9 Creative Case Study Presentation Examples & Templates

Learn from proven case study presentation examples and best practices how to get creative, stand out, engage your audience, excite action, and drive results.

9 minute read

helped business professionals at:

Short answer

What makes a good case study presentation?

A good case study presentation has an engaging story, a clear structure, real data, visual aids, client testimonials, and a strong call to action. It informs and inspires, making the audience believe they can achieve similar results.

Dull case studies can cost you clients.

A boring case study presentation doesn't just risk putting your audience to sleep—it can actually stifle your growth, leading to lost sales and overlooked opportunities. When your case study fails to inspire, it's your bottom line that suffers.

Interactive elements are the secret sauce for successful case study presentations.

They not only increase reader engagement by 22% but also lead to a whopping 41% more decks being read fully, proving that the winning deck is not a monologue but a conversation that involves the reader.

Benefits of including interactive elements in your case study presentation

More decks read in full

Longer average reading time

In this post, I’ll help you shape your case studies into compelling narratives that hook your audience, make your successes shine, and drive the results you're aiming for.

Let’s go!

How to create a case study presentation that drives results?

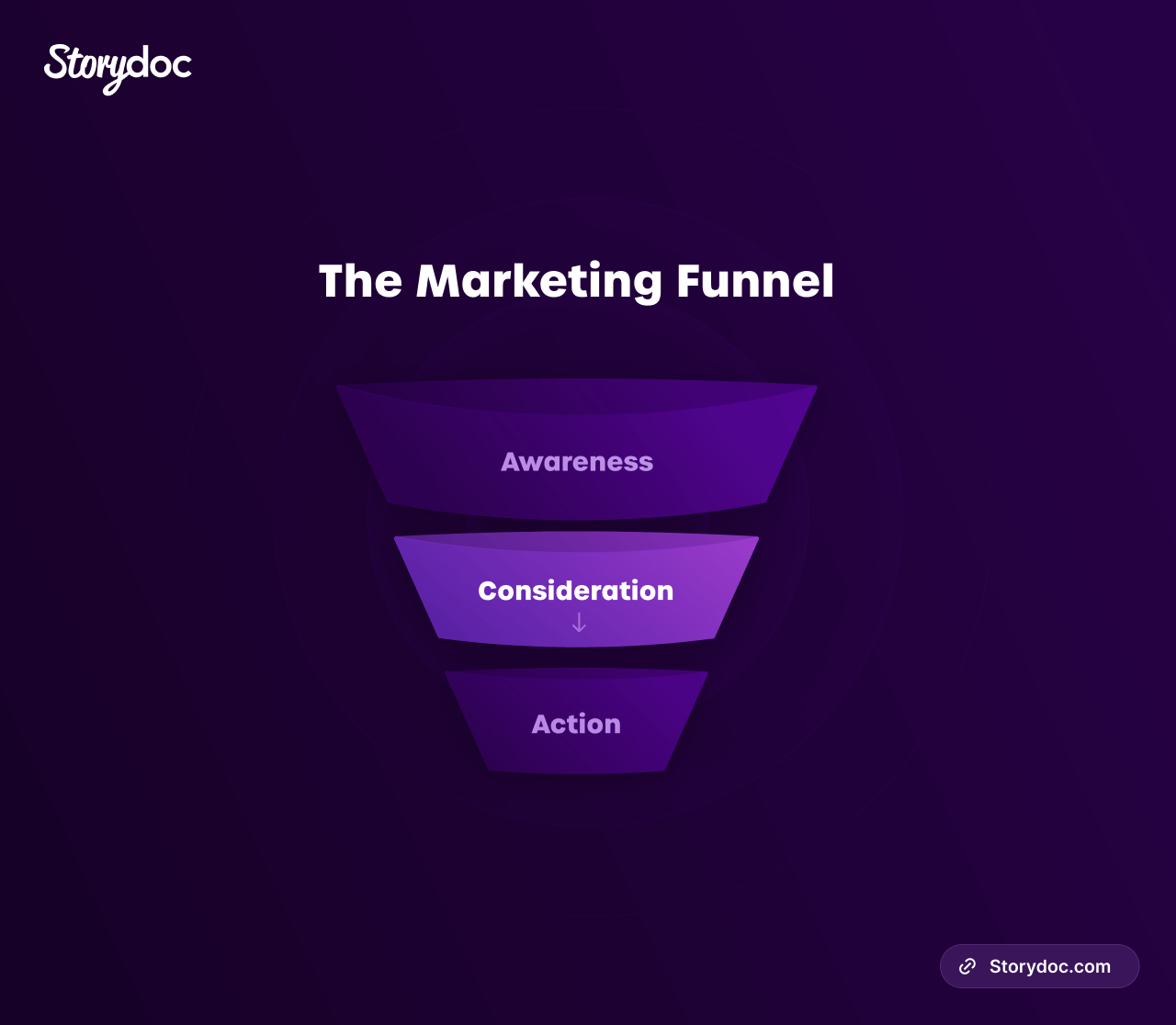

Crafting a case study presentation that truly drives results is about more than just data—it's about storytelling, engagement, and leading your audience down the sales funnel.

Here's how you can do it:

Tell a story: Each case study should follow a narrative arc. Start with the problem, introduce your solution, and showcase the results. Make it compelling and relatable.

Leverage data: Hard numbers build credibility. Use them to highlight your successes and reinforce your points.

Use visuals: Images, infographics, and videos can enhance engagement, making complex information more digestible and memorable.

Add interactive elements: Make your presentation a two-way journey. Tools like tabs and live data calculators can increase time spent on your deck by 22% and the number of full reads by 41% .

Finish with a strong call-to-action: Every good story needs a conclusion. Encourage your audience to take the next step in their buyer journey with a clear, persuasive call-to-action.

Here's a visual representation of what a successful case study presentation should do:

How to write an engaging case study presentation?

Creating an engaging case study presentation involves strategic storytelling, understanding your audience, and sparking action. In this guide, I'll cover the essentials to help you write a compelling narrative that drives results.

What is the best format for a business case study presentation?

4 best format types for a business case study presentation:

- Problem-solution case study

- Before-and-after case study

- Success story case study

- Interview style case study

Each style has unique strengths, so pick one that aligns best with your story and audience. For a deeper dive into these formats, check out our detailed blog post on case study format types .

I also recommend watching this video breaking down the 9-step process for writing a case study:

What to include in a case study presentation?

An effective case study presentation contains 7 key elements:

- Introduction

- Company overview

- The problem/challenge

- Your solution

- Customer quotes/testimonials

To learn more about what should go in each of these sections, check out our post on what is a case study .

How to write a compelling narrative for your case study presentation?

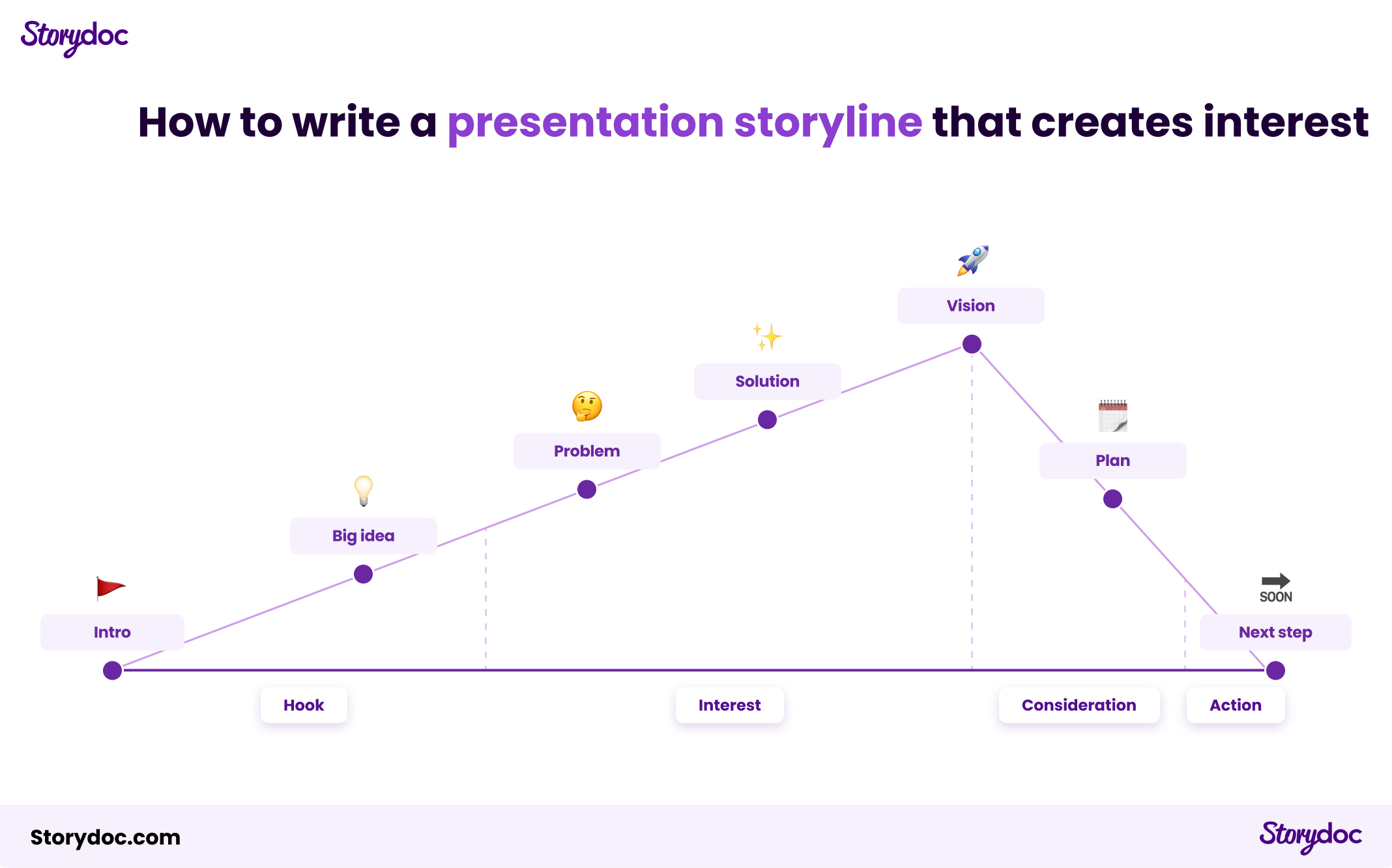

Storytelling is the heart of an engaging case study presentation. It involves more than just stringing events together. You should weave an emotional journey that your audience can relate to.

Begin with the challenge —illustrate the magnitude of the problem that was faced. Then, introduce your solution as the hero that comes to the rescue.

As you progress, ensure your narrative highlights the transformative journey from the problem state to the successful outcome.

Here’s our recommended storyline framework:

How to motivate readers to take action?

Based on BJ Fogg's behavior model , successful motivation involves 3 components:

Motivation is all about highlighting the benefits. Paint a vivid picture of the transformative results achieved using your solution. Use compelling data and emotive testimonials to amplify the desire for similar outcomes, therefore boosting your audience's motivation.

Ability refers to making the desired action easy to perform. Show how straightforward it is to implement your solution. Use clear language, break down complex ideas, and reinforce the message that success is not just possible, but also readily achievable with your offering.

Prompt is your powerful call-to-action (CTA), the spark that nudges your audience to take the next step. Ensure your CTA is clear, direct, and tied into the compelling narrative you've built. It should leave your audience with no doubt about what to do next and why they should do it.

Here’s how you can do it with Storydoc:

How to adapt your presentation for your specific audience?

Every audience is different, and a successful case study presentation speaks directly to its audience's needs, concerns, and desires.

Understanding your audience is crucial. This involves researching their pain points, their industry jargon, their ambitions, and their fears.

Then, tailor your presentation accordingly. Highlight how your solution addresses their specific problems. Use language and examples they're familiar with. Show them how your product or service can help them reach their goals.

A case study presentation that's tailor-made for its audience is not just a presentation—it's a conversation that resonates, engages, and convinces.

How to design a great case study presentation?

A powerful case study presentation is not only about the story you weave—it's about the visual journey you create.

Let's navigate through the design strategies that can transform your case study presentation into a gripping narrative.

Add interactive elements

Static design has long been the traditional route for case study presentations—linear, unchanging, a one-size-fits-all solution.

However, this has been a losing approach for a while now. Static content is killing engagement, but interactive design will bring it back to life.

It invites your audience into an evolving, immersive experience, transforming them from passive onlookers into active participants.

Which of these presentations would you prefer to read?

Use narrated content design (scrollytelling)

Scrollytelling combines the best of scrolling and storytelling. This innovative approach offers an interactive narrated journey controlled with a simple scroll.

It lets you break down complex content into manageable chunks and empowers your audience to control their reading pace.

To make this content experience available to everyone, our founder, Itai Amoza, collaborated with visualization scientist Prof. Steven Franconeri to incorporate scrollytelling into Storydoc.

This collaboration led to specialized storytelling slides that simplify content and enhance engagement (which you can find and use in Storydoc).

Here’s an example of Storydoc scrollytelling:

Bring your case study to life with multimedia

Multimedia brings a dynamic dimension to your presentation. Video testimonials lend authenticity and human connection. Podcast interviews add depth and diversity, while live graphs offer a visually captivating way to represent data.

Each media type contributes to a richer, more immersive narrative that keeps your audience engaged from beginning to end.

Prioritize mobile-friendly design

In an increasingly mobile world, design must adapt. Avoid traditional, non-responsive formats like PPT, PDF, and Word.

Opt for a mobile-optimized design that guarantees your presentation is always at its best, regardless of the device.

As a significant chunk of case studies are opened on mobile, this ensures wider accessibility and improved user experience , demonstrating respect for your audience's viewing preferences.

Here’s what a traditional static presentation looks like as opposed to a responsive deck:

Streamline the design process

Creating a case study presentation usually involves wrestling with a website builder.

It's a dance that often needs several partners - designers to make it look good, developers to make it work smoothly, and plenty of time to bring it all together.

Building, changing, and personalizing your case study can feel like you're climbing a mountain when all you need is to cross a hill.

By switching to Storydoc’s interactive case study creator , you won’t need a tech guru or a design whizz, just your own creativity.

You’ll be able to create a customized, interactive presentation for tailored use in sales prospecting or wherever you need it without the headache of mobilizing your entire team.

Storydoc will automatically adjust any change to your presentation layout, so you can’t break the design even if you tried.

Case study presentation examples that engage readers

Let’s take a deep dive into some standout case studies.

These examples go beyond just sharing information – they're all about captivating and inspiring readers. So, let’s jump in and uncover the secret behind what makes them so effective.

What makes this deck great:

- A video on the cover slide will cause 32% more people to interact with your case study .

- The running numbers slide allows you to present the key results your solution delivered in an easily digestible way.

- The ability to include 2 smart CTAs gives readers the choice between learning more about your solution and booking a meeting with you directly.

Light mode case study

- The ‘read more’ button is perfect if you want to present a longer case without overloading readers with walls of text.

- The timeline slide lets you present your solution in the form of a compelling narrative.

- A combination of text-based and visual slides allows you to add context to the main insights.

Marketing case study

- Tiered slides are perfect for presenting multiple features of your solution, particularly if they’re relevant to several use cases.

- Easily customizable slides allow you to personalize your case study to specific prospects’ needs and pain points.

- The ability to embed videos makes it possible to show your solution in action instead of trying to describe it purely with words.

UX case study

- Various data visualization components let you present hard data in a way that’s easier to understand and follow.

- The option to hide text under a 'Read more' button is great if you want to include research findings or present a longer case study.

- Content segmented using tabs , which is perfect if you want to describe different user research methodologies without overwhelming your audience.

Business case study

- Library of data visualization elements to choose from comes in handy for more data-heavy case studies.

- Ready-to-use graphics and images which can easily be replaced using our AI assistant or your own files.

- Information on the average reading time in the cover reduces bounce rate by 24% .

Modern case study

- Dynamic variables let you personalize your deck at scale in just a few clicks.

- Logo placeholder that can easily be replaced with your prospect's logo for an added personal touch.

- Several text placeholders that can be tweaked to perfection with the help of our AI assistant to truly drive your message home.

Real estate case study

- Plenty of image placeholders that can be easily edited in a couple of clicks to let you show photos of your most important listings.

- Data visualization components can be used to present real estate comps or the value of your listings for a specific time period.

- Interactive slides guide your readers through a captivating storyline, which is key in a highly-visual industry like real estate .

Medical case study

- Image and video placeholders are perfect for presenting your solution without relying on complex medical terminology.

- The ability to hide text under an accordion allows you to include research or clinical trial findings without overwhelming prospects with too much information.

- Clean interactive design stands out in a sea of old-school medical case studies, making your deck more memorable for prospective clients.

Dark mode case study

- The timeline slide is ideal for guiding readers through an attention-grabbing storyline or explaining complex processes.

- Dynamic layout with multiple image and video placeholders that can be replaced in a few clicks to best reflect the nature of your business.

- Testimonial slides that can easily be customized with quotes by your past customers to legitimize your solution in the eyes of prospects.

Grab a case study presentation template

Creating an effective case study presentation is not just about gathering data and organizing it in a document. You need to weave a narrative, create an impact, and most importantly, engage your reader.

So, why start from zero when interactive case study templates can take you halfway up?

Instead of wrestling with words and designs, pick a template that best suits your needs, and watch your data transform into an engaging and inspiring story.

Hi, I'm Dominika, Content Specialist at Storydoc. As a creative professional with experience in fashion, I'm here to show you how to amplify your brand message through the power of storytelling and eye-catching visuals.

Found this post useful?

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Get notified as more awesome content goes live.

(No spam, no ads, opt-out whenever)

You've just joined an elite group of people that make the top performing 1% of sales and marketing collateral.

Create your best pitch deck to date.

Stop losing opportunities to ineffective presentations. Your new amazing deck is one click away!

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Family Community Med

- v.12(2); May-Aug 2005

TEACHING TIPS: TWELVE TIPS FOR MAKING CASE PRESENTATIONS MORE INTERESTING *

1. set the stage.

Prepare the audience for what is to come. If the audience is composed of people of mixed expertise, spend a few minutes forming them into small mixed groups of novices and experts. Explain that this is an opportunity for the more junior to learn from the more senior people. Tell them that the case to be presented is extremely interesting, why it is so and what they may learn from it. The primary objective is to analyze the clinical reasoning that was used rather than the knowledge required, although the acquisition of such knowledge is an added benefit of the session. A “well organized case presentation or clinicopathological conference incorporates the logic of the workup implicitly and thus makes the diagnostic process seem almost preordained”.

A psychiatry resident began by introducing the case as an exciting one, explaining the process and dividing the audience into teams mixing people with varied expertise. He urged everyone to think in ‘real time’ rather than jump ahead and to refrain from considering information that is not normally available at the time: for example, a laboratory report that takes 24 hours to obtain be assessed in the initial workup.

2. PROVIDE ONLY INITIAL CUES AT FIRST

Give them the first two to live cues that were picked up in the first minute or two of the patient encounter either verbally, or written on a transparency. For example, age, sex race and reason for seeking medical help. Ask each group to discuss their first diagnostic hypotheses. Experts and novices will learn a great deal from each other at this stage and the discussions will be animated. The initial cues may number only one or two and hypothesis generation occurs very quickly even in the novices. Indeed, the only difference between the hypotheses of novices and those of experts is in the degree of refinement, not in number.

It is Saturday afternoon and you are the psychiatric emergency physician. A 25-year-old male arrives by ambulance and states that he is feeling suicidal. Groups talked for 4 minutes before the resident called for order to commence step three.

3. ASK FOR HYPOTHESES AND WRITE THEM UP ON THE BLACKBOARD

Call for order and ask people to offer their suggested diagnoses and write these up on a board or transparency.

The following hypotheses were suggested by the groups and the resident wrote them on a flip chart: depression, substance abuse, recent social stressors-crisis, adjustment disorder, organic problem, dysthymia, schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder. The initial three or four bits of information generated eight hypotheses.

4. ALLOW THE AUDIENCE TO ASK FOR INFORMATION

After all hypotheses have been listed instruct the audience to ask for the information they need to confirm or refute these hypotheses. Do not allow them to ‘jump the gun’ by asking for a test result, for example, that would not have been received within the time frame that is being re-lived. There will be a temptation to move too fast and the exercise is wasted if information is given too soon. Recall that the purpose is to help them go through a thinking process which requires time.

Teachers participating in this exercise will receive much diagnostic information about students’ thinking at this stage. Indeed, an interesting teaching session can be conducted by simply asking students to generate hypotheses without proceeding further. There is evidence to suggest that when a diagnosis is not considered initially it is unlikely to be reached over time, Hence it is worth spending time with students to discuss the hypotheses they generate before they proceed with an enquiry.

Directions to the group were to determine what questions they would like to ask, based on gender, age and probabilities, to support or exclude the listed diagnostic possibilities. A sample of question follow:

- Does he work? No, he's unemployed.

- Does he drink? one to three beers a week.

- Why now? He's been feeling worse and worse for the last 3 weeks.

- Social support? He gives alone. Has no girlfriend.

- Appearance? Looks his age. Not shaved today. No shower in 3 days.

- Cultural background? Refugee from Iraq. Muslim.

- How did he get here? He spent 4 years in a refugee camp after spending 4 months walking to Pakistan from Iraq. He left Iraq to avoid military service.

- Suicide thoughts? Increasing the last 3 weeks. He was admitted in December and has been taking chloral hydrate.

This step took 13 minutes.

5. HAVE THE AUDIENCE RE-FORMULATE THEIR LIST OF HYPOTHESES

After enough information has been gained to proceed, ask them to resume their discussion about the problem and reformulate their diagnostic hypotheses in light of the new information. Instruct them to discuss which pieces of information changed the working diagnosis and why. Call for order again and ask people what they now think.

After allowing the group to talk for a few minutes, the resident asked them if there was enough information to strike off any hypotheses or if new hypotheses should be added to the list. One more possibility was added, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). One group's list of priorities was major affective disorder with psychosis, schizophrenia, personality disorder. Another group also placed affective disorder first followed by organic mood disorder.

This step took 25 minutes.

6. FACILITATE A DISCUSSION ABOUT REASONING

Alter the original lists of hypotheses on the board in light of the discussion, or allow one member from each group to alter their own lists. By the use of open-ended questions encourage a general discussion about the reasons a group has for preferring one diagnosis over another.

A general discussion ensued about reasons for these priorities. Then the list was altered so that it read: schizophrenia, personality disorder, PTSD, major affective disorder with psychosis, organic mood disorder.

7. ALLOW ANOTHER ROUND OF INFORMATION SEEKING

Continue with another round of information and small-group discussion or else allow the whole group to interact. By giving information only when asked for and only in correct sequence, each person is challenged to think through the problem.

More information was sought, such as: form of speech? eye contact? affect? substance use? After 5 minutes the resident asked if there were only lab tests they would like. The group asked for thyroid stimulating hormone, T4, electrolytes and were given the results. They also asked for the results of the physical examination and were told that the pulse was 110 and the thyroid was enlarged. At this point some hypotheses were removed from the list.

8. ASK GROUPS TO REACH A FINAL DIAGNOSIS

When there is a lull in the search for information, ask the groups to reach consensus on their final diagnosis, given the information they have. Allow discussion within the groups.

9. CALL FOR EACH GROUP'S FINAL DIAGNOSIS

On each group's list of hypothesis, star or underline the final diagnosis.

The group decided that the most likely diagnosis was affective disorder with psychosis, the actual working diagnosis of the patient.

10. ASK FOR MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

If there is enough time, ask them to form small groups again to discuss treatment options, or conduct the discussion as a large group. Again ask for the reasons why one approach is preferred over another. Particularly ask the experts in the room for their reasoning so that the novices can learn from them.

11. SUMMARIZE

By the time the end is in sight the audience will be so involved that they will not wish to leave. However, 5 minutes before time, call for order and summarize the session. Highlight the key points that have been raised and refer to the objective of the session.

We are now at the end of our time. You have all had the opportunity to use your clinical reasoning skills to generate several hypotheses which are shown on the board. Initially you thought it possible that this man could have any one of a number of diagnoses including depression, substance abuse, adjustment disorder with depressed mood, organic mood disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder. With further information the possible diagnosis shifted to include schizophrenia and personality disorder as well as depression with psychotic features. Finally the diagnosis of depression or mood disorder with psychosis was most strongly supported because of the history of consistently depressed mood over several months, along with disturbed sleep, poor appetite, weight loss, decreased energy and diminished interest in most activities. The initially abnormal thyroid test proved to be a red herring so organic mood disorder related to hyper- or hypo-thyroidism was excluded. Additionally absence of vivid dreams involving a traumatic event made a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder unlikely. Although a diagnosis of schizophrenia could not be totally excluded, this seemed less likely given the findings.

12. CLOSE THE SESSION WITH POSITIVE FEEDBACK

In some respects, but only some, teaching is like acting and one should strive to leave them not laughing as you go, but feeling that they have learned something.

The more novice members of the group have learned from the more experienced and all your suggestions have been valid. It has been interesting for me to follow your reasoning and compare it with mine when I actually saw this man. You have given me a different perspective as you thought of things I had not, and I thank you for your participation.

Although case presentation should be a major learning experience for both novice and experienced physicians they are often conducted in a stultifying way that defies thought. We have presented a series of steps which, if followed, guarantee active participation from the audience and ensure that if experts are in the room their expertise is used. Physicians have been moulded to believe that teaching means telling and, as a consequence, adopt a remote listening stance during case presentations. Indeed the back row often use the time to catch up on much needed sleep! Changing the format requires courage. We urge you to try out these steps so that both you and your audience will learn from and enjoy the process.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to present...

How to present clinical cases

- Related content

- Peer review

- Ademola Olaitan , medical student 1 ,

- Oluwakemi Okunade , final year medical student 1 ,

- Jonathan Corne , consultant physician 2

- 1 University of Nottingham

- 2 Nottingham University Hospitals

Presenting a patient is an essential skill that is rarely taught

Clinical presenting is the language that doctors use to communicate with each other every day of their working lives. Effective communication between doctors is crucial, considering the collaborative nature of medicine. As a medical student and later as a doctor you will be expected to present cases to peers and senior colleagues. This may be in the setting of handovers, referring a patient to another specialty, or requesting an opinion on a patient.

A well delivered case presentation will facilitate patient care, act a stimulus for timely intervention, and help identify individual and group learning needs. 1 Case presentations are also used as a tool for assessing clinical competencies at undergraduate and postgraduate level.

Medical students are taught how to take histories, examine, and communicate effectively with patients. However, we are expected to learn how to present effectively by observation, trial, and error.

Principles of presentation

Remember that the purpose of the case presentation is to convey your diagnostic reasoning to the listener. By the end of your presentation the examiner should have a clear view of the patient’s condition. Your presentation should include all the facts required to formulate a management plan.

There are no hard and fast rules for a perfect presentation, rather the content of each presentation should be determined by the case, the context, and the audience. For example, presenting a newly admitted patient with complex social issues on a medical ward round will be very different from presenting a patient with a perforated duodenal ulcer who is in need of an emergency laparotomy.

Whether you’re presenting on a busy ward round or during an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), it is important that you are concise yet get across all the important points. Start by introducing patients with identifiers such as age, sex, and occupation, and move on to the complaint that they presented with or the reason that they are in hospital. The presenting complaint is an important signpost and should always be clearly stated at the start of the presentation.

Presenting a history

After you’ve introduced the patient and stated the presenting complaint, you can proceed in a chronological approach—for example, “Mr X came in yesterday with worsening shortness of breath, which he first noticed four days ago.” Alternatively you can discuss each of the problems, starting with the most pertinent and then going through each symptom in turn. This method is especially useful in patients who have several important comorbidities.

The rest of the history can then be presented in the standard format of presenting complaint, history of presenting complaint, medical history, drug history, family history, and social history. Strictly speaking there is no right or wrong place to insert any piece of information. However, in some instances it may be more appropriate to present some information as part of the history of presenting complaints rather than sticking rigidly to the standard format. For example, in a patient who presents with haemoptysis, a mention of relevant risk factors such as smoking or contacts with tuberculosis guides the listener down a specific diagnostic pathway.

Apart from deciding at what point to present particular pieces of information, it is also important to know what is relevant and should be included, and what is not. Although there is some variation in what your seniors might view as important features of the history, there are some aspects which are universally agreed to be essential. These include identifying the chief complaint, accurately describing the patient’s symptoms, a logical sequence of events, and an assessment of the most important problems. In addition, senior medical students will be expected to devise a management plan. 1

The detail in the family and social history should be adapted to the situation. So, having 12 cats is irrelevant in a patient who presents with acute appendicitis but can be relevant in a patient who presents with an acute asthma attack. Discerning the irrelevant from the relevant is not always easy, but it comes with experience. 2 In the meantime, learning about the diseases and their associated features can help to guide you in the things you need to ask about in your history. Indeed, it is impossible to present a good clinical history if you haven’t taken a good history from the patient.

Presenting examination findings

When presenting examination findings remember that the aim is to paint a clear picture of the patient’s clinical status. Help the listener to decide firstly whether the patient is acutely unwell by describing basics such as whether the patient is comfortable at rest, respiratory rate, pulse, and blood pressure. Is the patient pyrexial? Is the patient in pain? Is the patient alert and orientated? These descriptions allow the listener to quickly form a mental picture of the patient’s clinical status. After giving an overall picture of the patient you can move on to present specific findings about the systems in question. It is important to include particular negative findings because they can influence the patient’s management. For example, in a patient with heart failure it is helpful to state whether the patient has a raised jugular venous pressure, or if someone has a large thyroid swelling it is useful to comment on whether the trachea is displaced. Initially, students may find it difficult to know which details are relevant to the case presentation; however, this skill becomes honed with increasing knowledge and clinical experience.

Presenting in an exam

Although the same principles as presenting in other situations also apply in an exam setting, the exam situation differs in the sense that its purpose is for you to show your clinical competence to the examiner.

It’s all about making a good impression. Walk into the room confidently and with a smile. After taking the history or examining the patient, turn to the examiner and look at him or her before starting to present your findings. Avoid looking back at the patient while presenting. A good way to avoid appearing fiddly is to hold your stethoscope behind your back. You can then wring to your heart’s content without the examiner sensing your imminent nervous breakdown.

Start with an opening statement as you would in any other situation, before moving on to the main body of the presentation. When presenting the main body of your history or examination make sure that you show the examiner how your findings are linked to each other and how they come together to support your conclusion.

Finally, a good summary is just as important as a good introduction. Always end your presentation with two or three sentences that summarise the patient’s main problem. It can go something like this: “In summary, this is Mrs X, a lifelong smoker with a strong family history of cardiovascular disease, who has intermittent episodes of chest pain suggestive of stable angina.”

Improving your skills

The RIME model (reporter, interpreter, manager, and educator) gives the natural progression of the clinical skills of a medical student. 3 Early on in clinical practice students are simply reporters of information. As the student progresses and is able to link together symptoms, signs, and investigation results to come up with a differential diagnosis, he or she becomes an interpreter of information. With further development of clinical skills and increasing knowledge students are actively able to suggest management plans. Finally, managers progress to become educators. The development from reporter to manager is reflected in the student’s case presentations.

The key to improving presentation skills is to practise, practise, and then practise some more. So seize every opportunity to present to your colleagues and seniors, and reflect on the feedback you receive. 4 Additionally, by observing colleagues and doctors you can see how to and how not to present.

Remember the purpose of the presentation

Be flexible; the context should dictate the content of the presentation

Always include a presenting complaint

Present your findings in a way that shows understanding

Have a system

Use appropriate terminology

Additional tips for exams

Start with a clear introductory statement and close with a brief summary

After your summary suggest a working diagnosis and a management plan

Practise, practise, practise, and get feedback

Present with confidence, and don’t be put off by an examiner’s poker face

Be honest; do not make up signs to fit in with your diagnosis

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2010;18:c1539

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

See “Medical ward rounds” ( Student BMJ 2009;17:98-9, http://archive.student.bmj.com/issues/09/03/life/98.php ).

- ↵ Green EH, Durning SJ, DeCherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe B, Hershman W. Expectations for oral case presentations for clinical clerks: Opinions of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med 2009 ; 24 : 370 -3. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Lingard LA, Haber RJ. What do we mean by “relevance”? A clinical and rhetorical definition with implications for teaching and learning the case-presentation format. Acad Med 1999 ; 74 : S124 -7. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med 1999 ; 74 : 1203 -7. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Haber RJ, Lingard LA. Learning oral presentation skills: a rhetorical analysis with pedagogical and professional implications. J Gen Intern Med 2001 ; 16 : 308 -14. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

Featured Clinical Reviews

- Screening for Atrial Fibrillation: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement JAMA Recommendation Statement January 25, 2022

- Evaluating the Patient With a Pulmonary Nodule: A Review JAMA Review January 18, 2022

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

The Oral Case Presentation : A Key Tool for Assessment and Teaching in Competency-Based Medical Education

- 1 Wilson Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- 2 Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- 3 HoPingKong Centre, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Oral case presentations by trainees to supervisors are core activities in academic hospitals across all disciplines and form a key milestone in US and Canadian educational frameworks. Yet despite their widespread use, there has been limited attention devoted to developing case presentations as tools for structured teaching and assessment. In this Viewpoint, we discuss the challenges in using oral case presentations in medical education, including lack of standardization, high cognitive demands, and the role of trust between supervisor and trainee. We also articulate how, by addressing these tensions, case presentations can play an important role in competency-based education, both for assessment of clinical competence and for teaching clinical reasoning.

Read More About

Melvin L , Cavalcanti RB. The Oral Case Presentation : A Key Tool for Assessment and Teaching in Competency-Based Medical Education . JAMA. 2016;316(21):2187–2188. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.16415

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

IMAGES

VIDEO