Home — Essay Samples — Law, Crime & Punishment — Distracted Driving — Thesis Statement For Texting And Driving

Thesis Statement for Texting and Driving

- Categories: Distracted Driving

About this sample

Words: 1081 |

Published: Mar 25, 2024

Words: 1081 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Law, Crime & Punishment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 540 words

2 pages / 691 words

2 pages / 867 words

3 pages / 1529 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Distracted Driving

Aggressive driving, a term that encompasses a range of hazardous behaviors displayed by motorists, is a pressing issue in today's society. It not only endangers lives on the road but also has far-reaching consequences for our [...]

Harper Lee's classic novel, "To Kill a Mockingbird," has captivated readers since its publication in 1960. With its exploration of themes such as racial prejudice, morality, and the loss of innocence, the novel continues to [...]

In today's digital age, technology has radically transformed our daily experiences. Smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other electronic devices have become an integral part of our lives. However, this reliance on technology has [...]

As a college student, the issue of speed limits and their importance in ensuring safety on the roads is a topic that cannot be overlooked. Violating speed limits has become a common practice among drivers in many countries, with [...]

Driving distractions are common nowadays, such as eating or drinking, looking at scenery and talking with passengers. One of the most serious of these distractions is using smartphones while driving. This distraction is a common [...]

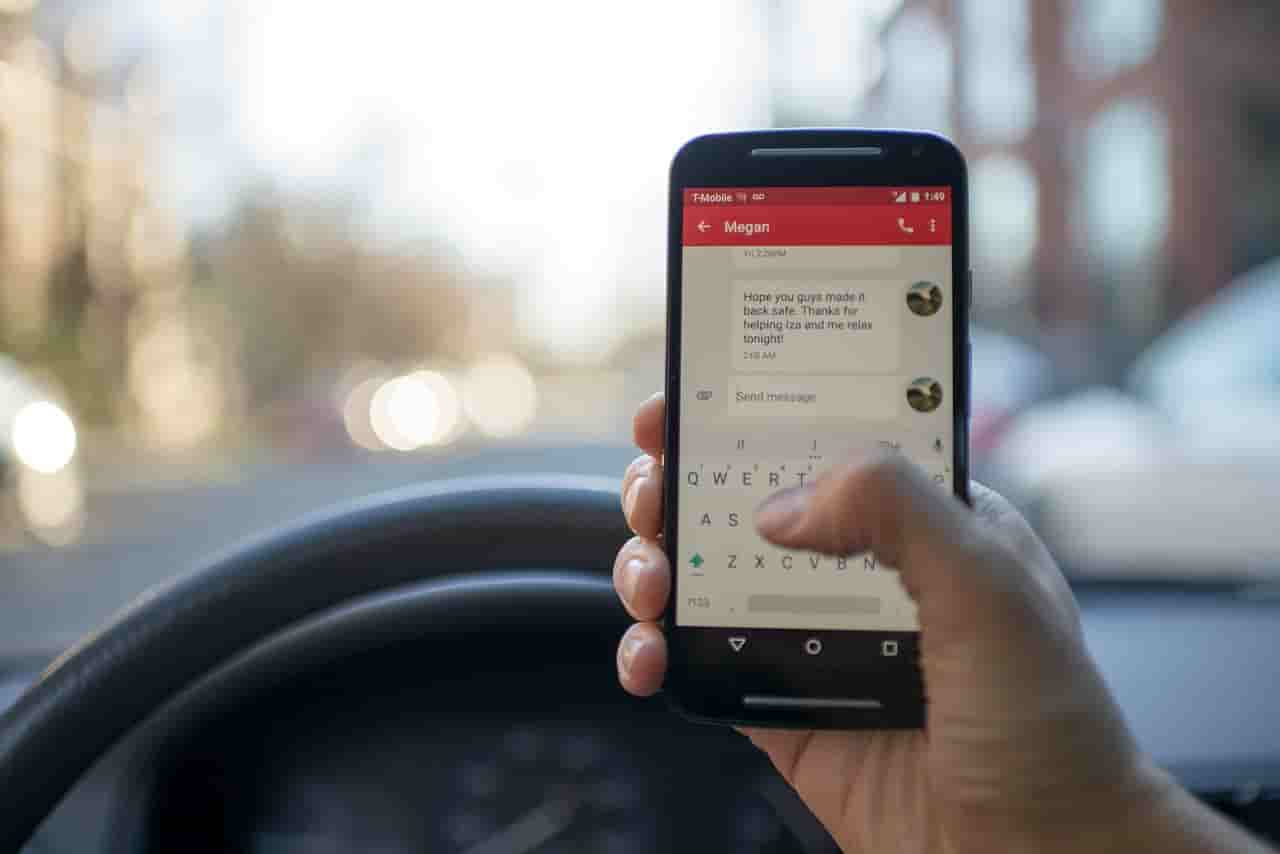

Texting while driving has become an epidemic in our modern society. With the rise of smartphones and the constant need for connectivity, more and more drivers are engaging in this dangerous behavior. However, the consequences of [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

107 Texting and Driving Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Texting and driving is a dangerous combination that has become a major issue on the roads today. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, texting while driving is six times more dangerous than driving drunk. Despite the risks, many drivers continue to engage in this dangerous behavior, putting themselves and others at risk.

If you have been tasked with writing an essay on texting and driving, you may be struggling to come up with a topic. To help you get started, here are 107 texting and driving essay topic ideas and examples:

- The dangers of texting and driving

- The statistics on texting and driving accidents

- The psychological effects of texting and driving

- The legal consequences of texting and driving

- The impact of texting and driving on society

- The role of technology in preventing texting and driving

- The effectiveness of texting and driving laws

- The influence of peer pressure on texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on insurance rates

- The relationship between texting and driving and other risky behaviors

- The role of education in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on emergency response times

- The effects of texting and driving on cognitive function

- The correlation between texting and driving and car accidents

- The role of social media in promoting safe driving habits

- The impact of distracted driving on workplace productivity

- The relationship between texting and driving and mental health

- The effects of texting and driving on personal relationships

- The role of parents in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on pedestrian safety

- The correlation between texting and driving and road rage

- The relationship between texting and driving and substance abuse

- The effects of texting and driving on sleep patterns

- The role of technology in detecting and preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on academic performance

- The correlation between texting and driving and anxiety

- The relationship between texting and driving and self-esteem

- The effects of texting and driving on decision-making skills

- The role of law enforcement in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on job prospects

- The correlation between texting and driving and depression

- The relationship between texting and driving and eating disorders

- The effects of texting and driving on memory retention

- The role of healthcare providers in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on financial stability

- The correlation between texting and driving and physical health

- The relationship between texting and driving and emotional well-being

- The effects of texting and driving on social skills

- The role of government agencies in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on community safety

- The correlation between texting and driving and social isolation

- The relationship between texting and driving and substance use disorders

- The effects of texting and driving on decision-making processes

- The role of technology companies in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on family dynamics

- The correlation between texting and driving and learning disabilities

- The relationship between texting and driving and physical fitness

- The effects of texting and driving on problem-solving abilities

- The role of media in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on stress levels

- The correlation between texting and driving and communication skills

- The relationship between texting and driving and time management

- The effects of texting and driving on creativity

- The role of advocacy groups in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on personal development

- The correlation between texting and driving and career advancement

- The relationship between texting and driving and academic success

- The effects of texting and driving on physical coordination

- The role of technology addiction in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on mental acuity

- The correlation between texting and driving and emotional intelligence

- The relationship between texting and driving and problem-solving skills

- The effects of texting and driving on decision-making abilities

- The role of social media addiction in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on social relationships

- The correlation between texting and driving and academic achievement

- The relationship between texting and driving and professional success

- The effects of texting and driving on personal growth

- The role of peer pressure in preventing texting and driving

- The impact of distracted driving on physical health

- The correlation between texting and driving and mental well-being

- The relationship between texting and driving and emotional health

- The effects of texting and driving on social development

- The impact of distracted driving on emotional intelligence

- The correlation between texting and driving and cognitive abilities

- The relationship between texting and driving and decision-making skills

- The effects of texting and driving on problem-solving skills

- The impact of distracted driving on interpersonal relationships

- The correlation between texting and driving and academic performance

- The relationship between texting and driving and career success

- The effects of texting and driving on personal fulfillment

- The impact of distracted driving on physical well-being

- The correlation between texting and driving and mental health

- The impact of distracted driving on social connections

These are just a few examples of texting and driving essay topics that you can explore in your writing. Remember to choose a topic that interests you and that you feel passionate about, as this will make your essay more engaging and impactful. By raising awareness about the dangers of texting and driving through your writing, you can help make the roads safer for everyone.

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

Distracted Driving

- Types of Distraction

- How big is the problem?

- Who is most at risk for distracted driving?

- How to Prevent Distracted Driving

- What States are Doing to Prevent Distracted Driving

- What the Federal Government is Doing to Prevent Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving Fact Sheet

- Additional Resources

Nine people in the United States are killed every day in crashes that are reported to involve a distracted driver . 1

Distracted driving is doing another activity that takes the driver’s attention away from driving. Distracted driving can increase the chance of a motor vehicle crash.

Anything that takes your attention away from driving can be a distraction. Sending a text message, talking on a cell phone, using a navigation system, and eating while driving are a few examples of distracted driving. Any of these distractions can endanger you, your passengers, and others on the road.

There are three main types of distraction: 2

- Visual: taking your eyes off the road

- Manual: taking your hands off the wheel

- Cognitive: taking your mind off driving

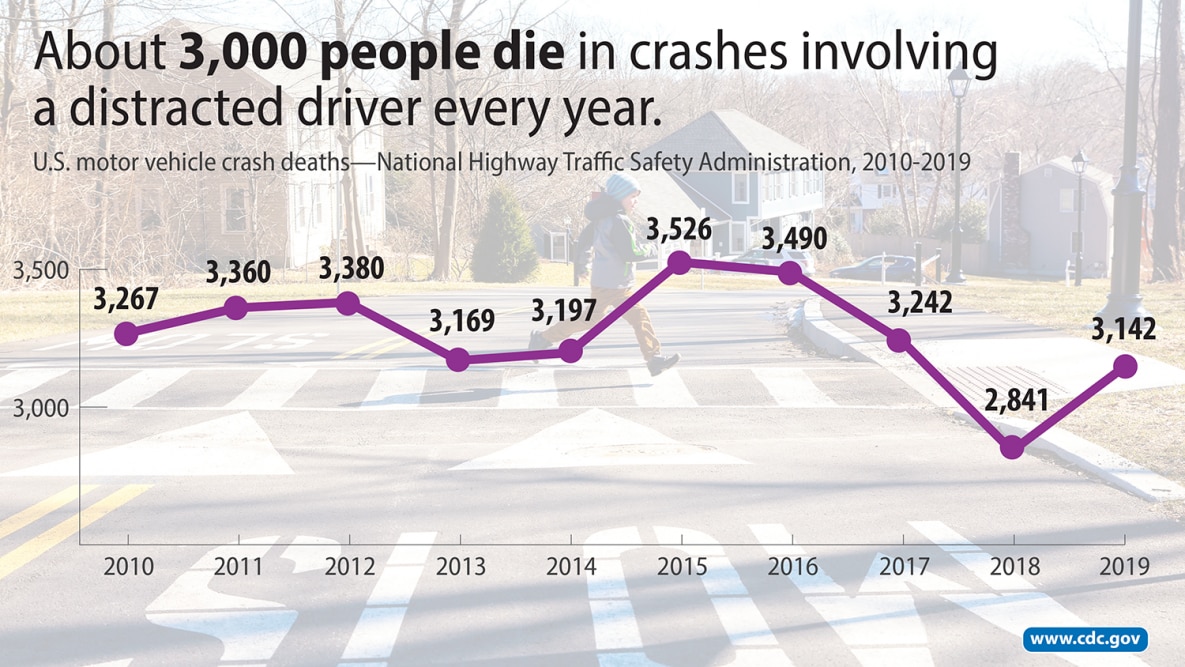

- In the United States, over 3,100 people were killed and about 424,000 were injured in crashes involving a distracted driver in 2019. 1

- About 1 in 5 of the people who died in crashes involving a distracted driver in 2019 were not in vehicles―they were walking, riding their bikes, or otherwise outside a vehicle. 1

Sources: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2010-2013 , 2014–2018 and 2019

You can visit the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) website for more information on how data on motor vehicle crash deaths are collected and the limitations of distracted driving data.

Young adult and teen drivers

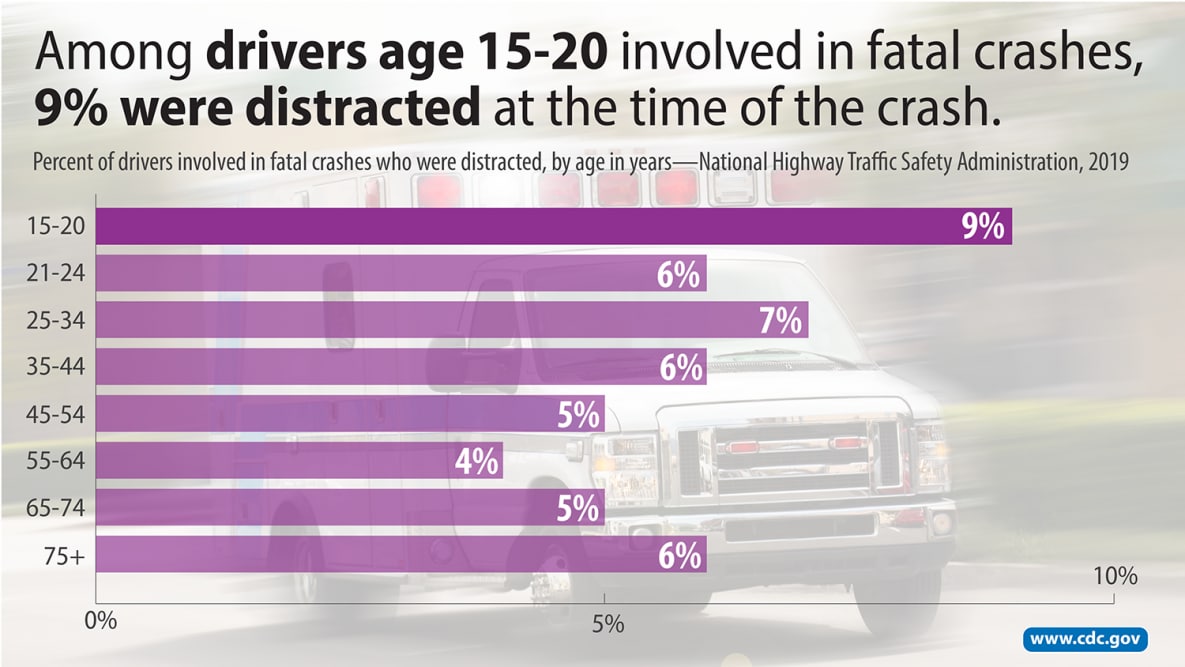

- A higher percentage of drivers ages 15–20 were distracted than drivers age 21 and older.

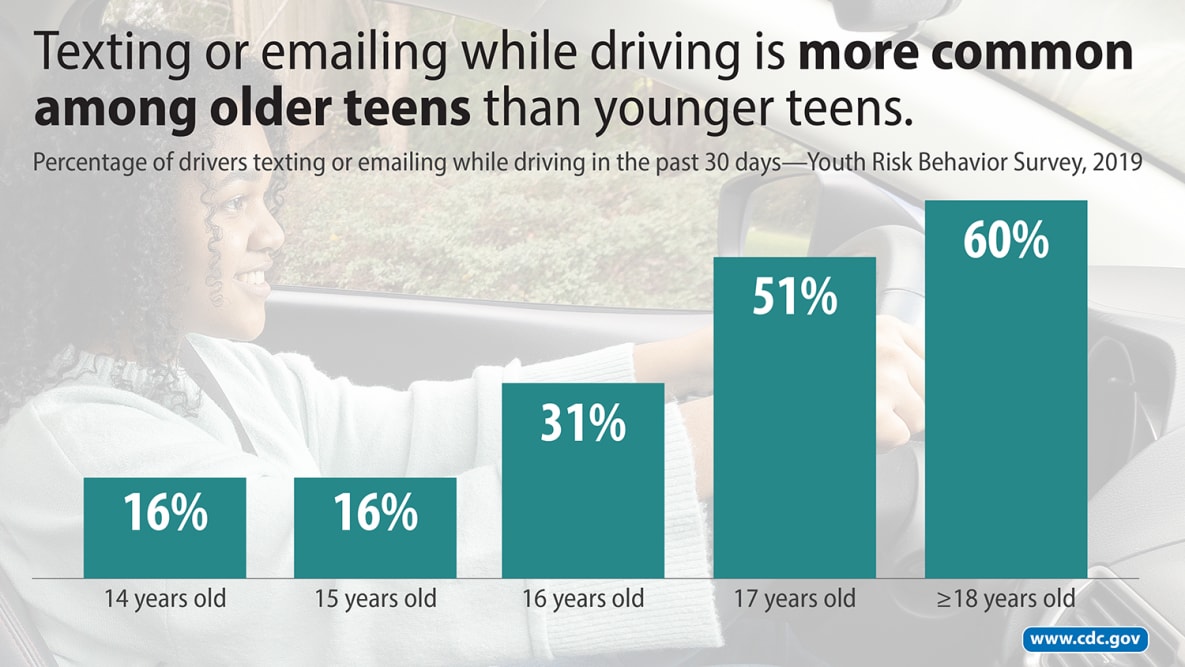

- 39% of high school students who drove in the past 30 days texted or emailed while driving on at least one of those days. 4

- Texting or emailing while driving was more common among older students than younger students (see figure below) and more common among White students (44%) than Black (30%) or Hispanic students (35%). 4

- Texting or emailing while driving was as common among students whose grades were mostly As or Bs as among students with mostly Cs, Ds, or Fs. 4

- more likely to not always wear a seat belt;

- more likely to ride with a driver who had been drinking alcohol; and

- more likely to drive after drinking alcohol. 4

Source: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration , 2019

Source : Transportation Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

What drivers can do

- Do not multitask while driving. Whether it’s adjusting your mirrors, selecting music, eating, making a phone call, or reading a text or email―do it before or after your trip, not during.

- You can use apps to help you avoid cell phone use while driving. Consider trying an app to reduce distractions while driving.

What passengers can do

- Speak up if you are a passenger in a car with a distracted driver. Ask the driver to focus on driving.

- Reduce distractions for the driver by assisting with navigation or other tasks.

What parents can do 5

- Remind them driving is a skill that requires the driver’s full attention.

- Emphasize that texts and phone calls can wait until arriving at a destination.

- Familiarize yourself with your state’s graduated driver licensing system and enforce its guidelines for your teen.

- Know your state’s laws on distracted driving . Many states have novice driver provisions in their distracted driving laws. Talk with your teen about the consequences of distracted driving and make yourself and your teen aware of your state’s penalties for talking or texting while driving.

- Set consequences for distracted driving. Fill out CDC’s Parent-Teen Driving Agreement [PDF – 465 KB] together to begin a safe driving discussion and set your family’s rules of the road. Your family’s rules of the road can be stricter than your state’s law. You can also use these simple and effective ways to get involved with your teen’s driving: Parents Are the Key.

- Set an example by keeping your eyes on the road and your hands on the wheel while driving.

- Learn more: visit NHTSA’s website on safe teen driving .

- The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety tracks cell phone use laws and young passenger restrictions by state.

- 4.1% to 2.7% in the Sacramento Valley Region in California, 6

- 6.8% to 2.9% in Hartford, Connecticut, 7

- 4.5% to 3.0% in the state of Delaware, 6 and

- 3.7% to 2.5% in Syracuse, New York. 7

- Graduated driver licensing (GDL) is a system which helps new drivers gain experience under low-risk conditions by granting driving privileges in stages. Comprehensive GDL systems include five components 8- 9 , one of which addresses distracted driving: the young passenger restriction. 10 CDC’s GDL Planning Guide [PDF – 3 MB] can assist states in assessing, developing, and implementing actionable plans to strengthen their GDL systems.

- Some states have installed rumble strips on highways to alert drowsy, distracted, or otherwise inattentive drivers that they are about to go off the road. These rumble strips are effective at reducing certain types of crashes. 10

- CDC has developed the Parents Are the Key campaign, which helps parents, pediatricians, and communities help keep teen drivers safe on the road.

- In 2022, the U.S. Department of Transportation released the National Roadway Safety Strategy [PDF – 42 pages] . Part of the strategy includes supporting vehicle technology systems that detect distracted driving.

- In 2021, Congress provided resources to add distracted driving awareness as part of driver’s license exams as part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law [PDF – 1039 pages] .

- In 2009, President Obama issued an Executive Order prohibiting federal employees from texting while driving government-owned vehicles or when driving privately owned vehicles on official government business.

- In 2010, the Federal Railroad Administration banned cell phone and electronic device use for railroad operating employees on the job.

- In 2010, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration banned commercial vehicle drivers from texting while driving.

- In 2011, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration banned all hand-held cell phone use by commercial drivers and drivers carrying hazardous materials.

- NHTSA has several campaigns to raise awareness of the dangers of distracted driving, including their annual “U Drive. U Text. U Pay.” campaign, which began in April 2014.

- NHTSA has issued voluntary guidelines to promote safety by discouraging the introduction of both original, in-vehicle [PDF – 177 pages] and portable/aftermarket [PDF – 96 pages] electronic devices in vehicles.

This fact sheet provides an overview of distracted driving and promising strategies that are being used to address distracted driving.

Distracted Driving Summary Fact Sheet [PDF – 660 KB]

- CDC MMWR – Transportation Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019

- CDC MMWR – Mobile Device Use While Driving — United States and Seven European Countries, 2011

- NHTSA – Distracted Driving

- Governors Highway Safety Association – Distracted Driving

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety – Distracted Driving

- World Health Organization – Mobile Phone Use: A Growing Problem of Driver Distraction

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) – Distracted Driving at Work

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) – Campaign Materials

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2021). Traffic Safety Facts Research Note: Distracted Driving 2019 (DOT HS 813 111) . Department of Transportation, Washington, DC: NHTSA. Accessed 8 February 2022.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2010). Overview of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Driver Distraction Program (DOT HS 811 299) [PDF – 36 pages] . U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC. Accessed 8 February 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System . Accessed 8 February 2022.

- Yellman, M.A., Bryan, L., Sauber-Schatz, E.K., Brener, N. (2020). Transportation Risk Behaviors Among High School Students — Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019 . MMWR Suppl, 69(Suppl-1),77–83.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Teen Driving . Accessed 8 February 2022.

- Chaudhary, N.K., Connolly, J., Tison, J., Solomon, M., & Elliott, K. (2015). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Evaluation of the NHTSA Distracted Driving High-Visibility Enforcement Demonstration Projects in California and Delaware [PDF – 72 pages] (DOT HS 812 108) . U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC.

- Chaudhary, N.K., Casanova-Powell, T.D., Cosgrove, L., Reagan, I., & Williams, A. (2012). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Evaluation of NHTSA Distracted Driving Demonstration Projects in Connecticut and New York [PDF – 80 pages] (DOT HS 811 635) . U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Motor Vehicle Injuries . Accessed 8 February 2022.

- Venkatraman, V., Richard, C. M., Magee, K., & Johnson, K. (2021). Countermeasures that work: A highway safety countermeasures guide for State Highway Safety Offices, 10 th edition, 2020 (Report No. DOT HS 813 097) [PDF – 641 pages] . U.S. Department of Transportation, Washington, DC.

- Federal Highway Administration. (2011). Technical Advisory: Shoulder and Edge Line Rumble Strips (T 5040.39, Revision 1) [PDF – 9 pages] . Department of Transportation, Washington, DC: FHWA. Accessed 24 August 2020.

To receive email updates about this topic, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

117 Distracted Driving Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best distracted driving topic ideas & essay examples, 🎓 good research topics about distracted driving, 💡 most interesting distracted driving topics to write about, ⭐ simple & easy distracted driving essay titles, ❓ questions about distracted driving.

- Texting While Driving Should Be Illegal To begin with, it has been observed from recent studies that have been conducted that majority of American citizens are in complete agreement that texting while one is driving should be banned as it is […]

- Banning Phone Use While Driving Will Save Lives For instance, a driver may receive a phone call or make one, and while tending to the call, takes his mind of the road and increasing the chances of causing an accident. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Persuading People Not to Text While Driving It is believed that the main reasons for the growing number of car accidents and deaths on the roads is the development of new technologies and, as a result, the irresponsible driving of individuals who […]

- Dangers of Texting while Driving The research paper will present some statistics to prove that texting while driving is one of the biggest contributors of road accidents in American roads.

- Drinking and Driving: The Negative Effects The combination of drinking and driving is dangerous and characterized by such effects as physiological changes, problems with the law, and innocent victims. One of the main effects of drinking and driving is the increase […]

- Age Limitation on Driving Privileges Thus, the increase in the level of accidents has forced the state to consider whether age is among the factors that have led to the increase in cases accidents.

- Public Service Announcement and Distracted Driving To conclude, PSAs help to reduce the amount of distracted driving occurrences. As a result, public service announcements should be utilized to raise public awareness of the hazards of distracted driving and assist save lives.

- Driving in the Winter and in the Summer To conclude, winter and summer driving are comparable in practices of handling the vehicle but are associated with contrasting dangers. In the summer, the temperature is higher, leading to the expansion of tires, and there […]

- Safe Driving and Use of Cellphones in Cars In conclusion, it is recommended that all drivers have a cell phone in the car to assist with emergencies, navigation, and reporting crime.

- Substance Abuse and Driving Under Influence The list of felonies consists of possession of substances, possession of ammunition with marijuana and the distribution of substances. This way, a person would be able to enhance their well-being and the state of mental […]

- Dangerous Driving Case: Description, Investigation, Judicial Process, and Results The court maintained that the offense in the case was a statutory offense that implied the dangerous driving of the accused, whose eventuality resulted in the death of the woman victim.

- Anti-Drink Driving Intervention Plan Overall, the ultimate goal of this paper lies in identifying key tasks that would be undertaken at all stages of the social marketing intervention planning process and evaluating the potential success of the plan.

- Developing Strategic Plan for TLC Commission Future Self-Driving Cars A SWOT analysis of the issue would reveal that not many would trust the safety of self-driving cars. The research would be of much help as it would reveal that self-driving cars are not that […]

- Self-Driving Technologies and Supply Chain Management Due to the large-scale implementation of such technologies, the whole transportation system will be changed. Self-driving technologies can significantly improve the development of the transportation industry.

- Mobile Phone Use and Driving: Modelling Driver Distraction Effects Therefore, in order to increase attention during driving and improve the reaction to road events, it is advisable to prohibiting hand-held phone use while driving in all 50 states.

- Tougher Punishment for Texting While Driving However the Center for Cognitive Brain Imaging reported that texting while driving is a greater distraction than talking to others due to the time eyes are away from the road and the amount of cognitive […]

- The Use of Mobile Phone While Driving a Car The purpose of the study was to explore the effects of drivers’ use of mobile phones on the risk of a crash.

- Addressing a Problem of Elderly Driving The authors claim that there are two possible ways to address the issue of elderly driving: developing social programs and integrating modern technology. These actions will be beneficial to the safety of older individuals and […]

- Regulations on Multitasking While Driving Consequently, safe and effective driving is a task that demands concentration by the driver, and multi-tasking while driving should be discouraged and avoided for safety.

- Cell Phones While Driving: Is It Legal? The message conveyed over the phone takes priority and driving takes a back seat which inevitably results in an accident, the severity of the same depends on more factors than one, the most important of […]

- Local Crisis: Teenage Driving Fatalities in Alabama It was reported in the reader’s digest of the 2008 August edition that out of 50 states, Alabama had the 4th highest rate of deaths at 39.

- Cause and Effect of Teenagers Crazy Driving They have to acknowledge that they are the childhood role model for the kids and this includes being the indirect driving teacher of the child.

- Cell Phone Use and Driving: Mian vs. City of Ottawa However, the judge considers the disclosure of the disciplinary records to be irrelevant to the case. However, the Crown specifically stated that the disclosure of these records is not relevant to the case without O’Connor’s […]

- Cell Phone Use While Driving: Policy Analysis Therefore, in a public policy debate, proponents of regulation would argue that per capita healthcare savings and resulting QALY measures are significant enough to justify a ban on the use of private cellphones in driving […]

- Safe Driving Among American Youth as Health Issue It reviews the organization’s perspective on the issue and the strategies it proposes to reduce the risks of car accidents. The paper concentrates on safe driving for young people, summarizing the National Safety Council’s position […]

- Cell Phone Use in Driving and Recommended Policies Auditory, when on phone, drivers shift their focus to the sound of the phone instead of listening to the adjoining atmosphere on the road.

- Outcomes of the Phone Usage While Driving To the end of their lives, neither the victims’ loved ones nor the driver will be able to cope with the tragedy that resulted. The assertion that driving and texting or talking on the phone […]

- Driving Under the Influence: US Policies Driving under the influence is known to be one of the most threatening tendencies in the world of nowadays. One of the most common policies provided in order to decrease the risk of drunken driving […]

- Impacts of Texting While Driving on the Accidents The development of technologies used by adolescents for texting while driving leads to increasing the rates of accidents. Hypothesis: The development of technologies used by adolescents for texting while driving leads to increasing the rates […]

- The New Application “Stop Texting and Driving App” The application installed in the driver’s smartphone will disable every function when the vehicle is in motion. The device and the application have more features in order to reduce the rate of having an accident.

- Technology Development and Texting while Driving Working thesis: Although certain modern gadgets can be used to avoid texting while driving, the development of the sphere of mobile technologies has the negative impact on the dangerous trend of messaging while driving a […]

- Distracted Driving Behaviors in Adults The article notes that the results of the study highlighted the dangers of DDB other than texting and using cell phones.

- The South Dakota Legislature on Texting and Driving According to the authors of the article, the South Dakota Legislature needs to acknowledge the perils of texting and driving and place a ban on the practice.

- Injury Prevention Intervention: Driving Injury in Young People According to Gielen and Sleet study, the trends indicate that despite the preventive measures, the likelihood for young people involved in injuries is increasing. The collective objectives are to reduce the probability of young people […]

- Effects of Ageing Population as Driving Force Positive effects Negative effects An increased aging population will lead to a bigger market for goods and services associated with the elderly.

- Cognitive Psychology on Driving and Phone Usage For this reason, it is quite difficult to multitask when the activities involved are driving and talking on the phone. Holding a phone when driving may cause the driver to use only one hand for […]

- Banning Texting while Driving Saves Lives Other nations have limited use of phones, by teenagers, when driving, and a rising number of states and governments have prohibited the exact practice of texting while driving.

- Saving Lives: On the Ban of Texting While Driving To achieve the goals of the objectives proposed above, a comprehensive case study needs to be conducted on the risks of texting while driving and how the prohibition of the act will save lives.

- A Theoretical Analysis of the Act of Cell Phone Texting While Driving The past decade has seen the cell phone become the most common communication gadget in the world, and the US has one of the highest rates of cell phone use.

- Drivers of Automobiles Should Be Prohibited From Using Cellular Phones While Driving When a driver is utilizing a hand-held or hands-free cellular phone at the same time as driving, she or he should dedicate part of their concentration to operating the handset and sustaining the phone discussion […]

- Should People Be Banned From Using Cell Phones When Driving? Why or Why Not? Many people have blamed the cell phones to the current high increases in the number of road accidents witnessed worldwide, while others argue that the use of mobile phones while driving is not wholly to […]

- Problem of the Elderly Driving in the US When comparing the survey results to accumulated scientific data as well as statistics on the number of vehicular accidents involving the elderly it can be seen that the respondents were unaware of the potential danger […]

- The Dangers of Using Cell Phone While Driving The authors further note the subsequent increase in the count of persons conversing on cell phones while driving unaware of the risks they pose to themselves and their passengers.

- An Analysis of the Use of Cell Phones While Driving The first theory is the theory of mass society, and the second theory is the theory of the culture industry. The theory of mass society states that, popular culture is an intrinsic expression of the […]

- Popular Culture: The Use of Phones and Texting While Driving Given that rituals and stereotypes are a part of beliefs, values, and norms that society holds at a given instance of history, the use of phones in texting while driving has rituals and stereotypes associated […]

- The Use of the Cell Phone While Driving Indeed, many of the culprits of this dangerous practice are teens and the youth, ordinarily the most ardent expressers of popular culture in a society.

- Road Rage and the Possibilities of Slow Driving There is also a need for people to plan their daily activities early and give some time allowance to the expected driving time.

- Theta and Alpha Oscillations in Attentional Interaction During Distracted Driving

- Car Accidents and Distracted Driving

- The Pros and Cons of Distracted Driving

- Societal Crisis and Distracted Driving

- Texting and Driving Accident Statistics – Distracted Driving

- Major Safety Issue: Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving Should Not Be Banned

- Making Laws Against Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving Regulation and Education

- Prevent Distracted Driving

- The Problem Distracted Driving Creates

- Distracted Driving and Highway Fatalities

- Cell Phones and the Dangers of Distracted Driving

- Texting and Driving: Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving: Increase in Cell Phone Related Fatalities

- Cause and Effect: Non-distracted Driving and Distracting Driving

- Distracted Driving Involving Cell Phones

- The Most Dangerous Type of Distracted Driving

- Accidents and Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving and Doing Another Activity

- The Primary Factors Contributing to the Problem of Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving Prevention: Texting or Handheld Cellphone Use While Driving

- Attention and Distracted Driving

- The Dangers of Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving and Its Effects on Safety

- Motor Vehicle Safety: Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving While Using Handheld Electronic Device

- Mobile Communication and Local Information Flow: Evidence From Distracted Driving Laws

- Distracted Driving Prevention Act of 2011

- Texting While Driving: The Development and Validation of the Distracted Driving Survey and Risk Score Among Young Adults

- Causes, Impacts and Prevention Strategies of Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving: The Danger of the Technological Age

- Distracted Driving: How Badly Does Cell Phone Use Affect Drivers

- Opposing Perspectives and Solutions of Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving: The Preventable Killer

- The Facts About Distracted Driving

- Distracted Driving Bans Should Be Stronger

- The Cautionary Measures Against Distracted Driving Proposed by the State

- Distracted Driving and Dangerous Being Distracted While Driving

- What Are the Causes of Distracted Driving?

- What Is the Harm of Mobile Phones in Distracted Driving?

- What Are the Consequences of Distracted Driving?

- Should Distracted Driving Bans Be Stronger?

- What Are the Strategies to Prevent Distracted Driving?

- What Is the Act to Prevent Distracted Driving?

- How to Regulate Distracted Driving?

- Are Distracted Driving Fatalities Increasing?

- What Are Two Major Issues That Can Cause Distracted Driving?

- How Are Distracted Driving Laws Made?

- What Are the State Proposed Distracted Driving Precautions?

- What Is the Most Dangerous Type of Distracted Driving?

- What Are the Main Contributing Factors to the Problem of Distracted Driving?

- Why Has Distracted Driving Become a Societal Crisis?

- What Are Signs of a Distracted Driver?

- What Is an Example of a Mental Distraction Driving?

- What Types of Drivers Are More Susceptible to Distractions?

- Distracted Driving: How to Drive Safely?

- Does Distracted Driving Threaten the Safety of Not Only the Driver?

- How Many Accidents Are Caused by Distracted Driving?

- How to Learn Not to Be Distracted From Driving?

- What Issues Are Discussed at the Distracted Driving Summit?

- How Does Media Influence Distracted Driving?

- What Are the Opposing Views and Solutions to Distracted Driving?

- What Age Group Drives Distracted the Most?

- What Is the Most Dangerous Kind of Distracted Driving?

- How Many Highway Collisions Are Caused by Distracted Drivers?

- Can Fear Behind the Wheel Distract From Driving?

- How Many Americans Have Died From Distracted Driving?

- What Are Theta and Alpha Oscillations in the Interaction of Attention During Distracted Driving?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 26). 117 Distracted Driving Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/distracted-driving-essay-topics/

"117 Distracted Driving Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/distracted-driving-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '117 Distracted Driving Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "117 Distracted Driving Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/distracted-driving-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "117 Distracted Driving Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/distracted-driving-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "117 Distracted Driving Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/distracted-driving-essay-topics/.

- Texting and Driving Research Ideas

- Drunk Driving Essay Ideas

- Cell Phone Ideas

- Electric Vehicle Paper Topics

- Gasoline Prices Ideas

- Land Rover Ideas

- Marijuana Ideas

- Sleep Deprivation Research Ideas

- Uber Topics

- Vehicles Essay Topics

- Epilepsy Ideas

- Toyota Topics

- Volvo Essay Titles

- Cultural Competence Research Topics

Texting While Driving: A Literature Review on Driving Simulator Studies

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Automotive and Transport Engineering, Transilvania University of Brașov, 29 Eroilor Blvd., 500036 Brasov, Romania.

- 2 Department of Transportation Planning and Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, 5 Heroon Polytechniou str., GR-15773 Athens, Greece.

- PMID: 36901364

- PMCID: PMC10001711

- DOI: 10.3390/ijerph20054354

Road safety is increasingly threatened by distracted driving. Studies have shown that there is a significantly increased risk for a driver of being involved in a car crash due to visual distractions (not watching the road), manual distractions (hands are off the wheel for other non-driving activities), and cognitive and acoustic distractions (the driver is not focused on the driving task). Driving simulators (DSs) are powerful tools for identifying drivers' responses to different distracting factors in a safe manner. This paper aims to systematically review simulator-based studies to investigate what types of distractions are introduced when using the phone for texting while driving (TWD), what hardware and measures are used to analyze distraction, and what the impact of using mobile devices to read and write messages while driving is on driving performance. The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines. A total of 7151 studies were identified in the database search, of which 67 were included in the review, and they were analyzed in order to respond to four research questions. The main findings revealed that TWD distraction has negative effects on driving performance, affecting drivers' divided attention and concentration, which can lead to potentially life-threatening traffic events. We also provide several recommendations for driving simulators that can ensure high reliability and validity for experiments. This review can serve as a basis for regulators and interested parties to propose restrictions related to using mobile phones in a vehicle and improve road safety.

Keywords: distracted driving; literature review; simulator study; texting while driving.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Accidents, Traffic

- Automobile Driving*

- Cell Phone*

- Reproducibility of Results

- Text Messaging*

Grants and funding

- PN-III-P2-2.1-PED-2019-4366/Romanian Ministry of Education and Re-696 search

Texting And Driving Essay Sample

In today’s fast-paced world, people are constantly on the go. This is especially true of young drivers, who have a tendency to text and drive because it can be difficult to juggle all their responsibilities. However, this habit could be deadly as texting while driving increases the chances of being involved in an accident by 23%. In this essay, we will explore what makes texting while driving so risky and how you can avoid it.

Texting and driving essay writing help through the following sample is given by experts to the students. Students can refer to this essay for writing their own assignments.

Essay Example of Texting And Driving

- Thesis Statements of Texting And Driving Essay

- Introduction of Texting And Driving Essay

- Examples that shown that texting and driving is not good

- How to Stop the Practice of Texting and Driving

Thesis Statements of Texting And Driving Essay Texting and driving is a grave threat to our world today, but by taking the necessary precautions as drivers we can better ensure that it does not affect us or those close to us. Introduction of Texting And Driving Essay The modern time of technology has brought the mobile revolution to the entire world. Today you can see people of every age group fiddling their fingers on mobile phones. No real communication and dialogues have remained behind due to these mobile phones. Social networking sites are serving the purpose better for this cause. We can see that people keep on chatting for hours through these social networking sites. You must have come across many people on a regular basis that uses their mobile phone while driving. Either they are talking on the phone on chatting with their social friends while driving. This is very dangerous to texting while you are driving a vehicle. It can distract your focus from driving to your mobile screen. As a consequence of which you can become the reason for the death of an innocent person, or it could be you as well. Main Body of Texting And Driving Essay Examples that shown that texting and driving is not good There is enough evidence that has shown that texting and driving are not good for a safe life. It is just like the other form of the situation when you are driving and drinking. So many incidences and accidents have taken place so far due to this habit of people. Here are some points that will make you aware of the seriousness of the issue. A person who was texting while driving his car fails to listen to the horn of a truck that was coming from the opposite direction. As a result of which he meets with a drastic accident that takes away his life. A man was hospitalizing his pregnant wife during her labor pain, at the same time he was busy on phone. The results were very scary when they meet an accident in between the road. A similar case happens with a person who was listening to the music by plugging headphones in their ear, at the same time was busy with his texting to the friend on social media. He had to lose his life due to this ignorance of concentrating on driving. A lady who was dropping her kids at the school suddenly meets with a major accident on the road while chatting with her husband. There are several such examples that take our breath away from us owing to their seriousness. We really need to do something to eradicate this issue of texting and driving. Otherwise, it will eat our people like that of termite and we will not be aware of it. Get Non-Plagiarized Custom Essay on Texting And Driving in USA Order Now How to Stop the Practice of Texting and Driving Here are some ideas and tips that can help you to save yourself and others as well by not texting while driving. So go through these points very carefully. Try to Call your Friends when you get Time – If you are very keen to talk with your friends, it is very important to avoid them while you are driving. This is because by texting at the time of driving you are not just putting your life in danger but others as well. You might end up in the life of an innocent person due to your bad habit of texting and driving. Decide a Proper Time to Communicate or Chat with your Social Media Friends – In case you are not comfortable making a call to your social media friends and communicate with them through chat only, decide a proper time for that. It could be at the end of the day, or as per your time schedule, but make sure that you are not using the time of driving for this purpose. Be a responsible citizen by following the traffic rules of your country. Avoid Keeping your Mobile Phone in Front of you while Driving – When you will place your mobile phone in front of you it will keep on distracting you by forcing you to see the popup on the screen. Better you keep your phone in the pocket or bag, do not forget to turn off the message ringtone or popup while driving. This way you will be able to better concentrate on driving. Do not make social media Your World – Some people keep on chatting on their social media accounts all the time. This should be kept in mind that social media is a mean that helps you to communicate with the friends which are hard to do otherwise. But you cannot afford to lose the ones who are living with you. So drive safe and be responsible towards your family. Do Meditation and Self-Introspection on Regular Basis – When you will continuously get yourself involved in regular Yoga and exercise, it will help you to develop inner mental strength. You will come to know about the real purpose of life by forgetting to spend your entire day on social media. So make sure that you are doing exercise on daily basis. Hire USA Experts for Texting And Driving Essay Order Now Conclusion The discussions of the entire essay suggest us that we should avoid driving and texting to save the life of people on road along with our own life. This could be done when we are mentally aware of the destruction of texting and driving for mankind.

Get Essay Writing Services from USA-based Professional Writers

We hope the above-written essay sample has helped you understand why texting while driving can cause accidents and injuries.

Have you been having trouble with your essay writing, thesis research, or case study projects? If yes, please contact our team of experts. We offer online essay writing services for USA students. you can also find free essay samples on our website that can help you in writing essays.

Some of the essay samples are Gender Equality Essay , Loneliness Essay , Leadership Essay Example for Scholarship , and Domestic Violence essay .

We provide a wide range of academic writing services to meet your academic requirements. We have professional writers who have a wide range of knowledge in different disciplines. They can focus on your specific topic while providing you with an excellent essay paper or thesis research project without plagiarizing it from other sources.

Explore More Relevant Posts

- Nike Advertisement Analysis Essay Sample

- Mechanical Engineer Essay Example

- Reflective Essay on Teamwork

- Career Goals Essay Example

- Importance of Family Essay Example

- Causes of Teenage Depression Essay Sample

- Red Box Competitors Essay Sample

- Deontology Essay Example

- Biomedical Model of Health Essay Sample-Strengths and Weaknesses

- Effects Of Discrimination Essay Sample

- Meaning of Freedom Essay Example

- Women’s Rights Essay Sample

- Employment & Labor Law USA Essay Example

- Sonny’s Blues Essay Sample

- COVID 19 (Corona Virus) Essay Sample

- Why Do You Want To Be A Nurse Essay Example

- Family Planning Essay Sample

- Internet Boon or Bane Essay Example

- Does Access to Condoms Prevent Teen Pregnancy Essay Sample

- Child Abuse Essay Example

- Disadvantage of Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR) Essay Sample

- Essay Sample On Zika Virus

- Wonder Woman Essay Sample

- Teenage Suicide Essay Sample

- Primary Socialization Essay Sample In USA

- Role Of Physics In Daily Life Essay Sample

- Are Law Enforcement Cameras An Invasion of Privacy Essay Sample

- Why Guns Should Not Be Banned

- Neolithic Revolution Essay Sample

- Home Schooling Essay Sample

- Cosmetology Essay Sample

- Sale Promotion Techniques Sample Essay

- How Democratic Was Andrew Jackson Essay Sample

- Baby Boomers Essay Sample

- Veterans Day Essay Sample

- Why Did Japan Attack Pearl Harbor Essay Sample

- Component Of Criminal Justice System In USA Essay Sample

- Self Introduction Essay Example

- Divorce Argumentative Essay Sample

- Bullying Essay Sample

Get Free Assignment Quote

Enter Discount Code If You Have, Else Leave Blank

Texting While Driving Essay Examples

Why is texting while driving dangerous.

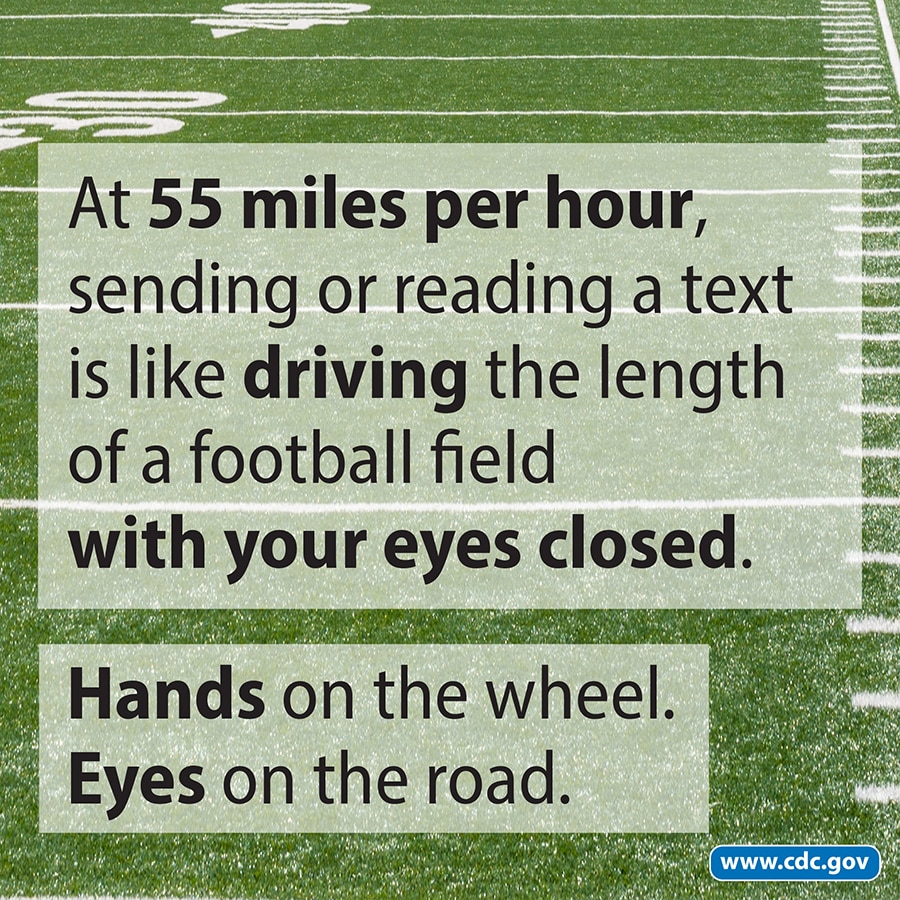

Put simply, texting and driving are dangerous because texting diverts your attention away from the road. Although many people argue that texting only takes your eyes off the road for a few seconds, what they don’t realize is that in that few seconds, something unexpected could happen. Additionally, if you’re traveling at high rates of speed, you can travel significant distances in just a few seconds. Those few seconds that you are on your phone could be used to hit the breaks or swerve out of the way of a quickly approaching article. If your eyes are on your phone instead of on the road, you lose valuable time that could have been used to mitigate an accident.

How do you Break the Habit of Texting While Driving?

One of the best ways to stop yourself from texting while driving is to create a habit that will keep your eyes on the road and your hands on the wheel. For many people who rely on their phones for so much, this may seem like a difficult task. However, if you think about it, there are several things that you do habitually when driving a car that you don’t even think about, such as putting on a seatbelt or locking your car after you park it. The key is to incorporate putting your phone away as part of those routines. In that way, you’re not so much breaking the habit of texting and driving, but instead, creating new habits that prevent you from using your phone while in the car.

Making a new habit can be challenging. The key is to stay consistent and continually remind yourself of your goal until it becomes second nature. Try attaching a sticky note to the wheel of your car to remind yourself to not text and drive. Another good trick is to make a pact with a friend to help keep each other accountable. It is important to stick with your habit, not give in to temptation and always keep in the back of your mind the benefits of staying focused on the road and not driving while distracted.

The most ideal habit you can build is to simply turn your phone off when you get in the car. That way there is never any sort of distraction when you’re in the car – any notifications, no browsing social media, and no distractions while you try to pick the next song to listen to. However, this might not always be an option when you need to use your GPS or if you use your phone for entertainment purposes while driving. Fortunately, there are other solutions. You can use an app while you drive (we make some suggestions for good apps below!) and simply make a habit of activating the app before you hit the road. If you often drive with others in the car, another good option is to hand your phone to another passenger to hold onto until you reach your destination. If instead you typically drive alone, you can always close up your phone in the glove compartment, your purse, in the center storage console under your armrest or in any other place where you cannot reach it. That way, you can have your phone connected to the vehicle for entertainment purposes but will avoid texting and driving.

Can you go to Jail for Texting While Driving?

In Pennsylvania, drivers are prohibited from driving and texting. If you are pulled over texting and driving, you will be issued a fine. However, if you are texting and driving and you cause an accident, there may be criminal consequences for those actions that could result in jail time. The more severe the accident, the more jail time you can face. For example, if you cause a fatality by texting and driving, you may face up to five years in jail.

How many People are Killed by Texting While Driving?

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that in 2017, over 3,000 people were killed in accidents caused by distracted driving. In Pennsylvania alone, a study estimated that in 2015, distracted driving caused nearly 15-thousand car crashes and at least 66 deaths.

Apps That Help to Prevent Texting While Driving

Nowadays, there are many apps available to drivers to deter them from texting while driving. Here are some of our favorites:

- Drive Safe & Save– Designed by State Farm Auto Insurance, this app tracks your driving habits every time you get behind the wheel. Not only does it track when you’re using your phone while in the car, but also identifies when you’re speeding, breaking too hard or accelerating too quickly. The app will also provide tips on how to improve your driving habits. If you’re a State Farm customer, you can send your driving data to them and receive discounts for good driving on your monthly insurance bill too!

- LifeSaver – This app was designed for insurance companies and large trucking fleet – but is available for families too! For parents who are concerned about their children texting and driving, the app blocks the child’s phone while driving and alerts the parents when they have safely arrived at their destination. The app works quietly in the background when you start driving to block mobile distractions but provides options to unlock for emergency situations. It also provides reports on how safely family members are driving and parents can also unlock a reward system to incentivize good driving habits.

- AT&T DriveMode– Similarly, this app turns on when it senses that the phone is moving more than 15 miles per hour. Once activated, the app silences all incoming notifications, and will automatically respond to the caller or texter with a text stating that the person they are attempting to contact is currently driving. Parents are also alerted when the app is turned off, so you can help ensure your child is always safe.

- DriveSafe.ly – This app has to be activated each time you get in the car. However, once it’s turned on, this app will read aloud each text message you receive. It will also automatically reply to the sender that you are currently driving.

Check your Smart Phone – Many smartphones have “Do Not Disturb” or Drive Mode settings that you can turn on when getting behind the wheel.

Considering the importance of this matter and increase awareness to the next generation, we had organized the “Texting and Driving Essay” contest on for students. We are very happy to find that we got many great articles which show our next generation is pretty aware of this matter. The following four Texting and Driving Essay essays are the best entries:

Texting and Driving Essay: Statistics on texting and using your phone while driving and ideas to break those habits

By Leticia Pérez Zamor

Every day in the United States around one out of ten people are killed by distracted drivers, and around 1500 are injured in some way in crashes by these irresponsible, distracted drivers. One of the most dangerous, distracting activities that many people do is texting while driving. It is extremely dangerous because people who do this are putting more attention in texting, and they take their eyes off the road while they are driving, which increases the chance that the driver can lose the control of the vehicle, and could cause a crash or even in a worst-case could kill other people. When a person is texting, she/he is thinking about other things besides concentrating on driving. This is very dangerous because it could make the driver lose control of the car and slow her/his brain’s reaction time in case of a potential accident.

The statistics are very sad because according to the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) in 2011, 3,331 people were killed in crashes involving a distracted driver, and 387,000 people were injured in motor vehicle crashes involving a distracted driver. Additionally, a recent study by the Virginia Tech Transportation Institute showed that drivers who are texting are twice as likely to crash, or almost crash, as those who are focused on the road. These statistics are reaching higher numbers because people are using their cell phones more and more, especially adolescents.

For this reason, it is very important that we find some ideas to break off this bad habit of texting while driving. I think that one of the easiest and best ways to break this habit is simply to turn off your phone. In this case, the driver wouldn’t be distracted by the ringing or buzzing of the phone, and it wouldn’t tempt the driver to text while driving. Another way to break this habit is to download some of the new applications that can disable cell phones while people are driving. Also, there are other applications that automatically send a text to whoever is texting the driver to tell that person that she/he is driving and that the text will be answered later. There are a great variety of applications to choose I think that we can use these to help us with the problem of texting while we are driving. Additionally, if a driver is waiting for an important call or text and has company in the car, the phone can be given to a passenger to check it out. Also, there are some programs that are helping to raise awareness about the dangers of distracted driving and to keep it from occurring. In these anti-texting programs, people can drive in a simulated situation, where they are driving but also texting, and can see how many accidents are caused by this problem.

Something very important is that many of the states have started to pass some laws that order drivers to stop texting while driving. However, we need to be sincere: none of these laws will be effective if we as a society don’t understand that texting while driving could have terrible consequences, not only for us as drivers but also for other innocent people. I don’t think that answering texts is more important than the lives of other people; texting can wait until drivers arrive at their destination.

The Dangers of Texting While Driving Essay

By LoryYau, St. Johns University

With the advanced technology in today’s world, people are very connected to each other and are constantly on their phone texting friends, going on social media, or using the phone to pass time. However, this also includes texting back a friend while driving. As simple as it might seems, texting and driving is very dangerous and should be taken seriously. In fact, in 2011, at least 23% of auto collisions involved cell phones. That’s about 1.3 million crashes! Not only that but texting while driving is actually more dangerous than driving while being drunk or high on marijuana. Every year almost a million people in the United States get into accidents, the majority: teens. Unfortunately, the number just keeps increasing.

Though texting and driving caused many injuries and deaths, there are still people who don’t think it’s a problem and are confident that they can use their phone and drive simultaneously. However, 34% of teens aged sixteen to seventeen spend about 10% of their driving time outside of their lane. This affects other people who are driving and can cause the deaths of innocent lives. In a 2012 Cell Phone and Driving Statistic, it is reported that 3,328 people were killed and 421,000 people were injured due to distracted drivers. Furthermore, it is said that talking or listening on the phone increases the risk of crashing by 1.3 times while reaching for a device is 1.4. Dialing is 2.8 times more risk of crashing while texting is 23 more times. Additionally, talking on a cell phone and driving at the same time can make the driver’s reaction time to be as slow as that of a seventy-year-old.

To break these habits, people can either turn off their phone or put it on silent before driving. This will force them to concentrate on the road only. But if this method doesn’t work on some people, you can use S voice or Seri to command your phone to read out your messages or to reply back. This will allow your eyes to focus on the road instead of your phone. No more reaching for your phone to text “Lol” or “Lmao” and endangering your own life and many others. Though you are still talking while driving, it still decreases your chance of crashing. An app in smartphones that works similarly to the method I described before is called DriveSafe.ly. Basically, it reads your text messages and emails out loud and has a customizable auto-responder. A few other apps that help prevent texting are called Safely Go and TXT ME L8R. Both apps work by either blocking the phone’s ability to text, receive and use apps or locking the phone. Then both phones automatically send a message to inform your friends or family that you are driving. For parents, you can give your phones to your kids while you’re driving. You won’t be able to get them back when they’re too busy playing Angry Bird or Cut the Rope.

To stop people from texting and driving, one of the major phone companies, AT&T, address this problem by creating AT&T’s It Can Wait to text and driving campaign to spread awareness. Many stories and documentaries are also posted online to support this campaign. You can also join millions of others who have signed the pledge to never text and drive and to instead take action to educate others about the dangers of it. If you still believe you can get home safely by texting and driving, AT&T’s simulator will prove you wrong. It gives you a real-life experience of texting and driving. With this game, you’ll only find out that it’s not as easy as it sounds. Before you look at a text, remember that it is not worth dying for.

The Issue of Texting While Driving Essay

By Justin Van Nuil

It seems that everyone has a cell phone, and they cannot be separated from it. Cell phones have made a huge impact in the world, both good and bad. Most of the bad come when people, especially teens, decide to use the phone when behind the wheel of a vehicle. There are some huge statistics against texting and talking on the phone while driving, and people are trying to bring awareness to this expanding problem across the United States.

Staggering statistics are out there for everyone to see, yet we go about our lives ignoring the signs and warning against using our cell phones while driving. Textinganddrivingsafety.com tells us that texting while driving increases the probability of getting in a crash twenty-three times the normal amount, and thirteen percent of the young adults, eighteen to twenty, have admitted to talking or texting before the course of the accident. This is due to the time our eyes are off the road, and our mind’s capacity to do only one task at a time. Just taking our eyes off the road for five seconds, while the car is traveling at fifty-five miles per hour, is the same as traveling a football field without noticing what is going on around us. Seeing the danger in this is very evident, especially around intersections. Taking eyes off the road through an intersection is probably the highest risk, the light could be changing causing the car in front to stop, or worse, traveling through the red light or a stop sign into flowing traffic.

Texting is a major factor when it comes to crashes and creating a hazardous situation, so preventing the usage of cell phones while driving would be a large step in limiting the number of crashes that happen in the United States. There are multiple associations that are already trying to prevent cell phone usage. Associations such as the NHTSA, the Nation Highway Traffic Safety Association, which is an organization dedicated fully to tips and facts and videos showing how dangerous it can be to use your cell phone. There are also Facebook and Twitter pages, and blogs. In addition, the driving course in Michigan has a section in the lesson on the hazards of using cell phones while driving.

These are just programs that are helping to prevent texting while driving. Easy and simple ways that everyone can do as they enter the car. Firstly, by putting the phone in the glovebox, you eliminate the temptation to reach for it and use it while your driving. If you decide not to use that method, and you have a passenger, just give the phone to them, they can rely on the information to you if it is that important. Just keeping the phone out of reach, in general, will help prevent the usage of the device.

Not only are these ways are widespread and easily accomplished, but there should also be a restriction in general for usage while driving. I know multiple states have issued laws against texting, and in some states absolute usage of the cell phone while in the driver’s seat. Although, the overall effects may not be seen in the number of accidents prevented due to these laws, having a larger discipline for doing such activities should help in dropping the number of people on their devices.

Preventing the usage of these everyday devices is very simple, yet rather difficult, and will save lives if it works out. Accidents are deadly to many people, so creating an environment for everyone is better in the long run. As a young adult, I plan to use some of these ideas and promote these websites and encourage others around me to do the same.

Why is Texting and Driving Dangerous?

By Haley Muhammad

It has become such an issue that every time we turn on the TV all we see is that same commercial running about that girl who died because she wanted to text her friend back. Or that now in every major TV show someone always gets in a car accident because they want to text someone that they love them. It’s clear that no one has the decency to pull over to text someone back or even call them to say I will text you later because I’m driving. It’s a rising epidemic that’s destroying the generation of teenagers. I remember when technology was something beautiful because of how helpful it is but, now its become a hazard to the generation alone. Statistics have shown that “ Texting while driving has become a greater hazard than drinking while driving among teenagers who openly acknowledge sending and reading text messages while behind the wheel of a moving vehicle,” stated by Delthia Ricks from Newsday newspaper.

Ever since the emergence of cell phones, this generation has become heavily dependent on it for every minute of every day. Cell phones and texting were created ultimately to provide communication but it has now become so much more than that. Statistics also show that “Seventy-one percent of young people say they have sent a text while driving. As a result, thousands of people die every year in crashes related to distracted driving,” (Distraction.gov). Texting while driving has become a heavy habit for most teens and adults as well but regardless of the commercials and shows and statistics that show the results of texting while driving most people cannot kick the habit. Other statistics include, “Individuals who drive while sending or reading text messages are 23 percent more likely to be involved in a car crash than other drivers. A crash typically happens within an average of three seconds after a driver is distracted,” (donttextdrive.com). Overall all these statistics are saying the same thing, is that one text can wreck all.

So many lives are taken or altered because of the simple decision to send or reply to one text message. If precautions are heavily enforced before adults and teens especially enter the car, then maybe this epidemic can become obsolete. Fines are enforced but how well is the question? Phones are the biggest distraction when you enter a car, this doesn’t completely forget about alcohol or trying to change the radio station but technology has become so advanced that we have voice text and on a star. If the message is that important phones should become voice-activated and only respond to your voice so we can still pay attention to the road and send out a text without removing our hands from the wheel. Technology has also graced us with Bluetooth if you need to stay in communication just use Bluetooth and make a phone call instead which is completely easier than sending a text anyway because it’s faster and you can get responses much quicker than you could with a text message. Reality is one text or call could wreck it all.

Stuart A. Carpey, who has been practicing as an attorney since 1987, focuses his practice on complex civil litigation which includes representing injured individuals in a vast array of personal injury cases.

- Original Contribution

- Open access

- Published: 01 March 2016

Texting while driving: the development and validation of the distracted driving survey and risk score among young adults

- Regan W. Bergmark ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3249-4343 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Emily Gliklich 1 ,

- Rong Guo 2 , 3 &

- Richard E. Gliklich 1 , 2 , 3

Injury Epidemiology volume 3 , Article number: 7 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

29 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Texting while driving and other cell-phone reading and writing activities are high-risk activities associated with motor vehicle collisions and mortality. This paper describes the development and preliminary evaluation of the Distracted Driving Survey (DDS) and score.

Survey questions were developed by a research team using semi-structured interviews, pilot-tested, and evaluated in young drivers for validity and reliability. Questions focused on texting while driving and use of email, social media, and maps on cellular phones with specific questions about the driving speeds at which these activities are performed.

In 228 drivers 18–24 years old, the DDS showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93) and correlations with reported 12-month crash rates. The score is reported on a 0–44 scale with 44 being highest risk behaviors. For every 1 unit increase of the DDS score, the odds of reporting a car crash increases 7 %. The survey can be completed in two minutes, or less than five minutes if demographic and background information is included. Text messaging was common; 59.2 and 71.5 % of respondents said they wrote and read text messages, respectively, while driving in the last 30 days.

The DDS is an 11-item scale that measures cell phone-related distracted driving risk and includes reading/viewing and writing subscores. The scale demonstrated strong validity and reliability in drivers age 24 and younger. The DDS may be useful for measuring rates of cell-phone related distracted driving and for evaluating public health interventions focused on reducing such behaviors.

Texting and other cell phone use while driving has emerged as a major contribution to teenage and young adult injury and death in motor vehicle collisions over the past several years (Bingham 2014 ; Wilson and Stimpson 2010 ). Young adults have been found to have higher rates of texting and driving than older drivers (Braitman and McCartt 2010 ; Hoff et al. 2013 ). Motor vehicle collisions are the top cause of death for teens, responsible for 35 % of all deaths of teens 12–19 years old, with high rates of distraction contributing significantly to this percentage (Minino 2010 ). In 2012, more than 3300 people were killed and 421,000 injured in distraction-related crashes in the US, with the worst levels of distraction in the youngest drivers (US Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 2014 ).

While distracted driving includes any activity that takes eyes or attention away from driving, there has been particular and intense interest on texting and other smartphone-associated distraction as smartphones have become widely available over the past ten years. Multiple studies have examined driving performance while texting or completing other secondary tasks (Yannis et al. 2014 ; Owens et al. 2011 ; Olson et al. 2009 ; Narad et al. 2013 ; McKeever et al. 2013 ; Drews et al. 2009 ; Hickman and Hanowski 2012 ; Leung et al. 2012 ; Long et al. 2012 ). Uniformly, distraction from cell phone use, including texting, dialing or other behaviors, is associated with poorer driving performance (Yannis et al. 2014 ; McKeever et al. 2013 ; Bendak 2014 ; Hosking et al. 2009 ; Irwin et al. 2014 ; Mouloua et al. 2012 ; Rudin-Brown et al. 2013 ; Stavrinos et al. 2013 ). A 2014 meta-analysis of experimental studies found profound effects of texting while driving with poor responsiveness and vehicle control, and higher numbers of crashes (Caird et al. 2014 ). A rigorous case–control study found that among novice drivers, sending and receiving texts was associated with significantly increased risk of a crash or near-crash (O.R. 3.9) (Klauer et al. 2014 ). In commercial vehicles, texting on a cell phone was associated with a much higher risk of a crash or other safety-critical event, such as near-collision or unintentional lane deviation (OR 23.2) (Olson et al. 2009 ). Motor vehicle crash-related death and injury have also been strongly associated with texting (Pakula et al. 2013 ; Issar et al. 2013 ).

Although the dangers of texting and driving are well-established, a focused brief survey on driver-reported texting behavior does not yet exist. Multiple national surveys which include texting while driving as part of a more extensive survey on distracted driving or youth health have found that young drivers have high rates of texting while driving, often in spite of high levels of perceived risk (Hoff et al. 2013 ; Buchanan et al. 2013 ; Cazzulino et al. 2014 ; O’Brien et al. 2010 ; Atchley et al. 2011 ; Harrison 2011 ; Nelson et al. 2009 ). The surveys confirm that young adults are at high risk for distracted driving; in one, 81 % of 348 college students stated that they would respond to an incoming text while driving, and 92 % read texts while driving (Atchley et al. 2011 ). Among several large survey based studies, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration reported from a 2012 survey that nearly half (49 %) of 21–24 year old drivers had ever sent a text message or email while driving (Tison et al. 2011 -12), and even more alarming, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s National Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that nearly as many high school students who drove reported texting in just the past 30 days (41.4 %) ( Kann et al. 2014 ). The problem is not confined to novice drivers. Among US adults ages 18 to 64 years 31 % report reading or sending text messages or emails while driving in prior last 30 days ( Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2013 ).

Given the magnitude of the problem, a very brief questionnaire focused on texting and driving for evaluation of public health measures such as anti-texting while driving laws, cell phone applications and public health campaigns would be useful. The use of self-reported validated surveys is an increasingly common approach to understanding health issues as well as their response to intervention (Guyatt et al. 1993 ; Tarlov et al. 1989 ; Stewart and Ware 1992 ). Current surveys are driving-specific but lengthy and potentially prohibitive for widespread dissemination (Tison et al. 2011 -12, McNally and Bradley 2014 ; Scott-Parker et al. 2012 ; Scott-Parker and Proffitt 2015 ), do not include texting as a survey domain within the realm of distraction (Martinussen, et al, 2013 ), are general health surveys without sufficient information on texting and driving ( Kann et al. 2014 ), or have not been designed or validated to reliably measure and evaluate individual crash risk ( Kann et al. 2014 ). For example, a new survey of reckless driving behavior includes information on multiple driving-related domains of behavior, but administration takes 35 min and the survey does not focus on cell phones (McNally and Bradley 2014 ). Another survey of distraction in youth is similarly comprehensive without a focus on phone use (Scott-Parker et al. 2012 ; Scott-Parker and Proffitt 2015 ). The goal of shorter surveys for evaluation of distracted driving has been well documented and development of the mini Driver Behavior Questionnaire (Mini-DBQ) is an example, although it does not address cell phone related distracted driving (Martinussen et al. 2013 ). However, many interventions target cell phone use specifically rather than distraction broadly. In addition, most surveys do not delve into the specific timing of texting while driving that allows a more precise estimate of the behavior’s prevalence.

The purpose of this study was to develop a reliable self-reported survey for assessing levels of cell phone related distracted driving associated with viewing and typing activities and to validate it in a higher risk population of drivers age 24 years or younger.

Study design and oversight