Healthcare utilisation: a mixed-method study among tea garden workers in Indian context

Journal of Health Research

ISSN : 2586-940X

Article publication date: 11 June 2021

Issue publication date: 27 September 2022

The study examined the utilisation patterns of healthcare services among tea garden workers and analysed the factors influencing utilisation in an Indian context.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors employed a mixed-method approach and an explanatory sequential design for the study. A survey was conducted in the beginning followed by in-depth interviews in a north-eastern state of India (Assam). Andersen health behaviour model was used to explore the factors influencing healthcare utilisation. The sample size for the survey and in-depth interviews were 300 and 19, respectively, recruited employing multistage random and purposive sampling techniques.

Out of 300 workers surveyed, 169 (56.3%) were females, 257 (85.7%) were married, 77 (25.7%) were illiterates and 229 (76.3%) had monthly household income less than 100 US$. The survey also found that 47.3% and 15.3% had non-communicable and communicable disease respectively. Most of the workers (67.3%) utilised government facilities, and close to one third (28.7%) utilised tea garden hospitals. About 63.3% had health insurance, but a majority (78.9%) did not use it previously. The analyses of interviews explored the need, enabling, predisposing factors under three important themes influencing utilisation of healthcare services among the workers.

Practical implications

The study generates evidence to strengthen the Indian Plantation Labour Act, 1951 for tea garden worker's welfare protection and warrants transition from colonial-era policies to contemporary industry realities in order to improve their living, employment, nutritional and health conditions.

Originality/value

The research adds to the existing literature on overall healthcare services utilisation (including coverage and utilisation of health insurance) among blue collar workers who usually lack access to healthcare facilities and explores important factors that determine utilisation in the Indian context.

- Healthcare services utilisation

- Anderson model

- Tea gardens workers

Rajput, S. , Hense, S. and Thankappan, K.R. (2022), "Healthcare utilisation: a mixed-method study among tea garden workers in Indian context", Journal of Health Research , Vol. 36 No. 6, pp. 1007-1017. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHR-02-2021-0101

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Sonalee Rajput, Sibasis Hense and K.R. Thankappan

Published in Journal of Health Research . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Access to healthcare is one of the essential components of healthcare services utilisation and for ensuring universal health coverage [ 1 ]. The global burden of disease (GBD) study has estimated the healthcare access and quality index (HAQ) for 195 countries [ 1 ]. As per this index, Iceland had the highest score (97.1 out of 100) and the Central African Republic had the lowest score 18.6 [ 1 ]. India scored 41 and ranked 145 among 195 countries. In India, Assam, a north-eastern state had the lowest score (34.0), indicating a higher level of disparity among the Indian states [ 1 ].

The state of Assam is popularly known for tea plantation, contributing about one-fifth to the state GDP [ 2 ]. Many casual and full-time workers across Indian states depend upon Assam's tea estates for their livelihood [ 3 ]. But, due to multiple reasons the health status of these workers is reported to be much lower than the state average [ 4 ]. These workers often lack access to basic amenities including schools, latrines, safe drinking water, healthcare and nutrition [ 4 ]. Due to poor access, they experience higher maternal mortality rate (404 per 100,000 live births), higher risk of pregnancy-related complications, hypertension (60%), poor nutritional status, low birth weight babies (43%) and higher prevalence of Tuberculosis (TB) (30–40%) compared to the general population in the state [ 4–6 ].

According to the Indian Plantation Labour Act, 1951, the tea garden authorities are mandated to provide the basic amenities of healthcare, education, drinking water, housing, child care facilities, maternal care and accident cover to all their workers in addition to minimum wage and maximum duty hour's provision [ 7 ]. However, there exist significant gaps across the state in implementation of this Act, primarily with respect to provision for basic amenities [ 3 ]. There are also evidences of mortalities attributed to tuberculosis, high blood pressure, lack of access to treatment and lower utilisation of healthcare services among the tea garden workers and their family members [ 4 ]. These evidences suggest discrepancies in healthcare access and utilisation by the tea garden workers in the state of Assam.

While a majority of research on the tea garden workers in India mainly focused on their health/nutritional status [ 4, 8 ] contraceptive practice [ 9 ], living, education, economic, employment status [ 10 ] and utilisation of sanitation facilities [ 11 ], studies specifically on health services utilisation are scant except for a few studies on maternal and neonatal health services utilisation and social determinants on health among the tea garden workers [ 12 ] in the region.

The Andersen health behaviour model [ 13 ] is designed to examine the determinants of health services utilisation and measures inequities in health service access amongst ethnic minorities and rural and remote populations. It identifies predisposing, enabling and need factors as determinants of healthcare service use. According to this model health services use can be predicted or explained by population characteristics, including individual's pre-dispositions to use services, resources that enable or impede use and their need for care. Predisposing factors reflect the individual's propensity to use health services which exist prior to the illness such as demographics, social structure and health beliefs, etc. Enabling factors are the resources that may facilitate access to services. It is a condition that may be changed by an individual and social efforts such as health insurance, free healthcare services, knowledge about own health status etc. and the need factors represent potential needs of health service use, such as self-perceived health, chronic conditions and restricted activity. Given this background, we examined the utilisation pattern of healthcare services and factors influencing utilisation by the tea garden workers in one of the backward districts of Assam.

2. Methodology

2.1 study design.

We used a sequential mixed-methods approach [ 14 ], wherein a quantitative phase (survey) was conducted in the beginning followed by the qualitative phase (in-depth interviews).This design was used because the quantitative data helped examine the utilisation pattern of healthcare services among the workers, assisted in identifying participants for follow-up interviews in the qualitative phase that explored the determining factors influencing utilisation in greater detail.

2.2 Study settings

This study was conducted in Golaghat district of Assam across three tea garden estates (TGEs): Radhabari, Bokakhat and Borjuri. The district was selected considering lower composite health index (below 50%) and a high priority district in the state of Assam and in the country [ 15 ]. Moreover, there are a large number of tea estates (74 in numbers) in this district and it has the highest maternal mortality rate (404 per 100,000 live births) [ 16 ].

2.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study was conducted among the tea garden workers, between the age group of 18-60 years, who in the past six months (i.e. between June and November 2019) had utilised any type of healthcare services. The participants for in-depth interviews were recruited from the survey participants who gave consent to be interviewed.

2.4 Sampling

Sampling was done for both quantitative (survey) and qualitative (in-depth interviews) phases of the study. The sample size for the survey was calculated using the formula, S = Z 2 P ∗ ( 1 − P ) / ME 2 , where “ Z ” is the critical ratio for 95% confidence interval (1.96), and “ P ” is the anticipated proportion of population utilisation rate for in-patient and out-patient services among general population of Assam i.e. 50%, “ME” is the margin of error which was taken as 6%. Applying a non-response rate of 10%, the sample size was calculated at 293.26, which was rounded off to 300. The participants of this study were recruited employing multistage random sampling.

A sub-division (Bokakhat sub-division) of the district was selected randomly using the lottery method from 3 sub-divisions in Golaghat district. The Bokakhat sub-division had 11 TGE of which three TGEs i.e. Bokakhat T.E, Radhabri T.E and Borjuri T.E. were randomly selected using a lottery method. Each of the above tea gardens had. 3,115, 618 and 254 workers (including seasonal workers) respectively. A total of 100 tea garden workers from each of the three TGE were recruited employing a random sampling technique from the list of tea garden workers obtained from the tea garden estate administration. If the selected worker did not utilise health services in the previous six months the next worker was selected from the list who utilised health services in the previous six months. In the qualitative phase, nineteen workers were recruited from the survey participants purposefully, who were local people, working in the surveyed TGEs since last one-year, utilised health services in the past six months and gave consent for the follow-up interviews in the qualitative phase.

2.5 Data collection tools and techniques

In the quantitative phase, an adapted questionnaire from LASI (Longitudinal Ageing Study in India) was used to collect data. Specifically, “heath insurance and services utilisation” section of the questionnaire was used in this study to meet the study objectives after ensuring the content and face validity. While the overall LASI tool is designed for individuals aged 45 years and above, this section of the tool was not dependent on any specific age groups; hence, it allowed the researchers to obtain data from the tea garden workers without any age restrictions [ 17 ]. In addition, the socio-demographic details of the tea garden workers their occupation and income details and health status were obtained. Socio-demographic details included age, sex, religion, marital status, education, living arrangement, type of family and number of family members. Occupation and income details of the workers included their monthly household income, nature of occupation and number of family members working in tea garden. Health status of the workers was assessed self-reported illnesses by asking if the respondent was suffering from any health ailments: communicable diseases, non-communicable diseases and disabilities. The pattern of healthcare service utilisation was measured in terms of the type of healthcare facilities used; healthcare providers visited, health services availed and health insurance usage in the last six months.

In the qualitative phase, in-depth interview method was employed using a semi-structured interview guide. This interview guide was developed using Andersen and Newman framework [ 13 ] of healthcare services utilisation considering the need, predisposing and enabling factors. A translated interview guide in vernacular (Assamese) language was used to conduct the interviews among a selected group of the tea garden workers selected purposefully. Each interview lasted for about 40-60 minutes, were audio recorded, translated in English, transcribed verbatim in Microsoft-Word version-11 (coded deductively for descriptive and Invivo codes).

2.6 Data analysis

The analysis of survey data was done using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics was used to analyse the survey data. The descriptive statistics consisted of univariate analysis such as calculation of frequencies and percentage for categorical variables. The data analysis for in-depth interviews of the tea garden workers was done thematically using N-Vivo version 12.

2.7 Ethical considerations

This study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Central University of Kerala, Kasaragod (India), Institutional Human Ethical Committee (CUK/IHEC/2019/054).

3.1 Quantitative results

The survey data were analysed for 300 tea garden workers. The socio-demographic characteristics of the workers are given in ( Table 1 ). Among the survey sample, more than half (56.3%) were females. About one-fourth (25.7%) were illiterate and a majority (76.3%) of them have a household income of less than INR 6,500 a month (i.e. less than 100 USD).

Self-reported illnesses and disability among the workers are given in Table 2 .

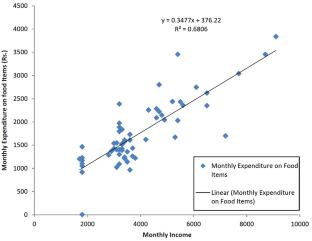

Most (67.30%) of the workers utilised government facilities while only 4% utilised private facilities such as nursing homes or private clinics, and close to one third (28.7%) of the workers utilised not-for-profit hospitals (i.e. tea garden hospitals). The preference of consulting allopathic physicians was high among the workers (77%). Interestingly, more than half of the workers (51%) also reported consulting folk/traditional healers ( Figure 1 ).

The survey data also revealed that 70.7% of the workers utilised outpatient services while 29.3% utilised in-patient services. Of the total outpatient services utilised 212 (70.7%), 23.6% was for laboratory services, 18.8% was for radiological investigations, 10.4% was for ANC and immunisation, and 47.2% was for other types of OPD services such as physician consultation ( Figure 2 ). Of the total inpatient services utilised by the workers 88 (29.3%), 14.7% had some surgical procedures, 22.3% had undergone laboratory investigations, 18% had radiological investigations, 4.5% had utilised emergency services and the remaining 40.5% were on medical management alone ( Figure 2 ).

More than half of the workers (63.3%) had health insurance and they were covered mainly under the Indian Government Health Insurance Scheme (99%) i.e. Ayushman Bharat and Atal Amrit Abhiyan, while 16% did not even know whether they were covered under any type of health insurance scheme. However, 150 (78.9%) of them did not utilise the scheme during their last visit to the healthcare facility ( Figure 3 ).

3.2 Qualitative results

The analysis of in-depth interviews explored the need, predisposing, enabling and other inhibiting factors influencing utilisation of healthcare services among the tea garden workers. The detailed outlay of the themes and sub-themes is given in Figure 4 .

3.2.1 Severity of illness and a quick-fix remedy

……. Whenever I fall sick, I first opt for home remedies. Only If I suffer severely, I prefer to consult a doctor (Participant-1)

When you're in pain, you have to look at different places to find out how you can get better. As a labourer I can’t wait for a long time for recovery. So, I want a speedy recovery that is the reason I went to Golaghat district hospital (Participant-5).

3.2.2 Accessibility and affordability of healthcare services

I visit tea garden hospital because it is nearby and their services are free. I think only tea garden hospital is more suitable to the word accessible and affordable but to what extent the services are available in our tea garden is questionable. If you are ill, definitely you will go to the nearest hospital. (Participant-4).

3.2.3 Barriers to accessing and utilising healthcare services

I don't have much money in my bank account so I cannot go elsewhere for treatment at our own cost. I would prefer only tea garden hospital for seeking treatment rather than going to other big hospital (participant no-1).

I am a woman, after 8 hours of hard work I need to take care of my children, and household work. It is very difficult to arrange time for my health (Participant-2).

First, I prefer to go to tea garden hospital but if I don't get relief I go to traditional healers and get the remedies and Yes, the superstitious power works for me. (Participant-5).

Our tea garden management authority gives referral services to the permanent workers only. The full-time regular worker gets bonus money, reimbursement money, referral service etc. But we are not getting all these facilities. (Participant-8).

The workers interviewed shared that regular full-time workers get referral services and not the seasonal workers. Therefore, it can be argued that the tea garden administration has neglected or failed to provide inclusive referral services to all workers; even though it is an important area it has not been addressed.

4. Discussions

Our study noted interesting utilisation patterns of healthcare services among the tea garden workers. In our study 47.3% and 15.3% of the tea garden workers reported to have non-communicable and communicable diseases respectively, who may require regular visits to a healthcare facility. Similar disease pattern (such as hypertension, stroke, anaemia, tuberculosis, respiratory infections) are well documented from this region [ 8 ]. We also noted that a majority of the workers (76.3%) had less than INR 6500 (less than USD 100) of household income a month which seems to have not changed significantly in the last decade.

A sizeable proportion (32.3%) of the workers was employed casually who are generally denied of healthcare services by the TGEs administration through their tea garden hospitals. Most of the workers surveyed had utilised government hospitals (67.3%) previously and the remaining, either utilised a private not-for-profit tea garden hospital (28.7%) or a private for-profit facility like nursing homes/clinics (4%). These findings are in concurrence with earlier literature that suggested blue collar and casual workers tend to use public services while the wealthier tend to consult private health services [ 18 ]. This also indicates greater utilisation of government healthcare facilities compared to private facilities by the workers, primarily due to the higher cost of medical treatment in the private sector and poor household income of the workers.

The idea of affordability and accessibility also emerged in the interviews as these elements were found to be influencing the health services utilisation of the workers. Specifically, we observed that healthcare services which are affordable and accessible are more likely to be utilised by the workers. In contrast, it is also interesting to note an increasing trend in the utilisation of private health facilities across Indian states [ 19 ] due to low investment in the public health sector and a growing middle-class population increasingly demanding better quality of healthcare services [ 19 ]. However, the economically weaker section (such as the tea garden workers) still depends on government healthcare services in the country [ 18 ]. Therefore, this study calls attention to policy makers towards greater investment in the public health sector to make healthcare more affordable and accessible, especially for the weaker economic section of the society including the tea garden workers whose earning has been dismally low.

According to the Plantations Labour Act, 1951 [ 7 ], the tea garden employers are mandated to provide medical facilities, clean drinking water, latrines and urinals to all cadres of workers in plantation areas. Tea garden workers are highly dependent on their employers, as there is limited access to education and economic opportunities outside tea plantations areas in the region. Our interviews identify leniency in implementation of the Act in the tea garden areas surveyed. Our interview participants (especially the causal/part-time workers) reveal that they lack access to basic medical facilities, referral facilities and are living with compromised amenities and poor working conditions. Similar issues are also reported in previous literature including poor living and working conditions [ 12 ] non-availability of doctors and medicines in tea garden hospitals [ 12 ] as well as sanitation and housing facilities [ 11 ].

In another interesting finding we noted that despite the Indian Government's effort to popularise Ayurveda Yoga Unani Siddha Homeopathy (AYUSH) system of medicine, tea garden workers are still inclined towards the modern system of medicine. This was similar to the national level data (by the National Sample Survey Office- NSSO) that found a higher tendency (90%) towards utilisation of allopathy treatment in India. In both rural and urban settings, only 5–7% use AYUSH systems of medicine [ 20 ]. Similar observations were recorded in our study where a majority of the workers were found to seek treatment from allopathic doctors (77%) vis 'a vis AYUSH doctors (0.70%). This indicates the preference of tea garden workers towards allopathic treatment. One of the possible reasons why a majority of the tea garden workers visited allopathy physicians emerged in our qualitative findings where the workers prefer to get quick-fix remedy for their health problem to resume work/earning. Additionally, nearly 51% of the workers had visited quacks/folk/traditional healers for treatment. Illiteracy, poor income and less treatment cost are the few factors responsible for seeking treatment from quacks/folk healers emerged in the interviews with the workers.

Our study also found that 63.3% of the workers had health insurance, of which a majority (78.9%) did not use previously. Surprising, 16% did not even know whether they were covered under any type of health insurance schemes such as Ayushman Bharat Abhiyan (Govt. of India) or Atal Amrit Abhiyan, Govt. of Assam, which they are entitled for due to their economic status. These findings contradicted existing literature that demonstrated possession of health insurance scheme was positively associated with higher utilisation of health facilities, particularly among below poverty level populations [ 21 ]. Lack of education and awareness among the tea garden workers could be the possible reasons for ignorance about different government health funding schemes in the region [ 10 ]. Therefore, more action-based research must be undertaken to raise awareness about various government health insurance policies and their utilisation. For this purpose, proper arrangements of sensitisation camps by the tea garden estate administration in collaboration with the district health administration needs to be conducted so that the workers are aware of the available health schemes offered by both the state and central governments.

In addition to the patterns of healthcare services utilisation, our study also observed a multitude of barriers inhibiting healthcare services utilisation among the tea garden workers in the region. The barriers cited by participants included lack of referral services, unavailability of doctors and medicines in tea garden hospitals, difficulties in patient-physician communication and poor support from the employers. These barriers did exist in the literature for decades [ 1–3 ] and have been unchanging all the while. Therefore, we argue that studies may be conducted among healthcare providers, tea garden authorities and tea garden hospitals to better understand their perspectives towards providing welfare assistance including healthcare access to overcome the healthcare utilisation barriers.

5. Conclusion

This study identifies the pattern of illness and health services utilisation including awareness and usage for health insurance among the tea garden workers in Assam. It also explored the associated facilitating factors as well as barriers responsible for utilisation of healthcare services. The study also generates evidence to strengthen the Indian Plantation Labour Act, 1951 with respect to daily living and working conditions, uniformity of minimum wages and provision for better healthcare facilities. These can be attained through well-resourced tea garden hospitals, convergence of health and other welfare programmes and intersectoral coordination among state, central, health authorities and tea boards. Our findings also warrant policy makers for a transition from colonial-era policies and shift towards contemporary industry realities for improving the living, working and health conditions of the tea garden workers in the Indian context.

6. Limitations

Like all surveys, our study relied on self-reported data, so recall bias may limit the reliability of findings. The views of key informants in respect to health services utilisation were not captured in this study due to time and permission constraint. Lastly, the data collected were drawn only from three tea gardens of Golaghat district. Hence, the results may have limited generalisability. Future research needs to improve upon these limitations.

Conflict of Interest: None

Utilisation of health services among the tea garden workers

Utilisation of out-patient and in-patient services among the tea garden workers

Utilisation of health insurance

Factors influencing the utilisation of healthcare services among the tea garden workers

Socio-demographic, income and occupation details of the tea garden workers ( n = 300)

Self-reported illnesses and disability among the tea garden workers

1 Fullman N , Yearwood J , Abay SM , Abbafati C , Abd-Allah F , Abdela J , et al. Measuring performance on the healthcare access and quality index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2016 . Lancet . 2018 ; 391 ( 10136 ): 2236 - 71 . doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30994-2 .

2 Kausar A , Giri S , Roy P , Giri A . Changes in buccal micronucleus cytome parameters associated with smokeless tobacco and pesticide exposure among female tea garden workers of Assam, India . Int J Hyg Environ Health . 2014 ; 217 ( 2–3 ): 169 - 75 . doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2013.04.007 .

3 Baishya D . History of tea industry and status of tea garden workers of Assam . Int J Appl Res . 2016 ; 2 ( 9 ): 552 - 6 .

4 Sahoo D , Konwar K , Sahoo BK . Health condition and health awareness among the tea garden laborers: a case study of a tea garden in Tinsukia district of Assam . IUP J Agri Econ . 2010 ; 7 ( 4 ): 50 - 72 .

5 Borah PK , Kalita HC , Paine SK , Khaund P , Bhattacharjee C , Hazarika D , et al. An information, education and communication module to reduce dietary salt intake and blood pressure among tea garden workers of Assam . Indian Heart J . 2018 ; 70 ( 2 ): 252 - 8 . doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2017.08.008 .

6 Phukan RK , Mahanta J . A study of neonatal deaths in the tea gardens of Dibrugarh district of upper Assam . J Indian Med Assoc . 1998 ; 96 ( 11 ): 333 - 4 .

7 Tea Board India . Plantations labour Act, 1951 . [cited 2019 Aug 13]. Available at: http://www.teaboard.gov.in/pdf/policy/plantations%20labour%20act_amended.pdf .

8 Medhi GK , Hazarika NC , Shah B , Mahanta J . Study of health problems and nutritional status of tea garden population of Assam . Indian J Med Sci . 2006 ; 60 ( 12 ): 496 - 505 . doi: 10.4103/0019-5359.28979 .

9 Saha SK , Bag T , De Aloke K , Basak S , Chhetri A , Banerjee J . Contraceptive practice of the tribal women in tea garden area of North Bengal . J Indian Med Assoc . 2007 ; 105 ( 8 ): 440 - 448 .

10 Bosumatari D , Goyari P . Educational status of tea plantation women workers in Assam: an empirical analysis . Asian J Multidisci Stu . 2013 ; 1 ( 3 ): 17 - 26 .

11 Bora PJ , Das BR , Das N . Availability and utilization of sanitation facilities amongst the tea garden population of Jorhat district, Assam . Int J Community Med Pub Health . 2018 ; 5 ( 6 ): 2506 - 11 . doi: 10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20182186 .

12 Bhattacherjee S , Datta S , Saha JB , Chakraborty M . Maternal health care services utilization in tea gardens of Darjeeling, India . Journal of Basic and Clinical Reproductive Sciences . 2013 ; 2 ( 2 ): 77 - 84 .

13 Aday LA , Andersen R . A framework for the study of access to medical care . Health Serv Res . 1974 ; 9 ( 3 ): 208 - 20 .

14 Creswell JW , Plano Clark VL , Gutmann ML , Hanson WE . Advanced mixed methods research designs . In: Tashakkori , A , Teddlie , C , (Eds). Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research . Thousand Oaks, California, CA : Sage ; 2003 : 209 - 40 .

15 India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare [MoHFW] , National Rural Health Mission [NRHM]. Guidance note for implementation of RMNCH+A interventions in high priority districts . New Delhi : NRHM ; 2013 .

16 India, Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Vital Statistics Division . Annual health survey 2012–13 fact sheet: Assam . New Delhi : Vital Statistics Division ; 2014 .

17 International Institute of Population Sciences [IIPS] . Longitudinal ageing study in India (LASI) . [cited 2019 Aug 13]. Available at: http://14.143.90.243/iips/content/lasi-goals .

18 Levesque JF , Haddad S , Narayana D , Fournier P . Outpatient care utilization in urban Kerala, India . Health Policy Plan . 2006 ; 21 ( 4 ): 289 - 301 . doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl013 .

19 Singh PK , Rai RK , Alagarajan M , Singh L . Determinants of maternity care services utilization among married adolescents in rural India . PloS One . 2012 ; 7 ( 2 ): e31666 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031666 .

20 Rudra S , Kalra A , Kumar A , Joe W . Utilization of alternative systems of medicine as health care services in India: evidence on AYUSH care from NSS 2014 . PloS One . 2017 ; 12 ( 5 ): e0176916 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176916 .

21 Sreeramareddy CT , Sathyanarayana TN , Kumar HN . Utilization of health care services for childhood morbidity and associated factors in India: a national cross-sectional household survey . PloS One . 2012 ; 7 ( 12 ): e51904 . doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051904 .

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the study participants involved in this study. The author(s) would also like to acknowledge the important contribution of Dr Vellikkeel Raghavan in proofreading the manuscript.

Funding : No funding received to undertake this study.

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Advertisement

Gender, Women and Work in the Tea Plantation: A Case Study of Darjeeling Hills

- Published: 14 November 2018

- Volume 61 , pages 537–553, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Mamta Gurung 1 &

- Sanchari Roy Mukherjee 1

511 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

Women workers and their role in the tea plantations have received relatively scant attention in plantation literature and women’s studies although they dominate the tea industry. Women workers are an asset and backbone of the tea industry, and despite their contributions women workers have always been relegated to the bottom strata and considered the most abundant and cheapest labour force rather than as a source of specialised labour. Workers still earn meagre incomes, suffer from low levels of health care and personal well-being, lives entrapped in poverty and are cut off from the mainstream. The entire spectrum of elements, which acts as a barrier to the equitable participation of women in development, ranges from education, training, health, cultural and social considerations. This paper deals with the participation of women in the workforce and the impact on their socio-economic life. It also examines the ways in which women workers are marginalised on multiple fronts: casualisation of the workforce, upward occupational mobility and political space of trade unions.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Flexible Working, Work–Life Balance, and Gender Equality: Introduction

Heejung Chung & Tanja van der Lippe

Gender Inequality and Workplace Organizations: Understanding Reproduction and Change

Social Norms as a Barrier to Women’s Employment in Developing Countries

Seema Jayachandran

Baland, J.M., J. Dreze, and L. Leruth. 1999. Daily Wages and Piece rates in Agrarian Economies. Journal of Development Economics 59(1999): 445–461.

Article Google Scholar

Bhowmik, S.K. 1982. Wages of Tea Garden Workers in West Bengal. Economic and Political Weekly 17(40): 1600–1601.

Google Scholar

Bhowmik, S.K. 2011. Ethnicity and Isolation: Marginalisation of Tea Plantation Workers. Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 4(2): 235–253.

Das Gupta, R. 1986. From Peasants and Tribesmen to Plantation Workers: Colonial Capitalism, Reproduction of Labour Power and Proletarianisation in North East India, 1850s to 1947. Economic and Political Weekly 21(4): PE2-PE.

Delle, J. A. 2008. Womens Lives and Labour on Radnor, a Jamaican Coffee Plantation, 1822-1826, Caribbean Quarterly, 54(4), The 60th Anniversary Edition: West Indian History, 7-23.

Gannage, C. 1986. Women and Work: Inequality in the Labour Market by Paul Philips. Erin Philips, Labour/ Le Travail 17: 295–298.

Jamwal, R., and D. Gupta. 2010. Work Participation of Females and Emerging Labour Laws in India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Social Sciences, II 1: 161–172.

Joseph, K.J., and P.S. George. 2010. Structural Infirmities in India’s Plantation Sector-Natural Rubber and Spices. National Research Programme on Plantation Development. Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram.

Joshi, H . 1976. Prospects and Case for Employment of Women in Indian Cities, Economic and Political Weekly,11(31/33), 1303+1305+1307-1308.

Kelkar, G. 2005. Development Effectiveness through Gender Mainstreaming: Gender Equality and Poverty Reduction in South Asia. Economic and Political Weekly 40(44/45): 4690–4699.

Kandasamy, M.V. 2002. Womens Leadership in Plantation Trade Unions in Sri Lanka . ISD Publications, Sri Lanka: The Struggle Continues...

Kar, R.K. 1984. Labour Pattern and Absenteeism: A Case Study in Tea Plantation in Assam, India , Anthropos, Bd.79, H. 1/3, 13-24.

Kaur, A. 2000. Changing Labour Relations in Malaysia 1970s–1990s. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Rural Asiatic Society 73(1): 1–16.

Koshy, T., and M. Tiwary. 2011. Enhancing the Opportunities for Women in India's Tea Sector: A Gender Assessment of Certified Tea Gardens . Bangalore: Prakruthi.

Labour Bureau. 2010. Statistical Profile On Women Labour (2008–09) . Chandigarh/Shimla: Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India.

Labour Bureau. 2014. Statistical Profile On Women Labour (2012–13) . Chandigarh/Shimla: Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India.

Labour Bureau. 2016. Report on the Working of The Minimum Wages Act, 1948 For The Year 2014 . Government of India: Chandigarh.

Labour in West Bengal: Annual Report 2011, Government of West Bengal.

Mishra, D.K., V. Upadhyay, and A. Sarma. 2008. Crisis in the Tea Sector: A Study of Assam Tea Gardens. The Indian Economic Journal: The quarterly journal of the Indian Economic Association 56(3): 39–56.

Mukherjee, S.R. 2007. Labour, Work Participation & Empowerment: Women in the Plantation Sector Of North Bengal in S.R. Mukherjee, eds., Indian Women, Broken Words, Distant Dreams, Levant Books.

Tea Board of India. 2015. Government of India.

Tea Statistics. 2003. Tea Board of India.

Sankrityayana, J. 2006. Productivity And Decent Work In The Tea Industry In India—A Consultative Meeting . New Delhi: International Labour Office.

Savur, M. 1973. Labour and Productivity in the Tea Industry. Economic and Political Weekly 8(11): 551–559.

Sarkar, K., and S.K. Bhowmik. 1998. Trade Unions and Women Workers in Tea Plantations. Economic and Political Weekly 17(52): L50–L52.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Mamta Gurung acknowledges Maulana Azad National Fellowship Granted by UGC, New Delhi, Award Lett. No.F1-17.1/2013-14/MANF-2013-14-BUD-WES-21331/(SA-III/Website).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, North Bengal University, Siliguri, West Bengal, India

Mamta Gurung & Sanchari Roy Mukherjee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mamta Gurung .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Gurung, M., Mukherjee, S.R. Gender, Women and Work in the Tea Plantation: A Case Study of Darjeeling Hills. Ind. J. Labour Econ. 61 , 537–553 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-018-0142-3

Download citation

Published : 14 November 2018

Issue Date : September 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-018-0142-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cheap labour

- Feminisation

- Gender characteristics

- Meagre wages

- Social amenities

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Share full article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio , a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

How Tesla Planted the Seeds for Its Own Potential Downfall

Elon musk’s factory in china saved his company and made him ultrarich. now, it may backfire..

This transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors. Please review the episode audio before quoting from this transcript and email [email protected] with any questions.

From “The New York Times,” I’m Katrin Bennhold. This is “The Daily.”

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Today, the story of how China gave Tesla a lifeline that saved the company — and how that lifeline has now given China the tools to beat Tesla at its own game. My colleague, Mara Hvistendahl, explains.

It’s Tuesday, April 9.

So, Mara, you’ve spent the past four months investigating Elon Musk and his ties to China through his company, Tesla. Tell us why.

Well, a lot of American companies are heavily invested in China, but Tesla’s kind of special. As my colleagues and I started talking to sources, we realized that many people felt that China played a crucial role in rescuing the company at a critical moment when it was on the brink of failure and that China helps account for Tesla’s success, for making it the most valuable car company in the world today, and for making Elon Musk ultra rich.

That’s super intriguing. So maybe take us back to the beginning. When does the story start?

So the story starts in the mid 2010s. Tesla had been this company that had all this hype around it. But —

A lot of people were shocked by Tesla’s earnings report. Not only did they make a lot less money than expected, they’re also making a lot less cars.

Tesla was struggling.

The delivery of the Model 3 has been delayed yet again.

Tesla engineers are saying 40 percent of the parts made at the Fremont factory need reworking.

At the time, they made their cars in Fremont, California, and they were facing production delays.

Tesla is confirming that Cal/OSHA is investigating the company over concerns over workplace safety.

Elon Musk has instituted a kind of famously grueling work culture at the factory, and that did not go over well with California labor law.

The federal government now has four active investigations involving Tesla.

They were clashing with regulators.

The National Transportation Safety Board will investigate a second crash involving Tesla’s autopilot system.

Billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk — friends are really concerned about him. That’s what Musk told “The New York Times.”

And by 2018, he was having all of these crises.

According to “The Times,” Musk choked up multiple times and struggled to maintain his composure during an hour-long interview about turmoil at his electric car company, Tesla.

So all of this kind of converged to put immense pressure on him to do something.

And where does China come in?

Well, setting up a factory in China, in a way, would solve some of these problems for Musk. Labor costs were lower. Workers couldn’t unionize there. China provided access to this steady supply of cheaper parts. So Elon Musk was set on going to China. But first, Tesla and Musk wanted to change a key policy in China.

Hmm, what kind of policy?

So they wanted China to adopt a policy that was aimed at lowering car emissions. And the idea was that it would be modeled after a similar policy in California that had benefited Tesla there.

OK, so explain what that policy actually did. And how did it benefit Tesla?

So California had this system called the Zero-Emission Vehicle program. And that was designed to encourage companies to make cleaner cars, including electric vehicles. And they did that by setting pollution targets. So companies that made a lot of clean cars got credits. And then companies that failed to meet those targets, that produced too many gas-guzzling cars, would have to buy credits from the cleaner companies.

So California is trying to incentivize companies to make cleaner cars by forcing the traditional carmakers to pay cleaner car makers, which basically means dirtier car makers are effectively subsidizing cleaner cars.

Yes, that’s right. And Tesla, as a company that came along just making EVs, profited immensely from this system. And in its early years, when Tesla was really struggling to stay afloat, the money that it earned from selling credits in California to polluting car companies were absolutely crucial, so much so that the company structured a lot of its lobbying efforts around this system, around preserving these credits. And we talked to a former regulator who said as much.

How much money are we talking about here?

So from 2008, when Tesla unveiled its first car, up until the end of last year, Tesla made almost $4 billion by selling credits in California.

Wow. So Musk basically wants China to recreate this California-style program, which was incredibly lucrative for Tesla, there. And they’re basically holding that up as a condition to their building a factory in China.

Right. And at this point in the story, an interesting alliance emerges. Because it wasn’t just Tesla that wanted this emissions program in China. It was also environmentalists from California who had seen the success of the program up close in their own state.

If you go back to that period, to the early 2010s, I was living in China at the time in Beijing and Shanghai. And it was incredibly polluted. We called it airpocalypse at times. I had my first child in China at that point. And as soon as it was safe to put a baby mask on her, we put a little baby mask on her. There were days where people just would try to avoid going outside because it was so polluted. And some of the pollution was actually wafting across the Pacific Ocean to California.

Wow, so California is experiencing that Chinese air pollution firsthand and, in a way, has a direct stake in lowering it.

That’s right. So Governor Jerry Brown, for example — this became kind of his signature issue, was working with China to clean up the environment, in part by exporting this emission scheme. It was also an era of a lot more US-China cooperation. China was seen as absolutely crucial to combating climate change.

So you had all these groups working to get this California emissions scheme exported to China — and the governor’s office and environmental groups and Tesla. And it worked. In 2017, China did adopt a system that was modeled after California’s.

It’s pretty incredible. So California basically exports its emissions-trading system to China, which I imagine at the time was a big win for Californian environmentalists. But it was also a big win for Tesla.

It was definitely a big win for Tesla. And we know that in just a few years Tesla, made almost $1 billion from the emissions-trading program he helped lobby for in China.

So Elon Musk goes on, builds a factory in China. And he does so in Shanghai, where he builds a close relationship with the top official in the city, who actually is now the number-two official in all of China, Li Qiang.

So according to Chinese state media, Elon Musk actually proposed building the factory in two years, which would be fast. And Li came back and proposed that they do it in one year, which — things go up really quickly in China. But even for China, this is incredibly fast. And they broke ground on the factory in January 2019. And by the end of the year, cars were rolling off the line. So then in January 2020, Musk was able to get up on stage in Shanghai and unveil the first Chinese-made Teslas.

Really want to thank the Tesla team and the government officials that have been really helpful in making this happen.

Next to him on stage is Tesla’s top lobbyist who helped push through some of these changes.

Thank you. Yeah, everybody can tell Elon’s super, super happy today.

[SPEAKING CHINESE]

And she says —

Music, please.

Cue the music. [UPBEAT MUSIC]

And he actually broke into dance. He was so happy, a kind of awkward dance.

[UPBEAT MUSIC]

And what is the factory like?

The Shanghai factory is huge. 20,000 people work there. Tesla’s factories around the world tend to be pretty large, but the Shanghai workers work more shifts. And when Tesla set up in China, Chinese banks ended up offering Tesla $1.5 billion in low-interest loans. They got a preferential tax rate in Shanghai.

This deal was so generous that one auto industry official we talked to said that a government minister had actually lamented that they were giving Tesla too much. And it is an incredibly productive factory. It’s now the flagship export factory for Tesla.

So it opens in late 2019. And that’s, of course, the time when the pandemic hits.

Yes. I mean, you might think that this is really poor timing for Elon Musk. But it didn’t quite turn out that way. In fact, Tesla’s factory in Shanghai was closed for only around two weeks, whereas the factory in Fremont was closed for around two months.

That’s a big difference.

Yes, and it really, really mattered to Elon Musk. If you can think back to 2020, you might recall that he was railing against California politicians for closing his factory. In China, the factory stayed open. Workers were working around the clock. And Elon Musk said on a podcast —

China rocks, in my opinion.

— China rocks.

There’s a lot of smart, hardworking people. And they’re not entitled. They’re not complacent, whereas I see —

We’ve seen a lot of momentum and enthusiasm for electric vehicles, stocks, and Tesla certainly leading the charge.

Tesla’s stock price kept going up.

Tesla has become just the fifth company to reach a trillion-dollar valuation. The massive valuation happened after Tesla’s stock price hit an all-time high of more than $1,000.

So this company that had just a few years earlier been on the brink of failure, looking to China for a lifeline, was suddenly riding high. And —

Tesla is now the most valuable car company in the world. It’s worth more than General Motors, Ford, Fiat, Chrysler.

By the summer, it had become the most valuable car company in the world.

Guess what? Elon Musk is now the world’s richest man.

“Forbes” says he’s worth more than $255 billion.

And Elon Musk’s wealth is tied up in Tesla stock. And in the following year, he became the wealthiest man in the world.

So you have this emission trading system, which we discussed and which, in part, thanks to Tesla, is now established in China. It’s bringing in money to Tesla. And now this Shanghai factory is continuing to produce cars for Tesla in the middle of the pandemic. So China really paid off for Tesla. But what was in it for China?

Well, China wasn’t doing this for charity.

What Chinese leaders really wanted was to turn their fledgling electric vehicle industry into a global powerhouse. And they figured that Tesla was the ticket to get there. And that’s precisely what happened.

We’ll be right back.

So, Mara, you’ve just told us the story of how Elon Musk used China to turn Tesla into the biggest car maker in the world and himself — at one point — into the richest man in the world. Now I want to understand the other side of this story. How did China use Tesla?

Well, Tesla basically became a catfish for China’s EV industry.

A catfish, what do you mean by that?

It’s a term from the business world. And, essentially, it means a super aggressive fish that makes the other fish in the pond swim faster. And by bringing in this super competitive, aggressive foreign company into China, which at that point had these fledgling EV companies, Chinese leaders hoped to spur the upstart Chinese EV makers to up their game.

So you’re saying that at this point, China actually already had a number of smaller EV companies, which many people in the West may not even be aware of, these smaller fish in the pond that you were referring to.

Yes, there were a lot of them. They were often locally based. Like, one would be strong in one city, and one would be strong in another city. And Chinese leaders saw that they needed to become more competitive in order to thrive.

And China had tried for decades to build up this traditional car industry by bringing in foreign companies to set up joint ventures. They had really had their sights set on building a strong car industry, and it didn’t really work. I mean, how many traditional Chinese car company brands can you name?

Exactly none.

Yeah, right. So going back to the aughts and the 2010s, they had this advantage that many Chinese hadn’t yet been hooked on gas-guzzling cars. There were still many people who were buying their first car ever. So officials had all these levers they could pull to try to encourage or try to push people’s behavior in a certain direction.

And their idea was to try to ensure that when people went to buy their first car, it would be an EV — and not just an EV but, hopefully, a Chinese EV. So they did things like — at the time, just a license plate for your car could cost an exorbitant amount of money and be difficult to get. And so they made license plates for electric vehicles free. So there were all these preferential policies that were unveiled to nudge people toward buying EVs.

So that’s fascinating. So China is incentivizing consumers to buy EV cars and incentivizing also the whole industry to get its act together by chucking this big American company in the mix and hoping that it will increase competitiveness. What I’m particularly struck by, Mara, in what you said is the concept of leapfrogging over the conventional combustion engine phase, which took us decades to live through. We’re still living in it, in many ways, in the West.

But listening to you, it sounds a little bit like China wasn’t really thinking about this transition to EVs as an environmental policy. It sounds like they were doing this more from an industrial-policy perspective.

Right. The environment and the horrible era at the time was a factor, but it was a pretty minor factor, according to people who were privy to the policy discussions. The more significant factor was industrial policy and an interest in building up a competitive sphere.

So China now wants to become a leader in the global EV sector, and it wants to use Tesla to get there. What does that actually look like?

Well, you need sophisticated suppliers to make the component parts of electric vehicles. And just by being in China, Tesla helped spur the development of several suppliers. Like, for example, the battery is a crucial piece of any EV.

And Tesla, with a fair amount of encouragement — and also various levers from the Chinese government — became a customer of a battery maker called CATL, a homegrown Chinese battery maker. And they have become very close to Tesla and have even set up a factory near Teslas in Shanghai. And today, with Tesla’s business — and, of course, with the business of some other companies — CATL is the biggest battery maker in the world.

But beyond just stimulating the growth of suppliers, Tesla also made these other fish in the pond swim faster. And the biggest Chinese EV company to come out of that period is one called BYD. It’s short for Build Your Dreams.

We are BYD. You’ve probably never heard of us.

From battery maker to the biggest electric vehicle or EV manufacturer in China.

They’ve got a lot of models. They’ve got a lot of discounts. They’ve got a lot of market growth.

China’s biggest EV maker just overtook Tesla in terms of worldwide sales.

BYD 10, Chinese automobile redefined.

I’ve actually started seeing that brand on the streets here in Europe recently, especially in Germany, where my brother actually used to lease a Tesla and now leases a BYD.

Does he like it?

He does. Although he did, to be fair, say that he misses the luxury of the Tesla, but it just became too expensive, really.

The price point is a huge reason that BYD is increasingly giving Tesla a run for its money. Years ago, back in 2011 —

Although there’s competitors now ramping up. And, as you’re familiar with, BYD, which is also —

— Elon Musk actually mocked their cars.

— electric vehicles, here he is trying to compete. Why do you laugh?

He asked an interviewer —

Have you seen their car?

I have seen their car, yes.

— have you seen their cars? Sort of suggesting, like, they’re no competition for us.

You don’t see them at all as a competitor?

Why is that? I mean, they offer a lower price point.

I don’t think they have a great product. I think their focus is — and rightly should be — on making sure they don’t die in China.

But they have been steadily improving. They’ve been in the EV space for a while, but they really started improving a few years ago, once Tesla came on the scene. That was due to a number of factors, not entirely because of Tesla. But Tesla played a role in helping train up talent in China. One former Tesla employee who worked at the company as they were getting set up in China told me that most of the employees who were at the company at the time now work for Chinese competitors.

So they have really played this important role in the EV ecosystem.

And you mentioned the price advantage. So just for comparison, what does an average BYD sell for compared to a more affordable Tesla car?

So BYD has an ultra-cheap model called the Seagull that sells for around $10,000 now in China, whereas Tesla Model 3s and Model Ys in China sell for more than twice that.

Wow. How’s BYD able to sell EVs at these much lower prices?

Well, the Seagull is really just a simpler car. It has less range than a Tesla. It lacks some safety measures. But BYD has this other crucial advantage, which is that they’re vertically integrated. Like, they control many aspects of the supply chain, up and down the supply chain. When you look at the battery level, they make batteries. But they even own the mines where lithium is mined for the batteries.

And they recently launched a fleet of ships. So they actually operate the boats that are sending their cars to Europe or other parts of the world.

So BYD is basically cutting out the middleman on all these aspects of the supply chain, and that’s how they can undercut other car makers on price.

Yeah. They’ve cut out the middleman, and they’ve cut out the shipping company and almost everything else.

So how is BYD doing now as a company compared to Tesla?

In terms of market cap, they’re still much smaller than Tesla. But, crucially, they overtook Tesla in sales in the last quarter of last year.

Yeah, that was a huge milestone. Tesla still dominates in the European market, which is a very important market for EVs. But BYD is starting to export there. And Europe traditionally is kind of automotive powerhouse, and the companies and government officials there are very, very concerned. I interviewed the French finance minister, and he told me that China has a five - to seven-year head start on Europe when it comes to EVs.

Wow. And what has Elon Musk said about this incredible rise of BYD in recent years? Do you think he anticipated that Tesla’s entry into the Chinese market could end up building up its own competition?

Well, I can’t get inside his head, and he did not respond to our questions. But —

The Chinese car companies are the most competitive car companies in the world.

— he has certainly changed his tune. So, remember, he was joking about BYD some years ago.

Yeah, he’s not joking anymore.

I think they will have significant success.

He had dismissed Chinese EV makers. He now appears increasingly concerned about these new competitors —

Frankly, I think if there are not trade barriers established, they will pretty much demolish most other car companies in the world.

— to the point that on an earnings call in January, he all but endorsed the use of trade barriers against them.

They’re extremely good.

I think it’s so interesting, in a way — of course, with perfect hindsight — the kind of maybe complacency or naivete with which he may not have anticipated this turn of events. And in some ways, he’s not alone, right? It speaks to something larger. Like, China, for a long time, was seen as kind of the sweatshop or the manufacturer of the world — or perhaps as an export market for a lot of these Western companies. It certainly wasn’t putting out its own big brand names. It was making stuff for the brand names.

But recently, they have quite a lot of their own brand names. Everybody talks about TikTok. There’s Huawei. There’s WeChat, Lenovo. And now there is BYD. So China is becoming a leader in technology in certain areas. And I think that shift in some ways has happened. And a lot of Western companies — perhaps like Tesla — were kind of late to waking up to that.

Right. Tesla is looking fragile now. Their stock price dropped 30 percent in the first quarter of this year. And to a large degree, that is because of the threat of companies like BYD from China and the perception that Tesla’s position as number one in the market is no longer guaranteed.

So, Mara, all this raises a much bigger question for me, which is, who is going to own the future of EVs? And based on everything you’ve said so far, it seems like China owns the future of EVs. Is that right?

Well, possibly, but the jury is still out. Tesla is still far bigger for now. But there is this increasing fear that China owns the future of EVs. If you look at the US, there are already 25 percent tariffs on EVs from China. There’s talk of increasing them. The Commerce Department recently launched an investigation into data collection by electric vehicles from China.

So all of these factors are creating uncertainty around what could happen. And the European Union may also add new tariffs against Chinese-made cars. And China is an economic rival and a security rival and, in many ways, our main adversary. So this whole issue is intertwined with national security. And Tesla is really in the middle of it.

Right. So the sort of new Cold War that people are talking about between the US and China is, in a sense, the backdrop to this story. But on one level, what we’ve been talking about, it’s really a corporate story, an economic story that has this geopolitical backdrop. But it’s also very much an environmental story. So, regardless of how Elon Musk and Tesla fare in the end, is BYD’s rise and its ability to create high-quality and — perhaps more importantly — affordable EVs ultimately a good thing for the world?

If I think back on those years I spent living in Shanghai and Beijing when it was extremely polluted and there were days when you couldn’t go outside — I don’t think anyone wants to go back to that.

So it’s clear that EVs are the future and that they’re crucial to the green energy transition that we have to make. How exactly we get there is still unclear. But what is true is that China did just make that transition easier.

Mara, thank you so much.

Thank you, Katrin.

Here’s what else you need to know today.

[CROWD CHEERING]

Millions of people across North America were waiting for their turn to experience a rare event on Monday. From Mexico —

Cuatro, tres, dos, uno.

— to Texas.

Awesome, just awesome.

We can see the corona really well. Oh, you can see —

[BACKGROUND CHATTER]

Oh, and we are falling into darkness right now. What an incredible sensation. And you are hearing and seeing the crowd of 15,000 gathered here in south Illinois.

Including “Daily” producers in New York.

It’s like the sky is almost —

— like a deep blue under the clouds.

Wait, look. It’s just —

Oh my god. The sun is disappearing. And it’s gone. Oh. Whoa.

All the way up to Canada.

Yeah, that’s what I’m talking about. That’s what I’m talking about.

The moon glided in front of the sun and obscured it entirely in a total solar eclipse, momentarily plunging the day into darkness.

It’s super exciting. It’s so amazing to see science in action like this.

Today’s episode was produced by Rikki Novetsky and Mooj Zadie with help from Rachelle Bonja. It was edited by Lisa Chow with help from Alexandra Leigh Young, fact checked by Susan Lee, contains original music by Marion Lozano, Diane Wong, Elisheba Ittoop, and Sophia Lanman and was engineered by Chris Wood.

Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly.

That’s it for “The Daily.” I’m catching Katrin Bennhold. See you tomorrow.

- April 11, 2024 • 28:39 The Staggering Success of Trump’s Trial Delay Tactics

- April 10, 2024 • 22:49 Trump’s Abortion Dilemma

- April 9, 2024 • 30:48 How Tesla Planted the Seeds for Its Own Potential Downfall

- April 8, 2024 • 30:28 The Eclipse Chaser

- April 7, 2024 The Sunday Read: ‘What Deathbed Visions Teach Us About Living’

- April 5, 2024 • 29:11 An Engineering Experiment to Cool the Earth

- April 4, 2024 • 32:37 Israel’s Deadly Airstrike on the World Central Kitchen

- April 3, 2024 • 27:42 The Accidental Tax Cutter in Chief

- April 2, 2024 • 29:32 Kids Are Missing School at an Alarming Rate

- April 1, 2024 • 36:14 Ronna McDaniel, TV News and the Trump Problem

- March 29, 2024 • 48:42 Hamas Took Her, and Still Has Her Husband

- March 28, 2024 • 33:40 The Newest Tech Start-Up Billionaire? Donald Trump.

Hosted by Katrin Bennhold

Featuring Mara Hvistendahl

Produced by Rikki Novetsky and Mooj Zadie

With Rachelle Bonja

Edited by Lisa Chow and Alexandra Leigh Young

Original music by Marion Lozano , Diane Wong , Elisheba Ittoop and Sophia Lanman

Engineered by Chris Wood

Listen and follow The Daily Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

When Elon Musk set up Tesla’s factory in China, he made a bet that brought him cheap parts and capable workers — a bet that made him ultrarich and saved his company.

Mara Hvistendahl, an investigative reporter for The Times, explains why, now, that lifeline may have given China the tools to beat Tesla at its own game.

On today’s episode

Mara Hvistendahl , an investigative reporter for The New York Times.

Background reading

A pivot to China saved Elon Musk. It also bound him to Beijing .

Mr. Musk helped create the Chinese electric vehicle industry. But he is now facing challenges there as well as scrutiny in the West over his reliance on China.

There are a lot of ways to listen to The Daily. Here’s how.

We aim to make transcripts available the next workday after an episode’s publication. You can find them at the top of the page.

Fact-checking by Susan Lee .

The Daily is made by Rachel Quester, Lynsea Garrison, Clare Toeniskoetter, Paige Cowett, Michael Simon Johnson, Brad Fisher, Chris Wood, Jessica Cheung, Stella Tan, Alexandra Leigh Young, Lisa Chow, Eric Krupke, Marc Georges, Luke Vander Ploeg, M.J. Davis Lin, Dan Powell, Sydney Harper, Mike Benoist, Liz O. Baylen, Asthaa Chaturvedi, Rachelle Bonja, Diana Nguyen, Marion Lozano, Corey Schreppel, Rob Szypko, Elisheba Ittoop, Mooj Zadie, Patricia Willens, Rowan Niemisto, Jody Becker, Rikki Novetsky, John Ketchum, Nina Feldman, Will Reid, Carlos Prieto, Ben Calhoun, Susan Lee, Lexie Diao, Mary Wilson, Alex Stern, Dan Farrell, Sophia Lanman, Shannon Lin, Diane Wong, Devon Taylor, Alyssa Moxley, Summer Thomad, Olivia Natt, Daniel Ramirez and Brendan Klinkenberg.

Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly. Special thanks to Sam Dolnick, Paula Szuchman, Lisa Tobin, Larissa Anderson, Julia Simon, Sofia Milan, Mahima Chablani, Elizabeth Davis-Moorer, Jeffrey Miranda, Renan Borelli, Maddy Masiello, Isabella Anderson and Nina Lassam.

Katrin Bennhold is the Berlin bureau chief. A former Nieman fellow at Harvard University, she previously reported from London and Paris, covering a range of topics from the rise of populism to gender. More about Katrin Bennhold

Mara Hvistendahl is an investigative reporter for The Times focused on Asia. More about Mara Hvistendahl

Advertisement

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Tea Garden Labors Of Assam: A Community In Distress

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The main occupation of the Tea garden labour is wage labour. The economic condition is not highly sound among the Tea Garden community. The permanent workers have their own quarters allotted by the owner of that particular Tea garden. This study aims to show the living conditions of the tea garden labourers of Maijan Rajgarh Borline.

1. 43.42% of the total popula tion is employed in the tea ga rden as permanent and casual lab ours. The living standard o f. labourers was very low an d they were very casual regarding maintenance ...

The boundary states that Rajgarh Chotaline is towards east, Assam Medical College on the west, Paltan Bazaar towards north and Maijan T.E is on the south respectively. Objectives of the study:1) To analyse the living conditions of the tea garden labour. 2) To show the socio cultural profile of tea garden labour.

According to the Indian Plantation Labour Act, 1951, the tea garden authorities are mandated to provide the basic amenities of healthcare, education, drinking water, housing, ... While a majority of research on the tea garden workers in India mainly focused on their health/nutritional status contraceptive practice , living, ...

Female-male (FM) worker ratio is the highest in the plantations of Darjeel-. ing hills (1.6) compared to Dooars (1.1) and Terai (1.0) hence emplo ying the highest. number of women workers, but ...

The Assam Human Development Report of 2003, acknowledged the fact that the health status of its tea garden laborers is much below the state average; the state itself is languishing at the bottom.

Tea garden workers in Assam, India continue to face precarious living and working conditions which have led to recent protests by workers' unions and student organisations in Assam. This study examines a survey of over 3,000 tea garden worker respondents in three locations across Assam to understand the material realities of these workers and ...

This study has made an attempt to explore the living conditions of the tea garden workers in Nilgiris district. ... A study on Sarusarai Tea Garden of Johart District of Assam" Research Paper. 2 Raman. Ravi, K. (1986). ... The tea industry is labour intensive and majority of workers are women. Information on households of the workers revealed ...

This paper aims to highlight the precarity of plantation workers of Darjeeling, issues of inaccessibility to proper healthcare and inability to keep ill-health away. It draws from primary research carried out in two tea plantations of Darjeeling, West Bengal. Further, it also underlines the marginalized position of the women workers in the tea ...

In S. Karotemporal & B. Dutta Roy (Eds.), Tea garden labourers in North East India: A multidimensional study on the Adivasis of North East ... Tea plantation labour in India, New Delhi. Google Scholar Khawas, V. (2006, August 15). Not brewing right: Tea in the Darjeeling hills is losing its flavour. ... This research paper is dedicated to the ...

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN MULTIDISCIPLINARY FIELD ISSN - 2455-0620 Volume - 2, Issue - 9, Sept - 2016 Understanding the Economic Lives: The Case of Tea Garden Labourers Minakshi Gogoi - Research Scholar, Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Email - [email protected] Abstract: The tea garden labour ...

A sample of 120 women workers was drawn. The tea garden further had divisions within the estate each corresponding to a distinct residential habitation. In all the divisions, a cluster of households that formed a habitation was known as labour lines. Women workers from each division were randomly selected who resided within the plantation domain.

Gautam Das. C.K.B. College, Teok, Jorat, Assam. The main objective of this paper is to explore the socioeconomic history of women workers in tea garden industries with a view to studying the ...

Tea Garden Labour Situation in Assam. Dr. Putul Borah. Published 2017. Sociology, History. This paper examines the socio-economic and political situation of the tea garden labourers in Assam. The tea garden labourers were migrated from various places of India to work in Assam tea plantations during the colonial as well as post-independent period.

The tea garden labour community is a term used to denote those active tea garden workers and their dependents who reside in labour quarters built inside 800 Tea estates spread across Assam. are the descendants of tribals and backward castes brought by the British colonial planters as indentured labourers from the

Keywords: Tea Garden, Women Labor, Gender Violence, West Bengal, _____ 1. INTRODUCTION: In the mid 18th century, the British introduced a new kind of economy in India, the 'plantation' mainly tea. There was a huge demand for tea in England which was supplied by China in exchange of bullion. But with the Charter Act of 1833, abolished the trade

This paper explores the origin of Tea cultivation in Assam and the status of the tea garden workers. Finally the upliftment of this downtrodden section of the society. Keywords: Assam, tea garden, labourers, education, health Introduction The Indian Tea industry is one of the largest in the world with over 13000 gardens and a total

3 Baishya Dipali, ' History of tea industry and status of tea garden workers of Assam' Published by International Journal of Applied Research, p-555 4 Saikia sangeeta et.al, ' Tea Garden Labours and their living conditions: A study on Sarusarai Tea garden of Jorhat district of Assam' Published by www.internationalseminar.org. p-508

Academia.edu is a platform for academics to share research papers. Prospects and Challenges of Migration on Tea Garden Labourers: An Analysis in . × ... The Directorate for Welfare of Tea and Ex-Tea Garden tribes was established in 1983 and the Assam Tea Labour Welfare Board in 2004 to further the welfare of the tea labour in the state through ...

It has used both quantitative and qualitative research techniques. This paper explores the social formation of tea garden labour in Assam. It also looks at various social protection schemes and analyse the social conditions of tea garden labour. Health and education are taken as vital social indicator of development.

IJCRT2105578 International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts (IJCRT) www.ijcrt.org f326 NORTH BENGAL TEA GARDEN WORKERS ... labour workers even as tea production rose. Thus, the return migration has the potential to re-invigorate the te industry in a way. ... 2020 directing that 50% of the tea garden workforce can remain at work in the gardens,

Kerr followed his father into medicine, and in the last 10 years he has hired a permanent research team that expanded studies on deathbed visions to include interviews with patients receiving ...

India earns Rs. 5385 crores (US$692.1 million) every year from tea export. The basic aim of this paper is to highlight the conditions of tea garden labourers in Darjeeling Hills in the context of ...

29. Hosted by Katrin Bennhold. Featuring Mara Hvistendahl. Produced by Rikki Novetsky and Mooj Zadie. With Rachelle Bonja. Edited by Lisa Chow and Alexandra Leigh Young. Original music by Marion ...

International Journal of Advance Study and Research Work/ Volume 1/Issue 1/April 2018 Tea Garden Labors of Assam: A Community in Distress. Nikunja Sonar Bhuyan Educator Cum independent Researcher Nalbari, Assam (India) Email id.: [email protected] DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1228778 Abstract Assam is famous for tea.