The Research Gap (Literature Gap)

Everything you need to know to find a quality research gap

By: Ethar Al-Saraf (PhD) | Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | November 2022

If you’re just starting out in research, chances are you’ve heard about the elusive research gap (also called a literature gap). In this post, we’ll explore the tricky topic of research gaps. We’ll explain what a research gap is, look at the four most common types of research gaps, and unpack how you can go about finding a suitable research gap for your dissertation, thesis or research project.

Overview: Research Gap 101

- What is a research gap

- Four common types of research gaps

- Practical examples

- How to find research gaps

- Recap & key takeaways

What (exactly) is a research gap?

Well, at the simplest level, a research gap is essentially an unanswered question or unresolved problem in a field, which reflects a lack of existing research in that space. Alternatively, a research gap can also exist when there’s already a fair deal of existing research, but where the findings of the studies pull in different directions , making it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

For example, let’s say your research aims to identify the cause (or causes) of a particular disease. Upon reviewing the literature, you may find that there’s a body of research that points toward cigarette smoking as a key factor – but at the same time, a large body of research that finds no link between smoking and the disease. In that case, you may have something of a research gap that warrants further investigation.

Now that we’ve defined what a research gap is – an unanswered question or unresolved problem – let’s look at a few different types of research gaps.

Types of research gaps

While there are many different types of research gaps, the four most common ones we encounter when helping students at Grad Coach are as follows:

- The classic literature gap

- The disagreement gap

- The contextual gap, and

- The methodological gap

Need a helping hand?

1. The Classic Literature Gap

First up is the classic literature gap. This type of research gap emerges when there’s a new concept or phenomenon that hasn’t been studied much, or at all. For example, when a social media platform is launched, there’s an opportunity to explore its impacts on users, how it could be leveraged for marketing, its impact on society, and so on. The same applies for new technologies, new modes of communication, transportation, etc.

Classic literature gaps can present exciting research opportunities , but a drawback you need to be aware of is that with this type of research gap, you’ll be exploring completely new territory . This means you’ll have to draw on adjacent literature (that is, research in adjacent fields) to build your literature review, as there naturally won’t be very many existing studies that directly relate to the topic. While this is manageable, it can be challenging for first-time researchers, so be careful not to bite off more than you can chew.

2. The Disagreement Gap

As the name suggests, the disagreement gap emerges when there are contrasting or contradictory findings in the existing research regarding a specific research question (or set of questions). The hypothetical example we looked at earlier regarding the causes of a disease reflects a disagreement gap.

Importantly, for this type of research gap, there needs to be a relatively balanced set of opposing findings . In other words, a situation where 95% of studies find one result and 5% find the opposite result wouldn’t quite constitute a disagreement in the literature. Of course, it’s hard to quantify exactly how much weight to give to each study, but you’ll need to at least show that the opposing findings aren’t simply a corner-case anomaly .

3. The Contextual Gap

The third type of research gap is the contextual gap. Simply put, a contextual gap exists when there’s already a decent body of existing research on a particular topic, but an absence of research in specific contexts .

For example, there could be a lack of research on:

- A specific population – perhaps a certain age group, gender or ethnicity

- A geographic area – for example, a city, country or region

- A certain time period – perhaps the bulk of the studies took place many years or even decades ago and the landscape has changed.

The contextual gap is a popular option for dissertations and theses, especially for first-time researchers, as it allows you to develop your research on a solid foundation of existing literature and potentially even use existing survey measures.

Importantly, if you’re gonna go this route, you need to ensure that there’s a plausible reason why you’d expect potential differences in the specific context you choose. If there’s no reason to expect different results between existing and new contexts, the research gap wouldn’t be well justified. So, make sure that you can clearly articulate why your chosen context is “different” from existing studies and why that might reasonably result in different findings.

4. The Methodological Gap

Last but not least, we have the methodological gap. As the name suggests, this type of research gap emerges as a result of the research methodology or design of existing studies. With this approach, you’d argue that the methodology of existing studies is lacking in some way , or that they’re missing a certain perspective.

For example, you might argue that the bulk of the existing research has taken a quantitative approach, and therefore there is a lack of rich insight and texture that a qualitative study could provide. Similarly, you might argue that existing studies have primarily taken a cross-sectional approach , and as a result, have only provided a snapshot view of the situation – whereas a longitudinal approach could help uncover how constructs or variables have evolved over time.

Practical Examples

Let’s take a look at some practical examples so that you can see how research gaps are typically expressed in written form. Keep in mind that these are just examples – not actual current gaps (we’ll show you how to find these a little later!).

Context: Healthcare

Despite extensive research on diabetes management, there’s a research gap in terms of understanding the effectiveness of digital health interventions in rural populations (compared to urban ones) within Eastern Europe.

Context: Environmental Science

While a wealth of research exists regarding plastic pollution in oceans, there is significantly less understanding of microplastic accumulation in freshwater ecosystems like rivers and lakes, particularly within Southern Africa.

Context: Education

While empirical research surrounding online learning has grown over the past five years, there remains a lack of comprehensive studies regarding the effectiveness of online learning for students with special educational needs.

As you can see in each of these examples, the author begins by clearly acknowledging the existing research and then proceeds to explain where the current area of lack (i.e., the research gap) exists.

How To Find A Research Gap

Now that you’ve got a clearer picture of the different types of research gaps, the next question is of course, “how do you find these research gaps?” .

Well, we cover the process of how to find original, high-value research gaps in a separate post . But, for now, I’ll share a basic two-step strategy here to help you find potential research gaps.

As a starting point, you should find as many literature reviews, systematic reviews and meta-analyses as you can, covering your area of interest. Additionally, you should dig into the most recent journal articles to wrap your head around the current state of knowledge. It’s also a good idea to look at recent dissertations and theses (especially doctoral-level ones). Dissertation databases such as ProQuest, EBSCO and Open Access are a goldmine for this sort of thing. Importantly, make sure that you’re looking at recent resources (ideally those published in the last year or two), or the gaps you find might have already been plugged by other researchers.

Once you’ve gathered a meaty collection of resources, the section that you really want to focus on is the one titled “ further research opportunities ” or “further research is needed”. In this section, the researchers will explicitly state where more studies are required – in other words, where potential research gaps may exist. You can also look at the “ limitations ” section of the studies, as this will often spur ideas for methodology-based research gaps.

By following this process, you’ll orient yourself with the current state of research , which will lay the foundation for you to identify potential research gaps. You can then start drawing up a shortlist of ideas and evaluating them as candidate topics . But remember, make sure you’re looking at recent articles – there’s no use going down a rabbit hole only to find that someone’s already filled the gap 🙂

Let’s Recap

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this post. Here are the key takeaways:

- A research gap is an unanswered question or unresolved problem in a field, which reflects a lack of existing research in that space.

- The four most common types of research gaps are the classic literature gap, the disagreement gap, the contextual gap and the methodological gap.

- To find potential research gaps, start by reviewing recent journal articles in your area of interest, paying particular attention to the FRIN section .

If you’re keen to learn more about research gaps and research topic ideation in general, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach Blog . Alternatively, if you’re looking for 1-on-1 support with your dissertation, thesis or research project, be sure to check out our private coaching service .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

32 Comments

This post is REALLY more than useful, Thank you very very much

Very helpful specialy, for those who are new for writing a research! So thank you very much!!

I found it very helpful article. Thank you.

Just at the time when I needed it, really helpful.

Very helpful and well-explained. Thank you

VERY HELPFUL

We’re very grateful for your guidance, indeed we have been learning a lot from you , so thank you abundantly once again.

hello brother could you explain to me this question explain the gaps that researchers are coming up with ?

Am just starting to write my research paper. your publication is very helpful. Thanks so much

How to cite the author of this?

your explanation very help me for research paper. thank you

Very important presentation. Thanks.

Best Ideas. Thank you.

I found it’s an excellent blog to get more insights about the Research Gap. I appreciate it!

Kindly explain to me how to generate good research objectives.

This is very helpful, thank you

How to tabulate research gap

Very helpful, thank you.

Thanks a lot for this great insight!

This is really helpful indeed!

This article is really helpfull in discussing how will we be able to define better a research problem of our interest. Thanks so much.

Reading this just in good time as i prepare the proposal for my PhD topic defense.

Very helpful Thanks a lot.

Thank you very much

This was very timely. Kudos

Great one! Thank you all.

Thank you very much.

This is so enlightening. Disagreement gap. Thanks for the insight.

How do I Cite this document please?

Research gap about career choice given me Example bro?

I found this information so relevant as I am embarking on a Masters Degree. Thank you for this eye opener. It make me feel I can work diligently and smart on my research proposal.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to Identify

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to Identify

Table of Contents

Research Gap

Definition:

Research gap refers to an area or topic within a field of study that has not yet been extensively researched or is yet to be explored. It is a question, problem or issue that has not been addressed or resolved by previous research.

How to Identify Research Gap

Identifying a research gap is an essential step in conducting research that adds value and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. Research gap requires critical thinking, creativity, and a thorough understanding of the existing literature . It is an iterative process that may require revisiting and refining your research questions and ideas multiple times.

Here are some steps that can help you identify a research gap:

- Review existing literature: Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature in your research area. This will help you identify what has already been studied and what gaps still exist.

- Identify a research problem: Identify a specific research problem or question that you want to address.

- Analyze existing research: Analyze the existing research related to your research problem. This will help you identify areas that have not been studied, inconsistencies in the findings, or limitations of the previous research.

- Brainstorm potential research ideas : Based on your analysis, brainstorm potential research ideas that address the identified gaps.

- Consult with experts: Consult with experts in your research area to get their opinions on potential research ideas and to identify any additional gaps that you may have missed.

- Refine research questions: Refine your research questions and hypotheses based on the identified gaps and potential research ideas.

- Develop a research proposal: Develop a research proposal that outlines your research questions, objectives, and methods to address the identified research gap.

Types of Research Gap

There are different types of research gaps that can be identified, and each type is associated with a specific situation or problem. Here are the main types of research gaps and their explanations:

Theoretical Gap

This type of research gap refers to a lack of theoretical understanding or knowledge in a particular area. It can occur when there is a discrepancy between existing theories and empirical evidence or when there is no theory that can explain a particular phenomenon. Identifying theoretical gaps can lead to the development of new theories or the refinement of existing ones.

Empirical Gap

An empirical gap occurs when there is a lack of empirical evidence or data in a particular area. It can happen when there is a lack of research on a specific topic or when existing research is inadequate or inconclusive. Identifying empirical gaps can lead to the development of new research studies to collect data or the refinement of existing research methods to improve the quality of data collected.

Methodological Gap

This type of research gap refers to a lack of appropriate research methods or techniques to answer a research question. It can occur when existing methods are inadequate, outdated, or inappropriate for the research question. Identifying methodological gaps can lead to the development of new research methods or the modification of existing ones to better address the research question.

Practical Gap

A practical gap occurs when there is a lack of practical applications or implementation of research findings. It can occur when research findings are not implemented due to financial, political, or social constraints. Identifying practical gaps can lead to the development of strategies for the effective implementation of research findings in practice.

Knowledge Gap

This type of research gap occurs when there is a lack of knowledge or information on a particular topic. It can happen when a new area of research is emerging, or when research is conducted in a different context or population. Identifying knowledge gaps can lead to the development of new research studies or the extension of existing research to fill the gap.

Examples of Research Gap

Here are some examples of research gaps that researchers might identify:

- Theoretical Gap Example : In the field of psychology, there might be a theoretical gap related to the lack of understanding of the relationship between social media use and mental health. Although there is existing research on the topic, there might be a lack of consensus on the mechanisms that link social media use to mental health outcomes.

- Empirical Gap Example : In the field of environmental science, there might be an empirical gap related to the lack of data on the long-term effects of climate change on biodiversity in specific regions. Although there might be some studies on the topic, there might be a lack of data on the long-term effects of climate change on specific species or ecosystems.

- Methodological Gap Example : In the field of education, there might be a methodological gap related to the lack of appropriate research methods to assess the impact of online learning on student outcomes. Although there might be some studies on the topic, existing research methods might not be appropriate to assess the complex relationships between online learning and student outcomes.

- Practical Gap Example: In the field of healthcare, there might be a practical gap related to the lack of effective strategies to implement evidence-based practices in clinical settings. Although there might be existing research on the effectiveness of certain practices, they might not be implemented in practice due to various barriers, such as financial constraints or lack of resources.

- Knowledge Gap Example: In the field of anthropology, there might be a knowledge gap related to the lack of understanding of the cultural practices of indigenous communities in certain regions. Although there might be some research on the topic, there might be a lack of knowledge about specific cultural practices or beliefs that are unique to those communities.

Examples of Research Gap In Literature Review, Thesis, and Research Paper might be:

- Literature review : A literature review on the topic of machine learning and healthcare might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the use of machine learning for early detection of rare diseases.

- Thesis : A thesis on the topic of cybersecurity might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the effectiveness of artificial intelligence in detecting and preventing cyber attacks.

- Research paper : A research paper on the topic of natural language processing might identify a research gap in the lack of studies that investigate the use of natural language processing techniques for sentiment analysis in non-English languages.

How to Write Research Gap

By following these steps, you can effectively write about research gaps in your paper and clearly articulate the contribution that your study will make to the existing body of knowledge.

Here are some steps to follow when writing about research gaps in your paper:

- Identify the research question : Before writing about research gaps, you need to identify your research question or problem. This will help you to understand the scope of your research and identify areas where additional research is needed.

- Review the literature: Conduct a thorough review of the literature related to your research question. This will help you to identify the current state of knowledge in the field and the gaps that exist.

- Identify the research gap: Based on your review of the literature, identify the specific research gap that your study will address. This could be a theoretical, empirical, methodological, practical, or knowledge gap.

- Provide evidence: Provide evidence to support your claim that the research gap exists. This could include a summary of the existing literature, a discussion of the limitations of previous studies, or an analysis of the current state of knowledge in the field.

- Explain the importance: Explain why it is important to fill the research gap. This could include a discussion of the potential implications of filling the gap, the significance of the research for the field, or the potential benefits to society.

- State your research objectives: State your research objectives, which should be aligned with the research gap you have identified. This will help you to clearly articulate the purpose of your study and how it will address the research gap.

Importance of Research Gap

The importance of research gaps can be summarized as follows:

- Advancing knowledge: Identifying research gaps is crucial for advancing knowledge in a particular field. By identifying areas where additional research is needed, researchers can fill gaps in the existing body of knowledge and contribute to the development of new theories and practices.

- Guiding research: Research gaps can guide researchers in designing studies that fill those gaps. By identifying research gaps, researchers can develop research questions and objectives that are aligned with the needs of the field and contribute to the development of new knowledge.

- Enhancing research quality: By identifying research gaps, researchers can avoid duplicating previous research and instead focus on developing innovative research that fills gaps in the existing body of knowledge. This can lead to more impactful research and higher-quality research outputs.

- Informing policy and practice: Research gaps can inform policy and practice by highlighting areas where additional research is needed to inform decision-making. By filling research gaps, researchers can provide evidence-based recommendations that have the potential to improve policy and practice in a particular field.

Applications of Research Gap

Here are some potential applications of research gap:

- Informing research priorities: Research gaps can help guide research funding agencies and researchers to prioritize research areas that require more attention and resources.

- Identifying practical implications: Identifying gaps in knowledge can help identify practical applications of research that are still unexplored or underdeveloped.

- Stimulating innovation: Research gaps can encourage innovation and the development of new approaches or methodologies to address unexplored areas.

- Improving policy-making: Research gaps can inform policy-making decisions by highlighting areas where more research is needed to make informed policy decisions.

- Enhancing academic discourse: Research gaps can lead to new and constructive debates and discussions within academic communities, leading to more robust and comprehensive research.

Advantages of Research Gap

Here are some of the advantages of research gap:

- Identifies new research opportunities: Identifying research gaps can help researchers identify areas that require further exploration, which can lead to new research opportunities.

- Improves the quality of research: By identifying gaps in current research, researchers can focus their efforts on addressing unanswered questions, which can improve the overall quality of research.

- Enhances the relevance of research: Research that addresses existing gaps can have significant implications for the development of theories, policies, and practices, and can therefore increase the relevance and impact of research.

- Helps avoid duplication of effort: Identifying existing research can help researchers avoid duplicating efforts, saving time and resources.

- Helps to refine research questions: Research gaps can help researchers refine their research questions, making them more focused and relevant to the needs of the field.

- Promotes collaboration: By identifying areas of research that require further investigation, researchers can collaborate with others to conduct research that addresses these gaps, which can lead to more comprehensive and impactful research outcomes.

Disadvantages of Research Gap

While research gaps can be advantageous, there are also some potential disadvantages that should be considered:

- Difficulty in identifying gaps: Identifying gaps in existing research can be challenging, particularly in fields where there is a large volume of research or where research findings are scattered across different disciplines.

- Lack of funding: Addressing research gaps may require significant resources, and researchers may struggle to secure funding for their work if it is perceived as too risky or uncertain.

- Time-consuming: Conducting research to address gaps can be time-consuming, particularly if the research involves collecting new data or developing new methods.

- Risk of oversimplification: Addressing research gaps may require researchers to simplify complex problems, which can lead to oversimplification and a failure to capture the complexity of the issues.

- Bias : Identifying research gaps can be influenced by researchers’ personal biases or perspectives, which can lead to a skewed understanding of the field.

- Potential for disagreement: Identifying research gaps can be subjective, and different researchers may have different views on what constitutes a gap in the field, leading to disagreements and debate.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Identifying Research Gaps to Pursue Innovative Research

This article is an excerpt from a lecture given by my Ph.D. guide, a researcher in public health. She advised us on how to identify research gaps to pursue innovative research in our fields.

What is a Research Gap?

Today we are talking about the research gap: what is it, how to identify it, and how to make use of it so that you can pursue innovative research. Now, how many of you have ever felt you had discovered a new and exciting research question , only to find that it had already been written about? I have experienced this more times than I can count. Graduate studies come with pressure to add new knowledge to the field. We can contribute to the progress and knowledge of humanity. To do this, we need to first learn to identify research gaps in the existing literature.

A research gap is, simply, a topic or area for which missing or insufficient information limits the ability to reach a conclusion for a question. It should not be confused with a research question, however. For example, if we ask the research question of what the healthiest diet for humans is, we would find many studies and possible answers to this question. On the other hand, if we were to ask the research question of what are the effects of antidepressants on pregnant women, we would not find much-existing data. This is a research gap. When we identify a research gap, we identify a direction for potentially new and exciting research.

How to Identify Research Gap?

Considering the volume of existing research, identifying research gaps can seem overwhelming or even impossible. I don’t have time to read every paper published on public health. Similarly, you guys don’t have time to read every paper. So how can you identify a research gap?

There are different techniques in various disciplines, but we can reduce most of them down to a few steps, which are:

- Identify your key motivating issue/question

- Identify key terms associated with this issue

- Review the literature, searching for these key terms and identifying relevant publications

- Review the literature cited by the key publications which you located in the above step

- Identify issues not addressed by the literature relating to your critical motivating issue

It is the last step which we all find the most challenging. It can be difficult to figure out what an article is not saying. I like to keep a list of notes of biased or inconsistent information. You could also track what authors write as “directions for future research,” which often can point us towards the existing gaps.

Different Types of Research Gaps

Identifying research gaps is an essential step in conducting research, as it helps researchers to refine their research questions and to focus their research efforts on areas where there is a need for more knowledge or understanding.

1. Knowledge gaps

These are gaps in knowledge or understanding of a subject, where more research is needed to fill the gaps. For example, there may be a lack of understanding of the mechanisms behind a particular disease or how a specific technology works.

2. Conceptual gaps

These are gaps in the conceptual framework or theoretical understanding of a subject. For example, there may be a need for more research to understand the relationship between two concepts or to refine a theoretical framework.

3. Methodological gaps

These are gaps in the methods used to study a particular subject. For example, there may be a need for more research to develop new research methods or to refine existing methods to address specific research questions.

4. Data gaps

These are gaps in the data available on a particular subject. For example, there may be a need for more research to collect data on a specific population or to develop new measures to collect data on a particular construct.

5. Practical gaps

These are gaps in the application of research findings to practical situations. For example, there may be a need for more research to understand how to implement evidence-based practices in real-world settings or to identify barriers to implementing such practices.

Examples of Research Gap

Limited understanding of the underlying mechanisms of a disease:.

Despite significant research on a particular disease, there may be a lack of understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the disease. For example, although much research has been done on Alzheimer’s disease, the exact mechanisms that lead to the disease are not yet fully understood.

Inconsistencies in the findings of previous research:

When previous research on a particular topic has inconsistent findings, there may be a need for further research to clarify or resolve these inconsistencies. For example, previous research on the effectiveness of a particular treatment for a medical condition may have produced inconsistent findings, indicating a need for further research to determine the true effectiveness of the treatment.

Limited research on emerging technologies:

As new technologies emerge, there may be limited research on their applications, benefits, and potential drawbacks. For example, with the increasing use of artificial intelligence in various industries, there is a need for further research on the ethical, legal, and social implications of AI.

How to Deal with Literature Gap?

Once you have identified the literature gaps, it is critical to prioritize. You may find many questions which remain to be answered in the literature. Often one question must be answered before the next can be addressed. In prioritizing the gaps, you have identified, you should consider your funding agency or stakeholders, the needs of the field, and the relevance of your questions to what is currently being studied. Also, consider your own resources and ability to conduct the research you’re considering. Once you have done this, you can narrow your search down to an appropriate question.

Tools to Help Your Search

There are thousands of new articles published every day, and staying up to date on the literature can be overwhelming. You should take advantage of the technology that is available. Some services include PubCrawler , Feedly , Google Scholar , and PubMed updates. Stay up to date on social media forums where scholars share new discoveries, such as Twitter. Reference managers such as Mendeley can help you keep your references well-organized. I personally have had success using Google Scholar and PubMed to stay current on new developments and track which gaps remain in my personal areas of interest.

The most important thing I want to impress upon you today is that you will struggle to choose a research topic that is innovative and exciting if you don’t know the existing literature well. This is why identifying research gaps starts with an extensive and thorough literature review . But give yourself some boundaries. You don’t need to read every paper that has ever been written on a topic. You may find yourself thinking you’re on the right track and then suddenly coming across a paper that you had intended to write! It happens to everyone- it happens to me quite often. Don’t give up- keep reading and you’ll find what you’re looking for.

Class dismissed!

How do you identify research gaps? Share your thoughts in the comments section below.

Frequently Asked Questions

A research gap can be identified by looking for a topic or area with missing or insufficient information that limits the ability to reach a conclusion for a question.

Identifying a research gap is important as it provides a direction for potentially new research or helps bridge the gap in existing literature.

Gap in research is a topic or area with missing or insufficient information. A research gap limits the ability to reach a conclusion for a question.

Thank u for your suggestion.

Very useful tips specially for a beginner

Thank you. This is helpful. I find that I’m overwhelmed with literatures. As I read on a particular topic, and in a particular direction I find that other conflicting issues, topic a and ideas keep popping up, making me more confused.

I am very grateful for your advice. It’s just on point.

The clearest, exhaustive, and brief explanation I have ever read.

Thanks for sharing

Thank you very much.The work is brief and understandable

Thank you it is very informative

Thanks for sharing this educative article

Thank you for such informative explanation.

Great job smart guy! Really outdid yourself!

Nice one! I thank you for this as it is just what I was looking for!😃🤟

Thank you so much for this. Much appreciated

Thank you so much.

Thankyou for ur briefing…its so helpful

Thank you so much .I’ved learn a lot from this.❤️

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right approach

The process of choosing the right research design can put ourselves at the crossroads of…

- Career Corner

Unlocking the Power of Networking in Academic Conferences

Embarking on your first academic conference experience? Fear not, we got you covered! Academic conferences…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Research recommendations play a crucial role in guiding scholars and researchers toward fruitful avenues of…

- AI in Academia

Disclosing the Use of Generative AI: Best practices for authors in manuscript preparation

The rapid proliferation of generative and other AI-based tools in research writing has ignited an…

Intersectionality in Academia: Dealing with diverse perspectives

Meritocracy and Diversity in Science: Increasing inclusivity in STEM education

Avoiding the AI Trap: Pitfalls of relying on ChatGPT for PhD applications

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- [email protected]

- Shapiro Library

- SNHU Library Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: What is a research gap and how do I find one?

- 7 Academic Integrity & Plagiarism

- 64 Academic Support, Writing Help, & Presentation Help

- 29 Access/Remote Access

- 7 Accessibility

- 9 Building/Facilities

- 7 Career/Job Information

- 26 Catalog/Print Books

- 26 Circulation

- 129 Citing Sources

- 14 Copyright

- 311 Databases

- 24 Directions/Location

- 18 Faculty Resources/Needs

- 7 Hours/Contacts

- 2 Innovation Lab & Makerspace/3D Printing

- 25 Interlibrary Loan

- 43 IT/Computer/Printing Support

- 3 Library Instruction

- 39 Library Technology Help

- 6 Multimedia

- 17 Online Programs

- 19 Periodicals

- 25 Policies

- 8 RefWorks/Citation Managers

- 4 Research Guides (LibGuides)

- 216 Research Help

- 23 University Services

Last Updated: Jun 27, 2023 Views: 475194

What is a research gap.

A research gap is a question or a problem that has not been answered by any of the existing studies or research within your field. Sometimes, a research gap exists when there is a concept or new idea that hasn't been studied at all. Sometimes you'll find a research gap if all the existing research is outdated and in need of new/updated research (studies on Internet use in 2001, for example). Or, perhaps a specific population has not been well studied (perhaps there are plenty of studies on teenagers and video games, but not enough studies on toddlers and video games, for example). These are just a few examples, but any research gap you find is an area where more studies and more research need to be conducted. Please view this video clip from our Sage Research Methods database for more helpful information: How Do You Identify Gaps in Literature?

How do I find one?

It will take a lot of research and reading. You'll need to be very familiar with all the studies that have already been done, and what those studies contributed to the overall body of knowledge about that topic. Make a list of any questions you have about your topic and then do some research to see if those questions have already been answered satisfactorily. If they haven't, perhaps you've discovered a gap! Here are some strategies you can use to make the most of your time:

- One useful trick is to look at the “suggestions for future research” or conclusion section of existing studies on your topic. Many times, the authors will identify areas where they think a research gap exists, and what studies they think need to be done in the future.

- As you are researching, you will most likely come across citations for seminal works in your research field. These are the research studies that you see mentioned again and again in the literature. In addition to finding those and reading them, you can use a database like Web of Science to follow the research trail and discover all the other articles that have cited these. See the FAQ: I found the perfect article for my paper. How do I find other articles and books that have cited it? on how to do this. One way to quickly track down these seminal works is to use a database like SAGE Navigator, a social sciences literature review tool. It is one of the products available via our SAGE Knowledge database.

- In the PsycINFO and PsycARTICLES databases, you can select literature review, systematic review, and meta analysis under the Methodology section in the advanced search to quickly locate these. See the FAQ: Where can I find a qualitative or quantitative study? for more information on how to find the Methodology section in these two databases.

- In CINAHL , you can select Systematic review under the Publication Type field in the advanced search.

- In Web of Science , check the box beside Review under the Document Type heading in the “Refine Results” sidebar to the right of the list of search hits.

- If the database you are searching does not offer a way to filter your results by document type, publication type, or methodology in the advanced search, you can include these phrases (“literature reviews,” meta-analyses, or “systematic reviews”) in your search string. For example, “video games” AND “literature reviews” could be a possible search that you could try.

Please give these suggestions a try and contact a librarian for additional assistance.

Content authored by: GS

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 381 No 152

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) are a self-serve option for users to search and find answers to their questions.

Use the search box above to type your question to search for an answer or browse existing FAQs by group, topic, etc.

Tell Me More

Link to Question Form

More assistance.

Submit a Question

Related FAQs

- Research Process

What is a Research Gap

- 3 minute read

- 286.1K views

Table of Contents

If you are a young researcher, or even still finishing your studies, you’ll probably notice that your academic environment revolves around certain research topics, probably linked to your department or to the interest of your mentor and direct colleagues. For example, if your department is currently doing research in nanotechnology applied to medicine, it is only natural that you feel compelled to follow this line of research. Hopefully, it’s something you feel familiar with and interested in – although you might take your own twists and turns along your career.

Many scientists end up continuing their academic legacy during their professional careers, writing about their own practical experiences in the field and adapting classic methodologies to a present context. However, each and every researcher dreams about being a pioneer in a subject one day, by discovering a topic that hasn’t been approached before by any other scientist. This is a research gap.

Research gaps are particularly useful for the advance of science, in general. Finding a research gap and having the means to develop a complete and sustained study on it can be very rewarding for the scientist (or team of scientists), not to mention how its new findings can positively impact our whole society.

How to Find a Gap in Research

How many times have you felt that you have finally formulated THAT new and exciting question, only to find out later that it had been addressed before? Probably more times than you can count.

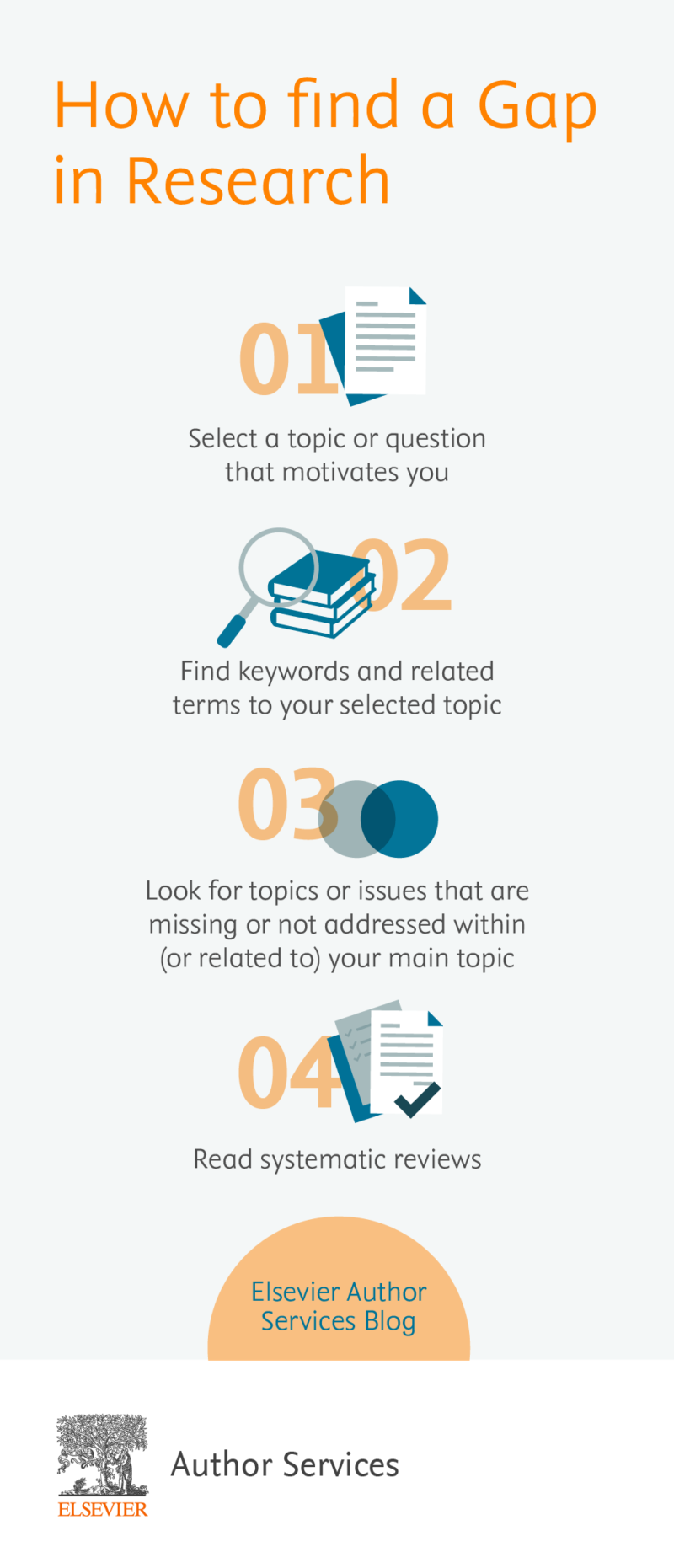

There are some steps you can take to help identify research gaps, since it is impossible to go through all the information and research available nowadays:

- Select a topic or question that motivates you: Research can take a long time and surely a large amount of physical, intellectual and emotional effort, therefore choose a topic that can keep you motivated throughout the process.

- Find keywords and related terms to your selected topic: Besides synthesizing the topic to its essential core, this will help you in the next step.

- Use the identified keywords to search literature: From your findings in the above step, identify relevant publications and cited literature in those publications.

- Look for topics or issues that are missing or not addressed within (or related to) your main topic.

- Read systematic reviews: These documents plunge deeply into scholarly literature and identify trends and paradigm shifts in fields of study. Sometimes they reveal areas or topics that need more attention from researchers and scientists.

Keeping track of all the new literature being published every day is an impossible mission. Remember that there is technology to make your daily tasks easier, and reviewing literature can be one of them. Some online databases offer up-to-date publication lists with quite effective search features:

- Elsevier’s Scope

- Google Scholar

Of course, these tools may be more or less effective depending on knowledge fields. There might be even better ones for your specific topic of research; you can learn about them from more experienced colleagues or mentors.

Find out how FINER research framework can help you formulate your research question.

Literature Gap

The expression “literature gap” is used with the same intention as “research gap.” When there is a gap in the research itself, there will also naturally be a gap in the literature. Nevertheless, it is important to stress out the importance of language or text formulations that can help identify a research/literature gap or, on the other hand, making clear that a research gap is being addressed.

When looking for research gaps across publications you may have noticed sentences like:

…has/have not been… (studied/reported/elucidated) …is required/needed… …the key question is/remains… …it is important to address…

These expressions often indicate gaps; issues or topics related to the main question that still hasn’t been subject to a scientific study. Therefore, it is important to take notice of them: who knows if one of these sentences is hiding your way to fame.

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

- Manuscript Review

Systematic Review VS Meta-Analysis

Literature Review in Research Writing

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Advertisement

Methods for Identifying Health Research Gaps, Needs, and Priorities: a Scoping Review

- Systematic Review

- Published: 08 November 2021

- Volume 37 , pages 198–205, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Eunice C. Wong PhD ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8640-4548 1 ,

- Alicia R. Maher MD 1 ,

- Aneesa Motala BA 1 , 2 ,

- Rachel Ross MPH 1 ,

- Olamigoke Akinniranye MA 1 ,

- Jody Larkin MS 1 &

- Susanne Hempel PhD 1 , 2

3363 Accesses

9 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Well-defined, systematic, and transparent processes to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities are vital to ensuring that available funds target areas with the greatest potential for impact.

The purpose of this review is to characterize methods conducted or supported by research funding organizations to identify health research gaps, needs, or priorities.

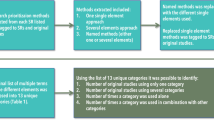

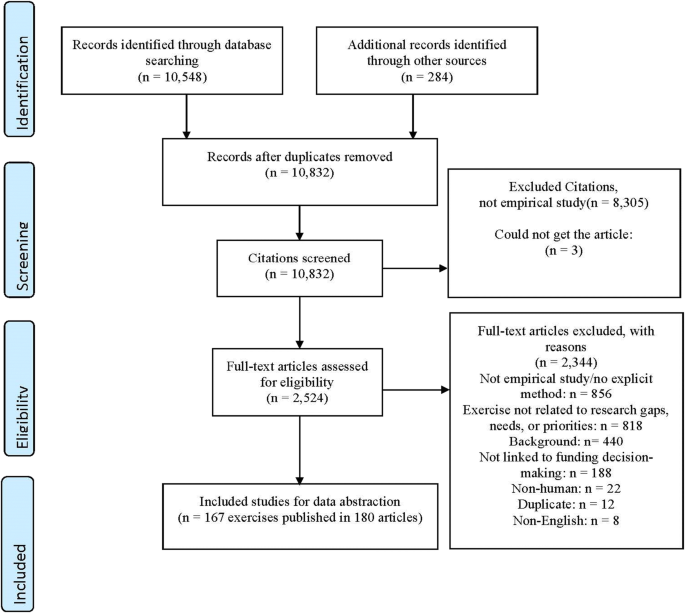

We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and the Web of Science up to September 2019. Eligible studies reported on methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities that had been conducted or supported by research funding organizations. Using a published protocol, we extracted data on the method, criteria, involvement of stakeholders, evaluations, and whether the method had been replicated (i.e., used in other studies).

Among 10,832 citations, 167 studies were eligible for full data extraction. More than half of the studies employed methods to identify both needs and priorities, whereas about a quarter of studies focused singularly on identifying gaps (7%), needs (6%), or priorities (14%) only. The most frequently used methods were the convening of workshops or meetings (37%), quantitative methods (32%), and the James Lind Alliance approach, a multi-stakeholder research needs and priority setting process (28%). The most widely applied criteria were importance to stakeholders (72%), potential value (29%), and feasibility (18%). Stakeholder involvement was most prominent among clinicians (69%), researchers (66%), and patients and the public (59%). Stakeholders were identified through stakeholder organizations (51%) and purposive (26%) and convenience sampling (11%). Only 4% of studies evaluated the effectiveness of the methods and 37% employed methods that were reproducible and used in other studies.

To ensure optimal targeting of funds to meet the greatest areas of need and maximize outcomes, a much more robust evidence base is needed to ascertain the effectiveness of methods used to identify research gaps, needs, and priorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

A protocol for ongoing systematic scoping reviews of World Trade Center Health research

What do we know about evidence-informed priority setting processes to set population-level health-research agendas: an overview of reviews

Lack of systematicity in research prioritisation processes — a scoping review of evidence syntheses

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Well-defined, systematic, and transparent methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities are vital to ensuring that available funds target areas with the greatest potential for impact. 1 , 2 As defined in the literature, 3 , 4 research gaps are defined as areas or topics in which the ability to draw a conclusion for a given question is prevented by insufficient evidence. Research gaps are not necessarily synonymous with research needs , which are those knowledge gaps that significantly inhibit the decision-making ability of key stakeholders, who are end users of research, such as patients, clinicians, and policy makers. The selection of research priorities is often necessary when all identified research gaps or needs cannot be pursued because of resource constraints. Methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities (from herein referred to as gaps, needs, priorities) can be multi-varied and there does not appear to be general consensus on best practices. 3 , 5

Several published reviews highlight the diverse methods that have been used to identify gaps and priorities. In a review of methods used to identify gaps from systematic reviews, Robinson et al. noted the wide range of organizing principles that were employed in published literature between 2001 and 2009 (e.g., care pathway, decision tree, and patient, intervention, comparison, outcome framework,). 6 In a more recent review spanning 2007 to 2017, Nyanchoka et al. found that the vast majority of studies with a primary focus on the identification of gaps (83%) relied solely on knowledge synthesis methods (e.g., systematic review, scoping review, evidence mapping, literature review). A much smaller proportion (9%) relied exclusively on primary research methods (i.e., quantitative survey, qualitative study). 7

With respect to research priorities, in a review limited to a PubMed database search covering the period from 2001 to 2014, Yoshida documented a wide range of methods to identify priorities including the use of not only knowledge synthesis (i.e., literature reviews) and primary research methods (i.e., surveys) but also multi-stage, structured methods such as Delphi, Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI), James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership (JLA PSP), and Essential National Health Research (ENHR). 2 The CHNRI method, originally developed for the purpose of setting global child health research priorities, typically employs researchers and experts to specify a long list of research questions, the criteria that will be used to prioritize research questions, and the technical scoring of research questions using the defined criteria. 8 During the latter stages, non-expert stakeholders’ input are incorporated by using their ratings of the importance of selected criteria to weight the technical scores. The ENHR method, initially designed for health research priority setting at the national level, involves researchers, decision-makers, health service providers, and communities throughout the entire process of identifying and prioritizing research topics. 9 The JLA PSP method convenes patients, carers, and clinicians to equally and jointly identify questions about healthcare that cannot be answered by existing evidence that are important to all groups (i.e., research needs). 10 The identified research needs are then prioritized by the groups resulting in a final list (often a top 10) of research priorities. Non-clinical researchers are excluded from voting on research needs or priorities but can be involved in other processes (e.g., knowledge synthesis). CHNRI, ENHR, and JLA PSP usually employ a mix of knowledge synthesis and primary research methods to first identify a set of gaps or needs that are then prioritized. Thus, even though CHNRI, ENHR, and JLA PSP have been referred to as priority setting methods, they actually consist of a gaps or needs identification stage that feeds into a research prioritization stage.

Nyanchoka et al.’s review found that the majority of studies focused on the identification of gaps alone (65%), whereas the remaining studies focused either on research priorities alone (17%) or on both gaps and priorities (19%). 7 In an update to Robinson et al.’s review, 6 Carey et al. reviewed the literature between 2010 and 2011 and observed that the studies conducted during this latter period of time focused more on research priorities than gaps and had increased stakeholder involvement, and that none had evaluated the reproducibility of the methods. 11

The increasing development and diversity of formal processes and methods to identify gaps and priorities are indicative of a developing field. 2 , 12 To facilitate more standardized and systematic processes, other important areas warrant further investigation. Prior reviews did not distinguish between the identification of gaps versus research needs. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence-based Practice Center (AHRQ EPC) Program issued a series of method papers related to establishing research needs as part of comparative effectiveness research. 13 , 14 , 15 The AHRQ EPC Program defined research needs as “evidence gaps” identified within systematic reviews that are prioritized by stakeholders according to their potential impact on practice or care. 16 Furthermore, Nyanchoka et al. relied on author designations to classify studies as focusing on gaps versus research priorities and noted that definitions of gaps varied across studies, highlighting the need to apply consistent taxonomy when categorizing studies in reviews. 7 Given the rise in the use of stakeholders in both gaps and prioritization exercises, a greater understanding of the range of practices involving stakeholders is also needed. This includes the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders (e.g., consultants versus final decision-makers), the composition of stakeholders (e.g., non-research clinicians, patients, caregivers, policymakers), and the methods used to recruit stakeholders. The lack of consensus of best practices also highlights the importance of learning the extent to which evaluations to determine the effectiveness of gaps, needs, and prioritization exercises have been conducted, and if so, what were the resultant outcomes.

To better inform efforts and organizations that fund health research, we conducted a scoping review of methods used to identify gaps, needs, and priorities that were linked to potential or actual health research funding decision-making. Hence, this scoping review was limited to studies in which the identification of health research gaps, needs, or priorities was supported or conducted by funding organizations to address the following questions 1 : What are the characteristics of methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities? and 2 To what extent have evaluations of the impact of these methods been conducted? Given that scoping reviews may be executed to characterize the ways an area of research has been conducted, 17 , 18 this approach is appropriate for the broad nature of this study’s aims.

Protocol and Registration

We employed methods that conform to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. 19 See Appendix A in the Supplementary Information. The scoping review protocol is registered with the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/5zjqx/ ).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies published in English that described methods to identify health research gaps, needs, or priorities that were supported or conducted by funding organizations were eligible for inclusion. We excluded studies that reported only the results of the exercise (e.g., list of priorities) absent of information on the methods used. We also excluded studies involving evidence synthesis (e.g., literature or systematic reviews) that were solely descriptive and did not employ an explicit method to identify research gaps, needs, or priorities.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

We searched the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Our database search also included an update of the Nyanchoka et al. scoping review, which entailed executing their database searches for the time period following 2017 (the study’s search end date). 7 Nyanchoka et al. did not include database searches for research needs. The electronic database search and scoping review update were completed in August and September 2019, respectively . The search strategy employed for each of the databases is presented in Appendix B in the Supplementary Information.

Selection of Sources of Evidence and Data Charting Process

Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts and full-text publications. Citations that one or both reviewers considered potentially eligible were retrieved for full-text review. Relevant background articles and scoping and systematic reviews were reference mined to screen for eligible studies. Full-text publications were screened against detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data was extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion by the review team.

Information on study characteristics were extracted from each article including the aims of the exercise (i.e., gaps, needs, priorities, or a combination) and health condition (i.e., physical or psychological). Based on definitions in the literature, 3 , 4 , 5 the aims of the exercise were coded according to the activities that were conducted, which may not have always corresponded with the study authors’ labeling of the exercises. For instance, the JLA PSP method is often described as a priority exercise but we categorized it as a needs and priority exercise. Priority exercises can be preceded by exercises to identify gaps or needs, which then feed into the priority exercise such as in JLA PSP; however, standalone priority exercises can also be conducted (e.g., stakeholders prioritize an existing list of emerging diseases).

For each type of exercise, information on the methods were recorded. An initial list of methods was created based on previous reviews. 9 , 12 , 20 During the data extraction process, any methods not included in the initial list were subsequently added. If more than one exercise was reported within an article (e.g., gaps and priorities), information was extracted for each exercise separately. Reviewers extracted the following information: methods employed (e.g., qualitative, quantitative), criteria used (e.g., disease burden, importance to stakeholders), stakeholder involvement (e.g., stakeholder composition, method for identifying stakeholders), and whether an evaluation was conducted on the effectiveness of the exercise (see Appendix C in the Supplementary Information for full data extraction form).

Synthesis of results entailed quantitative descriptives of study characteristics (e.g., proportion of studies by aims of exercise) and characteristics of methods employed across all studies and by each type of study (e.g., gaps, needs, priorities).

The electronic database search yielded a total of 10,548 titles. Another 284 articles were identified after searching the reference lists of full-text publications, including three systematic reviews 21 , 22 , 23 and one scoping review 24 that had met eligibility criteria. Moreover, a total of 99 publications designated as relevant background articles were also reference mined to screen for eligible studies. We conducted full-text screening for 2524 articles, which resulted in 2344 exclusions (440 studies were designated as background articles). A total of 167 exercises related to the identification of gaps, needs, or priorities that were supported or conducted by a research funding organization were described across 180 publications and underwent full data extraction. See Figure 1 for the flow diagram of our search strategy and reasons for exclusion.

Literature flow

Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

Among the published exercises, the majority of studies (152/167) conducted gaps, need, or prioritization exercises related to physical health, whereas only a small fraction of studies focused on psychological health (12/167) (see Appendix D in the Supplementary Information).

Methods for Identifying Gaps, Needs, and Priorities

As seen in Table 1 , only about a quarter of studies involved a singular type of exercise with 7% focused on the identification of gaps only (i.e., areas with insufficient information to draw a conclusion for a given question), 6% on needs only (i.e., knowledge gaps that inhibit the decision-making of key stakeholders), and 14% priorities only (i.e., ranked gaps or needs often because of resource constraints). Studies more commonly conducted a combination of multiple types of exercises with more than half focused on the identification of both research needs and priorities, 14% on gaps and priorities, 3% gaps, needs, and priorities, and 3% gaps and needs.

Across the 167 studies, the three most frequently used methods were the convening of workshops/meetings/conferences (37%), quantitative methods (32%), and the JLA PSP approach (28%). This was followed by methods involving literature reviews (17%), qualitative methods (17%), consensus methods (13%), and reviews of source materials (15%). Other methods included the CHNRI process (7%), reviews of in-progress data (7%), consultation with (non-researcher) stakeholders (4%), applying a framework tool (4%), ENHR (1%), systematic reviews (1%), and evidence mapping (1%).

The criterion most widely applied across the 167 studies was the importance to stakeholders (72%) (see Table 2 ). Almost one-third (29%) considered the potential value and 18% feasibility as criteria. Burden of disease (9%), addressing inequities (8%), costs (6%), alignment with organization’s mission (3%), and patient centeredness (2%) were adopted as criteria to a lesser extent.

About two-thirds of the studies included researchers (66%) and clinicians (69%) as stakeholders (see Appendix E in the Supplementary Information). Patients and the public were involved in 59% of the studies. A smaller proportion included policy makers (20%), funders (13%), product makers (8%), payers (5%), and purchasers (2%) as stakeholders. Nearly half of the studies (51%) relied on stakeholder organizations to identify stakeholders (see Appendix F in the Supplementary Information). A quarter of studies (26%) used purposive sampling and some convenience sampling (11%). Few (9%) used snowball sampling to identify stakeholders. Only a minor fraction of studies, seven of the 167 (4%), reported some type of effectiveness evaluation. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31

Our scoping review revealed that approaches to identifying gaps, needs, and priorities are less likely to occur as discrete processes and more often involve a combination of exercises. Approaches encompassing multiple exercises (e.g., gaps and needs) were far more prevalent than singular standalone exercises (e.g., gaps only) (73% vs. 27%). Findings underscore the varying importance placed on gaps, needs, and priorities, which reflect key principles of the Value of Information approach (i.e., not all gaps are important, addressing gaps do not necessarily address needs nor does addressing needs necessarily address priorities). 32

Findings differ from Nyanchoka et al.’s review in which studies involving the identification of gaps only outnumbered studies involving both gaps and priorities. 7 However, Nyanchoka et al. relied on author definitions to categorize exercises, whereas our study made designations based on our review of the activities described in the article and applied definitions drawn from the literature. 3 , 4 Lack of consensus on definitions of gaps and priority setting has been noted in the literature. 33 , 34 To the authors’ knowledge, no prior scoping review has focused on methods related to the identification of “research needs.” Findings underscore the need to develop and apply more consistent taxonomy to this growing field of research.

More than 40% of studies employed methods with a structured protocol including JLA PSP, ENHR, CHRNI, World Café, and the Dialogue model. 10 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 The World Café and Dialogue models particularly value the experiential perspectives of stakeholders. The World Café centers on creating a special environment, often modeled after a café, in which rounds of multi-stakeholder, small group, conversations are facilitated and prefaced with questions designed for the specific purpose of the session. Insights and results are reported and shared back to the entire group with no expectation to achieve consensus, but rather diverse perspectives are encouraged. 36 The Dialogue model is a multi-stakeholder, participatory, priority setting method involving the following phases: exploratory (informal discussions), consultation (separate stakeholder consultations), prioritization (stakeholder ratings), and integration (dialog between stakeholders). 39 Findings may indicate a trend away from non-replicable methods to approaches that afford greater transparency and reproducibility. 41 For instance, of the 17 studies published between 2000 and 2009, none had employed CHNRI and 6% used JLA PSP compared to the 141 studies between 2010 and 2019 in which 8% applied CHNRI and 32% JLA PSP. However, notable variations in implementing CHNRI and JLA PSP have been observed. 41 , 42 , 43 Though these protocols help to ensure a more standardized process, which is essential when testing the effectiveness of methods, such evaluations are infrequent but necessary to establish the usefulness of replicable methods.

Convening workshops, meetings, or conferences was the method used by the greatest proportion of studies (37%). The operationalization of even this singular method varied widely in duration (e.g., single vs. multi-day conferences), format (e.g., expert panel presentations, breakout discussion groups), processes (e.g., use of formal/informal consensus methods), and composition of stakeholders. The operationalization of other methods (e.g., quantitative, qualitative) also exhibited great diversity.

The use of explicit criteria to determine gaps, needs, or priorities is a key component of certain structured protocols 40 , 44 and frameworks. 9 , 45 In our scoping review, the criterion applied most frequently across studies (71%) was “importance to stakeholders” followed by potential value (31%) and feasibility (18%). Stakeholder values are being incorporated into the identification of gaps, needs, and exercises across a significant proportion of studies, but how this is operationalized varies widely across studies. For instance, the CHNRI typically employs multiple criteria that are scored by technical experts and these scores are then weighted based on stakeholder ratings of their relative importance. Other studies totaled scores across multiple criteria, whereas JLA PSP asks multiple stakeholders to rank the top ten priorities. The importance of involving stakeholders, especially patients and the public, in priority setting is increasingly viewed as vital to ensuring the needs of end users are met, 46 , 47 particularly in light of evidence demonstrating mismatches between the research interests of patients and researchers and clinicians. 48 , 49 , 50 In our review, clinicians (69%) and researchers (66%) were the most widely represented stakeholder groups across studies. Patients and the public (e.g., caregivers) were included as stakeholders in 59% of the studies. Only a small fraction of studies involved exercises in which stakeholders were limited to researchers only. Patients and the public were involved as stakeholders in 12% of studies published between 2000 and 2009 compared to 60% of studies between 2010 and 2019. Findings may reflect a trend away from researchers traditionally serving as one of the sole drivers of determining which research topics should be pursued.

More than half of the studies reported relying on stakeholder organizations to identify participants. Partnering with stakeholder organizations has been noted as one of the primary methods for identifying stakeholders for priority setting exercises. 34 Purposive sampling was the next most frequently used stakeholder identification method. In contrast, convenience sampling (e.g., recommendations by study team) and snowball sampling (e.g., identified stakeholders refer other stakeholders who then refer additional stakeholders) were not as frequently employed, but were documented as common methods in a prior review conducted almost a decade ago. 14 The greater use of stakeholder organizations than convenience or snowball sampling may be partly due to the more recent proliferation of published studies using structured protocols like JLA PSP, which rely heavily on partnerships with stakeholder organizations. Though methods such as snowball sampling may introduce more bias than random sampling, 14 there are no established best practices for stakeholder identification methods. 51 Nearly a quarter of studies provided either unclear or no information on stakeholder identification methods, which has been documented as a barrier to comparing across studies and assessing the validity of research priorities. 34

Determining the effectiveness of gaps, needs, and priority exercises is challenging given that outcome evaluations are rarely conducted. Only seven studies reported conducting an evaluation. 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 Evaluations varied with respect to their focus on process- (e.g., balanced stakeholder representation, stakeholder satisfaction) versus outcome-related impact (e.g., prioritized topics funded, knowledge production, benefits to health). There is no consensus on what constitutes optimal outcomes, which has been found to vary by discipline. 52

More than 90% of studies involved exercises related to physical health in contrast to a minor portfolio of work being dedicated to psychological health, which may be an indication of the low priority placed on psychological health policy research. Understanding whether funding decisions for physical versus psychological health research are similarly or differentially governed by more systematic, formal processes may be important to the extent that this affects the effective targeting of funds.

Limitations

By limiting studies to those supported or conducted by funding organizations, we may have excluded global, national, or local priority setting exercises. In addition, our scoping review categorized approaches according to the actual exercises conducted and definitions provided in the scientific literature rather than relying on the terminology employed by studies. This resulted in instances in which the category assigned to an exercise within our scoping review could diverge from the category employed by the study authors. Lastly, this study’s findings are subject to limitations often characteristic of scoping reviews such as publication bias, language bias, lack of quality assessment, and search, inclusion, and extraction biases. 53

Conclusions

The diversity and growing establishment of formal processes and methods to identify health research gaps, needs, and priorities are characteristic of a developing field. Even with the emergence of more structured and systematic approaches, the inconsistent categorization and definition of gaps, needs, and priorities inhibit efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of varied methods and processes, such efforts are rare and sorely needed to build an evidence base to guide best practices. The immense variation occurring within structured protocols, across different combinations of disparate methods, and even within singular methods, further emphasizes the importance of using clearly defined approaches, which are essential to conducting investigations of the effectiveness of these varied approaches. The recent development of reporting guidelines for priority setting for health research may facilitate more consistent and clear documentation of processes and methods, which includes the many facets of involving stakeholders. 34 To ensure optimal targeting of funds to meet the greatest areas of need and maximize outcomes, a much more robust evidence base is needed to ascertain the effectiveness of methods used to identify research gaps, needs, and priorities.

Chalkidou K, Whicher D, Kary W, Tunis SR . Comparative Effectiveness Research Priorities: Identifying Critical Gaps in Evidence for Clinical and Health Policy Decision Making. International journal of technology assessment in health care . 2009;25(3):241-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462309990225

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yoshida S . Approaches, Tools and Methods Used for Setting Priorities in Health Research in the 21(st) Century. Journal of global health . 2016;6(1):010507-010507. doi: https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.06.010507

Robinson KA, Saldanha IJ, McKoy NA . Development of a Framework to Identify Research Gaps from Systematic Reviews. Journal of clinical epidemiology . 2011;64(12):1325-30. [Comment in: J Clin Epidemiol. 2013 May;66(5):522-3; [ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23265604 ]]. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.009

Saldanha IJ, Wilson LM, Bennett WL, Nicholson WK, Robinson KA . Development and Pilot Test of a Process to Identify Research Needs from a Systematic Review. J Clin Epidemiol . May 2013;66(5):538-45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.07.009

Viergever RF, Terry R, Matsoso M . Health research prioritization at WHO: an overview of methodology and high level analysis of WHO led health research priority setting exercises. Geneva: World Health Organization . 2010;

Google Scholar

Robinson KA, Akinyede O, Dutta T, et al. Framework for Determining Research Gaps During Systematic Review: Evaluation . 2013. AHRQ Methods for Effective Health Care .

Nyanchoka L, Tudur-Smith C, Thu VN, Iversen V, Tricco AC, Porcher R . A Scoping Review describes Methods Used to Identify, Prioritize and Display Gaps in Health Research. J Clin Epidemiol . Jan 30 2019;doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.01.005

Rudan I, Gibson JL, Ameratunga S, et al. Setting priorities in global child health research investments: guidelines for implementation of CHNRI method. Croatian medical journal . 2008;49(6):720-33.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Viergever RF, Olifson S, Ghaffar A, Terry RF . A Checklist for Health Research Priority Setting: Nine Common Themes of Good Practice. Health Res Policy Syst . Dec 15 2010;8:36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-8-36

James Lind Alliance. The James Lind Alliance Guidebook . March 2020. http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/jla-guidebook/downloads/JLA-Guidebook-V9-download-March-2020.pdf

Carey TY, A.; Beadles, C.; Wines, R . Prioritizing Future Research through Examination of Research Gaps in Systematic Reviews . 2012.

Carey T, Yon A, Beadles C, Wines R . Prioritizing future research through examination of research gaps in systematic reviews. Prepared for the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute . 2012;

Carey TS, Sanders GD, Viswanathan M, Trikalinos TA, Kato E, Chang S . Framework for Considering Study Designs for Future Research Needs. Methods Future Research Needs Paper No. 8 (Prepared by the RTI–UNC Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007- 10056-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC048-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . March 2012. Framework for Considering Study Designs for Future Research Needs . https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22624168

O’Haire C, McPheeters M, Nakamoto E, et al. Methods for Engaging Stakeholders To Identify and Prioritize Future Research Needs. Methods Future Research Needs Report No. 4. (Prepared by the Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center and the Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10057-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 11-EHC044-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Vol. Methods Future Research Needs Reports. 2011. June 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62571/

Trikalinos T, Dahabreh I, Lee J, Moorthy D . Methods Research on Future Research Needs: Defining an Optimal Format for Presenting Research Needs. Methods Future Research Needs Report No. 3. (Prepared by the Tufts Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10057-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 11-EHC027-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . June 2011. www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm .