Essay on Hospital

500 words essay on hospital.

Hospitals are institutions that deal with health care activities. They offer treatment to patients with specialized staff and equipment. In other words, hospitals serve humanity and play a vital role in the social welfare of any society. They have all the facilities to deal with varying diseases to make the patient healthy. The essay on hospital will take us through their types and importance.

Types of Hospitals

Generally, there are two types of hospitals, private hospitals and government hospitals. An individual or group of physicians or organization run private hospitals. On the other hand, the government runs the government hospital.

There are also semi-government hospitals that a private and organization and government-run together. Further, there are general hospitals that deal with different kinds of healthcare but with a limited capacity.

General hospitals treat patients from any type of disease belonging to any sex or age. Alternatively, there are specialized hospitals that limit their services to a particular health condition like oncology, maternity and more.

The main aim of hospitals is to offer maximum health services and ensure care and cure. Further, there are other hospitals also which serve as training centres for the upcoming physicians and offer training to professionals.

Many hospitals also conduct research works for people. The essential services which are available in a hospital include emergency and casualty services, OPD services, IPD services, and operation theatre.

Importance of Hospitals

Hospitals are very important for us as they offer extensive treatment to all. Moreover, they are equipped with medical equipment which helps in the diagnosis and treatment of many types of diseases.

Further, one of the most important functions of hospitals is that they offer multiple healthcare professionals. It is filled with a host of doctors, nurses and interns. When a patient goes to a hospital, many doctors do a routine check-up to ensure maximum care.

Similarly, when there are multiple doctors in one place, you can take as many opinions as you want. Further, you will never be left unattended with the availability of such professionals. It also offers everything under one roof.

For instance, in the absence of hospitals, we would have to go to different places to look for specialist doctors in their respective clinics. This would have just increased the hassle and waste energy and time.

But, hospitals narrow down this search to a great level. Hospitals are also a great source of employment for a large section of society. Apart from the hospital staff, there are maintenance crew, equipment handlers and more.

In addition, they also provide cheaper healthcare as they offer treatment options for patients from underprivileged communities. We also use them to raise awareness regarding different prevention and vaccination drives. Finally, they also offer specialized treatment for a particular illness.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Hospital

We have generally associated hospital with illness but the case is the opposite of wellness. In other words, we visit the hospital all sick and leave healthy or better than before. Moreover, hospitals play an essential role in offering consultation services to patients and making the population healthier.

FAQ of Essay on Hospital

Question 1: What is the importance of hospitals?

Answer 1: Hospitals are significant as they treat minor and serious diseases, illnesses and disorders of the body function of varying types and severity. Moreover, they also help in promoting health, giving information on the prevention of illnesses and providing curative services.

Question 2: What are the services of a hospital?

Answer 2: Hospitals provide many services which include short-term hospitalization. Further, it also offers emergency room services and general and speciality surgical services. Moreover, they also offer x-ray and radiology and laboratory services.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

WRITERS HELPING WRITERS®

Helping writers become bestselling authors

Setting Description Entry: Hospital

December 6, 2008 by BECCA PUGLISI

ambulances, doctors, nurses, ambulance attendants, paramedics, volunteers, porters, priests, visitors, firemen, police officers, pink/green/blue or patterned scrubs, gurney, clipboards, IV bags and stands, blood, cuts, bruises, pus, torn tissue, casts, arm slings…

doors sliding open and shut, furnace, air exchanger, screams, cries moans, gasps, grunts/hisses of pain, people talking in low voices, intercom calling out codes/directions, squeaky wheelchairs, the clack of the keyboard, a low-volumed radio or TV, heavy…

cleaners (pine, lemon, bleach etc), antiseptic, a metallic tang from stainless steel in the open air, bleach wafting from bedding, blood, vomit, sweat, perfume/cologne, the scent of get well flowers, questionable food smells from room trays, grease/meaty/soup smells…

Burnt coffee from machines, bland food from vending machines, Hospital food (jello, pudding, soups, oatmeal, bland chicken, mashed potatoes, dry buns or toast), snack foods from vending machines (granola bars, chips, candy bars, pop, juices, energy drinks…

Cold metal bed rails, soft pillows, crisp sheets, smooth plastic emergency remote/call remote, pain (hot, deep, burning, sharp, dull, achy, stabbing, probing), the prick of a needle, cool swipe of antiseptic being applied on skin, a sweaty forehead, sweat dripping…

Helpful hints:

–The words you choose can convey atmosphere and mood.

Example 1 : My gaze swivelled over the waiting room, looking for a place for Andrew and I to sit. A TV played quietly in one corner, a distraction that might help keep his mind off the stitches he would need in his arm. The seats closest to it stood empty, sandwiched between two sweating and shivering men. As one leaned forward and filled the space with harsh, hacking coughs, I understood why no one else had jumped at the prime location. I steered Andrew to the other side of the room, the bland walls and tableful of torn magazines suddenly much more appealing…

–Similes and metaphors create strong imagery when used sparingly.

Example 1: (Metaphor) The orderly sped down the hall with his crash cart, straining to reach the ODed rock star. Doctors swarmed her bed, bees serving their queen, racing to bring her back from the dead…

Think beyond what a character sees, and provide a sensory feast for readers

Setting is much more than just a backdrop, which is why choosing the right one and describing it well is so important. To help with this, we have expanded and integrated this thesaurus into our online library at One Stop For Writers . Each entry has been enhanced to include possible sources of conflict , people commonly found in these locales , and setting-specific notes and tips , and the collection itself has been augmented to include a whopping 230 entries—all of which have been cross-referenced with our other thesauruses for easy searchability. So if you’re interested in seeing a free sample of this powerful Setting Thesaurus, head on over and register at One Stop.

On the other hand, if you prefer your references in book form, we’ve got you covered, too, because both books are now available for purchase in digital and print copies . In addition to the entries, each book contains instructional front matter to help you maximize your settings. With advice on topics like making your setting do double duty and using figurative language to bring them to life, these books offer ample information to help you maximize your settings and write them effectively.

Becca Puglisi is an international speaker, writing coach, and bestselling author of The Emotion Thesaurus and its sequels. Her books are available in five languages, are sourced by US universities, and are used by novelists, screenwriters, editors, and psychologists around the world. She is passionate about learning and sharing her knowledge with others through her Writers Helping Writers blog and via One Stop For Writers —a powerhouse online library created to help writers elevate their storytelling.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Reader Interactions

September 6, 2011 at 12:41 am

Thanks Killian. 🙂

September 5, 2011 at 12:07 pm

You might want to add Benzoin to the smell category. I love the smell of Benzoin in the morning!

April 17, 2011 at 5:07 pm

These are awesome! I wish you had a post on mental or Psychiatric Hospitals, too!

Hmmm, maybe you can post one! 🙂

December 8, 2008 at 7:45 pm

Thanks everyone! I had to rely on my TV show watching and imagination fo rthe most part as I haven’t (thankfully) spent much time in a hospital.

*knocks on wood*

December 8, 2008 at 7:11 pm

Wow. How do you manage to put these things together? So in-depth.

December 7, 2008 at 9:30 am

I’ve spent enough time in hospitals to know…good job.

December 6, 2008 at 8:48 pm

Nice! A place of pain where all our characters should be!

December 6, 2008 at 6:51 pm

Med Gas stations.

I build medical centers as part of what I do. My guys stored their lunches in the unoccupied morgue trays. Rough bunch. Nothing like the mixed smells of ham, cheese & ‘preservatives’ – I guess.

[…] Hospital […]

SLAP HAPPY LARRY

Writing activity: describe medical rooms and hospitals.

Medical rooms and hospitals are safe, infantalising, dangerous, creepy, life-saving, traumatising places, and I offer them here as examples of what Foucault called ‘ heterotopia ‘.

The hospital’s ambiguous relationship to everyday social space has long been a central theme of hospital ethnography. Often, hospitals are presented either as isolated “islands’ defined by biomedical regulation of space (and time) or as continuations and reflections of everyday social space that are very much a part of the “mainland.’ This polarization of the debate overlooks hospitals’ paradoxical capacity to be simultaneously bounded and permeable , both sites of social control and spaces where alternative and transgressive social orders emerge and are contested. We suggest that Foucault’s concept of heterotopia usefully captures the complex relationships between order and disorder, stability and instability that define the hospital as a modernist institution of knowledge, governance, and improvement . Heterotopia Studies

Hospitals (like airports) elicit the full range of human emotion and are symbolically useful arenas for storytellers. Who better than writers to describe what it feels like to be inside a hospital?

I followed [the psychiatrist] down a depressing hallway into a tiny windowless office that might have housed an accountant. In fact it reminded me a bit of Myron Axel’s closet, filled with piles of paper waiting to be filed, week-old cups of coffee turned into science experiments, and a litter of broken umbrellas nesting beneath the desk. I must have looked as surprised as I felt when I entered her office, for Rowena Adler looked at the utilitarian clutter about her and said, “I’m sorry about this mess. I’m so used to it. I forget how it looks.” Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You by Peter Cameron

The author may have enjoyed writing that description because at James Sveck’s next appointment they are in a different room.

Dr Adler’s downtown office was a pleasanter place than her space at the Medical Center, but it wasn’t the sun-filled haven I had imagined. It was a rather small dark office in a suite of what I assumed were several small dark offices on the ground floor of an old apartment building on Tenth Street. In addition to her desk and chair there was a divan, another chair, a ficus tree, and some folkloric-looking weavings on the wall. And a bookcase of dreary books. I could tell they were all nonfiction because they all had titles divided by colons: Blah Blah Blah: The Blah Blah Blah of Blah Blah Blah . There was one window that probably faced an airshaft because the rattan shade was lowered in a way that suggested it was never raised. The walls were painted a pale yellow, in an obvious (but unsuccessful) attempt to “brighten up” the room.

The description of James’ psychiatrist’s rooms is broken up, judiciously, and fits around the action. James’ reaction to the rooms reflects how he feels about life at this juncture: He expected better. He expected different; instead he gets this underwhelming life.

I looked around her office. I know it sounds terrible, but I was discouraged by the ordinariness, the expectedness, of it. It was as if there was a catalog for therapists to order a complete office from: furniture, carpet, wall hangings, even the ficus tree seemed depressingly generic. Like one of those little paper pellets you put in water that puffs up and turns into a lotus blossom. This was like a puffed-up shrink’s office.

In a book of essays, Tim Kreider’s description of hospitals is one of the best I’ve encountered:

Hospitals are like the landscapes in recurring dreams: forgotten as though they’d never existed in the interims between visits, but instantly familiar once you return. As if they’ve been there all along, waiting for you while you’ve been away. The endlessly branching corridors sand circular nurses’ stations all look identical, like some infinite labyrinth in a Borges story. It takes a day or two to memorize the route from the lobby to your room. The innocuous landscape paintings that seem to have been specifically commissioned to leave no impression on the human brain are perversely seared into your long-term memory. You pass doorways through which you can occasionally see a bunch of Mylar balloons or a pair of pale, withered legs. Hospital beds are now just as science fiction predicted, with the patient’s vital signs digitally displayed overhead. Nurses no longer wear the white hose and red-cross caps of cartoons and pornography, but scrubs printed with patterns so relentlessly cheerful—hearts, teddy bears, suns and flowers and peace signs—they seem symptomatic of some Pollyannaish denial. The smell of hospitals is like small talk at a funeral—you know its function is to cover up something else. There’s a grim camaraderie in the hall and elevators. You don’t have to ask anybody how they’re doing. The fact that they’re there at all means the answer is: Could be better. I notice that no one who works in a hospital, whose responsibilities are matters of life and death, ever seems hurried or frantic, in contrast to all the freelance cartoonists and podcasters I know. Time moves differently in hospitals—both slower and faster. The minutes stand still, but the hours evaporate. The day is long and structureless, measured only by the taking of vital signs, the changing of IV bags, medication schedules, occasional tests, mealtimes, trips to the bathroom, walks in the corridor. Once a day an actual doctor appears for about four minutes, and what she says during this time can either leave you and your family in terrified confusion or so reassured and grateful that you want to write her a thank-you note she’ll have framed. You cadge six-ounce cans of ginger ale from the nurses’ station. You no longer need to look at the menu in the diner across the street. You substitute meat loaf for bacon with your eggs. Why not? Breakfast and lunch are diurnal conventions that no longer apply to you. Sometimes you run errands back home for a cell phone or extra clothes. Eventually you look at your watch and realize visiting hours are almost over, and feel relieved, and then guilty. Tim Kreider, “An Insult To The Brain”, We Learn Nothing

It’s a fact known throughout the universes that no matter how carefully the colours are chosen, institutional décor ends up either vomit green, unmentionable brown, nicotene yellow or surgical appliance pink. Terry Pratchett, Equal Rites

They are now the only two people in the upstairs waiting room of the dental clinic. The seats are a pale mint-green colour. Marianne leafs through an issue of NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and explores her mouth with the tip of her tongue. Connell looks at the magazine cover, a photograph of a monkey with huge eyes. from “At The Clinic” by Sally Rooney

Every time I see a hospital in a horror movie or whatever, sometimes even an actual prison, I compare it to the one I went to and it always comes out looking worse. They are not relaxing places. They can leave you worse than you came in. Especially because the world outside, doesn’t actually stop while you are there? You’re usually there due to a crisis. Something unexpected. Did you take vacation pay before you started? Probably not, hey? Provided that you get that sort of thing at all. If you’re on welfare, you’re still have to fight for an exemption. Good luck if you can’t do that because you’re literally insane. You’ll still need to pay the rent and all your bills somehow in the background too. Oh, you got kicked out? That’s a shame. Here’s a pamphlet to a homeless shelter. Have a lovely trip. My stay did turn out a lot better than that, but it’s literally only because I had someone constantly advocating for me on the outside. Most people in psych wards don’t get that. And that’s not even touching on how nobody will listen to you in there, but everybody will assume all sorts of things about you. You’ll be open to both sexual and physical assault. Both happened to me on a number of occasions. I was blamed for everything, of course. You don’t even get uninterrupted sleep, do you know that? Nurses come and shine a torch in your face every fucking hour for a wellness check, or whatever. Which feels pretty shitty if you’re going through a paranoid psychosis. Anyway. I’d really like to see more empathy and awareness of the reality of all these sorts of places. They are horrible. They haven’t changed a lot since they were called asylums. They still use solitary confinement too, did you know that? Awful things. Mx Maddison Stoff @TheDescenters Sep 8, 2022

FURTHER READING

What’s It Like To Work In A Psych Hospital? is a podcast from Psych Central with someone who explains how psychiatric hospitals are traumatising for everyone in and around them, not just for the patients.

The Architecture of Madness

Elaborately conceived, grandly constructed insane asylums—ranging in appearance from classical temples to Gothic castles—were once a common sight looming on the outskirts of American towns and cities. Many of these buildings were razed long ago, and those that remain stand as grim reminders of an often cruel system. For much of the nineteenth century, however, these asylums epitomized the widely held belief among doctors and social reformers that insanity was a curable disease and that environment—architecture in particular—was the most effective means of treatment. In The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States (U Minnesota Press, 2007), Carla Yanni tells a compelling story of therapeutic design, from America’s earliest purpose—built institutions for the insane to the asylum construction frenzy in the second half of the century. At the center of Yanni’s inquiry is Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, a Pennsylvania-born Quaker, who in the 1840s devised a novel way to house the mentally diseased that emphasized segregation by severity of illness, ease of treatment and surveillance, and ventilation. After the Civil War, American architects designed Kirkbride-plan hospitals across the country. Before the end of the century, interest in the Kirkbride plan had begun to decline. Many of the asylums had deteriorated into human warehouses, strengthening arguments against the monolithic structures advocated by Kirkbride. At the same time, the medical profession began embracing a more neurological approach to mental disease that considered architecture as largely irrelevant to its treatment. Generously illustrated, The Architecture of Madness is a fresh and original look at the American medical establishment’s century-long preoccupation with therapeutic architecture as a way to cure social ills. interview at New Books Network

The Architecture of Good Behavior: Psychology and Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America

Inspired by the rise of environmental psychology and increasing support for behavioral research after the Second World War, new initiatives at the federal, state, and local levels looked to influence the human psyche through form, or elicit desired behaviors with environmental incentives, implementing what Joy Knoblauch calls “psychological functionalism.” Recruited by federal construction and research programs for institutional reform and expansion—which included hospitals, mental health centers, prisons, and public housing—architects theorized new ways to control behavior and make it more functional by exercising soft power, or power through persuasion, with their designs. In the 1960s –1970s era of anti-institutional sentiment, they hoped to offer an enlightened, palatable, more humane solution to larger social problems related to health, mental health, justice, and security of the population by applying psychological expertise to institutional design. In turn, Knoblauch argues, architects gained new roles as researchers, organizers, and writers while theories of confinement, territory, and surveillance proliferated. The Architecture of Good Behavior: Psychology and Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America (University of Pittsburgh Press) explores psychological functionalism as a political tool and the architectural projects funded by a postwar nation in its efforts to govern, exert control over, and ultimately pacify its patients, prisoners, and residents. interview at New Books Network

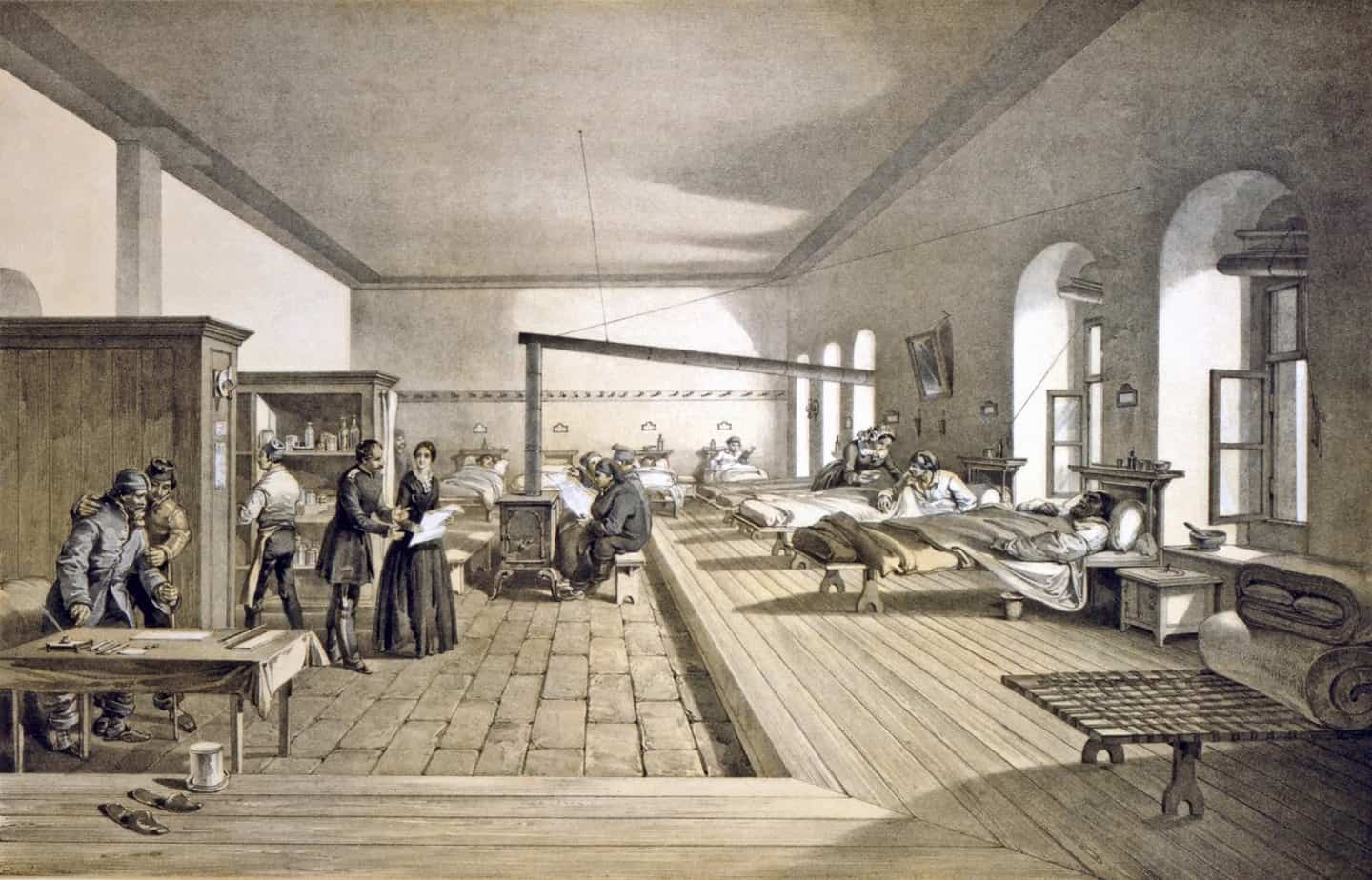

Header painting: William Simpson – One of the wards of the hospital at Scutari 1856

CONTEMPORARY FICTION SET IN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND (2023)

On paper, things look fine. Sam Dennon recently inherited significant wealth from his uncle. As a respected architect, Sam spends his days thinking about the family needs and rich lives of his clients. But privately? Even his enduring love of amateur astronomy is on the wane. Sam has built a sustainable-architecture display home for himself but hasn’t yet moved into it, preferring to sleep in his cocoon of a campervan. Although they never announced it publicly, Sam’s wife and business partner ended their marriage years ago due to lack of intimacy, leaving Sam with the sense he is irreparably broken.

Now his beloved uncle has died. An intensifying fear manifests as health anxiety, with night terrors from a half-remembered early childhood event. To assuage the loneliness, Sam embarks on a Personal Happiness Project:

1. Get a pet dog

2. Find a friend. Just one. Not too intense.

KINDLE EBOOK

Short Essay on Hospital in English

Hospital is a kind of institution which deals with health care activities. It is an institution that provides treatment to patients with specialized staff and equipment. It serves humanity as a whole. It is an integral part of the social welfare of a society or a state.

Patients with various health problems are being treated in hospitals. Hospitals have all the facilities to deal with any kind of disease starting from physical health issues to mental and psychological deficiencies.

The types of hospitals in general are private hospitals and hospitals run by the government. Private hospitals basically are run by an individual or a group of physicians or by any private organization. Another kind of hospital prevails in India and it is the semi-government hospital that is run by both the government and the private organization.

The general hospitals provide different kinds of healthcare, but with limited capacity. Patients suffering from any kind of diseases or patients of any sexes, of any age are been treated in general hospitals. On the other hand, specialized hospitals limit their services to a specific health condition such as orthopedics, oncology, maternity, etc.

Hospitals aim to provide maximum health services. They ensure care, cure, and preventive services. Some hospitals also serve as training centers for the upcoming physicians and provide training to the professionals.

Research works also are conducted in hospitals. The functions of the hospital involve in-patient services, patients care, medical and nursing research, promoting awareness for some unavoidable diseases.

The essential services available in a hospital are emergency and casualty services, IPD services, OPD services, and Operation Theatre. However, it is a place where people visit with belief and trust to get recovered from any kind of disease.

Table of Contents

Question on Hospital

What is hospital care.

Hospitals aim to provide maximum health services. They ensure care, cure, and preventive services.

What is the main function of a hospital?

The functions of the hospital involve in-patient services, patients care, medical and nursing research, promoting awareness for some unavoidable diseases.

Related Posts:

- Goblin Market Poem by Christina Rossetti Summary, Notes and Line by Line Explanation in English

- Stri Purush Tulana by Tarabai Shinde Analysis

- Random Phrase Generator [English]

- Civil Disobedience Summary by Thoreau

- Random Address Generator [United States]

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Descriptive Essay? How to Write It (with Examples)

A descriptive essay is a type of creative writing that uses specific language to depict a person, object, experience, or event. The idea is to use illustrative language to show readers what the writer wants to convey – it could be as simple as a peaceful view from the top of a hill or as horrific as living in a war zone. By using descriptive language, authors can evoke a mental image in the readers’ minds, engaging readers and leaving a lasting impression, instead of just providing a play-by-play narrative.

Note that a description and descriptive essay are not the same thing. A descriptive essay typically consists of five or more well-written paragraphs with vivid imagery that can help readers visualize the content, as opposed to a description, which is typically one or more plain paragraphs with no particular structure or appeal. If you are still unsure about how to write a compelling descriptive essay, continue reading!

Table of Contents

What is a descriptive essay, types of descriptive essay topics.

- Characteristics of descriptive essays

How to write a descriptive essay using a structured outline

Frequently asked questions.

A simple descriptive essay definition is that it is a piece of writing that gives a thorough and vivid description of an object, person, experience, or situation. It is sometimes focused more on the emotional aspect of the topic rather than the specifics. The author’s intention when writing a descriptive essay is to help readers visualize the subject at hand. Generally, students are asked to write a descriptive essay to test their ability to recreate a rich experience with artistic flair. Here are a few key points to consider when you begin writing these.

- Look for a fascinating subject

You might be assigned a topic for your descriptive essay, but if not, you must think of a subject that interests you and about which you know enough facts. It might be about an emotion, place, event, or situation that you might have experienced.

- Acquire specific details about the topic

The next task is to collect relevant information about the topic of your choice. You should focus on including details that make the descriptive essay stand out and have a long-lasting impression on the readers. To put it simply, your aim is to make the reader feel as though they were a part of the experience in the first place, rather than merely describing the subject.

- Be playful with your writing

To make the descriptive essay memorable, use figurative writing and imagery to lay emphasis on the specific aspect of the topic. The goal is to make sure that the reader experiences the content visually, so it must be captivating and colorful. Generally speaking, “don’t tell, show”! This can be accomplished by choosing phrases that evoke strong emotions and engage a variety of senses. Making use of metaphors and similes will enable you to compare different things. We will learn about them in the upcoming sections.

- Capture all the different senses

Unlike other academic articles, descriptive essay writing uses sensory elements in addition to the main idea. In this type of essay writing, the topic is described by using sensory details such as smell, taste, feel, and touch. Example “ Mahira feels most at home when the lavender scent fills her senses as she lays on her bed after a long, tiring day at work . As the candle melts , so do her worries” . It is crucial to provide sensory details to make the character more nuanced and build intrigue to keep the reader hooked. Metaphors can also be employed to explain abstract concepts; for instance, “ A small act of kindness creates ripples that transcend oceans .” Here the writer used a metaphor to convey the emotion that even the smallest act of kindness can have a larger impact.

- Maintain harmony between flavor and flow

The descriptive essay format is one that can be customized according to the topic. However, like other types of essays, it must have an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The number of body paragraphs can vary depending on the topic and available information.

It is crucial to remember that a descriptive essay should have a specific topic and goal, such as sharing personal experiences or expressing emotions like the satisfaction of a good meal. This is accomplished by employing exact language, imagery, and figurative language to illustrate concrete features. These language devices allow the writer to craft a descriptive essay that effectively transmits a particular mood, feeling, or incident to readers while also conjuring up strong mental imagery. A descriptive essay may be creative, or it may be based on the author’s own experiences. Below is a description of a few descriptive essay examples that fit into these categories.

- Personal descriptive essay example

A personal essay can look like a descriptive account of your favorite activity, a place in your neighborhood, or an object that you value. Example: “ As I step out of the front door, the crisp morning air greets me with a gentle embrace; the big chestnut tree in front, sways in the wind as if saying hello to me. The world unfolds in a symphony of awakening colors, promising a day filled with untold possibilities that make me feel alive and grateful to be born again”.

- Imaginative descriptive essay example

You may occasionally be required to write descriptive essays based on your imagination or on subjects unrelated to your own experiences. The prompts for these kinds of creative essays could be to describe the experience of someone going through heartbreak or to write about a day in the life of a barista. Imaginative descriptive essays also allow you to describe different emotions. Example, the feelings a parent experiences on holding their child for the first time.

Characteristics of descriptive essay s

The aim of a descriptive essay is to provide a detailed and vivid description of a person, place, object, event, or experience. The main goal is to create a sensory experience for the reader. Through a descriptive essay, the reader may be able to experience foods, locations, activities, or feelings that they might not otherwise be able to. Additionally, it gives the writer a way to relate to the readers by sharing a personal story. The following is a list of the essential elements of a descriptive essay:

- Sensory details

- Clear, succinct language

- Organized structure

- Thesis statement

- Appeal to emotion

How to write a descriptive essay, with examples

Writing an engaging descriptive essay is all about bringing the subject matter to life for the reader so they can experience it with their senses—smells, tastes, and textures. The upside of writing a descriptive essay is you don’t have to stick to the confinements of formal essay writing, rather you are free to use a figurative language, with sensory details, and clever word choices that can breathe life to your descriptive essay. Let’s take a closer look at how you can use these components to develop a descriptive essay that will stand out, using examples.

- Figurative language

Have you ever heard the expression “shooting for the stars”? It refers to pushing someone to strive higher or establish lofty goals, but it does not actually mean shooting for the stars. This is an example of using figurative language for conveying strong motivational emotions. In a descriptive essay, figurative language is employed to grab attention and emphasize points by creatively drawing comparisons and exaggerations. But why should descriptive essays use metaphorical language? One it adds to the topic’s interest and humor; two, it facilitates the reader’s increased connection to the subject.

These are the five most often used figurative language techniques: personification, metaphor, simile, hyperbole, and allusion.

- Simile: A simile is a figure of speech that is used to compare two things while emphasizing and enhancing the description using terms such as “like or as.”

Example: Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving – Albert Einstein

- Metaphor: A metaphor are also used to draw similarities, but without using direct or literal comparisons like done in similes.

Example: Books are the mirrors of the soul – Virginia Woolf, Between the acts

- Personification: This is the process of giving nonhuman or abstract objects human traits. Any human quality, including an emotional component, a physical attribute, or an action, can be personified.

Example: Science knows no country, because knowledge belongs to humanity, and is the torch which illuminates the world – Louis Pasteur

- Hyperbole: This is an extreme form of exaggeration, frequently impractical, and usually employed to emphasize a point or idea. It gives the character more nuance and complexity.

Example: The force will be with you, always – Star Wars

- Allusion: This is when you reference a person, work, or event without specifically mentioning them; this leaves room for the reader’s creativity.

Example: In the text below, Robert Frost uses the biblical Garden of Eden as an example to highlight the idea that nothing, not even paradise, endures forever.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay

– Nothing Gold Can Stay by Robert Frost (1923)

Descriptive essays need a combination of figurative language and strong sensory details to make the essay more memorable. This is when authors describe the subject matter employing senses like smell, sound, touch, and taste so that the reader can relate to it better.

Example of a sensory-based descriptive essay: The earthy fragrance of freshly roasted chestnuts and the sight of bright pink, red, orange fallen leaves on the street reminded her that winter was around the corner.

- Word choice

Word choice is everything in a descriptive essay. For the description to be enchanting, it is essential to utilize the right adjectives and to carefully consider the verbs, nouns, and adverbs. Use unusual terms and phrases that offer a new viewpoint on your topic matter instead of overusing clichés like “fast as the wind” or “lost track of time,” which can make your descriptive essay seem uninteresting and unoriginal.

See the following examples:

Bad word choice: I was so happy because the sunset was really cool.

Good word choice: I experienced immense joy as the sunset captivated me with its remarkable colors and breathtaking beauty.

- Descriptive essay format and outline

Descriptive essay writing does not have to be disorganized, it is advisable to use a structured format to organize your thoughts and ensure coherent flow in your writing. Here is a list of components that should be a part of your descriptive essay outline:

- Introduction

- Opening/hook sentence

- Topic sentence

- Body paragraphs

- Concrete details

- Clincher statement

Introduction:

- Hook: An opening statement that captures attention while introducing the subject.

- Background: Includes a brief overview of the topic the descriptive essay is based on.

- Thesis statement: Clearly states the main point or purpose of the descriptive essay.

Body paragraphs: Each paragraph should have

- Topic sentence: Introduce the first aspect or feature you will describe. It informs the reader about what is coming next.

- Sensory details: Use emphatic language to appeal to the reader’s senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell).

- Concrete details: These are actual details needed to understand the context of the descriptive essay.

- Supporting details: Include relevant information or examples to improve the description.

Conclusion:

- Summarize key points: Here you revisit the main features or aspects of the subject.

- Restate thesis statement: Reinforce the central impression or emotion.

- Clincher statement: Conclude with a statement that summarizes the entire essay and serve as the last words with a powerful message.

Revision and editing:

- Go over your essay to make sure it is coherent, clear, and consistent.

- Check for logical paragraph transitions by proofreading the content.

- Examine text to ensure correct grammar, punctuation, and style.

- Use the thesaurus or AI paraphrasing tools to find the right words.

A descriptive essay often consists of three body paragraphs or more, an introduction that concludes with a thesis statement, and a conclusion that summarizes the subject and leaves a lasting impression on readers.

A descriptive essay’s primary goal is to captivate the reader by writing a thorough and vivid explanation of the subject matter, while appealing to their various senses. A list of additional goals is as follows: – Spark feeling and imagination – Create a vivid experience – Paint a mental picture – Pique curiosity – Convey a mood or atmosphere – Highlight specific details

Although they both fall within the creative writing category, narrative essays and descriptive essays have different storytelling focuses. While the main goal of a narrative essay is to tell a story based on a real-life experience or a made-up event, the main goal of a descriptive essay is to vividly describe a person, location, event, or emotion.

Paperpal is an AI academic writing assistant that helps authors write better and faster with real-time writing suggestions and in-depth checks for language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of published scholarly articles and 20+ years of STM experience, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to Paperpal Copilot and premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks, submission readiness and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- 7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

- Webinar: How to Use Generative AI Tools Ethically in Your Academic Writing

- Addressing Your Queries on AI Ethics, Plagiarism, and AI Detection

4 Types of Transition Words for Research Papers

What is a narrative essay how to write it (with examples), you may also like, how to write a high-quality conference paper, how paperpal is enhancing academic productivity and accelerating..., academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples , what is academic writing: tips for students, what is hedging in academic writing , how to use ai to enhance your college..., how to use paperpal to generate emails &....

How to Write Hospital Scenes (21 Best Tips + Examples)

Hospitals are places where life’s most poignant moments unfold, from the joy of birth to the sorrow of passing away.

As such, hospital scenes show up in a lot of stories.

Here is how to write hospital scenes:

Write hospital scenes by understanding the medical hierarchy, capturing authentic ambiance, using medical jargon sparingly, and emphasizing emotional dynamics. Consider the patient’s journey, relationships, and triumphs. Every element should enhance the realism and emotional depth of the scene.

In this guide, you’ll learn everything you need to know about how to write hospital scenes.

1. Understand the Hospital Hierarchy

Table of Contents

Understanding the hospital hierarchy is crucial.

Hospitals aren’t just about doctors and nurses. They’re made up of an intricate web of professionals working cohesively.

Knowing the roles of various healthcare professionals adds depth to your scene.

Whether it’s an interaction between a resident and an attending physician, or between a nurse and a technician, understanding these dynamics can create tension or camaraderie in your writing.

As Dr. Smith entered the room, she nodded at the nurse. “How’s our patient today, Jane?” Jane, an experienced ICU nurse, responded, “Stable, but his oxygen levels dipped overnight. The respiratory therapist worked on it, and they’re improving now.”

2. Capture the Hospital Ambiance

The atmosphere in a hospital is unique.

The constant beep of monitors, the murmurs of visitors, and the distant announcements over the intercom form a backdrop to your scene.

A vivid atmosphere sets the mood.

Is it a quiet night or a bustling day? The ambiance can reflect the emotional tone of the scene.

The dimly lit hallway echoed with soft footsteps, punctuated by the occasional beep from a room further down. Somewhere, a baby cried, and a nurse’s voice softly tried to soothe.

3. Use Medical Jargon Judiciously

While it’s tempting to throw in medical terms to sound authentic, overusing them or using them incorrectly can confuse readers.

Medical jargon, when used correctly, lends authenticity.

But it’s crucial to ensure the reader can understand the context.

“We’ve started him on a course of IV antibiotics. His white blood cell count was high, indicating an infection.”

4. Show the Emotional Toll

Hospitals are places of healing, but they’re also where people face mortality, pain, and fear.

Capturing the emotional landscape provides depth to your characters and connects readers to the story.

Remember, not everyone in a hospital is a patient; families, visitors, and even healthcare professionals have their emotional journeys.

Nurse Daniels looked out the window for a moment, taking a deep breath to compose herself after the last patient’s passing. The weight of the day heavy on her shoulders.

5. Research Common Procedures

Researching common medical procedures can help you craft realistic scenarios.

Readers, especially those with some medical background, appreciate accuracy.

Getting the details right can boost your story’s credibility.

Sarah watched as the nurse prepared the IV line, ensuring all air bubbles were out before inserting it into her arm.

6. Distinguish between Different Wards

Not all hospital areas are the same.

An ICU differs from a maternity ward or a general patient room.

Distinguishing between different wards can help set the scene, tone, and pace. For instance, an emergency room scene will have a different urgency than a scene in a recovery ward.

The ER was a flurry of activity, with paramedics rushing in and doctors shouting orders. Two floors up, in the recovery ward, it was a different world. Here, the pace was slower, with patients resting and nurses moving quietly between rooms.

7. Remember the Role of Technology

Modern hospitals are technologically advanced.

From MRI machines to portable ECGs, technology is everywhere.

Incorporating technology not only adds realism but also can create tension or relief, depending on the situation.

The room was tense as everyone stared at the ultrasound monitor. A moment later, the unmistakable sound of a heartbeat filled the small space, bringing tears of relief to Maria’s eyes.

8. Understand the Patient Experience

Every individual’s journey through a hospital varies based on the reason for their visit, their past experiences, and their personal anxieties.

The emotional and physical state of a patient is central to their perspective.

They may be overwhelmed, scared, hopeful, or even indifferent.

A writer should consider these emotions when crafting their characters’ responses to treatments, their interactions with medical staff, and even their internal monologue.

Lying in the sterile room, Mark felt exposed. The cold sheets beneath him, the foreign sounds — everything made him uneasy.

9. Highlight Interpersonal Dynamics

Relationships and interactions are the lifeblood of any setting, and hospitals are no exception.

The professional and personal dynamics between staff members can add layers of complexity to a scene.

Perhaps two doctors have conflicting treatment philosophies, or a nurse and a patient share a poignant moment.

These relationships can be sources of both conflict and collaboration, driving the narrative forward and allowing for multifaceted character exploration.

Dr. Patel and Nurse Ramirez had a renowned partnership. Where one was, the other wasn’t far behind, their synchronized movements a testament to years of collaboration.

10. Address Ethical Dilemmas

The hospital setting is fertile ground for moral quandaries, given the life and death decisions made daily.

Ethical dilemmas force characters to confront their values and priorities.

This can range from debates about end-of-life care to the potential ramifications of experimental treatments.

Exploring these tough decisions can provide depth to your narrative and give characters opportunities to evolve and grow.

Faced with the choice of continuing treatment or opting for palliative care, Jenna’s family was divided, each member grappling with their convictions.

11. Don’t Forget the Waiting Rooms

While patient rooms are pivotal, waiting areas serve as intersections of myriad emotions and interactions.

Waiting rooms often encapsulate the anticipation, anxiety, and hope of families and friends.

They can serve as places of bonding between strangers, reflections on the past, or moments of unexpected news.

By delving into the microcosm of the waiting room, writers can unveil diverse human experiences and emotions.

As Sarah waited, she struck up a conversation with an older man, their shared worries forging an unexpected bond.

12. Include Flashbacks or Memories

Hospital environments, laden with emotions, can act as catalysts for characters to relive past experiences.

These flashbacks can be directly related to the current medical situation or completely tangential, offering insights into a character’s past traumas, joys, or significant life events.

Leveraging these memories can create juxtapositions with the present and highlight character growth or unresolved issues.

As the anesthesiologist spoke, Clara’s mind drifted back to her childhood accident — the reason for her phobia of hospitals.

13. Use Senses Beyond Sight

A multisensory approach makes a scene more immersive and vivid for the reader.

Hospitals are a cacophony of sounds, smells, and textures.

From the sterile scent of disinfectant to the soft hum of machines or the rough texture of a bandage, engaging multiple senses offers a comprehensive and engrossing portrayal of the environment, drawing readers into the scene.

The antiseptic smell was overpowering, the occasional distant cough and soft hum of machinery serving as a constant reminder of where she was.

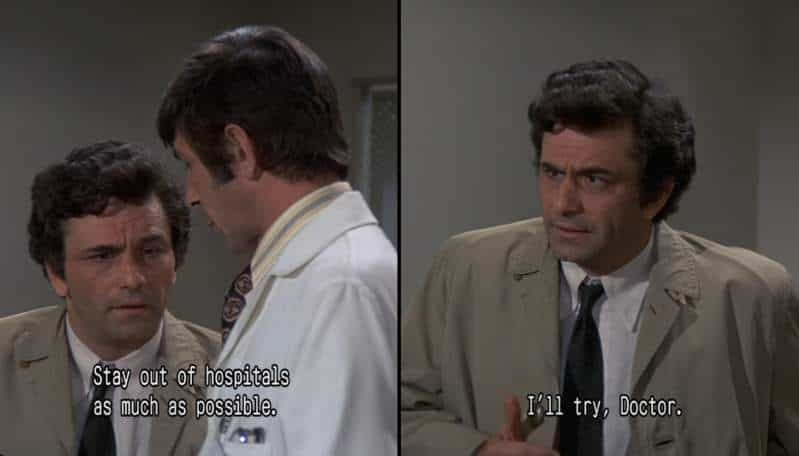

14. Introduce Unexpected Humor

In the face of adversity, humor can act as a relief valve, revealing character resilience.

Moments of levity in tense or somber situations can humanize characters.

It can show their coping mechanisms or their attempts to uplift others.

This contrast can make the gravity of a situation even more poignant while offering readers moments of reprieve.

“You’d think after all these years, they’d find a gown that actually closes in the back,” mused John, earning a chuckle from the nurse.

15. Respect Cultural and Religious Sensitivities

Acknowledging the diverse tapestry of patient backgrounds enhances realism and inclusivity.

Medical decisions, comfort levels with treatments, and interactions with hospital staff can all be influenced by cultural or religious beliefs.

It’s important for writers to enrich their narrative with representation and respect for diverse perspectives.

Mrs. Khan hesitated, her cultural beliefs about modesty making her wary of the male doctor. Recognizing this, Nurse Garcia gently stepped in to mediate.

16. Show Fatigue and Stress among Healthcare Workers

Behind the clinical professionalism, healthcare workers grapple with the emotional and physical demands of their roles.

These professionals often bear witness to intense human experiences, from birth to death and everything in between.

Chronicling their exhaustion, moments of doubt, or instances of resilience can offer a balanced view of the hospital ecosystem.

Not only that but it can also emphasize the human element behind the medical expertise.

After a 16-hour shift, Dr. Lee’s steps were heavy. She paused for a moment, rubbing her temples, before moving on to the next patient.

17. Address the Financial Aspects

The economics of healthcare can be a significant concern for patients and families.

Financial worries can compound the stress of a medical situation.

Addressing these concerns — be it through the lens of insurance battles, out-of-pocket costs, or the broader healthcare debate — can root your story in real-world challenges, making it more relatable and timely.

The relief that her mother was recovering was overshadowed by the mounting medical bills that Amy now faced, a dilemma she hadn’t anticipated.

18. Highlight Moments of Triumph

Despite the challenges, hospitals are also spaces of recovery, healing, and miracles.

Emphasizing moments of success or relief, whether they’re medical breakthroughs or personal victories like a patient taking their first step post-surgery, can infuse your narrative with hope and inspiration.

These moments underscore the resilience of the human spirit and the dedication of medical professionals.

Against all odds, Mr. Rodriguez took his first steps after the accident, the entire ward cheering him on.

19. Include External Influences

The world outside doesn’t stop when one enters a hospital. External events can influence the internal dynamics of the setting.

By weaving in external influences, you can showcase the adaptability of the hospital environment and its staff.

Whether it’s a natural disaster leading to an influx of patients or a city-wide event affecting hospital operations, these external elements can add layers of complexity to your narrative.

As the city marathon was underway, the ER braced for a busy day, anticipating the influx of dehydration cases and potential injuries.

20. Detail Personal Keepsakes

Personal items offer glimpses into a patient’s world outside the hospital, grounding them in reality.

These keepsakes can act as symbols of hope, reminders of loved ones, or touchstones of normalcy in an otherwise clinical environment.

Detail these items and their significance to build deeper emotional connections between characters and readers.

Next to Mrs. Everett’s bed stood a framed photo of a young couple on their wedding day, a testament to a love that had weathered many storms.

21. Remember the Power of Touch

In an environment often dominated by machines and medical instruments, human touch stands out.

Touch, whether comforting or clinical, can convey a multitude of emotions.

A reassuring hand on a shoulder, a clinical examination, or a desperate grasp during a moment of fear can be powerful narrative tools, emphasizing human connection and vulnerability.

As the news settled in, James reached out, gently squeezing his sister’s hand. In that simple gesture, he conveyed the strength and support she desperately needed.

Check out this video about how NOT to write hospital scenes (Unless you’re going for pure comedy):

30 Words to Describe Hospital Scenes

The words you choose for your hospital scenes will alter the mood, tone, and entire reader experience.

Here are 30 words you can use to write hospital scenes:

- Fluorescent

- Reverberating

- Crisp (as in uniforms)

- Intermittent

- Cold (as in touch)

- Harsh (as in lights)

- Labored (as in breathing)

30 Phrases to Write Hospital Scenes

Try these phrases when writing your hospital scenes.

Not all of the phrases will work for your story (or any story) but, hopefully, they will help you craft your own sentences.

- “A symphony of monitors beeped in rhythm.”

- “Whispers filled the corridor, punctuated by distant footsteps.”

- “The scent of disinfectant was almost overpowering.”

- “Nurses moved with practiced efficiency.”

- “The weight of anticipation hung in the air.”

- “A curtain rustled softly in the next bed.”

- “Lights overhead cast stark shadows on the floor.”

- “Intercom announcements broke the tense silence.”

- “Machines whirred and clicked in the background.”

- “Soft murmurs of comfort echoed.”

- “Trolleys clattered past at regular intervals.”

- “Gauzy curtains diffused the morning light.”

- “A stifled sob broke the sterile calm.”

- “The rhythmic pulse of the heart monitor filled the void.”

- “The chill of the tiles was evident even through socks.”

- “Hushed conversations ceased at the doctor’s arrival.”

- “Labored breathing was the room’s only soundtrack.”

- “A clipboard clattered to the ground, shattering the quiet.”

- “The distant hum of an MRI machine grew louder.”

- “The atmosphere was thick with a mix of hope and despair.”

- “Patients lay in rows, separated by thin partitions.”

- “The waiting area was a mosaic of emotions.”

- “Doctors consulted charts with furrowed brows.”

- “IV drips punctuated the silence with their steady rhythm.”

- “A sudden rush of activity signaled an emergency.”

- “Whirring fans attempted to combat the stifling heat.”

- “Shadows played on the wall as the day waned.”

- “The fluorescent lights buzzed overhead, unceasing.”

- “A lone wheelchair sat abandoned in the hall.”

- “Gentle reassurances were whispered bedside.”

3 Full Examples of Writing Hospital Scenes

Here are three complete examples of how to write hospital scenes in different genres.

The hallway of St. Mercy’s was dimly lit, echoing with the soft murmurs of the night shift nurses.

Elizabeth walked slowly, her heels clicking on the tiles, each step feeling like an eternity as she approached room 309. The scent of antiseptics was faint but ever-present, reminding her of the weight of the place. As she pushed open the door, the rhythmic beeping of the heart monitor greeted her, and in the dim light, she saw her father, pale but stable.

Tears welled up, not out of sorrow, but of gratitude.

2. Mystery/Thriller

Detective Rowe entered the ICU, the atmosphere thick with tension.

The overhead lights cast a harsh glow on the room where the city’s mayor lay unconscious. A nurse, her uniform crisp and white, glanced up, her eyes betraying a mix of curiosity and wariness. Rowe noted the machines surrounding the bed — their mechanical hums and beeps creating a symphony of medical surveillance.

He needed answers, and everything about this sterile room was a potential clue.

3. Sci-fi/Fantasy

In the celestial infirmary of Aeloria, walls shimmered with iridescent lights, and the air pulsed with ancient magic.

Elara, the moon sorceress, lay on a floating bed, her aura flickering like a candle nearing its end.

Surrounding her were crystal devices, pulsating and humming in an ethereal dance. Lyric, her apprentice, whispered an incantation, her voice intertwining with the mystical ambiance, hoping to revive her mentor with a blend of ancient spells and cosmic medicine.

Final Thoughts: How to Write Hospital Scenes

Crafting a compelling hospital scene is an intricate dance of authenticity, emotion, and meticulous detail.

For more insights on writing stories, please check out the other articles on my website.

Related Posts:

- How to Write Flashback Scenes (21 Best Tips + Examples)

- How to Foreshadow Death in Writing (21 Clever Ways)

- How to Write Fast-Paced Scenes: 21 Tips to Keep Readers Glued

- How to Describe Crying in Writing (21 Best Tips + Examples)

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Strong Descriptive Essay

Last Updated: May 14, 2024 Fact Checked

Brainstorming Ideas for the Essay

Writing the essay, polishing the essay, outline for a descriptive essay, expert q&a.

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 1,520,225 times.

A good descriptive essay creates a vivid picture of the topic in the reader’s mind. You may need to write a descriptive essay as a class assignment or you may decide to write one as a fun writing challenge. Start by brainstorming ideas for the essay. Then, outline and write the essay using vivid sensory details and strong descriptions. Always polish your essay and proofread it so it is at its best.

Best Tips for Writing a Descriptive Essay

Outline the essay in sections and create a thesis statement to base the essay on. Then, write a strong introduction and describe the subject matter using creative and vivid adjectives. Use similes, metaphors, and your own emotions to help you bring the topic to life.

- You could also choose a fictional person to write about, such as a character in a book, a story, or a play. You could write about a character on your favorite TV show or video game.

- Another take on this option is to write about a made-up place or object, such as the fantastical school in your favorite book or the magic wand from your favorite TV show.

- You could also choose a more specific emotion, such as brotherly love or self-hatred. These emotions can make for powerful descriptive essays.

- For example, if you were writing about a person like your mother, you may write down under “sound” : “soft voice at night, clack of her shoes on the floor tiles, bang of the spoon when she cooks.”

- If you are writing the essay for a class, your instructor should specify if they want a five paragraph essay or if you have the freedom to use sections instead.

- For example, if you were writing a descriptive essay about your mother, you may have a thesis statement like: “In many ways, my mother is the reigning queen of our house, full of contradictions that we are too afraid to question.”

- For example, if you were writing the essay about your mom, you may start with: “My mother is not like other mothers. She is a fierce protector and a mysterious woman to my sisters and I.”

- If you were writing an essay about an object, you may start with: "Try as I might, I had a hard time keeping my pet rock alive."

- You can also use adjectives that connect to the senses, such “rotting,” “bright,” “hefty,” “rough,” and “pungent.”

- For example, you may describe your mother as "bright," "tough," and "scented with jasmine."

- You can also use similes, where you use “like” or “as” to compare one thing to another. For example, you may write, “My mother is like a fierce warrior in battle, if the battlefield were PTA meetings and the checkout line at the grocery store.”

- For example, you may write about your complicated feelings about your mother. You may note that you feel sadness about your mother’s sacrifices for the family and joy for the privileges you have in your life because of her.

- For example, you may end a descriptive essay about your mother by noting, “In all that she has sacrificed for us, I see her strength, courage, and fierce love for her family, traits I hope to emulate in my own life.”

- You can also read the essay aloud to others to get their feedback. Ask them to let you know if there are any unclear or vague sentences in the essay.

- Be open to constructive criticism and feedback from others. This will only make your essay stronger.

- If you have a word count requirement for the essay, make sure you meet it. Add more detail to the paper or take unnecessary content out to reach the word count.

Reader Videos

Share a quick video tip and help bring articles to life with your friendly advice. Your insights could make a real difference and help millions of people!

Tips from our Readers

- Start your essay with an attention-grabbing introduction that gives a good sense of the topic.

- Make sure to check your spelling and grammar when you're done!

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.writeexpress.com/descriptive-essay.html

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ https://www.iup.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/organization-and-structure/descriptive-writing.html

- ↑ https://spcollege.libguides.com/ld.php?content_id=10168248

- ↑ https://www.butte.edu/departments/cas/tipsheets/style_purpose_strategy/descriptive_essay.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/academic_writing/essay_writing/descriptive_essays.html

About This Article

To write a descriptive essay, start by choosing a topic, like a person, place, or specific emotion. Next, write down a list of sensory details about the topic, like how it sounds, smells, and feels. After this brainstorming session, outline the essay, dividing it into an introduction, 3 body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Open with a vivid introduction that uses sensory details, then introduce your thesis statement, which the rest of your essay should support. Strengthen your essay further by using metaphors and similes to describe your topic, and the emotions it evokes. To learn how to put the finishing touches on your essay, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Joshua Aigbe

Mar 25, 2021

Did this article help you?

Subaa Subaavarshini

Jul 13, 2020

Daniel Karibi

May 13, 2021

Aug 21, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

- Growth & Development

- Play & Activities

- Life Skills

- Play & Learning

- Learning & Education

- Rhymes & Songs

- Preschool Locator

A Visit To The Hospital – 10 Lines, Short & Long Essay For Kids

Key Points To Note: An Essay On ‘A Visit To The Hospital’ For Lower Primary Classes

10 lines on ‘a visit to the hospital’ for kids, short essay on ‘a visit to the hospital’ in english for kids, long essay on ‘a visit to the hospital’ for children, what will your child learn from this essay.

Essay writing is one section that plays an integral role for any student, from primary classes to university level. An essay on “A Visit To The Hospital” for classes 1, 2 and 3 is a popular topic for children. This essay helps in teaching young kids the importance of hospitals and doctors. They understand the benefits of good health as they write about the hospital, doctors and their role in our lives. Some kids are inspired to follow the medical profession after learning about the medical field. The essay on “A Visit To The Hospital” also helps young students in their comprehension lessons and class assignments.

Like all other essays, “A Visit To The Hospital” has the same structure. However, it is different from other essay topics. These key points will help lower primary students to write a good essay on the topic:

- Write and explain what a hospital is.

- Describe the hospital briefly you visited, some departments you had to go to, etc.

- Write about the role of doctors, nurses and other staff working in the hospital.

- Write why hospitals are necessary and their benefits.

Writing an essay for students of classes 1 and 2 seems difficult at first. Teachers and parents can ask them to write a few lines describing the topic to ease the process. Here are 10 lines on “A Visit To The Hospital” for reference:

- A hospital is an important place for every city, town, and village.

- It’s a place where a person goes to get treatment for illness or injury.

- Many doctors, nurses and ward boys work in a hospital.

- A hospital can have different departments for treating various illnesses such as cancer, cardiac, and pediatric health issues.

- I went to the hospital last week to see my ill grandmother.

- Doctors conducted many tests and checkups to diagnose the illness.

- The nurses were there to help the doctors and take care of patients.

- The hospital was very clean and hygienic.

- Some speciality hospitals treat only one kind of illness.

- Hospitals are a necessity for the treatment and health of people.

Young kids of lower primary classes are often asked to write a short paragraph to describe their hospital visits. Here is a short essay on “A Visit To The Hospital” for their reference:

A hospital is a place where sick and injured people get treatment and become healthy. Last week, I went to the hospital to see my ill grandmother. The hospital, from the outside, looked like any other large building, but inside there were many rooms, wards, departments, and doctors’ cabins. Many doctors in white coats were checking patients. Nurses in blue uniforms were helping them. Some ward boys were also there. They were taking patients for tests or cleaning the hospital. I was surprised to see how clean the hospital was! My mother told me cleanliness is necessary to avoid illness or infections. In the hospitals, there were different departments for different diseases. My mother said kids get treatment in the paediatric department. My grandmother was in the general ward. She was happy to see me. The doctors treated her illness for a few more days, and she returned home healthy.

Students of class 3 are expected to write a long essay on different topics. At this stage, teachers and parents believe they understand many words and sentence-making basics. Here is a long essay on “A Visit To The Hospital” for children:

A visit to the hospital is an experience worth noting. Last summer, my uncle met with an accident. I went to Shourie Hospital, where he was admitted. I visited a hospital for the first time in my life. I saw many people going in and coming out of the hospital building. My parents enquired about my uncle’s ward at the reception. He was in the general ward. There were many beds in that room. My uncle was resting on a bed with bandages covering his arms and legs. A doctor was attending to him, and a nurse was helping the doctor. My uncle felt better after the treatment.

After staying with my uncle for some time, I asked my father to see other hospital areas. He took me for a tour. My father kept telling me about various departments as we went around the hospital. He told me the cancer department is for treating cancer patients, and the general ward is for patients with common illnesses. In every ward, I saw doctors and nurses attending to patients. I felt good after seeing how attentive doctors and other staff were to patients. We even saw the operation theatre from the outside. There was a waiting area near the operation theatre, and relatives of people getting operated on were waiting there.

Outside the main hospital building, there was a huge garden. Many patients sat there with their attendants or ward boys. Then we went back to the general ward. I was happy to see him getting good care from the hospital staff. Being in the medical industry is indeed a noble profession.

A simple essay on hospital visits will teach your kids the value of health and the contribution of the medical staff to our lives and society. Kids will understand how much doctors and nurses work hard to treat patients and learn about different types of medical branches. So, an essay on a hospital visit will broaden their knowledge and make them aware of the benefits of good health and hygiene.

Writing an essay on a hospital visit makes the student understand a hospital’s role, work and importance. They learn to respect the hard work of hospital staff and doctors in treating patients.

Essay On Doctor for Class 1, 2 and 3 Children Essay On ‘Health Is Wealth’ for Classes 1 to 3 Kids How to Write Essay On A Visit To A Zoo for Lower Primary Classes

- Essays for Class 1

- Essays for Class 2

- Essays for Class 3

5 Recommended Books To Add To Your Child’s Reading List and Why

5 absolute must-watch movies and shows for kids, 15 indoor toys that have multiple uses and benefits, leave a reply cancel reply.

Log in to leave a comment

Most Popular

The best toys for newborns according to developmental paediatricians, the best toys for three-month-old baby brain development, recent comments.

FirstCry Intelli Education is an Early Learning brand, with products and services designed by educators with decades of experience, to equip children with skills that will help them succeed in the world of tomorrow.

The FirstCry Intellikit `Learn With Stories` kits for ages 2-6 brings home classic children`s stories, as well as fun activities, specially created by our Early Learning Educators.

For children 6 years and up, explore a world of STEAM learning, while engaging in project-based play to keep growing minds busy!

Build a love for reading through engaging book sets and get the latest in brain-boosting toys, recommended by the educators at FirstCry Intellitots.

Our Comprehensive 2-year Baby Brain Development Program brings to you doctor-approved toys for your baby`s developing brain.

Our Preschool Chain offers the best in education across India, for children ages 2 and up.

©2024 All rights reserved

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Welcome to the world of Intelli!

We have some FREE Activity E-books waiting for you. Fill in your details below so we can send you tailor- made activities for you and your little one.

Parent/Guardian's Name

Child's DOB

What would you like to receive other than your Free E-book? I would like information, discounts and offers on toys, books and products I want to find a FirstCry Intellitots Preschool near me I want access to resources for my child's development and/or education

Welcome to the world of intelli!

FREE guides and worksheets coming your way on whatsapp. Subscribe Below !!

THANK YOU!!!

Here are your free guides and worksheets.

- Added: 17/10/2018

- Course type: Vocabulary lessons

- No Comments

Vocabulary for describing hospitals (with detailed pictures and sentences!), Level A2-B1

Describing hospitals

At the end of this lesson, you will know how to describe hospitals in a thorough way.

This ‘ Describing Hospitals ‘ lesson will be done 10 Steps . It is better to do 1 Step at a time for lasting results.

Use a unilingual or bilingual dictionary for maximum efficiency. Checking how the words are pronounced is also a useful thing to do.

You can equally write down the words that you wish to remember.

Let’s start.

a) Describing Hospitals (Step 1) : Types

There are many types of hospitals. Do you recognise any of the above? How can we use these words in context? Below are a few examples:

- Rural hospitals are found in remote areas.

- Mental hospitals treat psychiatric diseases.

- Students can learn in academic as well as teaching hospitals.

- Geriatric hospitals are for elderly people.

- Public hospitals are often free or very cheap while private hospitals are expensive and unaffordable for most people.

Your turn: Pick five words from the picture and make sentences. Pay attention to spelling.

Now, let’s go to Step 2. It is all about describing a hospital ward.

b) Describing Hospitals (Step 2) : Adjectives

It is difficult to imagine how a hospital ward can be if you have never been hospitalised. In the picture above, you saw different types of words that can be used to describe a hospital ward. I have provided positive and negative Adjectives .

Below are a few examples:

- Being in a crammed ward can be distressing .

- Private hospitals often have wards that are safe , clean and nurturing.

- Spaciou s wards are good for a patient’s wellbeing.

- Crowded wards are unwelcoming.

- Bright and welcoming wards are much better than dark and dirty wards.

Your turn: Can you think of five other sentences to complete this series?

Once you have finished, we can proceed to Step 3 . It is about describing hospitals in a general manner.

c) Describing Hospitals (Step 3) : General Description

Some hospitals are excellent whereas some are mere death traps. Do you live near a hospital? What is it like?

Here are some examples that can help you to describe such a hospital.

- Understaffed hospitals are life-threatening .

- If you see a dilapidated hospital, don’t go there.

- Neglected hospitals cost people’s lives.

- Well-equipped hospitals are often expensive .

- Independent hospitals receive better funding.

Your turn: Make five sentences that use some of the vocabulary in the picture. Two of the sentences should include transitional words such as BUT and BECAUSE .

Once you are done, we can move on to Step 4 . In this step, we describe different types of diseases.

d) Describing Hospitals (Step 4) : Diseases

It is difficult to find positive words to describe diseases. When we are sick, we do not feel well and diseases are often debilitating. Have you ever been seriously ill? How can you describe that sickness?

- Common diseases are easy to treat.

- Incurable diseases are terrible .