STARI Survey

Please share your experience with SERP.

Remote Learning Resources

for STARI classes unable to meet in person.

Strategic Adolescent Reading Intervention (STARI)

Stari is a literature-focused, tier ii intervention for students in grades 6-9 who read two or more years below grade level..

By the time students reach the middle grades, they are expected to read to learn instead of to learn to read . But for the significant number of students who can’t decode or fluently read more complex text, this shift spells trouble. In addition, older students (Grades 6-9) who need targeted, intensive reading instruction are still adolescent thinkers! They do not find typical remedial materials engaging.

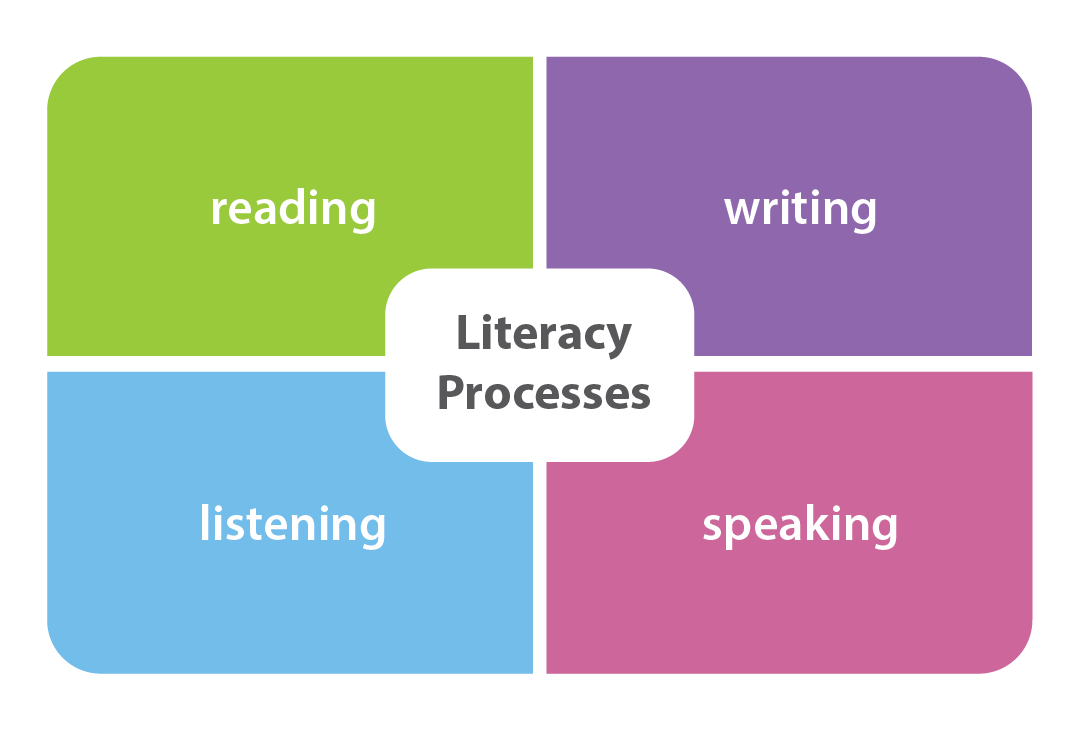

STARI is built around key research findings:

- Adolescent struggling readers need to work on both basic reading skills and the skills that underlie deep comprehension: academic language, perspective-taking, and critical reading.

- Texts need to engage students with issues in their lives and in the world.

- Peer talk about text can develop reading engagement, perspective-taking, and critical reading.

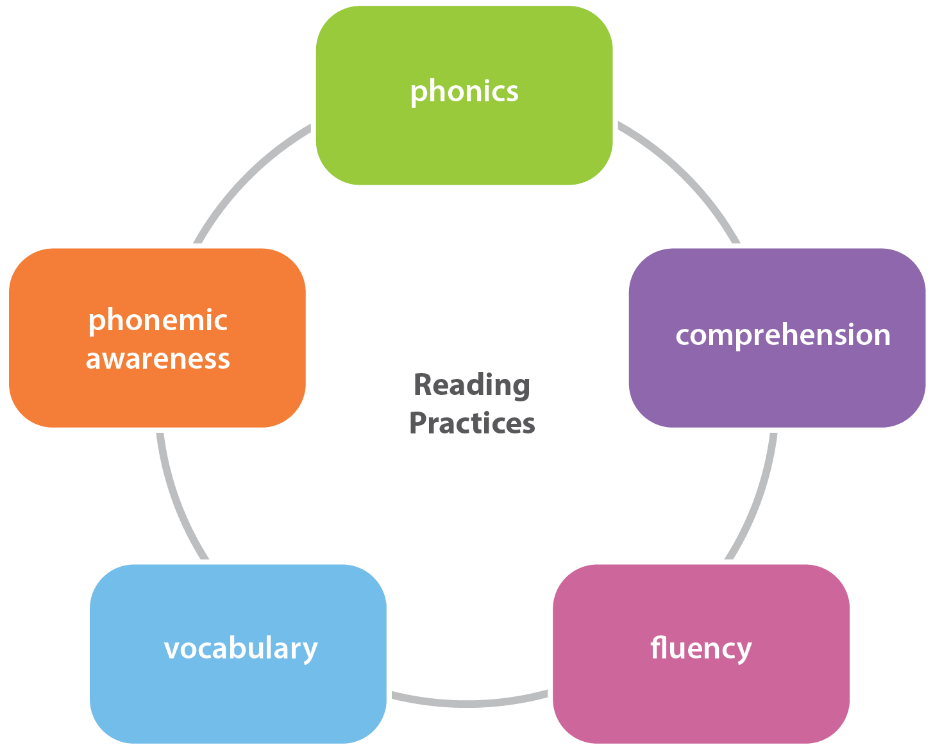

Using research-based practices and highly engaging texts, STARI addresses gaps in fluency, decoding, reading stamina, and comprehension, aiming to move struggling students to higher levels of proficiency at the end of one year. STARI actively engages students in discussions of cognitively challenging content aligned to the Common Core and other 21st century standards.

STARI is intended to be a “double dose” intervention that should not take the place of core curriculum. We recommend that schools devote either 45-60 minutes, 5 days a week, or 90 minutes on an A-day/B-day schedule, to STARI.

STARI has helped me become a better reader because talking with others and hearing the opinions of others can help me learn more about what I'm reading about.

Jasmine, 7th Grade Student

STARI has actually helped me to become a better reader because, at the beginning of the year, I thought I wasn't much of a fluent reader. I kept pausing in the middle of reading a sentence. But the more I read, the more practice it took ... I just became better.

AJ, 8th Grade Student

In some of the other intervention programs that I've taught there's really an emphasis on one component of language, so the emphasis might just be on fluency or might just be on decoding or just on comprehension.

STARI gives me the opportunity to reach across to where a lot of the gaps are. In my student group, you have English language learners, students with IEPs, and students who have just been low-performing or plateauing in their reading skills.

I think that having that holistic approach to developing reading skills, including the discussion components, really makes a big difference.

Ariadna Phillips-Santos, 8th Grade Teacher

Hear from more STARI teachers and students:

Why is a program like this necessary?

Middle school students who are several years behind in reading face enormous academic challenges. They can’t understand their subject area texts and have difficulty keeping up with class assignments. As the gap increases between their current reading skills and the literacy demands of content instruction, many fail key subjects. STARI is designed to close the comprehension gap between struggling readers and their on-level peers. STARI also aims to build reading confidence, stamina, and engagement, along with classroom discussion skills that are critical for success in secondary school and beyond.

What’s different about teaching adolescents to read?

Unlike younger students who can hone their reading skills with familiar content, adolescents are already immersed in more demanding contexts of literacy use. Middle school teachers appropriately expect that students will use literacy to acquire new information and reflect critically about what they read. By sixth grade, students are exposed to a wide range of genres beside simple narratives: historical exposition, scientific description, multiple forms of poetry and prose. A program for struggling adolescent readers needs to simultaneously address “basic” aspects of literacy: accurate decoding, fluent oral reading, literal comprehension, and the critical and disciplinary reading skills expected of older readers. Because struggling older readers have experienced years of underachievement, effective intervention also needs to address reading motivation, confidence, and engagement.

How is STARI different from other reading interventions?

Adolescent reading interventions have often shown only modest gains, especially for those students who are furthest behind in reading (Somers et al., 2010; Vaughn, Cirino, Wanzek et al., 2010). Interventions that primarily target basic skills may not improve adolescents’ performance with more challenging literacy tasks such as finding text-based evidence for a claim or integrating information across different texts.

STARI addresses reading motivation and engagement through high-interest novels and nonfiction that challenge students to think more deeply about issues in their lives. In STARI, attention to basic skills is integrated with activities involving talking, reasoning, and writing about complex issues. STARI’s classroom formats, including many opportunities for peer exchanges, tap into adolescents’ social motivations to talk about ideas they care about.

STARI is also different from many reading interventions in that discussion and debate are fundamental to the curriculum. Our belief is that when students discuss and debate the ideas in the text, they understand the text more deeply. Discussion and debate are built into most components of the curriculum, from partners discussing fluency passages to more formal debates about unit themes. Additionally, STARI is an ELA focused curriculum in which skills practice is integrated into comprehension activities. Also, the different components connect with one another in a purposeful way. For example, the fluency practice passages build background knowledge and provide information that can be used to better understand and give context to other texts in each unit.

Capti Assess with ETS® ReadBasix™

Capti Assess with ETS ReadBasix is a 45-60-minute web-based assessment appropriate for diagnosing the reading skills of students in grades 3 through 12. This assessment (formerly the RISE) was developed to help identify students who struggle with basic reading skills and provide detailed information to teachers about the nature of their struggles.

Development of STARI was led by Lowry Hemphill (Wheelock College) through a SERP collaboration with Harvard University and four Massachusetts school districts. The research reported here was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305F100026 to the Strategic Education Research Partnership as part of the Reading for Understanding Research Initiative. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education. The STARI Team

Strategic Education Research Partnership

SERP Institute

1100 Connecticut Ave NW

Washington, DC 20036

SERP Studio

2744 East 11th Street

Oakland, CA 94601

(202) 223-8555

Registered 501(c)(3). EIN: 30-0231116

Privacy Policy

Terms of Service

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.7(9); 2021 Sep

Evidence-based reading interventions for English language learners: A multilevel meta-analysis

Associated data.

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

The number of English Language Learners (ELLs) has been growing worldwide. ELLs are at risk for reading disabilities due to dual difficulties with linguistic and cultural factors. This raises the need for finding practical and efficient reading interventions for ELLs to improve their literacy development and English reading skills. The purpose of this study is to examine the evidence-based reading interventions for English Language Learners to identify the components that create the most effective and efficient interventions. This article reviewed literature published between January 2008 and March 2018 that examined the effectiveness of reading interventions for ELLs. We analyzed the effect sizes of reading intervention programs for ELLs and explored the variables that affect reading interventions using a multilevel meta-analysis. We examined moderator variables such as student-related variables (grades, exceptionality, SES), measurement-related variables (standardization, reliability), intervention-related variables (contents of interventions, intervention types), and implementation-related variables (instructor, group size). The results showed medium effect sizes for interventions targeting basic reading skills for ELLs. Medium-size group interventions and strategy-embedded interventions were more important for ELLs who were at risk for reading disabilities. These findings suggested that we should consider the reading problems of ELLs and apply the Tier 2 approach for ELLs with reading problems.

English language learners, Evidenced-based intervention, Meta-analysis, Reading.

1. Introduction

There is a growing body of literature that recognizes the importance of quality education for learners who study in a language other than their native language ( Estrella et al., 2018 ; Ludwig et al., 2019 ). As cultural, racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversification takes place globally, the number of students studying a second language different from their native language is also increasing worldwide. In the United States, nearly 5 million learners who are not native speakers of English are currently attending public schools, and this figure has increased significantly over the past decade ( NCES, 2016 ). As the number of children whose native language is not English increased, the need for educational support also increased. Furthermore, the implementation of NCLB policy emphasizes the need for quality education for all students included in all schools. Accordingly, NCLB has emerged as a critical policy for learners to study in their second language. In other words, there is an urgent need to ensure that non-native English speakers receive appropriate education due to NCLB, which has not only increased the demand for education but also led to the practice of enhanced education for learners whose English is not their native language.

ELLs (English language learners) refer to the education provided for learners whose native language is not English in English-speaking countries ( National Center for Education Statistics, 2021 ). The education provided to these ELLs is called ESL (English as a second language), ESOL (English to speakers of other languages), EFL (English as a foreign language), and so on. Each term is adopted differently depending on the policy, purpose, and status of operation of the state and/or school district. While a variety of terms have been suggested, this paper uses the term ‘ELLs’ to refer to learners who are not native speakers of English and uses the terms ‘the English education program’ and the ‘ELL program’ to refer to the English education program provided to ELLs.

To ensure quality education, students identified as ELLs can participate in supportive programs to improve their English skills. These ELL programs can be broadly divided into two methods: “pull-out” and “push-in” ( Honigsfeld, 2009 ). In the pull-out program, students are taken to a specific space other than the classroom at regular class time and are separately taught English. In the push-in program, the ELL teacher joins the mainstream ELLs’ classroom and assists them during class time. Through these educational supports, ELLs are required to achieve not only English language improvements addressed in Title III of NCLB but also language art achievements appropriate to their grade level addressed in Title I of NCLB. ELLs are expected to achieve the same level of academic achievement as students of the same grade level, as well as comparable language skills.

A considerable amount of literature has been published on the achievement and learning status of ELLs ( Ludwig, 2017 ; Soland and Sandilos, 2020 ). These studies revealed that despite the intensive, high-quality education support for ELLs, they encounter difficulties learning and academic achievement. The National Reading Achievement Test (NAEP) results show that the achievement gap between non-ELLs and ELLs is steadily expanding in the areas of both mathematics and reading ( Polat et al., 2016 ). Ultimately, ELLs are reported to have the highest risk of dropping out of school ( Sheng et al., 2011 ). These difficulties are not limited to early school age. Fry (2007) reported that the results from a national standardized test of 8th-grade students found that ELLs performed lower than white students in both reading and math. Callahan and Shifrer (2016) analyzed data from a nationally representative educational longitudinal study in 2002 and found that, despite taking into account language, socio-demographic and academic factors, ELLs still have a large gap in high school academic achievement. Additionally, research has suggested that ELLs are less likely to participate in higher education institutions compared to non-ELL counterparts ( Cook, 2015 ; Kanno and Cromley, 2015 ).

Factors found to influence the difficulties of ELLs in learning have been explored in several studies ( Dussling, 2018 ; Thompson and von Gillern, 2020 ; Yousefi and Bria, 2018 ). There are two main reasons for these difficulties. First, ELLs face many challenges in learning a new language by following the academic content required in the school year ( American Youth Policy Forum, 2009 ). Moreover, language is an area that is influenced by sociocultural factors, and learning academic contents such as English language art and math are also influenced by sociocultural elements and different cultural backgrounds, which affects the achievement of ELLs in school ( Chen et al., 2012 ; Orosco, 2010 ). Second, it is reported that the heterogeneity of ELLs makes it challenging to formulate instructional strategies and provide adequate education for them. Due to the heterogeneous traits in the linguistic and cultural aspects of the ELL group, there are limitations in specifying and guiding traits. Therefore, properly reflecting their characteristics is difficult.

The difficulties for ELLs in academic achievement raise the necessity for searching practical and efficient reading interventions for ELLs to improve English language and academic achievement, including ELLs' English language art achievement. These needs and demands led to the conduct of various studies that analyze the difficulties of ELLs. Over the past decade, these studies have provided important information on education for ELLs. The main themes of the studies are difficulties in academic achievement and interventions for ELLs, including reading ( Kirnan et al., 2018 ; Liu and Wang, 2015 ; Roth, 2015 ; Shamir et al., 2018 ; Tam and Heng, 2016 ), writing ( Daugherty, 2015 ; Hong, 2018 ; Lin, 2015 ; nullP ) or both reading and math ( Dearing et al., 2016 ; Shamir et al., 2016 ). The influences of teachers on children's guidance ( Kim, 2017 ; Daniel and Pray, 2017 ; Téllez and Manthey, 2015 ; Wasseell, Hawrylak, Scantlebuty, 2017 ) and the influences of family members ( Johnson and Johnson, 2016 ; Walker, Research on 2017 ) are also examined.

Reading is known to function as an important predictor of success not only in English language art itself but also in overall school life ( Guo et al., 2015 ). This is because reading is conducted throughout the school years, as most of the activities students perform in school are related to reading. Furthermore, reading is considered one of the major fundamental skills in modern society because it has a strong relationship with academic and vocational success beyond school-based learning ( Lesnick et al., 2010 ). In particular, for ELLs, language is one of the innate barriers; thereafter, reading is one of the most common and prominent difficulties in that it is not done in their native language ( Rawian and Mokhtar, 2017 ; Snyder et al., 2017 ). In this respect, several studies have investigated reading for ELLs. These studies explore effective interventions and strategies ( Kirnan et al., 2018 ; Mendoza, 2016 ; Meredith, 2017 ; Reid and Heck, 2017 ) and suggest reading development models or predictors for reading success ( Boyer, 2017 ; Liu and Wang, 2015 ; Rubin, 2016 ). For these individual studies to provide appropriate guidance to field practitioners and desirable suggestions for future research, aggregation of the overall related studies, not only of the individual study, and research reflections based on them are required. Specifically, meta-analysis can be an appropriate research method. Through meta-analysis, we can derive conclusions from previous studies and review them comprehensively. Furthermore, meta-analysis can ultimately contribute to policymakers and decision-makers making appropriate decisions for rational strategies and policymaking.

Although extensive research has been carried out on the difficulties of ELLs and how to support them, a sufficiently comprehensive meta-analysis of these studies has not been carried out. Some studies have focused on specific interventions, such as morphological interventions ( Goodwin and Ahn, 2013 ), peer-mediated learning ( Cole, 2014 ), and video game-based instruction ( Thompson and von Gillern ). Ludwig, Guo, and Georgiou (2019) demonstrated the effectiveness of reading interventions for ELLs. However, they divided reading-related variables into “reading accuracy”, “reading fluency”, and “reading comprehension” and examined the effectiveness of the reading-related attributes in each of the variables. Therefore, the study has limitations for exploring the various aspects of reading and their effectiveness for reading interventions.

Individual studies have their characteristics and significance. However, for individual studies to be more widely adopted in the field and to be a powerful source for future research, it is necessary to analyze these individual studies more comprehensively. Meta-analysis reviews past studies related to the topic by 'integrating' previous studies, analyzes and evaluates them through 'critical analysis', provides implications to the field, and gives rise to intellectual stimulation to future studies by ‘identifying issues’ ( Cooper et al., 2019 ). Through this, meta-analysis can be a useful tool for diagnosing the past where relevant research has been conducted, taking appropriate treatment for the present, and providing intellectual stimulation for future studies.

Therefore, the purposes of this study are to examine evidence-based reading interventions for ELLs presented in the literature to analyze their effects and to identify the actual and specific components for creating the most effective and efficient intervention for ELLs. The findings of this study make a major contribution to research on ELLs by demonstrating the implications for the field and future study.

2.1. Selection of studies

A meta-analysis of peer-reviewed articles on ELL reading interventions published between January 2008 and March 2018 was conducted. According to the general steps of a meta-analysis, data related to reading interventions for English language learners were collected as follows. First, educational and psychological publication databases, such as Google Scholar ( https://scholar.google.co.kr ), ERIC ( https://eric.ed.gov/ ), ELSEVIER ( http://www.elsevier.com ), and Springer ( https://www.springer.com/gp ) were used to find the articles to be analyzed using the search terms “ELLs,” ESL,” “Reading,” “Second language education,” “Effectiveness,” and “Intervention” separately and in combination with each other. We reviewed the results of the web-based search for articles and included all relevant articles on the preliminary list. We selected the final list of the articles to be analyzed by applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to the preliminary list of articles. Studies were included in the final list based on three primary criteria. First, each study should evaluate the effectiveness of a school-based reading intervention using an experimental or quasi-experimental group design. In this process, single case, qualitative, and/or descriptive studies for ELLs were excluded from the analysis. Second, we included all types of reading-related interventions (i.e., phonological awareness, word recognition, reading fluency, vocabulary, and reading comprehension). Third, each study needed to report data in a statistical format to calculate an effect size. Fourth, we only included studies whose subjects were in grades K-12. The preliminary list had 75 articles, but since some of these studies did not meet the inclusion criteria, we excluded them from the final list for analysis. In total, this meta-analysis included 28 studies with 234 effect sizes (see Figure 1 ).

Prisma flow diagram.

2.2. Data analysis

2.2.1. coding procedure.

To identify the relevant components of the evidence-based reading interventions for ELLs, we developed an extensive coding document. Our interest was in synthesizing the effect sizes and finding the variables that affect the effectiveness of reading interventions for ELLs. The code sheet was made based on a code sheet used in Vaughn et al. (2003) and Wanzek et al. (2010) . All studies were coded for the following: (a) study characteristics, including general information about the study, (b) student-related variables, (c) intervention-related variables, (d) implementation-related variables, (e) measurement-related variables, and (f) quantitative data for the calculation of effect sizes.

Within the study characteristics category, we coded the researchers’ names, publication year, and title from each study to identify the general information about each study. For the student-related variables, mean age, grade level(s), number of participants, number of males, number of females, sampling method, exceptionality type (reading ability level), identification criteria in case of learning disabilities, race/ethnicity, and SES were coded. We divided grade level(s) into lower elementary (K-2), upper elementary (3–5), and secondary (6–12). When students with learning disabilities participated in the study, we coded the identification criteria reported in the study. For race/ethnicity, we coded white, Hispanic, black, Asian, and others. Within intervention-related variables, we coded for the title of the intervention, the key instructional components of the intervention, the type of intervention, and the reading components of the intervention. The reading components coded were phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, reading comprehension, listening comprehension, and others. If an intervention contained multiple reading components, all reading components included in the intervention were coded. Fourth, within implementation-related variables, we coded group size, duration of the intervention (weeks), the total number of sessions, frequency of sessions per week, length of each session (minutes), personnel who provided the intervention (i.e., teacher, researchers, other), and the setting. Fifth, in measurement-related variables, we coded the title of the measurement, reliability coefficient, validity coefficient, type of measurement, type of reliability, and type of validity. We also coded quantitative data such as the pre- and posttest means, the pre- and posttest standard deviations, and the number of participants in the pre- and posttests for both the treatment and control groups. These coding variables are defined in Table 1 . The research background and sample information are in Appendix 1 .

Table 1

Coding variables.

2.2.2. Coding reliability

The included articles were coded according to the coding procedure described above. Two researchers coded each study separately and reached 91% agreement. Afterward, the researchers reviewed and discussed the differences to resolve the initial disagreements.

2.2.3. Data analysis

First, we calculated 234 effect sizes from the interventions included in the 28 studies. The average effect size was calculated using Cohen's d formula. In addition, we conducted a two-level meta-analysis through multilevel hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) using the HLM 6.0 interactive mode statistical program to analyze the computed effect sizes and find the predictors that affect the effect sizes of reading interventions. HLM is appropriate to quantitatively obtain both overall summary statistics and quantification of the variability in the effectiveness of interventions across studies as a means for accessing the generalizability of findings. Moreover, HLM easily incorporates the overall mean effect size using the unconditional model, and HLM is useful to explain variability in the effectiveness of interventions between studies in the conditional model. The aim of the current study is to provide a broad overview of interventions for ELLs. To achieve this aim, we conducted an unconditional model for overall mean effect size and conducted a conditional model to identify factors that have an impact on the strength of effect sizes. In regard to variables related to the effectiveness of interventions, we conducted a conditional model with student-related, measurement-related, intervention-related, and implementation-related variables. In the case of quantitative meta-analyses, it is assumed that observations are independent of one another ( How and de Leeuw, 2003 ). However, this assumption is usually not applied in social studies if observations are clustered within larger groups ( Bowman, 2003 ) because each effect size within a study might not be homogeneous ( Beretvas and Pastor, 2003 ). Thus, a two-level multilevel meta-analysis using a mixed-effect model was employed because multiple effect sizes are provided within a single education study. To calculate effect size (ES) estimates using Cohen's d, we use the following equation [1]:

The pooled standard deviation, SD pooled , is defined as

In HLM, the unconditional model can be implemented to identify the overall effect size across all estimates and to test for homogeneity. If an assumption of homogeneity is rejected by an insignificant chi-square coefficient in the unconditional model, this means that there are differences within and/or between studies. This assumption must go to the next step to find moderators that influence effect sizes. This step is called a level two model or a conditional model. A conditional model is conducted to investigate the extent of the influence of the included variables.

The level one model (unconditional model) was expressed as [3], and the level two model (the conditional model was expressed as [4].

In equation (3) , δ j represents the mean effect size value for study j, and e j is the within-study error term assumed to be theoretically normally distributed with a mean of 0 and a variance of V j . In the level two model equation [4], γ 0 represents the overall mean effect size for the population, and u j represents the sampling variability between studies presumed to be normally distributed with a mean of 0 and a variance τ .

Regarding publication bias, we looked at the funnel plot with the 'funnel()' command of the metafor R package ( Viechtbauer, 2010 ), and to verify this more statistically, we used the dmetar R package ( Harrer et al., 2019 ). Egger's regression test ( Egger et al., 1997 ) was conducted using the 'eggers.test()' command to review publication bias. Egger's regression analysis showed that there was a significant publication error (t = 3.977, 95% CI [0.89–2.54], p < .001). To correct this, a trim-and-fill technique ( Duval and Tweedie, 2000 ) was used. As a result, the total effect size corrected for publication bias was also calculated. The funnel plot is shown in [ Figure 2 ].

Funnel plot.

We analyzed 28 studies to identify influential variables that count for reading interventions for ELLs. Before performing the multilevel meta-analysis, the effect size of 28 studies was analyzed by traditional meta-analysis. The forest plots for the individual effect sizes of 28 studies are shown in Appendix 2. We present our findings with our research questions as an organizational framework. First, we showed an unconditional model for finding the overall mean effect size. Then, we described the variables that influenced the effect size of reading interventions for ELLs using a conditional model.

3.1. Unconditional model

An unconditional model of the meta-analysis was tested first. In the analysis, restricted maximum likelihood estimation was used. This analysis was conducted to confirm the overall mean effect size and to examine the variability among all samples. The results are shown in Table 2 .

Table 2

Results of the unconditional model analysis.

∗∗∗ p < 0.001, df: degree of freedom.

The intercept coefficient in the fixed model is the overall mean effect size from 234 effect sizes. This means that the effect of reading intervention for English language learners is medium based on Cohen's d. Cohen's d is generally interpreted as small d = 0.2, medium d = 0.5 and large d = 0.8. The variance component indicates the variability among samples. The estimate was 0.589 and remained significant (χ 2 = 1245.90, p < . 001). This statistical significance means that moderator analysis with dominant predictors in a model is required to explore the source of variability.

3.2. Conditional model

Moderator analysis using the conditional model was expected to identify factors that have an impact on the strength of effect sizes. In this study, the moderator analysis was administered by nine critical variable categories: students’ grade, exceptionality, SES, reading area, standardized test, test reliability, intervention type, instructor, and group size. Variables in each category were coded by dummy coding. Dummy coding was used to identify the difference in dependent variables between the categories of independent variables. For example, we used four dummy variables to capture the five dimensions. The parameter estimates capture the differences in effect sizes between the groups that are coded 1 and a reference group that is coded 0. From a mathematical perspective, it does not matter which categorical variable is used as the referenced group ( Frey, 2018 ). We labeled one variable in each category as a reference group to make the interpretation of the results easier. We used an asterisk mark to denote the reference group for each category; if a word has an asterisk next to it, this indicates that it is the reference group for that category.

- 1) Student-related variables

The results of the conditional meta-analysis for students' grade variables are presented in Table 3 . In Table 3 , the significant coefficients mean that mean effect sizes are significantly larger for studies in reference conditions. For student grades, upper elementary students showed significantly larger mean effect sizes than secondary students (2.720, p = 0.000), but preschool students showed significantly lower mean effect sizes than secondary students (-0.103, p = 0.019). The Q statistic was significant for students’ grades ( Q = 27.20, p < 0.001) (see Table 4 ).

Table 3

Results of the moderator analysis for student grade.

df: degree of freedom.

Table 4

Results of the moderator analysis for exceptionality.

For the student-related variables, students with low achievement showed significantly larger mean effect sizes scores than general students (0.707, p = 0.001). However, there was no significant difference between students with low achievement and general students. The Q statistic was significant for students’ exceptionality ( Q = 0.0278, p < 0.001).

Table 5 shows that low and low-middle SES was not significantly different from students with no information about SES (0.055, p = 0.666). Moreover, students with middle and upper SES did not have significantly smaller effect sizes than students with nonresponse (-0.379, p = 0.444). The Q statistic was significant for students’ SES ( Q = 68.50, p < 0.001).

Table 5

Results of the moderator analysis for SES.

- 2) Measurement-related variables

Table 6 shows the results of the moderator analysis for measurement types. The coefficient for the standardized measurement-related variable was not significant. The Q statistic was significant for the standardization of measurement tools ( Q = 5.28, p < 0.001).

Table 6

Results of the moderator analysis for standardization of measurement tools.

Table 7 shows the results of the moderator analysis for the reliability of the measurement tools. The coefficient for the measurement reliability-related variable was significant (0.409, p = 0.003), which means that the effect sizes of measurements that reported reliability (ES = 0.770) were significantly larger than the effect sizes of measurements that had information about reliability (ES = 0.361). The Q statistic was significant for the reliability of the measurement tools ( Q = 5.82, p < 0.001) (see Table 8 ).

Table 7

Results of the moderator analysis for reliability.

Table 8

Results of the moderator analysis for content of the intervention.

- 3) Intervention-related variables

The content of the intervention was divided into phonological awareness, reading fluency, vocabulary, reading comprehension, listening comprehension, and other areas. Studies measured other areas that functioned as a reference group. For the measurement area, all reading areas were significantly larger than other areas. Reading fluency (1.150, p = 0.001), reading comprehension (0.971, p = 0.000) and listening comprehension (0.834, p = 0.002) were significantly larger than those in the other areas. However, phonological awareness and vocabulary were significantly larger than other areas but lower than reading fluency, reading comprehension, and listening comprehension (0.528, p = 0.013; 0.442, p = 0.000). The Q statistic was significant for the content of the intervention ( Q = 24.005, p < 0.001).

For intervention types, strategy instruction, peer tutoring, and computer-based learning were compared to other methods, which were fixed as a reference group. Table 9 shows that strategy instruction was significantly larger than other methods in mean effect sizes (0.523, p = 0.001). However, studies that applied peer tutoring and computer-based learning showed lower than other methods, but these differences were not statistically significant (-0.113, p = 0.736; -0114, p = 0.743). The Q statistic was significant for intervention types ( Q = 73.343, p < 0.001).

Table 9

Results of the moderator analysis for intervention types.

- 4) Implementation-related variables

For instructor-related variables, other instructor-delivered instructions were assigned as a reference group. Table 10 shows that the teacher and researcher groups showed significantly larger than the other instructors. Moreover, the teacher group showed larger than the researcher group (0.909, p = 0.000). The Q statistic was significant for instructor-related variables ( Q = 14.024, p < 0.001).

Table 10

Results of the moderator analysis for instructor.

For group size, mixed groups were fixed as a reference group. Group size variables were divided into a small group (1 or more and 5 or less), a middle group (6 or more and 15 or less), and a large group or class size (16 or more). Table 11 shows that the middle group (6 or more and 15 or less) and the small group (1 or more and 5 or less) were significantly larger than the mixed group (0.881, p = 0.000; 0.451, p = 0.006). However, the difference between the large group and the mixed group was not significant (0.120, p = 0.434). The Q statistic was significant for group size variables ( Q = 17.756, p < 0.001).

Table 11

Results of the moderator analysis for group size.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to explore the effects of reading interventions for ELLs and to identify research-based characteristics of effective reading interventions for enhancing their reading ability. To achieve this goal, this study tried to determine the answers to two research questions. What is the estimated mean effect size of reading interventions for ELLs in K-12? To what extent do student-, intervention-, implementation-, and measurement-related variables have effects on improving the reading ability of ELLs in K-12? Therefore, our study was limited to recent K-12 intervention studies published between January 2008 and March 2018 that included phonological awareness, fluency, vocabulary, reading comprehension, and listening comprehension as intervention components and outcome measures. A total of 28 studies were identified and analyzed. To inquiry the two main research questions, a two-level meta-analysis was employed in this study. For the first research question, the unconditional model of HLM was conducted to investigate the mean effect size of reading interventions for ELLs. The conditional model of HLM was conducted to determine which variables have significant effects on reading interventions for ELLs. Below, we briefly summarized the results of this study and described the significant factors that seem to influence intervention effectiveness. These findings could provide a better understanding of ELLs and support implications for the development of reading interventions for ELLs.

4.1. Effectiveness of reading interventions for ELLs

The first primary finding from this meta-analysis is that ELLs can improve their reading ability when provided appropriate reading interventions. Our findings indicated that the overall mean effect size of reading interventions of ELLs yielded an effect size of 0.653, which indicates a medium level of effect. From this result, we can conclude that the appropriate reading interventions generally have impacts on reading outcomes for ELLs in K-12. This is consistent with prior syntheses reporting positive effects of reading interventions for ELLs ( Vaughn et al., 2006 ; Abraham, 2008 ).

Effect size information is important to understand the real effects of the intervention. Therefore, this finding indicated that supplementary reading interventions for ELLs will be developed and implemented. This finding also showed that states are required to develop a set of high-quality reading interventions for ELLs. Language interventions for ELLs have become one of the most important issues in the U.S. Increasing numbers of children in U.S. schools have come from homes in which English is not the primary language spoken. NCES (2016) showed that 4.9 million students, or 9.6% of public school students, were identified as ELLs, which was higher than the 3.8 million students, or 8.1%, identified in 2000 ( NCES, 2016 ). While many students of immigrant families succeed in their academic areas, too many do not. Some ELLs lag far behind native English speakers in the school because of the strong effect of language factors on the instruction or assessment. Although English is not their native language, ELLs should learn educational content in English. This leads to huge inequity in public schools. Thus, improving the English language and literacy skills of ELLs is a major concern for educational policymakers. This finding can support practitioners’ efforts and investments in developing appropriate language interventions for ELLs.

4.2. The effects of moderating variables

The second primary finding of this meta-analysis relates to four variable categories: student-, intervention-, implementation-, and measurement-related variables. Effective instruction cannot be designed by considering one factor. The quality of instruction is the product of many factors, including class size, the type of instructions, and other resources. This finding showed which factors affected the effectiveness of reading interventions. Specifically, we found that the variables that proved to have significant effects on reading outcomes of ELLs were as follows: upper elementary students, reliable measurement tools, reading and listening comprehension-related interventions, strategy instruction, and the middle group consisting of 6 or more and 15 or less. Teachers and practitioners in the field may choose to adopt these findings into their practices. ELL teachers may design their instruction as strategy-embedded instruction in middle-sized groups.

We found that grades accounted for significant variability in an intervention's effectiveness. Specifically, we found that reading interventions were substantially more effective when used with upper elementary students than secondary students. This means that the magnitude of an intervention's effectiveness changed depending on when ELLs received reading interventions. Specifically, the larger effect sizes on upper elementary students than secondary schools showed the importance of early interventions to improve ELLs' language abilities. Students who experience early reading difficulty often continue to experience failure in later grades. ELLs, or students whose primary language is other than English and are learning English as a second language, often experience particular challenges in developing reading skills in the early grades. According to Kieffer (2010) , substantial proportions of ELLs and native English speakers showed reading difficulties that emerged in the upper elementary and middle school grades even though they succeeded in learning to read in the primary grades.

Regarding students’ English proficiency and academic achievement, there was no statistically significant difference between students with low achievement and general students. Given the heterogeneity of the English language learner population, interventions that may be effective for one group of English language learners may not be effective with others ( August and Shanahan, 2006 ). This result is similar to the results achieved by Lovett et al. (2008) . Lovett et al. (2008) showed that there were no differences between ELLs and their peers who spoke English as a first language in reading intervention outcomes or growth intervention. This finding suggests that systematic and explicit reading interventions are effective for readers regardless of their primary language.

For students' socioeconomic status (SES), there was no significant difference between the low-middle group and the nonresponse group. However, we cannot find that students' SES is critical for implementing reading interventions. Low SES is known to increase the risk of reading difficulties because of the limited access to a variety of resources that support reading development and academic achievement ( Kieffer, 2010 ). Many ELLs attend schools with high percentages of students living in poverty ( Vaughn et al., 2009 ). These schools are less likely to have adequate funds and resources and to provide appropriate support for academic achievement ( Donovan and Cross, 2002 ). Snow, Burns and Griffin (1998) highlighted multiple and complex factors that contribute to poor reading outcomes in school, including a lack of qualified teachers and students who come from poverty. Although this study cannot determine the relationship between the effectiveness of reading interventions and the SES of students, more studies are needed. In addition, these results related to students’ characteristics showed that practitioners and teachers can consider for whom to implement some interventions. Researchers should provide a greater specification of the student samples because this information will be particularly critical for English language learners.

Although many of the studies measured a variety of outcomes across all areas of reading, interventions that focused on improving reading comprehension and listening comprehension obtained better effects than other reading outcomes. This result is similar to those discussed in previous findings ( Wanzek and Roberts, 2012 ; Carrier, 2003 ).

With regard to effective intervention types, the findings indicated that strategy instruction was statistically significant for improving the reading skills of ELLs. However, computer-based interventions, which are frequently used for reading instruction for ELLs in recent years, showed lower effect sizes than mixed interventions. Strategy instructions are known as one of the effective reading interventions for ELLs ( Proctor et al., 2007 ; Begeny et al., 2012 ; Olson and Land, 2007 ; Vaughn et al., 2006 ). These strategies included activating background knowledge, clarifying vocabulary meaning, and expressing visuals and gestures for understanding after reading. Some studies have shown that computer-based interventions are effective for ELLs ( White and Gillard, 2011 ; Macaruso and Rodman, 2011 ), but this study does not. Therefore, there is little agreement in the research literature on how to effectively teach reading to ELLs ( Gersten and Baker, 2000 ). Continued research efforts must specify how best to provide intervention for ELLs.

With respect to the implementation of the intervention, teachers and researchers as instructors would produce stronger effects than other instructors. In this study, multiple studies showed that various instructors taught ELLs, including teachers, graduate students, and researchers. The professional development of instructors is more important than that of those who taught ELLs. This finding is consistent with Richards-Tutor et al. (2016) . They also did not find differences between researcher-delivered interventions and school personnel-delivered interventions. Continuing professional development should build on the preservice education of teachers, strengthen teaching skills, increase teacher knowledge of the reading process, and facilitate the integration of newer research on reading into the teaching practices of classroom teachers ( Snow et al., 1998 ). Overall, professional development is the key factor in strengthening the reading skills of ELLs.

This study showed that medium-sized groups of 6 or more and 15 or less had larger effect sizes than the mixed groups. In addition, the medium-sized group showed a larger effect size than the small group of 5 or less. This finding showed that a multi-tiered reading system should be needed in the general classroom. This finding is linked to the fact that the reaction to intervention (RTI) approach is more effective for ELLs. Linan-Thompson et al. (2007) pointed out that RTI offers a promising alternative for reducing the disproportionate representation of culturally and linguistically diverse students in special education by identifying students at risk early and providing preventive instruction to accelerate progress. Regarding interventions for ELLs who are struggling with or at risk for reading difficulties, Ross and Begeny (2011) compared the effectiveness between small group interventions and implementing the intervention in a 1/1 context for ELLs. They showed that nearly all students benefitted from the 1/1 intervention, and some students benefitted from the small group intervention. This finding is commensurate with a previous study investigating the comparative differences between group sizes and suggests research-based support for the introduction of the RTI approach.

However, most implementation-related variables, including duration of intervention, the total number of sessions, frequency per week, length of each session, settings, and instructor, did not have any significant effect on the reading ability of ELLs. That is, ELLs are able to achieve their reading improvement regardless of the duration of intervention, where they received the reading intervention, and who taught them. This finding is similar to those discussed by Snyder et al. (2017) . They also synthesized the related interventions for ELLs and showed that the length of intervention did not seem to be directly associated with overall effect sizes for reading outcomes. This finding is also the same as recent research on intervention duration with native English speakers ( Wanzek et al., 2013 ). Wanzek and colleagues examined the relationship between student outcomes and hours of intervention in their meta-analysis. The findings showed no significant differences in student outcomes based on the number of intervention hours. Elbaum et al. (2000) stated that the intensity of the interventions is most important for effectiveness. Our results somewhat support these researchers’ opinions, but we cannot be certain that a brief intervention would have the same overall effect on reading outcomes as a year-long intervention. Thus, we should consider the intervention intensity, such as student attendance at the sessions, with the duration of the intervention.

4.3. Implications for practice and for research

The most effective and efficient education refers to education that is made up in the right ways, that includes proper content, and that is delivered on time so that the students can benefit the most. To implement this, research to identify a particular framework based on the synthesis of research results through meta-analysis, such as this study, must be conducted. Furthermore, the implications based on the results must be deeply considered. In this respect, important implications for the practice and research of practitioners, researchers, and policymakers on enhancing reading competence for ELLs of this study are as follows.

First, reading interventions for ELLs are expected to be the most efficient when conducted on a medium-sized group of 6–15 students. This indicates that implementing reading interventions for ELLs requires a specially designed group-scale configuration rather than simply a class-wide or one-to-one configuration. Second, the implementation of reading interventions for ELLs is most effective when conducted for older elementary school students. This is in contrast to Morgan and Sideridis (2006) , who demonstrated the characteristics of students with learning disabilities using multilevel meta-analysis and showed that age groups were irrelevant in the effect size of reading interventions for students with learning disabilities. Therefore, it can be seen that the ELLs group, unlike the learning disability group, the students of which have reading difficulty due to their disabilities, is in the normal development process but has reading difficulty due to linguistic differences. Accordingly, it can be seen that the senior year of elementary school, in which a student has been exposed to the academic environment for a sufficiently long time and language is sufficiently developed, is the appropriate time for learning English for ELLs. Third, effective reading interventions for ELLs should be performed with a strategy-embedded instruction program. This is based on the fact that strategic instructions are effective for vocabulary or concepts in unfamiliar languages ( Carlo et al., 2005 ; Chaaya and Ghosn, 2010 ).

The above implications require the implementation of Tier 2 interventions for reading interventions for ELLs in practice. In Tier 2 interventions, students can participate in more intensive learning through specially designed interventions based on their personal needs ( Ortiz et al., 2011 ). In other words, in policymaking and administrative decision-making, intensive education programs for ELLs who have been exposed to the academic environment for a certain period but still have reading difficulties, including having achievements that fall short of the expected level, are needed.

Considering further applications, these findings could guide practitioners and policymakers to develop effective evidence-based reading programs or policies. The significant variables in this study can be considered to develop new programs for ELLs.

Declarations

Author contribution statement.

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020S1A3A2A02103411).

Data availability statement

Declaration of interests statement.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

- Abraham L.B. Computer-mediated glosses in second language reading comprehension and vocabulary learning: a meta-analysis. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2008; 21 (3):199–226. [ Google Scholar ]

- August D., Shanahan T. In: Developing literacy in second-language learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language Minority Children and Youth. August D., Shanahan T., editors. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. Synthesis: instruction and professional development; pp. 351–364. [ Google Scholar ]

- Begeny J.C., Ross S.G., Greene D.J., Mitchell R.C., Whitehouse M.H. Effects of the Helping Early Literacy with Practice Strategies (HELPS) reading fluency program with Latino English language learners: a preliminary evaluation. J. Behav. Educ. 2012; 21 (2):134–149. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beretvas S.N., Pastor D.A. Using mixed-effects models in reliability generalization studies. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2003; 63 (1):75–95. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bowman N.A. Effect sizes and statistical methods for meta-analysis in higher education. Res. High. Educ. 2003; 53 :375–382. [ Google Scholar ]

- Boyer K. The Relationship Between Vocabulary and Reading Comprehension in Third Grade Students Who Are English Language Learners and Reading Below Grade Level. 2017. (Masters Thesis) [ Google Scholar ]

- Carlo M.S., August D., Snow C.E. Sustained vocabulary-learning strategy instruction for English-language learners. Teach. Learn. Vocabul.: Bring. Res. Pract. 2005:137–153. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carrier K.A. Improving high school English language learners' second language listening through strategy instruction. Biling. Res. J. 2003; 27 (3):383–408. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chaaya D., Ghosn I.K. Supporting young second language learners reading through guided reading and strategy instruction in a second grade classroom in Lebanon. Educ. Res. Rev. 2010; 5 (6):329–337. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen X., Ramirez G., Luo Y.C., Geva E., Ku Y.M. Comparing vocabulary development in Spanish-and Chinese-speaking ELLs: the effects of metalinguistic and sociocultural factors. Read. Writ. 2012; 25 (8):1991–2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cole M.W. Speaking to read: meta-analysis of peer-mediated learning for English language learners. J. Lit. Res. 2014; 46 (3):358–382. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cooper H., Hedges L.V., Valentine J.C., editors. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. Russell Sage Foundation; 2019. [ Google Scholar ]

- Daniel S.M., Pray L. Learning to teach English language learners: a study of elementary school teachers’ sense-making in an ELL endorsement program. Tesol Q. 2017; 51 (4):787–819. [ Google Scholar ]

- Daugherty J.L. 2015. Assessment of ELL Written Language Progress in Designated ESL Noncredit Courses at the Community College Level. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dearing E., Walsh M.E., Sibley E., Lee-St. John T., Foley C., Raczek A.E. Can community and school-based supports improve the achievement of first-generation immigrant children attending high-poverty schools? Child Dev. 2016; 87 (3):883–897. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donovan M.S., Cross C.T. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2002. Minority Students in Special and Gifted Education. 2101 Constitution Ave., NW, Lockbox 285, 20055. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dussling T.M. Examining the effectiveness of a supplemental reading intervention on the early literacy skills of English language learners. Liter. Res. Instr. 2018; 57 (3):276–284. [ Google Scholar ]

- Duval S., Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000; 56 (2):455–463. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Egger M., Smith G.D., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997; 315 (7109):629–634. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elbaum B., Vaughn S., Tejero Hughes M., Watson Moody S. How effective are one-to-one tutoring programs in reading for elementary students at risk for reading failure? A meta-analysis of the intervention research. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020; 92 (4):605–619. [ Google Scholar ]

- Estrella G., Au J., Jaeggi S.M., Collins P. Is inquiry science instruction effective for English language learners? A meta-analytic review. AERA Open. 2018; 4 (2) 2332858418767402. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frey B.B. Sage Publications; 2018. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Educational Research, Measurement, and Evaluation. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gersten R., Baker S. What we know about effective instructional practices for English-language learners. Except. Child. 2000; 66 (4):454–470. [ Google Scholar ]

- Guo Y., Sun S., Breit-Smith A., Morrison F.J., Connor C.M. Behavioral engagement and reading achievement in elementary-school-age children: a longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015; 107 (2):332–347. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodwin A.P., Ahn S. A meta-analysis of morphological interventions in English: effects on literacy outcomes for school-age children. Sci. Stud. Read. 2013; 17 (4):257–285. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harrer M., Cuijpers P., Furukawa T.A., Ebert D.D. Doing meta-analysis with R: A hands-On guide. from. 2019. https://bookdown.org/MathiasHarrer/Doing_Meta_Analysis_in_R/ [ Google Scholar ]

- Hong H. Exploring the role of intertextuality in promoting young ELL children’s poetry writing and learning: a discourse analytic approach. Classr. Discourse. 2018; 9 (2):166–182. [ Google Scholar ]

- Honigsfeld A. ELL programs: not ‘one size fits all’ Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 2009; 45 (4):166–171. [ Google Scholar ]

- How J.J., de Leeuw E.D. In: Multilevel Modeling: Methodological Advances, Issues, and Applications. Reise S.P., Duan N., editors. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. Multilevle model for meta-analysis; pp. 90–111. [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson E.J., Johnson A.B. Enhancing academic investment through home-school connections and building on ELL students' scholastic funds of knowledge. J. Lang. Literacy Educ. 2016; 12 (1):104–121. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kieffer M.J. Socioeconomic status, English proficiency, and late-emerging reading difficulties. Educ. Res. 2010; 39 (6):484–486. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim K. Global Conference on Education and Research (GLOCER 2017) 2017. May). Influence of ELL instructor’s culturally responsive attitude on newly arrived adolescent ELL students’ academic achievement; pp. 239–242. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kirnan J., Ventresco N.E., Gardner T. The impact of a therapy dog program on children’s reading: follow-up and extension to ELL students. Early Child. Educ. J. 2018; 46 (1):103–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lesnick J., Goerge R., Smithgall C., Gwynne J. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago; Chicago, IL: 2010. Reading on Grade Level in Third Grade: How Is it Related to High School Performance and College Enrollment. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin S.M. A study of ELL students' writing difficulties: a call for culturally, linguistically, and psychologically responsive teaching. Coll. Student J. 2015; 49 (2):237–250. [ Google Scholar ]

- Linan-Thompson S., Cirino P.T., Vaughn S. Determining English language learners' response to intervention: questions and some answers. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2007; 30 (3):185–195. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu S., Wang J. Reading cooperatively or independently? Study on ELL student reading development. Read. Matrix: Int. Online J. 2015; 15 (1):102–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lovett M.W., De Palma M., Frijters J., Steinbach K., Temple M., Benson N., Lacerenza L. Interventions for reading difficulties: a comparison of response to intervention by ELL and EFL struggling readers. J. Learn. Disabil. 2008; 41 (4):333–352. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ludwig C. University of Alberta; Canada: 2017. The Effects of Reading Interventions on the Word-Reading Performance of English Language Learners: A Meta-Analysis (Unpublished Master’s Thesis) [ Google Scholar ]

- Ludwig C., Guo K., Georgiou G.K. Are reading interventions for English language learners effective? A meta-analysis. J. Learn. Disabil. 2019; 52 (3):220–231. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Macaruso P., Rodman A. Benefits of computer-assisted instruction to support reading acquisition in English language learners. Biling. Res. J. 2011; 34 (3):301–315. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mendoza S. Reading strategies to support home-to-school connections used by teachers of English language learners. J. English Lang. Teach. 2016; 6 (4):33–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Meredith D.C. Trevecca Nazarene University; 2017. Relationships Among Utilization of an Online Differentiated Reading Program, ELL Student Literacy Outcomes, and Teacher Attitudes. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morgan P.L., Sideridis G.D. Contrasting the effectiveness of fluency interventions for students with or at risk for learning disabilities: a multilevel random coefficient modeling meta-analysis. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2006; 21 (4):191–210. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) 2021. English Language Learners in Public Schools. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf Retrieved from. [ Google Scholar ]

- Olson C.B., Land R. A cognitive strategies approach to reading and writing instruction for English language learners in secondary school. Res. Teach. Engl. 2007:269–303. [ Google Scholar ]

- Orosco M.J. A sociocultural examination of response to intervention with Latino English language learners. Theory Into Pract. 2010; 49 (4):265–272. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ortiz A.A., Robertson P.M., Wilkinson C.Y., Liu Y.J., McGhee B.D., Kushner M.I. The role of bilingual education teachers in preventing inappropriate referrals of ELLs to special education: implications for response to intervention. Biling. Res. J. 2011; 34 (3):316–333. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pang Y. Empowering ELL students to improve writing skills through inquiry-based learning. N. Engl. Read. Assoc. J. 2016; 51 (2):75–79. [ Google Scholar ]

- Polat N., Zarecky-Hodge A., Schreiber J.B. Academic growth trajectories of ELLs in NAEP data: The case of fourth-and eighth-grade ELLs and non-ELLs on mathematics and reading tests. J. Educ. Res. 2016; 109 (5):541–553. [ Google Scholar ]

- Proctor C.P., Dalton B., Grisham D.L. Scaffolding English language learners and struggling readers in a universal literacy environment with embedded strategy instruction and vocabulary support. J. Literacy Res. 2007; 39 (1):71–93. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rawian R.M., Mokhtar A.A. ESL reading accuracy: the inside story. Soc. Sci. 2017; 12 (7):1242–1249. [ Google Scholar ]

- Reid T., Heck R.H. Exploring reading achievement differences between elementary school students receiving and not receiving English language services. AERA Online Paper Repositor. 2017 [ Google Scholar ]

- Richards-Tutor C., Baker D.L., Gersten R., Baker S.K., Smith J.M. The effectiveness of reading interventions for English learners: a research synthesis. Except. Child. 2016; 82 (2):144–169. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ross S.G., Begeny J.C. Improving Latino, English language learners' reading fluency: the effects of small-group and one-on-one intervention. Psychol. Sch. 2011; 48 (6):604–618. [ Google Scholar ]

- Roth A. Northwest Missouri State University; United States: 2015. Does Buddy Reading Improve Students' Oral Reading Fluency? Unpublished Doctoral dissertation. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rubin D.I. Growth in oral reading fluency of Spanish ELL students with learning disabilities. Interv. Sch. Clin. 2016; 52 (1):34–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shamir H., Feehan K., Yoder E. EdMedia+ Innovate Learning. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE); 2016. June). Using technology to improve reading and math scores for the digital native; pp. 1425–1434. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shamir H., Feehan K., Yoder E., Pocklington D. MANAGEMENT AND MARKETING (MAC-EMM 2018); 2018. Can CAI Improve Reading Achievement in Young ELL Students? ECONOMICS; p. 229. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sheng Z., Sheng Y., Anderson C.J. Dropping out of school among ELL students: implications to schools and teacher education. Clear. House. 2011; 84 (3):98–103. [ Google Scholar ]

- Snow C.E., Burns S.M., Griffin P. Predictors of success and failure in reading. Prevent. Read. Difficul. Young Child. 1998:100–134. [ Google Scholar ]

- Snyder E., Witmer S.E., Schmitt H. English language learners and reading instruction: a review of the literature. Prev. Sch. Fail.: Alter. Educ. Child. Youth. 2017; 61 (2):136–145. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soland J., Sandilos L.E. English language learners, self-efficacy, and the achievement gap: understanding the relationship between academic and social-emotional growth. J. Educ. Stud. Placed A. T. Risk. 2020:1–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tam K.Y., Heng M.A. Using explicit fluency training to improve the reading comprehension of second grade Chinese immigrant students. Mod. J. Lang. Teach Methods. 2016; 6 (5):17. [ Google Scholar ]

- Téllez K., Manthey G. Teachers’ perceptions of effective school-wide programs and strategies for English language learners. Learn. Environ. Res. 2015; 18 (1):111–127. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson C.G., von Gillern S. Video-game based instruction for vocabulary acquisition with English language learners: a Bayesian meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020; 30 :100332. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaughn S., Kim A., Sloan C.V.M., Hughes M.T., Elbaum B., Sridhar D. Social skills interventions for young children with disabilities: a synthesis of group design studies. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2003; 24 :2–15. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaughn S., Martinez L.R., Linan-Thompson S., Reutebuch C.K., Carlson C.D., Francis D.J. Enhancing social studies vocabulary and comprehension for seventh-grade English language learners: findings from two experimental studies. J. Res. Educ. Effect. 2009; 2 (4):297–324. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vaughn S., Mathes P., Linan-Thompson S., Cirino P., Carlson C., Pollard-Durodola S., Francis D. Effectiveness of an English intervention for first-grade English language learners at risk for reading problems. Elem. Sch. J. 2006; 107 (2):153–180. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010; 36 (3):1–48. [ Google Scholar ]

- Walker S.A. Chicago State University; 2017. Exploration of ELL Parent Involvement Measured by Epstein's Overlapping Spheres of Influence. Doctoral dissertation. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wanzek J., Roberts G. Reading interventions with varying instructional emphases for fourth graders with reading difficulties. Learn. Disabil. Q. 2012; 35 (2):90–101. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wanzek J., Wexler J., Vaughn S., Ciullo S. Reading interventions for struggling readers in the upper elementary grades: a synthesis of 20 years of research. Read. Writ. 2010; 23 (8):889–912. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wanzek J., Vaughn S., Scammacca N.K., Metz K., Murray C.S., Roberts G., Danielson L. Extensive reading interventions for students with reading difficulties after grade 3. Rev. Educ. Res. 2013; 83 (2):163–195. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wassell B.A., Hawrylak M.F., Scantlebury K. Barriers, resources, frustrations, and empathy: teachers’ expectations for family involvement for Latino/a ELL students in urban STEM classrooms. Urban Educ. 2017; 52 (10):1233–1254. [ Google Scholar ]

- White E.L., Gillard S. Technology-based literacy instruction for English language learners. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 2011; 8 (6):1–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yousefi M.H., Biria R. The effectiveness of L2 vocabulary instruction: a meta-analysis. Asian-Pacific J. Second Fore. Lang. Educ. 2018; 3 (1):1–19. [ Google Scholar ]

References for studies included in the meta-analysis

- Amendum S.J., Bratsch-Hines M., Vernon-Feagans L. Investigating the efficacy of a web-based early reading and professional development intervention for young English learners. Read. Res. Q. 2018; 53 (2):155–174. [ Google Scholar ]

- American Youth Policy Forum. (2009). Issue brief Moving English language learners to college and career readiness. Retrieved November 22,2009, from: www.aypf.org/documents/ELLIssueBrief

- Callahan R.M., Shifrer D. Equitable access for secondary English learner students: course taking as evidence of EL program effectiveness. Educ. Admin. Q. 2016; 52 (3):463–496. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cho H., Brutt-Griffler J. Integrated reading and writing: a case of Korean English language learners. Read. Foreign Lang. 2015; 27 (2):242. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chow B.W.Y., McBride-Chang C., Cheung H. Parent–child reading in English as a second language: effects on language and literacy development of Chinese kindergarteners. J. Res. Read. 2010; 33 (3):284–301. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cruz de Quiros A.M., Lara-Alecio R., Tong F., Irby B.J. The effect of a structured story reading intervention, story retelling and higher order thinking for English language and literacy acquisition. J. Res. Read. 2012; 35 (1):87–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cook A.L. Exploring the role of school counselors. J. Sch. Couns. 2015; 13 (9):1–33. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dabarera C., Renandya W.A., Zhang L.J. The impact of metacognitive scaffolding and monitoring on reading comprehension. System. 2014; 42 :462–473. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dockrell J.E., Stuart M., King D. Supporting early oral language skills for English language learners in inner city preschool provision. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010; 80 (4):497–515. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Filippini A.L., Gerber M.M., Leafstedt J.M. A vocabulary-added reading intervention for English learners at-risk of reading difficulties. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2012; 27 (3):14–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fry R. How far behind in math and reading are English language learners? Pew Hispanic Center; Washington, DC: 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jamaludin K.A., Alias N., Mohd Khir R.J., DeWitt D., Kenayathula H.B. The effectiveness of synthetic phonics in the development of early reading skills among struggling young ESL readers. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 2016; 27 (3):455–470. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kanno Y., Cromley J. English language learners’ pathways to four-year colleges. Teachers College Record. 2015; 117 (12):1–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mancilla-Martinez J. Word meanings matter: cultivating English vocabulary knowledge in fifth-grade Spanish-speaking language minority learners. Tesol Q. 2010; 44 (4):669–699. [ Google Scholar ]

- McMaster K.L., Kung S.H., Han I., Cao M. Peer-assisted learning strategies: a “Tier 1” approach to promoting English learners' response to intervention. Except. Child. 2008; 74 (2):194–214. [ Google Scholar ]

- Olivier A.M., Anthonissen C., Southwood F. Literacy development of English language learners: the outcomes of an intervention programme in grade R. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2010; 57 (1):58–65. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pollard-Durodola S.D., Gonzalez J.E., Saenz L., Resendez N., Kwok O., Zhu L., Davis H. The effects of content-enriched shared book reading versus vocabulary-only discussions on the vocabulary outcomes of preschool dual language learners. Early Educ. Dev. 2018; 29 (2):245–265. [ Google Scholar ]

- Proctor C.P., Dalton B., Uccelli P., Biancarosa G., Mo E., Snow C., Neugebauer S. Improving comprehension online: effects of deep vocabulary instruction with bilingual and monolingual fifth graders. Read. Writ. 2011; 24 (5):517–544. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodríguez C.D., Filler J., Higgins K. Using primary language support via computer to improve reading comprehension skills of first-grade English language learners. Comput. Sch. 2012; 29 (3):253–267. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silverman R., Hines S. The effects of multimedia-enhanced instruction on the vocabulary of English-language learners and non-English-language learners in pre-kindergarten through second grade. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009; 101 (2):305–314. [ Google Scholar ]

- Slavin R.E., Madden N., Calderón M., Chamberlain A., Hennessy M. Reading and language outcomes of a multiyear randomized evaluation of transitional bilingual education. Educ. Eval. Pol. Anal. 2011; 33 (1):47–58. [ Google Scholar ]

- Solari E.J., Gerber M.M. Early comprehension instruction for Spanish-speaking English language learners: teaching text-level reading skills while maintaining effects on word-level skills. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2008; 23 (4):155–168. [ Google Scholar ]

- Spycher P. Learning academic language through science in two linguistically diverse kindergarten classes. Elem. Sch. J. 2009; 109 (4):359–379. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tong F., Irby B.J., Lara-Alecio R., Koch J. Integrating literacy and science for English language learners: from learning-to-read to reading-to-learn. J. Educ. Res. 2014; 107 (5):410–426. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tong F., Irby B.J., Lara-Alecio R., Mathes P.G. English and Spanish acquisition by Hispanic second graders in developmental bilingual programs: a 3-year longitudinal randomized study. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2008; 30 (4):500–529. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tong F., Irby B.J., Lara-Alecio R., Yoon M., Mathes P.G. Hispanic English learners' responses to longitudinal English instructional intervention and the effect of gender: a multilevel analysis. Elem. Sch. J. 2010; 110 (4):542–566. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tong F., Lara-Alecio R., Irby B.J., Mathes P.G. The effects of an instructional intervention on dual language development among first-grade Hispanic English-learning boys and girls: a two-year longitudinal study. J. Educ. Res. 2011; 104 (2):87–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- Townsend D., Collins P. Academic vocabulary and middle school English learners: an intervention study. Read. Writ. 2009; 22 (9):993–1019. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vadasy P.F., Sanders E.A. Efficacy of supplemental phonics-based instruction for low-skilled kindergarteners in the context of language minority status and classroom phonics instruction. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010; 102 (4):786–803. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vadasy P.F., Sanders E.A. Efficacy of supplemental phonics-based instruction for low-skilled first graders: how language minority status and pretest characteristics moderate treatment response. Sci. Stud. Read. 2011; 15 (6):471–497. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Staden A. Reading in a second language: considering the 'simple view of reading' as a foundation to support ESL readers in Lesotho, Southern Africa. Per Linguam: J. Lang. Learn. 2016; 32 (1):21–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- Yeung S.S., Siegel L.S., Chan C.K. Effects of a phonological awareness program on English reading and spelling among Hong Kong Chinese ESL children. Read. Writ. 2013; 26 (5):681–704. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Intervention

- English Learner

- Special Education

- Extended Learning

- Summer Learning

- How it Works

- Reading Assessment

- Personalized Learning

- Teacher-Directed Instruction

- Professional Development and Support

- Content Library

User Experience

- Reading Support Program

- Administrators

- Content Partners

- Research & Results

- Success Stories

- Evaluations

Featured Resource

4 Key Ingredients of a Successful Reading Intervention Implementation

Once you’ve chosen a reading intervention that suits your needs,…

- All Educators ,

Featured Video

Researched based reading interventions for promising readers.

Tier II and III students and other struggling readers often lack the essential comprehension skills and vocabulary to meet grade-level literacy objectives. Reading Plus supports RtI and MTSS models by combining personalized practice with adaptive instruction, helping students to improve silent reading fluency.

The continuous collection of data on student performance customizes the program’s instructional scaffolds, and assists students in developing greater independence.

Reading Plus offers online instruction as well as printable materials for direct instruction and differentiation at the class, small group, and individual levels.

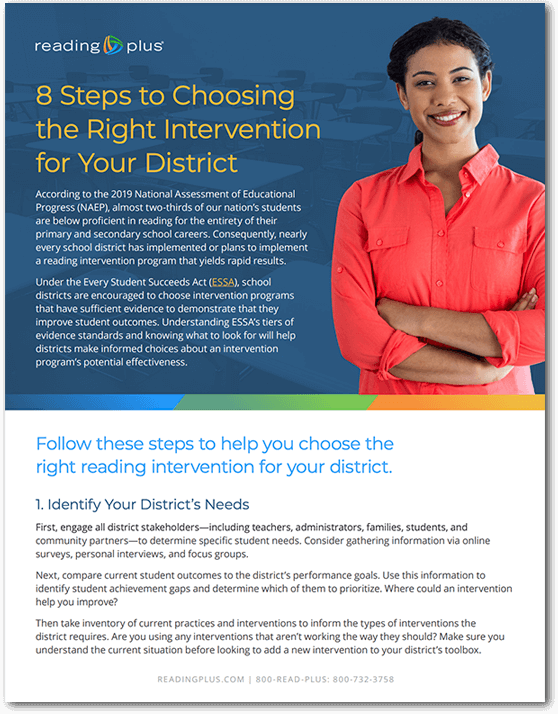

5 Steps to Choosing the Right Intervention for Your District

Under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), school districts are encouraged to choose intervention programs that have sufficient evidence to demonstrate that they improve student outcomes.

Understanding ESSA’s tiers of evidence standards and knowing what to look for will help districts make informed choices about an intervention program’s potential effectiveness. Download our guide to learn more.

Download Guide

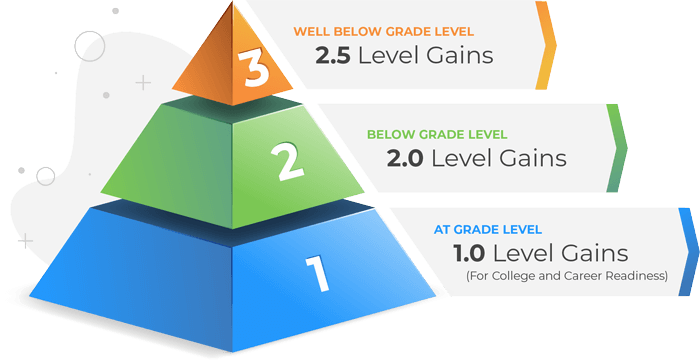

Rapid Results for Tier 2 and 3 Struggling Readers

Reading Plus is designed to rapidly accelerate reading proficiency growth in struggling readers to close the achievement gap. In just 60 hours of Reading Plus use, students make significant gains toward grade-level reading proficiency.

Get More Information

Schedule a Free Demo

Florida State University

FSU | Florida Center for Reading Research

Florida Center for Reading Research

- The Florida K-12 Reading Endorsement

- Competency 4 - Foundations & Applications of Differentiated Instruction

Session 6: Research-based Interventions to Advance Comprehension

Research-based interventions to promote fluency and oral language.