An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.12(2); 2020 Feb

Violence Depicted in Superhero-Based Films Stratified by Protagonist/Antagonist and Gender

John n muller.

1 Emergency Medicine, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, USA

Annie Moroco

Justin loloi.

2 Internal Medicine, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, USA

Austin Portolese

Bryan h wakefield.

3 Chemistry, Coastal Carolina University, Myrtle Beach, USA

Tonya S King

4 Epidemiology and Public Health, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, USA

Robert Olympia

5 Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, USA

The objective of this study was to describe and quantify acts of violence depicted in a select number of superhero-based films, further stratified by protagonist/antagonist characters and gender. A total of 10 superhero-based films released in 2015-2016 were analyzed by five independent reviewers. The average number of acts of violence associated with protagonist and antagonist characters for all included films was 22.7 and 17.5 mean events per hour, respectively (p=0.019). The average number of acts of violence associated with male and female characters for all included films was 33.4 and 6.5 mean events per hour, respectively (p<0.001). The most common acts of violence for all major characters were “fighting”, “use of a lethal weapon”, “bullying/intimidation/torture”, “destruction of property”, and “murder” (14.9, 11.4, 3.5, 3.4, and 2.4 mean events per hour, respectively). Based on our sample of superhero-based films, acts of violence were associated more with protagonist characters and male characters.

Introduction

Superhero-based films have become incredibly popular with both children and adults. Since 2000, there have been more than 100 films with superheroes depicted, grossing more than 23 billion dollars worldwide [ 1 ]. Despite this increase in popularity, superhero-based films represent a genre that frequently portrays violence. Published studies examining the effect of violence in the media has led the American Academy of Pediatrics to issue a policy statement, concluding that exposure to violence in the media offers a significant health risk to children that may result in aggression, bullying, antisocial attitudes, and sleep disturbances [ 2 - 6 ]. Furthermore, the Motion Picture Association of America’s film rating system ( www.mpaa.org ) does not accurately predict the frequency of violence in each rating category, and parents often find the various media rating systems difficult to use [ 7 ]. Therefore, children and adolescents may be viewing films deemed inappropriate for them based on their age.

Conversely, superheroes themselves are typically viewed as good and altruistic people that serve as role models for many children. Their origin stories often depict disadvantaged and humble beginnings, making them likable and relatable characters. In an analysis of 20 superheroes’ origin stories, 86% were orphaned or abandoned, 49% had at least one parent murdered, and 29% were bullied; this may promote resilience in vulnerable children [ 8 ]. Additional research has shown that superhero storylines may promote prosocial behavior in autistic children and encourage healthy eating habits [ 9 - 10 ].

In a recently published study examining positive and negative themes depicted in a selected number of superhero-based films, the authors concluded that the prevalence of negative themes, especially acts of violence, outweighed positive themes [ 11 ]. These acts of violence often included physical altercations, use of guns/knives/lethal weapons, bullying/intimidation/torture, murder, and demonstrating excessive anger. However, to the authors’ knowledge, there have been no published studies examining whether violence depicted in a superhero-based film was associated with protagonist or antagonist characters, or associated with male or female characters. Superheroes depicted in film may be viewed by children and adolescents as “the good guy”, and therefore these viewers may be influenced by their portrayal of risk-taking behaviors and acts of violence. Similarly, young girls, in particular, may be influenced by the behaviors of female superhero characters depicted in the film. The objective of this study was to describe and quantify acts of violence depicted in a selected number of superhero-based films, further stratified by protagonist/antagonist characters and gender.

Materials and methods

We conducted a content analysis study examining acts of violence depicted in superhero-based films released during 2015 and 2016, further stratified by major protagonist/antagonist and male/female characters. Ten films included in the analysis were identified on a popular online comprehensive film database ( boxofficemojo.com ), limited by genre (“superhero”) and date of release (“2015” or “2016”), and chosen based on the highest lifetime gross profit as listed on July 1, 2017 (Table (Table1). 1 ). Films were excluded if they were not super-hero based. The exclusion was not based on assigned film rating by the Motion Picture Association of American film rating system ( www.mpaa.org ), and thus included films assigned a PG-13 (parents strongly cautioned, some material may be inappropriate for children under 13) and R (restricted - under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian) rating.

USD: United States dollar; TMNT: teenage mutant Ninja turtles; PG-13: Parents strongly cautioned, some material may be inappropriate for children under 13; R: restricted - under 17 requires accompanying parent or adult guardian

Each of ten included films was viewed in its entirety by the study investigators prior to data collection. Consensus was implemented to determine which protagonist and antagonist characters played a significant role in the storyline of the film, and thus would be considered a major protagonist and antagonist character. Data analysis was performed on 66 major protagonist and 44 major antagonist characters, and 88 male and 22 female major characters. Definitions for acts of violence were created by the study investigators prior to data collection (Table (Table2 2 ).

A data collection instrument, developed by the study investigators, allowed the five viewers (John Muller, Annie Moroco, Justin Loloi, Austin Portolese, Bryan Wakefield) to document acts of violence performed by major protagonist and antagonist characters. Each of the five viewers watched and coded every film independently. Certain coding guidelines were decided prior to viewing the study films. For example, when coding an extended fight sequence with several major characters involved simultaneously, each contained battle involving at least two opponents was coded as one act of violence event (“fighting”), while each use of a lethal weapon (“Use of lethal weapon”) or each death (“Murder” or “Mass murder”, depending on number of deaths) was coded individually per event and per character during that given fight sequence. Acts of violence performed in the film and then later referenced were coded only at the initial encounter.

After coding, data collection instruments were collected by the primary investigator (John Muller) and the data were entered into Excel. Repeated measures Poisson regression was used to determine the overall rates of acts of violence per hour for major protagonist and antagonist characters, as well as male and female characters. These event rates were reported with corresponding 95% confidence intervals and compared between rating types with adjustment for variability among reviewers. Individual types of violence were also evaluated for protagonists, antagonists, males, and females in the same type of repeated measures Poisson regression models. The most common acts of violence were identified for each of the films separately.

The Institutional Review Board at the Pennsylvania State Hershey Medical Center deemed the study exempt.

Table Table3 3 describes acts of violence for all included films, as well as stratified by major protagonist/antagonist and male/female (Table (Table3). 3 ). The overall rate of acts of violence performed by protagonist characters was 22.7 (95% CI 16.8-30.7) mean events per hour. The overall rate of acts of violence performed by antagonist characters was 17.5 (95% CI 13.9-21.9) mean events per hour. With adjustment for significant reviewer variability, there was a statistically significant difference between the overall rates of acts of violence performed by protagonist vs. antagonist characters (p=0.019). The rates of both protagonist and antagonist violence were not found to significantly differ (p=0.16 and p=0.25, respectively) between the two types of film ratings.

The frequency of “fighting” events was found to significantly differ between protagonist and antagonist characters [9.4 (95% CI 6.9-13.0) vs. 5.5 (95% CI 3.8-8.1), p<0.001]. No other acts of violence showed a statistically significant difference between protagonist and antagonist.

The overall rate of acts of violence performed by male characters significantly differed [33.4 (95% CI 26.3-40.8) mean events per hour] compared with the overall rate of acts of violence performed by female characters [6.5 (95% CI 3.7-10.9) mean events per hour], p<0.001 with adjustment for significant variability among reviewers.

Moderate to good agreement among the reviewers was found using the intraclass correlation coefficient. Among the five reviewers, agreement among the frequency of acts of violence by the protagonist was 0.73, by the antagonist was 0.60, by the males was 0.57, and by the females was 0.82. Poisson regression models did indicate significant variability among the reviewers for each of the types of acts of violence (p<0.001).

Based on our sample of superhero-based films, protagonist characters performed significantly more acts of violence compared to antagonist characters. This contradicts the common assumption that protagonists are the “good guys,” and therefore perform lesser acts of violence compared with their “evil” counterparts. Furthermore, we found statistically significantly more acts of violence performed by male characters compared with female characters. This discrepancy may be due to the predominance of male leading characters in superhero-based films. Over time, the number of female characters in superhero-based films appears to be increasing, with more female characters present in such films as Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019). Future studies may be necessary to determine whether acts of violence performed by male and female characters differ with the increasing popularity and portrayal of female superhero and villains, potentially affecting the image adopted by pediatric viewers.

Although the Motion Picture Association of America provides a rating system to guide appropriate film viewing, this system does not accurately stratify the frequency of violent acts [ 7 ]. Our findings support the discrepancy present in the rating system, as we observed no statistically significant difference in the rate of violent acts performed by protagonist and antagonist characters between PG-13 and R-rated films. Thus, the number and type of acts of violence should be considered when applying the rating system to films.

The association between physical aggression and exposure to violent media has been previously published [ 12 - 16 ]. The amount of violence present in films has doubled since 1950, and gun violence present in PG-13 rated films has tripled since 1985 [ 17 ]. Children are known to learn from the observation of others’ behavior. Further, after observing that a behavior leads to a desired outcome, children often then try that behavior themselves. As superheroes are typically depicted in the media as “good”, children may view protagonist characters as role models. Therefore, children may interpret the behavior of a superhero to be acceptable, even when they are committing severely violent acts, such as “use of a lethal weapon”, “murder”, and “mass murder”. This relationship between violence depicted in the media and more frequent aggressive behavior has been found in several published studies [ 3 , 18 - 20 ]. Furthermore, McCrary suggested that television superheroes may influence the development of moral values in kindergarten-aged children, and Martin found that the feelings children have towards superheroes are related to the way in which they feel about themselves [ 21 - 22 ].

Exposure to violence depicted in superhero-based films may also affect older children and adolescents. Violent acts performed by adolescent and young adults, such as physical fighting, use of a lethal weapon, mass murder, and suicide, has been prevalent in our society. In 2015, 23% of high school students in the United States reported being involved in a physical fight and 16% of high school students in the United States reported carrying a weapon [ 23 ]. A recently published study has shown that 60% of mass school shootings in the United States in the 20th century were perpetrated by adolescents, aged 11-18, and so far this century, 77 % of the mass school shootings have been carried out by adolescents [ 24 ]. Furthermore, there has been an increase in self-harm performed by children, with the rate of suicide in preteens, aged 10-14 years doubling between 2007 and 2014 [ 25 ]. It has been shown that early exposure to violence confers a risk for suicide attempt and particularly suicide death in youth [ 26 ]. While there have been no published studies examining the exposure to violence depicted in superhero-based films and violent acts performed by adolescents and young adults, future studies should focus on this potential correlation.

The rate of bullying and cyberbullying has significantly increased over the past 10 years. In fact, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (2016), 20.8% of students in the United States reported being bullied, and of those students, 13% were made fun of, called names, or insulted; 12% were the subject of rumors; 5% were pushed, shoved, tripped, or spit on; and 5% were excluded from activities on purpose [ 27 ]. Bullying has been linked to increases in violent behavior [ 28 ]. Furthermore, an increase in exposure to antisocial media content is related to an increase in cyberbullying [ 29 ]. Based on our sample of superhero-based films, bullying/intimidation/torture is prevalent by both protagonists and antagonists, and therefore it is important to consider that children and adolescents may be learning these behaviors from the heroes and villains they see in superhero-based films.

An antidote to the increased violence depicted in superhero-based films involves co-viewing these movies as a family. Children, particularly aged 8 to 12 years, desire conversations with parents about violence. In passive co-viewing of media, there is an implicit message sent to the children that the parents approve of the content being viewed and a corresponding increase in aggressive behavior can be seen. However, if parents take an active role in their children’s media consumption via active mediation, changes are found in media-influenced behavior [ 30 ]. Active mediation occurs when parents discuss what it is being watched. This method encourages the development of critical thinking and internally regulated values. With regard to violence depicted in superhero-based films, we recommend that emphasis be placed on conflict resolution and respecting other's individuality.

There are several limitations to our study, primarily related to the selection and coding of films. We chose the 10 highest grossing superhero-based films released in 2015 and 2016 based on a popular film website. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to superhero-based films released before and since our chosen time period. Furthermore, since our selection was based on total box office gross profit, our sample of films may not represent the most popular or most watched films by children and adolescents during that time period, and pediatric viewers may access films online via streaming services that may not be reflected in the box office revenue. Lastly, we did not include any PG films in the analysis and therefore biases the results towards the more graphic violent films.

The coding of the films also represents a limitation. We found some variability in the number of events coded by each reviewer. Although coding guidelines were decided prior to our viewing of the study films, each reviewer may have interpreted scenarios, dialogue, and fighting sequences in the study films differently. Furthermore, all the reviewers were adults, who may interpret acts of violence differently than children and adolescents. Nevertheless, although our objective was to quantify acts of violence depicted in a select number of superhero-based films, the actual number of events may not be as important as the frequency in the depiction of acts of violence stratified by protagonist/antagonist and gender. Lastly, we neither did determine and quantify the intention by the major character in performing the depicted act of violence, nor did we consider the graphic nature of the violence. For example, the intention of a protagonist character in fighting or using a lethal weapon against an antagonist or causing destruction of property to protect a family or save a city would be different than the intention of an antagonist character in using a lethal weapon causing murder or mass murder, depicting massive hemorrhage, decapitations, or extremity amputations, to seek revenge against the protagonist. Although this distinction in the intention of a major character to perform an act of violence might be common sense to adolescents and adults, it may be less clear for children, and thus children may view what a superhero does as being acceptable even if the act is violent or graphic by nature.

Conclusions

Based on our sample of superhero-based films, acts of violence were associated with protagonist characters and male characters. Therefore, pediatric health care providers should educate families on the violence depicted in this genre of film and the potential dangers that may occur when children attempt to emulate these perceived heroes. To combat the inevitable inclusion of violence in superhero-based films, the authors suggest co-viewing via active mediation, emphasizing effective communication, identification of points of agreement and disagreement, and peaceful conflict resolution in dealing with disputes or dissension instead of resorting to acts of violence.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained by all participants in this study

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Are Superheroes Super Role Models? An Investigation of Behaviors and Attitudes in Superhero Movies

Related Papers

Dru Jeffries

Brandon Bosch

Drawing on research on authoritarianism, this study analyzes the relationship between levels of threat in society and representations of crime, law, and order in mass media, with a particular emphasis on the superhero genre. Although the superhero genre is viewed as an important site of mediated images of crime and law enforcement, cultural criminologists have been relatively quiet about this film genre. In addressing this omission, I analyze authoritarian themes (with an emphasis on crime, law, and order) in the Batman film franchise across different periods of threat. My qualitative content analysis finds that authoritarianism themes of fear and need for order and concern about aggressive action toward crime are more common in Batman films during high-threat periods. I also find that criticism of authority figures is more prevalent in Batman films during high-threat periods, which challenges previous research on authoritarianism as well as the alleged conservative media bias toward police.

The porn industry is following Hollywood’s lead by taking superheroes more seriously than either had in decades past. Contemporary superhero porn parodies, particularly those directed by Axel Braun, eschew the goofy puns and tacked-on themes that had previously defined the pornographic parody genre. These films present a unique point of intersection between Hollywood, the porn industry, and fandom. While female-oriented fandoms often devote considerable intellectual and creative energies to transforming patriarchal genres into shapes that better appeal to their interests and desires, male fandom seems much more inclined to keep the story the way it is. Braun’s parodies appropriate transformative textual practices usually associated with female fan productivity in order to seduce male fans, while also exploiting the industrial limitations of the mainstream superhero genre, and capitalizing on the legal freedoms afforded by their parody status. Often antagonistic to their mainstream counterparts, these hardcore films appeal to fans by confirming the value of an ‘original’ text by critiquing the shortcomings of official adaptations. If porn and the superhero genre usually speak to and express male power fantasies already, Braun’s porn parodies merely take current trends in superhero film aesthetics and fanboys’ fetish for fidelity to the next level.

Metro Magazine: Media & Education Magazine

Martyn Pedler

Leon Ford’s debut feature joins a growing subgenre that posits the everyman as an unconventional crime-fighting superhero. Beneath the rubber suit and flashy marketing, however, this story is suffering from an identity crisis, writes Martyn Pedler.

Mervi Miettinen

Joanna Hebda

Sociology of Crime, Law and Deviance

Bradford Reyns , Billy Henson

Martijn Oosterbaan

This article explores the aesthetic elements of sovereignty. Building on the anthropological literature on sovereignty and on contemporary work on the politics of aesthetics, the article analyzes contemporary appearances of Batman symbols and figures in Rio de Janeiro. Despite political debate and academic discussion about the Batmen appearing in mafia-like militias and popular street protests in Rio, the question of what these appearances tell us about the relations between popular imagery and political contestation has remained untouched. This article supports the work of writers who argue that superhero comics and movies present fierce figures that operate in the zone of indistinction, at the crossroads of lawful order and its exception. However, it adds to this literature an analysis that shows in what kind of sociopolitical contexts these figures operate and how that plays itself out. To understand the contemporary appearances and force of figures of the entertainment industry better, this article proposes the concept " popular culture of sovereignty. "

Queer(ing) Popular Culture, ed. Sebastian Zilles. Special Issue of Navigationen 18.1: (2018): 15-38

Daniel Stein

This essay analyzes the comic book superhero as a popular figure whose queer-ness follows as much from the logic of the comics medium and the aesthetic principles of the genre as it does from a dialectic tension between historically evolving heteronormative and queer readings. Focusing specifically on the superbody as an overdetermined site of gendered significances, the essay traces a shift from the ostensibly straight iterations in the early years of the genre to the more recent appearance of openly queer characters. It further suggests that the struggle over the superbody's sexual orientation and gender identity has been an essential force in the development of the genre from its inception until the present day.

RELATED PAPERS

moona iftikhar

Sigrid Jones

Ardnahc Rakehs

Liezille Jacobs

Jesselyn Lee

Andrea Waling

Nao Tomabechi

Joanna Nowotny

Christopher Weimer

Carrie Morrison

Grace Gipson

Carter Soles

Neil Shyminsky

William Svitavsky , Julian C Chambliss

Classics and the Modern World: A Democratic Turn? ed. L. Hardwick & S. Harrison

George Kovacs

York University

Anna F Peppard

Dominika Kotarbińska

Ryan Castillo

SPELL, Swiss Papers in English Language and Literature, Sonderheft American Communities: Between the Popular and the Political (hg. v. Julia Straub und Lukas Etter)

Joseph Clark

Tsuki Tsuki

Kent L Boyer, PhD

Space Oddities: Difference and Identity in the American City

johan hoglund

Chris Yogerst

Raoul Guariguata

Alejandra Matias Zavala

Niels Berggren

Situations: Cultural Studies in the Asian Context

Early Childhood Education Journal

Fran Blumberg

Roald Maliangkay , Situations: Cultural Studies in the Asian Context

Todd McGowan

Children & society

Jackie Harrison

Lorenzo Magnani

Teaching Religion and Violence

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Superheroines and Sexism: Female Representation in the Marvel Cinematic Universe

- Folukemi Olufidipe Doral Academy Charter High School

- Yunex Echezabal Doral Academy Charter High School

The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is the highest-grossing film franchise of all time and since the premiere of Iron Man in 2008, it has risen to fame as a source of science-fiction entertainment. Sexism in the film industry often goes brushed aside but the widespread success of Marvel Studios calls attention to their treatment of gender roles. This paper explores the progression of six female superheroes in the MCU and what effect feminist movements have had on their roles as well as upcoming productions in the franchise. This paper used an interdisciplinary, mixed-methods design that studied movie scripts and screen time graphs. 14 MCU movies were analyzed through a feminist film theory lens and whenever a female character of interest was chosen, notes were taken on aspects including, but not limited to, dialogue, costume design, and character relationships. My findings showed that females in the MCU are heavily sexualized by directors, costume designers, and even their male co-stars. As powerful as some of these women were found to be, it was concluded that Marvel lacks in female inclusivity. Marvel’s upcoming productions, many of which are female-focused, still marginalize the roles of their superheroines which is a concern for the future of the film industry. Marvel is just one franchise but this study shows how their treatment of female characters uphold patriarchal structures and perpetuate harmful stereotypes that need to be corrected in the film industry as a whole.

References or Bibliography

Bateman, D. (2015). The Avengers. Science Fiction Film and Television, 8(2), 285-289. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1694690466?accountid=192155

Black, Shane, director. Iron Man 3. Marvel Studios, 2013.

Boden, Anna and Ryan Fleck, directors. Captain Marvel. Marvel Studios, 2019.

Bowen, Daniel Huw. “‘I Hope Daddy Isn’t as Big of a Dick as You’: Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, Fatherhood and Its Legacy.” Fantasika Journal, vol. 1, no. 2, Dec. 2017, pp. 199–202.

Burkett, Elinor, and Laura Brunell. “The Fourth Wave of Feminism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 16 Dec. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/feminism/The-fourth-wave-of-feminism .

“Commentary,” Avengers: Infinity War, directed by Anthony Russo and Joe Russo (Burbank: Marvel Studios 2018), Blu-ray.

DeMarchi, Mary Louise, "Avenging women: an analysis of postfeminist female representation in the cinematic Marvel’s Avengers series" (2014). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 167. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/167

Dorey-Stein, Caroline. “A Brief History: The Four Waves of Feminism.” Progressive Women's Leadership, 28 June 2018, www.progressivewomensleadership.com/a-brief-history-the-four-waves-of-feminism/.

Favreau, Jon, director. Iron Man. Marvel Studios, 2008.

Favreau, Jon, director. Iron Man 2. Marvel Studios, 2010.

“Feminist Film Theory.” Film Theory, 6 Aug. 2015, www.filmtheory.org/feminist-film-theory/.

“Film Analysis.” Writingcenter.unc.edu, writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/film-analysis/.

Gunn, James, director. Guardians of the Galaxy. Marvel Studios, 2014.

Gunn, James, director. Guardians of the Galaxy Vol.2. Marvel Studios, 2017.

Hesse-Biber, Sharlene. “Qualitative or Mixed Methods Research Inquiry Approaches: Some Loose Guidelines for Publishing in Sex Roles.” Sex Roles, vol. 74, no. 1–2, Jan. 2016, pp. 6–9. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1007/s11199-015-0568-8.

Jacobs, Christopher P. “Film Theory and Approaches to Criticism, or, What Did That Movie Mean?” University of North Dakota, 5 Jan. 2013.

Joffe, Robyn. “Holding Out for a Hero(Ine): An Examination of the Presentation and Treatment of Female Superheroes in Marvel Movies.” Panic at the Discourse, 5 Apr. 2019, www.panicdiscourse.com/holding-out-for-a-heroine/.

Joho, Jess. “Captain Marvel's Shallow Take on Feminism Doesn't Land.” Mashable, 9 Mar. 2019, mashable.com/article/captain-marvel-feminism-female-superhero/.=

Kinnunen, Jenni. “Badass Bitches, Damsels in Distress, or Something in between? : Representation of Female Characters in Superhero Action Films.” University of Jyväskylä, Apr. 2016, https://jyx.jyu.fi/handle/123456789/49610 .

“Marvel Characters, Super Heroes, & Villains: Marvel.” Marvel Entertainment, www.marvel.com/characters.

“MCU Movies Screen Time Breakdown.” IMDb, IMDb.com, 2 July 2019, www.imdb.com/list/ls066620113/?sort=release_date,asc&st_dt=&mode=detail&page=1.

Nichols, Bill. Engaging Cinema: An Introduction to Film Studies. New York: W.W. Norton, 2010. Print.

Poepsel, Mark, and Madelaine Gerard. “Black Widow: Female Representation in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.” Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences Journal, vol. 8, no. 2, 2018, pp. 27–53., https://ojcs.siue.edu/ojs/index.php/polymath/article/view/3314 .

Russo, Anthony and Joe Russo, directors. Avengers: Endgame. Marvel Studios, 2018.

Russo, Anthony and Joe Russo, directors. Avengers: Infinity War. Marvel Studios, 2019.

Russo, Anthony and Joe Russo, directors. Captain America: Civil War. Marvel Studios, 2016.

Russo, Anthony and Joe Russo, directors. Captain America: The Winter Soldier. Marvel Studios, 2014.

Sherrer, Kara. “What Is Tokenism, and Why Does It Matter in the Workplace?” Vanderbilt Business School, 26 Aug. 2019, business.vanderbilt.edu/news/2018/02/26/tokenism-in-the-workplace/.

Smelik, Anneke. “Feminist Film Theory.” The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, 21 Apr. 2016, pp. 1–5., doi:10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss148.

Waititi, Taika, director. Thor: Ragnarok. Marvel Studios, 2017.

Watts, Jon, director. Spider-Man: Homecoming. Marvel Studios, 2017.

Whedon, Joss, director. Avengers: Age of Ultron. Marvel Studios, 2015.

Whedon, Joss, director. The Avengers. Marvel Studios, 2012.

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2021 Folukemi Olufidipe; Yunex Echezabal

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Copyright holder(s) granted JSR a perpetual, non-exclusive license to distriute & display this article.

Announcements

Call for papers: volume 13 issue 3.

If you are a high school student or a recent high school graduate aspiring to publish your research, we are accepting submissions. Submit Your Article Now!

Deadline: 11:59 p.m. May 31, 2024

- CFP for Issue 3.1

- CFP for Issue 3.2

- CFP for Issue 4.2

Comic book movies can’t decide whether superheroes are human or posthuman, but either way they have reached a dead end.

How to Cite

Biskind, P., (2022) “Superheroes: The Endgame - Review of Superhero Movies”, Global Storytelling: Journal of Digital and Moving Images 1(2). doi: https://doi.org/10.3998/gs.1708

Download XML Download PDF View PDF

For years we’ve been throwing our box office dollars at beefy men in tights (aka superheroes) who promise to protect us from a laundry list of dangers after the imbecile authorities have failed yet again to do so. And it’s not only the cops and politicians who are largely absent from the comic book blockbusters, or, if present, they are part of the problem, but it’s us, humans, who just aren’t up to doing the job themselves. And now we see that the superheroes don’t seem to be much good at it either. In the Russo brothers’ Avengers: Infinity War (2018) and Avengers: Endgame (2019), they allow melancholy Thanos, the big, bad ender-of-worlds in the two most recent Avenger movies, to turn them and half of humanity into ash by snapping his fingers. It takes them five and a half hours spread over two movies, not to mention the waste of a considerable amount of acting talent, to repair the damage. What is it with these costumed freaks? The problem seems to be that they are, when all is said and done, too much like us, too human.

This was never the case in the past, when Superman and Batman dispatched our enemies with ease. The splashy costumes they favored worked to emphasize the differences that distinguish them from mere mortals. Reflecting on his outfit in one of the Dark Knight movies, Batman says, “A man, however strong, however skilled, is just flesh and blood. I need to be more than a man. I need to be a symbol.” 1 As he puts it, by transforming himself into a symbol, he dehumanizes himself.

Discarding the human, and favored with extraordinary powers, superheroes are by definition posthuman . (In Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice [2016], they’re called “metahumans” and elsewhere “transhumans.”) Posthuman, an imprecise, omnibus term that describes real-world human upgrades facilitated by advances in AI, nanotechnology, genetic engineering, and prosthetics along with, in the unreal world of these narratives, a grab bag of transformations caused by encounters with aliens, radiation, and so on.

Posthumanism has been theorized in many ways, but generally speaking, it is a species of antihumanism . One thread that runs through its iterations is that of decentering humans, elbowing them out of their place at the center of the universe where humanism had placed them, discarding the notion of human autonomy and exceptionalism, and reembedding them in the social and/or evolutionary pudding from which they emerged. Posthumanists would probably agree with Stephen Hawking’s famous characterization of his species, when he called it “an advanced breed of monkeys on a minor planet of a very average star.” 2

Thus minimized, humans have nearly disappeared from the MCU (Marvel Cinematic Universe). The few who appear are usually those useless authority figures, the senators, generals, and presidents. With few exceptions, every one of them is small-minded, stupid, and/or corrupt. In most of these shows, our superheroes are at war with external enemies, aliens of one sort or another, but in a real sense, they’re just a pretext. The real enemies are at home, in our government and among our “friends.” In Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), they want to send Black Widow to prison for dumping compromising files onto the Internet, Snowden-style, and the movie sides with her, not them. In Iron Man 2 (2010), actor Garry Shandling’s generic senator tries to claim Tony Stark’s Iron Man super suit for the US government. Tony refuses, and the movie sides with him, not the government.

Samuel L. Jackson, who is (or was) a bigger star than most of the interchangeable ingénues of both genders behind those kitschy masks and hoods, plays Nick Fury, a mere mortal at one time and a mainstay of the MCU, but he’s largely disappeared from the movies. Jackson’s problem isn’t that he’s black—there are plenty of people of color in these films—it’s that he’s human and has therefore been marginalized. Explaining his absence from Avengers : Age of Ultron (2013), Jackson observed, “It’s another one of those ‘people who have powers fighting people who have powers’ [movies]. There’s not a lot I could do except shoot a gun,” 3 and guns, by this time, are little better than tomahawks or slingshots. The same holds true for Captain America: Civil War . In Infinity War , the darkest-before-the-dawn first installment of the recent two-parter, Fury has a cameo in the obligatory buried-in-the-credits Easter egg, but no sooner does he appear than he disappears, turned to ash by the Thanos before he can even finish a phone call.

Absent in Infinity War and Endgame is the issue of collateral damage that preoccupied the two films, Civil War and Ultron , that preceded them. Concern for the welfare of the human bystanders who were casualties of the conflicts that consume these shows became irrelevant when there are virtually no bystanders—that is, humans, in either of the latter. Like our superheroes, they’re presumably turned to ash, but we rarely see it. Moreover, it’s the remnant of humanity in superheroes that gets them into trouble.

Superheroes have always shown emotions, however attenuated, but now, when they express their feelings, it’s their undoing, like Dr. Strange who has to hand over the Time Stone to Thanos to save Tony’s life. Scarlet Witch refuses to deny Thanos the Mind Stone by destroying it, because it’s embedded in Vision’s forehead. Thanos, unimpeded by human emotion, gets it anyway, by tearing it out of his head, and in the process kills Vision.

It is precisely Thanos’s inability to experience emotion that gives him the advantage over the Avengers. He professes to feel for his daughter Gamora, but he hurls her to her death anyway, so he can secure the Soul Stone, the last of the six stones that will give him infinite power. Before she disappears into the void, she tells him that he “loves no one,” and she’s right, sort of. It’s not Gamora he loves but himself. As he puts it, “I ignored my destiny once. I cannot do that again.” We know from Game of Thrones that destiny lovers are tyrants waiting to happen.

The triangular relationship between Clark Kent, Lois Lane, and Superman varies from film to film depending on who’s writing, directing, and producing, but initially, at any rate, Clark loves Lois who loves Superman; its only human Lois and faux-human Clark who are allowed feelings. When Superman finally comes around and decides to marry her, he has to shed his super powers. Later, Lois becomes his Achilles heel, used against him by Lex Luthor, just as Thanos manipulates the Avengers into giving up the stones by threatening their friends and loved ones.

Secret identities like Clark Kent were the last outposts of the human in these stories, but with the exception of Peter Parker (aka Spider-Man), most of Marvel’s superheroes have lost interest in them, another indication of the marginalization of humans. First to go was the “secret.” Today’s superheroes, Marvel’s in particular, are well out of the closet. No more darting into phone booths for a quick costume change. (No more phone booths!) Everybody knows that Iron Man is Tony Stark, that Captain America is Steve Rogers, and DC’s Wonder Woman is Diana Prince. The secret identities of some superheroes, like Thor, have disappeared into the mists of time. They no longer need to fly false flags and elude their human charades in order to come into their own, because they no longer yearn to live “normal” lives. Their superhero identities have cannibalized their workaday human identities.

The original rationales for secret identities—protecting loved ones from bad guys and the superheroes themselves from the cops who don’t take kindly to DIY justice—have evaporated, perhaps as a result of the decay of the rule of law and the consequent relaxation of the taboo against vigilantism.

To some extent, the characters in the most recent Avengers movies face the same problem as the characters in Game of Thrones : What is the best way to organize human society so that it will survive? It’s a political problem, and both shows, despite the royals in Game of Thrones and the superheroes in the Avengers films, unsurprisingly come down on the side of democracy as opposed to tyranny. They endorse inclusion and consensus rather than exclusion and coercion. In Game of Thrones , the characters need to put aside the dynastic feuds with which they amuse themselves in favor of alliances that will enable them to defeat the army of the undead White Walkers. As Jon Snow tells Queen Cersei, trying to persuade her to join his coalition of the flesh and blood, “This isn’t about noble houses, this is about the living and the dead.” Likewise, in Infinity War , when Tony tells Bruce Banner that he can’t enlist Cap in the struggle against Thanos because they’re not on speaking terms, Bruce retorts, “Thanos is coming. It doesn’t matter who you’re talking to or not.” 4 On the other hand, it doesn’t matter whether the superheroes fight Thanos individually or in groups. They lose either way.

Superhero movies, on the whole, are darker than Game of Thrones . The message of the HBO series, “Win together, lose alone,” is lost in the mayhem. In the Avengers and X-Men franchises, the issue is not so much political as ontological. Game of Thrones may ask the question, Of what sort of stuff is society made? The superhero movies, on the other hand, ask, Of what sort of stuff are humans made? In X-Men: First Class (2011), standing on a beach facing US and Soviet warships in the film’s version of the Cuban Missile Crisis, mutant Erik/Magneto gets to the heart of the matter when he observes that the hostile forces arrayed against them, albeit themselves mortal enemies, are basically identical: “humans.” 5

Where does this jaundiced view of human nature come from? Its roots can be traced back to the origins of both Marvel and DC Comics in the run-up to World War II. Superman first appeared in Action Comics #1, published in 1938. With Germany on the march across Europe, the United States was still officially neutral when, on December 20, 1940, almost a full year before Pearl Harbor, Captain America appeared on the cover of Timely Comics, which eventually evolved into Marvel, socking Hitler in the jaw. He represented writer Joe Simon’s and artist Jack Kirby’s contribution to the propaganda effort on behalf of America’s entry into the war.

Marvel never outgrew its antifascist antecedents. World War II has always served as something of a touchstone for its family of superheroes. Two X-Men movies open in Nazi death camps, and as the MCU expands, we see that all those vile authority figures are actually Nazis, agents of Hydra, a secret society organized by the Waffen SS just prior to World War II, that has managed to penetrate every nook and cranny of America’s government. Marvel’s long, albeit waning obsession, with Hitler, combined with concern that posthumans may turn against us, eventually undermines its attempts to achieve the posthuman. The kind of dehumanization of superheroes expressed by Batman is equated with fascism. In Captain America: The First Avenger (2011), it’s Herr Schmidt, speaking for the rest of the Nazi ubermenschen , who tells Cap, “I am proud to say that we have left humanity behind.” 6

Once superheroes succeed in breaking free from the human, most of them shrink from the result and make their way back to it, as if its pull is so strong they can’t escape it. When the posthumans in these shows look into the mirror, they don’t like what they see. The truth is that the best superheroes are the least super, and the best posthumans are the least post—and the most human. The failure of these shows and movies to dramatize the posthuman suggests that despite their insistence that humanism is bankrupt, they are unable to move beyond it. There is no way out. They’re trapped. The desire to break with the human has so far outpaced the ability of humans to imagine what a posthuman future might be like or what kind of creatures posthumans might be. No matter how much people long to escape the constraints of the human, they fall back to Earth. Which is one of the reasons the original Planet of the Apes , released in 1968, is one of the most prescient movies ever made.

The rehumanization of superheroes began in earnest with Peter Parker in 1962, when Marvel writer and editor Stan Lee decided they should be more relatable. He wanted the young Spider-Man to suffer from adolescent anxieties: acne, insecurity, girl trouble, and so on. He recalled, “My publisher said, in his ultimate wisdom, ‘Stan, that is the worst idea I have ever heard… He can’t have personal problems if he’s supposed to be a superhero—don’t you know who a superhero is?’ ” The rest, as they say, is history. Not only did Peter Parker come into his own, but Superman spun off the TV series, Smallville , that ran for a decade (2001–11) and chronicled the adventures of a teenage Clark Kent. Fox launched its Batman origins series, Gotham , which dramatizes the lives of the youthful Bruce Wayne and his young-adult super villains.

Marvel’s humanization of superheroes has gone so far that the Avengers are portrayed as a quarrelsome, jealous, and petty bunch who spend more time squabbling among themselves than they do battling their enemies, a side effect, no doubt, of the steroid smoothies they’ve been drinking and the testosterone patches hidden beneath their spandex suits. They have to be constantly reminded that they are in fact on the same side.

Tony Stark had been dipping his iron toes into the tepid waters of the mainstream for some time. He is torn between human and superhuman, confused about who and what he is. And like Spider-Man, he is a first-class neurotic. Indeed, director Jon Favreau explained that he wanted to make Iron Man vulnerable—that is, more human. In an early script draft of Iron Man 3 , Tony even confides to his girl Friday and eventual partner, Pepper Potts, that ever since the Chitauri had their way with Grand Central Station in the original Avengers (2012), he has felt vulnerable, and he actually starts to weep, behavior so unbecoming a superhero that the scene was wisely omitted from the movie. Still, he may not have needed a Kleenex, but he does need a therapist. He suffers from anxiety attacks. Anxiety attacks? The series also features homelessness and even alcoholism—alluding to Robert Downey Jr.’s then personal problems.

Whereas Tony once considered the Iron Man suit—that is, his superhero, posthuman alter ego—an asset, he now experiences it as a liability, a prison, even an adversary. Instead of clumsily climbing into it, as he once did, he devises a way of summoning the suit to him from afar. It soars through the air in pieces—a gauntlet here, a breastplate there—assembling itself around his body. Well enough and good, but just as often the pieces bang into him or, worse, refuse to coalesce and therefore fail him entirely. With an outfit like that, it’s no wonder he spends most of Iron Man 3 as Tony—minus his suit and superpowers. In Civil War , Tony doesn’t become Iron Man until two-thirds of the way through, and then he’s often without his helmet, reminding us that for all Iron Man’s superpowers he is, as Tony once put it, no more than a “man in a can.”

Tony’s flop sweats are by no means unique. By the time Logan was released in 2017, four years after Wolverine , the X-Men, including the lupine superhero played by Hugh Jackman, are in decline. The one super villain that can’t be denied is time, although our friends do manage to pull off a “time heist” in Endgame . As Logan puts it, “Nature made me a freak. Man made me a weapon. And God made it last too long. The world is not the same as it was. Mutants … they’re gone now.” 7 Shaggy, scarred, and haggard, he looks half dead and actually dies at the end, mourning the human feelings that he long ago sacrificed for his superpowers.

Logan has plenty of company. In Infinity War , the entire MCU implodes. Twelve superheroes, including Black Panther, Spidey, and Doctor Strange, apparently breathe their last, as well as Loki who dies for the third time, all victims of Thanos. We won’t forget the day that the invulnerable became vulnerable, just like humans. Thanks to quantum physics and especially multiverses that go all the way back to 1944’s Mister Mxyzptik, a Superman character apparently from the fifth dimension, none of the Marvel superheroes, including those in the recent streaming hit WandaVision , really die; they all come back in one way or another. Kellyanne Conway, with her “alternative facts,” was clearly a comic book fan.

True, Thanos seems to be culling the first-generation Avengers, preparing the way for a new crop coming up behind them, but who knew superheroes grew old and died or were just conveniently whisked off-stage when their contracts expired.

Even Batman has had enough. He may once have wanted to hollow himself of human emotion so that he might became a symbol, but by the time of The Dark Knight Rises (2012), he is so eager to get out of those spandex tights that he fakes his own death so that Bruce Wayne can sip cappuccinos at a sidewalk cafe in Florence with Catwoman, Selina Kyle, like a normal person—that is, a human. Can marriage and family be far off? In Endgame , Cap is sent back in time to the 1950s, settles down with Peggy Carter, and stays there. Black Widow sacrifices herself so Hawkeye can seize the Soul Stone and his family, dissolved by Thanos, can be restored to him. Could it be that all that sturm und drang was just about restoring family? We learned from Game of Thrones that family is a double-edged sword, at the heart of the conflicts that rend the Seven Kingdoms. Loyalty to family is overrated. Maybe the Russos weren’t watching.

Not only do individual posthuman heroes drift back to the human, but humanity itself, after being savaged in show after show, movie after movie, makes a comeback. Pace Erik/Magneto and his ilk, it’s not a cesspool of depravity after all. We come to suspect that its tawdry reputation is unfounded because the accusations against it are put in the mouths of villains. In Wonder Woman , it’s Ares who tries to convince the Amazonian warrior to join him in exterminating humans because “they are ugly, filled with hatred, weak.” 8 Ares, however, is a bad guy, the god of war, so we can discount his words. On the contrary, humanity needs to be saved.

Thanos is just one more in a long line of super villains who refuses to rehumanize dehumanized humanity. He’s another version of Ultron, an AI created by Tony Stark to protect humanity from any and all threats. Ultron concludes, however, that humans themselves are the biggest danger to humanity and decides to exterminate them. Using similar logic, Thanos, cloaked with the mantle of an eco-warrior, says, “This universe is finite. Its resources are finite. If life is left unchecked, life will cease to exist.” He goes on, “It needs correction … but random, dispassionate, fair to rich and poor alike. I call that mercy.”

There’s a Green Lantern comic in which a young woman is killed and crammed into a refrigerator. Comics writer Gail Simone coined the term “fridging” to refer to a common trope where women are harmed for the express purpose of motivating men to take action. If “humans” are substituted for “women,” we have a key to unlocking Endgame .

Thanos’s eco-argument may be no more than a rationalization for bad behavior, but he has a point. As the reality of human-caused climate change—extreme weather, rising seas, and the extinction of countless animal and plant species—becomes inarguable, we have come to understand that humans are the biggest threat to humanity and our planet. For all that the MCU nods in the direction of racial and gender equality, Endgame locks humans in a refrigerator, as it were, to motivate the Avengers to get off their butts for round two against Thanos. Antman and Hawkeye rouse the farflung superheroes who are feeling sorry for themselves, indulging the senses, or lolling about in domestic bliss, to do what they’re supposed to be good at: avenging. This is all well and good, but by casting Thanos as an eco-warrior and then shrugging off his argument, Endgame implicitly sides with the climate-change deniers. Watching Marvel’s two-parter, it would be easy to conclude that those who concern themselves with the health of our planet must be fought tooth and nail. The effect of humanizing superheroes, abandoning posthumanism, and sentimentalizing the family is paradoxically to move a historically left-leaning franchise to the right.

Black Widow , one of the latest off the Marvel assembly line, jumping back in time, sentimentalizes the family as well, at first by negation—the family Natasha Romanoff and her sister Yelena Belova thought they had but didn’t. Initially, the picture seems like it could have been directed by Paige Jennings, the daughter who breaks with the family in The Americans , until Romanoff realizes that her real family is the Avengers. Little does she know what lies in wait.

- Batman Begins , directed by Christopher Nolan (Los Angeles: Warner Bros., 2005). ⮭

- Jane Onyanga-Omara, “Stephen Hawking’s Memorable Quotes: ‘We Are Just an Advanced Breed of Monkeys,’ ” USA Today, March 14, 2018, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2018/03/14/stephen-hawking-quotations/423145002/ . ⮭

- Graeme McMillan, “Samuel L. Jackson on ‘Avengers: Age of Ultron’ Role: ‘I’m Not Doing So Much,’ ” Hollywood Reporter, March 26, 2014, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/samuel-l-jackson-avengers-age-691388/ ⮭

- Avengers: Infinity War , directed by Anthony and Joe Russo (New York: Marvel Studios, April 23, 2018). ⮭

- X-Men: First Class , directed by Matthew Vaughn (New York: Marvel Entertainment, May 25, 2011). ⮭

- Captain America: The First Avenger , directed by Joe Johnston (New York: Marvel Studios, 2011). ⮭

- Avengers Endgame , directed by Anthony and Joe Russo (New York: Marvel Studios, 2019). ⮭

- Wonder Woman, directed by Patty Jenkins (Los Angeles: Warner Bros., 2017). ⮭

Author Biography

Peter Biskind is the author of Easy Riders, Raging Bulls , Down and Dirty Pictures , The Sky Is Falling , several other books, and innumerable articles. He was the editor of American Film Magazine and Executive Editor of Premiere magazine. He is currently writing a book about television called Anything Goes: How Cable and Streaming Revolutionized TV .

- Download XML

- Download PDF

- Volume 1 • Issue 2 • Winter 2021

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0

Identifiers

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/gs.1708

File Checksums (MD5)

- XML: 876417d50d4f33b527f2a05c0e47f794

- PDF: e2cee6ca01ab6f5e8efbec8c4c4c49ac

Table of Contents

Non specialist summary.

This article has no summary

- Sub Journals

- Peer Review Policy

- Short Guide to New Editors

- Retraction Guidelines

- Research Institute

- Recommendations for the Board of Directors

- Editor Research Audit and Service Assessments

- Guidelines for Journals Publishers

- Code of Conduct for Journal Publishers

- Commandment in Social Media

- Suggestions

- Authorship Disputes

- Rights and Responsibilities

- About the Publisher

- Call for Papers

- Editorial Team

- Submissions

Gender Representation in Female Superhero Movies

Yousuf Hasan Parvez

representation, superhero films, male gaze, female gaze, gender role

Abstract The superhero film is one of the most popular movie genres in the entertainment world Viewers have enthusiasm about the portrayal of key male and female characters The way costumes appearances narrative gestures and languages are presented is also a matter of eagerness for spectaculars The study has looked at how gender is represented in female superhero movies It has been analyzed whether the female protagonist in these movies is portrayed according to the traditional gender roles If any male gaze perspective or female gaze perspective has been found then it has been interpreted Movies like Black Widow Birds of Prey and The Suicide Squad have been selected through the purposive sampling technique The study is conducted with the help of representation theory and feminist film theory Content analysis and discourse analysis are used as research methodology The study has found that the female protagonist has come out of the traditional gender role in the movie Black Widow and Birds of Prey The male gaze perspective is almost absent in these movies except in The Suicide Squad However the main female character Harley Quinn could not get out of the traditional gender role in the movie Suicide Squad

- Article PDF

- TEI XML Kaleidoscope (download in zip)* (Beta by AI)

- Lens* NISO JATS XML (Beta by AI)

- HTML Kaleidoscope* (Beta by AI)

- DBK XML Kaleidoscope (download in zip)* (Beta by AI)

- LaTeX pdf Kaleidoscope* (Beta by AI)

- EPUB Kaleidoscope* (Beta by AI)

- MD Kaleidoscope* (Beta by AI)

- FO Kaleidoscope* (Beta by AI)

- BIB Kaleidoscope* (Beta by AI)

- LaTeX Kaleidoscope* (Beta by AI)

How to Cite

Yousuf Hasan Parvez. (2023). Gender Representation in Female Superhero Movies. Global Journal of Human-Social Science , 23 (C3), 29–42. Retrieved from https://socialscienceresearch.org/index.php/GJHSS/article/view/103699

Download Citation

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Copyright (c) 2023 Authors and Global Journals Private Limited

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Making Men of Steel: Superhero Exposure and the Development of Hegemonic Masculinity in Children

- Original Article

- Published: 13 June 2022

- Volume 86 , pages 634–647, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Sarah Coyne ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1403-8726 1 ,

- Jane Shawcroft 1 ,

- Jennifer Ruh Linder 2 ,

- Haley Graver 1 ,

- Matthew Siufanua 1 &

- Hailey G. Holmgren 1

3573 Accesses

9 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

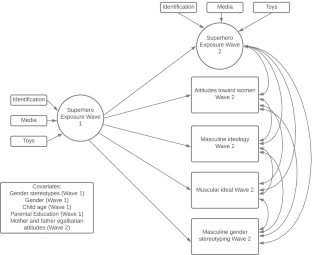

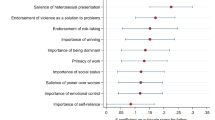

Superheroes are extremely popular among children, adolescents, and adults in the United States (and worldwide). However, there is little research on the impact of superhero exposure on developmental outcomes, particularly over time. The current paper includes a 5-year longitudinal study examining the relationship between superhero exposure in early childhood and indicators of hegemonic masculinity in later childhood, including endorsement of masculinity ideology, muscular ideal, and male gender stereotypes, and attitudes toward women. Participants included 155 children (51% female, M age = 4.83 years at Wave 1) and their parents, who completed several questionnaires at two separate time points. Analyses revealed that early superhero exposure was indirectly associated with weaker egalitarian attitudes toward women and greater endorsement of the muscular ideal during later childhood through superhero exposure in late childhood. Implications for individuals, parents, and media producers are discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Is My Femininity a Liability? Longitudinal Associations between Girls’ Experiences of Gender Discrimination, Internalizing Symptoms, and Gender Identity

Adam A. Rogers, Rachel E. Cook & Kaitlyn Guerrero

Like Father, Like Son: Empirical Insights into the Intergenerational Continuity of Masculinity Ideology

Francisco Perales, Ella Kuskoff, … Tania King

It’s a Bird! It’s a Plane! It’s a Gender Stereotype!: Longitudinal Associations Between Superhero Viewing and Gender Stereotyped Play

Sarah M. Coyne, Jennifer Ruh Linder, … Kevin M. Collier

Adams, G., Turner, H., & Bucks, R. (2005). The experience of body dissatisfaction in men. Elsevier, 2 (3), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.05.004

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53 , 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Andrews, K., Lariccia, L., Talwar, V., & Bosacki, S. (2021). Empathetic concern in emerging adolescents: The role of theory of mind and gender roles. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 41 (9), 1394–1424. https://doi.org/10.1177/02724316211002258

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Arbour, K. P., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2006). Effects of exposure to muscular and hypermuscular media images on young men’s muscularity dissatisfaction and body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 3 (2), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.03.004

Baghurst, T., Hollander, D. B., Nardella, B., & Haff, G. G. (2006). Change in sociocultural ideal male physique: An examination of past and present action figures. Body Image, 3 (1), 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.11.001

Baker, K., & Raney, A. A. (2007). Equally super?: Gender-role stereotyping of superheroes in children’s animated programs. Mass Communication & Society, 10 , 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430709337003

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3 (3), 265–299. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0303_03

Barlett, C. P., & Harris, R. J. (2008). The impact of body emphasizing video games on body image concerns in men and women. Sex Roles, 59 (7–8), 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9457-8

Barlett, C., Vowels, C., & Saucier, D. A. (2008). Meta-analysis of the effects of media images on male-body concerns. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27 (3), 279–310. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.3.279

Barr, B., & Winer, N. (2017). Suited for success? Suits, status, and hybrid masculinity. Men and Masculinities, 22 (2), 151–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184x17696193

Bem, S. L. (1981). Bem sex role inventory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . https://doi.org/10.1037/t00748-000 .

Blond, A. (2008). Impacts of exposure to images of ideal bodies on male body dissatisfaction: A review. Elsevier, 5 (3), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.02.003

Blovin, A. G., & Goldfield, G. S. (1995). Body image and steroid use in male bodybuilders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 18 , 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199509)18:2%3c159::AID-EAT2260180208%3e3.0.CO;2-3

Boldizar, J. P. (1991). Assessing sex typing and androgyny in children: The children’s sex role inventory. Developmental Psychology, 27 (3), 505–515. https://doi-org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1037/0012-1649.27.3.505

Botta, R. A. (2003). For your health? The relationship between magazine reading and adolescents’ body image and eating disturbances. Sex Roles, 48 , 389–399.

Boyd, H., & Murnen, S. K. (2017). Thin and sexy vs. muscular and dominant: Prevalence of gendered body ideals in popular dolls and action figures. Body Image, 21 , 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.03.003

Brown, L. M., Lamb, S., & Tappan, M. (2009). Packaging boyhood: Saving our sons from superheroes, slackers, and other media stereotypes . St. Martin’s Press.

Book Google Scholar

Bryant, J., & Miron, D. (2004). Theory and research in mass communication. Journal of Communication, 54 (4), 662–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02650.x

Burch, R. L., & Johnsen, L. (2020). Captain Dorito and the bombshell: Supernormal stimuli in comics and film. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 14 (2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000164

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106 , 676–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.4.676

Caso, D., Schettino, G., Fabbricatore, R., & Conner, M. (2020). “Change my selfie”: Relationships between self-objectification and selfie-behavior in young Italian women. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 50 (9), 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12693

Choi, N., Fuqua, D. R., & Newman, J. L. (2009). Exploratory and confirmatory studies of the structure of the Bem Sex Role Inventory short form with two divergent samples. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69 (4), 696–705. https://doi-org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1177/0013164409332218

Chonchaiya, W., Sirachairat, C., Vijakkhana, N., Wilaisakditipakorn, T., & Pruksananonda, C. (2015). Elevated background TV exposure over time increases behavioural scores of 18-month-old toddlers. Acta Paediatrica, 104 (10), 1039–1046. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13067

Chu, J. Y., Porche, M. V., & Tolman, D. L. (2005). The adolescent masculinity ideology in relationships scale: Development and validation of a new measure for boys. Men and Masculinities, 8 (1), 93–115. https://doi-org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1177/1097184X03257453

Cingel, D., Sumter, S., & Jansen, M. (2020). How does she do it? An experimental study of the pro- and anti-social effects of watching superhero content among late adolescents. Publication Cover Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 64 , 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2020.1799691

Collier, K. M., Coyne, S. M., Rasmussen, E. E., Hawkins, A. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Erickson, S. E., & Memmott-Elison, M. K. (2016). Does parental mediation of media influence child outcomes? A meta-analysis on media time, aggression, substance use, and sexual behavior. Developmental Psychology, 52 (5), 798–812. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000108

Connell, R. W. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

Google Scholar

Coogan, P. (2009). The Definition of a Superhero. In J. Heer & K. Worcester (Eds.), A comics studies reader (Illustrated ed., pp. 77–92). University Press of Mississippi.

Coyne, S. M. (2016). Effects of viewing relational aggression on television on aggressive behavior in adolescents: A three-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 52 (2), 284–295. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000068

Coyne, S. M., Linder, J. R., Booth, M., Keenan, K. S., Shawcroft, J. E., & Yang, C. (2021a). Princess power: Longitudinal associations between engagement with princess culture in preschool and gender stereotypical behavior, body esteem, and hegemonic masculinity in early adolescence. Child Development, 92 (6), 2413–2430. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13633

Coyne, S. M., Linder, J. R., Rasmussen, E. E., Nelson, D. A., & Collier, K. M. (2014). It’s a bird! it’s a plane! it’s a gender stereotype!: Longitudinal associations between superhero viewing and gender stereotyped play. Sex Roles, 70 (9–10), 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0374-8

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A., Shawcroft, J., & Hurst, J. L. (2021b). Dressing up with disney and make-believe with marvel: The impact of gendered costumes on gender typing, prosocial behavior, and perseverance during early childhood. Sex Roles, 85, 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01217-y

Coyne, S., Stockdale, L., Linder, J. R., Nelson, D. A., Collier, K. M., & Essig, L. W. (2017). Pow! Boom! Kablam! Effects of viewing superhero programs on aggressive, prosocial, and defending behaviors in preschool children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 45 , 1523–1535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0253-6

Dotti Sani, G. M., & Quaranta, M. (2016). The best is yet to come? Attitudes toward gender roles among adolescents in 36 countries. Sex Roles, 77 (1–2), 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0698-7

Dour, H. J., & Theran, S. A. (2011). The interaction between the superhero ideal and maladaptive perfectionism as predictors of unhealthy eating attitudes and body esteem. Body Image, 8 (1), 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.10.005

Galambos, N. L., Petersen, A. C., Richards, M., & Gitelson, I. B. (1985). The attitudes toward women scale for adolescents (AWSA): A study of reliability and validity. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 13 (5–6), 343–356. https://doi-org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1007/BF00288090

Golombok, S., & Rust, J. (1993). The pre-school activities inventory: A standardized assessment of gender role in children. Psychological Assessment, 5 (2), 131–136. https://doi-org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.131

González-Velázquez, C. A., Shackleford, K. E., Keller, L. N., Vinney, C., & Drake, L. M. (2020). Watching Black Panther with racially diverse youth: Relationships between film viewing, ethnicity, ethnic identity, empowerment, and wellbeing. Review of Communication, 20 (3), 250–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/15358593.2020.1778067

Halim, M., Ruble, D., Tamis-LeMonda, C., & Shrout, P. E. (2013). Rigidity in gender-typed behaviors in early childhood: A longitudinal study of ethnic minority children. Child Development, 84 , 1269–1284. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12057

Halliwell, E., Dittmar, H., & Orsborn, A. (2007). The effects of exposure to muscular male models among men: Exploring the moderating role of gym use and exercise motivation. Body Image, 4 (3), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.04.006

Harvey, J., & Manusov, V. (2020). Rapping about rap: Parental mediation of gender-stereotyped media content. Marriage & Family Review, 56 (3), 264–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2020.1712303

Harris, R. J., Cady, E. T., & Barlett, C. P. (2007). Media. In F. T. Durso, R. S. Nickerson, S. T. Dumais, S. Lewandowsky, & T. J. Perfect (Eds.), Handbook of applied cognition (pp. 659–681). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470713181.ch25

Hearn, J. (2004). From hegemonic masculinity to the hegemony of men. Feminist Theory, 5 (1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700104040813

Huesmann, L. R., Moise-Titus, J., Podolski, C., & Eron, L. D. (2003). Longitudinal relations between children’s exposure to TV violence and their aggressive and violent behavior in young adulthood: 1977–1992. Developmental Psychology, 39 (2), 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.2.201

Hust, S. T. (2006). From sports heroes and jackasses to sex in the city: Boys’ use of the media in construction of masculinities. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A, 67 , 18.

Javors, I. (2004). Hip-hop culture: Images of gender and gender roles. Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association, 7 , 42.

Larsen, K. S., & Long, E. (1988). Attitudes toward sex-roles: Traditional or egalitarian? Sex Roles, 19 (1–2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00292459

Lennon, S. J., & Johnson, K. K. P. (2021). Men and muscularity research: A review. Fashion and Textiles , 8 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-021-00245-w

Leszczynski, J. P., & Strough, J. (2008). The contextual specificity of masculinity and femininity in early adolescence. Social Development, 17 (3), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00443.x

McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2003). Sociocultural influences on body image and body changes among adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Social Psychology, 143 , 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540309598428

McCreary, D. R., & Sasse, D. K. (2000). An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of American College Health, 48 , 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480009596271

Miller, M. K., Rauch, J. A., & Kaplan, T. (2016). Gender differences in movie superheroes’ roles, appearances, and violence. Ada: A Journal of Gender. New Media, and Technology , 10. https://doi.org/10.7264/N3HX19ZK

Mulgrew, K. E., & Cragg, D. N. (2015). Age differences in body image responses to idealized male figures in music television. Journal of Health Psychology, 22 (6), 811–822. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315616177

Mulgrew, K., & Volcevski-Kostas, D. (2012). Short term exposure to attractive and muscular singers in music video clips negatively affects men’s body image and mood. Body Image, 9 (4), 543–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.05.001

Muller, J. N., Moroco, A., Loloi, J., Portolese, A., Wakefield, B. H., King, T. S., & Olympia, R. (2020). Violence depicted in superhero-based films stratified by protagonist/antagonist and gender. Cureus, 12 (2), Article e6843. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.6843

Murnen, S. K., Smolak, L., Mills, J., & Good, L. (2003). Thin, sexy women and strong, muscular men: Grade-school children’s responses to objectified images of women and men. Sex Roles, 49 , 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025868320206

Muthén, B. O., Muthén, L. K., & Asparouhov, T. (2017). Regression and mediation analysis using Mplus . Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Pennell, H., & Behm-Morawitz, E. (2015). The empowering (super) heroine? The effects of sexualized female characters in superhero films on women. Sex Roles, 72 (5–6), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0455-3

Perry, D. G., Pauletti, R. E., & Cooper, P. J. (2019). Gender identity in childhood: A review of the literature. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43 (4), 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025418811129

Prusank, D. T. (2007). Masculinities in teen magazines: The good, the bad, and the ugly. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 15 , 160–177. https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.1502.160

Raabe, I. J., Boda, Z., & Stadtfeld, C. (2019). The social pipeline: How friend influence and peer exposure widen the STEM gender gap. Sociology of Education, 92 (2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040718824095

Reeser, T. W. (2015). Concepts of masculinity and masculinity studies. Configuring Masculinity in Theory and Literary Practice, 1 , 11–38. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004299009_003

Roberts, L., Stevens Aubrey, J., Terán, L., Dajches, L., & Ward, L. M. (2021). The super man: Examining associations between childhood superhero imaginative play and wishful identification and emerging adult men’s body image and gender beliefs. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 22 (2), 391–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000335

Rothmund, T., Gollwitzer, M., Bender, J., & Klimmt, C. (2014). Short- and long-term effects of video game violence on interpersonal trust. Media Psychology, 18 (1), 106–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.841526

Shawcroft, J., & Coyne, S. (2022). Does Thor ask Iron Man for help? Examining help-seeking behaviors in Marvel superheroes. Sex Roles . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01301-5

Silva, T. (2021). Masculinity attitudes across rural, suburban, and urban areas in the United States. Men and Masculinities . https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184x211017186

Sinclair, S., Nilsson, A., & Cederskär, E. (2019). Explaining gender-typed educational choice in adolescence: The role of social identity, self-concept, goals, grades, and interests. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110 , 54–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.007

Smolak, L., Levine, M. P., & Thompson, J. K. (2001). The use of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire with middle school boys and girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29 (2), 216–223. https://doi-org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1002/1098-108X(200103)29:2/216::AID-EAT1011/3.0.CO;2-V

Tajfel, H. (2010). Social stereotypes and social groups. In T. Postmes, & N. R. Branscombe (Eds.), Rediscovering social identity (Key readings in social psychology) (1st ed., pp. 191–206). Psychology Press.

Thompson, T. L., & Zerbinos, E. (1997). Television cartoons: Do children notice it’s a boy’s world. Sex Roles, 37 , 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025657508010

Ward, L. M. (2002). Does television exposure affect emerging adults’ attitudes and assumptions about sexual relationships? Correlational and experimental confirmation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014068031532

Watson, A. (2021, February 12). Superhero movies - statistics & facts . Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/4741/superhero-movies/

Young, A. F., Gabriel, S., & Hollar, J. L. (2013). Batman to the rescue! The protective effects of parasocial relationships with muscular superheroes on men’s body image. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49 (1), 173–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.08.003

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Women’s Research Initiative at BYU for financially supporting this project. We would also like to thank all the student research assistants for their help throughout the project.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Family Life, Brigham Young University, JFSB 2086C, Provo, UT, 84602, USA

Sarah Coyne, Jane Shawcroft, Haley Graver, Matthew Siufanua & Hailey G. Holmgren

Linfield College, McMinnville, OR, USA

Jennifer Ruh Linder

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author