- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

Prewriting Strategies

Five useful strategies.

Pre-writing strategies use writing to generate and clarify ideas. While many writers have traditionally created outlines before beginning writing, there are several other effective prewriting activities. We often call these prewriting strategies “brainstorming techniques.” Five useful strategies are listing, clustering, freewriting, looping, and asking the six journalists' questions. These strategies help you with both your invention and organization of ideas, and they can aid you in developing topics for your writing.

Listing is a process of producing a lot of information within a short time by generating some broad ideas and then building on those associations for more detail with a bullet point list. Listing is particularly useful if your starting topic is very broad, and you need to narrow it down.

- Jot down all the possible terms that emerge from the general topic you are working on. This procedure works especially well if you work in a team. All team members can generate ideas, with one member acting as scribe. Do not worry about editing or throwing out what might not be a good idea. Simply write down as many possibilities as you can.

- Group the items that you have listed according to arrangements that make sense to you. Are things thematically related?

- Give each group a label. Now you have a narrower topic with possible points of development.

- Write a sentence about the label you have given the group of ideas. Now you have a topic sentence or possibly a thesis statement .

Clustering, also called mind mapping or idea mapping, is a strategy that allows you to explore the relationships between ideas.

- Put the subject in the center of a page. Circle or underline it.

- As you think of other ideas, write them on the page surrounding the central idea. Link the new ideas to the central circle with lines.

- As you think of ideas that relate to the new ideas, add to those in the same way.

The result will look like a web on your page. Locate clusters of interest to you, and use the terms you attached to the key ideas as departure points for your paper.

Clustering is especially useful in determining the relationship between ideas. You will be able to distinguish how the ideas fit together, especially where there is an abundance of ideas. Clustering your ideas lets you see them visually in a different way, so that you can more readily understand possible directions your paper may take.

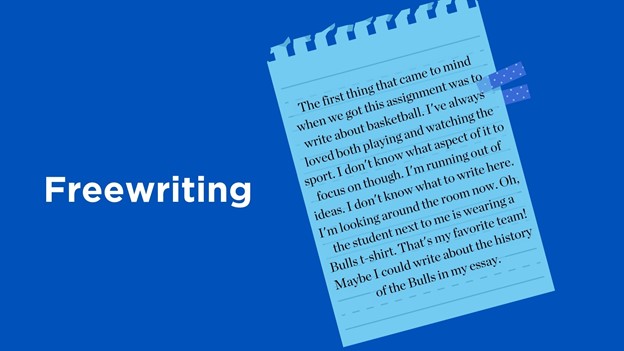

Freewriting

Freewriting is a process of generating a lot of information by writing non-stop in full sentences for a predetermined amount of time. It allows you to focus on a specific topic but forces you to write so quickly that you are unable to edit any of your ideas.

- Freewrite on the assignment or general topic for five to ten minutes non-stop. Force yourself to continue writing even if nothing specific comes to mind (so you could end up writing “I don’t know what to write about” over and over until an idea pops into your head. This is okay; the important thing is that you do not stop writing). This freewriting will include many ideas; at this point, generating ideas is what is important, not the grammar or the spelling.

- After you have finished freewriting, look back over what you have written and highlight the most prominent and interesting ideas; then you can begin all over again, with a tighter focus (see looping). You will narrow your topic and, in the process, you will generate several relevant points about the topic.

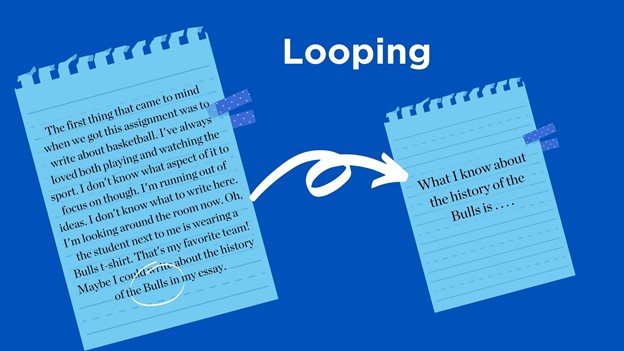

Looping is a freewriting technique that allows you to focus your ideas continually while trying to discover a writing topic. After you freewrite for the first time, identify a key thought or idea in your writing, and begin to freewrite again, with that idea as your starting point. You will loop one 5-10 minute freewriting after another, so you have a sequence of freewritings, each more specific than the last. The same rules that apply to freewriting apply to looping: write quickly, do not edit, and do not stop.

Loop your freewriting as many times as necessary, circling another interesting topic, idea, phrase, or sentence each time. When you have finished four or five rounds of looping, you will begin to have specific information that indicates what you are thinking about a particular topic. You may even have the basis for a tentative thesis or an improved idea for an approach to your assignment when you have finished.

The Journalists' Questions

Journalists traditionally ask six questions when they are writing assignments that are broken down into five W's and one H: Who? , What? , Where? , When? , Why? , and How? You can use these questions to explore the topic you are writing about for an assignment. A key to using the journalists' questions is to make them flexible enough to account for the specific details of your topic. For instance, if your topic is the rise and fall of the Puget Sound tides and its effect on salmon spawning, you may have very little to say about Who if your focus does not account for human involvement. On the other hand, some topics may be heavy on the Who , especially if human involvement is a crucial part of the topic.

The journalists' questions are a powerful way to develop a great deal of information about a topic very quickly. Learning to ask the appropriate questions about a topic takes practice, however. At times during writing an assignment, you may wish to go back and ask the journalists' questions again to clarify important points that may be getting lost in your planning and drafting.

Possible generic questions you can ask using the six journalists' questions follow:

- Who? Who are the participants? Who is affected? Who are the primary actors? Who are the secondary actors?

- What? What is the topic? What is the significance of the topic? What is the basic problem? What are the issues related to that problem?

- Where? Where does the activity take place? Where does the problem or issue have its source? At what place is the cause or effect of the problem most visible?

- When? When is the issue most apparent? (in the past? present? future?) When did the issue or problem develop? What historical forces helped shape the problem or issue and at what point in time will the problem or issue culminate in a crisis? When is action needed to address the issue or problem?

- Why? Why did the issue or problem arise? Why is it (your topic) an issue or problem at all? Why did the issue or problem develop in the way that it did?

- How? How is the issue or problem significant? How can it be addressed? How does it affect the participants? How can the issue or problem be resolved?

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Introduction to Prewriting (Invention)

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you sit down to write...

- Does your mind turn blank?

- Are you sure you have nothing to say?

If so, you're not alone. Many writers experience this at some time or another, but some people have strategies or techniques to get them started. When you are planning to write something, try some of the following suggestions.

You can try the textbook formula:

- State your thesis.

- Write an outline.

- Write the first draft.

- Revise and polish.

. . . but that often doesn't work.

Instead, you can try one or more of these strategies:

Ask yourself what your purpose is for writing about the subject.

There are many "correct" things to write about for any subject, but you need to narrow down your choices. For example, your topic might be "dorm food." At this point, you and your potential reader are asking the same question, "So what?" Why should you write about this, and why should anyone read it?

Do you want the reader to pity you because of the intolerable food you have to eat there?

Do you want to analyze large-scale institutional cooking?

Do you want to compare Purdue's dorm food to that served at Indiana University?

Ask yourself how you are going to achieve this purpose.

How, for example, would you achieve your purpose if you wanted to describe some movie as the best you've ever seen? Would you define for yourself a specific means of doing so? Would your comments on the movie go beyond merely telling the reader that you really liked it?

Start the ideas flowing

Brainstorm. Gather as many good and bad ideas, suggestions, examples, sentences, false starts, etc. as you can. Perhaps some friends can join in. Jot down everything that comes to mind, including material you are sure you will throw out. Be ready to keep adding to the list at odd moments as ideas continue to come to mind.

Talk to your audience, or pretend that you are being interviewed by someone — or by several people, if possible (to give yourself the opportunity of considering a subject from several different points of view). What questions would the other person ask? You might also try to teach the subject to a group or class.

See if you can find a fresh analogy that opens up a new set of ideas. Build your analogy by using the word like. For example, if you are writing about violence on television, is that violence like clowns fighting in a carnival act (that is, we know that no one is really getting hurt)?

Take a rest and let it all percolate.

Summarize your whole idea.

Tell it to someone in three or four sentences.

Diagram your major points somehow.

Make a tree, outline, or whatever helps you to see a schematic representation of what you have. You may discover the need for more material in some places. Write a first draft.

Then, if possible, put it away. Later, read it aloud or to yourself as if you were someone else. Watch especially for the need to clarify or add more information.

You may find yourself jumping back and forth among these various strategies.

You may find that one works better than another. You may find yourself trying several strategies at once. If so, then you are probably doing something right.

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Prewriting and Outlining

Explore more of umgc.

- Writing Resources

Contact the Effective Writing Center

E-mail: writingcenter@umgc.edu

Get tips on developing and outlining your topic.

Prewriting exercises provide structure and meaning to your topic and research before you begin to write a draft. Using prewriting strategies to organize and generate ideas prevents a writer from becoming frustrated or stuck. Just as you would prepare to give a public speech on note cards, it is also necessary to write ideas down for a rough draft. After all, your audience is counting on a well-organized presentation of interesting facts, a storyline, or whatever you are required to write about. Prewriting exercises can help you focus your ideas, determine a topic, and develop a logical structure for your paper.

Prewriting Exercises

Brainstorming: It's often helpful to set a time limit on this; plan to brainstorm for ten minutes, for example. This will help you focus and keep you from feeling overwhelmed. This is especially helpful when you're still trying to narrow or focus your topic. You'll start with a blank page, and you'll write down as many ideas about your topic as you can think of. Ask yourself questions as you write: Why am I doing this? Why do I like this? Why don't I like this? What is the most interesting thing about this field or issue? How would my audience feel about this? What can we learn from this? How can we benefit from knowing more? When time is up, read over your list, and add anything else that you think of. Are there patterns or ideas that keep coming up? These are often clues about what is most important about this topic or issue.

Freewriting: A time limit is also useful in this exercise. Using a blank piece of paper or your word-processing program, summarize your topic in a sentence and keep writing. Write anything that comes to your mind and don't stop. Don't worry about grammar or spelling, and if you get stuck, just write whatever comes to mind. Continue until your time limit is up, and when it's time to stop, read over what you've written and start underlining the most important or relevant ideas. This will help you to identify your most important ideas, and you'll often be surprised by what you come up with.

Listing: In this exercise, you'll simply list all of your ideas. This will help you when you are mapping or outlining your ideas, because as you use an idea, you can cross it off your list.

Clustering: This is another way to record your thoughts and observations for a paragraph or essay after you have chosen a topic. First draw a circle near the center of a blank piece of paper, and in that circle, write the subject of your essay or paragraph. Then in a ring around the main circle, write down the main parts or subtopics within the main topic. Circle each of these, and then draw a line connecting them to the main circle in the middle. Then think of other ideas, facts, or issues that relate to each of the main parts/subtopics, circle these, and draw lines connecting them to the relevant part/subtopic. Repeat this process with each new circle until you run out of ideas. This is a great way of identifying the parts within your topic, which will provide content for the paper, and it also helps you discover how these parts relate to each other.

Outlining Your Paper

An outline is a plan for the paper that will help you organize and structure your ideas in a way that effectively communicates them to your reader and supports your thesis statement. You'll want to work on an outline after you've completed some of the other exercises, since having an idea of what you'll say in the paper will make it much easier to write. An outline can be very informal; you might simply jot down your thesis statement, what the introduction will discuss, what you'll say in the body of the paper, and what you want to include in the conclusion.

Remember that all writing — even academic writing — needs to tell a story: the introduction often describes what has already happened (the background or history of your topic), the body paragraphs might explain what is currently happening and what needs to happen (this often involves discussing a problem, the need for a solution, and possible solutions), and the conclusion usually looks to the future by focusing on what is likely to happen (what might happen next, and whether a solution is likely). If you work on telling a story in the paper, it will help you to structure it in a way that the reader can easily follow and understand.

Sometimes you may be required (or you may want) to develop a more formal outline with numbered and lettered headings and subheadings. This will help you to demonstrate the relationships between the ideas, facts, and information within the paper. Here's an example of what this might look like:

Introduction

Fact that grabs audience attention

Background/history of issue/problem/topic

Thesis statement

Current state of issue/problem/topic

Topic/claim sentence: Make a claim that explains what the paragraph is about

Evidence that supports/explains the claim (this is often research from secondary sources)

Analysis that explains how the evidence supports your claim and why this matters to the paper's thesis statement

The need for a solution or course of action

Topic/claim

Possible solution

Conclusion

What might happen now?

Is a solution likely?

What's the future of the issue?

Your outline will contain more detailed information, and if there are certain areas that the assignment requires you to cover, then you can modify the outline to include these. You can also expand it if you're writing a longer research paper: the discussion of the problem might need several paragraphs, for example, and you might discuss the pros and cons of several possible solutions.

The Effective Writing Center at UMGC: Assignment Analysis and the Sentence Outline

Our helpful admissions advisors can help you choose an academic program to fit your career goals, estimate your transfer credits, and develop a plan for your education costs that fits your budget. If you’re a current UMGC student, please visit the Help Center .

Personal Information

Contact information, additional information.

By submitting this form, you acknowledge that you intend to sign this form electronically and that your electronic signature is the equivalent of a handwritten signature, with all the same legal and binding effect. You are giving your express written consent without obligation for UMGC to contact you regarding our educational programs and services using e-mail, phone, or text, including automated technology for calls and/or texts to the mobile number(s) provided. For more details, including how to opt out, read our privacy policy or contact an admissions advisor .

Please wait, your form is being submitted.

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Prewriting

Prewriting basics.

Writing is a process, not an event. Taking the time to prepare for your writing will help make the writing process smooth and efficient. Follow these steps to ensure that your page does not stay blank for long. All of prewriting resources should be used simultaneously—you will often find yourself switching back and forth between brainstorming, critical reading, organizing, and fighting off writer’s block as you begin a new assignment.

Take Careful Notes

While reading, make sure that you are taking notes on relevant information.

Group your notes by topics or main ideas so you can see the connections among the material you have read. Try some of the Writing Center's brainstorming activities for help generating and connecting ideas.

Be sure to provide a citation (author, year, and page number) for every note that you take. This way, you will not have to interrupt your writing process later to find citation information.

Knowing how to read effectively will be one of your strongest assets in the prewriting process. Review the Academic Skills Center's resources on critical reading for more tips on getting the most from your research and reading.

Choose a Topic

Review the notes you have made to identify trends and areas of interest. Ask yourself where you have taken the most notes, where the most information is focused, and where any gaps in the literature might be. Do not discount your own interests—it is easiest to write a paper on a topic that intrigues you!

Use our brainstorming resources to help narrow down your paper topic, or consult your instructor for extra help. Once you have chosen a topic, you may need to go back to the note-taking stage and find more information to flesh out the body of your paper. Do not forget that most scholarly papers should advance a clear claim, articulated in the paper's thesis statement .

Develop Your Analysis

Good scholarly writers ask questions as they research, and the answers to those questions often become the organizing arguments in their papers. As you continue to read and take notes, think about the major claims that exist already about your topic. Ask yourself if you agree or disagree—or think the major claims should have a different direction entirely! Our resources on critical thinking can help you develop the main points of your paper before you begin writing. Remember that you will likely also be continuing the brainstorming process as you develop your analysis.

Prewriting Video Playlist

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

- Prewriting Demonstrations: Outlining (video transcript)

- Prewriting Demonstrations: Mindmapping (video transcript)

- Prewriting Demonstrations: Freewriting (video transcript)

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: How to Achieve Your Writing Goals

- Next Page: Critical Reading (ASC page)

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

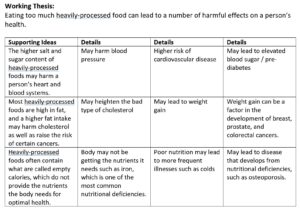

Idea Matrix for College Writing

An idea matrix is a way to prewrite once you have an idea of what you want to write about. An idea matrix for writing is just what it sounds like – it’s a table or grid that helps you identify, organize, and develop your ideas. You lay out your ideas in columns and rows, and fill details in the appropriate squares.

How to Create an Idea Matrix

Working Thesis: Write your topic and your assertion about that topic. Your thesis is a “working” thesis because you may find that you need to circle back and revise it as you develop your supporting ideas and details. The thesis and support need to relate directly to one another.

Supporting Ideas: In this column, insert main ideas that support your assertion in the working thesis. What would convince a reader to support your assertion? These ideas will eventually become your topic sentence assertions.

Details: In each row, insert details and ideas that further develop and exemplify each supporting idea group. Note that you do not have to fill up every square of the grid.

For example, here’s an initial idea matrix a writer developed to identify possible topic sentence ideas:

The writer’s next step was to add notes in each supporting idea row for examples and details to develop that supporting idea:

After adding notes, the writer assessed her idea matrix:

- She decided that she really didn’t have much to say about fiber, so she deleted that supporting idea.

- She realized that “history of heavily-processed foods” did not directly provide an idea that supported her assertion about harming health, so she deleted that concept.

- She realized that she needed to say more about fat intake, so she added more details in that row.

- She tweaked and added details overall.

- Then she turned her supporting ideas into topic sentence assertions to create the following revised idea matrix.

The writer may have two more iterations of this essay planning matrix:

- If she decides on a certain order for her information, she may decide to re-order the rows and tweak the working thesis to indicate a particular pattern of organization.

- If she decides to support some of her assertions with research, she might add rows under each topic sentence row to house appropriate quotations or summaries.

The final idea matrix, if the writer made these two changes, might look like this:

As you might have deduced, after working progressively with an idea matrix to plan your essay, it’s a relatively easy next step to draft that essay. An idea matrix helps you identify the “bare bones” – the skeletal structure of ideas in an essay that you then can develop with examples and details. It also helps you stay on track, since you can see at a glance if there’s an idea that doesn’t directly support the assertion in the working thesis, or that doesn’t fit with the other ideas.

Here are two templates that you are welcome to download and adapt to help you write:

- Idea Matrix for Writing

- Idea Matrix for Research Writing

Idea Matrices in Other Contexts

Just as a note: Idea matrices are used in many other contexts. The following video focuses on generating ideas in a business to engage consumers. Although the context is different, you’ll see the process of using a matrix to generate ideas is the same.

- Idea Matrix for College Writing. Authored by : Susan Oaks. Project : College Writing. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- image of a matrix with colored tiles. Authored by : David Zydd. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/illustrations/square-background-color-mosaic-2724387/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- video Design Thinking: Using an Idea Matrix. Provided by : Skillsoft YouTube. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwGRc3VrBmY . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.3: Prewriting for Literature Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40503

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The first step in writing a literary analysis essay is actually completing the reading. Sometimes the professor will give you a prompt before you read. If this is the case, look for material which relates to the prompt as you read. If the professor did not give you a prompt, look for any material in the assigned reading that piques your interest or relates to class discussions. Highlight or underline any moments in the reading which stick out to you: something you don't understand, something that relates to a topic you care about, or something weird or surprising. Keeping track of patterns, themes, or literary devices is a great way to engage with a work of literature and prepare for a future discussion or essay.

Completing the Reading

One time, I was talking with my sister-in-law about her experience in nursing school. Whereas her brother had barely achieved Cs in college, she somehow maintained a 4.0, even though she was simultaneously working and caring for her two young daughters.

"What is your secret to success?" I asked.

"Actually doing the assigned readings," she laughed, "most of my peers didn't. And it showed."

As a college professor who teaches reading-heavy classes, this is not a shock to me. After all, most students taking the required writing and literature courses do not wish to become English majors. They sometimes see their literature class as a means to an end: at best, a stepping stone towards their future career; at worst, a time-suck of hoops to jump through. Also, because of today's gig economy, many students are juggling multiple jobs in addition to multiple college classes. This makes it tempting for students to want to skip the readings and just read SparkNotes. Truth be told, students who pursue this method, depending on their BSing skills, might be able to pass a literature class. But for the vast majority of students, this popular high school tactic will not work at the college level. More importantly, it means students miss out on many of the exciting benefits of diving deep into analysis, discussion, and engaging with the text.

Of course, I want my students to fall in love with the written word. I want my passion for literature to be contagious, to light students' hearts and minds on fire with a hunger for the beauty of syntax and diction and literary devices. But I also completely understand that students have limited time. Therefore, I recommend prioritizing the writing process so students can make the most efficient use of their time. In the long run, while it might seem like skipping the readings saves time, completing the readings is actually the best way for students to optimize their time. This is because a strong essay depends on a deep understanding of the literature. If the class features examinations, these almost always test students on whether they completed and understand the readings. Finally, class will be more fun for students if they understand what their peers are talking about in class discussion, and what their professor is talking about during lectures.

Students who complete the readings and annotate as they go will find it much easier to flip back through their notes to find relevant quotations and information. They usually break the readings into small, manageable chunks of twenty to thirty minutes at a time. This helps their brains absorb the information better and retain information for writing and tests.

Students skipping reading often end up performing more work when it comes to writing an essay because they will spend so much time looking up text summaries on the internet (which may or may not be accurate or pertain to the intricacies of the assignment). They will also have to go back and re-read the text to find quotations that fit their prompt. Their essays usually fail because they do not fulfill the in-depth analysis required by the assignments.

So, long story short: even the most practically-minded, time-crunched students would do well to perform the readings. And, while in pursuit of success, a previously literature-averse student might find themselves liking literature more than they thought they would. Just like watching a favorite movie or show, reading a good book can be fun and relaxing!

Active versus Passive Reading

Many students, when first reading academic material, read it like they would a timeline of Facebook or Instagram posts: not fully attentive, skimming over the material in search of something interesting. Or they might read them with full attention, but simply read without questioning or engaging with the material. The difference between a student who is successful in a literature class and a student who is not successful is often that the successful student participates in active reading.

In a literature class, students encounter a lot of literature, written by many different authors. Annotating, or taking notes on the assigned literature as you read, is a way to have a conversation with the reading. This helps you better absorb the material and engage with the text on a deeper level. There are several annotation methods. These are like tools in a student's learning utility belt. Try them all out to discover which tools or combinations of tools help you learn best!

Margin Notes & Highlighting

One of the best ways to interact with a text is to write notes as you read. Underlining and/or highlighting relevant passages, yes, but also responding to the text in the margins. For instance, if a character I love makes a bad choice (like Sydney Carton in Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities ), I will write, "Nooooo, Sydney Carton, don't sacrifice yourself for Lucie's sake!" This helps me remember the events of the plot. Many students also find it helpful to summarize each chapter or section of the literature as they read it. For example, a student said it was helpful for them to draw a picture representing every stanza of "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" by William Wordsworth to help them understand what was being said. Other ideas include:

- Circling unfamiliar words

- Writing questions in the margins

- Color-coded highlighting to track various literary devices (i.e., blue for metaphors, pink for symbolism, and so forth)

Sticky Notes

For students who would like to sell their textbooks back to the bookstore, writing notes in the margins might not be a practical choice, as it may devalue the textbook or the bookstore may refuse to take it back. For these students, I recommend using sticky notes instead. If sticky notes are cost-prohibitive, most colleges have plenty of scrap paper students can use as bookmarks to stick between pages. This is also an eco-friendly way to re-use paper!

Reading Journal

Another option many students find helpful is keeping a reading journal. Students can write notes in their journals as they read. This helps students keep track of readings and materials in a chronological fashion. Just like when annotating the text directly or upon sticky notes, the most effective use of a reading journal, for learning purposes, is going to be active engagement with the text rather than passive absorption. That is, try to summarize the plot of what you read every time you read. Also, ask questions about the text. If you can record quotes and paraphrase along with in-text parenthetical citations (i.e., the page number where you found the material), this will optimize your time because you already have quotes ready to go when you write an essay!

Example of an Annotated Passage

Using the guidelines above, let's consider this excerpt from a scholarly article by Jacob Michael Leland, "'Yes, That is a Roll of Bills in My Pocket': The Economy of Masculinity in The Sun Also Rises."

A great deal of critical attention has been paid to masculine agency and its displacement in Ernest Hemingway's fiction. The story is familiar by now: the Hemingway hero loses some version of his maleness to the first World War and he replaces it with a tool—in Upper Michigan, a fishing rod or a pocket knife; in Africa, a hunting rifle—a new object that emblematizes his mastery over his surroundings and whose status as a fetishized commodity and Freudian symbolic significance is something less than subtle. In The Sun Also Rises , this pattern repeats itself, but with important differences that arise from the novel's cosmopolitan European setting. Mastery over the elements, here, has more to do with economic agency and control over social relationships than with nature and survival. The stakes are different, too; in the modern European city, the Hemingway hero recovers not only masculinity but also American identity in social and sexual interaction. (37)

In researching The Sun Also Rises for a project, Ling Ti found Leland's article. What follows is her annotated copy of the above excerpt:

Reflecting on Assigned Literature

Studies show reflecting on reading is one of the best ways to learn. This is called metacognition, or thinking about thinking. It is a way to keep track of the knowledge you have learned as you go. Students who reflect on their reading and learning tend to, as a whole, perform better on essays and examinations. So how can you take advantage of this skill?

If you have a prompt, choose a prompt and read through the assigned literature again, noting any quotes which may relate to the assigned topic. It is recommended at this point that you keep track of your observations in a document: either on a computer (Word, Google Docs) or on a physical piece of paper. Write down any quotations along with page numbers (fiction, nonfiction), line numbers (poem), or act, scene, line numbers (drama). This way, you have all potential evidence in one place, and it makes for easy in-text citations when it comes to knitting the evidence together to form an essay. In fact, it is highly recommended that students start an informal Works Cited page to keep track of every source consulted. This makes it much easier to avoid plagiarism by practicing ethical citation habits. For more information about citations, please see the Citations and Formatting Chapter.

Start with a hypothesis or focus but be willing to refine, adjust, or completely discard it if new evidence refutes it. An essay is not a stagnant piece, but a living, breathing thought experiment. Many students feel reluctant to change their thesis or major parts of their essays because they are afraid it means the previous writing was wasted. As a professional writer, editor, and scholar, I want to clue students in on a secret:

There is no such thing as wasted writing.

Even writing that does not end up in the final draft is worthwhile because it is a chance to experiment with ideas. It helps students find a path toward stronger ideas. Just like a gardener might allow branches of a tree to grow to see which ones bear flowers and fruit and then prune the weak, unproductive branches to make the plant stronger and more beautiful, so too must a writer be willing to cut out branches of reasoning which no longer serve the essay. But before you know which ideas or thoughts are worth pursuing, you first have to give them space to grow. You never know what idea branches might prove fruitful!

Contributors and Attributions

- Adapted from "Reading Like a Professional" in Writing and Literature: Composition as Inquiry, Learning, Thinking, and Communication by Dr. Tanya Long Bennett of the University of North Georgia, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Daytona State College

- DSC Library

Writing Strategies and Grammar

- Prewriting/Outlining

- Writing Prompts

- Common Topics

- Writer's Block

- Brainstorming

- Paragraph Structure

- Thesis Statements

- Rhetoric Defined

- Understanding Citations

- Transitions

- Revision Process

- Parts of Speech

- Improve Grammar

- Complete Sentences

- Punctuation

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Writing Center Homepage

- WC Blog This link opens in a new window

Why Prewrite?

The goal of prewriting is to make starting the essay easier. It gives you time to develop your ideas and structure your essay. Without taking time to prewrite, you’ll have to plan and draft at the same time, which can lead to disorganized ideas. Keep in mind that anything you prewrite can be changed at any point in the essay process.

Make a Claim

A claim is a statement you make about a topic. The claim should state your essay’s main goal or argument and will later be molded into the thesis statement.

- Standardized tests should be discontinued.

State Supporting Details

Now, list the reasons (“supporting details”) that have led you to make this claim. Your supporting details should be strong enough to be expanded into full paragraphs and should prove that your claim is correct, necessary to read about, and important to your audience.

- Detail 1: They place unnecessary stress on teachers and students

- Detail 2: They favor test takers with socio-economic advantages

- Detail 3: They are not accurate measurements of learning

Make a Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is a direct response to the essay prompt. It is a combination of the essay’s claim and supporting details. Keep in mind, the thesis statement should be the last sentence of the introduction paragraph.

- Thesis Statement Example: Teachers and students are put under unnecessary pressure to pass standardized tests, which are not an accurate measurement of learning and only fill the test making companies’ pockets.

Plan Your Details

Now that you have your thesis statement, describe how you’re going to present the information in each paragraph. Everyone has their own way of outlining, so you can include as little or as much information as you wish. Considering these points is a good start:

- State the topic sentence

- List what research, examples, or evidence supports that paragraph

- Explain the relevance of the previous step

- Think about how the paragraph relates to the thesis

- Consider transitions between paragraphs

Once you have an assignment for an essay, prior to coming up with content for it, it’s important to critically think about the assignment at hand.

Who is the intended audience?

What’s the purpose?

Keep these under consideration as you organize the ideas that result from brainstorming initially. As you develop your arguments and subtopics, one question to always keep in the back of your mind is: Does this support my thesis? Below are a few methods and ideas that can help you outline the essay.

Formal Outlines: Create an outline in a traditional method. Using headings and subheadings (either with bullets or numbers) write out a basic structure of the essay you have in mind. You can put on paper what arguments and sub-arguments you will have, and you can see boundaries between your ideas. Don’t marry yourself to the way in which it’s initially structured, because it may change once you draft, but formal outlines are great for getting a visual on ideas and relationships within the paper’s topic.

Story-telling: Write Creatively. We sometimes ignore how we first learned reading and writing skills: through story-telling. Sometimes the best way to approach an academic paper is to think of it in terms of ‘beginning-middle-end,’ Where does your topic begin? Where do you want it to end? How can it have a ‘happily ever after’ so it sums up nicely? By thinking in terms of chronological storytelling, you give your mind a method of writing that everyone has had a lifetime of experience in. We encourage you to format this in a structured outline style, but this focuses on the entirety of the essay rather than each paragraph.

Full Sentence Outlining: For the Writer in you! The outlining structure for full sentence outlining is essentially combining the story-telling aspects of outlining with formal outlines. Rather than jotting down ideas for content, some students prefer to write the basic sentences they will eventually include in the essay. If it helps your mind to write down outlines in full sentences, use whatever method works!

- << Previous: Planning & Drafting

- Next: Paragraph Structure >>

- Last Updated: Oct 27, 2023 2:23 PM

- URL: https://library.daytonastate.edu/Writing

Trending Post : 12 Powerful Discussion Strategies to Engage Students

8 Meaningful Essay Prewriting Activities

Teaching writing? Sometimes students shut down before they write a single word. Teachers can address this dilemma by making the brainstorming process meaningful. How? Engage students through differentiation and scaffolding. When students are provided with choices, they feel less helpless, become more confident, and produce better compositions. Try using one or more of these essay prewriting activities to generate solid ideas and set your students up for success.

1. USE LOCATION TO INSPIRE

When authors experience writer’s block, one of the strategies they use to overcome the hurdle is to change their location. Allowing students to write in the library, outside, or at a coffee shop (field trip!) can reap results worthy of reading. Alternate settings are the perfect and simplest option for differentiating prewriting. Plus, almost all prewriting strategies can adapt to an outdoor location.

2. MODEL BRAINSTORMING & PREWRITING

Regardless of whether I’m working with advanced students or struggling writers, all students benefit from class brainstorming sessions where the teacher models expectations and scaffolds students from teacher-led instruction to guided practice and, finally, to independence.

What might this look like? After assigning an essay, the first order of business is to show students how to begin. In doing so, collectively brainstorm topics , research to find support, and fill out graphic organizers. Doing this as a class the first time through is less overwhelming for many students, and it helps students follow along if they have step-by-step directions that they can refer back to later.

3. LIMIT FRUSTRATION VIA CONFERENCES

Some students have difficulty transcribing their ideas onto paper and organizing their thoughts logically. In these instances, it’s necessary to talk students through their prewriting. As you discuss ideas one-on-one, have students take notes on their prewriting materials.

For something new and unique, give students Play-Doh or another manipulative and ask them to create their response to a topic. As an accommodation, teachers or peer partners can jot down the information as students think aloud about what they would like to write.

4. DIFERENTIATE GRAPHIC ORGANIZERS

You might be surprised to find that simply offering students several different options for how they would like to complete their prewriting increases motivation. Possibilities might include, but are not limited to, color-coded graphic organizers , flow charts, webs, trees, outlines, journaling, sketch notes, mind mapping, acronyms , and free writing.

When modeling prewriting, try demonstrating with different strategies. As students begin to brainstorm for their own topic, allow them freedom to choose which prewriting approach they’d like to use.

5. LET THEM READ THE GOOD STUFF

As Kelly Gallagher writes, “ If we want kids to write, we have to take them swimming in the genre first. Start by wading before taking them to the deep end.” An integral facet of the brainstorming process should be allowing students to get knee deep in examples of the genre we expect them to write. Teachers can use examples they have written, essays written by previous students, or even published pieces and novels, depending on the genre of study.

Not sure where to start? Illinois Literacy in Action has some great lists for argumentative, informative, and narrative mentor texts. Here are some of the models I use with students.

6. PROVIDE TIME TO DISCUSS WITH PEERS

Students can learn quite a bit from one other. As a meaningful prewriting activity, give them time to discuss their ideas with a peer or a small group, and listen to the feedback they offer. Not only does this strategy allow students valuable time to mull over their ideas, but also it provides an avenue for teachers to teach students how to have meaningful and productive discussions about writing.

7. USE CAROUSELS TO GENERATE TOPICS

One of the best ways I’ve found to differentiate prewriting for ability levels and interests is to have lengthy class discussions about possible topics. Generally, I lead these conversations, but I have also found success in having students participate in carousel activities.

To start, hang large sheets of butcher paper around the room. Then, brainstorm several possible topics for the essay. Write those topics at the top of the papers. Following, students divide into small groups and work together to devise possible angles they might use to approach each topic. In doing so, they are writing questions as well as possible thesis statements and supporting ideas. Sometimes they come up with related topics as well.

Students move from station to station and add their thoughts. To wrap up, each small group is assigned to present ideas for a given topic to the whole group.

8. SCAFFOLD RESEARCH

Writing a research paper? A successful means of engaging students is by providing an appropriate anticipatory set. Capture students’ interest in topics by incorporating source material and discussing it as a group. Showing them related video clips, reading high-interest articles as a class, and bringing in guest speakers for the subject are all ideal approaches. Interest is a game-changer when it comes to writing.

If students are still struggling with the research element of brainstorming, scaffold their experience by providing a couple articles to get them started. Here are 14 additional scaffolding strategies for building confidence and increasing students’ success with writing.

Writing can be challenging and frustrating, or it can be freeing and therapeutic. By scaffolding and differentiating the prewriting process, we reduce the likelihood that students will struggle. Prewriting activities needn’t be fancy or complex to be effective and meaningful. Click here to access a free argumentative prewriting resource to scaffold your students’ prewriting experience.

[sc name=”mailchimp1″]

Get the latest in your inbox!

Prewriting an Essay

What is the prewriting stage, six prewriting steps:.

Your Best College Essay

Maybe you love to write, or maybe you don’t. Either way, there’s a chance that the thought of writing your college essay is making you sweat. No need for nerves! We’re here to give you the important details on how to make the process as anxiety-free as possible.

What's the College Essay?

When we say “The College Essay” (capitalization for emphasis – say it out loud with the capitals and you’ll know what we mean) we’re talking about the 550-650 word essay required by most colleges and universities. Prompts for this essay can be found on the college’s website, the Common Application, or the Coalition Application. We’re not talking about the many smaller supplemental essays you might need to write in order to apply to college. Not all institutions require the essay, but most colleges and universities that are at least semi-selective do.

How do I get started?

Look for the prompts on whatever application you’re using to apply to schools (almost all of the time – with a few notable exceptions – this is the Common Application). If one of them calls out to you, awesome! You can jump right in and start to brainstorm. If none of them are giving you the right vibes, don’t worry. They’re so broad that almost anything you write can fit into one of the prompts after you’re done. Working backwards like this is totally fine and can be really useful!

What if I have writer's block?

You aren’t alone. Staring at a blank Google Doc and thinking about how this is the one chance to tell an admissions officer your story can make you freeze. Thinking about some of these questions might help you find the right topic:

- What is something about you that people have pointed out as distinctive?

- If you had to pick three words to describe yourself, what would they be? What are things you’ve done that demonstrate these qualities?

- What’s something about you that has changed over your years in high school? How or why did it change?

- What’s something you like most about yourself?

- What’s something you love so much that you lose track of the rest of the world while you do it?

If you’re still stuck on a topic, ask your family members, friends, or other trusted adults: what’s something they always think about when they think about you? What’s something they think you should be proud of? They might help you find something about yourself that you wouldn’t have surfaced on your own.

How do I grab my reader's attention?

It’s no secret that admissions officers are reading dozens – and sometimes hundreds – of essays every day. That can feel like a lot of pressure to stand out. But if you try to write the most unique essay in the world, it might end up seeming forced if it’s not genuinely you. So, what’s there to do? Our advice: start your essay with a story. Tell the reader about something you’ve done, complete with sensory details, and maybe even dialogue. Then, in the second paragraph, back up and tell us why this story is important and what it tells them about you and the theme of the essay.

THE WORD LIMIT IS SO LIMITING. HOW DO I TELL A COLLEGE MY WHOLE LIFE STORY IN 650 WORDS?

Don’t! Don’t try to tell an admissions officer about everything you’ve loved and done since you were a child. Instead, pick one or two things about yourself that you’re hoping to get across and stick to those. They’ll see the rest on the activities section of your application.

I'M STUCK ON THE CONCLUSION. HELP?

If you can’t think of another way to end the essay, talk about how the qualities you’ve discussed in your essays have prepared you for college. Try to wrap up with a sentence that refers back to the story you told in your first paragraph, if you took that route.

SHOULD I PROOFREAD MY ESSAY?

YES, proofread the essay, and have a trusted adult proofread it as well. Know that any suggestions they give you are coming from a good place, but make sure they aren’t writing your essay for you or putting it into their own voice. Admissions officers want to hear the voice of you, the applicant. Before you submit your essay anywhere, our number one advice is to read it out loud to yourself. When you read out loud you’ll catch small errors you may not have noticed before, and hear sentences that aren’t quite right.

ANY OTHER ADVICE?

Be yourself. If you’re not a naturally serious person, don’t force formality. If you’re the comedian in your friend group, go ahead and be funny. But ultimately, write as your authentic (and grammatically correct) self and trust the process.

And remember, thousands of other students your age are faced with this same essay writing task, right now. You can do it!

Cramming for an exam isn’t the best way to learn – but if you have to do it, here’s how

Senior Teaching Fellow in Education, University of Strathclyde

Disclosure statement

Jonathan Firth does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Strathclyde provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Around the country, school and university students are hitting the books in preparation for exams. If you are in this position, you may find yourself trying to memorise information that you first learned a long time ago and have completely forgotten – or that you didn’t actually learn effectively in the first place.

Unfortunately, cramming is a very inefficient way to properly learn. But sometimes it’s necessary to pass an exam. And you can incorporate what we know about how learning works into your revision to make it more effective.

Read more: Exams: seven tips for coping with revision stress

A great deal of research evidence on how memory works over time shows that we forget new information very quickly at first, after which the process of forgetting slows down.

In practice, this means that very compressed study schedules lead to a catastrophic amount of forgetting.

A better option is to space out learning a particular topic more gradually and over a longer period. This is called the “spacing effect” and it leads to skills and knowledge being retained better, and for longer.

Research has found that we remember information better when we leave a gap of time between first studying something and revisiting it, rather than doing so straight away. This even works for short timescales – a delay of a few seconds when trying to learn a small piece of information, such as a pair of words, for instance. And it also works when the delay between study sessions is much longer .

In the classroom , spacing out practice could mean reviewing and practising material the next day, or delaying homework by a couple of weeks, rather than revisiting it as soon as possible. As a rule, psychologists have suggested that the best time to re-study material is when it is on the verge of being forgotten – not before, but also not after.

But this isn’t how things are learned across the school year. When students get to exam time, they have forgotten much of what was previously studied.

Better cramming

When it comes to actually learning – being able to remember information over the long term and apply it to new situations – cramming doesn’t work. We can hardly call it “learning” if information is forgotten a month later. But if you need to pass an exam, cramming can lead to a boost in temporary performance. What’s more, you can incorporate the spacing effect into your cramming to make it more efficient.

It’s better to space practising knowledge of a particular topic out over weeks, so if you have that long before a key exam, plan your revision schedule so you cover topics more than once. Rather than allocating one block of two hours for a particular topic, study it for one hour this week and then for another hour in a week or so’s time.

If you don’t have that much time, it’s still worth incorporating smaller gaps between practice sessions. If your exam is tomorrow, practice key topics in the morning today and then again in the evening.

Learning is also more effective if you actively retrieve information from your memory, rather than re-reading or underlining your notes. A good way to do this, incorporating the spacing effect, is to take practice tests. Revise a topic from your notes or textbook, take a half-hour break, and then take a practice test without help from your books.

An even simpler technique is a “brain dump” . After studying and taking a break, write down everything you can remember about the topic on a blank sheet of paper without checking your notes.

Change the way we teach

A shift in teaching practices may be needed to avoid students having to cram material they only half-remember before exams.

But my research suggests that teachers tend to agree with the idea that consolidation of a topic should happen as soon as possible, rather than spacing out practice in ways that would actually be more effective.

Teachers are overburdened and make heroic efforts with the time they have. But incorporating the spacing effect into teaching needn’t require radical changes to how teachers operate. Often, it’s as simple as doing the same thing on a different schedule .

Research has shown the most effective way to combine practice testing and the spacing effect is to engage in practice testing in the initial class, followed by at least three practice opportunities at widely spaced intervals. This is quite possible within the typical pattern of the school year.

For example, after the initial class, further practice could come via a homework task after a few days’ delay, then some kind of test or mock exam after a further gap of time. The revision period before exams would then be the third opportunity for consolidation.

Building effective self-testing and delayed practice into education would spell less stress and less ineffective cramming. Exam time would be for consolidation, rather than re-learning things that have been forgotten. The outcome would be better long-term retention of important knowledge and skills. As a bonus, school students would also gain a better insight into how to study effectively.

- Motivate me

Research Fellow

Senior Research Fellow - Women's Health Services

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Short Narrative Essay

Short narrative essay generator.

Everyone finds it interesting to tell stories about their lives or about someone else’s. Through those stories, we can get lessons which we can apply in our daily lives. This is what a narrative essay is all about. Let’s go back to your experiences when you were still in grade school. Your teacher would often ask you to write about your favorite experiences especially during Christmas season and summer vacation.

Some people would mistakenly identify a narrative essay as equally the same as a descriptive essay . They are totally different from each other, yet both of them are forms of academic writing . Look into this article to learn more about narrative essays.

What is Short Narrative Essay?

A short narrative essay is a brief piece of writing that tells a story, usually focusing on a particular experience, event, or moment. It follows a narrative structure, involving characters, a setting, a plot, and a conclusion, aiming to engage the reader through vivid descriptions and storytelling techniques within a concise format.

Best Short Narrative Essay Examples?

Title: The Summer Adventure

The scorching sun bore down on the dusty road as we embarked on our summer adventure. Packed into the old, battered car, my family and I set off for the great outdoors. The air hummed with anticipation, echoing our excitement for the unknown.

As we traversed winding roads, the landscape unfolded like a painting. Rolling hills adorned with emerald-green trees greeted us, promising the allure of exploration. The scent of pine wafted through the open windows, mingling with laughter and the crackling excitement of adventure.

Our destination? A secluded lakeside campsite embraced by nature’s serenity. The promise of tranquil waters and starlit nights ignited our spirits. Upon arrival, we pitched our weathered tent, a ritual signaling the beginning of our escape from routine.

Days melted into each other, filled with hikes through dense forests, dips in cool, crystal-clear waters, and evenings spent around crackling campfires. We discovered hidden trails, stumbled upon secret meadows, and marveled at nature’s splendid orchestra of sounds and colors.

But amidst the beauty lay unexpected challenges. Unforgiving storms threatened our haven, testing our resilience. Yet, huddled together, we found solace in each other’s company, discovering strength in unity.

As the final sun dipped behind the horizon, casting its golden glow upon the rippling waters, a bittersweet sensation enveloped us. The adventure had drawn to a close, leaving behind cherished memories etched in our hearts.

Reluctantly, we packed our belongings, bidding farewell to the tranquil haven that had nurtured us. With weary but contented hearts, we embarked on the journey back, carrying not just souvenirs but a treasure trove of shared experiences and the promise of future escapades.

The car rolled away from the lakeside, but the echoes of laughter, the scent of pine, and the warmth of togetherness lingered, reminding us of the magical summer adventure that had woven us closer together.

11+ Short Narrative Essay Examples

1. short narrative essay examples.

- Google Docs

Size: 27 KB

2. Narrative Essay Examples

Size: 23.8 KB

3. Short Narrative Essay Template

Size: 465 KB

4. Short Narrative Essay

Size: 117 KB

5. Short Narrative Essay Format

Size: 107 KB

6. The Storm Short Narrative Essay

Size: 48 KB

7. Five-Paragraph Short Narrative Essay

Size: 29 KB

8. Short Narrative Writing Essay

Size: 177 KB

9. College Short Narrative Essay

Size: 589 KB

10. High School Short Narrative Essay Examples

Size: 114 KB

11. College Short Narrative Essay Examples

Size: 130 KB

12. Personal Short Narrative Essay Examples

Size: 105 KB

What is a Narrative Essay?

A narrative essay is a type of academic writing that allows you to narrate about your experiences. This follows a certain outline just like what we have observed in argumentative essays , informative essays and more. The outline consists of the introduction, body paragraph and conclusion.

This is a type of essay that tells a story either from the point of view of the author or from the personal experience of the author. It should also be able to incorporate characteristics such as the ability to make and support a claim, develop specific viewpoint, put conflicts and dialogue in the story, and to use correct information. You may also see personal narrative essay examples & samples

The purpose of a narrative essay is to be able to tell stories may it be real or fictional. To enable us to write a perfect narrative essay, the author should include the necessary components used for telling good stories, a good climax, setting, plot and ending.

How To Write a Narrative Essay?

Compared to all types of academic essay , the narrative essay is the simplest one. It is simply written like the author is just writing a very simple short story. A typical essay has only a minimum of four to five paragraphs contain in the three basic parts: introduction, body paragraph and conclusion. A narrative essay has five elements namely the characters, plot, conflict, setting and theme.

Plot – this tells what happened in the story or simply the sequence of events. There are five types of plot: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution. The exposition is the an information that tells about background of the story. It can be about the character, the setting, events, etc. Rising action is where the suspense of a story begins. It helps build toward the climax of a story. Climax is the most intense part of the story. Falling action happens after the climax when it is already almost the end of the story. Resolution is the part where the problem has already been resolved.

Characters – it is the person or other being that is a part of the narrative performs an action or speak a dialogue .

Conflict – this is the struggle or the problem that is faced by the characters of the story. This can be an external conflict and an internal conflict. An external conflict is a type of problem that is experienced in the external world. An internal conflict is the type of conflict that refers to the characters’ emotions and argument within itself.

Setting – this is knowing where and when the story takes place. This can be a powerful element because it makes the readers feel like they are the characters in the story.

Theme – this is what the author is trying to convey. Examples of a theme are romance, death, revenge, friendship, etc. It is the universal concept that allows you to understand the whole idea of the story.

How to write a short narrative essay?

- Select a Theme or Experience: Choose a specific event, moment, or experience that you want to narrate.

- Outline the Story: Plan the narrative by outlining the key elements – characters, setting, plot, and a clear beginning, middle, and end.

- Engaging Introduction: Start with a hook to captivate readers’ attention, introducing the setting or characters involved.

- Develop the Plot: Write body paragraphs that progress the story logically, describing events, actions, and emotions, using vivid details and sensory language to immerse readers.

- Character Development: Focus on character traits, emotions, and reactions to make the story relatable and engaging.

- Climax and Resolution: Build tension towards a climax, followed by a resolution or lesson learned from the experience.

- Concise Conclusion: Conclude the essay by summarizing the experience or reflecting on its significance, leaving a lasting impression on the reader.

- Revise and Edit: Review the essay for coherence, clarity, grammar, and punctuation, ensuring it flows smoothly.

What are the 3 parts of a narrative essay?

- Introduction: Sets the stage by introducing the story’s characters, setting, and providing a glimpse of the main event or experience. It often includes a hook to capture the reader’s attention.

- Body: Unfolds the narrative, presenting the sequence of events, actions, emotions, and details that drive the story forward. It develops the plot, characters, and setting.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the narrative, reflecting on the significance of the experience or event, and often delivers a lesson learned or leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

How do you start a narrative essay with examples?

- ” ‘Are we there yet?’ echoed in my ears as our family car trudged along the endless highway, marking the beginning of our unforgettable summer road trip.”

- “The sun dipped low on the horizon, casting a warm, golden hue over the serene lake. It was there, amidst the tranquil waters, that my adventure began.”

- “The deafening roar of applause faded as I stepped onto the stage, my heart racing with anticipation. Little did I know, that moment would change everything.”

- “Looking back, it all started with a single decision. That decision, made in a moment of uncertainty, led to a series of events that transformed my life.”

- “The scent of freshly baked cookies wafted through the air, mingling with the joyous laughter of children. It was a typical afternoon, until an unexpected visitor knocked on our door.”

How do you start a narrative introduction?

You may start by making the characters have their conversation or by describing the setting of the story. You may also give background information to the readers if you want.

What makes a good narrative?

A good narrative makes the readers entertained and engage in a way that they will feel like they are becoming a part of the narrative itself. They should also be organized and should possess a good sequence of events.

How many paragraphs are there in personal narratives?

Usually, there are about five paragraphs.

How many paragraphs are in a short narrative essay?

A short narrative essay typically comprises an introductory paragraph introducing the story, three to four body paragraphs unfolding the narrative, and a concluding paragraph summarizing the experience.

How long is a short narrative essay?

A short narrative essay typically ranges from 500 to 1500 words, aiming to convey a concise and focused story or experience within a limited word count.

Narrative essays are designed to express and tell experiences making it an interesting story to share. It has the three basic parts and contains at least five elements. If you plan to create a good narrative essay, be sure to follow and assess if your narrative has all the characteristics needed to make it sound nice and pleasing.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Write a Short Narrative Essay on a memorable moment with your family.

Create a Short Narrative Essay about a lesson learned from a mistake.

What Is a Capstone Project vs. Thesis

As students near the end of their academic journey, they encounter a crucial project called the capstone – a culmination of all they've learned. But what exactly is a capstone project?

This article aims to demystify capstone projects, explaining what they are, why they matter, and what you can expect when you embark on this final academic endeavor.

Capstone Project Meaning

A capstone project is a comprehensive, culminating academic endeavor undertaken by students typically in their final year of study.

It synthesizes their learning experiences, requiring students to apply the knowledge, skills, and competencies gained throughout their academic journey. A capstone project aims to address a real-world problem or explore a topic of interest in depth.

As interdisciplinary papers, capstone projects encourage critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity. They allow students to showcase their mastery of their field of study and demonstrate their readiness for future academic or professional pursuits.

Now that we’ve defined what is a capstone project, let’s discuss its importance in the academic landscape. In case you have short-form compositions to handle, simply say, ‘ do my essay for me ,’ and our writers will take care of your workload.

Why Is a Capstone Project Important

A capstone project is crucial because it allows students to combine everything they've learned in school and apply it to real-life situations or big problems.

It's like the ultimate test of what they know and can do. By working on these projects, students get hands-on experience, learn to think critically and figure out how to solve tough problems.

Plus, it's a chance to show off their skills and prove they're ready for whatever comes next, whether that's starting a career or going on to more schooling.

Never Written Capstones Before?

Professional writers across dozens of subjects can help you right now.

What Is the Purpose of a Capstone Project

Here are three key purposes of a capstone project:

%20(1).webp)

Integration of Knowledge and Skills

Capstones often require students to draw upon the knowledge and skills they have acquired throughout their academic program. The importance of capstone project lies in helping students synthesize what they have learned and apply it to a real-world problem or project.

This integration helps students demonstrate their proficiency and readiness for graduation or entry into their chosen profession.

Culmination of Learning

Capstone projects culminate a student's academic journey, allowing them to apply theoretical knowledge to real-world scenarios.

tackling a significant project or problem, students demonstrate their understanding of concepts and their ability to translate them into practical solutions, reinforcing their learning journey.

Professional Development

Capstone projects allow students to develop skills relevant to their future careers. These projects can also be tangible examples of their capabilities to potential employers or graduate programs.

Whether it's conducting research, presenting findings, or collaborating with peers, students gain valuable experience that enhances their professional readiness.

Types of Capstone Projects

Capstones vary widely depending on the academic discipline, institution, and specific program requirements. Here are some common types:

What Is the Difference Between a Thesis and a Capstone Project

Here's a breakdown of the key differences between a thesis and a capstone project:

How to Write a Capstone Project

Let's dive into the specifics with actionable and meaningful steps for writing a capstone project:

1. Select a Pertinent Topic

Identify a topic that aligns with your academic interests, program requirements, and real-world relevance. Consider issues or challenges within your field that merit further exploration or solution.

Conduct thorough research to ensure the topic is both feasible and significant. Here are some brilliant capstone ideas for your inspiration.

2. Define Clear Objectives

Clearly articulate the objectives of your capstone project. What specific outcomes do you aim to achieve?

Whether it's solving a problem, answering a research question, or developing a product, ensure your objectives are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

3. Conduct Comprehensive Research

Dive deep into existing literature, theories, and empirical evidence related to your chosen topic. Identify gaps, controversies, or areas for further investigation.

Synthesize relevant findings and insights to inform the development of your project and provide a solid foundation for your analysis or implementation.

4. Develop a Structured Plan

What is a capstone project in college without a rigid structure? Outline a comprehensive plan for your capstone project, including key milestones, tasks, and deadlines.

Break down the project into manageable phases, such as literature review, data collection, analysis, and presentation. Establish clear criteria for success and regularly monitor progress to stay on track.

5. Implement Methodological Rigor

If your project involves research, ensure methodological rigor by selecting appropriate research methods, tools, and techniques.

Develop a detailed research design or project plan that addresses key methodological considerations, such as sampling, data collection, analysis, and validity. Adhere to ethical guidelines and best practices throughout the research process.

6. Analyze and Interpret Findings

Analyze your data or findings using appropriate analytical techniques and tools. Interpret the results in relation to your research questions or objectives, highlighting key patterns, trends, or insights.

Critically evaluate the significance and implications of your findings within the broader context of your field or industry.

7. Communicate Effectively