinmardi H, Mattson SA, Rafiq RI, Han R, Lv Q, Mishra S (2015b) Detection of cyberbullying incidents on the instagram social network. arXiv preprint arXiv:1503.03909

Hosseinmardi H, Mattson SA, Rafiq RI, Han R, Lv Q, Mishr S (2015a) Prediction of cyberbullying incidents on the instagram social network. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.06257

Hosseinmardi H, Rafiq RI, Han R, Lv Q, Mishra S (2016) Prediction of cyberbullying incidents in a media-based social network. In 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM) (pp. 186–192). IEEE

Huang Q, Singh VK, Atrey PK (2014) Cyber bullying detection using social and textual analysis. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Socially-Aware Multimedia (pp. 3–6)

Hutter F, Kotthoff L, Vanschoren J (2019) Automated machine learning: methods, systems, challenges. Springer

Kaity M, Balakrishnan V (2019) An automatic non-english sentiment lexicon builder using unannotated corpus. J Supercomputing 75(4):2243–2268

Kelleher JD, Tierney B, Tierney B (2018) Data science: an introduction. CRC Press

Kitchenham B, Charters S (2007) Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Tech Rep EBSE 1:1–57

Koutsou A, Tjortjis C (2018) Predicting hospital readmissions using random forests. IEEE J Biomedical Health Inf 22(1):122–130

Kumar A, Nayak S, Chandra N (2019) Empirical analysis of supervised machine learning techniques for Cyberbullying detection. In International Conference on Innovative Computing and Communications (pp. 223–230). Springer, Singapore

Kumar A, Sachdeva N (2020) Multi-input integrative learning using deep neural networks and transfer learning for cyberbullying detection in real-time code-mix data. Multimedia Systems

Kumar A, Sachdeva N (2021) Multimodal cyberbullying detection using capsule network with dynamic routing and deep convolutional neural network. Multimedia Syst, 1–10

LeCun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G (2015) Deep Learn Nat 521(7553):436–444

Li W, Li X (2021) Cyberbullying among college students: the roles of individual, familial, and cultural factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(11):1–17

López-Vizcaíno MF, Nóvoa FJ, Carneiro V, Cacheda F (2021) Early detection of cyberbullying on social media networks. Future Generation Computer Systems 118:219–229

Lu N, Wu G, Zhang Z, Zheng Y, Ren Y, Choo KKR (2020) Cyberbullying detection in social media text based on character-level convolutional neural network with shortcuts. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience, e5627

Maity K, Sen T, Saha S, Bhattacharyya P (2022) MTBullyGNN: a graph neural network-based Multitask Framework for Cyberbullying Detection. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems

Malik CI, Radwan RB (2020) Adolescent victims of cyberbullying in Bangladesh- prevalence and relationship with psychiatric disorders. Asian J Psychiatr 48:101893

Mangaonkar A, Hayrapetian A, Raje R (2015) Collaborative detection of cyberbullying behavior in Twitter data. In 2015 IEEE international conference on electro/information technology (EIT) (pp. 611–616). IEEE

Manning CD, Raghavan P, Schütze H (2008) Introduction to Information Retrieval. Cambridge University Press

McEvoy MP, Williams MT (2021) Quality Assessment of systematic reviews and Meta-analyses of physical therapy interventions: a systematic review. Phys Ther 101(4):pzaa226

Mercado RNM, Chuctaya HFC, Gutierrez EGC (2018) Automatic cyberbullying detection in spanish-language social networks using sentiment analysis techniques. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl 9(7):228–235

Monteiro RP, Santana MC, Santos RM, Pereira FC (2022) Cyberbullying victimization and mental health in higher education students: the mediating role of perceived social support. J interpers Violence, 1–23

Nahar V, Al-Maskari S, Li X, Pang C (2014) Semi-supervised learning for cyberbullying detection in social networks. In Australasian Database Conference (pp. 160–171). Springer, Cham

Nahar V, Unankard S, Li X, Pang C (2012) Sentiment analysis for effective detection of cyber bullying. Asia-Pacific Web Conference

Nandhini BS, Sheeba JI (2015) Online social network bullying detection using intelligence techniques. Procedia Comput Sci 45:485–492

Niu M, Yu L, Tian S, Wang X, Zhang Q (2020) Personal-bullying detection based on Multi-Attention and Cognitive Feature. Autom Control Comput Sci 54(1):52–61

Noviantho, Isa SM, Ashianti L (2018) Cyberbullying classification using text mining. In Proceedings - 2017 1st International Conference on Informatics and Computational Sciences , ICICoS 2017

Patil C, Salmalge S, Nartam P (2020) Cyberbullying detection on multiple SMPs using modular neural network. Advances in Cybernetics, Cognition, and machine learning for Communication Technologies. Springer, Singapore, pp 181–188

Chapter Google Scholar

Pawar R, Raje RR (2019) Multilingual Cyberbullying Detection System. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (EIT) (pp. 040–044). IEEE

Pires TM, Nunes IL (2019) Support vector machine for human activity recognition: a comprehensive review. Artif Intell Rev 52(3):1925–1962

Pradhan A, Yatam VM, Bera P (2020) Self-Attention for Cyberbullying Detection. In 2020 International Conference on Cyber Situational Awareness, Data Analytics and Assessment (CyberSA) (pp. 1–6). IEEE

Pérez PJC, Valdez CJL, Ortiz MDGC, Barrera JPS, Pérez PF (2012) MISAAC: Instant messaging tool for cyberbullying detection. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence , ICAI 2012 (pp. 1049–1052)

Rafiq RI, Hosseinmardi H, Han R, Lv Q, Mishra S (2018) Scalable and timely detection of cyberbullying in online social networks. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Symposium on Applied Computing (pp. 1738–1747)

Raisi E, Huang B (2018) Weakly supervised cyberbullying detection with participant-vocabulary consistency. Social Netw Anal Min 8(1):38

Reynolds K, Kontostathis A, Edwards L (2011) Using machine learning to detect cyberbullying. In 2011 10th International Conference on Machine learning and applications and workshops (Vol. 2, pp. 241–244). IEEE

Rosa H, Matos D, Ribeiro R, Coheur L, Carvalho JP (2018) A “deeper” look at detecting cyberbullying in social networks. In 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) (pp. 1–8). IEEE

Rosa H, Pereira N, Ribeiro R, Ferreira PC, Carvalho JP, Oliveira S, Coheur L, Paulino P, Veiga Simão AM, Trancoso I (2019) Automatic cyberbullying detection: A systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior, 93, 333–345

Salawu S, He Y, Lumsden J (2017) Approaches to automated detection of cyberbullying: a survey. IEEE Trans Affect Comput.

Sanchez H, Kumar S (2011) Twitter bullying detection. ser. NSDI , 12 (2011), 15

Shah N, Maqbool A, Abbasi AF (2021) Predictive modeling for cyberbullying detection in social media. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput 12(6):5579–5594

Singh A, Kaur, M (2020) Intelligent content-based cybercrime detection in online social networks using cuckoo search metaheuristic approach [Article]. J Supercomput 76(7):5402–5424

Singh VK, Ghosh S, Jose C (2017) Toward multimodal cyberbullying detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2090–2099)

Soni D, Singh VK (2018) See no evil, hear no evil: Audio-visual-textual cyberbullying detection. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction , 2 (CSCW), 1–26

Squicciarini A, Rajtmajer S, Liu Y, Griffin C (2015) Identification and characterization of cyberbullying dynamics in an online social network. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining 2015 (pp. 280–285)

Sugandhi R, Pande A, Agrawal A, Bhagat H (2016) Automatic monitoring and prevention of cyberbullying. Int J Comput Appl 8:17–19

Tahmasbi N, Rastegari E (2018) A socio-contextual approach in automated detection of public cyberbullying on Twitter. ACM Trans Social Comput 1(4):1–22

Tan SH, Zou W, Zhang J, Zhou Y (2020) Evaluation of machine learning algorithms for prediction of ground-level PM2.5 concentration using satellite-derived aerosol optical depth over China. Environ Sci Pollut Res 27(29):36155–36170

Tarwani S, Jethanandani M, Kant V (2019) Cyberbullying Detection in Hindi-English Code-Mixed Language Using Sentiment Classification. In International Conference on Advances in Computing and Data Sciences (pp. 543–551). Springer, Singapore

Tomkins S, Getoor L, Chen Y, Zhang Y (2018) A socio-linguistic model for cyberbullying detection. In 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM) (pp. 53–60). IEEE

van Geel M, Goemans A, Toprak F, Vedder P (2017) Which personality traits are related to traditional bullying and cyberbullying? A study with the big five, Dark Triad and sadism. Pers Indiv Differ 106:231–235

Van Hee C, Jacobs G, Emmery C, Desmet B, Lefever E, Verhoeven B, …, Hoste V (2018) Automatic detection of cyberbullying in social media text. PLoS ONE, 13(10), e0203794

Van Hee C, Lefever E, Verhoeven B, Mennes J, Desmet B, De Pauw G, …, Hoste V (2015) Detection and fine-grained classification of cyberbullying events. In International Conference Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing (RANLP) (pp. 672–680)

Wang W, Xie X, Wang X, Lei L, Hu Q, Jiang S (2019) Cyberbullying and depression among chinese college students: a moderated mediation model of social anxiety and neuroticism. J Affect Disord 256:54–61

Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JP et al (2016) ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol 69:225–234

Witten IH, Frank E, Hall MA (2016) Data Mining: practical machine learning tools and techniques, 4th edn. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers

Wright MF (2017) Cyberbullying in cultural context. J Cross-Cult Psychol 48(8):1136–1137

Wu J, Wen M, Lu R, Li B, Li J (2020) Toward efficient and effective bullying detection in online social network. Peer-to-Peer Netw Appl, 1–10

Wu T, Wen S, Xiang Y, Zhou W (2018) Twitter spam detection: survey of new approaches and comparative study. Computers & Security 76:265–284

Yin D, Xue Z, Hong L, Davison BD, Kontostathis A, Edwards L (2009) Detection of harassment on web 2.0. Proceedings of the Content Analysis in the WEB , 2 , 1–7

Zhang X, Tong J, Vishwamitra N, Whittaker E, Mazer JP, Kowalski R, Hu H, Luo F, Macbeth J, Dillon E (2017) Cyberbullying detection with a pronunciation based convolutional neural network. In Proceedings - 2016 15th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications, ICMLA 2016

Zhao R, Mao K (2017) Cyberbullying detection based on semantic-enhanced marginalized denoising auto-encoder. IEEE Trans Affect Comput 8(3), 328–339. Article 7412690

Zhao R, Zhou A, Mao K (2016) Automatic detection of cyberbullying on social networks based on bullying features. In Proceedings of the 17th international conference on distributed computing and networking (pp. 1–6)

Zhong H, Li H, Squicciarini AC, Rajtmajer SM, Griffin C, Miller DJ, Caragea C (2016) Content-Driven Detection of Cyberbullying on the Instagram Social Network. In IJCAI (pp. 3952–3958)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Computer Science and Information Systems, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

Vimala Balakrisnan & Mohammed Kaity

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

VB wrote the original draft; performed analysis; revised the article; MK performed data collection; performed analysis; revised the article; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vimala Balakrisnan .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Balakrisnan, V., Kaity, M. Cyberbullying detection and machine learning: a systematic literature review. Artif Intell Rev 56 (Suppl 1), 1375–1416 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-023-10553-w

Download citation

Accepted : 08 July 2023

Published : 24 July 2023

Issue Date : October 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-023-10553-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cyberbullying

- Machine learning

- Systematic literature review

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- 315 Montgomery Street, 10 th Floor, Suite #900, San Francisco, CA 94104, USA

- [email protected]

- +1-628-201-9788

- NLM Catalog

- Crossmark Policy

For Authors

- Author Guidelines

- Plagiarism policy

- Peer review Process

- Manuscript Guidelines

- Online submission system

- Processing Fee

For Editors

- Editor Guidelines

- Associate Editor Guidelines

- Reviewer Guidelines

To Register as

- Associate Editor

- Submit Manuscript

NLM Catalog Journals

- Archives in biomedical engineering & biotechnology

- Online journal of complementary & alternative medicine

- Archives in Neurology & Neuroscience

- Global Journal of Pediatrics & Neonatal Care

- World Journal of Gynecology & Womens Health

- Anaesthesia & Surgery Open Access Journal

- Global Journal of Orthopedics Research

- Annals of urology & nephrology

Open Access Journal of Addiction and Psychology - OAJAP

- ISSN: 2641-6271

Managing Editor: Nikki Fenn

Contact us at:

Mini Review

Effects of cyber bullying on teenagers: a short review of literature.

Mir Ali Raza Talpur 1 , Tabinda Touseef 2 , Syed Daniyal Ahmed Jilanee 1 , Muhammad Mubashir Shabu 3 and Ali Khan 4 *

1 Liaquat National Medical College and Hospital, Pakistan

2 Jinnah Medical and Dental College, Pakistan

3 Karachi Medical and Dental College, Pakistan

4 Dow University of Health and Sciences, Pakistan

Corresponding Author

Ali Khan, 4Dow University of Health and Sciences, Karachi, Pakistan.

Received Date: November 07, 2018; Published Date: November 26, 2018

Among the numerous advantages of the internet, there is an unintended outcome of the internet’s extensive reach: the growing rate of harmful offences against children and teens. Cyber-bullying victimization has recently received a fair amount of attention due to some heart-breaking events orbiting in schools and even at homes. Although research has already demonstrated a number of serious consequences of cyber-victimization, many questions remain unanswered concerning the impact of cyber-bullying. This study gathers literature from 18 studies pieces together only the factors that kick-start cyber-bullying perpetration and victimization but also the effects of bullying on the victims as well as the bullies.

Keywords: Cyber-bully; Teenagers; Effects; Perpetrators; Victims

- Introduction

Cyber-bullying interactions are usually defined as “repeated, harmful interactions which are deliberately offensive, humiliating, threatening, and power assertive, and are enacted using electronic equipment, such as cell (mobile) phones or the Internet, by one or more individuals towards another” [1]. It might be a continuation of real life bullying but can also exist on its own [2].

Smith et al divided cyber-bullying in seven sub-categories, namely: text message bullying, picture/ video clip bullying, phone call bullying, email bullying, chat-room bullying, bullying through instant messaging (18%) and bullying via websites among which picture/video clip and phone call were perceived to have the most impact [3]. Even though chat room, instant messaging and email bullying were perceived to have the least impact on the victim another study deems it most common among all (18% and 13.8%, respectively) [4].

- Review of Literature

Literature search strategy

A thorough search of medical literature was conducted on Pubmed, Google scholar and Scopus databases. The key MeSH and non-MeSH terms were “Cyber-bully”, “teenagers”, “Effects”, “Perpetrators” and “Victims”. Literature search was confined to English language literature only. Medical literature from the past two decades was included in this research. Studies reporting the outcomes of cyber-bullying in healthy teenagers (13-19 years of age) were included whereas studies reporting psychological outcome in relation to other pathologies, victims primarily being older than 19 years of age and outcomes in mentally disabled subjects were excluded from the study.

Nature of harassment

The nature of harassment ranges from ignoring, disrespecting, threatening, calling names, spreading rumors, email bombing, picking on and ridiculing [4] to hiding names while sending SMS or when in a chat room, kicking someone out of a chat room, and violating the privacy of someone by a webcam [5].

Comparison with traditional bullying

Electronic communications allows perpetrators to maintain anonymity, access to a wide audience and 24/7 attainability. In addition, private nature of the communication devoid of non-verbal quos makes cyber-bullying different from traditional bullying. Perpetrators may feel reduced responsibility and accountability leaving victims more vulnerable [6-8].

Causes of cyberbullying perpetration

According to studies there was no correlation between age and cyber-bullying (p=0.39) [1]. Males were more likely to cyber-bully others than females (p=0.021) [9]. Only 43.6% of cyber-bullies thought that their bullying behavior was harsh to very harsh on the victims (Cyber victims: 66.4%), similarly, only 26% thought their actions had an impact on their victim’s life (Cyber victims: 34.6%). Those who bullied others scored higher on the peer relationship problems scale (p=0.001) [1]. Cyber-bully statuses were independently predicted by conduct (OR = 2.6; 95% CI, 1.5-4.5; P < .001) and hyperactivity problems (OR = 2.4; 95% CI, 1.4-3.9; P< .001) and pro-social problems (OR = 2.3; 95% CI, 1.5-3.4; P< .001). No significant difference was observed between children of two biological parents and children living in a family with other than two biological parents [4]. Traditional bullies tended to be cyberbullies as well (p < 0.001). Within a group of school bullies, 85.5% reported that they were also victims and even though almost 30% in this group were cyber-bullies, 27.3% were cyberbully victims [10].

Anonymity associated with electronic communication tools promotes cyberbullying and makes it difficult to prevent [7,10]. The frequencies of public school students who indicated being cyberbullies were higher than those of the private school students [5].

Although the frequent use of communication tools significantly promoted cyber-bullying in female students (p = 0.001), male students did not have the same effect (p =0.431). On the other hand, the role of risky internet use in promoting cyber-bullying was not significant for female students (p=0.721), it was significant for male students (p = 0.001) [11].

Causes of cyberbullying victimization

Age: Although a decrease is seen in exclusive school bullying from ages 14 (16.6%) to 18 (7.1%), cyber-bullying actually increases between the ages 14 (6.2%) to 18 (7.4%) [10].

Gender: Although some studies show no significant difference between the proportion of male and female adolescents who reported being bullied (p=0.91) [9]. There are reports indicating higher occurrence of cyber-bullying among females than males (18.3% vs 13.2%) [12,13].

Race/Ethnicity: Whites/Caucasians were more prone to be victimization [14].

Physical appearance: Females seen as less or more attractive than others were at the highest risk for harassment while some students were also targeted on the basis of disability [9].

Traditional bullying victim: Traditional bully victims were also likely to be cyber-victims (p = 0.022) [15].

Family composition: Cyber-victim only status was associated with living in a family with other than 2 biological parents (6.2% vs 4%) [4].

exual orientation: Youngsters who identified themselves as heterosexual were less likely to be victimized as compared to their non-heterosexual counterparts (6% vs 10.5%) [12].

School performance: Students who performed poorly in school (D & F grade holders) were more than twice as likely to be victims of either traditional or online harassment, or both, as compared to students who received A-grades (16.1% vs 7.4%) [12].

Technology use: The risky internet use and usage frequency predicted cyber-bullying victimization significantly when compared with traditional victimization among female (ΔR2 = .133, F (2, 83) = 6.78, p = .002) as well as male students (ΔR2 = .216, F (2, 108) = 15.98, p = .000). (11) In another study, Eric Rice reported high levels of texting (OR = 2.1; 95% CI = 1.1, 4.0; P < .05) and Internet use (OR = 2.0; 95% CI = 1.0, 3.64; P < .05) were associated with being a cyber-victim [14].

Type of school: Public school students reported experiencing cyber harassment more frequently than those studying in the private school [5].

Effects of cyberbullying on the perpetrator

The association between cyberbully perpetrator and their mental health and well-being is equally important to take under consideration. Many studies reported that cyberbullyng does not only has negative effects on the its victims but also on the perpetrator as well It was observed that 39% of students who harassed others online dropped out of school and 37% showed delinquent behavior [1]. About 32% of online harassers were frequent substance abusers, while some reported frequent smoking and drunkenness. A study reported that about 16% perpetrators were severely depressed [1] while in another study there reports of bullies feeling unsafe in school [4]. This study also states a strong correlation between psychiatric, psychosocial and psychosomatic disorders with being a cyberbully or a cybervictim [4]. With the rise of cyberbullying there arise a hypothesis that students who cyberbully may feel greatly powerful by taking the advantage of immense anonymity and by targeting much bigger and wider audience [16]. It has also been speculated that the lack of immediate retaliation by the victim may provoke perpetrator towards harsher bullying [17]. A study ny Gini et al has shown that bullies are morally capable enough to judge actions but still have potential deficiencies with respect to moral sentiments and appear to have high levels of moral disengagement which is why they lack empathy for victim [18].

Effects on cybervictims

In relation to combating cyber-bullying males responded more actively and with physically retaliatory behavior, whereas females’ responses indicated more passive and verbally retaliatory behavior [15]. About 1 in every 4 individuals reported fear for their safety most of whom most reported getting targeted by an adult. Sourander et al reported association between victimization and sleeping problems (p < 0.001), bed-wetting, headaches (p < 0.001), recurrent abdominal pain and stomachaches. The same study states that victims experience numerous perceived problems, social anxiety, emotional disturbances and peer problems [4]. Hoff et al in their study found that students who were the targets of cyber bully reported several negative psychological effects. They experienced high levels of aggressiveness, powerlessness, sadness, and fear [15]. Girls who were victimized by cyberbully were significantly (P=0.003) more likely to reports 2-week sadness (36% vs. 21%), suicidal ideation (19% vs. 12%), suicide plan (15% vs. 11%), attempt (10% vs. 6%), and treatment for attempt (3% vs. 2%) as compared to victimized boys. This study also shows a strong association of suicidality in teens with victimization of bully, especially cyberbully [19].

Students categorized as “other” race (20%) and Hispanics (14%) presented with higher suicide ideation, as well as were more likely to report having made a suicide attempt (10% and 11%, respectively) compared to Caucasians (6%) and African-Americans (8%) [19]. The analysis showed that female cybervictims were more likely to inform adults than males (p = 0.012) and among students who knew someone being cyber bullied, only 30.1% told adults with no correlation to gender [9]. Non-heterosexual groups were far more likely to report bullying (33.1% vs 14.5%) [12].

Both public and private school students revealed seeking help from their friends (28.6% vs 43.6%) however only a few of the public school students stated that they had asked for help from their teachers while none of the private school students reported asking help from them [5]. A study by ML Ybarra et al states that the victims of cyberbully undergoes variety of social problems which results in having them caught in detentions, suspensions and school avoiding behavior [20]. The same study shows that cyberbully victims experience paranoia due to which they tend to carry weapons with them [20]. The cyberbully victims are more likely to develop aggression against bullies and tend to become cyber bullies to take revenge and may experience the same negative impacts as being experienced by a perpetrator [20].

Interventions

Educating children: Warning from the dangers that lurk in cyber space and training of children must start at a young age, involving them in discussions about the dangers of bullying and how to by an ally when they see cyber-bullying behavior and who to report to? [15]

Educating teachers: Educators should become “safe contacts,” giving students a place to turn if they are victims or want to report perpetrators [15].

Educating parents: Monitoring their child’s online behavior, implementing internet usage rules and what to do if they discover that their child is a participant or a target is part of parent education in combating cyber-bullying [15]. The percentage of youth reporting the existence of parental rules on Web sites (p < 0.01), time allowed online (p < 0.01), and filter restricting online activities (p < 0.05) is higher among non-victims than among victims [13].

Role of school: Another role of schools is to help students cope with social tension especially those that center on relationship issues, assess of students in order to determine bullying behavior and get to the root of it [15].

Technological coping strategies: Instituting strict privacy settings on Internet-based technologies such as instant messengers and e-mails, changing usernames and or e-mail addresses [21].

Cyber-bullying is a multi-conceptual topic which requires immense research. After a thorough search of literature, we’ve concluded that cyber-bullying is one of the worst forms of bully which imparts its devastating effects on teenagers. Perpetrators of cyber-bully misuse the cyber resources in various ways to bully people online for the sake of their psychological satisfaction which badly influence the targeted victims as well as the active perpetrator.

A targeted victim, as a consequence of cyber-bully, may experience insecurities, poor school performance, addictions, psychosomatic disorders, retaliatory behavior, emotional distress, suicidal tendencies etc. This altogether adds to destruction of normal psychology of a teenager. Cyber-bullying also impacts the perpetrators with serious psychosomatic, psychiatric and psychosocial disorders. All the individuals involved in cyber-bully, either as a victim or a perpetrator, face some serious outcomes of this problem which can only be reduced by active measures to combat it.

- Acknowledgment

- Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Campbell MA, Slee PT, Spears B, Butler D, Kift S (2013) Do cyberbullies suffer too? Cyberbullies’ perceptions of the harm they cause to others and to their own mental health. School Psychology International 34(6): 613-629.

- Brandtzaeg PB, Staksrud E, Hagen I, Wold T (2009) Norwegian children’s experiences of cyberbullying when using different technological platforms. Journal of Children and Media. 3(4): 349-365.

- Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Tippett N (2006) An investigation into cyberbullying, its forms, awareness and impact, and the relationship between age and gender in cyberbullying.

- Sourander A, Klomek AB, Ikonen M, Lindroos J, Luntamo T, et al. (2010) Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: A population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 67(7): 720- 728.

- Topçu C, Erdur-Baker O, Capa-Aydin Y (2008) Examination of cyberbullying experiences among Turkish students from different school types. Cyberpsychol Behav 11(6): 643-648.

- Huang Y-y, Chou C (2010) An analysis of multiple factors of cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Computers in Human Behavior. 26(6): 1581-1590.

- Dehue F, Bolman C, Völlink T (2008) Cyberbullying: Youngsters’ experiences and parental perception. Cyberpsychol Behav 11(2): 217- 223.

- Heirman W, Walrave M (2008) Assessing concerns and issues about the mediation of technology in cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 2(2).

- Li Q (2006) Cyberbullying in schools: A research of gender differences. School Psychology International 27(2): 157-170.

- Li Q (2007) New bottle but old wine: A research of cyberbullying in schools. Computers in Human Behavior 23(4): 1777-1791.

- Erdur-Baker Ozgur (2010) Cyberbullying and its correlation to traditional bullying, gender and frequent and risky usage of internetmediated communication tools. New media & society 12(1): 109-125.

- Schneider SK, O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Coulter RW (2012) Cyberbullying, school bullying, and psychological distress: A regional census of high school students. Am J Public Health 102(1): 171-177.

- Mesch GS (2009) Parental mediation, online activities, and cyberbullying. Cyberpsychol Behav 12(4): 387-393.

- Rice E, Petering R, Rhoades H, Winetrobe H, Goldbach J, et al. (2015) Cyberbullying perpetration and victimization among middle-school students. Am J Public Health. 105(3): e66-e72.

- Hoff DL, Mitchell SN (2009) Cyberbullying: Causes, effects, and remedies. Journal of Educational Administration. 47(5): 652-665.

- Steffgen G, König A, Pfetsch J, Melzer A (2011) Are cyberbullies less empathic? Adolescents’ cyberbullying behavior and empathic responsiveness. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 14(11): 643-648.

- Conn K (2004) Bullying and harassment: A legal guide for educators: ASCD.

- Gini G, Pozzoli T, Hauser M (2011) Bullies have enhanced moral competence to judge relative to victims, but lack moral compassion. Personality and Individual Differences 50(5): 603-608.

- Messias E, Kindrick K, Castro J (2014) School bullying, cyberbullying, or both: correlates of teen suicidality in the 2011 CDC Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Compr Psychiatry 55(5): 1063-1068.

- Ybarra ML, Diener-West M, Leaf PJ (2007) Examining the overlap in Internet harassment and school bullying: Implications for school intervention. J Adolesc Health 41(6 Suppl 1): S42-S50.

- Tokunaga RS (2010) Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior 26(3): 277-287.

- Download PDF

- DOI: 10.33552/OAJAP.2018.01.000511

- Volume 1 - Issue 3, 2018

- Open Access

Mir Ali Raza Talpur, Tabinda Touseef, Syed Daniyal Ahmed Jilanee, Muhammad Mubashir Shabu, Ali Khan. Effects of Cyber Bullying on Teenagers: a Short Review of Literature. Open Access J Addict & Psychol. 1(3): 2018. OAJAP.MS.ID.000511.

Disability, Physical disability, Disease Control, Prevention, Quality of life, Optimism, Nigerian, Diabetes, Comorbidity, Behaviour, Optimistic, Neurological, Cognitive, Mental capacity, Cyber-bullying, Internet Addiction, Hacking, Phone, Cybervictim

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License .

Track Your Article

Refer a friend, suggested by, referrer details, advertise with us.

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Bullying in a networked era: Research views on scope and frequency of cyberbullying

2012 and 2013 reports from Harvard's Berkman Center for Internet & Society and the University of New Hampshire examine and consolidate the research findings of recent studies.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Cynthia Thaler, The Journalist's Resource September 19, 2013

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/education/bullying-networked-era-literature-review/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

The suicide of Rutgers University student Tyler Clementi in September 2010 brought increased national attention to the issues of cyber-bullying and bias-based bullying . A number of states and localities have subsequently sought to develop legislation to address what is seen as a growing problem. But societal problems with bullying, of course, continue, and new reports seem to emerge in the media on a weekly basis. For example, in September 2013 a 12-year-old Florida girl, Rebecca Ann Sedwick, is alleged to have committed suicide because of persistent harassment in social media, according to law enforcement officials . The world of mobile apps has made this problem only more complicated, as the New York Times has reported .

Although such reports can seem terrifying in their particulars — and feed into a pervasive sense that the Internet is a threatening place for youth — it is useful to keep in mind the more general research findings about the true scope, scale and frequency of this problem, and the Web’s precise role in enabling it.

A 2013 study sheds more light on aspects of this phenomenon. In “Cyber Bullying and Physical Bullying in Adolescent Suicide: The Role of Violent Behavior and Substance Use,” published in the Journal of Youth and Adolescence , researchers Brett J. Litwiller of the University of Oklahoma and Amy M. Brausch of Western Kentucky University examine a sample of nearly 4,700 high school students. It is one of the first studies to examine empirically why there is a connection between bullying and suicide, among other negative behaviors. The findings suggest that “both types of bullying, cyber and physical, positively predicted suicidal behavior, substance use, violent behavior, and unsafe sexual behavior.” In terms of their findings specifically for online behavior, Litwiller and Brausch note:

Cyber bullying had a similar sized effect on suicidal behavior, substance use, violent behavior, and unsafe sexual behavior as physical bullying. This finding provides further evidence of the potential consequences of cyber bullying. In contrast to physical bullying, cyber bullying has been found to be more difficult to avoid, anonymous, and likely to coincide with other forms of bullying…. Although not specifically examined in this study, victims of cyber bullying may more be likely to experience negative psychological states, thus contributing to feelings of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. If cyber bullying activates feeling like one does not belong or is a burden to others, an adolescent’s risk of suicidal behavior may increase, especially if adolescents are also engaging in risk behaviors that may habituate them to pain and fear of death.

Another 2013 study, “Characteristics of College Cyberbullies,” published in Computers in Human Behavior , provides more empirical evidence about the phenomenon among slightly older young persons. The authors, Allison M. Schenk, William J. Fremouw and Colleen M. Keelan of West Virginia University, examined the personality traits of 60 persons who self-reported having participated at least four times in cyberbullying someone else (these profiles were drawn from a survey of more than 800 students.) There were 36 females and 24 males among the cyberbullies. The survey also recorded the experiences of 19 victims. The authors conclude:

Cyberbullies and cyberbully/victims scored higher than control participants on general distress, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoia, and psychotic symptoms. Although it is not known how these symptoms directly relate to cyberbullying, these significant differences indicate a disparity in psychological functioning between those individuals involved in cyberbullying their uninvolved peers. This elevated level of psychological impairment for cyberbullies and cyberbully/victims was also reflected in an increase of suicidal thoughts and tendencies overall than control participants. Cyberbully/victims also were more likely than pure cyberbullies and controls to have told someone they were thinking about committing suicide.

A 2012 report from Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society, “Bullying in a Networked Era: A Literature Review,” examines and consolidates the findings of other studies published between 2008 and 2012. The data focus on American youth in middle and high school. The authors — Nathaniel Levy, Sandra Cortesi, Urs Gasser, Edward Crowley, Meredith Beaton, June Casey and Caroline Nolan — define bullying as having three primary characteristics: It is intentional, involves a power imbalance between aggressor(s) and victim, and is repetitive.

The report highlights the following findings:

- “Youth play a variety of roles in the bullying dynamic. Bullying involvement can be characterized by four basic roles: (a) bully, (b) victim, (c) bully-victim (actors who both bully and are victimized by others) and (d) bystander. The role of the bully-victim shows that those of bullies and victims are not always clear-cut. Certain types of bullying, such as ‘relational’ aggression (both online and offline), are more likely to involve bully-victims. Certain types of youth are more likely to be victimized, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender ( LGBT ) youth and youth with disabilities.”

- “In one national study of 2,400 6-17 year olds, between 34-42% of youths were bullied frequently in the past year…. Based on nationally representative 2001 data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health, which surveyed 15,686 students in the 6th to 10th grades, roughly 33% of students were involved in bullying as victims, bullies or both…. Based on 2005-2006 data from the School Survey on Crime and Safety, the U.S. Department of Education found that nearly 25% of public schools principals reported bullying to be a daily or weekly occurrence.”

- “The anonymity of the bully is not as prevalent online as some research has suggested. One anonymous survey of over 1,400 teens ages 12-17 showed that 73% of participants who were victims of cyberbullying knew the identity of their bully (within this group, 43% from the Internet and 71% from offline — please note that participants were allowed to indicate multiple answers to the survey questions)…. A nationally representative study of over 1,000 teens ages 12-17 notes a lower percentage — 54% of online victims who participated knew their bully’s identity.”

- “Youth bullied offline for their sexual orientation or gender identity face a greater likelihood of more severe consequences than other victims. Although fewer studies have compared bias based bullying or harassment of multiple varieties, initial comparisons suggest that experiencing any kind of bias-based victimization can have a greater negative impact than other forms of bullying.” This includes substance abuse, psychological distress, negative views of their school environment, missing school and having lower grades.

- “A national survey of 5,621 youth ages 12-18 found that 64% of all respondents who experienced offline bullying in various forms did not report it to teachers or school officials.”

- “School policies can guide prevention and intervention efforts by establishing a framework for action and communicating this framework, and the school’s commitment to it, to the broader community…. ‘Zero tolerance’ and other highly punitive disciplinary approaches have been shown not to work; a balance of consistent disciplinary action and support for students has been more effective.”

- “A recent study of over 7,300 students in the 9th grade and 2,900 teachers randomly selected from 290 high schools found that students who seek help for being bullied are less likely to be bullied again.”

- One study shows that “teachers were also more likely to respond to an incident — either when informed of or observing one — when they felt prepared to respond, indicating a role for training programs to provide such preparation.”

- “As of January 2012, 10 states required (and one encouraged) schools or school districts to provide school staff with professional development or training to better understand the relevant school district’s bullying policy, many of which cover reporting and response processes. 16 states required and six encouraged that schools or school districts provide staff with professional development or training in bullying prevention.”

- “The climate, or culture, of a school can have an impact on the prevalence of bullying and students’ comfort levels — and likelihood — of reporting acts of bullying to adults in school. Students’ feelings of being connected to and supported by school are prime characteristics of positive school climate, which are associated with lower levels of bullying. Positive relationships with peers and adults within school, and a sense of being treated fairly by teachers, are in turn important aspects of a connected and supportive school climate.”

The authors conclude by noting that online activity can also “produce positive experiences, including exposure to diverse perspectives, which is helpful for positive social and intellectual growth.” They recommend that “when cultivating a school, home, or community environment, educators, parents, and other adults can learn of ways to leverage or encourage the development of youths’ positive social interactions online.”

A 2013 report from the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire, “Trends in Bullying and Peer Victimization,” finds that bullying rates have declined markedly since the early 1990s. But the author cautions that bullying is still a major problem among American youth: “[These findings should] not be interpreted as the problem having been solved. First, the rates are still incredibly high. For example, more than one in 10 high school students said they were in a physical fight on school property in the last year. We would not tolerate a level of work place danger that was so high, nor should we.”

Tags: youth, safety, technology, bullying

About The Author

Cynthia Thaler

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Child Adolesc Trauma

- v.11(1); 2018 Mar

Cyberbullying and LGBTQ Youth: A Systematic Literature Review and Recommendations for Prevention and Intervention

Roberto l. abreu.

1 Department of Educational, School, and Counseling Psychology, College of Education, University of Kentucky, 251 Dickey Hall, Lexington, KY 40506 USA

Maureen C. Kenny

2 Leadership and Professional Studies, College of Arts, Science and Education, Florida International University, Miami, FL USA

Research has demonstrated that cyberbullying has adverse physical and mental health consequences for youths. Unfortunately, most studies have focused on heterosexual and cisgender individuals. The scant available research on sexual minority and gender expansive youth (i.e., LGBTQ) shows that this group is at a higher risk for cyberbullying when compared to their heterosexual counterparts. However, to date no literature review has comprehensively explored the effects of cyberbullying on LGBTQ youth. A systematic review resulted in 27 empirical studies that explore the effects of cyberbullying on LGBTQ youth. Findings revealed that the percentage of cyberbullying among LGBTQ youth ranges between 10.5% and 71.3% across studies. Common negative effects of cyberbullying of LGBTQ youth include psychological and emotional (suicidal ideation and attempt, depression, lower self-esteem), behavioral (physical aggression, body image, isolation), and academic performance (lower GPAs). Recommendations and interventions for students, schools, and parents are discussed.