Abstract Generator

Get your abstract written – skip the headache., writefull's abstract generator gives you an abstract based on your paper's content., paste in the body of your text and click 'generate abstract' . here's an example from hindawi., frequently asked questions about the abstract generator.

Is your question not here? Contact us at [email protected]

What are the Abstract Generator's key features?

Research Paper Abstract Generator

Writing the abstract for your research paper, dissertation, or book chapter is usually one of the final steps before you submit your work. It’s also the activity that many students and researchers find most difficult. A strong abstract must be clear, succinct and informative, but how do you decide what to include?

Structuring your abstract

Many journals require the abstract to be structured according to

whereas the abstract for your dissertation or chapter may just be a short narrative paragraph. Either way, the abstract should contain key information from the study and be easy to read. Creating an abstract is as much an art as a science.

Happily, Scholarcy can help by identifying exactly the right information to include in your abstract.

Abstract in numbers

4 steps to generate an abstract with scholarcy.

Upload your article

Simply upload your article to Scholarcy Library to generate a summary flashcard that outlines your research and contains the information needed to create your abstract.

View Scholarcy Highlights

The Scholarcy Highlights tab contains 5-7 bullet points comprising the background to the study, the key findings, and the conclusion.

View Scholarcy Summary

If your paper contains standard IMRaD sections, then the Scholarcy Summary will automatically be structured to follow these headings and will include any study objectives that you have written.

And the Study subjects and participants tab extracts key information about study participants, interventions, and quantitative results. Perfect for your abstract!

Try Smart Synopsis

Alternatively, for your dissertation or book chapter, you can use our Smart Synopses tool to create a more naturally flowing, narrative abstract.

What People Are Saying

“Quick processing time, successfully summarized important points.”

“It’s really good for case study analysis, thank you for this too.”

“I love this website so much it has made my research a lot easier thanks!”

“The instant feedback I get from this tool is amazing.”

“Thank you for making my life easier.”

Privacy Overview

Load Sample

Title is Here

Your abstract is here

- Abstract Generator

Abstract generator lets you create an abstract for the research paper by using advanced AI technology.

This online abstract maker generates a title and precise overview of the given content with one click.

It generates an accurate article abstract by combining the most relevant and important phrases from the content of the article.

How to write an abstract for a research paper?

Here’s how you can generate the abstract of your content in the below easy steps:

- Type or copy-paste your text into the given input field.

- Alternatively, upload a file from the local storage of your system.

- Verify the reCAPTCHA.

- Click on the Generate button.

- Copy the results and paste them wherever you want in real-time.

Features of Our Online Abstract Generator

Free for all.

Our abstract generator APA is completely free for everyone. You don’t have to purchase any subscription to abstract research papers and articles.

Files Uploading

To get rid of typing or pasting long text into the input box, you can use this feature.

This will allow you to upload TXT, DOC, and PDF files from the local storage without any hurdles.

Create Abstract and Title

This abstract creator online makes it easy for you to generate a title and precis overview of the given text with one click.

It takes the important key phrases from the content and combines them to create an accurate abstract with advanced AI.

Click to Copy

You can use this feature of our online abstract maker to copy the result text in real-time and paste it wherever you want without any hassle.

Download File

This feature lets you download the abstracted text in DOC format for future use just within a single click.

No Signup/Registration

This free text abstraction tool requires no signup or registration process to use it. Simply go the Editpad.org , search for the Abstract Generator, open it, and enter your text to create an abstract of any text within seconds.

Other Tools

- Plagiarism Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Reverse Text - Backwards Text Generator

- Small Text Generator - Small Caps / Tiny Text

- Upside Down Text Generator

- Words to Pages

- Case Converter

- Online rich-text editor

- Grammar Checker

- Article Rewriter

- Invisible Character

- Readability Checker

- Diff Checker

- Text Similarity Checker

- Extract Text From Image

- Text Summarizer

- Emoji Translator

- Weird Text Generator

- Stylish Text Generator

- Glitch Text Generator

- Cursive Font Generator

- Gothic Text Generator

- Discord Font Generator

- Aesthetic Text Generator

- Cool Text Generator

- Wingdings Translator

- Old English Translator

- Online HTML Editor

- Cursed Text Generator

- Bubble Text Generator

- Strikethrough Text Generator

- Zalgo Text Generator

- Big Text Generator - Generate Large Text

- Old Norse Translator

- Fancy Font Generator

- Cool Font Generator

- Fortnite Font Generator

- Fancy Text Generator

- Word Counter

- Character Counter

- Punctuation checker

- Text Repeater

- Vaporwave Text Generator

- Citation Generator

- Title Generator

- Text To Handwriting

- Alphabetizer

- Conclusion Generator

- List Randomizer

- Sentence Counter

- Speech to text

- Check Mark Symbol

- Bionic Reading Tool

- Fake Address Generator

- JPG To Word

- Random Choice Generator

- AI Content Detector

- Podcast Script Generator

- Poem Generator

- Story Generator

- Slogan Generator

- Business Idea Generator

- Cover Letter Generator

- Blurb Generator

- Blog Outline Generator

- Blog Idea Generator

- Essay Writer

- AI Email Writer

- Binary Translator

- Paragraph Generator

- Book Title generator

- Research Title Generator

- Business Name Generator

- AI Answer Generator

- FAQ Generator

Supported Languages

- Refund Policy

Adblock Detected!

Our website is made possible by displaying ads to our visitors. please support us by whitelisting our website.

What do you think about this tool?

Your submission has been received. We will be in touch and contact you soon!

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![research abstract website “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![research abstract website “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![research abstract website “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Abstract Writing: A Step-by-Step Guide With Tips & Examples

Table of Contents

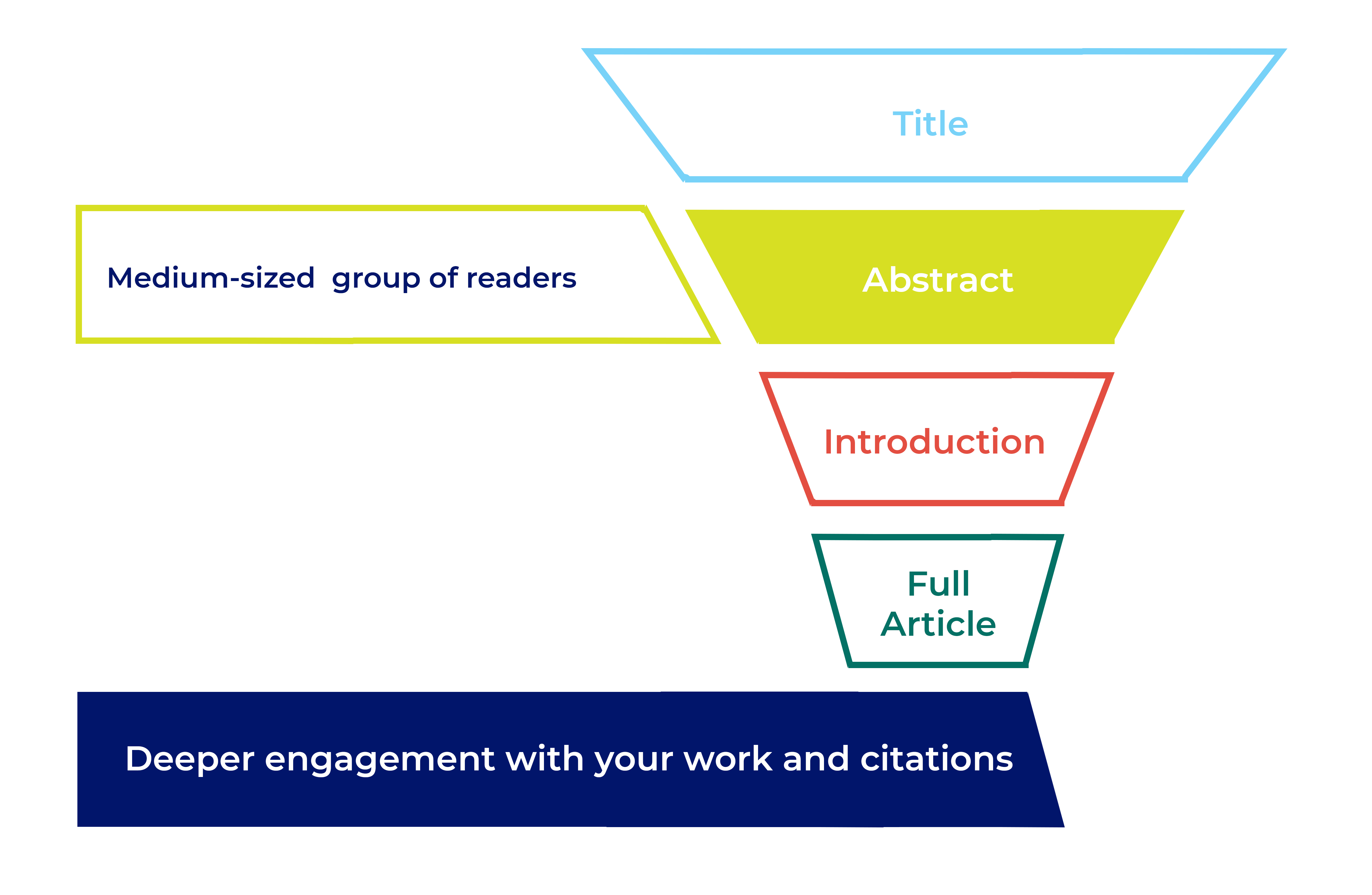

Introduction

Abstracts of research papers have always played an essential role in describing your research concisely and clearly to researchers and editors of journals, enticing them to continue reading. However, with the widespread availability of scientific databases, the need to write a convincing abstract is more crucial now than during the time of paper-bound manuscripts.

Abstracts serve to "sell" your research and can be compared with your "executive outline" of a resume or, rather, a formal summary of the critical aspects of your work. Also, it can be the "gist" of your study. Since most educational research is done online, it's a sign that you have a shorter time for impressing your readers, and have more competition from other abstracts that are available to be read.

The APCI (Academic Publishing and Conferences International) articulates 12 issues or points considered during the final approval process for conferences & journals and emphasises the importance of writing an abstract that checks all these boxes (12 points). Since it's the only opportunity you have to captivate your readers, you must invest time and effort in creating an abstract that accurately reflects the critical points of your research.

With that in mind, let’s head over to understand and discover the core concept and guidelines to create a substantial abstract. Also, learn how to organise the ideas or plots into an effective abstract that will be awe-inspiring to the readers you want to reach.

What is Abstract? Definition and Overview

The word "Abstract' is derived from Latin abstractus meaning "drawn off." This etymological meaning also applies to art movements as well as music, like abstract expressionism. In this context, it refers to the revealing of the artist's intention.

Based on this, you can determine the meaning of an abstract: A condensed research summary. It must be self-contained and independent of the body of the research. However, it should outline the subject, the strategies used to study the problem, and the methods implemented to attain the outcomes. The specific elements of the study differ based on the area of study; however, together, it must be a succinct summary of the entire research paper.

Abstracts are typically written at the end of the paper, even though it serves as a prologue. In general, the abstract must be in a position to:

- Describe the paper.

- Identify the problem or the issue at hand.

- Explain to the reader the research process, the results you came up with, and what conclusion you've reached using these results.

- Include keywords to guide your strategy and the content.

Furthermore, the abstract you submit should not reflect upon any of the following elements:

- Examine, analyse or defend the paper or your opinion.

- What you want to study, achieve or discover.

- Be redundant or irrelevant.

After reading an abstract, your audience should understand the reason - what the research was about in the first place, what the study has revealed and how it can be utilised or can be used to benefit others. You can understand the importance of abstract by knowing the fact that the abstract is the most frequently read portion of any research paper. In simpler terms, it should contain all the main points of the research paper.

What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

Abstracts are typically an essential requirement for research papers; however, it's not an obligation to preserve traditional reasons without any purpose. Abstracts allow readers to scan the text to determine whether it is relevant to their research or studies. The abstract allows other researchers to decide if your research paper can provide them with some additional information. A good abstract paves the interest of the audience to pore through your entire paper to find the content or context they're searching for.

Abstract writing is essential for indexing, as well. The Digital Repository of academic papers makes use of abstracts to index the entire content of academic research papers. Like meta descriptions in the regular Google outcomes, abstracts must include keywords that help researchers locate what they seek.

Types of Abstract

Informative and Descriptive are two kinds of abstracts often used in scientific writing.

A descriptive abstract gives readers an outline of the author's main points in their study. The reader can determine if they want to stick to the research work, based on their interest in the topic. An abstract that is descriptive is similar to the contents table of books, however, the format of an abstract depicts complete sentences encapsulated in one paragraph. It is unfortunate that the abstract can't be used as a substitute for reading a piece of writing because it's just an overview, which omits readers from getting an entire view. Also, it cannot be a way to fill in the gaps the reader may have after reading this kind of abstract since it does not contain crucial information needed to evaluate the article.

To conclude, a descriptive abstract is:

- A simple summary of the task, just summarises the work, but some researchers think it is much more of an outline

- Typically, the length is approximately 100 words. It is too short when compared to an informative abstract.

- A brief explanation but doesn't provide the reader with the complete information they need;

- An overview that omits conclusions and results

An informative abstract is a comprehensive outline of the research. There are times when people rely on the abstract as an information source. And the reason is why it is crucial to provide entire data of particular research. A well-written, informative abstract could be a good substitute for the remainder of the paper on its own.

A well-written abstract typically follows a particular style. The author begins by providing the identifying information, backed by citations and other identifiers of the papers. Then, the major elements are summarised to make the reader aware of the study. It is followed by the methodology and all-important findings from the study. The conclusion then presents study results and ends the abstract with a comprehensive summary.

In a nutshell, an informative abstract:

- Has a length that can vary, based on the subject, but is not longer than 300 words.

- Contains all the content-like methods and intentions

- Offers evidence and possible recommendations.

Informative Abstracts are more frequent than descriptive abstracts because of their extensive content and linkage to the topic specifically. You should select different types of abstracts to papers based on their length: informative abstracts for extended and more complex abstracts and descriptive ones for simpler and shorter research papers.

What are the Characteristics of a Good Abstract?

- A good abstract clearly defines the goals and purposes of the study.

- It should clearly describe the research methodology with a primary focus on data gathering, processing, and subsequent analysis.

- A good abstract should provide specific research findings.

- It presents the principal conclusions of the systematic study.

- It should be concise, clear, and relevant to the field of study.

- A well-designed abstract should be unifying and coherent.

- It is easy to grasp and free of technical jargon.

- It is written impartially and objectively.

What are the various sections of an ideal Abstract?

By now, you must have gained some concrete idea of the essential elements that your abstract needs to convey . Accordingly, the information is broken down into six key sections of the abstract, which include:

An Introduction or Background

Research methodology, objectives and goals, limitations.

Let's go over them in detail.

The introduction, also known as background, is the most concise part of your abstract. Ideally, it comprises a couple of sentences. Some researchers only write one sentence to introduce their abstract. The idea behind this is to guide readers through the key factors that led to your study.

It's understandable that this information might seem difficult to explain in a couple of sentences. For example, think about the following two questions like the background of your study:

- What is currently available about the subject with respect to the paper being discussed?

- What isn't understood about this issue? (This is the subject of your research)

While writing the abstract’s introduction, make sure that it is not lengthy. Because if it crosses the word limit, it may eat up the words meant to be used for providing other key information.

Research methodology is where you describe the theories and techniques you used in your research. It is recommended that you describe what you have done and the method you used to get your thorough investigation results. Certainly, it is the second-longest paragraph in the abstract.

In the research methodology section, it is essential to mention the kind of research you conducted; for instance, qualitative research or quantitative research (this will guide your research methodology too) . If you've conducted quantitative research, your abstract should contain information like the sample size, data collection method, sampling techniques, and duration of the study. Likewise, your abstract should reflect observational data, opinions, questionnaires (especially the non-numerical data) if you work on qualitative research.

The research objectives and goals speak about what you intend to accomplish with your research. The majority of research projects focus on the long-term effects of a project, and the goals focus on the immediate, short-term outcomes of the research. It is possible to summarise both in just multiple sentences.

In stating your objectives and goals, you give readers a picture of the scope of the study, its depth and the direction your research ultimately follows. Your readers can evaluate the results of your research against the goals and stated objectives to determine if you have achieved the goal of your research.

In the end, your readers are more attracted by the results you've obtained through your study. Therefore, you must take the time to explain each relevant result and explain how they impact your research. The results section exists as the longest in your abstract, and nothing should diminish its reach or quality.

One of the most important things you should adhere to is to spell out details and figures on the results of your research.

Instead of making a vague assertion such as, "We noticed that response rates varied greatly between respondents with high incomes and those with low incomes", Try these: "The response rate was higher for high-income respondents than those with lower incomes (59 30 percent vs. 30 percent in both cases; P<0.01)."

You're likely to encounter certain obstacles during your research. It could have been during data collection or even during conducting the sample . Whatever the issue, it's essential to inform your readers about them and their effects on the research.

Research limitations offer an opportunity to suggest further and deep research. If, for instance, you were forced to change for convenient sampling and snowball samples because of difficulties in reaching well-suited research participants, then you should mention this reason when you write your research abstract. In addition, a lack of prior studies on the subject could hinder your research.

Your conclusion should include the same number of sentences to wrap the abstract as the introduction. The majority of researchers offer an idea of the consequences of their research in this case.

Your conclusion should include three essential components:

- A significant take-home message.

- Corresponding important findings.

- The Interpretation.

Even though the conclusion of your abstract needs to be brief, it can have an enormous influence on the way that readers view your research. Therefore, make use of this section to reinforce the central message from your research. Be sure that your statements reflect the actual results and the methods you used to conduct your research.

Good Abstract Examples

Abstract example #1.

Children’s consumption behavior in response to food product placements in movies.

The abstract:

"Almost all research into the effects of brand placements on children has focused on the brand's attitudes or behavior intentions. Based on the significant differences between attitudes and behavioral intentions on one hand and actual behavior on the other hand, this study examines the impact of placements by brands on children's eating habits. Children aged 6-14 years old were shown an excerpt from the popular film Alvin and the Chipmunks and were shown places for the item Cheese Balls. Three different versions were developed with no placements, one with moderately frequent placements and the third with the highest frequency of placement. The results revealed that exposure to high-frequency places had a profound effect on snack consumption, however, there was no impact on consumer attitudes towards brands or products. The effects were not dependent on the age of the children. These findings are of major importance to researchers studying consumer behavior as well as nutrition experts as well as policy regulators."

Abstract Example #2

Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. The abstract:

"The research conducted in this study investigated the effects of Facebook use on women's moods and body image if the effects are different from an internet-based fashion journal and if the appearance comparison tendencies moderate one or more of these effects. Participants who were female ( N = 112) were randomly allocated to spend 10 minutes exploring their Facebook account or a magazine's website or an appearance neutral control website prior to completing state assessments of body dissatisfaction, mood, and differences in appearance (weight-related and facial hair, face, and skin). Participants also completed a test of the tendency to compare appearances. The participants who used Facebook were reported to be more depressed than those who stayed on the control site. In addition, women who have the tendency to compare appearances reported more facial, hair and skin-related issues following Facebook exposure than when they were exposed to the control site. Due to its popularity it is imperative to conduct more research to understand the effect that Facebook affects the way people view themselves."

Abstract Example #3

The Relationship Between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College Students

"The cellphone is always present on campuses of colleges and is often utilised in situations in which learning takes place. The study examined the connection between the use of cell phones and the actual grades point average (GPA) after adjusting for predictors that are known to be a factor. In the end 536 students in the undergraduate program from 82 self-reported majors of an enormous, public institution were studied. Hierarchical analysis ( R 2 = .449) showed that use of mobile phones is significantly ( p < .001) and negative (b equal to -.164) connected to the actual college GPA, after taking into account factors such as demographics, self-efficacy in self-regulated learning, self-efficacy to improve academic performance, and the actual high school GPA that were all important predictors ( p < .05). Therefore, after adjusting for other known predictors increasing cell phone usage was associated with lower academic performance. While more research is required to determine the mechanisms behind these results, they suggest the need to educate teachers and students to the possible academic risks that are associated with high-frequency mobile phone usage."

Quick tips on writing a good abstract

There exists a common dilemma among early age researchers whether to write the abstract at first or last? However, it's recommended to compose your abstract when you've completed the research since you'll have all the information to give to your readers. You can, however, write a draft at the beginning of your research and add in any gaps later.

If you find abstract writing a herculean task, here are the few tips to help you with it:

1. Always develop a framework to support your abstract

Before writing, ensure you create a clear outline for your abstract. Divide it into sections and draw the primary and supporting elements in each one. You can include keywords and a few sentences that convey the essence of your message.

2. Review Other Abstracts

Abstracts are among the most frequently used research documents, and thousands of them were written in the past. Therefore, prior to writing yours, take a look at some examples from other abstracts. There are plenty of examples of abstracts for dissertations in the dissertation and thesis databases.

3. Avoid Jargon To the Maximum

When you write your abstract, focus on simplicity over formality. You should write in simple language, and avoid excessive filler words or ambiguous sentences. Keep in mind that your abstract must be readable to those who aren't acquainted with your subject.

4. Focus on Your Research

It's a given fact that the abstract you write should be about your research and the findings you've made. It is not the right time to mention secondary and primary data sources unless it's absolutely required.

Conclusion: How to Structure an Interesting Abstract?

Abstracts are a short outline of your essay. However, it's among the most important, if not the most important. The process of writing an abstract is not straightforward. A few early-age researchers tend to begin by writing it, thinking they are doing it to "tease" the next step (the document itself). However, it is better to treat it as a spoiler.

The simple, concise style of the abstract lends itself to a well-written and well-investigated study. If your research paper doesn't provide definitive results, or the goal of your research is questioned, so will the abstract. Thus, only write your abstract after witnessing your findings and put your findings in the context of a larger scenario.

The process of writing an abstract can be daunting, but with these guidelines, you will succeed. The most efficient method of writing an excellent abstract is to centre the primary points of your abstract, including the research question and goals methods, as well as key results.

Interested in learning more about dedicated research solutions? Go to the SciSpace product page to find out how our suite of products can help you simplify your research workflows so you can focus on advancing science.

The best-in-class solution is equipped with features such as literature search and discovery, profile management, research writing and formatting, and so much more.

But before you go,

You might also like.

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

The Writing Planet

50 % off on all orders

Research Paper Abstract Generator

The abstract of a research paper provides a key summary of your paper. They give the reader a summary of your paper; however, the majority of individuals are terrified of writing this essential section.

Why? It may determine the success or failure of a paper.

Would you like to present at a conference? You must include an abstract with your application, and it must pique the reviewers’ interest. When you submit your paper for grading or present the field in which you worked with your most recent study, your abstract must be as strong as possible.

Although it may appear scary, especially if this is your first time, we have provided you with information on what abstracts are and basic instructions on how to write abstracts for a variety of scenarios.

What Is a Research Paper Abstract Generator?

Using superior AI technology, the abstract generator enables you to compose an abstract for your research paper. The free abstract generator generates a title and precise description of the material given with a single click. The research paper abstract generator generates an acceptable research paper abstract by including the most pertinent and essential phrases from the paper’s body.

What Is An Abstract?

Let’s define an abstract prior to entering the abstract domain.

An abstract is a succinct and unambiguous overview that comprises your hypothesis, the context of your study, a sentence or two describing your methodology, and your conclusion. It provides viewers with a preview of your work and helps them decide whether to read it. Consider it a more in-depth book summary or movie trailer! Including all of this essential information enables others to acquire the knowledge they need for their professions fast. Importantly, your abstract should be concise; you should aim for between 100 and 500 words. Aim for around 300 words for an exact word count.

Your abstract is not an expansion or evaluation of your research work, nor is it a criticism or suggestion. Its purpose is to explain your article. When submitting your work for evaluation, publishing, submission to a regulatory body, or permission to speak at a conference, you are typically expected to produce an abstract. Consequently, your abstract must contain a great deal of information. Refrain from believing that a single notion will suffice in all of these circumstances.

Writing an Abstract

You may be tempted to write your abstract first because it will be the first section of your paper, but it’s better to wait until you’ve done your entire project so you know exactly what you’re summarizing. If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may provide you with precise guidelines on its content and structure. Similarly, scientific publications often adhere to stringent abstract standards. In addition to following the directions on this page, you should look for and adhere to any rules from the course or publication for which you are writing.

The Structure of a Research Paper

Willing to examine scientific publications, evaluate several studies, and even learn how a research paper summary tool operates? In this case, you will be inquisitive about the structure of such academic papers. Here, we have just described the normal format of scholarly papers.

Include the following sections in your research paper:

The abstract of a research paper provides a summary of the research project. It emphasizes the premise and noteworthy findings. Your audience will utilize it to comprehend the overall concept and purpose of the study rapidly. Utilize our online summary generator for this section. Abstracts in scientific works are often one paragraph at maximum.

Introduction

In the beginning, you should situate your study subject. Describe the subject and include any pertinent earlier research. Additionally, this is where you would typically outline a knowledge gap you wish to address. Explain why the topic you are addressing is significant and requires more examination.

Methodology

In this part, you must describe the study’s methodology. Describe how the research was conducted and who was involved. Describe your methodology as well as the materials and technologies employed. You must also outline the data collecting and analysis procedures. It is essential to remember that someone else should be able to duplicate your study using these ideas.

In the results portion of your research report, you will provide the collected data. You must also include the findings of any statistical tests you conduct. Keep in mind the main research questions throughout this strategy. In this area, you should relate your findings to it.

Explain the relevance of your methodology and results once you have completed your report. Discuss the consequences of the most significant components of your study. Consider your topic and your objectives for the research. Discuss its flaws and how they can be addressed in the future.

The final portion of your work is a bibliography also known as references. It is a list of the sources you consulted for your paper. It should be formatted according to your school’s specifications. Ensure that things are organized alphabetically.

Instructions for Writing an Abstract

It may take a great deal of effort to condense your whole work into a few hundred words, but the research paper abstract will be the first (and often only) item that people read, so it is crucial that it be written correctly. These tips can help you get started.

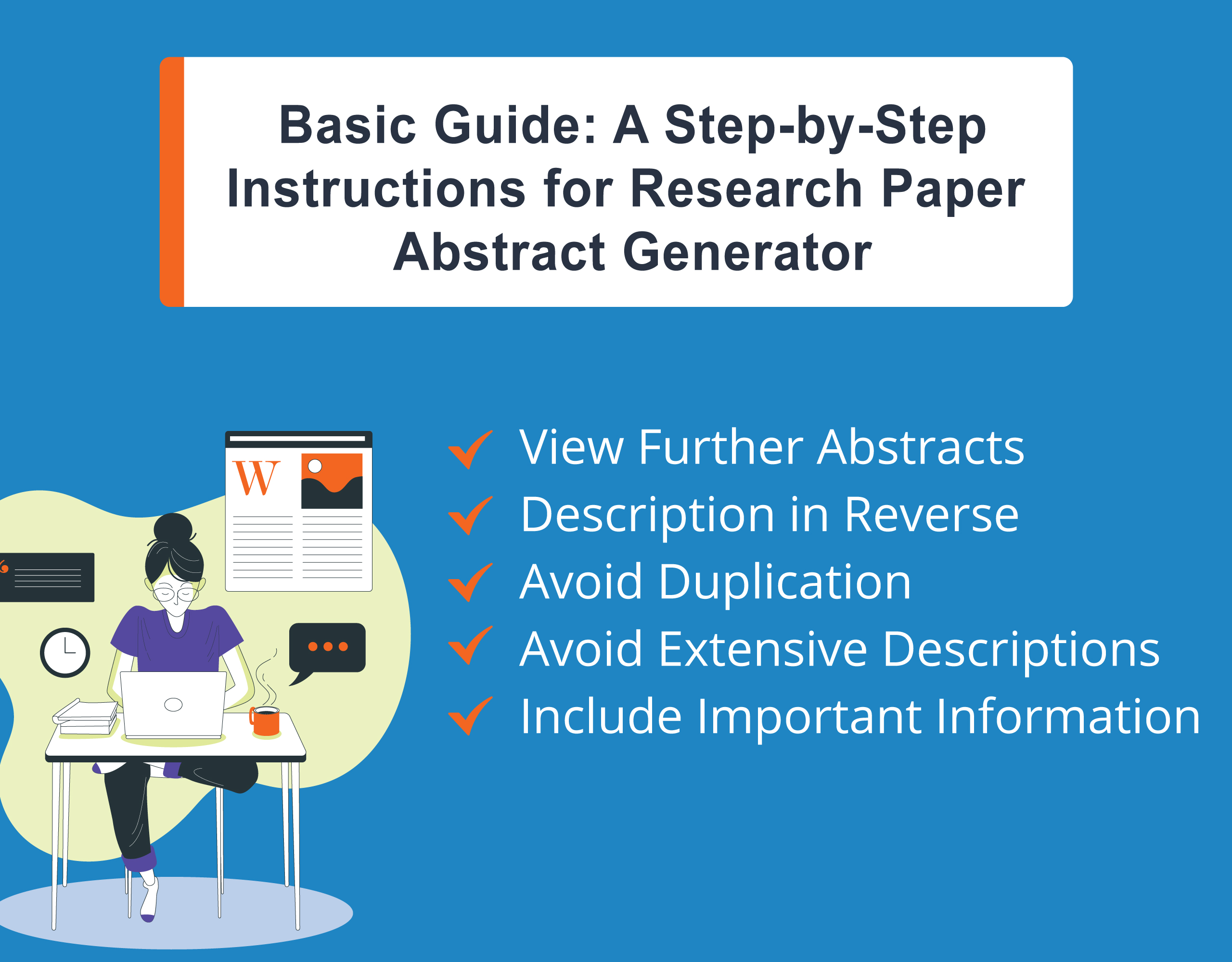

View Further Abstracts

Reading the abstracts of others is the best approach to learning how to write an abstract on your topic. Consider utilizing journal article abstracts as a model for organization and style, as you have likely read hundreds of them while performing your research review. Thesis and dissertation databases also provide hundreds of samples of dissertation abstracts.

Description in Reverse

Not all abstractions will include identical components. For lengthier works, write your abstract in reverse outline format. Each chapter or section should include a list of keywords and a one- to a two-line summary of the major point or argument. This will serve as a guide for the organization of your abstract. Then, modify the phrases to establish connections and illustrate how the argument develops.

Write Effectively and Concisely

An effective abstract is concise and persuasive, so ensure that every word counts. Each sentence should elaborate on a significant point.

Passive Expressions Must Be Avoided

Frequently, passive construction should be shorter. Employ the active voice to make them shorter and more comprehensible.

Avoid Using Obscure Jargon

The abstract should be understandable to those unfamiliar with the subject matter.

Avoid Duplication and Filler

Replace nouns with pronouns wherever feasible and avoid using unneeded words.

Avoid Extensive Descriptions

The purpose of an abstract is not to provide detailed definitions, context, or commentary on the work of other scholars. Instead, provide this material in the body of your dissertation or paper.

Investigate Your Formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a publication, the abstract must be structured exactly; be sure to adhere to the instructions and prepare your work accordingly. APA research papers may utilize the APA abstract format.

Only Copy Complete Phrases from Papers

In theory, it may appear to be a great strategy, but in practice, it will just bring you headaches. You will need more than just using terminology from your work to write a clear, accurate, and succinct abstract. This will prevent your abstract from becoming an actual abstract and will likely make it illogical.

Include Important Information

You must include the required information in your abstract to be accepted.

Avoid Adding Too Many Details

To qualify the preceding point, it is also a major no-no to provide too much information in your abstract. Finding the optimal balance might be challenging; thus, your abstract should be clear and transparent. Remove unnecessary phrases and terms that “fluff up” your research.

Your Abstract Is What Piques the Reader’s Curiosity

Unfortunately, they only have time to read your entire paper, especially in the case of conference submissions. The readers want to know if your work will aid them with their study or if it is the appropriate piece for their conference.

What Makes A Bad Abstract?

Not following abstract structure directions.

If you have been informed of the structure and format that the institution to which you are submitting your abstract requires, adhere to it precisely. Remember to include everything, and do not assume that if you miss one small detail, it will not matter because it will!

Omission to Include Important Keywords

In order for your abstract/paper to be effectively indexed and easily discoverable, you must include keywords.

Not Offering an Exhaustive Overview

You must provide a brief description of each section of your work. You’ve included the results, but if you have an introduction, method, outcomes/results, and analysis/discussion, you must summarize them all in your abstract.

Online Services for Abstract Writing

Researchers devoted a number of hours to ensuring that their investigation was conducted thoroughly and precisely that all approaches and new discoveries were examined, and that every minute observation was recorded.

So, when it’s time to publish your work, how can you condense your research into a concise essay that satisfies the Journal’s stringent requirements without sacrificing essential information?

You have access to a number of online abstract writing services . These services will condense your whole material without compromising vital details or the effectiveness of your work. These online writing services will also ensure that the content flows logically and is accessible to a wide variety of readers. Your abstract will also contain potent keywords that will increase your database search results.

Research paper abstracts are an excellent way for summarizing your study for your audience. It describes the nature of the inquiry, the methodology employed, and the results. Consider refining your academic writing abilities in order to excel in your abstract. In addition, despite the fact that writing an abstract may first look tough, if you follow the guidelines provided above, you should find the process easier and more fun.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to write a good research paper abstract.

An abstract should be able to be understood without reading the full article or consulting any other resources. It emphasizes important subject areas, the purpose of your research, the relevance of your work, and the primary conclusions.

How do I start an abstract research paper?

The abstract should begin with a brief yet precise statement of the problem or topic, followed by a discussion of the research methods and methodology, the noteworthy results, and the conclusions reached.

Previous Posts

Write My Research Paper for Me to get an ‘A ‘ grade?

Research Paper Help – Professional Writing Assistance

What Is The Difference Between Research Paper and Essay

Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- How to write and format an APA abstract

APA Abstract (2020) | Formatting, Length, and Keywords

Published on November 6, 2020 by Raimo Streefkerk . Revised on January 17, 2024.

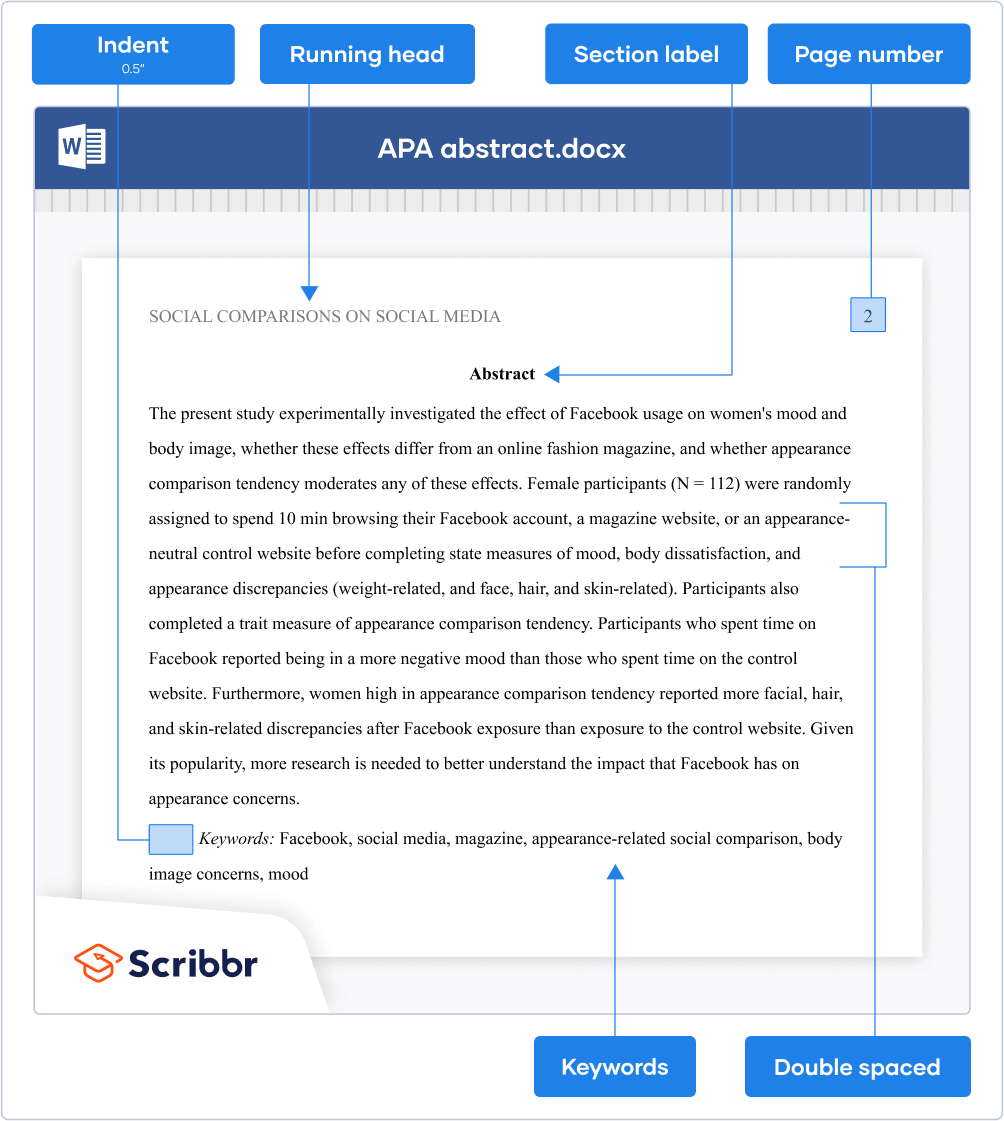

An APA abstract is a comprehensive summary of your paper in which you briefly address the research problem , hypotheses , methods , results , and implications of your research. It’s placed on a separate page right after the title page and is usually no longer than 250 words.

Most professional papers that are submitted for publication require an abstract. Student papers typically don’t need an abstract, unless instructed otherwise.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

How to format the abstract, how to write an apa abstract, which keywords to use, frequently asked questions, apa abstract example.

Formatting instructions

Follow these five steps to format your abstract in APA Style:

- Insert a running head (for a professional paper—not needed for a student paper) and page number.

- Set page margins to 1 inch (2.54 cm).

- Write “Abstract” (bold and centered) at the top of the page.

- Do not indent the first line.

- Double-space the text.

- Use a legible font like Times New Roman (12 pt.).

- Limit the length to 250 words.

- Indent the first line 0.5 inches.

- Write the label “Keywords:” (italicized).

- Write keywords in lowercase letters.

- Separate keywords with commas.

- Do not use a period after the keywords.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

The abstract is a self-contained piece of text that informs the reader what your research is about. It’s best to write the abstract after you’re finished with the rest of your paper.

The questions below may help structure your abstract. Try answering them in one to three sentences each.

- What is the problem? Outline the objective, research questions , and/or hypotheses .

- What has been done? Explain your research methods .

- What did you discover? Summarize the key findings and conclusions .

- What do the findings mean? Summarize the discussion and recommendations .

Check out our guide on how to write an abstract for more guidance and an annotated example.

Guide: writing an abstract

At the end of the abstract, you may include a few keywords that will be used for indexing if your paper is published on a database. Listing your keywords will help other researchers find your work.

Choosing relevant keywords is essential. Try to identify keywords that address your topic, method, or population. APA recommends including three to five keywords.

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An APA abstract is around 150–250 words long. However, always check your target journal’s guidelines and don’t exceed the specified word count.

In an APA Style paper , the abstract is placed on a separate page after the title page (page 2).

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Streefkerk, R. (2024, January 17). APA Abstract (2020) | Formatting, Length, and Keywords. Scribbr. Retrieved April 10, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/apa-abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Raimo Streefkerk

Other students also liked, apa headings and subheadings, apa running head, apa title page (7th edition) | template for students & professionals, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper | Examples

What is a research paper abstract?

Research paper abstracts summarize your study quickly and succinctly to journal editors and researchers and prompt them to read further. But with the ubiquity of online publication databases, writing a compelling abstract is even more important today than it was in the days of bound paper manuscripts.

Abstracts exist to “sell” your work, and they could thus be compared to the “executive summary” of a business resume: an official briefing on what is most important about your research. Or the “gist” of your research. With the majority of academic transactions being conducted online, this means that you have even less time to impress readers–and increased competition in terms of other abstracts out there to read.

The APCI (Academic Publishing and Conferences International) notes that there are 12 questions or “points” considered in the selection process for journals and conferences and stresses the importance of having an abstract that ticks all of these boxes. Because it is often the ONLY chance you have to convince readers to keep reading, it is important that you spend time and energy crafting an abstract that faithfully represents the central parts of your study and captivates your audience.

With that in mind, follow these suggestions when structuring and writing your abstract, and learn how exactly to put these ideas into a solid abstract that will captivate your target readers.

Before Writing Your Abstract

How long should an abstract be.

All abstracts are written with the same essential objective: to give a summary of your study. But there are two basic styles of abstract: descriptive and informative . Here is a brief delineation of the two:

Of the two types of abstracts, informative abstracts are much more common, and they are widely used for submission to journals and conferences. Informative abstracts apply to lengthier and more technical research and are common in the sciences, engineering, and psychology, while descriptive abstracts are more likely used in humanities and social science papers. The best method of determining which abstract type you need to use is to follow the instructions for journal submissions and to read as many other published articles in those journals as possible.

Research Abstract Guidelines and Requirements

As any article about research writing will tell you, authors must always closely follow the specific guidelines and requirements indicated in the Guide for Authors section of their target journal’s website. The same kind of adherence to conventions should be applied to journal publications, for consideration at a conference, and even when completing a class assignment.

Each publisher has particular demands when it comes to formatting and structure. Here are some common questions addressed in the journal guidelines:

- Is there a maximum or minimum word/character length?

- What are the style and formatting requirements?

- What is the appropriate abstract type?

- Are there any specific content or organization rules that apply?

There are of course other rules to consider when composing a research paper abstract. But if you follow the stated rules the first time you submit your manuscript, you can avoid your work being thrown in the “circular file” right off the bat.

Identify Your Target Readership

The main purpose of your abstract is to lead researchers to the full text of your research paper. In scientific journals, abstracts let readers decide whether the research discussed is relevant to their own interests or study. Abstracts also help readers understand your main argument quickly. Consider these questions as you write your abstract:

- Are other academics in your field the main target of your study?

- Will your study perhaps be useful to members of the general public?

- Do your study results include the wider implications presented in the abstract?

Outlining and Writing Your Abstract

What to include in an abstract.

Just as your research paper title should cover as much ground as possible in a few short words, your abstract must cover all parts of your study in order to fully explain your paper and research. Because it must accomplish this task in the space of only a few hundred words, it is important not to include ambiguous references or phrases that will confuse the reader or mislead them about the content and objectives of your research. Follow these dos and don’ts when it comes to what kind of writing to include:

- Avoid acronyms or abbreviations since these will need to be explained in order to make sense to the reader, which takes up valuable abstract space. Instead, explain these terms in the Introduction section of the main text.

- Only use references to people or other works if they are well-known. Otherwise, avoid referencing anything outside of your study in the abstract.

- Never include tables, figures, sources, or long quotations in your abstract; you will have plenty of time to present and refer to these in the body of your paper.

Use keywords in your abstract to focus your topic

A vital search tool is the research paper keywords section, which lists the most relevant terms directly underneath the abstract. Think of these keywords as the “tubes” that readers will seek and enter—via queries on databases and search engines—to ultimately land at their destination, which is your paper. Your abstract keywords should thus be words that are commonly used in searches but should also be highly relevant to your work and found in the text of your abstract. Include 5 to 10 important words or short phrases central to your research in both the abstract and the keywords section.

For example, if you are writing a paper on the prevalence of obesity among lower classes that crosses international boundaries, you should include terms like “obesity,” “prevalence,” “international,” “lower classes,” and “cross-cultural.” These are terms that should net a wide array of people interested in your topic of study. Look at our nine rules for choosing keywords for your research paper if you need more input on this.

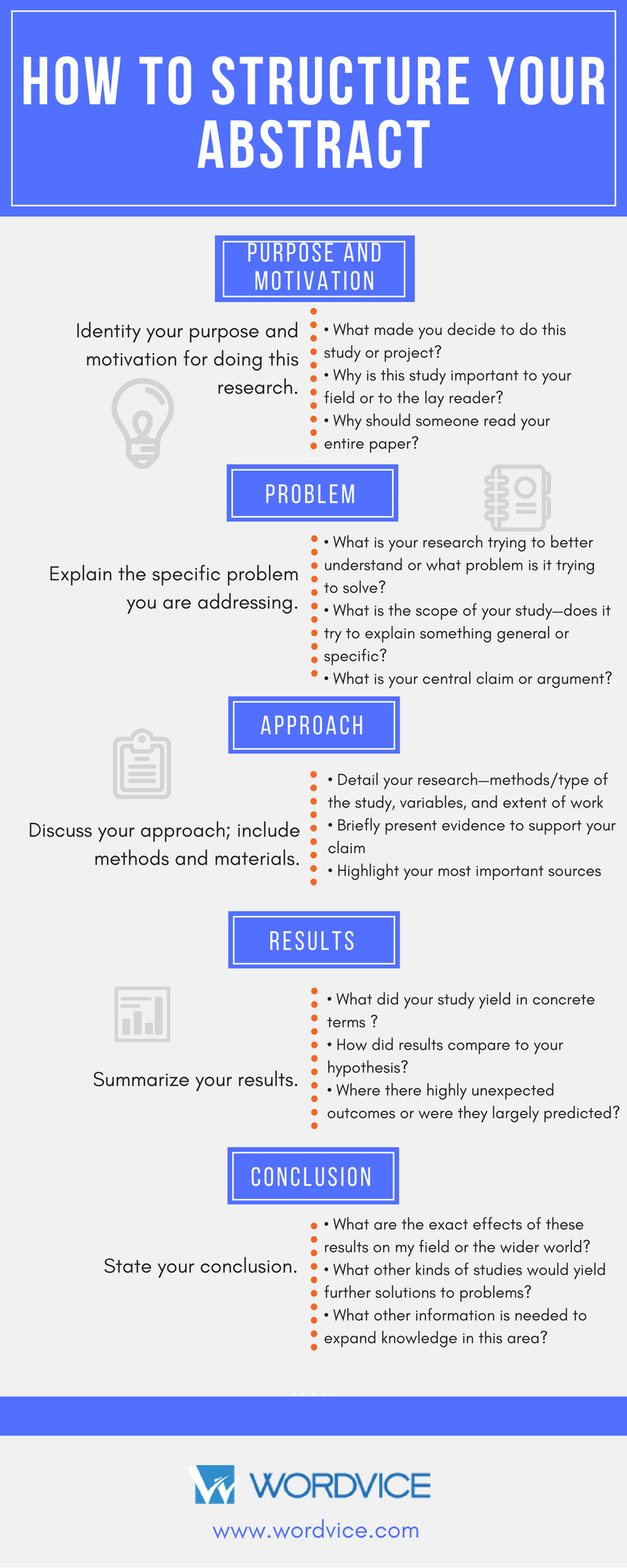

Research Paper Abstract Structure

As mentioned above, the abstract (especially the informative abstract) acts as a surrogate or synopsis of your research paper, doing almost as much work as the thousands of words that follow it in the body of the main text. In the hard sciences and most social sciences, the abstract includes the following sections and organizational schema.

Each section is quite compact—only a single sentence or two, although there is room for expansion if one element or statement is particularly interesting or compelling. As the abstract is almost always one long paragraph, the individual sections should naturally merge into one another to create a holistic effect. Use the following as a checklist to ensure that you have included all of the necessary content in your abstract.

1) Identify your purpose and motivation

So your research is about rabies in Brazilian squirrels. Why is this important? You should start your abstract by explaining why people should care about this study—why is it significant to your field and perhaps to the wider world? And what is the exact purpose of your study; what are you trying to achieve? Start by answering the following questions:

- What made you decide to do this study or project?

- Why is this study important to your field or to the lay reader?

- Why should someone read your entire article?

In summary, the first section of your abstract should include the importance of the research and its impact on related research fields or on the wider scientific domain.

2) Explain the research problem you are addressing

Stating the research problem that your study addresses is the corollary to why your specific study is important and necessary. For instance, even if the issue of “rabies in Brazilian squirrels” is important, what is the problem—the “missing piece of the puzzle”—that your study helps resolve?

You can combine the problem with the motivation section, but from a perspective of organization and clarity, it is best to separate the two. Here are some precise questions to address:

- What is your research trying to better understand or what problem is it trying to solve?

- What is the scope of your study—does it try to explain something general or specific?

- What is your central claim or argument?

3) Discuss your research approach

Your specific study approach is detailed in the Methods and Materials section . You have already established the importance of the research, your motivation for studying this issue, and the specific problem your paper addresses. Now you need to discuss how you solved or made progress on this problem—how you conducted your research. If your study includes your own work or that of your team, describe that here. If in your paper you reviewed the work of others, explain this here. Did you use analytic models? A simulation? A double-blind study? A case study? You are basically showing the reader the internal engine of your research machine and how it functioned in the study. Be sure to:

- Detail your research—include methods/type of the study, your variables, and the extent of the work

- Briefly present evidence to support your claim

- Highlight your most important sources

4) Briefly summarize your results

Here you will give an overview of the outcome of your study. Avoid using too many vague qualitative terms (e.g, “very,” “small,” or “tremendous”) and try to use at least some quantitative terms (i.e., percentages, figures, numbers). Save your qualitative language for the conclusion statement. Answer questions like these:

- What did your study yield in concrete terms (e.g., trends, figures, correlation between phenomena)?

- How did your results compare to your hypothesis? Was the study successful?

- Where there any highly unexpected outcomes or were they all largely predicted?

5) State your conclusion

In the last section of your abstract, you will give a statement about the implications and limitations of the study . Be sure to connect this statement closely to your results and not the area of study in general. Are the results of this study going to shake up the scientific world? Will they impact how people see “Brazilian squirrels”? Or are the implications minor? Try not to boast about your study or present its impact as too far-reaching, as researchers and journals will tend to be skeptical of bold claims in scientific papers. Answer one of these questions:

- What are the exact effects of these results on my field? On the wider world?

- What other kind of study would yield further solutions to problems?

- What other information is needed to expand knowledge in this area?

After Completing the First Draft of Your Abstract

Revise your abstract.

The abstract, like any piece of academic writing, should be revised before being considered complete. Check it for grammatical and spelling errors and make sure it is formatted properly.

Get feedback from a peer

Getting a fresh set of eyes to review your abstract is a great way to find out whether you’ve summarized your research well. Find a reader who understands research papers but is not an expert in this field or is not affiliated with your study. Ask your reader to summarize what your study is about (including all key points of each section). This should tell you if you have communicated your key points clearly.

In addition to research peers, consider consulting with a professor or even a specialist or generalist writing center consultant about your abstract. Use any resource that helps you see your work from another perspective.

Consider getting professional editing and proofreading

While peer feedback is quite important to ensure the effectiveness of your abstract content, it may be a good idea to find an academic editor to fix mistakes in grammar, spelling, mechanics, style, or formatting. The presence of basic errors in the abstract may not affect your content, but it might dissuade someone from reading your entire study. Wordvice provides English editing services that both correct objective errors and enhance the readability and impact of your work.

Additional Abstract Rules and Guidelines

Write your abstract after completing your paper.

Although the abstract goes at the beginning of your manuscript, it does not merely introduce your research topic (that is the job of the title), but rather summarizes your entire paper. Writing the abstract last will ensure that it is complete and consistent with the findings and statements in your paper.

Keep your content in the correct order

Both questions and answers should be organized in a standard and familiar way to make the content easier for readers to absorb. Ideally, it should mimic the overall format of your essay and the classic “introduction,” “body,” and “conclusion” form, even if the parts are not neatly divided as such.

Write the abstract from scratch

Because the abstract is a self-contained piece of writing viewed separately from the body of the paper, you should write it separately as well. Never copy and paste direct quotes from the paper and avoid paraphrasing sentences in the paper. Using new vocabulary and phrases will keep your abstract interesting and free of redundancies while conserving space.

Don’t include too many details in the abstract

Again, the density of your abstract makes it incompatible with including specific points other than possibly names or locations. You can make references to terms, but do not explain or define them in the abstract. Try to strike a balance between being specific to your study and presenting a relatively broad overview of your work.

Wordvice Resources

If you think your abstract is fine now but you need input on abstract writing or require English editing services (including paper editing ), then head over to the Wordvice academic resources page, where you will find many more articles, for example on writing the Results , Methods , and Discussion sections of your manuscript, on choosing a title for your paper , or on how to finalize your journal submission with a strong cover letter .

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write an Abstract

Expedite peer review, increase search-ability, and set the tone for your study

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

How your abstract impacts editorial evaluation and future readership

After the title , the abstract is the second-most-read part of your article. A good abstract can help to expedite peer review and, if your article is accepted for publication, it’s an important tool for readers to find and evaluate your work. Editors use your abstract when they first assess your article. Prospective reviewers see it when they decide whether to accept an invitation to review. Once published, the abstract gets indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar , as well as library systems and other popular databases. Like the title, your abstract influences keyword search results. Readers will use it to decide whether to read the rest of your article. Other researchers will use it to evaluate your work for inclusion in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. It should be a concise standalone piece that accurately represents your research.

What to include in an abstract

The main challenge you’ll face when writing your abstract is keeping it concise AND fitting in all the information you need. Depending on your subject area the journal may require a structured abstract following specific headings. A structured abstract helps your readers understand your study more easily. If your journal doesn’t require a structured abstract it’s still a good idea to follow a similar format, just present the abstract as one paragraph without headings.