An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychiatry

Mental Health Prevention and Promotion—A Narrative Review

Associated data.

Extant literature has established the effectiveness of various mental health promotion and prevention strategies, including novel interventions. However, comprehensive literature encompassing all these aspects and challenges and opportunities in implementing such interventions in different settings is still lacking. Therefore, in the current review, we aimed to synthesize existing literature on various mental health promotion and prevention interventions and their effectiveness. Additionally, we intend to highlight various novel approaches to mental health care and their implications across different resource settings and provide future directions. The review highlights the (1) concept of preventive psychiatry, including various mental health promotions and prevention approaches, (2) current level of evidence of various mental health preventive interventions, including the novel interventions, and (3) challenges and opportunities in implementing concepts of preventive psychiatry and related interventions across the settings. Although preventive psychiatry is a well-known concept, it is a poorly utilized public health strategy to address the population's mental health needs. It has wide-ranging implications for the wellbeing of society and individuals, including those suffering from chronic medical problems. The researchers and policymakers are increasingly realizing the potential of preventive psychiatry; however, its implementation is poor in low-resource settings. Utilizing novel interventions, such as mobile-and-internet-based interventions and blended and stepped-care models of care can address the vast mental health need of the population. Additionally, it provides mental health services in a less-stigmatizing and easily accessible, and flexible manner. Furthermore, employing decision support systems/algorithms for patient management and personalized care and utilizing the digital platform for the non-specialists' training in mental health care are valuable additions to the existing mental health support system. However, more research concerning this is required worldwide, especially in the low-and-middle-income countries.

Introduction

Mental disorder has been recognized as a significant public health concern and one of the leading causes of disability worldwide, particularly with the loss of productive years of the sufferer's life ( 1 ). The Global Burden of Disease report (2019) highlights an increase, from around 80 million to over 125 million, in the worldwide number of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) attributable to mental disorders. With this surge, mental disorders have moved into the top 10 significant causes of DALYs worldwide over the last three decades ( 2 ). Furthermore, this data does not include substance use disorders (SUDs), which, if included, would increase the estimated burden manifolds. Moreover, if the caregiver-related burden is accounted for, this figure would be much higher. Individual, social, cultural, political, and economic issues are critical mental wellbeing determinants. An increasing burden of mental diseases can, in turn, contribute to deterioration in physical health and poorer social and economic growth of a country ( 3 ). Mental health expenditure is roughly 3–4% of their Gross Domestic Products (GDPs) in developed regions of the world; however, the figure is abysmally low in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) ( 4 ). Untreated mental health and behavioral problems in childhood and adolescents, in particular, have profound long-term social and economic adverse consequences, including increased contact with the criminal justice system, lower employment rate and lesser wages among those employed, and interpersonal difficulties ( 5 – 8 ).

Need for Mental Health (MH) Prevention

Longitudinal studies suggest that individuals with a lower level of positive wellbeing are more likely to acquire mental illness ( 9 ). Conversely, factors that promote positive wellbeing and resilience among individuals are critical in preventing mental illnesses and better outcomes among those with mental illness ( 10 , 11 ). For example, in patients with depressive disorders, higher premorbid resilience is associated with earlier responses ( 12 ). On the contrary, patients with bipolar affective- and recurrent depressive disorders who have a lower premorbid quality of life are at higher risk of relapses ( 13 ).

Recently there has been an increased emphasis on the need to promote wellbeing and positive mental health in preventing the development of mental disorders, for poor mental health has significant social and economic implications ( 14 – 16 ). Research also suggests that mental health promotion and preventative measures are cost-effective in preventing or reducing mental illness-related morbidity, both at the society and individual level ( 17 ).

Although the World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing and not merely an absence of disease or infirmity,” there has been little effort at the global level or stagnation in implementing effective mental health services ( 18 ). Moreover, when it comes to the research on mental health (vis-a-viz physical health), promotive and preventive mental health aspects have received less attention vis-a-viz physical health. Instead, greater emphasis has been given to the illness aspect, such as research on psychopathology, mental disorders, and treatment ( 19 , 20 ). Often, physicians and psychiatrists are unfamiliar with various concepts, approaches, and interventions directed toward mental health promotion and prevention ( 11 , 21 ).

Prevention and promotion of mental health are essential, notably in reducing the growing magnitude of mental illnesses. However, while health promotion and disease prevention are universally regarded concepts in public health, their strategic application for mental health promotion and prevention are often elusive. Furthermore, given the evidence of substantial links between psychological and physical health, the non-incorporation of preventive mental health services is deplorable and has serious ramifications. Therefore, policymakers and health practitioners must be sensitized about linkages between mental- and physical health to effectively implement various mental health promotive and preventive interventions, including in individuals with chronic physical illnesses ( 18 ).

The magnitude of the mental health problems can be gauged by the fact that about 10–20% of young individuals worldwide experience depression ( 22 ). As described above, poor mental health during childhood is associated with adverse health (e.g., substance use and abuse), social (e.g., delinquency), academic (e.g., school failure), and economic (high risk of poverty) adverse outcomes in adulthood ( 23 ). Childhood and adolescence are critical periods for setting the ground for physical growth and mental wellbeing ( 22 ). Therefore, interventions promoting positive psychology empower youth with the life skills and opportunities to reach their full potential and cope with life's challenges. Comprehensive mental health interventions involving families, schools, and communities have resulted in positive physical and psychological health outcomes. However, the data is limited to high-income countries (HICs) ( 24 – 28 ).

In contrast, in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) that bear the greatest brunt of mental health problems, including massive, coupled with a high treatment gap, such interventions remained neglected in public health ( 29 , 30 ). This issue warrants prompt attention, particularly when global development strategies such as Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) realize the importance of mental health ( 31 ). Furthermore, studies have consistently reported that people with socioeconomic disadvantages are at a higher risk of mental illness and associated adverse outcomes; partly, it is attributed to the inequitable distribution of mental health services ( 32 – 35 ).

Scope of Mental Health Promotion and Prevention in the Current Situation

Literature provides considerable evidence on the effectiveness of various preventive mental health interventions targeting risk and protective factors for various mental illnesses ( 18 , 36 – 42 ). There is also modest evidence of the effectiveness of programs focusing on early identification and intervention for severe mental diseases (e.g., schizophrenia and psychotic illness, and bipolar affective disorders) as well as common mental disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression, stress-related disorders) ( 43 – 46 ). These preventive measures have also been evaluated for their cost-effectiveness with promising findings. In addition, novel interventions such as digital-based interventions and novel therapies (e.g., adventure therapy, community pharmacy program, and Home-based Nurse family partnership program) to address the mental health problems have yielded positive results. Likewise, data is emerging from LMICs, showing at least moderate evidence of mental health promotion intervention effectiveness. However, most of the available literature and intervention is restricted mainly to the HICs ( 47 ). Therefore, their replicability in LMICs needs to be established and, also, there is a need to develop locally suited interventions.

Fortunately, there has been considerable progress in preventive psychiatry over recent decades, including research on it. In the light of these advances, there is an accelerated interest among researchers, clinicians, governments, and policymakers to harness the potentialities of the preventive strategies to improve the availability, accessibility, and utility of such services for the community.

The Concept of Preventive Psychiatry

Origins of preventive psychiatry.

The history of preventive psychiatry can be traced back to the early 1900's with the foundation of the national mental health association (erstwhile mental health association), the committee on mental hygiene in New York, and the mental health hygiene movement ( 48 ). The latter emphasized the need for physicians to develop empathy and recognize and treat mental illness early, leading to greater awareness about mental health prevention ( 49 ). Despite that, preventive psychiatry remained an alien concept for many, including mental health professionals, particularly when the etiology of most psychiatric disorders was either unknown or poorly understood. However, recent advances in our understanding of the phenomena underlying psychiatric disorders and availability of the neuroimaging and electrophysiological techniques concerning mental illness and its prognosis has again brought the preventive psychiatry in the forefront ( 1 ).

Levels of Prevention

The literal meaning of “prevention” is “the act of preventing something from happening” ( 50 ); the entity being prevented can range from the risk factors of the development of the illness, the onset of illness, or the recurrence of the illness or associated disability. The concept of prevention emerged primarily from infectious diseases; measures like mass vaccination and sanitation promotion have helped prevent the development of the diseases and subsequent fatalities. The original preventive model proposed by the Commission on Chronic Illness in 1957 included primary, secondary, and tertiary preventions ( 48 ).

The Concept of Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Prevention

The stages of prevention target distinct aspects of the illness's natural course; the primary prevention acts at the stage of pre-pathogenesis, that is, when the disease is yet to occur, whereas the secondary and tertiary prevention target the phase after the onset of the disease ( 51 ). Primary prevention includes health promotion and specific protection, while secondary and tertairy preventions include early diagnosis and treatment and measures to decrease disability and rehabilitation, respectively ( 51 ) ( Figure 1 ).

The concept of primary and secondary prevention [adopted from prevention: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary by Bauman et al. ( 51 )].

The primary prevention targets those individuals vulnerable to developing mental disorders and their consequences because of their bio-psycho-social attributes. Therefore, it can be viewed as an intervention to prevent an illness, thereby preventing mental health morbidity and potential social and economic adversities. The preventive strategies under it usually target the general population or individuals at risk. Secondary and tertiary prevention targets those who have already developed the illness, aiming to reduce impairment and morbidity as soon as possible. However, these measures usually occur in a person who has already developed an illness, therefore facing related suffering, hence may not always be successful in curing or managing the illness. Thus, secondary and tertiary prevention measures target the already exposed or diagnosed individuals.

The Concept of Universal, Selective, and Indicated Prevention

The classification of health prevention based on primary/secondary/tertiary prevention is limited in being highly centered on the etiology of the illness; it does not consider the interaction between underlying etiology and risk factors of an illness. Gordon proposed another model of prevention that focuses on the degree of risk an individual is at, and accordingly, the intensity of intervention is determined. He has classified it into universal, selective, and indicated prevention. A universal preventive strategy targets the whole population irrespective of individual risk (e.g., maintaining healthy, psychoactive substance-free lifestyles); selective prevention is targeted to those at a higher risk than the general population (socio-economically disadvantaged population, e.g., migrants, a victim of a disaster, destitute, etc.). The indicated prevention aims at those who have established risk factors and are at a high risk of getting the disease (e.g., family history of psychiatric illness, history of substance use, certain personality types, etc.). Nevertheless, on the other hand, these two classifications (the primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention; and universal, selective, and indicated prevention) have been intended for and are more appropriate for physical illnesses with a clear etiology or risk factors ( 48 ).

In 1994, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders proposed a new paradigm that classified primary preventive measures for mental illnesses into three categories. These are indicated, selected, and universal preventive interventions (refer Figure 2 ). According to this paradigm, primary prevention was limited to interventions done before the onset of the mental illness ( 48 ). In contrast, secondary and tertiary prevention encompasses treatment and maintenance measures ( Figure 2 ).

The interventions for mental illness as classified by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders [adopted from Mrazek and Haggerty ( 48 )].

Although the boundaries between prevention and treatment are often more overlapping than being exclusive, the new paradigm can be used to avoid confusion stemming from the common belief that prevention can take place at all parts of mental health management ( 48 ). The onset of mental illnesses can be prevented by risk reduction interventions, which can involve reducing risk factors in an individual and strengthening protective elements in them. It aims to target modifiable factors, both risk, and protective factors, associated with the development of the illness through various general and specific interventions. These interventions can work across the lifespan. The benefits are not restricted to reduction or delay in the onset of illness but also in terms of severity or duration of illness ( 48 ).On the spectrum of mental health interventions, universal preventive interventions are directed at the whole population without identifiable risk factors. The interventions are beneficial for the general population or sub-groups. Prenatal care and childhood vaccination are examples of preventative measures that have benefited both physical and mental health. Selective preventive mental health interventions are directed at people or a subgroup with a significantly higher risk of developing mental disorders than the general population. Risk groups are those who, because of their vulnerabilities, are at higher risk of developing mental illnesses, e.g., infants with low-birth-weight (LBW), vulnerable children with learning difficulties or victims of maltreatment, elderlies, etc. Specific interventions are home visits and new-born day care facilities for LBW infants, preschool programs for all children living in resource-deprived areas, support groups for vulnerable elderlies, etc. Indicated preventive interventions focus on high-risk individuals who have developed minor but observable signs or symptoms of mental disorder or genetic risk factors for mental illness. However, they have not fulfilled the criteria of a diagnosable mental disorder. For instance, the parent-child interaction training program is an indicated prevention strategy that offers support to children whose parents have recognized them as having behavioral difficulties.

The overall objective of mental health promotion and prevention is to reduce the incidence of new cases, additionally delaying the emergence of mental illness. However, promotion and prevention in mental health complement each other rather than being mutually exclusive. Moreover, combining these two within the overall public health framework reduces stigma, increases cost-effectiveness, and provides multiple positive outcomes ( 18 ).

How Prevention in Psychiatry Differs From Other Medical Disorders

Compared to physical illnesses, diagnosing a mental illness is more challenging, particularly when there is still a lack of objective assessment methods, including diagnostic tools and biomarkers. Therefore, the diagnosis of mental disorders is heavily influenced by the assessors' theoretical perspectives and subjectivity. Moreover, mental illnesses can still be considered despite an individual not fulfilling the proper diagnostic criteria led down in classificatory systems, but there is detectable dysfunction. Furthermore, the precise timing of disorder initiation or transition from subclinical to clinical condition is often uncertain and inconclusive ( 48 ). Therefore, prevention strategies are well-delineated and clear in the case of physical disorders while it's still less prevalent in mental health parlance.

Terms, Definitions, and Concepts

The terms mental health, health promotion, and prevention have been differently defined and interpreted. It is further complicated by overlapping boundaries of the concept of promotion and prevention. Some commonly used terms in mental health prevention have been tabulated ( Table 1 ) ( 18 ).

Commonly used terms in mental health prevention.

Mental Health Promotion and Protection

The term “mental health promotion” also has definitional challenges as it signifies different things to different individuals. For some, it means the treatment of mental illness; for others, it means preventing the occurrence of mental illness; while for others, it means increasing the ability to manage frustration, stress, and difficulties by strengthening one's resilience and coping abilities ( 54 ). It involves promoting the value of mental health and improving the coping capacities of individuals rather than amelioration of symptoms and deficits.

Mental health promotion is a broad concept that encompasses the entire population, and it advocates for a strengths-based approach and tries to address the broader determinants of mental health. The objective is to eliminate health inequalities via empowerment, collaboration, and participation. There is mounting evidence that mental health promotion interventions improve mental health, lower the risk of developing mental disorders ( 48 , 55 , 56 ) and have socioeconomic benefits ( 24 ). In addition, it strives to increase an individual's capacity for psychosocial wellbeing and adversity adaptation ( 11 ).

However, the concepts of mental health promotion, protection, and prevention are intrinsically linked and intertwined. Furthermore, most mental diseases result from complex interaction risk and protective factors instead of a definite etiology. Facilitating the development and timely attainment of developmental milestones across an individual's lifespan is critical for positive mental health ( 57 ). Although mental health promotion and prevention are essential aspects of public health with wide-ranging benefits, their feasibility and implementation are marred by financial and resource constraints. The lack of cost-effectiveness studies, particularly from the LMICs, further restricts its full realization ( 47 , 58 , 59 ).

Despite the significance of the topic and a considerable amount of literature on it, a comprehensive review is still lacking that would cover the concept of mental health promotion and prevention and simultaneously discusses various interventions, including the novel techniques delivered across the lifespan, in different settings, and level of prevention. Therefore, this review aims to analyze the existing literature on various mental health promotion and prevention-based interventions and their effectiveness. Furthermore, its attempts to highlight the implications of such intervention in low-resource settings and provides future directions. Such literature would add to the existing literature on mental health promotion and prevention research and provide key insights into the effectiveness of such interventions and their feasibility and replicability in various settings.

Methodology

For the current review, key terms like “mental health promotion,” OR “protection,” OR “prevention,” OR “mitigation” were used to search relevant literature on Google Scholar, PubMed, and Cochrane library databases, considering a time period between 2000 to 2019 ( Supplementary Material 1 ). However, we have restricted our search till 2019 for non-original articles (reviews, commentaries, viewpoints, etc.), assuming that it would also cover most of the original articles published until then. Additionally, we included original papers from the last 5 years (2016–2021) so that they do not get missed out if not covered under any published review. The time restriction of 2019 for non-original articles was applied to exclude papers published during the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic as the latter was a significant event, bringing about substantial change and hence, it warranted a different approach to cater to the MH needs of the population, including MH prevention measures. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the flooding of novel interventions for mental health prevention and promotion, specifically targeting the pandemic and its consequences, which, if included, could have biased the findings of the current review on various MH promotion and prevention interventions.

A time frame of about 20 years was taken to see the effectiveness of various MH promotion and protection interventions as it would take substantial time to be appreciated in real-world situations. Therefore, the current paper has put greater reliance on the review articles published during the last two decades, assuming that it would cover most of the original articles published until then.

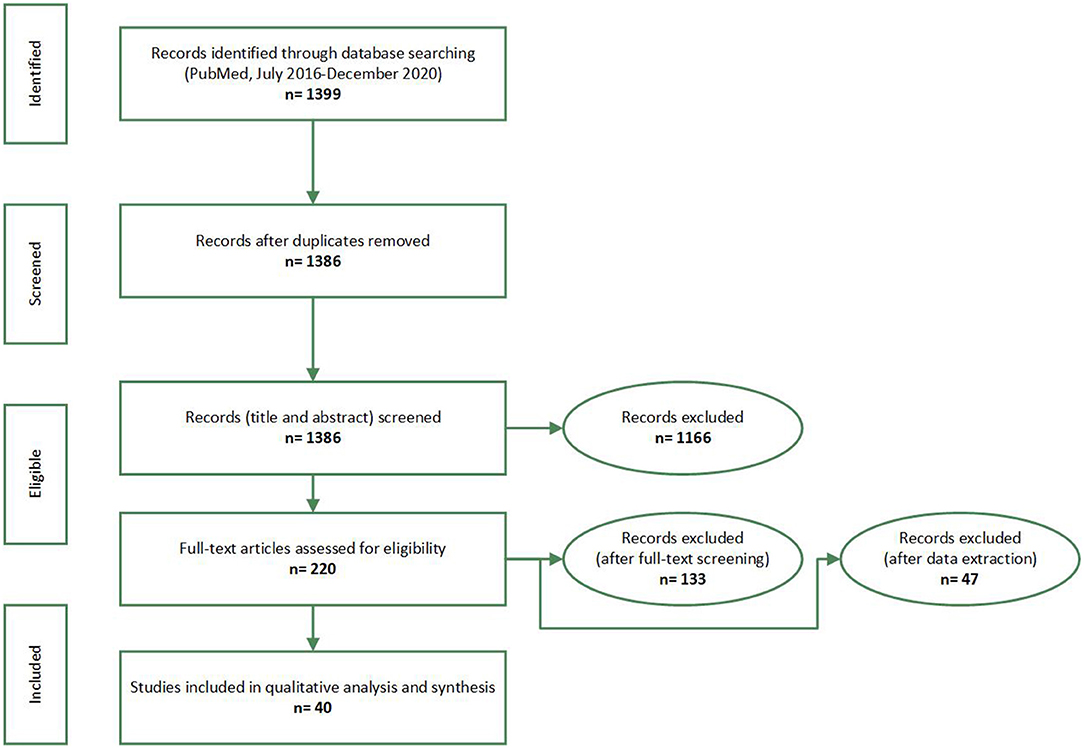

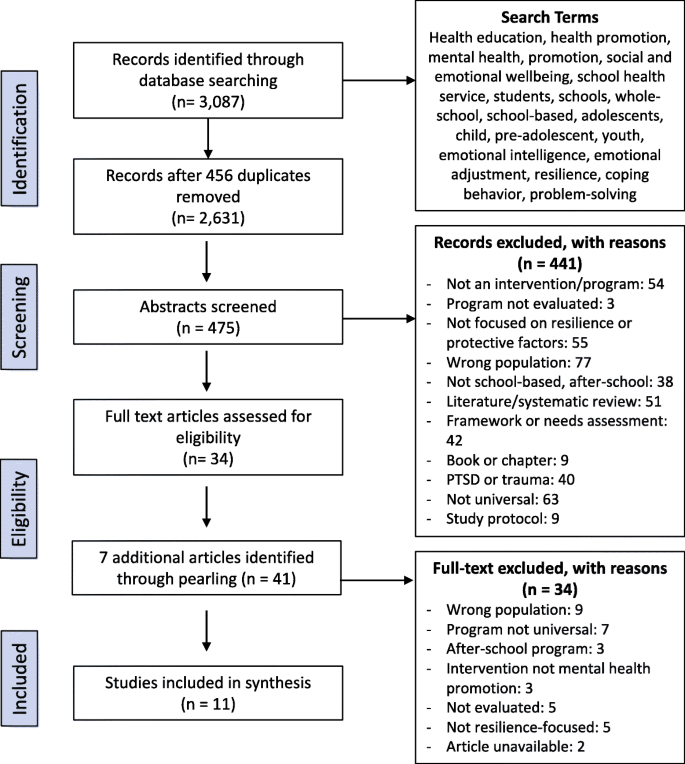

The above search yielded 320 records: 225 articles from Google scholar, 59 articles from PubMed, and 36 articles from the Cochrane database flow-diagram of records screening. All the records were title/abstract screened by all the authors to establish the suitability of those records for the current review; a bibliographic- and gray literature search was also performed. In case of any doubts or differences in opinion, it was resolved by mutual discussion. Only those articles directly related to mental health promotion, primary prevention, and related interventions were included in the current review. In contrast, records that discussed any specific conditions/disorders (post-traumatic stress disorders, suicide, depression, etc.), specific intervention (e.g., specific suicide prevention intervention) that too for a particular population (e.g., disaster victims) lack generalizability in terms of mental health promotion or prevention, those not available in the English language, and whose full text was unavailable were excluded. The findings of the review were described narratively.

Interventions for Mental Health Promotion and Prevention and Their Evidence

Various interventions have been designed for mental health promotion and prevention. They are delivered and evaluated across the regions (high-income countries to low-resource settings, including disaster-affiliated regions of the world), settings (community-based, school-based, family-based, or individualized); utilized different psychological constructs and therapies (cognitive behavioral therapy, behavioral interventions, coping skills training, interpersonal therapies, general health education, etc.); and delivered by different professionals/facilitators (school-teachers, mental health professionals or paraprofessionals, peers, etc.). The details of the studies, interventions used, and outcomes have been provided in Supplementary Table 1 . Below we provide the synthesized findings of the available research.

The majority of the available studies were quantitative and experimental. Randomized controlled trials comprised a sizeable proportion of the studies; others were quasi-experimental studies and, a few, qualitative studies. The studies primarily focussed on school students or the younger population, while others were explicitly concerned with the mental health of young females ( 60 ). Newer data is emerging on mental health promotion and prevention interventions for elderlies (e.g., dementia) ( 61 ). The majority of the research had taken a broad approach to mental health promotion ( 62 ). However, some studies have focused on universal prevention ( 63 , 64 ) or selective prevention ( 65 – 68 ). For instance, the Resourceful Adolescent Program (RAPA) was implemented across the schools and has utilized cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal therapies and reported a significant improvement in depressive symptoms. Some of the interventions were directed at enhancing an individual's characteristics like resilience, behavior regulation, and coping skills (ZIPPY's Friends) ( 69 ), while others have focused on the promotion of social and emotional competencies among the school children and attempted to reduce the gap in such competencies across the socio-economic classes (“Up” program) ( 70 ) or utilized expressive abilities of the war-affected children (Writing for Recover (WfR) intervention) ( 71 ) to bring about an improvement in their psychological problems (a type of selective prevention) ( 62 ) or harnessing the potential of Art, in the community-based intervention, to improve self-efficacy, thus preventing mental disorders (MAD about Art program) ( 72 ). Yet, others have focused on strengthening family ( 60 , 73 ), community relationships ( 62 ), and targeting modifiable risk factors across the life course to prevent dementia among the elderlies and also to support the carers of such patients ( 61 ).

Furthermore, more of the studies were conducted and evaluated in the developed parts of the world, while emerging economies, as anticipated, far lagged in such interventions or related research. The interventions that are specifically adapted for local resources, such as school-based programs involving paraprofessionals and teachers in the delivery of mental health interventions, were shown to be more effective ( 62 , 74 ). Likewise, tailored approaches for low-resource settings such as LMICs may also be more effective ( 63 ). Some of these studies also highlight the beneficial role of a multi-dimensional approach ( 68 , 75 ) and interventions targeting early lifespan ( 76 , 77 ).

Newer Insights: How to Harness Digital Technology and Novel Methods of MH Promotion and Protection

With the advent of digital technology and simultaneous traction on mental health promotion and prevention interventions, preventive psychiatrists and public health experts have developed novel techniques to deliver mental health promotive and preventive interventions. These encompass different settings (e.g., school, home, workplace, the community at large, etc.) and levels of prevention (universal, selective, indicated) ( 78 – 80 ).

The advanced technologies and novel interventions have broadened the scope of MH promotion and prevention, such as addressing the mental health issues of individuals with chronic medical illness ( 81 , 82 ), severe mental disorders ( 83 ), children and adolescents with mental health problems, and geriatric population ( 78 ). Further, it has increased the accessibility and acceptability of such interventions in a non-stigmatizing and tailored manner. Moreover, they can be integrated into the routine life of the individuals.

For instance, Internet-and Mobile-based interventions (IMIs) have been utilized to monitor health behavior as a form of MH prevention and a stand-alone self-help intervention. Moreover, the blended approach has expanded the scope of MH promotive and preventive interventions such as face-to-face interventions coupled with remote therapies. Simultaneously, it has given way to the stepped-care (step down or step-up care) approach of treatment and its continuation ( 79 ). Also, being more interactive and engaging is particularly useful for the youth.

The blended model of care has utilized IMIs to a varying degree and at various stages of the psychological interventions. This includes IMIs as a supplementary approach to the face-to-face-interventions (FTFI), FTFI augmented by behavior intervention technologies (BITs), BITs augmented by remote human support, and fully automated BITs ( 84 ).

The stepped care model of mental health promotion and prevention strategies includes a stepped-up approach, wherein BITs are utilized to manage the prodromal symptoms, thereby preventing the onset of the full-blown episode. In the Stepped-down approach, the more intensive treatments (in-patient or out-patient based interventions) are followed and supplemented with the BITs to prevent relapse of the mental illness, such as for previously admitted patients with depression or substance use disorders ( 85 , 86 ).

Similarly, the latest research has developed newer interventions for strengthening the psychological resilience of the public or at-risk individuals, which can be delivered at the level of the home, such as, e.g., nurse family partnership program (to provide support to the young and vulnerable mothers and prevent childhood maltreatment) ( 87 ); family healing together program aimed at improving the mental health of the family members living with persons with mental illness (PwMI) ( 88 ). In addition, various novel interventions for MH promotion and prevention have been highlighted in the Table 2 .

Depiction of various novel mental health promotion and prevention strategies.

a/w, associated with; A-V, audio-visual; b/w, between; CBT, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; CES-Dep., Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale; CG, control group; FU, follow-up; GAD, generalized anxiety disorders-7; IA, intervention arm; HCWs, Health Care Workers; LMIC, low and middle-income countries; MDD, major depressive disorders; mgt, management; MH, mental health; MHP, mental health professional; MINI, mini neuropsychiatric interview; NNT, number needed to treat; PHQ-9, patient health questionnaire; TAU, treatment as usual .

Furthermore, school/educational institutes-based interventions such as school-Mental Health Magazines to increase mental health literacy among the teachers and students have been developed ( 80 ). In addition, workplace mental health promotional activities have targeted the administrators, e.g., guided “e-learning” for the managers that have shown to decrease the mental health problems of the employees ( 102 ).

Likewise, digital technologies have also been harnessed in strengthening community mental health promotive/preventive services, such as the mental health first aid (MHFA) Books on Prescription initiative in New Zealand provided information and self-help tools through library networks and trained book “prescribers,” particularly in rural and remote areas ( 103 ).

Apart from the common mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and behavioral disorders in the childhood/adolescents, novel interventions have been utilized to prevent the development of or management of medical, including preventing premature mortality and psychological issues among the individuals with severe mental illnesses (SMIs), e.g., Lets' talk about tobacco-web based intervention and motivational interviewing to prevent tobacco use, weight reduction measures, and promotion of healthy lifestyles (exercise, sleep, and balanced diets) through individualized devices, thereby reducing the risk of cardiovascular disorders ( 83 ). Similarly, efforts have been made to improve such individuals' coping skills and employment chances through the WorkingWell mobile application in the US ( 104 ).

Apart from the digital-based interventions, newer, non-digital-based interventions have also been utilized to promote mental health and prevent mental disorders among individuals with chronic medical conditions. One such approach in adventure therapy aims to support and strengthen the multi-dimensional aspects of self. It includes the physical, emotional or cognitive, social, spiritual, psychological, or developmental rehabilitation of the children and adolescents with cancer. Moreover, it is delivered in the natural environment outside the hospital premises, shifting the focus from the illness model to the wellness model ( 81 ). Another strength of this intervention is it can be delivered by the nurses and facilitate peer support and teamwork.

Another novel approach to MH prevention is gut-microbiota and dietary interventions. Such interventions have been explored with promising results for the early developmental disorders (Attention deficit hyperactive disorder, Autism spectrum disorders, etc.) ( 105 ). It works under the framework of the shared vulnerability model for common mental disorders and other non-communicable diseases and harnesses the neuroplasticity potential of the developing brain. Dietary and lifestyle modifications have been recommended for major depressive disorders by the Clinical Practice Guidelines in Australia ( 106 ). As most childhood mental and physical disorders are determined at the level of the in-utero and early after the birth period, targeting maternal nutrition is another vital strategy. The utility has been expanded from maternal nutrition to women of childbearing age. The various novel mental health promotion and prevention strategies are shown in Table 2 .

Newer research is emerging that has utilized the digital platform for training non-specialists in diagnosis and managing individuals with mental health problems, such as Atmiyata Intervention and The SMART MH Project in India, and The Allillanchu Project in Peru, to name a few ( 99 ). Such frameworks facilitate task-sharing by the non-specialist and help in reducing the treatment gap in these countries. Likewise, digital algorithms or decision support systems have been developed to make mental health services more transparent, personalized, outcome-driven, collaborative, and integrative; one such example is DocuMental, a clinical decision support system (DSS). Similarly, frameworks like i-PROACH, a cloud-based intelligent platform for research outcome assessment and care in mental health, have expanded the scope of the mental health support system, including promoting research in mental health ( 100 ). In addition, COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in wider dissemination of the applications based on the evidence-based psycho-social interventions such as National Health Service's (NHS's) Mind app and Headspace (teaching meditation via a website or a phone application) that have utilized mindfulness-based practices to address the psychological problems of the population ( 101 ).

Challenges in Implementing Novel MH Promotion and Prevention Strategies

Although novel interventions, particularly internet and mobile-based interventions (IMIs), are effective models for MH promotion and prevention, their cost-effectiveness requires further exploration. Moreover, their feasibility and acceptability in LMICs could be challenging. Some of these could be attributed to poor digital literacy, digital/network-related limitations, privacy issues, and society's preparedness to implement these interventions.

These interventions need to be customized and adapted according to local needs and context, for which implementation and evaluative research are warranted. In addition, the infusion of more human and financial resources for such activities is required. Some reports highlight that many of these interventions do not align with the preferences and use the pattern of the service utilizers. For instance, one explorative research on mental health app-based interventions targeting youth found that despite the burgeoning applications, they are not aligned with the youth's media preferences and learning patterns. They are less interactive, have fewer audio-visual displays, are not youth-specific, are less dynamic, and are a single touch app ( 107 ).

Furthermore, such novel interventions usually come with high costs. In low-resource settings where service utilizers have limited finances, their willingness to use such services may be doubtful. Moreover, insurance companies, including those in high-income countries (HICs), may not be willing to fund such novel interventions, which restricts the accessibility and availability of interventions.

Research points to the feasibility and effectiveness of incorporating such novel interventions in routine services such as school, community, primary care, or settings, e.g., in low-resource settings, the resource persons like teachers, community health workers, and primary care physicians are already overburdened. Therefore, their willingness to take up additional tasks may raise skepticism. Moreover, the attitudinal barrier to moving from the traditional service delivery model to the novel methods may also impede.

Considering the low MH budget and less priority on the MH prevention and promotion activities in most low-resource settings, the uptake of such interventions in the public health framework may be lesser despite the latter's proven high cost-effectiveness. In contrast, policymakers may be more inclined to invest in the therapeutic aspects of MH.

Such interventions open avenues for personalized and precision medicine/health care vs. the traditional model of MH promotion and preventive interventions ( 108 , 109 ). For instance, multivariate prediction algorithms with methods of machine learning and incorporating biological research, such as genetics, may help in devising tailored, particularly for selected and indicated prevention, interventions for depression, suicide, relapse prevention, etc. ( 79 ). Therefore, more research in this area is warranted.

To be more clinically relevant, greater biological research in MH prevention is required to identify those at higher risk of developing given mental disorders due to the existing risk factors/prominent stress ( 110 ). For instance, researchers have utilized the transcriptional approach to identify a biological fingerprint for susceptibility (denoting abnormal early stress response) to develop post-traumatic stress disorders among the psychological trauma survivors by analyzing the expression of the Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles ( 111 ). Identifying such biological markers would help target at-risk individuals through tailored and intensive interventions as a form of selected prevention.

Similarly, such novel interventions can help in targeting the underlying risk such as substance use, poor stress management, family history, personality traits, etc. and protective factors, e.g., positive coping techniques, social support, resilience, etc., that influences the given MH outcome ( 79 ). Therefore, again, it opens the scope of tailored interventions rather than a one-size-fits-all model of selective and indicated prevention for various MH conditions.

Furthermore, such interventions can be more accessible for the hard-to-reach populations and those with significant mental health stigma. Finally, they play a huge role in ensuring the continuity of care, particularly when community-based MH services are either limited or not available. For instance, IMIs can maintain the improvement of symptoms among individuals previously managed in-patient, such as for suicide, SUDs, etc., or receive intensive treatment like cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for depression or anxiety, thereby helping relapse prevention ( 86 , 112 ). Hence, such modules need to be developed and tested in low-resource settings.

IMIs (and other novel interventions) being less stigmatizing and easily accessible, provide a platform to engage individuals with chronic medical problems, e.g., epilepsy, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, etc., and non-mental health professionals, thereby making it more relevant and appealing for them.

Lastly, research on prevention-interventions needs to be more robust to adjust for the pre-intervention matching, high attrition rate, studying the characteristics of treatment completers vs. dropouts, and utilizing the intention-to-treat analysis to gauge the effect of such novel interventions ( 78 ).

Recommendations for Low-and-Middle-Income Countries

Although there is growing research on the effectiveness and utility of mental health promotion/prevention interventions across the lifespan and settings, low-resource settings suffer from specific limitations that restrict the full realization of such public health strategies, including implementing the novel intervention. To overcome these challenges, some of the potential solutions/recommendations are as follows:

- The mental health literacy of the population should be enhanced through information, education, and communication (IEC) activities. In addition, these activities should reduce stigma related to mental problems, early identification, and help-seeking for mental health-related issues.

- Involving teachers, workplace managers, community leaders, non-mental health professionals, and allied health staff in mental health promotion and prevention is crucial.

- Mental health concepts and related promotion and prevention should be incorporated into the education curriculum, particularly at the medical undergraduate level.

- Training non-specialists such as community health workers on mental health-related issues across an individual's life course and intervening would be an effective strategy.

- Collaborating with specialists from other disciplines, including complementary and alternative medicines, would be crucial. A provision of an integrated health system would help in increasing awareness, early identification, and prompt intervention for at-risk individuals.

- Low-resource settings need to develop mental health promotion interventions such as community-and school-based interventions, as these would be more culturally relevant, acceptable, and scalable.

- Utilizing a digital platform for scaling mental health services (e.g., telepsychiatry services to at-risk populations) and training the key individuals in the community would be a cost-effective framework that must be explored.

- Infusion of higher financial and human resources in this area would be a critical step, as, without adequate resources, research, service development, and implementation would be challenging.

- It would also be helpful to identify vulnerable populations and intervene in them to prevent the development of clinical psychiatric disorders.

- Lastly, involving individuals with lived experiences at the level of mental health planning, intervention development, and delivery would be cost-effective.

Clinicians, researchers, public health experts, and policymakers have increasingly realized mental health promotion and prevention. Investment in Preventive psychiatry appears to be essential considering the substantial burden of mental and neurological disorders and the significant treatment gap. Literature suggests that MH promotive and preventive interventions are feasible and effective across the lifespan and settings. Moreover, various novel interventions (e.g., internet-and mobile-based interventions, new therapies) have been developed worldwide and proven effective for mental health promotion and prevention; such interventions are limited mainly to HICs.

Despite the significance of preventive psychiatry in the current world and having a wide-ranging implication for the wellbeing of society and individuals, including those suffering from chronic medical problems, it is a poorly utilized public health field to address the population's mental health needs. Lately, researchers and policymakers have realized the untapped potentialities of preventive psychiatry. However, its implementation in low-resource settings is still in infancy and marred by several challenges. The utilization of novel interventions, such as digital-based interventions, and blended and stepped-care models of care, can address the enormous mental health need of the population. Additionally, it provides mental health services in a less-stigmatizing and easily accessible, and flexible manner. More research concerning this is required from the LMICs.

Author Contributions

VS, AK, and SG: methodology, literature search, manuscript preparation, and manuscript review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.898009/full#supplementary-material

- Open access

- Published: 28 January 2021

Evidence for implementation of interventions to promote mental health in the workplace: a systematic scoping review protocol

- Charlotte Paterson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6796-227X 1 ,

- Caleb Leduc 2 , 3 ,

- Margaret Maxwell 1 ,

- Birgit Aust 4 ,

- Benedikt L. Amann 5 ,

- Arlinda Cerga-Pashoja 6 ,

- Evelien Coppens 7 ,

- Chrisje Couwenbergh 8 ,

- Cliodhna O’Connor 2 , 3 ,

- Ella Arensman 2 , 3 , 9 , 10 &

- Birgit A. Greiner 2

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 41 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

15 Citations

14 Altmetric

Metrics details

Mental health problems are common in the working population and represent a growing concern internationally, with potential impacts on workers, organisations, workplace health and compensation authorities, labour markets and social policies. Workplace interventions that create workplaces supportive of mental health, promote mental health awareness, destigmatise mental illness and support those with mental disorders are likely to improve health and economical outcomes for employees and organisations. Identifying factors associated with successful implementation of these interventions can improve intervention quality and evaluation, and facilitate the uptake and expansion. Therefore, we aim to review research reporting on the implementation of mental health promotion interventions delivered in workplace settings, in order to increase understanding of factors influencing successful delivery.

Methods and analysis

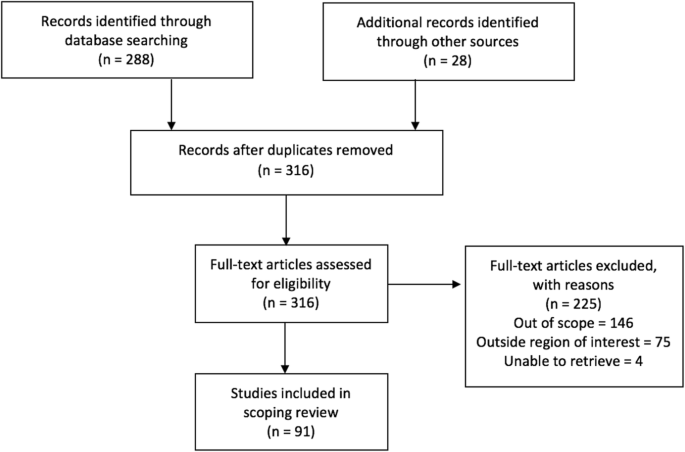

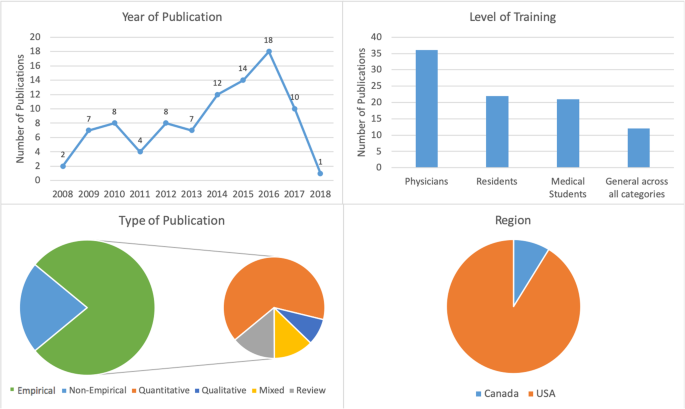

A scoping review will be conducted incorporating a stepwise methodology to identify relevant literature reviews, primary research and grey literature. This review is registered with Research Registry (reviewregistry897). One reviewer will conduct the search to identify English language studies in the following electronic databases from 2008 through to July 1, 2020: Scopus, PROSPERO, Health Technology Assessments, PubMed, Campbell Collaboration, Joanna Briggs Library, PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection, CINAHL and Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH). Reference searching, Google Scholar, Grey Matters, IOSH and expert contacts will be used to identify grey literature. Two reviewers will screen title and abstracts, aiming for 95% agreement, and then independently screen full texts for inclusion. Two reviewers will assess methodological quality of included studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool and extract and synthesize data in line with the RE-AIM framework, Nielson and Randall’s model of organisational-level interventions and Moore’s sustainability criteria, if the data allows. We will recruit and consult with international experts in the field to ensure engagement, reach and relevance of the main findings.

This will be the first systematic scoping review to identify and synthesise evidence of barriers and facilitators to implementing mental health promotion interventions in workplace settings. Our results will inform future evaluation studies and randomised controlled trials and highlight gaps in the evidence base.

Systematic review registration

Research Registry ( reviewregistry897 )

Peer Review reports

Mental health problems are common in the working population and represent a growing concern, with potential impacts on workers’ wellbeing, health and discrimination; organisations through lost productivity; workplace health and compensation authorities due to growing job stress-related claims; and social welfare systems owing to increased working age disability pensions for mental disorders [ 1 ]. Mental health refers to ‘a state of wellbeing in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’ [ 2 ]. Mental health problems therefore include daily worries, stress, burnout and poor wellbeing, as well as mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety [ 3 ]. Psychosocial stresses in the workplace, such as job uncertainty, low job control, poor management, harassment and bullying, poor communication and long hours, have been shown to undermine mental wellbeing [ 4 ]. A negative working environment may lead to physical and mental health problems, harmful use of substances or alcohol, absenteeism, presenteeism and lost productivity [ 5 ]. Although it is acknowledged that mental health problems exist in the workplace, stigma and the social exclusion of people with mental health problems may be leading to under-recognition of such problems and the subsequent low treatment rate of mental health problems [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Under-treatment has been shown to increase the indirect cost of mental disorders, physical morbidity and mortality [ 9 , 10 ].

Several studies have evaluated workplace interventions targeting mental wellbeing [ 11 ]. Workplace interventions that support mental health and wellbeing have been shown to help reduce sickness absence [ 12 ]. In addition, workplaces that promote mental health awareness, destigmatise mental illness and support people with mental disorders are more likely to reduce levels of depression and absenteeism while increasing productivity as well as benefiting from associated economic gains [ 13 ]. Improving access to evidence-based interventions for minor stress-related depressive symptoms in occupational sectors associated with high suicide rates, e.g. construction, healthcare and information communication and technology (ICT), is likely to prevent the development of severe depressive disorders and comorbidities, and subsequent suicidal behaviour [ 13 ].

Although high-quality evaluations underpin evidence-based interventions (EBI), implementation research can improve the quality of such evaluations and facilitate the uptake and reach of EBIs and other research findings into practice [ 14 ]. One effective way to do this is to identify factors that influence the delivery and uptake of interventions during development, feasibility, evaluation and implementation stages [ 15 ].

So far, research into specific mechanisms and process factors associated with the successful delivery of mental health promotion interventions in the workplace is limited [ 16 , 17 ]. This review aims to identify and analyse research on the implementation of workplace mental health promotion interventions; specifically, to understand the barriers and facilitators that influence their delivery in order to provide insights and inform future intervention, evaluation and implementation efforts. This work represents a direct response to recent calls within intervention research to examine the mechanisms through which interventions bring about change and the documentation of contextual and procedural considerations that either facilitate or limit implementation [ 16 , 17 ].

Aims and objectives

This review is part of a wider project intending to develop, evaluate and implement a multi-level intervention (Mental Health Promotion and Intervention in Occupational Settings, MENTUPP) [ 18 ], which aims to improve mental health and wellbeing in the workplace involving 15 European and Australian partners, with a particular focus on small to medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in three sectors with high prevalence rates of mental health problems and suicidal behaviour, namely ICT, healthcare and construction sectors. More broadly, the purpose of this review is to collate and critically appraise workplace mental health intervention implementation literature to understand how and why certain interventions are more effectively implemented than others and inform MENTUPP and future programmes. The objectives of the review are to:

1. Systematically identify and document research explicitly reporting on the quality of delivery and implementation of mental health promotion interventions in workplaces (e.g. reporting the quality of implementation, a process evaluation or realist evaluation) and, if the evidence allows, specifically in ICT, construction and healthcare settings and SMEs.

2. Identify the barriers and facilitators associated with the quality of implementation of mental health promotion interventions in workplace settings and, if the evidence allows, specifically in ICT, construction or healthcare settings and within SMEs, as it relates to the MENTUPP programme of work.

Based on these objectives, our research questions are:

What is the scope of research with explicit analysis of implementation aspects of mental health promotion interventions in the workplace?

What are the barriers and facilitators to implementing mental health promotion interventions in the workplace?

What are the barriers and facilitators to implementing mental health promotion interventions in SMEs and in the ICT, construction and healthcare sectors?

Methods/design

Study design.

We will conduct a systematic scoping review using the 6-stage scoping review framework [ 19 , 20 ] to systematically identify the implementation evidence and factors associated with successful implementation of mental health promotion in workplace settings. Scoping reviews aim to map a broad field of literature and to summarise and disseminate research findings [ 19 , 21 ], rather than address very focussed questions. This approach is in line with the aims of this review, given the wide range of potential successful and failed interventions, contexts and implementation factors. We will comprehensively explore the relevant research, using iterative methods to develop a rigorous and systematic search of the existing literature [ 20 ]. We will recruit and consult with international experts in the field according to both applied organisational and research experience at key stages of the review process and subsequently to ensure engagement, reach and relevance of the process and main findings. The active involvement of people affected by a research topic has been argued to be beneficial to the quality, relevance and impact of research [ 22 , 23 ], and it enhances the perceived usefulness of systematic review evidence and addresses barriers to the uptake of synthesised research evidence [ 24 , 25 ].

Our protocol was developed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Protocol checklist (PRISMA-P) [ 26 ] (see Additional file 1 ). The present protocol has been registered within the Research Registry (reviewregistry897). The results of our scoping review will be reported in accordance with PRISMA-ScR [ 27 ].

Operationally, the current review will systematically conduct the searches based on the following definition of key terms :

● Implementation : The results of this review will inform the design of a feasibility and definitive trial of mental health promotion in the workplace. As such, implementation refers to interventions being delivered at feasibility and piloting, evaluation and implementation stages of the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework (15).

● Mental health promotion refers to interventions or programmes that aim to treat (intervene to improve mental health), prevent (inhibit the escalation of subclinical symptoms to clinical severity or prevent the onset of mental health problems) and promote (improve mental health by targeting positive components of mental health) mental health and wellbeing [ 28 ].

● Barriers are defined as any variable or condition that impedes the implementation or delivery of mental health promotion interventions.

● Facilitators are defined as any variable or condition that facilitates or improves the implementation or delivery of mental health promotion interventions.

● Workplace settings include any organisation operating with paid employees. Therefore, mental health promotion interventions must be delivered through, or be associated with, the workplace. Sector-specific definitions from the European Commission were used [ 29 ]. The ICT sector will include telecommunications activities, information technology activities and other information service activities (divisions 61–63); the healthcare sector will include healthcare provided by medical professionals in hospitals or other facilities and residential activities, but not social work activities (divisions 86–87); and the construction sector will include construction of buildings, civil engineering and specialised construction activities (divisions 41–43). Small- to medium-sized enterprises include those employing < 250 employees [ 30 ].

Information sources and search strategy

We will use iterative methods to develop and apply a rigorous and comprehensive search strategy, combining a series of free text terms and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms for key concepts: (a) workplace AND (b) mental health, AND (c) interventions, AND (d) implementation. A preliminary search strategy (see Additional file 2 ) has been developed for PsycINFO, using established search terms (from Cochrane and other previous search strategies [ 31 , 32 , 33 ], peer-reviewed in accordance with PRESS guidelines [ 34 ]. Boolean operators will be used to maximise the penetration of terms searched, and appropriate “wild cards” will be employed to account for plurals, variations in databases, and spelling.

We will use a stepwise methodology [ 35 ] to identify the highest quality evidence in a systematic way and capture grey literature. Grey literature will be included because it is likely that due to publication bias some unsuccessful interventions have not been published in peer-reviewed journals. A number of contingency plans have been built into the methods to allow an iterative approach to the search and selection of evidence for the review (Additional file 3 ). We will use established search terms and adapt searches for each of the following major electronic databases outlined below.

In step 1, we will search the following electronic databases for systematic reviews:

● Health Technology Assessments

● Campbell Collaboration

● Joanna Briggs Library

● Web of Science Core Collection

In step 2, we will look for primary studies reporting implementation of mental health promotion interventions in the following electronic databases:

● PsychINFO

● Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) research database.

Step 3 will involve supplementary searches involving a thorough review of relevant study references, grey literature and personal contacts using a systematic approach (Additional file 3 ). This will include searching:

● Reference searching : relevant studies included in published guidelines, relevant systematic reviews and listed in the included studies’ reference lists and bibliographies.

● Grey literature : Google Scholar (25 pages relevant), Grey Matters and the Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) research database.

● Personal contacts : we will contact international experts and authors of papers reporting trials (from 2008) on workplace interventions to address mental health promotion.

Criteria for considering studies for inclusion

The scoping review will address factors associated with successful implementation and therefore focus primarily on feasibility and process studies or realist evaluations. Although we will look at the relation between implementation and effects, the main aim of the review is to identify factors associated with implementation, specifically barriers and facilitators. The focus of this review will be cognisant of outcomes indicating successful implementation, including programme uptake, retention and impact.

Study designs

We will include any paper, regardless of study design, using either quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods, which explicitly investigates, reports or discusses, in the title or abstract, any aspect of implementation of specific mental health promotion interventions (i.e. quality of implementation, a process evaluation including rich data or a realist evaluation) delivered in the workplace. This includes literature reviews (systematic reviews, scoping reviews, meta-analyses) and primary research studies published either in the peer-reviewed scientific literature or in the grey literature. We will exclude opinion pieces, commentaries, website discussions, blogs and magazine and newspaper articles.

We will include studies with adult participants (aged 16–65) who are in formal employment, including those on sickness absence leave and are expected to return to work.

Interventions

Interventions, whose implementation is of interest, are purposefully applied strategies delivered in the workplace, targeting either workers, supervisors, managers, occupational health professionals, owners/executives or entire organisations. Included interventions will aim to (i) help protect mental health by reducing work-related risk factors (e.g. job strain, poor working conditions and job stressors such as job insecurity, psychological harassment (e.g. due to stigma), low social support at work, organisational injustice, and effort-reward imbalance); (ii) promote workplace mental health wellbeing by creating positive aspects of work, and develop employees’ strengths (e.g. satisfaction, wellbeing, psychological capital, positive mental health, resilience and positive organisational attributes such as authentic leadership, supportive workplace culture and workplace social capital); and (iii) respond to mental health problems when they occur (e.g. interventions targeting burnout, stress, anxiety, depression or return to work) [ 36 ]. We will exclude studies that evaluate the implementation of general mental health interventions that are not specifically associated with workplace factors or delivered in work contexts (e.g. healthy eating or exercise at home), mental health interventions that are not formally implemented in the workplace (e.g. online work-related mental health interventions freely available online without association to an organisation) and one-off events (e.g. distribution of mental health educational material or one-off information sessions through guest lecturers). Interventions not directly targeting psychological wellbeing or mental health will be included if the primary outcome is related to psychological wellbeing or mental health (e.g. a physical activity programmes delivered in the workplace with a primary outcome for improving mental health). Interventions that target a wide range of health and wellbeing outcomes, e.g. physical activity, obesity, smoking cessation and stress, will be excluded.

Outcomes of interest

We will only include studies reporting rich data on any implementation outcomes and will categorise outcomes within our data charting. We anticipate that identified outcomes may include fidelity, reach, dose delivered, dose received, adoption, penetration, feasibility, acceptability, context factors, process factors, sustainability factors, programme theories, theories of change and failure theories. We will exclude studies focusing on only the impact of interventions on disease end points, i.e. which do not evaluate implementation quality.

Types of settings

We will include studies conducted in any geographical location, and we will categorise the location based on relevance to Europe and Australia during data charting. The intervention must be delivered in, or in association with, a workplace setting and be implemented in the work schedule, work systems or administrative structures.

Studies published in English will be included in steps 1 and 2. Studies published in English, French and German will be included in step 3.

Publication date

Studies published in the last 13 years will be included. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Plan of Action on Work’s Health (2008–2017) [ 37 ] and the Mental Health Action Plan (2013–2020) [ 38 ] highlight the importance of promoting good mental health in the workplace. Furthermore, the field of implementation science is fairly new; therefore, literature published after 2008 is deemed to be most relevant to this review.

Study selection

Rayyan will be used for the study selection process [ 39 ]. Two reviewers will be utilised for a provisional screening of all titles (CP, CL), removing any clearly irrelevant papers. To ensure reliability between reviewers, 15% of the study titles will be reviewed blindly by both reviewers independently, aiming for 95% agreement. Where 95% agreement is not reached, a further 15% will be reviewed by both reviewers independently. Any discrepancy between reviewers will be discussed and, if necessary, will involve a third reviewer to resolve. The remaining study titles will be screened for abstract review by a single reviewer. Two reviewers will then be involved in screening the remaining potential abstracts (CP, CL) and rate them as relevant, irrelevant or unsure. To ensure consistency between reviewers, 15% will be checked independently, and where agreement does not reach 95%, a further 15% will be reviewed by both reviewers. Studies that are ranked as irrelevant will be excluded. We will obtain the full papers for the remaining studies. Two reviewers (CP, CL) will then independently assess each of these against the selection criteria. We will resolve any disagreement through discussion and will involve a third independent reviewer if needed.

Charting the data

Data extraction.

We will pilot a data extraction template on the first four included studies and amend as required. We will extract key study details (e.g. study design, country, sample size, sector, intervention characteristics, impact on primary outcome, etc.) and implementation data (e.g. direct quotes, page numbers) will be structured using an adapted version of the RE-AIM framework [ 40 ] which has been complemented using selected categories from Nielson and Randall’s model of organisational-level interventions [ 16 ] and Moore’s sustainability criteria [ 41 ]. To ensure reliability, data from 15% of included papers will be coded by two reviewers (CP and CL) independently. Any ambiguity identified will be resolved through discussion with other members of the review team. Study authors will be contacted via email where data are missing or unclearly reported.

Data coding

Data will be coded as follows:

● Stage of intervention development/evaluation will be coded according to the MRC framework (i.e. feasibility, evaluation or implementation) [ 15 ].

● Countries will be coded using the World Bank classification [ 42 ] to identify countries of relevance to future research, e.g. Europe and Australia.

● Implementation evidence will be mapped using a modified version of the RE-AIM framework [ 40 ], which is organised into five categories: reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance. This framework also allows evaluation of implementation at an individual and organisational level.

● Nielson and Randall’s model of organisational-level interventions [ 16 ] will supplement the RE-AIM framework for this review allowing for extraction based on the intervention itself, the context in which it was delivered and participants’ mental models.

● Intervention sustainability will be coded using Moore’s definitions of sustainability [ 41 ], e.g. continued delivery, behaviour change, evolution/adaptation and continued benefits.

Quality appraisal

In line with previous systematic and scoping reviews that include mixed methods literature [ 32 , 43 ], the methodological quality of included studies will be assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [ 44 ] for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research designs. Each study will receive a methodological rating between 0 and 100 (with 100 being the highest quality), based on the evaluation of study selection bias, study design, data collection methods, sample size, intervention integrity and analysis. Where studies integrate the process evaluation into the study design, the quality of the entire study will be assessed. Methodological quality will be rated by two reviewers (CL and CP). To ensure consistency between reviewers, 15% will be rated independently, and if agreement is reached, one reviewer will rate the remaining papers. Any ambiguity identified will be resolved through discussion with other members of the review team.

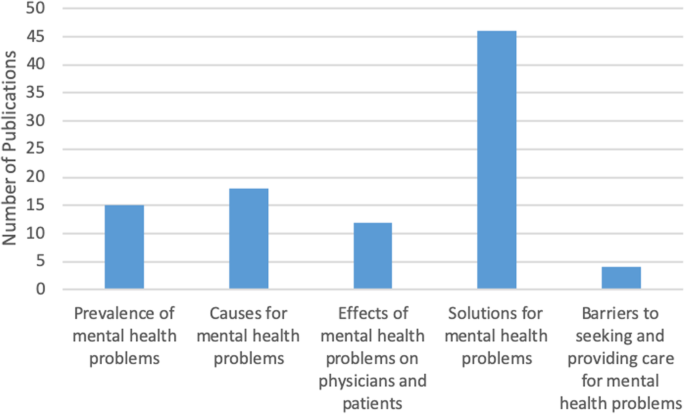

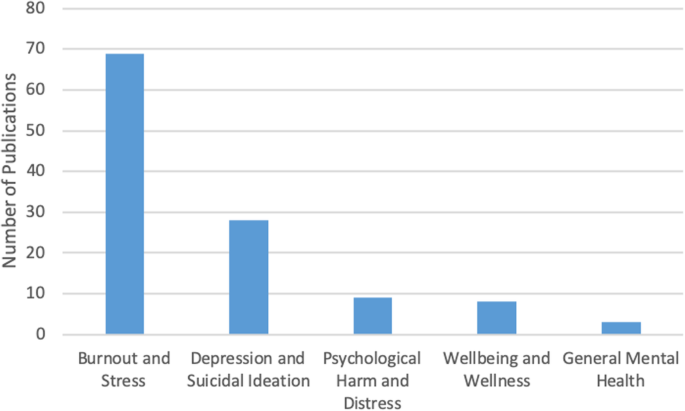

Collating, summarising and reporting

Descriptive characteristics of included studies will be tabulated and brought together using a narrative synthesis. To answer question one, we will summarise the type of evidence relating to the implementation of the interventions in workplace settings. To answer questions two and three, barriers and facilitators will be categorised according to the RE-AIM framework [ 40 ], modified using Nielson & Randall’s (2013) model for evaluation organisational-level interventions [ 16 ] and Moore’s sustainability criteria [ 45 ]. We will present tabulated data by sector and then occupational level (i.e. organisational, managerial, etc.) and intervention type. If the evidence allows, to further answer research question three, we will present tabulated data from included studies focusing specifically on SMEs using the same format. Key findings will be brought together within a narrative synthesis [ 46 , 47 ].

The aim of this systematic scoping review is to identify research that reports on the feasibility and implementation of mental health promotion interventions that are delivered in workplace settings, and to specifically understand the factors (barriers and facilitators) that influence the successful delivery of mental health promotion interventions in the workplace. This review is part of the MENTUPP project [ 18 ] which aims to develop, evaluate and implement mental health promotion interventions for the workplace, particularly in SMEs in the construction, healthcare and ICT sectors. As such, our review will aim to focus on intervention implementation barriers and facilitators in SMEs and in the construction, healthcare and ICT sectors. This work addresses recent calls within intervention research to examine the mechanisms through which interventions bring about change and the documentation of contextual and procedural considerations that either facilitate or limit implementation [ 16 , 17 ]. Additionally, this timely review responds to international policy regarding mental health in the workplace [ 8 ]. In an effort to maintain quality and identify all relevant information, we have presented a rigorous and systematic approach to this scoping review. We have maintained a broad search strategy in order to capture the variety of implementation research that may be available, and we will consult with stakeholders to ensure the main findings are useful and relevant. The results of this review will identify barriers and facilitators to implementation of mental health promotion interventions in the workplace and inform future pilot and definitive RCTs within the MENTUPP project [ 18 ]. This will help inform future interventions, and the evaluation and implementation efforts of such interventions, which will subsequently improve outcomes for employees and organisations through improved mental wellbeing; reduced symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress; and reduced presenteeism and absenteeism. In addition, this review will contribute to implementation science related to workplace mental health promotion.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study will be included in the published scoping review article and will be available by request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Information and communication technology

Institution of occupational safety and health

Medical research council

Medical subject heading

Mixed methods appraisal tool

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews

Randomized controlled trial

Reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance

Small-to-medium sized enterprises

World health Organization

Publications Office of the European Union. 5th European Working Conditions Survey [Internet]. Quality Assurance Report, 2010 http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/ewcs/2010/documents/qualassurance.pdf .[cited 2020 May 7]. Available from: www.eurofound.europa.eu .

WHO. Mental health: strengthening our response [Internet]. Fact sheet N°220. 2010 [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response .

MentalHealthFoundation.org [Internet]. United Kingdom: Mental Health Foundation; [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/your-mental-health/about-mental-health/what-are-mental-health-problems .

Virtanen M. Psychosocial job stressors and suicidality: can stress at work lead to suicide? Occup Environ Med. [Internet] 2018;75(4):243–4. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2017-104689 . [cited 2020 July 27].

World Health Organisation. Addressing comorbidity between mental disorders and major noncommunicable diseases [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 May 7]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest .

Brohan E, Thornicroft G. Stigma and discrimination of mental health problems workplace implications. Occup Med. [Internet] 2010;60(6):414–5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqq048 . [cited 2020 July 27].

Mental Health Foundation Scotland. Mental Health in the Workplace Seminar Report. 2018.

WHO. Mental health in the workplace [Internet]. WHO. World Health Organization; 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/in_the_workplace/en/ .

Rugulies R, Aust B, Madsen IEH. Effort–reward imbalance at work and risk of depressive disorders. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2017;43:294–306.

Theorell T, Hammarström A, Aronsson G, Träskman Bendz L, Grape T, Hogstedt C, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms [Internet]. Vol. 15, BMC Public Health; 2015. p. 738. [cited 2020 May 7] Available from: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/ https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4 .

Graveling R, Crawford J, Cowrie H, Amati C, Vohra S. A review of workplace interventions that promote mental wellbeing in the workplace [Internet]. 2008. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239615077_A_Review_of_Workplace_Interventions_that_Promote_Mental_Wellbeing_in_the_Workplace .

Milner A, Hjelmeland H, Arensman E, De LD. Social-environmental factors and suicide mortality: a narrative review of over 200 articles. Sociol Mind. 2013;03(02):137–48 [cited 2020 May 7] Available from: http://www.scirp.org/journal/sm .

Article Google Scholar