Dollars and sense: The case for teaching personal finance

Americans aren’t good at managing their money — and there are signs that the problem is getting worse.

Already saddled with record levels of student debt, young adults today, for example, are even more unlikely to monitor their credit card debt and bank balances. Some people trick themselves into thinking that store refunds or anything less than $5 amount to free money . And too many people pay for online subscriptions they don’t use.

Thanks to the pioneering work of Stanford economist Annamaria Lusardi , numerous studies show how little people know about money. For two decades, Lusardi has been tracking financial literacy rates using three basic questions that she helped design and are now used as a standard measure around the world.

Her latest analysis of how Americans responded to those three questions in 2021 underscores their lack of financial know-how.

Only 53.1 percent of respondents demonstrated an understanding of how inflation works as prices on everything from cereal and cars were spiking. About two-thirds (69.4 percent) knew how to do a simple interest-rate calculation, but only 41.5 percent understood how, when it comes to investment risks, mutual funds are generally safer investments than a single company’s stock.

In all, just 28.5 percent of survey participants answered all three questions correctly, while the rest either got them wrong, or indicated they didn’t know.

The results are especially troubling as methods of managing money have evolved, says Lusardi, a globally recognized expert on personal finance who joined Stanford in September as a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) and director of the new Initiative for Financial Decision-Making. Workers now shoulder more of their retirement planning; consumers quickly and easily move money using their mobile phones; and investors make increasingly complex decisions.

“The world is changing really fast and we just expect people to have the skills to make financial decisions that have critical lifelong impacts,” says Lusardi, who is also a professor of finance (by courtesy) at the Graduate School of Business (GSB).

High rates of financial illiteracy are also problematic, she says, given today’s heightened economic uncertainty and growing wealth inequality. Respondents who were young, less educated, female, or not employed scored the lowest. Black Americans and Hispanics were also among the least financially literate.

A global pattern of illiteracy

Financial illiteracy, it turns out, is pervasive around the world, according to a newly published global analysis in the Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing . Whether they are in a Nordic country with strong education systems, like Finland, or in a Latin American country, like Peru, which experienced inflation in 1990 upwards of 10,000 percent, most people don’t understand how money works, says Lusardi. And just like in the United States, the least knowledgeable tend to be women, racial minorities, the least-educated, and the unemployed.

Lusardi’s latest U.S. analysis — co-authored with Jialu Streeter , the executive director and a senior research scholar at SIEPR — is part of a special edition of the journal that includes analyses of 16 countries. Each study in the issue is based on the results of the “Big Three” questions that Lusardi and her longtime collaborator, economist Olivia Mitchell of The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, crafted 20 years ago.

In 2011, Lusardi oversaw and contributed to a similar series of country comparisons — which yielded similar results and appeared in the Journal of Pension Economics & Finance .

“Financial illiteracy has been and continues to be a global phenomenon,” says Lusardi, who is one of the founders and inaugural editors of the Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing , published by Cambridge University Press .

Why the ABCs of money matters

Beyond measuring and analyzing financial literacy rates, Lusardi’s extensive research has found how people who understand basic financial concepts are better at managing money. They save more for retirement, make smarter investment decisions, and manage their debts more effectively. Lusardi’s latest study shows that people who are financially literate are more likely to have money on hand to weather at least the early stages of an economic shock like a pandemic.

Lusardi has also shown that people think they know more about personal finance than they actually do, which she says makes them even more vulnerable to poor decision-making.

Stanford’s commitment to improving financial literacy is a key reason Lusardi says she joined The Farm. In addition to the Initiative for Financial Decision-Making — a collaboration between SIEPR, the GSB, and the Department of Economics in the School of Humanities and Sciences — Lusardi continues to serve as academic director of the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center , which she founded in 2011. Prior to Stanford, Lusardi was the University Professor of Economics and Accountancy at The George Washington University.

The Big Three as global standard

In Lusardi, Stanford gains a leader in establishing financial literacy as a specialty within the field of economics.

Lusardi’s contributions to the field began in 2004, when The University of Michigan’s closely watched Health and Retirement Study added the so-called Big Three to a module dedicated to financial literacy and retirement planning. Then, in 2009, the financial education arm of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, which helps provide oversight of registered securities brokers and brokerage firms, began incorporating the same measures in its triennial survey of roughly 25,000 Americans.

Since then, other organizations, including central banks around the world, have integrated the Big Three into their respective assessments of household finances.

The underlying datasets in these surveys differ, but the results have uniformly shown that most people don’t understand how money, or financial systems broadly, functions, Lusardi says. In the U.S., this remained the case even after the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009 — the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression — buffeted household finances.

“The continuous surprise is just how low financial literacy is in the United States and around the world,” says Lusardi, whose policy work includes advising the U.S. Treasury, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and chairing the Italian Financial Education Committee in charge of designing a national strategy for financial literacy.

Solutions in education

To Lusardi, the answer to financial illiteracy lies in providing people with a basic education on the ABCs of personal finance.

“Developing personal finance skills is as important as learning how to read and write,” says Lusardi, who has been teaching financial literacy to undergraduate and graduate students for more than a decade. In fact, her move to Stanford is rooted in her experience working with SIEPR’s Michael Boskin and John Shoven to organize the first annual Teaching Personal Finance Conference in 2022.

“I’m not talking about expecting people to become Warren Buffet,” she says. “I’m talking about teaching people, especially the young, how to make savvy financial decisions. For first-generation or low-income students, it often means talking about topics they seldom discuss with their parents.”

Even as personal finance education has become somewhat of a cottage industry, results are mixed at best. Instructors, Lusardi says, often lack training and students tend to forget what they learn. In a 2014 journal publication , Lusardi and Mitchell noted that lack of sufficient funding or teacher training in financial education are still an issue; in a follow-up paper published this past fall, however, they said there’s reason for optimism.

More than half of U.S. states, for example, have added personal finance instruction as a high school graduation requirement. Universities, including Stanford, are now offering personal finance courses. Employers, too, are recognizing that financial anxiety hurts employee productivity and are sponsoring personal finance lessons in the workplace.

“Financial literacy education is really accelerating,” Lusardi says. “We’re finally seeing things turn around and, to me, that’s a very positive result.”

This story was updated on Feb. 15, 2024 with the new official name of Stanford's Initiative for Financial Decision-Making.

More News Topics

Facebook went away. political divides didn't budge..

- Research Highlight

- Politics and Media

Adrien Auclert appointed as an economic advisor to French government

- Awards & Appointments

- Taxes and Public Spending

- Global Development and Trade

IMF's Gita Gopinath: Geopolitics and its impact on global trade and the dollar

- Money and Finance

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Planet Money

- Planet Money Podcast

- The Indicator Podcast

- Planet Money Newsletter Archive

- Planet Money Summer School

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

The case for financial literacy education

Paddy Hirsch

Financial literacy education does not have a great reputation . It's a huge industry, spawning all sorts of books, web channels, TV shows and even social media accounts — but past studies have concluded that, for the most part, financial literacy education is kind of a waste of time .

For example, a much cited paper published in the journal Management Science found that almost everyone who took a financial literacy class forgot what they learned within 20 months, and that financial literacy has a "negligible" impact on future behavior. A trio of academics at Harvard Business School, Wellesley College and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, produced a working paper that showed that mandated Finlit classes given to high schoolers made no difference to the students' ability to handle their finances. And the list goes on .

The name that comes up again and again in these papers and reports on financial literacy is Annamaria Lusardi. She is a professor of economics and accountancy at the George Washington University School of Business. She's also the founder and academic director of the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center at GWU. She and Olivia Mitchell, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Business, published a paper in 2013 that amounted to a study of studies about financial literacy , and it was quite critical of the way financial literacy programs are taught. This study of studies has been widely quoted ever since.

New Hope For Financial Dullards

Ten years later, Lusardi and Mitchell are out with a new paper, similarly titled , but much more upbeat. "The Importance of Financial Literacy: Opening A New Field," picks up where their 2013 study of studies left off, and it draws on the two women's experience teaching personal finance.

The first thing they establish is that the level of financial literacy, globally, is just as woeful as it was when they released their seminal paper ten years ago. To establish this, they conducted a survey that asked participants three questions, which focus on interest rates, inflation and risk diversification.

"These are simple questions," Lusardi says, "Yet they test for basic and fundamental knowledge at the basis of most economic decisions. In addition, answering these questions does not require difficult calculations, as we do not test for knowledge of mathematics but rather for an understanding of how interest rates and inflation work. The questions also test knowledge of the language of finance."

How did respondents do? Let's just say there is room for improvement. (You can test your own knowledge by checking out the paper ).

"Only 43% of the respondents (in the US) are able to answer all of the questions correctly," Lusardi says, adding that the level of financial illiteracy is particularly acute amongst women. "Only 29% of women answer all three questions correctly, versus 48% of men," she says, adding that this gender difference is strikingly stable across the 140 countries that they ran the test in.

"We also see ... that women are much more likely than men to respond that they do not know/refuse to answer at least one financial literacy question," she says. Such gender differences are likely to be the result of lack of self-confidence, in addition to lack of knowledge."

Young people are also more likely to be disadvantaged in this area, Lusardi and Mitchell found, as are people of color. "The young display very low financial literacy, with only one-third being able to answer all three questions correctly. Half of Whites could correctly answer all three questions, versus only 26% of Blacks and 22% of Hispanics."

This is a problem, Lusardi says, not just because it means that many people are ill equipped to handle an increasingly complicated and complex financial landscape that can impact their earnings and long-term wealth. There are obvious social implications to the fact that white males appear to have a significant edge on the rest of the population in this area. And if that isn't enough, Lusardi says, it's also a problem for the economy.

"On average, Americans spend seven hours per week dealing with personal finance issues, three of which are at work. People with low financial literacy spend double that amount," she says. The impact on productivity of people spending most of an entire working day on their personal finances whilst at work is considerable, she goes on. Add in the consequences of mismanagement of assets, investments, mortgages and other debt, and there is a significant potential effect on the economy.

Lusardi says this idea, that the damage wrought by a lack of financial literacy might extend beyond the individual — to companies and even to the economy has not escaped the notice of governments.

"Influential policymakers and central bankers, including former Fed Chairman, Ben Bernanke, have ... spoken to the critical importance of financial literacy," the paper says. "Additionally, the European Commission has recently acknowledged the importance of financial literacy as a key step for a capital markets union. Some governments have ... implemented financial literacy training in high schools. Several years ago, the Council for Economic Education (CEE 2013) established National Standards for Financial Literacy, detailing what should be covered in personal finance courses in school."

Fixing The Flaws

A decade ago, Lusardi and Mitchell were somewhat critical of the financial literacy courses offered by companies and schools. The programs were generally not effective, they said, not because the concept of personal finance education was flawed per se, but because the various programs were generally not well resourced, and often poorly conceived.

"Most of these (courses) in the US were unfunded," Lusardi says. "There was no curriculum. There were no materials, and teachers were hardly trained. So the gym teacher was teaching financial literacy, or anybody they could find. This is, of course, not going to work. It wouldn't work for any topic. If you have a course in French and the teacher doesn't speak good French, (students) are probably not going to learn good French either."

Moreover, the classes, whether taught in schools or in corporate offices, tended to provide one-shot, one-size-fits-all instructions, with little or no follow-up. Lusardi says that was a recipe for failure. But those organizations that have recognized the need for financial literacy programs, and that have persisted in developing them, have made progress, she says.

"Many programs have moved beyond very short interventions, such as a single retirement seminar or sending employees to a benefits fair, to more robust programs," Lusardi says. "Financial literacy has now become an official field of study in the economics profession. Many initiatives at national levels have been launched, and more than 80 countries have set up national committees entrusted with the design and implementation of national strategies for financial literacy."

Lusardi says it's particularly important to teach and consolidate principles of good personal finance as early as possible, which means starting at home — where children are likely to model good financial habits — and in school. To that end, the Programme for International Student Assessment in 2012 added financial literacy to the set of topics that 15-year-old students need to know to be able to participate in modern society and be successful in the labor market.

Lusardi says that in the decade since she and Mitchell released their 2013 report, their experience teaching financial literacy has proved that these programs, properly taught, can work.

"Our research shows that much can be done to help people make savvier financial decisions," she says, noting that a successful course will help people grasp key fundamental financial concepts, particularly financial risk and risk management. It will help them understand the workings of specific financial instruments and contracts, such as student loans, mortgages, credit cards, investments, and annuities. It will also make them aware of their rights and obligations in the financial marketplace.

Most importantly of all, of course, it will attract and retain the students' interest, which isn't always easy in the dry world of finance.

"I teach very differently now because of my research," Lusardi says. "I say, what do you think this course is about? And as you can imagine, most of the students think it's about investing in the stock market. That's what personal finance is associated with. And I tell them, 'No, this is a happiness project. We talk about all of the decisions that are fundamental and important in your life. And I want to teach you to make them well, because if you do, you are going to be happy.'"

- financial literacy

- Conference key note

- Open access

- Published: 24 January 2019

Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications

- Annamaria Lusardi 1

Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics volume 155 , Article number: 1 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

405k Accesses

282 Citations

191 Altmetric

Metrics details

1 Introduction

Throughout their lifetime, individuals today are more responsible for their personal finances than ever before. With life expectancies rising, pension and social welfare systems are being strained. In many countries, employer-sponsored defined benefit (DB) pension plans are swiftly giving way to private defined contribution (DC) plans, shifting the responsibility for retirement saving and investing from employers to employees. Individuals have also experienced changes in labor markets. Skills are becoming more critical, leading to divergence in wages between those with a college education, or higher, and those with lower levels of education. Simultaneously, financial markets are rapidly changing, with developments in technology and new and more complex financial products. From student loans to mortgages, credit cards, mutual funds, and annuities, the range of financial products people have to choose from is very different from what it was in the past, and decisions relating to these financial products have implications for individual well-being. Moreover, the exponential growth in financial technology (fintech) is revolutionizing the way people make payments, decide about their financial investments, and seek financial advice. In this context, it is important to understand how financially knowledgeable people are and to what extent their knowledge of finance affects their financial decision-making.

An essential indicator of people’s ability to make financial decisions is their level of financial literacy. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) aptly defines financial literacy as not only the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks but also the skills, motivation, and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life. Thus, financial literacy refers to both knowledge and financial behavior, and this paper will analyze research on both topics.

As I describe in more detail below, findings around the world are sobering. Financial literacy is low even in advanced economies with well-developed financial markets. On average, about one third of the global population has familiarity with the basic concepts that underlie everyday financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ). The average hides gaping vulnerabilities of certain population subgroups and even lower knowledge of specific financial topics. Furthermore, there is evidence of a lack of confidence, particularly among women, and this has implications for how people approach and make financial decisions. In the following sections, I describe how we measure financial literacy, the levels of literacy we find around the world, the implications of those findings for financial decision-making, and how we can improve financial literacy.

2 How financially literate are people?

2.1 measuring financial literacy: the big three.

In the context of rapid changes and constant developments in the financial sector and the broader economy, it is important to understand whether people are equipped to effectively navigate the maze of financial decisions that they face every day. To provide the tools for better financial decision-making, one must assess not only what people know but also what they need to know, and then evaluate the gap between those things. There are a few fundamental concepts at the basis of most financial decision-making. These concepts are universal, applying to every context and economic environment. Three such concepts are (1) numeracy as it relates to the capacity to do interest rate calculations and understand interest compounding; (2) understanding of inflation; and (3) understanding of risk diversification. Translating these concepts into easily measured financial literacy metrics is difficult, but Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2008 , 2011b , 2011c ) have designed a standard set of questions around these concepts and implemented them in numerous surveys in the USA and around the world.

Four principles informed the design of these questions, as described in detail by Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ). The first is simplicity : the questions should measure knowledge of the building blocks fundamental to decision-making in an intertemporal setting. The second is relevance : the questions should relate to concepts pertinent to peoples’ day-to-day financial decisions over the life cycle; moreover, they must capture general rather than context-specific ideas. Third is brevity : the number of questions must be few enough to secure widespread adoption; and fourth is capacity to differentiate , meaning that questions should differentiate financial knowledge in such a way as to permit comparisons across people. Each of these principles is important in the context of face-to-face, telephone, and online surveys.

Three basic questions (since dubbed the “Big Three”) to measure financial literacy have been fielded in many surveys in the USA, including the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) and, more recently, the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), and in many national surveys around the world. They have also become the standard way to measure financial literacy in surveys used by the private sector. For example, the Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement included the Big Three questions in the 2018 Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey, covering around 16,000 people in 15 countries. Both ING and Allianz, but also investment funds, and pension funds have used the Big Three to measure financial literacy. The exact wording of the questions is provided in Table 1 .

2.2 Cross-country comparison

The first examination of financial literacy using the Big Three was possible due to a special module on financial literacy and retirement planning that Lusardi and Mitchell designed for the 2004 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which is a survey of Americans over age 50. Astonishingly, the data showed that only half of older Americans—who presumably had made many financial decisions in their lives—could answer the two basic questions measuring understanding of interest rates and inflation (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ). And just one third demonstrated understanding of these two concepts and answered the third question, measuring understanding of risk diversification, correctly. It is sobering that recent US surveys, such as the 2015 NFCS, the 2016 SCF, and the 2017 Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking (SHED), show that financial knowledge has remained stubbornly low over time.

Over time, the Big Three have been added to other national surveys across countries and Lusardi and Mitchell have coordinated a project called Financial Literacy around the World (FLat World), which is an international comparison of financial literacy (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ).

Findings from the FLat World project, which so far includes data from 15 countries, including Switzerland, highlight the urgent need to improve financial literacy (see Table 2 ). Across countries, financial literacy is at a crisis level, with the average rate of financial literacy, as measured by those answering correctly all three questions, at around 30%. Moreover, only around 50% of respondents in most countries are able to correctly answer the two financial literacy questions on interest rates and inflation correctly. A noteworthy point is that most countries included in the FLat World project have well-developed financial markets, which further highlights the cause for alarm over the demonstrated lack of the financial literacy. The fact that levels of financial literacy are so similar across countries with varying levels of economic development—indicating that in terms of financial knowledge, the world is indeed flat —shows that income levels or ubiquity of complex financial products do not by themselves equate to a more financially literate population.

Other noteworthy findings emerge in Table 2 . For instance, as expected, understanding of the effects of inflation (i.e., of real versus nominal values) among survey respondents is low in countries that have experienced deflation rather than inflation: in Japan, understanding of inflation is at 59%; in other countries, such as Germany, it is at 78% and, in the Netherlands, it is at 77%. Across countries, individuals have the lowest level of knowledge around the concept of risk, and the percentage of correct answers is particularly low when looking at knowledge of risk diversification. Here, we note the prevalence of “do not know” answers. While “do not know” responses hover around 15% on the topic of interest rates and 18% for inflation, about 30% of respondents—in some countries even more—are likely to respond “do not know” to the risk diversification question. In Switzerland, 74% answered the risk diversification question correctly and 13% reported not knowing the answer (compared to 3% and 4% responding “do not know” for the interest rates and inflation questions, respectively).

These findings are supported by many other surveys. For example, the 2014 Standard & Poor’s Global Financial Literacy Survey shows that, around the world, people know the least about risk and risk diversification (Klapper, Lusardi, and Van Oudheusden, 2015 ). Similarly, results from the 2016 Allianz survey, which collected evidence from ten European countries on money, financial literacy, and risk in the digital age, show very low-risk literacy in all countries covered by the survey. In Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, which are the three top-performing nations in term of financial knowledge, less than 20% of respondents can answer three questions related to knowledge of risk and risk diversification (Allianz, 2017 ).

Other surveys show that the findings about financial literacy correlate in an expected way with other data. For example, performance on the mathematics and science sections of the OECD Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) correlates with performance on the Big Three and, specifically, on the question relating to interest rates. Similarly, respondents in Sweden, which has experienced pension privatization, performed better on the risk diversification question (at 68%), than did respondents in Russia and East Germany, where people have had less exposure to the stock market. For researchers studying financial knowledge and its effects, these findings hint to the fact that financial literacy could be the result of choice and not an exogenous variable.

To summarize, financial literacy is low across the world and higher national income levels do not equate to a more financially literate population. The design of the Big Three questions enables a global comparison and allows for a deeper understanding of financial literacy. This enhances the measure’s utility because it helps to identify general and specific vulnerabilities across countries and within population subgroups, as will be explained in the next section.

2.3 Who knows the least?

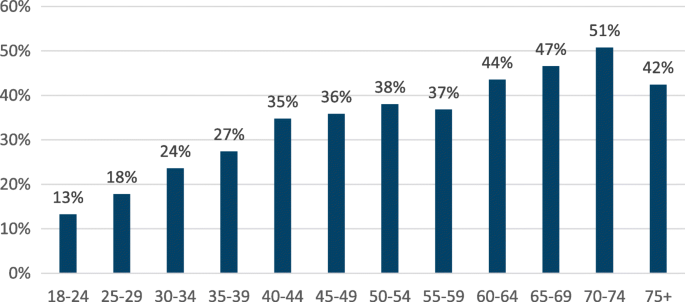

Low financial literacy on average is exacerbated by patterns of vulnerability among specific population subgroups. For instance, as reported in Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ), even though educational attainment is positively correlated with financial literacy, it is not sufficient. Even well-educated people are not necessarily savvy about money. Financial literacy is also low among the young. In the USA, less than 30% of respondents can correctly answer the Big Three by age 40, even though many consequential financial decisions are made well before that age (see Fig. 1 ). Similarly, in Switzerland, only 45% of those aged 35 or younger are able to correctly answer the Big Three questions. Footnote 1 And if people may learn from making financial decisions, that learning seems limited. As shown in Fig. 1 , many older individuals, who have already made decisions, cannot answer three basic financial literacy questions.

Financial literacy across age in the USA. This figure shows the percentage of respondents who answered correctly all Big Three questions by age group (year 2015). Source: 2015 US National Financial Capability Study

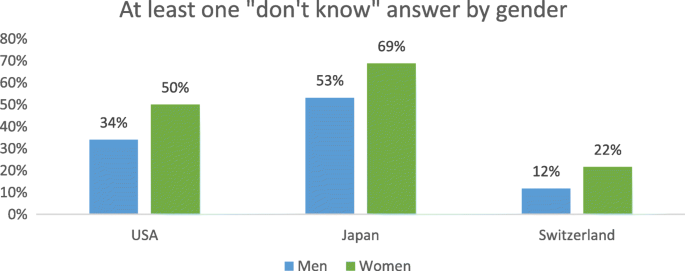

A gender gap in financial literacy is also present across countries. Women are less likely than men to answer questions correctly. The gap is present not only on the overall scale but also within each topic, across countries of different income levels, and at different ages. Women are also disproportionately more likely to indicate that they do not know the answer to specific questions (Fig. 2 ), highlighting overconfidence among men and awareness of lack of knowledge among women. Even in Finland, which is a relatively equal society in terms of gender, 44% of men compared to 27% of women answer all three questions correctly and 18% of women give at least one “do not know” response versus less than 10% of men (Kalmi and Ruuskanen, 2017 ). These figures further reflect the universality of the Big Three questions. As reported in Fig. 2 , “do not know” responses among women are prevalent not only in European countries, for example, Switzerland, but also in North America (represented in the figure by the USA, though similar findings are reported in Canada) and in Asia (represented in the figure by Japan). Those interested in learning more about the differences in financial literacy across demographics and other characteristics can consult Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2011c , 2014 ).

Gender differences in the responses to the Big Three questions. Sources: USA—Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ; Japan—Sekita, 2011 ; Switzerland—Brown and Graf, 2013

3 Does financial literacy matter?

A growing number of financial instruments have gained importance, including alternative financial services such as payday loans, pawnshops, and rent to own stores that charge very high interest rates. Simultaneously, in the changing economic landscape, people are increasingly responsible for personal financial planning and for investing and spending their resources throughout their lifetime. We have witnessed changes not only in the asset side of household balance sheets but also in the liability side. For example, in the USA, many people arrive close to retirement carrying a lot more debt than previous generations did (Lusardi, Mitchell, and Oggero, 2018 ). Overall, individuals are making substantially more financial decisions over their lifetime, living longer, and gaining access to a range of new financial products. These trends, combined with low financial literacy levels around the world and, particularly, among vulnerable population groups, indicate that elevating financial literacy must become a priority for policy makers.

There is ample evidence of the impact of financial literacy on people’s decisions and financial behavior. For example, financial literacy has been proven to affect both saving and investment behavior and debt management and borrowing practices. Empirically, financially savvy people are more likely to accumulate wealth (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014 ). There are several explanations for why higher financial literacy translates into greater wealth. Several studies have documented that those who have higher financial literacy are more likely to plan for retirement, probably because they are more likely to appreciate the power of interest compounding and are better able to do calculations. According to the findings of the FLat World project, answering one additional financial question correctly is associated with a 3–4 percentage point greater probability of planning for retirement; this finding is seen in Germany, the USA, Japan, and Sweden. Financial literacy is found to have the strongest impact in the Netherlands, where knowing the right answer to one additional financial literacy question is associated with a 10 percentage point higher probability of planning (Mitchell and Lusardi, 2015 ). Empirically, planning is a very strong predictor of wealth; those who plan arrive close to retirement with two to three times the amount of wealth as those who do not plan (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ).

Financial literacy is also associated with higher returns on investments and investment in more complex assets, such as stocks, which normally offer higher rates of return. This finding has important consequences for wealth; according to the simulation by Lusardi, Michaud, and Mitchell ( 2017 ), in the context of a life-cycle model of saving with many sources of uncertainty, from 30 to 40% of US retirement wealth inequality can be accounted for by differences in financial knowledge. These results show that financial literacy is not a sideshow, but it plays a critical role in saving and wealth accumulation.

Financial literacy is also strongly correlated with a greater ability to cope with emergency expenses and weather income shocks. Those who are financially literate are more likely to report that they can come up with $2000 in 30 days or that they are able to cover an emergency expense of $400 with cash or savings (Hasler, Lusardi, and Oggero, 2018 ).

With regard to debt behavior, those who are more financially literate are less likely to have credit card debt and more likely to pay the full balance of their credit card each month rather than just paying the minimum due (Lusardi and Tufano, 2009 , 2015 ). Individuals with higher financial literacy levels also are more likely to refinance their mortgages when it makes sense to do so, tend not to borrow against their 401(k) plans, and are less likely to use high-cost borrowing methods, e.g., payday loans, pawn shops, auto title loans, and refund anticipation loans (Lusardi and de Bassa Scheresberg, 2013 ).

Several studies have documented poor debt behavior and its link to financial literacy. Moore ( 2003 ) reported that the least financially literate are also more likely to have costly mortgages. Lusardi and Tufano ( 2015 ) showed that the least financially savvy incurred high transaction costs, paying higher fees and using high-cost borrowing methods. In their study, the less knowledgeable also reported excessive debt loads and an inability to judge their debt positions. Similarly, Mottola ( 2013 ) found that those with low financial literacy were more likely to engage in costly credit card behavior, and Utkus and Young ( 2011 ) concluded that the least literate were more likely to borrow against their 401(k) and pension accounts.

Young people also struggle with debt, in particular with student loans. According to Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Oggero ( 2016 ), Millennials know little about their student loans and many do not attempt to calculate the payment amounts that will later be associated with the loans they take. When asked what they would do, if given the chance to revisit their student loan borrowing decisions, about half of Millennials indicate that they would make a different decision.

Finally, a recent report on Millennials in the USA (18- to 34-year-olds) noted the impact of financial technology (fintech) on the financial behavior of young individuals. New and rapidly expanding mobile payment options have made transactions easier, quicker, and more convenient. The average user of mobile payments apps and technology in the USA is a high-income, well-educated male who works full time and is likely to belong to an ethnic minority group. Overall, users of mobile payments are busy individuals who are financially active (holding more assets and incurring more debt). However, mobile payment users display expensive financial behaviors, such as spending more than they earn, using alternative financial services, and occasionally overdrawing their checking accounts. Additionally, mobile payment users display lower levels of financial literacy (Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Avery, 2018 ). The rapid growth in fintech around the world juxtaposed with expensive financial behavior means that more attention must be paid to the impact of mobile payment use on financial behavior. Fintech is not a substitute for financial literacy.

4 The way forward for financial literacy and what works

Overall, financial literacy affects everything from day-to-day to long-term financial decisions, and this has implications for both individuals and society. Low levels of financial literacy across countries are correlated with ineffective spending and financial planning, and expensive borrowing and debt management. These low levels of financial literacy worldwide and their widespread implications necessitate urgent efforts. Results from various surveys and research show that the Big Three questions are useful not only in assessing aggregate financial literacy but also in identifying vulnerable population subgroups and areas of financial decision-making that need improvement. Thus, these findings are relevant for policy makers and practitioners. Financial illiteracy has implications not only for the decisions that people make for themselves but also for society. The rapid spread of mobile payment technology and alternative financial services combined with lack of financial literacy can exacerbate wealth inequality.

To be effective, financial literacy initiatives need to be large and scalable. Schools, workplaces, and community platforms provide unique opportunities to deliver financial education to large and often diverse segments of the population. Furthermore, stark vulnerabilities across countries make it clear that specific subgroups, such as women and young people, are ideal targets for financial literacy programs. Given women’s awareness of their lack of financial knowledge, as indicated via their “do not know” responses to the Big Three questions, they are likely to be more receptive to financial education.

The near-crisis levels of financial illiteracy, the adverse impact that it has on financial behavior, and the vulnerabilities of certain groups speak of the need for and importance of financial education. Financial education is a crucial foundation for raising financial literacy and informing the next generations of consumers, workers, and citizens. Many countries have seen efforts in recent years to implement and provide financial education in schools, colleges, and workplaces. However, the continuously low levels of financial literacy across the world indicate that a piece of the puzzle is missing. A key lesson is that when it comes to providing financial education, one size does not fit all. In addition to the potential for large-scale implementation, the main components of any financial literacy program should be tailored content, targeted at specific audiences. An effective financial education program efficiently identifies the needs of its audience, accurately targets vulnerable groups, has clear objectives, and relies on rigorous evaluation metrics.

Using measures like the Big Three questions, it is imperative to recognize vulnerable groups and their specific needs in program designs. Upon identification, the next step is to incorporate this knowledge into financial education programs and solutions.

School-based education can be transformational by preparing young people for important financial decisions. The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), in both 2012 and 2015, found that, on average, only 10% of 15-year-olds achieved maximum proficiency on a five-point financial literacy scale. As of 2015, about one in five of students did not have even basic financial skills (see OECD, 2017 ). Rigorous financial education programs, coupled with teacher training and high school financial education requirements, are found to be correlated with fewer defaults and higher credit scores among young adults in the USA (Urban, Schmeiser, Collins, and Brown, 2018 ). It is important to target students and young adults in schools and colleges to provide them with the necessary tools to make sound financial decisions as they graduate and take on responsibilities, such as buying cars and houses, or starting retirement accounts. Given the rising cost of education and student loan debt and the need of young people to start contributing as early as possible to retirement accounts, the importance of financial education in school cannot be overstated.

There are three compelling reasons for having financial education in school. First, it is important to expose young people to the basic concepts underlying financial decision-making before they make important and consequential financial decisions. As noted in Fig. 1 , financial literacy is very low among the young and it does not seem to increase a lot with age/generations. Second, school provides access to financial literacy to groups who may not be exposed to it (or may not be equally exposed to it), for example, women. Third, it is important to reduce the costs of acquiring financial literacy, if we want to promote higher financial literacy both among individuals and among society.

There are compelling reasons to have personal finance courses in college as well. In the same way in which colleges and university offer courses in corporate finance to teach how to manage the finances of firms, so today individuals need the knowledge to manage their own finances over the lifetime, which in present discounted value often amount to large values and are made larger by private pension accounts.

Financial education can also be efficiently provided in workplaces. An effective financial education program targeted to adults recognizes the socioeconomic context of employees and offers interventions tailored to their specific needs. A case study conducted in 2013 with employees of the US Federal Reserve System showed that completing a financial literacy learning module led to significant changes in retirement planning behavior and better-performing investment portfolios (Clark, Lusardi, and Mitchell, 2017 ). It is also important to note the delivery method of these programs, especially when targeted to adults. For instance, video formats have a significantly higher impact on financial behavior than simple narratives, and instruction is most effective when it is kept brief and relevant (Heinberg et al., 2014 ).

The Big Three also show that it is particularly important to make people familiar with the concepts of risk and risk diversification. Programs devoted to teaching risk via, for example, visual tools have shown great promise (Lusardi et al., 2017 ). The complexity of some of these concepts and the costs of providing education in the workplace, coupled with the fact that many older individuals may not work or work in firms that do not offer such education, provide other reasons why financial education in school is so important.

Finally, it is important to provide financial education in the community, in places where people go to learn. A recent example is the International Federation of Finance Museums, an innovative global collaboration that promotes financial knowledge through museum exhibits and the exchange of resources. Museums can be places where to provide financial literacy both among the young and the old.

There are a variety of other ways in which financial education can be offered and also targeted to specific groups. However, there are few evaluations of the effectiveness of such initiatives and this is an area where more research is urgently needed, given the statistics reported in the first part of this paper.

5 Concluding remarks

The lack of financial literacy, even in some of the world’s most well-developed financial markets, is of acute concern and needs immediate attention. The Big Three questions that were designed to measure financial literacy go a long way in identifying aggregate differences in financial knowledge and highlighting vulnerabilities within populations and across topics of interest, thereby facilitating the development of tailored programs. Many such programs to provide financial education in schools and colleges, workplaces, and the larger community have taken existing evidence into account to create rigorous solutions. It is important to continue making strides in promoting financial literacy, by achieving scale and efficiency in future programs as well.

In August 2017, I was appointed Director of the Italian Financial Education Committee, tasked with designing and implementing the national strategy for financial literacy. I will be able to apply my research to policy and program initiatives in Italy to promote financial literacy: it is an essential skill in the twenty-first century, one that individuals need if they are to thrive economically in today’s society. As the research discussed in this paper well documents, financial literacy is like a global passport that allows individuals to make the most of the plethora of financial products available in the market and to make sound financial decisions. Financial literacy should be seen as a fundamental right and universal need, rather than the privilege of the relatively few consumers who have special access to financial knowledge or financial advice. In today’s world, financial literacy should be considered as important as basic literacy, i.e., the ability to read and write. Without it, individuals and societies cannot reach their full potential.

See Brown and Graf ( 2013 ).

Abbreviations

Defined benefit (refers to pension plan)

Defined contribution (refers to pension plan)

Financial Literacy around the World

National Financial Capability Study

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Programme for International Student Assessment

Survey of Consumer Finances

Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking

Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement. (2018). The New Social Contract: a blueprint for retirement in the 21st century. The Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey 2018. Retrieved from https://www.aegon.com/en/Home/Research/aegon-retirement-readiness-survey-2018/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Agnew, J., Bateman, H., & Thorp, S. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Australia. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Allianz (2017). When will the penny drop? Money, financial literacy and risk in the digital age. Retrieved from http://gflec.org/initiatives/money-finlit-risk/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Almenberg, J., & Säve-Söderbergh, J. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Sweden. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 585–598.

Article Google Scholar

Arrondel, L., Debbich, M., & Savignac, F. (2013). Financial literacy and financial planning in France. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Beckmann, E. (2013). Financial literacy and household savings in Romania. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Boisclair, D., Lusardi, A., & Michaud, P. C. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Canada. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16 (3), 277–296.

Brown, M., & Graf, R. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Switzerland. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Bucher-Koenen, T., & Lusardi, A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 565–584.

Clark, R., Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). Employee financial literacy and retirement plan behavior: a case study. Economic Inquiry, 55 (1), 248–259.

Crossan, D., Feslier, D., & Hurnard, R. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in New Zealand. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 619–635.

Fornero, E., & Monticone, C. (2011). Financial literacy and pension plan participation in Italy. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 547–564.

Hasler, A., Lusardi, A., and Oggero, N. (2018). Financial fragility in the US: evidence and implications. GFLEC working paper n. 2018–1.

Heinberg, A., Hung, A., Kapteyn, A., Lusardi, A., Samek, A. S., & Yoong, J. (2014). Five steps to planning success: experimental evidence from US households. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 30 (4), 697–724.

Kalmi, P., & Ruuskanen, O. P. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Finland. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 17 (3), 1–28.

Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., & Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). Financial literacy around the world. In Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey (GFLEC working paper).

Google Scholar

Klapper, L., & Panos, G. A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning: The Russian case. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 599–618.

Lusardi, A., & de Bassa Scheresberg, C. (2013). Financial literacy and high-cost borrowing in the United States, NBER Working Paper n. 18969, April .

Book Google Scholar

Lusardi, A., de Bassa Scheresberg, C., and Avery, M. 2018. Millennial mobile payment users: a look into their personal finances and financial behaviors. GFLEC working paper.

Lusardi, A., de Bassa Scheresberg, C., & Oggero, N. (2016). Student loan debt in the US: an analysis of the 2015 NFCS Data, GFLEC Policy Brief, November .

Lusardi, A., Michaud, P. C., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). Optimal financial knowledge and wealth inequality. Journal of Political Economy, 125 (2), 431–477.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2008). Planning and financial literacy: how do women fare? American Economic Review, 98 , 413–417.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011a). The outlook for financial literacy. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 1–15). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011b). Financial literacy and planning: implications for retirement wellbeing. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 17–39). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011c). Financial literacy around the world: an overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10 (4), 497–508.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52 (1), 5–44.

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O. S., & Oggero, N. (2018). The changing face of debt and financial fragility at older ages. American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings, 108 , 407–411.

Lusardi, A., Samek, A., Kapteyn, A., Glinert, L., Hung, A., & Heinberg, A. (2017). Visual tools and narratives: new ways to improve financial literacy. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16 (3), 297–323.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2009). Teach workers about the peril of debt. Harvard Business Review , 22–24.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2015). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 14 (4), 332–368.

Mitchell, O. S., & Lusardi, A. (2015). Financial literacy and economic outcomes: evidence and policy implications. The Journal of Retirement, 3 (1).

Moore, Danna. 2003. Survey of financial literacy in Washington State: knowledge, behavior, attitudes and experiences. Washington State University Social and Economic Sciences Research Center Technical Report 03–39.

Mottola, G. R. (2013). In our best interest: women, financial literacy, and credit card behavior. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Moure, N. G. (2016). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Chile. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 15 (2), 203–223.

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 results (Volume IV): students’ financial literacy . Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270282-en .

Sekita, S. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Japan. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 637–656.

Urban, C., Schmeiser, M., Collins, J. M., & Brown, A. (2018). The effects of high school personal financial education policies on financial behavior. Economics of Education Review . https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272775718301699 .

Utkus, S., & Young, J. (2011). Financial literacy and 401(k) loans. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 59–75). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Rooij, M. C., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. J. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement preparation in the Netherlands. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10 (4), 527–545.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This paper represents a summary of the keynote address I gave to the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society of Economics and Statistics. I would like to thank Monika Butler, Rafael Lalive, anonymous reviewers, and participants of the Annual Meeting for useful discussions and comments, and Raveesha Gupta for editorial support. All errors are my responsibility.

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Author information, authors and affiliations.

The George Washington University School of Business Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center and Italian Committee for Financial Education, Washington, D.C., USA

Annamaria Lusardi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Annamaria Lusardi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares that she has no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lusardi, A. Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications. Swiss J Economics Statistics 155 , 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

Download citation

Received : 22 October 2018

Accepted : 07 January 2019

Published : 24 January 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

NGPF Case Studies

New to ngpf.

Save time, increase student engagement, and help your students build life-changing financial skills with NGPF's free curriculum and PD.

Start with a FREE Teacher Account to unlock NGPF's teachers-only materials!

Become an ngpf pro in 4 easy steps:.

1. Sign up for your Teacher Account

2. Explore a unit page

3. Join NGPF Academy

4. Become an NGPF Pro!

Want to see some of our best stuff?

Spin the wheel and discover an engaging activity for your class, your result:.

ANALYZE: College and Career Choices

Case Studies present personal finance issues in the context of real-life situations with all their ambiguities. Students will explore decision-making, develop communication skills, and make choices when there is no “right” answer.

To help get you started, NGPF has created support guides to walk you through how to complete case studies with ease:

- Teacher Support Guide

- Student Support Guide

(Sp) denotes resource is also available in Spanish

Behavioral Economics

Consumer skills, paying for college, types of credit, managing credit, ngpf mini-units, cryptocurrency, alternatives to 4-year colleges, buying a car, buying a house, entrepreneurship, philanthropy, racial discrimination in finance, sending form..., one more thing.

Before your subscription to our newsletter is active, you need to confirm your email address by clicking the link in the email we just sent you. It may take a couple minutes to arrive, and we suggest checking your spam folders just in case!

Great! Success message here

Teacher Account Log In

Not a member? Sign Up

Forgot Password?

Thank you for registering for an NGPF Teacher Account!

Your new account will provide you with access to NGPF Assessments and Answer Keys. It may take up to 1 business day for your Teacher Account to be activated; we will notify you once the process is complete.

Thanks for joining our community!

The NGPF Team

Want a daily question of the day?

Subscribe to our blog and have one delivered to your inbox each morning, create a free teacher account.

Complete the form below to access exclusive resources for teachers. Our team will review your account and send you a follow up email within 24 hours.

Your Information

School lookup, add your school information.

To speed up your verification process, please submit proof of status to gain access to answer keys & assessments.

Acceptable information includes:

- a picture of you (think selfie!) holding your teacher/employee badge

- screenshots of your online learning portal or grade book

- screenshots to a staff directory page that lists your e-mail address

- any other means that can prove you are not a student attempting to gain access to the answer keys and assessments.

Acceptable file types: .png, .jpg, .pdf.

Create a Username & Password

Once you submit this form, our team will review your account and send you a follow up email within 24 hours. We may need additional information to verify your teacher status before you have full access to NGPF.

Already a member? Log In

Welcome to NGPF!

Take the quiz to quickly find the best resources for you!

ANSWER KEY ACCESS

- News & Events

- Quick Links

- Majors & Programs

- People Finder

- home site index contact us

ScholarWorks@GVSU

- < Previous

Home > Graduate Research and Creative Practice > Masters Theses > 1057

Masters Theses

Financial literacy: a case study on current practices.

Briana Lee Hammontree , Grand Valley State University Follow

Date Approved

Graduate degree type, degree name.

Social Innovation (M.A.)

Degree Program

Integrative, Religious, and Intercultural Studies

First Advisor

Joel Wendland-Liu

Academic Year

In the last few years, the concern for financial illiteracy among teenagers has only grown as the economy has shifted. Many teenagers feel unprepared and unsecured moving forward with their finances as adults. This issue is intensified further among low-income and marginalized youths who deal with additional hardship in their lives. Accessibility is a huge issue among teenagers and the role of financial literacy of their lives in education is often predetermined by government officials and policies they can only really advocate for change for but cannot vote on. In this research I explore the concept of utilizing social innovation to bridge the gap scene in politics and collaborating with nonprofits to establish an effective financial literacy program for youth. By studying three programs that are local, state, or nationally associated, I examine the programs and tools they offer their clients to develop an understanding of their usefulness and how it could be applied into a program.

ScholarWorks Citation

Hammontree, Briana Lee, "Financial Literacy: A Case Study on Current Practices" (2022). Masters Theses . 1057. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/1057

Since August 04, 2022

Included in

Education Economics Commons

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- University Archives

- Open Textbooks

- Open Educational Resources

- Graduate Research and Creative Practice

- Selected Works Galleries

Author Information

- Submission Guidelines

- Submit Research

- Graduate Student Resources

Home | About | FAQ | Contact | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

- Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

- What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions, alert: harvard yard closed to the public.

Please note, Harvard Yard gates are currently closed. Entry will be permitted to those with a Harvard ID only.

Last Updated: May 03, 11:02am

Open Alert: Harvard Yard Closed to the Public

Financial Literacy

Helping you prepare for life..

We want financial literacy to be a part of your life. To that end, we have focused our resources on providing support and education on financial understanding for all students. The more you know, and the more tools you have at your disposal, the better prepared you will be for life at and beyond Harvard.

In this guide, you'll find information on budgeting, credit, saving and investing, and taxes.

A budget is, simply put, a plan for your money. By tracking income and expenses you can create a plan for your spending and saving.

Why do you need a budget?

If you have ever found yourself looking at your bank account and wondering where your money went, a budget can help. The most common cause of financial problems is spending more than you are earning. With a flexible, sensible budget, you can control of your money and avoid financial stress. It can help you limit spending and ensure there is enough money to do the things that you want.

How to get started

- Build a starting budget with your best guess of what you spend in a month (on average), separated into categories like books, personal expenses, rent, phone, and entertainment.

- Track your expenses for a few months. Then, compare these figures with your previous projections. You may be surprised to see where your guesses were higher or lower.

- Once you have tracked your expenses, compare these to your income. If you are spending more than you are earning, you need to make changes.

- Be honest about "needs" vs. "wants". Enjoying a store-bought coffee every single day is nice, but you could save up to $80/month by reducing this purchase from daily to weekly.

- Review your monthly budget for any necessary changes. Remember: a budget is fluid, meaning that it will (and should) adjust as your income and goals adjust.

Determining How Much Disposable Income You Have

Consider setting some of your income aside in a savings account, and putting limits on how much you can spend on non-essential items.

Let’s say you buy a cup of coffee on most days, grab a quick bite a couple times a week, and go out on Saturday nights for fun with friends. Your yearly spending may look like this:

- Coffee 4x/week @ $2.50 = $520

- Quick late-night snack 3x/week @ $6.50 = $1,014

- Weekend Fun @ $25-30 each weekend = $1,560

Your total spending would be $3,094 per year, or $12,376 for the four years of college--enough to buy a car. Considering this, make sure you’re being thoughtful about how you want to spend and save your money!

Moving forward with a flexible budget

For your budget to be useful, you need to follow it for more than a few months. Tracking your daily purchases only takes a few minutes. It takes even less time with a budgeting app that links to your bank and credit card accounts and automatically categorizes your purchases. Finding it hard to stick to your budget? Some of your figures may be unrealistic so review and adjust as needed. Perhaps you need to allocate more towards books and travel, and less on clothing. The best budget is one that grows and changes to meet your needs

What can you do now?

Setting up financial goals will help you plan and prioritize what’s important to you, and how you should set up a budget to align with your interests. Goals will also help you be more aware of how you spend your money day-to-day. It’s a good idea to write out these goals, and to stay mindful of them as you go through college!

If you like a pen and paper approach, you can try a simple tracking sheet like this one from Balance Pro or a more comprehensive budget worksheet like this one from the Harvard University Employees Credit Union . If you prefer a phone app, there are many to choose from and most are free. Read reviews to determine what makes the most sense for you.

Credit is a major factor in today's economy and is your reputation as a borrower. In order to have the best reputation, credit wise, you should take the time to learn about managing your credit. This is especially important when it comes time to rent an apartment, finance a car, buy a house, or even find a job. The sooner you start building your credit profile, the better off you'll be in the future.

Credit Report vs. Credit Score

A credit report is a detailed report of your credit history. It has personal information, employment history, and a list of open and closed credit accounts. You can get a free copy of your credit report once per year from each of the three credit reporting bureaus: Equifax, Experian, and Transunion. The website to check is www.annualcreditreport.com . It’s a good idea to review your report at least once per year to ensure accuracy and check for fraud. If someone were to fraudulently open a line of credit in your name, you might never know without checking your report.

A credit score is a snapshot of your credit risk at a point in time, based off of your credit report. Credit scores such as FICO range from 300-850, with the majority of Americans scoring between 600-800. For lenders, a higher score means a lower chance of default.

Lenders often charge higher interest rates when taking on higher risk, so a low credit score means a more expensive loan. Conversely, a higher credit score means a less expensive loan. With solid credit history you can pay less for many credit products like private loans, credit cards, insurance, auto loans, and mortgages.

Do Your Research

Before applying for a credit card, compare each potential card’s annual fees, interest rates, special rewards, and credit limit. Little differences can have major impacts. Once you choose a credit card and begin using it, make your payments on time and pay off your balance each month. Failure to do so can result in large fees and do serious damage to your credit score. Try not to carry a balance on the card; instead, make occasional and sensible purchases.

Components of Your Credit Score

- Payment History (35%) This is the largest factor and thus the best way to improve your score: make consistent, on-time payments. If you are more than 30 days late even once, that record remains on your credit report for 7 years and could result in a drop of 90 points or more in your credit score.

- Amount of Debt (30%) How much debt you have relative to your available credit makes up the second largest factor in your score. A good rule of thumb is to keep your debt utilization ratio ( amounts owed/total credit limit ) below 30%. Pretend you have two credit cards and both have a limit of $500. To stay within 30% you would spend no more than $300 between the two cards.

- Length of Credit History (15%) Lenders like to see long relationships with other lenders. One easy thing you can do to build credit history is open a no-annual-fee credit card, charge a few dollars each month, and pay it in full each month when the bill comes.

- New Credit (10%) Anytime you apply for a line of credit and a lender does what is called a "hard pull" on your credit score, your score can drop by a few points. This isn’t a big deal as new credit only makes up 10% of your score, but if you do this often enough it can substantially impact your score and ability to secure new credit. This information remains on your report for 2 years.

- Credit Mix (10%) Lenders like to see a variety of credit accounts in good standing because it signals that you are a responsible borrower. A person who is making on-time monthly payments on a credit card, an auto loan, and a student loan is considered less risky. Your access to different types of credit may be limited as a student, and most lenders realize this.

U.S. News and World Report Student Credit Card Survey

Each year, U.S. News and World Report conducts a survey of students who own a credit card. From the results, they identify and address common credit topics such as credit scores, costs of credit, and providing tools that help guide students with credit card best practices. View the survey and guide here .

Helpful Reads

For more information on effective credit building as a student, the following articles are useful.

- CreditCards.com Presents: 10 Ways Students Can Build Good Credit

- A College Student’s Guide to Building Credit

Saving and Investing

Figuring out how to secure your financial well being is one of the most important things you can do.

For many people, the path to financial security is with saving and investing. As a student, these topics may not yet be on your radar, but saving is a key concept for financial well-being. If you make saving a regular habit, even a small amount, you are building a foundation for financial success.

Tips on getting started with saving and investing

- Pay yourself first: This means that for every paycheck you receive, commit to putting an amount (even a small amount) aside in a savings account. An effective way of doing this is to have a set amount of your paycheck directly deposited into a savings account, separate from what you use for everyday expenses. You will be surprised how quickly your savings can grow.

- Keep track of your saving: People who track their savings tend to save more because it is on their mind. With online and mobile banking, there should be no excuse not to know exactly how much money you have.

- Set Goals: Setting financial goals is crucial. As a student, you may only have a few financial goals, but this is the perfect opportunity to hone your skills. Think of this scenario: You want to pay off a student loan before graduation, how will you accomplish this? How much do you need to work? To save? The better you do now, the easier accomplishing future goals will become.

Thinking ahead

Even now there may be long range financial goals that you start saving for. Here are some tips for investing in your long term financial goals.

- Plan ahead: As with any endeavor, advance planning is a way to figure out what you want, when you want it, and what you can do to achieve it. The sooner you start planning, the sooner you start accomplishing.

- Understand the time value of money /compound interest: This is the principle that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar in the future, because the dollar received today can earn interest up until the time the future dollar is received. The longer the time frame for investment, the more you can increase the income potential of your investment. On the flip side, waiting to invest can make it more difficult to achieve your financial goals. Discover how much waiting to save could cost you with the SEC compound interest calculator .

- Understand your objectives: As a general rule, the shorter your time frame for investing, the more conservative you should be. For example if you are in your twenties and trying save for a down payment on a house, you are going to want to put your money in a vehicle that ensures the least risk of losing your principle investment. When your time frame for investing is long, you can consider less conservative options. Retirement savings are an example. Starting young allows you to save for a longer period and allows time to make up for potential loses in a less conservative environment.

Do you need to file taxes? Are you aware of the tax benefits for Education? Find out the answers to these important tax related questions.

U.S. Federal Taxes: Overview

If you are planning to work in the US, then navigating the tax code is going to be a large part of your financial well being. Gathered here are aspects of the tax code that deal with education and college related expenses. While the information here is a good start, it is only a broad overview and not a complete guide to filing taxes. For specific questions or additional information, you may wish to visit the IRS website or consult a tax professional. International students should consult the Taxes & Social Security page of the Harvard International Office website.

Do I need to file taxes?

Determining whether or not you need to file taxes depends on two things: how much money you earned and how much was taken out (aka “withheld”) for taxes.

If your earned income is over a certain limit as determined by the IRS, you may be required to file taxes regardless of how much was withheld from your paycheck.

- As an example, a typical Harvard undergraduate was required to file (2018) taxes if their income (including taxable scholarships ) was equal to or greater than $12,000.

- The IRS strongly suggests that you file taxes, even if you are not required to do so. By filing your taxes, you may be eligible for a refund of some or all of the income withheld.

Types of tax benefits for education

The information provided here is intended only to get you started to learn about potential tax benefits related to higher education. It is important to note that there are eligibility restrictions and we strongly suggest visiting the IRS website directly for the most comprehensive information about tax benefits for higher education.

American Opportunity Credit

- This is a credit of up to $2,500 per eligible student based on Qualified Education Expenses paid during the tax year. The American Opportunity Credit can only be used for up to four years per eligible student.

Lifetime Learning Credit

- This is a credit of up to $2,000 per eligible student based on Qualified Education Expenses paid during the tax year. The Lifetime Learning Credit does not have a limit on the number of years it can be used per eligible student.

Tuition and Fees Deduction

- This is a deduction of up to $4,000 from your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) based on amounts paid for Qualified Education Expenses. This deduction can be claimed for multiple students and the maximum deduction in a tax year is $4,000.

Student Loan Interest Deduction

- If you are a student making payments on an education loan that is accruing interest, you may be able to deduct some or all of the interest you paid that year from your taxes.

- Your parents may be able to deduct some or all of the interest they paid on their loans, taken on your behalf, if they still claim you as a dependent. The current limit is $2,500 per year, subject to income restrictions.

Important questions to consider

What are Qualified Education Expenses?