Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 28 February 2018

- Correction 16 March 2018

How to write a first-class paper

- Virginia Gewin 0

Virginia Gewin is a freelance writer in Portland, Oregon.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Manuscripts may have a rigidly defined structure, but there’s still room to tell a compelling story — one that clearly communicates the science and is a pleasure to read. Scientist-authors and editors debate the importance and meaning of creativity and offer tips on how to write a top paper.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 555 , 129-130 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02404-4

Interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 16 March 2018 : This article should have made clear that Altmetric is part of Digital Science, a company owned by Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, which is also the majority shareholder in Nature’s publisher, Springer Nature. Nature Research Editing Services is also owned by Springer Nature.

Related Articles

Want to make a difference? Try working at an environmental non-profit organization

Career Feature 26 APR 24

Scientists urged to collect royalties from the ‘magic money tree’

Career Feature 25 APR 24

NIH pay rise for postdocs and PhD students could have US ripple effect

News 25 APR 24

How reliable is this research? Tool flags papers discussed on PubPeer

News 29 APR 24

Algorithm ranks peer reviewers by reputation — but critics warn of bias

Nature Index 25 APR 24

W2 Professorship with tenure track to W3 in Animal Husbandry (f/m/d)

The Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Göttingen invites applications for a temporary professorship with civil servant status (g...

Göttingen (Stadt), Niedersachsen (DE)

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

W1 professorship for „Tissue Aspects of Immunity and Inflammation“

Kiel University (CAU) and the University of Lübeck (UzL) are striving to increase the proportion of qualified female scientists in research and tea...

University of Luebeck

W1 professorship for "Bioinformatics and artificial intelligence that preserve privacy"

Kiel, Schleswig-Holstein (DE)

Universität Kiel - Medizinische Fakultät

W1 professorship for "Central Metabolic Inflammation“

W1 professorship for "Congenital and adaptive lymphocyte regulation"

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Research Methodology and Scientific Writing

- © 2021

- C. George Thomas 0

Kerala Agricultural University, Thrissur, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Provides tips to improve the writing skills for research students

- Deals with most interdisciplinary fields in Research such as Problems, Writing Proposals, Funding, Selecting Designs, Literature and Review, Collection of Data and Analysis, and Preparation of Thesis

- Discusses the latest on the use of information technology in retrieving and managing information

103k Accesses

24 Citations

155 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (24 chapters)

Front matter, research: the search for knowledge.

C. George Thomas

Philosophy of Research

Approaches to research, major research methods, experimental research, collection and analysis of data, planning and writing a research proposal, publications and the library, academic databases, the literature review, preparation of research papers and other articles, the structure of a thesis, tables and illustrations, reasoning in research, references: how to cite and list correctly, improve your writing skills, use appropriate words and phrases, punctuation marks and abbreviations, units and numbers.

- Research Problems

- Writing Proposals

- Selecting Designs

- Literature and Review

- Collection of Data and Analysis

- Preparation of Thesis

About this book

Authors and affiliations, about the author, bibliographic information.

Book Title : Research Methodology and Scientific Writing

Authors : C. George Thomas

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64865-7

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Education , Education (R0)

Copyright Information : The Author(s) 2021

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-030-64864-0 Published: 25 February 2021

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-64867-1 Published: 25 February 2022

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-64865-7 Published: 24 February 2021

Edition Number : 2

Number of Pages : XVII, 620

Number of Illustrations : 25 b/w illustrations

Topics : Engineering/Technology Education , Writing Skills , Thesis and Dissertation

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Top Science News

Latest top headlines.

- Immune System

- Hormone Disorders

- Behavioral Science

- Heart Disease

- Stroke Prevention

- Liver Disease

- Nervous System

- Astrophysics

- Asteroids, Comets and Meteors

- Solar Flare

- Electronics

- Engineering and Construction

- Black Holes

- Albert Einstein

- Anthropology

- Human Evolution

- Early Humans

- Food and Agriculture

- Promising Experimental Type 1 Diabetes Drug

- Mice Think Like Babies

- Advance in Heart Regenerative Therapy

- Food in Sight? The Liver Is Ready!

Top Physical/Tech

- Unexpected Differences in Binary Stars: Origin

- Asteroid Ryugu and Interplanetary Space

- New Circuit Boards Can Be Repeatedly Recycled

- Collisions of Neutron Stars and Black Holes

Top Environment

- Long Snouts Protect Foxes Diving Into Snow

- Giant, Prehistoric Salmon Had Tusk-Like Teeth

- Plants On the Menu of Ancient Hunter-Gatherers

- Flexitarian: Invasive Species With Veggies

Health News

Latest health headlines.

- Infectious Diseases

- COVID and SARS

- Chronic Illness

- Today's Healthcare

- Lung Cancer

- Psychedelic Drugs

- Mental Health

- Brain Tumor

- Brain Injury

- Down Syndrome

- Gene Therapy

- Birth Defects

- Multiple Sclerosis Research

- Healthy Aging

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Cholesterol

- Learning Disorders

- Infant's Health

- Breastfeeding

- Diseases and Conditions

- Prostate Cancer

Health & Medicine

- Immune Key to Chronic Viral Infections

- Long COVID: Telltale Traces in Blood

- Severe COVID: Persistent Health Problems

- Unexpected Cells in Lung: Severe COVID

Mind & Brain

- Psychedelic Therapy: Clinician-Patient Bond

- Senescence: Neurons Re-Entering Cell Cycle

- Gene-Based Therapy: Timothy Syndrome

- Immigrants to Canada and MS Risk

Living Well

- People With Rare Longevity Mutation

- Educational Intervention That Works

- AI Can Assess How Well Newborns Nurse

- Keto Diet Reducing Prostate Cancer

Physical/Tech News

Latest physical/tech headlines.

- Virtual Reality

- Virtual Environment

- Computer Modeling

- Organic Chemistry

- Nature of Water

- Civil Engineering

- Severe Weather

- Materials Science

- Wind Energy

- Geomagnetic Storms

- Solar System

- Extrasolar Planets

- Medical Imaging

- Medical Devices

- Medical Topics

- Computer Graphics

- Neural Interfaces

- Computational Biology

- Alzheimer's

- Alzheimer's Research

- Evolutionary Biology

- Microbiology

Matter & Energy

- New Way to Instruct Dance in Virtual Reality

- A Shortcut for Drug Discovery

- Hurricane Ian's Aftermath

- Speeding Up Spectroscopic Analysis

Space & Time

- Toward Unification of Turbulence Framework

- Oldest Evidence of Earth's Magnetic Field

- Eruption of Mega-Magnetic Star

- To Find Life in the Universe, View Deadly Venus

Computers & Math

- Deep Tissue Imaging During Surgery

- Barcodes Expand Range of Sensor

- New Details of Peptide Structures

- Surprising Pattern in Yeast Study

Environment News

Latest environment headlines.

- Microbes and More

- New Species

- Exotic Species

- Environmental Awareness

- Veterinary Medicine

- Energy and the Environment

- Energy Issues

- Ancient Civilizations

- Endangered Plants

- Epigenetics

- Origin of Life

- Biochemistry

Plants & Animals

- Phage-Bacterial Arms Race

- Hornets Found to Be Primary Pollinators

- Alternative to Antibiotics Produced by Bacteria

- Lionfish Invasion in the Mediterranean Sea

Earth & Climate

- Reforesting in a Climate-Friendly Way

- Medium-Sized Pooches: Risk of Cancer

- Energy Trades Help Resolve Nile Conflict

- Ancient Maya Blessed Their Ballcourts

Fossils & Ruins

- Bioluminescence in Animals 540 Million Years Ago

- Father's Lineage: Loss of Y-Chromosome Diversity

- Saving Old Books Using Gluten-Free Glues

- Evolution of Gliding in Marsupials

Society/Education News

Latest society/education headlines.

- Public Health

- Transportation Issues

- Educational Technology

- Health Policy

- Retail and Services

- Markets and Finance

- STEM Education

- Intelligence

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Child Development

- K-12 Education

- Infant and Preschool Learning

- Language Acquisition

- Sustainability

- Educational Policy

- Mathematics

- Environmental Policies

- Land Management

Science & Society

- Study On Inappropriate Use of Antibiotics

- Child Pedestrians, Self-Driving Vehicles

- Location, Location, Location

- AI Use in Customer Service Centers

Education & Learning

- Pupils Enlarge When People Focus On Tasks

- Synchrony Between Parents and Children

- Evolving Attitudes of Gen X Toward Evolution

- Talk to Your Baby: It Matters

Business & Industry

- Pulling Power of Renewables

- Can AI Simulate Multidisciplinary Workshops?

- New Sensing Checks Overhaul Manufacturing

- Sustainability in Agricultural Trade

- T. Rex Not as Smart as Previously Claimed

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat, about this site.

ScienceDaily features breaking news about the latest discoveries in science, health, the environment, technology, and more -- from leading universities, scientific journals, and research organizations.

Visitors can browse more than 500 individual topics, grouped into 12 main sections (listed under the top navigational menu), covering: the medical sciences and health; physical sciences and technology; biological sciences and the environment; and social sciences, business and education. Headlines and summaries of relevant news stories are provided on each topic page.

Stories are posted daily, selected from press materials provided by hundreds of sources from around the world. Links to sources and relevant journal citations (where available) are included at the end of each post.

For more information about ScienceDaily, please consult the links listed at the bottom of each page.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Can Commun Dis Rep

- v.43(9); 2017 Sep 7

Scientific writing

A guide to publishing scientific research in the health sciences.

1 Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

2 School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON

4 Injury Prevention Research Center, Shantou University Medical College, Shantou, China

Effective communication of scientific research is critical to advancing science and optimizing the impact of one’s professional work. This article provides a guide on preparing scientific manuscripts for publication in the health sciences. It is geared to health professionals who are starting to report their findings in peer-reviewed journals or who would like to refresh their knowledge in this area. It identifies five key steps. First, adopt best practices in scientific publications, including collaborative writing and ethical reporting. Second, strategically position your manuscript before you start to write. This is done by identifying your target audience, choosing three to five journals that reach your target audience and then learning about the journal requirements. Third, create the first draft of your manuscript by developing a logical, concise and compelling storyline based on the journal requirements and the established structure for scientific manuscripts. Fourth, refine the manuscript by coordinating the input from your co-authors and applying good composition and clear writing principles. The final version of the manuscript needs to meet editorial requirements and be approved by all authors prior to submission. Fifth, once submitted, be prepared for revision. Rejection is common; if you receive feedback, consider revising the paper before submitting it to another journal. If the journal is interested, address all the requested revisions. Scientific articles that have high impact are not only good science; they are also highly readable and the result of a collective and often synergistic effort.

Introduction

The publication of the findings of scientific research is important for two reasons. First, the progression of science depends on the publication of research findings in the peer-reviewed literature. Second, the publication of research is important for career development. The old dictum “publish or perish” suggests the critical role publishing research has, especially for those in academia. The newer version, “publish and flourish”, suggests that publishing solid scientific research is good for individual researchers and good for the scientific community. With good research, there is the potential for everyone to be better off.

The publication of scientific work is not easy. There are many books on how to write a scientific article ( 1 - 5 ); however, the level of detail may be overwhelming and there is a tendency to focus more on the technical aspects, such as the structure of a scientific manuscript and what to include in each section, and less on the process aspects, such as what constitutes authorship and how to choose the most appropriate journal. There is a need for a basic overview for those who would like to start publishing or refresh their knowledge in this area. The objective of this article is to provide health professionals with an overview on how to prepare manuscripts for publication.

Adopt best practices in scientific publications

Anyone who would like to author scientific publications should know about these two best practices before they begin: work collaboratively and observe ethical reporting practices.

Practice collaborative writing

Research and scientific publishing are collective enterprises that call for collaboration as a best practice. Research usually involves a research team. New research projects build on previous research done by others. It involves input from peers on both protocol development before the research is done, as well as the review of manuscripts once the research is completed. The Cochrane Collaboration is one important example of this ( 6 ). To optimize the success of your research team, cultivate strong interpersonal skills and choose your collaborators wisely. Areas to consider when you are choosing with whom to work include such things as collaborator availability, similar research interests, track record and personal suitability.

Given that a scientific publication is meant to contribute to knowledge, a good research question is essential, as is identifying the optimal scientific method to answer that question and observing ethical practices in the conduct of your research.

Once these items have been addressed, what do you need to know before you start to write?

Observe ethical reporting practices

The ethics of scientific publications can be summarized by two best practices: complete and accurate reporting and appropriate attribution of everyone’s contributions ( 7 ).

Ensure complete and accurate reporting

Unethical scientific publication practices include incomplete reporting, the reporting of fraudulent data, plagiarism, duplicate publication and overlapping publications. Some people consider failure to publish the results of clinical trials as unethical ( 8 ), as it can create bias in the published record. Incomplete reporting can include selective reporting of findings or not reporting at all. It is important to report negative data, or any unexpected finding.

Falsification or fabrication of data is the most obvious breach of research ethics. One example is the fraudulent study linking autism to vaccine ( 9 ), which caused untold harm by undermining public confidence in routine childhood vaccines.

Plagiarism must be carefully avoided. Incorporating others’ ideas or research results into any manuscript you write needs to be done with appropriate referencing. Journal editors routinely check manuscripts with antiplagiarism software before determining a manuscript’s appropriateness for peer review. Free software programs are available for authors to check for inadvertent duplication of content such as CopyScape, DupliChecker, Plagiarisma, Plagium, Search Engine Reports, SEOTools, Site Liner and Unplag.

Duplicate publication is publishing an article that is the same or overlaps substantially with another article by the author or publisher ( 8 ). It is considered redundant, and may result in double-counting of data. This is to be distinguished from co-publication, which is when the same article is published in more than one journal at approximately the same time to increase reach to different disciplines ( 8 ). It meets specific criteria and is done with complete transparency.

Overlapping publication is a variant of duplicate publication. It typically occurs with multi-centre trials and is characterized by publications from single centres, several centres as well as all centres. This is considered unethical as it can lead to double-counting and distorts the perception of the weight of the evidence ( 10 ). It may be appropriate to have more than one publication come from a multi-centre trial, but this is usually to address secondary outcomes. Secondary publications should cite the primary analysis and all publications of trials should identify the trial registration number ( 8 ).

Give appropriate attribution

It is important to acknowledge the work of everyone who contributed to a scientific publication. Central to ethical publication is appropriate authorship. A best practice is to identify the role of each author. Authorship has been defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) as those who meet all of the following four criteria: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or to the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work; drafting the initial manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved ( 11 ).

Of note, the collection of data or the development of software for a study are not criteria for authorship, nor is securing research funding; however, these are important contributions that should be acknowledged—either in the Acknowledgements section or, if there is one, in the Contributors section. It is best practice to ensure everyone mentioned in an Acknowledgements or Contributors section is aware he/she has been identified, and is in agreement with being identified. Contractors paid to perform parts of a study (e.g., laboratory testing, software development or drafting the manuscript) are often, by definition, not authors but still merit being identified in the Acknowledgements or Contributors section.

Some unethical practices in authorship include guest authorship and ghost authorship. Guest authorship is including someone as an author who does not meet the ICMJE criteria and ghost authorship is excluding someone as an author who does meet the ICMJE criteria. Basically, ethical attribution is all about transparency.

There can be a lot of debate on the sequencing of authors. The ordering of authors differs by discipline ( 12 ). In the health sciences, the first author has the most weight; the final author also carries weight as this is often the principal or most senior investigator. In contrast, in economics, authors are usually listed alphabetically, implying equal contribution to the research work. It is useful to discuss authorship early in the manuscript planning process, and then again near the completion of the manuscript. This discussion should include an assessment of authorship against the ICMJE criteria and consideration of authorship sequence, which may change over time if there were changes in the level of input from what was originally planned.

Position your manuscript

Once your research is completed, you need to identify appropriate journals for publication. Not every manuscript can or should be published in a prestigious, high-impact journal. People can waste a lot of time and effort sending manuscripts to journals that will promptly send back a polite rejection letter, or will keep it for several months before declining it, based on the peer review. So how do you choose which journal to submit to? Discuss with your co-researchers or peers: Who is the target audience? Who will want to know about this research? What is the best journal to reach that audience? And what are those journals’ specific requirements for manuscript submissions?

Identify your target audience

Before writing up results of your study, think about your potential readers. Are your research findings most appropriate for a general readership or a specialty group? This affects the choice of journal for submission, and the writing style you adopt for the manuscript.

Choose three to five journals

Based on your target readership, develop a list of three to five journals, and then order by journal impact factor. The impact factor is the average number of citations per article published in that journal, based on the performance in the previous two years ( 13 ). Submit your manuscript to one journal at a time, starting from the top of the list. If you receive a rejection letter from your “Plan A” journal, you have a ready “Plan B” journal to submit to right away. This avoids having the rejected manuscript languish on your desk.

Learn about the journal requirements

Every journal has instructions for authors that are listed online. These instructions describe the types of articles that the journal publishes and provides specific advice about format, word length, as well as what needs to be included in a cover letter at the time of submission. Consult some past issues of the targeted journals to see examples of the different types of articles that are published.

Create the first draft

Now that you have identified your target audience, what journal you are targeting first, and what its requirements are, you are ready to create the first draft. To begin you want to develop a high-level summary that establishes a logical, compelling storyline that follows the established structure for a scientific manuscript. Then, before you start to write the text, check for any reporting guides for the type of study you have done to ensure you address any specific reporting requirements.

There is a common misconception that scientific publications are simply dispassionate reports of the methods and results of research. But consider this: There are more than 30,000 biomedical journals ( 14 ). We are living in an age of information overload, so people become very selective in what they read and ask themselves “Is this important for me to read?” The objective reporting of research findings is necessary, but not sufficient. Effective authors will also provide an appropriate context and present their work in such a way that readers find it interesting and easy to understand. The sections that follow identify several ways to best present the context, data and implications of your work.

Develop a compelling storyline

The use of the term storyline here does not mean you endeavour to entertain the reader. It is how you “present your case” in the court of scientific opinion. It maps on to the basic structure of scientific articles and includes the rationale for the study, the research question, how that question was addressed, what was found and why these findings are important ( 3 ). After working for months (and sometimes years) on a research project, it is easy to get lost in the details. Establishing a clear, logical underlying structure to your scientific manuscript from the outset not only helps to avoid going off on tangents, it also vastly increases its readability. The abstract is an excellent place to set out the storyline of your manuscript. You want to respond to the questions: What is this research about? (background and objective); What did you do to answer your research question? (methods); What did you find? (results); and What are the implications and next steps? (discussion and conclusion). Then, much like establishing the theme, each section is developed in the manuscript. A well-written abstract gives readers a “road map”; after reading it they will know what you will be covering in the article.

One way to strengthen the logic of your manuscript is to use the same terms and the same sequencing of information in each section. For example, if your research objective was to assess acceptability and adherence to a treatment regimen, what you do not want to do is describe the willingness to start a treatment in the Introduction, note how you measured compliance and adherence in the Methods and then describe how many people followed the treatment regime after agreeing to start it in the Results. If your research objective is to assess acceptability and adherence, define acceptability and then adherence in the Introduction, identify how you measured acceptance and then adherence in the Methods, and describe your findings for acceptance and then adherence in the Results. When you use the same terms in the same sequence in the Introduction, Methods and Results sections, it is much easier for the reader to quickly grasp what you did and what was found.

In addition, there are several writing techniques that help make your manuscript more compelling to engage the reader. The first is to have “a hook”, or interesting start that draws the reader in. Titles can be a hook; for example, a recent article from the New England Journal of Medicine was entitled: “The Other Victims of the Opioid Epidemic” ( 15 ). It might catch your attention, as you immediately ask yourself “Who are the victims and who are the other victims?” A compelling title may pose a question that motivates people to read the article: “Can scientists and policymakers work together?” ( 16 ). Readers are also engaged by the first sentence of the abstract; for example: “The emergence and prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria are an increasing cause of death worldwide, resulting in a global call to action.” ( 17 ). This is a good first sentence as it gives a sense of urgency and makes the reader curious about what the call to action is. One must be careful to not sensationalize, but when there is an urgent health issue, it is important to describe why we need to be aware of it and change what we do if necessary.

Check for reporting guides

As a final step before starting to write the manuscript in full, check if there are specific reporting requirements for the type of research you have done; for example, if you have done an experimental study, you will need to mention research ethics board approval and informed consent ( 18 ). If you have done a systematic review, include a flow diagram of the included and excluded studies ( 19 ). Some journals provide author checklists to identify what is important to include in different sections for different types of studies ( 20 , 21 ). The Equator Network (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research) brings together a number of reporting guidelines and is a useful resource ( 22 ).

Use the IMRAD approach

When you start to write the text, use the classic structure of a scientific article: Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion, which is often referred to by the acronym IMRAD. But, rather than writing down everything you know that relates to your study, use each section strategically to tell the story of your research.

A good Introduction section has the structure of an inverted triangle. This means that you start with a broad topic, and then narrow down the readers’ focus in logical steps until you arrive at your research question. This can be facilitated by answering the following questions:

- What is the issue?

- Why is it important?

- What do we know to date?

- What are the gaps in our knowledge?

- What is the research question that will address this gap?

- What was the objective of the research?

At this point, the reader will want to know “So what happened?” and they will keep reading. The summary of the literature is done in the present tense, as it represents generally accepted facts and principles. Define all abbreviations on first use but use only commonly-accepted ones. Too many abbreviations decrease readability. The introduction is described in the present tense (as it describes established facts).

The Methods section describes how the study was conducted. It is important to explain how the methods address the research objective. Give enough detail so that others can duplicate your study, if needed, to confirm that your results are consistent and reliable. It is useful to have subtitles. For a clinical trial, for example, this could include study population, intervention, outcome measures and analysis. Avoid the temptation to provide results in the Methods section. For example, the sampling methodology belongs to the Methods section, the response rate of the study belongs in the Results section. The Methods section is described in the past tense (as it describes what you did).

The Results section describes what was found in the study (in the same sequence of information established in the Introduction and the Methods sections). Avoid the temptation to discuss or analyze results in the Results section. For example, you can state: “there were more men than women in this study”, but exploring the reason for this belongs in the Discussion section. Results are described in the past tense (as they describe what you found).

Many readers find the Discussion section to be the most interesting part of the article. The first sentence is an opportunity to summarize the most important findings of your study; for example: “Surveillance data from four Nordic countries suggested that at least 25% of gonorrhea infections were related to travel” ( 23 ). Interpret your findings in light of possible biases or sources of errors. Then it is important to consider both the strengths and weaknesses of your study; compare it to other studies with similar or different findings, consider the implications and identify the next steps. The Discussion section is an opportunity to situate your findings within the larger body of knowledge and to consider what is needed to further advance scientific understanding. The discussion is described in past, present or future tense depending on context.

Develop tables and figures to highlight key findings

There are two best practices to consider when creating tables and figures. First, to address the classic evidence-based medicine question—Are these results applicable to my patient population?—you need to describe your study population ( 24 ). The first table in a clinical study, for example, often compares the demographic characteristics of the research subjects to what is known about the study population. This helps readers assess how representative the study sample was. Second, use tables and figures to highlight your key findings. Resist the temptation to present all the data you have in tables and figures which may overwhelm the reader. You want to keep the focus on the study objective and the answer to your research question.

Tables are useful to present large quantities of data and figures are preferred to show trends over time. Titles of tables and figures should be able to “stand alone”; i.e., they are self-explanatory and complete. To be complete, include the study population, type of data presented and dates of the study. In tables, ensure each column has a heading. Make sure all data is validated and that all research subjects are accounted for (i.e., the percentages add up to 100%). Further resources on preparation of tables and figures are available ( 25 , 26 ). See Table 1 for some highlights of the “Dos and Don’ts” when writing scientific manuscripts.

Refine the manuscript

Most manuscripts are a team effort, so once a manuscript has been drafted, it then needs to be circulated for input by all the co-authors. Consider your own internal peer review process and then refine the manuscript for clarity before submitting it to a peer-reviewed journal. If your first language is not English, consider having the manuscript copy-edited before you submit it to a journal.

Circulate to co-authors and peers

Each research team works out their own way of writing and revising. Usually the first author develops the first draft, and then sends to other authors to provide comments (usually using the tracked changes function). The first author will then incorporate comments and produce a second draft for a second round of comments. This process continues until all authors agree on the structure and wording of the manuscript. It is also possible to have different authors draft different sections of the manuscript, once there has been consensus on the storyline and the structure. A common challenge with circulating drafts of a manuscript is version control. You may want to have only one author working on a draft at a time. If there is simultaneous feedback from multiple authors, they should all be sent to the first author by a set due date. You may also want to conduct your own internal peer review process. After being steeped in a project for months and a manuscript for weeks, it is easy to lose perspective. An unblinded internal peer review may help strengthen your manuscript before undergoing the blind external peer review that is conducted by the editorial office of scientific journals.

Apply clear writing principles

The hallmark of good scientific writing is precision and clarity ( 5 ). Based on the classic, The Elements of Style , here are some tips that will help bring clarity to your writing ( 27 ). Check the first sentence of each paragraph. These should signal to the reader the progression of the logic of your manuscript and introduce what the paragraph contains. When appropriate, use the active voice. To say “We developed a protocol” is more engaging than the passive voice: “A protocol was developed”. Edit out needless words, such as “as noted above”. When possible, use parallel construction or the repetition of a grammatical form within a sentence. For example, the phrase “Children aged 4–6 years should be given vaccine A; the administration of vaccine B is advised for those who are 13–18 years old” can be made clearer using parallel construction: “Children aged 4–6 years should be given vaccine A; adolescents aged 13–18 should be given vaccine B”. Make definitive assertions; arouse interest of the reader by reporting the details that matter. In addition, you do not want to be overly complex; resources are available to help describe things in plain language ( 28 ).

Submit and be ready to revise

Once all the authors sign off on the final version, submit to your journal of choice with a short cover letter noting that your manuscript has not been published previously and is not under consideration by any other journal. It is also useful to identify why your manuscript is relevant to the journal’s readership. This may influence the editor’s decision on whether to send your manuscript for external peer review.

Once the manuscript is submitted, brace yourself for a number of possible responses. You may receive a polite rejection letter. Or the Editor may have comments on the manuscript that need to be addressed before it is peer-reviewed. If this is the case, it is good to address these promptly. Another possibility is that the manuscript is peer-reviewed and then declined. There are two reasons why you should carefully consider all the peer-reviewer comments, even though the journal is not interested in your manuscript. First, this is free advice, often from top-notch experts in the field, so why not use it to improve your success rate with another journal? Second, only a limited number of researchers participate in the journal peer review process. When you submit to a second journal, what you do not want to hear back is “I was the peer reviewer of this manuscript for another journal, and I see that none of my previous comments were considered by the authors”. If you do decide to revise the manuscript to address reviewer comments, do not forget to review the instructions for authors for the new journal and reformat as necessary. Finally, after peer-review has been completed, you may receive a tentative acceptance letter from the editor, accompanied by a request for minor revisions. Or you could receive a “reject and resubmit” letter, which means that extensive revisions are needed. In either case, it indicates an interest in a revised manuscript.

Requested revisions are usually discussed jointly among the co-authors until there is consensus on how to address them. Making the revisions can either be allocated among the authors, or coordinated through one person. Usually once the revisions are underway, they do not seem as formidable as they first appeared, and the manuscript ends up being stronger and clearer as a result. Once revised, do a final check of the abstract to ensure it still reflects the revised text. Again, sign-off is needed from all the authors before submitting the revised manuscript to the journal.

To advance science, research needs to be published. To optimize the chances of your research getting published and having an impact, it is important to demonstrate objectivity, and present your work in a way that is interesting and compelling. To do this you need clarity, logic and the use of rhetorical techniques to engage the reader in your research. This includes positioning your manuscript to reach your target audience, developing a logical, compelling storyline within the confines of the IMRAD structure, having an effective iterative approach among your co-authors to develop the manuscript and being ready to complete revisions to meet journal requirements.

Effective scientific writing rarely comes from innate talent. Writing is a skill that needs to be honed over one’s professional career. Cultivate an interest in what makes good writing. As you read other peoples’ work, ask yourself what makes some articles easier to read than others. Consider becoming a peer-reviewer for scientific journals to assess the manuscripts of others.

It is thoroughly satisfying to publish compelling research that influences people and makes a contribution to science. This is most often achieved through the synergy of collaboration with others and having a common goal of advancing the collective progression of science.

Authors’ statement

Both authors worked on the conception and design together, PH developed the first draft, both contributed to multiple drafts and signed off on the final version. Dr. Patricia Huston is the Editor-in-Chief of CCDR and recused herself from taking any editorial decisions on this manuscript. Decisions were taken by the Editorial Fellow, Toju Ogunremi, with the support of the Editorial Board member, Dr. Michel Deilgat.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Andrea Currie and Katie Rutledge-Taylor who developed the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Field Epidemiology writing curriculum. We had a number of interesting discussions on the art and science of scientific writing that informed this work, including the concept of the inverted triangle for the structure of an effective introduction.

Conflict of Interest: None.

Scientific Research and Essays

Subject Area and Category

- Agricultural and Biological Sciences (miscellaneous)

- Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology (miscellaneous)

- Engineering (miscellaneous)

- Medicine (miscellaneous)

- Physics and Astronomy (miscellaneous)

Academic Journals

Publication type

The set of journals have been ranked according to their SJR and divided into four equal groups, four quartiles. Q1 (green) comprises the quarter of the journals with the highest values, Q2 (yellow) the second highest values, Q3 (orange) the third highest values and Q4 (red) the lowest values.

The SJR is a size-independent prestige indicator that ranks journals by their 'average prestige per article'. It is based on the idea that 'all citations are not created equal'. SJR is a measure of scientific influence of journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where such citations come from It measures the scientific influence of the average article in a journal, it expresses how central to the global scientific discussion an average article of the journal is.

Evolution of the number of published documents. All types of documents are considered, including citable and non citable documents.

This indicator counts the number of citations received by documents from a journal and divides them by the total number of documents published in that journal. The chart shows the evolution of the average number of times documents published in a journal in the past two, three and four years have been cited in the current year. The two years line is equivalent to journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

Evolution of the total number of citations and journal's self-citations received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. Journal Self-citation is defined as the number of citation from a journal citing article to articles published by the same journal.

Evolution of the number of total citation per document and external citation per document (i.e. journal self-citations removed) received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. External citations are calculated by subtracting the number of self-citations from the total number of citations received by the journal’s documents.

International Collaboration accounts for the articles that have been produced by researchers from several countries. The chart shows the ratio of a journal's documents signed by researchers from more than one country; that is including more than one country address.

Not every article in a journal is considered primary research and therefore "citable", this chart shows the ratio of a journal's articles including substantial research (research articles, conference papers and reviews) in three year windows vs. those documents other than research articles, reviews and conference papers.

Ratio of a journal's items, grouped in three years windows, that have been cited at least once vs. those not cited during the following year.

Leave a comment

Name * Required

Email (will not be published) * Required

* Required Cancel

The users of Scimago Journal & Country Rank have the possibility to dialogue through comments linked to a specific journal. The purpose is to have a forum in which general doubts about the processes of publication in the journal, experiences and other issues derived from the publication of papers are resolved. For topics on particular articles, maintain the dialogue through the usual channels with your editor.

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2024. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

A Simple Act of Defiance Can Improve Science for Women

By Toby Kiers

Dr. Kiers is a professor of evolutionary biology at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam and the executive director of SPUN, a research organization that advocates the protection of mycorrhizal fungal communities.

They don’t tell you beforehand that it will be a choice between having a career in science or starting a family. But that’s the message I heard loud and clear 17 years ago, in my first job after completing my Ph.D. in evolutionary biology. During a routine departmental meeting, a senior academic announced that pregnant women were a financial drain on the department. I was sitting visibly pregnant in the front row. No one said anything.

I took a leave of absence when that child, my daughter, was born. Two years later, I had a son. That second pregnancy was a surprise, and I worried that taking another leave would sink my career. So I pressed on. When my son was barely 3 weeks old, I flew nine hours to a conference with him strapped to my chest. Before delivering my talk, I made a lame joke that the audience should forgive any “brain fog.” Afterward, an older woman pulled me aside and told me that being self-deprecating in public was a disservice to women scientists.

It felt like an impossible choice: to be a bad scientist or a bad mother.

The data suggests I wasn’t alone in feeling those pressures. A study published in 2019 found that more than 40 percent of female scientists in the United States leave full-time work in science after their first child. In 2016, men held about 70 percent of all research positions in science worldwide. Especially for field researchers like me, who collect data in remote and sometimes perilous locations, motherhood can feel at odds with a scientific career.

How have I addressed the problem? Through an act of academic defiance: I bring my kids with me on my scientific expeditions. It’s a form of rebellion that is available to mothers not just in the sciences but also in other disciplines that require site visits and field work, such as architecture and journalism. Bringing your kids to work with you doesn’t have to be something you do only once a year .

It started for me as a simple necessity. When my son was just under 2 and my daughter not yet 4, I took them on an expedition to the base of Mount Kenya in Africa, to study how fungi help trees defend themselves against the elephants and giraffes who feed on them. My son was still nursing, and I didn’t want to stop working. My husband, a poet, came along to stay with them at base camp.

As time went on, I began to embrace the decision to bring my kids with me on my expeditions, not as an exigency of parenting but as a kind of feminist act. When meeting other scientists in the field, the reaction was typically the same: They assumed my husband was leading the expedition. Once the facts were established, researchers were supportive and even willing to lend a hand.

Looking back at those expeditions now — after more than a dozen, in far-flung areas around the globe — I understand that bringing them into the field was more than a rebellion: Their presence on those trips also changed the way I do science, and for the better.

I started tasting soils in the field — a technique I now use to notice subtle differences across ecosystems — only after seeing my kids eat dirt. Children have an uncanny ability to make local friends quickly; many of those new friends have led me to obscure terrain and hidden fungal oases that I otherwise would never have come across. And my kids’ naïve minds routinely force me to rethink old assumptions by asking questions that are simultaneously absurd and profound. Can you taste clouds? Do fungi dream? How loud are our footsteps underground?

What can feel like an inconvenience is often a blessing in disguise. Children force the patience that scientific discovery demands. Last year, my kids and I traveled to Lesotho , in southern Africa. Collecting fungi in such a rugged landscape required horses, guides and months of precise planning. But my daughter caught the flu. Rather than mapping underground fungal life, we spent the week in a hut in a highland village with no running water or electricity, eating fermented sorghum. As the days ticked by, I began to panic, thinking of the fungi that would remain unsampled.

But one morning, as my daughter’s health improved, we were invited to cross a small mountain pass on horses. The local herder allowed me to collect dark soil among the agricultural ruins of his ancestral village. It was a type of soil I had never seen — with fungi that would have remained undescribed had we stayed on track. Thank you, chaos; thank you, kids.

Bringing my kids with me continues to challenge expectations, and not only among fellow scientists. In the summer of 2022, my kids and I embarked on an expedition in Italy to study fungi exposed to extreme heat and wildfire. Hiking across mountains with kids was hard and made even more arduous because a documentary film crew followed us. As we wrangled fungi in burn sites, the cameraman strategically positioned me for shots without my kids, presumably so the footage would look more “professional.”

Female scientists are right to fear being seen as unprofessional. How we talk, how we dress, is constantly under scrutiny — and so many of us mirror our male colleagues. Any deviation from that standard is often considered suspect. The primatologist Jane Goodall famously placed her young son in a cage so that he could safely join her in the field, and it is still a point of controversy, decades later.

At its core, feminism is about having the power to choose. For female scientists, this means having the ability to bring children into the field — or the full support to leave them at home. The pressure is acute because, as research shows, women on scientific teams are significantly less likely than men to be credited with authorship. So for me, it is crucial to keep collecting data with my own hands.

What do my kids make of all this? They both love and hate our expeditions. Frustrated by a grueling day of field work recently, my teenage daughter screamed at me, “You love science more than you love me!” In that moment, she — like so much of the scientific world — believed that the decision was binary: science or family. But by taking her with me into the field, I am relentlessly affirming that I won’t make that choice. My kids won’t make that choice either: They recently helped start a youth climate group to help protect soil fungi, including by organizing protests.

We are taught that good science requires detachment. But what if being a mother — with all the attachments that entails — allows you to explore different but equally fruitful scientific narratives? Last year, an article by the editor who oversees the Science journals argued that scientists should not be “afraid to acknowledge their humanity.” We should take that sound advice a step further and challenge the ideal of detachment. Perhaps by exposing our vulnerabilities — such as the children we are raising — we can change the system.

Toby Kiers ( @KiersToby ) is a professor of evolutionary biology at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam and the executive director of SPUN , a research organization that advocates for the protection of mycorrhizal fungal communities.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

How Pew Research Center will report on generations moving forward

Journalists, researchers and the public often look at society through the lens of generation, using terms like Millennial or Gen Z to describe groups of similarly aged people. This approach can help readers see themselves in the data and assess where we are and where we’re headed as a country.

Pew Research Center has been at the forefront of generational research over the years, telling the story of Millennials as they came of age politically and as they moved more firmly into adult life . In recent years, we’ve also been eager to learn about Gen Z as the leading edge of this generation moves into adulthood.

But generational research has become a crowded arena. The field has been flooded with content that’s often sold as research but is more like clickbait or marketing mythology. There’s also been a growing chorus of criticism about generational research and generational labels in particular.

Recently, as we were preparing to embark on a major research project related to Gen Z, we decided to take a step back and consider how we can study generations in a way that aligns with our values of accuracy, rigor and providing a foundation of facts that enriches the public dialogue.

A typical generation spans 15 to 18 years. As many critics of generational research point out, there is great diversity of thought, experience and behavior within generations.

We set out on a yearlong process of assessing the landscape of generational research. We spoke with experts from outside Pew Research Center, including those who have been publicly critical of our generational analysis, to get their take on the pros and cons of this type of work. We invested in methodological testing to determine whether we could compare findings from our earlier telephone surveys to the online ones we’re conducting now. And we experimented with higher-level statistical analyses that would allow us to isolate the effect of generation.

What emerged from this process was a set of clear guidelines that will help frame our approach going forward. Many of these are principles we’ve always adhered to , but others will require us to change the way we’ve been doing things in recent years.

Here’s a short overview of how we’ll approach generational research in the future:

We’ll only do generational analysis when we have historical data that allows us to compare generations at similar stages of life. When comparing generations, it’s crucial to control for age. In other words, researchers need to look at each generation or age cohort at a similar point in the life cycle. (“Age cohort” is a fancy way of referring to a group of people who were born around the same time.)

When doing this kind of research, the question isn’t whether young adults today are different from middle-aged or older adults today. The question is whether young adults today are different from young adults at some specific point in the past.

To answer this question, it’s necessary to have data that’s been collected over a considerable amount of time – think decades. Standard surveys don’t allow for this type of analysis. We can look at differences across age groups, but we can’t compare age groups over time.

Another complication is that the surveys we conducted 20 or 30 years ago aren’t usually comparable enough to the surveys we’re doing today. Our earlier surveys were done over the phone, and we’ve since transitioned to our nationally representative online survey panel , the American Trends Panel . Our internal testing showed that on many topics, respondents answer questions differently depending on the way they’re being interviewed. So we can’t use most of our surveys from the late 1980s and early 2000s to compare Gen Z with Millennials and Gen Xers at a similar stage of life.

This means that most generational analysis we do will use datasets that have employed similar methodologies over a long period of time, such as surveys from the U.S. Census Bureau. A good example is our 2020 report on Millennial families , which used census data going back to the late 1960s. The report showed that Millennials are marrying and forming families at a much different pace than the generations that came before them.

Even when we have historical data, we will attempt to control for other factors beyond age in making generational comparisons. If we accept that there are real differences across generations, we’re basically saying that people who were born around the same time share certain attitudes or beliefs – and that their views have been influenced by external forces that uniquely shaped them during their formative years. Those forces may have been social changes, economic circumstances, technological advances or political movements.

When we see that younger adults have different views than their older counterparts, it may be driven by their demographic traits rather than the fact that they belong to a particular generation.

The tricky part is isolating those forces from events or circumstances that have affected all age groups, not just one generation. These are often called “period effects.” An example of a period effect is the Watergate scandal, which drove down trust in government among all age groups. Differences in trust across age groups in the wake of Watergate shouldn’t be attributed to the outsize impact that event had on one age group or another, because the change occurred across the board.

Changing demographics also may play a role in patterns that might at first seem like generational differences. We know that the United States has become more racially and ethnically diverse in recent decades, and that race and ethnicity are linked with certain key social and political views. When we see that younger adults have different views than their older counterparts, it may be driven by their demographic traits rather than the fact that they belong to a particular generation.

Controlling for these factors can involve complicated statistical analysis that helps determine whether the differences we see across age groups are indeed due to generation or not. This additional step adds rigor to the process. Unfortunately, it’s often absent from current discussions about Gen Z, Millennials and other generations.

When we can’t do generational analysis, we still see value in looking at differences by age and will do so where it makes sense. Age is one of the most common predictors of differences in attitudes and behaviors. And even if age gaps aren’t rooted in generational differences, they can still be illuminating. They help us understand how people across the age spectrum are responding to key trends, technological breakthroughs and historical events.

Each stage of life comes with a unique set of experiences. Young adults are often at the leading edge of changing attitudes on emerging social trends. Take views on same-sex marriage , for example, or attitudes about gender identity .

Many middle-aged adults, in turn, face the challenge of raising children while also providing care and support to their aging parents. And older adults have their own obstacles and opportunities. All of these stories – rooted in the life cycle, not in generations – are important and compelling, and we can tell them by analyzing our surveys at any given point in time.

When we do have the data to study groups of similarly aged people over time, we won’t always default to using the standard generational definitions and labels. While generational labels are simple and catchy, there are other ways to analyze age cohorts. For example, some observers have suggested grouping people by the decade in which they were born. This would create narrower cohorts in which the members may share more in common. People could also be grouped relative to their age during key historical events (such as the Great Recession or the COVID-19 pandemic) or technological innovations (like the invention of the iPhone).

By choosing not to use the standard generational labels when they’re not appropriate, we can avoid reinforcing harmful stereotypes or oversimplifying people’s complex lived experiences.

Existing generational definitions also may be too broad and arbitrary to capture differences that exist among narrower cohorts. A typical generation spans 15 to 18 years. As many critics of generational research point out, there is great diversity of thought, experience and behavior within generations. The key is to pick a lens that’s most appropriate for the research question that’s being studied. If we’re looking at political views and how they’ve shifted over time, for example, we might group people together according to the first presidential election in which they were eligible to vote.

With these considerations in mind, our audiences should not expect to see a lot of new research coming out of Pew Research Center that uses the generational lens. We’ll only talk about generations when it adds value, advances important national debates and highlights meaningful societal trends.

- Age & Generations

- Demographic Research

- Generation X

- Generation Z

- Generations

- Greatest Generation

- Methodological Research

- Millennials

- Silent Generation

Kim Parker is director of social trends research at Pew Research Center

How Teens and Parents Approach Screen Time

Who are you the art and science of measuring identity, u.s. centenarian population is projected to quadruple over the next 30 years, older workers are growing in number and earning higher wages, teens, social media and technology 2023, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Office of Undergraduate Research

How do ssris interact with maternal physiology and offspring neurodevelopment.

Project and Position Details We are looking for an undergraduate or post-graduate volunteer laboratory intern to help complete projects related to the prenatal and gestational impacts of SSRI use. Students will be exposed to a variety of wet lab and in silico techniques, including but not limited to evaluating maternal care and depression-like behaviors in mice, brain and placenta dissections and microdissections, animal necropsy, working with clinical samples (human placenta, maternal plasma, cord blood), and molecular techniques (qPCR, ELISA, immunohistochemistry, metabolomics). Students will have opportunities for data analysis, manuscript writing, and presenting. The Santillan Lab is a welcoming, positive environment that encourages creativity, teamwork, and scientific development! Past lab members have gone on to graduate school, medical school, nursing school, dental school, and related training programs.

Qualifications Some undergraduate education or more

Time Commitment 10 hrs/week minimum

Compensation Volunteer Academic Credit

Start Date Immediate, over the summer

Project Duration Ongoing or potential to be a continuous position

How to Apply Email [email protected].

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Professor Emeritus Bernhardt Wuensch, crystallographer and esteemed educator, dies at 90

Press contact :.

Previous image Next image

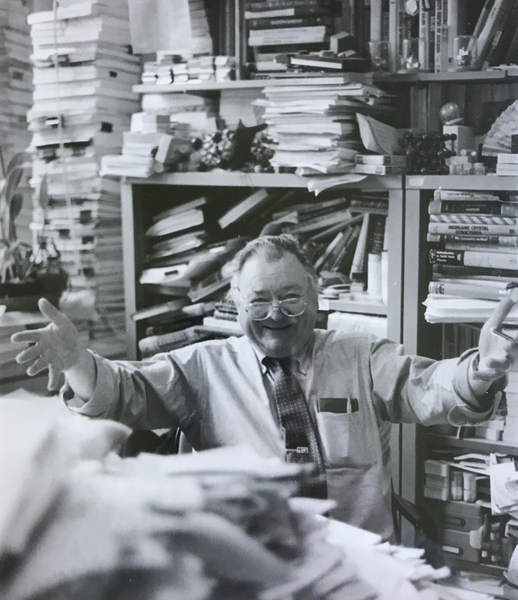

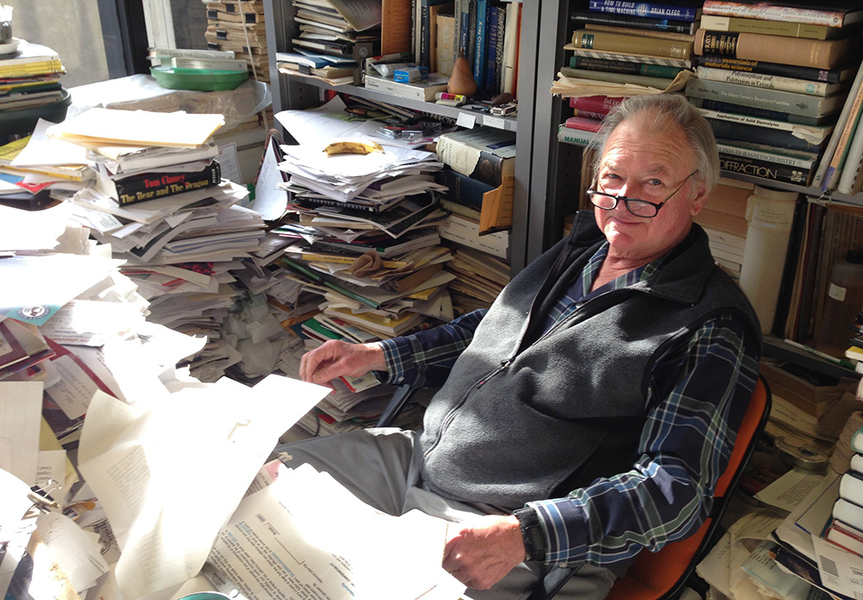

MIT Professor Emeritus Bernhardt Wuensch ’55, SM ’57, PhD ’63, a crystallographer and beloved teacher whose warmth and dedication to ensuring his students mastered the complexities of a precise science matched the analytical rigor he applied to the study of crystals, died this month in Concord, Massachusetts. He was 90.

Remembered fondly for his fastidious attention to detail and his office stuffed with potted orchids and towers of papers, Wuensch was an expert in X-ray crystallography, which involves shooting X-ray beams at crystalline materials to determine their underlying structure. He did pioneering work in solid-state ionics, investigating the movement of charged particles in solids that underpins technologies critical for batteries, fuel cells, and sensors. In education, he carried out a major overhaul of the curriculum in what is today MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering (DMSE).

Despite his wide-ranging research and teaching interests, colleagues and students said, he was a perfectionist who favored quality over quantity.

“All the work he did, he wasn’t in a hurry to get a lot of stuff done,” says DMSE’s Professor Harry Tuller. “But what he did, he wanted to ensure was correct and proper, and that was characteristic of his research.”

Born in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1933, Wuensch first arrived at MIT as a first-year undergraduate in the 1950s. He earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in physics before switching to crystallography and earning a PhD from what was then the Department of Geology (now Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences). He joined the faculty of the Department of Metallurgy in 1964 and saw its name change twice over his 46 years, retiring from DMSE in 2011.

As a professor of ceramics, Wuensch was a part of the 20th-century shift from a traditional focus on metals and mining to a broader class of materials that included polymers, ceramics, semiconductors, and biomaterials. In a 1973 letter supporting his promotion to full professor, then-department head Walter Owen credits Wuensch for contributing to “a completely new approach to the teaching of the structure of materials.”

His research led to major advancements in understanding how atomic-level structures affect magnetic and electrical properties of materials. For example, Tuller says, he was one of the first to detail how the arrangement of atoms in fast-ion conductors — materials used in batteries, fuel cells, and other devices — influences their ability to swiftly conduct ions.

Wuensch was a leading light in other areas, including diffusion, the movement of ions in materials such as liquids or gases, and neutron diffraction, aiming neutrons at materials to collect information about their atomic and magnetic structure.

Tuller, a DMSE faculty member for 49 years, tapped Wuensch’s expertise to study zinc oxide, a material used to make varistors, semiconducting components that protect circuits from high-voltage surges of electricity. Together, Tuller and Wuensch found that in such materials ions move much more rapidly along the grain boundaries — the interfaces between the crystallites that make up these polycrystalline ceramic materials.

“It’s what happens at those grain boundaries that actually limits the power that would go through your computer during a voltage surge by instead short-circuiting the current through these devices,” Tuller says. He credited the partnership with Wuensch for the knowledge. “He was instrumental in helping us confirm that we could engineer those grain boundaries by taking advantage of the very rapid diffusivity of impurity elements along those boundaries.”

In recognition of his accomplishments, Wuensch was elected a fellow of the American Ceramics Society and the Mineralogical Society of America and belonged to other professional associations, including The Electrochemical Society and Materials Research Society. In 2003 he was awarded an honorary doctorate from South Korea’s Hanyang University for his work in crystallography and diffusion-related phenomena in ceramic materials.

“A great, great teacher”

Known as “Bernie” to friends and colleagues, Wuensch was equally at home in the laboratory and the classroom. “He instilled in several generations of young scientists this ability to think deeply, be very careful about their research, and be able to stand behind it,” Tuller says.

One of those scientists is Sossina Haile ’86, PhD ’92, the Walter P. Murphy Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at Northwestern University, a researcher of solid-state ionic materials who develops new types of fuel cells, devices that convert fuel into electricity.

Her introduction to Wuensch, in the 1980s, was his class 3.13 (Symmetry Theory). Haile was at first puzzled by the subject, the study of the symmetrical properties of crystals and their effects on material properties. The arrangements of atoms and molecules in a material is crucial for predicting how materials behave in different situations — whether they will be strong enough for certain uses, for example, or can conduct electricity — but to an undergraduate it was “a little esoteric.”

“I certainly remember thinking to myself, ‘What is this good for?’” Haile says with a laugh. She would later return to MIT as a PhD student working alongside Wuensch in his laboratory with a renewed perspective.

Previous item Next item

“He just made seemingly esoteric topics really interesting and was very astute in knowing whether or not a student understood.” Haile describes Wuensch’s articulate speech, “immaculate” handwriting, and detailed drawings of three-dimensional objects on the chalkboard. Haile notes that his sketches were so skillful that students felt disappointed when they looked at a figure they tried to copy in their notebooks.

“They couldn’t tell what it was,” Haile says. “It felt really clear during lecture, and it wasn’t clear afterwards because no one had a drawing as good as his.”

Carl Thompson, the Stavros V. Salapatas Professor in Materials Science and Engineering at DMSE, was another student of Wuensch’s who came away with a broadened outlook. In 3.13, Thompson recalls Wuensch asking students to look for symmetry outside of class, patterns in a brick wall or in subway station tiles. “He said, ‘This course will change the way you see the world,’ and it did. He was a great, great teacher.”

In a 2005 videorecorded session of 3.60 (Symmetry, Structure, and Tensor Properties of Materials), a graduate class that he taught for three decades, Wuensch writes his name on the board along with his telephone extension number, 6889, pointing out its rotational symmetry.

“You can pick it up, turn it head-over-heels by 180 degrees, and it’s mapped into coincidence with itself,” Wuensch said. “You might think I would have had to have fought for years to get it, an extension number like that, but no. It just happened to come my way.”

(The class can be watched in its entirety on MIT OpenCourseWare .)

Wuensch also had a whimsical sense of humor, which he often exercised in the margins of his students’ papers, Haile says. In a LinkedIn tribute to him, she recalled a time she sent him a research manuscript with figures that was missing Figure 5 but referred to it in the text, writing that it plotted conductivity versus temperature.

“Bernie noted that figures don’t plot; people do, and evidently Figure 5 was missing because ‘it was off plotting somewhere,’” Haile wrote.

Reflecting on Wuensch’s legacy in materials science and engineering, Haile says his knowledge of crystallography and the manual analysis and interpretation he did in his time was critical. Today, materials science students use crystallographic software that automates the algorithms and calculations.

“The current students don’t know that analysis but benefit from it because people like Bernie made sure it got into the common vernacular at the time when code was being put together,” Haile said.

A multifaceted tenure

Wuensch served DMSE and MIT in innumerable other ways, serving on departmental committees on curriculum development, graduate students, and policy, and on School of Engineering and Institute-level committees on education and foreign scholarships, among others. “He was always involved in any committee work he was asked to do,” Thompson says.

He was acting department head for six months starting in 1980, and in 1988-93 he was the director of the Center for Materials Science and Engineering, an earlier iteration of today’s Materials Research Center.

For all his contributions, there are few things Wuensch was better known for at MIT than his office in Building 13, which had shelves lined with multicolored crystal lattice models, representing the arrangements of atoms in materials, and orchids he took meticulous care of. And then there was the cityscape of papers, piled in heaps on the floor, on his desk, on pullout extensions. Thompson says walking into his office was like navigating a canyon.

“He had so many stacks of paper that he had no place to actually work at his desk, so he would put things on his lap — he would start writing on his lap,” Haile says. “I remember calling him at one point in time and talking to him, and I said, ‘Bernie, you’re writing this down on your lap, aren’t you?’ And he said, ‘In fact, yes, I am.’”