How the war in Iraq changed the world—and what change could come next

Navigate our coverage

How the iraq war changed…, what iraq needs now, what the united states can do now.

Twenty years on from the US invasion of the country, Iraq has fallen off the policymaking agenda in Washington, DC—cast aside in part as a result of the bitter experience of the war, the enormous human toll it exacted, and the passage of time. But looking forward twenty years and beyond, Iraqis need a great deal from their own leaders and those of their erstwhile liberators. A national reconciliation commission, a new constitution, and an economy less dependent on oil revenue are just some of the areas the experts at the Atlantic Council’s Iraq Initiative highlight in this collection of reflections marking two decades since the US invasion.

What else will it take to transform Iraq into a prosperous, productive regional player? What can the United States do now, with twenty years’ worth of hindsight? And just how far-reaching were the effects of the war? Twenty-one experts from across the Atlantic Council take on these questions in a series of short essays and video interviews below.

Oula Kadhum on what March 20, 2003 was like for a young Iraqi

Scroll and click through the carousel below to jump to a response:

The cause of democracy in the region

When the United States invaded Iraq two decades ago, one of the public justifications for the war was that it would help spread democracy throughout the Middle East. The invasion, of course, had the opposite effect: it unleashed a bloody sectarian conflict in Iraq, badly undermining the reputation of democracy in the region and America’s credibility in promoting it.

Yet the frictions between rulers and ruled that helped precipitate the US invasion of Iraq persist. The citizens of the region, increasingly educated and connected to the rest of the world, have twenty-first-century political aspirations, but continue to be ruled by unaccountable nineteenth-century-style autocrats. Absent a change, these frictions will continue to shape political developments in the region, often in cataclysmic fashion, over the next two decades.

The George W. Bush administration’s failures in Iraq severely set back the cause of democracy in the region. In the perceptions of Arab publics, democratization became synonymous with the exercise of American military power. Meanwhile, Iraq’s chaos strengthened the hand of the region’s autocrats: as inept or heavy-handed as their own rule might be, it paled in comparison to the breakdown of order and human slaughter in Iraq.

Citizens’ frustrations with their political leaders finally erupted in the Arab Spring of 2010 and 2011, but their protests failed to end autocracy in the region. Gulf monarchs were able to throw money at the problem, first to shore up their own rule and then other autocracies in the region. The Egyptian experiment with democracy proved short-lived; Tunisia’s endured far longer but also appears over. More broadly, the region has seen democratic backsliding in Lebanon and Israel as well.

The yawning gap between what citizens want and what they get from their governments remains. The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators show that, on aggregate, states in the region are no more politically stable, effectively governed, accountable, or participatory than two decades ago. Unless political leaders address that gap, further Arab Spring-like protests—or even social revolution—are probable.

Having apparently gotten out of the business of invasion and occupation following the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States could play a new and constructive role here. It could both cajole and assist the region’s political leaders to improve governance for their citizens.

The United States exacerbated political tensions in the region two decades ago; now it has an opportunity to help ameliorate them.

— Stephen R. Grand is the author of Understanding Tahrir Square: What Transitions Elsewhere Can Teach Us About the Prospects for Arab Democracy . He is a nonresident senior fellow with the Council’s Middle East programs.

⏎ Return to top of section

State sovereignty

Since the seventeenth century, more or less, world order has been based on the concept of state sovereignty: states are deemed to hold the monopoly of force within mutually recognized territories, and they are generally prohibited from intervening in one another’s domestic affairs. The invasion of Iraq challenged this standard in three important ways.

First, the fact of the war represented a direct attack on the sovereignty of the Iraqi state, which undermined the ban on aggressive war. While the Bush administration cast the invasion as a case of preemptive self-defense, it was widely seen as a preventive war of choice against a state that did not pose a clear and present danger. Moreover, the main exceptions to sovereignty that have developed over time, such as ongoing mass atrocities or United Nations authority, were not applicable in Iraq. Thus, the United States dealt a major blow to the rules-based international system of which it was one of the chief architects. This may have made more imaginable later crimes of aggression by other states.

Second, the means of the war, and especially the occupation, powered the reemergence of the private military industry. Driven by the need to sustain two long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the US armed forces became dependent on military contractors, which sometimes involved authorizing paid civilians to kill . The US effort to (re)privatize warfare brought back into fashion the use of private military force, generating a multibillion-dollar industry that is here to stay. Over time the spread of private military companies could unspool the state’s exclusive claim to violence and hammer the foundations of the current international system.

Third, the consequences of the war led to the spectacular empowerment of armed nonstate actors in the region and beyond, who launched a full-frontal assault on the sovereignty of many states. The Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, of course, emerged amid the brutal contestation of power in post-invasion Iraq and pursued its “caliphate” as an alternative (Sunni) political institution to rival the nation-state. While the threat has been contained, for now, in the Middle East, it is only beginning to gather force on the African continent. In addition, because Iran effectively won the war in Iraq, it was able to sponsor a deep bench of Shia nonstate groups which have eroded state sovereignty in Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, and Iraq itself.

The US invasion of Iraq left us a world with less respect for state sovereignty, more guns for hire, and a dizzying array of well-armed and determined nonstate groups.

— Alia Brahimi is a nonresident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs and host of the Guns for Hire podcast.

Abbas Kadhim on the opportunities missed

US-Turkish ties

By launching a war on Turkey’s border, against Turkish advice, in a manner that prejudiced Turkish interests, the United States in 2003 upended a strategic understanding that had dominated bilateral relations for five decades.

During and immediately after the Cold War, Turkey and the United States shared a strategic vision centered on containing the Soviet Union and its proxies. In exchange for strategic cooperation, Washington provided aid, modulated criticisms of Turkish politics, and deferred to Ankara’s sensitivities regarding its geopolitical neighborhood. With notable exceptions (e.g., Turkish opposition to the Vietnam War and US opposition to Turkey’s 1974 Cyprus operation), consensus was the norm and aspiration of both sides. After close collaboration in the Balkans , Somalia , Iraq, and Afghanistan from 1991 to 2001, though, Ankara became increasingly alarmed about the prospect of a new war in Iraq.

Bilateral relations deteriorated sharply after the Turkish parliament voted against allowing the United States to launch combat operations from Turkish soil. The war was longer, bloodier, and costlier than its planners had anticipated. The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (known as the PKK and designated by the United States as a terrorist organization in 1997) ended a cease-fire in place since the 1999 capture of its founder, Abdullah Öcalan, and gained broad new freedom of movement and action in northern Iraq. US military aid to Turkey ended, while defense industrial cooperation and military-to-military contacts dropped. In July 2003 US soldiers detained and hooded a Turkish special forces team in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq, on suspicions that they were colluding with insurgents. This event, coupled with Turkish anger over the bitter conduct and conclusion of the prewar negotiations, helped fuel a sustained rise in negative views about the United States among the Turkish public.

Sanctions and the war in Iraq damaged Turkish economic interests, though these would rebound from 2005 onward. The relationship of the US military to the PKK— first as tacit tolerance of PKK attacks into Turkey from northern Iraq despite the US presence, and later with employment of the PKK affiliate in Syria as a proxy force against the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS)—rendered the frictions of 2003 permanent. That US forces train, equip, and operate with a PKK-linked militia along Turkey’s border today is fruit of the Iraq war, because US-PKK contacts were brokered in northern Iraq, and US indifference to Turkish security redlines traces back to 2003.

The story of US-Turkish estrangement can be told from other perspectives: that Ankara sought strategic independence for reasons broader than Iraq, that President Erdoğan’s anti-Westernism drove divergence, that the countries have fewer shared interests now. There may be truth in these arguments, though they are based largely on speculation and imputed motives. Yet they, too, cannot be viewed except through the lens of the 2003 Iraq War, which came as Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party was assuming power and greatly influenced his subsequent decision-making.

Many effects of the Iraq War have faded, but the strategic alienation of Turkey and the United States has not.

— Rich Outzen , a retired colonel, is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council IN TURKEY and a geopolitical analyst and consultant currently serving private-sector clients as Dragoman LLC.

China’s rise

As George W. Bush took office in 2001, managing the US-China relationship was regarded as a top foreign policy concern. The administration’s focus shifted with 9/11 and a wartime footing—which in turn altered Beijing’s foreign policy and engagement in the Middle East.

A high point in US-China tension came in April with the Hainan Island Incident. The collision of a US signals intelligence aircraft and a Chinese interceptor jet resulted in one dead Chinese pilot and the detention of twenty-four US crew members, whose release followed US Ambassador Joseph Prueher’s delivery of the “ letter of the two sorries .”

But after the September 11 attacks, the United States launched the global war on terrorism, and the ensuing wars in Afghanistan and Iraq became the all-encompassing focal points. While that relieved pressure on China, the US decision to invade Iraq raised serious concerns in Beijing and elsewhere about the direction of global order under US leadership.

American willingness to attack a sovereign government with the stated goal of changing its regime set a worrisome precedent for authoritarian governments. Worries transformed into something else following the global financial crisis in 2008. Chinese leaders became even more wary of US leadership, with former Vice Premier Wang Qishan telling then-Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson after the financial crisis , “Look at your system, Hank. We aren’t sure we should be learning from you anymore.”

The war in Iraq was especially troubling for Chinese leaders. Few believed that the United States would engage in such a disastrous war over something as idealistic as democracy promotion in the Middle East. The dominant assumption was that the war was about maintaining control of global oil—and using that dominance to prevent China from rising to a peer competitor status. The so-called “ Malacca Dilemma ” became a feature of analysis in China’s strategic landscape: the idea that any power that could control the Strait of Malacca could control oil shipping to China, and therefore its economy. Since then, China has developed the world’s largest navy and invested in ports across the Indian Ocean region through its Maritime Silk Road Initiative . Its defense spending has increased fivefold this century, from $50 billion in 2001 to $270 billion in 2021, making it the second-largest defense spender in the Indo-Pacific region after Japan, and higher than the next thirteen Indo-Pacific countries combined.

Since the Iraq war, the Middle East has become a much greater focus in Chinese foreign policy. In addition to building up its own military, China began discussing security and strategic affairs with Middle East energy suppliers, conducting joint exercises , selling more varied weapons systems , and pursuing a regional presence that increasingly diverges or compete s with US preferences.

Would China’s growing presence in the Middle East have followed the same trajectory had the United States not invaded Iraq? Possibly, although one could argue that the same sense of urgency would not have animated decision makers in the People’s Republic of China.

— Jonathan Fulton is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council and host of the China-MENA podcast. He is also an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. Follow him on Twitter: @jonathandfulton .

The country’s readiness to meet climate challenges

Over the course of the last two decades, Iraq has become one of the five most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change. It has been affected by rising temperatures , insufficient and diminishing rainfall , intensified droughts that reduce access to water , sand and dust storms , and flooding . Iraq’s environmental ministry warns that the country may face dust storms for more than 270 days per year in the next twenty years. While not the sole cause of environmental mismanagement in Iraq, the muhasasa system of power sharing has exacerbated and contributed to a culture of corruption and political patronage that has undermined efforts to protect the environment and to sustainably manage Iraq’s natural resources. Muhasasa is an official system that allocates Iraqi government positions and resources based on ethnic and sectarian identity. It may have been a good temporary compromise to promote stability in the early 2000s, but today it is widely viewed as a harmful legacy of the post-invasion occupation period. In the context of protecting the environment, the muhasasa system has led to a situation where some government officials are appointed to their respective positions without the necessary skills or qualifications to manage resources efficiently or effectively. Forced ethnosectarian balancing has encouraged natural resource misuse for political or personal gain to the immediate detriment of average Iraqis. While muhasasa was intended to promote political stability and prevent marginalization of minority groups, in practice it has contributed to a culture of corruption and nepotism, and undermined efforts to promote good governance and sustainable development. To address its acute climate challenges, Iraq needs to move away from the sectarian-based power sharing and toward a more inclusive, merit-based system of governance. It must strengthen its environmental regulations, commit itself to sustainable development, and better manage its natural resources for the country and as part of the global effort to mitigate climate change. The international community has a role to play here through supporting technical assistance, capacity building, and providing financial resources to help address these concerns along the way.

— Masoud Mostajabi is an associate director of the Middle East programs at the Atlantic Council.

Iran’s regional footprint

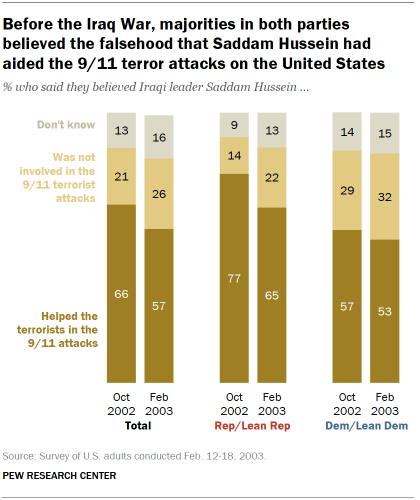

From the outset of the invasion of Iraq, the United States’ decision was built on several dubious premises that the administration masterfully overhyped to build support for its aspirations of removing Saddam Hussein by force. The last two decades have tragically shown the consequences of this decision—with high costs of blood and treasure and a serious blow to American credibility. But from a strategic standpoint, one particular miscalculation continues to create blowbacks to US regional security interests: top US policymakers willfully ignored the need for an adequate nation-rebuilding strategy, leaving a power vacuum that an expansionist Iran could fill.

With the removal of the Baathist regime, Iran finally saw the defeat of a rival it could not best after eight years of one of the region’s bloodiest wars. This cleared the path to influence Iraqi Shia leaders who had long relied on the Islamic theocracy next door for support. Even as some Shia learning centers in Najaf and Karbala challenged (once again) Qom, new opportunities of influence that never existed before opened up for Iran.

By infiltrating Iraq’s political institutions through appointed officials submissive to its regime’s wishes, Iran succeeded in two goals: deterring future threats of Iraqi hostilities and preventing the United States from using Iraqi territories as a platform to invade Iran. Through its Islamic Revolution Guards Corps Qods Force, Iran trained and supplied several militia groups that later officially penetrated Iraq’s security architecture through forces called Popular Mobilization Units, which have repeatedly carried out anti-American attacks. Nevertheless, those groups would eventually prove valuable to the United States in the fight against the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS)—yet even then Iran succeeded in appearing as the protector of Iraq’s sovereignty by immediately equipping the Popular Mobilization Units, unlike the delayed US response that arrived months later.

Regionally, Iran’s military leverage and political allies inside Iraq provided it with a strategic ground link to its network in Syria and Lebanon, where the Qods Force ultimately shifted the political power dynamics to Iran’s advantage, especially as they crucially strengthened engagement in recruiting volunteers to support Bashar al-Assad’s fighters in Syria. Through the land bridge that connects Iran to the Bekaa Valley, Iran has helped spread its weapons-trafficking and money-laundering capabilities while reinforcing an abusive dictatorship in Syria and a crippled state in Lebanon.

Twenty years ago, the United States went to liberate Iraq from its oppressive dictatorship. What it left behind is a void in governance and an alternative system that fell far short of what the United States wanted for Iraq. Meanwhile, the Iranian regime continues to base its identity on anti-Americanism while it gets closer to its political and ideological ambitions. With US sanctions having so far failed to halt Iran’s network of militia training and smuggling—and the attempt to revive the nuclear deal stalled, despite being the main focus of US Iran policy—the question remains: How long will the United States tolerate Iran’s regional ascendancy before it intensifies its efforts toward restraining it?

— Nour Dabboussi is a program assistant to the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East programs.

How governments counter terrorist financing

Without the experience of the war in Iraq, US and transatlantic economic statecraft would be less agile and less able to prevent terrorist financing. However, more work and continued international commitment is needed to ensure Iraq and its neighbors are able to strengthen and enforce their anti-money-laundering regimes to protect their economies from corruption and deny terrorists and other illicit actors from abusing the global financial system to raise, use, and move funds for their operations.

The tools of economic statecraft, including but not limited to sanctions, export controls, and controlling access to currency, became critical to US national security in the wake of 9/11 and the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. Sanctions and other forms of economic pressure had been applied against the government of Iraq and illicit actors prior to 2003. However, economic pressure and the use of financial intelligence to combat terrorist financing became increasingly sophisticated as the war progressed. Since 2001, the State Department and Treasury have designated more than 500 individuals and entities for financially supporting terrorism in Iraq. Following the money and figuring out how terrorist networks raised, used, and moved funds was a critical aspect in understanding how they operated in Iraq and across the region. Information on terrorist financial networks and facilitators helped identify vulnerabilities for disruption, limiting their ability to fund and carry out terrorist attacks, procure weapons, pay salaries for fighters, and recruit.

Sanctioning the terrorist groups and financial facilitators operating in Iraq and across the region disrupted the groups’ financial flows and operational capabilities while protecting the US and global financial systems from abuse. Targets included al-Qaeda and the Islamic State group, among others. For example, the US Treasury recently sanctioned an Iraqi bank moving millions of dollars from the Revolutionary Guard Corps to Hezbollah , preventing terrorists from abusing the international financial system.

Notably, the fight against terrorist financing set in motion the expansion of the Department of the Treasury’s sanctions programs and helped the US government refine its sanctions framework and enforcement authorities and their broad application.

Equally important, the US government’s efforts and experience in countering the financing of terrorism increased engagement and coordination with foreign partners to protect the global financial system from abuse by illicit actors. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the inter-governmental body responsible for setting international anti-money-laundering and counter-terrorist financing standards, strengthened and revised its standards, recommendations, and red flags to account for what the international community learned from the experience of combatting terrorist financing in Iraq. The United States and partner nations provided, and continue to provide, training and resources to build Iraq’s and its neighbors’ capabilities to meet FATF standards and address terrorist financing and money laundering issues domestically.

— Kim Donovan is the director of the Economic Statecraft Initiative within the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.

— Maia Nikoladze is an assistant director at the Economic Statecraft Initiative within the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.

The United States

Perhaps no event since the end of the Cold War shaped American politics more than the invasion of Iraq. It is fair to say that without the Iraq war neither Donald Trump nor Barack Obama would likely have been president.

Weirdly, the invasion of Iraq in 2003 is still almost a forbidden topic in GOP foreign policy circles. After the Bush years, a kind of collective-guilt omerta about the Iraq war took hold among Republicans. It was as if US-Iraqi history had started in 2005, or 2006, with Democrats and a few Republicans baying for a needed defeat. It never came. The 2007 surge, as David Petraeus’s counterinsurgency strategy came to be known, was the gutsiest political call by an American leader in my lifetime.

It happened also to be right when very little else about the war was: There were, of course, no weapons of mass destruction found. Iran did expand its power, massively. Iraq did not offer an example of democracy to the region: rather, it horrified the region. It became linked to al-Qaeda only after the invasion. The White House refused to take the insurgency seriously until it was very serious. Iraq pulled attention away from Afghanistan. And of course there were 4,431 Americans killed.

By 2016, the narrative favored by Republicans had become that the execution of the war was flawed. Paul Bremer, head of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Baghdad, was the villain in this story: But for Bremer’s incomprehensible decision to disband the Iraqi army and institute de-Baathification in early 2003, so the story went, the Iraq war could have succeeded. But in retrospect these decisions were defendable. Bremer was erring on the side of satiating the Shia majority, not the Sunni minority, and trying to reassure them that a decade after they were abandoned in 1991 the United States would deliver them political power. And the one real success of the Iraq war, beginning to end, is that the United States never faced a generalized Shia insurgency.

The other villain was Barack Obama, who played in the sequel. (Obama largely owed his electoral victory to the Iraq war, brilliantly using Hillary Clinton’s vote for the invasion to invalidate her experience and judgment and thus the main argument for her candidacy.) In this version of events, Obama’s precipitous decision to withdraw troops from Iraq in 2011 contributed to the country’s near-collapse three years later under the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS). This was basically accurate. The withdrawal of US forces eliminated a key political counterweight from Iraq, and the main incentive for then-Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki to hedge his sectarianism and friendliness with Iran. This accelerated political support for Sunni rejectionist movements like ISIS.

Both the Bremer narrative and the Obama narrative allowed George Bush’s Republican party to avoid revisiting the core questions of American power: intervention, exceptionalism, and its limits—precisely the same questions that had featured prominently in the 2006 and 2008 elections.

This was the broken market that Donald Trump exploited: that Republican voters’ views on Iraq after 2008 looked much like Democratic voters’, but the Republican establishment’s views did not. And it was no accident, in the 2016 presidential primaries, that the two candidates most willing to criticize the interventionism of the 2000s, Trump and Ted Cruz, were the ones who did best.

This debate remains critical. More than any other decision, Bush’s war created the contemporary Middle East. Above all that includes the unprecedented regional dominance of Iran, the power of the Arab Shia, and the constraints on American power in buttressing its traditional allies. That imbalance, combined with a decade-long sense that America is leaving the region and wants no more conflict, has led Sunni Arab states to look for their security in other places.

Especially in the wake of Russia’s war against Ukraine, which if anything has sharpened foreign policy divisions, the Republican party and the United States need a dialectic, not a purge; a discussion, not a proscription; and a reasonable synthesis of the lessons of Iraq. People want to vote for restraint and realism, as much as or more than they want to vote and pay for interventionism and idealism. Was the Iraq War a mistake? Let us start this debate there, and produce something better.

— Andrew L. Peek is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He was previously the senior director for European and Russian affairs at the National Security Council and the deputy assistant secretary for Iran and Iraq at the US Department of State’s Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs.

Andrew Peek on the historical context of the 2003 invasion

US foreign policy

The US decision to invade Iraq twenty years ago was, to use the words of Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, a wily French statesman and diplomat of the Napoleonic era, “worse than a crime; it’s a mistake.”

While Saddam Hussein was a monster, and had ignored numerous United Nation-mandated commitments, the US-led effort in 2003 to topple him as president of Iraq was strategically unnecessary. It became the center of a failed mission in nation-building—one that has proved disastrous for US interests in the greater Middle East and beyond.

Iraq was at the center, but it was only one of four failed American interventions in the region. The others were Afghanistan, Libya, and, to a lesser extent, Syria. The operation to take down the Taliban was fast and efficient, but consolidation of a post-Taliban Afghanistan never occurred. Part of the reason for that was the United States’ war of choice in Iraq, which began less than eighteen months after Afghanistan. That sucked up most of the resources and attention for the rest of that decade. But the other reason for US failure in Afghanistan was that we were beguiled by the same siren song that misled us in Iraq: that we could overcome centuries of history and culture and create a stable society at least somewhat closer to US values. Failure on such a scale is not good for the prestige and influence of a superpower.

But that is not the end of it. There is also the domestic side. The misadventures in the greater Middle East were a failure not just of the US government but of the US foreign policy elite. It was a bipartisan affair. Neoconservative thinking dominated the Republican Party throughout the aughts, while liberal interventionism prevailed in the Democratic Party. They were all in for the utopian policies in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria.

While the failures in the greater Middle East were widely understood even before the unnecessarily embarrassing 2021 departure from Afghanistan, there has never been a public reckoning. There was nothing like the Church Committee, which in the mid-1970s shined a very harsh light on US failures in Southeast Asia. Few prominent thinkers or officials have publicly acknowledged their failed policy choices. And the same figures who led us into those debacles are still widely quoted on all major foreign policy matters.

This has had the consequence in the United States of providing ground for the growth of neoisolationist thinking. In running for the presidency in 2016, Donald Trump was not wrong in pointing out the failures of elites in both parties in conducting foreign policy in the greater Middle East. Since then, populists on the right have used this insight to undermine the credibility of foreign policy experts. And like generals fighting the last war, they have applied their “insight” from the Middle East to the latest challenges to US interests, such as Moscow’s war on Ukraine.

In this reading, US support for Ukraine is comparable to US interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan and will result in failure. There is no analysis—simply dismissal—of the dangers that Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine poses to US security and economic prosperity. No recognition that, as Putin has stated numerous times, he wants to restore Kremlin political control over all the states that used to make up the Soviet Union—which includes NATO and European Union (EU) member states. In other words, he seeks to undermine NATO and the EU.

Furthermore, there’s no understanding that despite the presence of American troops, the United States’ local allies in Iraq and Afghanistan could not win—but without one NATO soldier on the battlefield, Ukraine is fighting Russia to a standstill. Indeed, Ukraine has destroyed between 30 percent and 50 percent of Moscow’s conventional military capability. These analogies with the Iraq war ignore the reality that if Putin takes control of Ukraine, the United States will likely spend far more in financial resources and perhaps American lives in defending its NATO allies.

These failures of understanding are not simply or mainly a consequence of US errors in the Middle East. Utopian thinking in the United States and especially Europe was a natural consequence of the absence of great-power war since 1945. Especially since the fall of the Soviet Union, people on both sides of the Atlantic got comfortable with the notion that Russia was no longer an adversary. And isolationism also has a long pedigree in US society. So it would be vastly oversimplifying to blame the confusion of today’s neoisolationists exclusively on US failures in the Middle East. But the strong US response to the challenge of a hostile Soviet Union was possible because a bipartisan approach on containment was endorsed by leaders of both parties. After the United States’ misadventures in Iraq, such endorsements carry less weight today. In US foreign policy as elsewhere, we still do not know what the ultimate impact of the decision to invade Iraq will be.

— John Herbst’s 31-year career in the US Foreign Service included time as US ambassador to Uzbekistan, other service in and with post-Soviet states, and his appointment as US ambassador to Ukraine from 2003 to 2006.

William F. Wechsler on the future of Iraq

A reconciliation commission to rebuild national unity

One of the most devastating shortcomings of the 2003 Iraq invasion was the dismantlement of state institutions and the weakening of the Baghdad central government. That structural vacuum of power and services forced Iraqis back into tribal, religious, and ethnic allegiances, contributing to the nation-state’s fragmentation and exacerbating divisive sectarian discourses and intercommunity tensions. A quota-based constitutional system only served to institutionalize and legitimize the ethnosectarian distribution of power.

Conflicting groups grew further apart over the past two decades and became more motivated by accumulating political positions, hefty oil incomes, and territorial and symbolic gains rather than collectively seeking to rebuild their balkanized nation. Iraqi youth, on the other hand—who campaigned in the name of “We Want a Homeland” [نريد_وطن#] during the 2019 Tishreen (October) protests—seem to have understood what political elites might be missing: the necessity for national reconciliation and memorialization.

The bombing of the al-Askari shrine in Samarra in 2006 unleashed the chaos trapped inside Pandora’s box and resulted in violent Sunni-Shia confrontations, which pushed the country to the brink of civil war. Today, political elites, aware of the fragility and precariousness of the political consensus, pretend the time of friction is over. My firsthand work in Iraqi prisons and camps, and the research projects I led in the country’s conflict zones off the beaten path, such as west of the Euphrates, in Zubair, and in rural areas in the Makhoul Basin, prove the absolute contrary.

A flagrant example of the sectarian ticking bomb that persists in Iraq is the mismanagement of the Sunni populations in the aftermath of the war against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS). Many pretended that ISIS fighters came from some fictional foreign entity and refused to face the fact that most of them, including their leader , were Iraqi-born and raised, which I observed as an eyewitness working with the International Committee of the Red Cross during the ISIS war in Nineveh and Salahuddin. Many people who were accomplices of the atrocities even engaged in rewriting the narrative altogether after 2017 in the name of national unity.

A number of Sunni populations in Iraq were mystified by their sudden loss of power with the toppling of Saddam Hussein and were in disbelief that the Shia they stigmatized as shrouguis — literally, “easterners,” a derogatory reference used by Sunni elites to refer to Shia Iraqis from the southeast—became the new lords of the land. Instead of engaging in meaningful mediation and reconciliation to work through these social changes, the majority parties preferred to bury their heads in the sand. This tendency led them to allow militia groups to displace and isolate the Sunni inhabitants of a key city like Samarra, to submerge under water the citizens of northern Kirkuk and Salaheddin, or to conceal the evidence incriminating Tikrit Sunnis during the Speicher massacre , in which ISIS fighters killed more than a thousand Iraqi military cadets, most of them Shia.

These are not isolated examples in a chaotic political and constitutional system in which many communities feel persistently misunderstood, including Kurds, Assyrians, Mandaeans, Baha’is, Afro-Iraqis, Turkmen—and even the Shia themselves. The only possible and plausible pathway for the country to be one again in the next twenty years is to engage in an excruciating but indispensable reconciliation process, through which responsibilities are determined, dignity is restored, and justice is served.

— Sarah Zaaimi is the deputy director for communications at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center & Middle East programs.

A new constitution

Iraq needs a new constitution. A good constitution spells out the framework and structure of government. It provides essential checks and balances to prevent dictators from coming to power. It helps protect the people’s rights. It has measures to prevent gridlock or the collapse of a functioning government.

Judged by these standards, the 2005 Iraqi constitution is only a partial success.

However, complaints have built up since 2005: over the muhasasa system under which the established political parties divide up ministerial appointments; over the failure of Iraq’s government or other institutions to deliver basic services like electricity and water; over perceptions of excessive Iranian meddling in Iraq’s politics; and over the inability of the government to provide meaningful employment for millions of young Iraqis—or to foster a private sector capable of doing so. These grievances came to a head in the 2019 Tishreen protests in which more than 600 Iraqis died.

The United States invaded Iraq in 2003 in part to bring democracy to Iraq, so it is ironic that Iraq’s 2005 constitution was the product of mostly Iraqi political forces unleashed by the failure of the United States to ensure a democratic transition. It was expected that the Kurdish political parties, which had worked closely with the United States for years, would insist upon a federal republic to ensure their autonomy from a central government whose long-term character and leanings in 2005 were far from settled. Beyond this, however, the small number of Americans actually involved in advising the key Iraqi players in the constitutional process— in the room where it happened —actually had relatively little experience in constitutional mechanics or modern comparative constitutional practice. The American sins of commission during the first two years after Iraq’s liberation were replaced by sins of omission during the crucial months of negotiation of the 2005 constitution.

Genuine constitutional reform in Iraq is not likely to be accomplished directly through the parliament, given the interests of Iraq’s political parties and the parliament’s need to focus on legislative responsibilities. Instead, Iraqi civil society—including scholars, lawyers, religious and business leaders, and retired government officials and jurists—should initiate serious discussions about constitutional reform. Many of these voices were not heard when the 2005 constitution was adopted. Their effort can be far more open and transparent than the process was in 2005.

Foreign governments should have a minimal role, limited to supporting and encouraging Iraqi-led efforts, without trying to broker a particular outcome. International foundations, institutes, universities, and think tanks can offer outside expertise, particularly in comparative constitutional law and other kinds of technical assistance. But the overall effort needs to be Iraqi-led, with input from a broad spectrum of Iraqi voices.

While civil society discussions in Iraq could begin with considering amendments to the 2005 constitution, US experience may be relevant. The US Constitutional Convention convened in May 1787 to consider amendments to the Articles of Confederation decided to completely redesign the government, resulting in a Constitution that, with amendments, has been in force in the United States for more than 230 years. Sometimes it’s better to start over.

Iraq’s path to constitutional reform is not clear today, but there is a path nevertheless. Incremental reform is possible, but reform on a larger scale may achieve a more lasting result. The more promising outcome could be for a slate of candidates to run for office with the elements of the new constitution as their platform. A reform slate is not likely to gain an absolute majority, but if its base of support is broad enough, it may be able to gain support in a new parliament needed to send a revised constitution to the Iraqi people for their approval. A new constitution, done right, could propel Iraq towards a better future.

— Thomas S. Warrick led the State Department’s “Future of Iraq” project from 2002 to 2003, served in both Baghdad and Washington, and was director (acting) for Iraq political affairs from July 2006 to July 2007. He is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Thomas S. Warrick on the need for Iraqi-led constitutional reform

An economy diversified away from oil

The post-2003 political order, based on the muhasasa system of sectarian apportionment, came with the promise of a complete break with the past. The 2005 constitution , drafted by the new order, promised: “The State shall guarantee the reform of the Iraqi economy in accordance with modern economic principles to insure the full investment of its resources, diversification of its sources, and the encouragement and development of the private sector.”

As with other bold promises made, the economic promise was broken as soon as the constitution came into effect, as the political order pursued a decentralized and multiheaded evolution of the prior economic model, and persistently expanded the patrimonial role of the state as a redistributor of the country’s oil wealth in exchange for social acquiescence to its rule.

Over the last twenty years the economy developed significant structural imbalances, and was increasingly bedeviled by fundamental contradictions. Essentially, it was dependent on government spending directly through its provisioning of goods and services as well as public services, and indirectly on the spending of public-sector employees. However, this spending was almost entirely dependent on volatile oil revenues that the government had no control over; yet the spending was premised on ever-increasing oil prices.

The political order had the opportunity to correct course and honor the original promise during three major economic and financial crises, each more severe than the last and all a consequence of an oil-price crash: in 2007 to 2009, due to the global financial crisis; in 2014 to 2017, due to the conflict with the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham; and in 2020, due to the emergence of COVID-19. Yet, paradoxically, the political order doubled down on the policies that led to these crises as soon as oil prices recovered.

On the eve of the twentieth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq, the political order—buoyed by the bounty of high, yet unsustainable, oil prices—is planning a budget that is expected to be the largest ever since 2003 , to seek legitimacy from an increasingly alienated public. These plans will only deepen the economy’s structural imbalance and its fundamental contradictions, and as such could likely lead to even greater public alienation if an oil-price crash triggers yet another economic and financial crisis. Even if oil prices were to stay high, however, the country’s demographic pressures will in time create the conditions for a deeper rolling crisis.

— Ahmed Tabaqchali is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs. An experienced capital markets professional, he is chief strategist of the AFC Iraq Fund.

Andrew Peek on the current state of Iraq and the US-Iraq relationship

An inclusive vision, representative of all its people

One of the enduring legacies of the 2003 invasion has been its deleterious effect on the many diverse ethnic and religious minority communities that make up the social fabric of Iraq. Yet it is that diversity and rich heritage that could now unlock a brighter future for the nation, if the political system can recognize and represent it.

Marginalized by an institutionally inscribed political system and few representative seats in parliament, Iraq’s minority communities have found themselves peripheralized by the state—and in the imaginations of the country’s future. Many have emigrated and now reside in diaspora, changing the ethnic and religious heterogeneity of Iraq.

Calculating the cultural toll of war goes beyond the destruction of shrines and artifacts, and the looting of museums and buildings: One of the biggest social and cultural losses for Iraq has been the exclusion of minority communities from the nation-building processes. This is a tragic state of affairs for Iraq, whose uniqueness, strength, and richness stems from its ancient histories and cultures, its religious, artistic, and musical traditions, and the languages that have contributed to its heritage and development. That heritage deserves to be protected and celebrated.

Until the day the muhasasa system is dismantled, and a new Iraq built on meritocracy can thrive, minority communities must be safeguarded and included in Iraq’s future. Yet, this can only be achieved through the protection of minorities’ rights in Iraq’s political life, and genuine and concerted effort to increase parliamentary seats and legal representation of minorities. Investment in areas destroyed by terrorism and conflict, more reparations for communities whose livelihoods and homes have been ruined, and more boots on the ground to protect communities and religious shrines should be a priority.

Twenty years of destruction, corruption, violence, and the subsequent emigration of many communities cannot be erased. Yet the twentieth anniversary of Iraq’s occupation ought to serve as a point of reflection for the kind of Iraq that Iraqis want now. There is certainly much hope in a new generation of Iraqis calling for new national visions, an end to muhasasa , more civil rights, and expanding economic opportunities.

Yet all of Iraq’s communities must be part of this conversation. A more inclusive Iraq that applauds its diversity and takes pride in difference could be the driving force needed to unify the nation.

— Oula Kadhum , a former nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, is a postdoctoral research fellow at Lunds University in Sweden and a fellow of international migration at the London School of Economics and Political Science in the United Kingdom.

Oula Kadhum on the reforms needed to reposition Iraq in the next twenty years

A new US Iraq policy focused on youth and education

As the global community reflects on the twentieth anniversary of the US-led invasion of Iraq and looks to the future, it is time for foreign policy toward Iraq to move beyond its traditional, security-heavy approach.

While security threats persist, including a potential resurgence of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), and should be a priority, US aid to Iraq has historically been ineffective and financially irresponsible. Humanitarian assistance, meanwhile, tends to focus on short-term issues like the response to COVID-19 and assisting displaced individuals. And while such aid can be beneficial, continuing with the traditional avenues of support is not a sustainable solution to rebuild Iraq. The United States and the international community must begin to focus on long-term solutions that address human security, development, infrastructure, education, and the economy. At the center of all these issues are two key variables that must be the focal point of policy: education and the youth population.

A 2019 UNICEF report estimates that a staggering 60 percent of Iraq’s population is under the age of twenty-five. Learning levels and access to education in Iraq remain among the lowest in the region. The great challenges these two facts pose can also be seen as a unique opportunity: to place its large youth population at the epicenter of Iraq’s future through policy that increases the number of educators and trains them, ensures sanitary and competent learning conditions, and increases access to education.

The benefits of a long-term investment in Iraq’s education system and youth population go beyond simply educating its citizens: It would be the first step in unlocking the human potential of Iraq. More education means more qualified professionals; more doctors would increase the quality and access to healthcare, an increase in engineers will ensure that the country’s infrastructure continues to develop, and additional business leaders and entrepreneurs will assist in growing the economy.

To truly rebuild Iraq, the United States and the international community can no longer view the country as only a security issue. Rather, this moment must be seen as an opportunity to empower bright Iraqi youths, who hope to lead in rebuilding their own country—providing them with a fair shot of again being a cradle of civilization.

— Hezha Barzani is a program assistant with the Atlantic Council’s empowerME initiative. Follow him on Twitter @HezhaFB .

Iraq’s Deputy Prime Minister Fuad Hussein reflects on the twentieth anniversary of the invasion

Recommit to the cause of Iraqi freedom

It’s hard to believe that it has been twenty years since the US invasion of Iraq. As I sat waiting to launch my first mission on March 20, the war’s historical significance was not my primary thought. How I found myself flying on the first night of the war in Afghanistan and Iraq was. That thought was accompanied by the tightness in the pit of my stomach that I always got before launching into the unknown.

We didn’t debate the case for the war among ourselves. It has been discussed thoroughly since, and I don’t claim to have any new insight to offer on that topic. We were focused on not letting down our fellow Marines and accomplishing our mission: to remove Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship and replace it with a democracy that would give the people of Iraq the freedom that people everywhere deserve as their birthright.

Did we succeed? We certainly succeeded in rapidly destroying the Baathist regime and its military, the third largest in the world. The answer to the second question is less clear. On my second and third tours in Iraq, I saw the chaos from the al-Qaeda-fueled insurgency in 2005 and 2006 and the dramatic turnaround following the al-Anbar “ Sunni Awakening ” in 2006-2007. From afar, I watched the horrors that the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham inflicted on its people after US troops withdrew without a status-of-forces agreement.

Today, Iraq is rated “not free,” scoring twenty-nine out of one hundred in Freedom House’s Freedom in the World 2022 report . Although not up to Western liberal democracy standards, this is an improvement over 2002, when it received the lowest score possible and was listed as one of the eleven most repressive countries in the world. Moreover, Iraq’s 2022 score is vastly better than most of its neighbors: Iran scored fourteen, Syria scored one, and Afghanistan scored ten.

Despite Afghanistan being widely seen as “the good war” of the two post-9/11 conflicts, where the casus belli was clear, today it is Iraq, and not Afghanistan, that gives me hope that twenty years from now, on the fortieth anniversary, we will see our efforts to promote democracy in Iraq come entirely to fruition. We owe it to the 36,425 Americans killed and wounded there, the thousands of veterans who took their own lives, and the many more still struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder to stay engaged in Iraq and the region to try and make sure that they do.

— Col. John B. Barranco was the 2021-22 Senior US Marine Corps Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. These views are his own and do not represent those of the Department of Defense or Department of the Navy.

Balance confidence and humility

I officially swore into the military at Fort Hamilton, Brooklyn, on April 4, 2003, during the early stages of the US “shock and awe” campaign in Iraq. Having decided to join the Air Force following 9/11, the lengthy administrative process I’d endured to get to this point had been agonizing. I recall going through the in-processing line at Officer Training School on April 9, when an instructor whispered to us: “Coalition forces have taken Baghdad, stay motivated.” The thought that immediately went through my mind was: “I’m going to miss the wars.”

I had made the choice to pursue special operations and still had two years of training ahead of me. At the time, the war in Afghanistan seemed like it was nearing completion, and the swift overthrow of Saddam Hussein in Iraq had me convinced that, by the time I was ready to deploy, there would be no fighting left. Little did I know that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, along with their expansions across the Middle East and Africa, would end up consuming a large majority of my twenty years of service, take the lives of many of my special operations teammates, and impact the health and well-being of a generation of US service members and their families.

It’s impossible to know how the war in Iraq shaped other US endeavors in the region. Did it take our focus from Afghanistan and put us on a path of increased escalation and investment there? Did it set conditions for the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham to take root many years later, setting off another expansive counterterrorism campaign?

More broadly, did it allow adversaries the time and space to study US capabilities and ultimately inform their strategies for malign influence? I often think of this today when I’m asked about what’s going to happen with the Russian war in Ukraine, or how prepared the United States is to defend Taiwan.

The United States needs the confidence to confront global challenges to peace and prosperity, but also the humility to know we get things wrong, and mistakes involving direct military intervention can be catastrophic. Given the escalatory risks associated with the security challenges in the world today, our pursuit of a balance of confidence and humility has never been more important.

— Lt. Col. Justin M. Conelli is the 2022-23 Senior US Air Force fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

William F. Wechsler on the current political discourse around Iraq

Recognize the successes as well as the failures

“Was the invasion of Iraq worth it?”

I’ve spent a great deal of my military and postmilitary career answering questions about Iraq, but this one—from a brigadier general in the audience—caught me off guard. It was 2018, seven years after the formal withdrawal of US forces from Iraq, and I found myself in front of a roomful of Army officers giving a talk on the future of US-Iraq security cooperation. By that time, such talks had become a little frustrating. The fight against the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (aka the Islamic State group) demonstrated that Iraqi forces could rise to the immediate challenge; however, the conditions that led to their unceremonious collapse in 2014 had not much changed. As a result, there remained many questions about the best way to continue the security partnership to prevent future catastrophe.

The question I got that day, however, had little to do with how to partner with Iraqi forces. A co-presenter from Kurdistan jumped in immediately to answer the brigadier general’s question: the US invasion had removed Iraqi Kurdistan’s most significant threat—Saddam Hussein—and had provided opportunities for economic and political development it would not have had otherwise. Sensing a trap, I nonetheless walked right into it. While Iraqi Kurdistan was certainly in a better position, I pointed out that was not consistently so for the rest of Iraq. The US invasion had unleashed a sectarian free-for-all that allowed Sunni extremists, Shia militias, and their Iranian sponsors to fill the vacuum of oppression Saddam’s departure had left. Moreover, this vacuum had empowered Iran to challenge the United States and its partners regionally. So my answer was no, toppling Saddam likely did not outweigh the costs.

In previous years, the questions had been more policy-focused. For example, when I arrived at the Pentagon’s Iraq Intelligence Working Group in August 2002, the first question asked was how Iraq’s diverse ethnic and confessional demographics would affect military operations and enable—or impede—victory. By early 2003, the questions were about the larger effort to construct a new political order. Before long, we were asking how the confluence of Islamist terrorism, sectarian rivalries, and external intervention drove resistance to efforts to reconstruct Iraq.

In 2012, I became the US defense attaché in Baghdad, just after the last US service members withdrew. At first, the question I heard in this capacity was how to continue the reconstruction project with a limited military and civilian presence whose movement was often severely restricted in a sovereign, sometimes uncooperative, Iraq with frequent interference from Iran. Before I left, al-Qaeda had metastasized into the Islamic State group and the question became how to cooperate to prevent the group’s further expansion and liberate the territory it had seized. Meanwhile, Iran’s influence with the Iraqi government continued to grow.

In retrospect, the conditions I described in 2018 were accurate (and still largely hold today), but I wish I had given a more considered response. What I wish I had said was that a better question than “was it worth it” is: what have we learned about past failures to assess future opportunities? A prosperous Iraq that contributes to regional stability was not possible under Saddam. Now Iraq is an effective partner against Islamist extremists, and the Iraqi people, if not always their government, are in a position to push back on Iran in their own way , exposing Tehran for the despotic government it is. Moreover, Iraq’s hosting of discussions between Saudi Arabia and Iran was a catalyst to their recent normalization of relations.

The point is not to rationalize failure. Rather, the question now is: what have we learned from those failures to effectively capitalize on the success we have had, and how can we take advantage of the opportunities the current situation presents?

— C. Anthony Pfaff , PhD, is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Iraq Initiative and a research professor for strategy, the military profession, and ethic at the Strategic Studies Institute of the US Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Tony Pfaff on the future of US-Iraq relations

Remember the price of hubris

For me, the memories of those first days and weeks in Iraq remain quite clear. I remember calling my family from a satellite phone on the tarmac of Baghdad International Airport to let them know I was alive, late night meetings with Iraqi agents in safe houses, wrapping up Iraqi high-value targets, the fear amid firefights and the carnage on streets strewn with dead and mutilated bodies, and a confused Iraqi population that at the time did not know what to make of US forces who claimed to be liberating them from the regime of Saddam Hussein.

Upon arrival in Baghdad in early April, there were few signs of the resistance that would haunt the United States for decades to come. Yes, there were still combat operations underway, but that was against Iraqi military and paramilitary units. So, as we tracked down Iraqi regime targets one by one—members of the famed “ deck of fifty-five cards ” that US Central Command had dreamed up and distributed like we were trading baseball cards—we saw this as part of a new beginning.

Yet soon after, the wheels began to fall off. Orders came from Washington policy officials with absolutely zero substantive Middle East experience both to disband the Iraqi military and purge the future government of Baath party officials, which immediately put tens of thousands of hardened military officers, conscripts, and officials out of work and on the street. The CIA presence on the ground protested, but to no avail. I had never seen Charlie, my station chief, so angry, including face-to-face confrontations with senior figures in the Coalition Provisional Authority. Charlie—the most accomplished Arabist in the CIA’s history—sadly predicted the insurgency that was about to come. If only Washington had listened.

I rarely think of Iraq in terms of big-picture strategy. As a CIA operations officer, I was a surgical instrument of the US government, and I gladly answered the bell when called upon to do so. I am proud to have served with other CIA officers and special operations personnel who performed valiantly. I suppose I can defend the invasion on human rights grounds. It seems we forget that Saddam was one of the great war criminals in history, and Iraq has been freed from his depravity. Yet two numbers are haunting: 4,431, and 31,994. Those are the number of Americans killed and wounded in action, per official Department of Defense statistics.

War is a nasty business, and many times a terrible price is paid for hubris. The casualty figures noted above paint a stark picture of the historic intelligence failure that the analytic assessment that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction was. The CIA in particular suffered a credibility hit that has taken decades to recover from.

— Marc Polymeropoulos , a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, served for twenty-six years at the CIA before retiring in 2019.

Thomas S. Warrick on the lessons to learn from the Iraq War

A nation must think before it acts.

- America and the West

- Middle East

- National Security

- Central Asia

- China & Taiwan

- Expert Commentary

- Intern Corner

- Press Contact

- Upcoming Events

- People, Politics, and Prose

- Briefings, Booktalks, and Conversations

- The Benjamin Franklin Award

- Event and Lecture Archive

- Chain Reaction

- Bear Market Brief

- Baltic Ways

- Report in Short

- Our Mission

- Board of Trustees

- Board of Advisors

- Research Programs

- Audited Financials

- PA Certificate of Charitable Registration

- Become a Partner

- Corporate Partnership Program

What America Learned in Iraq

- March 30, 2023

- Middle East Program

Editor’s Note: FPRI is publishing a collection of essays to mark the twentieth anniversary of the start of the Iraq War. The articles analyze the war’s impact on US influence in the Middle East , America’s global standing , and US democracy promotion efforts . In addition, our authors identify key lessons of Operation Iraqi Freedom , and argue that the inability of American officials to understand Iraqi politics was perhaps the most important intelligence failure of the entire war effort.

This past week, we marked twenty years since the ill-fated disaster that was the US-led invasion of Iraq. Today, we are sharing at FPRI a collection of essays from our senior fellows reflecting on the ways the invasion and occupation reshaped American foreign policy in the region and beyond.

Each of our contributors strikes one particular refrain—the invasion damaged, possibly irreparably, the credibility of the United States to promote its values in the Middle East. As Sean Yom argues , the boosters of the invasion held to a kind of post-Cold War domino theory that believed a transition to democracy in Iraq with American assistance would inexorably iterate itself across the region. Instead, the manifest failures of the war turned this hope into a threat, “democratize, or else we’ll do it for you ,” as Yom puts it.

Fear of the disorder brought about in Iraq certainly played a role in the anxieties of counterrevolutionary forces across the region in the wake of the Arab uprisings of 2011, as Robert D. Kaplan has elaborated recently in the Wall Street Journal . In his reflection today , he notes how fears of this disorder have strongly characterized President Joe Biden’s response to Russia’s similarly misguided, disastrous invasion of Ukraine—a balanced commitment of American support that forgoes grandiose dreams of remaking a whole region’s value systems reflects “an integration of the lessons learned… without overlearning them.” In the mind of the administration, defending Ukrainian sovereignty in the face of Russian aggression may yet prove both the inverse of the US position in Iraq, and its most successful attempt to secure democracy, to boot.

The relative success of America’s current Ukraine policy should raise questions about the role of promoting democratic values and human rights in US foreign policy more generally, and what role they may yet play in a region that’s been so damaged by past efforts in this area. Sarah Bush offers an important note to this end. As the tragic fate of Afghan women following the US withdrawal in 2021 has shown, it remains important to maintain commitments to democracy, human rights, and gender equality in foreign policy even in the midst of a disaster like Iraq. Finding ways to push (re)invigorated autocracies in the region to go beyond the instrumental efforts to expand rights, where possible, will be a key element of a foreign policy that seeks a balance between restraint and values. Bush urges US policymakers to employ a “savvy” approach on rights, rather than throwing them out with the bathwater of military misadventure.

If American values of democracy, freedom, and equality were damaged by the Iraq invasion, so too were American perceptions of its military and industrial capacities to accomplish any of what it set out to do in Iraq in the first place. As Heather Gregg’s contribution reminds us, “the use of the military to change another country’s administration comes with dozens of unforeseen consequences.” Nation-building likely suffered an even more damning fate than democracy promotion, and central to that failure was poor self-assessment in terms of capacity. Recognition of this fact is reflected in the Biden administration’s National Security Strategy that prioritizes building resilience at home.

Sharing insights gained in the process of researching his impending book on the subject, Samuel Helfont elaborates that the failures of assessment were greatest in terms of intelligence—the United States simply did not know, and could not have known, the extent to which Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime was entrenched in the country. Helfont argues that intelligence failure was the prime failure in the invasion, “if [the administration] had not so grossly misunderstood Iraqi politics and society … other American failures would have been a mere footnote in the otherwise inspiring story of Iraq’s liberation from a cruel dictator.”

Reflecting on these pieces, it is clear that domestic investment in intelligence, education, and preparation will play fundamental roles in shaping nuanced responses to future geopolitical challenges. The significant investment of the federal government in training specialists over the last twenty years to focus on Middle Eastern politics and society has in some ways paid dividends we are only beginning to see the fruit of, and just at the moment when funding in these areas is shifting towards Russian and Chinese concerns. While articulating a Middle East policy that both prioritizes American interests and supports the basic dignity of the people of the region along with their basic human rights and desires for democracy is and will continue to be a difficult challenge, it is clear to me when compared with where the foreign policy establishment, Congress, and the general voting public were twenty years ago, America is better prepared to act with nuanced restraint in the region. One hopes that refining and learning these lessons in the future won’t come at the cost of millions of ruined lives.

Hegemony, Democracy, and the Legacy of the Iraq War

By Sean Yom

The Iraq War destroyed America’s credibility as a promoter of democracy and liberalism in the Middle East. Revolutionary uprisings for democratic change continue to roil the Middle East, but none desire official sponsorship or support from the United States given its bloodstained legacy in Iraq.

Read the full essay here.

Iraq: Some Reflections

By Robert D. Kaplan

Iraq was a bloodier war than supposed, when you consider the deaths of civilian contractors as well as regular troops. Despite the suffering caused by the war, Iraq was a far-flung imperial-like adventure gone awry, which will have a limited effect on American power projection going forward.

Democracy Promotion After the Iraq War

By Sarah Bush

The Iraq War has justifiably left Americans skeptical about democracy promotion. Despite its flaws, US democracy promotion is still needed to advance political rights globally.

Operation Iraqi Freedom: Learning Lessons from a Lost War

By Heather S. Gregg

American-led efforts to state and nation-build in Iraq all but failed, resulting in the deaths of 4,431 US troops, hundreds of thousands of Iraqi fatalities, and mixed-at-best results in creating a viable state. Despite these failed efforts in Iraq, the United States will most likely need to work with allies, partners, and the Ukrainian people to reconstruct their country in the wake of Russia ’ s war against Ukraine. Therefore, learning lessons from the war in Iraq is critical for future efforts at state stabilization.

Read the full essay here.

How America Misunderstood Iraqi Politics and Lost the War

By Samuel Helfont

American war planners’ failure to understand Iraqi politics and society was their most important intelligence failure. The violence in Iraq after the American invasion in 2003 resulted from a political void that Americans failed to anticipate.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.

Image: Defense Department (Photo by Master Sgt. Cecilio Ricardo)

You May Also be Interested in

Helping put sudan’s democratic transition back on track.

In October 2021, Sudan’s civilian government was overthrown in a military coup. The coup marked the conclusion of the...

Filling the Geopolitical Void in Central Asia

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan: The Poorest Countries in Central Asia Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are probably the most dependent on Russia...

The Baltics Predicted the Suspension of the Ukraine Grain Deal — and Contributed to its Resumption

The Ukraine grain deal, formally known as the Black Sea Grain Initiative, is a joint agreement by Russia, Ukraine,...

Misleading Analogies and Historical Thinking: The War in Iraq as a Case Study

Robert Shaffer | Jan 1, 2009

Students come into our history classes well versed in the mantra that “those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it,” that history is “useful” in teaching lessons for today. Whether they truly believe this idea is a separate question, and many of us devote a lot of energy trying to make our lectures, discussion questions, and reading assignments “relevant” to the present. But the quest for “relevance” has its own pitfalls, in the overly simplistic analogies that students—and policymakers—make between past and present. Indeed, one of the textbooks that I use when I teach “Theory and Practice of History,” a required course for history BA majors at my university, states boldly in its opening chapter: “Many who believe the proposition that history is relevant to an understanding of the present often go too far in their claims. Nothing is easier to abuse than the historical analogy or parallel.” Authors Conal Furay and Michael Salevouris want students to understand instead that “[g]ood history, on the other hand, can expose the inapplicability of many inaccurate, misleading analogies.” 1

For the past five years, I have used a brief article, “Lessons from Japan about War’s Aftermath,” an op-ed piece published in October 2002 by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian John Dower, to help students see the practical—and even tragic—consequences of applying simplistic and misleading “lessons of the past” to current events and policies. 2 I have used the article not only in “Theory and Practice of History,” but also in my classes on U.S. diplomatic history, U.S. military history, and others. I ask students to read and discuss the article on the first or second day of class, as its main points are easily accessible and get students talking, and it provides a wonderful opportunity for students to grapple with the contested nature of the meaning of history and to see how a respected historian used his expertise to try to affect current policymaking.

Dower, the preeminent American historian of postwar Japan and an indispensable authority on U.S.-Japanese relations, responded in his essay to those in and close to the Bush Administration who, in building their case for war against Iraq, put forward the notion that, after an easy military victory over Saddam Hussein’s government, the United States would be able to guide Iraq toward a peaceful and democratic reconstruction along the lines of the post–World War II recovery of Japan. As his essay was a brief, newspaper op-ed, Dower did not provide footnotes or specific references, but news reports on October 11—the day after Congress had voted to give the president the power to initiate war—had indicated that the White House was “developing a detailed plan, modeled on the postwar occupation of Japan, to install an American-led military government in Iraq if the United States topples Saddam Hussein.” Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institution, who favored the invasion, reported on these plans the following week, and added that the “labor-intensive tasks” of the occupation—by which he meant the stationing in Iraq of 100,000 American or other foreign troops—should be completed within a year or two. 3

Dower called “the occupation of defeated Japan … a remarkable success,” creating a viable democracy and ending militarism, despite the predictions of many in 1945 that “the Japanese people [were] culturally incapable of self-government.” Nevertheless, he continued, “most of the factors that contributed to the success of nation-building in Japan would be absent in an Iraq militarily defeated by the United States.” Dower then went through about a dozen of the differences between Japan after World War II and what he anticipated the situation would be in Iraq after a prospective war with the United States. A few examples will suffice. While the U.S. retained Emperor Hirohito in office, and he “gave his significant personal endorsement to the conquerors,” nothing similar could occur in Iraq. American planning for occupation in Japan had been ongoing since 1942, and was relatively popular in Japan because it reflected New Deal goals of land reform and encouragement of trade unions; nothing similar could be imagined in a hastily planned occupation of Iraq by the Bush administration. While not minimizing competing political allegiances in Japan, Dower noted that “Japan was spared the religious, ethnic, regional and tribal animosities that are likely to erupt in a post-war Iraq.” Japan’s position as an island shielded it from nations that might resent American occupation or who would wish to intervene for other reasons, while Iraq “shares borders with apprehensive and potentially intrusive neighbors.” Dower concluded strongly: “While occupied Japan provides no model for a postwar Iraq, it does provide a clear warning,” as even in Japan reconstruction was difficult. “To rush to war without seriously imagining all its consequences … is not realism but a terrible hubris.”

Since one goal in having students read Dower’s essay at the beginning of the semester is to encourage them to think about how historians construct an argument, I generally let students confer among themselves for a few minutes to address the following points, working from summary to analysis to evaluation:

- Summarize the “historical” part of Dower’s article about Japan.

- Summarize Dower’s analysis of recent Iraq.

- How does Dower “use” history for an analysis of the present?

- How does Dower criticize the use of history by others?

- Is Dower’s essay convincing, or can criticisms be raised about his argument?

- Why is the date of the article important in assessing its significance?

Students readily identify some of the key points, and the brevity, clarity, and sharp focus of Dower’s essay make it both compelling and appropriate for classroom use. Most students recognize that Dower’s predictions for Iraq have come to pass, and they appreciate that a skilled historian paying attention to specific historical similarities and differences was able to develop such an accurate forecast. Criticisms, of course, have been raised by students, especially about whether the argument about the difficulties of transforming Iraq outweighed the need to rid the world of Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship. One of the most perceptive comments by a student came the very first time I used the article, in a diplomatic history class just a few days after it was published, and before the war began. This young lady—who was herself skeptical about the drive to war—noted that Dower acknowledged that many had believed that the occupation of Japan would not lead to the desired results, and so perhaps circumstances in Iraq would similarly surprise the analysts.