Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Advertisement

Computational thinking integrated into the English language curriculum in primary education: A systematic review

- Published: 02 March 2024

Cite this article

- Xinlei Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7763-2781 1 ,

- Guoyuan Sang 2 ,

- Martin Valcke 1 &

- Johan van Braak 1

240 Accesses

Explore all metrics

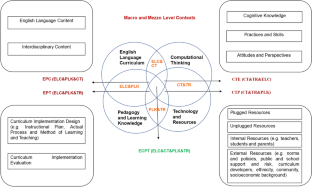

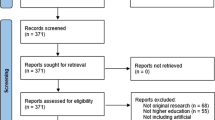

Computational thinking (CT) is valued as a thinking process that is required to adapt to the development of curriculum in primary education. In the context of modern information technology, English as a language subject emphasizes the necessity for changes in both learning and teaching modes. However, there is a lack of up-to-date synthesis research and a comprehensive overview surrounding CT integrated into English language curriculum learning and teaching in primary education. To address this research gap, this study conducted a systematic literature review on CT in the primary English curriculum, based on papers published from 2011 to 2021. The purpose of this review is to systematically examine and present empirical evidence on how CT can be integrated into the teaching and learning of the primary English language curriculum in educational contexts. The review was conducted based on the PRISMA 2020 statement and presents a synthesis of 32 articles. The CT-TPACK model was adopted as a lens and framework to analyze these articles. The results indicate that the relationship among CT, content knowledge of English language curriculum, pedagogy and learning knowledge, technology and resources is highlighted. Research on the integration of CT into English courses using unplugged activities is still insufficient. The research about how teachers and students use CT to support content knowledge of the English language curriculum in various educational contexts is still in its infancy.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Students’ voices on generative AI: perceptions, benefits, and challenges in higher education

Ethical principles for artificial intelligence in education.

Artificial intelligence in higher education: the state of the field

Data availability.

Not applicable.

Angeli, C., Voogt, J., Fluck, A., Webb, M., Cox, M., Malyn-Smith, J., & Zagami, J. (2016). A K-6 computational thinking curriculum framework: Implications for teacher knowledge. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 19 (3), 47–57.

Google Scholar

Archambault, L. M., & Barnett, J. H. (2010). Revisiting technological pedagogical content knowledge: Exploring the TPACK framework. Computers and Education, 55 (4), 1656–1662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.07.009

Article Google Scholar

Barr, V., & Stephenson, C. (2011). Bringing computational thinking to K-12: What is involved and what is the role of the computer science education community? ACM Inroads, 2 (1), 48–54.

Bell, T., Alexander, J., Freeman, I., & Grimley, M. (2009). Computer science unplugged: School students doing real computing without computers. The New Zealand Journal of Applied Computing and Information Technology, 13 (1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1145/2670473.2670512

Bocconi, S., Chioccariello, A., Dettori, G., Ferrari, A., & Engelhardt, K. (2016). Developing computational thinking in compulsory education: Implications for policy and practice . Resource document (EUR 28295 EN). https://doi.org/10.2791/792158

Brennan, K., & Resnick, M. (2012). New frameworks for studying and assessing the development of computational thinking. AERA, 1 , 1–25.

Bundy, A. (2007). Computational Thinking is Pervasive. Journal of Scientific and Practical Computing, 1 (2), 67–69.

Burke, Q., & Kafai, Y. B. (2012). The writers’ workshop for youth programmers: Digital storytelling with Scratch in middle school classrooms. In Proceedings of the 43rd ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 433–438). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2157136.2157264

Century, J., Ferris, K. A., & Zuo, H. (2020). Finding time for computer science in the elementary school day: A quasi-experimental study of a transdisciplinary problem-based learning approach. International Journal of STEM Education, 7 (1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00218-3

Computer Sience Teachers Association (CSTA), & International Society for Technology Education (ISTE). (2011). Operational definition of computational thinking for K-12 education. http://www.iste.org/docs/ct-documents/computational-thinking-operational-definition-flyer.pdf . Accessed 20 January 2023

Costa, S., & Pessoa, T. (2016). Using Scratch to teach and learn English as a foreign language in elementary school. International Journal of Education and Learning Systems, 1 , 207–212.

Domenach, F., Araki, N., & Agnello, M. F. (2021). Disrupting discipline based learning: Integrating English and programming education. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 18 (1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2020.1807986

Dong, Y., Cateté, V., Jocius, R., Lytle, N., Barnes, T., Albert, J., Joshi, D., Robinson, R., & Andrews, A. (2019). PRADA: A practical model for integrating computational thinking in K-12 education. In Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 906–912). https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287431

Duncan, C., Bell, T., & Atlas, J. (2017). What do the teachers think? Introducing computational thinking in the primary school curriculum. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth Australasian Computing Education Conference (pp. 65–74). New York: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3013499.3013506

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62 (1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Falkner, K., Vivian, R., & Falkner, N. (2018). Supporting computational thinking development in K-6. In Proceedings - 2018 International Conference on Learning and Teaching in Computing and Engineering (LaTICE) (pp. 126–133). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/LaTICE.2018.00031

Federici, S., Sergi, E., & Gola, E. (2019). Easy prototyping of multimedia interactive educational tools for language learning based on block programming. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2019) (pp. 140–153). https://doi.org/10.5220/0007766201400153

Garvin, M., Killen, H., Plane, J., & Weintrop, D. (2019). Primary school teachers’ conceptions of computational thinking. In Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 899–905). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287376

Graham, C. R. (2011). Theoretical considerations for understanding technological pedagogical content knowledge ( TPACK ). Computers & Education, 57 (3), 1953–1960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.04.010

Grover, S., & Pea, R. (2018). Computational thinking: A competency whose time has come. In Computer science education: Perspectives on teaching and learning in school . London: Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350057142.ch-003

Grover, S., & Pea, R. (2013). Computational thinking in K-12: A review of the state of the field. Educational Researcher, 42 (1), 38–43. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12463051

Hladik, S., Behjat, L., & Nygren, A. (2017). Modified CDIO framework for elementary teacher training in computational thinking. In Proceedings of the 13th International CDIO Conference . Calgary, Canada.

Horwitz, E. K. (1986). Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of a foreign language anxiety scale. TESOL Quarterly, 20 (3), 559–562. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586302

Houchins, J., Cully, K., Boulden, D.C., Oliver, K., Smith, A., Minogue, J., Mott, B., Elsayed, R., Cheuoua, A.H. & Ringstaff, C. (2021). Teacher perspectives on a narrative-centered learning environment to promote computationally-rich science learning through digital storytelling. In Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 35–40). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Hsu, T. C., & Liang, Y. S. (2021). Simultaneously improving computational thinking and foreign language learning: Interdisciplinary media with plugged and unplugged approaches. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 59 (6), 1184–1207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633121992480

Hsu, T. C., Chang, C., & Liang, Y. S. (2023). Sequential Behaviour Analysis of Interdisciplinary Activities in Computational Thinking and EFL Language Learning with Game-Based Learning. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 16 (2), 256–265. https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2023.3249749

Israel, M., Liu, R., Yan, W., Sherwood, H., Martin, W., Fancseli, C., Rivera-Cash, E., & Adair, A. (2022). Understanding barriers to school-wide computational thinking integration at the elementary grades: Lessons from three schools. In Computational thinking in PreK-5: Empirical evidence for integration and future directions (pp. 64–71). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3507951.3519289

Jacob, S. R., & Warschauer, M. (2018). Computational thinking and literacy. Journal of Computer Science Integration, 1 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.26716/jcsi.2018.01.1.1

Article CAS Google Scholar

Jacob, S., Nguyen, H., Tofel-Grehl, C., Richardson, D., & Warschauer, M. (2018). Teaching computational thinking to English learners. NYS TESOL Journal, 5 (2), 12–24.

Jacob, S., Nguyen, H., Garcia, L., Richardson, D., & Warschauer, M. (2020). Teaching computational thinking to multilingual students through inquiry-based learning. In 2020 Research on Equity and Sustained Participation in Engineering, Computing, and Technology (RESPECT) (pp. 1–8). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/RESPECT49803.2020.9272487

Jenkins, C. (2015). Poem Generator: A comparative quantitative evaluation of a microworlds- based learning approach for teaching English. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 11 (2), 153–167.

Jocius, R., Joshi, D., Dong, Y., Robinson, R., Catete, V., Barnes, T., Albert, J., Andrews, A., & Lytle, N. (2020). Code, connect, create: The 3C professional development model to support computational thinking infusion. In Proceedings of the 51st ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 971–977). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3328778.3366797

Jong, M. S. Y., Geng, J., Chai, C. S., & Lin, P. Y. (2020). Development and predictive validity of the computational thinking disposition questionnaire. Sustainability, 12 (11), 4459. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114459

Kakavas, P., Ugolini, F. C., Marconi, U. G., & Marconi, U. G. (2019). Computational thinking in primary education : A systematic literature review. Research on Education and Media, 11 (2), 64–94. https://doi.org/10.2478/rem-2019-0023

Kale, U., Akcaoglu, M., Cullen, T., Goh, D., Devine, L., Calvert, N., & Grise, K. (2018). Computational What? Relating Computational Thinking to Teaching. TechTrends, 62 , 574–584.

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., & Cain, W. (2013). What is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)? Journal of Education, 193 (3), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741319300303

Kong, S. C., & Lai, M. (2021). A proposed computational thinking teacher development framework for K-12 guided by the TPACK model. Journal of Computers in Education, 9 (3), 379–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-021-00207-7

Liu, C. C., Chen, W. C., Lin, H. M., & Huang, Y. Y. (2017). A remix-oriented approach to promoting student engagement in a long-term participatory learning program. Computers and Education, 110 (300), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.03.002

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Lodi, M., & Martini, S. (2021). Computational Thinking, Between Papert and Wing. Science and Education, 30 (4), 883–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-021-00202-5

Article ADS Google Scholar

Lu, J. J., & Fletcher, G. H. L. (2009). Thinking about computational thinking. In Proceedings of the 40th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 260–264). New York, NY: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1508865.1508959

Mannila, L., Dagiene, V., Demo, B., Grgurina, N., Mirolo, C., Rolandsson, L., & Settle, A. (2014). Computational Thinking in K-9 Education. In Proceedings of the Working Group Reports of the 2014 on Innovation & Technology in Computer Science Education Conference (pp. 1–29). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2713609.2713610

Mensing, K., Mak, J., Bird, M., & Billings, J. (2013). Computational, model thinking and computer coding for U.S. Common Core Standards with 6- to 12-year-old students. In IEEE 11th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA) (pp. 17–22). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICETA.2013.6674397

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108 (6), 1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Moreno-León, J., & Robles, G. (2015). Computer programming as an educational tool in the English classroom a preliminary study. In 2015 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 961–966). Tallin, Estonia: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2015.7096089

Moudgalya, S. K., Yadav, A., Sands, P., Vogel, S., & Zamansky, M. (2021). Teacher views on computational thinking as a pathway to computer science. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education (pp. 262–268). https://doi.org/10.1145/3430665.3456334

Mouza, C., Yang, H., Pan, Y. C., Ozden, S. Y., & Pollock, L. (2017). Resetting educational technology coursework for pre-service teachers: A computational thinking approach to the development of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK). Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 33 (3). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3521

Mueller, J., Beckett, D., Hennessey, E., & Shodiev, H. (2017). Assessing computational thinking across the curriculum. In P. J. Rich & C. B. Hodges (Eds.), Emerging research, practice, and policy on computational thinking (pp. 251–267). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52691-1_16

Nesiba, N., Pontelli, E., & Staley, T. (2015). DISSECT: Exploring the relationship between computational thinking and English literature in K-12 curricula. In Proceedings of Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (pp. 249–256). El Paso, Texas: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2015.7344063

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372 (71), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas . Basic Books.

Papert, S. (1991). Situating constructionism. In I. Harel & S. Papert (Eds.), Constructionism (pp. 1–11). Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Papert, S. (1996). An exploration in the space of mathematics educations. International Journal of Computers for Mathematical Learning, 1 (1), 95–123.

Parsazadeh, N., Cheng, P. Y., Wu, T. T., & Huang, Y. M. (2021). Integrating Computational Thinking Concept Into Digital Storytelling to Improve Learners’ Motivation and Performance. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 59 (3), 470–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633120967315

Pektas, E., & Sullivan, F. R. (2021). Storytelling through programming in Scratch: Interdisciplinary integration in the elementary English language arts classroom. In Proceedings of the Fifth Asia Pacific Society for Computers in Education International Conference on Computational Thinking and STEM Education (pp. 1–5).

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53 (3), 801–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164493053003024

Poh, L. G., Adnan, A., & Hassan, H. (2020). Computational thinking in storytelling projects in an English language classroom. In Proceedings of International Conference on The Future of Education IConFEd 2020 (pp. 341–350).

Porras-Hernández, L. H., & Salinas-Amescua, B. (2013). Strengthening TPACK: A Broader notion of context and the use of teacher’s narratives to reveal knowledge construction. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 48 (2), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.48.2.f

Román-González, M., Pérez-González, J. C., & Jiménez-Fernández, C. (2017). Which cognitive abilities underlie computational thinking? Criterion validity of the Computational Thinking Test. Computers in Human Behavior, 72 , 678–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.047

Sabitzer, B., Demarle-Meusel, H., & Jarnig, M. (2018). Computational thinking through modeling in language lessons. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 1913–1919). Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2018.8363469

Saito-Stehberger, D., Garcia, L., & Warschauer, M. (2021). Modifying curriculum for novice computational thinking elementary teachers and English language learners. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education V. 1 (pp. 136–142). New York: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3430665.3456355

Sherwood, H., Yan, W., Liu, R., Martin, W., Adair, A., Fancsali, C., Rivera-Cash, E., Pierce, M., & Israel, M. (2021). Diverse approaches to school-wide computational thinking integration at the elementary grades: A Cross-case analysis. In Proceedings of the 52nd ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 253–259). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3408877.3432379

Simmonds, J., Gutierrez, F. J., Casanova, C., Sotomayor, C., & Hitschfeld, N. (2019). A teacher workshop for introducing computational thinking in rural and vulnerable environments. In Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 1143–1149). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287456

Smith, S., & Burrow, L. (2016). Programming multimedia stories in Scratch to integrate computational thinking and writing with elementary students. Journal of Mathematics Education., 9 (2), 119–131.

So, H. J., Jong, M. S. Y., & Liu, C. C. (2020). Computational Thinking Education in the Asian Pacific Region. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 29 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00494-w

Strachman, A., Shochet, J., & Hosford, G. (2020). StoryMode: An exploratory test of teaching coding within ELA projects. In Proceedings of the 2020 Connected Learning Summit (pp. 169–176). https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/13530038.v2

Tatar, C., & Eseryel, D. (2019). A literature review: Fostering computational thinking through game-based learning in K-12. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Convention of the Association for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 288–297).

Vogel, S., Hoadley, C., Ascenzi-Moreno, L., & Menken, K. (2019). The role of translanguaging in computational literacies: Documenting middle school bilinguals’ practices in computer science integrated units. In Proceedings of the 50th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 1164–1170). https://doi.org/10.1145/3287324.3287368

Voogt, J., Fisser, P., Pareja Roblin, N., Tondeur, J., & van Braak, J. (2013). Technological pedagogical content knowledge - A review of the literature. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29 (2), 109–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2012.00487.x

Voogt, J., Fisser, P., Good, J., Mishra, P., & Yadav, A. (2015). Computational thinking in compulsory education : Towards an agenda for research and practice. Education and Information Technologies, 20 (4), 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-015-9412-6

Weng, X., Xie, H., & Wong, G. K. W. (2018). Guiding principles of visual-based programming for children’s language learning. International Journal of Services and Standards, 12 (3/4), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSS.2018.100223

Weng, X., & Wong, G. K. (2017). Integrating computational thinking into English dialogue learning through graphical programming tool. In Proceedings of the 6th international conference on teaching, assessment, and learning for engineering (TALE) (pp. 320–325). Hong Kong, China: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/TALE.2017.8252356

Wing, J. M. (2006). Computational Thinking. Communications of the ACM, 49 (3), 33–35.

Wing, J. M. (2008). Computational thinking and thinking about computing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society a: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 366 (1881), 3717–3725. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2008.0118

Article ADS MathSciNet Google Scholar

Wolz, U., Stone, M., Pearson, K., Pulimood, S. M., & Switzer, M. (2011). Computational thinking and expository writing in the middle school. ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 11 (2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1145/1993069.1993073

Yadav, A., Mayfield, C., Zhou, N., Hambrusch, S., & Korb, J. T. (2014). Computational thinking in elementary and secondary teacher education. ACM Transactions on Computing Education (TOCE), 14 (1), 1–16.

Yadav, A., Hong, H., & Stephenson, C. (2016). Computational thinking for all: Pedagogical approaches to embedding 21st century problem solving in K-12 classrooms. TechTrends, 60 (6), 565–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0087-7

Yadav, A., Stephenson, C., & Hong, H. (2017). Computational thinking for teacher education. Communications of the ACM, 60 (4), 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1145/2994591

Yadav, A., Zhou, N., Mayfield, C., Hambrusch, S., & Korb, J. T. (2011). Introducing computational thinking in education courses. In Proceedings of the 42nd ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education (pp. 465–470). Dallas, TX: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1953163.1953297

Yeni, S., Nijenhuis-Voogt, J., Hermans, F., & Barendsen, E. (2022). An integration of computational thinking and language arts: The contribution of digital storytelling to students’ learning. In Proceedings of the 17th Workshop in Primary and Secondary Computing Education (pp. 1–10). https://doi.org/10.1145/3556787.3556858

Zaman, H. B., Ahmad, A., Nordin, A., Aliza, A., Ang, M. C., Shaiza, N. A., et al. (2019). Computational thinking (CT) problem solving orientation based on logic-decomposition-abstraction (LDA) by rural elementary school children using visual-based presentations. In Advances in Visual Informatics - Proceedings of the 6th International Visual Informatics Conference, IVIC 2019 (pp. 713–728). Bangi, Malaysia. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-34032-2_64

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the China Scholarship Council (CSC), grant number CSC201906040214.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University, Campus Dunant, Henri Dunantlaan 2, 9000, Ghent, Belgium

Xinlei Li, Martin Valcke & Johan van Braak

Faculty of Education, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, 100875, China

Guoyuan Sang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization: Xinlei Li and Johan van Braak; Methodology: Xinlei Li; Formal analysis and investigation: Xinlei Li and Johan van Braak; Writing—original draft preparation: Xinlei Li; Writing—review and editing: Xinlei Li, Guoyuan Sang, Martin Valcke and Johan van Braak; Resources: Xinlei Li, Guoyuan Sang, Martin Valcke and Johan van Braak; Supervision: Johan van Braak.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Xinlei Li .

Ethics declarations

Informed of consent, institutional review board, conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Li, X., Sang, G., Valcke, M. et al. Computational thinking integrated into the English language curriculum in primary education: A systematic review. Educ Inf Technol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12522-4

Download citation

Received : 30 June 2023

Accepted : 26 January 2024

Published : 02 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12522-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Computational thinking

- English language curriculum

- Teaching and learning

- Primary education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

British Council Malaysia

- English schools

- myClass Login

- Show search Search Search Close search

- English courses

- Kids and teens

- Learning resources for parents

Critical Thinking for Primary Students

Throughout their time at school, learners are expected to compare, contrast, evaluate, understand, organise, and classify information – in other words, think critically. This empowers students to make decisions and deal with problems confidently, which are essential skills in school and the rest of their lives. But how soon can we start encouraging our children to think critically about the world around them? It seems like a lot to ask of a 6-year-old, but by taking some small steps, we can develop our children’s critical thinking skills from an early age, setting them up for secondary education, higher education, and eventually a career.

In the primary classroom, teachers use many different techniques to encourage critical thinking, especially in English language teaching, as language is a gateway for understanding other subjects which require a critical thinking mindset. One technique used is to give students tools in order to think critically, such as giving students questions that they should use when faced with a problem, like ‘How would someone else feel about this?’, ‘Is it fair?’, or ‘What can I do about this?’ These, and other questions, can be displayed around the classroom for students to see and use throughout the lesson, until they are in the habit of using them automatically.

Giving students critical challenges is often difficult, but vital in pushing children to think more critically. Teachers should ask for answers which go beyond repeating information or expressing likes or dislikes, as we want students to be challenged to think about what would make the most sense, or to decide between multiple options. This also extends to assessing performance. When making quizzes and tests, teachers need to make sure that questions are designed to show critical thinking skills, as opposed to purely memory. Sometimes, a wrong answer with an interesting explanation shows a stronger mastery of critical thinking processes than a correct answer with no explanation.

Most importantly, teachers need to create a supportive environment in which students are free to use their critical thinking ability without fear of getting the wrong answer. This is done by praising effort as well as accuracy; asking students for their opinions; and encouraging students to give reasons for their choices.

To continue the work of your child’s teacher at home, there are many things you can do as a parent to foster critical thinking skills in your child. The most important is to allow your child to try things without fear of failure. When children are scared of failure, they are more likely to turn to memorisation, which feels safer, as opposed to analysis. You can also ask, and get your child to ask, the big 6 critical questions: ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘when’, ‘why’, and ‘how’. As parents we can often be scared of being questioned, but questions show that our children what to gain a deeper understanding of their world and become independent thinkers. Finally, you can encourage your child to study a range of topics, consume media from different platforms, and play many different games. By broadening their experience, children will start to make links and comparisons, aided by your questions and encouragement.

At the British Council, our primary teachers use these techniques and many others to help your children develop a key skill they need to become successful young people. The materials for our primary courses focus not only on language acquisition, but also on analysis, making connections, and formulating opinions, in order to set our students on the path to becoming independent and critical thinkers.

- Our Mission

Boosting Critical Thinking Across the Curriculum

Visible thinking routines that encourage students to document and share their ideas can have a profound effect on their learning.

In my coaching work with schools, I am often requested to model strategies that help learners think deeply and critically across multiple disciplines and content areas. Many teachers are looking to adapt research-based methods to help students think about content in meaningful ways by making connections to previous learning, asking relevant questions, displaying understanding through learning artifacts , and identifying their challenges with the material.

Educator Alfred Mander said, “Thinking is skilled work. It is not true that we are naturally endowed with the ability to think clearly and logically—without learning how and without practicing.”

Visible thinking routines can be an excellent and simple way to start using systematic but flexible approaches to teaching thinking dispositions to young people at any grade level. Focusing on thinking types, powerful routines can strengthen learners’ ability to analyze, synthesize (design), and question effectively. Classroom teachers want these skills to become habits, making students the most informed stakeholder in their own learning.

Not to be confused with visible learning research by John Hattie , Visible Thinking is a research-based initiative by Harvard’s Project Zero with more than 30 routines aimed at making learning the consequence of good thinking dispositions . Students begin to comprehend content through thinking routines composed of short questions or a series of steps. During routines, their learning becomes visible because their ideas are documented, voiced, discussed with others, and reflected on.

For example, the routine See, Think, Wonder can be used to get students to analyze and interpret graphs, text, infographics, or video during the entry event of project-based learning units or daily lessons. Guiding students to have rich and lively discussions about their thoughts, interpretations, and wonderings (questions) can help teachers decide on appropriate lessons and next steps.

Another effective visible thinking routine is Connect, Extend, Challenge (CEC). Learners can use CEC to organize, clarify, and simplify complex information on graphic organizers. The graphic organizer becomes a kinesthetic activity for creating an informational artifact that students can refer to as the lesson or unit progresses.

Here are some creative but simple ways to carry out these two routines across multiple classrooms.

See, Think, Wonder

See, Think, Wonder can be leveraged as a thinking routine to launch engagement and inquiry in daily lessons by introducing an interesting object (graphic, artifact, etc.). The idea is for students to think carefully about why the object looks or is a certain way. Teachers introduce the following question prompts to guide students’ thinking:

- What do you see?

- What do you think about that?

- What does it make you wonder?

When the routine is new, sometimes young children may not know where to begin expressing themselves—this is where converting the above question prompts into sentence stems, “I see…,” “I think…,” and “I wonder…,” comes into play. For students struggling with analytical skills, it’s empowering for them to accept themselves where they currently are—learning how to analyze critically can be achieved over time and with practice. Teachers can help them build confidence with positive reinforcement .

Adapt the routine to meet the needs of your kids, which may be to have them work individually or to engage with classmates. I use it frequently—especially when introducing emotionally compelling graphics to students learning about environmental issues (e.g., the UN’s Goals for Sustainable Development) and social issues . This is useful in helping them better understand how to interpret graphs, infographics, and what’s happening in text and visuals. Furthermore, it also promotes interpretations, analysis, and questioning.

Content teachers can use See, Think, Wonder to get learners thinking critically by introducing graphics that reinforce essential academic information and follow up the routine with lessons and scaffolds to support students’ ideas and interpretations.

Connect, Extend, Challenge

CEC is a powerful visible learning routine to help students connect previous learning to new learning and identify where they are struggling in various educational concepts. Taking stock of where they are stuck in the material is as vital as articulating their connections and extensions. Again, they might struggle initially, but here’s where front-loading vocabulary and giving them time to talk through challenges can help.

A good place to introduce CEC is after students have analyzed or observed something new. This works as a natural next step to have them dig deeper with reflection and use what they learned in the analysis process to create their own synthesis of ideas. I also like to use CEC after engaging them in the See, Think, Wonder routine and at the end of a unit.

Again, learners can work individually or in small groups. Teachers can also have them move into the routine after reading an article or some form of targeted informational text where the learning is critical to moving forward (e.g., proportional relationships, measurement, unit conversion). Regardless of your approach, Project Zero suggests having learners reflect on the following question prompts:

- How is the _____ connected to something you already know?

- What new ideas or impressions do you have that extended your thinking in new directions?

- What is challenging or confusing? What do you need to improve your understanding?

I like to have learners in small groups answer a version of the question prompts in a simple three-column graphic organizer. The graphic organizer can also become a road map for prioritizing the next steps in learning for students of all ages. Here are some visual examples of how I used the activity with educators in a professional development session targeting emotional intelligence skills.

More Visible Thinking Resources

- Project Zero’s Thinking Routine Toolbox : Access to core thinking routines

- Making Thinking Visible: How to Promote Engagement, Understanding, and Independence for All Learners , by Ron Ritchhart, Mark Church, and Karin Morrison

- Creating Cultures of Thinking: The 8 Forces We Must Master to Truly Transform Our Schools , by Ron Ritchhart

Critical Thinking in Primary Schools

by Open Minds Foundation | Uncategorized

Authored by John Snell

Developing critical thinking skills in primary schools can appear to be a daunting challenge for educators in the UK. After all, how do you begin to develop these skills in children as young as four? Over 25 years working in education as a classroom teacher and now head teacher, I have always been interested in the purpose of education – and to add value to the process of helping children learn.

It is all too apparent to me that education is far more than the acquisition of knowledge, and it is our essential duty as educators to prepare children for their future lives. Knowledge itself will not equip children with the skills necessary to navigate their way through life, nor it could be argued, will it prepare them for future careers. So where do we begin? How do schools look to teach these skills while also covering the statutory national curriculum?

While finding time in the school day to teach critical thinking skills may be a challenge, I believe it is possible to teach these skills alongside the day to day teaching. In many ways, I see this as a hugely valuable and relevant way to develop understanding, as the content of the lessons is then presented more deeply, and for our learners is more relevant.

Let me explain how this might look in a classroom. Imagine a maths lesson (or any other lesson) where the teacher is explaining a concept. For the younger children, this might be a simple calculation – what is 5+5? In an average class, it is likely that most children will be able to give a correct answer, however is this enough? In fact, is the correct answer what we are looking for at all? This might seem counterintuitive to many outside the profession but here is where there is a fantastic opportunity to develop deeper thinking skills than would ordinarily be covered. In many classrooms, there may be a short acknowledgment that 10 is the correct answer – and that 9 or 11 are incorrect – and, due to the amount of subject coverage required to be taught in a school day, the teacher would quickly move on to the next question. My point here is that teachers should stop here and ask, ‘how do you know?’ Simply put, can the children explain deeply, how they know 5+5=10. From my experience, children initially look blank or reply, ‘because it is’, however by probing further, children are actually able to explain ‘10’ through using practical resources and the fact that they know their number bonds – and how numbers/amounts work. Many children will, if challenged, be able to demonstrate this through practical equipment or through using their fingers to count. This conversation needn’t be long (indeed I would not advocate the ‘how do you know?’ strategy to every question asked during the school day!) however I believe it is a simple way to begin to enable children to think critically.

This can also be applied to any subject – how do you know Mount Everest is the highest mountain? How do you know that a word is an adjective? By employing this approach day to day, children are developing their ability to question what they know and think deeply. Further up the school, this skill is explored more literally through studies in propaganda relating to World Wars, advertising and other more ‘obvious’ lessons that teach children to be critical in their thinking. I believe this simple approach not only adds value to learning but helps prepare our children for a future life where they will question what they are told and have the skills to avoid being manipulated and coerced, whether by media, politics or otherwise.

- Developing critical thinking through play

- How individuals can avoid sharing mis- and disinformation

- The Martyr Complex and Conspiracy Theorists

- The global risk of misinformation and disinformation

- How to SCAMPER

- Event Booking

- School Support

- Publications

Search form

- Child Protection

- PLC Webinars

- Literacy at Home

- PLC/CTB E-Bulletins

- PLC/CTB Seminar 2019

- Reading Recovery

- Team Teaching

- English as an Additional Language

- Wellbeing in Education

- Mathematics

- Let's Talk

- Remote Teaching

- Lesson Study

- Physical Education

- Misneach (Newly Appointed Principal)

- Forbairt (Experienced School Leaders)

- Tánaiste (Deputy Principals)

- Comhar: Middle Leadership

- One Day Seminar

- Webinar 5 (April 2022)

Primary Language Curriculum Webinar 5 focuses on the Primary Language Curriculum and Critical Literacy.

Is é Curaclam Teanga na Bunscoile agus Litearthacht Chriticiúil atá mar fhócas i gCeardlann Ghréasáin 5.

English-medium schools can access the English version of the webinar, and its associated support material, in the first section below.

Is féidir le scoileanna lán-Ghaeilge agus Gaeltachta teacht ar leagan Gaeilge den cheardlann ghréasáin, agus na hábhair thacaíochta a ghabhann léi, sa dara roinn thíos.

Overview of PLC Webinar 5:

The main focus of PLC Webinar 5 will be to explore critical literacy, as one of the key aspects of section 6 of the curriculum (The Curriculum in Practice). This webinar will provide teachers with an opportunity to explore what developing critical liteacy may look like in practice. Sections from a discussion on critical lteracy among a panel of teachers are interspersed throughout the webinar, as are examples of classroom practice.

Support Material:

You will need to p ause the webinar at various intervals to engage with a range of reflective tasks. A prompt sheet has been developed to guide teachers through the various tasks involved. We recommend that you print one copy of the prompt sheet per teacher/group in preparation for your school closure. Depending on your context and school size, teachers may work individually, in pairs or in groups.

Please note that there is a 30 second pause in the webinar video at each pause point.

Links to all relevant documents/material are available below. You can either access the material online, or download PDF versions of the documents.

PLC Webinar 5-Critical Literacy.mp4 from PDST on Vimeo .

Additional Resources and Supports

Forléargas ar Cheardlann Ghréasáin CTB 5:

Príomhfhócas na ceardlainne seo ná chun iniúchadh a dhéanamh ar Litearthacht Chriticiúil , mar cheann de na príomhghnéithe de chaibidil 6 de Churaclam Teanga na Bunscoile (Curaclam Teanga na Bunscoile i bhfeidhm). Cuirfear deiseanna ar fáil do mhúinteoirí cíoradh a dhéanamh ar an gcaoi go bhféadfaí litearthacht chriticiúil a fhorbairt. Cloisfimid ó mhúinteoirí ag plé litearthacht chriticiúil ina gcleachtais féin agus feicfimid samplaí de chleachtais ranga.

Ábhar Tacaíochta:

Beidh gá daoibh an cheardlann ghréasáin a chur ar sos ó am go céile chun tabhairt faoi roinnt tascanna machnaimh. Tá bileog leide ar fáil mar threoir agus na tascanna seo ar bun agaibh. Molaimid go ndéanfar cló ar chóip amháin den bhileog leide in aghaidh an mhúinteora/ghrúpa in ullmhúchán don dúnadh scoile. Ag brath ar do chomhthéacs agus ar mhéid na scoile, d’fhéadfadh múinteoirí oibriú ina n-aonar, i mbeirteanna, nó i ngrúpaí.

Tabhair faoi deara go bhfuil sos 30 soicind sa cheardlann ghréasáin ag gach pointe sosa.

Tá naisc go dtí na doiciméid/ábhair chuí ar fáil thíos. Is féidir rochtain a fháil orthu ar líne, nó is féidir leagan PDF dóibh a íoslódáil.

CTB Ceardlann Ghreasain.mp4 from PDST on Vimeo .

Físeán Dea-chleachtais breise

Literacy/Litearthacht

- Webinar 1 (Jan 2020)

- Webinar 2 (May 2020)

- Webinar 3 (August 2021)

- Webinar 4 (January 2022)

- Webinar 6 (August 2022)

- Webinar 7 (January 2023)

- Webinar 8 (April 2023)

- Language Learning

14 Joyce Way, Park West Business Park, Nangor Road, Dublin 12 User Login | Teacher Login | Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

- Order Tracking

- Create an Account

200+ Award-Winning Educational Textbooks, Activity Books, & Printable eBooks!

- Compare Products

Reading, Writing, Math, Science, Social Studies

- Search by Book Series

- Algebra I & II Gr. 7-12+

- Algebra Magic Tricks Gr. 2-12+

- Algebra Word Problems Gr. 7-12+

- Balance Benders Gr. 2-12+

- Balance Math & More! Gr. 2-12+

- Basics of Critical Thinking Gr. 4-7

- Brain Stretchers Gr. 5-12+

- Building Thinking Skills Gr. Toddler-12+

- Building Writing Skills Gr. 3-7

- Bundles - Critical Thinking Gr. PreK-9

- Bundles - Language Arts Gr. K-8

- Bundles - Mathematics Gr. PreK-9

- Bundles - Multi-Subject Curriculum Gr. PreK-12+

- Bundles - Test Prep Gr. Toddler-12+

- Can You Find Me? Gr. PreK-1

- Complete the Picture Math Gr. 1-3

- Cornell Critical Thinking Tests Gr. 5-12+

- Cranium Crackers Gr. 3-12+

- Creative Problem Solving Gr. PreK-2

- Critical Thinking Activities to Improve Writing Gr. 4-12+

- Critical Thinking Coloring Gr. PreK-2

- Critical Thinking Detective Gr. 3-12+

- Critical Thinking Tests Gr. PreK-6

- Critical Thinking for Reading Comprehension Gr. 1-5

- Critical Thinking in United States History Gr. 6-12+

- CrossNumber Math Puzzles Gr. 4-10

- Crypt-O-Words Gr. 2-7

- Crypto Mind Benders Gr. 3-12+

- Daily Mind Builders Gr. 5-12+

- Dare to Compare Math Gr. 2-7

- Developing Critical Thinking through Science Gr. 1-8

- Dr. DooRiddles Gr. PreK-12+

- Dr. Funster's Gr. 2-12+

- Editor in Chief Gr. 2-12+

- Fun-Time Phonics! Gr. PreK-2

- Half 'n Half Animals Gr. K-4

- Hands-On Thinking Skills Gr. K-1

- Inference Jones Gr. 1-6

- James Madison Gr. 10-12+

- Jumbles Gr. 3-5

- Language Mechanic Gr. 4-7

- Language Smarts Gr. 1-4

- Mastering Logic & Math Problem Solving Gr. 6-9

- Math Analogies Gr. K-9

- Math Detective Gr. 3-8

- Math Games Gr. 3-8

- Math Mind Benders Gr. 5-12+

- Math Ties Gr. 4-8

- Math Word Problems Gr. 4-10

- Mathematical Reasoning Gr. Toddler-11

- Middle School Science Gr. 6-8

- Mind Benders Gr. PreK-12+

- Mind Building Math Gr. K-1

- Mind Building Reading Gr. K-1

- Novel Thinking Gr. 3-6

- OLSAT® Test Prep Gr. PreK-K

- Organizing Thinking Gr. 2-8

- Pattern Explorer Gr. 3-9

- Practical Critical Thinking Gr. 8-12+

- Punctuation Puzzler Gr. 3-8

- Reading Detective Gr. 3-12+

- Red Herring Mysteries Gr. 4-12+

- Red Herrings Science Mysteries Gr. 4-9

- Science Detective Gr. 3-6

- Science Mind Benders Gr. PreK-3

- Science Vocabulary Crossword Puzzles Gr. 4-6

- Sciencewise Gr. 4-12+

- Scratch Your Brain Gr. 2-12+

- Sentence Diagramming Gr. 3-12+

- Smarty Pants Puzzles Gr. 3-12+

- Snailopolis Gr. K-4

- Something's Fishy at Lake Iwannafisha Gr. 5-9

- Teaching Technology Gr. 3-12+

- Tell Me a Story Gr. PreK-1

- Think Analogies Gr. 3-12+

- Think and Write Gr. 3-8

- Think-A-Grams Gr. 4-12+

- Thinking About Time Gr. 3-6

- Thinking Connections Gr. 4-12+

- Thinking Directionally Gr. 2-6

- Thinking Skills & Key Concepts Gr. PreK-2

- Thinking Skills for Tests Gr. PreK-5

- U.S. History Detective Gr. 8-12+

- Understanding Fractions Gr. 2-6

- Visual Perceptual Skill Building Gr. PreK-3

- Vocabulary Riddles Gr. 4-8

- Vocabulary Smarts Gr. 2-5

- Vocabulary Virtuoso Gr. 2-12+

- What Would You Do? Gr. 2-12+

- Who Is This Kid? Colleges Want to Know! Gr. 9-12+

- Word Explorer Gr. 6-8

- Word Roots Gr. 3-12+

- World History Detective Gr. 6-12+

- Writing Detective Gr. 3-6

- You Decide! Gr. 6-12+

Your Search: Kindergarten (Ages 5-6)

Please wait...

Advanced Search Results

Items 1 - 6 of 64

- You're currently reading page 1

Mathematical Reasoning™ Level A

Mathematics

- Multiple Award Winner

- Paperback Book - $38.99

- eBook - $38.99

Building Thinking Skills® Primary

Grades: K-1

Critical Thinking

- Paperback Book - $29.99

- eBook - $29.99

Fun-Time Phonics!™

Grades: PreK-2

Language Arts

- Paperback Book - $34.99

- eBook - $34.99

Kindergarten Thinking Skills & Key Concepts

- Award Winner

- Paperback Book - $21.99

- eBook - $21.99

Kindergarten Thinking Skills & Key Concepts: Answer PDF

- eBook - $0.00

Building Thinking Skills® Primary Complete Set

- Program / Kit - $87.96 $79.16

- Remove This Item

- Add to Cart Add to Cart Remove This Item

- Special of the Month

- Sign Up for our Best Offers

- Bundles = Greatest Savings!

- Sign Up for Free Puzzles

- Sign Up for Free Activities

- Toddler (Ages 0-3)

- PreK (Ages 3-5)

- Kindergarten (Ages 5-6)

- 1st Grade (Ages 6-7)

- 2nd Grade (Ages 7-8)

- 3rd Grade (Ages 8-9)

- 4th Grade (Ages 9-10)

- 5th Grade (Ages 10-11)

- 6th Grade (Ages 11-12)

- 7th Grade (Ages 12-13)

- 8th Grade (Ages 13-14)

- 9th Grade (Ages 14-15)

- 10th Grade (Ages 15-16)

- 11th Grade (Ages 16-17)

- 12th Grade (Ages 17-18)

- 12th+ Grade (Ages 18+)

- Test Prep Directory

- Test Prep Bundles

- Test Prep Guides

- Preschool Academics

- Store Locator

- Submit Feedback/Request

- Sales Alerts Sign-Up

- Technical Support

- Mission & History

- Articles & Advice

- Testimonials

- Our Guarantee

- New Products

- Free Activities

- Libros en Español

COMMENTS

Third, following an analysis of critical thinking in the primary education subject syllabi, a broad picture of critical thinking skills in the school curriculum emerges. The syllabi describe, explicitly and implicitly, all the core critical thinking skills. ... Second Language Curriculum—Primary Cycle (P1-P5); Office of the Secretary ...

The primary education curriculum of the European Schools [64] mentions critical thinking as a key skill to develop among pupils together with other higher-order skills (e.g., problem-solving, collaboration, communication). However, there is a lack of clarity concerning what exactly is included across the curriculum.

Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care ...

Moreover, the development of critical thinking enriches language learning by expanding it beyond language skills and memorisation ... Introduction: A unit entitled 'Fun with plays' from the language arts module of the primary English language curriculum was selected to embed the teaching of critical thinking in the curriculum context. The ...

Maskot Images / Shutterstock. Critical thinking is using analysis and evaluation to make a judgment. Analysis, evaluation, and judgment are not discrete skills; rather, they emerge from the accumulation of knowledge. The accumulation of knowledge does not mean students sit at desks mindlessly reciting memorized information, like in 19th century ...

Computational thinking (CT) is valued as a thinking process that is required to adapt to the development of curriculum in primary education. In the context of modern information technology, English as a language subject emphasizes the necessity for changes in both learning and teaching modes. However, there is a lack of up-to-date synthesis research and a comprehensive overview surrounding CT ...

Petek E., Bedir H. (2018). An adaptable teacher education framework for critical thinking in language teaching. Thinking ... Volman M. (2019). Teachers' role in stimulating students' inquiry habit of mind in primary schools. Teaching and ... Big ideas: A close look at the Australian history curriculum from a primary teacher's perspective. ...

The scholarly literature reviewed in Chap. 2 shows a variety of conceptualizations of critical thinking, enriched by views from different fields. It also presents practical suggestions for the classroom, found in the relevant bibliography too. Some of these conceptualizations and applications make an explicit connection between the development of critical thinking as a habit of mind (Benderson ...

Infusion of Critical Thinking across the English Language Curriculum: A Multiple Case Study of Primary School In-Service Expert Teachers in Singapore ... {Infusion of Critical Thinking across the English Language Curriculum: A Multiple Case Study of Primary School In-Service Expert Teachers in Singapore}, author={Hui Meng Kow}, year={2016}, url ...

English language curriculum learning and teaching in primary education. To address this research gap, this study conducted a systematic literature review on CT in the primary English curriculum, based on papers published from 2011 to 2021. The purpose of this review is to systematically examine and present empirical evidence

The most important is to allow your child to try things without fear of failure. When children are scared of failure, they are more likely to turn to memorisation, which feels safer, as opposed to analysis. You can also ask, and get your child to ask, the big 6 critical questions: 'who', 'what', 'where', 'when', 'why', and ...

Boosting Critical Thinking Across the Curriculum. Visible thinking routines that encourage students to document and share their ideas can have a profound effect on their learning. In my coaching work with schools, I am often requested to model strategies that help learners think deeply and critically across multiple disciplines and content areas.

John Snell is a Primary School Headteacher and Executive Headteacher of an academy group, as well as an expert speaker and educator. John believes in going beyond the curriculum and preparing the next generation of engaged individuals, working on critical thinking skills and citizenship with his pupils. He is on the education advisory board for ...

Describing, comparing, and contrasting skills are necessary to a child's ability to put things in order, to group items by class, and to think analogically. Building Thinking Skills® Primary requires the use of Attribute Blocks and Interlocking Cubes (required, sold separately). Activities are modeled to reinforce reasoning skills and concepts.

We would like to show you a description here but the site won't allow us.

Primary Language Curriculum Webinar 5 focuses on the Primary Language Curriculum and Critical Literacy. ... The main focus of PLC Webinar 5 will be to explore critical literacy, as one of the key aspects of section 6 of the curriculum (The Curriculum in Practice). This webinar will provide teachers with an opportunity to explore what developing ...

The Primary Language Curriculum (PLC) 2019 supports the positive dispositions towards language and literacy developed at home and in ... Regular use of open-ended questioning stimulates critical thinking and encourages fluency of speech. • Reading aloud Reading aloud high-quality books to children is an extremely valuable

thinking into the foreign language curriculum within general education. Defining Critical Thinking. ... asked if they felt that critical thinking was a primary objective of instruction at their institution, an overwhelming 89 percent said yes. Further, 67 percent