- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning pp 2690–2693 Cite as

Problems: Definition, Types, and Evidence

- Norbert M. Seel 2

- Reference work entry

2120 Accesses

1 Citations

Problem solving

A distinction can be made between “task” and “problem.” Generally, a task is a well-defined piece of work that is usually imposed by another person and may be burdensome. A problem is generally considered to be a task, a situation, or person which is difficult to deal with or control due to complexity and intransparency. In everyday language, a problem is a question proposed for solution, a matter stated for examination or proof. In each case, a problem is considered to be a matter which is difficult to solve or settle, a doubtful case, or a complex task involving doubt and uncertainty.

Theoretical Background

The nature of human problem solving has been studied by psychologists over the past hundred years. Beginning with the early experimental work of the Gestalt psychologists in Germany, and continuing through the 1960s and early 1970s, research on problem solving typically operated with relatively simple laboratory problems, such as Duncker’s...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Berry, D. C., & Broadbent, D. E. (1995). Implicit learning in the control of complex systems: A reconsideration of some of the earlier claims. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European perspective (pp. 131–150). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Google Scholar

Broadbent, D. E. (1977). Levels, hierarchies, and the locus of control. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 29 , 181–201.

Article Google Scholar

Dörner, D. (1976). Problemlösen als Informationsverarbeitung . Stuttgart: Kohlhammer (Problem solving as information processing).

Dörner, D., Kreuzig, H. W., Reither, F., & Stäudel, T. (1983). Lohhausen. Vom Umgang mit Unbestimmtheit und Komplexität [Lohhausen. The concern with uncertainty and complexity] . Bern: Huber.

Dörner, D. (1989). Die Logik des Misslingens . Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Funke, J. (1992). Wissen über dynamische Systeme: Erwerb, Repräsentation und Anwendung . Berlin: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Funke, J., & Frensch, P. (1995). Complex problem solving research in North America and Europe: An integrative review. Foreign Psychology, 5 , 42–47.

Jonassen, D. H. (1997). Instructional design models for well-structured and ill-structured problem-solving learning outcomes. Educational Technology Research and Development, 45 (1), 65–94.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Newell, A., Shaw, J. C., & Simon, H. A. (1959). A general problem-solving program for a computer. Computers and Automation, 8 (7), 10–16.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Education, University of Freiburg, Rempartstr. 11, 3. OG, Freiburg, 79098, Germany

Prof. Norbert M. Seel ( Faculty of Economics and Behavioral Sciences )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Norbert M. Seel .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Economics and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Education, University of Freiburg, 79085, Freiburg, Germany

Norbert M. Seel

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Seel, N.M. (2012). Problems: Definition, Types, and Evidence. In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_914

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_914

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-1427-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-1428-6

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

Published on November 2, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on May 31, 2023.

A research problem is a specific issue or gap in existing knowledge that you aim to address in your research. You may choose to look for practical problems aimed at contributing to change, or theoretical problems aimed at expanding knowledge.

Some research will do both of these things, but usually the research problem focuses on one or the other. The type of research problem you choose depends on your broad topic of interest and the type of research you think will fit best.

This article helps you identify and refine a research problem. When writing your research proposal or introduction , formulate it as a problem statement and/or research questions .

Table of contents

Why is the research problem important, step 1: identify a broad problem area, step 2: learn more about the problem, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research problems.

Having an interesting topic isn’t a strong enough basis for academic research. Without a well-defined research problem, you are likely to end up with an unfocused and unmanageable project.

You might end up repeating what other people have already said, trying to say too much, or doing research without a clear purpose and justification. You need a clear problem in order to do research that contributes new and relevant insights.

Whether you’re planning your thesis , starting a research paper , or writing a research proposal , the research problem is the first step towards knowing exactly what you’ll do and why.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

As you read about your topic, look for under-explored aspects or areas of concern, conflict, or controversy. Your goal is to find a gap that your research project can fill.

Practical research problems

If you are doing practical research, you can identify a problem by reading reports, following up on previous research, or talking to people who work in the relevant field or organization. You might look for:

- Issues with performance or efficiency

- Processes that could be improved

- Areas of concern among practitioners

- Difficulties faced by specific groups of people

Examples of practical research problems

Voter turnout in New England has been decreasing, in contrast to the rest of the country.

The HR department of a local chain of restaurants has a high staff turnover rate.

A non-profit organization faces a funding gap that means some of its programs will have to be cut.

Theoretical research problems

If you are doing theoretical research, you can identify a research problem by reading existing research, theory, and debates on your topic to find a gap in what is currently known about it. You might look for:

- A phenomenon or context that has not been closely studied

- A contradiction between two or more perspectives

- A situation or relationship that is not well understood

- A troubling question that has yet to be resolved

Examples of theoretical research problems

The effects of long-term Vitamin D deficiency on cardiovascular health are not well understood.

The relationship between gender, race, and income inequality has yet to be closely studied in the context of the millennial gig economy.

Historians of Scottish nationalism disagree about the role of the British Empire in the development of Scotland’s national identity.

Next, you have to find out what is already known about the problem, and pinpoint the exact aspect that your research will address.

Context and background

- Who does the problem affect?

- Is it a newly-discovered problem, or a well-established one?

- What research has already been done?

- What, if any, solutions have been proposed?

- What are the current debates about the problem? What is missing from these debates?

Specificity and relevance

- What particular place, time, and/or group of people will you focus on?

- What aspects will you not be able to tackle?

- What will the consequences be if the problem is not resolved?

Example of a specific research problem

A local non-profit organization focused on alleviating food insecurity has always fundraised from its existing support base. It lacks understanding of how best to target potential new donors. To be able to continue its work, the organization requires research into more effective fundraising strategies.

Once you have narrowed down your research problem, the next step is to formulate a problem statement , as well as your research questions or hypotheses .

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them.

In general, they should be:

- Focused and researchable

- Answerable using credible sources

- Complex and arguable

- Feasible and specific

- Relevant and original

Your research objectives indicate how you’ll try to address your research problem and should be specific:

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, May 31). How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 16, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-problem/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a strong hypothesis | steps & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Problem Solving and Decision Making

Introduction.

- General Approaches to Problem Solving

- Representational Accounts

- Problem Space and Search

- Working Memory and Problem Solving

- Domain-Specific Problem Solving

- The Rational Approach

- Prospect Theory

- Dual-Process Theory

- Cognitive Heuristics and Biases

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Psychology

- Counterfactual Reasoning

- Critical Thinking

- Heuristics and Biases

- Protocol Analysis

- Psychology and Law

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Data Visualization

- Remote Work

- Workforce Training Evaluation

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Problem Solving and Decision Making by Emily G. Nielsen , John Paul Minda LAST MODIFIED: 26 June 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0246

Problem solving and decision making are both examples of complex, higher-order thinking. Both involve the assessment of the environment, the involvement of working memory or short-term memory, reliance on long term memory, effects of knowledge, and the application of heuristics to complete a behavior. A problem can be defined as an impasse or gap between a current state and a desired goal state. Problem solving is the set of cognitive operations that a person engages in to change the current state, to go beyond the impasse, and achieve a desired outcome. Problem solving involves the mental representation of the problem state and the manipulation of this representation in order to move closer to the goal. Problems can vary in complexity, abstraction, and how well defined (or not) the initial state and the goal state are. Research has generally approached problem solving by examining the behaviors and cognitive processes involved, and some work has examined problem solving using computational processes as well. Decision making is the process of selecting and choosing one action or behavior out of several alternatives. Like problem solving, decision making involves the coordination of memories and executive resources. Research on decision making has paid particular attention to the cognitive biases that account for suboptimal decisions and decisions that deviate from rationality. The current bibliography first outlines some general resources on the psychology of problem solving and decision making before examining each of these topics in detail. Specifically, this review covers cognitive, neuroscientific, and computational approaches to problem solving, as well as decision making models and cognitive heuristics and biases.

General Overviews

Current research in the area of problem solving and decision making is published in both general and specialized scientific journals. Theoretical and scholarly work is often summarized and developed in full-length books and chapter. These may focus on the subfields of problem solving and decision making or the larger field of thinking and higher-order cognition.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Psychology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abnormal Psychology

- Academic Assessment

- Acculturation and Health

- Action Regulation Theory

- Action Research

- Addictive Behavior

- Adolescence

- Adoption, Social, Psychological, and Evolutionary Perspect...

- Advanced Theory of Mind

- Affective Forecasting

- Affirmative Action

- Ageism at Work

- Allport, Gordon

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Ambulatory Assessment in Behavioral Science

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA)

- Animal Behavior

- Animal Learning

- Anxiety Disorders

- Art and Aesthetics, Psychology of

- Assessment and Clinical Applications of Individual Differe...

- Attachment in Social and Emotional Development across the ...

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Childre...

- Attitudinal Ambivalence

- Attraction in Close Relationships

- Attribution Theory

- Authoritarian Personality

- Bayesian Statistical Methods in Psychology

- Behavior Therapy, Rational Emotive

- Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Genetics

- Belief Perseverance

- Bereavement and Grief

- Biological Psychology

- Birth Order

- Body Image in Men and Women

- Bystander Effect

- Categorical Data Analysis in Psychology

- Childhood and Adolescence, Peer Victimization and Bullying...

- Clark, Mamie Phipps

- Clinical Neuropsychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Consistency Theories

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Communication, Nonverbal Cues and

- Comparative Psychology

- Competence to Stand Trial: Restoration Services

- Competency to Stand Trial

- Computational Psychology

- Conflict Management in the Workplace

- Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

- Consciousness

- Coping Processes

- Correspondence Analysis in Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Creativity at Work

- Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Cultural Psychology

- Daily Life, Research Methods for Studying

- Data Science Methods for Psychology

- Data Sharing in Psychology

- Death and Dying

- Deceiving and Detecting Deceit

- Defensive Processes

- Depressive Disorders

- Development, Prenatal

- Developmental Psychology (Cognitive)

- Developmental Psychology (Social)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM...

- Discrimination

- Dissociative Disorders

- Drugs and Behavior

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Psychology

- Educational Settings, Assessment of Thinking in

- Effect Size

- Embodiment and Embodied Cognition

- Emerging Adulthood

- Emotional Intelligence

- Empathy and Altruism

- Employee Stress and Well-Being

- Environmental Neuroscience and Environmental Psychology

- Ethics in Psychological Practice

- Event Perception

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Expansive Posture

- Experimental Existential Psychology

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Eyewitness Testimony

- Eysenck, Hans

- Factor Analysis

- Festinger, Leon

- Five-Factor Model of Personality

- Flynn Effect, The

- Forensic Psychology

- Forgiveness

- Friendships, Children's

- Fundamental Attribution Error/Correspondence Bias

- Gambler's Fallacy

- Game Theory and Psychology

- Geropsychology, Clinical

- Global Mental Health

- Habit Formation and Behavior Change

- Health Psychology

- Health Psychology Research and Practice, Measurement in

- Heider, Fritz

- History of Psychology

- Human Factors

- Humanistic Psychology

- Implicit Association Test (IAT)

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Inferential Statistics in Psychology

- Insanity Defense, The

- Intelligence

- Intelligence, Crystallized and Fluid

- Intercultural Psychology

- Intergroup Conflict

- International Classification of Diseases and Related Healt...

- International Psychology

- Interviewing in Forensic Settings

- Intimate Partner Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Introversion–Extraversion

- Item Response Theory

- Law, Psychology and

- Lazarus, Richard

- Learned Helplessness

- Learning Theory

- Learning versus Performance

- LGBTQ+ Romantic Relationships

- Lie Detection in a Forensic Context

- Life-Span Development

- Locus of Control

- Loneliness and Health

- Mathematical Psychology

- Meaning in Life

- Mechanisms and Processes of Peer Contagion

- Media Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Mediation Analysis

- Memories, Autobiographical

- Memories, Flashbulb

- Memories, Repressed and Recovered

- Memory, False

- Memory, Human

- Memory, Implicit versus Explicit

- Memory in Educational Settings

- Memory, Semantic

- Meta-Analysis

- Metacognition

- Metaphor, Psychological Perspectives on

- Microaggressions

- Military Psychology

- Mindfulness

- Mindfulness and Education

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- Money, Psychology of

- Moral Conviction

- Moral Development

- Moral Psychology

- Moral Reasoning

- Nature versus Nurture Debate in Psychology

- Neuroscience of Associative Learning

- Nonergodicity in Psychology and Neuroscience

- Nonparametric Statistical Analysis in Psychology

- Observational (Non-Randomized) Studies

- Obsessive-Complusive Disorder (OCD)

- Occupational Health Psychology

- Olfaction, Human

- Operant Conditioning

- Optimism and Pessimism

- Organizational Justice

- Parenting Stress

- Parenting Styles

- Parents' Beliefs about Children

- Path Models

- Peace Psychology

- Perception, Person

- Performance Appraisal

- Personality and Health

- Personality Disorders

- Personality Psychology

- Phenomenological Psychology

- Placebo Effects in Psychology

- Play Behavior

- Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

- Positive Psychology

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Prejudice and Stereotyping

- Pretrial Publicity

- Prisoner's Dilemma

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Procrastination

- Prosocial Behavior

- Prosocial Spending and Well-Being

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Literacy

- Psychological Perspectives on Food and Eating

- Psychology, Political

- Psychoneuroimmunology

- Psychophysics, Visual

- Psychotherapy

- Psychotic Disorders

- Publication Bias in Psychology

- Reasoning, Counterfactual

- Rehabilitation Psychology

- Relationships

- Reliability–Contemporary Psychometric Conceptions

- Religion, Psychology and

- Replication Initiatives in Psychology

- Research Methods

- Risk Taking

- Role of the Expert Witness in Forensic Psychology, The

- Sample Size Planning for Statistical Power and Accurate Es...

- Schizophrenic Disorders

- School Psychology

- School Psychology, Counseling Services in

- Self, Gender and

- Self, Psychology of the

- Self-Construal

- Self-Control

- Self-Deception

- Self-Determination Theory

- Self-Efficacy

- Self-Esteem

- Self-Monitoring

- Self-Regulation in Educational Settings

- Self-Report Tests, Measures, and Inventories in Clinical P...

- Sensation Seeking

- Sex and Gender

- Sexual Minority Parenting

- Sexual Orientation

- Signal Detection Theory and its Applications

- Simpson's Paradox in Psychology

- Single People

- Single-Case Experimental Designs

- Skinner, B.F.

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Small Groups

- Social Class and Social Status

- Social Cognition

- Social Neuroscience

- Social Support

- Social Touch and Massage Therapy Research

- Somatoform Disorders

- Spatial Attention

- Sports Psychology

- Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE): Icon and Controversy

- Stereotype Threat

- Stereotypes

- Stress and Coping, Psychology of

- Student Success in College

- Subjective Wellbeing Homeostasis

- Taste, Psychological Perspectives on

- Teaching of Psychology

- Terror Management Theory

- Testing and Assessment

- The Concept of Validity in Psychological Assessment

- The Neuroscience of Emotion Regulation

- The Reasoned Action Approach and the Theories of Reasoned ...

- The Weapon Focus Effect in Eyewitness Memory

- Theory of Mind

- Therapies, Person-Centered

- Therapy, Cognitive-Behavioral

- Thinking Skills in Educational Settings

- Time Perception

- Trait Perspective

- Trauma Psychology

- Twin Studies

- Type A Behavior Pattern (Coronary Prone Personality)

- Unconscious Processes

- Video Games and Violent Content

- Virtues and Character Strengths

- Women and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM...

- Women, Psychology of

- Work Well-Being

- Wundt, Wilhelm

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.147.128.134]

- 185.147.128.134

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Problem solving articles from across Nature Portfolio

Problem solving is the mental process of analyzing a situation, learning what options are available, and then choosing the alternative that will result in the desired outcome or some other selected goal.

Latest Research and Reviews

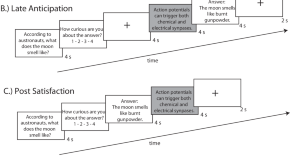

States of epistemic curiosity interfere with memory for incidental scholastic facts

- Nicole E. Keller

- Carola Salvi

- Joseph E. Dunsmoor

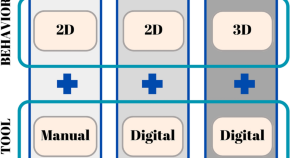

Neurocognitive responses to spatial design behaviors and tools among interior architecture students: a pilot study

- Yaren Şekerci

- Mehmet Uğur Kahraman

- Sevgi Şengül Ayan

Association of executive function with suicidality based on resting-state functional connectivity in young adults with subthreshold depression

- Je-Yeon Yun

- Soo-Hee Choi

- Joon Hwan Jang

Spatially embedded recurrent neural networks reveal widespread links between structural and functional neuroscience findings

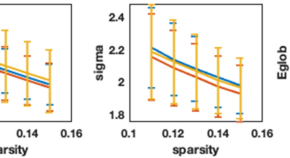

A fundamental question in neuroscience is what are the constraints that shape the structural and functional organization of the brain. By bringing biological cost constraints into the optimization process of artificial neural networks, Achterberg, Akarca and colleagues uncover the joint principle underlying a large set of neuroscientific findings.

- Jascha Achterberg

- Danyal Akarca

- Duncan E. Astle

Reverse effect of home-use binaural beats brain stimulation

- Michal Klichowski

- Andrzej Wicher

- Roman Golebiewski

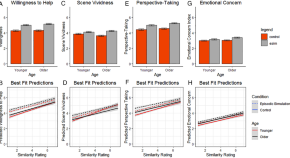

Effect of situation similarity on younger and older adults’ episodic simulation of helping behaviours

- A. Dawn Ryan

- Ronald Smitko

- Karen L. Campbell

News and Comment

Reliable social switch.

The macaque homologue of the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex tracks the reliability of social information and determines whether this information is used to guide choices during decision making.

- Jake Rogers

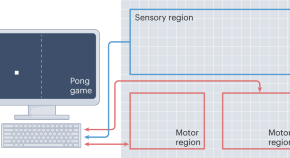

DishBrain plays Pong and promises more

An in vitro biological system of cultured brain cells has learned to play Pong. This feat opens up an avenue towards the convergence of biological and machine intelligence.

- Joshua Goldwag

Tinkering with tools leads to more success

- Teresa Schubert

Parallel processing of alternative approaches

Neuronal activity in the secondary motor cortex of mice engaged in a foraging task simultaneously represents multiple alternative decision-making strategies.

- Katherine Whalley

Teaching of 21st century skills needs to be informed by psychological research

The technological advancements and globalization of the 21st century require a broad set of skills beyond traditional subjects such as mathematics, reading, and science. Research in psychological science should inform best practice and evidence-based recommendations for teaching these skills.

- Samuel Greiff

- Francesca Borgonovi

Simulated brain solves problems

Quick links.

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE : A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps exist in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people]. Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it but simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to a the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something that needs to be investigated.

IV. Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be investigated. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and helps define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

V. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., perhaps there's a hospital in the community ten miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital, but it was conducted ten years ago]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; D'Souza, Victor S. "Use of Induction and Deduction in Research in Social Sciences: An Illustration." Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (1982): 655-661; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question. The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question. [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 10:20 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Table of Contents

The problem-solving process, how to solve problems: 5 steps, train to solve problems with lean today, what is problem solving steps, techniques, & best practices explained.

Problem solving is the art of identifying problems and implementing the best possible solutions. Revisiting your problem-solving skills may be the missing piece to leveraging the performance of your business, achieving Lean success, or unlocking your professional potential.

Ask any colleague if they’re an effective problem-solver and their likely answer will be, “Of course! I solve problems every day.”

Problem solving is part of most job descriptions, sure. But not everyone can do it consistently.

Problem solving is the process of defining a problem, identifying its root cause, prioritizing and selecting potential solutions, and implementing the chosen solution.

There’s no one-size-fits-all problem-solving process. Often, it’s a unique methodology that aligns your short- and long-term objectives with the resources at your disposal. Nonetheless, many paradigms center problem solving as a pathway for achieving one’s goals faster and smarter.

One example is the Six Sigma framework , which emphasizes eliminating errors and refining the customer experience, thereby improving business outcomes. Developed originally by Motorola, the Six Sigma process identifies problems from the perspective of customer satisfaction and improving product delivery.

Lean management, a similar method, is about streamlining company processes over time so they become “leaner” while producing better outcomes.

Trendy business management lingo aside, both of these frameworks teach us that investing in your problem solving process for personal and professional arenas will bring better productivity.

1. Precisely Identify Problems

As obvious as it seems, identifying the problem is the first step in the problem-solving process. Pinpointing a problem at the beginning of the process will guide your research, collaboration, and solutions in the right direction.

At this stage, your task is to identify the scope and substance of the problem. Ask yourself a series of questions:

- What’s the problem?

- How many subsets of issues are underneath this problem?

- What subject areas, departments of work, or functions of business can best define this problem?

Although some problems are naturally large in scope, precision is key. Write out the problems as statements in planning sheets . Should information or feedback during a later step alter the scope of your problem, revise the statements.

Framing the problem at this stage will help you stay focused if distractions come up in later stages. Furthermore, how you frame a problem will aid your search for a solution. A strategy of building Lean success, for instance, will emphasize identifying and improving upon inefficient systems.

2. Collect Information and Plan

The second step is to collect information and plan the brainstorming process. This is another foundational step to road mapping your problem-solving process. Data, after all, is useful in identifying the scope and substance of your problems.

Collecting information on the exact details of the problem, however, is done to narrow the brainstorming portion to help you evaluate the outcomes later. Don’t overwhelm yourself with unnecessary information — use the problem statements that you identified in step one as a north star in your research process.

This stage should also include some planning. Ask yourself:

- What parties will ultimately decide a solution?

- Whose voices and ideas should be heard in the brainstorming process?

- What resources are at your disposal for implementing a solution?

Establish a plan and timeline for steps 3-5.

3. Brainstorm Solutions

Brainstorming solutions is the bread and butter of the problem-solving process. At this stage, focus on generating creative ideas. As long as the solution directly addresses the problem statements and achieves your goals, don’t immediately rule it out.

Moreover, solutions are rarely a one-step answer and are more like a roadmap with a set of actions. As you brainstorm ideas, map out these solutions visually and include any relevant factors such as costs involved, action steps, and involved parties.

With Lean success in mind, stay focused on solutions that minimize waste and improve the flow of business ecosystems.

Become a Quality Management Professional

- 10% Growth In Jobs Of Quality Managers Profiles By 2025

- 11% Revenue Growth For Organisations Improving Quality

Certified Lean Six Sigma Green Belt

- 4 hands-on projects to perfect the skills learnt

- 4 simulation test papers for self-assessment

Lean Six Sigma Expert

- IASSC® Lean Six Sigma Green Belt and Black Belt certification

- 13 Projects, 12 Simulation exams, 18 Case Studies & 114 PDUs

Here's what learners are saying regarding our programs:

Xueting Liu

Mechanical engineer student at sargents pty. ltd. ,.

A great training and proper exercise with step-by-step guide! I'll give a rating of 10 out of 10 for this training.

Abdus Salam

I have completed the Lean Six Sigma Expert Master’s Program from Simplilearn. And after the course, I could take up new projects and perform better. My average pay rate for a research position increased by 21%.

4. Decide and Implement

The most critical stage is selecting a solution. Easier said than done. Consider the criteria that has arisen in previous steps as you decide on a solution that meets your needs.

Once you select a course of action, implement it.

Practicing due diligence in earlier stages of the process will ensure that your chosen course of action has been evaluated from all angles. Often, efficient implementation requires us to act correctly and successfully the first time, rather than being hurried and sloppy. Further compilations will create more problems, bringing you back to step 1.

5. Evaluate

Exercise humility and evaluate your solution honestly. Did you achieve the results you hoped for? What would you do differently next time?

As some experts note, formulating feedback channels into your evaluation helps solidify future success. A framework like Lean success, for example, will use certain key performance indicators (KPIs) like quality, delivery success, reducing errors, and more. Establish metrics aligned with company goals to assess your solutions.

Master skills like measurement system analysis, lean principles, hypothesis testing, process analysis and DFSS tools with our Lean Six Sigma Green Belt Training Course . Sign-up today!

Become a quality expert with Simplilearn’s Lean Six Sigma Green Belt . This Lean Six Sigma certification program will help you gain key skills to excel in digital transformation projects while improving quality and ultimate business results.

In this course, you will learn about two critical operations management methodologies – Lean practices and Six Sigma to accelerate business improvement.

Our Quality Management Courses Duration And Fees

Explore our top Quality Management Courses and take the first step towards career success

Get Free Certifications with free video courses

Quality Management

Lean Management

Project Management

Learn from industry experts with free masterclasses, digital marketing.

The Top 10 AI Tools You Need to Master Marketing in 2024

Unlock Digital Marketing Career Success Secrets for 2024 with Purdue University

Your Gateway to Game-changing Digital Marketing Careers in 2024 with Purdue University

Recommended Reads

Introduction to Machine Learning: A Beginner's Guide

Webinar Wrap-up: Mastering Problem Solving: Career Tips for Digital Transformation Jobs

An Ultimate Guide That Helps You to Develop and Improve Problem Solving in Programming

Free eBook: 21 Resources to Find the Data You Need

ITIL Problem Workaround: A Leader’s Guide to Manage Problems

Your One-Stop Solution to Understand Coin Change Problem

Get Affiliated Certifications with Live Class programs

- PMP, PMI, PMBOK, CAPM, PgMP, PfMP, ACP, PBA, RMP, SP, and OPM3 are registered marks of the Project Management Institute, Inc.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Analysing Complex Problem-Solving Strategies from a Cognitive Perspective: The Role of Thinking Skills

1 MTA-SZTE Digital Learning Technologies Research Group, Center for Learning and Instruction, University of Szeged, 6722 Szeged, Hungary

Gyöngyvér Molnár

2 MTA-SZTE Digital Learning Technologies Research Group, Institute of Education, University of Szeged, 6722 Szeged, Hungary; uh.degezs-u.yspde@ranlomyg

Associated Data

The data used to support the findings cannot be shared at this time as it also forms part of an ongoing study.

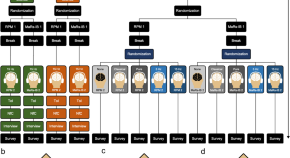

Complex problem solving (CPS) is considered to be one of the most important skills for successful learning. In an effort to explore the nature of CPS, this study aims to investigate the role of inductive reasoning (IR) and combinatorial reasoning (CR) in the problem-solving process of students using statistically distinguishable exploration strategies in the CPS environment. The sample was drawn from a group of university students (N = 1343). The tests were delivered via the eDia online assessment platform. Latent class analyses were employed to seek students whose problem-solving strategies showed similar patterns. Four qualitatively different class profiles were identified: (1) 84.3% of the students were proficient strategy users, (2) 6.2% were rapid learners, (3) 3.1% were non-persistent explorers, and (4) 6.5% were non-performing explorers. Better exploration strategy users showed greater development in thinking skills, and the roles of IR and CR in the CPS process were varied for each type of strategy user. To sum up, the analysis identified students’ problem-solving behaviours in respect of exploration strategy in the CPS environment and detected a number of remarkable differences in terms of the use of thinking skills between students with different exploration strategies.

1. Introduction

Problem solving is part and parcel of our daily activities, for instance, in determining what to wear in the morning, how to use our new electronic devices, how to reach a restaurant by public transport, how to arrange our schedule to achieve the greatest work efficiency and how to communicate with people in a foreign country. In most cases, it is essential to solve the problems that recur in our study, work and daily lives. These situations require problem solving. Generally, problem solving is the thinking that occurs if we want “to overcome barriers between a given state and a desired goal state by means of behavioural and/or cognitive, multistep activities” ( Frensch and Funke 1995, p. 18 ). It has also been considered as one of the most important skills for successful learning in the 21st century. This study focuses on one specific kind of problem solving, complex problem solving (CPS). (Numerous other terms are also used ( Funke et al. 2018 ), such as interactive problem solving ( Greiff et al. 2013 ; Wu and Molnár 2018 ), and creative problem solving ( OECD 2010 ), etc.).

CPS is a transversal skill ( Greiff et al. 2014 ), operating several mental activities and thinking skills (see Molnár et al. 2013 ). In order to explore the nature of CPS, some studies have focused on detecting its component skills ( Wu and Molnár 2018 ), whereas others have analysed students’ behaviour during the problem-solving process ( Greiff et al. 2018 ; Wu and Molnár 2021 ). This study aims to link these two fields by investigating the role of thinking skills in learning by examining students’ use of statistically distinguishable exploration strategies in the CPS environment.

1.1. Complex Problem Solving: Definition, Assessment and Relations to Intelligence

According to a widely accepted definition proposed by Buchner ( 1995 ), CPS is “the successful interaction with task environments that are dynamic (i.e., change as a function of users’ intervention and/or as a function of time) and in which some, if not all, of the environment’s regularities can only be revealed by successful exploration and integration of the information gained in that process” ( Buchner 1995, p. 14 ). A CPS process is split into two phases, knowledge acquisition and knowledge application. In the knowledge acquisition (KAC) phase of CPS, the problem solver understands the problem itself and stores the acquired information ( Funke 2001 ; Novick and Bassok 2005 ). In the knowledge application (KAP) phase, the problem solver applies the acquired knowledge to bring about the transition from a given state to a goal state ( Novick and Bassok 2005 ).

Problem solving, especially CPS, has frequently been compared or linked to intelligence in previous studies (e.g., Beckmann and Guthke 1995 ; Stadler et al. 2015 ; Wenke et al. 2005 ). Lotz et al. ( 2017 ) observed that “intelligence and [CPS] are two strongly overlapping constructs” (p. 98). There are many similarities and commonalities that can be detected between CPS and intelligence. For instance, CPS and intelligence share some of the same key features, such as the integration of information ( Stadler et al. 2015 ). Furthermore, Wenke et al. ( 2005 ) stated that “the ability to solve problems has featured prominently in virtually every definition of human intelligence” (p. 9); meanwhile, from the opposite perspective, intelligence has also been considered as one of the most important predictors of the ability to solve problems ( Wenke et al. 2005 ). Moreover, the relation between CPS and intelligence has also been discussed from an empirical perspective. A meta-analysis conducted by Stadler et al. ( 2015 ) selected 47 empirical studies (total sample size N = 13,740) which focused on the correlation between CPS and intelligence. The results of their analysis confirmed that a correlation between CPS and intelligence exists with a moderate effect size of M(g) = 0.43.

Due to the strong link between CPS and intelligence, assessments of these two domains have been connected and have overlapped to a certain extent. For instance, Beckmann and Guthke ( 1995 ) observed that some of the intelligence tests “capture something akin to an individual’s general ability to solve problems (e.g., Sternberg 1982 )” (p. 184). Nowadays, some widely used CPS assessment methods are related to intelligence but still constitute a distinct construct ( Schweizer et al. 2013 ), such as the MicroDYN approach ( Greiff and Funke 2009 ; Greiff et al. 2012 ; Schweizer et al. 2013 ). This approach uses the minimal complex system to simulate simplistic, artificial but still complex problems following certain construction rules ( Greiff and Funke 2009 ; Greiff et al. 2012 ).

The MicroDYN approach has been widely employed to measure problem solving in a well-defined problem context (i.e., “problems have a clear set of means for reaching a precisely described goal state”, Dörner and Funke 2017, p. 1 ). To complete a task based on the MicroDYN approach, the problem solver engages in dynamic interaction with the task to acquire relevant knowledge. It is not possible to create this kind of test environment with the traditional paper-and-pencil-based method. Therefore, it is currently only possible to conduct a MicroDYN-based CPS assessment within the computer-based assessment framework. In the context of computer-based assessment, the problem-solvers’ operations were recorded and logged by the assessment platform. Thus, except for regular achievement-focused result data, logfile data are also available for analysis. This provides the option of exploring and monitoring problem solvers’ behaviour and thinking processes, specifically, their exploration strategies, during the problem-solving process (see, e.g., Chen et al. 2019 ; Greiff et al. 2015a ; Molnár and Csapó 2018 ; Molnár et al. 2022 ; Wu and Molnár 2021 ).

Problem solving, in the context of an ill-defined problem (i.e., “problems have no clear problem definition, their goal state is not defined clearly, and the means of moving towards the (diffusely described) goal state are not clear”, Dörner and Funke 2017, p. 1), involved a different cognitive process than that in the context of a well-defined problem ( Funke 2010 ; Schraw et al. 1995 ), and it cannot be measured with the MicroDYN approach. The nature of ill-defined problem solving has been explored and discussed in numerous studies (e.g., Dörner and Funke 2017 ; Hołda et al. 2020 ; Schraw et al. 1995 ; Welter et al. 2017 ). This will not be discussed here as this study focuses on well-defined problem solving.

1.2. Inductive and Combinatorial Reasoning as Component Skills of Complex Problem Solving