COMING SOON:

Claim a free copy of this 620-page vocabulary building workbook

approach,plan,practice,strategy

eb68db_7203d90e20f147e99f522f8637911ed4.mp3

system, improvisation, randomness, guesswork

framework,modus-operandi,procedure,process,protocol,system,technique

methodology

Dictionary definition of methodology

The systematic and theoretical principles, practices, and procedures that are used in a particular field of study or research. "The organization implemented a new sales methodology to improve customer engagement."

- X (Twitter)

Detailed meaning of methodology

It encompasses the overall approach or framework employed to investigate, analyze, and solve problems within a specific discipline or domain. Methodology outlines the methods, techniques, tools, and strategies employed to gather, interpret, and evaluate data or information. It involves the systematic planning, design, and execution of research or investigative activities to achieve specific objectives. Methodology is crucial in maintaining rigor, accuracy, and consistency in various areas such as scientific research, social sciences, market research, and academic studies. It provides a structured and organized way to conduct investigations, generate reliable results, and ensure the validity and reliability of the findings. A well-defined methodology helps researchers and practitioners navigate the process of inquiry and inquiry and enhances the credibility and reproducibility of their work.

Example sentences of methodology

1. The researcher employed a rigorous methodology to collect and analyze the data. 2. The team followed a systematic methodology to develop the software. 3. The study's methodology involved conducting surveys and interviews with participants. 4. The professor emphasized the importance of understanding research methodology in the social sciences. 5. The company adopted an agile methodology for project management. 6. The methodology used in the experiment ensured accurate and reliable results.

History and etymology of methodology

The noun 'methodology' draws its etymological roots from the Greek word 'methodologia,' where 'meta' signifies 'beyond' or 'transcending,' and 'logos' represents 'word,' 'study,' or 'discourse.' When dissecting its etymology, we discern that 'methodology' encompasses the systematic and theoretical principles, practices, and procedures that extend beyond mere words or discourse within a specific field of study or research. It implies a comprehensive and structured framework that transcends mere discussion, underlining the importance of a well-organized approach to scholarly inquiry and research in various domains.

Find the meaning of methodology

Continue Quiz

Further usage examples of methodology

1. The historian employed a comparative methodology to analyze historical events. 2. The methodology of the study was peer-reviewed to ensure its validity. 3. The artist's creative methodology involved a combination of traditional and digital techniques. 4. The researcher explained the sampling methodology used to select participants for the study. 5. The scientist published a paper outlining the methodology and findings of their research. 6. The researcher explained the methodology used in the study to ensure transparency. 7. The company adopted a new marketing methodology to target a wider audience. 8. The teacher implemented a student-centered methodology to promote active learning. 9. The software developer followed an agile methodology to improve product development efficiency. 10. The historian questioned the methodology employed by previous scholars in interpreting historical events. 11. The psychologist developed a unique methodology for assessing cognitive abilities in children. 12. The consultant presented a comprehensive methodology for streamlining business operations. 13. The archaeologist used a meticulous excavation methodology to preserve artifacts. 14. The journalist investigated the validity of the survey methodology used in the report. 15. The artist embraced a mixed-media methodology, combining different art forms in their work. 16. The coach employed a data-driven methodology to analyze player performance and make strategic decisions. 17. The quality assurance team implemented a rigorous testing methodology to ensure product reliability. 18. The economist proposed a new methodology for measuring economic growth in emerging markets. 19. The linguist conducted field research using ethnographic methodology to study language evolution. 20. The project manager outlined a clear methodology for executing the construction project. 21. The philosopher critically examined the philosophical methodologies employed by different schools of thought. 22. The statistician devised a sampling methodology to ensure representative data collection. 23. The educational researcher developed a quantitative methodology to measure learning outcomes. 24. The sociologist employed qualitative research methodologies, conducting interviews and observations. 25. The environmental scientist adopted a multidisciplinary methodology to assess the impact of pollution.

Quiz categories containing methodology

Multiple Choice

Opposite Words

Same/different

Spelling Bee

- Trending words:

A Word or Two

IMMODEST DISPOSAL

Chile con Frontation

methodology

Questions about grammar and vocabulary?

Find the answers with Practical English Usage online, your indispensable guide to problems in English.

Nearby words

Words and phrases

Personal account.

- Access or purchase personal subscriptions

- Get our newsletter

- Save searches

- Set display preferences

Institutional access

Sign in with library card

Sign in with username / password

Recommend to your librarian

Institutional account management

Sign in as administrator on Oxford Academic

method noun

- Hide all quotations

What does the noun method mean?

There are 22 meanings listed in OED's entry for the noun method , 11 of which are labelled obsolete. See ‘Meaning & use’ for definitions, usage, and quotation evidence.

method has developed meanings and uses in subjects including

How common is the noun method ?

How is the noun method pronounced, british english, u.s. english, where does the noun method come from.

Earliest known use

Middle English

The earliest known use of the noun method is in the Middle English period (1150—1500).

OED's earliest evidence for method is from before 1425, in Guy de Chauliac's Grande Chirurgie .

method is a borrowing from Latin.

Etymons: Latin methodus .

Nearby entries

- methionate, n. 1853–

- methionic, adj. 1842–

- methionine, n. 1928–

- methionine-enkephalin, n. 1975–

- methionyl, n.¹ 1924–

- methionyl, n.² 1939–

- methisazone, n. 1964–

- methium, n. ?1608–

- metho, n.¹ 1933–

- Metho, adj. & n.² 1940–

- method, n. ?a1425–

- method, v. 1607–40

- method-act, v. 1970–

- method-acted, adj. 1960–

- method acting, n. 1956–

- method actor, n. 1955–

- méthode champenoise, n. 1928–

- Methodenstreit, n. 1893–

- methodian, n. 1612

- methodic, adj. & n. ?1541–

- methodical, adj. 1570–

Thank you for visiting Oxford English Dictionary

To continue reading, please sign in below or purchase a subscription. After purchasing, please sign in below to access the content.

Meaning & use

Pronunciation, compounds & derived words, entry history for method, n..

method, n. was revised in December 2001.

method, n. was last modified in March 2024.

oed.com is a living text, updated every three months. Modifications may include:

- further revisions to definitions, pronunciation, etymology, headwords, variant spellings, quotations, and dates;

- new senses, phrases, and quotations.

Revisions and additions of this kind were last incorporated into method, n. in March 2024.

Earlier versions of this entry were published in:

OED First Edition (1906)

- Find out more

OED Second Edition (1989)

- View method, n. in OED Second Edition

Please submit your feedback for method, n.

Please include your email address if you are happy to be contacted about your feedback. OUP will not use this email address for any other purpose.

Citation details

Factsheet for method, n., browse entry.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Definition of methodology – Learner’s Dictionary

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

(Definition of methodology from the Cambridge Learner's Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

Translations of methodology

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

call centre

a large office in which a company's employees provide information to its customers, or sell or advertise its goods or services, by phone

Varied and diverse (Talking about differences, Part 1)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- Learner’s Dictionary Noun

- Translations

- All translations

To add methodology to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add methodology to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

22 Etymology

Philip Durkin is Deputy Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. He has led the OED’s team of specialist etymology editors since the late 1990s. His research interests include etymology, the history of the English language and of the English lexicon, language contact, medieval multilingualism, and approaches to historical lexicography. His publications include The Oxford Guide to Etymology (OUP 2009) and Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English (OUP 2014).

- Published: 03 March 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Etymology is an essential tool in tracing the origin and development of individual words. It is also indispensable for identifying, from a diachronic perspective, what the individual words of a language are, e.g. whether file ‘type of metal tool’ and file ‘set of documents’ share a common history or show different origins. However, words do not develop in isolation from one another. In extreme cases, complete lexical merger or lexical split can occur; such events can challenge the identification of words as entities with a single, discrete history. Etymological method depends on an interaction between arguments based on word form and word meaning. Regular sound changes are a cornerstone of etymology. Analysis of regular sound correspondences between languages, resulting from the operation of sound changes earlier than the surviving written records, is at the heart of the historical comparative method, by which proto-languages such as Indo-European have been identified.

22.1 Introduction: etymology and words

A topic that is crucial to any study of words is how we decide whether we are dealing with two different words or with a single word. Essentially, this is a matter of distinguishing between homonymy and polysemy. For instance, do file ‘type of metal tool’ and file ‘set of documents’ show two meanings of a single word (i.e. polysemy) or two different words which happen to be identical in pronunciation and spelling (i.e. homonymy)? This question will be approached differently depending on whether we adopt a synchronic or a diachronic perspective. From a synchronic perspective, what matters is whether we perceive a semantic link between the two words. Psycholinguistic experiments may even be conducted in order to measure the degree of association felt by speakers. Such approaches are outside the scope of this chapter. 1 From a diachronic perspective, what we most want to know is whether these two words of identical form share a common history, and if not, whether any influence of one word upon the other can be traced. These questions are answered by the application of etymology. In this particular example, the answer is quite categorical: the two words are of entirely separate origin (one is a word of native Germanic origin, the other a loanword from French; see further section 22.2 ), and there is no reason to suspect that either has exercised any influence on the other.

This chapter will look to give an overview of the core methods of etymology, i.e. how it is that we establish the separate histories of file ‘type of metal tool’ and file ‘set of documents’. It will also look closely at those areas where etymology can ask difficult questions about words as units in the diachronic study of the lexicon. Some words show a fairly simple linear progression from one stage in the history of a language to another, and there is no difficulty in saying that a word at one stage in the history of a language is the direct ancestor of a word in a later historical stage of the same language. In other cases things are much less simple. A single word in contemporary use may have resulted from multiple inputs from different sources, or a single word in an earlier stage in language history may have shown a process of historical split, giving rise ultimately to two quite distinct words in a later stage of the same language. Such phenomena, and the causes by which they arise, present many challenges for the assumption that we can always speak with confidence about ‘the history of a word’, and hence they will merit particular attention in this chapter.

22.2 A practical introduction to the core methods of etymology, through two short examples

Section 22.1 introduced the examples of modern English file ‘type of metal tool’ and file ‘set of documents’, and stated that from a diachronic perspective they are definitely two quite separate words: the first is part of the inherited Germanic vocabulary of English, while the second reflects a borrowing from French in the 16th century. It can further be stated that there is definitely no relationship between the Germanic word and the French one, and there are no grounds for supposing that the two English words have had any influence on one another during their history in English. All of this is established by applying the core methods of etymology, which this section will introduce by looking briefly at the histories of these two words. 2

Modern English file ‘type of metal tool’ has a well-documented and very simple history in English. The word existed already as fīl in the same meaning (though features of the referent may have changed, due to technological changes) in the earliest documented stage of the English language, Old English, and is also well attested in the Middle English period ( c .1150 –c .1500) and throughout the Modern English period (1500–). The word would have been pronounced /fiːl/ in Old English and Middle English; the modern diphthongal pronunciation /fʌɪl/ (with minor variation in different varieties of English) results from a regular sound change that affected /iː/ late in the Middle English period or very early in the Modern English period. This sound change is one of a series of changes in the pronunciation of vowels and diphthongs in English in this period, known collectively as the Great Vowel Shift (see further section 22.3 ).

The history of Modern English file ‘set of documents’ is a little more complicated, because semantic change as well as change in word form is involved. The word is first recorded in English in the early 16th century. It shows a borrowing of Middle French fil . The modern pronunciation shows that it must have been borrowed early enough to participate in the same development from /fiːl/ to /fʌɪl/ that is shown by the homonym file ‘type of metal tool’. The core meaning of the French word is ‘thread’ or sometimes ‘wire’. The earliest use of the word in English that is recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary refers to a wire, but specifically one on which papers and documents are strung for preservation and reference; the earliest example, from 1525, reads ‘Thapothecaries shall kepe the billis that they serue, vpon a fyle’, i.e. the apothecaries are to keep on a length of wire written records of the prescriptions that they have administered. From this beginning in English, the meaning of file developed by a process of metonymy from the wire on which a collection of records was kept (in later use, especially legal ones), to the set of records itself. This also explains why documents are described as being kept on file , or in earlier use upon (a) file .

22.3 Teasing out core etymological methods from these examples

The examples of file ‘type of metal tool’ and file ‘set of documents’ show the two main concerns of etymology: detecting and explaining change in word form, and detecting and explaining change in meaning. The histories of both words that I have set out here are well documented, but it is important to note that the historical narrative only emerges from interplay between the historical documents and etymology.

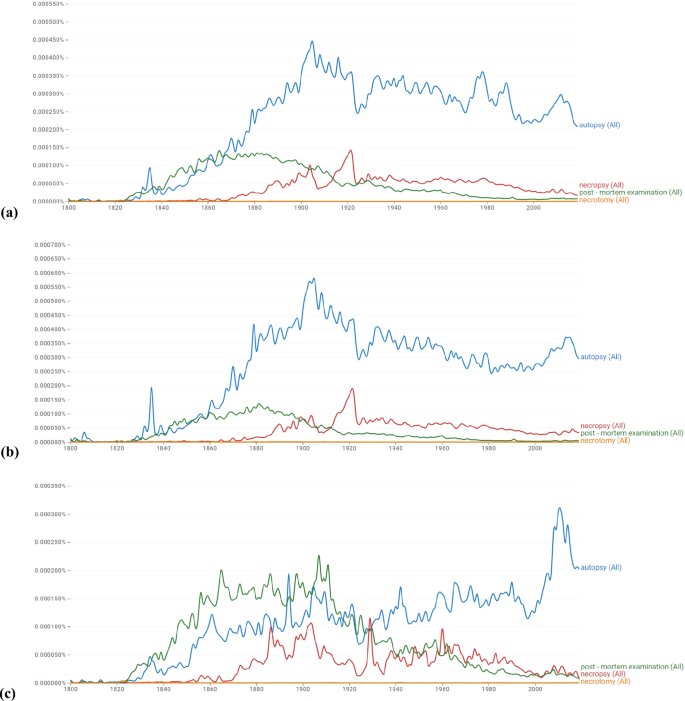

The word fīl exists in Old English and Middle English with the same meaning that file has in Modern English. A large mass of comparative and historical data tells us that Old English and Middle English fīl was pronounced /fiːl/. Observation of hundreds if not thousands of similar word histories tells us that as a result of one of the collection of changes we know as the Great Vowel Shift, a word that has /iː/ in Middle English will have /ʌɪ/ in contemporary (British) English pronunciation. The Great Vowel Shift consisted of a number of interrelated changes in the vowel system of English which extended from roughly the 15th century to the 18th, and which can be represented schematically as in Fig. 22.1 . (In fact, the modern quality of the diphthong in file probably results from later changes, but the initial diphthongization of /iː/ is a result of the Great Vowel Shift.) 3

The Great Vowel Shift (simplified).

Regular sound change of this type, affecting all sounds in a similar phonetic environment within a particular time period, is the most powerful explanatory tool available to an etymologist. Because of what we know about the history of English, based on etymological investigation of all of its lexis, we know that a word pronounced /fiːl/ in Old English and Middle English should be pronounced /fʌɪl/ in modern English. If it were not, we would have a problem with our historical account. Since it is, we do not. (See more on this issue below.)

As already explained, the same regular sound change that accounts for file ‘type of metal tool’ also accounts for the pronunciation history of file ‘set of documents’. This word additionally shows a rather dramatic semantic change, from ‘wire’ to ‘set of documents’. Because of our rich historical documentation for English, we can observe what has happened in detail. The explanation remains a hypothesis, but one about which there can be no reasonable doubt, because we can see all of the stages in the semantic history illustrated in contemporary documents, and because the semantic changes involved are well-known types: 4

Semantic Narrowing, From a Wire to Specifically a Wire on Which Paper Documents are Strung;

and then metonymy, from the wire on which a collection of records is kept, to the collection of records kept on the wire, and then semantic change mirroring technological change, as the records come to be stored by means other than hanging on a wire, and the word file comes to refer to any collection of paper documents;

and then further semantic change mirroring technological change, as the meaning becomes extended to documents (or now more typically a single document) in electronic form.

Precisely the same explanatory methods are used in attempts to construct etymological hypotheses where we have less data, and also for hypotheses that attempt to bridge large gaps in the historical record, or to project word histories back beyond the limits of the historical record. Regular sound change is by far the strongest explanatory tool in the armoury of an etymologist, because it tells us that a particular change should have occurred in a particular language (or dialect) at a particular time. The question of just how much regularity is shown by regular sound changes is a central one in historical linguistics, and one that has profound implications for etymology. Normally, most etymologists work with the assumption that the less data is available about a particular word history, the more important it is to ensure that general rules and tendencies apply. It is very poor methodology to hypothesize that a single word history may have shown a number of undocumented exceptions to otherwise regular sound changes in order to get from stage A to stage B.

Change in meaning is rather more of a problem for etymological reconstruction. General tendencies, such as metaphor, metonymy, narrowing, broadening, pejoration, or amelioration can be traced in countless word histories. The problem is that these changes rarely affect groups of words together. Certainly, we do not have any regular, period-specific changes such as ‘general late Middle English or Early Modern English semantic narrowing’, analogous to ‘late Middle English or Early Modern English diphthongization of /iː/’ which we can assume will have affected all words in a particular class in a particular period. For this reason, hypothesizing semantic histories is generally much more difficult than hypothesizing the form histories of words. In the case of file , we can get easily from the meaning ‘thread or wire’ to ‘set of documents’ because known tendencies in semantic change explain what we can see reflected in the historical record. Without the intervening historical record, if we knew only that fil means ‘thread or wire’ in Middle French and that file means ‘set of documents’ in modern English, it would be a brave and daring step to hypothesize a borrowing followed by this set of changes in order to explain this word history.

22.4 Comparison and reconstruction

The examples discussed so far have all been restricted to the history of English, except that in the case of file ‘set of documents’ it is assumed that Middle French fil ‘thread or wire’ was borrowed into late Middle English or Early Modern English. In this case, we are dealing with borrowing between two well-attested languages. We can see that fil ‘thread’ extends back into Old French (and clearly shows the continuation of a word in the parent language, Latin), and we can see that there is no earlier history of file ‘thread or wire’ in English; we also know that French and English were in close contact in this period, and that many words were borrowed. The situation becomes rather different if we push the history of both file ‘type of metal tool’ and file ‘set of documents’ back a little further. 5

As well as establishing word histories within languages, etymology can be employed to establish connections between words in different languages. These may be connections involving borrowing, as just illustrated, or they may be connections involving cognacy. This concept needs some explanation. One of the major findings of historical linguistics is that many present-day or historically documented languages can be identified as common descendants from earlier languages. Thus, French, Italian, Spanish, and the other Romance languages can all be traced as descendants from a common ancestor, Latin. Since Latin is amply attested in historical documents, the stages in the development can be traced in detail. The history of the Roman empire also gives us a crucial historical context in which to understand the circumstances of the wide geographical spread of Latin, and gives us some important hints about other languages that Latin was in contact with in different parts of the Empire. To focus on the level of an individual word, French fil can be seen to show the reflex, or direct linear development, of Latin fīlum ‘thread’. The same is true of Italian filo and Spanish hilo , and thus these are said to be cognates of French fil , showing a common descent from Latin fīlum . By contrast, French choisir ‘to choose’ does not show the reflex of a Latin word, but rather reflects a direct borrowing into French (or perhaps into the ancestor form of Vulgar Latin spoken in Gaul) from a Germanic language, probably in the context of the Frankish invasions of Gaul; the word is ultimately related to English choose .

By the application of what is termed the historical comparative method, many other such relationships of common descent have been identified. For instance, English can be identified as showing common descent with Frisian, Dutch, Low German, and High German; collectively they form the West Germanic branch of the Germanic language family. The relationships between the major members of the Germanic family can be reconstructed as in Fig. 22.2 . Proto-Germanic sits at the head of the Germanic languages, just as Latin sits at the head of the Romance languages. It is not directly attested, unlike Latin, but a great deal of its vocabulary, and of its phonology, morphology, and (to a lesser extent) its syntax can be reconstructed by comparison of its attested descendants. A great deal more information, and confirmation of much of what can be hypothesized from comparison within Germanic, comes from comparing the evidence of Germanic with the evidence for the much wider language family, Indo-European, to which it in turn belongs. Scholars working on Indo-European are very lucky, in that many separate branches have been identified, and some of them include languages that have very early surviving documentation (especially Hittite and Luvian), while others (especially Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin) have recorded histories that both go back a long way and extend over a very long period, with copious historical records. However, there are still limitations to how much of the vocabulary of proto-Indo-European can be reconstructed, and with what degree of confidence. 6 (Attempts to link Indo-European with other language families, in order to establish a shared linguistic descent from a common ancestor, are highly controversial, and not regarded as successful by most linguists working today.)

The major Germanic languages.

It is by application of this sort of methodology that we can be certain that some pairs of words, such as English care and Latin cūra ‘care’, or Latin deus and Greek theós ‘god’, are not related, in spite of their identical meaning and superficial similarity in form. Conversely, some pairs of words which show little formal or semantic similarity, such as English head and French chef ‘leader, boss’, can be shown to share a common origin.

In a small but very important set of cases, whole words can be clearly identified as direct reflexes of a single word in proto-Indo-European, rather than as developments from a shared root. For instance, father has a wide set of cognates in Germanic, including Old Frisian feder, fader , Old Saxon fadar , Old High German fater , Old Icelandic faðir , Gothic fadar (although, interestingly, this is a very rare word in Gothic, in which the more usual word for ‘father’ is atta ). Unlike in the case of file , we can also identify cognate words meaning ‘father’ in a wide range of languages from other branches of Indo-European, for instance Latin pater , ancient Greek πατήρ ( patḗr ), Sanskrit pitár -, Early Irish athir , Old Persian pitā , Tocharian A pācar . (Tocharian A and the related Tocharian B are the most easterly Indo-European languages, preserved in documents discovered in western China.) On the basis of these attested word forms, an Indo-European word meaning ‘father’ of approximately the form * ph 2 tér - is commonly reconstructed (the h 2 in the reconstruction represents a laryngeal sound assumed to have existed in Indo-European, which in this position can be understood as giving rise to the sound /ə/, hence probably /pəˈter/). The various attested forms can all be explained as arising from this same starting point, allowing for what is assumed about sound change in the pre-history of each language, and for assumptions about the morphology of Indo-European. Thus, the initial consonant /f/ in the English word again reflects the Grimm’s Law change * p > * f in the common ancestor of the Germanic languages. (The history of the medial consonant is rather more complex, involving a further change known as Verner’s Law, the discovery of which was itself an important stage in the development of the notion of regular sound change, since it explained a set of apparent exceptions to Grimm’s Law.)

Similarly, for ‘mother’, English mother has cognates in West Germanic and North Germanic (not though in Gothic, which has aiþei ), including: Old Frisian mōder , Old Saxon mōdar , Old High German muoter , Old Icelandic móðir . Cognates in other branches of Indo-European include: classical Latin māter , ancient Greek μήτηρ , Sanskrit mātar -, Early Irish māthir , Avestan mātar -, Tocharian A mācar . On the basis of these attested word forms, an Indo-European word meaning ‘mother’ of approximately the form * máh 2 ter - or perhaps * méh 2 ter - is commonly reconstructed.

It is almost certainly not accidental that the reconstructed words meaning ‘father’ and ‘mother’ have the sequence of sounds - ter - in common. This is found also in the reconstructed Indo-European forms assumed to lie ultimately behind English brother and daughter (but not sister , in which the - t- is of later origin, perhaps by analogy with the other words). Most scholars are therefore happy to recognize the existence of an element - ter - involved in forming words denoting kinship relationships, although opinions differ on the origin of this element and its possible connections with other suffixes in Indo-European. This leaves open the question of what the etymologies of the first elements of mother and father are. One suggestion is that both words may originate as forms suffixed in - ter - on the syllables /ma/ or /pa/ that are typical of infant vocalization, and which are probably reflected by English mama and papa , as well as forms in a wide variety of languages worldwide. However, there are other viable suggestions to explain the origin of both words.

This discussion has pushed several words back far beyond the limits of the historical record. This is is possible because we have a rich and early historical record for so many Indo-European languages. The historical record for many languages is much less rich, and this can impose severe limits on etymological research (although there have been significant achievements in areas such as the study of proto-Bantu). In addition, there are many languages that cannot be linked with large language families like Indo-European; some languages are (to the best of present knowledge) complete isolates (e.g., in the view of most scholars, Basque or Korean), while many others can only be linked securely with one or two other languages (e.g. Japanese and the related languages of the Ryukyu Islands). Of course, this does not mean that the whole of the lexis of such languages is necessarily unrelated to words found in other languages; the lexis of Japanese, for instance, contains large numbers of loanwords, including a very large contribution from Chinese during the medieval period, and a large recent contribution from English, such as terebi ‘television’ or depāto ‘department store’. Both of these words show accommodation to the phonological system of Japanese, as well as clipping (i.e. shortening of the word form), which is common in such loanwords. Such words or clipped elements of such words may also form new words in Japanese; for instance the second element of the word karaoke is a clipping of ōkesutara , borrowed from English orchestra (the first element is Japanese kara ‘empty’).

22.5 Words of unknown or uncertain etymology

As already seen, English has a richly documented and well-studied history and belongs to an extended language family many members of which are unusually well documented over a very long history. However, even in English there are many words that defy satisfactory etymological explanation. Some words go back to Old English, but no secure connections can be established with words in other Germanic languages, nor can a donor be identified for a loanword etymology. Some examples (all investigated recently for the new edition of the Oxford English Dictionary ) include adze, neap (tide), to quake (which could just be an expressive formation), or (all first attested in late Old English) plot, privet , or dog, hog, pig (these last three probably bear some relationship to one another, but exactly what is less clear). Some words of unknown etymology first recorded in Middle English include badge, big, boy, girl, nape, nook, to pore, to pout, prawn . Some more recent examples include to prod (first attested 1535), quirk (1565), prat (1567), quandary (1576), to puzzle ( c. 1595), pimp (1600), pun (1644). 7 For some of these words numerous etymological explanations have been suggested, but none has yet met with general acceptance.

In each of these cases there is relatively little doubt that we are dealing with a single coherent word history, but we are simply unable to explain its ulterior history. A slightly different kind of case is exemplified by queer . This is recorded from 1513 in the meaning defined by OED as ‘strange, odd, peculiar, eccentric’, and there is little doubt that most current senses developed from this beginning, including the modern use in the meaning ‘homosexual’. Its origin is uncertain; borrowing from German quer ‘transverse, oblique, crosswise, at right angles’ is a possibility, but the semantic correspondence is not exact, and figurative uses of the German word, such as ‘(of a person) peculiar’, are first attested much later than the English word. The interesting further complication in the case of queer is that in contemporary English queer also occurs in criminals’ slang in the meaning ‘of coins or banknotes: counterfeit, forged’. This may seem an unsurprising or at least plausible semantic development from ‘strange, odd’, but the difficulty is that this use (first recorded in 1740) seems to have developed from a meaning ‘bad; contemptible, worthless; untrustworthy; disreputable’, that is first recorded in 1567, and in early use this always shows spellings of the type quire . It therefore seems that in the 16th century there may have been two distinct words, queer ‘strange, odd, peculiar, eccentric’ and (in criminals’ slang) quire ‘bad; contemptible, worthless; untrustworthy; disreputable’. The one may have originated as a variant of the other, but there appears to be no formal overlap in the first century or so of co-existence of the two words. In the late 17th century, quire ‘bad; contemptible, worthless; untrustworthy; disreputable’ begins to appear in the spelling queer , suggesting a lowered vowel that is confirmed by the modern pronunciation. This change in form may well be the result of formal association with queer ‘strange, odd, peculiar, eccentric’, on the grounds of similarity of form and semantic proximity (what is odd often being deemed bad, etc.). A very difficult question is whether modern English has one word or two: quire , later queer ‘bad; contemptible, worthless; untrustworthy; disreputable’ seems the direct antecedent of queer ‘of coins or banknotes: counterfeit, forged’, but, if association with queer ‘strange, odd, peculiar, eccentric’ is what has caused an irregular change in word form from quire to queer , can we be certain that the two words have not become completely conflated for modern English speakers? An idiom such as as queer as a nine bob note may be construed by some speakers as simply showing the meaning ‘peculiar’ rather than specifically ‘counterfeit’. Certainly, the case is much more difficult than that of file ‘type of metal tool’ and file ‘set of documents’, where the intuition that there are two unrelated meanings, hence homonymy, coincides perfectly with the historical perspective. 8

The remainder of this chapter will look at some other types of scenario in which careful investigation of word histories by etymological methods presents tensions for the conception of the lexicon as consisting of a set of entirely discrete words with separate histories. By careful application of etymology, it is often possible to detect the grey areas, where lexical split or merger is in progress, either diachronically between different stages in the historical development of a language, or synchronically between different varieties of language.

22.6 Lexical merger and lexical split, and other types of ‘messiness’ in the histories of words

Proving that lexical merger has occurred can present difficulties for etymological-historical methodology. For instance, Old English has two distinct verbs in the meanings (intransitive) ‘to melt, become liquid’ and (transitive) ‘to cause to melt, to make liquid’. The first is a strong verb, meltan , with principal parts: present stem melt -, past tense (1st and 3rd person singular) mealt , past tense (plural) multon , and past participle gemolten . The second is a weak verb, of which the infinitive is either meltan or mieltan in different dialects of Old English, but which has past tense and past participle formed by a dental suffix. The forms of this verb that are actually recorded in Old English typically show syncopation of the dental suffix, e.g. past tense (1st and 3rd person singular) mielte and past participle mielt , but forms without syncopation of the dental suffix are also found, e.g. past participle gemælted . The two words are ultimately developed from the same Germanic base, and are ultimately cognate with words in other branches of Indo-European, the most direct correspondence being with ancient Greek μέλδειν ( méldein ) ‘to melt’. In modern English both sets of meanings are realized by a regular, weak verb, melt , with past tense and past participle melted . (A descendant of the original strong past participle survives, however, in specialized meaning as the adjective molten designating liquefied metal or glass.) Modern English melt is clearly the descendant of either Old English meltan (strong) or meltan, mieltan (weak), but describing quite what has happened is a little more difficult. Many verbs that were strong in Old English have switched to showing weak inflections in later English; thus modern English melt could in formal terms show the direct descendant of meltan (strong), with change in declensional class. On the other hand, many verbs that typically showed syncope of the dental suffix after a stem ending in a dental consonant have become regularized to show final -ed in later English; hence modern English melt could equally show the direct descendant of meltan, mieltan (weak). We could hypothesize that the strong and weak verbs have merged in the later history of English, giving one merged modern English verb melt in both transitive and intransitive uses. However, proving that this has happened purely by etymological methodology is difficult: from the data I have presented so far, we may infer from semantic similarity that melt in the meanings (intransitive) ‘to melt’ and (transitive) ‘to cause to melt’ shows a single polysemous lexeme, but etymological methodology alone does not rule out the alternative scenario where there is a continuous history of two verbs, melt 1 (intransitive) ‘to melt’ and melt 2 (transitive) ‘to cause to melt’ which have simply become homonyms in modern English. Since English has a particularly richly documented history, we can look at what sort of verbal morphology is found in Middle English. Here, as well as uses of weak forms such as melted in meanings of the old strong verb meltan (intransitive) ‘to melt’, we also find historically strong forms in transitive meanings, e.g. from Caxton ‘Saturne … malte and fyned gold and metalles’. In fact, the historical evidence when taken all together suggests a general confusion of forms in Middle English and Early Modern English: thus, in a 16th-century text we find ‘The Jewes when they molted a golden calfe … did neuer thinke that to be God’, with a past tense form molted that shows the weak past tense ending - ed but the stem vowel of the old strong past participle, used in a transitive meaning where the weak verb would have been expected historically. Thus the detailed historical data suggests strongly that merger has taken place; but without this level of detail the hypothesis of merger would be harder to support by historical methods alone. 9

Close study of word histories from historically well-attested languages suggests that processes of merger are in fact not uncommon. Reduction in the overall level of morphological variety, as shown for instance by the English verb system diachronically, is one common cause, as exemplified by melt . Another is where borrowing is found from more than one donor language. For instance, in the Middle English period English was in close contact with both French and Latin. Specifically, in the late Middle English period, English came to be used increasingly as a written language in contexts where either French or Latin or both had previously been used over a long period of time. In this context, many loanwords occur in English that could on formal grounds be from either French or Latin, and which show a complex set of borrowed meanings, which again could be explained by borrowing from either language. Examples include add, animal, information, problem, public . In some cases, particular form variants point strongly to input from one language rather than the other, or a particular meaning is found in French but not in Latin, or vice versa. Sometimes a particular meaning is attested earliest in a text that is translated directly from the one language, but it may be found a few years later in a text translated from the other. In most instances, the likeliest scenario seems to be that there has been input from both languages, reflecting multiple instances either of direct word borrowing or of semantic influence on an earlier loan; over time, multiple inputs have coalesced, to give semantically complex, polysemous words in modern English. 10

Demonstrating that lexical splits have occurred is generally a simpler task for etymological methodology, although pinpointing the precise point at which a split has occurred can be more difficult, especially since fine-grained historical data suggests that splits tend to diffuse gradually through a speaker group. For instance, modern English has two distinct words, ordinance and ordnance . The first is typically found in the meaning ‘an authoritative order’, and the second in specialized military meanings such as ‘artillery’ and ‘branch of government service dealing especially with military stores and materials’. Both words show the same starting point, Middle English ordenance, ordinance, ordnance , a borrowing from French, showing a wide range of meanings such as ‘decision made by a superior’, ‘ruling’, ‘arrangement in a certain order’, ‘provisions’, ‘legislative decree’, ‘machinery, engine’, ‘disposition of troops in battle’. In Middle English the forms with and without a medial vowel could be used in any of these meanings: the formal variation does not pattern significantly with the semantic variation. In course of time, the form without a medial vowel, ordnance , became usual in military senses, while the form ordinance became usual in general senses. Possibly what we have here is a situation where a pool of variants existed, and speakers in different social groups have selected different forms from within that pool of variants, ordnance having been the form that became usual within the military, but ordinance in most other groups using this word. Very gradually, as some meanings have fallen out of use and others have come to be used more or less exclusively with one word form or the other, a complete split has occurred, with ordinance and ordnance becoming established as distinct lexemes with different meanings. The time-frame over which this occurred appears to have been very long: the OED ’s evidence suggests that it is not complete before the 18th century, and even in contemporary English ordinance may occasionally be found in the military senses, although in formal use it is likely to be regarded as an error.

Similar splits may also be found that affect only the written form of a word, particularly in modern standard languages with well-established orthographic norms. For instance, modern English flour originated as a spelling variant of flower ; flour was perceived metaphorically as the ‘flower’ or finer portion of ground meal. The word flower is a Middle English borrowing from French, and it is found in the meaning ‘flour’ already in the 13th century; both meanings still appear under the single spelling flower in Johnson’s dictionary in 1755, although by this point some other written sources already distinguish clearly between the spellings flower and flour in the two meanings.

There are, however, instances of lexical split that are much less categorical. One such instance is shown by the modern English reflex(es) of Middle English poke ‘bag, small sack’. The word survives in this meaning in modern Standard English only in fossilized form in the idiom a pig in a poke (referring to something bought or accepted without prior inspection), but it remains in more general use in some regional varieties of English. Various other semantic developments ultimately from the same starting point survive in certain varieties of English. From the meaning ‘small bag or pouch worn on the person’ the narrowed meaning ‘a purse, a wallet, a pocketbook’ developed, although this is labelled by OED as being restricted to North American criminals’ slang; a further metonymic development from this, ‘a roll of banknotes; money; a supply or stash of money’, is labelled by OED as belonging to more general slang use. Metaphorical uses recorded as still current in different varieties of English included (in Scottish English) ‘a bag-shaped fishing net, a purse-net’, (in Scottish English and in the north of England) ‘an oedematous swelling on the neck of a sheep’, (in North America, chiefly in whaling) ‘a bag or bladder filled with air, used as a buoy or float’. Running alongside this splintering in meaning there are interesting patterns of formal variation: for instance, in Scottish English the form types pock and pouk occur as well as poke (reflecting phonological developments that are familiar from other words of similar shape), although these form variants do not appear to have become associated exclusively with particular meanings. In this instance, we can see that the etymological principle in use in a historical dictionary can effectively group all of this material together under a single dictionary headword poke , as showing a single point of origin, without any definitive split into different word forms employed in different meanings. However, what poke denotes will differ radically for different speakers of English depending on their membership of different speaker groups, and it is likely that if an individual speaker happens to be familiar with the meanings ‘money’ and ‘a bag or bladder filled with air’ he will be very unlikely to perceive any relationship between them, any more than between historically unrelated homonyms such as file ‘type of metal tool’ and file ‘set of documents’.

22.7 Conclusions

Etymology is an essential tool in tracing the historical origin and development of individual words, and in establishing word histories. Indeed, this could serve as a definition of etymology, broadly conceived. 11 Etymological method depends on an interaction between arguments based on word form and arguments based on word meaning. Regular sound changes are a cornerstone of etymological argument, especially when attempts are made to trace word histories far beyond the limits of the surviving written record. In a historical perspective, how we identify distinct word histories is heavily dependent on the application of etymology. As such, etymology can pose provocative questions about whether we can always identify complex words as coherent entities with a single, discrete history.

For discussion of these issues see Koskela (forthcoming) , and also Klepousniotou (2002) , Beretta et al. (2005) .

For fuller treatment of etymological methodology see Durkin (2009) . For some different perspectives see (with examples drawn chiefly from German) Seebold (1981) , (focussing purely on issues to do with the history and pre-history of English) Bammesberger (1984) , (focussing particularly on Romance languages and their coverage in etymological dictionaries) Malkiel (1993) , or (targeted at a more popular audience) Liberman (2005) .

On this and other sound changes discussed in this chapter see Durkin (2009) and further references given there. For a more detailed account of the Great Vowel Shift and an overview of the extensive literature on this topic see especially Lass (1999) .

For types of semantic change, see Geeraerts , this volume.

The etymologies presented in this chapter all draw on documentation from the standard etymological and historical dictionaries for each language involved. Listing all of the dictionaries concerned would be beyond the scope of this article. The etymological dictionary is one of the major outlets for etymological research; as well as advancing new ideas, etymological dictionaries typically summarize the main earlier hypotheses, taking note of data from the other major outlet for etymological research, articles in scholarly journals. On the typology and structure of etymological dictionaries see Buchi (forthcoming) and Malkiel (1975 , 1993 ).

For an excellent introduction to the Indo-European languages see Fortson (2009) . On the methodology for establishing the family see especially Clackson (2007) . For a very useful overview of some of the core reconstructed vocabulary of Indo-European see Mallory and Adams (2006) .

The frequency of words beginning with certain initial letters in these lists of examples reflects the fact that they have been drawn from the new edition of the OED currently in progress, in which the alphabetical sequence M to R is the largest continuous run of entries so far published.

For fuller discussion of this example see Durkin (2009 : 216–18).

For further discussion of this and of the examples of lexical split discussed later in this section, and for further examples, see Durkin (2009 : 79–88).

On words of this type see Durkin (2002) , Durkin (2008) , Durkin (forthcoming a).

On definitions of etymology see Alinei (1995) , Durkin (2009) .

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Method etymology

English word method comes from Ancient Greek (to 1453) μετά, Ancient Greek (to 1453) ὁδός, and later Middle French (ca. 1400-1600) methode (Method; manner of doing something.)

Etymology of method

Detailed word origin of method, words with the same origin as method, descendants of μετά, descendants of ὁδός.

U speak Greek

- Most popular:

- autonomy definition

- lyric etymology

- Ironic Definition

But you don't know it

Etymology and Origin of the word Method

The word “method” originates from the Greek word “μέθοδος” (methodos), which is derived from “μετά” (meta) meaning “with,” “after,” or “beyond,” and “ὁδός” (hodos), meaning “way,” “road,” or “path.”

In ancient Greek, “methodos” referred to a pursuit, a way of inquiry, or a way of thinking and acting. The term was used to describe a systematic and orderly approach to an objective, emphasizing the process or path taken.

When the term was adopted into English in the late 14th century, it retained these connotations of a systematic or orderly procedure or approach. In modern usage, “method” generally refers to a particular procedure for accomplishing or approaching something, especially a systematic or established one.

Thus, the original Greek roots of “method” combine the ideas of “with” or “along a path” with “way” or “path,” emphasizing a systematic way of doing something or a procedure followed to achieve a specific end.

- Pingback: Empirical Evidence Explained: The Backbone of Scientific Research - U speak Greek

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Related Articles

Catastrophe Definition: Unraveling the Meaning Behind Dramatic Disasters

Explore the etymology and multifaceted definition of ‘catastrophe’, from its Greek origins to its application in natural disasters and storytelling.

Etymology and Origin of word Abyss

Explore ‘abyss’: a term from Greek ‘ábyssos’ meaning ‘bottomless,’ used in everyday language, philosophy, and science to describe profound depths.

Diaspora Definition: Tracing the Dispersal from Greek Etymology to Global Context